#shoeshine shop

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Christmas Shopping Distractions!

Headed out of the mall but obviously, I paused to long and was caught looking at this hot man at the shoeshine stand. I headed for the door but before I made it, he caught up. So you want a feel, he grinned, I know a changing room that is never busy this time of day. Another 30 minutes!

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jade and Floyd Info Compilation part 38: Fashion

Jade says that mermaids do not usually wear any clothes at all (“so…use your imagination”), but Floyd has formed an interested in fashion since coming onto land: Floyd says that he he wasn’t a big fan of clothing at first (“Seemed like a huge waste of time”) but now he likes wearing different colors and coordinating with shoes and accessories.

Floyd says he keeps up-to-date on fashion through Magicam and fashion magazines but he isn’t interested in copying other people’s styles.

In his third birthday vignette Floyd says he has his eye on a vintage jacket that he hopes someone will be getting for him as a gift, and in Epel’s vignette he mentions shopping for clothes in a nearby city, so he seems fairly big on shopping.

He signs up for the Culinary Crucible in order to afford to buy an expensive pair of shoes.

He buys an entire outfit specifically for the Vargas Camp event and says he recognizes the designer brands worn by Leona and Ruggie.

(He does not appreciate Jack calling him out for not wearing his PE uniform like the other students do.)

Floyd does not like the bowtie that comes with his dorm uniform. Jade says, “I couldn’t even count how many times I’ve tied it for him.”

(Despite how Jade is always wearing his clothing properly buttoned and tied he says that he finds clothes uncomfortable and still hasn’t grown accustomed to them.)

Floyd’s wish in the Wish Upon a Star event is for new shoes and Azul seems to encourage his interest in footwear, gifting him with a shoeshine kit for his birthday.

Floyd is most interested in “Ténèbres” brand shoes, which is the same brand of shoe that Jade manages to procure for Vil in a vignette (there is a mistranslation where a line said by Jade gets rewritten to be said by Vil).

While Jade may not be as interested in fashion as Floyd he seems to have an appreciation for “freshly starched shirts and dried sheets right of the line,” gifting Ruggie with laundry detergent for his birthday.

82 notes

·

View notes

Note

porky did you finish that list of minecraft splash texts and if so may we see it?

Sure, keep in mind the Better Than Adventure mod uses a different colour formatting code than vanilla though. It's also a bit more difficult to edit splash text in vanilla from what I can gather. Anyway:

§5>it's wet Pynk! >ISHYGDDT GALO SENGEN! Pretty smooth flying, Fox! :kanabento: Sad! ingredience Everybody pose! :JUST: Oh, absolutely! Hallownest approved! Soda! Nope! §0The air crackles with freedom. Master Spark! An extant form of life! Yesh §dNyuuu! Also try The Witness! hampter.jpg The city and the city! Qud approved! Also try Mummy Sandbox! What U Need! Drink it and forget it all! which I invented! §fAll black everything The hero appears! Touch grass! Ut UNDERSTAND! Gapacho approved! Interior Semiotics! It's yours, my friend! The silo doors are open! Who are you quoting? Smoke coal evree day! §5>not having an avocado tree MODS = GODS Women! Wrong number! A super fighting robot from the year 2010! Even the mods have mods! Is shine! Cassis bleep! It's media -_- Also try Manifold Garden! Labyrinth Fight! Grow up, this is Minecraft! Welcome, Mr. Guest. His name is Gedächtnis! With these hands we will destroy! WAKE ME UP Fighting in the dojo! §eLalal Jack in! PUNK TACTICS! Close enough! I buy sausage! You ARE the support, son! A frozen cephalopod! Milk inside a bucket of milk inside a bucket of milk §0Hit +50! SB-129 mariositting.txt Clean! The democratic club! went shop Also try The Witch's House! Vanilla+! :3 TRUE! DOOR STUCK! Dubious castle safety gigue! Sexo! The numbers, Mason! Don't be so wide about it! MACHINE HEEEEEEEEAAAAAD! Victorius! The grink is here! k/l/l/i/n/g/s/t/a/l/k/i/n/g! GAS GAS GAS! Wimdy! A vision of happiness! Got any grapes? Message over! I MAED A GAM3 W1TH Z0MB1ES 1N IT!!!1 wort wort wort Many such cases! I'm Kilroy! Just walk out! Detach the rear vehicle! SET ME UP! Wrong turn, tin daddy! Woomy! Gensokyo approved! Soup's on, baby! Fly away now! Literally who? Greetings from Germany! Papa Carlo! Superliminal! BAN THIS SICK FILTH King! Ari! Also try SOMA! SOME FOLKS ARE BORN 8 meters! This is most disturbing! Wheey! [Current thing]! Jerry! Welcome back, /v/! >:3 How does he do it? The Paper! 47 diamonds in my diamond account! The hero appears!!! Fly over! SICK RECOVERY The big bow-wow! Guest no. 431! GOODLUCK! CAMPEÃO DO MUNDO! Built from pieces of SR71! §eDe§5su! EEEEASY! Hedgehog stew! Unusual! :yey: Uranium Fever! Chinken nunget! There's friendship in the redstone! Axeil Edition! Beach City approved! §aourple! The Golden Path lies §4everywhere! Don't look at the silver lights The Electro Gypsy! Menacing! Cope! The hero appears!! OH GOD MAH DRILLS! eeeeeh? Also try Outer Wilds! Edith Piaf said it better Where's Reznov? INGERLAAAAAND! Also try Gorogoa! Orgasmic! Pure pare-do! §6It's lightish red! Also try Rain World! Hard Fast §kFaggot §rMaps! Hole approved! HUZZAH! Lost and farting! Selamat pagi! Deploy all units! CHARGE!!! Minute like a pixie! Most certainly! freaks dni! The ride never ends! Lucoa! Not what it says. The bits! The bits! The bits! :african_pensive: §mMother is watching §eH§1e§4l§5v§de§3t§bi§ac§2a §2S§6t§aa§6n§6d§1a§3r§2d Morioh approved! Comforble! Cocky little freaks! Also try Fallow! :pensive: Brillo whales soon! Scratch Perverts! Re-do! MEMORIES BROKEN! 300k starting! Also try sunny-place! tak tak tak ziip! NOW THE WHEELS ARE SPINNING OUT OF CONTROL! Roast beef and cornbread! No sappy lines allowed! With these hands we will rebuild! Also try The Beginner's Guide! Chefs kiss? Get the cool shoeshine! Happens often! Blood crystal obtained! MAKE IT BUN DEM! :hinableh: Also try Northern Journey! Welcome to Quindecim :) ARE YOU WATCHING HEAVEN? Daten City Approved! AS I LIVE! hina hina Nashi! Hack your 3DS! 4 = 2 > 5 > 7 > 3 > 1 > 6 > 8 Butcher is king! und cola! Lost at sea 1803 Bam-ba-lam! §3Aria approved! Seems legit! Easy Breezy! The World Revolving! Air 'em out! I live here? Splendid! Sing your sins! Surprisingly malleable! Comedy gold! §6Anglerfish Dance! Message to de west! Also try Dujanah! dubs Also try Iconoclasts! §aPudgy-Porky!?

