#rokudan no shirabe

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

WIP Wednesday

Got tagge by @heywoodvirgin and @ouroboros-hideout!

Thank you <3

—

What news to tell ya?

Some might have read it I finally updated my game last weekend and it took me half of the day bc so much updated after this big last update and I reduce my game each time to entire vanilla deleting my copies, compare the paths and files, download the updated originals and so on. No problems this way with everything working fine.

Didn't do much though as I wante to see if the game runs smooth and constantly or if it crashes after a while. It did very well so I took a few pics I needed for the story anyways I'm also still spending most on in my free time after work.

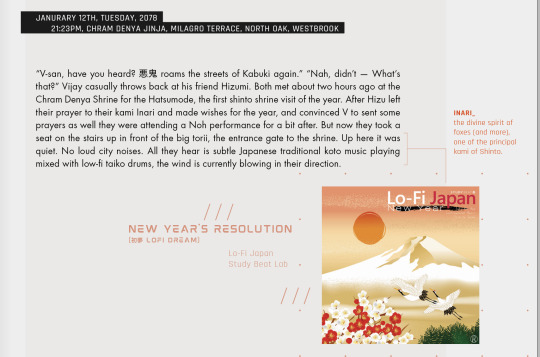

Here's a smoll preview of what I was editing at last:

Other than that?

I selected some final music for chapter 01 that can be clicked onto and listened to in the background while reading the chapter is my idea behind it.

Idk if anyone will ever do but I just think it adds something athmospheric to it, maybe helps to have a better picture as we know every picture of a movie is supported by music in some way that makes us dive far better into it.

This is how it's integrated:

Hm anything else?

I've started saving links for creating Hizumi so I quickly find them and do not have to search all over nexus again. Female V has too many cloths fr. It pains me already.

I'm not cetain when I create them but I will need them present in VP in the 2nd chapter for sure. They already appear right from the start of ch01 and I left them out already. I know they will definitely have different hair as they have on my cospaly pics bc my hair doesn't exist. I've seen some oc with a similar hairstyle but I don't think it's a public mod, so pixel Hizu will def look a bit different.

—

tagging the usual chooms (sorry if u got tagged already).

@rosapexa, @dreamskug, @wraithsoutlaws, @imaginarycyberpunk2023, @alphanight-vp, @morganlefaye79, @peaches-n-screem, @wanderingaldecaldo, @genocidalfetus, @jaymber, @hazellblogs, @therealnightcity, @streetkid-named-desire, @sammysilverdyne, @aggravateddurian, @shivsghost and @breezypunk as always, no pressure – also feel free to ignore.

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey hi, so... take this with a giant grain of salt, since I know pretty much *nothing* about japan or the language, but I think the 伊 on the box means italy? And, while I didn’t find that exact design, it may be an “art of chokin” kind of box? Do an image search on like, “chokin etched black music box”. I think those look kind of similar — gold on the edges and no keyhole? Not sure about the tune :( I hope I didn’t lead you to a dead end 😅 I hope you find out more about the box!!!

Thank you so much for your ask! It’s nice to have so many people helping me on my music box mystery, so thank you everyone! I did know that it was an “art of chokin” design! So you’re 100% right on that! I’ve also found similar ones with birds and other Japanese shrines and temples and these are the closest to mine, design wise, which are (please correct me if I’m wrong) the Arakura Sengen Shrine and the Ninnaji Temple:

Both “art of chokin” style, like mine, however the temple on my music box is the Kinkaku-ji Temple, which I have yet to see another “art of chokin” music box like it.

(This is my music box for anyone who hasn’t seen my original post)

Also someone found out the name of the tune! It’s called “六段の調べ (Rokudan no Shirabe)” or the “Music of Six Steps” (I’ve also seen it called “Melody in/of Six Movments”) so thank you again to tumbler user @blue-moon-sky for letting me know that and solving the biggest mystery!

Then the “伊” character mystery! This one I’m not 100% sure if it’s solved, but you most definitely put me on the right track so again, thank you! For those of you who might not be able to tell in the picture, the character “伊” is seen on the art of the box right there on the bottom, under the temple. Apparently “伊” is used in both the Chinese and Japanese language, but I’m no linguist and I can barely speak my own language so take what I say with a grain of salt as well, this is just what I got from a little research so feel free to correct me if I’m wrong.

