#same with the pheasants and their enclosure

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Jingyi is dragging his slightly-older shufu a-zhan into trouble? Let's go and "liberate" some of grandma's red-bean buns, shufu! Let's go and bob around in lxc's hot springs like little dumplings! Clothes are for other baos! Cuddle ALL the bunnies! Pheasant-nap of one of lqr's flock and set it loose in the lanshi!

This is what led to both of them being stuck on gege duty with baby Jueying. When Jingyi complained, Lan Qiren informed him that he was four years old and thus had no business doing anything that would be unsafe to do around a crawling baby (at least indoors).

#asks#jingyi was distraught#no more eating buns till I'm sick shugong?!#lqr: well not unless you want your infant sister to follow your example...#ljy: no bringing fluffles of bunnies indoors to run wild?!#lqr: :| no because they could bite yingying#ljy: no bobbing in the hot spring? :(#lqr: NOT WITHOUT SUPERVISION#ljy was very upset to find out that he would get to see the bunnies in the rabbit field or not at all#same with the pheasants and their enclosure#and he doesn't get buns except at mealtimes!#how cruel >:(#meanwhile 7yo lwj was VERY relieved to find himself shufu-ing a baby who couldn't walk yet...#jingying at gusu summer school au#lan jingyi#lan wangji

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guppies

Guppies are popular freshwater aquarium fish. As with the pheasants we met in Chapter 3, the males are more brightly colored than the females, and aquarists have bred them to become even brighter. Endler studied wild guppies (Poecilia reticulata) living in mountain streams in Trinidad, Tobago and Venezuela. He noticed that local populations were strikingly different from each other. In some populations the adult males were rainbow-coloured, almost as bright as those bred in aquarium tanks. He surmised that their ancestors had been selected for their bright colours by female guppies, in the same manner as cock pheasants are selected by hens. In other areas the males were much drabber, although they were still brighter than the females. Like the females, though less so, they were well camouflaged against the gravelly bottoms of the streams in which they live. Endler showed, by elegant quantitative comparisons between many locations in Venezuela and Trinidad, that the streams where the males were less bright were also the streams where predation was heavy. In streams with only weak predation, males were more brightly coloured, with larger, gaudier spots, and more of them: here the males were free to evolve bright colours to appeal to females. The pressure from females on males to evolve bright colours was there all the time, in all the various separate populations, whether the local predators were pushing in the other direction strongly or weakly. As ever, evolution finds a compromise between selection pressures. What was interesting about the guppies is that Endler could actually see how the compromise varied in different streams. But he did much better than that. He went on to do experiments.

Suppose you wanted to set up the ideal experiment to demonstrate the evolution of camouflage: what would you do? Camouflaged animals resemble the background on which they are seen. Could you set up an experiment in which animals actually evolve, before your very eyes, to resemble a background that you have experimentally provided for them? Preferably two backgrounds, with a different population on each? The aim is to do something like the selection of two lines of maize plants for high and low oil content that we saw in Chapter 3. But in these experiments the selection will be done not by humans but by predators and by female guppies. The only thing that will separate the two experimental lines is the different backgrounds that we shall supply.

Take some animals of a camouflaged species, perhaps a species of insect, and assign them randomly to different cages (or enclosures, or ponds, whatever is suitable) which have differently coloured, or differently patterned, backgrounds. For example, you might give half the enclosures a green foresty background and the other half a reddish-brown, deserty background. Having put your animals in their green or brown enclosures, you'd then leave them to live and breed for as many generations as you have time for, after which you'd come back to see whether they had evolved to resemble their backgrounds, green or brown respectively. Of course, you only expect this result if you put predators in the enclosure too. So, let's put, say, a chameleon in. In all the enclosures? No, of course not. This is an experiment, remember; so you'd put a predator in half the green enclosures and half the red enclosures. The experiment would be to test the prediction that, in enclosures with a predator, the insects would evolve to become either green or brown - to become more similar to their background. But in the enclosures without a predator, they might if anything evolve to become more different from their background, to be conspicuous to females.

I have long nursed an ambition to do exactly this experiment with fruit flies (because their reproductive turnover time is so short) but, alas, I never got around to it. So I am especially delighted to say that this is exactly what John Endler did, not with insects but with guppies. Obviously he didn't use chameleons for predators, but instead chose a fish called the pike cichlid (pronounced 'sick lid'), Crenicichla alta, which is a dangerous predator of these guppies in the wild. Nor did he use green versus brown backgrounds - he opted for something more interesting than that. He noticed that guppies derive much of their camouflage from their spots, often quite large ones, whose patterning resembles the patterning of the gravelly bottoms of their native streams. Some streams have coarser, more pebbly gravel, others finer, more sandy gravel. Those were the two backgrounds he used, and you'll agree that the camouflage he was seeking was subtler and more interesting than my green versus brown.

Endler got a large greenhouse, to simulate the tropical world of the guppies, and set up ten ponds inside it. He put gravel on the bottom of all ten ponds, but five of them had coarse, pebbly gravel and the other five had finer, sandy gravel. You can see where this is going. The prediction is that, when exposed to strong predation, the guppies on the two backgrounds will diverge from each other over evolutionary time, each in the direction of matching its own background. Where predation is weak or non-existent, the prediction is that the males should tend in the direction of becoming more conspicuous, to appeal to females.

Instead of putting predators in half the ponds and no predators in the other half, again Endler did something more subtle. He had three levels of predation. Two ponds (one fine and one coarse gravel) had no predators at all. Four ponds (two fine and two coarse gravel) had the dangerous pike cichlid. In the remaining four ponds, Endler introduced another species of fish, Rivulus hartii, which, despite its English name, 'killifish' (actually that's quite irrelevant since it is named after a Mr Kille), is relatively harmless to guppies. It is a 'weak predator', whereas the pike cichlid is a strong predator. The 'weak predator' situation is a better control condition than no predators at all. This is because, as Endler explains, he was trying to simulate two natural conditions, and he knows of no natural streams that are totally free of predators: thus the comparison between strong and weak predation is a more natural comparison.

So, here's the set-up: guppies were assigned randomly to ten ponds, five with coarse gravel and five with fine gravel. All ten colonies of guppies were allowed to breed freely for six months with no predators. At this point the experiment proper began. Endler put one 'dangerous predator' into each of two coarse gravel ponds and two fine gravel ponds. He put six 'weak predators' (six rather than one, to give a closer approximation to the relative densities of the two kinds of fish in the wild) into each of two coarse gravel ponds and two fine gravel ponds. And the remaining two ponds just carried on as before, with no predators at all.

