#shaku does commentary

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Now tell me the gay montriputro story please🙃🙃

KSKSJDJDHD NOW IT'S TIME FOR MY ANOTHER FAVOURITE TALE MUAHAHAHAHAHA

Ok so this story is actually so cute I wanted to retell it in my own ways someday... (nvm im too lazy to get going with anything) and this story's characters also had no names so I thought “hmm since I'm already planning to retell this why not give them brand new names....”

You might have (or might not have) seen me making some random gay doodlings and showing them to @igotadigbickandureadthatwrong [the uponkor ones lol...] and sometimes I sent one or two pictures from the og book to @randomx123 too ig..?

So this story has 4 main characters... (Well that's what I consider but you can consider 3...) And for the love of god non of them had a fucking name (and a fucking side character had a name 💀🤌) That's why the names I allotted to them are...

Dun dun dun...

Im revealing them in the narration lol...

Tagging people whom I want to share this crazy story with @randomx123 @jeahreading @krishna-priyatama @no-idea-where-i-am-lost @foreignink @igotadigbickandureadthatwrong @prettykittytanjiro @ishaaron-ishaaron-me @stxrrynxghts @desigurlie @crystraniqelle @priestessofuniverse @dwarpharini @shubhadeep385 @hydestudixs @dreamer-in-sleep @aru-loves-krishnaxarjuna @livingtheparadoxlife @groovycynicalcheesecake @wulfricnavy (im sorry im adding you late 😭 but consider this the return gift for Depth of Despair)

Trigger warnings: bitchass people, unfortunately those bitchass people don't die well in this story... sigh, infanticide, homoerotic friendship, divine intervention, snakes, snake dying, snake coming out of nose, turning into stone, talking birds and swearings

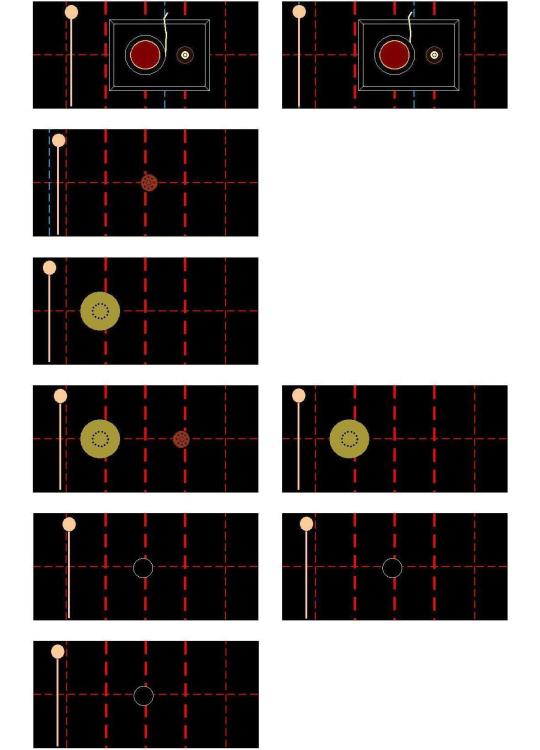

So in the starting of the story we are told about this rajkumar Upendro (yes I named him) and his verryyy verryyy verryyyy close “friend” the montriputro Shonkor 🗿 (I named him too yeahhh)

They are such good “friends” they can't even spend a day without eachother. They grew up together and do everything together eat sleep roaming around. They are literally the do dil ek jaan kinda “friends”. It's a hot topic how close these two are with eachother...

Their “friendship” is so deep Shonkor sometimes falls asleep in Upendro's room and nobody gives a flying fuck about it... Not Even the king. 💀🤌

(Me interviewing the maids of the palace*

Maids: ohh then they fell asleep together, such good friends I mean...

Me: 💀💀🗿✨ yup... Very good friends... 💀✨)

.....

So whatever back to actually plot

One day Upendro is like

Upendro: yk... I feel like going on some adventures...

Upendro: roaming around the kingdoms... Seeing new things..

Upendro: just you and me...

Shonkor: ...

Shonkor: ok

So yeah, they decided they'd go do Dora the explorer shit in the wild and went away. Just the two of them on their horses and didn't take any men or soldiers with them. 💀

And they roamed around here and there in different kingdoms and places, like those discovery channel dudes.

.....

One day after travelling for long enough they are in a forest and it's getting late. And they come across a BEAUTIFUL lake and it got really clear water like glass.

So our boyfriends besties decides “yeah let's spend the night near this lake on that banyan tree nearby”

And they tie their horses at the bottom and then get some water from the lake for hath mukh dhona and drinking and climbs the tree to sleep on it (I have no idea what they were planning to do on those branches or if it's even possible to sleep on branches 💀🤌)

.......

Now after sometimes a lot of light literally blinds them, like there's too much brightness like my mom's phone screen all over the forest and they are both like o.O trying to figure out where the light came from

And their eyes fall at the lake and they see a bigass snake coming out of it, and it has a BIG mani on it's head (hehehehehehd nag mani lessgoo) which is the source of all the blinding light.

So they see the snake crawling out of the pond and into the forest and under the tree. Snake bbg puts the nagmani down from it's head and below the tree (idk how that even happened considering it has no hands or anything 💀💀)

And then the snake eats up those two pookie horses (MY SHYALAAAAAA NO MY SHYALAAAA 😭😭) and goes away deeper into the forest 🗿🗿 blud didn't even try to climb the tree bruhh

So now Upendro and Shonkor are like 💀💀 because one wtf is that giantass snake and two their horses are gone 😭😭 (I just really love horses ok!!)

So Shonkor my ultimate gadha climbs down the tree to look at the mani and he just fucking covers that stone with the horse saddle for some weird reasons idfk 💀🤌 and then climbs back next to his boifren

......

So snake dude?dudette? idk comes back after sometime and when it couldn't find it's mani it just makes all those growling sounds like crying and all. Then it fucking dies. 💀 In dispression. 💀 Because it lost it's stone. 💀 (Ykw mood 🗿 I'd die too if I lost my favourite stone)

So now Shonkor and Upendro stays awake the entire night on the tree scared shitless 🌝 because yeah obviously you don't wanna end up in a anaconda's stomach even if you know it's ded. Like take no chances my boys.

So next morning early in the dawn they come down from the tree and Shonkor picks up the mani from those hiddings to wash it in the lake (why's he always doing the labour Upendro you hypocrite bitch)

And as soon as the mani touches the water it again starts to glowwwwwww ( read it in the you make me glow tune) and they notices a literal PALACE under the lake 💀💀

And they are like “GURL DAMN WHAT”

......

So these gayass bitches decides they wanna know what's in tha palace (like no thoughts of self preservation or safety or anything... 💀🤌 dumbasses)

And they go under the lake and yeah surprise surprise they can breath under water because of the mani 🗿

So whatever... they get under water in that palace and it's really gorgeous and big and a lot of stuff are there like trees and fruits they never heard of, flowers with sweet smells, and ofcourse lots of gemstone and stuff and as expected NO ONE fucking no one's in that palace 💀🤌

So they get inside the palace (bro that's trespassing where's your poribar's shikkha??) And starts to search all the rooms like some local chor because bruhh 💀

......

Then they suddenly hear some very feminine crying sounds coming from one of the rooms, and ofcourse they are like o.O and go to see what's wrong and comes across the room where the sound is coming from

Inside they see a gorgeous maiden sitting on the GOLDEN bed and sobbing like her world ended (which yeah it did)

And she hears to footsteps and looks up to see those two randomass dude standing there like🧍And she's like

Bbg cutie: who are you all? 😭

Bbg cutie: why are you here? 😭

Bbg cutie: go away or the snek will eat you 😭

Bbg cutie: it already ate my mom dad siblings and everyone in this palace 😭

Bbg cutie: only I'm alive now (because of unknown reasons) 😭

Bbg cutie: so go away before you become the 3 course 5 star meal for the snake... 😭😭

So Shonkor is like

Shonkor: girl dw that snek is ded, we killed it :D (where dude? It died from grief stop lying idiot)

Shonkor: see see the mani from its head :D

And he shows her the mani (also Upendro you bitch why tf are you just standing and doing nothing you kamchor lyadkhor harami)

[Ohhh btw I named my bbg Kumudini just because 🗿🗿🗿]

So now

Kumudini: umm ok... But who tf ARE you??

Shonkor: ummm I'm Shonkor... You? (Well in the og tale he just says he's montriputro but since I gave him a name he's saying his name ok)

Kumudini: I'm the princess of this place Kumudini 🥹🤌

Kumudini: will you two go away from here 🥺 (goshhh she's so pookie I love her soo much ahhhhh)

Shonkor: no no! We're here to stay ofcourse :D

Kumudini: omgg yayyy welcome you all will be as comfortable as possible here :D

[I love how Upendro is just standing there like 🧍 while these two chat like he's such a dumb and introverted gadha... I love him so much lmao]

......

So they start to stay in that patal palace (that's how that place is described ok it's said to be patal... cool ig?)

And ig in those days Upendro and Kumudini have their Kuch Kuch Hota Hai moments cuz Shonkor then one days tells her Upendro wants to marry her 💀🤌

(Lmao imagine the conversation that went between our cookie Shonkor and his adopted introvert Upendro...

Upendro: bhai 🌝

Shonkor:

Upendro: setting karwa de 🌝

Shonkor:

Upendro: plj 🌝

Shonkor:

Shonkor: ok 💀

Upendro: yaayy ilysm 🥹)

And unsurprisingly Kumudini agrees to marry him cuz ofcourse duhh they are in looveee~ 💀

So they get married in that place (idk how they got a purohit tho... Ig allrounder Shonkor became the purohit... Or they simply married without a purohit which is also not at all wrong)

......

Now after somedays Upendro starts to feel homesick because they have been away from there kingdom for SO LONG

So Upendro tells Shonkor that they should go back home but Shonkor is like

Shonkor: yaaa you're right. But idt you two should go like this....

Upendro: wot? woi?

Shonkor: cuz you both are newly married 🗿

He basically tells them both to stay at the patal palace and enjoy their honeymoon while he goes back to their kingdom to get the king daddy to come and fetch them, since Upendro's the prince and he just got married so that would be appropriate.

And so Upendro and Kumudini agrees, while Shonkor tells them bye bye and sets off for home. (Sighh... Things you do for your homoerotic friendship huh)

......

So now Kumudini and Upendro are spending their days well and good in that patal palace.

BUT one day Kumudini was getting really bored in the afternoon while Upendro was giving a mosher moto ghum (this bitch also likes bhat ghum my brother in maa Durga ufff 🫂🥹🗿✨)

And she looks at the nagmani kept close by and wonders how the upside world looks like cuz she had NEVER been there in her entire life (you need a guide for your first trip bbg don't do it alone pls)

So she decides “yeah nothing bad will happen I'll just go and come back before hubby wakes up...” and takes the mani to get out of that lake and wonder around the forest :p 💀✨

And she goes around admiring the things and all yk typical snow white behaviour, and it makes her really excited and happy because she's seeing all those for the first time in her life.

Then she comes back to the patal palace before Upendro could wake up and acts all normal and happy 🌝 telling him nothing (because more gele ke dekhche what's safety what's precautions???)

......

So this shit continues for some days, everyday she goes up and wonders like Dora the explorer during the afternoon and then comes back before Upendro can wake up from his moron ghum and she pretends everything is normal. 🗿🗿

BUT how can they live in peace right? Some crazy shit is bound to happen...

So one day as she was sitting by the lake and just playing with the water like the pookie cookie she is, that kingdom's bitchass rajkumar (the kingdom in whose area that forest falls) was out hunting with some of his equally bitchass friends and they come across the lake and banyan tree. (There's a buri mohila near the tree too, keep that in mind, it will be important to the plot later)

The rajkumar (I'm not naming him I'd just call him bitchass rajkumar) sees Kumudini only once and Kumudini get's scared and just jumps back in the lake and goes back to the palace.

And now dude is like shocked pikachu face because tf happened and he falls back down unconscious because of how GORGEOUS Kumudini is.... 💀🗿 (i mean I would too 🗿)

.....

This side Kumudini got REALLY scared so she stopped going out of the lake for some days and just spends her days in patal palace like normal, not wanting to get caught roaming by some randomass men (see everyone is scared of unknown men)

And on the other hand, over there bitchass rajkumar's sakha gang are like “yoo dude wtf happened??” and they worry for him but all dude could say is “where did she go?? where did she go??” 💀💀💀

So they are like “beta pagla hoye gache” and they take him back to the palace to his father the king. And in a few days bro becomes absolutely bedridden and mad only ever saying “where did she go?? where did she go” 💀🤌

.....

Now king dude is like “wtf gotta save my baby boy” and he does what any typical king does when no raj vaidya works... And makes the announcement that whoever can cure the rajkumar and decode who's “she” that person will get half the kingdom and the hand in marriage with his daughter the rajkumari 🗿💀✨

And now nobody fucking knows what to do because who IS “she”??? So nobody is able to save rajkumar and the king dude is getting frustrated...

THAT'S WHEN the buri mohila from before randomly appears claiming she knows how to cure the rajkumar and who “she” really is...

But ofc nobody believes her not even the king (cuz she got a rastar pagol type er chhele who's called Fokir and everyone thinks she's also pagol like her son) 💀💀💀

But she insists and says she will do it she'd just need a lake side view hut and a bunch of soldiers to help her. And if she succeeds her son must get that half kingdom and the princess' (king dude's daughter not Kumudini don't confuse) hand in marriage... (I first thought she was gonna ask to get married to the princess herself 💀🤌)

So king dude is like yeah what's there to lose? And agrees to her thinking the buri mohila can't do shit.

......

Then she gets the lake view hut and soldiers and starts to stay there starring at the lake all day.

Now this side after many days Kumudini finally gets the courage to go back outside and gets out of the lake to sit near it. 💀✨

NOW as soon as she's out in the wild sitting and playing around with the water, that old hag approaches her... And pretends to be friendly telling her not to be scared and anything and dumb dumb blorbo Kumudini agrees and tells her who she is saying she's the patal puri rajkonna and stuff showing her the nagmani.

The buri mohila pretends to be curious and asks to see the mani taking it in her hand and as soon as Kumudini gives it to her like a bokach*** she tells the hidden soldiers to come out and basically kidnap Kumudini 💀💀💀 (that's why you should trust NO ONE in an unknown place)

.....

They kidnap her and take her back to the palace while she's crying and begging them to let her go (too much traumatizing shit goes on in this story trust me)

And the buri is like “dw girl you'll be fine here the rajkumar just wants to see you”

So in the palace they call the half mad depressed bitchass rajkumar who's still murmuring “where did she go?? where did she go??” and as soon as he sees Kumudini he's like

Bitchass rajkumar: THAT'S HER THAT'S HER THAT'S THE MAIDEN I SAW BACK THEN

Kumudini: just lemme go plssss 😭😭🙏

Bitchass rajkumar not even listening to her: you're so gorgeous ahhh I wanna marry you 🥹

Kumudini, trying to save herself: ummm umm I- I can't marry for six months I'm doing a vrat 😭

Bitchass rajkumar: okk bbg I can wait for you for eternity what's six months to that 😩✨✋

(💀💀 that's legit a line from the book ok... 💀 And as much as I like the flirting romantic line he just said he's still a big long smelly piece of shit so I hate him)

......

And now back to patal palace, Upendro wakes up and is in deep depression cuz Kumudini is missing and even the mani that enables them all to get out and inside of lake is missing so he can't even go search for her.

He's literally in pieces, crying himself to madness in that lonely palace (ok yeah bro really loves his wife sigh... I just love him so much)

So now six months are going by and Kumudini is still kept hostage in that bitchass palace.

And this side Shonkor had returned to the lake side after months with those delegation party men and is waiting for Upendro and Kumudini to come out of the lake on the given date and time. But for obvious reasons non of them does that but who's gonna tell that to my baby boy sigh... 💀🤌

So he and the men he brought wait for them for some days camping in the lake side 🗿✨

......

But then one day he sees some randomass man of that kingdom going by and he asks

Shonkor: yoo dude why is there so much noice in this kingdom?? Is some festival going on?? (Cuz dude's been hearing shanai er awaj for the past days)

Dude: donchu know?? The rajkumar of this kingdom is getting married to the beautiful patal puri rajkonna...

Shonkor: .....

Shonkor: ohhh

(YEAH THOSE FUCKERS ARE FORCING MY GIRL TO GET MARRIED CUZ SIX MONTHS ARE ABOUT TO BE OVER)

And now Shonkor is like.... Damn something sus is going on and decides he'd go and investigate further cuz wtf?!?!

.....

So he goes to the city and just stays as a guest to a randomass brahmin's family to get more info

Shonkor: umm so... I heard the rajkumar is getting married to some patal puri rajkonna... Where did he find her??? 💀

Brahmin dude: ohhh yeah thats a really long story so atleast a year ago.... *tells the entire tale of bitchass rajkumar becoming depressed and muttering “where did she go??” and then buri mohila bringing Kumudini and etc etc*

Shonkor, internally fs: 💀💀💀💀 FUCK- GOTTA SAVE MAH GURL-

Shonkor: ohh umm achha... Ummm

Shonkor: so... Uhhh did the king get his daughter married to that buri mohila's son Fokir as promised...??

Brahmin dude: lmao nahhh that dude is a rastar pagol ahh person idt the king would keep his promise LOL

Shonkor: ahhh damn... How does he looks anyway??

Bhola bhala brahmin dude: hmmmm tbh he looks kinda like you... Just a little more mad and dirty and he roams around in torn clothes and all

Shonkor: ohhhh achha achha well thank you ʘ‿ʘ

......

So next day Shonkor is like dress up bitches ✨🗿💀 and find some chhera fata clothes and becomes Fokir 🗿 cuz ofc he's THE FRIEND IN NEED IS A FRIEND INDEED personified (he's my shona mona chader kona frrr ahhh)

And then he goes to that psycho bitchass buri's house during the evening cuz well buri must have cataract at that age and won't be able to tell properly if it's her son or some randomass dude 💀

So he goes infront of the buri's house and starts to 🕺🕺🕺✨ .... Yes... Dance 🗿🔥

Psycho buri: yoo Fokir you home??

Disguised Shonkor: ..hmm 💀

Psycho buri, rambling on: where tf do you stay you dumbass

Psycho buri: do you even have any idea I fixed your marriage with the rajkonna???

Psycho buri: you'll marry her right??

Disguised Shonkor: ..hmm 💀💀

And then she drags him inside not even knowing that it's not her son because well... As I said it's evening and she got cataract fs

Psycho buri: do you even know how I fixed your marriage??

Disguised Shonkor: 💀💀 ....no...

Pyscho buri: ok so listen...

And she PROUDLY tells him how she kidnapped an innocent maiden just like that and practically held her hostage so that people can force her in a marriage without her consent 🤡🤡 and then shows him that mani which she kept with her all this time

Shonkor internally: BITCH I WANNA BEAT YOU UP YOU HORRIBLE FUCKING WOMAN- 🥰🔪⚡🔥👹💀✨ (this is legit in the book ok)

Shonkor internally: gotta somehow.. anyhow get that mani out of your hands asap and save my bestie and return back to my boyfriend...

Psycho buri: ykww.... Fokir... You keep this mani with yourself... AND DON'T LOSE IT!

Disguised Shonkor: o.O ok... 💀

Psycho buri: now lessgo to the palace and meet that patal puri rajkonna

Disguised Shonkor: ...hmm

......

So she dresses him up in somewhat bhalo jama kapor and takes him to the palace, where the king dude does some khatir jotno 💀🤌 cuz yeah Fokir is gonna be his ghor jamai afterall... (like bro how tf did this bitch of a man even agreed to get his daughter married to a rastar pagol typa guy?? 😭 I hate him so much)

So whatever now Disguised Shonkor looks here and there and when the buri asks what's wrong. He does some ishara to that buri to say “where is Kumudini” and she goes “ohh yeah lets go see her” and takes him the chambers she's kept locked in.

