#remember when 17 were killed and 17 others injured in Parkland and it was an outrage?

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I hate my country so much sometimes. And right now isn't one of those times. Because all i can muster is a little bit of frustration. And that's bad. It's bad I'm so numb to this

#murky mumbles#venting#they haven't even caught the shooter yet. my brother left the building less then half an hour before it started.#a friend of mine's cousin was shot four times.#my best friend lives there#a parent my neighbors knew (my neighbors who's kids I help nanny. I'm super close to that whole family) was shot#I just. want to know if any kids or parents that my kids knew were killed or injured or just. were there#because god knows how fucking terrified the brother would be if he knew anyone there and I want to be prepared#but info is lacking and I can't get into proper contact with everyone right now#I'm debating just going over and chilling with the kids today because school is canceled while the shooter is still out and about#but i'd need to take a shower first and i don't know if i have the energy for both things today#remember when 17 were killed and 17 others injured in Parkland and it was an outrage?#and now just as many are dead with more possible casualties#and dozens are injured#and the shooter is STILL OUT THERE#and we are just gonna move on in a couple days#it's so bullshit. and I can't even muster up the energy to be properly upset

1 note

·

View note

Text

Parkland students experienced their second deadly school shooting in 7 years

Click here

By Taylor Galgano, CNN

Five-minute read Published 1:00 AM EDT, Sat April 19, 2025

A vigil is held near the Florida State University student center on Thursday, following the shooting.

J. Miguel Getty Images/Rodriguez Carrillo CNN

During the Thursday shooting at Florida State University, Ilana Banner recalled thinking, "I kind of knew the drill already," as she sought refuge in the student union. Seven years ago, Banner was an eighth grader at the middle school adjacent to Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School during the shooting that killed 17 people in Parkland, Florida.

I’ve been through this before. It was a similar situation,” Banner, 21, told CNN.

Now a senior at FSU, Banner was attending a bowling class on the ground floor of the student union Thursday when a shooter opened fire near the building, killing two people and injuring six others before he was shot and taken into custody by police.

It marked the sixth mass shooting in Florida and the 81st mass shooting in the United States in 2025, according to the Gun Violence Archive.

The bowling area has big glass doors and windows that face an open area where students can grab food or study. Through the windows, Banner started to see students sprinting to the bathrooms and hallways and leaving behind their belongings.

Though Banner couldn’t hear any gunshots over the loud music playing in the bowling alley, she instantly thought students were running from someone with a gun.

“I didn’t know why everyone else would be running and they were leaving all their belongings behind and definitely knew there was an emergency,” she said.

She and a friend immediately let her bowling instructor know that something was wrong. Banner claims that this instructor is Stephanie Horowitz, who is also a Parkland shooting survivor. Horowitz was a freshman at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School during the 2018 mass shooting on Valentine’s Day.

In an interview with CBS, graduate student Horowitz stated, "I had a feeling it was an active shooter situation before I even heard." “We were lucky that some of my students looked out of the glass doors and saw everybody running.”

On X, the father of Jaime Guttenberg, a 14-year-old who was killed in the Parkland shooting, Fred Guttenberg, wrote, "America is broken." My daughter Jaime was murdered in the Parkland school shooting. FSU was attended by many of her friends who were fortunate enough to survive the shooting. Amazingly, some of them were in the student union today and just part of their second school shooting. Josh Gallagher, who said he also survived the 2018 shooting, was in the FSU Law Library during Thursday’s shooting.

“After living through the MSD shooting in 2018, I never thought it would hit close to home again,” he posted on social media.

Memories of Parkland shooting

Horowitz led Banner and about 30 to 40 others to hide in the back office of the bowling alley, according to Banner. Some students also took shelter in a backroom where people play billiards.

It was at that moment that Banner started receiving texts from the FSU emergency line while an overhead alarm sounded. She was correct in her suspicions of a shooting. She started texting her dad every few minutes. She remembers thinking: was the shooter in the building? Was he outdoors? What floor was he on?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

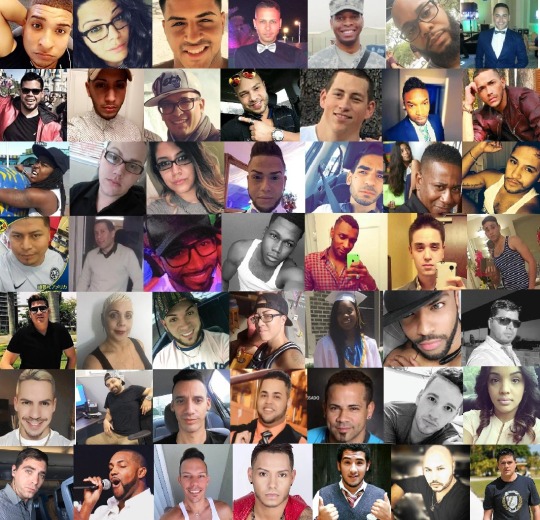

Chapter Twelve : ORLANDO NIGHTCLUB SHOOTING

June 11, 2016. Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, was hosting its weekly Saturday event “Latin Night”. Around 2:00am on June 12, last call for drinks were announced to about 320 people inside the club. At the same time, a mad man, who-shall-not-be-named as he doesn’t deserve to be talked about as a person ever again, arrived by van armed with a SIG Sauer MCX semi-automatic rifle and a 9mm Glock 17 semi-automatic pistol. At 2:02am, he bypassed an off-duty Orlando police officer called Adam Gruler who tried to engage and stop him. He went into the building and began shooting patrons. Dozens were killed in the 2 minutes between 2:02am and 2:04am when Gruler, after calling for assistance, received additional aid from officers arriving at the club. The shooter retreated farther into the nightclub and kept on killing. At first, some patrons thought the gunshots were firecrackers or part of the music. Some of the survivors described afterwards a scene of panic and confusion caused by the loud music and darkness of the nightclub scene. Most people took refuge in bathrooms, waiting for death. One of them shielded herself with bodies. Some escaped by crawling out the patio exit near the bar. A bartender took cover beneath the glass bar. A recently discharged marine veteran working one of the nightclub bouncer immediately recognized the sounds of gunfire, jumped over a locked door behind which dozens of people were already hidden and paralyzed by fear. He then opened a latched door behind them, allowing approximately 70 people to escape. As the gunman started shooting in the main room, police officers entered the facility and a shootout was engaged. The police reported that many people escaped or were rescued during this early exchange of gunfire, as a few police officers were running in and out of the building pulling out victims. According to a man trapped inside a bathroom with fifteen other people, the shooter shot multiple times into the closed bathroom door, killing at least two and wounding several others. One of the people trapped in the bathroom with the shooter afterwards said that he burst into the bathroom, went to the stall next to the one he and a friend were hiding in and shot the people inside.

