#roy de navarre

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

King Henry IV of France. By Frans Pourbus the Younger.

#frans pourbus#frans pourbus the younger#royaume de france#henri iv#roi de france#henri iii#roy de navarre#roi de france et de navarre#vive le roi#maison de bourbon#vert galant#kingdom of france#house of bourbon

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The last kings and queens of the Capetian dynasty.

#royaume de france#capétiens#vive le roi#vive la reine#Philippe IV le Bel#Jeanne Ire#reine de navarre#louis x#comte de champagne#Clémence de Hongrie#Philippe V le Long#Jeanne II de Bourgogne#charles iv le bel#Jeanne d'Évreux#engravings#royalty#les rois maudits#maurice druon#champagne#roi de navarre

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

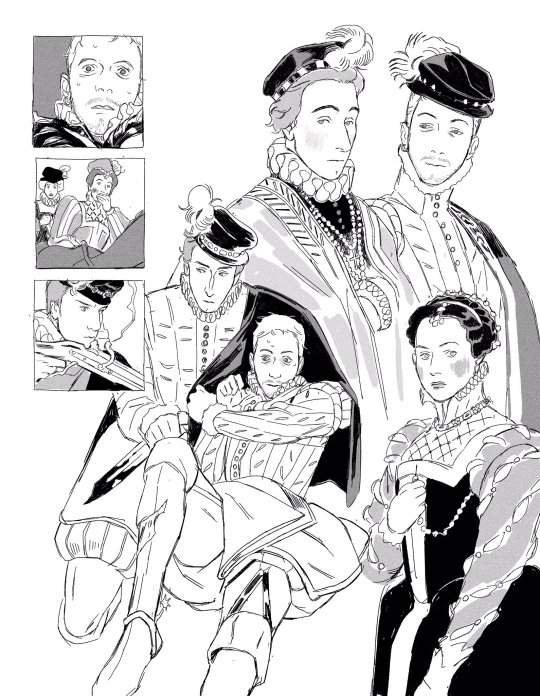

La Reine Margot - Charles IX, Henri de Navarre, and Marguerite de Valois

I.III - Un roi poète

I.XXXI - La Chasse à Courre

II.IV - La Nuit des Rois

#La Reine Margot#Alexandre Dumas#Charles IX#Henri de Navarre#Henri IV#Marguerite de Navarre#new obsession just dropped welcome to the era#Charles is callous and sickly and pathetic so naturally he's a blorbo#he can excuse religious war crimes but he draws the line at his sexy cool protestant brother in law ♥️#i havent even designed the main gays of this book...it has so much to offer#16th century#my art

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Exiled Queen Marie de Medici with Coronet Overlooking Cologne

Artist: Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599–1641)

Date: c. 1631

Medium: Oil on canvas

Collection: Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille, France

Marie de' Medici

Marie de' Medici (French: Marie de Médicis; Italian: Maria de' Medici; 26 April 1575 – 3 July 1642) was Queen of France and Navarre as the second wife of King Henry IV. Marie served as regent of France between 1610 and 1617 during the minority of her son Louis XIII. Her mandate as regent legally expired in 1614, when her son reached the age of majority, but she refused to resign and continued as regent until she was removed by a coup in 1617.

Marie was a member of the powerful House of Medici in the branch of the grand dukes of Tuscany. Her family's wealth inspired Henry IV to choose Marie as his second wife after his divorce from his previous wife, Margaret of Valois. The assassination of her husband in 1610, which occurred the day after her coronation, caused her to act as regent for her son, Louis XIII, until 1614, when he officially attained his legal majority, but as the head of the Conseil du Roi, she retained the power.

Noted for her ceaseless political intrigues at the French court, her extensive artistic patronage and her favourites (the most famous being Concino Concini and Leonora Dori), she ended up being banished from the country by her son and dying in the city of Cologne, in the Holy Roman Empire.

