#riding on the coattails of a stronger force

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"Riding on the coattails of a stronger force" by Yuna ISHIDA

#石田優奈#yuna ishida#虎の威を借る#borrowing the tiger's fierceness#japanese painting#Joshibi University of Art and Design#20240226#art#riding on the coattails of a stronger force#tiger#gold folding screen

171 notes

·

View notes

Note

How would you rank the seasons of TXF from first to worst. I know canon ends for you at S8 so you don’t have to include the other seasons if you don’t want to. Mine ranking goes like this (first to worst)

3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 7, 2, 1, 11, 9, 10

Hot take (kind of) = S10 and S11 are not canon… I hate what CC did to the mythology, William, breaking up M and S, etc…

Extremely hot take: IWTB > FTF. I have reasons but I’m not going to get into that right now

I have four answers for this: the seasons ranked by mytharc, the seasons ranked by MOTW, the seasons ranked by quality, and the seasons ranked by favorites.

(Beware: I flame all garbage herein, including my own. ...And there are bound to be typos-- will ghost edit later~.)

Breaking down each season by its characteristics, two main strengths stand out: their narrative or MOTW focus. Each season plays more heavily with one facet than the other (except Seasons 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8, which blends them to varying degrees of success.)

In order of consistent theme-- if not, at times, quality:

The Narratively Strong Seasons: Fight the Future, Season 8 (I know, hear me out), Season 6, Season 3, Season 2, Season 4, and Season 9. Each entry is held together by the backbone of one (or several interconnecting) ideas: Fight the Future quite literally functions around the mytharc, and is stronger for it; Season 8 punctuates almost every. single. episode. with one or more characters trying to either find Mulder or the answers to his disappearance; Season 6 rides the coattails of FTF as the leads find a mytharc resolution and begin to iron out the wrinkles in their personal relationship; Season 2 never forgets the duo's loss of the files and Scully's abduction, peppering his and her struggles into most of the episodes; Season 3 mostly deals with Scully's abduction memories, Melissa's death, and the unfolding mytharc; Season 4 is half cancer arc and half well-written filler, only returning to the main theme here or there; and Season 9 supposedly follows cop-style casefiles and Scully's single motherhood (but is really about Scully weeping on and off while events just happen to justify the next surprise twist.)

The MOTW Seasons: Season 1, Season 5, Season 7, Season 9, Season 11, IWTB, and Season 10. Each season is punctuated by its monsters rather than its mytharc, with the latter taking a backseat to the former. Season 1 is the epitome of the MOTW formula, saving mytharc for a whiff here and there but mainly focusing on the monsters always around; Season 5 is chockful of cryptid excellence and mid-to-fleeting mytharc narrative impact; Season 7 pulls its head above water with each good MOTW episode; Season 9 would be solid if Scully's characterization hadn't been so heavily butchered; Season 11 is iffy on the quality of its characterization and its casefiles; IWTB is appalling in MOTW quality; and Season 10 is the worst, with very little making sense, even in the MOTW moments.

Ranking the quality of each season is a hard and nuanced task. Because I am but a mere mortal with only so much time for contemplation, it's one I shall leave for the individual. Objectively-- the total quality of the product, not just one's favorite parts of it-- though, I think we can all agree that S1-S6 were the best, and that S7-S11's writing wheezed a long death rattle. While enjoyable in parts, perhaps even narratively satisfying at times, the latter's execution iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiis bad.

Ranking My Favorite Seasons: Season 8, Season 6, Seasons 1/2, Fight the Future, Seasons 4/5, Season 3, Season 7; then descending order of the sloppily written (S9, S11, IWTB, and S10.) For the fun of it, I'm going to go a little more in-depth on my choices.

Season 8 is a HOT mess, and I won't even attempt to deny it. The MOTWS are mid and the mytharcs are worse. Its strengths, however, lie in how tightly wound the narrative is to Mulder's abduction, which forces the characters to introspect more openly on-screen. Which is great. ...However, the writers lose interest in that angle after Mulder's return; and jump right back into mytharcmytharcmytharc without taking a moment for Mulder to process his own trauma, as well. What separates Season 8 from Season 9 is its characterization: Scully and Mulder stand strong as themselves. While S9 Scully wilts and becomes a background character in her own narrative (which began in Essence-Existence, AHEM, ahem) and S9 Mulder breaks his character off the bat by leaving (even if Scully asked him to... which she wouldn't, given what happened in Essence), S8 Scully doesn't put up with anyone's condescension, making her own-- good and bad-- choices based on established personal work and growth; and S8 Mulder keeps the core of his character in tact-- regressively and progressively-- as he works through the fresh angle of abduction PTSD. We can track Scully's determination, fire, doubts, and fears exactly where Season 7 left off; and we can watch her stretch and grow as she's forced into Mulder's shoes-- so much so, that it's harder for her to walk away from the files to an extent, than her former partner. Meanwhile, DD came back to the season fresh from other acting jobs and injected Mulder's (neglected) trauma with as much nuance as he could. (The lack of exploration for Mulder's PTSD is, by far, the season's largest demerit; and that hinders-- read: butchers-- the finale two-parter because none of Mulder's actions and reactions are properly explained.) I thoroughly enjoy Doggett: his introduction as Kersh's operative and his journey to overcome his mistakes was one I would happily rewatch any day. He's a great character that the writers misused, too-- creating one-off, "going nowhere" episodes just to "explore" him more (which were wastes of screentime, by and large.) By far, his best moments were alongside Skinner (who he becomes tight with), Scully (who he advocates for), Mulder (who he keeps trying to understand), Kersh (who he loses respect for), and Monica (who is here-and-gone; but provides an interesting dynamic, nonetheless.) Skinner is gold in every scene (and that stays strong, no matter how badly written the seasons or movies are); Monica is okay, though not a strongly defined character; Kersh is perfect to hate.

Season 6 is great, great fun: unlike Season 7, it doesn't lose focus on what beats are important to maintain (and DD hadn't burnt out completely, so there's that.) My preferred cup of tea is MOTW over mytharc; and this season wraps up the latter decisively. (Perhaps that factors into this decision.)

Seasons 1 and 2 are just wonderful; and, lo and behold! The mytharc is kept to a minimum-ish. Season 2 mostly revolves around the narrative of Mulder and Scully working through their issues on-screen (...and, now that I think of it, I'm beginning to see a pattern.)

FTF is spectacular, no notes.

Seasons 4 and 5 aren't a particular favorite-- angst isn't my preferred rewatch material-- but I do love their early (and one or two middle) MOTW episodes. I acknowledge, however, that the episodes in these seasons are incredible; but, again, objectively great, subjectively eh. (Great fodder for analyses, though. ;)) )

Season 3 is so tightly knit to the mytharc that it falls into a greater "meh" category for me. (It's not incredibly satisfying when I know said mytharc falls apart, reinvents itself stupidly, then self-destructs only to reinvent itself even stupider. Over and over and over.)

Season 7 is the slapdash "we're almost done!" season. It has some great-- though cracked here-and-there-- moments; and Mulder and Scully had fun having fun. But the MOTW quality really suffers, and that's the bread and butter for this season. Not to mention the mytharc quality, which really suffers; and if not for the acting, S7 is narratively unsatisfying.

The Slop, as I shall call Seasons 9-11, are just so, so poorly handled. Most agree Season 9 has some great MOTW; but Scully's characterization is broken, and she becomes a sidekick to the Doggett and Monica Show instead of a lead on The X-Files. (I'll forever wish GA had stuck to her guns and not renewed a contract for Season 9; but CC kept asking her to, so, here we are.) I put this before Season 11 only because I haven't watched it (though I know each plot point in its entirety.) Season 11 is incredibly hit-and-miss. The good MOTWs always run into a snag that unravels the logic of the episode; and the bad MOTWs (and both mytharc episodes) are bad. Mulder and Scully haven't grown or progressed as characters, despite their age and relative experience-- in fact, they become less intelligent; and are given impossible abilities and impossible chances to escape death without proper explanation. (The main series put Mulder and Scully in impossible situations many a time; but always set up another logical factor or explanation to get them out of it. When they didn't, that was a pronounced failing, too. The main series, however, did not dim their intelligence for plot-convenient reasons.) IWTB's MOTW is abysmal (my rants are here and here); and Mulder and Scully whiplash between in-character hesitations and mean-spirited unintelligence. Season 10 is by far the worst of the batch: no internal consistency, be it characterization, plot, or narrative follow-through. (You can find my rants under the Revival Reviler's first-time watch through hashtag.) A failure on all levels. Side note: let me be clear-- if we compare Season 10's worst episode (one of the Struggles) to Season 11's worst episode (My Struggle IV), the faultier season for characterization would be 11, hands down, because it has a higher fall from grace.

