#sahelian history

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

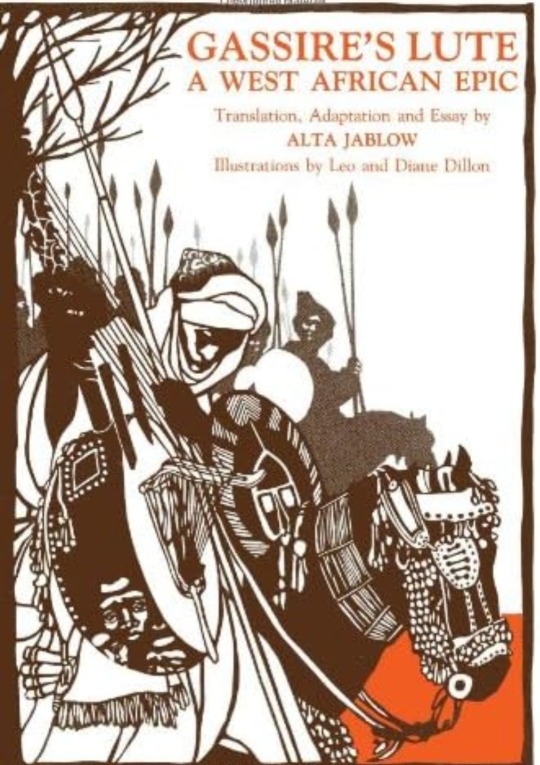

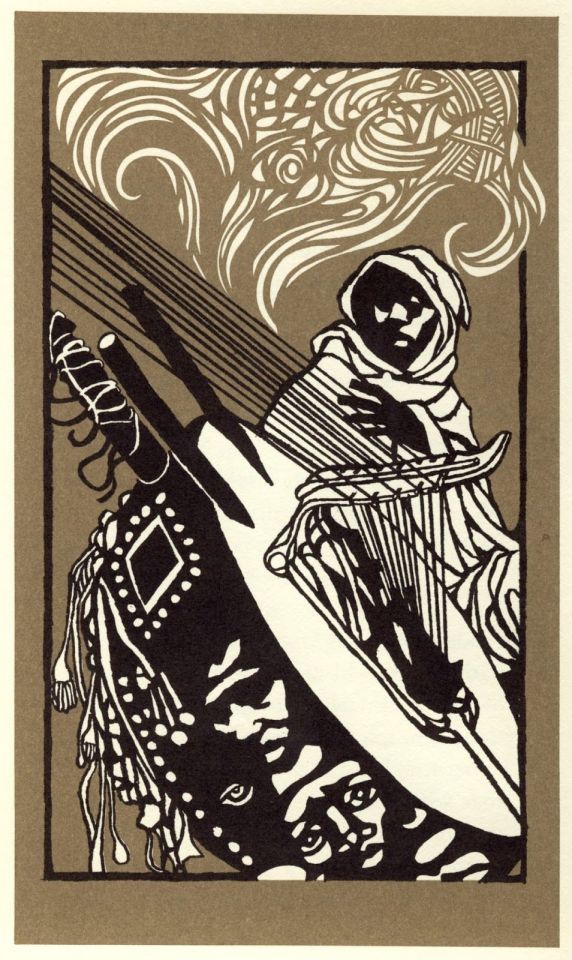

This orature legend of the birth of the Soninke bardic art chronicles the fall of Wagadou, the Soninke/Mande empire more popularly known as Ghana (not present day Ghana the country, which is named after this historical Mauritanian-Senegalese-Malian region empire).

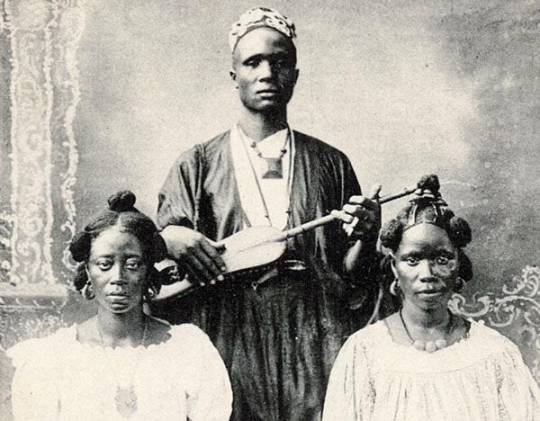

Follow Gassire the warrior prince, who turns away from nobility to become his people's first diari (griot: bard).

Here is a song named for the Soninke

https://open.spotify.com/track/55YdtD6BbmJ7NsDW4Z1Dpo?si=2Ogi-U2QQkuHoSZef_-PXw

Wagadou rose between the 1st-3rd century and fell in the 13th century, after being conquered by Sosso and submitting to the later Malian empire. Wagadou was preceded by Dhar Tichitt (1600 BC) and Djenne-Djenno, the ruins of which can be seen today. It was followed by Mali and Songhay, 2 of the most powerful kingdoms in the old Sahel.