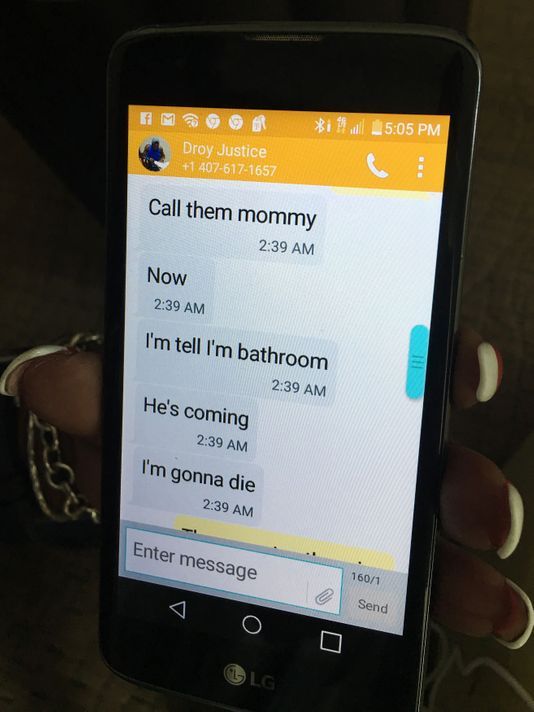

After the shootout, the gunman retreated to the women’s bathroom where he held hostages. Meanwhile, some of the people trapped sought to send text messages to friends and relatives, either to inform of the situation or to say good-bye.

Rescues of people trapped inside the nightclub commenced and continued throughout the hostage crisis. Because so many people were lying on the dance floor, one rescuing officer asked “if you’re alive, raise your hand”. People were pretending to be dead with bodies surrounding them in order to not get killed themselves. One of the survivors later said he felt something poking him while on the floor. He thinks it could have been the shooter checking to see if he was dead. By the beginning of the phone calls from the shooter to multiple sources, nearly all of the injured patrons from the club had been extracted from the building, except for those held hostages in the bathroom and a few in dressing rooms.

No shots were heard between the exchanging gunfire with the first responders and three hours later.

At 2:35 am while in the bathroom, the gunman placed a 911 call in which he pledged his allegiance to the Extremist Islamic State. At 2:48am, he talked to a crisis negotiation team for 9 minutes. He ordered the end of the bombing in Syria and Iraq and claimed to have explosives on him. During this time, more people escaped. Four people hidden in a dressing room took the exist from the north side of the building while the police helped eight people escape through an air-conditioner vent. At 4:29am, some survivors who escaped informed of the gunman’s plan to put explosive devices on four hostages in each corner of the club. An information that turned that to be a lie on the past of the gunman as no vests or devices were found afterwards. It prompted officials to mount a rescue operation. At 5:02am, the police blew a hole in the outer wall of the restroom, but missed the mark and ended up with a partially destructed wall in the hallway between the two bathroom. On that occasion, the rest of the survivors escaped through the hole. At 5:14 am, the gunman entered the hallway and engaged in a shootout with the police. At 5:15am, officers reported that the gunman was down. He was shot eight times and killed in a face out that involved 11 officers who fired a total of about 150 bullets. More than three hours after the first attack.

49 innocent people died that night. 53 were wounded during the attack, some critically. 38 were pronounced dead at the scene, and 11 more at local hospitals. Of the 38 victims to die at Pulse, 20 died on the stage area and dance floor, 9 in the nightclub’s northern bathroom, 4 in the southern bathroom, three on the stage, one at the front lobby and one out on a patio. At least 5 of those were killed during the hostage situation in the bathroom. As for the wounded, a least 76 surgeries were performed on the patients, with some discharged as far as September 6, nearly 3 months after the shooting occurred.

The attack became the deadliest mass shooting by a single shooter in United States History, bested a little over a year later by the Last Vegas shooting of 2017. It is still the deadliest attack on LGBT people in History in the U.S, surpassing the 1973 UpStairs Lounge Arson Attack (see the June 10th article Chapter Ten : Queer Community vs Violence).

Here is the complete list of the fallen brothers and sisters we’ve lost that night :

Stanley Almodovar III, 23

Amanda Alvear, 25

Oscar A. Aracena-Montero, 26

Rodolfo Ayala-Ayala, 33

Alejandro Barrios Martinez, 21

Martin Benitez Torres, 33

Antonio D. Brown, 30

Darryl R. Burt II, 29

Jonathan A. Camuy Vega, 24

Angel L. Candelario-Padro, 28

Simon A. Carrillo Fernandez, 31

Juan Chevez-Martinez, 25

Luis D. Conde, 39

Cory J. Connell, 21

Tevin E. Crosby, 25

Franky J. Dejesus Velazquez, 50

Deonka D. Drayton, 32

Mercedez M. Flores, 26

Peter O. Gonzalez-Cruz, 22

Juan R. Guerrero, 22

Paul T. Henry, 41

Frank Hernandez, 27

Miguel A. Honorato, 30

Javier Jorge-Reyes, 40

Jason B. Josaphat, 19

Eddie J. Justice, 30

Anthony L. Laureano Disla, 25

Christopher A. Leinonen, 32

Brenda L. Marquez McCool, 49

Jean C. Mendez Perez, 35

Akyra Monet Murray, 18

Kimberly Morris, 37

Jean C. Nieves Rodriguez, 27

Luis O. Ocasio-Capo, 20

Geraldo A. Ortiz-Jimenez, 25

Eric Ivan Ortiz-Rivera, 36

Joel Rayon Paniagua, 32

Enrique L. Rios Jr., 25

Juan P. Rivera Velazquez, 37

Yilmary Rodriguez Solivan, 24

Christopher J. Sanfeliz, 24

Xavier Emmanuel Serrano Rosado, 35

Gilberto Ramon Silva Menendez, 25

Edward Sotomayor Jr., 34

Shane E. Tomlinson, 33

Leroy Valentin Fernandez, 25

Luis S. Vielma, 22

Luis Daniel Wilson-Leon, 37

Jerald A. Wright, 31

Criticism was expressed over the decision the delay the breaching of the nightclub through the bathroom wall by over 3 hours, citing the lesson learned form other mass shooting that officers can minimize casualties only by entering a shooting location expeditiously, even if it means putting themselves at great risk. To that, the Police Department answered that the situation had changed from an active shooter in the club to an hostage situation and could not be handled the same way. Immediately after the shooting took take, many people went to donate blood at locate blood donation centers and bloodmobile. Although ironically, a controversial federal policy in the United States forbids men who had sex with men from donating blood, urging straight people to go instead. A victim’s assistance center was opened on June 15 to provide help to what turned out to be almost a thousand people. Furthermore, the two main hospitals that treated the victims, Orlando Regional Medical Center and Florida Hospital, announced that they will not be billing the survivors or pursuing reimbursement. Multiple fundraisers raised close to 32 million dollars to help victims and families in the months that followed.

