#restuccia

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#fashion#fashion photography#fashion photoshoot#photography#photo#model#editorial#fashion magazine#naomi luise restuccia

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Dirección de “Las Raras Tuercas” de Pedro Restuccia

0 notes

Link

Los arreglos de la primera mitad de este video, están prestados e inspirados en el enganchado “A Seguir Bailando” de 1985 por el grupo Repique (Jaime Roos, Rolando Fleitas, Alberto Magnone, Andrés Recagno, Carlos “Boca” Ferreira, Gustavo Etchenique).

0 notes

Text

l'arte irregolare @ rai radio techetè: dal 30 gennaio al 3 febbraio

A Rai Radio Techetè, dal 30 gennaio al 3 febbraio Speciale sull’Arte Irregolare, a cura di Francesca Vitale, con materiali d’archivio, molto interessanti (le prime due puntate con interventi in RadioRai di Bianca Tosatti, storica e critica d’arte, massima esperta di arte irregolare, termine da lei coniato, in sostituzione di art brut). Ci sarà poi Cesare Zavattini che presenta ed intervista…

View On WordPress

#Alda Merini#art#art brut#arte#arte irregolare#Associazione Ultrablu#Bianca Tosatti#Cesare Zavattini#Francesca Vitale#Gianpaolo Mastropasqua#materiali d&039;archivio#Paolo Restuccia#pittori#radio#Radio Techetè#RadioRai#Rai#Rai Radio Techetè#Renzo Restuccia#speciale#Techetè#Virgilio Mollicone

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Bucharest, Romania by Alex Restuccia

204 notes

·

View notes

Photo

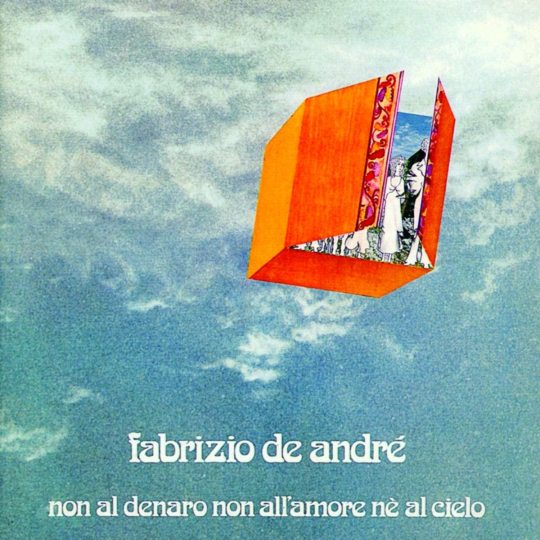

Storia Di Musica #264 - Fabrizio De André - Non Al Denaro Non All’Amore Nè Al Cielo, 1971