Ghana means "warrior chief," and Wagadou (the Soninke name) could be named for the Wague (name for the nobility of the region) or named after the Soninke goddess. Legend says that when the 2 sons of the Kaya Maghan (king of gold, 800 Dinga Cisse, princes Khine and Dyabe fought over who should take the throne. Khine was victorious, continuing the Cisse Tounkara dynasty. However, Dyabe in humiliation, made a deal with the seven headed snake Bida, who promised victory over his brother in exchange for sacrificing a beautiful virgin every year. It was believed that the prosperity and gold that granted that prosperity was a result of these sacrifices, and so they continued until the brave fiance Maadi of the beauty Sia Yatabere was the first to rebel, slaying the snake and cutting its heads. Bida cursed Wagadu to drought and ruin, and sure enough, Wagadou fell, and the Soninke had to migrate southwards to find fertile land.

The now rare film Sia, Le Réve du Python, is based on this legend.

The capital of Ghana/Wagadou is believed to be Koumbi-Saleh. Here is an ambient instrumental piece paying homage to this ancient city:

https://open.spotify.com/track/4SRL7gOHRxrSb4TyvrBnvq?si=sNF5NePgQYqGOIsCbsdSCg

Vintage video of Soninke girls singing and flute player

https://youtu.be/bQm2aIVHakw?si=Rf3oYrcOsGnEAXTS

Soninke traditional drum dance

https://youtu.be/8FmiE_kdda0?si=7PQPVdYE0gNAJ4et

#sahel#sahelian history#soninke#wagadou#ouagadou#ghana empire#kaya maghan#sahelcore#bida#seven headed snake#wagadu#legend of wagadu#sia yatabere#sia dream of the python#dinga cisse#sahelian music#sahel aesthetic#gassire's lute#alta jablow#griots

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

As always a bit of a dip into historiography can frame the narrower discussions in proper perspective:

Before discussing in greater detail the Fulani jihad, a pre-emptive note to note that historiography of the Fulani tends to place a greater than justifiable emphasis on the reality that they entered history in a condition of violence that made their power over much of the Sahel a fixed point in time. To put it brutally this was also true of Scandinavians who entered history as pirates, thieves, murderers, rapists, and imperialists and refined the opportunistic raids of Vikings into the larger-scale imperial bids of Denmark and Sweden that lasted with the latter until Peter the Great annihilated it for all time at Poltava.

Modern Scandies seldom get remembered for their ancestors being some of the most violent people in violent times and openly and willfully glorying in the fact. Neither should 21st Century Fulani be judged on the basis of the Sokoto Caliphate as a guide to who they are and what they are now, with the promotion of this narrative serving a great many interests across post-colonial West African states.

#lightdancer comments on history#black history month#military history#african history#sahelian history#sokoto caliphate#fulani jihad#historiography#regional scapegoats

0 notes

Text

The Rise of Sahelian Kingdoms: Decentralized Monarchies in the Sahel (750 AD -18th Century)

The Sahelian kingdoms were a remarkable series of centralized kingdoms and empires that flourished in the Sahel, a region of grasslands south of the Sahara, spanning from the 8th century to the 19th century. What set these states apart was their ability to harness the wealth generated from controlling the key trade routes across the desert. This control, coupled with the possession of large pack…

View On WordPress

#African History#East African#east african history#Sahelian kingdoms#The Sahelian kingdoms#West African#West African history

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I consider myself something of a theologian,” she said. “And yet I still lack the answer to one question. Perhaps you can answer it for me. Which matters most, Catherine, when it comes to doing good – the conviction or the act?” There was a beat of silence as the enormity of what she’d just said sunk in. “You can’t be serious,” I said. “But I am,” she smiled. “I shall be, Catherine, the most terrifyingly heroic woman in the history of my kind. And in the end, together we will learn the answer to my question.” “I have learned much from you, darling one,” Akua Sahelian smiled. “I may fail, true. In my hour of judgement I may – most likely will – be unmade and cast into the deepest burning pits. But until then? Oh, what a glorious ride it will be.” She spun away from me, presence parting in full. “Now, my dear Catherine,” Diabolist said, and there was joyous laughter in her voice. “Shall we save some innocents?”

Just a normal teen girl talking about being a good person with her crush :)

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unlocking Ghana's Cultural Tapestry: A Journey Beyond Accra.

When travelers think of Ghana, the bustling capital city of Accra often takes center stage. While Accra offers a glimpse into the nation's vibrant energy and diversity, the true essence of Ghanaian culture lies in the distinct regional identities that exist beyond the city limits. To unlock a deeper understanding of this West African gem, it's essential to venture out and immerse yourself in the captivating cultural landscapes that make Ghana so remarkable.

Start your cultural odyssey in the Ashanti Region, the heartland of the prestigious Ashanti Kingdom. At the center of this cultural epicenter lies Kumasi, a city that pulses with history and tradition. Wander the halls of the magnificent Manhyia Palace, the seat of the Asantehene, the revered Ashanti monarch, and witness the grandeur of the Akwasidae Festival. This spectacular celebration honors the Ashanti's royal ancestors through mesmerizing dances, rhythmic drumming, and the intricate display of ornate kente cloth. Dive into the region's rich artisanal legacy by exploring the workshops of skilled kente weavers and gold jewelry makers, whose craftsmanship has been honed over generations.