The Pulse never opened its doors again. There were plans to sell the property to the City of Orlando and turn it into a memorial for the victims and survivors, though the city backed out after the price tag of 2,25 million dollars was asked. The owner then created the OnePulse Foundation and plans for a memorial site and museum are on the way, with an opening slated for 2020.

Without going into any specifics about the gunman’s personal life and motivations, it is imperative to point out that before his attack on Pulse, he was interrogated three times by the FBI due to relations with terrorist-affiliated individuals and organizations. He was twice under investigation (but no convincing evidence were found). He was on a no-fly list, meaning he wasn’t allowed on any airplanes. Nevertheless, the shooter was able to go into a gun store and LEGALLY buy a semi-automatic weapon. He went through a three-day background check and still went through the cracks. Then Las Vegas happened and they did nothing. Then Parkland happened and they did nothing.

As of June 11th, 2019, there’s been 149 mass shootings in the United States since January 1. For fuck’s sake! There’s been a mass shooting TODAY (Aurora, Colorado) with 4 people injured.

People were quick to point out that this was a terrorist attack trying to destroy the American way of life. Sure, it was. But let’s remember that first and foremost, this was a hate crime. This was an attack perpetuated on a minority group, on the basis of exterminated them, a few rounds of bullets at a time.

On a personal note, it broke my heart when I heard what happened in Orlando three years ago. I saw the news coverage and I broke down. One of the victims had the same name as me. I was a 25 year-old french boy living in Paris and I felt like I was about to die with the rest of my community. When you kill one of us because of who we are, we all bleed. Those 49 deaths, 53 wounded victims and almost 200 survivors were our brothers and sisters and mothers and fathers and friends. And I’m not just talking about the LGBTQI+ community. There were the brothers and sisters and mothers and fathers to US ALL.

Where are we, three years later ? Is that just another massacre ready to resurface each date of the tragedy’s anniversary and then forgotten for another year ? I’m no one. I can’t influence anything on anyone. BUT they’ve been living in me for the past three years, one way or another. The faces have been on my wall for three years. The names have been on my wall for the past three years. Their memories have not been forgotten by me for the past three years. The Time magazine cover asked the question : WHY DID THEY DIE ? They shouldn’t but they are. Let’s celebrate them by protecting each other more.

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://toldnews.com/world/parkland-anniversary-moment-of-silence-marks-one-year-since-school-shooting/

Parkland anniversary: Moment of silence marks one year since school shooting

Image copyright Getty Images

A US community devastated by a school shooting one year ago is marking the tragic anniversary with quiet mourning.

Seventeen people were shot and killed by an ex-student at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School (MSD) in Parkland, Florida on 14 February 2018.

Students and educators across the country are also marking the day with vigils, moments of silence, art projects and other demonstrations.

On Wednesday, the Florida governor called for a renewed investigation.

How is the event being marked?

Schools in Broward County – the southern Florida region where 14 students and three school staff members were killed – will operate on a regular schedule, but students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas will hold a “non-academic” day devoted to commemoration and healing.

Classes at MSD will end before 14:20 local time, the moment the shooting began a year ago.

“Although we mourn from the lives that we’ve lost through a horrific act of hate and anger, I believe that we must also celebrate the possibilities of what can be through love and support,” superintendent Robert Runcie. said outside the school on Thursday.

Schools across the state of Florida held a moment of silence at 10:17 local time, to honour the 17 people killed in the gun attack.

The city of Parkland is sponsoring a day of service at a park near the school and will hold a moment of silence, with a vigil to be held later in the evening.

Mental health professional and comfort dogs will be there to assist grieving students throughout the day.

How being a student gun control activist took its toll

WATCH: I was shot and now owe tens of thousands of dollars

Emma Gonzalez, a survivor who became a prominent student activist after the attack, said the gun control advocacy group March for Our Lives will remain silent through the weekend.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Media captionStudents around the world on US school shootings and their biggest fears

“Like so many others in our community, I’m going to spend that time giving my attention to friends and family, and remembering those we lost,” Ms Gonzalez wrote in a statement.

“The 14th is a hard day to look back on. But looking at the movement we’ve built – the movement you created and the things we’ve already accomplished together – is incredibly healing,” she wrote.

Image copyright Getty Images

‘I’ll always remember that morning’

Jimmy Tam, BBC News, Parkland, Florida

“I keep missing her,” sobs a male student, as he pulls away from an embrace. His friend was killed in the shooting. He says plans to visit her grave for the last time today; it’ll help him move on.

A noisy intersection outside the school has been transformed into a memorial garden for staff and students to remember and reflect.

Hundreds of flowers of all colours now accompany the “Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School” sign.

But not just flowers – there are painted pebbles and paving slabs with messages, a totem pole with all 17 victims’ names, and 17 angels that light up at night.

Staff and students, many in maroon “#MSDStrong” T-shirts, have been coming all day. So have parents, friends and other loved ones.

On occasion, Amazing Grace has played out of a speaker that’s been set up.

Victoria Gonzalez created the garden, named Project Grow Love, with her teacher Ronit Reoven. Victoria lost her boyfriend Joaquin in the shooting. Today she’s wearing a brooch with a photo of him.

She remembers her final morning with him last year, on Valentine’s Day: “We shared our gifts and we just felt unstoppable and he did always tell me that our love was bulletproof, believe it or not. I’ll always remember that morning.”

How else is the event being marked?

Elsewhere in the country schools are marking the anniversary with art projects or statements.

Boardman High School in Ohio will hold a “legacy lockdown” including an active-shooter drill, which organisers say is a way to help students feel safer and emergency officials to feel more appreciated.

The Buffalo Teachers Federation in New York have encouraged people to wear bright orange, as hunters do for safety, and hold a moment of silence.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Media caption“When people think of Parkland I want them to think about people standing up for something”

In a statement, President Donald Trump pledged that he will “not rest” until US schools are made safe.

“Today, as we hold in our hearts each of those lost a year ago in Parkland, let us declare together, as Americans, that we will not rest until our schools are secure and our communities are safe.”

Former President Barack Obama – who told BBC News in 2015 that it was “distressing” that the US has not passed national gun safety reform – tweeted his support to the March for Our Lives students on Thursday.