They go by the gaurds who look at them like 🤨 but still lets them go cuz yeah one's a madman another's a buri mohila what can they do...

.....

Inside the chamber Kumudini bbg is still crying because ofcourse she would be

Psycho buri: ahh girll why do you keep crying?? You will literally marry the rajkumar he'd be such a nice husband...

Shonkor, internally: BITCH HOW'D YOU EVEN KNOW WHY MY PHUL JAISI LADKI IS CRYING YOU'RE THE REASON FOR THIS 🥰👹👺🔥🔪💀

So after sometimes buri mohila was like “lesgo home now” but disguised Shonkor refused to go anywhere and just shaked his head.

Buri was like “yeah if this bitch said no then I can not convince him, I'll just let him stay and hangout with Kumudini then...”

So she left and Fokir looking Shonkor stayed in the room with Kumudini who's still depressed and crying and what not.

.......

So late at night when everyone has already retired to sleep and all

Disguised Shonkor: yoo bestie can you recognise me???

Kumudini: wha- *looking closely* OHHH

then she just breaks down in more tears out of relief ig...

Kumudini: TAKE ME OUT OF HERE BY TONIGHT PLS PLS PLS BESTIE PLS 😭🙏

Shonkor, covering her mouth: shhh don't say that

Shonkor: dw da'lin I've found you now and I will get you out I promise 🥹🤌

Kumudini: okk bestie 🥹🥹

......

Now Disguised Shonkor keeps roaming around the place and doing his ✨🕺dance🕺✨ in front of the gaurd who suspect nothing cause he's a madman and he goes in and out of the palace quite a few time to gain their trust.

THEN when he's sure they will let him do anything he wants, he gets to Kumudini and tells her to dress as a man and then he takes her and they both escape from that hellhole 🗿🗿✨ (boi is so smart)

And they FINALLY get to the patal palace under the lake and see that Upendro is literally on the verge of his n'th mental breakdown.

Seeing his boyfriend and wife returning like that Upendro is like o.O And then Kumudini again starts to cry

Kumudini: I'M SORRY I WENT UP WITHOUT INFORMING AND ALL THIS HAPPENED WAHHHH 😭😭😭

Upendro: IT'S NOT YOUR FAULT THO WAHH 😭😭😭

Shonkor, awkward thirdwheeling most probably: ..... 🌝

Upendro: broooo you're my ultimate broooo come here 😭😭😭

And then they HUG 🗿✨ (and kiss ig)

.....

So now they all decide that “yeah let's get back home” (Upendro's kingdom) so they get out of that lake but to their surprise and horror all the people Shonkor brought to fetch them left lmao (like I wouldn't be waiting so long for them either) 💀💀

So they all get disappointed and starts to walk on their own like dumb bitches but obviously gets tired after quite some times so they decide they'd spend the night in that forest under a bigass tree.

......

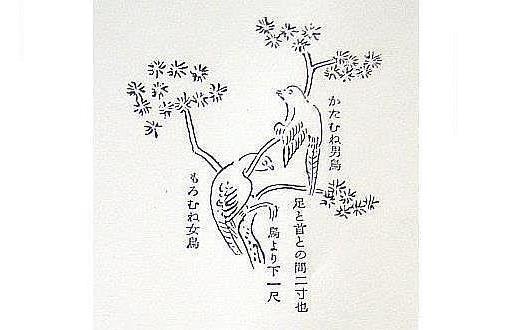

Now under the tree as Upendro and Kumudini falls asleep and Shonkor is... Idk what he's doing he's just awake for some reasons ig... He hears two birds talking (bengoma bengomi reference yooo ahhh)

Husband birdy: yo wifey yk that montriputro Shonkor did so much to save the rajkonna and rajkumar but it's of no use...

Wife birdy: wot? why??

H. birdy: yeah see so when the king would send elephants and horses to fetch his son and daughter-in-law...

H. birdy: Upendro will fall down while climbing the elephant and die

W. birdy: 💀 what if someone doesn't let him climb the elephant??

H. birdy: ohh he'll be saved then

H. birdy: but then once at the kingdom, the shingho daar of the palace will fall on his head and he'll die

W. birdy: 💀💀 what if he doesn't goes from under the gate??

H. birdy: he will be saved but...

H. birdy: when he sits to eat at the feast, the fish bones from the machher matha would get stuck in his throat and he'd die

W. birdy: 💀💀💀 ...what if he doesn't eats the machher matha??

H. birdy: ohh he'll be saved then

H. birdy: but at night when he'll be sleeping next to Kumudini

H. birdy: a snake will come out of her nose and bite him and he'll die

W. birdy: 💀💀💀💀 what if someone kills the snake before it can bite Upendro??

H. birdy: then he will be saved...

H. birdy: BUT that person can't speak these words to anyone else or they'll become a stone statue

W. birdy: 💀💀💀💀💀 YO WTF

W. birdy: then is there no way to save that person???

H. birdy: yeah there is...

H. birdy: when Kumudini will give birth to her first born child

H. birdy: that first born child must be cut in half and it's blood must be poured on the statue for that person to again become a human

W. birdy: 💀💀💀💀💀💀

.......

So yeah Shonkor listens to those birdies for the entire night 💀💀💀💀 and goes “DAMN GOTTA SAVE MY MAN-” because obviously he's the greatest “friend” ever

Now in the morning Upendro and Kumudini wakes up and they all again start their lalala journey back to the kingdom. 💀

But comes across the king's send men on their way and they are all glad and then Upendro tries to climb the elephant

And Shonkor stops him 🗿

Shonkor: bestie lemme ride the elephant once pls 🥹

Upendro: ...

Upendro: ok :)

Upendro feels a little weird that Shonkor would ask something so out of the blue but lets him take the elephant ride anyway cuz anything for his boyfriend and Shonkor literally saved his and his wife's ass just recently. 🗿🗿✨🤌

.....

They get back to the kingdom, Upendro on the horse and Shonkor on the elephant (and Kumudini was in the palki ig I forgot lol)

But now when time came to cross the shingho daar

Shonkor: bestie pls break the door na 🥺

Upendro: 💀💀💀

Upendro: ok

Upendro starts to get a little annoyed but complies with everything Shonkor is asking cuz same reasons he can't deny his boyfriend, especially after he did so much.

So now they are all happy and everything coming back home and blah blah

But the same thing happens while they were eating, Shonkor notices that his boyfriend is served with that bigass rui machher matha and he's like

Shonkor: lemme eat that machher matha bestieee 🥺

Upendro: uhhhh

Shonkor: yaayyy thanks :3

Atp Upendro had started to get irritated cuz wtf is this son of a bitch (respectfully) doing.... Just because he saved their lives doesn't mean he owns them 💀💀💀🤌 but he still keeps quiet in the public to not cause any chaos.

......

Later time comes and Shonkor is like “ok bye darling I'm going home :D” (ufsos wo kabhi ho na saka...) but Upendro is still angry and he pretty much ignores his boyfriend... glad that he's finally going home 💀🥹🤌

BUT BUT BUT my sweet child of heavens Shonkor didn't went to his home... INSTEAD he literally went to Upendro's bedroom in secret and hid under the bed 💀💀💀

💀

Yeah....

So now later Upendro and Kumudini comes to the room and it's said they fall asleep after yk talking and stuff... But we all know that's not what happened right? 🗿💀 (Don't tell me I'm the only dirty minded bitch here I swear-)

......

Once Both Upendro and Kumudini are finally asleep, Shonkor crawls out from under the bed and stands at the corner with his sword like 🧍🤺

Then by midnight he notices some thread like stuff coming out of Kumudini's nose and he gets ready as that stuff slowly becomes a poisonous snek.

As soon as the snek tries to get close to Upendro and bite him, Shonkor is like 🗡️🐍🩸☠️ and kills it. But it's blood splashes all over Kumudini 💀🤌

So this dumbass bitch is like “yeah ykw it would be rude to let her sleep with blood on her face I should maybe clean it.."

BUT while he was trying to wipe of her face, Kumudini startled woke up and started to scream, which in term woke up Upendro 💀🤌

....

AS SOON AS Upendro is awake he's angry as fuck and starts to cuss at Shonkor 💀✨

Shonkor: pls don't misunderstand me lemme explain

Upendro: omg leave it Ik how you are

Upendro: you disgusting p.o.s

Shonkor: babe listen-

Upendro: I don't wanna listen

Shonkor: bestie I did it to save YOU

Upendro: SAVE ME? Save me from what? Stop lying

Shonkor: I- I can't say that I'll turn into stone

Upendro: idfc just tell me or I won't believe you EVER

Shonkor: you won't even believe even after I told I'll turn into stone.... 🥺😭😔

Shonkor: ....ok listen then.... 😔

.....

So now Shonkor starts to narrate whatever he heard from those birdies and both Upendro and Kumudini listens to him intently

By the time he told them about the elephant incident both his legs are stone, but Upendro insisted he continues... And by the time he's done telling till the machher matha incident he's all stone till his neck

Shonkor: you still wanna listen why I was in your room??

Upendro: yeah ofcourse duh I NEED to know the entire thing...

(I mean he got a point 💀 BUT DUDE YOUR BOYFRIEND IS TURNING INTO A STONE STATUE BRUH)

Shonkor: ok then 😔

Shonkor: BUT remember if you even want to turn me back... You will need to sacrifice your first born child and drench the statue in it's blood..

Shonkor: now listen....

And he tells them the entire thing and yeah... He's a stone statue now 🗿

Upendro and Kumudini now notices the cut up snake on the floor and they are like “damn buddy was telling the truth...” 💀💀

.....

So they both keep Shonkor's statue at a corner in their room from then on...

And soon Kumudini becomes preggo and in an year gives birth to a beautiful baby boy (whom I named Mukundo btw.... :D)

And then both of them are solemnly sitting in their room as Upendro takes little baby Mukundo in his arms and raises his sword AND- yeah... I ain't saying that.... 💀

The blood splashes all over Shonkor and in an instance he's back to normal.

......

The first thing Shonkor sees as he opens his eyes is Kumudini CRYING, SOBBING, SCREAMING IN DESPAIR and Upendro trying to comfort her through his own tears 💀💀

And Shonkor is now is despair and trauma because it's all because of him their baby is dead because of him.

He picks up Mukundo in a piece of cloth and RUNS to his own home, because he remembered his WIFE was a great devotee of maa Durga and perhaps she could help him... (YES YOU PEOPLE ALL THESE WHILE THIS MAN THIS DUDE THIS FUCKER WAS FUCKING MARRIED AND I WAS SHOOK)

But as he reached his home, he didn't knew what to do, so he ties the cloth which had Mukundo in it to the banyan tree in his backyard and goes inside trying to pretend everything is normal 💀🤌 (arre amar gadha reee)

.....

His wife (I named her Jogodomba hehe) is happy that he's back after so much time and it's all going good and well. But soon she starts to notice that something's wrong with her husband (fuck of Shonkor that' my wife, my woman, the love of my life 🗿🗿)

He'd sit quietly all day lost in thoughts and look really guilty and scared and sad and everything.

Jogodomba: hey... what's wrong...

Shonkor: ....nothing....

And she tries to ask him many times for the past days but when she sees nothings working she goes to the mondir to consult maa Durga (all problem one solution maa 🗿🗿✨✨)

Jogodomba: maa maa he's so weird these days he looks so sad and idk something is definitely wrong with that dude of mine... 💀🤌

Maa Durga: hmm I see... Go ask him tonight what's wrong and tell me tomorrow

Jogodomba: okk (◕ᴗ◕✿)

.....

So FINALLY that night Shonkor at last tells bbg what's the matter as he have a emotional breakdown crying and all and Jogodomba goes to maa Durga the next day and tells everything to her 🗿

Maa Durga: ohh I see ok yeah bring the baby to me I'll revive him :D

And so Shonkor runs back to the tree and brings Mukundo and hands him over to Jogodomba who as soon as puts him near maa Durga's feet is back to being alive and well 🗿✨ (Joy Maa Durga 🙏✨🗿)

So now Shonkor runs back to the palace with Mukundo and hands him over to Kumudini and Upendro who are all SUPER GLAD to have their baby back alive and healthy

And Upendro hugs Shonkor crying saying how much of a great “friend” he is and how grateful he'd be to Shonkor for the rest of his life (I bet they kissed)

And happily even after Ig...? (Jogodomba is mine tho-)

.......

SOOO THAT'S IT. Amar kotha ti furalo note gach ti muralo....

And I'm so sorry these took sooo fucking long to post 😭🤌 I had been so stressed and busy this week trying to cope with school and shit that I got zero time to type and everything 😭😭

But here's it! The story that I wanted to retell... Hopefully... One day... 🥹🤌 But idk if that will ever happen LOL

So now coming to why I named my characters what I named them...

Shonkor and Upendro: well... They are inspired by Harihar 🗿✨ and their “we are the same we can't live without eachother we are eachother's heart” propaganda 🗿🤌 lol.... As I was once telling @igotadigbickandureadthatwrong

Kumudini: well... Kumudini means lotus so... Lotus = Kamala, hence Kumudini = Kamala/Lakshmi so Upendro's wife being her made sense to me... 💀🤌 Also because she's from patal in the story and that was also another iconic thing that matched with Lakshmi hahahaha

Jogodomba: well duhh obviously because she got that ✨special✨ connection with Maa Durga as we saw 🗿✨ and her husband is named fucking Shonkor so it only made sense right??? 🗿💅✨

(I am such a genius no?) so I got my own Shri-Hari-Har-Uma Quad now hahaha 💅✨

Also because Shonkor Jogodomba and Upendro were names that sounded bangali enough so I choose them specifically... Kumudini well.. since she's patalnivasini she is a little different then the rest ig...

Yaaa that's it LOL I hope y'all enjoyed it :D and lemme know how you liked it :))))

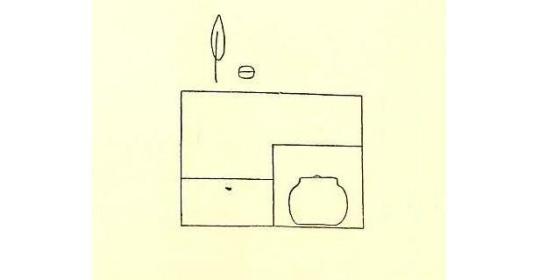

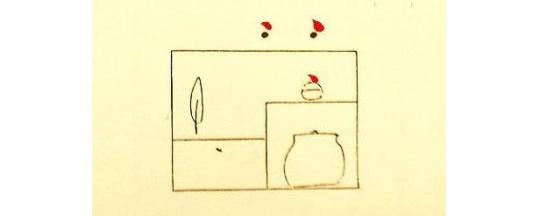

P.S. this silly doodle I made of Upendro and Shonkor one day hehe

#shaku tells stories#shaku does commentary#thakumar jhuli#rupkothar golpo#banglablr#bengali stories#bengali literature#bengali girl#bengaliblr#stories#desiblr#desi tumblr#shaku answers#uponkor#upendro x shonkor#kumudini x upendro#harihar ref#shonkor#upendro#jogodomba#kumudini#shonkor x jogodomba