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moonlight Sonata

A spring evening. A large room in an old house. A woman of a certain age, dressed in black, is speaking to a young man. They have not turned on the lights. Through both windows the moonlight shines relentlessly. I forgot to mention that the Woman in Black has published two or three interesting volumes of poetry with a religious flavor. So, the Woman in Black is speaking to the Young Man: Let me come with you. What a moon there is tonight! The moon is kind—it won’t show that my hair has turned white. The moon will turn my hair to gold again. You wouldn’t understand. Let me come with you. When there’s a moon the shadows in the house grow larger, invisible hands draw the curtains, a ghostly finger writes forgotten words in the dust on the piano—I don’t want to hear them. Hush. Let me come with you a little farther down, as far as the brickyard wall, to the point where the road turns and the city appears concrete and airy, whitewashed with moonlight, so indifferent and insubstantial so positive, like metaphysics, that finally you can believe you exist and do not exist, that you never existed, that time with its destruction never existed. Let me come with you. We’ll sit for a little on the low wall, up on the hill, and as the spring breeze blows around us perhaps we’ll even imagine that we are flying, because, often, and now especially, I hear the sound of my own dress like the sound of two powerful wings opening and closing, and when you enclose yourself within the sound of that flight you feel the tight mesh of your throat, your ribs, your flesh, and thus constricted amid the muscles of the azure air, amid the strong nerves of the heavens, it makes no difference whether you go or return and it makes no difference that my hair has turned white (that is not my sorrow—my sorrow is that my heart too does not turn white). Let me come with you. I know that each one of us travels to love alone, alone to faith and to death. I know it. I’ve tried it. It doesn’t help. Let me come with you. This house is haunted, it preys on me— what I mean is, it has aged a great deal, the nails are working loose, the portraits drop as though plunging into the void, the plaster falls without a sound as the dead man’s hat falls from the peg in the dark hallway as the worn woolen glove falls from the knee of silence or as a moonbeam falls on the old, gutted armchair. Once it too was new—not the photograph that you are staring at so dubiously— I mean the armchair, very comfortable, you could sit in it for hours with your eyes closed and dream whatever came into your head —a sandy beach, smooth, wet, shining in the moonlight, shining more than my old patent leather shoes that I send each month to the shoeshine shop on the corner, or a fishing boat’s sail that sinks to the bottom rocked by its own breathing, a three-cornered sail like a handkerchief folded slantwise in half only as though it had nothing to shut up or hold fast no reason to flutter open in farewell. I have always had a passion for handkerchiefs, not to keep anything tied in them, no flower seeds or camomile gathered in the fields at sunset, nor to tie them with four knots like the caps the workers wear on the construction site across the street, nor to dab my eyes—I’ve kept my eyesight good; I’ve never worn glasses. A harmless idiosyncracy, handkerchiefs. Now I fold them in quarters, in eighths, in sixteenth to keep my fingers occupied. And now I remember that this is how I counted the music when I went to the Odeion with a blue pinafore and a white collar, with two blond braids —8, 16, 32, 64— hand in hand with a small friend of mine, peachy, all light and pink flowers, (forgive me such digressions—a bad habit)—32, 64—and my family rested great hopes on my musical talent. But I was telling you about the armchair— gutted—the rusted springs are showing, the stuffing— I thought of sending it next door to the furniture shop, but where’s the time and the money and the inclination—what to fix first?— I thought of throwing a sheet over it—I was afraid of a white sheet in so much moonlight. People sat here who dreamed great dreams, as you do and I too, and now they rest under earth untroubled by rain or the moon. Let me come with you. We’ll pause for a little at the top of St. Nicholas’ marble steps, and afterward you’ll descend and I will turn back, having on my left side the warmth from a casual touch of your jacket and some squares of light, too, from small neighborhood windows and this pure white mist from the moon, like a great procession of silver swans— and I do not fear this manifestation, for at another time on many spring evenings I talked with God who appeared to me clothed in the haze and glory of such a moonlight— and many young men, more handsome even than you, I sacrificed to him— I dissolved, so white, so unapproachable, amid my white flame, in the whiteness of moonlight, burnt up by men’s voracious eyes and the tentative rapture of youths, besieged by splendid bronzed bodies, strong limbs exercising at the pool, with oars, on the track, at soccer (I pretended not to see them), foreheads, lips and throats, knees, fingers and eyes, chests and arms and thighs (and truly I did not see them) —you know, sometimes, when you’re entranced, you forget what entranced you, the entrancement alone is enough— my God, what star-bright eyes, and I was lifted up to an apotheosis of disavowed stars because, besieged thus from without and from within, no other road was left me save only the way up or the way down.—No, it is not enough. Let me come with you. I know it’s very late. Let me, because for so many years—days, nights, and crimson noons—I’ve stayed alone, unyielding, alone and immaculate, even in my marriage bed immaculate and alone, writing glorious verses to lay on the knees of God, verses that, I assure you, will endure as if chiselled in flawless marble beyond my life and your life, well beyond. It is not enough. Let me come with you. This house can’t bear me anymore. I cannot endure to bear it on my back. You must always be careful, be careful, to hold up the wall with the large buffet to hold up the buffet with the antique carved table to hold up the table with the chairs to hold up the chairs with your hands to place your shoulder under the hanging beam. And the piano, like a closed black coffin. You do not dare to open it. You have to be so careful, so careful, lest they fall, lest you fall. I cannot bear it. Let me come with you. This house, despite all its dead, has no intention of dying. It insists on living with its dead on living off its dead on living off the certainty of its death and on still keeping house for its dead, the rotting beds and shelves. Let me come with you. Here, however quietly I walk through the mist of evening, whether in slippers or barefoot, there will be some sound: a pane of glass cracks or