#shinchoukouki

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ieyasu's reception in Azuchi hosted by Mitsuhide, Shinchoukouki Account

It just occurred to me that I never did post what the Shinchoukouki account say about Ieyasu's reception that Mitsuhide did.

And now, Lord Tokugawa Ieyasu traveled to the metropolitan provinces to express his gratitude to Nobunaga, as did Anayama Baisetsu. Declaring that these visitors must be treated with the utmost hospitality, Nobunaga issued the following orders: “First of all, fix the highways. Daimyo holding provinces and those holding districts—go to the places where our guests will be lodging, make sure that everything is prepared as splendidly as possible, and give them a feast!” [...]

[...] On the 15th of the Fifth Month, Lord Ieyasu left Banba and arrived at Azuchi. Nobunaga had decided that the Taihōbō Rectory would make a suitable place for Ieyasu to stay and ordered Koretō Hyūga no Kami (Mitsuhide) to take care of the entertainment. Koretō laid in the most unusual delicacies in Kyoto and Sakai and organized a stupendously magnificent feast, which lasted for three days from the 15th to the 17th.

(The Chronicle of Lord Nobunaga, page 463-464)

That was it. No problems were described, and everything seems to be great. Then Hideyoshi's report of the Mouri army came in, and Mitsuhide was sent away to prepare to march out.

The host duties for the rest of Ieyasu's visit was taken over by someone else, naturally, but not necessarily because Mitsuhide did anything wrong.

Advancing from Aki Province with their forces, Mōri, Kikkawa, and Kobayakawa took up positions confronting Hashiba in the field. [...] Nobunaga sent itemized orders to Hashiba Chikuzen’s camp. Then he designated Koretō Hyūga no Kami (Mitsuhide), Nagaoka Yoichirō, Ikeda Shōzaburō, Shiokawa Kitsudayū, Takayama Ukon, and Nakagawa Sehyōe to spearhead the offensive, and immediately gave them leave. On the 17th of the Fifth Month, Koretō Hyūga no Kami returned from Azuchi to his castle at Sakamoto. Each and every one of the others likewise went back to his home province and prepared for the campaign.

(The Chronicle of Lord Nobunaga, page 464)

There were actually other issues that did occur in this visit, namely a Noh dancer did not perform well and Nobunaga threw a huge fit over it (with Ieyasu still there watching, apparently). However, it was after Mitsuhide had already gone and it has nothing to do with him. The dance incident happened on the 19th, and Mitsuhide already left on the 17th as shown above.

Something I'm a bit curious about is that the Azuchi Castle historical maps had labelled a site as "Ieyasu-kou's residence", located across from Hideyoshi's residence. When I searched for the Taihoubou, it appeared to be located in the town area, and not part of the castle complex like the vassal residences.

I wonder if Ieyasu brought so many attendants that he had to be lodged in a different residence that is bigger? The marked site of Ieyasu's residence, based on the remaining foundation stones, seems to be on the smaller side.

#oda nobunaga#tokugawa ieyasu#akechi mitsuhide#japanese history#sengoku#sengoku period#sengoku jidai#sengoku era#samurai#samurai history#shinchoukouki#the chronicle of lord nobunaga

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In terms of the story, this is why I said in my previous post the narration sounds like it was intended to mean that Nobunaga is dead.

However, the part that says “he walks further into the fire” technically only means he just went deeper in to the temple (away from the door Mitsuhide came in from). Based on how Japanese architecture works, as long as the fire doesn’t block off all the outer walls of the temple, I personally think there is still a possibility for escape. Perhaps the crumbling rubble only obstructed Nobunaga from Hideyoshi and Mitsuhide’s view, and he just headed towards a different part of the temple and escaped from that other side.

Conspiracies aside, let’s talk about the fire itself.

The Shinchoukouki document described that Nobunaga set the place on fire, and some interpreted that it’s precisely so that his body would be destroyed and that Mitsuhide would not be able to desecrate it.

It’s a common practice for samurai to cut off the enemy’s head and put them on display as a mark of their achievement. Lords and commanders who dread this fate might request their vassals to bury or hide their bodies after they commit seppuku.

Shinchoukouki also described that Nobunaga’s heir had requested exactly that of his vassals. After he committed seppuku, his remains was immediately buried in the mansion he was holding fort at, and was also never found.

There’s a lot of novels, movies, and dramas where Nobunaga specifically asked Ranmaru to light the fire, but I think it’s just drama flavouring (in line with the popular trope that Ranmaru was Nobunaga’s personal assistant of sorts). I don’t know if such a thing was ever explicitly documented in any historical account.