Venture north to the captivating Northern Region, where the Dagomba, Gonja and other tribes have preserved their distinct cultural identity. In the bustling city of Tamale, marvel at the Sahelian-style architecture, with its mud-brick structures and striking silhouettes. Attend a traditional funeral ceremony or the vibrant Damba Festival, which commemorates the birth of the Prophet Muhammad through a dazzling display of music, dance, and religious rituals. Seek out the ancient mud-brick mosques, such as the Larabanga Mosque, one of the oldest in West Africa, and immerse yourself in the region's deep Islamic heritage.

Shifting your focus eastward, the Volta Region offers a glimpse into the unique Ewe culture. In towns like Ho and Keta, witness the mesmerizing traditional dances and learn about the Ewe's captivating language and culinary traditions. Explore the picturesque landscapes of the region, from the cascading Wli Waterfalls to the serene Kalakpa Resource Reserve, where you can connect with the rhythms of nature and the local communities.

Staying within the Greater Accra Region, venture to the fishing villages of Jamestown and Chorkor to experience the vibrant Ga culture. Observe the daily lives of the Ga people, their colorful architectural style, and their rich cultural celebrations, such as the Homowo Festival, which commemorates the victory over famine. Engage with the local artisans and learn about their time-honored crafts, from pottery to basket weaving.

Finally, make your way to the Central Region to immerse yourself in the Fante culture. Explore the historic towns of Cape Coast and Elmina, where the remnants of colonial-era forts and castles stand as silent witnesses to the region's complex past. Observe the traditional fishing practices and vibrant local markets, and attend the Oguaa Fetu Afahye, a captivating Fante cultural festival featuring music, dance, and mouthwatering cuisine.

By venturing beyond the confines of Accra, you'll unlock a deeper understanding of Ghana's diversity and the unique regional identities that make this country so captivating. Each region offers a distinct cultural experience, from the regal Ashanti heritage to the centuries-old Islamic influence in the north, the mesmerizing Ewe traditions in the east, the vibrant Ga community in the capital, and the maritime Fante culture in the center. Embrace the opportunity to connect with the local people, learn about their customs and beliefs, and leave with a newfound appreciation for the richness and complexity of Ghanaian culture.

So pack your bags, open your heart, and embark on a cultural odyssey that will leave you forever transformed by the diversity and beauty of Ghana, beyond the boundaries of its capital city. Unlock the true essence of this remarkable nation by venturing out and immersing yourself in the captivating regional identities that make Ghana a cultural tapestry worth exploring.

#bestghanatours#tourism#travel#ghana#tour package#accra ghana#tourist#travelwithus#worldwide privacy tour#summer#private#private tour#city tour#accra#voltaregion#northern lights#safari#nature#wildlife#adventure#marketing#sale#black tumblr#blacktravel#travelgram

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Warning: stupid world building/alt history ideas i came up with while high:

-Carthage wins Punic wars, establishes Mediterranean empire, and adopts (and spreads) a new radical religion based off Greek philosophy yet infused with Egyptian mythological subtext (devotees known as Philotanites, believe idea of Truth should be worshipped as represented by the idea of Zeus -> Athena = Isis -> Horus in a continuous Father, Daughter, Son, Mother relationship, scripture is claimed by the Hellens (now entirely diasporic) to be a poor translation of a now lost Athenian political comedy)

-Carthage focuses on building well established trans-Saharan trade roots over expanding into Europe beyond the south, earlier resulting development of unified sahelian kingdoms, Carthage moves capitals first to Memphis then to conquered Axum in order to be closer to eventual Persian rivals, due to this empire become Ethiopian over time (like Rome-> Byzantines in our history)

-Philotanite “Lovers” (eunuch monks) evangelize in Eire (Ireland), they establish colonies of converts, generations past and a man grown in such a colony begins having divine vision he records in haunting music and esoteric poetry, he claims (derived from his past faith) that Ultimate truth is an image of a Vulva, he establishes a theocracy across western and southern Europe, there is deep irony as the major religions of this earth give high theological importance to women yet they evolve to be equally patriarchal

Norse are never brought into expanding Mediterranean trade and are threatened by the growing Irish-based religion, as a result they focus on further exploration into the arctic regions, Norse colonization across what is now to us Eastern Canada and the U.S. state of Maine begins in (our) 13th century, they eventually expanding into the St Lawrence and reach the Great Lakes yet remain a minority and are never able to fully implement settler colonialism (yet were an apartheid state for awhile), Norse commit human sacrifices which upsets everyone they come into contact with

-Ghana annexes imperial lands and becomes the most powerful state on the eastern Atlantic, hears about Norse finds and sends their own explorers across the Atlantic, come into contact with Taino lands and develop a similar apartheid colonialism eventually

-During all this China keeps failing to unify, the Mongols never unify, north is never annexed, south is never annexed, Song Dynasty never falls, yet Song dynasty never regains the north, instead focuses on navy and commerce, expand throughout Southeast Asia through loaned ports, the first truly global empire (similar to those of Western Europe in our world), emperor is overthrown in a violent liberal uprising by 16th century