a mirror, some steps are heard—not my own. Outside, in the street, perhaps these steps are not heard— repentance, they say, wears wooden shoes— and if you look into this or that other mirror, behind the dust and the cracks, you discern—darker and more fragmented—your face, your face, which all your life you sought only to keep clean and whole. The lip of the glass gleams in the moonlight like a round razor—how can I lift it to my lips? however much I thirst—how can I lift it—Do you see? I am already in a mood for similes—this at least is left me, reassuring me still that my wits are not failing. Let me come with you. At times, when evening descends, I have the feeling that outside the window the bear-keeper is going by with his old heavy she-bear, her fur full of burrs and thorns, stirring dust in the neighborhood street a desolate cloud of dust that censes the dusk, and the children have gone home for supper and aren’t allowed outdoors again, even though behind the walls they divine the old bear’s passing— and the tired bear passes in the wisdom of her solitude, not knowing wherefore and why— she’s grown heavy, can no longer dance on her hind legs, can’t wear her lace cap to amuse the children, the idlers, the importunate, and all she wants is to lie down on the ground letting them trample on her belly, playing thus her final game, showing her dreadful power for resignation, her indifference to the interest of others, to the rings in her lips, the compulsion of her teeth, her indifference to pain and to life with the sure complicity of death—even a slow death— her final indifference to death with the continuity and the knowledge of life which transcends her enslavement with knowledge and with action. But who can play this game to the end? And the bear gets up again and moves on obedient to her leash, her rings, her teeth, smiling with torn lips at the pennies the beautiful and unsuspecting children toss (beautiful precisely because unsuspecting) and saying thank you. Because bears that have grown old can say only one thing: thank you; thank you. Let me come with you. This house stifles me. The kitchen especially is like the depths of the sea. The hanging coffeepots gleam like round, huge eyes of improbable fish, the plates undulate slowly like medusas, seaweed and shells catch in my hair—later I can’t pull them loose— I can’t get back to the surface— the tray falls silently from my hands—I sink down and I see the bubbles from my breath rising, rising and I try to divert myself watching them and I wonder what someone would say who happened to be above and saw these bubbles, perhaps that someone was drowning or a diver exploring the depths? And in fact more than a few times I’ve discovered there, in the depths of drowning, coral and pearls and treasures of shipwrecked vessels, unexpected encounters, past, present, and yet to come, a confirmation almost of eternity, a certain respite, a certain smile of immortality, as they say, a happiness, an intoxication, inspiration even, coral and pearls and sapphires; only I don’t know how to give them—no, I do give them; only I don’t know if they can take them—but still, I give them. Let me come with you. One moment while I get my jacket. The way this weather’s so changeable, I must be careful. It’s damp in the evenings, and doesn’t the moon seem to you, honestly, as if it intensifies the cold? Let me button your shirt—how strong your chest is —how strong the moon—the armchair, I mean—and whenever I lift the cup from the table a hole of silence is left underneath. I place my palm over it at once so as not to see through it—I put the cup back in its place; and the moon’s a hole in the skull of the world—don’t look through it, it’s a magnetic force that draws you—don’t look, don’t any of you look, listen to what I’m telling you—you’ll fall in. This giddiness, beautiful, ethereal—you will fall in— the moon’s a marble well, shadows stir and mute wings, mysterious voices—don’t you hear them? Deep, deep the fall, deep, deep the ascent, the airy statue enmeshed in its open wings, deep, deep the inexorable benevolence of the silence— trembling lights on the opposite shore, so that you sway in your own wave, the breathing of the ocean. Beautiful, ethereal this giddiness—be careful, you’ll fall. Don’t look at me, for me my place is this wavering—this splendid vertigo. And so every evening I have a little headache, some dizzy spells. Often I slip out to the pharmacy across the street for a few aspirin, but at times I’m too tired and I stay here with my headache and listen to the hollow sound the pipes make in the walls, or drink some coffee, and, absentminded as usual, I forget and make two—who’ll drink the other? It’s really funny, I leave it on the windowsill to cool or sometimes I drink them both, looking out the window at the bright green globe of the pharmacy that’s like the green light of a silent train coming to take me away with my handkerchiefs, my run-down shoes, my black purse, my verses, but no suitcases—what would one do with them? Let me come with you. Oh, are you going? Goodnight. No, I won’t come. Goodnight. I’ll be going myself in a little. Thank you. Because, in the end, I must get out of this broken-down house. I must see a bit of the city—no, not the moon— the city with its calloused hands, the city of daily work, the city that swears by bread and by its fist, the city that bears all of us on its back with our pettiness, sins, and hatreds, our ambitions, our ignorance and our senility. I need to hear the great footsteps of the city, and no longer to hear your footsteps or God’s, or my own. Goodnight. The room grows dark. It looks as though a cloud may have covered the moon. All at once, as if someone had turned up the radio in the nearby bar, a very familiar musical phrase can be heard. Then I realize that “The Moonlight Sonata,” just the first movement, has been playing very softly through this entire scene. The Young Man will go down the hill now with an ironic and perhaps sympathetic smile on his finely chiselled lips and with a feeling of release. Just as he reaches St. Nicholas’, before he goes down the marble steps, he will laugh—a loud, uncontrollable laugh. His laughter will not sound at all unseemly beneath the moon. Perhaps the only unseemly thing will be that nothing is unseemly. Soon the Young Man will fall silent, become serious, and say: “The decline of an era.” So, thoroughly calm once more, he will unbutton his shirt again and go on his way. As for the Woman in Black, I don’t know whether she finally did get out of the house. The moon is shining again. And in the corners of the room the shadows intensify with an intolerable regret, almost fury, not so much for the life, as for the useless confession. Can you hear? The radio plays on: YANNIS RITSOS The Fourth Dimension. Princeton University Press, 1993. Translated from the Greek by Peter Green and Beverly Bardsley.