There is another record, purportedly a written transcription of the narration of one of the Akechi soldiers, that said that fire broke out from the kitchens. This implies a completely accidental fire.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

So there’s this info where it says that back when Motonari and Nobu were still friends, Moto asked for help jumping on his enemy’s back, and Nobu sent Hide out and the text says Hide mowed down almost 20 castles in just 2 weeks and I’m like WTF??????

Maybe those are just small castles so it’s not as hard to do, but bro. That’s still kind of scary?????

The castles are in Tajima province, not easy to map modern locations to the old province maps, but I think it’s somewhere here I think:

And they had moved out from Kyoto.

So if this info is true, this is why I salt on the people who keep saying that Hideyoshi couldn’t have been the commander of the Kanegasaki Retreat because like... why? Hideyoshi is clearly a high enough ranking commander to be approved of going on a solo mission out in another province. Akechi is a shogunate official besides, so Hide is probably the commander of the Oda troops and Shinchoukouki didn’t count Akechi because even if he was there, he’s not part of the “Oda army”.

Stop downplaying Hideyoshi to make a fuss about how Uhmayzing Akechu was. They can both be amazing together, stop it.

Also, doesn’t that mean like... if Hide really wanted to overthrow Nobunaga he could darn well have done it anytime? Like, aside from how he’s clearly scary as hell (as mentioned above), apparently Nobunaga stays over in Nagahama every now and then when he needs to use the boat docks to cross the lake, so Hide could just stab him dead one night and nobody could do anything???

I mean, I suppose the argument was that he’d need the conspiracy for the purpose of public opinion. If he rebelled personally, it would’ve given him negative presses. IDK man.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

News say artillery power did make a difference in Nagashino, but maybe not in the way that you might think

For quite a long time, it’s the popular story that Nobunaga decimated the Takeda in Nagashino because he readily embraced guns when other clans didn’t. Despite how it’s being severely disputed in the scholarship, this story is still repeatedly trotted around, especially in the fandom/pop culture talking spaces.

First, a little credit to the “old stories”, as it were. The famous scene from Kurosawa Akira’s Kagemusha, of the Takeda cavalry units moving out one by one, and each getting mowed down by gunfire—that’s not entirely without basis. Its source was in fact the Shinchoukouki:

The battle raged from sunrise of the 21st of the Fifth Month to the Hour of the Sheep [around 2 p.m.], the action bearing East by Northeast. The Takeda army attacked in relays, but its soldiers kept being shot down, and its manpower gradually drained away to nothing.

(The Chronicle of Lord Nobunaga, page 226)

There’s actually a longer description in the text, detailing a narrative that’s very similar to the movie. One unit moves out, gets gunned down, and had to withdraw. The next unit moves out, gets gunned down too, and had to back off too. This kept going until about 5 units marched out, and eventually Katsuyori gave up and the Takeda army all withdrew.

So what was wrong in the “pop culture” story? For one, the Shinchoukouki text described this terrible move as being the Takeda’s last ditch attempt after they’re already surrounded. Meaning that there’s other strategy and battle manoeuvres that’s already taken place before this showdown finally happened. The Oda victory is not entirely thanks to the guns, although it does help. It would be a tougher win if the soldiers had to actually run out there and have a melee fight.

For another, it’s not like the Takeda or the other clans didn’t have guns. You’d have to ask why and how there were people making so many guns in the first place if it wasn’t a popular weapon that everyone’s actively using.

Lastly, just because the text says that the soldiers were “shot down”, it doesn’t automatically mean a rotating volley technique had been used.

Here’s the breaking news: This article from Yahoo News reports that what the Oda had that made the difference was likely having more bullets (possibly of a much higher quality as well).

The news report describes that research into bullet remains has identified particular kinds of bullets unique only to the Sengoku and very unlikely to have come from later periods in time, and these were found in Nagashino. From the studies conducted, the theory was that the Oda had a massive supply of high quality lead bullets that the Takeda didn’t.

In that time, lead was not only used for bullets, but also other smithing needs. As such, supply of domestic lead, it says, did not quite meet the necessary numbers, so they had to imports bulk loads from overseas. This is something that the Oda had advantage of, thanks to their Nanban connections and having monopoly of Sakai.

The Takeda, on the other hand, was not able to supply enough lead bullets that they were forced to melt down copper money to make the bullets with. Talk about literally burning down cash. The news reports that a letter artefact of Katsuyori ordering this had been found previously, and analysis of the copper bullets found in Nagashino has found that they have the same chemical composition as the Ming copper money that’s in circulation at the time. These copper bullets were judged by some to be inferior than the lead bullets.

And even after doing all that, there’s still not enough of bullets in supply on the Takeda side. The news then reported that after this defeat, Katsuyori learned from that mistake and circulated a new order decreeing that the army must supply at least 200 bullets for each gun that they have.