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

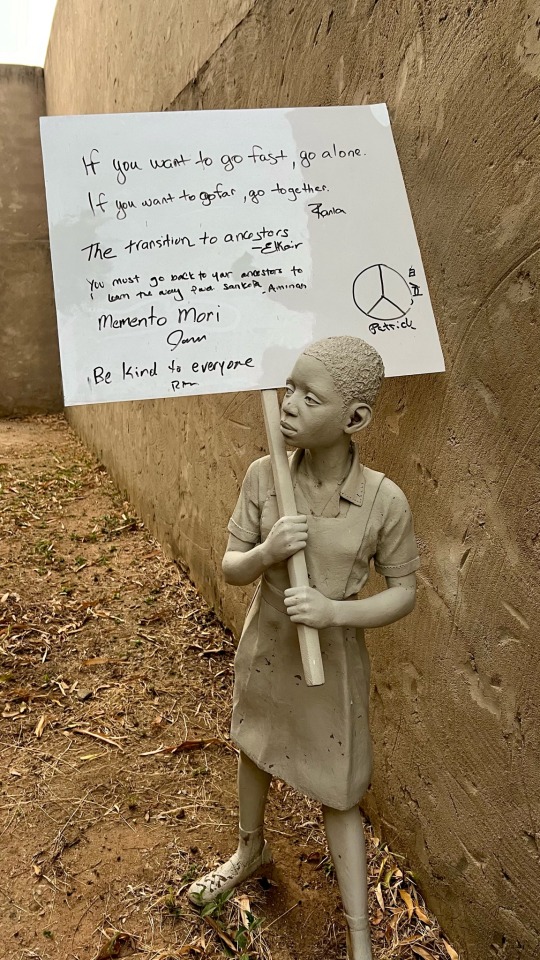

I took a captivating trip to the Nkyinkyim museum in Ada, just a 2-hour drive from Accra. The tour, priced at 100gh per person, was hosted by a griot, a very enthusiastic storyteller whose energy transformed the tour into an exciting journey.

The tour commenced with artifacts at the entrance, revealing the wonders of Sudano-Sahelian architecture dating back to 2500BC. The structures, crafted from organic materials like red mud, clay, and bamboo, showcased the remarkable skill and eco-friendly ingenuity of our ancestors. The community engagement in the construction process mirrored their deep connection with nature.

Intrigued by the symbolism etched on the walls, I marveled at the adinkra symbols, patterns, and shapes that were not only aesthetically pleasing, but held profound meanings. The journey unraveled the cultural ties across Africa, even discovering that Sudan boasts more ancient pyramids than Egypt.

The griot animatedly shared the wisdom behind the symbols—footprints symbolizing our shared humanity, the spider embodying intelligence, the tortoise exemplifying adaptability, and the snail conveying the concept of leaving a lasting legacy. The ant emerged as a powerful symbol of collaboration and community, echoed by the Nkyinkyim symbol representing resilience inspired by nature.

There was also a structure that was described as a life sized Lukasa memory board which challenged the notion that African traditions were solely oral. It became clear that our history was archived through symbols, writings, and memory boards, providing a unique form of communication despite the challenges faced during colonial times.

The journey progressed to a wall adorned with discs inspired by the Dikenga cross, a core symbol of Bakongo religion of the Kongo people symbolizing the cardinal points of human existence and the cycle of life.

The emotional apex was the veneration site—a symbolic memorial to enslaved ancestors. Sculptures conveyed tales of capture, from shock and determination to hidden identities and interrupted hair appointments. The vivid facial expressions on the sculptures offered a poignant glimpse into their harrowing experiences and the traumatizing ways through which they were captured.

There was a wall featuring diverse writings from across the continent, such as Nsibidi and vèvè, underscoring the richness of African history. The trip left me inspired to delve deeper into our heritage, resonating with the concept of Sankofa: going back to our ancestors' ways to chart a purposeful future.

The final chapter featured paintings showcasing accomplished individuals of African descent, a testament to resilience and exceptional lives emerging from the shadows of history. This transformative experience reinforced the belief that understanding our roots definitely shapes the trajectory of our future endeavors.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

In his influential book Desert Frontier, James Webb argues that the Western usage of the terms ‘white’ and ‘black’ as racial markers ‘seem to be a distant and refracted borrowing from the Arabo-African past’.

[...]

Hall retraces the history of Arabic racial discourse in the Sahara and Sahel since the 17th century, and their final intermixture with European racial discourses in the colonial period. With Webb, Hall argues that ecological changes in the region since the 16th century worked in favour of nomad pastoral groups to the disadvantage of sedentary communities, leading to the political and military dominance of the former over the latter. This dominance was partly legitimated in a racialist discourse on cultural and religious differences borrowed in part from the thinking of Ibn Khaldûn on the origins of phenotypical difference. Ibn Khaldûn refuted the ‘Ham thesis’, linking the origins of race to the story of Noah’s curse of his son Ham, but his thinking was racial in that he linked phenotypical difference to cultural, religious and mental inferiority, positioning the inhabitants of the most extreme zones, the Africans and the Slav populations of Europe close to animals. He explained this inferiority through the classic Greek theory of seven climatic zones, and the detrimental effects of living in the most northern and southern climates. Of course, this theory presented a major hermeneutical flaw in failing to explain the rise of Islam in such an intemperate climate as the Arabian Peninsula, which is refuted by insisting on the moderate influence of the sea winds, which temper the Arabian climate. But furthermore Ibn Khaldûn believed that the deficiencies caused by life in the harsh climatic zones could be mitigated by adherence to Islam*. This concept was, as Bruce Hall demonstrates, reworked in the Saharan context to become linked to descent from Arabic Muslim lineages.

