#shino: fortunately they had the right scroll

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

it would've been really funny is team 8 had stayed as murder-happy for the rest of the manga as they were in the forest of death. not even as a major plot point just as a running gag. anything happens and team 8's default solution is homicide.

#naruto#team 8#team kurenai#inuzuka kiba#aburame shino#hyuuga hinata#can you imagine if like. anyone had asked them about that#naruto: whoa how'd you guys get here so fast?#kiba: oh we just killed the first people we saw#shino: fortunately they had the right scroll#hinata: shame they were leaf nin but oh well#shikamaru: hey what the fuck#kiba: leeches and nets man. that's all you really need#hinata: i will treasure the sound of their screams ૮ ˶ᵔ ᵕ ᵔ˶ ა ⊹#hokage said ''teach these small children to kill'' and kurenai did exactly that#the nicest murder hobos you know

327 notes

·

View notes

Text

good luck, babe!

gojo & geto x idol!reader

summary : word has it that the y/n l/n is transferring to tokyo jujutsu high..

warnings : none

part 2?

"hey man did you hear?"

"what! no way.. you mean the idol?"

"duh. who else?"

"dude she's so cute!"

"i know.. i wonder if she's gonna date anyone here.."

What a crazy rumor, the Y/n L/n was transferring to Tokyo Jujutsu High? It had been all the talk lately, with girls hoping to get a signature and selfie from her, and guys hoping to win her attention and maybe even her heart.

"Hey Satoru." Suguru Geto who had been mindlessly scrolling on his phone, "Look at this." He directed his phone screen towards the white haired male showing a post made by a student from their school.

'Y/n L/n just arrived at Tokyo Jujutsu High!! She is totally enrolling here!!'

"I guess they weren't lying after all" he pulled his phone back to his view. "I wonder how many guys are gonna ask her out tomorrow. Tsk." Geto rolled his eyes, unbeknowst to Gojo Geto had been a fan of Y/ns since her debut. "Yeah, I bet you'll be one of them Suguru" Gojo teased. Geto tensed, "Huh?" Gojo smirked, "It's totally obvious you got a thing for her too. I've seen that rolled up poster behind your desk." It was true, Geto did have a poster from one of your albums rolled up behind his desk. He was truly just too embarrassed to let anyone know he had a crush on the idol every other guy in the country had one on.

"How did you- nevermind." Geto sighed and bowed his head in defeat. "Don't worry though, me too", Getos head popped back up.

"I actually have her debut poster."

The next day at school had everyone on their toes waiting for the moment to see her make her way through the halls. It was almost silent in the halls, everyone quiet waiting to catch a glimpse of her. But then

the bell rang.

and no sight of Y/n L/n.

Was it a misunderstanding? Had y/n really not transferred? Students walked to class disappointed without saying they were fortunate enough to have caught a glimpse of the idol.

"I'm so sorry I'm late!" you clasped your hands together in an apology to your personal driver, Shino.

"No needs for apologies Miss L/n" he says as he opens the back door of your limousine. You nervously smile at him and enter the vehicle. Truth be told, you weren't late on accident it was on purpose. When you visited the school yesterday to get your enrollment papers you had learned a few things from your new principal.

The Satoru Gojo and the Suguru Geto were students of Tokyo Jujutsu High. You had most definitely heard about the two many times from your mother and father who had been friends with your principal for years.

"They're. quite troublesome." Yaga would say. "But they are fine young men and sorcerers nonetheless." At one of your parents' dinners with the man, he had shown a selfie of the two, along with their female partner Shoko. And you couldn't deny the way you could feel your pupils dilated at the sight of both boys. You were blushing in the back seat worrying about seeing the two in person.

Before you knew it, you had arrived in the front of the school. "Here we are Miss L/n." You twitched, "Already..?" Shino chuckled, "You'll be just fine Miss L/n." You sighed and opened the car door with a bowed head. "Thanks Shino.." You faced the school with a determined stance, hoping to not come across the two boys on your first day.

Pushing through the front doors of the school you were greeted with Principal Yaga, who smiled greatly at you. "Y/n. Good to see you. You do know you're late right?" You twitched, "Oh yeah.. sorry about that Mr Yaga!" Yaga smiled, "No worries. I'll cut you some slack since it's your first day Y/n. Anyways-"

The door swinging open cut Yaga off, walking through the doorway came a boy about 6'3 maybe taller. He was so tall it was almost crazy how high you had to look up to see his face.

Your eyes instantly widened.

And the moment Geto opened the door he was met with Yaga staring at him oddly, almost like he had just interrupted him. Geto shrugged it off and walked through the doorway about to ask him a question that almost instantly left his mind the moment he slightly turned his head to the left to lock eyes with a girl he knew all too well.

Geto froze, not sure whether to feel embarrassed or keep staring. He eventually shook his head and apologized for barging in. "Geto I was actually just about to mention you to Miss L/n, I'm sure you know her" Geto swallowed hard, "Yes, of course I do" Geto smiled at Y/n, recieving a awkward smile back.

"You're going to be her personal body gaurd for today." "Huh?"

#jujutsu kaisen#anime fanfic#anime#jjk#gojo satoru#geto suguru#suguru geto#geto x reader#gojo x reader#satoru x reader#suguru x reader#jjk x reader#jjk fanfic#jjkfic

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Random Thoughts on the Practice of Chanoyu (13): the Use of the Ro during the Furo Season (Part 1).

A while ago, someone asked about how the ro might be used during the furo season. So -- because I think it might be good to take a short break from our discussions of tsuzuki-kane [續きカネ] and soe-oki [添え置き] -- I decided to use a recent chakai from the month of May, as a way to illustrate this matter.

Before looking at the tori-awase of the chakai, however, it might be good to repeat something that has been said here before: before Jōō created the irori, the only way chanoyu was being performed was with the furo.

Things had already started to move away from the daisu by that time (it appears that Shino Sō-on was already placing the furo on a round shiki-ita, which he arranged beside his family’s chū-ō-joku -- it seems that it was from Sō-on’s idea that Jōō derived his square ko-ita, by cutting a square within the circle); but the furo itself, even if Japanese-made, was still a very expensive object (and, in the case of the lacquered clay Nara-buro and mayu-buro, one that could easily be damaged as well).