In Chinese the “伊” character mean “he; she; that” but it’s not used in that sense in the Japanese language. It’s used in proper nouns like names of people and places! Here’s a copy and paste from the website that gave me the most information:

“Some common proper nouns that has 伊 are:

伊藤 "Itoh" (common Japanese family name)

伊賀 "Iga" (a place name famous as a home of ninja)

伊太利亜 "Italy"”

And I’m just going to take a shot in the dark (so this is just pure speculation) but I’m going to guess the meaning of “伊” on the box is the name of the artist who made it, or at the very least the person who did the metalwork on the box :)

And I think that covers all of the mysteries of my little goodwill find, thank you everyone who pointed me in the right direction (like you anon!) and those who just straight up gave me the answer! If anyone just happens to have more information for me, or wants to correct me on my research, please let me know! I’m always eager to learn more!

#japan#japanese culture#music box#japanese temple#kinkaku ji temple#arakura sengen shrine#ninnaji temple#japanese language#japanese art#chokin art style#asks#anon#anonymous#art of chokin#六段の調べ#rokudan no shirabe#japanese music#Yatsuhashi Kengyo

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 of 90 Day Ableton Trial (Update)

Alright, so I’ve been having a merry (albeit clunky) time using my “midi” (i.e. computer) keyboard to create a bunch of clips featuring sections from Rokudan no Shirabe, which I mentioned in my last post.

Despite the drawbacks of the laptop-keyboard-as-midi-keyboard thing (I am using the shift-uparrow / shift-downarrow function a LOT to move sections up or down an octave), I personally find it easier to “play” the instrument live than to use the draw note function. I keep the metronome running. Sometimes it takes a few tries, and sometimes I knock it out in one go.

However, I am running into a slight wall of frustration which is that I don’t know how to do a few things that I’m sure I could do with a sound editor like this. In particular, there are a few musical & instrumental elements of the original song that I want to be able to replicate electronically.

So now I’m making a new list...

Things I Want to Learn to Progress:

how to make a pitch slide (glissando) from one note to another

in particular, the unique sound of the koto technique where one can briefly raise or lower the pitch by 1-3 semitones by pushing the string down (or releasing it) on the other side of the bridge (atooshi / oshihanashi)

as well as the bend/pull technique where you can make the resonant tone waver lower after it’s plucked (hikiiro)

and the quick accent that rises and falls a half-step (tsukiro)

how to create the shuff string slide sound that is typical in koto music (it appears at the end of most of the Rokudan movements) where you graze the tsume (finger picks, or nails) along the string (zuzu, shu, chirashi? those family of sounds.)

This video is a good overview of some koto techniques and how they sound if anyone else is interested in hearing for themselves - I welcome any advice or suggestions.

As it is now, I want to be able to sustain a sound or make it waver without the initial “pluck” tone...just want to slide smoothly a half-step or whole step at a time.

#ableton#90 days of ableton#learning ableton#learning daw#digital audio workstation#making music#koto music#rokudan no shirabe#koto techniques#japanese koto#sound engineering

0 notes

Text

Music - Niome Mizune

Notes: Pick and link at least one song for each theme.

[General Theme]|

Deep Sea Girl Piano Arrange

[Travel Theme]|

Bad Apple - Classical Arrange

[Happy Theme]|

Candy, Candy

[Love Theme]|

Sayonara Daisukina Hito

[Sad Theme]|

Don’t Go (Acoustic Off-Vocal)

[Anger/Frustration Theme]|

I Hate Everything About You

[Lust Theme]|

Rokudan no Shirabe

[Villainism Theme]|

Dark Temple

[Fight Theme]|

Shadow Ninja

[Death Theme]|

Nightcore- Yume to Hazakura

Reset - English Cover

[Bonus Theme]|

Kitsune Girl

Tagged By: @cahli-tia

Tagging: Anyone, this one takes awhile to do, but was really fun! Sorry about all the Japanese songs ><

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi. Could you please tell us a bit more about the musical instruments only taught in Miyagawacho like biwa, kokyu and koto? Who teach them to geiko and maiko? The same teachers who teach the Tayu? There are some photos of recitals of geimaiko playing those instruments and I love it, specially koto. Thanks for your beautiful work.

The istruments stemming from Oiran-tradition that is still taught in Miyagawacho are the koto and the kokyū, the biwa is not taught there. They all are, however, still studied by Tayū today. Miyagawacho is the only kagai in Japan that still teaches the kokyū.