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

You swallow hard when you discover that the old coffee shop is now a chain pharmacy, that the place where you first kissed so-and-so is now a discount electronics retailer, that where you bought this very jacket is now rubble behind a blue plywood fence and a future office building. Damage has been done to your city. You say, ''It happened overnight.'' But of course it didn't. Your pizza parlor, his shoeshine stand, her hat store: when they were here, we neglected them. For all you know, the place closed down moments after the last time you walked out the door. (Ten months ago? Six years? Fifteen? You can't remember, can you?) And there have been five stores in that spot before the travel agency. Five different neighborhoods coming and going between then and now, other people's other cities. Or 15, 25, 100 neighborhoods. Thousands of people pass that storefront every day, each one haunting the streets of his or her own New York, not one of them seeing the same thing.

Colson Whitehead, The Colossus of New York

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

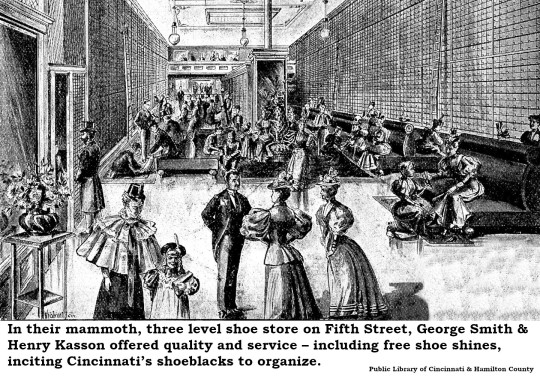

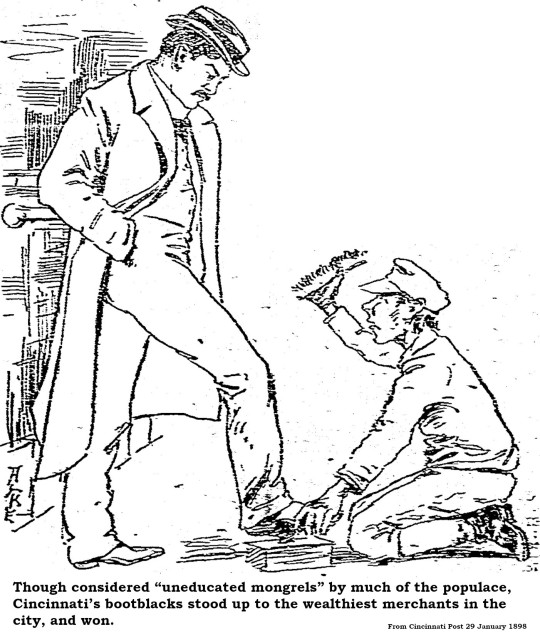

Cincinnati Bootblacks Organized To Fight Free Shine Services By Local Merchants

The opening of a new shoe store in 1895 caught the attention of Cincinnati’s bootblacks, and they weren’t happy at all.

The Smith, Kasson & Co. store on the north side of Fifth Street, just east of Race, promised high quality footwear at prices affordable to the masses. George Smith, Henry Kasson and their partners indulged their customers with luxurious extras. An orchestra performed amid veritable gardens of potted plants. The décor was all of brass setting off maroon leather. An X-ray device assured a precise fit. The store offered, whether you were a customer or not, to shine your shoes for free. There was the rub.

Outside on the streets, dozens of bootblacks braved the entire panoply of Cincinnati weather to shine shoes for a dime, rarely pulling in a dollar a day. Some of the city’s “shine artists” occupied a stand in a barber shop or shine salon, but they were few and charged more.

To aggravate the situation, companies that manufactured shoe polish didn’t distribute through general stores. Shoe polish was sold only at shoe stores, forcing bootblacks to buy their supplies from the very establishments taking away their livelihood by offering free shines.

Christmas season in 1897 found Cincinnati’s shoeshine “boys” (most were grown men) on starvation rations as more and more businesses – not only shoe stores, but department stores as well – offered free shines. By January 1898, the bootblacks reached the boiling point. The raggle-taggle group announced a meeting and invited Mayor Gustav Tafel to attend. According to the Cincinnati Post, Mayor Tafel was sympathetic to the cause:

“The mayor has not patronized stores at which free shines were given, and either does the work himself or pays for having his boots polished. He favors the antifree-shine movement on behalf of the bootblacks.”

The Post, sensing an issue on which to build its reputation as the city’s progressive newspaper, provided extensive coverage of the dispute. In an editorial [1 February 1898] the newspaper announced its support:

“Everybody is talking about the bootblacks! Manly determination is always admirable. The assertion of the bootblacks that “Free shines is got to go!” carries with it the assumption of good argument. Give the bootblacks a fair hearing.”

Post reporters gathered quotes of support from prominent men, such as city councilman John Wahburn:

“A man does not expect free shoes. Why should he expect free shines? Let us all pay for both.”

The Post also collected endorsements from some of the city’s less-respectable celebrities, including Dan Bauer, who owned the notorious Majestic Concert Hall that the Post would rail against a few years later:

“Give the bootblacks what is due them. They are entitled to the business.”

The Post also collected letters from bootblacks outlining their grievances. Some were printed with grammatical and spelling mistakes patronizingly preserved. One correspondent, William H. Schmidt, stated the case eloquently:

“Some people are inclined to think the bootblacks are a band of mongrels, uneducated and indifferent to circumstances. I want to say to these people that there are scores of us who are really worthy of better employment. We can’t get it, and accordingly make the best of our lot.”

On Tuesday morning, the first of February, the city’s bootblacks gathered at the College Hall on Walnut Street to discuss strategy. Temporary chair of the meeting was Harry Lemmon, who was not a bootblack at all, but an inspector at the Customs House. Lemmon introduced a motion to select a permanent chair when a disturbance halted the proceedings. According to the Post [1 February 1898]:

“There was some commotion in the hall. The doors burst open and in came 50 more bootblacks. One was playing a harp and others were cheering. It was five minutes before the election was resumed.”

The newcomers were a delegation of shoe-shiners who had rallied around their own celebrity, featherweight boxer Albert “Kid Ashe” Laurey. The Kid was no bootblack, but he was a popular athlete and was soon elected president of the meeting. Laurey, an African American, underlined the multiracial make-up of the bootblack constituency. Though the papers didn’t make much of the inclusive nature of the movement, it was probably the only integrated union in Cincinnati at the time, the other trades maintaining strictly segregated locals.

