#robert herlth

Text

Andrei Andrejew, set design drawing for Crime and Punishment (Raskolnikow) 1923

Robert Herlth and Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, Faust 1926

Set drawing for ”Das Kabinett des Dr Caligari” 1920

Hermann Warm, Robert Wiene’s “Das Kabinett des Dr Caligari” 1919

308 notes

·

View notes

Photo

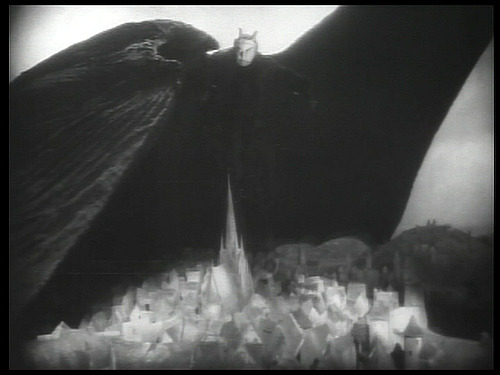

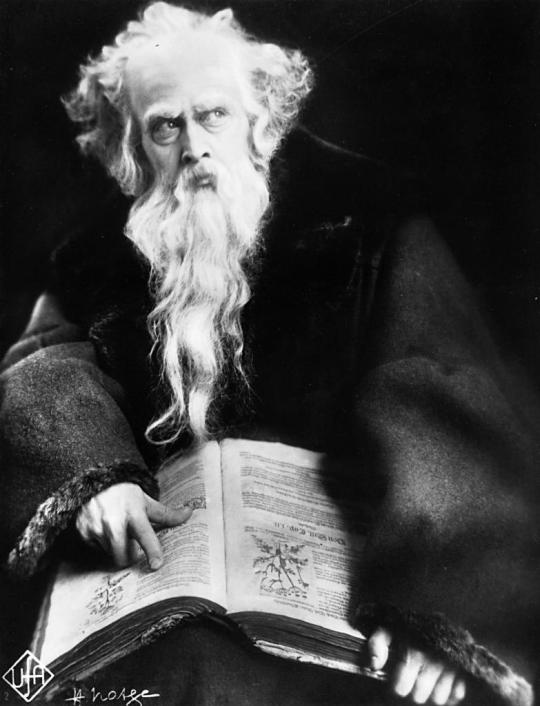

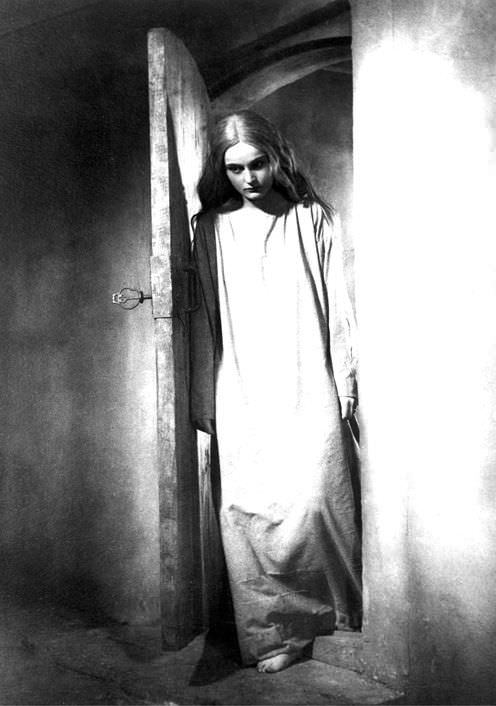

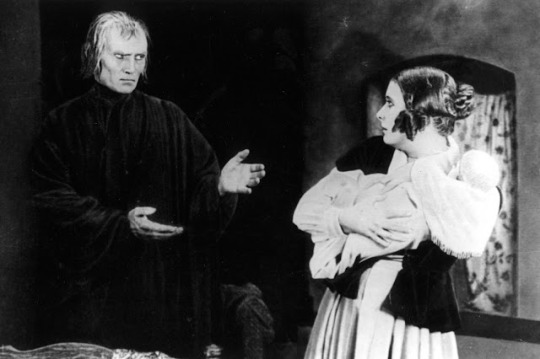

Faust (F.W. Murnau, 1926)

Cast: Gösta Ekman, Emil Jannings, Camilla Horn, Frida Richard, William Dieterle, Yvette Guilbert, Eric Barclay, Hanna Ralph, Werner Fuetterer. Screenplay and titles: Gerhart Hauptmann, Hans Kyser, based on a play by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Cinematography: Carl Hoffmann. Art direction: Robert Herlth, Walter Röhrig. Film editing: Effi Bötrich.

