#roz milner

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

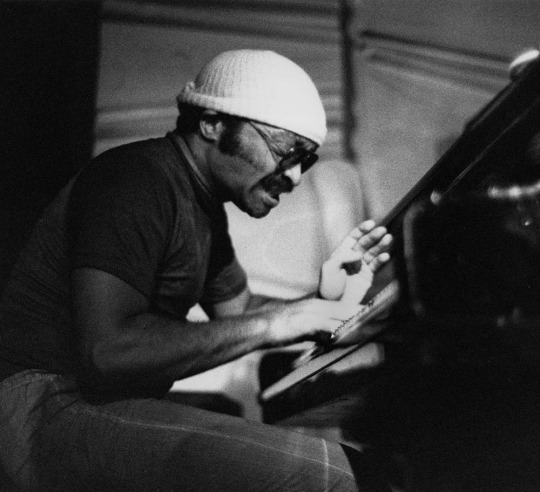

Listening Post: Gastr Del Sol

Photo by James Crump

Gastr Del Sol was the convergence of two individuals who had not spent their youths like anyone else and were on their way to lives quite unlike most lives. Between 1991 and 1998 David Grubbs and Jim O’Rourke made a sequence of records that simultaneously pointed out what a lot of music listeners were missing and where music might go next if it was really interested in being interesting. Grubbs came from Louisville, Kentucky’s hardcore scene; he played in Squirrel Bait while he was in high school, and took Bastro with him to college. Jim O’Rourke grew up tracking down recordings from the far reaches of every fringe and then setting about making his own place within each method he learned. Before he was out of college, he’d already made connections with Henry Kaiser, Derek Bailey and the folks at Ina GRM. Each was a guy who knew what the other did not, and their collaboration pushed both to make music that they would never make again with anyone else.

Gastr Del Sol began when Grubbs decided to let Bastro get quiet, and made one LP before O’Rourke came aboard. Their first album together, Crookt, Crackt, Or Fly, was assembled from miniaturized poetry, elongated post-punk riffs, frozen improvisation and fluid, texturally-focused compositions. Their last, Camofleur, is a droll pop statement completed just weeks prior to the collapse of the duo’s relationship. The acrimony between them took a couple of decades to die down, but around the same time that they buried the hatchet, a live recording of their final concert surfaced. We Have Dozens Of Titles shuffles together that performance plus every compilation, single, or EP track that Gastr Del Sol released outside their core Drag City discography.

Intro by Bill Meyer

Jonathan Shaw: I have admired Gastr del Sol from a sort of distance. I like “At Night and At Night,” from the terrific Hey Drag Citycomp; I know Upgrade & Afterlife quite well and dearly love “Dry Bones in the Valley...”, the Fahey cover collab with Tony Conrad. The first song on this new-ish record sidles in alongside those wooden textures, but is a more anxious affair. I like that it never quite boils over or takes its propulsive energies to catharsis. It’s sort of a complement to the conversation with the French kid blowing up firecrackers at the track’s close: it can’t quite move forward, in spite of all of the things that want it to.

That’s also a handy metaphor for my relationship to the music. When I have listened to Crookt, Cracked..., I get the sense that these are really, really smart folks, doing some smart stuff, but I haven’t quite connected with and moved into the sounds. They can be forbiddingly remote. So, I am glad for this record, and its invitation to revisit the band’s trajectory.

youtube

Bill Meyer: Each record is so different that I can easily see someone liking one and not likening others, and if you held a gun to my head, Upgrade & Afterlife is the one I would name as my favorite. Which makes it all the more interesting that this collection spans their existence from O’Rourke’s first presence (the Teenbeat single — and it’s pretty amazing that they ended up on that label) to the very last concert (that trip is probably when the encounter with the Francophone child occurred, since the concert was in Quebec).

By virtue of its length and timespan, We Have Dozens Of Titles shows more sides of Gastr Del Sol than any other record.

Bryon Hayes: I think that’s one of the band’s traits that I find appealing, that their sound and approach shifted from record to record. “At Night and At Night” was my introduction to the band, and it also seems to encapsulate multiple faces of Gastr Del Sol in a single track: a drone intro, followed by a guitar/poetry passage, and then a dollop of minimalism accompanied by backwards cymbal splashes. I bought Hey Drag City for Pavement, Silver Jews, and Smog but was introduced to some new and intriguing sounds across the whole of the comp. That track, and Gastr Del Sol as a whole, always felt like a riddle or a logic puzzle to me, albeit one that continuously changed, so it wasn’t possible to “solve” it. But I actually like that fact: the thrill of the act of investigating is pure enjoyment itself.

I never did get to experience Gastr Del Sol in a live setting, so those tracks on We Have Dozens of Titles are particularly revelatory for me. I like the more stripped-down setting of “The Seasons Reverse,” for example. Maybe even more than the version on Camofleur. I’d also bet that the field recording of the kids came from Victoriaville. The town is far enough into Quebec that it’s likely there was a language barrier between O’Rourke and the local youth at the time. Also, the drawn-out version of “Blues Subtitled No Sense of Wonder” feels much fuller and richer in the live setting than it does on Camofleur. I’m not saying I dislike that album, but I too would pick Upgrade & Afterlife as my favorite...

Bill Meyer: Because I lived in the same town as Gastr Del Sol, I was fortunate to see them a lot. The concerts were pretty different from one another, and didn’t always sound much like the most recently released record. When they played with John McEntire, things could be more rock-ish, and I have one fond memory of them getting pretty wild with the feedback. Afterwards O’Rourke seemed embarrassed, like he’d lost control and done the wrong thing. There was room for spontaneity, but they were not an improv act. In 1997 they did lock into the two guys with two acoustic guitars thing for a while, probably because they had a fair number of out-of-town gigs in their later years; they didn’t necessarily want to lug a lot of gear around.

Another aspect of living in the same town with them was seeing the other things they had going. O’Rourke could often be seen accompanying someone whose work he championed (ex: Rafael Toral), and they both played with Red Krayola (although O’Rourke bailed for a while and Grubbs kept going), Edith Frost, and Arnold Dreyblatt.

Jonathan Shaw: Never saw the band, and the live material on this comp is what’s impressing me most. Given my proclivities toward their work with acoustic guitars, I am most compelled by “Onion Orange,” which works a space between gentle and tense to very satisfying effect. The repetitive sequence of notes in that initial six-or-so minutes is really engaging; it invites anticipation, flirts with letting that become apprehension. I can imagine that would be even more powerful in a real room, with the players really making the noises in front of you. But even here, via the mp3 I am playing on a device, it’s strong stuff.

Bill Meyer: I still need to a-b that with the original on Grubbs’ solo album.

That album, Banana Cabbage, Potato Lettuce, Onion Orange, seems not to be on Bandcamp, and Table of the Elements is long defunct. I’ll have to pull out my CD and play it. On the original edition, Grubbs plays everything, but O’Rourke recorded two of the album’s three tracks. I remember it being very still, a Grubbs take on Morton Feldman. What you hear in this live performance, Jonathan, is probably what makes me think I like this new version better than the original. There’s a management of tension that probably comes from two people playing it together in real time.

youtube

The way that We Have Dozens Of Titles is sequenced, with live tracks littered throughout the collection, makes it easy to forget that we’re hearing a complete set here.