The lively group soon organized as the Cincinnati Bootblacks Protective Association, and drafted a petition demanding that Cincinnati merchants cease offering free shoeshines by the end of the week. In the back of the room, a man rose and announced that his employer, Mabley & Carew, would stop the practice immediately. Representatives of Rollman & Sons, Potter Shoes, the Foreman Shoe Company and Smith, Kasson & Co. were also present and agreed to end the service as well. In short order, the rest of the city’s merchants fell in line.

The association agreed to charge 10 cents for a shine and to levy dues of 10 cents a week to build up a fund for homeless and hospitalized members. The Cincinnati Post had one of the staff artists design an insignia for the group.

Although victorious in their initial battle, the war went on for years. By Thanksgiving, a few stores again began shining shoes as a complementary service. The Cincinnati Bootblacks Protective Association had gone largely inactive and had to be revived to counter this new threat. The association was revived again in 1901 after a couple years of inactivity, and yet again in 1905.

More disconcerting was a threat from within the bootblack community. A “trust” organized by unaffiliated bootblacks opened a shine parlor and only charged a nickel. The association sent a persuasive delegation to convince them that going out of business was a healthy decision.

#cincinnati bootblack protective association#cincinnati bootblacks#smith kasson comapny#cincinnati labor

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

You might also like this song - Sarah, Sarah.

youtube

"Sarah, Sarah, sitting in a shoeshine shop Sarah, Sarah, sitting in a shoeshine shop All day long, she sits and shines All day long, she shines and sits Sarah, Sarah, sitting in a shoeshine shop"

...as you can imagine, it usually goes downhill from there. [Full lyrics here]

70 People Try 70 Tongue-Twisters From 70 Countries

53K notes

·

View notes

Text

Harold “Hal” Jackson (November 3, 1915 - May 23, 2012) legendary broadcaster, radio station owner, and philanthropist was born in Charleston, South Carolina to Eugene and Laura Jackson. Eugene owned a successful tailor shop in Charleston. When he was nine, both of his parents passed away within several months of one another. He lived with relatives in New York and DC until he reached the age of 13 when he moved into a DC boarding house.

He attended Dunbar High School and supported himself by working as a shoeshine boy. He excelled in sports and during his free time worked as an usher for Washington Senators baseball games. He attended Howard University where he worked as a sports announcer for basketball games.

He began his broadcasting career in 1939 with the interview program, The Bronze Review, on WINX. The show was an instant hit and was soon aired on four stations in three cities. WINX did not want to give him a show because he would have been the first African American entertainer on the station and management feared losing part of their radio audience and sponsors.

He worked on a variety of shows on a host of stations including a rhythm and blues show, a sports show, and his signature variety show, The House that Jack Built. He moved to New York City where he used his fame to spread awareness and show support for the emerging Civil Rights Movement. In the mid-1950s he interviewed Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and aired his speeches on his programs.

In 1971 he produced the Miss Black Teenage America contest in Atlanta. The competition, now known as the Talented Teen contest, was an alternative to the Miss America contest and allowed girls of color to compete.

He co-founded the Inner City Broadcast Corporations one of the first broadcasting companies fully owned by African Americans. In 1995, he became the first African American to be inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Parade Day Bandits

Harrison, a young boy with a mop of unruly hair, was not yet old enough to attend the local school with his siblings. For that, he was delighted. The thought of shuffling off to a gloomy classroom with many kids making noise and a teacher telling him what to do was a nightmare. He’d rather be where he was, in his dad’s bustling barber shop, sitting high on the shoeshine chair overlooking the men…

View On WordPress

#barber story#Bed time#Bed time story#Bedtime story#blog#children story#clean stories#hero stories#LGBTQI#parade#short stories#short story#stories#story#story tellers#story telling#story time#story writer

0 notes

Text

Tongue Twister

Have you ever heard of tongue twisters? Do you know what they are?

Watch the video below and find out.

youtube

Tongue twisters (14:34)

Now read about tongue twisters and try to pronounce some of them.

Tongue Twisters to improve pronunciation in English

by Alex (EngVid – free English video lessons) Adapted

Tongue twisters are a great way to practice and improve pronunciation and fluency. They can also help to improve accents by using alliteration, which is the repetition of one sound. They are not just for kids, but are also used by actors, politicians, and public speakers who want to sound clear when speaking. Below, you will find some of the most popular English tongue twisters. Say them as quickly as you can. If you can master them, you will be a much more confident speaker.

Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers If Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers Where’s the peck of pickled peppers Peter Piper picked?

She sells seashells by the seashore

How can a clam cram in a clean cream can?

I scream, you scream, we all scream for ice cream

I saw Susie sitting in a shoeshine shop

Susie works in a shoeshine shop. Where she shines she sits, and where she sits she shines

Can you can a can as a canner can can a can?

I have got a date at a quarter to eight; I’ll see you at the gate, so don’t be late

You know New York, you need New York, you know you need unique New York

I saw a kitten eating chicken in the kitchen

If a dog chews shoes, whose shoes does he choose?

I thought I thought of thinking of thanking you

I wish to wash my Irish wristwatch

Eddie edited it

Willie’s really weary

A big black bear sat on a big black rug

Nine nice night nurses nursing nicely

So, this is the sushi chef

Four fine fresh fish for you

Six sticky skeletons (x3)

Which witch is which? (x3)

Red lorry, yellow lorry (x3)

Thin sticks, thick bricks (x3)

Stupid superstition (x3)

Eleven benevolent elephants (x3)

Two tried and true tridents (x3)

Rolling red wagons (x3)

Black back bat (x3)

She sees cheese (x3)

Truly rural (x3)

Good blood, bad blood (x3)

Pre-shrunk silk shirts (x3)

Ed had edited it. (x3)

We surely shall see the sun shine soon

Which wristwatches are Swiss wristwatches?

Fred fed Ted bread, and Ted fed Fred bread

0 notes

Text

Get best shoe shine services in nyc

CobblerExpress: Elevating Your Style with Top-Notch Shoe Shine Services in NYC

Your shoes are more than just footwear; they are an expression of your personality and style. A well-maintained pair of shoes not only complements your outfit but also leaves a lasting impression on others. To ensure your shoes always stand out with brilliance and elegance, look no further than CobblerExpress - your go-to destination for the best shoe shine services in NYC.