Anyway! Those are my thoughts. :DDD Always open to change them if I hear better alternative reasoning~.

#asks#anon#xf meta#thoughts#mine#ranking the seasons#thanks for droppin in~#this required a bit of thought#S8#S6#S1#S2#S3#S4#S5#FTF#S7#S9#IWTB#S10#S11#thanks for the ask :DDDD

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Forex Ninja’s Guide to Cracking the Code: Depth of Market Meets Labor Force Participation Rate It’s not magic; it’s strategy! The Forex world thrives on two truths: success comes from understanding the market’s nuances, and mistakes often feel like hitting "sell" instead of "buy" during a breakout—cue the sitcom laugh track. In this guide, we’ll dive deep into "Depth of Market" (DOM) and the "Labor Force Participation Rate," revealing hidden opportunities most traders overlook. Let’s break down these advanced concepts with humor, strategy, and a dash of empathy. Peeking Under the Hood: What Is Depth of Market (DOM)? Imagine DOM as the guest list for an exclusive party—it shows who’s in, who’s out, and who’s waiting by the velvet rope. Depth of Market visualizes all active buy and sell orders for a currency pair, providing a transparent view of supply and demand. How to Use DOM Like a Pro Ninja - Spot Hidden Liquidity Pockets: Identify price levels where large orders cluster, signaling potential reversal zones or breakout opportunities. - Front-Run Market Moves: Traders can spot big institutional players and ride their coattails for safer trades. - Avoid Stop-Loss Magnets: Recognize price points likely to trigger cascading stop orders and steer clear. Ninja Insight: Think of DOM as a treasure map. Ignore it, and you’re wandering aimlessly. Master it, and you’ll pinpoint the X marking untapped profits. Labor Force Participation Rate: The Silent Market Mover If DOM is the party guest list, the labor force participation rate (LFPR) is the weather forecast—it sets the tone. LFPR measures the percentage of working-age individuals engaged in the workforce, a subtle but powerful indicator of economic health. Why LFPR Matters in Forex Trading - Predict Interest Rate Shifts: A rising LFPR hints at economic strength, potentially leading to higher interest rates. - Gauge Economic Trends: A declining rate might signal stagnation, prompting central banks to introduce stimulus measures. - Spot Currency Strength: Countries with robust LFPR often experience stronger currencies due to higher productivity and growth. Hidden Opportunity: Combining LFPR data with currency-specific news can highlight currency pairs with increased volatility and trend predictability. For example, monitor LFPR trends before major central bank meetings to gain an edge. Where the Magic Happens: DOM Meets LFPR The real wizardry begins when these two metrics collide. Here’s how to connect the dots: - Timing Market Entries with Precision: - Use DOM to identify liquidity levels. - Cross-reference with LFPR trends to predict macroeconomic shifts. - Creating Advanced Trading Plans: - When LFPR rises, focus on bullish setups for currencies linked to economic strength (e.g., USD). - Use DOM to pinpoint the best entry and exit points within those setups. - Mitigating Risk Like a Boss: - Align stop-loss placements with DOM liquidity clusters and economic data insights from LFPR. Case Study: USD/JPY and the "Labor Whisper" Effect Let’s unravel this with a real-world example: - Scenario: Japan’s LFPR sees a surprise increase, signaling economic momentum. - Trader’s Plan: Combine this data with DOM insights. - Spot key support and resistance levels. - Enter long positions near liquidity pools with low slippage risk. - Outcome: The combination of macroeconomic foresight and micro-level DOM analysis results in a calculated, high-reward trade. Pro Tip: Always backtest similar scenarios. History may not repeat, but it often rhymes. Common Myths (Busted) About DOM and LFPR - Myth: DOM is only for scalpers. - Truth: Long-term traders can use DOM to time entries during periods of high liquidity. - Myth: LFPR has no short-term impact. - Truth: LFPR shocks often precede sharp market moves, creating short-term opportunities. - Myth: You need expensive tools to track these metrics. - Truth: Many brokers offer free DOM data, and LFPR stats are publicly available via economic calendars. Elite Tactics for Depth of Market and LFPR DOM Mastery Checklist: - Use multiple timeframes to spot significant liquidity clusters. - Monitor DOM during news releases for high-probability trades. - Avoid overreacting to small order imbalances—focus on larger trends. LFPR Ninja Secrets: - Pair LFPR data with unemployment figures for deeper insights. - Study historical patterns—high LFPR correlates with bullish trends in developed economies. - Incorporate LFPR analysis into fundamental trading plans to predict long-term shifts. Wrap-Up: Turning Data into Dollars The Forex market rewards traders who dig deeper. By mastering "Depth of Market" and leveraging the "Labor Force Participation Rate," you’ll unlock hidden opportunities and gain a competitive edge. Think of these tools as your secret weapon—use them wisely, and the profits will follow. —————– Image Credits: Cover image at the top is AI-generated Read the full article

0 notes

Text

I need to truly take the faith into myself and make it my own, with my own individual prayers and devotions. It is so easy for me to ride on the coattails of my husband's much stronger faith, and completely neglect building up my own. But when I am by myself, out of the house, just going about my day, I do feel the love of God and warmth in my heart at the knowledge that Christ died for me, too. My husband has a much more forceful and overt approach to the faith, whereas that does not really work for me. So when my only prayer is with him, and my only spiritual discussions are with him, I find that I don't really profit much. I love to pray with him, but I'm understanding that if I do not put my own work in and make it my faith too, I am only hurting myself. I suppose I should talk to other women more, but I am not often inclined to talk to others.

How to phrase it to my spiritual father? I've mentioned it in confession before but I don't think I've really been clear. I guess I just feel a bit stifled, or overshadowed, or I guess just like there's no room for my own spirituality when his is so firm. I feel discouraged from trying. Which is no excuse, but I do feel that there isn't much room for me, even though he has his own prayers and such totally separate from me.

0 notes

Text

"if all this was true , why even waste your time ? why be with me in the first place ?" she didn't do relationships , either . not really . mostly hook ups , something to forget -- to pass time , to quiet the demons in her head telling her that no one loved her , so much so , that her mother left her permanently because she couldn't handle taking care of her . took all of two years of effy being alive and that was enough for reid to go -- that's what it felt like ; a bad aura , like anything she touched would disappear and leave her forever . death was always riding her coattail and now here he was , telling her that going with him would have been worse . supposed he was right . she was never a good person to begin with . tongue pushes to the roof of her mouth , fingertips gnawing at the sleeves of her shirt , "you and i have that in common ." gestures towards him , "we both aren't shit ." squares her shoulders to give herself a sense of direction , like she was stronger than she looked , but she just felt lost and confused . always taking the wrong turn , looking for things in the wrong people . the wrong substances . "sorry isn't going to help you ," still remembers waking up the next morning and finding him gone . called and he never answered . "you left me !" voice gravels as it raises an octave , "you left me all alone !" she couldn't forgive that . swallows to wet her mouth , forcing the boulder that seemed to nestle in her esophagus down . "you made your bed , now go lie in it ."

" it would've made things worse , if you did " ever the pessimist , but he had what happened with his parents to show for . all their calls he declined day and night , the conversations he refused to participate in and even the arguments he'd start with one of his dads simply because he couldn't deal with his feelings . it had turned him mean , grief . it was a turmoil every single time he'd wake up and another one when he'd go to bed . his sister was everywhere and nowhere , at the same time . leaving town was the best choice for himself , surely he could see that now , but the way he went about it would never appease the voices in his head . " i was not going to be a good boyfriend then , or a good anything " had barely made friends for the first six months he was on the team , his voice unknown to his teammates until he slowly started opening up . " i'm sorry , for leaving and for not saying anything after that " tears in her eyes send a shiver down his spine , emptiness building up a hole inside his chest to make it impossible for him to breath . " i am sorry for everything , effy . " and much more , much more he could even put into words . " i— there's no way to change what i did , i know that . " feels pressure behind his eyes , shifting his gaze to the floor out of cowardice — never one to be fine with people seeing him cry , even if it wouldn't be the first time for them . " i just wish i could still have you in my life "

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunrise meant it to be really view altering when they decided to pit themselves with making Moroha into a green-screen character in order to uplift the twins. They probably wanted to return the favour to Sesshoumaru, how he was used at one point to uplift Inuyasha’s legitimate empathy towards the human race. But was Inuyasha truly an all empathic guy? No, he wasn’t! He started out as an equally selfish guy as did Sesshomaru. But what did make Inuyasha look good was the on-field comparison between the brothers in the first few episodes.