Ian Mathers: There’s a relatively well-known tweet (for those of us that are too online, at least) where a guy who’s only ever seen one movie sees a second and immediately compares it to his only experience. As someone who’s never heard Gastr del Sol before (although they’ve lingered somewhere on my impossibly long “get to this someday” list) and only really knows Jim O’Rourke’s work via his Bad Timing album, I had my own “Getting a lot of ‘Boss Baby’ vibes from this...” moment playing the opening live version of “The Seasons Reverse.” The guitar playing there immediately put me in mind of Bad Timing, which isn’t a bad thing! I was slightly relieved when this compilation pretty immediately shows off different aspects of his and Grubbs’ sound, even in the other live tracks.

And while I did enjoy all of We Have Dozens of Titles, enough so that I’m wondering based on the comments here which of their albums I should check out next, the live tracks do feel like a cut above everything else. I’m probably going to try listening to just them, and while I respect the choice to scatter them throughout this release despite being one show (do we have any idea if they preserved the order of the setlist, or jumbled that up as well as splitting them up?) there is a part of me that wishes it was a separate release. Which is kind of silly, I know — absolutely nothing is stopping me from just playing the live stuff whenever I want, and I’m very glad to have the rest of the material here. My first question for those more knowledgeable: is the album version of “Blues Subtitled No Sense of Wonder” as amazing as the live one here, and should I make that my next stop?

Bill Meyer: If you like the live version of “Blues Subtitled No Sense of Wonder,” you definitely need to check out the studio version. For that reason, I’d point you to Camofleur and then suggest that you work your way backwards through the catalog.

youtube

Bryon Hayes: The album version has beautiful vocal harmonies with lyrics that are dryly humorous; the title of the box set is derived from them, actually. The music on the box set version feels fuller and louder than that on the album, the electronics bolder and noisier, accompanied by rich organ tones. Also, that interlude of shouted movie dialogue (or whatever it is), is not in the Camofleur version. Both are appealing, but I enjoy the live version slightly more. If Grubbs sang on the live version, it might be the clear winner for me.

Ian Mathers: Interesting, thanks for the tips! If I’m remembering correctly, there’s no vocals on this collection for at least a while, and I was slightly nonplussed when they came in; not bad, certainly, but it felt slightly out of place with the music. (I was working while listening, which might be the culprit there.) I’ll be interested to A/B the two versions and see what I think.

Bill Meyer: I just drove past the Lyon & Healy building at Lake and Ogden, which prompts the question — what do you make of “The Harp Factory On Lake Street”?

Jonathan Shaw: I sort of like it when there are vocals — in part because of the poetic nature of what’s sung (see “Rebecca Sylvester” on Upgrade & Afterlife), in part because it feels grounding in musical contexts that frequently get very abstract.

Bill Meyer: I like the way you frame that, Jonathan. Grubbs’ words do have a way of anchoring part of the music, bringing a sonic fixedness that contrasts with the music around them, but also introducing an uncertainty of their own because of their sometimes-oblique content.

Roz Milner: I’ve just been lurking this thread. I’m not familiar with this group, although I do like what little Jim O’Rourke’s music I’ve heard (Bad Timing, Happy Days). Any recommendations on where to start with them?

Tim Clarke: I’d start with Camoufleur, which is easily their most accessible album. I have a bit of an uneasy relationship with Gastr Del Sol. I got into them soon after I became obsessed with Jim O’Rourke’s Eureka, but it was quite a shift in tone from that album. I do enjoy Camoufleur a lot, and the album versions of “The Seasons Reverse” and “Blues Subtitled No Sense of Wonder” are, in my opinion, far superior to the live versions on We Have Dozens of Titles.

Gastr Del Sol are quintessentially experimental, in that much of their music sounds so open-ended, as though O’Rourke and Grubbs are constantly wondering what x would sound like played at the same time as y, whether it’s an open, suspended acoustic guitar voicing alongside a sour synthesizer drone, or some piano with some field recordings or samples. Upgrade & Afterlife actually freaks me out! The first time I listened to it after buying it from Rough Trade in London, I couldn’t venture past the opening track as a massive gnarly insect flew in through my open window while I was listening to it on a spring evening. It scared me so much I don’t think I’ve revisited the album since. There are moments on We Have Dozens of Titles that are truly magical, so I think I’ll have to get over my fear and revisit Upgrade & Afterlife after all this time.

Christian Carey: The timing of this release is interesting. David Grubbs was just appointed Distinguished University Professor by CUNY, the highest faculty distinction possible. In addition, he was just awarded the Berlin Prize, and will be in residence there next year. Wonder if the awards might have helped to fund the recording project.

Jonathan Shaw: Distinguished Prof at CUNY — pretty swell. Makes sense. Some of Gastr del Sol’s headiest stuff has the feel of the “experimental,” and in ways that engage the connotations of knowledge and concept in that term (which often gets used lightly and lazily, IMHO). That might have something to do with why I like the live tracks so much. There’s an organic quality to them. Still thorny and challenging music, like the ebbs and flows that make “Dictionary of Handwriting” disorienting and strange. But it’s happening. It’s made, not just thought or assembled.

Jennifer Kelly: Once again, not super immersed in this band, though I had a copy of Crookt, Crackt or Fly at one time, which I can’t find and don’t remember very well, though I’m listening to it on YouTube right now, and the combination of Grubbs’ wandering vocals and aggressive, stabbing guitars seems familiar-ish. So, coming to this a bit cold, though I’ve enjoyed Grubbs’ more recent work with Ryley Walker and Jan St. Werner — and there are definitely some common threads. Nonlinearity, an elastic sense of key and rhythm, a haunted room kind of aesthetic.

I found this track-by-track exposition at the Quietus, which I was trying to read as the songs came up and it’s quite good. I especially liked the paragraphs about “The Bells of St. Mary’s,” written for what sounds like a truly bizarre Christmas comp with Merzbow and Melt Banana on it. Gastr del Sol’s lone concession to the holiday form was sleigh bells, though Grubbs says the main reference was to “I Wanna Be Your Dog” not “Jinglebells.”

Anyway, you might enjoy this.

Tim Clarke: In addition to the Quietus piece, this recent podcast interview is also very enlightening in regard to the history of the band. A rare opportunity to hear Jim O’Rourke chat lightheartedly too.

Having spent more time with the album now, I realize that my listening gets derailed by a couple of Grubbs’ and O’Rourke’s tendencies with this music. The first is when Grubbs does a kind of scat singing that follows the spiky contours of the acoustic guitar parts. And the second is when they retreat into near silence.

Bill Meyer: Near-silence is an O’Rourke strategy to make sure that the volume is set high enough when you get to the loud part.

Christian Carey: I’m curious what connections to later projects people hear in the recording. As TJ mentioned, there are some mannerisms that seem to forecast avant moves by both Grubbs and O’Rourke, with greater assuredness in the idiom. The post-rock vibe is unmistakable, and I am finding the songs with connections to Tortoise et. al. to be the most compelling music-making here.