The Art of Shoe Shine: Restoring Beauty and Elegance

At CobblerExpress, we understand the importance of presenting yourself with confidence and finesse. Our expert artisans are passionate about the art of shoe shine, and they bring years of experience and dedication to each pair they handle. From classic leather dress shoes to trendy sneakers, we have the expertise to breathe new life into your footwear.

Why Choose CobblerExpress for Your Shoe Shine Needs:

Unparalleled Craftsmanship: Our skilled shoeshiners take pride in their meticulous craftsmanship. With keen attention to detail, they delicately restore the shine and texture of your shoes, making them look as good as new.

Premium Products: We believe in using only the best shoe care products to ensure the longevity and pristine appearance of your shoes. Our high-quality polishes, creams, and conditioners are gentle on your footwear, leaving them with a lasting shine.

Customized Approach: Every shoe is unique, and we treat them accordingly. Whether it's a vintage pair or a modern design, our shoe shine services are tailored to suit the specific needs of your shoes.

The CobblerExpress Experience:

Step 1: Assessment - Our expert artisans carefully inspect your shoes, noting any scuffs, scratches, or areas in need of attention.

Step 2: Cleaning - Your shoes are gently cleaned to remove dust and dirt, preparing them for the shine.

Step 3: Restoration - Using premium products, our shoeshiners work their magic, restoring the shine and color to your shoes.

Step 4: Finishing Touches - Any imperfections are carefully addressed, ensuring a flawless finish.

Step 5: Final Inspection - Before presenting your shoes to you, we conduct a thorough inspection to guarantee top-notch results.

Discover the CobblerExpress Difference:

Located in the heart of NYC, CobblerExpress is your one-stop-shop for exceptional shoe shine services. Whether you have an important event, a special occasion, or simply want to elevate your everyday look, our shoeshiners are here to help you step into elegance.

Visit CobblerExpress in NYC:

Experience the transformation of your shoes with the best shoe shine in NYC. Trust CobblerExpress for unmatched craftsmanship and personalized care for your beloved footwear. Elevate your style and leave a lasting impression with brilliantly shining shoes - visit CobblerExpress today!

Unlock the true brilliance of your shoes with CobblerExpress - where style meets perfection.

If you looking for best shoe shine nyc visit or contact us!

Contact us: (212) 867 7156

Visit us: https://cobblerexpress.com/product-category/shoe-shine-manhattan/

0 notes

Text

Goin' Back To T-Town: A Walk Along Black Wall Street

The Greenwood district in Tulsa, Oklahoma was once a Mecca for African American business. Then came the racist mob.

— Published January 20, 2021 | Kirstin Butler | From The Collection: The African American Experience

Art by Jordan Mitchell

In early 1921, you could spend an entire day in the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Oklahoma without once leaving its central thoroughfare, Greenwood Avenue. You might start with breakfast at Lilly Johnson’s Liberty Cafe before heading to Elliott & Hooker’s at 124 North Greenwood to buy a new suit or dress. If, say, the sleeves were too long, you could stop at H.L. Byar’s tailor shop across the street at 105 North Greenwood before picking up a prescription down the way at the Economy Drug Company. By then it was probably time for another meal, maybe a plate of barbecue eaten while perusing the pages of one of Greenwood’s two newspapers, the Tulsa Star or Oklahoma Sun. Playing pool at one of several billiard halls was an enjoyable afternoon pastime, or if glamour was more the order of the day, a photoshoot at A.S. Newkirk’s photography studio could be arranged. After dinner at Doc’s Beanery—the house specialty, smothered steak with rice and brown gravy—you could take in a silent film accompanied by live piano at the 750-seat Dreamland Theatre. Finally, a long and satisfying day would come to a close at 301 North Greenwood, when your head came to rest on a well-fluffed pillow in one of the Stradford Hotel’s 54 rooms.

Tulsa’s Greenwood district in early 1921 occupied about 40 square blocks of real estate in the city’s northwest corner. The district’s eponymous avenue ran for more than a mile through the community’s heart, the central artery of its livelihood and the place where inhabitants went to see each other and be seen. There and on adjacent streets, they also accessed the services of doctors (the district had 15), dentists, realtors and lawyers.

Black-owned businesses in Greenwood, including some of entrepreneur J.B. Stradford’s real estate properties, advertised in the Tulsa Star, 1914

Probably the most remarkable thing about all of these entrepreneurs, professionals and their clients was that they were Black. The Stradford hotel, valued at $75,000 ($2.5 million in today’s dollars), was founded by J. B. Stradford, one of Greenwood’s architects and the son of a formerly enslaved man. By 1921, Stradford's real estate portfolio included the hotel, his own personal mansion, two dozen rooming and rental buildings, bathhouses, shoeshine parlors and pool halls. Stradford was also a highly public critic of Tulsa’s racial oppression. In a 1916 petition to the city, he lamented a segregationist zoning ordinance passed that year: “[S]uch a law is to cast a stigma upon the colored race in the eyes of the world,” he wrote, “and to sap the spirit of hope for justice before the law from the race itself.”

The Dreamland Theatre anchored Greenwood Avenue at its locus of activity, the intersection with Archer Street. The theater belonged to Loula Tom Williams, who with her husband John also owned an auto repair garage and a confectionary. The Williamses moved to Tulsa from Mississippi in 1903 in pursuit of the American dream, which they realized in their theater and other business interests. The couple owned Greenwood’s first car, a 1911 Norwalk with leather seats, that would cost more than $50,000 today. Loula’s first foray into entrepreneurship, the Williams Confectionary, was a popular site for marriage proposals, presumably celebrated with a shared ice cream sundae.

Loula Williams, her husband John, and their son W.D. Williams in 1915. Credit: Tulsa Historical Society

Greenwood was a mecca for Black-owned businesses, fulfilling its community’s every want and need. Booker T. Washington, after whom the district’s high school was named, called it “Negro Wall Street.” Students at the high school studied Latin, bookkeeping and physics and were prepared to attend college at the best schools in the country that would admit Black students.

Some of Greenwood’s residents were the descendents of enslaved African Americans who had accompanied Indigenous tribes from the southeast during Native American Removal. Many came from states in the former Confederate South in search of opportunity (Greenwood actually took its name from a town in Mississippi). And by 1921, around 11,000 people, more than five times the population of the district only a decade earlier, had made Greenwood home. That population explosion mirrored greater Tulsa’s, where the booming oil business supported a rapidly growing metropolis with its own proliferating commercial interests.