After the experiment had been running for five months, Endler took a census of all the ponds, and counted and measured the spots on all the guppies in all the ponds. Nine months later, that is, after fourteen months in all, he took another census, counting and measuring in the same way. And what of the results? They were spectacular, even after so short a time. Endler used various measures of the fishes' colour patterns, one of which was 'spots per fish'. When the guppies were first put into their ponds, before the predators were introduced, there was a very large range of spot numbers, because the fish had been gathered from a wide variety of streams, of widely varying predator content. During the six months before any predators were introduced, the mean number of spots per fish shot up. Presumably this was in response to selection by females. Then, at the point when the predators were introduced, there was a dramatic change. In the four ponds that had the dangerous predator, the mean number of spots plummeted. The difference was fully apparent at the five-month census, and the number of spots had declined even further by the fourteen-month census. But in the two ponds with no predators, and the four ponds with weak predation, the number of spots continued to increase. It reached a plateau as early as the five-month census, and stayed high for the fourteen-month census. With respect to spot number, weak predation seems to be pretty much the same as no predation, over-ruled by sexual selection by females who prefer lots of spots.

So much for spot number. Spot size tells an equally interesting story. In the presence of predators, whether weak or strong, coarse gravel promoted relatively larger spots, while fine gravel favoured relatively smaller spots. This is easily interpreted as spot size mimicking stone size. Fascinatingly, however, in the ponds where there were no predators at all, Endler found exactly the reverse. Fine gravel favoured large spots on male guppies, and coarse gravel favoured small spots. They are more conspicuous if they do not mimic the stones on their respective backgrounds, and that is good for attracting females. Neat!

Yes, neat. But that was in the lab. Could Endler get similar results in the wild? Yes. He went to a natural stream that contained the dangerous pike cichlids, in which the male guppies were all relatively inconspicuous. He caught guppies of both sexes and transplanted them to a tributary of the same stream that contained no guppies and no dangerous predators, although the weak predator killifish were present. He left them there to get on with living and breeding, and went away. Twenty-three months later, he returned and re-examined the guppies to see what had happened. Amazingly, after less than two years, the males had shifted noticeably in the direction of being more brightly coloured - pulled by females, no doubt, and freed to go there by the absence of dangerous predators. [...]

Nine years after Endler sampled his experimental stream with such spectacular results, Reznick and his colleagues revisited the place and sampled the descendants of Endler's experimental population yet again. The males were now very brightly coloured. The female-driven trend that Endler observed had continued, with a vengeance. And that wasn't all. You remember the silver foxes of Chapter 3, and how artificial selection for one characteristic (tameness) pulled along in its wake a whole cluster of others: changes in breeding season, in ears, tail, coat colour and other things? Well, a similar thing happened with the guppies, under natural selection.

Reznick and Endler had already noticed that when you compare guppies in predator-infested streams with guppies in streams with only weak predation, colour differences are only the tip of the iceberg. There is a whole cluster of other differences. Guppies from low-predation streams reach sexual maturity later than those from high-predation streams, and they are larger when they reach adulthood; they produce litters of young less frequently; and their litters are smaller, with larger offspring. When Reznick examined the descendants of Endler's guppies, his findings were almost too good to be true. The ones that had been freed to follow female-driven sexual selection rather than predator-driven selection for individual survival had not only become more brightly coloured: in all the other respects I have just listed, these fish had evolved the full cluster of other changes, to match those normally found in wild populations free from predators. The guppies matured at a later age than in predator-infested streams, they were larger, and they produced fewer and larger offspring. The balance had shifted towards the norm for predator-free pools, where sexual attractiveness takes priority. And it all happened staggeringly fast, by evolutionary standards. Later in the book we shall see that the evolutionary change witnessed by Endler and Reznick, driven purely by natural selection (strictly including sexual selection), raced ahead at a speed comparable to that achieved by artificial selection of domestic animals. It is a spectacular example of evolution before our very eyes.

— Richard Dawkins, The Greatest Show on Earth

1 note

·

View note

Text

Should I try and post more about my animals again. Hmmm. This has always been a very mixed blog but I've barely made an original post in a few years cause I just never feel like I have anything to say. Or the energy.

Coming up out of a few-month-long depressive episode and starting to feel joy about my hobbies again. Most of which revolve around my animals. I'm sure the depression will catch back up soon now that the sun is starting to disappear, but in the meantime... it's nice to feel a bit of excitement again.

I quit a very bad job back in March because I was pretty much one bad day away from killing myself. Like, I had plans. I was ready. My wife more or less forced me to quit for my own good. I had somehow saved up enough money to survive just fine without it and spent 6 weeks at home, catching up on projects, deep cleaning, and recovering. Then in May I got a job I thought I really wanted. I planned on staying long term. They said constantly I was doing a great job learning (it was a very hard job) but then did a 180 and fired me just before my 90 days, when I would've finally had health insurance.

Had a really bad breakdown over that, because at that point I didn't have money in savings and there was basically no jobs on indeed. I ended up having to go through a temp agency the next week to finally find a job. It's a boring factory job, but it pays the same as the hard job and it's so easy it crosses over into downright understimulating for parts of the day. I don't get benefits/ sick time/ holiday pay/ anything until I get actually signed on with the company, and I don't know when that will be, but I know I basically can't lose this job unless I skip work or come in late a bunch, which is not the kind of person I am, so I'm at least secure there. Now that I'm away from hard job and I've been at this job about a month, I'm actually glad I lost the other job. That job had so much pressure and stress and since I was the only girl in the department I was treated noticeably different (I believe that's half of why I was fired but I won't go there) but my current job is so simple. I spend at least half of every day marveling at the fact I'm getting paid to do such simple shit.

Anyway, yeah... hello adhd I was trying to talk about my animals.

We've been at this house 2.5 years now and finally starting to feel like the farm is getting to how we want it. We've got most of our birds pens up, except the breeding pen my wife wants to build for some of her chickens, but I finished the pheasant pens this spring that I started last year and the remodel of the duck/turkey pens.

We fenced in most of our property last year, and we finally got gates for the driveway last weekend so the horses and sheep can graze our yard and help keep the grass short.