It was in order to eschew the entire issue that Jōō recognized the communal cooking pit in the common room of the farmhouse as a potential alternative; and once it was perfected, his intention was that it be used all year round as the ultimate realization of the wabi aesthetic. Indeed, the furo was not used in the small room setting until after Rikyū entered Hideyoshi’s household (which he did between the end of 1582 and early 1583) -- the first example of which was when the small unryū-kama was used in the large Temmyō kimen-buro that was arranged on the Yamazato-dana [山里棚] (a tana resembling an inakama take-daisu, though with the front right leg removed and the ten-ita cut into a roughly triangular shape, both of which were necessary accommodations if the large Temmyō-buro was going to be placed on such a tana) in Hideyoshi’s Yamazato-maru [山里丸] (the 2-mat room that was constructed in the boathouse on the inner shore of the moat that surrounded Hideyoshi’s Ōsaka castle).

The first public reveal of this “new” way of serving tea in the small room appears to have been when Rikyū brought the same furo and kama to Kyūshū, and placed them directly on top of the wooden lid that he made to cover the mukō-ro in the tearoom that he had constructed in the “tea village” on the grounds of the Hakozaki-gu [筥崎宮], during the summer of 1587. So, prior to that occasion, only the ro had been used in the small room setting, irrespective of the season or temperature.

Turning now to the chakai that was held on May 14:

The kakemono was written by the Korean monk Seok-jeong of the Gumgang Temple in Busan. Seok-jeong s’nim is very famous for his cartoon-like sketches of Buddhist figures. This scroll features a painting of Bodhidharma, with his left hand raised, and the colophon jwa dan shib-bang [坐断十方] (za dan jippō; “from your seat scatter the ten directions” -- the meaning is to shed our misguided perceptions of reality through the repudiation of our ego, by means of the cultivation of samadhi via seated meditation).

The hyōgu [表具] is fairly typical of scrolls made for modern-day tea use, in terms of its proportions and the selection of the fabrics used; however, one point of note is that the handles are made from polished (but unpainted) natsume wood.

The chabana consisted of white tsuri-gane-sō [釣鐘草] (Campanula takesimana) and murasaki tsuki-gusa [紫露草] (Tradescantia ohiensis), in a coarsely woven bamboo basket.

The kama was a medium-sized unryū-gama [中雲龍釜].

The mizusashi was brown Seto ware, one of a group of mizusashi that Jōō ordered from the Seto kiln during his middle period (for use on the fukuro-dana -- they are thus associated with the early use of the ro, and are of the ideal size for chanoyu).

The name of this particular mizusashi is “Odori Hotei” [踊り布袋] (“dancing Hotei” -- Hotei being one of the seven Gods of Good Fortune, with his dance symbolizing unrestrained joy and contentment).

The chawan was black Raku-ware (of the Ō-guro [大黒] variety); the ko-bukusa [小フクサ or 古フクサ] was sewn from a variety of meibutsu-gire [名物裂] known as tan-ji chū-keitō-kinran [丹地中鷄頭金襴].

The chashaku is named “Yoka” [餘花] (which means flowers -- usually the word refers to cherry blossoms -- that bloom several weeks after the season has passed).

The chaire was made of Bizen-yaki [備前焼], by Kimura Yūkei Chōjūrō [木村友敬長十郎], the fifteenth generation master of the original Imbe kiln. Since the Edo period, it had been the practice of his family to make copies of all of the meibutsu chaire; this is his copy of the chū-ko meibutsu [中古名物] Seto hyōtan-chaire [瀬戸瓢箪茶入] named Kūya [空也].

The shifuku was sewn from a piece of a summer kimono material (from the early Shōwa period), with the design called seikai-ha [青海波].

The futaoki is an iron kakure-ka [隠れ家] (this shape of futaoki is usually called gotoku [五徳] today); and the koboshi is made of lacquered bentwood (this koboshi was favored by Ryōryō-sai Sōsa [了々齋宗左; 1775 ~ 1825], the ninth generation iemoto of Omotesenke).

The reason why I decided to begin by mentioning the tori-awase was to give this explanation context -- because the selection of utensils necessarily has an impact on the temae.

According to Jōō, when the ro is used all year round (which was his original idea for chanoyu in the wabi tearoom), during the spring and summer, the ro-buchi [爐緣] should be of unpainted wood¹, while during the autumn and winter, it should be lacquered (in the wabi setting, this meant rubbing with lacquer, or the use of one of the less fastidious techniques, was preferred over something like shin-nuri).

As for the question of incense, when Jōō began to use the ro, the only kind of incense used in the tearoom was made from crushed incense wood -- jin-kō [沈香] or byakudan [白檀]² -- which was drizzled along the length of the dō-zumi [胴炭]³ (so the incense would continue to perfume the air over the course of the gathering). Since byakudan is the smell of the furo season, it is entirely appropriate to use it in the ro during the furo season (and that is what was done on the present occasion)⁴.

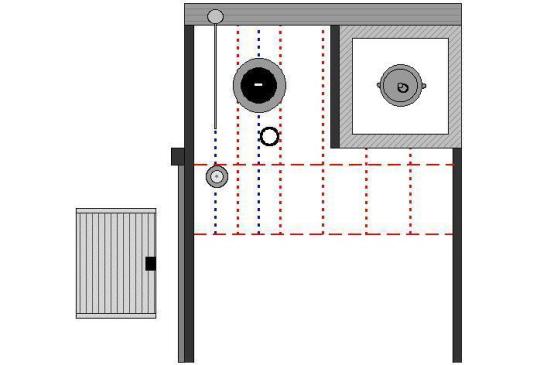

As for this particular two-mat room, the length of the guests’ mat has been emphasized by the 8-sun 2-bu wide board (which functions as an ita-doko), while the utensil mat was made to look smaller by replacing the far end of the tatami with a board 2-sun 5-bu wide. This arrangement where the ko-ita extends completely across the mat predated the appearance of the tsuri-dana: the board allowed the hishaku to be displayed on the mat (as here), without having to rest on the futaoki⁵; the kōgō was also commonly displayed on the board (according to the records of Rikyū’s own gatherings).

Placing a pair of fusuma to the left of the utensil mat mirrors Jōō’s own arrangement of the utensil mat of his Yamazato-no-iori [山里ノ庵]⁶. The fusuma allowed the host to lift the various utensils directly onto the utensil mat⁷. For that reason, a tana was always placed on the far side of that fusuma, to keep the utensils from sitting directly on the floor⁸.

The kama is an unryū-gama, which was suspended from the ceiling on a susu-dake ji-zai [煤竹自在]. Most of the unryū-gama made since the Edo period have the handle of the lid made of a small ring. The reader should notice the direction in which the ring-handle faces in the drawings. This orientation allows the ring to be pinched from the sides, between the thumb and first finger of the right hand, when it is picked up. This is the traditional way for such handles (which predated the unryū-gama by at least a century) to be oriented. The host should be sure to open the lid of the kama slightly before calling the guests back to the tearoom, to let the built-up steam escape.