#portrait#marie de' medici#queen of france#seated#costume#crown#table#house of medici#tuscany#cologne#coronet#woman#european#french history#oil painting#anthony van dyck#flemish painter#baroque style#artwork#european art#17th century painting

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

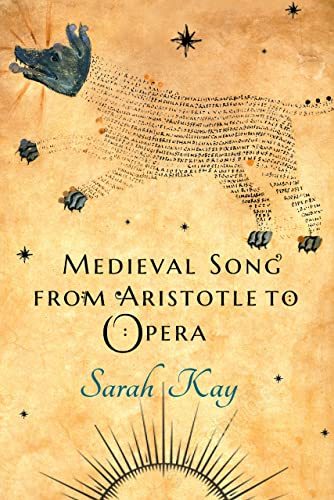

Medieval Song from Aristotle to Opera

This book is an interdisciplinary exploration of music and sound with a focus on medieval songs. In the introduction, the author explains how the new interdisciplinary field of sound studies along with her view of song as anachronic (something from a later time period that is transferred back to an earlier one) has led to the interesting title of the book. Its intended audience is scholars in the areas of musicology, sound studies, medieval music, and philosophy.

Sarah Kay is a prolific writer on medieval European literature and the arts. The concept of song as logos and phone (text plus music) is most apparent in medieval song, where not only the performance of the song but its presentation in the manuscript along with the specific musical notation and performance venues all intertwine to go beyond song into how imaginary animals and real animals presented in the songs might have sounded. Given that modern-day scholars can only guess at what and how medieval song may have actually sounded like in performance and how that performance would have been internalized or analyzed by those who heard it, the author explores many interesting threads in the book such as singing as the paradoxical conjunction of touch and thought, song’s association with animal breath and soul, and the specific example of the siren and siren song as presented in medieval song manuscripts. The anachronic exploration of reading medieval song operatically becomes a focus throughout the book as well. The section in the introduction called “Reading Medieval Song Operatically” is an example of this anachronic analysis.

Chapter One looks at the concept of touch and thought in Guillaume de Machaut’s "Remede de Fortune" and its description through music, text, and manuscript illustration, including how the concept of touch is exemplified in Boethius’s On the Consolation of Philosophy to the touch of the Muse in late antique society up to Hope’s touch and the touch of love in the songs of the troubadours and trouveres. Chapter Two examines the concept of the voice as light in such songs and texts as the alba “Reis glorios” by Giraut de Bornelh and the Marian hymn “Domna dels angels regina” of Peire de Corbian.

Chapter Three focuses on the breath of beasts and the ecologies of inspiration in troubadour lyrics and songs such as Nicole de Margival’s "Dit de la Panthere" and Machaut’s "Dit dou Lyon," where the panther and the lion and the concept of the pneuma in medieval philosophy are discussed. The author brings her expertise in ancient and medieval philosophy, depictions of these concepts in medieval illuminated manuscripts, and concepts of air and breath along with colored plates and charts to illustrate her train of thought on these interesting threads, tangents, and trails which bring all these concepts and examples together. Chapter Five discusses a specific imaginary creature, the siren, and its death-luring song, using Machaut’s "Jugement dou roy de Navarre" as an introduction, moving to sirens in medieval singing and operatic representations, up to their depictions in medieval illuminated manuscripts such as the Queen Mary Psalter, Troubadour Book M, and various other medieval songs. In Chapter Six, on imagining hearing song, there is more examination of various troubadour and trouvere medieval songs related to sound and its performance, reception, sensing, and imagining. A short essay on the loss, retrieval, and future of medieval song in scholarship today closes the book.

Kay is Emerita Professor of French Literature, Thought, and Culture at New York University. Some of her previous books include Animal Skins and the Reading Self in Medieval Latin and French Bestiaries (2017) and Parrots and Nightingales: Troubadour Quotations and the Development of European Poetry (2013). One of the most exciting additions to Medieval Song from Aristotle to Opera is its companion website, which contains audio and some video recordings of the songs in the book with complete texts and translations, performance scores, and chapter-by-chapter performance reflections. It is a must for readers to go through this companion website in order to hear and see how the author’s concepts and impressions of these medieval songs are imagined and performed. This book is definitely aimed at experienced scholars; readers unfamiliar with this topic would benefit from learning some fundamental knowledge about this field before preceding.

Continue reading...

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The myth of Medea (2)

Next article, following a chronological order, is “Medea, from the 16th to the 18th centuries”, written by Patrick Werly.