The Oiran and the Tayūstudied and the latter still studied, the arts of the nobility, which include but are not limited to koto and biwa, while the Geisha studied and still study the arts of the common people, which include but are not limited to nagauta, shamisen and kabuki.

As for who teaches the Geiko and Maiko of Miyagawacho in the playing of the koto, I’m not sure, and I also don’t know if they are the same teachers who teach the koto to the Tayūor who the Tayūlearn it from. Maybe someone else can answer this question, I’m not very well-versed in that area.

The koto is often called the “Japanese harp” in the west, as the sound and construction are somewhat comparable. The koto belongs to the zithers, which are stringed instruments consisting of one or several strings stretched over the instrument’s body, which also functions as a soundbox, or has a soundbox attached to it. Usually, the word zither is used to refer to three specific groups of instruments, the chord, concert and alpine zithers, which can be found in Slovenia, Austria, Hungary, France, north-western Croatio, southern Germany and generally alpine Europe.

The koto is based on the Chinese guzheng and is an important part of traditional Japanese court music, called gagaku. It was introduced to Japan from China during the Nara-period (710-793) and soon started gaining popularity. It was already mentioned in the Genji Monogatari, which was written in the late 10th or early 11th century and is widely regarded as the oldest fictional novel of the world, due to its high popularity amongst members of the nobility.

The average koto is 1,80 meters wide and 25 centimeters wide, hollow and made of paulownia wood. The 13 strings were traditionally made of silk, but today they are usually made of nylon or teflon, because they last longer and almost sound the same.

The instrument’s body is curved upwards, has two sound-holes and two small bridges over which the 13 strings are stretched. All strings have the same tautness to them and are stretched over 13 moveable bridges called ji. By moving the ji, the different sounds can be adjusted or changed while playing. The ji used to be made of rose wood or even ivory, but today, usually several kinds of plastic are used.

For each part of the koto, there is a mythological description, where the koto is compared to a dragon. The upper back of the koto is the “dragon’s shell” (竜甲, ryūko), the lower part is the “dragon’s stomach” (竜腹, ryūhara), the back part is the “dragon’s tail”(竜尾, ryūbi), the front bridge the “dragon’s horns” (竜角, ryūkaku) and the rear bridge “the seat of the angels/cloud horns” (雲角, kumokaku), alluding to the clouds above the dragon’s horns.

The koto is played either kneeling at the ground or sitting using wooden legs. The strings are plucked using the right hand sitting at the right end using claw-like plectrums called “tsume” (爪, “claw”, “fingernail”) that are worn like rings on the fingers. Tsume are can be made several materials, for example of ivory with rings made of bamboo, but alo completely made of plastic. The left hand can be used to make sound-effects, pluck strings or lower the sounds by a half or one full note by pressing the strings down.

There are two main koto-schools, the Ikuta and the Yamada School. They use different plectrums - the Yamada School uses fingernail-like plectrums and the Ikuta School uses square plectrums - and there are differences in the way of playing, and the Ikuta School focuses on vocal accompaniment to the playing of the koto.

Instruments related to the koto are the Chinese guzheng, the Korean gayageum, the Vietnamese đàn tranh and the Mongolian yatga. One of the most famous pieces composed for the koto is Rokudan No Shirabe, composed byYatsuhashi Kengyō. You can listen to it here.

The kokyū is a traditional Japanese string-instrument, but the only one played with a bow. It was introduced to Japan from China in the 17th century, but the sound, shape and cosntruction are unique to Japan. The kokyū has a uniquely Okinawan version called thekūchō (胡弓 くーちょー)in the Okinawan language. The kokyūis often called “the Japanese violin” in the west, as both of these instruments are played using a bow.

The kokyū looks quite similar to the shamisen, at first sight, it looks like a smaller version of the shamisen. It’s 70 centimeters tall, and its neck is made of ebony, its hollow body is made of coconut or styrax japonica wood and is covered on both ends with catskin (the kūchō is covered with snakesin). It has three, or sometimes four, strings and is played upright while kneeling with a horsetail-strung bow.

The kokyū used to be an important part of the sankyoku ensemble, consisting koto, shamisen and kokyū, that was the most popular in central Japan, but since the 20th century the kokyūhas often been replaced by the shakuhachi.