La piccola scelta di dischi ispirati a grandi romanzi non poteva che finire con questo disco. Senza dubbio è forse il primo che viene a mente riguardo al tema di un disco italiano che ha la caratteristica appena citata, e rimane uno degli episodi più significati della carriera, straordinaria, del suo autore. Fabrizio De André aveva appena pubblicato un disco che, in teoria, poteva benissimo rientrare nel tema principale di Febbraio: La Buona Novella (1970) infatti era un concept, tipologia molto cara all’autore genovese, che si ispirava ai Vangeli Apocrifi. Il Gesù di De André è profondamente umano, in una Palestina antica che in molti passaggi rimanda ai riflessi dell’Italia degli anni ‘70, in una sorta di porta incantata di quotidianità. Allora lo aiutarono Roberto Danè, produttore, paroliere, arrangiatore che proprio in quegli anni fondava la Produttori Associati (che pubblica il disco) e gli arrangiamenti di Giampiero Reverberi. Album toccante, ha una delle mie canzoni preferite di De André, il Testamento Di Tito. Proprio questa canzone fu registrata dal cantante Michele, nome d’arte di Gianfranco Michele Maisano, come lato b di Susan Dei Marinai, scritta dallo stesso De André nei cui titoli non appare, sostituito dal grande Sergio Bardotti. Il progetto iniziale di un disco ispirato ad uno dei libri più amati da De André doveva essere infatti un progetto curato dallo stesso trio De André, Darè e Reverberi per il cantante Michele, ma dissidi interni ruppero l’accordo, e Reverberi se ne va. A questo punto, De André riprende l’Antologia di Spoon River di Edgar Lee Masters, il libro in questione, e ne inizia a ragionare con la sua amica Fernanda Pivano, colei che, su suggerimento di Cesare Pavese, per prima portò in Italia e tradusse questo viaggio sentimentale e particolare che Lee Masters fa dell’America di provincia, ancora più ricca di contraddizioni e storie marginali. Per chi non lo ricordasse, l’Antologia è una raccolta di poesie-epitaffio della vita dei residenti dell'immaginario paesino di Spoon River sepolti nel cimitero locale, pubblicato tra 1914 e il 1915 sul Reedy's Mirror di Saint Louis, che la Pivano tradusse e che Einaudi pubblicò nel 1943 (prima edizione parziale) e nel 1945 (tutti i 212 epitaffi dei personaggi). De André collabora con un suo amico paroliere, Giuseppe Bentivoglio, con cui scrisse Ballata Degli Impiccati da Tutti Morimmo A Stento del 1968, per i testi e sceglie agli arrangiamenti un fresco diplomato del conservatorio, Nicola Piovani, al suo primo impiego importante di una carriera che lo porterà fino all’Oscar. Ad aiutarli una squadra di musicisti grandiosa: il violista Dino Asciolla, Edda Dell'Orso, soprano, i chitarristi Silvano Chimenti e Bruno Battisti D'Amario, questi tre ultimi storici collaborato di Ennio Morricone, il bassista Maurizio Majorana, membro dei Marc 4, il violoncellista classico d'origine russa Massimo Amfiteatrof, il batterista Enzo Restuccia, il maestro beneventano Italo Cammarota e il polistrumentista Vittorio De Scalzi, membro fondatore dei New Trolls. De André compone 9 brani, partendo come Lee Masters da La Collina, il luogo dove sorge il cimitero dove riposano i defunti di Spoon Rivers. 7 brani sono divisi in due grandi categorie: uomini morti d’invidia, ovvero Un Matto, Un Giudice, Un Blasfemo, Un Malato Di Cuore e uomini di scienza, con le sue contraddizioni etiche, ovvero Un Medico, Un Chimico, Un Ottico. Rimane poi Il Suonatore Jones, l’unico che rimane con lo stesso titolo del libro, che chiude il disco, con De André che però gli “toglie” il violino e lo fa suonatore di flauto. Straordinario è il lavoro di rifacimento e di ricreazioni nei testi: per esempio ne Un Giudice, ispirato a Selah Lively, deriso per la sua statura, in Masters è 5 piedi e 2 pollici (=157 cm circa) e nel testo di De André diviene così: Cosa vuol dire avere\Un metro e mezzo di statura\Ve lo rivelan gli occhi\E le battute della gente. I personaggi dell’invidia sono il giudice che ha trovato nella vendetta la sua alternativa alla derisione di essere basso, il matto che è stato spinto dall'invidia a “imparare la Treccani a memoria” (anche qui splendido gioco di trasposizione, in Lee Masters è l'Enciclopedia Britannica), il malato di cuore che riesce a vincere l'invidia attraverso l'amore, nonostante muoia appena porge le sue labbra su quelle della ragazza di cui è innamorato, Un Blasfemo invece è la canzone più politica, essendo uno strale contro chi “non Dio, ma qualcuno che per noi l'ha inventato / ci costringe a sognare in un giardino incantato”. Degli uomini di scienza, un medico è costretto dalla sua benevolenza, cioè curare i malati gratis, a vendere pozioni “miracolose” essendo caduto in miseria, un chimico è invece una storia di disillusione sull’amore, di un uomo che non capisce le unioni imperfette degli uomini rispetto a quelle perfette delle sostanze chimiche, un ottico invece, che vorrebbe regalare ai clienti un paio di occhiali magici per vedere davvero la realtà, è l’unico che probabilmente non è morto, dato che parla al presente (unicità che è presente anche in Lee Masters). Chiude il disco Il Suonatore Jones, inno alla libertà, di chi non ha voluto chiudere la sua libertà lavorando nei campi ma “Finii con i campi alle ortiche\Finii con un flauto spezzato\E un ridere rauco\E ricordi tanti\E nemmeno un rimpianto”. Oltre la qualità immensa del lavoro testuale è la musica che stupisce: gli arrangiamenti orchestrali, gli sviluppi tematici (come nel caso del motivo principale dell’iniziale La Collina, in continua trasformazione), la sovrapposizione di parti in forma di suite (un Ottico, con evidenti echi progressive ad un certo punto), l’uso di strumenti classici come clavicembali e violini. Sulla copertina della prima edizione, quella che ho pubblicato anche io, c’è un evidente errore grafico, con l’errata accentazione di "né". L’errore fu aggiustato nelle edizioni successive, e nel disco era presenta una lunghissima e delicata intervista di Fernanda Pivano a De André sulla genesi di questo disco e sul libro di Edgar Lee Masters, e alcuni racconti dello scrittore americano erano inseriti all’interno della confezione. Disco memorabile, da riscoprire e che formerà con il successivo, l’amatissimo e criticatissimo Storia Di un Impiegato uscito appena un anno più tardi (ad inizio del 1973) una trilogia lucidissima e potentissima sull’Italia di inizio anni ‘70.