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

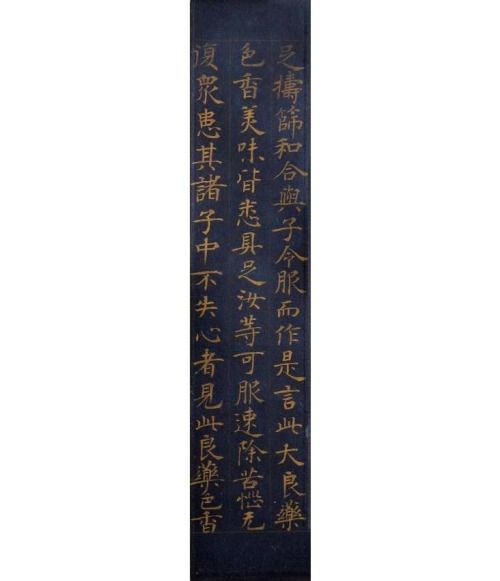

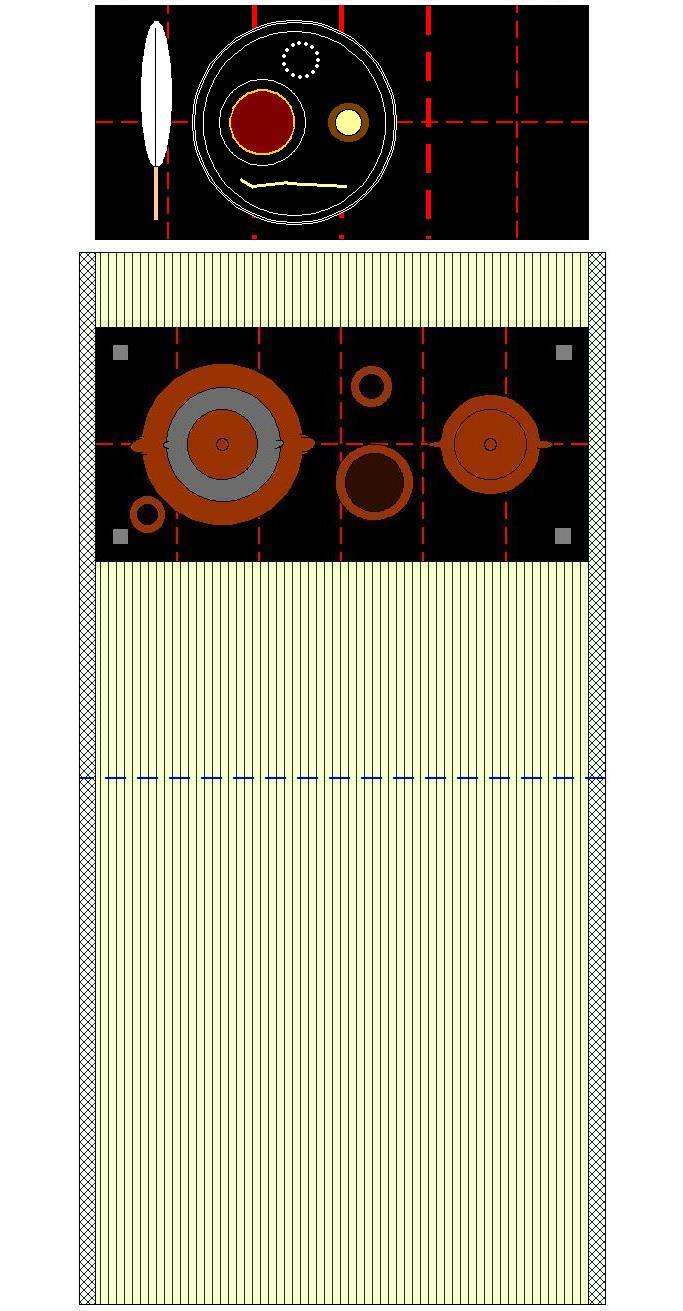

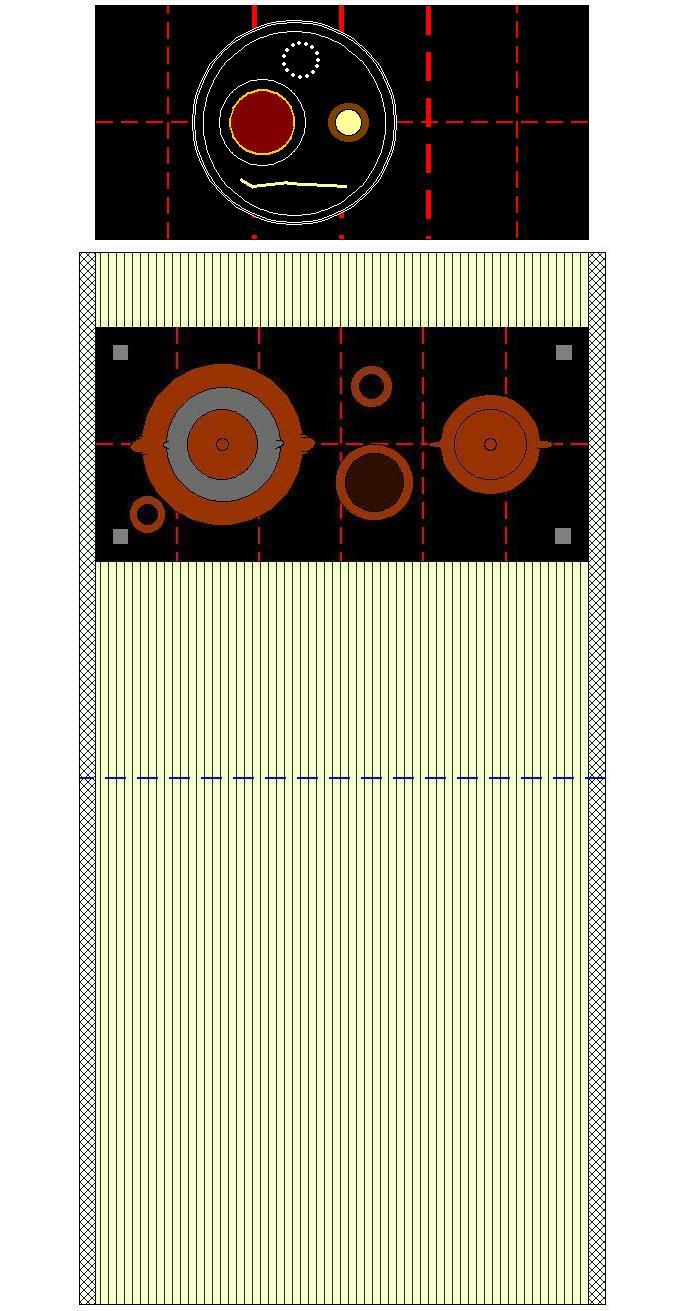

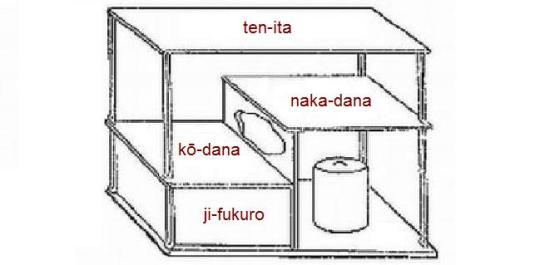

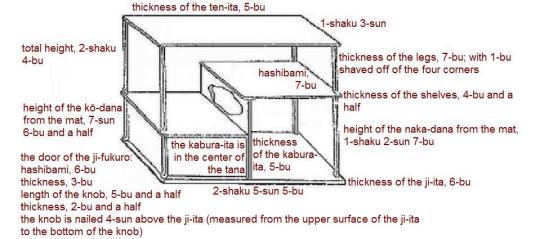

Nampō Roku, Book 6 (34.2): Rikyū's Story about the Origin of the San-shu Gokushin-temae [三種極眞手前] (Part 2).