Shinei Matayoshi, a kokyūand sanshin (the Okinawan predecessor of the shamisen) musician and sanshin maker, invented a four-stringed version of the kokyūto expand its range, it has become much more popular again.

The kokyū is similar to two Chinese lutes that are also played with a bow: The leiqin and the zhuihu. In Japanese, the term kokyū can refer to any Asian string instrument played with a bow, as does the Chinese term huqin. That’s why the Chinese erhu, which is also used by some performers in Japan, is sometimes called a kokyū, along with the kūchō, leiqin, and zhuihu. The specific Japanese name for erhu is niko.

Here you can listen to th song “Kurokami“ being performed by a shamisen-player and a kokyū-player.

The biwa (琵琶) is a short-necked, fretted lute that came to Japan from China in the 7th century and has its origins in the Chinese instrument pipa. They usually have four strings, but the modernsatsuma and chikuzen biwas can also have five strings. There are more than 7 types of biwa. The biwa is the instrument of Benzaiten/Benten (弁才天, 弁財天), a Bhuddist goddess, who originated from the Hindu goddess Saraswati. She is thegoddess of music, eloquence, poetry, and education inShinto.

The type of biwa that was developed in the the 7th century is called gaku-biwa and is used in gagaku, traditional Japanese court music. It’s also the most common and well-known type of biwa.

Through an unknown route, another type of biwa found its way to the Kyushu region around the same time, and this thin biwa (called mōsō-biwa or kōjin-biwa) was used in ceremonies and religious rites.

Then, as the Ritsuryō state collapsed, the court music musicians playing the gaku-biwa were faced with the reconstruction of the country and sought asylum in Buddhist temples. There, they became Buddhist monks and encountered the mōsō-biwa. They incorporated the convenient aspects of mōsō-biwa, mostly its small size and portability, into their large and heavy gaku-biwa, and created the heike-biwa, which was used primarily for recitations of The Tale of the Heike.It kept the rounded shape of the gaku-biwa and was played with a large plectrum like the mōsō-biwa. As said above, the heike-biwa was also small, like the mōsō-biwa and was used for similar purposes.

Through the next several centuries, players of both instrumentsintersected often and developed new music styles and new types of biwa. By the Kamakura period (1185–1333), the heike-biwa had become a popular instrument.

The modern satsuma-biwa and chikuzen-biwa both originated in mōsō-biwa, but the Satsuma biwa was used for moral and mental training by samurai of the Satsuma Domain during the Warring States period, and later in general performances. The Chikuzen biwa was used by Buddhist monks visiting private residences to perform memorial services, but also for telling entertaining stories and news while accompanying themselves on the biwa, and this form of storytelling was thought to be spread in this way. This is why the biwa’s most popular use today is still to accompany narrative storytelling.

There wasn’t much written about the biwa from the 16th century to the mid-19th century. It is known, however, that three main streams of biwa emerged during that time: zato (the lowest level of the state-controlled guild of blind biwa players), shifu (samurai style), and chofu (urban style). These styles called biwa-uta (琵琶歌, vocalization with biwa accompaniment) formed the foundation for edo-uta styles (江戸歌) like shinnai and kota.

From these styles also emerged the two main survivors of the biwa tradition: satsuma-biwa and chikuzen-biwa, which are still the most popular kind of biwa today. From the Meiji Era (1868–1912) until the Pacific War, the satsuma-biwa and chikuzen-biwa were popular across Japan, and at the beginning of the Showa Era (1925–1989), the nishiki-biwa was created and gained popularity. Of the remaining biwa traditions, only higo-biwa remains a style almost exclusively performed by blind people. The higo-biwa is closely related to the heike-biwa and mainly relies on an oral-narrative tradition focusing on wars and legends.

Here’s a list of the types of biwa, which differ in their number of strings, sounds it can produce and plectrums they are played with:

The Gagaku-biwa (雅楽琵琶) or Gaku-biwa (楽琵琶): The most common and widely known biwa to this day. It’s large and heavy with four strings and four frets and is used exclusively for gagaku. The plectrum used with it is small and thin, often rounded, and made from a hard material such as boxwood or even ivory. It is not used to accompany singing. It’s played held on its side, similar to a guitar, and the player sits cross-legged.