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

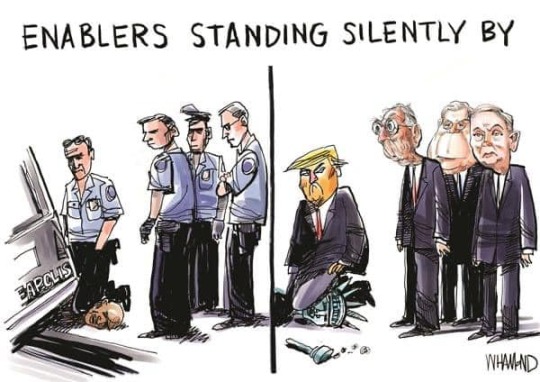

enablers standing by

* * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

March 8, 2023

Heather Cox Richardson

Andrew Restuccia, Richard Rubin, and Stephanie Armour of the Wall Street Journal today published a preview of President Joe Biden’s budget, due to be released tomorrow. Their article’s beginning sent an important message. Biden’s budget plan, they wrote, will “save hundreds of billions of dollars by seeking to lower drug prices, raising some business taxes, cracking down on fraud and cutting spending he sees as wasteful, according to White House officials.” Those officials said that, over the next ten years, the plan would cut deficits by close to $3 trillion. Reflecting the needs of Ukraine to fight off the 2022 Russian invasion, as well as tensions with China, Biden will call for a larger defense budget. As he outlined yesterday, part of the budget plan will fund the Medicare trust fund for at least another 25 years, in part by increasing tax rates on people earning more than $400,000 a year. “That is not going to happen. Obviously he knows that,” Senator Mitt Romney (R-UT) told the Wall Street Journal reporters. “Republicans are not going to sign up for raising taxes.” Without a budget plan of their own to offer, House Republicans appear to be trying to steal the president’s thunder. They told Tony Romm of the Washington Post that they are getting ready for the House Ways and Means Committee to begin consideration tomorrow of a bill to prioritize the national debt in preparation for a national default. House Republicans continue to insist they will not vote to raise the debt ceiling to pay for expenses already incurred—many of them under Trump—thus forcing the U.S. into default for the first time in our history. They are suggesting they could rank the debts in order of importance, but as Brian Riedl, an economist at the Manhattan Institute, told Romm, the computer systems were written with the assumption the country would, in fact, pay its debts, and they do not have programs that would let them prioritize payments to one group or another. In any case, the White House has refused to negotiate over paying the nation’s bills. It remains eager to discuss the budget with Republicans and to negotiate over it—which is how the process is supposed to proceed—but insists the Republicans cannot hold the nation hostage by threatening a default that would spark an international financial crisis and destroy the American economy. Indeed, the willingness of the Republican Party to default on the country’s debt shows how thoroughly radicalized it has become. Even the Republican leaders who do not embrace the racism, sexism, religiosity, nihilism, and authoritarianism of the hard-core MAGA Republicans appear to believe they cannot win an election without the votes of those people. And so the extremists now own the party. They continue to support former president Trump, who at the Conservative Political Action Conference last weekend promised “those who have been wronged and betrayed: I am your retribution.” The party is now one of grievance and revenge, feeding on their false conviction that Trump won the 2020 election. The Fox News Channel was key in feeding that Big Lie, of course, and filings from the Dominion Voting Systems defamation lawsuit against the Fox News Network have revealed that Fox executives and hosts alike knew it was a lie. They continued to spread it because they didn’t want to lose their base. On Monday, Fox News Channel personality Tucker Carlson, who has found himself badly exposed by the Dominion filings, threw himself back into the Trump camp. He showed a false version of the January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, suggesting it was a mostly peaceful tourist visit rather than the deadly riot it actually was. Carlson’s false narrative was possible because House speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) gave Carlson exclusive access to more than 40,000 hours of video taken in the Capitol on that fateful January 6, illustrating that there is no daylight between the lies of the Fox News Channel and the House Republican leadership. Outrage over that transaction has sparked a backlash. Former officer of the Metropolitan Police Michael Fanone, who was badly injured defending the Capitol on January 6, published an op-ed at CNN saying he knew for certain that Carlson’s version of that day was a lie. “I was there. I saw it. I lived it,” Fanone wrote. “I fought alongside my brother and sister officers to defend the Capitol. We have the scars and injuries to prove it.” Former representative Liz Cheney (R-WY) tweeted that if the House Republicans want new January 6th hearings, “bring it on. Let’s replay every witness & all the evidence from last year. But this time, those members who sought pardons and/or hid from subpoenas should sit on the dais so they can be confronted on live TV with the unassailable evidence.” Senate Republicans also spoke out against Carlson’s lies. Minority leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) aligned himself with Capitol Police Chief Tom Manger, who called Carlson’s piece “offensive.” McConnell said: “It was a mistake, in my view, for Fox News to depict this in a way that’s completely at variance with what our chief law enforcement official here at the Capitol thinks.” Democrats, along with the White House, also condemned Carlson’s video. White House spokesperson Andrew Bates said the White House supported the Capitol Police and lawmakers from both parties who condemned “this false depiction of the unprecedented, violent attack on our Constitution and the rule of law—which cost police officers their lives.” Bates went on: “We also agree with what Fox News’s own attorneys and executives have now repeatedly stressed in multiple courts of law: That Tucker Carlson is not credible.” But McCarthy says he does not regret giving Carlson access to the tapes, and Carlson indicated that anyone who objected to the false narrative he put forward on Monday had revealed themselves as being allied against the Republican base. Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) and House Oversight Committee chair James Comer (R-KY) are organizing a visit for members of Congress to visit the jail where defendants charged with crimes relating to the January 6th riot are behind held. In the past, Greene called those defendants “political prisoners of war.” Today the Office of the Director of National Intelligence released the 2023 Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community. It warned that transnational “Racially or Ethnically Motivated Violent Extremists” (RMVEs) continue to pose a threat more lethal to U.S. persons and interests than do Islamist terrorists. RMVEs are “largely a decentralized movement of adherents to an ideology that espouses the use of violence to advance white supremacy, neo-Nazism, and other exclusionary cultural-nationalist beliefs. These actors increasingly seek to sow social divisions, support fascist-style governments, and attack government institutions,” the report said. They “capitalize on societal and political hyperpolarization to…mainstream their narratives and conspiracy theories into the public discourse.” They are recruiting “military members” to “help them organize cells for attacks against minorities or institutions that oppose their ideology.” Finally, John Bresnahan of Punchbowl News reported that 81-year-old Senator Mitch McConnell fell at an event at the Waldorf Astoria in Washington, D.C., tonight and has been hospitalized.