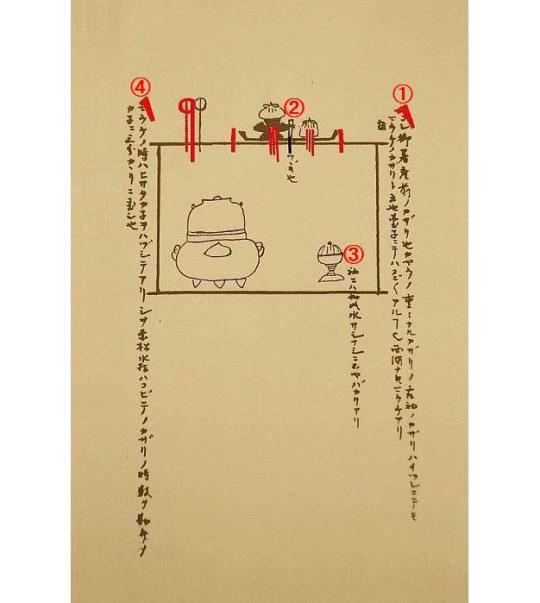

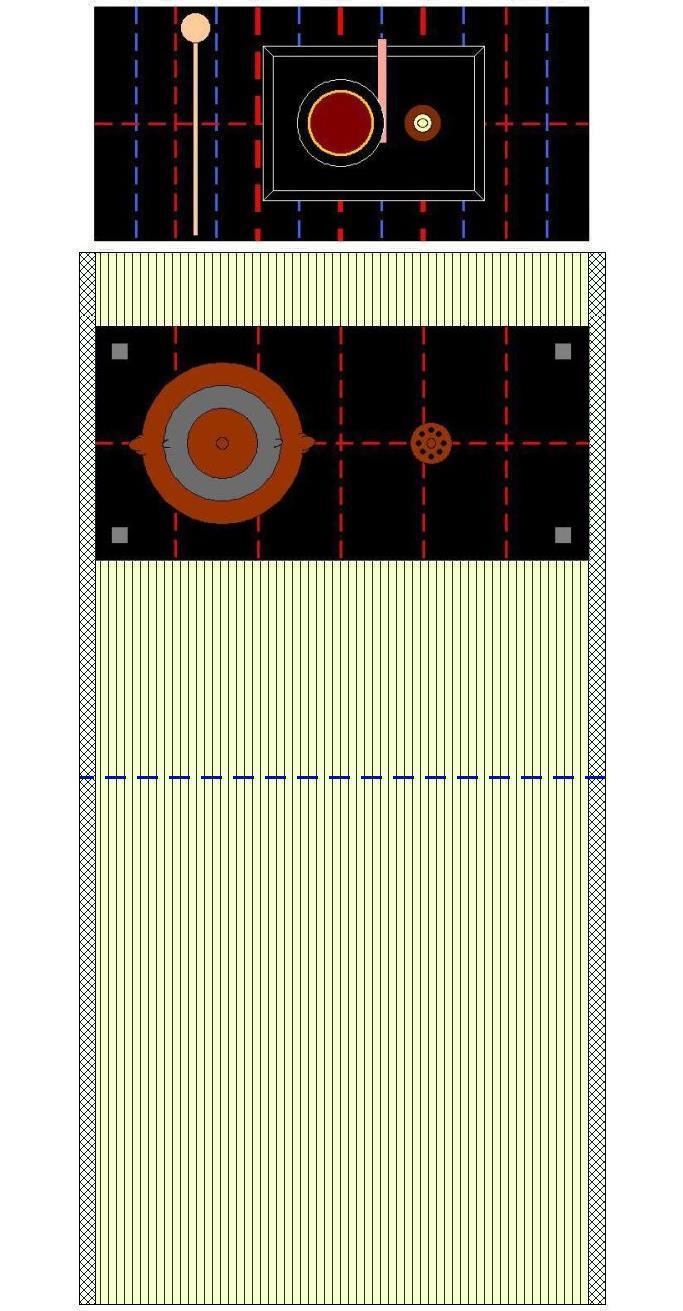

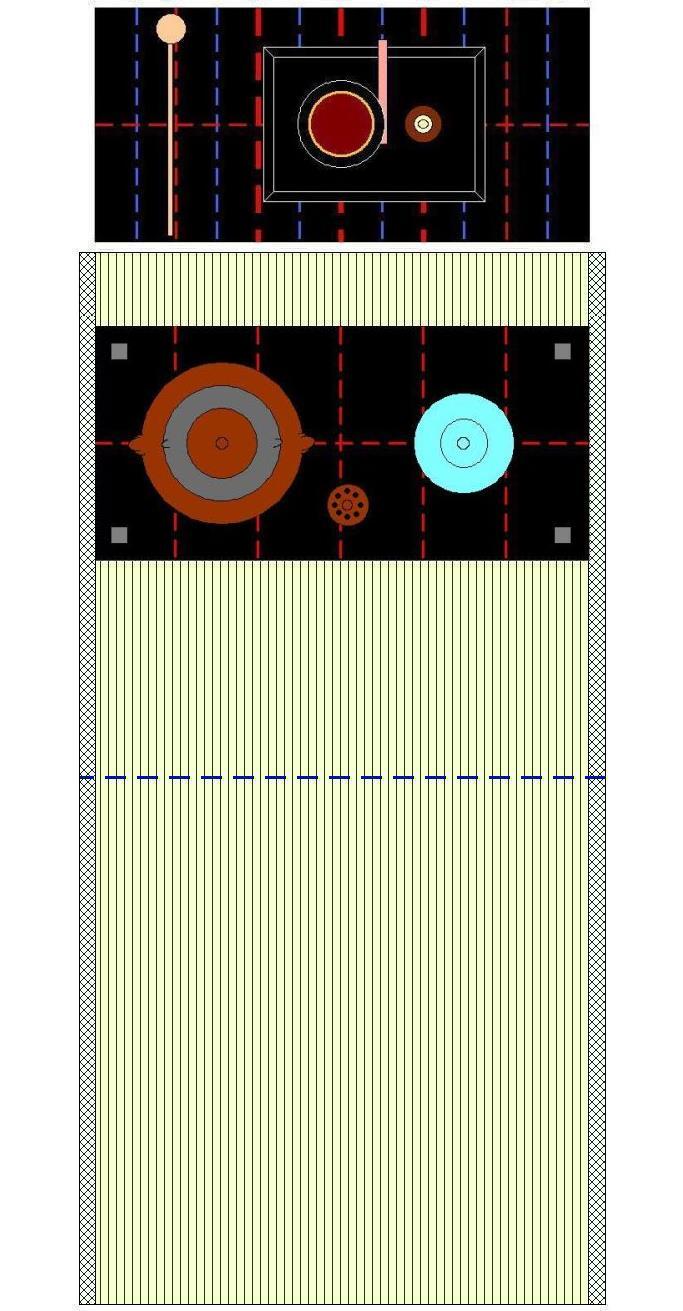

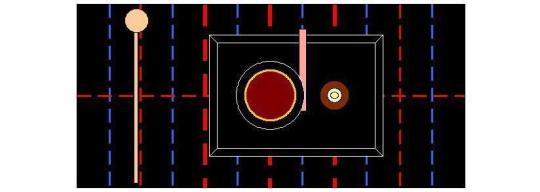

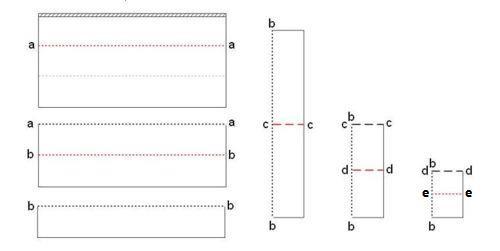

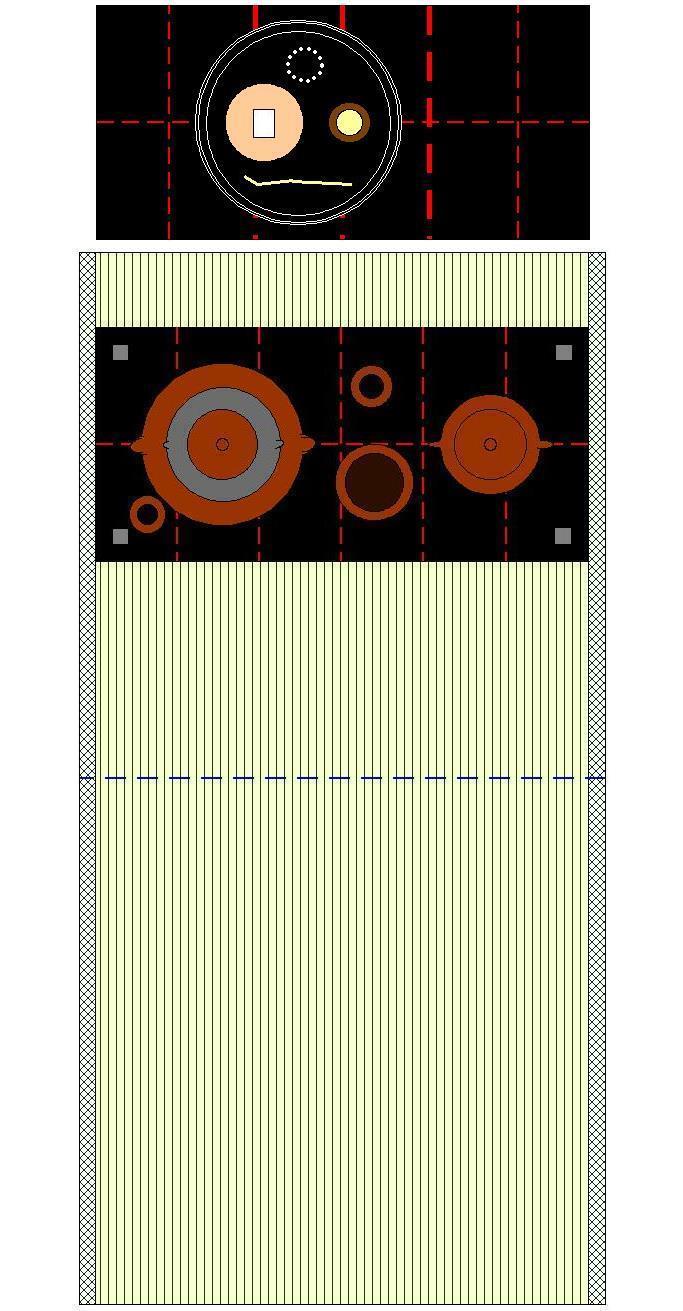

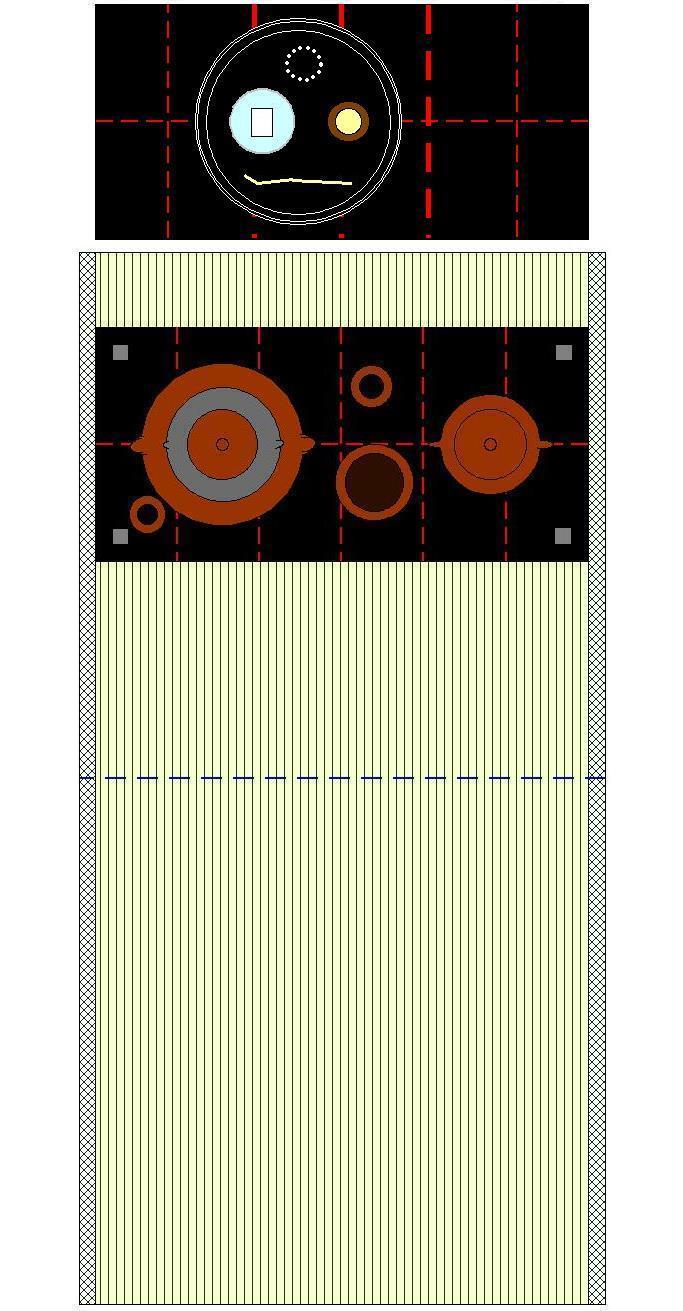

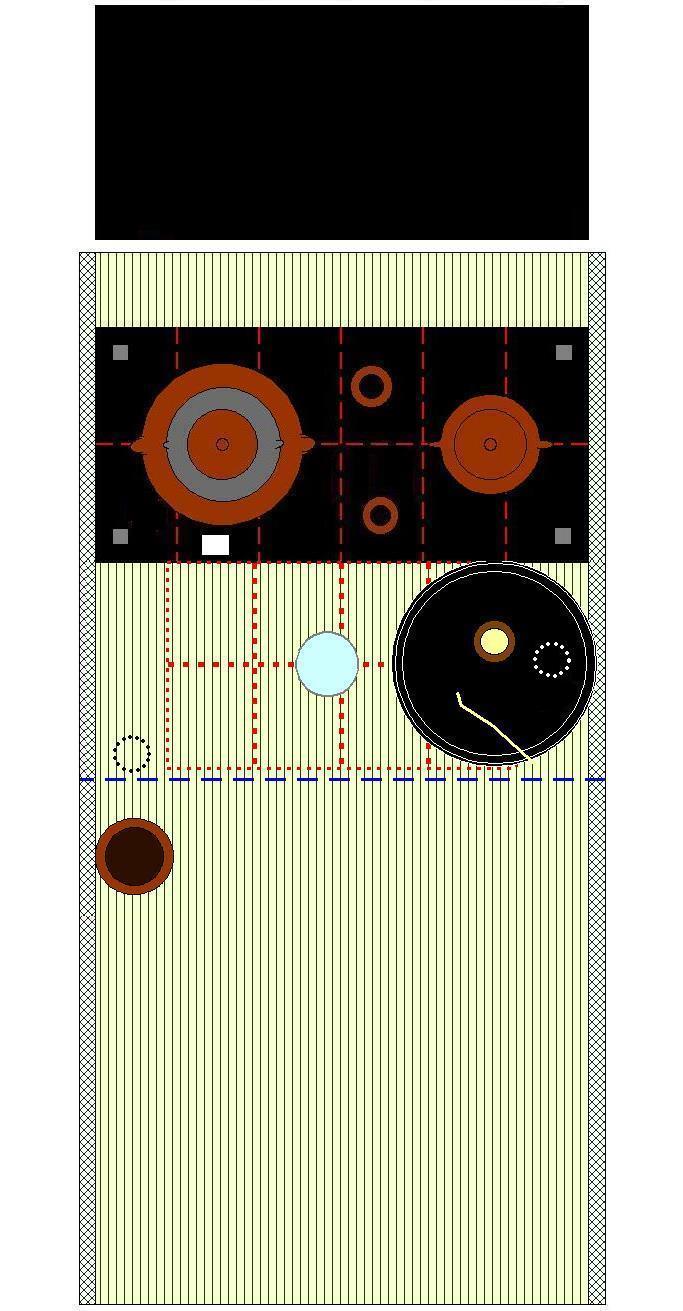

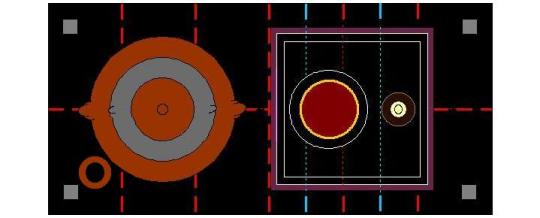

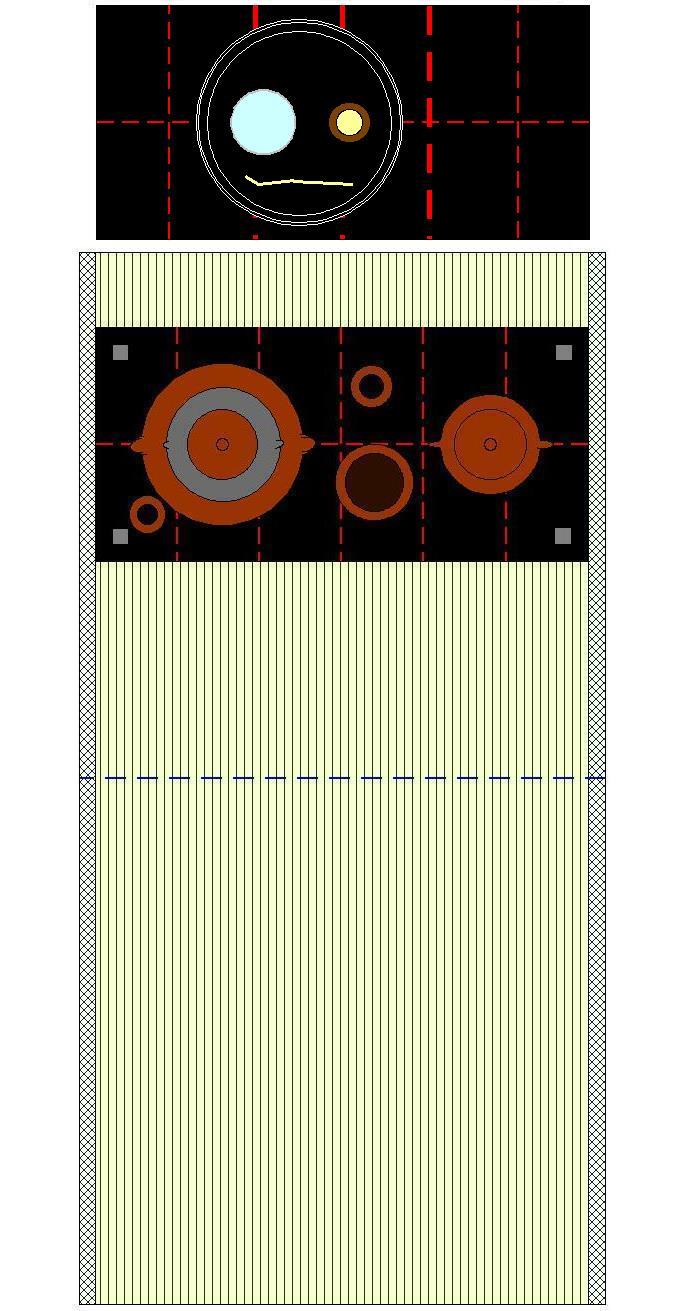

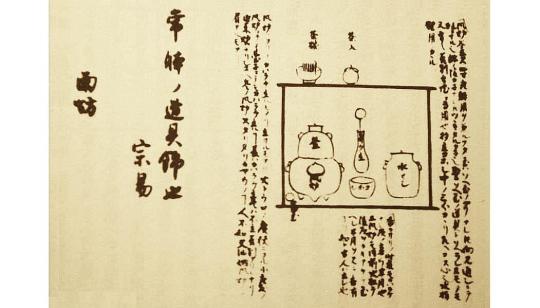

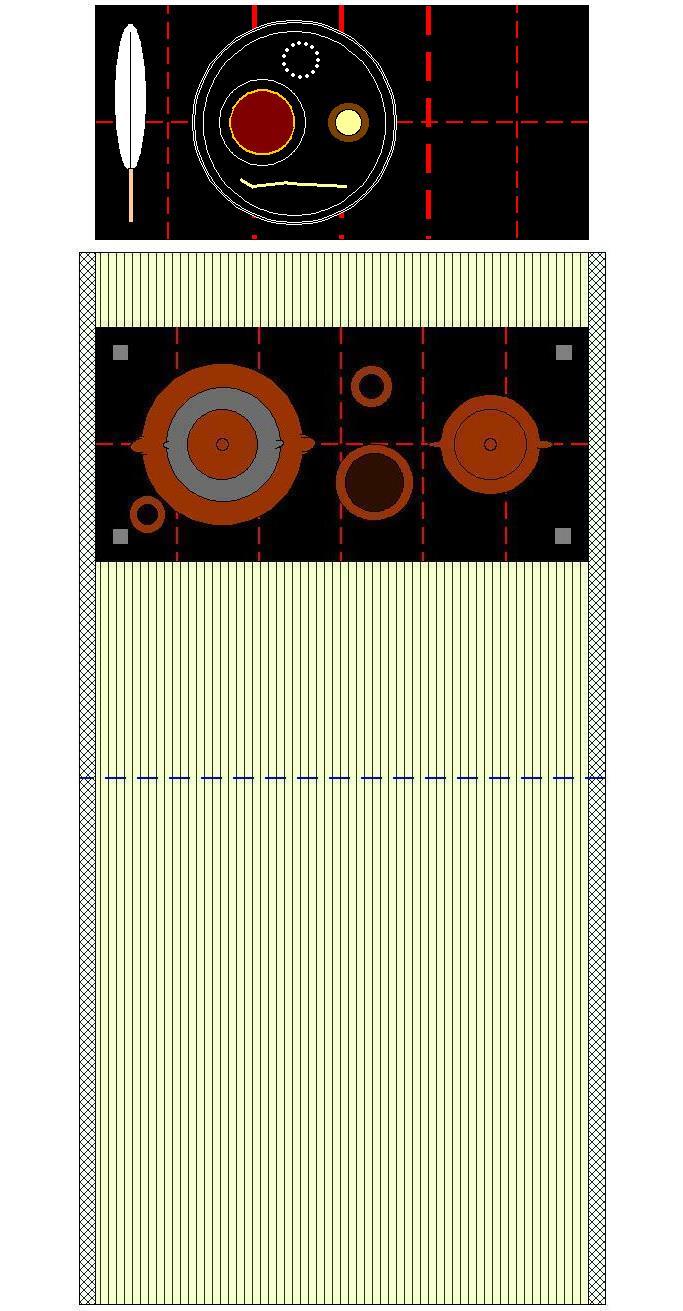

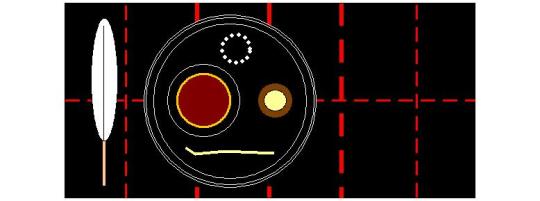

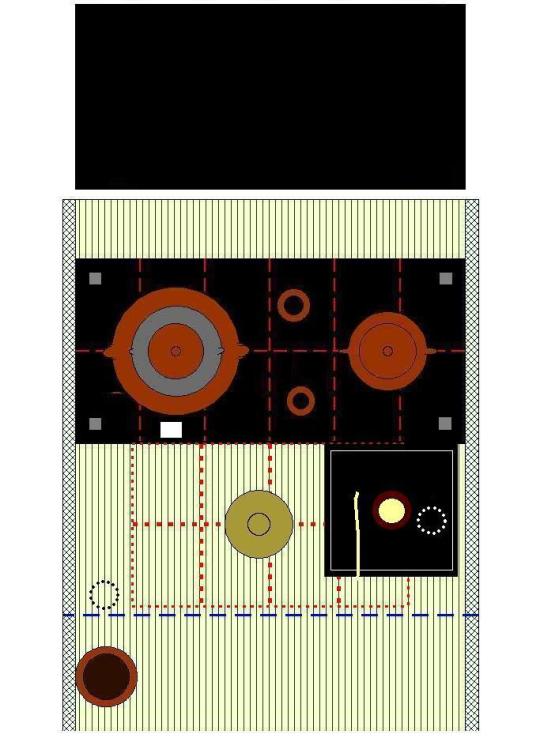

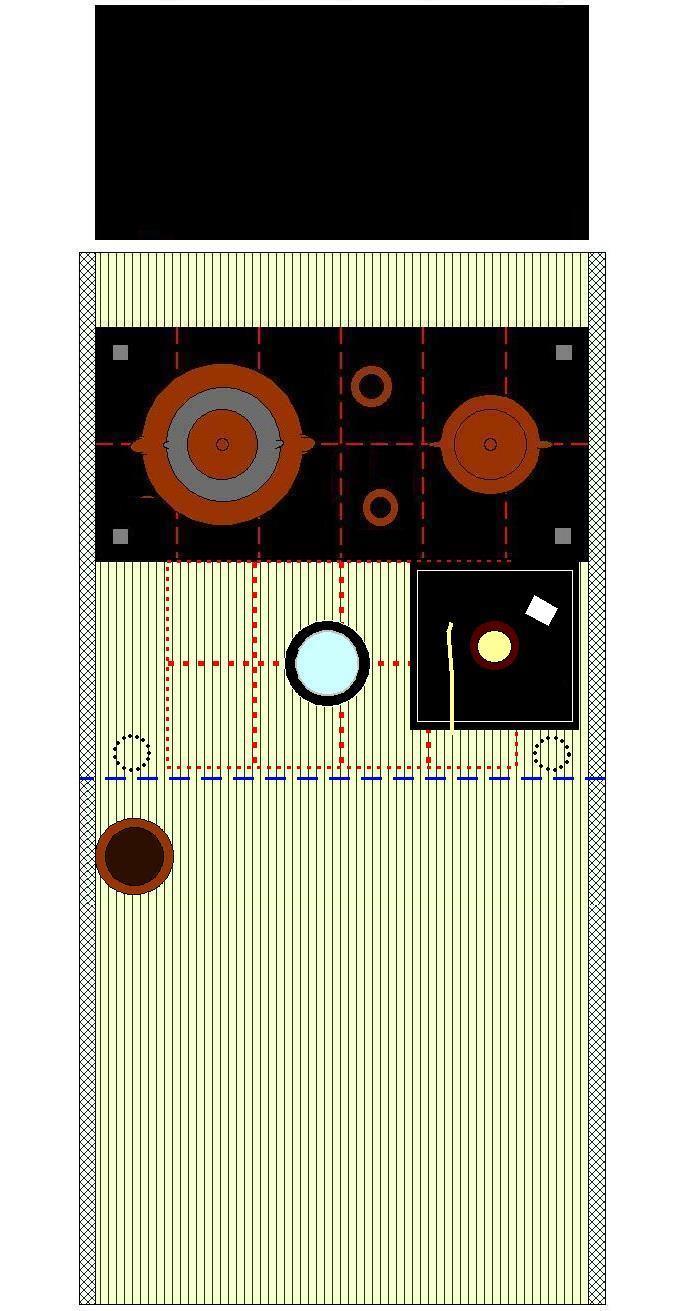

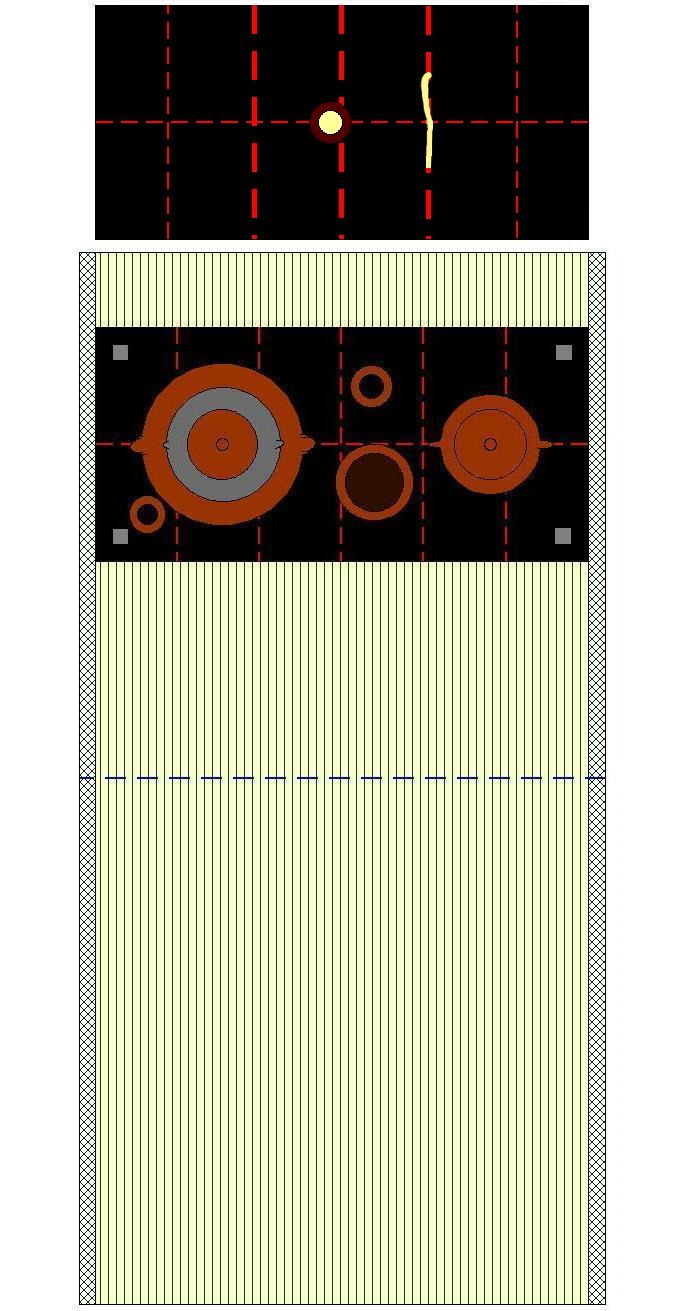

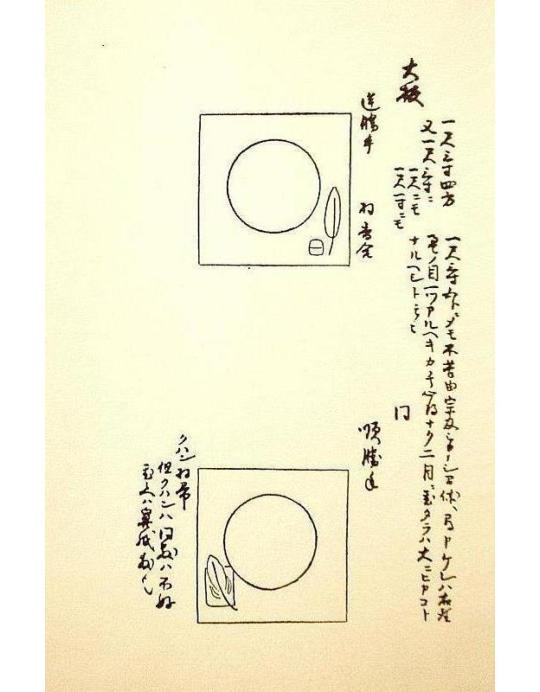

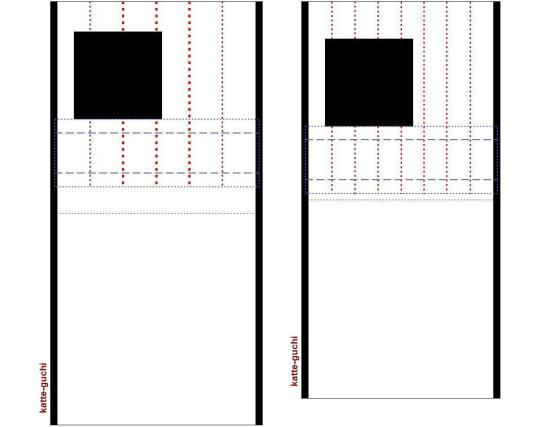

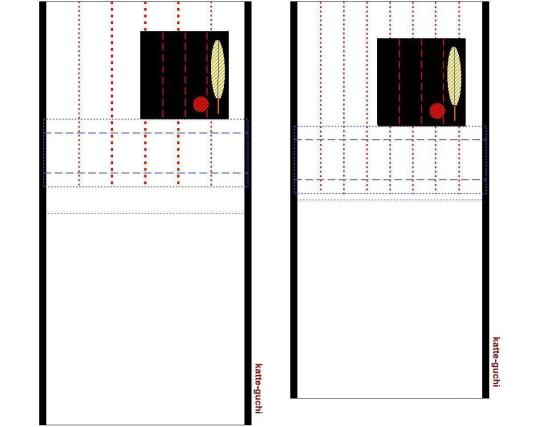

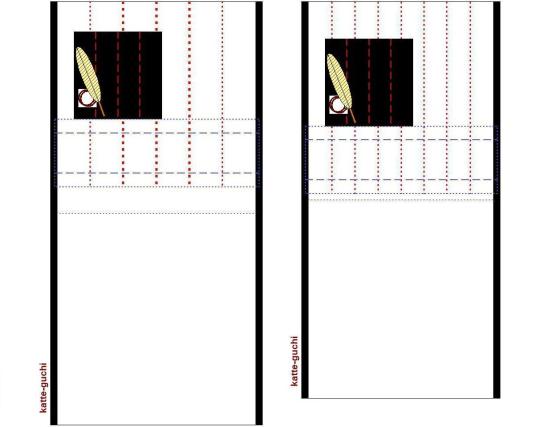

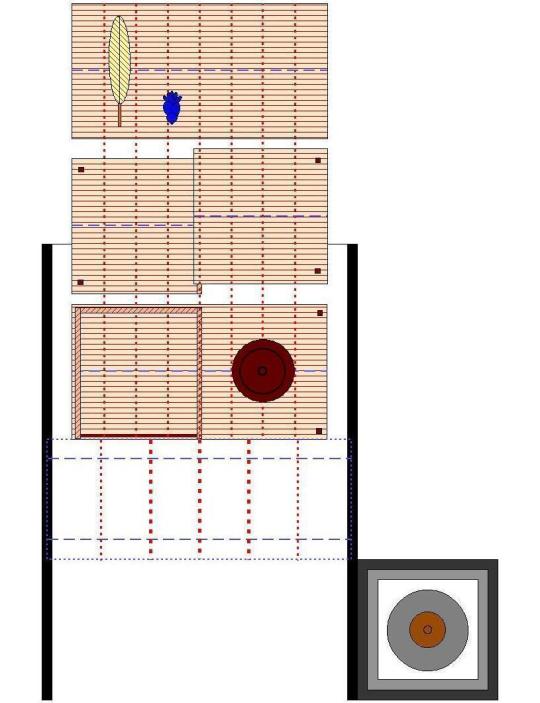

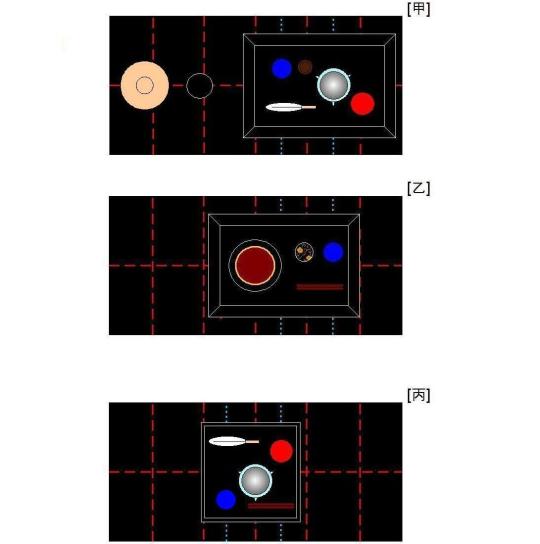

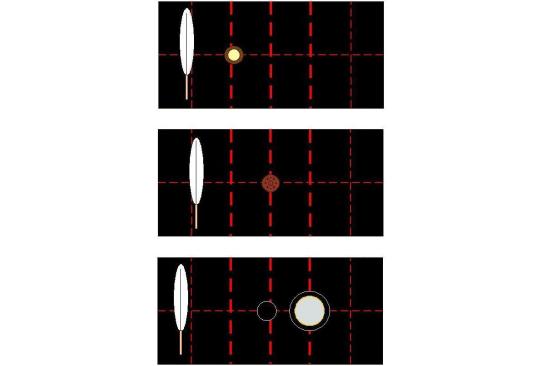

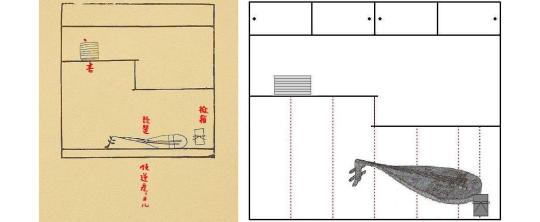

34.2) [The first sketch.]