In conclusion, this new theory says that even though both sides had guns, the Takeda side ran out of bullets too early on and their artillery was then rendered useless. The Oda army, who still had plenty of bullets to go around, was able to keep on shooting the enemy to the ground.

I think this is a part of the conversation that didn’t really occur to a lot of people in the Sengoku gun conversations, especially in casual/non-academic or fandom spaces. Without the bullets and the gunpowder to light it up, you can have a million guns and they'd be no better than a very heavy stick.

There’s new books about the updated research of Sengoku gun usage, and based on the reviews and summaries, it’s basically "Never mind the guns. The drama is in the trade war surrounding the gunpowder (and the bullets too)". Among many other things, the tactics also include actually sending letters to the missionaries asking them to help tell the European traders to not sell gunpowder to a very specific entity.

#Nagashino#Battle of Nagashino#artillery#musket#arquebus#oda nobunaga#takeda katsuyori#shinchoukouki#samurai#Akira Kurosawa#kurosawa akira#sengoku#Sengoku Era#Sengoku period#nobunaga oda#katsuyori takeda#takeda cavalry

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

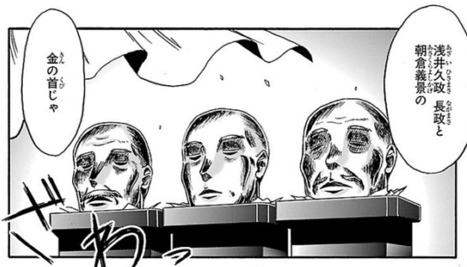

Were the infamous skulls actually “skulls” or “heads”?

Some time ago, I was browsing the Unification/Azuchi-Momoyama volume of Kadokawa’s educational manga series on Japanese history. In a rather unique move, the scene of the presentation of Azai and Asakura’s heads depicted the whole heads gilded in gold instead of the usual skulls.

Indeed, the Shinchoukouki describes the heads as 首 kubi, which is the term used to usually mean heads. The description of the skull had come from the Azai Sandaiki, which mentioned that the heads had been “stripped of the flesh” before the lacquering.

The Azai Sandaiki was considered not entirely reliable, and the Japanese encyclopaedia labels it as more of a book of fables and folklore rather than a certified historical account. It makes sense that whoever worked on this manga then thought that maybe the heads are just heads based on the Shinchoukouki.

However, just because the Shinchoukouki doesn’t say “skulls”, doesn’t mean that they aren’t skulls. There are various words for “skull” (髑髏, 曝頭, 曝首, etc), but they’re not necessarily daily vocabulary that people would normally use at the time.

So, if the Azai Sandaiki is not wholly reliable and the Shinchoukouki wasn’t clear, were they actually skulls or heads, though?

I personally believe that the answer is “skulls”.

Here is why I believe that it makes more sense for the heads to be cleaned down to skulls before lacquering and gold leafing them:

The Azai father and son and Asakura Yoshikage were killed around September-October of 1573. After which, the heads were put in public display in Kyoto, where they were probably exposed to the weather and perhaps animals or insects.

Asakura Shikibu no Daibu brought Yoshikage’s head to the Ryūmonji in Fuchū [...] Nobunaga entrusted Yoshikage’s head to Hasegawa Sōnin, who brought it to Kyoto, where it was put on exhibition. (The Chronicle of Lord Nobunaga, page 198)

Nobunaga sent the heads of the Azai, father and son, up to Kyoto, where they were put on display at a prison gate [...] (The Chronicle of Lord Nobunaga, page 199)

This narration is corroborated by the existence of a letter Nobutada had sent, describing that Asakura’s head was being delivered to Kyoto for presentation (the letter was sent before the Oda army defeated the Azai).

While there’s no description of how long were they put on display for, it’s quite likely that they were going to be there for quite a while. These head displays were meant to serve as a proclamation of achievement and/or warning, after all.

By the time of the 1574 presentation, the heads had probably already deteriorated, and shall we say it’s not going to be a pretty sight?

It has been argued that what Nobunaga did was a form of the head presentation ceremonies typically done with enemy heads post-battle. This ceremony highly values aesthetics, and it’s demanded for fresh heads to be washed, perfumed, and even decorated with makeup.

Even supposing it actually isn’t a formal “head presentation”, the three heads were being displayed in a banquet. Skulls are going to be much more presentable than deteriorated heads (surely we all know zombies look horrible), and so I consider it to be the more likely option.

Not to mention that there is also the additional possibility of the heads wearing down to the bones naturally, precisely because of having been exposed to the elements. Perhaps, then, when the Oda vassals retrieved them from their “display” in Kyoto, they were already turned into skulls.