The mizusashi is centered on the left side of the mat, with the futaoki placed in front of it (so that it is in between the two kane). The cup of the hishaku rests on the board (5-bu from the wall), with the handle running along the kane; and with the chaire displayed on the near side of the yū-yo [有餘] (this is referring to the 2-sun wide space that extends across the mat in front of the mukō-ro: nothing should be placed in the yū-yo).

The chawan and koboshi should be prepared as usual (in the case of the chawan, the chashaku should be oriented facing upward -- this was Rikyū’s rule); and, together with the go-sun-hane [五寸羽]⁹, they should be arranged on the tana (in the katte) in a manner that will facilitate their being lifted onto the utensil mat at the beginning of the temae.

The goza begins with the host opening the door, and bowing to the guests. Then he slides across the sill on his knees (according to Rikyū, people should not stand up in the small room; moving about is done on the knees). The host immediately turns back to face the open doorway, and slides the fusuma closed¹⁰. (It is important that he do this every time¹¹, since otherwise it will be impossible to open the other fusuma, to access the utensils placed there). Then he turns back to fact the shōkyaku, and the two exchange words¹².

The the host turns to the left, and slides forward toward the temae-za, where he pauses briefly to appraise the condition of the fire¹³. He should also take note of the other utensils, making sure that they are still in the same places as when he arramged them on the mat (and if not, he should rectify things now).

After turning to face the fusuma¹⁴, and sliding it open, the host lifts the chawan onto the utensil mat (placing it in the lower left-hand corner of the temae-za). Then the koboshi is taken out, and the fusuma is closed.

The host turns to face the far end of the mat again. First the chaire is moved so that it overlaps the kane that is to the left of the central kane “by one third¹⁵.” The kane, in this case, is the me to the right of the futaoki¹⁶.

The the host then moves the chawan to the left side of the chaire. The foot of the chawan should be immediately to the right of the endmost yang-kane (which is 5-me to the left of the futaoki)¹⁷, with the back of the chawan’s foot touching the front edge of the yū-yo.

Next, the futaoki is picked up (with the right hand) and placed on the right side of the mat. Here its kane is on the fifth me from the heri; and it should be 2-sun from the front edge of the ro-buchi.

Then the host picks up the hishaku with his left hand¹⁸, and reholds it with his right. Holding the hishaku horizontally in front of his body, above his knee-line, he first moves the koboshi forward with his left hand (so it is 2-sun 5-bu below the lower edge of the temae-za), and then rests the hishaku on the futaoki.

According to Rikyū, the hishaku should be held so its cup approaches the futaoki at an angle (so that the corner is fitted into the depression in the center of the futaoki¹⁹); the hishaku should be brought into contact with the futaoki gently, and then the handle should be lowered to the mat²⁰. The handle should rest on the heri, with its right side to the left of the heri’s middle²¹.

After placing the hishaku on the futaoki, the initial arrangement is completed, so the host and guests bow for the sō-rei [総礼].

Following the sōrei, the host pauses momentarily, to collect his thoughts. Then the chawan is picked up and moved in front of his knees (the left side of its foot should be immediately to the right of the central kane, while the far side of its foot should touch the front edge of the yū-yo -- this is necessary so there will be sufficient space in front of the chawan for the chaire). Then the chaire is moved between the chawan and the host’s knees, with the chaire resting squarely on the central kane.

The host unties the himo, and then removes the shifuku in the manner appropriate to the kind of chaire he is using. The chaire is placed down on the mat again, and the shifuku is smoothed out, and then placed on the far side of the yū-yo -- with the mouth facing forward (according to Rikyū’s instructions), and the uchi-dome of the himo pointing toward the center of the mat.

The host then removes the fukusa from his obi, folds it, and tucks it into the futokoro of his kimono (or, if he is not wearing a kimono, he tucks the folded fukusa into his belt, near his right hip²²).

Then the host picks up the chaire, and while holding it over his left knee (the heel of his left hand can rest lightly on his left leg at this time, for security), he takes out the fukusa. Raising the chaire to the center of his body (above his knee-line), he wipes the lid, and then the shoulder, with the fukusa. Then, after returning the fukusa to his futokoro (or tucking it into his belt) once again, the chaire is lowered to the mat. Its back side should touch the front edge of the yū-yo, while it should not cross the kane on the left (this is a memory of the shiki-shi [敷き紙], where nothing resting on it was allowed to project beyond its edges).

The host then moves the chawan forward (so that its back side touches the front edge of the yū-yo). He takes out his fukusa, and places it on his left palm. Then he picks up the chashaku, cleans it with the fukusa, and rests the chashaku on top of the chaire. After which the fukusa is returned to his futokoro (or slipped under his belt).

Next, the host lifts the chasen out of the chawan and stands it on the mat on the same (yin) kane on which the futaoki is resting.

The the host takes out his fukusa, and wipes the lid of the mizusashi (because, on this occasion, the mizusashi has a lacquered lid) -- in front of the handle, on the far side of the handle, and then from the handle off the right side. (The case where the lid is made of the same material as the mizusashi was the original situation. Because the idea of making a lacquered lid for a mizusashi only appeared around the middle of the fourteenth century, it was felt that certain changes to the temae were necessary -- to make the use of a lacquered lid “more difficult²³.”) Then the lid is picked up with the right hand, reheld from the side with the left, and then leaned against the left side of the body of the mizusashi (the lid should touch the mat 3-me from the left edge of the foot²⁴).

Opening the mizusashi at this time is necessary because the kama is an unryū-gama: because of the small size of this kama, the water boils away very quickly²⁵. Thus, it is necessary to constantly replenish the kama with cold water, starting as soon as the lid of the kama is removed.

The host then picks up the hishaku with his right hand, and reholds it in his left hand so that it is above his left knee (it was at this time that it was held in the “kagami-bishaku” [鏡柄杓] position: opening the lid of the kama was felt to be akin to revealing the host’s heart -- the state of his samadhi -- to his guests, and so the hishaku was held like a mirror onto which his samadhi was reflected). He then takes the chakin out of the chawan and uses that to protect his fingers while lifting the hot lid off the kama. (As mentioned above, the ring-handle of the lid is pinched from the sides between the host’s thumb and first fingers -- with the chakin between the skin of his fingers and the metal of the ring.) The lid is lowered to the futaoki.