Jim Crow segregation ensured that the two economies, those of white and Black Tulsa, remained separate. As a result, the money someone spent in Greenwood stayed in the community, circulating and recirculating from one business to another, one proprietor to the next. Those entrepreneurs then reinvested their earnings into the district and helped to develop it further.

In its upward mobility, Greenwood was an archetypal American neighborhood of the early 20th century. But that mobility made it particularly vulnerable to the malignant forces of American racism, and as Greenwood’s borders expanded, so did white Tulsans’ jealousy and resentment.

On May 30, 1921, a young Black Greenwood resident was arrested for allegedly assaulting a white woman in a downtown elevator. Thwarted in their attempt to lynch him , white Tulsa invaded the district with murderous intent the next day. White mobs, some of them deputized by official arms of the government, looted, set fire to and destroyed businesses, churches, schools, a public library and a hospital. The Dreamland Theatre was torched, as was the Stradford hotel and both of Greenwood’s newspaper offices. More than 1,200 homes were demolished. A thriving, vital place was reduced, in less than 24 hours, to piles of smoldering ash and rubble.

By today’s estimations, the Tulsa Race Massacre left at least 300 dead, many more injured, and 10,000 homeless. Eighty years later, in 2001, Oklahoma published an official report that equated the atrocity to a pogrom: “[T]he city of Tulsa erupted into a firestorm of hatred and violence that is perhaps unequaled in the peacetime history of the United States.”

Accounts from the era confirm this assessment. During the massacre, pioneering journalist Mary E. Jones Parrish escaped the combat zone of Greenwood’s commercial district with her young daughter, dodging bullets to make it to relative safety. After interviewing eyewitnesses, gathering photographs of the decimation and assembling a record of property losses, Parrish authored one of the definitive contemporary reports of the atrocity, Events of the Tulsa Disaster.

Mary Jones Parrish (left) and her daughter Florence Mary Parrish as pictured in Events of the Tulsa Disaster, 1922

Of her own personal experience of the massacre, Parrish wrote, “[s]omeone called to me to ‘Get out of that street with your child or you will both be killed.’ I felt it was suicide to remain in the building, for it would surely be destroyed and death in the street was preferred, for we expected to be shot down at any moment. So we placed our trust in God, our Heavenly Father, who seeth and knoweth all things, and ran out in Greenwood in the hope of reaching a friend’s home.”

Parrish also chronicled her community’s heroic efforts to rebuild what had been taken from them. They did so with next to no assistance. The $4 million in claims (more than $200 million in today’s dollars) filed by the massacre’s victims were all denied by insurers, who refused to make payments on damages incurred by what they deemed a riot.

In fact, Oklahoma’s city and state officials tried to prohibit Greenwood’s residents from reestablishing their lives. White Tulsa’s political leadership and development interests passed fire ordinances intended to prevent the district’s reconstruction. Black residents found a stalwart advocate in Buck Colbert Franklin, a Greenwood attorney who worked out of a tent in the massacre’s immediate aftermath. Franklin represented community members in a case against the city in which the ordinances were eventually deemed a denial of inhabitants’ property rights.

Buck Colbert Franklin (right) and I. H. Spears (left) with Secretary Effie Thompson (center), in their temporary tent office after the Tulsa Race Massacre, 1921. Credit: Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

By 1925, Greenwood stood again, rebuilt by its residents; their resilience was affirmed by the National Negro Business League’s selection of Tulsa as the site of its annual conference that year. White Tulsan’s racist attitudes toward African Americans remained, but Greenwood flourished nonetheless over the next several decades. The thirties and forties saw further economic development, and the community once again played host to high-profile out-of-town guests like Louis Armstrong and Nat King Cole.

Eventually, desegregation during the 1960s drew Tulsa’s African Americans beyond the district. As Greenwood’s residents spent their money elsewhere in the city, Tulsa planners hastened the neighborhood’s economic decline by using eminent domain to seize and demolish much of Greenwood’s commercial center. In 1960, for example, the city tore down the Dreamland Theatre building, which had become an Elks lodge and social center for the community. That destruction made way for Interstate 244 to cut directly through Greenwood Avenue and bisect the district’s central thoroughfare. Tulsa redlining and urban renewal policies hastened further deterioration. By 1980, Greenwood was largely a collection of deteriorating shuttered businesses and vacant homes.

In the last two decades, the area has been revitalized with new development. The benefits (and beneficiaries) of the recent economic growth remain controversial, however, with some community members arguing that gentrification further erases the area’s historic importance and public understanding of the massacre’s impact.

Now in 2021, a visit to the district might begin at 322 North Greenwood Avenue at the Greenwood Cultural Center, a nonprofit organization that fosters public awareness of Greenwood’s history. A memorial to Black Wall Street stands outside the center, yards from the Interstate 244 overpass. The marble slab was dedicated a generation ago on the massacre’s 75th anniversary and lists the hundreds of businesses once owned by African Americans in the district, among them the Dreamland Theatre and Stradford Hotel.

Above the columns of lost enterprise, a poem by massacre survivor Wynonia Murray Bailey is etched into the black stone. You might read the poem’s final stanza, accompanied by the sound of cars rushing by just 200 feet away:

“Greenwood! Lest you go unheralded,

I sing a song of remembrance

While sons of your bounty, loyal still

Place a headstone at the site of your victory.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Italian Cinema Watch List

Big Deal on Madonna Street 1958 (The film is a comedy about a group of small-time thieves and ne'er-do-wells who bungle an attempt to burgle a pawn shop in Rome)

Shoeshine 1946 (the film follows two shoeshine boys who get into trouble with the police after trying to find the money to buy a horse)

Four Steps in the Clouds 1942 ( This comedy tells the story of a married man who agrees to act as the husband of a young pregnant woman who has been abandoned by her boyfriend. Aesthetically, it is close to Italian neorealism)

La Notte 1961 ( the film depicts a single day and night in the lives of a disillusioned novelist (Mastroianni) and his alienated wife (Moreau) as they move through various social circles. The film continues Antonioni's tradition of abandoning traditional storytelling in favor of visual composition, atmosphere, and mood)

Marriage Italian Style 1964 romantic comedy-drama film

China Is Near 1967 (It is a satirical movie about the struggle for political and social power)