How Sesshomaru, very heartlessly ripped out Inuyasha’s eyes when the boy infact had nothing to do with hiding the pearl.

How Sesshomaru’s desire to monopolise the Tessaiga’s power was equally contradictory to Inuyasha’s desire to not wanting the heirloom.

How Sesshomaru’s blatant display of power rendered the audience questioning whether his desire for the sword was even justified when Inuyasha clearly needed it more.

But was that really all that it had to it? I still truly feel Toga had highly neglected Sesshoumaru. Ya, many would argue that the guy had all power and needed things to happen that way in order to make his character grow, and probably Toga saw it that sams way. Still, was giving a rejected and discarded technique in form of Tensaiga really necessary? Was it truly necessary to force Sesshomaru’s neck into protecting his brother by riding on the coattails of his respect towards Toga? I still think and will continue thinking that was really low of the Taisho. He truly disrespected Sesshōmaru.

So now was it really so barbaric for Sesshoumaru to go out and seek for an heirloom which would have made him into an all powerful guy? I mean, wasn’t Inuyasha also gonna use Shikon for a powerful demonic existence?

Still all the above comparisons actually faded out more when Sesshoumaru miraculously changed into a character that would be revered by a lot of fans. Was he still not grey on the edges? Yes, he was, period! But that is what really made him into the anti-heroic existence all of us fans loved so much. Yet so, was Inuyasha’s character or popularity compromised? No!

Why is that?

Because that guy also grew along with the rest of the cast. He became that one guy who accepted his shortcomings and wanted to grow stronger to protect his comrades, making him equally respectable.

But what did Yashahime do?

If they truly wanted to return the favour to Sesshoumaru by making Moroha a bleak paper character in order to uplift the twins, then they miraculously failed. Because honestly it felt like Moroha was the one who grew up the most, had the most honest personality and truly had some serious OP powers. Shit, seems like Taisho once again favoured Inuyasha. He actually passed down his powers to Moroha,

Now, that is what we call a slap to Sesshoumaru’s face.

Sunrise spectacularly failed in making a hero out of the twins and in return absolutely crushed all their purpose in making them shine on Moroha’s expense. Because to me it seemed, Moroha shone the brightest!

#inuyasha#anime#anti yashahime#anti sessrin#sesshomaru#hanyou no yashahime#yashahime moroha#inu no taisho#anti sunrise

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bathed in Flames.

Hello, I wrote a little something. I also posted it on AO3 if you’d rather see it there.

rating: G || no warnings || fandom: atla/atlab || character(s): Zuko, Mai ||

additional tags: other main characters mentioned, vignette, angst, Zuko-centric, Zuko’s scar, angst and feels, teen angst, guilt, dysfunctional family, family issues, personal growth, bending, Iroh is a good uncle, meditation, dreaming

summary: Three vignettes written about three of my favorite parts Zuko's character arc: where he came from, what he did, and who he became.

There were times when he didn’t dream. His sleep was left unmarred by troubling visions of destiny or night terrors of dishonor. However, this wasn’t a night of blissful awareness, as most nights were. He was only half asleep, one part of his brain could still hear the crackling of the fire in the center of his chambers as well as the sound of the water sloshing against the sides of the ship. The air was tainted with the smell of coal burning deep within the belly of the ship. The blazing hot life inside the engine called out to him, the flames he could clearly feel licking up his legs and torso, arms and back, until it entirely engulfed him.

It could have been terrifying for someone else to experience. However, it was only natural for him. Firebenders could sense their element when it was in close vicinity, and of course the stronger the source, the more it made itself known to the benders that controlled it.

This was perhaps the only time of the day in which his bending abilities and his sense of fire did not soothe or calm him, ground him or give him balance. When he slipped into his own dreamworld where he couldn’t hold back his ridgid control on his memories, he fell into the deepest pits of despair. The sound of the crackling fire and the sloshing of the water on ship and the sense of the great roaring fire within said ship only brought him back to the day of his Agni Kai.

The torches that filled the viewing benches around the arena crackled the same as the one in his room. The water in the moat around the arena sloshed against the stone structures that confined it as did the sea against his confining ship. The engine rumbled . . .

Zuko distantly felt the rumbling through his bed from the floor. It wasn’t enough to rouse him from his half-aware state because of how long he had been on this Godforsaken ship. Regardless, the rumbling only further enhanced his painful memory. The rumbling was the way the crowd stomped and cheered for the fight between father and son. It was the sound of the searing flames his father unleashed upon him even when he begged for mercy.

The pain was all he could remember after looking up to see the fire reaching for him. The agony remained for days and days afterwards. It smarted him for weeks to come, the skin always sore and hurting. It would never feel normal, always tight and dry like leather. He was lucky to make it out with his eye and eyesight.

Barely aware he was doing it, Zuko reached for his scar, covering it from any further harm. It was a pathetic attempt. His father could sear through his hand and probably his skull as well. The threat always lingered with him. His father was clear that if he were to return to him, Zuko would be killed.

Banging on his chamber door startled him out of his sleepy brooding and into his fully awake brooding.

“What is it?” He snarled.

“Prince Zuko, we have reached the Southern Water Tribe.”

Cruel excitement swirled in his gut. “Gather your men. We disembark as soon as the ship’s nose crosses into their village.”

*

Zuko dreamed pleasant visions for once when he was back inside the Fire Nation’s capital, he was home . It felt right to be there. There was always the bonus of having Mai in his arms. Her hair brushed against his chin and her breathing against his throat. Something about those feelings lulled him into a sense of security.

The dreams, while happy and contented, were sure to bring anguish to Zuko when he woke. He dreamt of the Avatar, alive and well. He dreamt being on the shores of the Fire Nation watching the kid sail through the wind off the ocean on that contraption of his. He kept happily gliding without a care in the world, whooping and laughing all the while. It was almost like the scene took place a hundred years prior. When there was no war and the Avatar had visited the Fire Nation as a normal boy. He had friends here and a good relationship with the people.

Of course, Aang was enjoying himself, as were the other three. Toph had busied herself trying her hand at sand bending a sandcastle, though Zuko could tell she wasn’t a huge fan of it. Katara and Sokka were out in the water with Sokka trying to surf but ultimately failing, eventually Katara bended a wave that was easy enough for her brother to ride on. This only boosted his ego.

Zuko smiled, genuinely smiled, at the scene. Maybe this was paradise? Some idyllic world where the crown Prince of the Fire Nation was friends with the Avatar.

As soon as the vision began, it was swiftly taken away. Zuko stirred, feeling the coattails of happiness in its wake. He opened his eyes to the choice he had made. He chose not to fight with the avatar, but against him. His sister had shot down the boy with lightning and killed him, yet gave Zuko the credit. It wasn’t long afterwards that the guilt set in. A myriad of emotions crashed over him. Anguish was the best descriptor. The Avatar’s words echoed to him as he laid there watching his girlfriend as she slept.

If we knew each other back then, do you think we could have been friends, too?

*

It was the day of Zuko’s coronation. He was dressed in robes that reminded him of his father. They were heavy on his shoulders. Or perhaps it was the weight of the responsibility that he now carried. Even though he had not been officially crowned as the new fire lord, he had inherited the position after his father had been forced out. As Ozai’s oldest child, Zuko was set to be crowned and carried the burden of the entire fire nation.

Not even a week ago he was still on the run with the avatar, fighting and sneaking around. He had been starving, imprisoned, shunned, and beaten the first time he had been away from home, right after the Agni Kai. And since then, Zuko has been at his lowest in the past year. He hadn’t even thought he could go lower. Then to be humbled when he joined the avatar’s gang and redeemed himself.