When the ring is held in this way, it will be pointed toward the lower right-hand corner of the temae-za. This leaves the side of the lid facing toward the middle of the mat completely unobstructed (meaning that there is no need to flip the ring over, the way certain modern schools teach²⁶). After placing the lid of the kama on the futaoki, the chakin should be rested on the lid (as shown in the drawing).

Then, after reholding the hishaku with his right hand, two hishaku of cold water are immediately added to the kama (to replenish what has boiled away since the sumi-temae), followed by a yu-gaeshi [湯返し]. After which, a quarter hishaku of hot water is dipped from the kama and poured into the chawan.

The host then immediately adds one hishaku of cold water to the kama, followed by a yu-gaeshi; after which the hishaku is rested on the kama as usual.

Then the host picks up the chawan, rotates it three times above the koboshi, discards the water, and returns the chawan to the mat in front of his knees.

The hishaku is picked up again, and a half hishaku of hot water is poured into the chawan. Once again, the host immediately adds a full hishaku of cold water to the kama, performs another yu-gaeshi, and again rests the hishaku on the kama²⁷.

The lid of the mizusashi is then closed, and wiped with the host’s fukusa in the same way as before it was opened.

Then the hishaku is picked up, and held with the left hand above the host’s left knee (kagami-bishaku, once again); and, again using the chakin (the lid will still be quite hot), the lid of the kama is picked up, and placed on the kama, closing it completely. Then the chakin is placed on the lid of the mizusashi, and the hishaku is again rested on the futaoki.

Then he picks up the chasen and rests it in the chawan, leaning against the far rim of the bowl. Then he performs the chasen-tōshi in the usual way, stands the chasen on the right side of the mat as before, and discards the water.

He dries the chawan with the chakin²⁸, places the chawan down on the mat in front of his knees, and returns the chakin to the lid of the mizusashi.

In the usual way, the host picks up the chashaku, and then the chaire, and transfers enough matcha to the chawan to make one portion of koicha (according to Rikyū’s way of doing things).

After returning the chaire and chashaku to their places on the left side of the mat, the host picks up the hishaku and holds it above his left knee (kagami-bishaku, again). Then, picking up the chakin, he again opens the kama, resting its lid on the futaoki (and then placing the chakin on the lid, as shown above).

At this time, during the furo season, the host once again rests the hishaku on the kama -- without doing anything else.

Then -- because this is the furo season, so cold water has to be added to cool the kama slightly before preparing koicha²⁹ -- the lid of the mizusashi is again wiped with the fukusa (as before), and then opened.

The host then adds one hishaku of cold water to the kama, followed by a yu-gaeshi. Dipping out a full hishaku of hot water, he pours an appropriate amount over the matcha in the chawan, and returns the rest to the kama. (At this time he does not add any more cold water, since he already did that before dipping out the hot water.)

Picking up the chasen, the host blends the matcha and hot water together to make koicha³⁰.

After the host has finished blending the koicha, the chasen should be placed on the left side of the mat, on the endmost yin-kane; it should also be in line with the center of the chawan.

_________________________

◎ While the details of the temae narrated here agree with Rikyū’s own writings, they might not necessarily conform with the way the modern schools teach these things. In every case where the temae practiced by the school with which the reader is affiliated differs from what is written here, it would always be best to follow your own school’s preferred methods.

¹On this occasion, the ro-buchi was made of sawa-kuri [沢栗] -- a variety of chestnut wood that grows near streams in the wild. This wood, which is beige, with a slightly darker grain, was the kind of ro-buchi preferred by Jōō and Rikyū for this purpose.

²Before the modern period, byakudan with a reddish tinge was preferred (since it has a more subtle aroma than white byakudan). However, this kind of byakudan is rarely seen today.

³Crushed incense wood is what is used in the temple setting.

Chips of incense wood, such as are usually used today, were originally made to perfume the breath while speaking (a chip was held under the tongue for this purpose).

It is unclear from the historical records when the change from crushed incense to wood chips was made.

⁴Neri-kō, as a way to perfume the air in the tearoom, did not come into use until a number of years after Jōō began to use the ro in his 4.5-mat tearoom.

When neri-ko was used throughout the year, the blend appropriate to the particular season seems to have been preferred:

◦ bai-ka [梅花] was used in spring;

◦ ka-yō [荷葉] was used in early summer;

◦ ji-jū [侍従] was used during the rainy season;

◦ ka-yō [荷葉] was used again during the period of intense heat;

◦ kikka [菊花] was used in early autumn;

◦ raku-yō [落葉] was used from late autumn to early winter;

◦ kuro-bō [黒方] was used in the depths of winter.

The reader should understand that this is only one system. Other series (in which the various blends were sometimes associated with different seasons) are also described in the classical literature (and these tend to reflect period-specific preferences -- which may or may not be tied to the availability of certain of the ingredients, most of which had to be imported from the continent).

This sequence cited above appears to follow the traditional division of the tea year into seven seasons (which primarily was used as a guide to the selection of the utensils): shun [春], u-zen [雨前], u-chū [雨中], u-go [雨後], shū [秋], shō-kan [小寒], dai-kan [大寒].

⁵In the early days, people were still using the treasured futaoki that had been placed on the daisu and other tana-mono, which were objects of appreciation. Resting the hishaku on the board permitted the guests to look at the futaoki without having to touch any of the other utensils*. __________ *If, for example, the hishaku was resting on the futaoki, since there was no tana in this kind of room, the question became what to do with the hishaku while looking at the futaoki. Placing it on the floor would dirty it.

Also, if the hishaku was resting on top of it, it is likely that the guests would not be able to see the futaoki clearly, and so not recognize what it was.

⁶The Yamazato-no-iori [山里ノ庵] was Jōō’s first 2-mat daime room. It was built in late 1554 or early 1555, at the same time as Rikyū’s Jissō-an [實相庵].

⁷Moving back and forth between the utensil mat and the katte, while carrying in the utensils one by one, was something that was supposed to be done only in the shoin setting.

In the wabi room, it was preferred that once the host reached the temae-za, he should not leave again until the service of tea was finished (this seems to have been Jōō’s idea from the beginning).

⁸These drawings show Rikyū’s tabi-dansu [旅簞笥] (which was used with the door removed, since the fusuma itself fulfills that function), since that tana is less deep than most of the others -- though any sort of mizusashi-dana could be used. In Jōō’s day there was a preference for high-quality mizusashi-dana with four legs, since those tana (fine though they might be) could not be used on the utensil mat.