Bill Meyer: Re: similarities with Tortoise, it’s worth keeping in mind that John McEntire of Tortoise was also a member of Bastro and a key non-member contributor to Gastr Del Sol. Re: the term post-rock, I appreciate the irony that Gastr Del Sol was actually O’Rourke’s entree into rock following years of intense work in improvisation, musique concrete, etc. with people like Henry Kaiser, Eddie Prevost, Christoph Heemann and Illusion of Safety. It was his “I’m almost ready to rock" project.

Ian Mathers: Roz, if you still haven’t settled on a way to check out Gastr del Sol, I was in a similar position to you and honestly, I found this compilation a pretty welcoming (and broad-ranging) introduction! I haven’t moved on to checking out any of their albums yet, but I have played We Have Dozens of Titles a number of times, and while I’m still experiencing it more as a gestalt than I am picking out specific elements (so I’m not sure how I’d answer Christian’s question at the moment, for example), I find the time just slipping away when I do. I was reading Steven Thomas Erlewine’s newsletter recently where he was discussing this collection and he described Gastr del Sol as “music that changes the temperature of the room,” and I keep coming back to that as an apt description of what I’m experiencing.

Bryon Hayes: I read somewhere that Grubbs’ The Plain Where the Palace Stood is his solo album most similar to his work in Gastr Del Sol. I’m listening to that record now and it actually reminds me of the little Bastro that I’ve heard along with parts of The Serpentine Similar.

youtube

Bill Meyer: Gastr Del Sol’s existence corresponded with Grubbs’ time at University of Chicago, where he was getting his PhD. I believe it was in poetry, and the words he wrote for the band’s songs reflect that study.

Christian Carey: I've been having fun poring over David Grubbs’ trilogy of books and guessing which stories might be about Gastr del Sol. He's excellent at being covert, but I would be surprised if they weren't featured in some of his writing.

#dusted magazine#listeningpost#gastr del sol#jim o'rourke#david grubbs#we have dozens of titles#drag city#bill meyer#jonathan shaw#bryon hayes#ian mathers#roz milner#tim clarke#christian carey#jennifer kelly

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Friday all! Today I’m thrilled to present TFR’s second guest column, a review of last year’s dystopian debut novel Disobedience by Daniel Sarah Karasik, written by critic Roz Milner.

I hadn’t heard of this book when Roz brought it to me, which is exactly what I’m looking for 🤩

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frank Zappa - Olympic Auditorium, Los Angeles, California, March 7, 1970

Over on Aquarium Drunkard, Roz Milner wrote up the latest archival Zappa haul — Funky Nothingness — which is kind of a lost Hot Rats follow-up. Kind of! As a bonus, Roz passed along this eeeeeessential bootleg from the same period. Take it away, Roz!

After breaking up the Mothers in 1969, Frank Zappa spent a few months away from the road. He sat in with a few bands — Captain Beefheart, Pink Floyd, Archie Shepp — but didn't play any gigs until Feb. 1970, when he put together a pickup band and played a show in San Diego. About a month later, he road-tested a group he'd been recording with in the studio: Max Bennett, Aynsley Dunbar, Sugarcane Harris, and Ian Underwood. They played a set of mostly new, mostly blues-based material: "Chunga's Revenge," "Directly From My Heart to You," and "Sharleena." These would all get released later in the year. But "Twinkle Tits," a waltz built around some themes he's repurposed for other songs, fell through the cracks. With a name like that, it's not hard to see why Reprise balked. But it's a nice vehicle for Zappa and Harris to stretch out on — it's too bad this one's got a tape flip right in the middle of Frank's solo.

A few weeks ago, UMe released Funky Nothingness, a look at this period and an unreleased record that sat on the shelf for over 50 years. But for almost that long, the only glimpse fans had of this band was this audience tape. Indeed, I've heard it was the first Zappa bootleg — and there's more than a few of those. It's got a lot of ambience and with headphones, you feel like you're right in the room. Make sure you stick around for the encore — a (Beefheart-less, alas) jam on "Willie The Pimp."

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ian Beale is a fictional character from the BBC soap opera EastEnders, played by Adam Woodyatt. He is the drama's longest-serving main character and one of four remaining original characters, the others being his mother, Kathy (Gillian Taylforth), his long standing best friend and ex-wife, Sharon Watts (Letitia Dean) and Queen Vic barmaid, Tracey (Jane Slaughter). The character appeared in his 2,000th episode in the show on 26 March 2007,[1] and his 3,000th on 27 May 2016.[2] Woodyatt took an extended break from EastEnders on 22 January 2021.[3][4] He made appearances on 12 December 2022 and 22 June 2023, prior to a full-time return on 22 August of that year.

Ian is the most-married character in EastEnders history, with six marriages to five women: Cindy Beale (Michelle Collins), Mel Owen (Tamzin Outhwaite), Laura Beale (Hannah Waterman), twice to Jane Beale (Laurie Brett), and Sharon, and three aborted engagements to Mandy Salter (Nicola Stapleton), Denise Fox (Diane Parish) and Cindy. He has fathered three children (Peter; played by Thomas Law, Lucy; played by Hetti Bywater, and Bobby Beale; played by Clay Milner Russell), raised Cindy's son Steven Beale (Aaron Sidwell), who he believed to be his, and was the guardian of Cindy's daughter, Cindy Williams (Mimi Keene). Ian is the owner of 45 Albert Square, traditionally represented within the series as the family home of the Beale and Fowler family. In 2020, he bought The Queen Victoria public house for Sharon, leaving after she poisoned him in revenge for his involvement in Dennis Rickman's (Bleu Landau) death on EastEnders' 35th anniversary.

Upon his return in 2023, he is back at 45 Albert Square reunited with his first wife Cindy after reuniting off-screen the year prior, who was going by the pseudonym "Rose Knight", after faking her death 25 years prior in a witness protection scheme due to giving information about her criminal inmate. After Cindy's witness protection officer reveals that Jackie Ford has died, Cindy resumes her former life. In Christmas 2024, Cindy's affair with Junior is revealed and he is a suspect in the "Who Attacked Cindy?" storyline for the show's 40th anniversary.

Ian was voted one of the top five television characters "we most love to hate" in a Channel 4 poll in 2001.[24] In 2009, Ian Beale came ninth in a poll by British men's magazine Loaded for "Top Soap Bloke".[25] Woodyatt has received a number of award nominations for his portrayal of Ian, including a Best Actor nomination at the 2010 British Soap Awards and a nomination for Best Performance in a Serial Drama at the 2012 National Television Awards.[26][27] In 2013, Woodyatt received the British Soap Award for Lifetime Achievement at the 2013 ceremony.[28] Following thirty years of service to EastEnders, Woodyatt was awarded with his first Best Actor accolade at 2015 British Soap Awards.[29] At this ceremony, he also won Best On-Screen Partnership alongside Laurie Brett.[29]

Author Dorothy Hobson has stated that Ian Beale is a "major creation" capturing the personification of political attitudes taken up during the Conservative government of the 1980s.[10] She suggests that Ian Beale is a "major representation of a young man" of that era, and that his sensitive portrayal by Adam Woodyatt is "perhaps unrecognised".[10] Roz Paterson of the Daily Record branded Ian "eminently unlovable" and stated that Melanie proposing to him represented a growing trend in women proposing.[30] Holy Soap said that Ian's most memorable moment was "His attempted murder in the Square".[31] In 2009, Virgin Media called Ian "the most boring and selfish man in Walford" and felt that he deserved to lose his wife, Jane.[32] In 2014, Tony Stewart from the Daily Mirror called Ian a "spineless little weasel" and "Beale The Squeal" and believed that it was unlikely that Denise would go through with her wedding to him.[33] In 2020, Sara Wallis and Ian Hyland from the same website placed Ian ninth on their ranked list of the best EastEnders characters of all time, writing that Ian "has the resilience of a cockroach – and also, some would say, the charm".[34]