#japanese history#samurai#sengoku#Sengoku Era#Sengoku period#oda nobunaga#Azai Nagamasa#Azai Hisamasa#Asakura Yoshikage#azai sandaiki#shinchoukouki

7 notes

·

View notes

Video

Since this was also mentioned in the article with the Frois citation, I thought I'd revisit this.

Back when I first posted this clip, someone had asked if this was based on true account (the comment seems to have since disappeared, so maybe the person deactivated their Tumblr).

It was indeed based on a reliable account, as it was mentioned both in the Shinchoukouki and in the diary of Matsudaira Ietada (a Tokugawa vassal).

I really feel silly to have forgotten this was there, but here's the passage from the English translation of the Shinchoukouki:

On the 20th of the Fifth Month, Nobunaga ordered Korezumi Gorōzaemon (Niwa Nagahide), Hori Kyūtarō, Hasegawa Take, and Suganoya Kuemon to prepare a feast for Lord Tokugawa Ieyasu. A chamber of the Kōunji Palace was where Lord Ieyasu, Anayama Baisetsu, Ishikawa Hōki, Sakai Saemon no Jō, and their house elders were served a meal. Lord Nobunaga himself placed the trays before his guests, a gracious act indeed, and their reverence for him was out of the ordinary.

(The Chronicle of Lord Nobunaga, page 465-466)

Someone posted a clip featuring Nobunaga from the Naotora Taiga.

The context of the scene was the famous story where Mitsuhide blundered when in charge of a banquet to welcome Ieyasu. After that, apparently in the drama Nobunaga decided to then personally serve Ieyasu’s meal himself. Naturally Ieyasu and his vassals becomes mortified by it.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yasuke, as described in the book by Jean Crasset

Transcript:

So soon as Easter Holy Days were over, Father Valignan took his way towards Meaco, to wait on Nobunanga, and thank him for his favour and Protection to the Christians and the Fathers that Preach'd in his States. He brought with him from the Indies a certain Black. As soon as he enter'd the Town, all the People crouded to see him. Father Organtin presented him to Nobunaga, who was much surprised, and more unwilling to believe it his natural colour. He imagin'd they had Painted him in this manner, which obliged the Moor to strip himself half naked, before he was convinced of the truth. He gave the Father a very favourable Audience, and appointed the Visiter (Valignano) to meet him such a day.

The Crasset text appears to use a letter from Frois as the basis for this narrative.

Incidentally, I was not able to confirm the origin of the story where Nobunaga had Yasuke washed to confirm that he wasn't painted. It's a narrative that is floating around, but in what I did have access to, I don't seem to see anything of that sort. The above story only says Yasuke took off his clothes, but no washing was mentioned. Shinchoukouki only said he was strong as 10 men, and attracted a crowd.

Here are some of the original Portuguese texts about Yasuke:

April 14, 1581 letter from Luis Frois (source for the above text)

October 8, 1581 letter from Lorenzo Mesia

November 5, 1582 report from Luis Frois

I cannot read Portuguese. I was only somewhat able to confirm the contents with Google translate, narrowed down to just the Yasuke part. I have not able to check what else was written in there, because typing them takes a while to do.

#yasuke#jean crasset#european#european account#alessandro valignano#japanese history#sengoku#sengoku period#sengoku era#jesuit

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nobunaga rages in Kyoto over rulership of Ise Province

More interesting narrative from Crasset's book.

But some days after an unhappy and tragical Accident turned all this Joy into Mourning and Tears. For Nobunanga, who never play'd but a sure game, seeing all the Nobility of Japan Assembled together at Meaco, resolved to make use of this occasion, and gave out, that he intended: to invest one of his Children with the Kingdom of Ixe. The Lords of that Country, who had a kindness for their Prince, did not at all relish his Proposals as was expected, but seem'd quite averse to them, which put him into so outragious a passion, that he took Thirty of them and Beheaded them, without regard to farther Process, He also put to Death seven considerable Lords in the Kingdom of Xamaro. And tas'd their Houses on suspicion that they had not favour'd his Interest. These severities made him dreaded by all, and seeing he was pleased to favour the Chriſtians, none durst give the least disturbance for fear of incurring his displeasure.

(page 358 of Book 1)

This took place "some days after" the grand parade that Nobunaga put on in Kyoto in 1581. The Europeans were invited to the event, and they had a church in Kyoto besides, so if this incident happened in public they might have been direct eyewitnesses of it.

The Shinchoukouki naturally made no mention of such a thing happening, but that book is indeed one that is rather heavily "censored".

This is a curious incident, because Japanese accounting gave me the impression that Nobukatsu and Nobutaka already had taken over the headship of their respective adoptive families some years prior, and thus already share leadership of the province of Ise as of 1581.

