#richard berengarten

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Drawn to Words

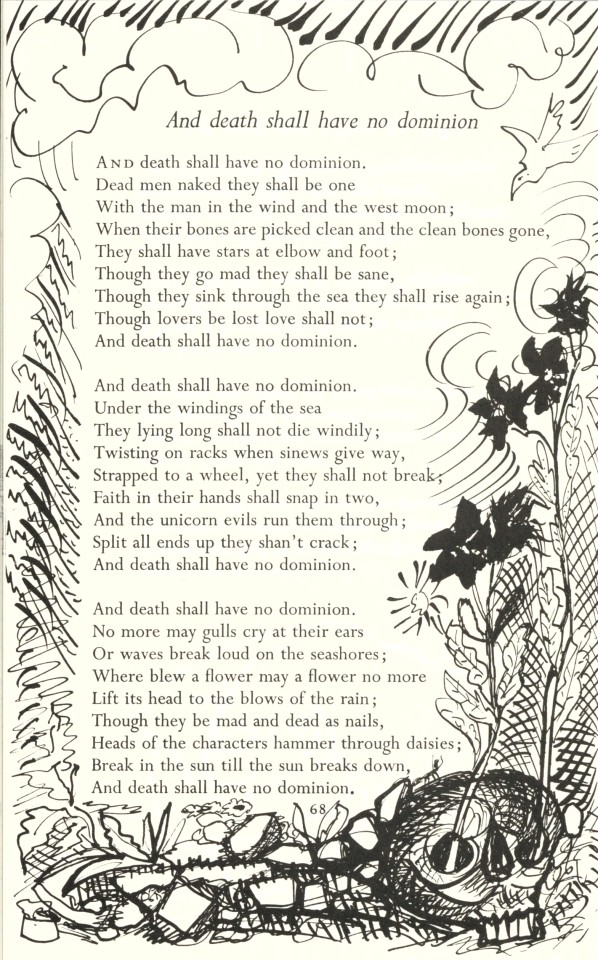

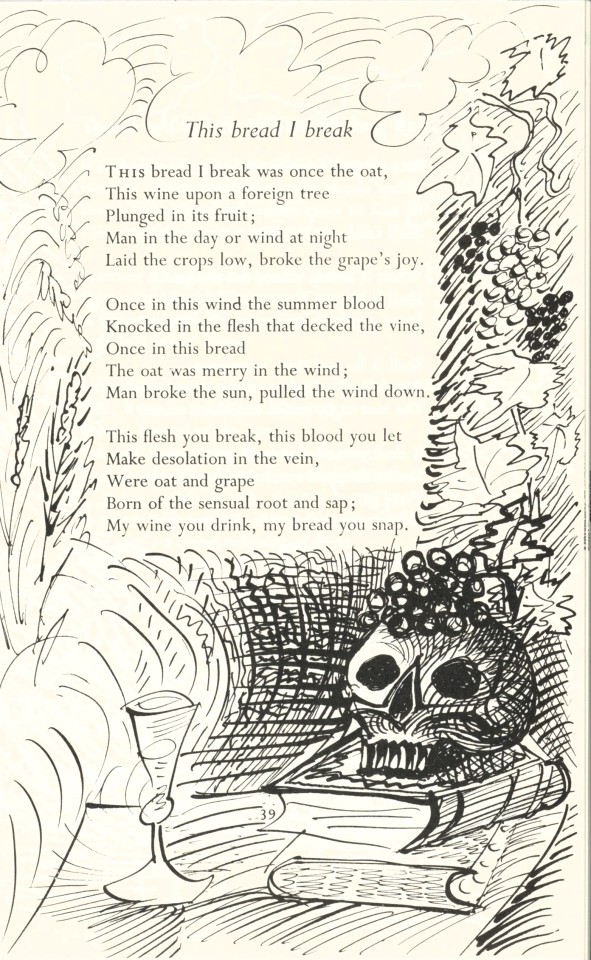

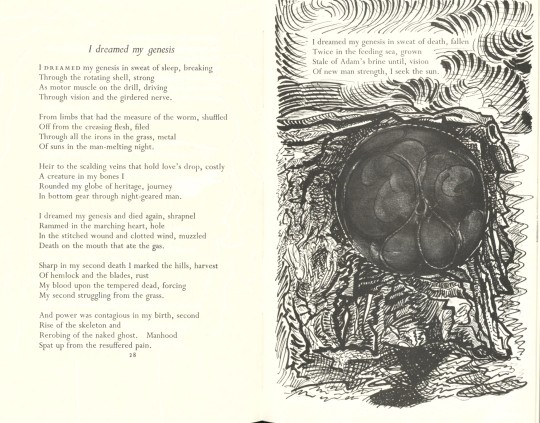

Drawings to Poems by Dylan Thomas is a work that combines notable Welsh poet Dylan Thomas's poetry and Welsh artist Ceri Richards's artwork. Published in London by Enitharmon Press in 1980, it includes an introduction by the English poet Richard Burns, aka Richard Berengarten. The book contains forty previously unreleased drawings created by Richards over a twenty-four-hour period within the pages of a first-edition copy of Dylan Thomas' Collected Poems. As stated in his introduction, Burns believed these drawings offered fresh material crucial for fully understanding and enjoying both the poet and the artist.

Ceri Richards (1903-1971) was a painter and printmaker. He found inspiration in Welsh culture and greatly admired Dylan Thomas’s poetry. Upon hearing of Thomas’s death, Richards was moved to create a series of drawings based on the poet's’ Collected Poems.

Dylan Thomas (1914-1953) was a poet and writer deemed one of the greatest Welsh poets of all time. His deeply emotional and lyrical poetry, as well as his tumultuous personal life, continue to resonate with readers. When discussing where he drew his inspiration, Thomas once said, “I should say I wanted to write poetry in the beginning because I had fallen in love with words. The first poems I knew were nursery rhymes, and before I could read them for myself, I had come to love the words of them. The words alone.”

-Melissa, Special Collections Graduate Intern

#drawings to poems by dylan thomas#dylan thomas#ceri richards#richard burns#richard berengarten#enitharmon press#collected poems#poetry#art book#welsh poetry#welsh#welsh art#art and poetry

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blessed morning, you cascade roaring lightfalls in this room. How can pain make me afraid, dead already, in my tomb?

Poem by Tin Ujević, translated by Richard Berengarten and Daša Marić

0 notes

Text

The Wine Cup: Twenty-four drinking songs for Tao Yuanming by Richard Berengarten (Shearsman Chapbook)

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The Void, by Dr Leon Burnett

“Poets of all ages have grappled with the idea of the void both as a cosmic phenomenon (or anti-phenomenon) and, in concert with modern philosophers from Søren Kierkegaard to Albert Camus, as a manifestation of a dreadful inner emptiness. The mysterious, inexplicable quality of the void makes it a subject particularly amenable to myth, as does its range of metaphorical and symbolic meanings.