During the Middle-Ages, Medea is depicted in several tales. Benoît de Sainte-Maure’s Roman de Troie, in the middle of the 12th century; Guillaume de Loris and Jean de Meng’s Roman de la Rose, in the 13th century; the anonymous Moralized Ovid of the 14th century ; the Jugement du Roy de Navarre by Guillaume de Machaut in the 14th century, etc…

Between the 16th and 18th centuries, Medea was mostly encountered on theater stages and within operas, in works that are more inspired by the tragedies of Seneca and Euripides, rather than by the Metamorphoses of Ovid. However, there was an effort of appropriation to be made: indeed, the myth of Medea the Scythian, of Medea the Barbarian, part of the classical works of Antiquity, was at risk of ruining the moral values and the aesthetic system that Europe had imposed upon itself. As such, a “displacement” of the figure was required. Three main authors have to be considered: Calderon de la Barca, Pierre Corneille, and Thomas Corneille as the librettist of Marc Antoine Charpentier.

I/ The allegorical reading

The authors of the 17th century mostly found their sources in a mythology manual that had been published in 1552 by Noël Conti (or Noël le Comte, in Latin Natalis Comes, 1520-1582), and which was titled: “Mythology, or the explanation of fables, containing the genealogies of the gods, the ceremonies of their sacrifices, their deeds, their adventures, their loves, and almost all of the principles of the natural and moral philosophy”. Corneille used it to write his Conquête de la Toison d’Or, Caderon also probably used it for his El divino Jason. The seventh chapter of the sixth book is dedicated to Medea: after retelling the myth, Noël Conti presents the “physical mythology”, then the “moral mythology”. In both cases, the process it to try to use the myth for the moral edification of the reader, through mean of the allegory. As such, the reason behind the “dissection and death of Medea’s brothers and children” is because she wanted to put behind her appetite and concupiscence: “if someone let themselves we trapped by the slimy nets of unreasonable pleasures of the flesh, of greed, of cruelty; then it is to no surprise that good advice and counsel climbs on its chariot and flies away in the sky with winged dragon”. According to the etymology offered by Noël Conti, and that Calderon will reuse, Medea is “the advice”, “the counsel”, that is to say, the scholastic tradition, the wise decision, the choice made after a deliberation. The mythographer is aware of the negative image of Medea: but it does not matter if she is good or evil for, in the tradition of the Moralized Ovid, Medea needs to have a usefulness for the moral and religious domains. “Whether we take Medea to be advice and prudence, or to be a very wicked and malevolent woman, the Ancients, through this Fable, intended to shape us and lead us to probity, and to the integrity of the mores”. This is the moral lesson we must keep: the violence of the myth is transposed for the benefit of virtue.

This allegory can be found in the self-sacramental El divino Jason, composed in 1634 by Calderon de la Barca (1600-1681). In this play, the allegory is explicitly Christian since Jason is the Christ, Hercules saint Peter, Orpheus saint John the Baptist, etc… The fleece represents the soul, the one of a lost sheep which fled from the herd of the Christ and that Jason is thus looking for. But the quest of Jason is a dual one, because the soul is also depicted by Medea, which is also the allegory for Gentilism. Jason says of her: “Medea, who means / Advisor and Knowledgeable in all / was once the Gentilism / which offered itself to the superstitious rites / of magic / and to its idols which are but air / smoke, dust and nothingness”. The task of Jason is to bring Medea with him on the Argo ship to take her away from the land of Colchis, but also to free her from the influence of Idolatry, an actual character of the play, which embodies the religion and the pagan wisdom of the Antiquity.

When Medea encounters Jason for the first time, on the shores of Colchis, she decides to simulate her love (“Amor le pienso fingir”), but Jason tells her he only came here to love her (“Vengo a amarte”), and then Medea is caught by her own trap, and falls in love truly (“Pensaba fingir amores / y va verdaderos son”). When she offers herself to Jason, she also offers at the same time the Fleece that he came here to seek (“Digo que de amores muero ; / tuyo sera el vellocino / que buscas, Jason divino”).

Follows a strange scene in which Theseus (here, saint Andre) pronounces a long, poetic speech filled with proper names (those of the Argonauts, of Medea, of Idolatry), with names of flowers, of colors, of virtues. Each, when they hear their name, or the name of their flower, color, virtue, answers Theseus. Medea chose the clover (a leaf without a flower, which makes a beautiful border for others’ bouquets), the color green, and the virtue of Hope. In this long passage, a baroque chorus presents the union of Medea to Jason as her union to Christianity, as well as her rejection of Idolatry (“No quiero / seguirte mas, fero monstruo / Oh, como y ate aborezeo!”)