0 notes

Text

This House Is Not A Home: Roz Milner reviews Kevin Lambert’s MAY OUR JOY ENDURE (Biblioasis, translated by Donald Winkler)

0 notes

Text

Welcome to the Trans Literary Supplement, a new space for writers to share work and literary views, particularly those relating to trans literature of all sorts. Or, in other words, Roz Milner writing fiction and reviews until other people feel like this is a space worth contributing to

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention — Whisky-A-Go-Go 1968 (Zappa Records/UMe)

Photo by George Rodriguez

youtube

In late July 1968, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention brought a three-ring circus to Los Angeles’s Whisky-A-Go-Go nightclub. They had some history at the club. They had played there early in their careers, but by this point they were an established act: they’d toured Europe, released four records and Zappa was in the process of starting his own record label. This July evening was a showcase not just for the Mothers, then, but also for acts he’d signed: The GTOs, a group of singers who doubled as groupies, street musician Wild Man Fisher and Alice Cooper. The show was recorded for possible release.

That album never materialized in Zappa’s lifetime, but some 56 years later this evening’s events are here on Whisky-A-Go-Go 1968. It’s not the full night, just the Mothers sets, boiling down a five-hour show to just under three.

As far as live Zappa albums go, Whisky-A-Go-Go 1968 is a mixed bag. There's moments where Zappa guitar shows him growing into a compelling soloist and there’s few songs here that never made it onto a previous Zappa record. But when compared to something like The Ark or Ahead of Their Time, this never quite gels: there's a sense of hesitation or maybe the band wasn’t having a good night. It’s interesting and occasionally really good, but it’s not as exciting as you might hope.

The first half of the set wavers between free-form jams and the Mothers goofing on 1950s doo wop: “Oh In the Sky,” “Memories of El Monte,” “My Boyfriend’s Back.” Zappa did have a genuine admiration for this kind of music, but between Roy Estrada’s strangled falsetto and Zappa’s deadpan delivery on these, it’s hard not to read these as the Mothers goofing around. It’s definitely more for hardcore fans. The improvisations are fine, too, with the little flourishes that pop up on Mothers records: stomping rhythms, vocal shouts, harsh bursts of sounds.

Some moments you had to be there for. “Della’s Preamble” incorporates audience participation that doesn’t come through on record. During moments of jamming you can hear shouts and yells and Zappa calling people up on the stage to dance. There’s even a bit where he’s presented with a pair of wings.

As the first set winds down, the band starts to stretch out on instrumentals and flex their muscles. “King Kong” has some wild blowing from the band’s brass section and lets both Zappa and Preston stretch out for solos before the band deftly segues into Edgard Varese’s “Octandre” and more improvisations.

The second set is more focused on the Mothers instrumental side: two takes of “The Duke” (actually an early version of “Little House I Used To Live In,” not the similarly named “Duke of Prunes'') that have Zappa taking completely different guitar solos, then the band moves into “Khaki Sack.” It’s a loose R&B groove with lots of room for solos, showing the band’s chops extended to far more than just goofy rock pastiches. Then the band moves into a lengthy performance of “The Whip,” where Zappa’s guitar playing takes on a nice psychedelic tinge, before the band moves on into some extended jamming for “Whisky Chouflee.” Finally, the disc ends with a nice treat: the first live performance of “Brown Shoes Don’t Make It,” from 1967’s Absolutely Free. It’s a little rough and the way it jumps around exposes some of this group’s limitations on stage, but the band pulls it together when they go back to the theme on “Brown Shoes Shuffle.”

In some ways, it’s best to compare this to 1974’s Roxy and Elsewhere, another live record that was recorded basically like an on-stage recording session. There, Zappa played several shows with the same set list with the intent of editing the best bits together for a live record; it’s similar to the approach Zappa refers to on here occasionally. But that project never materialized in his lifetime. One small excerpt came out on Uncle Meat, another on You Can’t Do That On Stage Anymore Vol. 5. Was he unhappy with this session? It’s impossible to say at this point. But this set documents a pretty significant occasion for the band, both as a homecoming and as a nice audio document of this group. Indeed, there’s not much live material from this early in Zappa’s career, let alone in this high quality sound.

Hardcore Zappa fans should consider Whisky-A-Go-Go 1968 an instant buy, but more casual ones may find the first half a little bulky. Those who enjoy the live bits of albums like Burnt Weeny Sandwich or Weasels Ripped My Flesh will find a lot to dig into here.

Roz Milner

#frank zappa#mothers of invention#whisky-a-go-go 168#zappa records#UMe#roz milner#albumreview#dusted magazine#rock#live album#doo wop

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ivo Perelman and Nate Wooley — Polarity 3 (Burning Ambulance)

Polarity 3 is hard to parse. Saxophonist Ivo Perelman and trumpeter Nate Wooley have recorded two previous albums as a duo, both pushing at the boundaries of free jazz and improvisation.

Their latest collaboration, Polarity 3, runs just over an hour and offers ten different performances. There’s no songbook, no standards, not even a set of chord changes tying them together. These performances vary in length from just a couple minutes to a ten-minute improvisation that closes the record.

The record showcases the chemistry they’ve developed as a duo over their past records. They bounce phrases and ideas off each other, constantly pushing each other in new directions. Sometimes they come together to play in sync before spinning off in their own directions. It’s like a dance, though one without a lot of rules.

“One” opens with both artists playing long notes but soon they switch to short, wavelike patterns and circling around each other, eventually moving up and down the scale. Over eight minutes, they feel each other out: they take turns, then slowly start to play at the same time and eventually find some common ground in the last third of the track.

For the first part of the record, they move slowly, as if trying to set a tone for the evening: “Two” is a mood piece with its long, drifting notes. In “Three,” they experiment with the ranges of their instruments, quickly building up the pace and energy. The track ends with both blowing harsh bursts of sound, like a tape reel running into a burst of static.

Polarity 3 starts to come together on “Four” as they work in tandem, sometimes playing a base for the other, sometimes moving around the same ideas. When Wooley plays a rising phrase of notes, Perelman follows with one of his own, or vice versa. By the end of the performance, Wooley is playing low, buzzing notes and Perelman’s getting a nice, full-throated tone out of his tenor sax.

“Six” is another standout. They start with quick, darting movements around some high notes and eventually their playing gives the impression of two musical lines that are twisting and bending around each other, like ivy growing along a trellis. Soon the notes take on a harsher edge, with Wooley’s starting to buzz and Perelman's getting a rough, airy tone. But eventually they work back to common ground and play some bright notes in harmony.

Polarity 3 is full of moments like that and it’s tempting to say it’s like one is setting puzzles for the other to find their way out of. But that doesn’t seem quite right — this is not a partnership that feels combative or at odds. It’s more like two people working together on putting together a puzzle or shaping a piece of art. It feels collaborative in the sense that each is building on what the other’s doing, of them trying to find a shape for ideas running through their mind.