First, ideas about ‘white’ Arab Islamic culture that originated in the IslamicMiddle East and North Africa were made part of Southern Saharan cultural identity by a reconfiguration of local genealogies connecting local Arabic- and Berber-speaking groups with important Arab Islamic historical figures in North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Second, local Arabo-Berber intellectuals rewrote the history of relations between their ancestors and ‘black’ Africans in a way that made them the bearers of Islamic orthodoxy and the holders of religious authority in the Sahelian region.

The political dominance of these Arabo-Berber groups, partly originating in ecological advantages, was thus legitimated by a claim on Islamic cultural and religious heritage, handed down in particular lineages of Arabo-Berber origins. Thus, religion, behaviour and descent were primal traits of ‘race’. Bruce Hall summons this reasoning up as: ‘To be “Black” is to be a son of Ham; to be “White” is to be a bearer of “true” Islam’.

*The story of the curse of Ham is known in the Muslim world. It is even very likely that it was through Arabic texts that the link between this qur"anic and biblical story, and the origin of races came into European discourse. The link between “curse” and “black” is explicit in Arabic as both are derived from the same Arabic root: SWD

Lecocq, B. 2010. Disputed Desert. Decolonisation, Competing Nationalisms and Tuareg Rebellions in Northern Mali.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

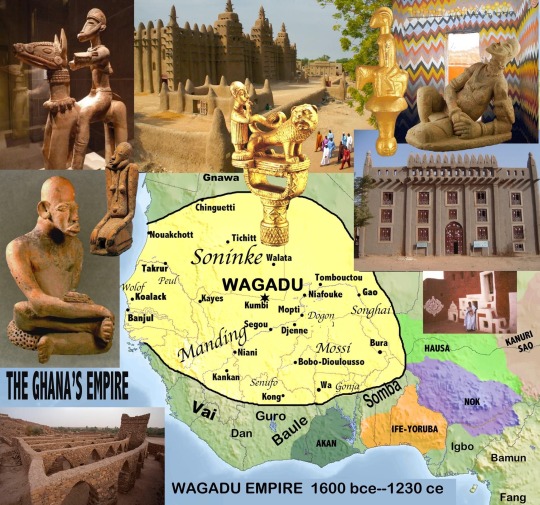

The Wagadu Empire (known to Europeans and Arabs as the Ghana Empire, named after the title of the emperor) is one of the most important African civilizations of all time.

European archaeologist, Augustin Holl, confirmed that its stone ruins were built by indigenous Soninke people (as opposed to Arabs) and date to at least 1600 bce.

Wagadu was the western arm of a great Sahelian-Sudanese trade across the savanna belt that stretched from the Takrur kingdom of Senegal to the Aksummite Kingdom of Ethiopia-Eritrea. In fact, the majority of gold that Kush traded with Kemet and West Asia was actually from its Sahelian trade network with Wagadu, the most gold rich civilization in world history.

The Wagadu Empire's stone ruins remain all across Mali and Mauritania, but few Black scholars are investigating it in favor of Kemet. Meanwhile, many Arab scholars are trying to convince the world that Wagadu's origins are actually from "Berber" (which they define as non-Black Saharans of Asiatic origin). One of the foundations they have to rest on is the ignorant Black muslim tradition of inventing false Arab origins for their kings in order to validate them in the muslim world. It is for this reason that Arabs cite the false lineages of Ghana's kings as Arab, a myth perpetuated by wannabe Arab Blacks in Africa.

This stupid tradition of assigning false Arab origins is not limited to Ancient Ghana, but virtually all Islamic people in Africa. The Somali are the most famous for inventing a false Arab origin, as are the Swahili. The Yoruba muslims even have blasphemously claimed their first king, Oduduwa, was from Arabia. So ashamed are these fools to claim indigenous West Africa as their motherland. Even today, many African American muslims imagine a fictional Arab origin for themselves.

However, let's be clear that the people and kings of Wagadu did NOT consider themselves Arab, Berber, or anything but indigenous West Africans.

They were not muslim, even when in the dusk of their era they allowed some muslims to trade in their city. The Wagadu practiced a spiritual system centered around Bida, the control of the reptilian instincts in man and the cultivation of these instincts into divine powers. This is similar to the Vodun veneration of Damballah Wedo and the Kemetic veneration of Wadjet.

The Arabization of Wagadu history is a later invention promoted by the Songhai Empire and later West African muslim shameless fools.

Until the African of the world values their own African culture MORE than the Arabs, we will continue to be historically impoverished. While Kemet was Black and great, it was just the tip of African glory. We must understand ALL of African civilization, not just Kemet.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sub Saharan African Kingdoms

Part 1 of 3

There are ruins all over Africa of past civilizations. Also traditional African Clothing, ancient metal farm tools, instruments , furniture etc.

Kano Nigeria

The Ancient Kano City Walls originally had an estimated height of 30 to 50 ft, about 40 ft thick at the base with 15 gates around it, and is about 12 miles (20 km) long

When, in 1903, British forces assaulted and captured the ancient city of Kano, Sir Frederick Lugard, High Commissioner of the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria, recorded that 'the extent and formidable nature of the fortifications surpassed the best informed anticipations of our officers. Needless to say, I have never seen or even imagined anything like it in Africa.' This impressive work of military engineering was then some 11 or 12 miles in length, 40 feet thick at the base and varying from 30 to 50 feet in height. A broad rampart walk ran behind the 4-foot thick loop-holed crest of the wall which was pierced by 13 gates, the whole further strengthened by a deep ditch.