Jason, to redeem the mistakes of Medea, will undergo the trial of taking the Golden Fleece away from its tree (which is also the Tree of Adam). At the top, he replaces the Fleece with a Lamb which bleeds, and whose light blinds and strikes down Idolatry, while Hell opens up below her. Calderon did not stage in any way the magical powers of Medea: here, she is only a sorceress by reputation. Magic is only due to the characters of the Idolatry, and of the King (which represents the World), but it is powerless against the Argonauts led by Jason. What replaces magic in terms of supernatural effects, is the miracle, the one that Jason accomplishes. In the dramaturgy of the play, the actions that go beyond the power of man are not those of magic, but those of religion, the one to which Medea converts herself. In this allegory, the barbarian, the wizardess, abandons all of her attributes to follow the pastor-Jason. The sheep found back its flock, the soul now belongs to the Church.

II/Medea as a victim

Médée is the first tragedy of Pierre Corneille, which was played during the season of 1634-1635. The play is already a work part of the classical canon (the author tries to respect the unicity of location, time and action), but it does not respect the rule of “bienséance”, since we see dying on stage the king and the princess. Corneille, in his letter-preface to his play, explains that poetry often makes “beautiful imitations of actions we should not imitate”, and he plays on the two meanings of the verb “imitate”. But it is also a trick of Corneille to keep the moral safe. Indeed, the actions of Medea can be explained by the fact that she is victim of a political conspiracy; it is an explanation that allows to rationalize her actions, and thus judge them by the light of “common reason”. Jason, the man that she loves, presents himself as such: “Thus I am not one of those vulgar lovers / I adjust my flame to the good of my businesses / And under whichever climate fate would throw me / I will be in love by State maxim” (I,1). And Creon, the king, talks about Egeus, who originally had to marry Creusa before she was promised to Jason: “Whichever reasons of State might satisfy him” (II,3). Marriage is thus placed under the sign of the “reason of the State”, of which Medea is the victim. She pleads her cause by herself in these words: “Anyone who condemns a criminal without hearing them / Even if they deserved a thousand times their punishment / Turns a just sentence into an injustice” (II,2).

Corneille thus introduced a judiciary dimension to his play: Medea was condemned to exile for the murder of Pelias, but she was not properly put on trial. She becomes the victim of Creon’s tyranny. But beyond her, it is all of her family, an entire dynastic branch that is victim of a tyrannical power. Indeed, Medea is the grand-daughter of the Sun, and if Jason marries Creusa, their children will dishonor the dynasty: “You will mingle, impious one, and put on the same rank / The nephews of Sisyphus and those of the Sun! / […] / I will gladly prevent this odious mixing, / Which dishonors together my family and my gods” (III,3). As such, the series of crimes is explained: Creusa’s death prevents the misalliance, while the death of the children both suppresses radically the cause of the dynastic troubles while also hurting Jason. Medea answers to the conspiracy created “by reason of State” by what was called in the 17th century a “coup d’Etat”, a premeditated act conceived in secret and that goes beyond common law. This coup d’Etat is here placed on the mythological terrain of magic, as Louis Marin analyzed. Pierre Corneille seems to be so far the only author to have turned the murder of Medea into a political act – the 20th century also made the myth politic, but in a different context.

Corneille wrote another play which features Medea: La Conquête de la Toison d’or (1660). Medea the sorceress is here also a garden architect: the setting of the first act is a French-style garden, seen in perspective, and the character of Absyrte reveals that it was conceived by Medea’s art, the only one able to create such a beauty in a savage and hostile nature. Magic is here linked to the laws of geometry ; but it can be vanquished by the laws of love, such as in the twelfth Héroïde of Ovid, or to be more precise by the superior power of love. Medea says to Jason that she cannot help but love him despite his treachery: “Are you in my art a greater master than me?” (II,2). This art, she later says to her brother Absyrte, “if it has on all else an absolute power / Far from charming hearts, it doesn’t see anything in them” (IV, 1). Thus, the tragedy exposes the limits of the power of Medea: we are far away from the supreme power of the 1635 tragedy.