The kaki-ire [書入]:

① This [shows] the arrangement before [the main guest] has [entered and] inspected the room¹.

The initial arrangements (in this series of arrangements that succeed each other) are said to be generated, in every case, by adding [something] to the [previous] arrangement².

This is often the case with the daisu³ -- as when the Seiko [西湖], and things of that sort, are included [in the display]⁴.

② [The objects on the tray are displayed on] successive [kane]⁵.

③ At the beginning, [the arrangement of the ji-ita] is as shown: when the mizusashi is absent, the hoya is temporarily [associated with the first yang-kane to the right of the central kane]⁶.

④ When it was added [to the ten-ita], the hishaku was displaced from its kane⁷. [But] when Akamatsu [Sadamura] brought out [the mizusashi], in order to keep the number in line with [the teachings of kane-wari], [the hishaku] was repositioned so it would overlap the kane by one-third.⁸

_________________________

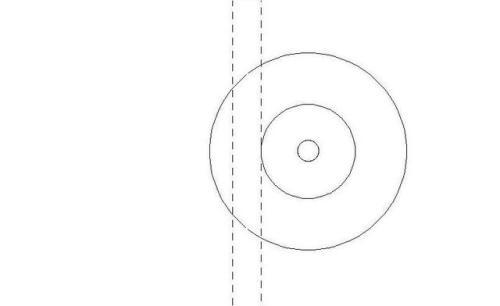

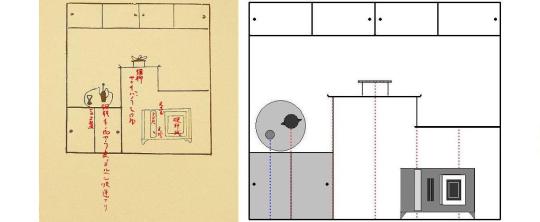

◎ The sketch is somewhat confusing, because it attempts to illustrate a number of different things all at once*. The initial arrangement is as shown below.

Here only the meibutsu pieces are arranged on the daisu:

◦ on the ten-ita, the Gassan-nagabon [月山長盆]† has been positioned so that the dai-temmoku and chaire both rest squarely on the central and first kane, respectively, with the chashaku (in its shifuku‡) placed in between so that it rests squarely on the interstitial yin-kane;

◦ on the ji-ita, are arranged the furo and kama, and the hoya only -- the hoya overlapping the first yang kane** by one-third.

According to Shibayama Fugen’s commentary, this is the way the daisu would have been arranged when the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshinori entered the room. After looking at the daisu, Yoshinori would have taken his seat, and then Akamatsu Sadamura would have begun what we might call his “pre-temae” -- readying the daisu for the actual service of tea††.

While both Shibayama Fugen, and Tanaka Senshō, discuss this sketch together with the one that follows‡‡, the length of my commentary has precluded my following their lead. Furthermore, studying the two sketches together seems to be more confusing than enlightening, thus I believe that there is something to be gained by looking at them one by one (while clarifying matters by redrawing the sketches to show precisely what is intended in each instance where they are mentioned in the kaki-ire). ___________ *Also, the actual positions of the utensils are somewhat ambiguous, perhaps deliberately so: if the person inspecting the sketch understands the details, then it will suffice; but if he does not, it becomes extremely difficult to reproduce what it shows correctly.

†The face of the Gassan-nagabon [月山長盆] was 1-shaku 2-sun by 8-sun; and it measured 1-shaku 3-sun 2-bu by 9-sun 2-bu across the rims.

Sometimes this tray is referred to as the Gassan-nagabon (or, simply, the Gassan-bon), and sometimes it is called the Tsuki-yama naga-bon (Tsuki-yama bon), alternate readings of the same kanji compound -- the latter being a “secret pronunciation” that was supposed to segregate the initiated from the ignorant. “Gassan” is the usual pronunciation of this compound.

‡The chashaku was tied in a shifuku that was shaped like a miniature cover for a sword.

This is rather different from the hood-like shifuku that some schools use during their cha-bako [茶箱] temae.

While there are several possible ways that the shifuku-clad chashaku can be placed on the tray, the most common way is that shown in the sketch (with the bowl-end of the scoop resting against the far rim of the tray).

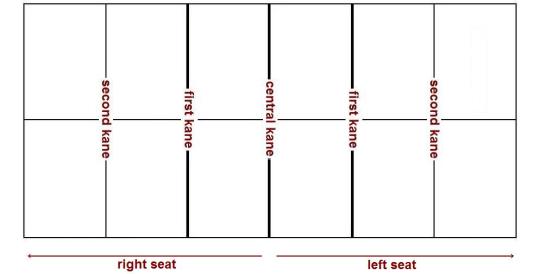

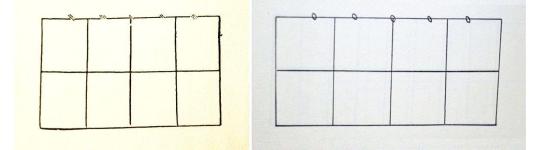

**The kane are counted outward from the center.

In other words, the yang-kane immediately to the right of the central kane is called the first kane; the right-most kane is called the second kane, as shown above. (In the Nampō Roku, the kane on the right side of the central kane are referred to as the left kane; and those on the left side of the central kane are called the right kane -- because the authors considered the utensils arranged on the daisu to be facing toward the host, a sort of reasoning that was intended to confuse the uninitiated. However, in my explanations I use the natural designation -- so left means left, and right is right.)

††It is this “pre-temae” that is being narrated here (albeit with many of the details eliminated).

‡‡Tanaka, especially, seems desirous of keeping his comments on these two sketches as sparse as possible -- probably because his school traditionally offers a special training course in this temae every year during the summer vacation season (for which the lesson fee is, frankly, beyond the reach of the ordinary student of tea).

¹Kore o-kimase mae no kazari nari [コレ御著座前ノカザリ也].

The Sadō Ko-ten Zenshū [茶道古典全集] edition of the Nampō Roku contains an error in this line. The second word should be o-miza [御看座], rather than o-kimase [御著座] (which, while the compound kimase is used as a name, it does not seem to have a meaning that can be applied here). However, whether this mistake was present in the Enkaku-ji manuscript (which is doubtful, since none of the other versions have this word), or a printer’s error, is unclear.

O-miza [御看座] would refer to the initial inspection of the room by the principal guest*.

O-miza mae no kazari [御看座前の飾], then would mean the arrangement (of the daisu) before said guest had entered the room†. __________ *In the episode that is being described here, this would seem to have been Ashikaga Yoshinori -- who is referred to throughout by his kaimyō [戒名] (the Buddhist name given to an individual after his or her death) of Fukoin-dono [普廣院殿] throughout this entry.

†Za [座], which means “seat,” is used in the sense of shoza [初座] (“opening seat,” in other words, the first part of a chakai) and goza [後座] (“the latter seat,” that is the part of the gathering when the tea is served) -- though this explanation is anachronistic (since the shoza-goza dichotomy did not exist before Jōō's time), and so has been translated “room.”

²Kayō no jūjū naru kazari no sai-sho no kazari ha, itsure ni te mo mōke no kazari to iu nari [カヤウノ重〻ナルカザリノ最初ノカザリハ、イツレニテモマウケノカサリト云也].

This is a rather difficult statement to translate, on account of its complexity (and, frankly, the repetitive use of the word kazari [飾]).

Jūjū-naru kazari [重々なる飾] literally means something like an overlapping series of arrangements -- that is, each succeeding arrangement is begotten by the first (through the process of adding something to it).

Mōkeru [儲ける] means to beget, generate, engender*. In other words, one arrangement engenders the next (by means of adding a new utensil); thus moke no kazari [儲けの飾] means the begotten or derived arrangement

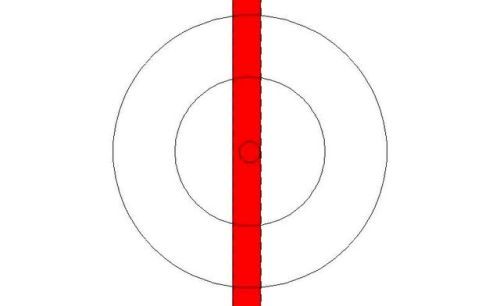

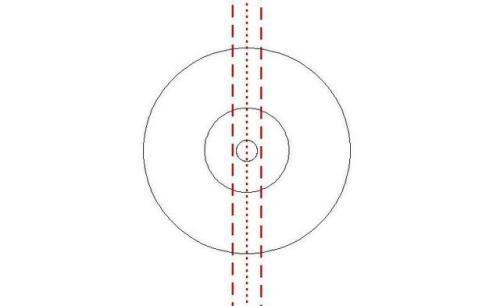

The initial arrangement was modified by the addition of the hishaku to the objects displayed on the ten-ita of the daisu†.

Depending on the circumstances‡, the hishaku is either placed in between the kane**;

or, the hishaku is placed so that it overlaps the left-most yang-kane by one third, as below††.

__________ *Today this word is most commonly used with respect to financial matters, and so means profit, obtain, earn, make (money).

†The hishaku was carried out separately, at the beginning of the temae, because doing so would allow the person who would be serving tea to greet the guest who would be drinking the tea. (If the mizusashi were to be carried out first, it would be impossible for the host to pause elegantly for this exchange of greetings. We must remember that, in the early days, the server was usually one of the dōbō-shū [同朋衆] -- and, generally, the one who was most intimate with the shōgun -- while the person served was usually the shōgun himself, or someone invited by him to receive this honor.)

‡Specifically, the demands of kane-wari, and keeping the total count for the goza yang. This is usually the reason behind such variable orientations.

**The intention is that the daisu should always be yang at the beginning of the temae. When only the furo and hoya are on the ji-ita, and the nagabon is on the ten-ita, the hishaku is placed between the kane, so it will not be counted. This keeps the total count yang.

††After the mizusashi has been brought out, the ji-ita will have three objects associated with yang kane, so the hishaku also has to be moved into an association with a yang-kane, in order to keep the daisu yang.

Note that while I have shown the hishaku overlapping the kane from the left (as it is shown in the Enkaku-ji manuscript, as well as in Tanaka Senshō’s commentary), Shibayama Fugen has it overlapping the kane from the right, as shown below (the dashed representation indicates the hishaku’s original position -- that is, where it was relocated from).

While there is really no rule that would give preference to one or the other, I am inclined to believe Shibayama’s interpretation might be preferred -- since it involves moving the hishaku toward the left only by a little (the subtle change in orientation is what the original text implies). This agrees with the way things are usually done in the Nampō Roku.

³Daisu ni te ha tabi-tabi aru-koto nari [臺子ニテハタビ〰アルコト也].

Tabi-tabi [度々] means oftentimes, frequently, time and again.

In other words, this kind of thing -- where the initial arrangement is subsequently modified over the course of the first several stages of the temae* -- was often seen in the old daisu temae, particularly when the idea was to “treasure,” or do honor to, one of the utensils. __________ *Most of these things came to be pushed into the naka-dachi as the modern period dawned, because they were considered to be too annoying to watch.

However, we must consider these things in terms of the original way that these temae were performed. In the early period -- as is true in this episode -- the host was usually a young man. And the guests took pleasure in watching such a person perform (in much the same way as we enjoy watching something like modern dance).

The host did not walk into the room and proceed to the temae-za, as now. Rather, after crossing the threshold (in several stages), he stood and walked (often across a distance of several mats) to the lower end of the utensil mat. There he sat down, and advanced toward the daisu on his knees (moving whatever he was carrying forward from that seated position). However, according to some scholars, rather than sitting on his knees, the host actually advanced in a squatting position (as was done when moving about the Imperial court), giving the appearance that the person was floating across the mat during this critical point in his temae. How elegantly this was done -- and an elegance of movement, almost feminine, was precisely the characteristic most deeply appreciated in the host's performance in this early period -- had a huge impact on the “success” of the temae.

The character of the performance is vastly different when a young man is doing the temae, in contrast to when an older man is doing it. (This is why it came to be said that “old men” should only officiate in the small room, where their physicality would not be put on public display to anywhere near the same extent as would have been the case in a larger room.)

⁴Seiko nado mo mōke ari [西湖ナトモマウケアリ].

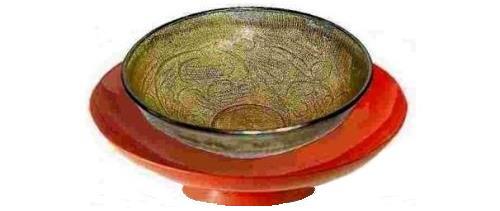

Seiko [西湖] is a reference to a sort of box called a Seikoya [西湖家]*, shown below, in which a souvenir temmoku-chawan was packaged†.

Be that as it may, the point is that in this temae (which will be narrated and discussed later in Book Six), first the temmoku, tied in its Seikoya‡, is displayed on the ten-ita of the daisu. Then, in the initial part of the temae, the host brings out a large round tray on which are arranged a chakin, chasen, and chashaku, and the bowl is removed from the Seikoya box and arranged on a temmoku-dai. Then the chaire is brought out, and the actual service of tea commences.

It is to temae of this sort, where the host performs a number of pre-service actions, that this sentence is alluding. __________ *Xīhú-jiā [西湖家] (Seikoya is the Japanese pronunciation) was apparently the name of a souvenir-shop, located at a scenic spot along the shore of the Xīhú [西湖], “Western Lake,” in Hangzhou, where this bowl and box combination was purchased. The name of the shop was written on the lid of the box (as is common even today -- though usually printed on stickers, rather than written in lacquer). The Xīhú has been a famous scenic area since at least the first century (the earliest known reference to this area is found in the Hàn Shū [漢書], written around 111).

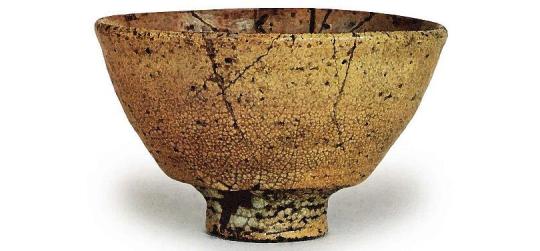

†The original Seikoya is said to have been painted with black lacquer, with the name “Seikoya” written in gold lacquer. The bowl was apparently an ordinary Kenzan-temmoku [建盞天目], such as that seen below.

Another such box, this one owned by Ashikaga Yoshimasa, had the name Jìngshān-sì [徑山寺] (Kinzan-ji, in Japanese; the name of a famous temple located near the “Western Lake”) written on the lid -- apparently having been purchased at a souvenir shop located within the grounds of that temple. Yoshimasa’s Seikoya and its temmoku were destroyed when his storehouse was burned down (it is not known what happened to the other Seikoya, though it is presumed to have been lost during the wars of the Sengoku jidai as well).

It should be added that certain scholars (whose arguments are quoted by Tanaka Senshō in his commentary) state that the Seikoya, and the temmoku bowl that it contained, were used as packaging for special flavored miso (used as a dipping sauce for raw vegetables), that was sold in the gift shop (such things -- flavored with unique local ingredients -- were popular, and relatively inexpensive, souvenirs). This adds weight to the argument that the temmoku “chawan” were not used for drinking tea in China, but were actually made for some other purpose; and came to be used as chawan only in Korea and Japan, after their original contents had been used up, and the bowl was all that remained. In this case, they explain that the indentation, just below the rim, allowed a cover of oiled paper to be tied over the mouth of the bowl, to keep the miso from drying out.

‡As seen in the photo, an elaborate knot was used to tie the Seikoya closed. Untying this knot elegantly was a feat of dexterity in itself; and, at the end of the temae, the knot had to be recreated before the Seikoya could be returned to the ten-ita.

⁵Tsuzuki nari [ツヾキ也].

In other words, the utensils occupy successive kane: the dai-temmoku rests squarely on the central kane; the chashaku is placed squarely on the yin-kane immediately to its right; and the chaire, squarely, on the first yang kane to the right of the central kane.

⁶Hatsu ni ha kaku no gotoki mizusashi nashi ni hoya ha kari ari [初ニハ如此水サシ��シニホヤハカリアリ].

The hoya was placed on the right side of the ji-ita when the daisu was being set up (so that the ji-ita would not appear so empty), and remained there until the mizusashi was brought out from the katte during the first part of the temae.

⁷Mōke no toki ha hishaku kane wo hazushite-arishi ni [マウケノ時ハヒサクカネヲハヅシテアリシニ].

Mōke no toki [儲けの時] means “when (the hishaku) was added to (the ten-ita of the daisu).”

Kane wo hazushite-arishi [カネを外して在りし]: hazushite [外して] means was taken off, displaced; arishi [在りし] means to exist in the state of (having been displaced). This is the situation shown above.

⁸Akamatsu hakobite no kazari no toki, kazu wo kanben-shite kane ni san-bun kakari ni oki-shi nari [赤松ハコビテノカサリノ時、數ヲ勘辯シテカネニ三分カヽリニ置シ也].

Perhaps the wording of this sentence was made deliberately obscure, so that the uninitiated would not understand what was intended.

Akamatsu hakobite no kazari no toki [赤松運びての飾の時]: Akamatsu [赤松] refers to Akamatsu Sadamura; hakobite no kazari no toki [運びての飾の時] is alluding to the next step in the temae, where the seiji unryu-mizusashi is brought out from the katte and arranged on the ji-ita of the daisu.

The phrase is written in the past tense, because it is only after the mizusashi has been brought out, arranged on the ji-ita, then filled with water, and the hoya placed between the furo and mizusashi (as shown above), that the hishaku is moved onto the kane.

Kazu wo kanben-shite [數を勘辯して] means something like “in order to make allowances* for the [increased] number [of objects]....”

Kane ni san-bun kakari ni oki-shi nari [カネに三分掛かりに置し]: kane ni san-bun kakari [カネに三分掛かり] means to overlap the kane by one-third; oki-suru [置きする] means to (actively) place, or reposition, something.

This sentence is referring to the repositioning of the hishaku -- after the mizusashi and hoya have been arranged on the ji-ita.

This is the final step in the “pre-temae,” as it were. From this point on, Sadamura would have begun the actual service of tea for the shōgun Yoshinori. ___________ *Kanben-suru [勘辯する] literally means to pardon or forgive. Here the nuance is to make allowances for (the increased number of utensils), by changing the position of the hishaku, so it will not be counted.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hey, could you tell me what Kirnamala’s story is because I was not able to understand Wikipedia’s version 😭

The actual ‘Arun Barun Kiranmala’ story right??? 😭😭

Yeah don't go to wikipedia it's shit there, and that serial thing also exist so not good

This is actually my favourite Thakumar Jhuli tale I love it sooooo much Kiranmala is a fucking Queen, she'd always be my favourite girl.

Now get ready cuz this post is gonna be LOOOOOONGGGG

Also trigger warnings: mention of infanticide... Kinda? and bitchass peoples all over, killing those bitchass people and swearings.

So the story is kind of simple, it starts with the King (like any other tales)

The king was out one day, roaming around the city in disguise to know what people's problems were and stuff and hears this three sisters talking with each other.

The eldest said how she if she married (I forgot what she said sorry TvT) she'd be the happiest

The second one said that if she married the royal cook she'd be the happiest

And the youngest said, she'd be the happiest if she married the king himself and became the queen (lol! confidence gurlie confidence) and the others laughed at her

.......