The tabi-dansu was designed as a portable dōko (for use in a larger room that had not been constructed as a dedicated tea room -- meaning it had neither a ro, nor a built-in dōko). At the siege of Odawara (in 1590), Rikyū used the tabi-dansu when serving tea during Hideyoshi’s conferences with his generals. The furo-kama (the small unryū-gama in the large Temmyō kimen-buro), mizusashi (kiji-tsurube), and futaoki were arranged on a naga-ita. After everyone had taken their seats, Rikyū entered carrying the tabi-dansu in front of his body. He placed it on the mat to the left of the one on which the naga-ita was arranged*, opened the door, and then turned to face the naga-ita†.

The tabi-dansu was made so that it could be used with any chaire, except for a large katatsuki resting on a chaire-bon selected according to Jōō’s method (that is, the tray would be 3-sun larger than the chaire on all four sides). A tray of that size will not fit inside this tana. However, Jōō’s tray for a ko-tsubo chaire (such as Rikyū’s “Shiri-bukura” chaire [尻膨茶入]‡) would fit. A large katatsuki would have to be used with a tray selected according to Rikyū’s calculations (in other words, the tray would be 2-sun larger on all four sides). A clear understanding of the distinction between these two kinds of bon-chaire will be very useful for anyone who hopes to make sense of the aesthetics of Rikyū and his followers. ___________ *In, for example, an 8-mat room, it seems that Rikyū performed the temae on the left of the two mats in the middle, with his assistant (who conveyed the bowls of tea to each guest) seated on the next mat.

†This is completely different from how the tabi-dansu is used today.

‡Which he used during the most intimate conversations between Hideyoshi and one of his officers, or when receiving an envoy from the Hōjō defenders.

⁹The go-sun-hane [五寸羽] is the small-sized habōki that is used on a daime utensil mat.

In the small room, the utensil mat is always considered to be a daime (regardless of its actual size), since the lower 1-shaku 5-sun of a full-length kyōma tatami was always yū-yo in the small room setting.

¹⁰Rikyū preferred to reach across his body. Thus, when opening the fusuma (which, in the example shown, would slide from the host’s right to left), the host would reach up to the hand-hold with his left hand and, after opening the door 1-sun or so, push the fingers of his left hand through the aperture, and so pull the door open to the middle of his body. Then he would lower his left hand and continue pushing with his right hand until the door was open.

The door should not be slid open completely. Rather the panel that was just opened should be left projecting 1- or 2-sun beyond the edge of the other panel, so it can be grasped easily when it is time to close the fusuma again.

¹¹Unlike in the versions of the furo-season usage taught by many of the modern schools, where the fusuma by which the host enters and exits the utensil mat is occasionally left open -- ostensibly for the purpose of keeping the tearoom from becoming too hot -- this cannot be done in this room (since it will make it impossible for the host to open the other fusuma, through which he accesses the objects arranged on the tana behind it).

Furthermore: in Rikyū’s period the tea gathering was considered to be an extremely private affair, meaning that the doors would always be closed (and locked, where locks were available).

¹²Their discussion, at this time, is usually focused on the chabana, and the objects arranged on the utensil mat.

¹³According to Rikyū, the condition of the fire is the thing that determines what can be done during the gathering -- and a master chajin was one who could build a fire during the sumi-temae (always at the beginning of the shoza) that would keep the kama boiling until the service of usucha was finished, with the sound of the kama persisting (albeit weakening) until the guests left the room.

While the host pauses here to inspect the fire, he also should also check and see that the initial arrangement of the other objects was not changed by the guests in any important way (and if it was, he should put things aright before proceeding further). Unlike today, when scolding and hypercriticality have become important activities by means of which the guests attempt to control each other (so their behavior conforms with the norms established by their particular school), in Rikyū’s time the guests were free to do pretty much whatever they liked, and they often picked up the various utensils to look at them closely when they first entered the room for the shoza, or the goza. (Indeed, Jōō actively encouraged them to open the door of the ji-fukuro, or the dōko*, so that they could look inside at that time, only asking that the last guest close the door again when they were done.) However, since the host will also use the positions of the various utensils to guide his hand when moving new objects onto the utensil mat, his faith in the initial arrangement should be confirmed before he begins doing anything else. __________ *Only in the case of the mizuya-dōko was this sort of thing strongly condemned by Rikyū (meaning that he began to assert the host’s authority only during the last two or three years of his life, since the first mizuya-dōko was the one he built in his Mozuno ko-yashiki [百舌鳥野小屋敷], which was completed in late 1588 or early 1589).

¹⁴The fusuma at the left of the temae-za had a similar function (indeed, it was the inspiration for) the door of the dōko. The original dōko was simply a locally made wooden box, with a shelf suspended across the middle, that was a wabi alternative to the imported mizusashi-dana that had been all the rage during Jōō’s middle period. Once the size of this tana had been fixed, it was only a matter of time before the opening, and the fusuma sliding in front of it, were reduced to being no larger than necessary. (This, of course, was only possible in a 4.5-mat room, where the dōko is some distance removed from the host’s entrance. In this particular two-mat setting, however, it would be difficult, since the host’s fusuma must slide behind the other so that he can get into and out of the room, meaning that the height of the two doors must be the same.)

¹⁵This is the way the idea is expressed in things like the Nampō Roku. What it actually means is that the foot of the chaire is located immediately to the right of the kane, so that the body of the chaire extends across the kane (in the case of the meibutsu chaire, and meibutsu chawan, the foot is usually one-third of the maximum diameter of the body); the back of the chaire should touch the front edge of the yū-yo, as if it were an invisible wall -- it is fairly easy to visually extend the front edge of the ro-buchi across to the mat to this point, allowing the host to gauge the width of the yū-yo without much difficulty*). ___________ *When it comes time to move the chawan beside the chaire, the back of the chaire is the visual guide that helps him determine how to orient the chawan.

¹⁶This is why the placement of the futaoki -- centered, as it is, in between the kane -- is so important: it shows the host where both the yin and the yang kane are located -- since the me on both sides of the futaoki represent those kane.

Rikyū said that the kane, especially in the wabi small room, should be recognized by counting the me on the mat*, and this is what he meant. __________ *In entry 50 of Book Seven of the Nampō Roku, it was alleged that Rikyū marked the kane on a sort of measuring tape, which he then hid in his futokoro, bringing it out when he was arranging the utensils on the mat at times when other people were not present; but this sort of action is contraindicated by his own words.

Using a measuring tape was a machi-shū practice that the machi-shū of the Edo period subsequently strove to validate by also putting the device into Rikyū’s hands. Rikyū’s point, however, was that the wabi setting does not demand such exactitude -- and, indeed, such excessive care is actually out of place there. It is better for the objects to be aligned with the me of the mat -- that is, so the side facing the guests is seen to be so aligned with the me (since placing objects so that their edges are in between me looks careless).