When I was off work this spring I started working on deep cleaning the basement, where all my exotic animals stayed when our parasitic ex friends lived with us. The basement had a minor flood two years ago and still needs some remodeling and cleaning, but someday I plan to finish that and turn it *back* into an animal room. Though I plan to keep the tarantulas and geckos upstairs in their current room and set up all my snakes in the downstairs room. I have a crazy vision for that room that's gonna take time and money but I'm so excited to get there one day. I hate racks and I'm planning on pvc enclosures for all my snakes. It's gonna be expensive but I'm so fucking excited for it.

We're hoping to pay off the stupid PMI to drop our monthly house payment by the end of next year. And the escrow stuff was messed up by the township so our payment is currently 1700/month instead of the 1300 it was, and they refuse to change it even though it was a clerical error on their end, but hopefully we'll get at least some of that wasted money back next June when they reassess and our payment will go back down. 🤞 without that fuck up and the PMI, we could maybe get lucky and have, like, a 1000/month payment instead of 1700. That money would be so useful for other shit.

How did I get here. Where was I going with that. Hmm.

Oh yeah because money and animals lol

Anyway I don't know why I'm typing this and nobody is gonna read it anyway but maybe I'll actually try and post some animal pics soon.

#personaljournalposts#i simply do not know how to write a short post ffs#I'm currently hyper focusing on my snakes and it's a little obvious#but the chickens ducks turkey and pheasants have kept us pretty busy all season too#our herd of sheep has grown to 4. which doesn't seem like much but hopefully there will be more babies next spring#kinda hoping our horse numbers drop from 2 to 1 but that's just because I'm not getting along with our friend's horse who stays here...#... and she is planning on moving her sometime in the near future because she just moved an hour away#hello rambling again ill stop

0 notes

Photo

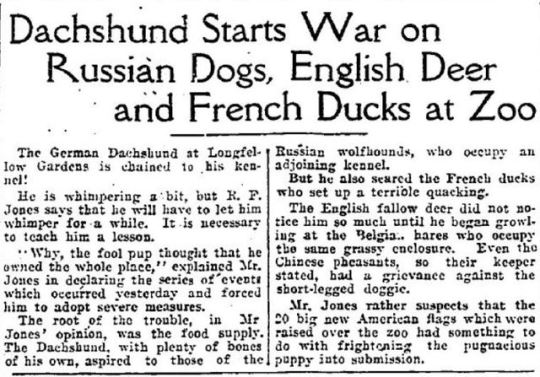

The German Dachshund at Longfellow Gardens is chained to his kennel!

He is whimpering a bit, but R.F. Jones says that he will have to let him whimper for a while. It is necessary to teach him a lesson.

“Why, the fool pup thought that he owned the whole place,” explained Mr. Jones in declaring the series of events which occurred yesterday and forced him to adopt severe measures.

The root of the trouble, in Mr. Jones’ opinion, was the food supply. The Dachshund, with plenty of bones of his own, aspired to those of the Russian wolfhounds, who occupy an adjoining kennel.

But he also scared the French ducks who set up a terrible quacking.

The English fallow deer did not notice him so much until he began growling at the Belgian hares who occupy the same grassy enclosure. Even the Chinese pheasants, so their keeper stated, had a grievance against the short-legged doggie.

Mr. Jones rather suspects that the 20 big new American flags which were raised over the zoo had something to do with frightening the pugnacious puppy into submission.

(newspaper article, published in the May 13th, 1917 edition of the Minneapolis Tribune via, images via)

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Click the link above for the original post I can’t art, but sometimes I write. This was actually written the second week of July but when it’s writing thrown into the same ring as art there’s usually not much competition. But I needed some Beej + birds.

SFW. Soft. Short and sweet.

Aviary

Dogs didn’t like him. You’d have thought cats would, having read so many books and seen so many movies that insisted cats could cross between planes and were privy to so many secrets . . . but cats hated him even more.

Beej tried to hide how upset it made him with lots of bluster and snarky remarks, but you could tell he did kind of like animals. He always looked wistful when a dog came up to you and you got to pat its head but it ducked and hurried away when he got near. Worse was when the dog would lift a lip and show teeth with its hackles raised, a clear warning for the ghost to back off. It didn’t physically hurt if he was bitten; it just seemed to make him sad. If he noticed you noticing his disappointment, he made a joke and brushed it off like he didn’t care. The more you thought about it, the more you wondered. Maybe it was just alpha predators that didn’t like him. Maybe it was just mammals? Like he gave off a scent or something, or they just knew he was a dead guy. Maybe it needed to be some other kind of animal, with a less acute sense of smell. He always had random lizards and snakes tucked away in his pockets, and once there was a mouse he pulled out of his suit, but they always seemed more interested in escaping than hanging around.

Only the mouse was warm-blooded too, and you knew how much he adored warmth. When the possible solution came to you, you could have smacked your head with how simple it could be.

“The what?” Beetlejuice griped. “The where? An aviary?!”

You repeated yes, the aviary, just as you’d had multiple times already. “I don’t want to look at dumb birds! Stupid little sparrows, dumb pigeons, stinky vultures always hangin’ around looking for a free meal--”

He ticked his complaints off on his fingers. You steadfastly ignored what seemed like mostly made up excuses, although you were interested in knowing more about vultures that may or may not have tried to eat some of him. If he was a ghost, he’d been alive once, right? That could add a little more to his backstory.

You told him you didn’t think the place had any vultures, paid for one ticket. He followed morosely.

Once inside, however, in the immersive exhibits with free-flying birds, Beej was enraptured. He pointed one bird after another to you, exclaiming over each of them. “Lookit that one! Its bill is spoon-shaped!” “What the heck is that? A weird peacock? Wait, it’s a Great Argus Pheasant! It’s tail is so long!” “The penguins have bands on their upper wings with their names on them!” “Is that a bat? Why are there bats in an aviary?” Since he’d mentioned ‘dumb pigeons’, you made sure to point out the Victoria Crowned Pigeons. Much larger than their more well-known city-dwelling cousins, their fancy head dresses made him grin. Since he was largely unseen and therefore unsupervised by the employees of the aviary, Beej was able to do what was not allowed of the other visitors and touch the birds. Habituated to people, the birds were calm. Not habituated to ghosts, they were even calmer, and Beej sat cross-legged on a walkway with the largest of the Crown Pigeon flock in his lap. Stroking its dusty blue feathers, he spoke to it, but his voice was too quiet for you to hear exactly what he was telling it.