Sometimes shapelessness gives way to a feeling of sparseness and open space. The horns echo and the brief moments of silence fill the room. At others, the similarity of their two voices left me wishing they mixed it up somewhat, for instance, with Perelman switching to a different kind of horn. But then there are moments where Wooley changes the timbre of his trumpet or where Perelman works right at the lower registers of his sax, giving things a boost of color. On “Eight” he uses a mute and gives his trumpet a decidedly Miles-like tone, even if he’s playing in a radically different style than Miles ever did.

Free jazz records like this have the potential to come off as self-indulgent, with the feeling of the musicians noodling endlessly. Thankfully that’s not the case here: these two engage with each other enough that the music never feels like it’s settling down. It might be a little hard to grasp for someone new to either one, but the kind of listener who’s familiar with any of Perelman’s previous free records (Tuning Forks, The Whisperers) will like what they find here.

Roz Milner

#ivo perelman#nate wooley#polarity 3#burning ambulance#roz milner#albumreview#dusted magazine#jazz#free jazz#improvisation

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Steve Lehman Trio + Mark Turner — The Music of Anthony Braxton (PI)

Anthony Braxton’s reputation precedes him. His records can be experimental, bold, weird and sometimes all at once. He’s written scores for orchestras to play on two different planets at the same time, illustrated others with almost inscrutable drawings, and filed his work under a clinical numbering system that uses numbers instead of names: “composition #34."

They run into the 400s now, nearly as high as the number of records he’s released. For anyone new to him, it can be a challenge to find an entry point. Which makes records where other people interpret his music so valuable: they’re something of an easy gateway into a complex labyrinth.

Usually, they don’t veer too far astray: Tzadik released 2012’s Play Braxton in which three Braxton alumni (Marilyn Crispell, Gerry Hemingway, and Mark Dresser) played several of his tunes. In 2020, Cuneiform brought in the Thumbscrew trio, another set of alumni, for The Anthony Braxton Project. Now Pi Recordings has its own: Steve Lehman’s The Music of Anthony Braxton. It’s a different approach to some well-trod music, which is a good thing.

Here altoist Steve Lehman leads a quartet of drummer Damion Reid, bassist Matt Brewer and tenor saxophonist Mark Turner. This group plays through a set of mostly Braxton themes in front of a boisterous crowd in Los Angeles but also slips in two originals and a Thelonious Monk tune. In some ways it’s a very different approach to Braxton: there’s nothing here that plays chords, for one. And in Braxton’s music, a piano or a guitar is almost always at hand. And secondly, they approach the music in a straight-ahead manner, not one that gives it odd little flourishes.

The record opens with “Composition 34a” and the two horns playing a circular motif while the rhythm section swings. It opens into a fast tune where the players work around the theme and play in tandem giving the music a nice, punchy edge. Both horns take nice solos before the tempo slows down for the finish. The band also gets to stretch out on “Composition 40b,” too. Brewer opens the tune with a bass solo before leading the band into the theme. It’s another one that benefits from two horns and allows both Lehman and Turner to play lines that twist around each other before coming together for a few bars. And the tricky, stop-start rhythms of “Composition 23c” show this band opening in sync.

The two Lehman originals slot in nicely next to Braxton’s pieces. “L.A. Genes” lets the horns play complimentary lines before opening up room for solos. “Unspoken and Unbroken” starts with some playing by the horns before Reid moves into a quick, hip-hop rhythm. Both cuts are informed by Braxton’s music, but also hold their own. The set closes with the two horns dueling on opening of Monk’s hard-swinging “Trinkle, Tinkle,” which aside from showing off some nice playing helps put Braxton’s music in a context: suddenly his odd rhythms and phrases don’t feel so out of the tradition.

Throughout this record, the band’s in good shape but Reid’s playing is one difference that stands out. When compared to Play Braxton, he keeps things simple: his drumming is precise without being esoteric, swinging while staying true to Braxton’s knotty rhythms. Hemingway, by contrast, has a tendency to tap at cymbals with his fingertips and to use a light touch to create gaps in the music, making him more of an acquired taste.

But all over the record this music is played like straight-forward jazz, with a blue chip approach that never feels cold, experimental or sterile. Instead the band swings and makes Braxton’s themes come alive in a way that Halvorson, Crispell, and sometimes even Braxton himself struggle with. Recommended.

Roz Milner

#steve lehman#mark turner#the music of anthony braxton#pi#roz milner#albumreview#dusted magazine#jazz#anthony braxton#damion reid#matt brewer

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cecil Taylor Unit — Live at Fat Tuesdays, February 9, 1980 (First Visit Archive)

Over the weekend of Feb. 8-9th, 1980, the Cecil Taylor Unit rolled into Fat Tuesday’s, a jazz club at 190 Third Avenue in Manhattan. Four sets were recorded over the weekend by Swiss producer Werner X. Uehlinger, probably some four hours of music. The next year, one of these sets was released by Uehlinger’s label HatHut. And now, over 40 years later, another set has been released as Live At Fat Tuesdays, February 9, 1980, the first record on Uehlinger’s new label First Visit Archive.

This release consists of one long, untitled composition by Cecil Taylor, split arbitrarily into three tracks, and is a little over an hour of intense music: at turns it threatens to boil over, could seem at home on a classical record, or has the shouts and claps of a revival meeting. It’s not the most accessible of Taylor’s records, but then his most interesting ones never are.

The set opens with Taylor on piano, gently exploring while the percussion duo of Sunny Murray and Jerome Cooper provide a sparse backing. Soon, alto saxophonist Jimmy Lyons enters and he and Taylor go back and forth for a bit. As Taylor’s playing grows faster and more percussive, Lyons starts working on variations of the same phrase, adding little flourishes here and there. As the pace continues to build, Taylor’s energy rises and about four minutes in, he launches into his first solo of the set. You can hear him exploring ideas, sometimes going back to a passage or two between bursts. This isn’t just free jazz, but something with a larger structure in mind. Taylor’s piano occasionally bursts into fragments of sound, his energetic playing seeming to swirl around the other players and pushing him to the forefront. After a little bit, violinist Ramsey Ameen enters, sounding like he just walked in off an Albert Ayler record, his tone thin and shrill. He adds a nice dissonant streak to Taylor’s music, a counter to the pumping, rhythmic piano.

Not far into the second part, Taylor changes tack: his playing slows down and settles into a slow, almost classical style. He’s not exactly playing it straight — there’s little signature flourishes between phrases here— but he’s almost showing that he can play like Keith Jarrett if he wanted to. As his playing once again picks up and grows fragmented, Lyons reenters and trades licks. Together they build a flurry of notes, the rhythm section trailing just behind.

Later in the evening, another wrinkle emerges: someone starts to vocalize overtop of the music, almost speaking in tongues, as opposed to the poetry Taylor sometimes mixed into his music. As the tempo slows down, there’s layers of voices and hand claps and percussion, taking the music into another dimension. And as the set winds down, the voices grow stronger and more rapid, little bursts that almost mimic Taylor and Lyons playing. And finally, Taylor slows things down almost all the way, closing an intense hour of music with some slow, melodic playing.