III / Medea in the opera: the embodiment of division

In their 1693 lyrical tragedy Médée, Marc-Antoine Charpentier and Thomas Corneille use, just like Pierre Corneille did before them, Seneca as their main source, but their opera is not concerned with the political dimension of the tragedy. What is rather important here is to gather around the character of the sorceress the most spectacular elements. We see Medea, helped by demons, by Vengeance, and by Jealousy, preparing in a cauldron the poison that will kill her rival (III,7). We see the guards of the king trying to seize Medea, but turning their weapons against each other before seizing Creon, and finally leaving to pursue “ghosts with the shape of pleasant women” (IV, 7). At the end of the fourth act, the earth opens below Creon, and he sees Medea in the waters of the Styx, while the orchestra is divided into two very distinctive groups of instruments. A same motif recurs in those scenes, like a choreography: the idea of division and separation. The guards are divided by fighting against each other, then they turn against the king they receive order froms, then the earth splits open… Medea is the one who separates, she is the creator of strife and discord. In III, 4, she says about herself and Jason “And may the crime separate us / As the crime joined us”. In the final scene, after killing her children, she claims to Jason: “Unfaithful! After your betrayal / Should I have seen my sons in the sons of Jason?”, a sentence in which the “us” disappears for the “you”, and where Medea dissociates herself from her children.

But Medea herself is divided. As the king kills himself, she is herself fractured. In the scenes IV, 5 and V, 1, she deliberates about the murder of her children, and this deliberation (in a typical 17th century fashion) is divided, as much on a semantic level as on a musical one. When the oscillation of the wizardess’ mind makes her regret her decision, we hear a slow, deep, internal music of cord instruments ; but when she is resolved to commit her crime, the tempo becomes faster and the clavecin dominates. The two rhythm finally converge when she takes her decision, because her doubts are only there for a theatrical effct. Medea is still Medea (“When you boast of being king / Remember that I am Medea”, IV, 6), as she was with Seneca (Nunc sum Medea) and as she was with Corneille (“Madam, I am queen / - And I am Medea, Conquête, III, 4).

In the genre of the opera, other pieces of note include Il Giasone (1649) of Pier Francesco Cavalli, and Medea (1797) by Luigi Cherubini, on a French booklet by François Benoît Hoffmann, where Medea switches between supplications and threats, in a role that was made famous in the 20th century by Maria Callas.

IV/ Medea in paintings and drawings

Jean-François de Troy (1679-1752) painted, for an Histoire de Jason in seven pieces by the Gobelin manufacture, a Médée enlevée sur son char après avoir tué ses enfants (1746). This is an episode taken from the seventh book of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and Ovid will indeed be the main source of painters, rather than Euripides or Seneca. Medea, on her chariot pulled by two winged dragons, has a cold, hateful stare. In one hand she holds her magic wand, with the other she points towards the body of her two dead children. Jason is trying to pull out his sword while a soldier restrains him. In the background, Corinth and Creon’s palace are burning. Two small Cupids are behind the chariot. One is breaking his bow with his knee, the other is ripping off his blindfold. This detail explains the meaning of the scene, its allegory: the two little gods of love refuse their own power, upon seeing the devastation of love when it turns into a jealousy-fueled hatred. Or maybe should we understand the message as: if such a disaster is to be avoided, love must stop to be blind. All in all, the depiction of the myth of Medea must have a moral purpose: love must be much more aware and conscious, and it should be treated with logic and reason.

To find back the tragedy and the violence of the antique myth, we must look at two drawings of Poussin from around 1645, the second being a cleaner variation of the first. The scene depicts Medea killing her second child: she holds the child naked, by the leg, his head upside-down, and she raises her arm to hit his heart with a dagger. The first child is dead on the floor, and a terrorized woman, crumpled near his body, turns herself towards Medea to stop her. A bit above, separated by a balcony, unable to stop her, Jason points his arms towards Medea while Creusa lifts her hands towards the heavens. On the second drawing, a statue of Minerva also lifts her arms to the sky, using her shield as a protection not to see what is about to happen. All the violence of the scene can be read in the way the hands are organized in this drawing – and this violence, rarely depicted in such a direct way during the 17th century, is the one of Seneca’s tragedy.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

my dear committee of public safety,

a specter has befallen fair france: ghastly revolution! o spectacle of chaos & calamity wrought upon our beloved nation! it seems madame guillotine has become the ultimate arbiter, slicing through tradition and stability with reckless abandon. now, i must confess, my dear committee, that while i appreciate a good change of scenery as much as you, i find the current state of affairs rather… shall we say, off-key? why, it appears the revolutionaries have mistaken the guillotine for some sort of avant-garde haircutting device, snipping away at the very roots of our monarchy! ah, but fear not, messieurs, for i come bearing a solution as regal as a crown jewel! let us dust off the royal scepter, polish up the crown, and reinstate the rightful order of things! why, with a monarch at the helm, we shall steer clear of these tempestuous revolutionary waters and sail into calmer more civilized seas. but alas, i fear our revolutionary friends have become quite attached to their newfound power. it seems they've developed a taste for toppling thrones, much like a child with a penchant for knocking over sandcastles. yet i implore them to consider the consequences of their actions! for every throne they topple, another tyrant rises from the ashes like a phoenix with a napoleon complex. so let us put an end to this revolutionary farce and return to the good old days of monarchy, where the only heads rolling were those of protestants! long live the king!