He may have sat there all day, but there was still one more room you wanted to show him, so reluctantly he let the bird go. You led him by his wrist to the lorikeet enclosure.

The smallish, brightly colored parrots shrieked in a cacophony of happy noise. They dive-bombed past you from branch to branch. One landed on your shoulder and was gently removed by the employee, who offered the bird to you to hold on your hand. You did. The bird was obviously hoping for a treat even though it was passed their feeding time. Beetlejuice examined the bird up close, and the bird kept an eye on him too. Eventually it flew off. He tracked it with his eyes. Although the noise didn’t bother him, it was annoying to you after a bit so you exited their enclosure. The ghost tagged along with a wide grin. The grin didn’t leave his face. You walked back through the exhibit with the large pigeons, and you sat on a bench as he held the same bird--you thought; they all kind of looked the same--again in his lap. Finally, however, it was time to leave. Beetlejuice followed you with his hands in his pockets. Uncharacteristically, he was quiet. “Did you like it?” He nodded. “Yes.” There was no continuation after the one syllable answer. “I was thinking that maybe I could get a bird.” That pulled him out of his thoughts. “Get a bird? To own? A lorikeet?!” You laughed. “No, I don’t think I could handle a lorikeet. Too noisy! I was thinking maybe a chicken or two. Hens, not roosters. You could hold them like that big pigeon.” “You think they’d let me?” he asked quietly. “Of course they would! They’re domesticated, not tamed, so they’d probably be even more amical about it. We could maybe get some chicks, so we can raise them.” That large smile returned, and you were glad to have stumbled on a solution to his pet problem.

fin

sleeby beej from this post strikes out on his own

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

From sharks to chimps to moon bears: tales of a supervet

Romain Pizzi, the vet who pioneered keyhole surgery for animals, has operated on sharks, chimps even a moon bear

In 2012, the conservation charity Free the Bears approached Romain Pizzi, one of the most innovative wildlife surgeons in Europe, with an unusual patient. A specialist in laparoscopic (keyhole) surgery – until recently rare in veterinary medicine – Pizzi has operated on giraffes and tarantulas, penguins and baboons, giant tortoises and at least one shark, and maintains a reputation for taking on cases others won’t. If you’re in possession of a tiger with gallstones, or a suspiciously sickly beaver, you call Pizzi. As Matt Hunt, CEO of Free the Bears says, “We have other vets who are incredibly talented. But Romain is one of a kind.”

The patient in question was a three-year-old female Asiatic black bear, also known as a moon bear, called Champa. Moon bears, poached for their bile and bodyparts, are classified as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Rescued as a cub and brought to a Free the Bears sanctuary in Laos, Champa had a deformed skull and impaired vision. While other bears would socialise, she would mope around her enclosure, head down, seemingly in agony. Pizzi suspected she had hydrocephalus, a rare condition in which excess cerebrospinal fluid builds up in the skull, causing brain damage.

Catching a red-eye: Romain Pizzi is based in Edinburgh where he treats rockhopper penguins, but flies around the world for operations. Photograph: Tim Flach

“Anywhere else in the world, the recommendation would have been to euthanise her,” Hunt says. But in Laos, which has a Buddhist tradition and strict conservation laws shaped in part as a response to the bear-bile trade, euthanasia is forbidden. So Hunt asked Pizzi for an alternative solution. “We started talking about the possibility of surgery,” Hunt says.

Veterinary surgeons operate under unique constraints. There’s scale: it’s hard to fit an elephant in an MRI machine. There’s temperament: you don’t want a tiger to wake up on the operating table. And there are financial pressures. A cutting-edge surgery on a domestic pet can cost tens of thousands of pounds. By contrast, wildlife charities can be forced to function on small budgets. And surgeries are often performed in the field, at sanctuaries and wildlife reserves with few of the average zoo luxuries, such as sterile theatres and reliable electricity.

In Champa’s case, even confirming the diagnosis proved impossible. “There’s no money in Laos,” Pizzi says. “There’s no MRI scanner in the whole country. They don’t even do the operation on humans.” The nearest human hospital refused to admit an animal for an x-ray. What’s more, no vet had ever attempted to perform brain surgery on a bear before. Pizzi went on undeterred. Without an MRI, visualising Champa’s brain in advance was challenging. So he contacted the National Museum of Scotland, which keeps an archive of mammal skeletons for scientific study, and borrowed the skull of a young female moon bear, which he x-rayed to help create a digital replica – a kind of map. “You find a different way,” he says.

Bearing up: Champa the moon bear’s brain surgery. Photograph: Matt Hunt/Free The Bears

Before long, Pizzi turned to Jonathan Cracknell, a veterinary anaesthetist and regular collaborator, to assist – “I’m his gas man,” Cracknell says. Pizzi and Donna Brown, head veterinary nurse at Edinburgh Zoo, set about sourcing supplies for a six-hour operation. Then, in February 2013, having prepared as much as possible, they packed up their equipment and boarded a plane to Laos.

Pizzi has always had an affinity for small and fragile things. Growing up in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, he wanted to be a paediatrician. Later, when he was a teenage student at Pretoria Boys High School (alumni include Elon Musk), he came across a dove that had fallen from its nest. “I nursed it back to health and then released it,” he says. “It would visit for weeks afterwards.”

He studied veterinary science at the University of Pretoria and, after graduating, came to the UK in 1999 to undertake a masters at London Zoo. He was stunned by how far veterinary surgery techniques lagged behind human medicine, and quickly developed an interest in laparoscopy, in which surgical tools are passed into the body through a small tube. “I think there were two of us who started doing it in the UK around the same time,” says Pizzi. Today, he lectures veterinary students on the technique. “He has an incredible thirst for knowledge and an eye for detail, and is always looking to apply or pioneer new techniques in our field,” says Nic Masters, head of veterinary services at London Zoo.

In June last year I visited Pizzi at work at the National Wildlife Rescue Centre in Fishcross, about an hour’s drive northwest of Edinburgh. Pizzi splits his time between running the veterinary service here, working at Edinburgh Zoo and travelling for surgeries. Since he joined in 2010, the centre has grown into one of the largest wildlife rehabilitation hubs in the UK. Every day, members of the public telephone to report injured wildlife. Drivers are dispatched to collect the animals and, late in the afternoon, their vans roll up to the centre and unload their casualties. The Rescue Centre treated 9,300 animals in 2016. This year, Pizzi expects that number to pass 10,000.