What a journey he had been on.

When Zuko found his own eyes in the mirror of his dressing room, he couldn’t believe the contrast in what he found. He recognized himself, but he had changed so much that he was unsure. He had aged and lost weight, leaving his cheeks hollow and his face gaunt. He was wearing the fire lord’s robes, a sight he never thought to be possible. His hair had grown long enough to be put into a top knot which a hair piece would be placed signifying his new status. It was almost too much to comprehend.

The scar was the only thing that grounded him. It made it unquestionable who Zuko was seeing in the mirror. The person he saw was a product of their journey. Whether the wounds were physical as the scar on his face or invisible as were the ones on his heart, they were testament. They would be his legacy.

He took a deep breath and closed his eyes. He faintly felt the candles and low embers of the incense burning in the room. When he took a breath, the few sources of fire flared and grew brighter. Then, Zuko meditated. Everything he was worried about was being pushed aside in his mind. He thought of Iroh and his tea to help.

The first thing Zuko came across in his thoughts was his sister. Azula was still wailing and fighting for escape. This particular thought was unexpectedly painful to deal with. There was so much driving force between them from their father that once he had been removed, it left this awkward, empty space. He always loved his sister, but it wasn’t like how Sokka loved Katara. It was a cold and distant concern. At times, Zuko questioned if he did actually care. He was afraid that maybe too much time and pressure had permanently estranged them. It felt like they could never be able to pick up the pieces or try to have a semblance of normalcy, but he knew he had to try and bridge the gap. Though, in the state Azula was in, that would be completely impossible. Maybe the healers Zuko sent to her would be able to help her.

He pushed the thought away and made it smoke in his mind. It drifted away.

Aang, Katara, Sokka, and Toph were all going on more adventures. Really they were supposed to be helping people in their transition out of the fire nation’s hold. However, Zuko was sure they were prone to stir up trouble. Deep down he worried for their safety, especially now in the midst of great change. There were already reports of rebellions both in and out of the fire nation. Secret groups were being formed and threats on his life were being sent out. He could only imagine what hung over Aang’s head.

The thought became mist, and drifted before settling on another worry.

His mother was still alive. It was a thought that had been pushing for attention in his mind even when he needed to stay focused. He missed her so much at times he felt like he would implode. The first thing he did when he had the power to was order an investigation into the whereabouts of Ursa. Even so, he was planning a visit to see his father. There was a chance the previous fire lord would at least give him something, but Zuko wasn’t optimistic.

The thought turned to rain. Curiously when he opened his eyes to find the rain he began to feel, he found fat tears rolling down his face.

He wiped them away. They had caught him off guard. No more would his emotions catch him unaware. He needed to be comfortable in his ability to feel them, name them, and, to an extent, control them. His empathy was the tool he needed in becoming a great fire lord. One that Ozai refused to acknowledge during his time in power. Hopefully, Zuko would be able to hold onto it.

Hopefully, Zuko would never become his father.

#avatar#Avatar The Last Airbender#atla#atlab#Zuko#atla zuko#fanfiction#avatar fanfiction#fanfic#ao3#archive of our own#vignette

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

so, my harry potter is no longer epilogue friendly, mainly because i no longer ship hinny. for the most part, i will have harry and ginny try dating harry’s sixth year and ginny’s fifth year, but after their break-up, they realise that they do better as friends, and, also, ginny deserves a better guy than someone who would really break up with her just to “protect her”.

canon divergent notes post-voldemort’s defeat:

harry, hermione, AND ron return back to hogwarts for their “seventh” year. while both ron and harry would have been fine not going back to school ever, hermione pointed out that harry hates riding on the coattails of his success and getting a job after defeating voldemort without sitting for his NEWTs would essentially be that. so, all three of them decide to return to hogwarts, which is necessary, as they don’t all know NEWT level stuff ( hermione does, but, well, it’s hermione ).

that entire generation of hogwarts students are a little bit delayed in classes by one year. essentially, everyone has to retake the year, so half of the first years are new students and the second half of the first years are returning students to retake their first year, etc.

there are a lot of funerals and trials that go on during harry’s “seventh” year. harry makes sure to visits every single one of the funerals, but some of the trials take place while he’s in school, so he doesn’t feel the need to go to all of those.

he does go to the hearing for draco and narcissa malfoy, and he gives testimony that allows narcissa to escape azkaban and draco to go to azkaban for only one month ( as much as harry doesn’t want draco to necessarily go into azkaban, draco did do crimes that he had to do time for, but harry’s testimony changed one year to one month + fines ). lucius malfoy returns to azkaban for several years, but harry doesn’t offer testimony to help him get out of azkaban.

during this time, he also gives testimonies to make sure severus snape gets an order of merlin, first class, and is exonerated for dumbledore’s death considering it was more of an assisted suicide rather than murder. he also makes sure to clear sirius’s name since that is very important to him.

after they sit down for the NEWTs, hermione goes into law and harry and ron go into the aurors as harry still feels a responsibility to catch the death eaters still at large. harry and ron get accelerated training in the auror program so that they only train for six months instead of the required one year.

it takes harry and ron one and a half years to capture all of the death eaters who fled. harry quits the auror force after the last death eater is caught as he’s done with fighting for a lifetime, while ron continues on as an auror.

after harry quits working for the aurors, harry isn’t quite sure what to do, so he decides to travel for a bit and to just... stop being so totally involved in the ministry and find himself. so, he goes on a journey, sometimes joining luna on her travels, for about two years.

harry, of course, manages to find danger every so often and helps out people often, and manages to learn a lot of new skills and how to deal with things that he didn’t know before he went on his journey.

harry also finds his powers grow exponentially as ( he realises this later ) his mother’s love protection that kept voldemort’s soul fragment inside of him from influencing him too much was also running on his own power, so about half of his magical power was tied up into fighting off voldemort’s soul fragment. without it, his power started to grow and grow faster and much stronger.

by the time he’s thirty-five, he’s long-since surpassed albus dumbledore and voldemort in pure power, helped along by the fact that he’s also still the master of death.

after travelling for two years, harry returns back to britain and becomes the DADA professor at hogwarts. he also bites the bullet and partially becomes a politician, mainly to help out hermione ( who doesn’t really need help but values it anyway ).

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

so, my harry potter is no longer epilogue friendly, mainly because i no longer ship hinny. for the most part, i will have harry and ginny try dating harry’s sixth year and ginny’s fifth year, but after their break-up, they realise that they do better as friends, and, also, ginny deserves a better guy than someone who would really break up with her just to “protect her”.

canon divergent notes post-voldemort’s defeat:

harry, hermione, AND ron return back to hogwarts for their “seventh” year. while both ron and harry would have been fine not going back to school ever, hermione pointed out that harry hates riding on the coattails of his success and getting a job after defeating voldemort without sitting for his NEWTs would essentially be that. so, all three of them decide to return to hogwarts, which is necessary, as they don’t all know NEWT level stuff ( hermione does, but, well, it’s hermione ).

that entire generation of hogwarts students are a little bit delayed in classes by one year. essentially, everyone has to retake the year, so half of the first years are new students and the second half of the first years are returning students to retake their first year, etc.

there are a lot of funerals and trials that go on during harry’s “seventh” year. harry makes sure to visits every single one of the funerals, but some of the trials take place while he’s in school, so he doesn’t feel the need to go to all of those.

he does go to the hearing for draco and narcissa malfoy, and he gives testimony that allows narcissa to escape azkaban and draco to go to azkaban for only one month ( as much as harry doesn’t want draco to necessarily go into azkaban, draco did do crimes that he had to do time for, but harry’s testimony changed one year to one month + fines ). lucius malfoy returns to azkaban for several years, but harry doesn’t offer testimony to help him get out of azkaban.

during this time, he also gives testimonies to make sure severus snape gets an order of merlin, first class, and is exonerated for dumbledore’s death considering it was more of an assisted suicide rather than murder. he also makes sure to clear sirius’s name since that is very important to him.

after they sit down for the NEWTs, hermione goes into law and harry and ron go into the aurors as harry still feels a responsibility to catch the death eaters still at large. harry and ron get accelerated training in the auror program so that they only train for six months instead of the required one year.

it takes harry and ron one and a half years to capture all of the death eaters who fled. harry quits the auror force after the last death eater is caught as he’s done with fighting for a lifetime, while ron continues on as an auror.

after harry quits working for the aurors, harry isn’t quite sure what to do, so he decides to travel for a bit and to just… stop being so totally involved in the ministry and find himself. so, he goes on a journey, sometimes joining luna on her travels, for about two years.

harry, of course, manages to find danger every so often and helps out people often, and manages to learn a lot of new skills and how to deal with things that he didn’t know before he went on his journey.

harry also finds his powers grow exponentially as ( he realises this later ) his mother’s love protection that kept voldemort’s soul fragment inside of him from influencing him too much was also running on his own power, so about half of his magical power was tied up into fighting off voldemort’s soul fragment. without it, his power started to grow and grow faster and much stronger.

by the time he’s thirty-five, he’s long-since surpassed albus dumbledore and voldemort in pure power, helped along by the fact that he’s also still the master of death.

after travelling for two years, harry returns back to britain and becomes the DADA professor at hogwarts. he also bites the bullet and partially becomes a politician, mainly to help out hermione ( who doesn’t really need help but values it anyway ).

sometimes he does do consultations with the aurors or helps them out with missions, but, with the latter, it’s very rarely.