your faithful enemy,

charles maurras, fidèle sujet des rois de france et de navarre

@comite-de-surete-generale I think this one's for you. A clear-cut case of counter-revolutionary propaganda from a French citizen! You used to love having clear-cut cases of counter-revolutionary propaganda from French citizens to investigate! Look, he even sent his full name at the bottom!

@comite-de-surete-generale? No? No answer? Oh for the love of... you know what, we'll handle it ourselves then. Just don't complain about "encroachment" or "subjugation" ever again. Anyways, time to file another arrest warrant. Not sure what this guy was hoping to achieve here, unless this is one big practical joke meant to waste our time.

#committee inquiries#french revolution#frev#frevblr#unreality#gimmick blog#ooc: uh wasn't this guy like VITRIOLICALLY racist and antisemitic#and like a super mega right wing nationalist as well

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Au Louvre-Lens, une expo : "Exils" (aussi bien réels qu'intérieurs, les mythes que les trajectoires personnelles de certains artistes)

Marc Chagall - esquisse pour "Adam et Eve chassés du Paradis"

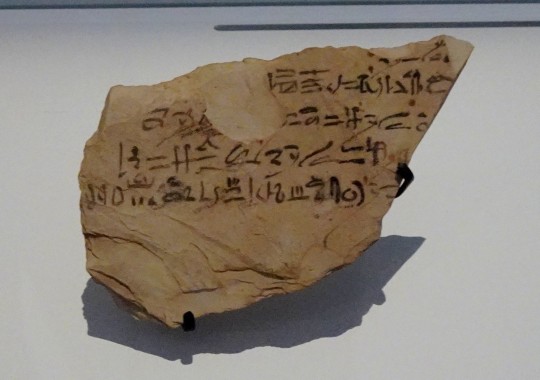

ostracon, Conte de Sinouhé - Deir-el-Medineh, 1300-1200 av. J-C.

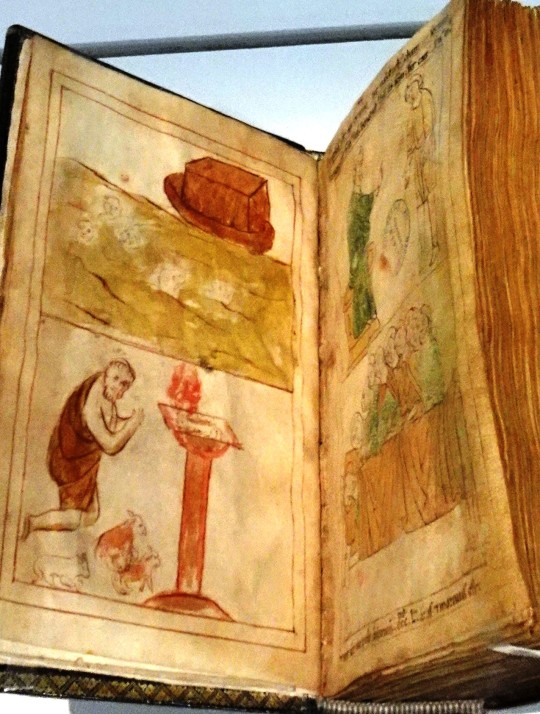

Bible historiée du roi de Navarre Sanche VII le Fort, scène du Déluge - Pampelune, fin XIIe s.