¹⁷The kane were derived from the shiki-shi [敷き紙], which accounts for some of the more arcane conventions associated with them -- such, as in the case of the endmost yang-kane, the idea that things are bound by them (objects placed on the shiki-shi were not suppoed to project beyond the edge) -- though this is only really a rule during the actual preparation of the tea. This is why the chaire must be wholly within the confines of the kane, since the purpose was that any tea that might fall off of the chaire* would be caught by the shiki-shi (which was originally used only once, and then discarded after use), rather than soiling the mat. ___________ *In the early days, the fear of contaminating the tea with lint meant that the chaire was rarely cleaned as diligently as today. As a result, it was not unheard of for tea to remain on the shoulder of the chaire, from where it could become dislodged, and so fall onto shiki-shi.

¹⁸This is done so he does not have to reach over the chaire and chawan with his right arm to access the handle of the hishaku, which would be wrong.

¹⁹The depression in the top of a futaoki is called a hi [樋]. In the early days its presence (or absence) was considered to be the most critical feature of any object that the host wanted to use as a futaoki.

²⁰Audibly striking the hishaku against the futaoki, and then dropping the handle so it bounces several times before coming to a rest* were machi-shū practices adamantly deplored by Rikyū -- not only because they were annoying, but because they could loosen the joint between the hishaku’s handle and its cup, resulting in the hishaku leaking during the temae. __________ *This kind of thing was viewed as a kind of “natural magic” by the Koreans of the middle ages (and even today), since the interval between taps decreases by exactly half with each repetition. Nevertheless, while this is so, it is out of place during the temae.

According to Rikyū, the cup should be gently rested on the futaoki, and then the handle should be gently lowered to the mat -- even in the most wabi setting.

²¹The outermost 5-bu on all four sides of the mat is yū-yo.

²²This was explained by Rikyū.

While Rikyū preferred to wear a kami-ko [紙子] (a kimono sewn from heavy paper treated with persimmon juice -- making it a dark brick-red color), many people of his period preferred to wear Korean-style clothing, consisting of a pair of loose pants tied at the ankles with strips of cloth, and secured around the waste by a narrow cloth belt, and a separate shirt that was tied at mid-chest with a sort of cord attached to the hems, both of which were made from undyed cloth (usually cotton or hemp, so they were between off-white and a pale beige).

In either case, a jittoku [十德] (a hip-length overgarment, sewn from black diaphanous silk, and traditionally worn by monks on formal occasions) was worn over the other garments before entering the tearoom.

²³This will likely strike the modern reader as an odd way of thinking about the matter, since the higher temae are invariably more complicated than the lower.

But this is a problem that arose (perhaps intentionally) during the Edo period. The original daisu temae (the so-called gokushin-temae [極眞手前]) was very simple, with all actions dictated only by necessity. Originally, only a mizusashi with a lid made of the same material as the body was permitted, and this lid was cleaned (with a damp chakin) when mizusashi was filled with water when the daisu was being prepared for use.

But when the lid of the seiji unryū-mizusashi [青磁雲龍水指] was broken during the attack on Yoshimasa’s storehouse (yet the body was left completely unscathed), Yoshimasa felt it was too much of a waste for such a precious object to be thrown away. So he had a wooden lid carved and painted, to resemble the original celadon lid. But it was found that dust clung to the lacquerware in a way that it never did to pottery or metalwork*, and this is what necessitated the wiping of the lid with the host’s fukusa every time it was going to be opened or closed (for fear that the dust would fall into the water, thereby contaminating the contents of the mizusashi).

The original usage was basic. The later modification was more complicated, because it took into account the peculiarities of the new lacquered lid. __________ *Or perhaps it might be better to say that the dust was simply more obvious on account of the material that was used. Nevertheless, because people were now more sensitive to this issue, a remedy had to be devised, and that is how the procedure came into being.

²⁴This angle of inclination is considered to be the most stable, and so less likely for the lid to slip and fall on the mat.

²⁵The original unryū-gama was the small unryū-gama, which holds three mizuya-bishaku of water* when full. However, that kama was really too small to be used over the ro (because, on account of the larger fire and greater heat, the water will boil away too quickly). Later a slightly larger version of this kama was cast for use in the ro (it holds four mizuya-bishaku of water), and this is what is now known as the medium unryū-gama (chū unryū-gama [中雲龍釜]). It was made for use with the ro, and in that setting it was supposed to be used in the same manner as the small unryū-gama was used on a furo. ___________ *A mizuya-bishaku -- this is a standardized measuring device -- holds 400 ml of water when filled to the rim (though in practice, it probably holds a little less when water is being poured into the kama). Consequently, the small unryū-gama holds around 1200 ml (when filled to the bottom of the kan-tsuki -- as was the original rule, though some of the modern schools have changed this), and the medium unryū-gama holds 1600 ml.

²⁶Originally the ring-handle was pinched between the thumb and first finger, as described here. The early ring-handle did not have a projecting leg (that keeps the ring from lying flat on the face of the lid). Consequently, the host had to lift the ring up with his fingernails (cultured persons of the upper classes, both men and women, effected long fingernails during that period*). As a result, holding it from the sides was the most logical way to do things.

Ring handles of this sort were first seen when old bronze mirrors came to be used as lids for kama during the late fifteenth century†.

These mirrors had a small knob, with a hole pierced through it, in the middle of the back side (the front side was polished as smooth as the technology of the day permitted, and then silvered); and a cord was threaded through that hole (which was then braided to make a handle by means of which the mirror could be held up -- this can be seen in the photo). When mirrors that had lost their silver were used as lids for kama, a cord was impractical (since it would get wet from the steam, and so get too hot to handle; cords of this sort were also susceptible of catching on fire).

After chanoyu came to be practiced by members of the samurai caste (whose physical training meant that they could not have excessively long fingernails), the little leg was added to the ring, to make catching hold of it easier.

Unfortunately, by the Edo period the machi-shū had forgotten how this was supposed to be done, and began putting their index finger through the ring (meaning that the ring will have to face toward the host at all times). Because the ring was now taking up the very part of the lid where the chakin would have to sit, Sōtan and his followers got into the habit of flipping the ring over, so that the side of the lid facing him was unobstructed. Of course this not infrequently resulted in the host forgetting to flip it back over before the end of the temae‡ -- which was another point about which the guests could gossip later. __________ *Long fingernails meant that they did not have to do any sort of manual labor.

The way of doing things like handling a writing brush always took into account the fact that the user might have long fingernails.