Through the keyhole: Pizzi performs laparoscopic surgery on a female jaguar. Photograph: Romain Pizzi

A series of low brick buildings and enclosures, the centre is divided into four sections: small mammals; large mammals; seals and waterfowl; and birds. The corridors are thick with rasping shrieks and caws. The air is acrid. Whiteboards list the species currently requiring Pizzi’s attention. Today, “birds” alone lists woodpeckers, crossbills, jackdaws, crows, robins, thrushes, blue tits and great tits, goldfinches, bullfinches, ospreys, lapwings, oystercatchers, kestrels, a pheasant and several varieties of owl.

Pizzi’s case load has helped him develop new approaches. When he started working at the centre, he would stay late at night, practising on cadavers, familiarising himself with anatomies, developing new techniques. Now his desk is littered with GoPro cameras – used for teaching – and a Philips electric razor to remove fur. Nearby is a portable x-ray and an ultrasound. He’s seen every affliction: bacteria, broken bones, even a rare case of balloon syndrome, in which a damaged glottis caused a hedgehog to inflate to the size of a beach ball.

When I visit, Pizzi has plenty to do. A hedgehog has an infection, so Pizzi prescribes Betamox, an antibiotic, and an antifungal for ringworm. A rabbit with a suspected spinal fracture needs an x-ray. And there’s an exploratory laparoscopy to perform on a beaver called Justin. (“It took me a week to figure out why,” Pizzi says. “Justin. Justin Beaver.”) His patient roster is broad: from chimpanzees to tarantulas, but it saddens him that the endangered species – lions, rhinos, bears – get all the attention when there are animals threatened here in the UK. “I never want to just be doing these big operations the media likes,” he says. “I probably make more of a difference here.”

In depth knowledge: Pizzi examines an angel shark. Photograph: Romain Pizzi

Champa’s surgery started poorly. Keyhole surgery requires the use of an insufflator, which uses carbon dioxide to inflate the body cavity wide enough to accommodate surgical implements. The problem: when Pizzi and Cracknell arrived at the rescue centre in Laos, they couldn’t find a carbon dioxide cylinder compatible with the machine.

The centre itself is in a national park near the city of Luang Prabang, with few amenities. The answer finally came from an unlikely source. “There was one bar that does draft beer. Once a week they had a keg come up from Luang Prabang,” Pizzi says. “They said, OK, we’ll have no draft beer for the next five days.” They donated their CO2, which Pizzi connected with some gas piping and hose clamps.

Anaesthesia proved tricky. “She went down on the sedative and stopped breathing,” says Hunt. The room was cramped and humid, made warmer by the presence of a BBC documentary crew who had come to film the procedure. Sweat dripped on to the floor tiles. As Pizzi prepared to drill into the skull – using a Dremel woodworking tool – everyone held their breath. It was indeed hydrocephalus. Pizzi was able to fit a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, a tube that sits in the brain cavity and funnels excess fluid down into the abdomen, where it is absorbed by the body. However, when Pizzi started to fit the tube, a minor disaster struck: the sanctuary’s electricity supply – already stretched by the film crew’s lights – blew. “The electrics arced and fused,” says Cracknell. The insufflator was fried.

Animal magic: chimpanzee Ruma and her baby. Photograph: Tim Flach

But Pizzi was prepared. “There’s so many things that can go wrong,” he says. “I try to build in a redundancy for all the main equipment.” He produced his favourite piece of frugal innovation: an inflatable mattress pump. “You run that into the abdomen in short bursts and it will puff up with air,” says Pizzi. “Not ideal, but it’s OK.”

“He comes up with amazing things,” says Cracknell. “There are some surgeries where, halfway through, you might think, ‘I’ve bitten off more than I can chew.’ With Romain, I’ve never had one go wrong.” The surgery took six hours. The next day, he and Hunt went to Champa’s den, where she was starting to wake up. “For many years she’d been in pain, she’d been blind, she never looked up,” says Hunt. “And we called her, and she looked up and fixed us with her eyes. It was quite amazing.”

Whenever Pizzi treats endangered species, there’s always a great awareness of what its death means. Pizzi has operated on the Socorro dove, a beautiful brown bird native to the Revillagigedo Islands off the west coast of Mexico, now extinct in the wild. And he keeps a photo of himself with the last-known Partula Faba, or Captain Cook’s bean snail, named because it was first discovered on Cook’s expedition in 1769. It died at Edinburgh Zoo in 2016, its species with it.

Loving touch: Romain Pizzi preparing for surgery. Photograph: Tim Flach/Wired © The Condé Nast Publications Ltd

Later this year, Pizzi will fly back to Laos to operate on Champa again. It’s been four years, but her health has deteriorated. Shunts can become blocked, pressure builds in the brain. Pizzi will operate, check the shunts and replace them if needed. But maybe that’s not the answer. Maybe it would be better if Champa died. She remains brain-damaged. That’s the question veterinarians have to deal with. How much suffering is enough? And who are we keeping the animal alive for? If we wanted to save our wildlife we’d be preserving their habitats, not burning down forests, polluting their environments, hunting them into extinction.

“Conservation – it’s such a meaningless word,” Pizzi says later, over dinner. “Keeping animals and breeding them in captivity, in some people’s minds that’s conservation, because you’re not taking them from the wild. I don’t think that’s genuine. When people come into the zoo, they’re not going to save the orangutans. They just want a good day out.”

“In veterinary medicine, people say ‘unnecessary suffering’,” Pizzi continues. “Which means that there is some suffering we’re OK with.” We hate to see zoo animals suffer, but care little about the cattle slaughtered for agriculture. (Pizzi is vegetarian.) We fret about mass extinction, but not enough to change our habits. Therein lies the tragedy of Pizzi’s work: he can develop new ways to save wildlife, but even if he saves 10,000 animals this year, it’s just a drop in the rapidly acidifying ocean.

Fangs a lot: removing a diseased gall bladder from a moon bear. Photograph: Romain Pizzi

He thinks about that a lot. But, then, he also thinks about the case of a white-tailed sea eagle he once treated. It had a broken wing and one leg. “It’s easier to kill the bird, and maybe it’s the right thing,” Pizzi says. The bone was protruding through the skin. But the bird had spirit; even then, it tried to fly. “Do I go in and chop a bunch of the dead bone out? How much is too much intervention?” He ended up setting the bones and released it after three months with a tracking implant. Its flight always looked a bit off; to this day he wonders if he should have done more. But the eagle lived, and it flew – until it died, four years later, of natural causes.