Power corrupts, as we knew long before Lord Acton so nicely formulated it for us. It's the truth underlying so many myths, from the Garden of Eden to the Nibelungenlied to the Faust legend. Goethe's Faust is a philosophical poem, a closet drama not designed for stage or film, but that hasn't prevented playwrights, opera librettists, or screenwriters from making the attempt. F.W. Murnau's version is probably the most distinguished cinematic attempt, but not because of its fidelity to the source. Murnau's version works because it concentrates on the power struggle, initially between Good, as represented by the archangel (Werner Fuetterer), and Evil, as represented by Mephisto (Emil Jannings), and later by the attempt of Faust (Gösta Ekman) to obtain mastery over Time. It begins with a wager, borrowed from the book of Job, between the archangel and Mephisto, over whom Faust's soul will belong to. Then it eventually devolves into what is the core of most dramatic treatments of Goethe's story, the seduction of Gretchen (Camilla Horn), with the aid of Mephisto. In the end, both Gretchen and Faust are redeemed by his willingness to sacrifice himself, an abnegation of power. But that too-familiar story is distinguished by Murnau's staging of it, with the significant help of Carl Hoffmann's cinematography and the art direction of Robert Herlth and Walter Röhrig. This is one of the most beautiful of silent films because of the interplay between light and dark, a superb evocation of the paintings of Rembrandt in the composition and lighting of scenes. The tone of the film is set near the beginning by the spectacular image of a gigantic Mephisto looming over a German town, which clearly influenced the similar scene in the "Night on Bald Mountain" sequence of Walt Disney's Fantasia (1940). Jannings manages to be both sinister and gross as Mephisto -- the latter mode most in evidence in his scenes with Gretchen's lustful Aunt Marthe (Yvette Guilbert). (If Guilbert looks familiar it's because, as a Parisian cabaret singer during the Belle Époque, she was the subject of numerous portraits by Toulouse-Lautrec.) This was the last of Murnau's films in Germany: The following year he moved to Hollywood, where he made probably his greatest film, Sunrise. He was soon followed to America by the actor who played Gretchen's brother, Valentin, William Dieterle, who became a prominent Hollywood director.

Top: Yvette Guilbert and Emil Jannings in Faust. Bottom: Yvette Guilbert by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Photo

Asphalt (Joe May, 1929).

#asphalt (1929)#asphalt#joe may#albert steinrück#betty amann#günther rittau#rené hubert#erich kettelhut#robert herlth#walter röhrig

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

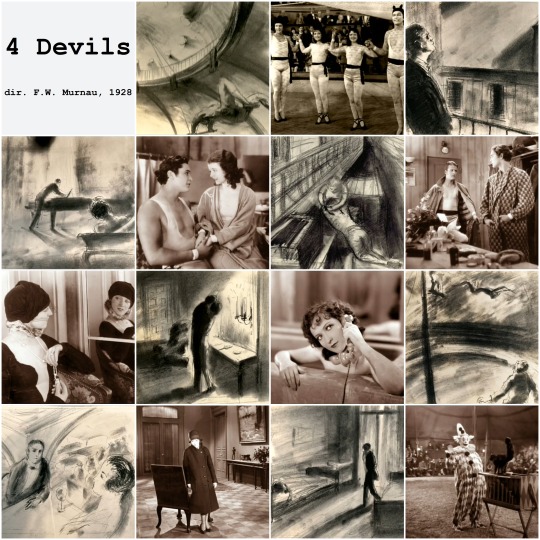

4 Devils

directed by F.W. Murnau, 1928

For the first time ever, I’m not using screenshots to make a movie mosaic. That’s because 4 Devils is, sadly, a lost film. It’s one of the most sought after lost films of all time, as reviews following its release consistently cited it as one of Murnau’s best.

In this mosaic, you will find a combination of publicity stills and drawings made by art director Robert Herlth. The stills would have been taken on set, but do not account for the lighting and camerawork that Murnau was known for. Herlth’s drawings give an idea of the atmosphere that 4 Devil’s aesthetic would have evoked. My hope is that by presenting them alongside each other, I can fulfill my goal of capturing a movie’s essence with one collection of photos.

Should a copy of this film show up, it would be one of the greatest discoveries in the history of film. Until then, it exists only in our imaginations.