0 notes

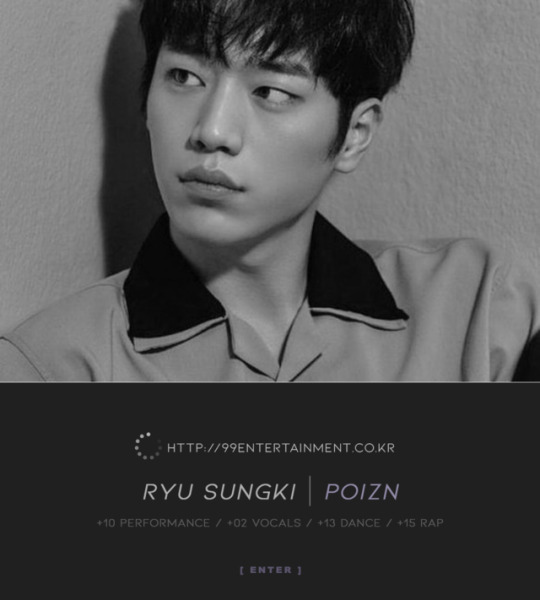

Photo

[ LOADING INFORMATION ON POIZN’S LEAD RAP, LEAD DANCE ZEN…. ]

DETAILS

CURRENT AGE: 26 DEBUT AGE: 20 SKILL POINTS: 02 VOCAL | 13 DANCE | 15 RAP | 10 PERFORMANCE SECONDARY SKILLS: Lyric writing

INTERVIEW

ZEN is made of contractual obligations and tightened puppet strings stitched to every joint in his body, invisible ties piercing bones, making him move to the whims of those who hold all the power. all because he signed his youth away, thinking he’d get a shot at making it big. alone. solo. a one-man act.

what he gets is a group. baggage. expectations to be a team player drilled into his head since the announcement of poizn’s lineup so many years ago.

for someone so selfish, so determined not to let anyone in, it’s a wonder how 99 ent. managed to shatter his resolve and replace it with a ghost of a boy, who would do anything they say to keep his ugly past buried, kept under lock and key, and confidentiality.

do as you’re told and we will make sure no one knows who you were. disobey and you will never get a chance at that solo you desperately want.

so he drowns himself in silent threats, fashions himself a persona for protection. (after all, ZEN is more shield than sword.)

ZEN is a collection of almosts. caught in between white lies and bits and pieces of the truth. every word he says is borne out of a calculation—a subconscious scheme—to memorize people’s shortcomings, their desires; to dig out their secrets and exploit them when he’s finished.

variety shows like his go-getter attitude. appreciates the way he chuckles at lame stories, encourages and draws from him exaggerated (often fabricated) stories about his members and their lives as trainees and as full-fledged idols. they like his sharp wit and clever savagery, praise his comedic timing and his natural capacity to read the atmosphere and gauge reactions.

so he digs himself a niche in the handful of appearances he makes on network tv during promotion cycles. smiles like his life depends on it. smiles until his cheeks hurt. smiles until the cameras turn off and he bows his farewells. smiles until he’s enveloped in the darkness of his room in poizn’s dorms and he writes himself sick.

he makes a name for himself until, one day, he goes off-script. disobeys. he steps over the line and says something he shouldn’t have. makes a joke about someone whos off-limits and way out of his league (practically untouchable) that falls flat—is misconstrued and taken as full-on offensive. it doesn’t matter if it was intentional. a mistake. the backlash he gets comes on the heels of fans turned antis, people who used to tolerate his edgy attitude and borderline controversial remarks, excusing it as him being witty and sarcastic. it’s part of his charm is not enough of a blanket phrase to save his hide or his damaged reputation.

99 ent. releases a statement, forces him to write a letter of apology and self-reflect. behind closed doors, he’s told to lay low. not show his face. so he does what he does best—he goes into hiding for several months, haunts the practice rooms in an attempt to pull himself back up. all the while the public divides itself cleanly into two: those who forgive and forget and those who remember and are out for his blood.

five years have passed since his juvenile blunder and he wonders if he’s safe. wonders if he’s forgiven. wonders if he can keep pretending this monotonous life is something he still wants. if the stage and the lights and the screaming fans are worth the way exhaustion creeps underneath his skin, seeps into bone, poisons the nerves.

wonders if anyone is capable of seeing through him at all.

(to the lost, lonely boy he keeps locked in his rib cage, in the tiny sliver of a bleeding heart he houses in the confines of his chest.

a boy buried under a man named ryu sungki, who is all too consuming, too much, too dangerous—a predator.)

SUNGKI wears danger like a second skin. walks a fine line between pure nonchalance and vague belligerence. uses people like pawns. tosses aside has-been’s and groupies like yesterday’s trash after he’s done. drapes layers and layers of distorted versions of himself that people love (to hate, to fuck)—he is whatever you want him to be. until the sun rises and he’s gone, as if he’d never been there at all.

he’s neither here nor there. an perpetual in-between. always lingering on this precarious divide.

SUNGKI cares for no one—not even his members—but himself. the climb to the top has always been a one-man war and he’s long since abandoned his comrades (those trainees back in the day who thought they could ride on his coattails, use him, exploit him. fools.) in favor of surviving. self-preservation nothing more than pure instinct to remain the last one standing.

he has no sympathy for the weak. can’t fathom setting himself aflame to keep others warm. he’s got chaos in his bones. he’s a storm in human skin and all those who stand in his way will always get caught up in his mind games.

don’t try to shape him into something pure. don’t try to save him. don’t play with hellfire if you don’t want to get burned. and, most of all, don’t fall in love with him.

because he will love you raw, broken, and dirty.

because he will kiss an i love you into your skin and murder you when he leaves and never comes back.

(haven’t you heard?

he’s the bad boy mothers warn their daughters away from.

he’ll love you like you’re his first, touch you like you’re the only thing that matters. he’ll turn your body into an altar, your mouth a confessional, and he will worship you like a sinner trying to find something holy—redemption—inside your body.)

BIOGRAPHY

ONE.

he’s born on a blazing summer day to two barely adults out of wedlock.

his mother cries. his father curses. and the nurses slip away, turning a blind eye to the sudden makeshift family of three.

the second time he wakes, he is home. and home is a tiny apartment in dalseo-gu, dirty dishes piled high in the sink, and week-old leftover takeout growing mold in the refrigerator.

home is also the cradle of eomma’s arms and a soft, tremulous whisper calling, sungki. sungki-ya~

for two years, it’s just the three of them in their little corner of the world and they try to make it work. his father juggles two part-time jobs to make ends meet: when the sun rises, he’s got his hard hat on and all sungki remembers is the hunch of his shoulder and the bend of his back; when the sun sets, father leaves dinner half-finished at a quarter to six, commuting his way to a gs25 in the heart of daegu for his closing shift.

his mother stays at home, trapped inside a dingy apartment with a fussy baby boy who doesn’t understand that she’s human too.

they scrape by stretching won to won. eat enough to call themselves half-full. sleep enough to trudge through another monotonous day. love each other enough to stay together for a little while longer.