So the king leaves after hearing everything, and next day he calls for the sisters to his court. Now obviously the sisters are scared shitless cause whytf was the king calling for them... So they go to the court

And king dude asks them to say what they were talking about last night, and the older two fearfully tells him. But the youngest gets obviously embarrassed and scared thinking she's gonna get punished. So the king reassures them, that they'd get what they had wished for.

So yeah oldest sis got married to her man of dreams and the middle one also married the cook. And king dude married the youngest one and made her the queen (I mean that's some really impressive rizz game he got tbh 🗿💀)

Now they are married and should be happy just as they wanted right? Yeah no lol then how would the story progress...

.......

So some years pass and the queen is now pregnant and the king dude, makes a diamond studded gold gold marble room for her to give birth (what do you call that? In bengali we say Atur Ghor)

And now queen requests him to let her sisters visit cuz she was missing them and wanted them to be present in the Atur Ghor and be her midwives. And the king agrees cause he couldn't deny anything to his wife.

But but but when those sisters came to the palace, they were in awe of how luxuriously their sister was living as the queen, and grew jealous.

So now the queen gives birth to a beautiful baby boy and the what the sisters do? Puts him in a jar, stuffs his mouth with salf and cotton and floats him in the river 💀 (like the audacity!!!)

The king asks what happened and they reply with that the queen had given birth to a puppy 💀 and shows him a new born puppy.

He just stays silent, obviously heartbroken wondering what happened...

So next year the queen is again pregnant and the sisters again come, she gives birth to another beautiful baby boy and they again stuff his mouth with salt and cotton and puts him in a jar, again floating him in the river 💀

The king again asks what happened and this time they reply she gave birth to a kitten showing him a kitten fetus thing and he again stays silent wondering how all thus was happening.

Third year same shit, a baby girl is born and the evil bitches again puts the cutie in a jar and floats her in the river like her brothers... :(

And shows the king a wooden doll, a literal freaking wooden doll 💀💀

.....

This time the king sits in despair and his people tells him, the queen must be some bad omen, alakshmi, a monster since the same thing keeps repeating every year, and he wonders it mist be true she must be some witch or something.

The people tells him, he should throw her away and he decides he'd do that and actually throws out poor queen :( out of the kingdom, not before the people publically shames her and all.... Yk the typical beizzati karna... 💀

And those evil psycho bitches happily go back to their own houses.

......

Now this side, a brahmin was bathing in the river when he noticed a jar floating. Not just any jar but a jar with a baby crying in it. So he hurries to get the jar and sees a beautiful godly baby boy in it. He washes all the salt and stuff and brings the baby home with him.

Next year he sees another jar, this time another beautiful baby boy in it and yet again he brings it home with him

Again same things happen the following year and he sees another jar, this time a beautiful baby girl in it, and he as usual brings her home with him.

Since he had no kid he adopts the trio as his own and decides to raise them.

AND THE ARE THE ICONIC TRIO — ARUN, BARUN AND ✨KIRANMALA✨

......

The kids grow up under his care, and they were like dev shishu, beautiful talented brightening the whole house.

Since they came in his life, the brahmin became RICH. Like good crops, more than enough milk from the cow, and everything. He became successful. They were like his lucky charms.

So now the kids are grown up and they are exceptional in everything, the bestest children anyone can ask for 😌 They take care of the house, learn scriptures from him and does everything, helps others and animals, looks good (yes ik this is propaganda)

One day brahmin calls them and caresses their head, telling them to live properly and happily and a lot more emotional stuff and... dude... dies... 💀 (ahh sadness we love you)

So Arun Barun Kiranmala becomes sad and cry that their father is dead and decides to follow the instructions and live harmoniously together.

.......

So back to daddy dearest king, he's in dispression for all this years thinking his kingdom must be cursed or something, and decides he'd go for hunting.

But when he was hunting, some shit happens... Sky lord got angry and made a hell lot of storms and rain, practically ruining his little kitty party and making him lose his way.

Next day he's roaming around looking for any house because he's so thirsty and would probably die without water.

He finds a house (you guessed correct!) and goes there begging for some water, and Arun Barun Kiranmala stares at him like 😶 as they bring him water to drink. He drinks it and then looks at the trio in awe, wondering who these godly looking younglings are. He asks them and they say they are brahmin's kids. (Love ya papa 🗿)

Hearing them, he kind of becomes emotional as he feels his heart beating faster (instincts? Ig..?) and cries a little as he tells them he's the sad king of that kingdom and if they even need anything they should tell him. Then he leaves.

......

So, now our baddie Kiranmala, innocently asks her brothers that “what does a king have?” and they say that they don't exactly know but have read in the books that a king has elephants, horses and palaces. So Kiranmala says that, “fuck elephants and horses we can't find them but make me a palace” 🗿 (I love her so much)

So her pookie cookie brothers say “okay” and gets to work. They literally work hard for 1 year 36 days nonstop without caring about hunger or thrist and built the palace. On exactly 1 year 36 days the palace is ready (yayayaya!!!)

Now the palace is made of marbles and diamonds and many other stones, with silver doors, golden tops, gardens, flowers, trees everything you can imagine. It's beautiful af. ✨🗿🤌 (Arun Barun legendary people)

.....

Now one day a sanyasi comes to their palace and while they were talking to him, he rambles about great many things like silver tree with golden fruit, a diamond like water fountain and a golden bird saying only those things would suit such a beautiful palace like the trio's.

So they ask where the can find those things and the sanyasi gives them the location and leaves. It's in some mystic mountain and all i forgot the details lol

.....

Arun decided he'd go get those things, and instructs Barun and Kiranmala to stay home and wait for him, giving them a sword saying if the sword starts to rust they'll know he's dead.

So months pass and Arun hasn't returned and the other two check his sword each day to see. But one day Barun notices the rusting, and breaks down crying, as he decides to go for himself.

He gives Kiranmala a bow and arrow saying if the tip of the arrow becomes blunt and the bow string breaks she'd know he's dead too.

So now Kiran is left home grieving and Barun is on his way to the mountain.

As Barun reaches the mountain, he sees the most beautiful place on earth, apsaras dancing and singing and all the magical creature and fog and everything. But suddenly he hears some voices calling his name from behind him and he turns around and BOOM he's a fucking stone statue (that's why you don't respond to strangers 🗿💀)

Barun wonders who'd save them as he realises both him and Arun are stone now.

......

Back home Kiranmala notices the blunt arrow tip and broken bow string realising both her brothers are gone, but she doesn't cry.

My girlie does all her house chores and then gets dressed like a warrior then kisses that cow's (it's name was Kajal Lata btw) bachhra and sets out for the mountain 🗿

And she's a badass, she's going by the speed of lighting not even stopping at anything. It takes her 33 days to reach the mountain.

Once she's at the foot of the mountain it's as if all kinds of calamities break down on it. Monsters and demons and ghost and wild animals all surrounds her and those weird ass noices come from all angles asking her to look at them behind, mistaking her for a prince.

BUT my bbg literally stops at nothing and runs the horse straight to the top where the silver tree and the fountain was, gripping her sword and all. 🗿🗿 (I love her so much ugghhh)

......

Once she reaches the tree, the golden bird tells her (yes it talks) to take all the things— the tree, the fruits, the sword, the bow, the arrow, the gems, the bird itself. Every single thing over there and then to beat the drum. And Kiranmala does as the birby say and as she beats the drum, all the chaos stops at the mountain and it becomes quiet. (Ok yeah maybe listen to birds who knows... I still hate birds tho)

Then birby tells her to sprinkle the entire mountain with that fountain water and as she does that, all those stone statues of all the people who had been there for so long turns back into humans and they all pay respect to her 🗿 Bahubali style 🗿 calling her the greatest in 7 yugas (exaggeration but honestly she's the QUEEN 👑 🗿✨)

Then Arun and Barun gets emotional and hugs her and yay!

......

They get back to their palace (which now isn't a palace but a whole ass land of wonder) and plants the trees and it starts to grow diamond and and gold and pearl and all. And that birby sits at the diamond tree and starts to sing. Then they put the fucking fountain amidst all these. 💀

And then they start to live their happily (you thought it's the ending? Nahi climax abhi baki haiiii)

Then one day birby tells them that they should invite the king to eat. So Arun Barun and Kiranmala are like

The trio: but what will we feed him??

Birby: I'll see that, just invite him

The trio: ok

And so they send him invitation 🗿✨

.....

This side daddy dearest hears about the wonderland the trio had created and is surprised those kiddos did so much, and then he recieves the invitation and he's like “hmmm gotta go and see for myself now aight”

And so Rajaji sets for their palace. Once he's there he's literally shik shaak shock seeing all the treasures and things everything, he makes the shocked pikachu face as he slowly starts to get emotional again, and cries badly thinking about not having kids and how he wished Arun Barun Kiranmala were his own kids.

He tells them to take him inside, and he's even more shocked when he sees the inside of the palace.

.......

Then they make him sit at the dining hall, and brings out all the varieties of foods, and now king bro is excited to eat because he's smelling the good food (feel you bro feel you)

All types of sweets, and foods and everything imaginable. So he picks up a bite but drops it asap as he realises everything infront of him is made of gold coins and gems.

So now he asks them if they are making fun of him or joking with him, and he gets the reply “why can't you eat it???”

King dude: it's all gold!!

???: yeah but why can't you eat it??

He sees a golden bird is talking to him and

King: yeah but it's fucking gold!!!

Birby: can a human give birth to a puppy??

King: huh?

Birby: tell me can a human give birth to a kitten??

King: ...huhh??

Birby: tell me king if a human can give birth to a wooden doll why can't a human eat gold???

King: ..... you're right.... Ohh how wrong I was!

.......

So basically the birby lectures dude about everything and makes him realises his mistake, as he breaks down crying (atleast bro ain't a toxic alpha male 💀🤌) as the bird says that these three beauties are his real kids, and those evil bitches masi(s) were the reason for all the puppy kitten wooden doll drama.

They all hug as the king cries in despair saying how he wishes his queen was with them right now. And birby tells Arun Barun Kiranmala that their mother stays in a hut on the other side of the river and instructs them to bring her as she's living her days in struggle and sadness (i mean that's obvious 💀)

.....

They bring back the queen, the king shifts his capital to that wonderland and everyone stays happily yay!

Aaaand as for those evil bitches, yeah king dude sends his men to burn down their houses and then nail them and bury them alive 💀💀

........

SOOOO THAT'S THE END OF THE STORY YAY

Im sorry it took me so long hehe,and even more sorry the post is so long (and not proof read so forgive the mistakes and typos ill see it soon)

Honestly it's my favourite story ever I love Kiranmala so much she's my babygirl shdggdbdsnndbd

#arun barun kiranmala#kiranmala#kiranmala is a queen#thakumar jhuli#bengali thakumar jhuli#bengali literature#banglablr#cutu cutu mutuals#shaku answers#desiblr#shaku tells stories#shaku does commentary#rupkothar golpo

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

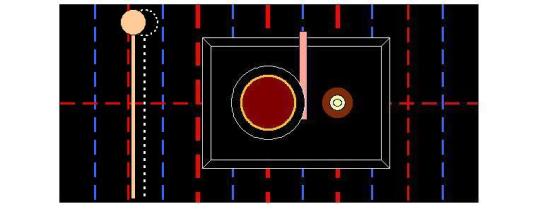

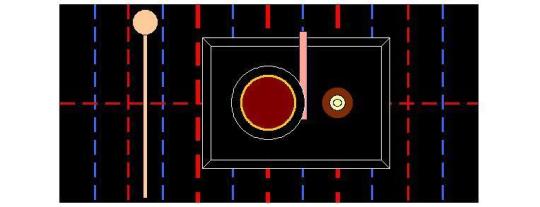

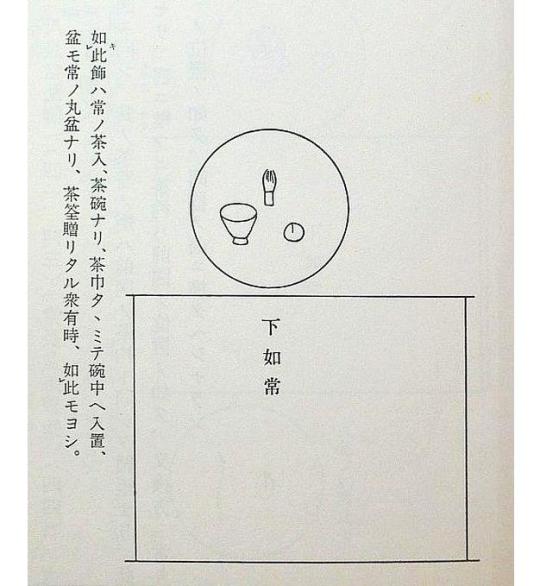

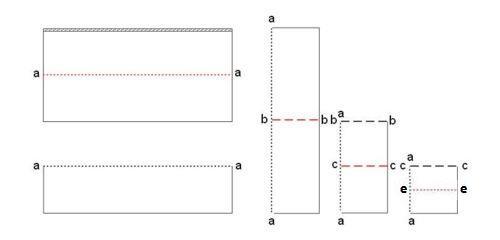

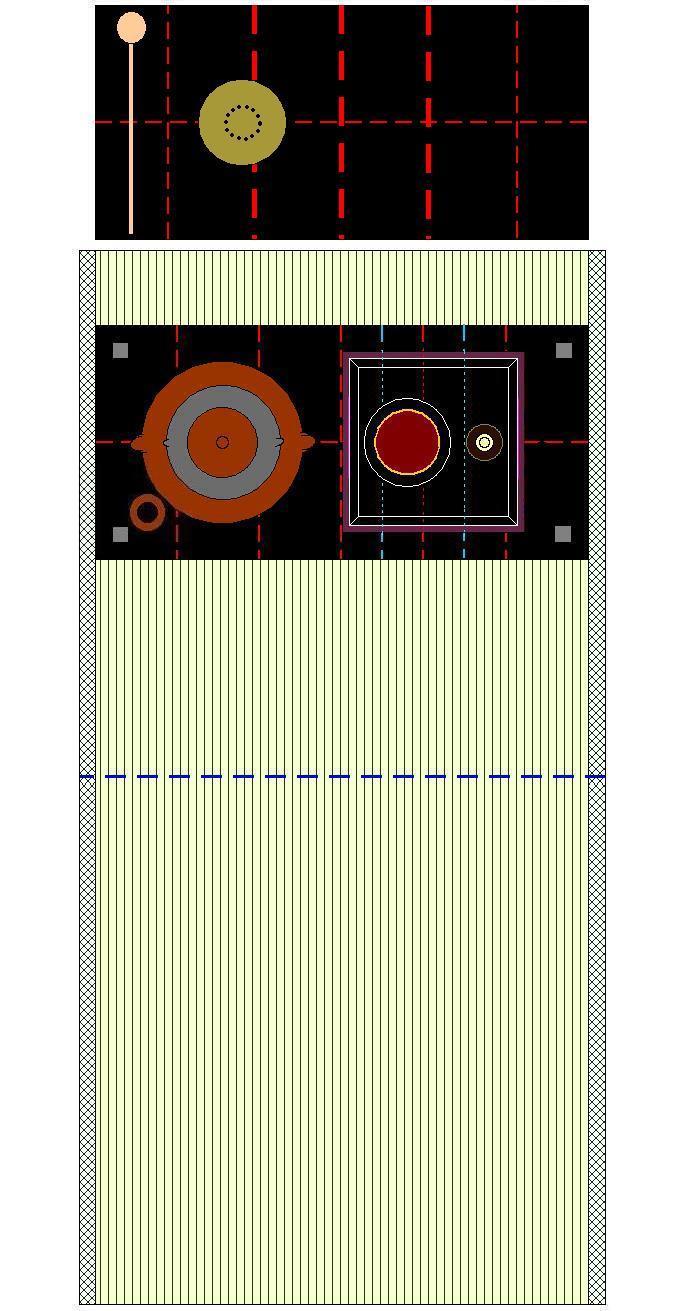

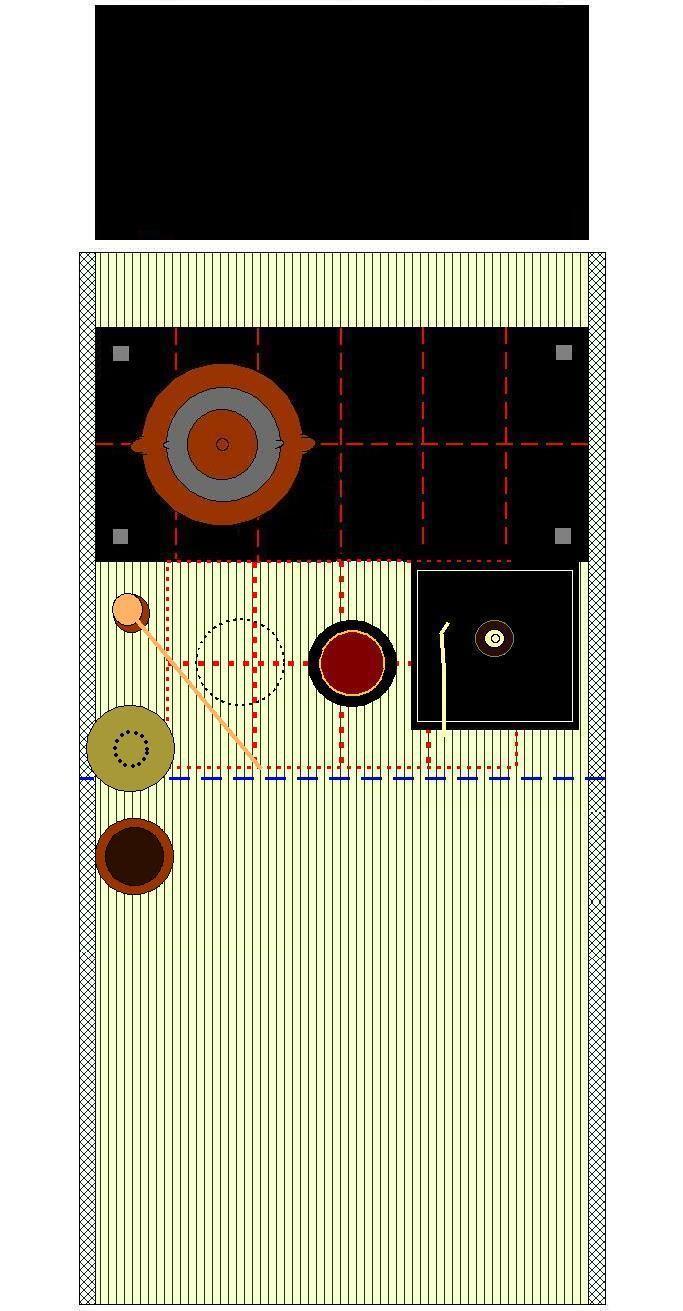

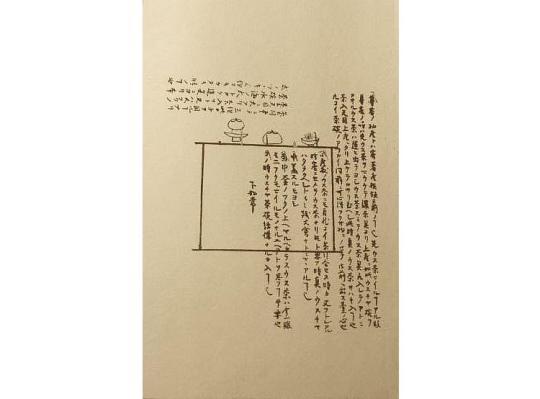

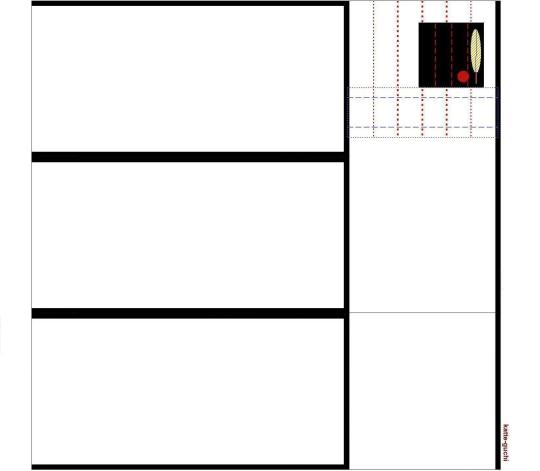

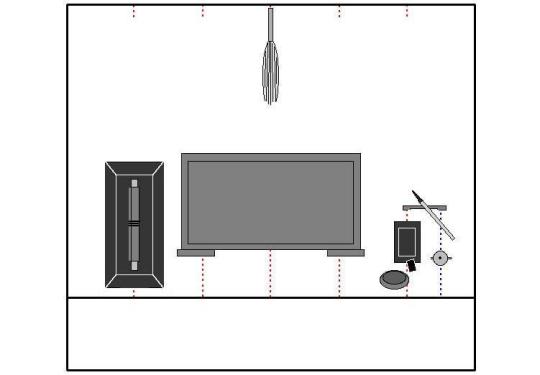

Nampō Roku, Book 5 (8): the Ordinary Round Tray, with the Chasen Displayed Apart from the Chawan¹.