Skip Twitter post by @BarackObama

In the year since their friends were killed, the students of Parkland refused to settle for the way things are and marched, organized, and pushed for the way things should be – helping pass meaningful new gun violence laws in states across the country. I’m proud of all of them.

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) February 14, 2019

End of Twitter post by @BarackObama

What has changed in the past year?

According to the Giffords Law Center, an organisation advocating for more gun control, lawmakers in 26 states and Washington DC passed 67 new gun safety laws in 2018.

Four states raised the minimum age for firearm purchases, and seven states strengthened or expanded background checks for gun buyers.

More than half of all 50 states passed at least one gun control measure in 2018, according to the New York Times.

Efforts to prevent mass shootings and gun crime – which account for roughly 25,000 deaths in the US each year – have gained little traction on the national level, with partisan bickering blocking any congressional legislation.

But the federal government enacted Mr Trump’s ban on bump-stocks, a device that enables many rifles to fire at the rate of a machine gun.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Media captionWhy Parkland school shooting is different – the evidence

Bump stocks were used to kill 59 people in Las Vegas in 2017 – and injure more than 400 – but were not used by the shooter in Florida.

Democrats have made gun control efforts a priority since winning a majority in the House of Representatives in November, and earlier this week took their first action to address gun violence.

On Wednesday the House Judiciary committee approved a bill that would require gun buyers to undergo background checks in virtually every single gun sale.

The bill now moves to the full chamber, and must be passed by both the House and Senate.

More on US school shootings

2018 ‘worst year for US school shootings’

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Media captionHow much do US students fear school shootings?

0 notes

Text

Christchurch terror suspect was member of New Zealand gun club

Accused Christchurch shooter Brenton Tarrant is a member of a New Zealand gun club where he would fire AR-15 semi-automatic rifles, it has emerged.

Tarrant, 28, originally from Grafton, New South Wales, went to Bruce Rifle Club in Milton on New Zealand’s South Island – near where he had been living in Dunedin.

The club felt ‘betrayed’ after it heard Tarrant was the suspect behind the killing of at least 49 people yesterday.

Police allege that after opening fire inside the Al Noor Mosque, Tarrant drove to the Linwood Masjid Mosque across town and continued his rampage.

Brenton Tarrant, charged in relation to the Christchurch massacre, appears in the dock on murder charge in Christchurch District Court today

Accused Christchurch massacre gunman makes a white power gesture from behind a glass window, during a brief hearing in court

Tarrant described himself as an ‘ordinary, white man’, who was born into a working class, low income family of Scottish, Irish and English descent

Tarrant is a member of Bruce Rifle Club in Milton, near Dunedin, where Tarrant lived. Members of the range shoot during a practice

Bruce Rifle Club was where Tarrant would use a AR-15 semi-automatic rifle. It caters for shooters who own military-style guns

Counter-terrorism expert Greg Barton identified one of the weapons used in the killings as a AR-15, the same assault rifle used in the 2017 Las Vegas mass shooting

TIMELINE OF TERROR

A 28-year-old Australian man entered a mosque in central Christchurch on Friday afternoon and opened fire on people gathered inside the building – killing at least 49 people and leaving more than 20 seriously injured.

This is how the incident unfolded in local New Zealand Time.

1.40pm: First reports of a shooting at a mosque in central Christchurch.

A man entered the mosque with an automatic weapon and opened fire on people inside.

2.11pm: Police confirmed they were attending an ‘evolving situation’ in Christchruch.

Gunshots are heard in the area outside Masid Al Noor Mosque on Deans Avenue.

Witnesses reported hearing multiple gunshots, with one saying she attempted to give CPR to an injured person but they died.

2.17pm: Multiple schools went into lockdown in Christchurch.

People who were in the mosque began to leave covered in blood and with gunshot wounds.

2.47pm: First reports of six people dead, three in a critical condition and three with serious injuries.

2.54pm: Police Commissioner Mike Bush said the situation is ‘serious and evolving’ and told people to remain indoors and stay off the streets.

The Canterbury District Health Board activated its mass casualty plan.

3.12pm: New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern cancelled her afternoon arrangements.

3.21pm: Christchurch City Council locked down many of their central city buildings.

3.33pm: First reports of a bomb in a beige Subaru that crashed on Strickland Street, three kilometres from the shootings.

3.40pm: Police confirmed there were multiple simultaneous attacks on mosques in Christchurch.

3.45pm: Reports of multiple shots fired at the shootings, which are ongoing.

3.59pm: 300 people were reported to be inside the moque.

4.00pm: One person is confirmed to be in custody but there are warnings there may be others out there.

Police commissioner Mike Bush urges Muslims across New Zealand to stay away from their local mosque.

4.10pm: Jacinda Ardern calls Friday ‘one of New Zealand’s darkest days’.

5.27pm: First reports of a second shooting.

A witness said a Muslim local chased the shooters at the mosque in Linwood, firing in ‘self defence’.

5.31pm: Four people are confirmed to be in custody. including one woman.

Multiple fatalities were reported.

7.07pm: It was confirmed an AR15 rifle was used in the attack.

7.20pm: Dunedin Street was cordoned off.

Reports the attackers planned to also target the Al Huda Mosque.

7.26pm: At least 40 people were confirmed dead, Jacinda Ardern confirmed.

7.34pm: Confirmed that 48 people were being treated in hospital.

7.46pm: Britomart train station in central Auckland was evacuated after bags were found unattended.

The bags were deemed not suspicious.

8.35pm: New Zealand’s Government confirmed this is the first time ever the terror level has been lifted from low to high.

9.03pm: Police Commissioner Mike Bush confirms that the death toll has risen to 49.

He also confirmed that a man in his late twenties was charged with murder.

Scott Williams, Bruce Rifle Club vice-president, told the Otago Daily Times Tarrant is a club member and practised shooting at the range.

Mr Williams said he could remember Tarrant shooting an AR-15 – used in a number of US massacres – as well as a hunting rifle.

A person with a standard firearms licence can buy an AR-15 in New Zealand but have limits on how they can be adapted.

Masjid Al Noor Mosque on Deans Avenue was one of the scenes of the mass shooting. At least one gunman opened fire at around 1:40 pm local time after walking into the Masjid Al Noor Mosque, killing at least 49 people

A man reacts as he speaks on a mobile phone near a mosque in central Christchurch, New Zealand. He is pictured after multiple people were killed in mass shootings at Al Noor mosque and the Linwood Masjid when they were full of people attending Friday prayers

Worried people wait outside one of the mosques Christchurch. At least 49 people were killed in the mass shootings on Friday

Police escort witnesses away from a mosque in central Christchurch, yesterday. Police warned people who live nearby to stay indoors

HOW THE AR-15 IS THE WEAPON OF CHOICE FOR MASS SHOOTERS

Aurora, Sandy Hook, San Bernardino, Orlando, Las Vegas, Parkland, Waffle House.