Leandro Dal Ponte (dit Leandro Bassano) - "L'Entrée des Animaux dans l'Arche"

Marc Chagall - "L'Arche de Noé"

Antoine Carrache - Le Déluge"

Enrique Ramirez - "Sail N14, La Montaña"

#louvre-lens#expo#exils#marc chagall#chagall#adam et ève#éden#déluge#bible#ostracon#égypte antique#archéologie#sinouhé#deir-el-medineh#sanche vii#navarre#pampelune#leandro dal ponte#arche#arche de noé#noé#antoine carrache#enrique ramirez#leandro bassano#art contemporain

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

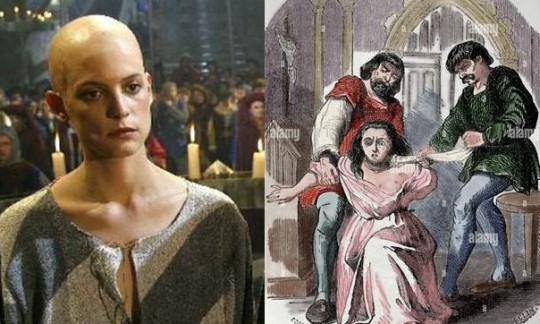

MARGARET OF BURGUNDY

MARGARET OF BURGUNDY, QUEEN OF FRANCE

c.1290-1315

Les Rois Maudits (The Accursed Kings)

Margaret of Burgundy was the Queen of France and Navarre, and was the first wife of King Louis X and I. She was a princess of the House of Burgundy, the oldest daughter of Robert II Duke of Burgundy an Anges of France (who was the youngest daughter of Louis IX of France). In 1305, Margaret married her cousin Louis I and had their daughter Joan.

In 1314, the Tour de Nesle affair was revealed, it was a well-known scandal for the French royal family. The daughters-in-law of King Philip IV, Margaret, Blanche, and Joan were all accused of adultery. The three women were said to have conducted their affairs with Norman knights in a tower in Paris.

It was Isabella of France (wife of King Edward II of England) who became a witness against those involved in the affair. Isabella had given her sisters-in-law a purse, the Norman knights were found in possession of them after the three ladies had given it to them as a gift The affair was exposed and the knights were tortured and then executed.

Margaret, Blanche, and Joan were found guilty and imprisoned. Margaret spent the last two years of her life in prison. The women were imprisoned in poor conditions and mistreated, which resulted Margaret catching a virus and passing away. She died aged 24 or 25. Joan’s paternity became in doubt after the affair.

Margaret of Burgundy is one of the characters in Les Rois Maudits (The Accursed Kings) by Maurice Druon and was portrayed in the miniseries 1972 and 2005.

#margaretofburgundyqueenoffrance #margaretofburgundy #lesroismaudits #theaccursedkings #mauricedruon

#margaret of burgundy queen of france#margaret of burgundy#margaretofburgundy#les rois maudits#the accursed kings#maurice druon

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Guillaume de Machaut / Randall Cook, J'aim sans penser I Le jugement du roi de Navarre, 2001

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louis XIV by Jean Nocret.

#jean nocret#royaume de france#royaume de navarre#louis xiv#roi de france#roi de france et de navarre#vive le roi#maison de bourbon#costume de sacre#full length portrait#coronation robes#full-length portrait#kingdom of france#house of bourbon

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louis XVI, King of France.

#royaume de france#maison de bourbon#louis de bourbon#duc de berry#louis xvi#roi de france#roi de france et de navarre#vive le roi#french revolution#kingdom of france#house of bourbon#royalty

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

bien. le temps est venu. livereading des rois maudits (tome 1)

time to meet my favourite bitch robert d’artois l’original

isabelle la plus belle ❤️

la description du physique de robert d’artois vs la personnalité de robert d’artois

AND HE’S GOOD WITH KIDS

« ses yeux gris » ??? donc il pouvait être encore plus sexy qu’avant première nouvelle

ptn robert x isabelle forever……les deux meilleurs personnages ensemble svp

please god let her be fucked raw and good once in her life she deserves it (also me too isabelle. me too.)

philippe le bel jumpscare dans la rue

GUCCIO

marguerite de navarre ma’am i am in love with you

philippe qui regarde louis en se demandant ce qu’il a bien pu faire au bon dieu pour avoir un fils aussi con

la mort de jacques de molay est mille fois plus dark jesus christ

marie de cressay x guccio mes PITCHOUNES

isabelle qui se retient si fort de pas demander à robert une nuit où il lui apprend les secrets du démontage de meuble ikea if you get me

ough okay daddy issues for isabelle

MAHAUT !!! the catfights are BACK

philippe qui se dit que vraiment il a enfanté deux incapables, un bon et une fille qu’il préfère de loin et si il pouvait franchement il lui laisserait le bled en héritage parce qu’isabelle c’est la seule personne compétente dans cette pièce

mahaut qui a un cri sourd « comme si on l’avait frappé au ventre » lorsqu’elle voit ses filles dans la misère et condamnées….