This is an edited version of a piece that originally ran in Wired magazine. Oliver Franklin-Wallis/Wired © The Condé Nast Publications Ltd

from All Of Beer http://allofbeer.com/from-sharks-to-chimps-to-moon-bears-tales-of-a-supervet/

0 notes

Text

Fences: Keeping Chickens In & Predators Out

Way back when I was ready to purchase my first house, high on my list of must-haves was a place to raise chickens. To make sure the property was zoned for chickens, I looked for a place that either had chickens or had near neighbors with chickens. What swayed me to select the house I finally purchased was that it was fenced, cross-fenced, and loaded with chickens. The chickens, in fact, came with the property. How much better could it get?

Well, it did get better because the fences were all six-foot chain link. In the 11 years that I lived there, I lost few chickens. Of those, one bantam hen was taken away by a hawk (that I know of for sure because I saw it happen) and the others were mostly chicks that popped through the fence and got carried off by a neighbor’s cat. My biggest regret in leaving that property was giving up the chain link fence.

I now live on a farm where we enjoy the wildlife as much as we enjoy our poultry. Trouble is, the wildlife have as much interest in poultry as we do. Our chicken yard (pasture, really) is fairly large, so the cost of enclosing it with chain link would be prohibitive. For years we fenced our poultry with the same high tensile, smooth wire, electric fence that contains our four-legged livestock. It does a good job of keeping out the larger predators, but does not keep out the smaller chicken eaters, and certainly does not keep the chickens in. So occasionally we lose a bird that wanders into the orchard for lunch and meets a fox with the same idea.

Last year, I realized my dream of once again having a yard protected by chain link. It’s only a smallish yard, designed for housing setting hens, and growing birds that are more vulnerable to predators than mature birds. Unlike that long-ago chain link fence, this one has an electrified scare wire running along the outside bottom. The idea is to zap any animal that tries to either dig under or climb over.

Barring the expense of chain link, the (next) best kind of fence for chickens is wire mesh with fairly small openings that neither chickens nor predators can get through. Of the many kinds of wire mesh available, one that works well for chickens and is relatively low on the cost scale is the yard-and-garden fence with one-inch spaces toward the bottom and wider spaces toward the top. The small openings at the bottom keep poultry from slipping out and small predators from getting in. The fence should be at least four feet high; higher if you keep a lightweight breed that likes to fly. Bantams and young chickens of all breeds are especially fond of flying.

Updated Composting Guide: Learn to compost chicken manure!

Avoid common composting mistakes with this Free Guide. Successfully make your own garden gold with help from our experts. YES! I want this Free Report »

A common type of wire mesh fence is poultry netting, also called hexagonal netting, hex net, or hex wire. It consists of thin wire, twisted and woven together into a series of hexagons, giving it a honeycomb appearance. The result is lightweight fencing that keeps chickens in but will not deter motivated predators from breaking through with brute strength. I have used it to create breeder runs, although those enclosures were situated inside that long-ago chain link fence.

Hex net comes in mesh sizes ranging from 1/2″ to 2″. The smaller the mesh, the stronger the fence. The smallest grid, called aviary netting, is made from 22-gauge wire and is used to pen quail and other small birds, to house chicks, and to prevent small wild birds from stealing poultry feed.

One-inch mesh, woven from 18-gauge wire, is commonly called chicken wire. It’s used to pen chickens, pigeons, pheasants, turkey poults, ducks, and goslings. Rolls range in length from 25′ to 150′, in height from 12″ to 72″. The shortest wire is used to reinforce the lower portion of a woven wire or rail fence to keep little critters from slipping in or out.

So-called turkey netting, made of 20-gauge wire, has 2″ mesh and is used for penning turkeys, peafowl, and geese. Heights range from 18″ to 72″, length from 25′ to 150′. Mesh this large is difficult to stretch properly. For a tall fence, therefore, many fencers run two narrow rolls, one above the other. Either staple the butted edges to a rail or fasten them together with cage making rings crimped with a clincher tool designed for the purpose (available at feed stores and small stock suppliers).

A less common variation, called rabbit netting, has 1″ mesh at the bottom and 2″ mesh toward the top. It comes in 25′ rolls, is 28″ high, and may be used to pen chicks and poults (baby turkeys).

Woven-wire fencing is ideal for chicken yards; it is sturdy enough to protect against predators, is finely meshed to keep chickens from slipping outside, and offers a great view of the chicken yard culture. Courtesy of Barnyard in your Backyard, edited by Gail Damerow.

Unless you treat hex wire with great care, don’t expect it to last more than about five years. Options in protective coating are galvanizing and vinyl. Some brands are galvanized before being woven, some afterward. The former is cheaper but should be used only under cover, since it rusts rapidly in open weather. Plastic-coated wire is a bit more rust resistant and some people find the colors more attractive than plain metal.

Hex net is relatively easy to put up, although it tears readily, and slight tears grow into big holes. Netting also tends to sag. For a poultry run, erect a stout framework of closely spaced wood posts with a top rail for stapling and a stout baseboard both for stapling and to deter burrowing; make sure no dips at soil level leave gaps for sneaky critters to slip under. To keep the wire taut, taller fences need a rail in the middle as well. Hand stretch the mesh by pulling on the tension wires — the wires woven in and out at the top and bottom of the netting. Taller netting has additional intermediate tension wires. To avoid snagging skin and clothing, especially around gates, fold under the cut ends before stapling them down.

Digging a trench and burying the bottom portion of a net fence deters burrowing. An alternative is to use apron fencing, also called beagle netting, consisting of hex wire with an apron hinged to the bottom. The apron consists of 1-1/2″ grid, 17-gauge hexagonal netting, 12″ wide and is designed to keep raccoons and foxes from burrowing into poultry yards.

Set posts 6′ to 8′ apart. Cut and lift the sod along the outside of the fenceline. Install the fence with the apron portion spread horizontally along the ground, and replace the sod on top. The apron will get matted into the grass’s roots to create a barrier that discourages digging.