Gogen-biwa (五絃琵琶): This type of biwa was used for gagaku, but was removed with the reforms and standardizations made to the court orchestra during the late 10th Century, and died out around the same time. It also disappeared in Chinese court orchestras. Recently, this instrument has been revived for historically informed performances and historical reconstructions.

Mōsō-biwa (盲僧琵琶): This biwa has four strings and is used to play Buddhist mantra and songs. Its shape is similar to the chikuzen-biwa, but with a much more narrow body. Its plectrum varies in both size and materials.

The gaku-biwa, gogen-biwa andmōsō-biwa are summarized as the classic biwa.

Heike-biwa (平家琵琶): This biwa has four strings and five frets and is used almost exclusively to recite the Heike Monogatari. Its plectrum is slightly larger than that of the gagaku-biwa, but the instrument itself is much smaller. It was originally used by traveling biwa minstrels, as its small size made it practical for indoor play and traveling.

Satsuma-biwa (薩摩琵琶): A biwa with four strings and four frets made popular during the Edo Period in Kagoshima (which used to be Satsuma province hence the name) by Shimazu Nisshinsai. The frets of the Satsuma biwa are raised 4 centimeters from the neck allowing notes to be bent several steps higher, each one producing the instrument’s characteristic sawari, or buzzing drone sound. It’s played using a boxwood plectrum that is much wider than that of most others biwa, often reaching widths of 25 cm or more. Its size and construction influences the sound of the instrument as the curved body is often struck percussively with the plectrum during play. It’s usually made from Japanese mulberry, although other hard woods like Japanese zelkova are sometimes also used.The most famous 20th century performer was Tsuruta Kinshi, who developed her own version of the instrument, which she called the tsuruta-biwa. This biwa often has five strings (although it is essentially a 4-string instrument, because the 5th string is a doubled 4th and they are always played together) and five or more frets, and the construction of the tuning head and frets vary slightly. Ueda Junko and Tanaka Yukio, two of Tsuruta Kinshi’s students, continue the tradition of the modern Satsuma biwa.

The Heike-biwa and the Satsuma-biwa are summarized as the Edo-biwa.

Chikuzen-biwa (筑前琵琶): This biwa has four strings and four frets or five strings and five frets and was made popular in the Meiji Period by Tachibana Satosada. Today, most performers use the five string version. The plectrum it’s played with is usually made from rosewood with boxwood or ivory tips for plucking the strings and is much smaller than that of the Satsuma biwa, usually about 1 cm in width, although its size, shape, and weight depends on the sex of the player, as does the instrument’s size itself. Male players use slightly wider and/or longer chikuzen-biwas than those used by females or children. The body of the instrument is not struck with the plectrum during play, and the five string instrument is played upright, but the four-stringed one is played held on its side. The instrument is tuned to match the key of the singer. Asahikai and Tachibanakai are the two major schools of the chikuzen-biwa. It’s popularly used by female biwa players such as Uehara Mari.

Nishiki-biwa (錦琵琶): A modern biwa with five strings and five frets popularized by Suitō Kinjō. The plectrum used with it is the same as the one used for the Satsuma biwa.

Although the biwa used to very popular for many hundreds of years, it was almost completely lost due to war and the ban of Todo, one of the instrument’s main group of patrons, and the rapid industrialization, modernization and westernization during the Meiji Period, and many biwa-schools and even entire types of biwa almost died out completely. Luckily, the biwa is being revived through both modern and traditional Japanese musicians.

Here you can listen to biwa-player Yoko Hiraoka playing “Gion Shojo” on the Chikuzen-biwa while also singing.

Sources: https://www.britannica.com, https://www.wikipedia.org (German and English), http://www.japanesestrings.com/instruments.html

#ask#biwa#koto#kokyuu#tayuu#oiran#geisha#maiko#geigi#geiko#miyagawacho#karyukai#japan#japanese#instruments#japanese instruments

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

🎚️ And go!

- A cultural piece that suits my muse

youtube

I would say that is Rokudan no Shirabe, by Yatsuhashi Kengyo. I heard it on Civ V for the first time, as the Japan’s theme. As part of the theory transition to the modern koto instrument playing, this song is so good to the ears that you can dance (or fight) with it on the background. Since Shintaro is based on japanese traits, I guess it would be a nice cultural piece for him.