Not to mention that, as I quoted in a previous post a section of the book, Nobutaka was introduced as "King of Ixe". That part comes before this part. This doesn't seem to make very much sense.

The first possibility was that this might have been narrated second hand, and the person writing this account somehow got the names in this incident muddled. Perhaps Nobunaga was actually talking about a completely different province.

I'm not certain what else was there to dispute about in Ise after the raid on the Kitabatake family, which had happened in 1576. After Nobukatsu assumed the headship of the family, Nobunaga ordered the purge of many of the Kitabatake family members for reasons that I'm not entirely clear of (there are many tales I saw, but no proper source). After that, by all accounts Ise was already under the control of Nobunaga's sons (Nobutaka supposedly took over the Kanbe family even earlier).

The other possibility is that what Nobunaga wanted was to restore the Oda surname to his sons, since at the time they were still using the names of their adoptive families, Kanbe and Kitabatake. Surnames are considered more important than bloodline, so the clans might have previously begrudgingly accepted Nobunaga's sons taking over the headship, because the names were at least still preserved. However, if they return to their Oda surname, the Kanbe and Kitabatake names would be lost, and the vassals would naturally object to it.

It still doesn't explain why Nobutaka was already "the King of Ise" when he was introduced, but maybe these are based on multiple texts that were not in proper chronological order.

What province was "Xamaro" supposed to be is a bit hard to parse, but my guess is that it's Yamato, based on how a Portuguese map had labelled Totomi as "Ioromi" (this makes me very much curious of how spoken Japanese sounds like circa the Sengoku). Yamato Province borders Ise, so it would be understandable that they might have also put forward objections and get caught in the fire.

#ODA NOBUKATSU#ODA NOBUTAKA#ODA FAMILY#ODA CLAN#SAMURAI#SENGOKU#SENGOKU ERA#SENGOKU JIDAI#SENGOKU PERIOD#WARRING STATES#WARRING STATES PERIOD#WARRING STATES ERA#JAPANESE HISTORY#JAPAN#oda nobunaga#jean crasset

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rotating volley technique possibly exist in Sengoku Japan

Previously in my Nagashino post, I mentioned that the popular story of the rotating volley tactic is considered dubious. The main reason for it is that the source of it is completely unknown. At some point it became a just-so story in the Edo era, and was affirmed as fact by the Meiji government, clearly without properly checking its veracity.

Even Oze Hoan’s Shinchouki text (this is not Ota Gyuuichi’s Shinchoukouki), which is already considered dubious in the first place, only recorded that the Oda forces had 3000 guns. It also did not describe a rotating volley tactic.

However, even if this artillery tactic is not explicitly used in the Nagashino battle, there is proof that the Japanese troops are aware of and seemingly well-trained trained in this tactic at least as of the late Sengoku. It was known to have been used in Hideyoshi’s Korean war, as recounted by the people of Ming and Joseon:

In 1593, for example, Ming General Song Yingchang (宋應唱, 1536-1606) noted that the Japanese employed the musketry volley technique, writing that he feared the Japanese would “break into squads and shoot alternately against us (分番休迭之法).” In 1595, Korean King Sŏnjo shared the same apprehension that “the Japanese [would] divide themselves into three groups and shoot alternately by moving forward and backward (若分三運, 次次放砲)?”

From "Big Heads, Bird Guns and Gunpowder Bellicosity: Revolutionizing the Chosŏn Military in Seventeenth Century Korea", a thesis by Kang Hyeok Hweon.

Maybe there were records of this method employed in domestic battle that the researchers just haven’t discovered yet. For now it’s still unclear where and when the Japanese troops learned of this. Just that they seem well trained enough in it during the battles mentioned above.

It’s noteworthy, however, that this rotating volley tactic was already a very well-known method of warfare in China as early as 750s AD in the Tang dynasty. First, it was used by archery and crossbow units. Then, they evolved the technique to be used with guns. Below is a description of a battle in the year 1414:

“The commander-in-chief (都督) Zhu Chong led Lü Guang and others directly to the fore, where they assaulted the enemy by firing firearms and guns continuously and in succession. Countless enemies were killed.”

From “The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World” by Tonio Andrade.

Especially noteworthy is that the enemy’s army described in this passage are also mounted troops. It’s not impossible that the Japanese somehow learned of the above literature from Ming, and then put it in practice, though without proof we cannot assume too much.

King Seonjo’s description, specifically, sounds like the kind of rotating volley usually described in the Nagashino stories. This brings to mind how many times I’ve seen cases of Edo period stories inserting anachronistic objects or settings into narratives of the past, so it could be how this legend was born. Perhaps the Edo storytellers took the volley technique that wasn’t known or used until later, and just assigned it to Nagashino for dramatic flair.