You can use this concept to create your own apron fence with any 12″ wide hex wire, clipped or lashed to the bottom of a hex net fence. Whether you buy apron fencing or devise your own, the chief disadvantage is that soil moisture causes rapid rusting and the apron will have to be replaced every couple of years. Unless the wire is vinyl coated, brushing it with roofing tar will slow rusting.

A common type of wire mesh fence is poultry netting, also called hexagonal netting, hex net, or hex wire. It consists of thin wire, twisted and woven together into a series of hexagons, giving it a honeycomb appearance. The result is lightweight fencing that keeps chickens in, but will not deter motivated predators from breaking through with brute strength.

To further protect your chickens against climbing predators, string electrified wire along the top and outside bottom of your fence. The top wire might be strung on T-post toppers, while the outside bottom wire should be strung on offset insulators. The advantage to using wire mesh with electrified scare wires is that you have both a physical barrier and a psychological barrier. Should the psychological barrier fail (the power goes off) you still have the physical barrier.

An all-electric net fence sounds great in principle, but I have personally found that it wasn’t the best fencing product for my needs. It must be constantly electrified; if you live in an area prone to power outages you must use a battery or solar operated energizer and make certain it’s always fully functional. Chickens can get tangled in the polywire net and get electrocuted (tearing the net in the process). Other issues include difficulty keeping the net taut, problems getting line posts into rocky soil or drought-ridden clay, and the inconvenience of corner guy wires.

A gate without a sill eventually develops ruts underneath that let birds out and predators in. Photo by Gail Damerow.

No matter how secure your fence is, it’s only as secure as your gates. When we had our chain link poultry run commercially installed, we had to deal with predator-size gaps at the sides and bottoms of the gates. Even when a gate is initially installed close enough to the ground, traffic from walking, wheelbarrows, mowers, and so forth eventually wears grooves under the gate. Installing a sill will solve that problem. Sink a pressure-treated 4″ by 4″ under each walk-through gate and a 6″ by 6″ under a drive-through gate, or pour a reinforced concrete sill of similar size. This small investment prevents soil compression from creating ruts beneath your gates — helping keep your birds in and predators out.

Burying the bottom portion of a net fence deters burrowing. An alternative is to use apron fencing, consisting of hex wire with an apron hinged to the bottom. The hinged 12″ apron prevents animals from burrowing under the fence, keeping predators out. Apron fencing available from, and drawing courtesy of, Louis E. Page, Inc.: www.louispage.com; phone: (800) 225-0508.

Originally published in the April/May 2008 issue of Backyard Poultry magazine and regularly vetted for accuracy.

Fences: Keeping Chickens In & Predators Out was originally posted by All About Chickens

0 notes

Text

Foods the Romans brought to Britain

by Cindy Tomamichel The Roman Empire spanned a great deal of the known world in ancient times, acting as a conduit for the spread of Roman culture. After the invasion and occupation of AD 43-410, Britain would never be the same. For its people and the environment, the Romans brought new ideas and foods, many of which have become staples of culinary tradition. There are a variety of information sources by which a picture of the foods of Roman Britain may be reconstructed. There is the actual foodstuff itself, where food such as grains, nuts and bones may be preserved by charring or carbonisation such as during a fire. Preservation by waterlogging occurs within peat bogs and estuaries. Fossilised remnants may also be found in latrines and rubbish heaps, where minerals such as calcium have replaced the structure. Food was also buried in containers in the burial sites of wealthier individuals. Shrine offerings are also another source of food evidence. Food containers may also carry the imprint of their contents. Other sources include import and export evidence, such as amphorae for wine, oil or garum. Some written sources exist, even for such things as shopping lists, for instance the Vindolanda tablets "... bruised beans, two modii, twenty chickens, a hundred apples, if you can find nice ones, a hundred or two hundred eggs, if they are for sale there at a fair price. ... 8 sextarii of fish-sauce ... a modius of olives ... To ... slave of Verecundus." There is some evidence of Roman foods being imported to Britain well before the invasion. However, the invasion created multiple avenues of demand for Roman foods, which expanded the importation significantly. The Roman army was a major consumer, but also the desire to be seen as Roman saw a rise in demand for exotic imports. What in the late Iron Age was a trickle, soon turned to a flood of new foods available during the occupation. Romans also brought food related ideas. Firstly there was a need to produce food in Britain on the scale required to supply the army. This need, coupled with the Roman habits of building roads and towns soon changed the face of agriculture. From small holdings growing mostly for personal consumption, it changed to larger farms specialising in growing enough of a product for market. The spread of new foods worked a gradual path out from the towns to the surrounding countryside. In this way many new foods became established. New fruits and nuts included apple, cherry, plum, walnut, mulberries, medlars, and chestnuts. New vegetables were grown such as carrots, beets, garlic, onions, shallots, leeks, cabbages, peas, celery, turnips, radishes, and asparagus. Herbs were both medicinal and for cooking and teas, including poppy, black mustard, rosemary, thyme, garlic, bay, basil, borage and savoury mint. All these established and stayed popular even after the Romans left. Other foods were popular only during the occupation, or just didn't establish well, such as grapes, figs, pine nuts and olives. Another way in which plants may arrive is by stealth. The weed seeds are harvested and are within a bag of seed grain, or they are planted and the environment suits them too well and they escape and naturalise. Plants like this include ground elder, white mustard, alexanders, stinging nettles, greater celandine, and fennel. Grains play a major part in diet and also part of the stability of society. A poor harvest would mean cultural unrest, particularly if the invaders were seen to be consuming large amounts. Grains already in Britain were various types of wheat, barley and oats. With the Romans came both an increased demand and new technology for ploughing and agricultural tools. They also introduced rye, millet and spelt. With the development of a closed field system, cattle could be alternated with crops such as grains, pulses and vegetables, increasing productivity.

Baking ovens are a common feature of Roman fortifications. This is a loaf of bread from a bakery in Pompeii. (source: http://www.pompeii.org.uk/m.php/museo-pistrinum-di-soterico-pompei-it-117-m.htm)

Part of many affluent Roman households was a garden, and perhaps this was the start of the English love of gardens which has spread with them all over the world. A typical house layout had a central courtyard garden, and here decorative plants such as box, foxgloves, mulberries, lilies, violets, pansies and roses would have been grown.

Part of a household might have included animal husbandry areas. For those longing for a taste of home, a snail farm or "cochlea", would have been established, where imported Roman snails were raised and fattened. They were fed on milk and oats or spelt to purge and fatten them, then cooked in wine, with garum or garlic. Roman snails are still to be found in the UK. Hare gardens with semi domesticated rabbits also existed for fur, hides and supplies of meat. They also built enclosures to keep deer, as well as pigeon enclosures and kept chickens and guinea fowl.