TWO.

happiness comes in fragments.

it’s the sound of eomma’s soft humming, singing about canola flowers and the riverbanks of nakdong, of a love that caresses and warms the soul, of bygones and fleeting youth. it reeks of nostalgia and lost time—of a life she no longer gets to live.

it’s father smiling, lulled half to sleep by her gentle voice and sungki’s offbeat clapping and nonsensical babbling. it’s endearing. all kinds of tender and soft.

it’s endearing, still, when he starts to crawl, starts to walk, little legs struggling to hold him up, his voice stronger and louder. his babbles now strings of sentences and fragmented lyrics. he sings eomma’s sad ode to her younger self once in a voice made of honey and ripe with emotion he doesn’t quite understand and she cries.

it’s the first time since birth that eomma cries like that: all brokenhearted and hurting. sungki-ya, sungki…my beautiful boy.

it’s the first time sungki cries too.

don’t cry, eomma. it’s okay. sungki is here. sungki loves eomma. don’t cry, please.

THREE.

he’s three when he learns the saddest words in the dictionary. it’s stay followed by please don’t go trailed after a whimpered, half-choked eomma is sorry.

three and still a boy (just a boy) when he learns to associate abandonment with the sound of the door clicking shut in the dead of the night, to dial tone, to come back come back come back’s left unanswered.

father tells him in drunken rages not to miss someone who won’t miss them. tells him with a fist to the face that he was not enough for someone like eomma to stick around for.

tells him, after, cradling his bruised body to his chest that he can’t deal with loneliness by waiting next to the phone, by the door, by making excuses, by praying. (because what’s god to a non-believer. what’s god to powerless people.) eomma is never coming back, boy. you chased her away.

sobriety comes in ripples; its effect turning every day into a perpetual hangover. a rinse-wash-repeat cycle that always ends with sungki taking the brunt of his father’s addiction to the bottle, watching him try to find solace in the bottom of a glass, grasping at redemption with cracked hands and blood in his mouth.

home becomes a cesspool of false hope regularly beat out of him. home becomes a dumpsite of bodies—all his; year round, for years to come. home becomes a space. just a space. void of happiness but full of struggles.

home is just home. until it’s not.

FOUR.

he leaves this hellhole inside four walls behind on a sunday.

abandons a man he no longer recognizes as his father. (hasn’t even called him that since the day he cracked his head open on the kitchen counter. the scar’s a nasty reminder; a permanent blemish for him to reminiscent about when insomnia and his father’s guttural sobs keep him awake at night.)

because the day the authorities come for him is the day he loses what’s left of a flimsy thing called family. child protection services come swooping in like belated grace and the courts deem his father unfit to care for him. mother is nowhere to be found—she hasn’t been in his life for the past decade, so he’s shuffled along an assembly line of cold and distant relatives who want nothing to do with a troublesome boy like him. who wash their hands clean of him by claiming too much responsibility, financial burdens of an extra mouth to feed. shuffled along until someone finally gives in. takes the plunge.

like this, he’s sent straight to the heart of the big city to live with his grandparents, people he’s never seen hair nor hide of; who were only mentioned in passing since his mother showed up on their doorstep pregnant and afraid.

seoul is a collection of bright lights, white noise, and too many people.

harabeoji is stern and righteous. nothing like his own father, who is wasting away, lost in the aftermath of failures and the monotonous routine that’s his life. sungki never saw him coming. never expects to be taken in with kind intentions and gentle hands. never knows what to do with his own hands but clasp them in his lap as he’s gestured to sit at the table by the stoic face of his grandfather and the kind eyes of his grandmother.

dinner is a simple affair: a heaping bowl of rice, a mountain of kimchi, a big pot of seaweed soup, and a whole thing of galbi. he must’ve made some sort of noise—animalistic and pitiful, perhaps—because suddenly, there are arms wrapped around him, warm and safe, and halmeoni’s voice saying, it’ll be okay. you’ll be okay, child.

it’s only then sungki realizes he’s crying.

brokenness is the scars the old couple notice littered and scratched along his back. a decade of untold horrors and bottled up pain.

loneliness is quivering hands slipping ‘round halmeoni’s waist, bunched around soft fabric and choking sobs of grief.

(eyes empty, face haunted. he’s just a boy who’s seen too much. felt too much. hurt too much. still a boy. broken, bleeding, and blue.)

FIVE.

harabeoji tells him to channel his anger—the innate violence—into something else. tells him to shape the tremor in his bones and the adrenaline in his veins into hypermotion. you must learn to control your temper. turn that negative energy into something positive—something that drives you, something that will help you in the future, harabeoji says the first time sungki tells him he’s a whole mess of pent up anger, a body full of hatred towards the world (towards fate and circumstance—for the life he’s been dealt. how unfair it all seems).

he’s thirteen and starving. wanting to put this twisting shard of despair and bleeding cruelty somewhere. anywhere. (he doesn’t want to be like his father. wants to learn to be good. better. stronger.)

so he finds himself a makeshift home in hard-hitting lyrics that speak of injustice and the world’s cruelty, that remind him that he’s one of many who don’t live in the lap of luxury, who don’t have the privileges that those who are more fortunate are born with. drowns himself in loud music and gravel-like voices who are just as angry as he is at the world.

soon, every day is a fight to build up his walls, his defenses, encasing his heart in maximum security. warning: danger ahead. no trespassing allowed.

halmeoni approaches things differently. handles him with care. his salvation comes in the wonky radio sitting on a dusty bookshelf; the only thing keeping him sane when he wakes up at the ass crack of dawn to deliver porridge to people’s doorsteps for what amounts to pocket change and comes home from the monotony of academia, shoulders heavy under the weight of meritocracy and sky-high expectations.

exhausted, sungki dreams of a language powerful enough to fracture jaws, punch through hearts to ignite the soul. dreams of stringing together words that can heal, that can hurt, that can make people feel.

he’s thirteen, still, when he uploads a faceless, free-styled cover of drunken tiger’s good life on youtube. it doesn’t garner much views—just a handful of comments noting the timbre of his voice, the swell of emotion, his potential. the views never go higher than four digits, but sungki makes do with the occasional passing encouragement for more. thrives on it.

one cover becomes two. then, three. five. eventually, he begins covering remixed western artists like jay z and kanye west. his english is mangled at best, his r’s still sound like l’s no matter how hard he tries and his accent still bleeds right through. gruff and rough around the edges. but he finds he likes it—sounding less polished, made of raw potential. a diamond in the rough.

SIX.

halmeoni passes on a spring day and harabeoji stops smiling. (he never stops caring, though. still present, still there. just merely existing now. drowning in his grief.)

sungki stops talking. stops. just stops.

he’s fifteen when he falls through the cracks of society. slips right through harabeoji’s fingers. sungki’s lost now, floating adrift in a sea made of sorrow and hatred for stupid things like fate and circumstances. bullshit. so sungki falls. lets himself plummet straight down. because when someone like him hits rock bottom, there’s nowhere else left to go but up.

at school, he turns himself into a loner; all sharp gazes with an intent to kill aimed at all those who dare to approach. defends himself against schoolyard bullies who picks fights with him, who don’t understand the meaning of do not disturb. defends himself against the harsh tongues of teachers who take one look at his face and his don’t give a shit attitude and declare him a lost cause, lecturing him in and outside of classrooms. like this, rumors start to whisper through the grapevine—ryu sungki’s a bully. he’s bad news. stay away from him. heard he’ll kill you if you even looked at him. heard he beat up someone for stepping on him. heard he talked back to kim seonsaengnim. heard he—all untrue. unfounded. missing context and his side of the story.

but when has anyone ever even bothered to ask him if all this was true. when has anyone ever tried to uncover the truth. when has anyone even cared enough to consider there is more than meets eyes with a boy like sungki?

never.

so sungki doesn’t try to change the narrative. because you can’t convince people to change their minds when they’re so set on believing what they choose to believe.

and a social pariah he becomes.

forever not belonging. forever feeling out of place. neither here nor there.

fitting nowhere.