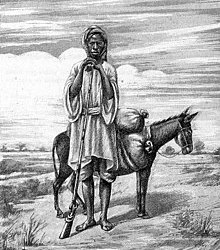

Old 1800s Illustration of Kano

The wall of Kano was constructed between the 11th and 12th century. At that time they were under indigenous peoples. Even when they were conquered, it was by a Fulani people, who are black African

Traditional Hausa structure, now part of the Gidan Museum. The original base structure goes back to the 1500, but modernized for tourism

A few more examples of old traditional Hausa Architecture of Nigerian and Niger Architecture

1 https://www.pinterest.com/shwat2013/traditional-hausa-architecture-from-nigeria-to-nig/

2

3

Zimbabwe

ruins of Burkina Faso ( West Africa)

ruins of Ghana

Gedi Kenya ( unknown history

Ruins of Tanzania ( African and Persian effort)

From the 15th century. Originally the home of the ruler Rumfa, now the Gidan Makama Museum Kanohttp://www.africaresource.com/rasta/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/Hausa-building.jpg

Old British Museum photo

There goes the mudhut only therory

Video Kano Nigeria ( 1:37 minutes)

Images of. West and Central Africans from the 1700s through early and mid 1900s

Mali

Timbuktu was part of the Mali Empire, which was founded by a Mandinka (Manding) peoples. They built in a style referred to as Sudano Sahelian, which is exclusively subSaharan African. They incorporated Arab styles atop it after converting to Islam.

Mansa Musa, a ruler of Mali in the 1300s, on a Spanish map

detail

Djenné

Was a major trade post town in the old trans Saharan Trade Network

It is from Portuguese sources that we learn a little more about the town. Duarte Pacheco Pereira, a sea-captain and explorer, mentions Djenné in his Esmeraldo de situ orbis which he wrote between 1506 and 1508: "...the city of Jany, inhabited by Negroes and surrounded by a stone wall, where there is great wealth of gold; tin and copper are greatly prized there, likewise red and blue cloths and salt ..."

Traditional Mali ( top picture is 20th century restoration based on the old building)

Ashanti empire

Between the 10th and 12th centuries AD the ethnic Akan people migrated into the forest belt of Southern Ghana and established several Akan states:

Ashanti empire ran from 1670-1902

Ashanti Yam festival; drawn by Thomas Bowdich in the 1800s

1874 Former palace of Asantehene being burned and ransacked by the British after the Third Anglo-Ashanti War

Image of an Ashanti home in Kumasi, before British colonization.

Pre Colonial Ashanti Homes

1

Part of UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Drawing from the 1800s

Akan people (Ashanti)always wore colorful Kente clothe

Benin

Benin was a precolonial Nigerian state from the 11th century to the 18th century. Here's a few drawing of the town by European travelers (circa 1600s thru 1700. Scroll through 4 pictures)

walls of old Benin

https://www.pinterest.com/shwat2013/benin-wall/

A little more about Benin

Ghanaian Empire of ancient times ( Tichit) and Middle ages ( Wagadu)

The oldest ruins in West Africa by The Soninke Peoples who spoke a Mande language was Tichit. It ran almost concurrently with ancient Egypt's early dynasty ( 2500 BC). In the middle ages, their was a resurgence with the Ghanaian Empire known as Wagadu

Why do we keep chasing unfounded history as blacks. We buy into some fantastic claims of a black presents in lands far from Africa, rather than study the lands we actually descend from..WEST AND CENTRAL AFRICA

From Wikipedia on African Architecture Tichit Walata

... Tichit is the oldest surviving collection of archaeological settlements in West Africa and the oldest of all stone base settlement south of the Sahara. It was built by the Soninke people and is thought to be the precursor of the Ghana empire (not to be confused with modern Ghana, but nearby in South Mauritania and southern Mali). It was settled by agropastoral people (they grew their own food and raised animals) around 2000 BCE - 300 BCE which makes it almost 1000 years older than previously thought.[10] One finds well laid out streets and fortified compounds all made out of skilled stone masonry. In all, there were 500 settlements.

Images of oldest ruins in Tichit, and from the "The Middle Ages"

Oldest

1

2

3

4

Middle Ages

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

.The town of Qualata was black African in it's origins. The building started long before it's Arabization. Islam didn't even exist when the initially settlements were built. We know this from archeological studied and Berber memoirs of people like Ibn Battuta in the 1300s, or this traveler of the 1500s ( a time when Qualata lost it's s importance and Timbuktu became the dominant trade town)

From Wikipedia

..The Berber diplomat, traveller and author, Leo Africanus, who visited the region in 1509-1510 gives a description in his book Descrittione dell’Africa: "Walata Kingdom: This is a small kingdom, and of mediocre condition compared to the other kingdoms of the blacks. In fact, the only inhabited places are three large villages and some huts spread about among the palm groves..