Throughout Live at Fat Tuedsays Taylor’s playing isn’t just a mere accompaniment to his band. He never just guides things along with a well-placed chord here or there. His forceful, driving playing could be a band all in itself and acts almost like a bed for the rest of the musicians to work on top of. He occasionally guides them with a burst of playing or pushes someone forward with a low rumble from his left hand. But one could strip away everything else to just focus on him and they’d still have an engaging record.

With so many moving parts here, like the interplay between Taylor and the string section of Ameen and Alan Silva (bass, cello), or the way Lyons seems to effortlessly glide between Taylor’s flurry of notes, it can be easy to get overwhelmed on first listen. Thankfully, one can go back and relisten: an ability the audience this night at Fat Tuesday’s wasn’t able to have.

To think that this short-lived lineup was able to play with this kind of telekinesis and energy on any of these nights is almost breathtaking and makes one wish the two unreleased sets were also available to listen to. But until then, this is an essential and exciting addition to Taylor’s discography.

Roz Milner

#cecil taylor#live at fat tuesdays#first visit archive#roz milner#dusted magazine#albumreview#jazz#Sunny Murray#Jerome Cooper#Jimmy Lyons#Ramsey Ameen#Alan Silva

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fay Victor — Life Is Funny That Way (TAO Forms)

Photo by Deneka Peniston

If Herbie Nichols is remembered at all, it’s as a jazz composer and a pianist, not as a songwriter. In the decades since his death he’s carved out a small legacy with musicians like Roswell Rudd, the Clusone Trio and Misha Mengelberg recording albums with his material. These are the records that do the heavy lifting in carrying his music on; Nichols own The Complete Blue Note Recordings (Blue Note, 1997) is a bulky three-CD set that's out-of-print and goes for a premium on the secondary market.

Never a recording success in his short lifetime, Nichols paid the bills by working a variety of gigs: he taught piano, penned articles and poems for magazines, and accompanied singers. Throughout this he was writing music at an almost frantic pace: about 170 compositions, some with lyrics. And even if you don’t know Nichols’s name, you’ve probably heard his most famous one: “Lady Sings the Blues,” a song that Billie Holiday turned into a standard. When Nichols died in 1963, writer AB Spellman noted he’d never had a year where he supported himself solely on his own music.

In recent years, New York based jazz singer Fay Victor has developed her interest in Nichols music with her Herbie Nichols SUNG project. Life Is Funny That Way is the result of these years of work: she’d added lyrics to a set of Nichols’s songs, fleshed out arrangements on others. Over 11 performances, she’s backed with a jazz quartet and brings this music — some of it never recorded in Nichols’s lifetime — to life.

It opens with “Life Is Funny That Way,” a song starting with Victor and sax player Michaël Attias together. When they get to the chorus the band joins in with a nicely swinging groove. Immediately you can hear the chemistry between Attias and Victor: they almost play in unison, his notes mirroring her singing. The other players (Anthony Coleman on piano, Ratzo Harris on bass, and Tom Rainey on drums) create a nice backing for Attias and Victor to branch out on.

Conversely, Coleman and Harris are all but absent on “The Bassist.” It opens with an understated drum solo by Rainey: light rolls, gentle cymbal taps. He builds up until Victor and Attias join in together, again acting as two leads that are mostly playing in sync. But when Victor starts scatting, her and Attias start trading riffs and playing off each other.

Occasionally, the band slows things down to a crawl, giving Victor a chance to stretch out and sing a slow ballad. “Bright Butterfly” has Harris bowing his lines, giving a thick and fuzzy background for Attias and Victor. “The Culprit Is You” has a similar approach, but with Coleman’s sparse piano and little pushes by Rainey’s drumming. It lends this performance a nice smoky, late-night vibe where you can almost see the spotlight closing tight onto Victor as she stretches her notes. And on “Lady Sings the Blues,” Victor’s voice has a bright, almost warm quality as she leans into Billie Holiday’s lyrics.

The band occasionally gets a chance to shine too. Late in the record, they play “Twelve Bars” as a slow mood piece, with Coleman bouncing around his piano as the rhythm section whips up a swirl of noise behind him. It’s one of the more angular pieces here, showing Nichols’ more outside style. He wasn’t just a straight ahead bop pianist.

Life Is Funny That Way offers a nice primer on Nichols: music that’s alternately challenging and straight ahead, close enough to the tradition to seem familiar with enough twists it can catch you off guard. It’s a good way to dive into his music. Let’s hope Victor’s project isn’t a one-off.

Roz Milner

#fay victor#life is funny that way#tao forms#roz milner#albumreview#dusted magazine#herbie nichols#vocal jazz#jazz

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

BELLIGHTNING — Page of Pentacles (Eukaryotic)

A new trio of Katie English, Mark Kluzick, and JA Adams, BELLIGHTNING has emerged with their debut EP Page of Pentacles. The short, seven-minute EP is built around the title track which was originally written for a project that never saw completion. Rather than let it go to waste, this trio wrote a handful of pieces to surround it, none more than a minute long.

Which leaves listeners with an EP built of miniatures and one long (by comparison) piece. The ideas aren’t fleshed out and often resemble little more than sketches. But in the context of an abandoned project, it gives Page of Pentangles the feeling of what could’ve been: the swirling, almost sea-sick string lines, the harsh, mechanical ambient electronic sounds, the flute, moving effortlessly between these two, and on “Shilling” layers of saxophone that seem to pile up on each other.

And in the middle, the dark and moody title track. It’s a tense, slow burning piece with churning strings, circular motifs coming from English’s flute, and gentle backing from Kluzick’s accordion. At times it reminds me of George Crumb or John Zorn’s string quartets, at others of Nurse With Wound’s more ambient soundscapes (Soliloquy for Lilith, Salt Marie Celeste), thanks to Adams’ electronics.

While the original album remains unrealized, this short and concise EP introduces BELLIGHTNING as a trio worth keeping an eye on.

Roz Milner

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Zorn/The JACK Quartet — The Complete Quartets (Tzadik)

youtube

Over the last 40-something years, John Zorn has worked in many styles: there’s the punkish energy of Naked City and punishing grind core of Pain Killer, some 25 volumes of soundtracks, high-wire jazz with Masada, and the many, many side groups he’s composed for (Moonchild, Chaos Magick, a bunch of others that don’t have names). Classical is style that doesn’t immediately come to mind. After all, most of his music has at least one foot in jazz and improvised music.

But as the new two-CD set The Complete Quartets shows, Zorn’s also had an interesting side career writing for the traditional string quartet. The eight pieces here comprise just over 35 years work in this field and show him growing and coming into his own. Sure, it’s a lot to take in all at once, but we’re talking about a guy who loves to do things in bulk. Zorn’s been as prolific as just about any other musical artist you can name.

The four pieces on disc one are some of Zorn’s first pieces for string quartet and they’re also his most familiar ones, too. “Cat O’Nine Tails” was first recorded over 30 years ago by the Kronos Quartet and in the years since, Tzadik has released a couple of records focused on these pieces: 1998’s The String Quartets and 2000’s Cartoon/S&M. But the music on disc two isn’t as well-travelled and where some of this set’s interest lies. It’s largely harder to track down and hasn’t been put into this kind of a context yet. First things first, however.