—

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#Political cartoon#budget#finance#Letters From An American#Heather Cox Richardson#Director of National Intelligence#treat to democracy#House Oversight Committee#anti-democratic#coup plotters#disinformation#FAUX news

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Power of Prudence

Prudence is difficult to pin down to a single definition due to its translations shifting over time. Generally, prudence is the wisdom to make decisions that are practical and will lead to the best outcome. It is the use of reason to weigh the consequences of actions based on prior knowledge. Education and experiences are important in cultivating prudence, as more intelligence allows for deeper thought about decisions and smarter choices.

Exemplars of this virtue are cautious and realistic. They weigh choices and use practical sense and knowledge. Ham Sok Hon is an example of prudence. As explained on the ForwardIntoMemory webpage, "Ham’s education at Osan, and particularly the lessons provided by mentor Yu Young Mo (유영모), provided Ham with important ideas which were foundational to his distinct pacifist, cosmopolitan and egalitarian perspective." Ham combined his passions and philosophy with a strong education in order to make decisions regarding his Korean activism.

Prudence helps people satisfy most of their core needs. Intention, thought, and knowledge are important ingredients in achieving most goals. If we look, for example, at Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, every need is achieved through a series of decisions. Safety and basic needs require an understanding of what will fulfill the needs and how to achieve them. Each further level requires more knowledge and experiences to be carried out.