#4 Devils#Four Devils#F.W. Murnau#Robert Herlth#movie mosaics#Barry Norton#Janet Gaynor#Nancy Drexel#Charles Morton#Mary Duncan#J. Farrell MacDonald

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

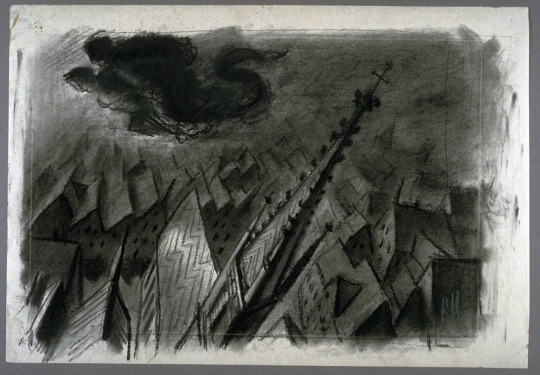

Storyboard/set design sketches by Robert Herlth for Faust (1926).

#faust#robert herlth#f.w. murnau#silent film#weimar cinema#storyboard#set design#sketches#film artwork

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

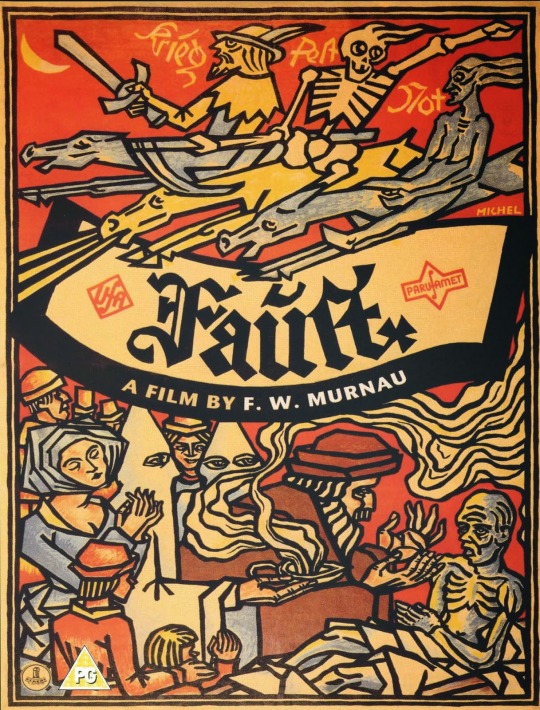

FAUST - (Friedrich W. Murnau, 1926

“Mephisto first gives old magician Faust the opportunity to make miracles for a day, then makes him a handsome young man; so transformed, Faust seduces Margaret who is then sentenced to the stake when his baby dies; an old man again, Faust climbs the stake but in the epilogue Archangel Gabriel announces Faust’s soul has been saved by the strength of love.”

Genesis

"Faust” was the last movie Murnau directed in his homeland before fleeing Germany and, like Lang’s “Die Nibelungen”, was one of those “kolossal” that, ispired to the most typical German cultural tradiction and conceived in the UFA distinctive monumental style, aimed to fullfill the ideological and spectacular requisites of the emerging “Quality Cinema”. The movie proposed itself as an extraordinarily hyper-qualified piece of culture as evryone can realize by its collaborators, to begin by Gerard Hauptmann (who composed the original captions by rhyming couplets), the poet and screenwriter Hans Kyser, the great art directors Robert Herlth and Walter Röhrig and a prestigious international acting cast with Emil Jannings, Gosta Ekman, Yvette Guilbert and an hollywoodian star like Lillian Gish (then replaced by the excellent debutant Camille Horn). The movie is a Deutsche Volkssage in which co-exist (if with daring dissonances) eterogenous art materials taken by Goethe, Marlowe, the altomedioeval germanic legends and the musical melodramas (Berlioz). Such stuff, if great, was extraneous to Murnau’s concerns so the director dedicated his work mainly to the expressive possibilities of the image. The resulting movie is, also thank the magnificent cinematography by Carl Hoffman, (”Die Nibelungen”) a great “plastic”achievement.

Insights.