“Cat O’Nine Tails” was written in 1988 and was Zorn’s first major piece for a string quartet. It still feels wild in the way it jump cuts from bursts of dissonance to little bits of music: at times it sounds like George Crumb and at others like a country hoedown. It feels like a needle jumping haphazardly on a turntable. The way the JACK Quartet moves around inside this is of a piece with Zorn’s other late 1980s ideas: the frantic blasts of Spy vs Spy, the sonic miniatures of Naked City, the quick cuts of his soundtrack work. But they also give an idea of his creativity: he’s exploring the language of the string quartet and creatively misreading his influences.

Indeed, you can hear Zorn working out this language on the first disc. “Dead Man” opens with choppy plucked strings. Zorn works out his voice in the little bits of noisy scratches and the way the strings sometimes sound like a tape unspooling during playback. The quartet handles these tricky passages well, moving through the piece’s 13 sections (presented here as one long track) with aplomb. It’s a short one, but you can hear echoes of this piece’s softer side throughout the rest of the record, particularly in “Memento Mori” and the way the notes sometimes hang in the air, slowly turning into a drone. It’s the longest piece on the set and even if it feels a little too rambly at times, the group handles its quieter passages well.

The first disc ends with “Kol Nidre,” a slower and more melodic composition that’s a change of pace from the set. It moves around two themes that revolve around each other, giving the music a sort of throbbing quality. It’s short, the shortest piece on the record but in some ways it’s the most memorable in its more reflective and emotional passages and the way it shows Zorn working in a different mode, something closer to, say, Phil Niblock. It closes about a decade of his creative growth in this form.

The second disc takes up Zorn’s post 2000 string quartet works. It’s a period where he increasingly turned to others to play his works and started releasing those huge box sets: The Book of Heads, The Bagatelles, The Book of Angels. Comparatively, his work for string quartets slowed down with just four pieces in the last 25 years. Of them the first is the most memorable: the five-part “Necronomicon.” It opens with bursts of energy, particularly in the higher registers, and is livelier than either of the two pieces before it. But after this bombastic intro it moves into a slow, moody mode on “The Magus” and builds up the tension with drawn out notes followed by short little buzzes. The whole piece has the ambience of a soundtrack to a horror movie. You can almost see the wizard working deep inside the castle, stirring up trouble and coming to a frantic, grizzly fate by the end of the fifth movement. In the JACK Quartet’s hands, this piece comes alive and draws you in. It’s the best part of this set.

The final two pieces lack that creativity and ambition. “The Unseen” swirls around little riffs and motifs, while “The Remedy of Fortune” draws on older forms of classical music and has moments of tension, but doesn’t have the same spark. They’re both nice to have, but neither are essential.

But stuck between those and “Necronomicon” is 2011’s “The Alchemist.” According to Zorn, it was inspired by a 16th century occultist/astronomer with an interest in Kabbalah, which honestly tracks with Zorn’s history of influences. It’s a busy piece that would fill a whole side of a vinyl record, but it has some interesting moments where the strings seem to swirl around each other, rising and falling. But there’s a really cool moment about six minutes in where everything drops out except for some ringing high notes and it completely changes the mood of the piece, taking it into spaces where Zorn hasn’t really gone on the other quartets. It’s one that could’ve been easily lost in a larger set but here, placed against his other later works, it shines.

With many albums of his classical music out there already, it’s hard to recommend The Complete Quartets to people newly coming to his classical side. Safer bets are 1999’s The String Quartets or 1996’s Bar Kokhba. But those with a deeper interest in Zorn and an interest in seeing how his compositions grew from collections of miniatures and ideas to more fully fleshed out pieces, will find a lot here to chew on. And throughout the JACK Quartet show themselves as able players for the sometimes tricky music.

Roz Milner

#john zorn#the JACK quartet#the complete quartets#tzadik#roz milner#albumreview#dusted magazine#contemporary classical#string quartet

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ginger Root — SHINBANGUMI (Ghostly International)

Photo by Cameron Lew

The latest Ginger Root record has multi-instrumentalist Cameron Lew diving deep into retro sounds, drawing inspiration from Paul McCartney, Yellow Magic Orchestra and other pre-internet vibes. It’s a well-constructed LP and one with the flow and pace of a concept record, but it’s also one that sticks to a formula.

Things kick off with “No Problems,” a slice of McCartney-esque pop with warm keyboards, touches of strings, and a thin guitar tone that twangs like a rubber band. Lew builds an emphasis on the McCartney II, early 1980s ambience: the analog synths, the way everything sounds like it’s been built by overdubbing one instrument at a time, or how it feels like it’s old without actually being old. This sort of not-quite-nostalgia is all over SHINBANGUMI, and “No Problems” does a great job of setting the scene for listeners.

Lew’s a musician who wears his influences on his sleeve, and throughout the first half of the record you can almost make a checklist of what he likes by the way each song sounds: “Better Than Monday” has a slinky, almost mechanical funk groove that recalls Yellow Magic Orchestra, while “All Night” has a driving, bass-led groove straight out of a vintage city pop record by Tatsuro Yamashita. And “Giddy Up” throws in a vaguely tense sort of energy that lands somewhere between solo McCartney and Todd Rundgren. When Lew’s at his best on songs like these, he makes music that’s engaging and fun.

But when he errs, it grinds the album to a halt. “Kaze” is a curveball that sounds like an odd, almost-listing sort of lounge music. Tonally it doesn’t really match what else is happening here: there’s little rolls of percussion and it builds into an uneventful climax. It feels like it’s from a completely different record and it disrupts the flow he’s been building up.

Throughout SHINBANGUMI, Lew hides his voice behind filters and it’s occasionally hard to make out his lyrics when he’s shoved to the back of the mix. He isn’t a strong singer or especially a wordsmith, but his singing almost feels incidental to the music here. This is a record that’s big on pop hooks and funky basslines. And perhaps a plot of some kind, too. Lew’s released a series of connected videos for this that suggest it’s a concept record following a TV executive in 1980s Japan making his own network. The plot feels loose and sort of incidental to the lyrics, but the way this album flows does have a feeling of a storyline, right down to a climax on “Show 10” and a coda on “Take Me Back.” Those two close the album out with more lush city pop grooves, touches of sax and strings, and carefully placed splashes of keyboards.

The thing about a record like this is that you almost know the game plan from the album’s lead single. Lew sets the template early: lots of old sounding keyboards, basslines that move all over the rhythm, and a vocal template that keeps his voice almost buried. Aside from a couple of curveballs and a few short interludes, he never really strays from that model. It’s an album that if it catches you right away, it’s probably one you’ll enjoy all the way through. But if you’re expecting it to build into something or for him to explore a wide palette of sounds you’ll be left wanting. As they say on TV: viewer discretion is advised.

Roz Milner

#ginger root#shinbangumi#ghostly#roz milner#albumreview#dusted magazine#pop#paul mccartney#yellow magic orchestra

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Kaplan — 3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, and the Lost Empire of Cool (Penguin Press)

There are two or three jazz albums almost everyone seems to have: Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, and Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue. The first two records were well received on release, but not so much Davis’s. It wasn’t only a departure from the kind of music he played at the time, but seemed out of step with what everyone else was doing, too. And yet it’s taken on a life of its own, becoming if not the most talked about jazz record ever, then certainly the best-selling.