In the modern day, prudence exists mostly in two spheres. Financial prudence is considered important in running a business and staying afloat under capitalism. Also, prudence is a strong principle in Catholicism. Catholic people consider prudence as "practical wisdom that empowers one to be good and to act well in daily affairs, both ordinary and extraordinary." I would "enter the forest" of prudence with its inclusion in religion, as many people were extremely devoted to their faith and took on the virtue in every aspect of their lives. Many following accounts of prudence can be traced back to religion.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://www.wsj.com/politics/policy/men-women-vote-republican-democrat-election-7f5f726c

America’s New Political War Pits Young Men Against Young Women

A majority of men under 30 support former President Trump and Republican control of Congress, a sharp reversal from the 2020 race; young women strongly favor Democrats

Collin Mertz and Lauren Starrett

Collin Mertz and Lauren Starrett LEWIS ABLEIDINGER FOR WSJ, MADDIE MCGARVEY FOR WSJ

By Aaron ZitnerFollow

and Andrew Restuccia

0 notes

Video

youtube

📚 “Una Donna, Un Libro” con Mirella Restuccia 📚moderatore Roberto Romiti

0 notes

Text

Sara Marcoccia, "Le Giraffe in giardino" a Spazio5 Mercoledì 17 aprile 2024 alle 18.00 Sar... #agr3 #legiraffeingiardino #lucianotirinnanzi #paolorestuccia #saramarcoccia #spazio5 https://agrpress.it/sara-marcoccia-le-giraffe-in-giardino-a-spazio5/?feed_id=4376&_unique_id=660f29cd0220b

0 notes

Text

Andrew Restuccia and Aaron Zitner at WSJ:

WASHINGTON—As he campaigns to retake the White House, Donald Trump has increasingly tossed aside the principles of limited government and local control that have defined the Republican Party for decades.

The former president is laying plans to wield his executive authority to influence school curricula, prevent doctors from providing medical interventions for young transgender people and pressure police departments to adopt more severe anticrime policies. All are areas where state or local officials have traditionally taken the lead. He has said he would establish a government-backed anti-“woke” university, create a national credentialing body to certify teachers “who embrace patriotic values” and erect “freedom cities” on federal land. He has pledged to marshal the power of the government to investigate and punish his critics. It is a governing platform barely recognizable to prior generations of Republican politicians, who campaigned against one-size-fits-all federal dictates and argued that state legislators, mayors and town halls were best positioned to oversee their communities. While many of his proposals would be difficult to achieve, the second-term agenda outlined by Trump could require waves of new federal intervention, even as he calls for firing government workers, neutering the “deep state” and cutting regulations. “If Trump wins, the days of small government conservatism may be over,” said Lanhee Chen, a fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution who served as the policy director of Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign.

For Trump, a second presidential term would mark the culmination of a yearslong campaign to reshape the party in his image, moving away from the core ideals espoused for decades by Ronald Reagan, Barry Goldwater, William F. Buckley and other idols of the conservative movement. Instead, Trump has rallied his millions of supporters in part by tapping into the cultural and social grievances that animate the conservative base. The rapid shift in the priorities of the party has led to something of an existential crisis for longtime Republican officials. They have privately said the GOP of today is unrecognizable from even a decade ago, when many Republicans were campaigning on leaner government, balanced budgets, entitlement reform and free trade. As president, Trump presided over four straight years of rising annual deficits, signing bipartisan budget agreements that boosted federal spending. He launched a trade war with China. And earlier this year, he warned his party not to “cut a single penny from Medicare or Social Security.”

[...] Even some of Trump’s allies have privately expressed doubts about several of his proposals. Several former Trump administration officials said they were skeptical of the feasibility of the former president’s plan, announced in a video message on his social-media platform last month, to establish an “American Academy” funded by “taxing, fining and suing” what he calls “excessively large” private university endowments. Trump pitched the government-backed free online school as an alternative to the current higher education system. “There will be no wokeness or jihadism allowed,” Trump said. Roberts, Heritage’s president, said he “loves” the university plan but opposes Trump’s proposal for federal certification of teachers. “I hate it. It’s a terrible idea,” he said. Heritage wants to end teacher certification altogether. As with many of his second-term proposals, Trump has offered little detail about the plan other than to say he would create a “credentialing body to certify teachers who embrace patriotic values and support the American Way of Life.”