#artillery#Firearms#resource#research#japanese history#imjin war#bunroku keicho war#samurai#sengoku#Sengoku Era#Sengoku period#Warring states#Warring States Period#Warring States Era

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mori Ran Naritoshi, not “Ranmaru”

I originally mentioned this in a little addendum in an older post about Nobutada, but I want to add some more details just about this matter.

Nobunaga’s young vassal, famously known in media as “Mori Ranmaru”, may not actually be named that at all in reality. "Ranmaru” was the name that was written down in later-date records and compilation of tales that may or may not be accurate. In contemporary Sengoku documents, as well as his own correspondence, his name was written as just “Ran” 乱 or “Ran’houshi/Ranboushi” 乱法師.

It’s unclear if the above is his childhood name or his alias.

Some websites, both in english and Japanese, sometimes claim his adult name having been “Nagasada”長定. This is apparently based on the 18th century document Kansei Chouchuu Shokafu 寛政重修諸家譜, a compilation of the family records made by the shogunate in the Kansei era (1789-1801).

However, the Shinchoukouki records his name as “Naritoshi” 成利. In the temple Kongouji in Osaka and a museum in Tateyama, there were also artefacts of Ran’s own handwriting, where he signed his own name as “Mori Ran Naritoshi”.

Sadly I was only able to find personally-made transcripts of these, and not the actual pictures. Some museums prohibit photography, and not all of them are willing to showcase photos of their exhibits online.

There was an ukiyo-e where Ranmaru’s name was written as “Nagayasu”, but this is historically irrelevant. This is part of the very same series of heroic ukiyo-e prints that wrote Nobunaga’s name as “Oota Harunaga”, and so it’s only reasonable to assume that the names written on it are not necessarily correct.

For some reason some of the names in this ukiyo-e series were “censored” while others were not (e.g Mitsunari became Kishida Mitsunari, but Hideyoshi was still “Toyotomi Hideyoshi”), so this is not a reliable account of names.

There’s also the trope of “Ran” being written as 蘭 (”orchid”) rather than 乱, as also seen in the ukiyo-e above. However, these are all done in later-date documents. As mentioned earlier, the lad wrote his own name as 乱. Some people have suggested that even in the early Edo period, his character was already romanticised as a “beautiful, but gallant youth”. This kanji was then used to further “beautify” his image.

There is a claim of proof of this, which I haven’t yet been able to verify. An article once said that a certain historical account (I believe it was one of the many Taikouki variations) had Ran’s name written with 乱, but a copy of the same text written decades later had replaced the name with 蘭. Both copies were discovered, and the experts found that except for that one name, everything else were the same.

(”Ranmaru” is still used in the blog tags for the sake of ease for searching and/or newcomers)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

I happened to see in the news some new cast announced for Dousuru Ieyasu.

Satou Ryuuta as Hideyoshi's brother Hidenaga (top left), Oonishi Riku as Ran(maru) (top right), Tokushige Satoshi as Ikeda Tsuneoki (lower left), and Hamano Kenta as Nobunaga's son Nobukatsu (lower right)

To adhere with historical records, the article said Ranmaru will go by just "Mori Ran", and not "Ranmaru". Not only did the Shinchoukouki records this, but he apparently wrote his own letter signatures in that way. However, for the costuming, the style they went with is "old school". The curling hair tie and heavy kataginu is a typical look of the more kabuki-inspired look from black and white Shouwa era movies.

I'd thought it was curious that Ikeda was wearing that Buddhist monk's "drape" (kesa 袈裟), but it's actually how he was drawn in his portrait.

Nobukatsu's casting and styling is also interesting. His appearance is somewhat reminiscent of Sometani's Nobunaga from Kirin ga Kuru, and it looks almost like they made him wear an outfit that resembles the classic Kanou Soushuu Nobunaga portrait. Maybe it's meant to emphasise a sort of "Nobukatsu tries to follow his father's footsteps" plotline during Komaki-Nagakute. He was known to be using a Tenka Fubu-esque seal in that time period, after all (see this post).

#dousuru ieyasu#live action series#live action#nhk drama#nhk taiga drama#taiga drama#ikeda tsuneoki#hashiba hidenaga#toyotomi hidenaga#oda nobukatsu#mori ran#mori ran naritoshi#mori ranmaru

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Nobunao”, a possible alias of Nobukatsu’s

I found this on someone’s blog post, and they’re also relaying something that’s written in a book they said they read, so this is third-hand news. I try to avoid doing this usually, unless the relevant materials are actually shown in the original post, or if I can see the things for myself. However, I just find this fascinating, so I’m going to share this here anyway.

There is a certain letter in the “Komonjo Kagami” 古文書鑑 collection that was kept by the Sanada family that was signed “Nobunao” 信直. The identity of this person is unclear, but this letter was cited in other records as an “Oda Nobunao” letter.