All have witnessed gun violence carried out by a killer brandishing an AR-15 or AR-15-style assault weapon, America’s weapon of choice for mass shootings.

Dubbed ‘America’s Most Popular Rifle’ by the NRA, it is estimated that there are eight million of the powerful – and affordable – weapons across the nation. It is accurate, relatively lightweight and has low recoil.

Gun experts claim the reason mass shooters gravitate towards AR-15s is mainly due to a ‘copy cat’ mentality as opposed to more precise gun knowledge.

June 20, 2012: James Holmes, 24, uses an AR-15-style .223-caliber Smith and Wesson rifle with 100-round magazine, among other firearms to kill 12 and injure 58 while dressed as The Joker from Batman at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado.

December 14, 2012: Adam Lanza, 20, shoots dead 20 children between the age of six and seven, as well as six members of staff at Sandy Hook Elementary School. Prior to driving to the school he shot and killed his mother at their Newtown home. Amongst his arsenal was a Bushmaster AR-15, where he fired off more than 150 rounds in less than five minutes.

December 2, 2015: Syed Rizwyan Farook, 28, and Tashfeen Malik, 27, use two AR-15-style .223-caliber Remington rifles and two 9mm handguns to kill 14 and injure 21 as his workplace in San Bernardino, California, before being killed by police.

June 12, 2016: Omar Mateen, 29, bursts into the Orlando Pulse nightclub, using an AR-15-style rifle – a Sig Sauer MCX – as well as a 9mm Glock semi-automatic pistol to kill 49 and injure 50.

October 1, 2017: Stephen Paddock, 64, uses a wide arsenal of guns, including an AR-15 to kill 58 and injure hundreds more at a music festival in Las Vegas. He doesn’t even have to leave his hotel room at the Mandalay Bay hotel which overlooks the festival to carry out the worst mass shooting in US history. He commits suicide in the room.

November 5, 2017: Devin Kelley, 26 uses an AR-15 style Ruger rifle to kill 26 people at a church in Sutherland Springs, Texas, before being killed.

February 14, 2018: Nikolas Cruz, 19, uses an AR-15-style rifle to kill at least 17 students and teachers at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. Cruz is captured and is currently awaiting trial.

April 22, 2018: Travis Reinking, 29, armed with an AR-15-style rifle opens fire on a Waffle House in Tennessee, killing four people and injuring two more. He is prevented from killing more by James Shaw Jr, who hid near the restaurant’s bathrooms and rushed the shooter, wrestling the rifle away. The gunman is captured 24 hours later.

Mr Williams said Tarrant had never mentioned anything about his feelings towards Muslims and seemed ‘as normal as anyone else’.

‘I think we’re feeling bit stunned and shocked and a bit betrayed, perhaps, that we’ve had this person in our club who has ended up doing these horrible things,’ Mr Williams said.

Tarrant joined the rifle club at the start of 2018 and was said to help out around the range.

‘He was always there helping out with any work that was needed around the club, or when it came to set up or pack down the range.’

The club, which has just over 100 members, is in a state of shock, Mr Williams added.

Shocked family members stand outside the mosque following a shooting resulting in multiple fatalies and injuries at the Masjid Al Noor on Deans Avenue in Christchurch

Armed Offenders Squad push back members of the public following the shooting which saw multiple fatalies and injuries at the Masjid Al Noor on Deans Avenue in Christchurch, New Zealand

Bloodied bandages on the road following a shooting at the Al Noor mosque in Christchurch yesterday

A spokesman for the club told Stuff: ‘We are assisting [police] with their investigation.’

‘He seemed a reasonably normal sort of dude.’

It was also revealed that a man by the name of Brenton Tarrant had bought a hunting rifle from a sports store in Dunedin in 2017.

But Darren Jacobs, chief executive officer of Hunting & Fishing NZ stores, said store workers did not recognise Tarrant from court pictures.

Yet he had a firearms licence and a record of a sale to a man of that name was found.

Mr Jacobs told Otago Daily Times: ‘We have recorded a single sale to an individual going by that name in 2017, and that sale was for a bolt-action hunting rifle.’

Police console a man on a grass verge outside a mosque in central Christchurch after the shootings

But he added there was no evidence Tarrant bought a semi-automatic rifle from the store – which do not sell them as a rule.

New Zealand has around one firearm for every four people and does not ban semi-automatic weapons.

The country’s gun laws have remained largely unchanged since 1992, when the 1983 law was toughened in response to another massacre which saw 13 people die.

A counter-terrorism expert said a military-style assault rifle allegedly used in Friday’s Christchurch massacre has never been seen before in Australia and New Zealand.

Deakin University counter-terrorism expert Greg Barton identified one of the weapons as a AR-15, the same assault rifle used in the 2017 Las Vegas mass shooting that killed 58 people.

‘We haven’t seen these assault weapons used in Australia and New Zealand,’ Mr Barton told ABC News.

‘I think now we’ve got to face the fact that they’re at large.’

New Zealand’s worst mass shooting has put the country’s current regulations of owning a semi-automatic military-style weapon under scrutiny.

Mr Barton questioned how Tarrant allegedly obtained the powerful weapons.

‘You would have thought getting an assault rifle was very hard, not like it is in America where it’s very easy,’ he said.

A former armed offenders squad member said some of the semi-automatic weapons Tarrant allegedly used were very similar to what police and the military use.

‘Those weapons he had you can purchase with a normal firearms licence,’ he told Stuff.

‘It’s not the first time he’s ever fired those types of weapons. He’s fired them before.’

In the wake of yesterday’s attack, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern said there would be immediate changes to firearms laws.

She said: ‘I can tell you one thing right now, our gun laws will change.’

Ms Ardern said in a press conference the white supremacist attacker had used five firearms in the attack, including two semi-automatic weapons, two shotguns and a lever action firearm.

She said she had been advised the gunman obtained a Category A licence in November 2017, and ‘under that, he was able to acquire the guns that he held’.

‘While work has been done as to the chain of events that led to both the holding of this gun licence and the possession of these weapons, I can tell you one thing right now, our gun laws will change,’ Ms Ardern told media.

She went on to say she had instructed government bodies to ‘report to Cabinet on Monday on these events with a view to strengthening our systems on a range of fronts including, but not limited to, firearms, border controls, enhanced information-sharing with Australia, and any practice reinforcement of our watch list processes’.