†This was because, since bronze was not yet being made in Japan, this was the only way to get lids of that metal for the iron kama that were being cast in Japan. (When these old mirrors lost their silver, there was no way to repair them, so they became useless. Using them as lids gave them a new purpose.)

‡If the ring was not flipped back, it would be very difficult to pick up the lid.

²⁷This is a special feature of the unryū-gama temae: as a result, while the amount of water in an ordinary kama decreases over the course of a temae, in the case of the unryū-gama, it slowly increases after each time hot water is used.

²⁸In Rikyū’s temae, the chakin was used as it was, to dry the bottom, lower side, and upper side of the interior of the bowl, then the front rim and back rim, when wiping the omo-chawan [主茶碗]; it was not draped over the side while the bowl was rotated -- that was done only when drying the kae-chawan [主茶碗] (since doing so is more dangerous).

Thus, in Rikyū’s temae, the chakin was immediately placed on top of the mizusashi, without any need to refold it.

²⁹The reason for adding water to the kama before preparing koicha during the “furo season” is this: once the ambient temperature begins to remain above freezing throughout the day and night, the strength of the stored tea begins to decrease each time the cha-tsubo is opened (as more and more of the volatile components evaporate when the jar is opened to the air). Therefore, the temperature of the water has to be lowered, otherwise the aromatics will dissipate completely before the bowl even reaches the guest.

We are not really so sensitive to this as were the people of Rikyū’s time, and the reason has to do with the way the matcha is processed. Even if you visit a tea plantation and are served a bowl prepared with freshly ground tea, the simple fact is that the machine-operated tea mills heat the leaves too much when they are being ground (the millstones become too hot to touch). Thus, so much of the flavor has already evaporated even before the powdered tea is sealed in its tin (the aroma of grinding tea spreads even out into the parking lot -- that is how much is lost).

In Rikyū’s day, the tea was ground in a hand mill, and when turned by hand (even by the young men of the household to whom this task was usually delegated), the stones do not even become warm to the touch. Thus the tea retained virtually its full strength and aroma until it was finally put into the chawan, and boiling water was poured over it.

Before Jōō created the irori, when the furo was used all year round, this simple rule could not be followed. Rather, from the beginning of winter in the Tenth Month (when the new jars of tea were cut open for the first time) until the end of the Second Month (around the end of March), fully boiling water was used to prepare koicha. From the beginning of the Third Month until the end of the Ninth Month, the kama was brought to a full boil (by closing the lid of the kama during the chasen-tōshi), and then its temperature was reduced appropriately by adding cold water to the kama before dipping out water to make the tea. While one hishaku of cold water would suffice for most of this time, from the end of the rainy season the host had to take especial care -- because even though the weather begins to cool from late August, the tea will have already been so damaged during the intense spell of heat, that it will have been all but ruined. Thus water no hotter than absolutely necessary should be used for the remainder of the year. (That is why Rikyū used a tsutsu-chawan during that season -- so he could cool the kama as much as possible, yet be assured that the tea would not cool further between his hands and those of the guest.)

Chanoyu, especially wabi no chanoyu (where the focus was supposed to be wholly on serving the best possible bowl of tea -- rather than amusing the guests with a room full of expensive utensils*), was a much more involved process than the modern, mechanical, mindless methodology might lead one to conclude. ___________ *Unfortunately, this idea has declined to the point where a majority of the practitioners of chanoyu today do not like koicha, and only endure it because of the utensils and food, despite the fact that most private gatherings take place in what would be described as a wabi small room (which includes the inakama 4.5-mat room).

³⁰According to Rikyū, hot water should be added to the chawan only once -- so the koicha could be offered to the guest as quickly as possible. Pausing to add more hot water (as Jōō did -- not only when preparing koicha, but when making usucha, too) will delay this, meaning that more of the volatile flavor components will have had the chance to evaporate before the bowl actually gets to the guest.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Part Two

To The Highest Bidder

Previous Chapter

The Tsunade-mandated date

The dinner took place in a small beach town three hours south of Konoha. Standing outside of the restaurant, Kakashi’s mouth watered. He checked that the loops of his paper mask were secure before stepping inside. Tsunade had reserved the entire restaurant for the Charity Dates. The restaurant had been sectioned off for privacy with flowery curtains. Aburame Shino stat in a chair near the entrance, nodding at Kakashi when they made eye contact.

Kakashi’s mission scroll had mentioned that there would be a date supervisor on the scene to report. Tsunade wanted to ensure both parties would be on their best behavior during the dinner. Kakashi believed it was Tsunade’s way of ensuring the participants showed up in their mission-mandated attire. Yes, the restaurant had a nice beach theme going on. But Tsuande could have let them wear a shirt along with the swim trunks.

“Reservation B,” Kakashi said to restaurant worker who standing at the podium. One of the interior pockets of his jounin vest was rubbing against his nipple; he resisted the urge to scratch it.

“Right this way,” the server responded, who didn’t seem at all surprised about Kakashi’s random attire.

The server parted the curtain to allow Kakashi to step in, to an empty room with a table set for two. A cheery fire in the corner of the room gave enough light to see, but still provided a sense of privacy and coziness. And a line of sconces lined the wall with hanging flowers. Kakashi unzipped his jounin vest and draped it over the seat of his chair before sitting down.

Kakashi rubbed his chest, trying to get rid of the goosebumps that had erupted over his skin. Moving aside the pineapple centerpiece, he picked up the menu.

“You’re still wearing your mask.”

Kakashi skimmed the entrees, looking up when Sakura’s footsteps stopped.

Oh

“Is that a coconut bra?” Kakashi asked as he took in Sakura’s attire, or lack of it. He suddenly felt a lot less self-conscious about being shirtless.

“This isn’t a real date so I thought I would have a bit of fun and go along with the theme.” Sakura twirled in place, causing her bathing suit sarong to flutter. “It’s not too much, is it?”

Too much?

“It’s perfect,” Kakashi replied after finding his voice. He stared at her chest as she took a seat, his mind open to new, wonderful possibilities. He poured Sakura a glass of water as he took a deep breath, trying to ground himself back into reality. This was Sakura, after all. No need to lose his cool yet.

“You better not try to charm your way out of showing me your face, Kakashi.” Sakura waggled her finger at him.

“Maaa, that’s not fair. I am required by Tsunade to be charming during this dinner. If I’m not, she might stick me in the missions’ office to take reports for three months.” Kakashi slid the menu in her direction after pointing out what he wanted to the server. “I’ll take the mask off when dinner is served. This face is only for you.”