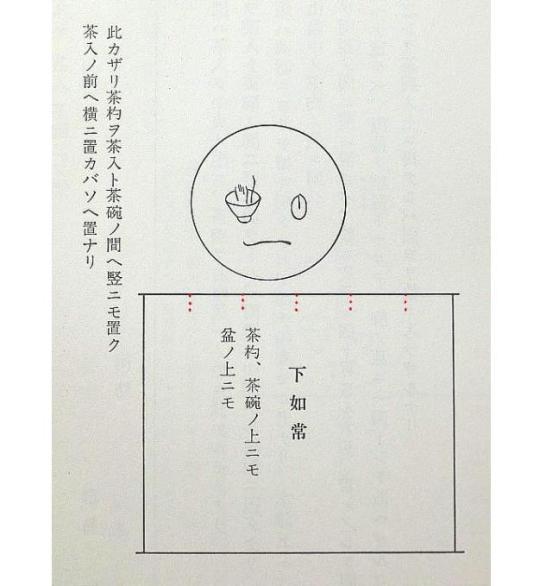

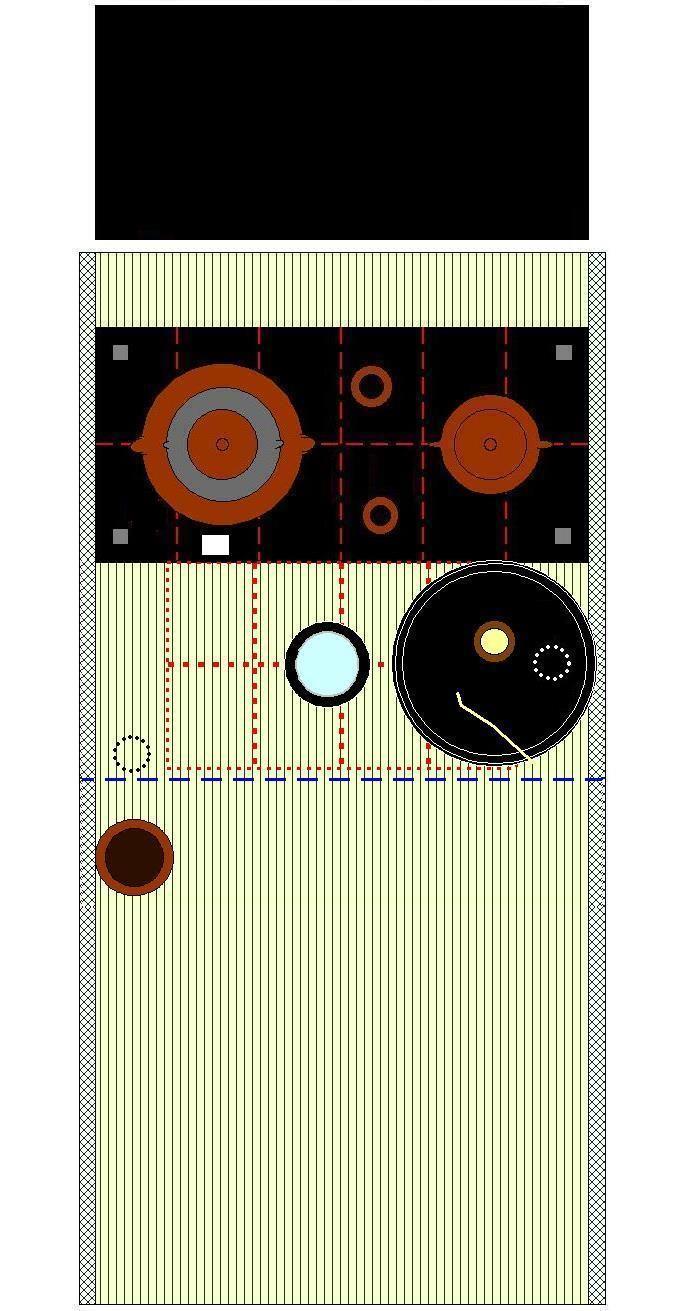

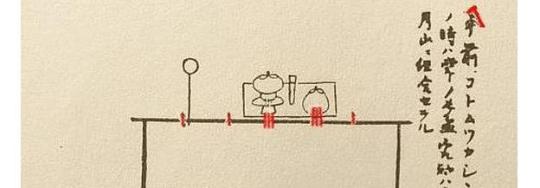

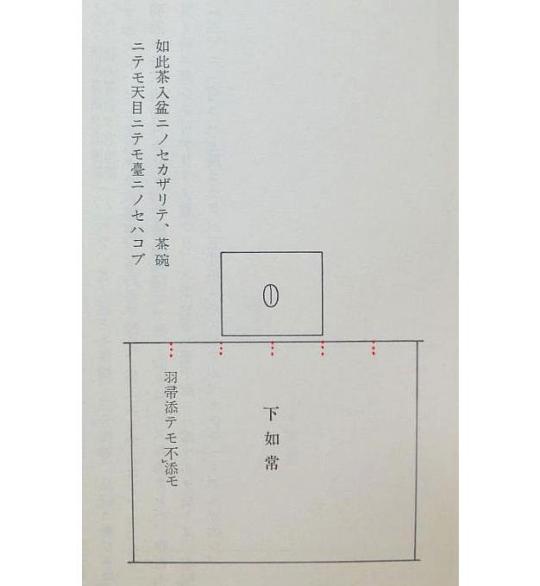

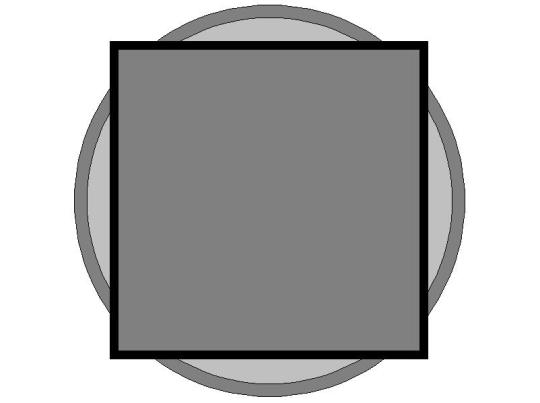

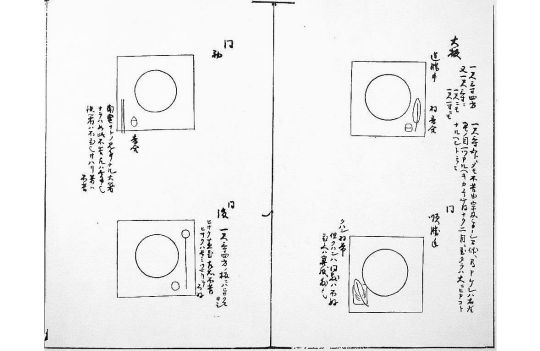

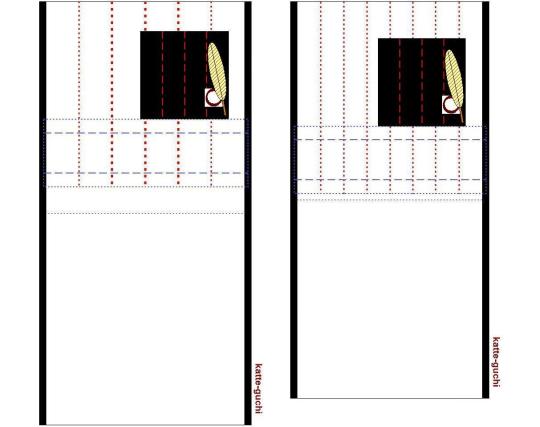

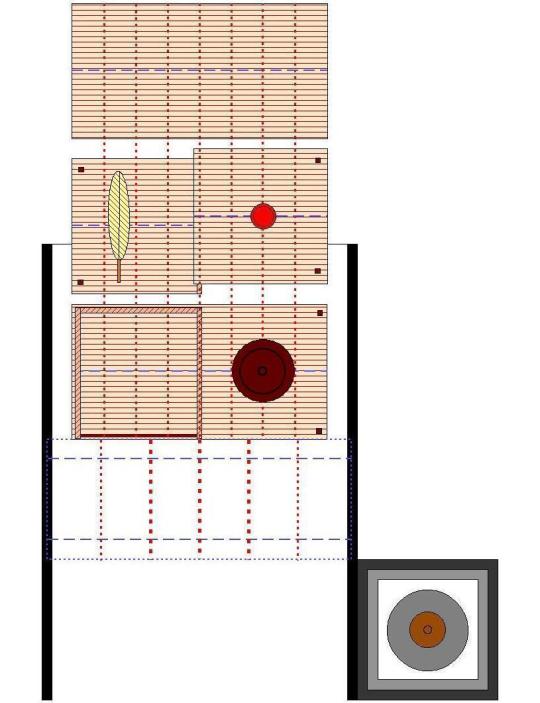

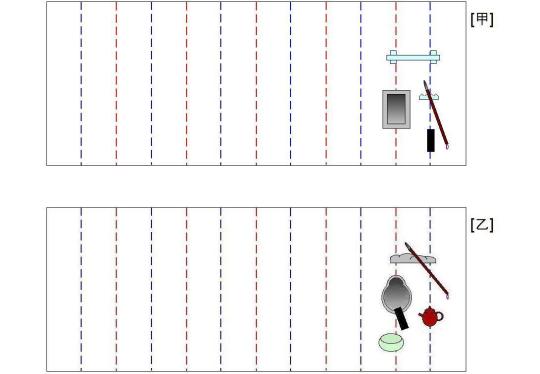

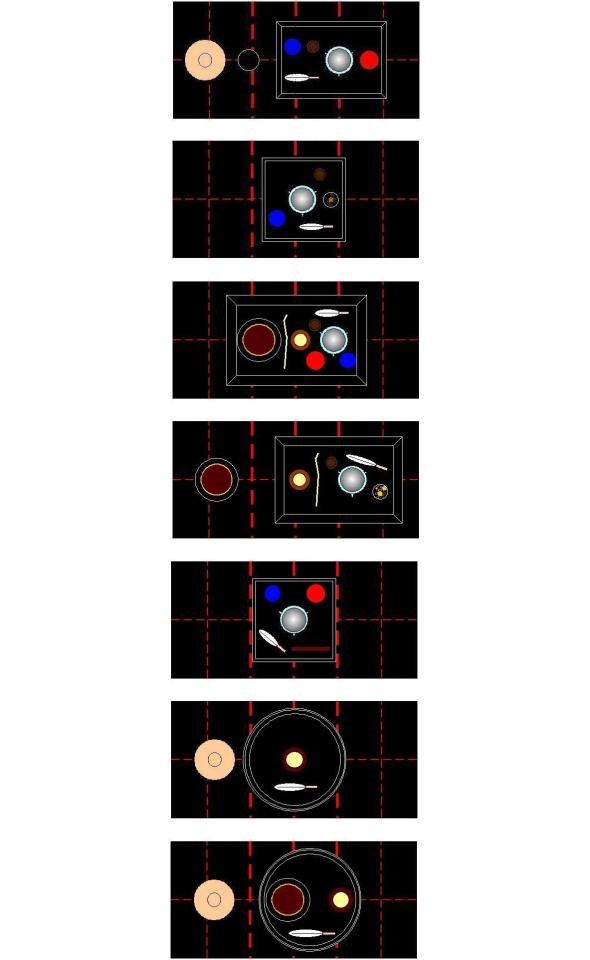

8) Tsune no maru-bon ・ chasen midare-kazari [常丸盆・茶筌乱飾]².

[The writing reads: (between the ten-ita and the ji-ita) shita jo-jō (下如常)³; (to the left of the drawing of the daisu) kaku no gotoki kazari ha tsune no chaire, chawan nari (如此飾ハ常ノ茶入、茶碗ナリ)⁴, chakin tatamite wan naka (h)e iri-oki (茶巾タヽミテ碗中ヘ入置)⁵, bon mo tsune no maru-bon nari (盆モ常ノ丸盆ナリ)⁶, chasen okuri-tari shu aru-toki, kaku no gotoki mo yoshi (茶筌贈リタル衆有時、如此モヨシ)⁷.]

_________________________

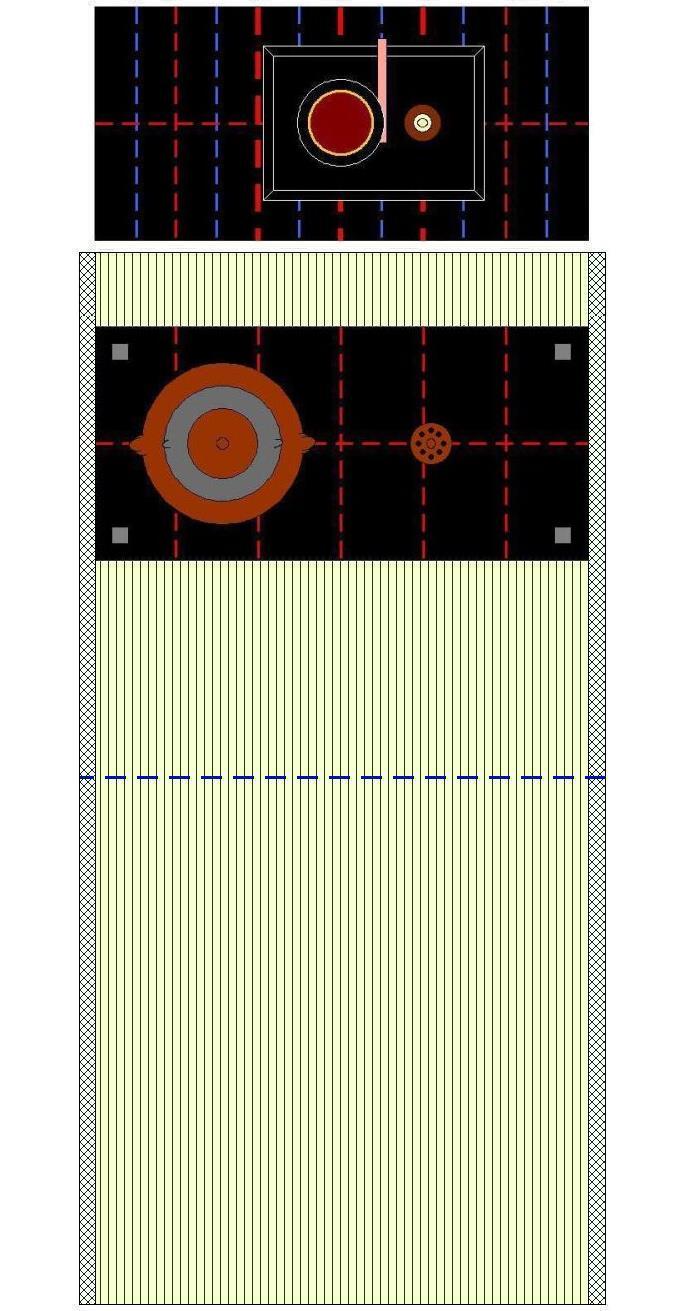

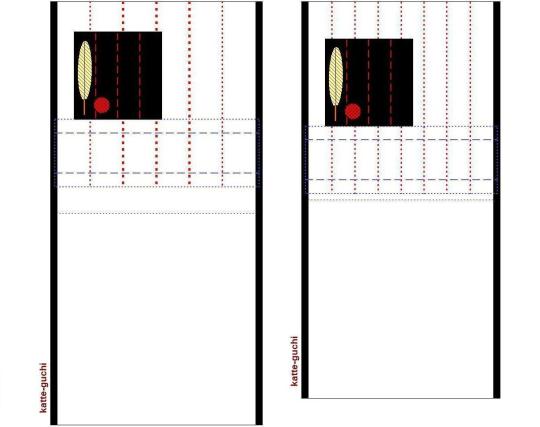

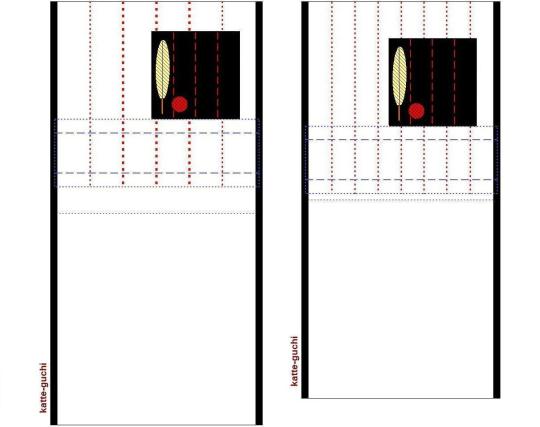

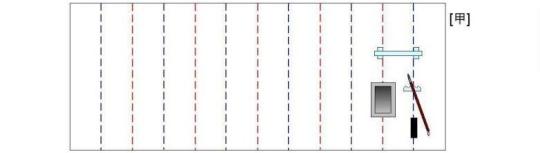

◎ For whatever reason, the five kane are not indicated on this sketch. It was assumed (by Shibayama Fugen, as well as this author) that the chawan and chaire are oriented in the same manner as in the previous arrangement.

He also points out that “the chasen here is oriented on the same kane as was the chashaku [when placed between the chaire and the chawan] in the previous arrangement.” (That orientation was, of course, not depicted in the sketch.)

¹Midare-kazari [乱飾] refers to the case where the chasen is displayed apart from the chawan.

Sometimes the chasen stands upright, and sometimes it rests on the chakin.

²Tsune no maru-bon ・ chasen midare-kazari [常丸盆・茶筌乱飾].

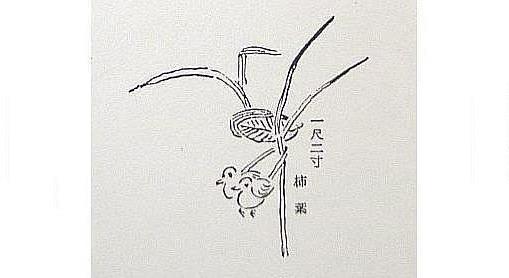

Tsune no maru-bon [常丸盆] refers to the naka maru-bon [中丸盆] described in the previous installment. The tray was 1-shaku 2-sun in diameter, though a raised band running around the middle of the side increased that to 1-shaku 2-sun 3-bu.

At the time when these arrangements were documented, the naka maru-bon was the copy made by Haneda Gorō for Ashikaga Yoshimasa, painted with kagami-nuri, without any other decoration (though the raised band was preserved in his copy), while many later copies were also available.

³Shita jo-jō [下如常].

Referring to the kaigu displayed on the ji-ita of the daisu, their arrangement was as usual.