‘Now is the time for change,’ she added.

Ms Ardern said she would like to see semi-automatic weapons banned and was one of the issues she was looking ‘at with immediate effect.’

JACINDA ARDEN’S SPEECH

We believe that 40 people have lost their lives in this act of extreme violence. Ten have died at Linwood Avenue mosque. Three of which were outside the mosque itself. A further 30 have been killed at Deans Avenue mosque. There are also more than 20 seriously injured who are currently in Christchurch A&E.

It is clear that this can now only be described as a terrorist attack. From what we know, it does appear to have been well planned. Two explosive devices attached to suspect vehicles have now been found and they have been disarmed. There are currently four individuals that have been apprehended, three are connected to this attack who are currently in custody. One of which has publicly stated that they were Australian-born.

These are people who I would describe as having extremist views, that have absolutely no place in New Zealand, and in fact have no place in the world. While we do not have any reason to believe at this stage that there are any other suspect, we are not assuming that at this stage.

The joint intelligence group has been deployed and police are putting all of their resources into the situation. The Defence Force are currently transporting additional police staff to the region. The national security threat level has been lifted from low to high.

I want to ensure people that all of our agencies are responding in the most appropriate way. That includes at our borders. Air New Zealand has cancelled all turboprop flights out of Christchurch tonight and will review the situation in the morning.

Jet services domestically andinternationally are continuing to operate. I say again, there is heightened security. That is of course, we can assure people of their safety, and police are working hard to ensure that people are able to move around the city safely. I have spoken this evening to the mayor of Christchurch, and I intend to speak this evening to the imam, … but I would like to speak directly to the people impacted.

Christchurch was the home of these victims. For many, this may not have been the place they were born. In fact, for many, New Zealand was their choice. The place they actively came to and committed themselves to. The place they were raising their families, with communities who loved them and who they loved. The place where they came for safety. Where they were free to practise their culture and their religion.

For those of you who are watching at home tonight, in questioning how this could have happened here, we, New Zealand, we were not a target because we are safe harbour for those who hate. We were not chosen for this act of violence because we condone racism, because we are in enclave for extremism, we were chosen for the fact that we are none of these things.

It was we represent diversity, kindness, compassion, a home for those who share our values and a refuge for those who need it. And those values I can assure you will not and cannot be shaken by this attack. We are proud nation of more than 160 languages and amongst that diversity we share common values, and the one that we place the currency on right now and tonight is our compassion, and the support of the community of those directly affected by this tragedy. And secondly, the strongest possible condemnation of the ideology of the people who did this.

You may have chosen us, but we are utterly reject and condemn you.

Sorry we are not currently accepting comments on this article.

The post Christchurch terror suspect was member of New Zealand gun club appeared first on Gyrlversion.

from WordPress https://www.gyrlversion.net/christchurch-terror-suspect-was-member-of-new-zealand-gun-club/

0 notes

Text

Nature Teaching in the Age of School Shootings

Nature Teaching in the Age of School Shootings Nature Teaching in the Age of School Shootings http://www.nature-business.com/nature-teaching-in-the-age-of-school-shootings/

Nature

On Jan. 23, three weeks into the spring semester, a 15-year-old sophomore named Gabe Parker brought his stepfather’s 9-millimeter Ruger handgun to Marshall County High School in Western Kentucky, opened fire on the more than 600 students who were milling about the main common area waiting for the morning bell to ring, then dropped his weapon near the auditorium and disappeared into the chaos he had created.

Teachers were the first responders. Before police officers and medics arrived, they gathered sobbing, vomiting, bleeding kids into the safest rooms they could find, then locked the doors and kept vigil with them through the stunned and terrified wait. They shepherded the injured to hospitals in their own cars. And they knelt on the ground with the ones who were too wounded to move, stanching blood flow with their own hands and providing whatever comfort and assurance they could muster.

For the history teacher Erin Mathis, those few minutes passed like hours. She was not in the commons during the shooting, but when the health teacher screamed that students had been shot, she and a few others found themselves running toward where the sound of bullets had been heard. Mathis, whose only medical experience consisted of candy-striping as a preteen, prayed as she ran. God, you are going to have to do this. Because I cannot.

Superintendent Trent Lovett was just walking into his office, a short distance from the high school, when Principal Patricia Greer called to tell him that at least one student was down. He jumped back in his truck and raced up the access road that connected the two buildings, calling his own freshman daughter along the way to make sure she was safe. When he arrived, he saw that several students had been shot and that each of them was being attended to by at least one faculty or staff member. They had no clue where the shooter was, or if he was coming back, Lovett thought. And they didn’t know if there were other shooters — or bombs or other weapons — in the offing. Hadn’t some mass shooters rigged their targets in advance with explosives? Police and ambulance were on their way, his own daughter was safe and the students who weren’t wounded had either fled or were hiding with other educators. So Lovett did the next thing he could think to do: He grabbed an aluminum bat from an abandoned bag of sports equipment and went looking for the teenage boy with the gun.

Parker had slipped into the weight room, where Rob McDonald, a gym teacher and baseball coach, was keeping watch over 75 or so other frantic students whom he had managed to shelter from the panic. Two of those students had been shot. Two others approached McDonald and, in a whisper, informed him that the shooter was among them. While his teacher’s aide went to call a school administrator, McDonald moved across the room as discreetly as possible, positioned himself right behind the boy in question and braced himself for trouble. If he moves, McDonald thought, I’ll floor him. Parker’s hands were tucked into his coat pockets. It was a winter coat, and McDonald could not tell if it contained a gun. He thought briefly about what he might do if he could reach his own gun, which was in the glove box of his car. But the truth was, he had no way of knowing if this was the right kid or not. It seemed incredible to him that a boy would shoot up the school and then hide with his own victims. He was still in doubt when police officers came to the weight room several minutes later and aimed their own weapons at the boy. Not until he heard those cops ask Parker where the gun was, and watched Parker answer calmly, without denying anything, did the truth finally sink in.

Lovett returned to the commons and took stock. The floor was slicked with blood and spilled beverages and littered with abandoned backpacks. Dozens of cellphones rang without pause. One staff member was tending to Preston Cope, a sophomore whose family Lovett knew well and who appeared to have been shot in the head. Cope’s phone was ringing, too, and for a split second Lovett considered ignoring it. The screen read “Dad,” and Lovett was not practiced in delivering such news. But he quickly thought better of that impulse, remembering how desperate he had been for information after one of his own children was in an ultimately fatal car accident. He answered the phone, told Cope’s father that his son was not O.K., then issued a quick string of instructions: Hurry. Be safe. Pray.