ok franchement l’exécution des frères d’aunay j’aurais pu m’en passer c’est dégueulasse

maww pépé philippe le bel qui sourit (plus d’une fois par mois attention prodige) à son petit-fils édouard qui lui tire une mèche de cheveux en se marrant, la famille putaing (plus pour longtemps)

mmh ça pue la merde pour vous les gars (nogaret et philippe le bel)

wouldn’t be surprised if you told me that philippe le bel was autistic

tolomei toi et ton gros cerveau the most manipulative bitch around je t’aime

j’adore comment philippe le bel a genre. 4 minutes et 36 secondes de bonheur dans sa vie avant de se prendre la malédiction en pleine gueule

ok so now the fun begins (dans le tome 2)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maria de' Medici, Queen of France

Artist: Frans Pourbus the Younger (1569-1622)

Genre: Portrait

Date: 1611

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Location: Uffizi, Florence, Italy

Marie de' Medici (French: Marie de Médicis; Italian: Maria de' Medici; 26 April 1575 – 3 July 1642) was Queen of France and Navarre as the second wife of King Henry IV. Marie served as regent of France between 1610 and 1617 during the minority of her son Louis XIII. Her mandate as regent legally expired in 1614, when her son reached the age of majority, but she refused to resign and continued as regent until she was removed by a coup in 1617.

Marie was a member of the powerful House of Medici in the branch of the grand dukes of Tuscany. Her family's wealth inspired Henry IV to choose Marie as his second wife after his divorce from his previous wife, Margaret of Valois. The assassination of her husband in 1610, which occurred the day after her coronation, caused her to act as regent for her son, Louis XIII, until 1614, when he officially attained his legal majority, but as the head of the Conseil du Roi, she retained the power.

Noted for her ceaseless political intrigues at the French court, her extensive artistic patronage and her favourites (the most famous being Concino Concini and Leonora Dori), she ended up being banished from the country by her son and dying in the city of Cologne, in the Holy Roman Empire.

#portrait#france#17th century#frans pourbus the younger#style#italy#french royalty#queen#medici family#curtains#custome#necklace#baroque#lace#clothing#french culture

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louis XVI (1774-1792), French Academy, undated token, Feuardent 4381. Engraver: Duvivier. Obv: Louis XVI Roi de FR.et de navarr. Rev: Protecteur de l'académie françoise. A l'immortalité

The Académie Française comprises forty members, known as les immortels ("the immortals"). During the French Revolution, the National Convention suppressed all royal academies, including the Académie Française. In 1792, the election of new members to replace those who died was prohibited; in 1793, the academies were themselves abolished. They were all replaced in 1795 by a single body called the Institut de France. Napoleon Bonaparte, as First Consul, decided to restore the former academies, but only as "classes" or divisions of the Institut de France. The second class of the Institut was responsible for the French language, and corresponded to the former Académie Française. When King Louis XVIII came to the throne in 1816, each class regained the title of "Académie"; accordingly, the second class of the Institut became the Académie Française. Since 1816, the existence of the Académie Française has been uninterrupted.

0 notes

Text

CHAMPS FERTILES

François Bayrou

1993

Ministre de l'Education Nationale

Gouvernement Balladur

Je le vois malgré moi

Fils d'Aldo Morello

Patriarche du cantone Morello

A Roasio Italie

Charles Pasqua frère d'Aldo

Et cousin Germain

De mon grand-père Ciglio Morello

Mais moi dans l'imaginaire

Ronald Reagan

A Paris et à Champigny

Pote du PCF de mon grand-père

Il s''en va aux States

A mon avis

La Fabrik et le dieu écrou

On étudie ça aux Etats-Unis

Où Mickaël Jackson est pris

Il veut faire des écrous

En lien avec Krypton

Arbeit les robots

Moi en sauvage au top

Parti du Travail avec l'Albanie

Mars 1994

Roubaix

Trois starlettes algériennes

A l'italienne

L'Opus Dei quitte l'Italie

Pour l'Espagne

Franquisme état français

Andorre l'évêque se croit fort

François Bayrou

Roi de France et de Navarre

1598 Edit de Nantes

Henri quatre

Sully les mamelles de la France

Emprunt au Général de Gaulle

De l'Ile de Sein

Pour le centre puis le MoDem état Français

Protégé par l'empire Japonais

1972 JO Sapporo

Lui aussi saint-esprit

Contre les Etats-Unis

Lundi 5 février 2024

0 notes