A feeling of metaphysical emptiness lurks in the background of every observation of the natural world and threatens to suppress all delight in the superficial spectacle. Demonstrative of this susceptibility is the state of mind evidenced in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s nineteenth-century Dejection Ode, in which the romantic poet acknowledged within himself “A Grief without a pang, void, dark, & drear”, while “gazing on the western Sky”: “And still I gaze – & with how blank an eye!”.[1]

Similarly, but with a shift in key to a modernist sensibility, Wallace Stevens wrote in the twentieth century of the “Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is”, which the solitary man in the snow beholds. Readers of his poetry have debated at length the meaning of the closing line of “The Snow Man”, but they have devoted less attention to the assertion preceding it that the man listening to the wind is “nothing himself”.[2]

The prominence——and provenance——of this discordance may ultimately be traced back to the narratives and imagery in myths around the world that engage with origins. The void is the nihil out of which existence and being emerge and often ultimately return. This nihil is quite distinct from any imagined otherworld that accommodates in one form or another, comfortably or uncomfortably, all those who have departed in death.

There is a cosmic void and there is a personal void, the former usually situated before the creation of the cosmos and the latter after the extinction of the individual, whose transitory status on this earth is encapsulated in the designation mortal (from Latin mortalis, “subject to death”).

The cosmic void is encountered in Greek and Norse mythology. Hesiod’s Theogony refers to chaos [Χάος], a chasm but, in the way of the Ancient Greeks, also a goddess, and “Völuspá” in the Poetic Edda to a “yawning gap”: “Earth had not been, | nor heaven above,/ But a yawning gap, | and grass nowhere” [gap var ginnunga, en gras hvergi].[3] It was in the Gunningagap that the frost giant Ymir took shape. From the various parts of his body the earth and the sky came into being.

In the opening verses of the King James Version of the Bible, when “God created the heaven and the earth”, “the earth was without form, and void”. Mary Phil Korsak in her translation of Genesis, has “the earth was tohu-bohu/ darkness on the face of the deep”.[4] Tohu-bohu is normally understood as meaning “formless” and “void”. The same words occur in Isaiah 34:11, where the KJV renders them as “confusion” and “emptiness”.