The Girl with the Pistol 1968 (The film tackled the themes of bride kidnapping and honour killing, which were still relevant in the Southern Italian culture of the time and normalized to some extent by Italian law, and had then only recently been challenged when Franca Viola publicly refused to marry the man who raped her)

The Garden of the Finzi-Continis 1970 (Historical drama adapts Italian Jewish author Giorgio Bassani's 1962 semi-autobiographical novel of the same name, about the lives of an upper-class Jewish family in Ferrara during the Fascist era)

Roma 1972 (semi-autobiographical comedy-drama film depicting director Federico Fellini's move from his native Rimini to Rome as a youth)

Scent of a Woman 1974 (Blind war veteran has a suicide pact with an old comrade but is thwarted with romance)

A Special Day 1977 ( Set in Rome in 1938, its narrative follows a woman and her neighbor who stay home the day Adolf Hitler visits Benito Mussolini. Themes addressed in the film include gender roles, fascism, and the persecution of homosexuals under the Mussolini regime)

I mostri 1963 (satirical comedy consists of short episodes that portray the evil and meanness of Italian society across all classes)

I nuovi mostri 1977 (The film, like the previous one, consists of short episodes that portray the evil and meanness of Italian middle-class society during the years of lead in the 70s)

Three Brothers 1981 (The Big Chill but with family)

And the Ship Sails On 1983 (It depicts the events on board a luxury liner filled with the friends of a deceased opera singer who have gathered to mourn her)

Summer Night 1986 (Italian comedy film directed by Lina Wertmüller- Love and Anarchy)

Cinema Paradiso 1988 (coming-of-age drama film Set in a small Sicilian town, the film centers on the friendship between a young boy and an aging projectionist who works at the titular movie theatre)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Shop online #shoes #shoestagram #shoesoftheday #shoesaddict #shoeslover #shoesforsale #shoeslovers #shoesph #shoeswag #shoeselfie #shoeshopping #shoesaholic #ShoesFashion #shoesporn #shoesaddicted #shoeshine #shoeshop #shoesale #shoesthailand #shoesmurah #shoesday #shoes4sale #shoestyle #shoesformen #shoesonline #shoesshop #ShoeStore #shoesofinstagram #shoesdesign #shoesgram https://www.instagram.com/p/CpjjIuUjIgu/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#shoes#shoestagram#shoesoftheday#shoesaddict#shoeslover#shoesforsale#shoeslovers#shoesph#shoeswag#shoeselfie#shoeshopping#shoesaholic#shoesfashion#shoesporn#shoesaddicted#shoeshine#shoeshop#shoesale#shoesthailand#shoesmurah#shoesday#shoes4sale#shoestyle#shoesformen#shoesonline#shoesshop#shoestore#shoesofinstagram#shoesdesign#shoesgram

0 notes

Quote

Who see a frozen skin the midnight of the winter and the hallway cold to kill you like the dirt ? where kids buy soda pop in shoeshine parlors barber shops so they can hear some laughing ? Who look at me ?

from Who Look At Me Who See by June Jordan

#June Jordan#Black geographies#here is melancholy#Black cultural productions#there is only wonder in the softness of joy

1 note

·

View note

Text

Guide to Flint Bishop International Airport (FNT)

Need to catch a flight from Bishop International Airport? Fly smarter with flight information, parking availability and taxi wait times.

Bishop International Airport (FNT) is only four miles from Flint, Michigan. Although the airport can handle international flights, most of its air traffic originates from within the United States and Canada.

In addition to numerous other amenities, including bars, gift shops, and ATMs, the airport is well-stocked with dining and retail options.

Flint Bishop Airport Airlines

Bishop International Airport has a few airlines that offer short-haul flights. Detroit and Cleveland are two large cities providing non-stop flight connections to Flint Airport. In addition, airlines that fly from Flint Airport are Allegiant, Southwest, American, United, and Delta.

Many travelers prefer to fly through smaller airports for a more intimate experience, pay fewer taxes and fees. The typical airfares at Bishop International Airport are now the lowest in Michigan, and the small airport's friendly atmosphere makes travelers feel relaxed.

Transportation Options from Flint Bishop Airport

Taxis: Flint frequently follows the lead of Michigan, the nation's automobile capital, making it extremely challenging to get around without a personal vehicle. Taxis, JCN limousines and cabs are a few taxi services that run from Bishop International Airport.

Flint Bishop Airport is conveniently situated and metered cabs are accessible outside the terminal.

Bus: Route 11 of the Mass Transportation Authority runs between the airport and the downtown bus terminal. From Monday through Friday, the service to and from the airport is offered hourly from 6 am to 6 pm.

MTA bus fares begin at $1.50 and can be paid cash on board or at the bus stop outside the terminal building.

Parking at FNT Airport

Short-term Parking costs $1 for 30 minutes, $20 for a day, and $140 for a week.

Long-term Parking is less expensive at FNT Airport; it starts at $2 per hour, $7 per day, and $49 per week. There is also an inexpensive parking area where you can park your car.

Economy Space starts at $2 per hour. Fees can go as high as $5 per day and $30 per week. A free shuttle service that departs from the economy parking lot every five minutes takes passengers to the airport.

Bishop International Airport Facilities

ATM and Communication Center: Public telephones and ATMs are located inside the Flint Bishop International Airport terminal.

Luggage: You can find a lost-and-found center inside the terminal building. Passengers enquiring about lost or damaged luggage should approach the airport helpdesk.

Conference and business: The airport has a free business center, offering power points for cell phones and other electronic devices, copy machines and individual workstations.

Shopping: Bishop International Airport has a range of shops selling gifts, reading material, cards, perfumes and chocolates.

Food and drink: Famous restaurants at Flint Bishop Airport include Samuel Adam’s Toasts Flints Bar, Gateway Grill and MSE Foods.

Other facilities: The airport has a disabled and a shoeshine service.

Wi-Fi: Get access to free Wi-Fi at Bishop International Airport terminals.

With FareOsky, you can take advantage of the lowest airfares while flying from Bishop International Airport. From the ease of parking to hassle-free security, FNT Airport is committed to making your travel comfortable and safe. For more information on the airport, airlines, and ground facilities, call FareOsky travel experts at +1-315-501-1144.

#bishop airport flights#flint airport#flint bishop airport#bishop airport#bishop international airport

0 notes