Enter James Kaplan, a biographer best known for his two-volume book on Frank Sinatra. In 3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, and the Lost Empire of Cool he turns his focus onto Kind of Blue and the confluence of three jazz icons: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Bill Evans. However 3 Shades of Blue doesn’t live up to its potential and ultimately feels like an unnecessary retread of familiar material.

Kaplan opens the book in the 1980s, with Miles Davis playing auditoriums and ordering Wynton Marsalis off his stage. Kaplan himself enters, a young journalist for Vanity Fair, who lands an interview with the trumpeter, and two hit it off. From there he goes back in time to Davis’s early years and then mixes in Coltrane and Evans — but it’s Miles who is the book’s center. This has its benefits and drawbacks: he’s a more compelling figure than Evans and he lived longer than the book’s other two principals. But he’s also the most written about, too, and Kaplan has a hard time bringing anything new to light. So instead we get the familiar stories about him gigging with Charlie Parker, getting in trouble with the law and spending the late 1970s getting high in his brownstone. Same with Coltrane’s obsessive practicing and dental woes, and Evans’s heroin addiction.

Possibly the only new information comes from Kaplan’s suppositions about his subject’s inner feelings. For example, Kaplan suggests that Davis was sexually interested in Evans: “his all-American good looks and professional intensity were attractive to women — and to Miles Davis.” Why? Because Davis once put his arms around Evans while he played piano, a move Davis also pulled on Red Garland. Kaplan doesn’t think Davis felt similarly with Garland.

Indeed, 3 Shades is sloppy. It could useanother once-over by an attentive editor. Kaplan occasionally derails his narrative with odd asides about Frank Sinatra or by repeating points he made earlier in the book. At one point he goes off on a tangent about a 1980s photo of Davis in a section set some 30 years previous. Elsewhere he’s careless about sourcing quotes: on one page he quotes pianist Jon Batiste on Evans’s use of touch, then inserts a lengthy block quote about Evans’s playing. But the second quote isn’t Batiste. It’s from a biography of Evans by Peter Pettinger, a fact readers would only notice if they search Kaplan’s endnotes.

In some ways, 3 Shades feels like a rush job but one without a specific anniversary in mind. In others, it feels overlong and rambling: one doesn’t need a garish description of Davis in the late 1970s in a book nominally about a record from 1959. In others it feels more like him remembering his encounters with Davis, both on record and in person, than a proper biography of any of these three musicians.

But it’s not so much that the book doesn’t know what it wants to be, it’s that it doesn’t need to be here at all. People new to Davis, Coltrane or Evans will find a lot of information here, but those who already know them won’t find anything not already in other biographies by Ben Ratliff, Pettinger or Quincy Troupe. And newcomers will find those a more linear, less convoluted read to boot.

Roz Milner

#james kaplan#3 shades of blue#miles davis#john coltrane#bill evans#penguin press#roz milner#bookreview#dusted magazine#jazz

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chris Forsyth — Plays Love Devotion Surrender (Bandcamp, 2024)

The golden anniversary of John McLaughlin and Carlos Santana’s 1973 record Love Surrender Devotion passed last year without much fanfare: no deluxe reissue or archival release from a short-lived supergroup of sorts. It instead remains one of the lesser explored chapters of McLaughlin’s long career.

Which isn’t to say it’s overlooked or under appreciated. The jam-heavy album of hard driving fusion has found fans over the decades, most notably guitar hero Chris Forsyth. At last fall’s Philly Music Fest, Forsyth headed a band that replayed the album in full for a packed crowd at Solar Myth. He was joined by guitarist Nick Millevoi, a rhythm section of Douglas McCombs, Mikel Patrick Avery and Ryan Jewell, plus Brent Cordero on electric organ. And not too long ago he made this set available for purchase on his Bandcamp.

Throughout Love Devotion Surrender, Forsyth and company don’t stray too far from the original. It’s the same material, roughly in the same order: the last two tracks are flipped, but it works to give this record a bombastic finale instead of the muted coda on the original.

It opens with John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme” and a burst of sound before the band settles into Coltrane's familiar intro. Forsyth’s guitar has a sharp tone that squeals and sounds like he’s pushing his amp to its limit. His playing is fluid and moves between longer notes and quick little flurries — a departure from McLaughlin’s machine gun-spray of notes on the original. Meanwhile Millevoi chugs along on rhythm guitar behind him with a choppy, wah-heavy tone. After a while they trade off and Millevoi steps up for a solo of his own, the two of them building up into a frenzy of dueling leads playing off each other. After about ten minutes the pace slows down a bit and they both settle into playing the iconic Coltrane riff. It’s an effective way to open the record, grabbing your attention and setting the mood of a night of guitar frenzy.

The band then moves into “Niama,” another Coltrane number. But this is the first step away from the record: where McLaughlin and Santana played this acoustically, with a bit of a Latin tinge, this band plays it a slow electric blues. The guitars draw the emotion out of this one as Cordero’s organ gives them a bed of sound to work on top of. It segues nicely into McLaughlin’s “A Love Divine” which builds up slowly from Cordero’s droning organ and bursts of percussion from Avery and Jewell. Both the guitarists slowly work their way into this one but before long they’re playing a flurry of notes as the rhythm section builds up the tension by playing the beat faster and faster. The whole band works itself up into a lather, finishing this one with blasts of cymbals and squealing guitars while McCombs keeps them on track with his bass.

Next comes the second wrinkle of the night: the band swaps the order of “Meditation” and “Let Us Now Enter the House of the Lord” while also changing the first to another slow electric blues from a sparse acoustic theme. With Cordero’s organ and McCombs bass holding the groove down, both Forsyth and Millevoi take their time to play around the chorus and trade off short solos. It’s actually one of the set’s more approachable moments and wouldn’t feel out of place on a Solar Motel record.

They finish the evening off with “Let Us Now…” which is a fitting bookend with “A Love Supreme.” They’re both lengthy performances where the guitars trade off riffs and are played something like spiritual jazz fusion opening with flurries of notes and drum rolls. It evolves into a vaguely Latin groove for the two guitars to solo over and eventually to jam in unison together.

The thing about a record like this is that for all the guitar heroics it doesn’t quite have the same spark as the original. There, both Santana and McLaughlin were going for a spiritual vibe, playing hard and fast like they were trying to lose themselves in the music and push into something spiritual. Indeed, bootlegs of this band on their short tour show them regularly pushing songs past the 20-minute mark. That was a group reaching for ecstasy.

By contrast, you never get the same feeling from Forsyth and company here. As good as their playing is, you know they’re playing tribute to a record instead of trying to catch the same religious feeling. It’s not really a bad thing, it just means they’re playing it a little safer and closer to the vest even when they work themselves up into a frenzy.

As far as tributes go, Plays Love Devotion Surrender doesn't mess with the gospel and anybody who loves guitar-heavy jamming will enjoy this. While it might not completely work for people unfamiliar with the original record or those without the patience to sit through long guitar workouts, fans with worn out copies of the original will have a lot here to chew on.

Roz Milner

#chris forsyth#plays love devotion surrender#roz milner#albumreview#dusted magazine#john mclaughlin#carlos santana#nick millevoi#doug mccombs#mikel patrick avery#ryan jewell#brent cordero

3 notes

·

View notes