The letter says: “Saburouzaemon dispatched to discuss the issue of Tamaru Castle’s destruction, and do it quickly without delay”

As the addressee is identified as Ogawa Nagayasu 小川長保, who served Nobunaga’s second son Nobukatsu, researcher Ogawa Yuu speculated that this Nobunao is an as of yet unknown alias that Nobukatsu had used. This letter could possibly related to the situation where Tamaru Castle caught on fire.

Another document, also signed by a Nobunao who is presumably the same person, was stored in Kakurinji. The letter, dated to be from sometime around the fifth month of Tenshou 6 (approximately June of 1578), is consistent with the Shinchoukouki accounting of the presence of Oda forces in the area at the time. Among the many officers listed, Nobukatsu is included.

While there actually is an “Oda Nobunao” whose identity is clearly known, he had died in 1574, and couldn’t possibly write this letter.

One thing to take note of specifically is that the signature of this mysterious “Nobunao” looks very much like the signature used by Nobunaga and his son. You can see the loop with the little stripes.

Even if this “Nobunao” fellow is not Nobukatsu, it’s still highly likely that he’s one of Nobunaga’s close relatives, as this signature is unique to Nobunaga (and his sons “inherited” it from him, something that seems to be customary for sons and heirs to do in that time).

Also, I’m no handwriting analyst so I don’t know if this means anything, but as a personal observation of mine: The イ stroke from “Nobu” 信 in Nobunao’s signature is missing the angled stroke, making it look like a し. This is also something that Nobunaga and his sons do, though I cannot yet verify if this is unique to them in particular.

Certainly it’s possible that other people also have the same handwriting habit, and I just have not seen it yet (Shingen and Kenshin don’t seem to do this, for example)

I say this is fascinating because Nobukatsu’s got a rather long trail of name changes. He was purportedly originally named “Kitabatake Tomotoyo” upon his adulthood ceremony, as he was then the adopted son and heir of the Kitabatake family. Then, supposedly his name became “Nobuoki” after completely taking over the Kitabatake family. At some point before Honnouji happened, his name became the “Nobukatsu” that we know today.

If he really did change his name to “Nobunao”, then it should have occurred between Nobuoki and Nobukatsu.

People at the time don’t usually change their name for no reason, and for him to change his name this many times (especially compared to his brothers) is a bit weird. The change from Tomotoyo to Nobuoki makes sense. As the Kitabatake family is essentially vanquished then, it makes sense for him to discard the hereditary Kitabatake “Tomo” name and use the Oda’s “Nobu” name instead (even though at the time he still uses the Kitabatake surname). The other changes doesn’t seem to be tied to any significant event.

#conspiracy theory#oda nobukatsu#artifacts#artifact#letter#document#handwriting#oda family#oda clan#sengoku#Sengoku Era#Sengoku period

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Nobutada was in Kyoto during Honnouji incident: Solved!

Part 2 of my musing from last time.

I can’t believe I found the answer so quickly! Internet rabbit holes has its uses, sometimes.

I found a transcript of Nobutada’s letter addressed to Ranmaru, dated the 27th of the 5th month, which says thus:

尚々、家康者、明日大坂・堺被���下候、 中国表近々可被出御馬由候条、我々堺見物之儀、先致遠慮候、 一両日中ニ御上洛之旨候間、是ニ相待申候、此旨早々被得御諚、 可被申越、委曲様躰使申含候条、口上可申候、謹言 五月廿七日 信忠(花押)

森乱殿

I’ve heard that [my father] is personally heading to Chuugoku, and as such I will refrain from heading to Sakai. Since he’s expected to arrive within the next day or two, I shall wait for him [here in Kyoto]. In order to inform you this as quickly as possible, by leave, I have given all the details of this matter to the messenger and he will relay them to you.

PS: Ieyasu and his company will be headed to Osaka and Sakai tomorrow.

27th of the 5th Month Nobutada (signature)

Mori Ran-dono

As it turns out, Nobutada was actually about to head to Sakai, likely to accompany Ieyasu on his trip there. However, hearing that Nobunaga was on his way, he decided to instead attend to his father in Kyoto.

Another blog also mentioned a letter from Sen no Rikyuu, supposedly describing this same cancelled trip in dismay. Rikyuu was apparently supposed to be Nobutada’s host in Sakai. I can’t find a transcript of this letter, unfortunately.

The Shinchoukouki did also mention Ieyasu in the same passage that described Nobutada was heading to Kyoto, but oddly enough did not specify that they’re headed to the same place. It made it sound like they just happen to drop by for a rest stop at the same person’s house en route to their respective destinations.