Thanks for asking, @emelineredwyne :)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

ETSUKO CHIDA

Etsuko Chida a commencé à cinq ans à suivre l’enseignement de l’école Yamada auprès de trois virtuoses du koto, Kaga Toyomasa, Yokota Toyochika et Sanagi Hokatoyo. C’est après de longues années d’études qu’elle a obtenu le privilège de pouvoir porter un natori, un nom professionnel, celui de Toyochi Eka. L’école Yamada n’est pas la plus ancienne des écoles de koto, mais la plus traditionnelle. Elle a été fondée à Edo (l’ancien nom de Tokyo) par Yamada Kengyô, qui vécut de 1757 à 1817. Alors qu’Ikuta Kengyô (1656-1715), fondateur de l’école Ikuta, avait inventé un plectre carré qui nécessitait que les instrumentistes se placent en biais, pour pouvoir attaquer les cordes avec la puissance nécessaire pour rivaliser avec la puissance sonore du luth à trois cordes shamisen (alors appelé sangen), Yamada Kengyô est revenu aux formes anciennes du sankyoku, telles qu’elles existaient avant Ikuta. Il a créé un nouveau répertoire mettant en valeur le chant et empruntant notamment son contenu narratif au théâtre nô et aux genres narratifs locaux tels que le katô-bushi ou l’itchu-bushi. Il a également réintroduit le plectre de forme ovoïde qui permet un jeu plus délicat où l’instrumentiste se place en faisant face à l’instrument. Une grande partie du charme de cette musique vient de la correspondance subtile qui s’établit entre la voix de la chanteuse et la partie instrumentale. Etsuko Chida y excelle, sachant allier une technique éprouvée à une apparente simplicité. L’instrumentiste doit éviter les mouvements trop amples ou brusques, l’harmonie visuelle faisant écho à celle de la musique. La rigueur toujours présente est cependant ici bien éloignée de toute rigidité : nous sommes ici au cœur de ce que les Japonais appellent le wabi-sabi. Le wabi est un concept lié à la cérémonie du thé, qui s’applique à tous les arts japonais, la simplicité et la rusticité (au moins apparentes), amenant naturellement à l’expression idéale de la beauté. Le sabi est un ancien concept esthétique qui date de la période de Muromachi (1333-1574). Il met l’accent sur la beauté des choses naturelles et l’économie de moyens, liée au sentiment d’une solitude à la fois mélancolique et sereine, comme on peut le retrouver dans les haï kaï de Matsuo Bashô. Cet aspect naturel se retrouve dans le jeu d’Etsuko Chida qui nous confiait qu’elle ne comptait jamais les temps au cours de l’interprétation d’une pièce, alors que la durée de ses différentes versions d’une même composition s’étendant sur plus d’une dizaine de minutes ne varie jamais de plus de quelques secondes. La précision est ici vécue de l’intérieur, en se laissant guider par le mouvement rythmique global de la pièce, loin de tout aspect mécanique. Etsuko Chida fait partie de cette nouvelle génération de musiciens traditionnels japonais qui parcourent le monde : elle s’est ainsi produite au Japon, en France, en Allemagne, en Espagne, en Italie, au Maroc, en Norvège et au Portugal. Elle a mis également sa voix expressive et délicate au service de créations d’œuvres du compositeur de musique contemporaine Igor Ballereau, à la Villa Medicis et à Strasbourg. Elle a cependant éprouvé le besoin de se ressourcer et a séjourné plusieurs semaines à Tokyo, pour bénéficier des conseils de Iemoto Yamato Shôwa, un des maîtres actuels de l’école Yamada. Il faut d’ailleurs noter que cette pratique est traditionnellement peu usitée, mais que sa demande a été bien accueillie et ses rencontres avec le maître très fructueuses.

Elle interprétera d’ailleurs « Usu no koe » (La Voix du mortier de bois), une composition de Yamato Shorei, l’un des ancêtres de Yamato Shôwa. Les paroles célèbrent la nature et la vie rustique : « Dans les pauvres demeures de paysans faites de murs et planches minces, on chante, en pilant le riz, un chant rythmé. Qu’il est plaisant d’entendre sa cadence résonner entre deux rafales de vent. »