Sakura bit her lip and looked away. “What did I just say about the charm? You don’t have to do that. This isn’t a real date,” she said as she looked down at the menu.

Kakashi raised an eyebrow. That was an odd statement to say twice. It sounded an awful lot like Sakura was trying to convince herself. He observed her as she scanned the menu. Sakura had grown her hair out since the last time he saw her seven months ago. She had curled her hair in soft waves that came down mid-back. It was pinned away from her face with a large tropical flower behind her ear. And while it wasn’t unusual for Sakura to wear make-up, her choices this time around were definitely bolder.

‘Especially her lipstick,’ Kakashi thought, as her lips formed a pout.

Sakura plucked at a lock of hair by her ear. “Is there something wrong with my face? You’re staring.”

“I was”—Kakashi hesitated, hoping he was reading the signals right— “admiring.” He tilted his head to the side. “It’s not just the Tsunade-mandated charm. You really do look lovely.”

A blush bloomed on Sakura’s face as she laughed; Kakashi watched the flush crawl down her neck. He wondered what it would take to make it trail further down to her chest. Feeling warm, he polished off his ice water.

Damn coconut bra.

Fortunately, the server stepped into the room to deliver their food. Kakashi used the opportunity to evaluate his situation. On one hand, he could be reading the signals wrong. He might ruin their amicable, but somewhat distant, relationship. Tsuande wouldn’t care about it and put them together on frequent missions, leading to months of awkwardness. On the other hand, Sakura was very handsy with him during the bidding auction.

On a third hand, they both weren’t wearing shirts, so it could be the beach setting.

Sakura squirmed in her seat as the server returned with their plates, practically vibrating in anticipation for his face reveal. Kakashi chuckled as the server vanished behind the curtain. “Impatient?” he asked as tugged at one of the earloops.

“I’ve been waiting half my life for yo—” Sakura’s jaw dropped as the mask came off. Kakashi smiled, delighted with her reaction. “Unngh. You—uh—houfff.” She covered her face with her hands.

Kakashi chuckled as he reached for his chopsticks. There was no use in letting his food grow cold while she recovered. He caught her peeking at him between her fingers as he took a bite of food. She squeaked.

“Is something wrong?” Kakashi asked, wondering why she was acting so timid. Where was the woman who had struck fear in him the night of the auction?

Sakura took her hand away from her face to glare at him. “Don’t take the innocent route. You know very well how attractive you are.” She moaned, a sound that little to stave off Kakashi’s growing interest. “What the hell is up with your teeth? Are you an Inuzuka?” She poured some alcohol into her cup and slammed it down.

Kakashi nibbled at his roasted eggplant. “My nose is sensitive because my great-grandmother was a branch member. I have to wear a mask because don’t have any of their clan jutsu to control it.”

“You’re so hot,” Sakura said miserably as she refilled her glass. “I wish you were wearing a shirt. How the hell can I concentrate on my food when you nipples are right there?”

Kakashi raised an eyebrow. Interesting. Charity Auction Sakura had definitely been on the tipsy side. Maybe Sober Sakura was just a little shy? He raised an elbow on the table so he could rest his chin in his hand. “I’m sure you’ll manage. I would love to hear about your six-month trip to Mist. Did you try the mackerel?”

Sakura laughed, the tension in her shoulders melting away. “Oh my god, that stuff is disgusting.”

“It’s definitely an acquired taste. The only people who like the seasoning they used are from the country.”

“It was a long six months. I was making antidotes the entire time, and it was so boring. Most of it was stuff that I had learned how to make five years ago. I spent everything I earned on that mission on this date—I mean— this dinner.” Sakura poked at her food. “Ino had bought the dinner ticket and a bidding paddle for me. I had tossed the paddle in the lobby trashcan so I wasn’t planning on bidding. I had to dig it out of the trash when you changed the rules. I came back into the room and heard Tsunade was about to close the bidding. I didn’t know what was the final number, so I bid as high as I could afford. If anyone deserved to see your face, it was me, and not some old bat from another country.”

“I hope you think it was worth every Ryo,”—Kakashi gave her a sly smile— “to have me for the entire night.”

Sakura’s chopstick froze halfway to her mouth as her jaw dropped. “What?” Kakashi’s responded with a wink. “Oh my god, are you flirting with me?”

Kakashi kept eye contact as he finished chewing his food, and then deliberately trailed his eyes down to stare at her breasts. He was fascinated by her fuzzy bra. Was it made from a real coconut or was it synthetic? His hand twitched, eager to find out. “Yes. Do you want me to stop?”

Sakura blinked, her mouth stilled parted. Her eyes flickered down to his chest; Kakashi flexed his pecs.

Sakura laughed in delight, her hand rising to cover her growing smile. She turned away to look at one of the sconces on the wall. He waited patiently for her response as he continued eating his rice. If she said no, he would continue as they always had, sticking to conversations about missions and jutsu. After dinner, he would put his jounin vest back on, and walk her to room as he told her goodnight. Then, he would avoid her for three months so the awkwardness could pass.

If she said yes, Kakashi would do everything he could to find out what was hiding behind her coconuts.

Sakura turned back to him, her hand returning to her chopsticks. He smiles on her face had turned dangerous, a coy smirk that Kakashi was compelled to return.

“Do you want me to stop?” he repeated as Sakura took a bite of her food. A bit of sauce ended up on the corner of her mouth.

“No,” Sakura replied, slowly dragging her tongue over her lip to wipe up the sauce. Kakashi clenched his fist at the provocative gesture; there was no reason for her to act like that so early into dinner.

Sakura fluttered her eyelashes. “Is something wrong, Kakashi?” She took another slow bite, her mouth parting to show her pink tongue.

“No,” Kakashi said, his voice deeper than had been a moment ago. He hated that she was already pulling at the delicate threads of his sanity and it was only the main course. The erection that had been threatening to grow since she walked in the room could no longer be willed away. “More water?” He raised the pitcher, topping off his own cup.

“I’m good,” Sakura pointed to the bottle of sake next to her.

“Excellent.” Kakashi poured the pitcher of ice water directly on his chest, wincing as the cool water pooled onto his crotch. He grabbed one of the ice cubes in his lab and rubbed it along his upper body, giving extra care to each of his nipples.

Sakura was panting from across the table. “Oh my god!” Her hand reached for the sake and she slammed the rest of the bottled back. “I’m done with my dinner, are you?”

Kakashi took a look at his half-eaten plate. “I think so.” The ice cubes in his lap clattered to the floor when he stood. He held his jounin vest in front of his crotch to hide the damp spot. “Lead the way, Sakura."

PART THREE

158 notes

·

View notes