By then, medics were starting to arrive, and a tortured bureaucracy was being erected around the mayhem. Lovett and Greer set up a system to field incoming calls and deployed staff members to each hospital that was receiving injured students. In all, 16 students had been shot, two of whom would die: Preston Cope on the way to the hospital, and Bailey Holt right there in the commons. Holt’s parents were looking for her at the middle school, where students were being bused and where parents were being told to go. Lovett arranged for them to be taken to the meeting room in a nearby fire station and went with two officers to meet them there. They shouldn’t have to hear it in front of everyone, he thought. This time, though, he didn’t have to say a word. When the girl’s parents turned the corner and saw only Lovett waiting for them, they knew their daughter was dead.

For all the fear they inspire, school shootings of any kind are technically still quite rare. Less than 1 percent of all fatal shootings that involve children age 5 to 18 occur in school, and a significant majority of those do not involve indiscriminate rampages or mass casualties. It has been two decades since Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold ushered in the era of modern, high-profile, high-casualty shootings with their massacre at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colo. According to James Alan Fox, a criminologist at Northeastern University, just 10 of the nation’s 135,000 or so schools have experienced a similar calamity — a school shooting with four or more victims and at least two deaths — since then. But those 10 shootings have had an outsize effect on our collective psyche, and it’s not difficult to understand why: We are left with the specter of children being gunned down en masse, in their own schools. One such event would be enough to terrify and enrage us. This year, we had three.

Teachers are at the quiet center of this recurring national horror. They are victims and ad hoc emergency workers, often with close ties to both shooter and slain and with decades-long connections to the school itself. But they are also, almost by definition, anonymous public servants accustomed to placing their students’ needs above their own. And as a result, our picture of their suffering is incomplete.

[Watch educators as they tell us in their own words about what it’s like to to teach in an era of school shootings.]

We know that the trauma that teachers experience after a school shooting can be both severe and enduring. “Their PTSD can be as serious as what you see in soldiers,” says Robert Pynoos, co-director of the federally funded National Center for Child Traumatic Stress, which helps schools coordinate their responses to traumatic events. “But unlike soldiers, none of them signed up for this, and none of them have been trained to cope with it.” We know that teachers who were least able to protect their students in the moment tend to be especially traumatized. “For teachers, the duty to educate students is primary,” Pynoos says. “But the urge to protect those students is deeper than that. It’s primal.” And we know that their symptoms can include major sleep disturbance, hair-trigger startle responses and trouble regulating emotions.

But we don’t know much else. Researchers have calculated the rates of PTSD for a host of other traumatic experiences, estimating that it affects up to 20 percent of combat soldiers and 40 percent of rape survivors. But we have no analogous statistics for educators who survive school shootings, nor any sense of how such an experience — not to mention its hyperpoliticized, media-frenzied aftermath — might affect their ability to teach or their long-term career trajectories. “Those are important questions that really need further study,” Pynoos says.

In the meantime, teachers who survived shootings are doing what they can to fill in the blanks themselves. Paula Reed, an English teacher who once taught Dylan Klebold and who retired from Columbine this spring, says that she and her colleagues reach out to schools after every incident — “Columbine always calls,” she says — to offer support and answer whatever questions they can. The questions, she says, are always the same: How long until I feel better? Will I ever be able to teach again? When will I get my old self back? Reed tries to tell the teachers the things she wishes someone had told her, starting with the fact that it takes years — not weeks — to recover. “You’d be surprised how many people don’t get that,” she says. “Six weeks after Sandy Hook, some parents and spouses were already asking why the teachers weren’t better yet.”

For years, she and a few others had these conversations through an informal network. A shooting would make headlines, and they would contact the school directly, or teachers would come to them independently, seeking perspective and guidance. This year, Reed created a private Facebook page specifically for fellow educator-survivors. It has 62 members so far. “This was my last year teaching,” Reed says. “And it was, sadly, filled with school shootings.” Four weeks after the Marshall County shooting, a former student killed three educators and 14 students and wounded 17 others at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla. And three months after that, another school shooter, in Santa Fe, Tex., killed eight students and two teachers and injured 13 others.

In the aftermath of those events, politicians, policymakers, health officials and entrepreneurs have proffered a litany of solutions to what is now commonly thought of as the school-shooting problem. Among other things, schools have been advised to teach teachers to use tourniquets; ramp up active-shooter drills; get rid of active-shooter drills; ban backpacks; make backpacks bulletproof; teach teachers to teach compassion. Forget compassion, teach them to use guns. Forget compassion and guns and teach them how to identify budding psychopaths before they blossom into murderers. For the teachers themselves, each demand brings its own implicit expectations and its own fresh roster of uncertainties. Should they be prepared to take a bullet for their charges? To shoot one student for the sake of protecting others? Is it their job to prevent these things from happening in the first place?

Regular coursework was quasi-suspended after the Marshall County shooting, but the teachers still had lessons to impart. Jenny Darnall and Kelly Weaver, who taught English and history, respectively, wanted to make sure their students took stock of the kindness enveloping the school. Look at the banners and letters and cards pouring in from across the country, they told them. Look at the comfort quilts and comfort dogs and comfort food. See the fellowship in it. And remember: When the time comes, you will do the same for others.

Cory Westerfield, a teacher of algebra and German and the girls’ track coach, was adamant that his students not live in fear forever. When the starting pistol sent one of his star athletes into a panic, right as she was preparing to do the triple jump, he coaxed her onto the field, gently but firmly. “You’re going to walk down there really, really slowly,” he said, pointing to the other side of the field. “And then walk back really, really slowly.” Living in fear was not really living, he told her. It was just existing. And he wanted them to do more than just exist.

The teachers were harder on themselves, though. They, too, had meltdowns: in rushing crowds, at airports, when they were momentarily separated from their own children. They sometimes berated themselves for these reactions, aware that others around them had been through much worse. Westerfield thought of Mathis’s getting literal blood on her hands and felt ashamed of his own tears. Mathis thought of other teachers — who, after the E.M.T.s took the most severely injured away, followed the trails of blood to other students who needed help — and despaired that she had not gone with them. Kelly Weaver thought of her own children and how, at the end of the day, she could still go home and hug them.

What troubled Westerfield most was that none of them had seen it coming. After two decades of teaching, he considered himself a skilled reader of teenagers. He liked to think he could tell when something was bothering one of them just by how they walked into his classroom. But with this boy — this shooter — he had detected nothing. Parker sat in Westerfield’s German class for two school years in a row. He could hold an adult conversation. He had friends. He was making decent grades. And, as far as anyone could tell, he was not being bullied. (Parker’s trial date is pending, and in the absence of a plea from his lawyer, the judge in the case has entered an automatic plea of not guilty.) If a boy like that could suddenly turn murderous, then in theory, any one of their students could do anything. Whom could they trust — how could they trust — after something like this? And if the answer was that they couldn’t, what then?