SEVEN.

sixteen and sungki finds himself underground.

it’s where he finds a niche; a collective of misfits, outcasts, and the resentful strays. fits right in with his newfound allies in a world that spits upon them for not being book smart and upright.

creates himself a language, finally, that breaks the bones of his innocence. fractures souls, tearing hearts wide open.

he writes himself a storm. shaping feelings into words, into hard-hitting metaphors about fucking society and battling fate with a bottle of whiskey, numbing pain by chasing adrenaline, the heady kiss of skin-on-skin, and reckless teenaged rebellion.

his handful of faithful fans on youtube gobble up the once-in-a-blue-moon amateur cover made of a sultry voice crooning love, oozing sex, in the thrum of bass and a deep, raspy voice rapping about size zero and double standards, spitting fire about the disenfranchised and the little people constantly stepped on by the privileged. finds himself a small following seduced by his face cast in shadows and the mystery of a teenager who’s just a survivor, fighting fire with fire.

in the heartfelt, emotional-ridden lyrics he pens in the dead of the night, he digs himself a graveyard, fills it with the remnants of a lonely abandoned child of three and the ashes of a boy barely seventeen.

EIGHT.

he’s scouted leaving his part-time job bussing tables at a hwae restaurant one busy saturday evening. scoffs in the agent’s face when he’s handed a business card, crisp and clean. logo blazed all pristine and perfect across the front. scoffs at the thought of getting streetcasted for his visuals (puberty was a blessing in disguise; his body elongating, filling out nicely, his face losing the roundness of a child and becoming sharp cheekbones and a jawline that could cut. he’s all rough masculinity wrapped up in a leather jacket and ripped jeans, despite smelling like barbecue and raw marinated fish). wants nothing to do with the idol industry. doesn’t want to be a dancing monkey, molded and shaped into something beautiful and perfect in the eyes of the public, singing manufactured songs about bad girls playing hard to get and sex disguised as euphemisms made of clever wordplay and blanket phrases of love sung to generic beats.

he waves them away, shakes his head no, and wanders back home.

it’s only later that he finds the business card tucked innocuously into the back pocket of his jeans and another hiding inside his jacket pocket.

open invitations. temptations.

he sits on it for weeks. months. until harabeoji finds them tucked inside a dog-eared notebook filled with ballpoint ink and smudged lines of poetry and half-finished songs.

it comes as a surprise when sungki’s told to give it a shot. he’s doing nothing but cruise life, anyway. there’s no judgment. just plain fact. sungki has no intentions of going to university. of trying to climb his way up the corporate ladder or save lives with his bare hands. of working a good ‘ol nine-to-five day in and day out.

and with one year to go before he must decide which fork in the road to take, harabeoji asks him to give it a shot. go. do something. anything. you’re just wasting away, sungki. your halmeoni wouldn’t have wanted life to turn you into a ghost. not like this.

so he obeys. because harabeoji asked. because he thinks it’s what halmeoni would’ve wanted him to do—try, to live life, take chances.

he auditions at seventeen with halmeoni’s picture tucked inside his wallet, a microphone a centimeter from his lips, and a song with lyrics about building a home in someone, trying to find peace in the shape of their body, salvation in the press of their lips, redemption in the curve of their spine, love in the sound of their voice.

he makes it in. and it feels like victory.

congratuations, ryu sungki. welcome to 99 entertainment.

(he should’ve known it wouldn’t be this easy. should’ve known once inside, there would be no exit. not without leaving all damaged and bent out of shape.

should’ve known survival was never a one-time battle, but a lifetime of war.)

NINE.

trainee life is torturous. his friends from the outside more hauntings than they are people. the draw of fame and fortune turning them heinous and cruel. harabeoji is his only remaining pillar as sungki struggles year after year to weather the storms of evaluations, of the times he sings himself hoarse and dances himself broken.

he imagines it would be worth it when he finally debuts with the small handful who has bled alongside him. imagines somewhere down the line, the stage and the spotlights and the stadium of fans waving blinding lightsticks would be worth the fracturing of bones and the momentary losses of his voice and the blisters on his feet and the bruises on his skin.

one year into a life made of a revolving door of talent hopefuls and the diehard tryhards, he’s pushed into more intensive training and thrust further into the dog-eat-dog world of rap. it’s reminiscent of his wretched teenaged self—the empty threats, the penetrating i’m better than you, trash gazes of his peers. resentment is palpable and he feels it in the burn of their stares every time he makes gradual progress, makes splashes big enough to garner some praise and recognition from his trainers. he’s got an amateur foundation from youtube days, after all. his accounts now gathering dust, laid to rest in the aftermath of closed doors training and verging on three years of blood and sweat. (no tears. not yet. never.) they must have known about them—his potential, his meager repertoire.

he doesn’t shine so much as ignites under harsh criticism, his temper constantly held at bay (control, harabeoji’s stern voice whispers in his ears every time he catches a backhanded compliment or the passing insult over his improvement by those who’s been here longer, trained harder) by sheer willpower.

as much as he’s doing this because he sees no other possible future for him, he still has his pride. still wants to have something of his own. and he’d be damned if he fucked it all up because he couldn’t take the obvious goading, the taunts, the jeers, the not-so-subtle instances of sabotage.

no, sungki was much stronger than that. petty seniors in this closed world game of survival had nothing on the years he spent curled in on himself in the corner of a dirty apartment, wondering if he’d ever see the light of day. if he’d ever get to stand on top of the world. if he’d make it another day.

a decade and some years now and he’s made it. older, stronger, and meaner. selfishness and his greed to live—to be better than everyone—keeps him going, even as he raps himself hoarse. even as he pushes his body to its limits.

two years in and those who thought he wouldn’t make it past year one are long gone—cut because they couldn’t handle the pressure, couldn’t take the day-to-day scoldings to do better, to work harder, with their backs ramrod straight, their expressions schooled into something resembling obedience.

three years in and sungki’s still here. finds himself living in the practice rooms, his only companion are the booming loudspeakers playing the same song for hours on end, training his body to recognize the ebb and flow, the rocking rhythm of beats.

he’s not a born dancer. had no real foundation in the mechanism of dance. so day in and day out, he watches the choreographers’ movements like a hawk, trains his eyes to watch for every subtle movement, every roll of the body, every pop of his limbs. learns to mimic after weeks, months, of trials and errors—of forcing his body to twist, to pop and lock, to grind, to ride, the beat of the music.

it’s hard—he’s not going to lie. his body wasn’t made for endless days of practice and countless hours of repetition. he knows he lags behind, knows all he’s got is his anger and his notebooks filled with handwritten lyrics (half-finished songs he’s sure will never see the light of day. he’s a nobody, just a trainee. what power did he have to ask them to cultivate this skill left rotting in the wake of molding himself to a precise design, turning himself into something wicked and dangerous, yielding to every demand and command because he wants to make it. needs to make it.), so he works himself to the bone, trying to break his body’s resistance to moves that bend his spine too far, hurts his waist a little too much, makes the joints of his body ache.

he bites back every retort building at the tip of his tongue, pressing at the back of his throat, and grits his teeth.

even as sweat drips into his eyes, down his face, drenches his entire body. even when his voice is nearly gone. even if the exhaustion turns his eyes bloodshot and his temper near catastrophic, he holds himself back on tight reins.

because, perhaps, being a tenacious trainee with both bite and bark and raw potential is the only chance he has to ever making it in a cutthroat world like this.

and if sungki is anything since he’d been born, it is a survivor. do or die trying. and sungki had no intentions to die. so do is all he knows. all he is.

he trains and hones and breaks and climbs back up not knowing he’s being shaved to the wick, all his lingering bits of naivete whittled away to make him sharper, jagged and edgy. it makes him a target. an outlier. unpredictable and dangerous.

-

he trusts no one when he’s selected alongside a fellow trainee and thrown to the wolves in a rap survival show. expected to adapt and mold himself to the rules of the jungle. expected to take the heat and scrutiny with sharp wit and a charming smile.

their success comes with consequences. rumors that 99 ent. bought their near-winner positions sour their reputations, mars their impressions. but sungki doesn’t bat an eye. he’s no longer soft and vulnerable to the opinions of others.

his first taste of fame tastes like sin. like addiction. and he’s hooked.

when poizn debuts in 2011 with him in the lineup, sungki’s no longer the lonely boy of three who wasn’t enough for his mother, who wasn’t strong enough for his father. not the reckless youth who dabbled in the sins of sex and the burn of booze and cigarettes.

not an unmarred saint made to be put on a pedestal.

ryu sungki is more than that—he’s a guilty sinner pulling on the skin of a rogue with his face streaked in shadows, a wicked grin on his lips, and his voice crooning love.