He reports on the dwindling condition of the town, and simultaneously reveals that this condition is substandard in contrast to other black African settlements ( though Qualata was nice for those days while it flourished). The nearby town of Chinguetti was predominantly Berber and Quadane is unknown, probably black African in origins. Both were well north of Qualata

Qualata

0 notes

Text

Mauritania best tour,

Mauritania best tour,

Mauritania, a land of striking contrasts and timeless beauty, is an unspoiled treasure waiting to be explored. From the vast expanses of the Sahara Desert to the rich cultural tapestry of its ancient cities, Mauritania offers a unique and unforgettable travel experience. Here’s your ultimate guide to discovering the best of Mauritania.

Nouakchott: The Bustling Capital Start your journey in Nouakchott, the vibrant capital of Mauritania. Here, you can immerse yourself in the local culture at the bustling markets, such as the Marché Capitale, where you can find traditional crafts, spices, and textiles. Don’t miss a visit to the impressive Grand Mosque and the Port de Pêche, where you can witness the colorful fishing boats returning with their daily catch.

Banc d'Arguin National Park: A Bird Watcher's Paradise For nature enthusiasts, Banc d'Arguin National Park is a must-visit. This UNESCO World Heritage site is one of the most important bird-watching destinations in the world, home to millions of migratory birds. The park’s coastal dunes, islands, and wetlands provide a stunning backdrop for birdwatching and photography.

Chinguetti: The Ancient Caravan City Step back in time with a visit to Chinguetti, one of Mauritania’s ancient cities. Known as the “City of Libraries,” Chinguetti boasts a rich history dating back to the 13th century. Explore its well-preserved libraries filled with ancient manuscripts and stroll through the narrow, winding streets of its old town, where you can marvel at the unique Sudano-Sahelian architecture.

Adrar Plateau: A Desert Adventure Embark on a desert adventure in the Adrar Plateau, a region renowned for its stunning landscapes and ancient rock art. The town of Atar serves as a gateway to this region, offering access to the breathtaking canyons of Amogjar and the oasis town of Terjit. Here, you can experience traditional nomadic hospitality and enjoy camel treks through the dunes.

Ouadane: The Ancient Trade Route Hub Visit the historic town of Ouadane, once a thriving center of trade and learning along the trans-Saharan trade routes. The town’s ancient ruins and stone houses tell the story of its illustrious past. Climb to the top of the town’s old fortress for panoramic views of the surrounding desert landscape.

Nouadhibou: The Gateway to the Desert Nouadhibou, Mauritania’s second-largest city, is the perfect starting point for an adventure into the desert. Explore the city’s vibrant port and take a trip to Cap Blanc, where you can see the remains of the famous shipwrecks along the coast. For a unique experience, visit the Banc d’Arguin National Park from here, or embark on a desert trek to discover the beauty of the Sahara.

Tidjikja: The Oasis of Tranquility End your journey in Tidjikja, an oasis town surrounded by palm groves and sandy dunes. Known for its traditional architecture and serene atmosphere, Tidjikja offers a peaceful retreat. Relax in the town’s lush gardens, visit the local market, and take in the stunning views of the surrounding desert.

Practical Information Best Time to Visit: The best time to visit Mauritania is between November and February when the weather is cooler and more pleasant. Travel Tips: Ensure you have a reliable guide or join an organized tour, especially when exploring remote desert areas. Always carry sufficient water and sun protection. Accommodation: From charming guesthouses in Chinguetti to modern hotels in Nouakchott, Mauritania offers a range of accommodation options to suit all budgets. Conclusion Mauritania is a destination like no other, offering a unique blend of natural beauty, ancient history, and rich cultural heritage. Whether you’re an adventure seeker, history buff, or nature lover, Mauritania promises an unforgettable journey through its diverse landscapes and timeless traditions. Pack your bags and get ready to uncover the hidden gems of this fascinating West African nation!

0 notes

Text

If you want history, I would go with East Africa, because the written tradition there is much longer. The historical tradition in Ethiopia goes back to antiquity, whereas writing was only brought to Sahelian West Africa in the Middle Ages and (as I think I've mentioned before) a lot of the sources that exist in manuscript form have yet to be seriously looked at by scholars. So a lot of Nigerian history before the modern period is rather spottily documented.

I'm mostly interested in Nigeria as a modern state, though, so obviously there's lots of documentation of that.

I'm very pro-Nigeria, Nigeria is one of my blorbos from geopolitics kind of like Singapore and modern Mongolia. I'm always reading about cool Nigeria facts and adding them to my list of cool Nigeria facts.

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

This article has a neat summary of the overall history of the Oyo Empire:

To further examine the history of the Oyo Empire, it should be noted that it too inherited some of the same weaknesses as the Zulu and other militarized autocratic states, namely the habit in pre-industrial autocracies that if generals were not properly rigidly kept in line by terror they were likely to do the pronunciamento regardless of whether or not it destabilized the state. As with the Ummayyads taking down enfeebled Byzantine and Sassanian infrastructure, so did the Sokoto Caliphate emerge like the icheneumon wasp from a caterpillar weakened by putsch and civil war, not a strong state taken down by the heroic valor of Mujahideen.

That, of course, is how the Fulani prefer to remember it as people tend to exaggerate the strengths of their enemies to strengthen their own claims to glory. In this the Oyo Empire was not unique tot the same realities that afflicted other states like it, the distinction is that it was not European power that destroyed it but a Jihad launched by one of the many bloody-handed reformer imperialists a dime a dozen in Islamic history.