Using government to counter liberalism

Trump’s platform is an expansive example of the reorientation among some within the GOP more broadly in favor of a more active federal government. In Congress, some Republicans have pushed for such federal measures as caps on credit-card interest rates, social-media regulations and worker protections in contracts that fit awkwardly with the party’s business-oriented impulses. Like Trump, several other GOP presidential candidates say that an aggressive use of federal authority is needed to push back against a liberal social agenda that they say has taken hold in schools, academia, the media and corporate boardrooms. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has argued that “old-guard corporate Republicanism isn’t up to the task.” The idea is an extension of one advanced in an influential 2016 essay, “The Flight 93 Election,” by Michael Anton, who went on to be a Trump national security aide. He said that the U.S. was “headed off a cliff” because of liberal dominance of institutions, and traditional conservatives weren’t prepared for the seriousness of the fight.

[...]

More government means more bureaucracy

Implementing many of his other proposals could require building additional layers of government bureaucracy, some of which could overrule or duplicate existing state and local efforts. Credentialing teachers on the federal level could mean creating a new government body that would complicate existing state certification efforts. Setting up a new government-backed university could require a labyrinthine system of government contracts to hire instructors and staff. Trump’s proposals to direct the government to investigate everything from MSNBC to hospitals could require hiring additional lawyers and other employees to carry out the probes. Other vaguely defined ideas—like Trump’s proposals to establish a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to declassify and publish documents on “Deep State spying” and an independent auditing system to monitor U.S. intelligence agencies—would also likely require new government programs. Washington policy-making veterans said many of Trump’s plans are unlikely to come to fruition even if he wins a second term, citing logistical and financial hurdles, potential opposition from Congress and likely court challenges.

Donald Trump's 2nd term agenda will be chock-full of big government fascism, jettisoning the historical conservative principles of local control and small government.

Some of those items: a national teacher credentialling body, a nationwide ban on gender-affirming care for minors (and a de facto all-age ban on GAC), creation of a right-wing indoctrination university, and creating "freedom cities."

#Donald Trump#2024 Presidential Election#2024 Elections#Trumpism#Trump Administration#Kevin Roberts#Brooke Rollins#Michael Anton#The American Academy#Trump Administration II

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alumni Stories: Melissa Restuccia

Once again, Where Creativity Works was fortunate to interview Melissa Restuccia, an Art Education Alumni from the class of 1993. Melissa has a wonderful story, and her work is beautiful. Read this blog to learn more about her, and her artwork. #Alumni

This week we are pleased to share our Alumni Story interview with another Marywood Art alumna, Melissa Restuccia. She is a 1993 Art Education graduate and in her story she tells us about her favorite parts of studying at Marywood and how Marywood helps her in her current careers. Name: Melissa Restuccia (Crane, Maiden Name) Graduation Year & Degree: 1993 BA Art Education Major: Art…

View On WordPress

#alumni#Art#Art Education#Art Teacher#breast cancer#calling#ceramics#Class of 1993#craftsmanship#educator#family#Fibers#freelance#Gallery#Gray Cat Restoration#Illustration#inspiration#jewelry#Marywood Art#Marywood Art Department#Marywood University#Marywood University Art Department#painter#Painting#Photography#Retirement#Students#Studio#technique#weaving

0 notes

Text

Restuccia: " Anche lo sport per la diplomazia culturale, un esempio gli Europei di calcio 2024"

Il direttore dell’Istituto italiano di cultura di Stoccarda a Firenze; “Puo’ catturare un pubblico piu’ giovane”source

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

i prossimi speciali di rai radio techetè

i prossimi speciali di rai radio techetè

a cura di Francesca Vitale dal 16 al 18 gennaio Alice nel paese delle meraviglie dal 23 al 25 gennaio Aldo Braibanti (con un intervento di Agostino Raff) dal 30 gennaio al 3 febbraio Arte irregolare (materiale d’archivio + interventi di: Gianpaolo Mastropasqua (Arte e follia), Virgilio Mollicone (Associazione Ultrablu) e Paolo Restuccia (Ritratto di Renzo Restuccia)

View On WordPress

#Agostino Raff#Aldo Braibanti#Alice nel paese delle meraviglie#art brut#arte irregolare#Francesca Vitale#Gianpaolo Mastropasqua#Lewis Carroll#Rai Radio Techetè#Renzo Restuccia#speciali Radio Techetè#Virgilio Mollicone

0 notes

Text

Spiniform Phase-Encoded Metagratings Entangling Arbitrary Rational-order Orbital Angular Momentum - Kun Huang, Hong Liu, Sara Restuccia, Muhammad Qasim Mehmood, Shengtao Mei, Daniel Giovannini, Aaron Danner, Miles John Padgett, J. H. Teng, Cheng-Wei Qiu

1 note

·

View note