Edible Snail - photo credit Fred Dawson via Visual Hunt /CC-BY-ND

Britain was already exporting beef before the invasion, and goats, sheep, chickens, pigs and deer were also being eaten. Pigeons, quail, geese, pheasant and guinea fowl were likely imported with the Romans. Ham in brine and bacon with their good keeping qualities were important for soldiers on the march.

Amongst the many cultural changes the Romans brought was the change in eating habits. While in the more remote rural areas people probably continued eating stews, roast meat and porridges, in the towns more people adopted Roman dining habits. These are familiar to us today as the three meal arrangement, with breakfast being quite small, a moderate lunch and a larger dinner as evening was for entertaining. Fast food was also a Roman invention, with many small bakeries and food places available for those who could not cook at home, serving things like kebabs and burgers. Bath houses were also popular social hubs were snacks could be purchased.

However diet varied with social status, location and job. Many remote Britons would have continued eating their normal food, perhaps adding some new vegetables, herbs or grains to the mix. The elite would be the major consumers of the imported foods such as wines from Gaul (France), dried dates and olives.

The soldiers had to buy their own food, and had a routine for doing so. They often had their own bread ovens, herds of cows, pigs and managed their own purchase of grains and vegetables. A soldier's diet was also often supplemented by food sent from home, or by hunting local animals such as boar and deer.

Imported food consisted of things that would not grow or was not available in sufficient quantities. This included dates, almonds, olives and olive oil, wine, pine cones and kernels, fermented fish sauce (liquamen or garum), pepper, ginger and cinnamon.

After the Romans left Britain in AD 410, many aspects of their culture vanished. However, the hardier or more popular of the introduced plants and animals survived, becoming an integral part of the landscape.

Recipes

The main reference for Roman food is the cookbook of Apicius, a Roman epicure of around AD 100. The book is full of recipes for main meals, and often has several variations on a dish or ingredient. While many of the ingredients are probably not to today's tastes, many of the casserole and vegetable dishes sound interesting. Unfortunately none of the bread recipes he probably had are included.

Milk Fed Snails (Cochleas lacte pastas)–Apicius

After being purged and cleaned, the snails can be fried in oil and served with a wine sauce. Or they could be fried, then made into a soup with broth, adding pepper and cumin.

Vegetable and Brain Pudding (Patina frisilis)- Apicius

Take cooked and mashed vegetables and brains and mash to a fine paste. Add eggs, broth, and wine and place in an oiled baking dish. Bake and sprinkle with pepper when done.

Libum - Serves 2 (A type of cheesecake)

10 oz ricotta cheese. 1 egg. 21/2 oz plain flour. Runny honey.

Beat the cheese with the egg and add the sieved flour very slowly and gently. Flour your hands and pat mixture into a ball and place it on a bay leaf on a baking tray. Place in moderate oven (180C/400ºF) until set and slightly risen. Place cake on serving plate and score the top with a cross. Pour plenty of warmed runny honey over the cross and serve immediately. This is similar to a Greek cheesecake, which uses cottage cheese instead of ricotta. (Source: Sally Grainger The Classical Cookbook, published by British Museum Press.)

(Note: a variety of academic and website reference sources were used for this article, please contact the author if details are required.)

~~~~~~~~~~

Cindy Tomamichel is a writer of action adventure romance novels, spanning time travel, sci fi, fantasy, paranormal, and sword and sorcery genres. They all have something in common – swordfights! The heroines don't wait to be rescued, and the heroes earn that title the hard way.

Her first book, Druid's Portal: The First Journey will be out with Soul Mate Publishing in 2017. On Amazon May 17th. An action adventure time travel with a touch of romance set in Roman Britain around Hadrian's Wall.

A portal closed for 2,000 years.

An ancient religion twisted by modern greed.

A love that crosses the centuries.

Contact Cindy on Website: www.cindytomamichel.com Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CindyTomamichelAuthor/ Twitter: https://twitter.com/CindyTomamichel Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/16194822.Cindy_Tomamichel Google+: https://plus.google.com/+CindyTomamichel

Hat Tip To: English Historical Fiction Authors

0 notes

Note

Yeah depends on the animals. Our zoo will house some like animals together especially if they're working on a new enclosures. Capibara with beavers for example. Or cavi with Guinea pigs. Ground hogs with meircats. Different bird species that are part of the same catagoies like pheasants and peacocks. Or all the big cats share an indoor building but have walls to separate them. So yes it's common practice given the animals aren't vastly different, can harm eachother or are straight up predator and prey.

I know this probably isn't in your field but idk who to ask. I'm watching a show about a zoo on Animal Planet where they're housing different species together. Is that normal in a zoo? I don't think I've ever heard of it before.

Depends on the species. A lot of zoos will house multiple compatible species in an enclosure. I assume it’s a cost and space saving measure, or it could even be enrichment for the animals.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Post has been published on In de hemel is wél bier !

New Post has been published on http://bit.ly/2oAEDFY

Where do animals go when it storms?

Weather can be a real threat to big game animals. These antelope were killed in a hail storm in the Great Basin region of Wyoming in June of 2016. Animals that live in wide open spaces are vulnerable to extreme weather situation.

Spring time is always the times for storms in Nebraska. A young friend of mine asked me this question at church recently: Where do animals go when it storms?” I thought it was a pretty good question from an eight year old.

The answer is the same as it is for people. We seek shelter wherever we can find it, so do animals. However, animals can’t always find the “best” cover for all types of weather. There are all kinds of examples of animals/wildlife being killed by storms.

Back in February of 2007, 18 whooping cranes were being kept in an enclosure at the Chassahowitzka National Wildlife Refuge near Crystal River, Florida. Even though this was a man-made “protected” facility, a very violent storm moved through the area and killed 17 of these rare birds.

In one of the worst cases on record, hunting was all but banned in parts of Austria in October of 2009 after hail killed an estimated 90 percent of the wild game in the region. Tennis ball-sized hailstones were documented. Hundreds of deer were discovered either dead or so badly injured they had to be put down by wildlife officials. In the country’s rural Salzburg province, 90 percent of pheasants and 80 percent of rabbits were killed in the hail storms. Read more

0 notes