TEN.

one year into poizn’s debut and he already hates it.

hates the flashing cameras. hates the delusional fans. hates being under 99 ent.’s thumb. hates pretending he’s got this nostalgic history with his members and a bright future where they’re all chummy and brothers and are in this together when sungki doesn’t feel an ounce of camaraderie. when all he cares about is how angry he is at being fooled by praises and encouragements. how he was tricked into believing he had the potential and the opportunity to debut solo, only to be shoved into a lineup with four other boys just as ravenous as he is.

hates everything about how he has to watch his mouth. watch his goddamn image. like he’s nothing more than a puppet moving on invisible strings. like he’s just a caricature made for pure entertainment, for the fans and the world to lap up.

rugged, roguish, and reckless. sungki seethes on the inside, even as he forces his body to bow at everyone and everything. the picture of obedience—a dog of this godforsaken industry.

this is what he sacrificed his youth for.

and he reaps what he sows.

-

two years in and he fucks up big time.

and 99 ent. retaliates by removing the possibility of a future solo debut they’d been dangling since the tail-end of his trainee years and threatens him to keep his mouth shut.

of all the things sungki thought he was incapable of, begging was one of them. and yet, in the aftermath of a stormy public waiting for him to show his face so they can pelt him with proverbial eggs and vitriol, sungki had found himself on his knees. head down, tail tucked between his legs, his dignity in shambles.

please, he remembers saying (remembers loathing) with a voice too small, too boyish. ragged. help me. please fix this.

and fix they did.

in return, they asked for absolute obedience. creates in him the very image of a faithful lapdog, a yes man, who doesn’t talk back. who answers at their beck and call. who does as he’s told, commands and directives followed to the letter.

sungki’s reputation is barely restored. he thanks them.

(inside, the hatred for his own weakness tears him apart.)

-

three years ghost by and he does nothing to attract negative press. lies as low as he can. makes the needed variety show appearances during promotion cycles. circumvents any subtle prompts about his juvenile mistake back in the day, apologizes over and over again with sheepish ducks of his head on camera, words twisted to form repentance to convey his reflection and his past immaturity. vows not to make the same mistakes again.

vows to shape himself into someone better.

vows revenge and comeuppance on a company who repeatedly baited him, using his ugly past, his past scandal, and his greed for a solo as ammunition.

he keeps his head down.

(all the while, he holds back a cruel smile. biding his time, waiting for the right opportunity to strike. to rise up.)

-

years four and five are formative.

he meets someone who levels the playing field. who sees through his facade and his chipped masks of tell-tale obedience. see the darkness wrapped around him like hapless shadows. sees the wicked curl of lips and calls him out on his bullshit.

it’s the first time someone does.

it’s the first time someone tries.

and somewhere deep down, sungki rejoices. just the tiniest bit.

because all these years of pretending and, finally, someone is smart enough to notice there lies a crack in his foundation.

smart enough to recognize a predator for what he is—cruel, cold, and callous.

you’re dangerous, she whispers brokenly into his neck as he cradles her close, skin-on-skin. full-on sin and dirty (not) love-making. but i’m not scared of you.

you should be.

so should everyone who dares to approach him, thinking he’ll love them all tender and sweet.

so should the world.

-

seven years in now and the masks are starting to fall one by one.

the lapdog business is getting old and he’s getting restless. jittery.

he’s tired of the years passing by relatively the same. monotonous. all routine. aches for change. aches for chaos. for a little bit of fun. drama. danger.

he tests the waters by goading his members. pushes boundaries, tests patience. drops the act little by little. on camera, he does his best to act as if years spent sweating it out in the practice rooms has forged a brotherhood no conflict can shake. behind closed doors, he ignores them. pretends they’re nothing more than colleagues (aren’t they?). scoffs at the label of family—he doesn’t have one. just harabeoji waiting in the wings, patient and waiting as he’s always been for sungki to soar, to make a name for himself.

that bit of bite begins making an appearance in magazine interviews and one or two variety show appearances where he’s asked the cliched question of where he sees himself in five years, of his goals and ambitions.

he drops hints about the desire to go solo, his intentions on becoming a household name. seven years being muzzled comes undone and, for the first time since the mistake that cost him his pride, sungki disobeys. deviates.

i want to be known as more than just zen, poizn’s charismatic lead rapper and lead dancer. i want something for myself. something to call my own. i want people to know me as ryu sungki.

(want the world to bow at my feet. want the world to chant my name. want them to see me.)

slowly but surely, he creates himself a storm and he the eye.

because his days of being obedient are coming to an end.

1 note

·

View note

Text

How Anti-Fascists Won the Battles of Berkeley–2017 in the Bay and Beyond: A Play-by-Play Analysis

The perilous politics of militant anti-fascism defined 2017 for the anarchist movement in the United States. The story in the Bay Area mirrors that of the country at large. It’s a narrative full of tragedies, setbacks, and repression, ultimately concluding with a fragile victory. Yet there was no guarantee it would turn out this way: only a few months ago, it seemed likely we would be starting 2018 amid the nightmare of a rapidly metastasizing fascist street movement. What can anti-fascists around the world learn from what happened in Berkeley? To answer this question, we have to back up and tell the story in full.

Fascists chose Berkeley, California as the center stage for their attempt to get a movement off the ground. The advantage shifted back and forth between fascists and anti-fascists as both sides maneuvered to draw more allies into the fight. Riding on the coattails of Trump’s campaign and exploiting the blind spots of liberal “free speech” politics, fascists gained momentum until anti-fascists were able to use these victories against them, drawing together an unprecedented mobilization. As we begin a new year, anti-fascist networks in the Bay Area are stronger than ever. Participants in anti-fascist struggle enjoy a hard-earned legitimacy in the eyes of many activists and communities targeted by the far right. By contrast, the far-right movement that gained strength throughout 2016 and the first half of 2017 has imploded. For the time being, the popular mobilization they sought to manifest has been thwarted. The events in the Bay Area offer an instructive example of the threat posed by contemporary far-right coalition building—and how we can defend our communities against it.

2016: A New Era Begins

Clashes escalate outside a Trump Rally in San Jose on June 2, 2016.

The clashes between far-right forces and anti-fascists that gripped Berkeley for much of 2017 were the climax of a sequence of events that began a year earlier. On February 27, 2016, Klansmen in the Southern California city of Anaheim stabbed three anti-racists who were protesting a Ku Klux Klan rally against “illegal immigration and Muslims.” The rhetoric of the Klan echoed the same vulgar nationalism that the Trump campaign was broadcasting. Under the banner of the alt-right, many white supremacist and fascist groups began to use the campaign as an umbrella under which to mobilize and recruit. They aimed to build an ideologically diverse social movement that could unite various far-right tendencies within the millions mobilized by Trump. A reactionary wave had steadily grown across the country in the last years of the Obama era. The combination of continued economic stagnation, proliferating anti-police uprisings of Black and Brown people, and rapidly changing norms related to gender identity and sexuality had spawned a violent backlash. This was the wave that Trump rode upon and his campaign had broken open the floodgates.

Trump rallies became increasingly contentious in cities such as Chicago (March 11) and Pittsburgh (April 13) as protesters held counterdemonstrations to confront these open displays of bigotry. On April 28, 2016, small-scale rioting erupted outside a Trump rally in the southern California city of Costa Mesa. The next day, in the city of Burlingame near San Francisco, large crowds disrupted Trump’s appearance at the convention of the California Republican Party, leading to scuffles with police.

Days later, on May 6, a newly-formed fascist youth organization, Identity Evropa (IE) held their first demonstration on the other side of the Bay—an ominous portent of things to come. This initial experiment was organized by IE as a “safe space” on the UC Berkeley campus to promote “white nationalist” ideas and their particular style of business-casual far-right activism. Inspired by European identitarian movements, IE worked to coopt the rhetoric of liberal identity politics and use the contradictions inherent in those politics to build a new white power movement. Their strategy was part of a larger effort across the alt-right to recruit young people and legitimize white supremacist organizing as an acceptable form of public activism. The rally brought together Nathan Damigo, the founder of IE, with members of the Berkeley College Republicans and the alt-right ideologist Richard Spencer, who flew in from out of town to attend. Although the event was barely noticed, the participants declared it a success and a first step towards building a new nationalist street movement.