#lightdancer comments on history#black history month#military history#african history#sahelian history#oyo empire#fulani jihad

0 notes

Text

Exploring Bambara Architecture: A Window into the Sudano-Sahelian Mud Architecture of West Africa

Bambara Architecture in Segou, the Sudano-Sahelian mud architecture typical of West Africa. The Bambara are a Mandé ethnic group native to much of West Africa, primarily southern Mali, Ghana, Guinea, Burkina Faso, and Senegal. They have been associated with the historic Bambara Empire. Today, they make up the largest Mandé ethnic group in Mali, with 80% of the population speaking the Bambara…

View On WordPress

#African architecture#African History#Bambara Architecture#Sudano-Sahelian mud architecture#West African#West African Architecture#West African history

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discovering Dori: Cultural Odyssey

Welcome to the enchanting city of Dori, a true treasure nestled in the heart of Burkina Faso. This vibrant city, filled with rich cultural heritage and breathtaking landscapes, promises an enthralling adventure for travel enthusiasts keen on an authentic experience. Get lost in the captivating local culture, treat your palate to delightful local cuisine, and embark on adrenaline-pumping activities that are sure to leave you captivated. Join us in uncovering the wonders of this hidden gem.

When to Go

Dori is a city that enjoys a tropical climate, marked by a clear distinction between the dry and rainy seasons. To fully enjoy the beauty of the city, plan your trip during the dry season, usually from October to April. This period offers a comfortable temperature range of 25 to 30 degrees Celsius, ideal for outdoor sightseeing and exploration.

How to Get There

Getting to Dori is an adventure on its own. The city is well-connected by road, and you can either hire a car or take a taxi from Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso. The journey covers an approximate distance of 400 kilometers, typically taking around 7 hours. If you prefer a quicker alternative, domestic flights are available from Ouagadougou to the Dori Airport.

Where to Stay

Dori boasts a range of accommodations suited to every traveler’s needs, from quaint guesthouses to beautiful eco-lodges. For an immersive experience, try out a traditional mud-brick house, where you can enjoy the unique architecture and experience the traditional lifestyle firsthand.

What to Do and See

- Immerse Yourself in Vibrant Culture: Experience Dori’s heart by immersing yourself in the local culture. Visit the bustling Dori market, where a riot of colors, aromatic spices, and traditional crafts beckon. Engage with the friendly locals, understand their customs, indulge in traditional music and dance performances, and let their warmth and hospitality mesmerize you. - Gastronomic Delights: Dori’s cuisine is a true reflection of its rich history and diverse cultural influences. Feast on delightful local delicacies such as tô (a thick millet or corn porridge), riz gras (a flavorful rice dish), and the famous poyo (fermented millet beer). Traverse local food stalls and restaurants to savor an array of vibrant flavors that will tantalize your taste buds. - Embark on Adventurous Excursions: Dori offers a feast for thrill-seekers with a spectrum of exciting activities. Explore the striking red cliffs of Gobnangou, delve into hidden caves adorned with ancient rock paintings, hike through the wildlife-rich Arli National Park, and witness a magical sunset over the Sahelian sand dunes. - Connect with History: Uncover Dori’s historical significance by visiting the Grand Mosque, renowned for its architectural splendor. Wander through the ancient ruins of Loropéni, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and marvel at the well-preserved stone walls that whisper tales of the Mossi Kingdom.

Tips for a Memorable Visit

- Dress modestly and adhere to local customs and traditions. Always seek permission before photographing people. - Learn a few basic French phrases to enhance your interaction with the locals. - Stay hydrated and protect yourself from the sun by using sunscreen, wearing a hat, and carrying a water bottle.

Money and Nightlife

The official currency is the West African CFA franc. Carry enough cash as not all establishments accept card payments. As the sun sets, Dori comes to life with energetic musical performances filled with traditional music, dance, and the infectious energy of the locals.

Transport and Shopping

Getting around Dori is best done by hiring a local taxi or riding a motorbike, known as a zemidjan. Always negotiate the fare before starting your journey. Don’t miss exploring the local markets for unique handicrafts, woven fabrics, and traditional jewelry, perfect as souvenirs of your memorable stay in Dori.

Conclusion

Dori, with its vibrant culture, tantalizing cuisine, and exciting adventures, offers an unforgettable travel experience. Dive deep into the cultural fabric, savor the traditional cuisine, and embark on exhilarating adventures that stir your wanderlust. With open arms, Dori, the hidden gem of Burkina Faso, invites you to a world of breathtaking beauty and heartwarming experiences. Read the full article

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Was Akua Sahelian an 'actual person' before 'Ye Mighty'"-the greatest thread in the history of forums, locked by a moderator after 12239 pages of heated debate, except 1,223,899 of the comments are from me

You know that post thats like "gun to your head, if you had to give a 30 minute presentation on any topic with no preparation or you die, what are you talking about?"

I can do that with Akua Sahelian except that isnt long enough because guide is 3 million words long, so you have to threaten me with the gun to make me stop at 30 minutes

#practical guide to evil#pgte#sorry to @burn-throughout-eternity for going on an extended monologue on your post

30 notes

·

View notes