« Yûgao » (La Belle-du-soir) est une œuvre dont les paroles s’inspirent du quatrième chapitre du « Dit du Genji », écrit vers 1020 par la dame d’honneur Murasaki Shikibu. La « Belle-du-soir » est une séduisante et mystérieuse jeune femme dont le destin se révèlera aussi éphémère que la fleur dont elle porte le nom. « Chidori no kyoku » (Le Chant des pluviers) décrit d’abord les vagues qui viennent doucement mourir sur le rivage. Le tegoto, la partie instrumentale, évoque le vol de pluviers qui passent au-dessus de la grève. Enfin, sont décrites la tristesse et la solitude d’un gouverneur en poste sur ce « Rivage des Syrtes » nippon. « Au chant triste de pluviers qui, traversant le détroit d’Akashi, tournaient au-dessus de l’île d’Awaji, combien de nuits le gouverneur de Suma, envahi par les souvenirs de son pays natal, s’est-il éveillé, le cœur lourd de nostalgie ! «

Voici le programme pour Saint Avit de Vialard.

Rokudan no Shirabe (Six parties) 六段の調 Composition : Yatsuhashi Kengyō (1614-1685)

Yûgao (La Belle du soir) 夕顔 Auteur : inconnu Composition : Kikuoka Kengyô (1792-1847) Transcription pour koto : Yaezaki Kengyô(1776-1848)

Chidori no kyoku (Le chant des pluviers) 千鳥の曲 Auteur : Minamoto no Kanemasa (Autour de 1100) Composition : Yoshizawa Kengyô II (1808-1872)

Usu no koe (La voix du mortier de bois) 臼の聲 Auteur : Morikawa Sanzaemon Composition : Yamato Shôrei III (1844-1889) Pièce composée en 1879.

Etsuko Chida nous entraîne à travers ces pièces anciennes dans un Japon traditionnel qui reste toujours vivant au sein du monde industriel, tout en nous prouvant de manière émouvante que ces musiques ne sont pas figées et que les meilleurs artistes de la nouvelle génération savent lui apporter le cachet de leur propre personnalité.

http://www.cernuschi.paris.fr/sites/cernuschi/files/editeur/etsuko_chida_0.pdf

Discographie : Etsuko Chida. Japon : Chants courtois. Buda records 1987862

0 notes

Video

youtube

(January 21, 2013) Learning うれしいひなまつり (Ureshii Hina Matsuri) and practicing 六段の調 (Rokudan no Shirabe) parts 1 and 2.

#cultural project#六段の調#うれしいひなまつり#Rokudan no Shirabe#Japanese culture#traditional Japanese music#koto#learning koto#playing koto#Ureshii Hina Matsuri#youtube

0 notes

Text

Learning Ableton: Days 4-7

So after my mad rush of the first few days, where I had a LOT of focus and clarity, the immediate energy has diminished. (But certainly not disappeared. After a few restful, low-pressure days, I came to my desk feeling restored and ready to get stuff done!)

I spent the last few days toying around with samples and loops, arranging things, starting a bunch of new projects but not finishing them, and learning more about how to navigate the software.

(It’s a lot of little things: like, “Why can’t I keep creating notes in the midi editor even though my clip is several measures long? Why is it limiting me to one measure? Answer: unselect the “loop” option at the bottom.)

I’ll share some of the small things I worked on over the last few days, but right now I’m going to put on my headphones and keep working at my newest project...

I’m tentatively trying out a lofi version of Rokudan no Shirabe which is an Edo-period composition for Japanese koto. I love this piece (”Rokudan”) and have a personal connection to it, since I learned it on koto myself many years ago. (Gosh, it’s been about a decade since I took koto lessons...)

Sadly I don’t have my own instrument to sample - I’m just working with one of Ableton’s presets for Koto.

More to come soon!

#90daysofableton#ableton#daw#learning ableton#digital audio workstation#rokudan no shirabe#koto#japanese koto#lofi

0 notes

Video

youtube

AAiJ: Learning Koto 6

(January 14, 2013) Seems I'm always playing catch up! My first lesson after the hiatus I had to take starting in December. I review everything and practice Rokudan. Also, my koto teacher plays with her pinky like a boss.

#cultural project#六段の調#Rokudan no shirabe#koto#Japanese culture#traditional Japanese music#learning koto#playing koto#youtube

0 notes

Video

youtube

Still catching up on these koto videos. I'll be thankful for taking the time now when my culture project deadline suddenly pops up out of nowhere.

#六段の調#rokudan no shirabe#koto#American#Japan#Japanese culture#traditional Japanese music#learning koto#playing koto#Another American in Japan

0 notes