These accounts of a cosmic void may all be regarded as interstitial, situated in-between earth and sky, in a non-physical gap in the fabric of the universe at a time before time. In this they show an affinity with fundamental concepts in the creation myths of Ancient Egypt. The Ogdoad of Hermopolis has eight divinities to represent the watery void, whereas Theban theology confines itself to one originary god. In the Old Kingdom record, he was Amun, the hidden one, who lived a mythical “negative existence” (Nun) before the creative principle led to the appearance of Shu (male, dryness) and Tefnut (female, moisture), who begat Geb (earth) and Nut (sky).[5]

The idea of nothingness is central to Taoism. The Tao Te Ching refers to the Tao as “Something formless, complete in itself/ There before Heaven and Earth”.[6] Richard Berengarten’s twenty-first-century, poetic homage to the I Ching states that “Endless beginingless/ heaven holds everything/ including astronomical// creation and demise/ of universes into and out/ of nothing”.[7] For him, “This constant flow//between notness/ and isness becomes and is/ all ways key”.[8]

Etymologically, void is related to vacancy, vanity, vastness and waste. All these words share a common Indo-European root and point to a recognition of the indeterminacy and lack of substance that is implicit in the poetic and mythological explorations of the measureless gap anterior to cosmological formation, marked by an absence of time and space, as well as the personal dimension of the nature of the “undiscover’d country, from whose bourn/ No traveller returns”.[9]

In the beginning was the void or, rather, before the beginning was the void. The beginning marks the advent of the word, of the god, of time and space – all abstractions designed to fill the void, as, indeed, mythological accounts of the void are. The various myths of creation ex nihilo propose two processes to account for the transition from void to plenitude: appearance and metamorphosis. The necessary condition for the existence of the material world arises from the appearance of a god or a divine object leading to some kind of transformation before the world can be populated.

The rest is story.”

0 notes

Text

Richard Berengarten: Volta

(Esti séta)

...most hogy leszáll az alkony... (Seferis)

Királyi Nap, rózsaszín arcú, a nap fenséges érme, megérintesz és bőröm szemgolyóvá változik, gerincem optikus ideggé és testem remeg félig kábultan az aranyözöntől, amit vakítón erre a városra és tengerre öntesz. Régen házak és utcák álltak itt - és tudom hogy most is állnak - egy más városnak részei, nem ezé, amit teljesen átformáltál erőddel.

Sétálunk hát a parton. Az éjjeli halászok már készítik csónakjaikat, motoruk berreg, hátul olajlámpások égnek, s az egész város kijött a sétatérre, szeretők kart karba öltve és mind a hetyke ifjak, anyák-apák, sok fagylaltozó gyerek, öregek nézik mindezt kirakott asztaloknál, s mint kezes állatok közelednek az alkonyi dombok.

Esti ég édes fénye hull a dombokra és az öbölre, karomhoz ér karod most, szinte véletlenül, mintha ez a mellettem járó fiatalasszony érintene, aki ringatva nehéz csípőjét, tipegve lép, fekete haja kontyba fogva, kényes nyaka és vállai sötétbarnák a naptól, mosolyog olajszín szemével. Reszkető fény, mint bort vagy zenét, úgy iszlak, ahogy e nőnek ősei ittak téged évszázadokkal ezelőtt.

Áttetsző város, a nő neve Elefthería, és bár sebhelyeid csak szürke pontok az ő szemében, mégis, ilyenkor, mikor a fény, s a fényhajlatok versként vagy dalként gyöngéden játszanak arcán, övé az ősi jog, hogy sétáljon itt a parton, fényeid eszközeként, s egyszersmind őreként, mély szembogarának kútjába gyűjtve őket, s övé - a drága szabadság - a jog, hogy rajtad táncosnőként taposson.

Estém-kedvesem, s te, több ezer éves fényem, tiszta hangon dalolsz, s elbűvölsz, mint e nő itt, hogyan bírnám ki, hogy ne imádjam bájadat, amit e városra s lakóira vetsz, ezt a formát, ami megmintáz mindent, amit érint, az egész világot? Rabszolgád lettem, ha már polgárod nem lehetek. És roppant szomjúsággal irántad, örömest tölteném be minden pórusom sugaraddal, a szabadság drága ízével.

Fordította Gömöri György

1 note

·

View note