“Faust” is an accurate technical/linguistic machine, a powerful signifier that organizes and proposes an heterogeneous narrative action that is rendered in a unique form by several different (and seemingly contradictory) levels, like legend, private events, existential conflicts, aesthetics, moral and love, and, to accomplish it, Murnau uses the Expressionism (a movement and a style he never adhered to) because he considered that “genre” a filmic form already surpassed and so, already worthy of an “ironic” evocation (and, accordingly, the movie continuously alludes to canons and objects typical of the expressionist “décor”, while, on another plan, the expressionist features and motives (often reduced to a “cliché” status), serve to represent and to characterize a story (the narrative action) crushed into a moltitude of situations who, by themselves, reveal and suffer the cultural fashions of his (Murnau’s) historical era (demonism, spiritism, mystery, magic...). And parody, irony, dissacration involve the characters too, who, by assuming comic or joking behaviors, act like implicit transgressions of a serious thematic material so transferring to it an unusual ribald tone. This way “Faust” becomes emblematically “kitsch”, a cultural highly parodic operation that permit Murnau to suddenly get free from a ruling subculture full with commonplaces. Under this pov Murnau’s “Faust” acts as a global cultural process of liberation. By now the director, after having brilliantly exhausted his research about the stylistic pecularities of the cinematic mise-en-scène, is ready to live the American adventure an to experiment, in a love/hate conflict, the illusory freedom given to him by the Hollywood-ian capitalism.

r.m.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Robert Herlth's sketch for Faust (1926), dir. Friedrich Murnau.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

4 Devils (F. W. Murnau, 1928) [lost film], production drawings, Part IV | Production design by Robert Herlth, Walter Röhrig, and Edgar G. Ulmer.

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Death (Bernhard Goetzke) and the Young Woman (Lil Dagover) in Der müde Tod (Fritz Lang, 1921)

Cast: Bernhard Goetzke, Lil Dagover, Walter Janssen, Hans Sternberg, Karl Rückert, Max Adelbert, Wilhelm Diegelmann, Erich Pabst, Karl Platen. Screenplay: Fritz Lang, Thea von Harbou. Cinematography: Bruno Mondi, Erich Nitzschmann, Herrmann Saalfrank, Bruno Timm, Fritz Arno Wagner. Art direction: Robert Herlth, Walter Röhrig, Hermann Warm. Film editing: Fritz Lang.

Der müde Tod, which means "Weary Death," was released in English-speaking countries under titles like Destiny, Behind the Wall, and The Three Lights, all of which miss an essential premise of the film, which is that Death (Bernhard Goetze) has grown weary of his encounters with human suffering. So when he takes a Young Man (Walter Janssen) whose fiancée (Lil Dagover) seeks out Death and pleads for his return. he is inclined to give her a break: He will give her three chances to save the life of someone destined to die, and if she succeeds, he will return the Young Man to life. So we see the Young Woman in three episodes set in wonderfully fanciful versions of the past: ancient Persia, Renaissance Italy, and imperial China. Each time she tries to save her lover from the death she knows is coming, but each time she fails. Dagover and Janssen play all three pairs of lovers, with Goetze lurking in various fatal incarnations in each episode. When she fails, Death gives her one last chance: Returning the Young Man to life would leave an empty place in the afterlife, but if she can persuade someone to give up his or her life to replace him, he will spare her fiancé. It's a beautifully constructed fantasy, written by Fritz Lang and his wife, Thea von Harbou, and directed by Lang with his usual exploitation of elaborate sets and camera effects. The art direction is by Robert Herlth, Walter Röhrig, and Hermann Warm, frequent collaborators with the great German directors of the period between the wars, such as Lang and F.W. Murnau.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Herr Tartüff (F.W. Murnau, 1925).

#herr tartüff#herr tartüff (1925)#tartuffe#tartuffe (1925)#f.w. murnau#karl freund#robert herlth#walter röhrig#robert baberske#el hipócrita#el hipócrita (1925)

241 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Herr Tartüff (F.W. Murnau, 1925).

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Herr Tartüff (F.W. Murnau, 1925).

#herr tartüff (1925)#herr tartüff#f.w. murnau#molière#carl mayer#rosa valetti#karl freund#robert herlth#walter röhrig#waldemar jabs

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

4 Devils (F. W. Murnau, 1928) [lost film], production drawings, Part III | Production design by Robert Herlth, Walter Röhrig, and Edgar G. Ulmer.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Part II: 4 Devils (F. W. Murnau, 1928) [lost film], production drawings.

Production design by Robert Herlth, Walter Röhrig, and Edgar G. Ulmer.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

4 Devils (F. W. Murnau, 1928) [lost film]: Production drawings.

Production design by Robert Herlth, Walter Röhrig, and Edgar G. Ulmer.

73 notes

·

View notes