Also, side note. There has been something of a dispute about how “Ranmaru” is written. Some texts say the Ran is 乱, which means warfare. Others say it’s 蘭, which means orchids. This letter, as well as letters written by the man Ran himself, uses the 乱 kanji, so we can assume that that is the correct spelling. I imagine the “orchid” one was a later-date invention because of the “pretty boy Ranmaru” trope that became popular in the Edo period.

He also wrote his own formal name as being 成利 Naritoshi, not Nagasada as some accounts claim.

Besides that, if other letter artefacts to be believed, “Ran” is apparently short for “Ran’houshi” 乱法師. Though, this doesn’t necessarily mean “Ranmaru” is a false/wrongly-recorded name. It might just be that “Ranmaru” was the childhood name, and after his adulthood ceremony, his alias/”middle name” is “Ran’houshi”.

#Mori Ranmaru#mori ran#mori ran naritoshi#mori naritoshi#oda nobutada#Tokugawa Ieyasu#Honnoji#honnoji incident#Honnouji#honnouji incident#Honno-ji#samurai#japanese history#sengoku#Sengoku Era#Sengoku period

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wonder if the Shinchoukouki rough draft, the one that’s still called Azuchi Diary, has more details on Nene’s visit. Because documentation from the Okazaki bureau said that it had more text in it but got censored out in the “final product

Like... the infamous letter where Nobu calls Hide a bald rat... Some theories said this had something to do with Nobu granting Hide to adopt one of his sons, and because Hide himself is out in battle, Nobu talked with the wife instead.

Issues of children and adoption would present an appropriate context for talks of marital woes to come up, because otherwise why else would they even have a chat about Hide being a womaniser with many concubines??? It just kind of feels weird, talking about “my husband is being a floozy” to... his boss...

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nobutada in Kyoto... What’s he doing there?

This is not so much an article so much as it is a question I’m trying to find answers for, because it just dawned on me that something is rather mysterious: What was Nobutada doing in Kyoto when Honnouji happened?

Most people probably had assumed that he was there as part of the Oda contingent headed to Chuugoku to convene with Hideyoshi and fight the Mouri there. However, that does not seem to be the case.

I was rereading the Shinchoukouki to compare information in relation to a previous post that I made, but in the narration, it described that Nobutada was already headed towards Kyoto even before Hideyoshi’s report and request for reinforcement arrived.

He had made a stop at Azuchi, and while the text didn’t detail when he proceeded to Kyoto from there, it’s only reasonable to assume that he just made 1 or 2 days’ stop there. The report from Hideyoshi and the commanders’ assignments likely happened after he already moved onwards to Kyoto. He was not among the list of officers given orders by Nobunaga to head out to Chuugoku either.

Besides, if he were meant to prepare for battle himself, I imagine that he would have made the preparation to gather more soldiers, and would not have been outnumbered once the invasion hit. There was about 2 weeks between him heading to Kyoto and Honnouji happening. If he wanted to, it seemed like he could’ve bulked up his standing army a little bit more.

So, if his presence in Kyoto was incidental, then what was he actually doing in there?

Luis Frois wrote in his account that Nobutada went to Kyoto to worship the Atago Gongen after the Oda’s victory against the Takeda, but the Takeda battle was about 2 months prior to Honnouji.

Frois’s description of the worship ceremony being “early in the year” implies that Nobutada performed this almost immediately after the all the battle logistics are done with. Whatever his business in Kyoto that got him tangled up in the Honnouji Incident was, it doesn’t seem like it has anything to do with that ceremony.

In relation to the “not star-crossed lovers” post, there’s some conspiracy theories online that said he came there to receive Matsuhime as his wife, but this was actually just the plot of the “Onna Fuurin Kazan” drama that I mentioned in the post, so that is absurd. There’s no reason why Matsuhime, who was taking refuge in a temple in the Eastward provinces, to have to come all the way to Kyoto in the West to marry Nobutada. If anything, it would make more sense for Nobutada to have invited her straight to Gifu, which would have been a much closer place to meet.

#oda nobutada#Honnoji#Honnouji#honnoji incident#Honno-ji#honnouji incident#japanese history#sengoku#samurai

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I wanted visuals of how close Kyoto is to Azuchi because it’s actually not that far away. The Shinchoukouki said the vassals escaping Honnouji made it back to Azuchi in just a few hours, though it didn’t say how they got there. Maybe they ran out of Kyoto on foot, and got a horse midway through (once they’re far enough away).

I probably don’t need to do this and just use Google Map. Kyoto and Azuchi are more or less still exactly in the same place as they are in the Sengoku. Google Map says approximately 45-50 Km, and 10 hours of walking. Might be faster if they ran like hell. Would definitely be faster on horseback.

5 notes

·

View notes