⁴Kaku no gotoki kazari ha tsune no chaire, chawan nari [如此飾ハ常ノ茶入、茶碗ナリ].

“As shown [here], this arrangement is for an ordinary chaire and an ordinary chawan.”

An “ordinary chaire” was, at the time when the details of this arrangement were being finalized, usually a large katatsuki, measuring 2-sun 5-bu in diameter. Usually it would have been a karamono chaire, though, since the middle of the sixteenth century old Seto chaire were also being used in this way.

An “ordinary chawan” is more difficult to define, though it, too, would have been imported from the continent. Since Shukō’s day, the usual chawan for wabi-no-chanoyu (of which this is one arrangement) was a large chawan. Shukō’s large chawan were the Shukō-chawan [珠光茶碗], which measured 5-sun 2-bu in diameter, and his ido-chawan (the bowl now known as the Tsutsu-i-zutsu [筒井筒]), which measures 4-sun 7-bu across. The bowls which entered use during Jōō’s lifetime were generally 4-sun 9-bu, and so midway between the earlier extremes.

A chawan of a size similar to Shukō’s beloved ido-chawan could be used for this arrangement easily*, but as the chawan gets larger, things become more difficult, due to the size of the tray.

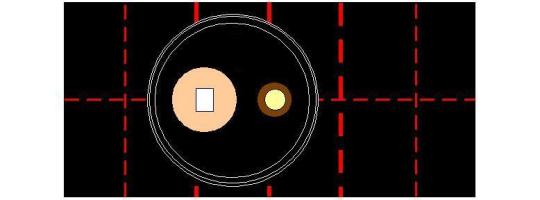

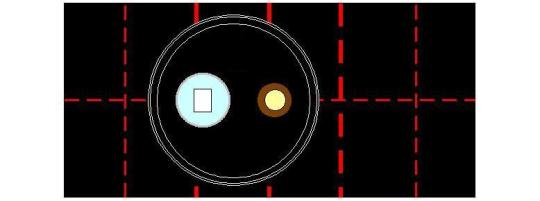

Small chawan were also available, albeit rarely seen (apart from the various types of temmoku)†. These bowls (which appear to be what is featured in the sketch found in Shibayama Fugen’s commentary) usually measure around 4-sun in diameter‡. ___________ *When arranged together on the naka maru-bon, there is a space of 1-sun 5-bu between the chaire and a chawan of a size similar to Shukō’s ido bowl. This is shown below.

The difference in where the tray is placed between what is shown above, and the arrangement using a small chawan, below, is very small (a matter of just over 1-bu). But as the chawan gets larger, the deviation increases.

†The separation between a small chawan and the chaire, on the tray, is 2-sun, as represented in the following sketch.

‡Small chawan became more and more available over the course of the sixteenth century, and they became increasingly the norm starting in the 1570s -- with the advent of locally made bowls. The apparent preference for a small bowl shown by the author of the kaki-ire is probably anachronistic, and reflective of Edo period sensibilities.

⁵Chakin tatamite wan naka [h]e iri-oki [茶巾タヽミテ碗中ヘ入置].

“After the chakin has been folded, it is placed inside the chawan.”

In the case of a temmoku (and, presumably, other chawan that are used in the same way), the chakin is folded as shown below.

The chakin was placed on the bottom of the chawan, as shown below -- flat, but with a slight pinch in the middle (to make it easier to pick up).

For a large chawan (such as an ido-chawan), the chakin was folded a little differently.

⁶Bon mo tsune no maru-bon nari [盆モ常ノ丸盆ナリ].

“The tray is also the ordinary (naka) maru-bon.”

It appears that the person responsible for this kaki-ire understood the adjective tsune no [常の]* in the title to refer to the collection of utensils as a whole. So they decided to add that the tray was also the usual one that was traditionally used with the daisu†. __________ *Tsune no [常の] means “ordinary,” “usual.”

†The original Haneda Gorō-made copy of the naka maru-bon is currently in the possession of the Nishi Hongan-ji [西本願寺] in Kyōto, where it is used to display the famous bonsan [盆山] Zan-setsu [殘雪] and Sue-no-matsuyama [末ノ松山] -- both of which eventually passed from Ashikaga Yoshimasa to the Ishiyama Hongan-ji [石山本願寺], and thence to the Nishi Hongan-ji, when that temple was reestablished (on Hideyoshi’s orders, as two competing congregations) in Kyōto.

Yoshimasa himself established the precedent for using this tray in this manner (because, among the original six meibutsu trays, only the original naka maru-bon had a brass plate inlaid into the face of the tray, which would protect it from being damaged by the granitic sand that was traditionally used in the display of a bon-san). And though Haneda Gorō’s copy lacked this brass plate, the copy continued to be used in the original manner.

By Jōō's time Haneda Gorō's copy had been so badly damaged that it could no longer be used for chanoyu. Consequently, high-quality copies of Gorō's tray had proliferated between the end of the fifteenth century and Jōō's day, since this was one of the most popular trays employed by the machi-shū chajin (whose usages are preserved in Book Five of the Nampō Roku).

Note that in the photo above, the viewing-stone (Sue no matsuyama) has been placed on a piece of coarse paper, rather than a bed of sand.

⁷Chasen okuri-taru shu aru-toki, kaku no gotoki mo yoshi [茶筌贈リタル衆有時、如此モヨシ].

“When the people who presented the chasen [to the host] are present [as the guests], it is appropriate to do things like this.”

The circumstances surrounding this statement are difficult to comprehend (since shū [衆] usually refers to a large group of people, the masses); and while it could possibly mean the group of guests, it can never refer to a single member of a group. Furthermore, if it does refer to the group of guests as a whole, it is difficult to imagine them all chipping in to buy the host a chasen (especially during the Edo period -- we must remember that these kaki-ire appeared sometime after 1690 -- when chasen were being mass-produced, so that their cost was no longer prohibitive). Perhaps it is addressing a situation where a chasen was presented to the host as a token on an auspicious occasion -- such as at the new year -- though I can find no references to any such historical practice. At any rate, this means that whenever the host is making use of the chasen that was presented to him by the people to whom he is serving tea, arranging the naka maru-bon in this way is appropriate -- since it, in a sense, it might be considered a way to focus the attention on the chasen. Possibly it was the result of a misinterpretation of the expression “chasen-kazari” [茶筅飾] (which was a wabi version of midare-kazari, albeit one intended to draw the guests’ attention, not to the chasen, but to the chawan or chaire) -- though this hardly seems the sort of mistake that we would expect scholars to commit.

Shibayama Fugen declines to make any comment on this statement at all.

While this line speaks about the chasen, no mention has been made in the kaki-ire, nor in the sketch, about what to do with the chashaku. However, both Shibayama Fugen and Katagiri Sadamasa (who included this arrangement in the second of his treatises on the use of the daisu in Jōō’s period) indicate that the chashaku should be displayed horizontally in front of the chawan and chaire, as in the previous arrangement. This idea is illustrated in a sketch from Sekishū’s manuscript (below).

Here this illustration has been redrawn to show the arrangement of the objects on the naka maru-bon when a large chawan is used,

and when the chawan is a small bowl.

——————————————–———-—————————————————

◎ Analysis of the Arrangement.

Above, the arrangement of the daisu is shown when a large chawan is used (the distance between the chawan and the chaire is 1-sun 5-bu); and, below, the temae.

And here the same when a small chawan is used:

◦ the initial kazari (the space between the chawan and the chaire is 2-sun);

◦ and the arrangement of the utensils on the mat in front of the daisu during the temae.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 5 (25.1), Appendix: Pictorial Representations of the Utensils Mentioned in the Previous Post [Nampō Roku, Book 5 (25)].

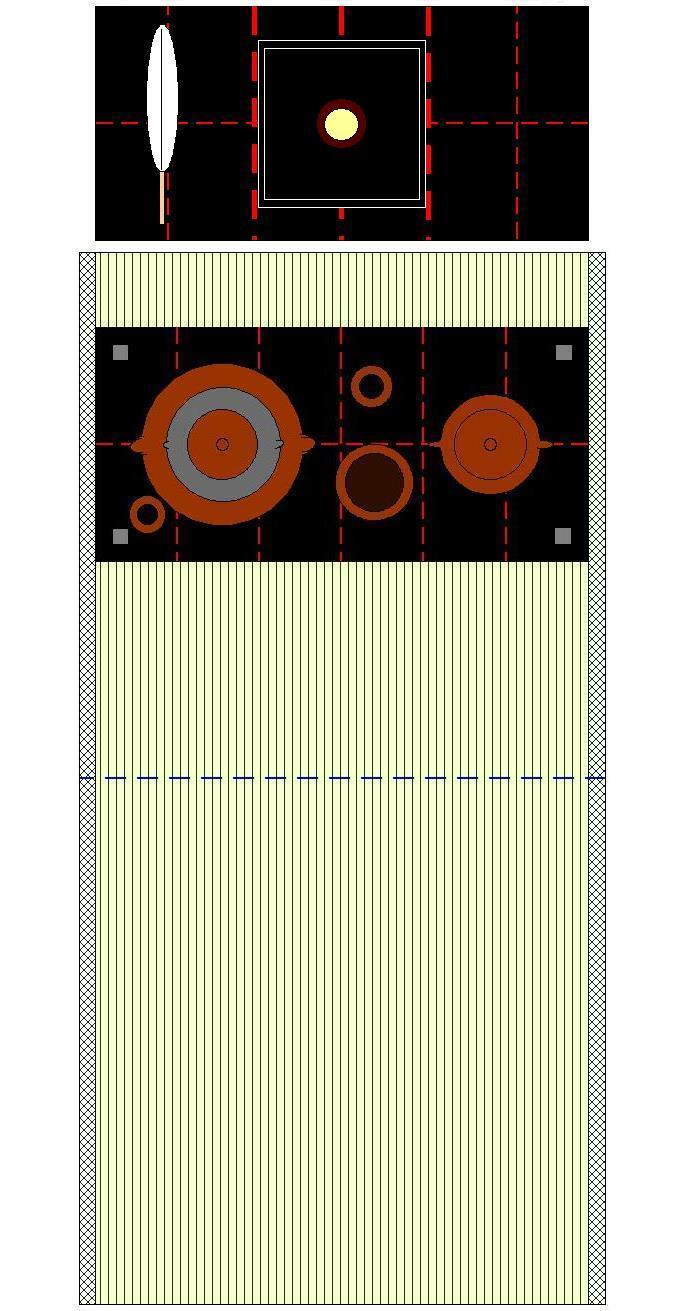

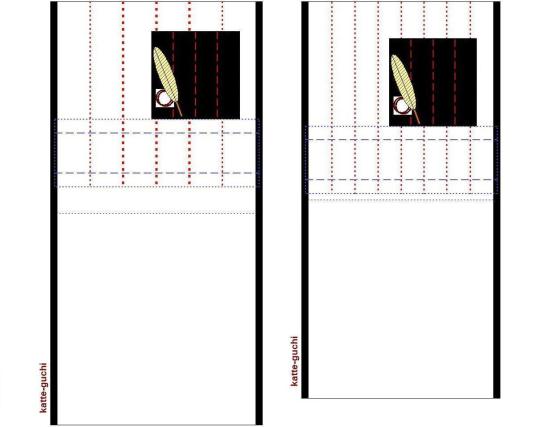

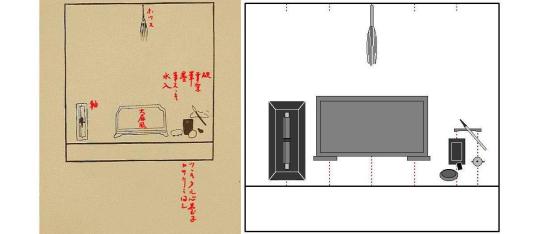

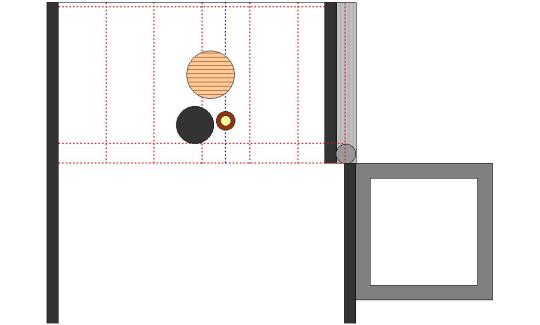

◎ This appendix presents the collection of photographic images that should be associated with the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 5 (25): the Display of the Sorori [ソロリ], Gōsu [合子], and Shishi [獅子].

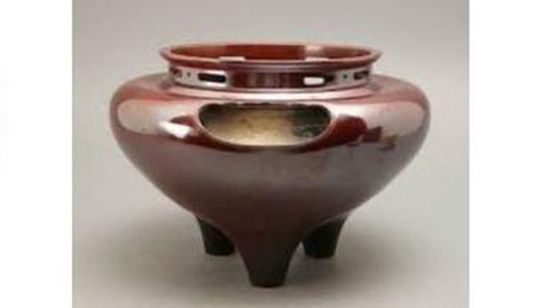

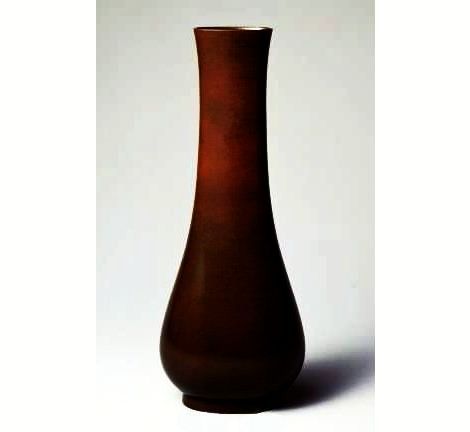

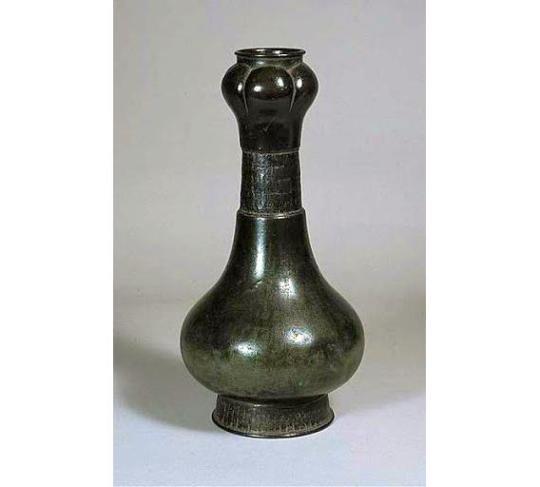

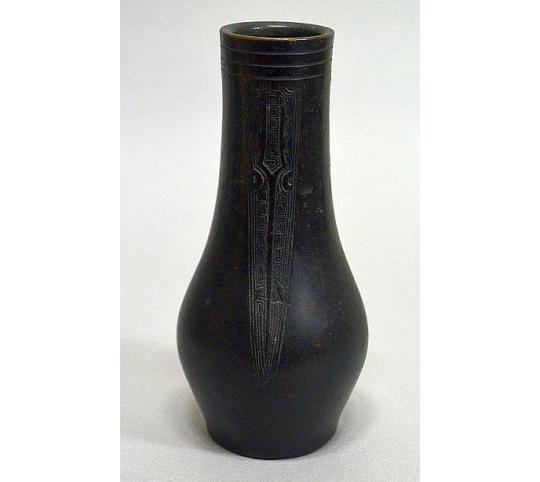

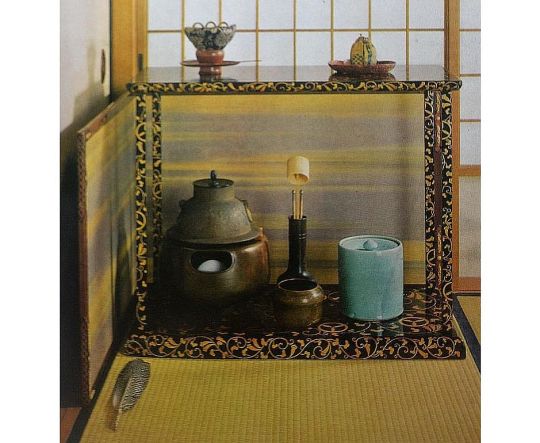

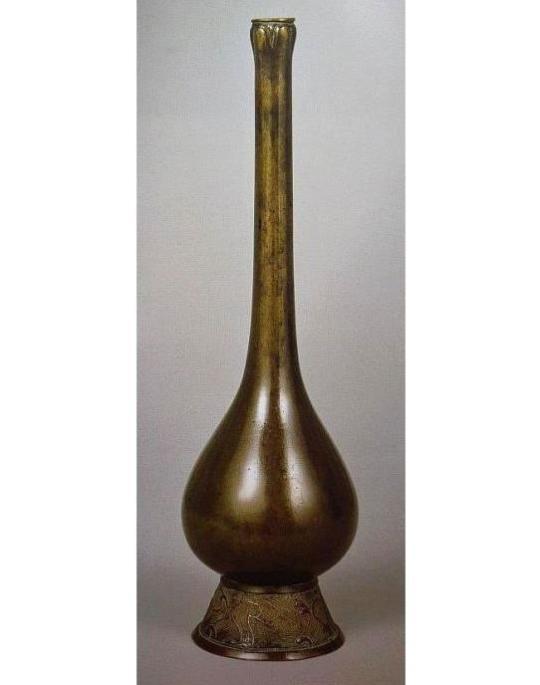

Due to the length of the previous post, it was impossible to include images of all of the different utensils mentioned in the text. As a result, rather than show pictures of only some of the objects, it seemed best to create an appendix, wherein I can include photos of all of the utensils that were used in ancient times as the kaigu on the ji-ita of the daisu. It is important for the reader to understand that the matched sets of kaigu that are commonly sold today did not begin to appear until the second half of the sixteenth century¹, and even then, the preference seems to have been for pieces selected independently, so that they would complement each other both in terms of shape and decoration, and color.

While most of these things were made of bronze, this metal was available in a range of different colors during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. And while some of the colors were the result of natural oxidation, the Chinese and Koreans were expert at producing specific colors. Newly cast bronze is yellowish: this is called ō-dō [黄銅] -- and this name is used even when slight natural oxidation occurs. The most common rich brown color is called karakane [カラカネ]². Continuing to treat the metal³ results in a purplish shade, which is known as shi-dō [紫銅].

As bronze ages, it naturally turns black (this is called ko-dō [胡銅]⁴), and then green (sei-dō [青銅]). While the color can indicate a piece’s age, both of these colors, too, have been created artificially since antiquity.

I. Kama [釜].

◦ Sha-jiku kama [車軸釜].

◦ Kiri-gama [桐釜]⁵.

II. Furo [風爐]⁶.

◦ Dai Chōsen-buro [大朝鮮風爐].

III. Mizusashi [水指].

◦ Mumon mizusashi [無紋 水指];

◦ Minna-guchi mizusashi [皆口 水指]⁷.

IV. Hishaku-tate [柄杓立].

◦ Sorori [ソロリ, 曽呂利];

◦ Kōji-guchi [柑子口];

◦ Momo-jiri [桃尻]⁸.

V. Futaoki [蓋置].

◦ Ya-gaku shishi [夜學獅子];

◦ Mikotonori-no-shirushi [勅印]⁹.

VI. Mizu-koboshi [水飜].

◦ Gōsu [合子, 盒子];

◦ Sori-guchi [ソリ口, 反り 口]¹⁰;

◦ Mimi-guchi [耳口]¹¹.

_________________________

¹The Hosokawa family owns one of the earliest sets known, procured (perhaps ordered) while Hosokawa Tadaoki [細川忠興; 1563 ~ 1646] (better known in chanoyu as Hosokawa Sansai [細川三齋]) was in Korea as part of the first invasion of the continent (in 1592). The kama, furo, and mizusashi all feature matsu-gasa kan-tsuki [松笠鐶付], imitating the kan-tsuki on Rikyū’s second small unryū-gama.