#cincinnati bootblack protective association

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Cincinnati Bootblacks Organized To Fight Free Shine Services By Local Merchants

The opening of a new shoe store in 1895 caught the attention of Cincinnati’s bootblacks, and they weren’t happy at all.

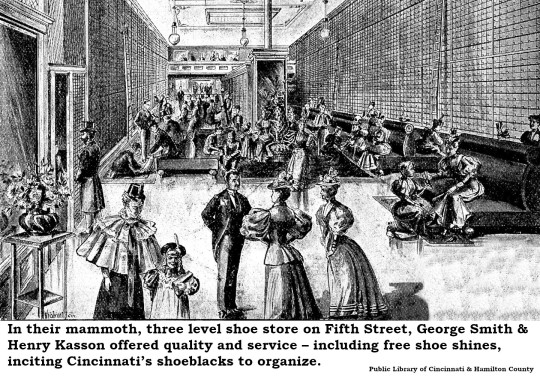

The Smith, Kasson & Co. store on the north side of Fifth Street, just east of Race, promised high quality footwear at prices affordable to the masses. George Smith, Henry Kasson and their partners indulged their customers with luxurious extras. An orchestra performed amid veritable gardens of potted plants. The décor was all of brass setting off maroon leather. An X-ray device assured a precise fit. The store offered, whether you were a customer or not, to shine your shoes for free. There was the rub.

Outside on the streets, dozens of bootblacks braved the entire panoply of Cincinnati weather to shine shoes for a dime, rarely pulling in a dollar a day. Some of the city’s “shine artists” occupied a stand in a barber shop or shine salon, but they were few and charged more.

To aggravate the situation, companies that manufactured shoe polish didn’t distribute through general stores. Shoe polish was sold only at shoe stores, forcing bootblacks to buy their supplies from the very establishments taking away their livelihood by offering free shines.

Christmas season in 1897 found Cincinnati’s shoeshine “boys” (most were grown men) on starvation rations as more and more businesses – not only shoe stores, but department stores as well – offered free shines. By January 1898, the bootblacks reached the boiling point. The raggle-taggle group announced a meeting and invited Mayor Gustav Tafel to attend. According to the Cincinnati Post, Mayor Tafel was sympathetic to the cause:

“The mayor has not patronized stores at which free shines were given, and either does the work himself or pays for having his boots polished. He favors the antifree-shine movement on behalf of the bootblacks.”

The Post, sensing an issue on which to build its reputation as the city’s progressive newspaper, provided extensive coverage of the dispute. In an editorial [1 February 1898] the newspaper announced its support:

“Everybody is talking about the bootblacks! Manly determination is always admirable. The assertion of the bootblacks that “Free shines is got to go!” carries with it the assumption of good argument. Give the bootblacks a fair hearing.”

Post reporters gathered quotes of support from prominent men, such as city councilman John Wahburn:

“A man does not expect free shoes. Why should he expect free shines? Let us all pay for both.”

The Post also collected endorsements from some of the city’s less-respectable celebrities, including Dan Bauer, who owned the notorious Majestic Concert Hall that the Post would rail against a few years later:

“Give the bootblacks what is due them. They are entitled to the business.”

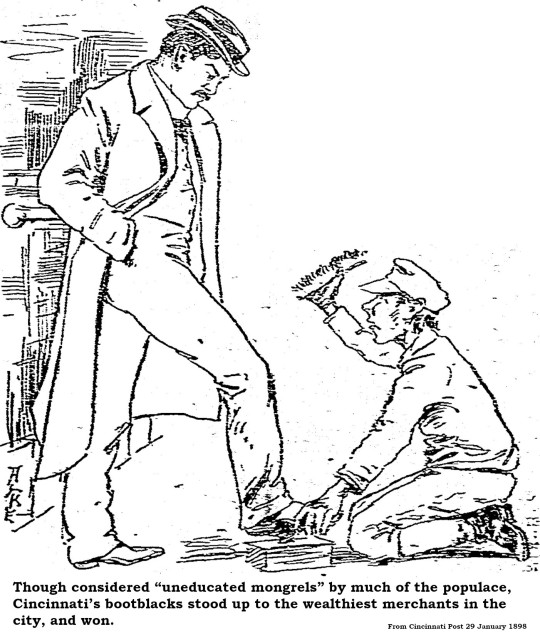

The Post also collected letters from bootblacks outlining their grievances. Some were printed with grammatical and spelling mistakes patronizingly preserved. One correspondent, William H. Schmidt, stated the case eloquently:

“Some people are inclined to think the bootblacks are a band of mongrels, uneducated and indifferent to circumstances. I want to say to these people that there are scores of us who are really worthy of better employment. We can’t get it, and accordingly make the best of our lot.”

On Tuesday morning, the first of February, the city’s bootblacks gathered at the College Hall on Walnut Street to discuss strategy. Temporary chair of the meeting was Harry Lemmon, who was not a bootblack at all, but an inspector at the Customs House. Lemmon introduced a motion to select a permanent chair when a disturbance halted the proceedings. According to the Post [1 February 1898]:

“There was some commotion in the hall. The doors burst open and in came 50 more bootblacks. One was playing a harp and others were cheering. It was five minutes before the election was resumed.”

The newcomers were a delegation of shoe-shiners who had rallied around their own celebrity, featherweight boxer Albert “Kid Ashe” Laurey. The Kid was no bootblack, but he was a popular athlete and was soon elected president of the meeting. Laurey, an African American, underlined the multiracial make-up of the bootblack constituency. Though the papers didn’t make much of the inclusive nature of the movement, it was probably the only integrated union in Cincinnati at the time, the other trades maintaining strictly segregated locals.

The lively group soon organized as the Cincinnati Bootblacks Protective Association, and drafted a petition demanding that Cincinnati merchants cease offering free shoeshines by the end of the week. In the back of the room, a man rose and announced that his employer, Mabley & Carew, would stop the practice immediately. Representatives of Rollman & Sons, Potter Shoes, the Foreman Shoe Company and Smith, Kasson & Co. were also present and agreed to end the service as well. In short order, the rest of the city’s merchants fell in line.

The association agreed to charge 10 cents for a shine and to levy dues of 10 cents a week to build up a fund for homeless and hospitalized members. The Cincinnati Post had one of the staff artists design an insignia for the group.

Although victorious in their initial battle, the war went on for years. By Thanksgiving, a few stores again began shining shoes as a complementary service. The Cincinnati Bootblacks Protective Association had gone largely inactive and had to be revived to counter this new threat. The association was revived again in 1901 after a couple years of inactivity, and yet again in 1905.

More disconcerting was a threat from within the bootblack community. A “trust” organized by unaffiliated bootblacks opened a shine parlor and only charged a nickel. The association sent a persuasive delegation to convince them that going out of business was a healthy decision.

#cincinnati bootblack protective association#cincinnati bootblacks#smith kasson comapny#cincinnati labor

4 notes

·

View notes