Jenny Darnall decided to re-evaluate her understanding of what it meant to be a teacher in the first place. She had never been particularly compassionate with the students. The way she saw it, her job was to educate them, not give them advice they should be getting from their parents. But now, she felt as if God were telling her to step up and do more: Call parents more and tell them the hard truths she might normally expect them to discover on their own. Talk to the kids more too. Tell them that they are loved, even when they’re being terrible. Those things did not feel like part of her job. But maybe now they would have to be.

The school’s culinary instructor, Amy Cathey, was uncertain about these shifting boundaries. A few students had called her seeking practical advice about how to navigate their trauma outside school — for instance, how to tell their own parents that the prospect of lighting fireworks terrified them. Cathey didn’t mind the calls, or the questions. But she wondered what would happen when she wasn’t there. She worried about the graduating seniors. And she dreaded returning to anything resembling those eight or so weeks after the shooting, when it felt as if she took care of everyone except herself. She loved her kids. But she also knew herself, and she knew she couldn’t sustain that anymore.

In May, Marshall Strong signs were still everywhere; they wobbled in people’s front yards, hung from doors in floral wreaths, peeked out the back windows of cars. There were even some billboards still up along the highway. Some of the teachers had grown weary of these signs. They weren’t over what had happened, of course. But they were ready to will themselves into the next phase of recovery, whatever that might be. This was a tricky place to be, in part because not everyone reached it at the same time. Westerfield waited until the school year officially ended, and not a second longer, to take the Marshall Strong sign out of his own yard.

But Mathis couldn’t bring herself to take the Marshall Strong bracelet off, and her husband was worried. They lost a pregnancy early in their marriage, and he remembered how afterward she refused to remove the hospital bracelet; doing so, he suspected, would somehow make the miscarriage real to her. He worried that the Marshall bracelet was having the same effect — facilitating a denial that would ultimately keep her from moving on. She managed to tuck the bracelet away in a drawer by summer, but even then, a part of her wanted to put it back on, as if by doing so she could unmake the entire nightmare.

One weekend in July, Cathey drove from Kentucky to Colorado, to meet Paula Reed in person. The women had connected on Facebook, and had been texting and emailing for weeks. If the trip sounded crazy to outside observers, it made perfect sense to Reed. Driving cross-country with a small child in tow was a great way to distract a traumatized brain. Over breakfast at a diner, the two women reviewed the map of their shared reality. The terrain was deeply familiar to Reed but still painfully new to Cathey. They took turns pointing out various landmarks and junctures — the last funeral, the first school shooting after yours — and nodding in emphatic relief. Yes, that happened to us too. Yes, we had the same problem exactly.

From the inside, a mass shooting can feel distinctly unchartable. But Reed — and Pynoos, and Melissa Brymer, his colleague at the National Center for Child Traumatic Stress — say that while each school shooting is different in its particulars, several features are common to all. For example, Brymer says, it can be the secondary trauma that undoes a school’s recovery. “After a shooting, everyone wants to talk about how to find the next shooter so that this doesn’t happen again,” Brymer says. “But that’s not what the school itself needs to focus on. We’ve had suicides, car accidents, overdoses.” For a school that’s already traumatized, she says, these follow-up events can be incredibly devastating.

Brymer advises schools to conduct mental-health screenings before anniversaries, to find the people who are struggling most and help them. The hierarchy of hurt can split in surprising ways. For the most part, people closest to the carnage are the most traumatized, and people farther away are less so. But any teacher might be plagued by any number of things, including what they saw and how they responded in the moment. One educator might flee the building in a panic, leaving his students behind, only to be devastated by guilt afterward. Another might behave heroically, then seethe with resentment over not getting enough recognition. Each will need counseling and support to fully recover.

A common lament among educator-survivors is the way that personal boundaries shift within the school community. Abbey Clements, who taught second grade at Sandy Hook, says that after the shooting, she would take her entire class to the bathroom at the same time, so that no one would have to leave her sight. But as they drew their students close, she says, she and her colleagues distanced themselves from one another. “You’re afraid that if you start talking about your own trauma, you might trigger someone else’s,” she says. “You’re also afraid of looking weak or unstable, afraid you’ll be asked to leave or take leave if you admit how much you’re struggling.”

As a result, many teachers bury their fear and anger and guilt, until it changes into something else entirely. The question of where to erect a memorial, or when to take one down, can create fierce divisions. So might similar questions about how long to allow comfort dogs on campus, or what to do with the mountain of gifts and condolences that pile up. Students may come close to blows over whether to discuss the shooting during class time. Teachers may feel close to doing the same. “It’s not all ‘Kumbaya,’ ” Clements says. “When the system is cracked by a trauma of this magnitude, a lot of stuff leaks out. It gets messy. And it can change relationships.”

The job itself also changes. Reed spent the rest of her career vaguely wary of all her students. “You still love them,” she says, “and you still bond with them. But you never again feel certain that none of them would ever kill you.” Even teachers who love what they do may think about doing something else. “If your bank got robbed while you were in it, you would never go to that bank again,” Clements says. “But with this, you have to go back every single day.” And leaving is not as easy as it sounds. Relocating can cost hard-won seniority and the salary that goes with it. And separating yourself from the people you just survived a shooting with can be excruciating. “They’re the people that trigger you most,” Clements says. “But they’re also the only ones who understand what you’re going through. Because how can anyone understand this that hasn’t been through it?”

Since the Parkland shooting, at least 14 states have introduced measures that would enable educators to carry firearms on the job. The idea itself is not new; we’ve been debating it since at least 2006, when a gunman killed five children in a one-room schoolhouse in western Pennsylvania. But as the proposed measures indicate, lawmakers seem to be considering it with renewed urgency. Teachers have largely resisted this call to arms, pointing out that it would alter the student-teacher dynamic in irrevocable ways. “My job is to educate and nurture students,” Mathis says. “How am I supposed to then also be prepared to shoot one of them?”

Matthew Mayer, a professor of educational psychology at Rutgers’ Graduate School of Education, says that among experts the best solutions to school shootings are not really in dispute: basic gun control, more and better mental-health services and a robust national threat-assessment program. We also need to help educators create an atmosphere where students who hear about a potential threat feel comfortable sharing that information with adults. (Many student shooters, including Gabe Parker at Marshall County, hint about their plans to at least one other person or tell them outright. Getting those others to inform teachers is one of our best options for preventing shootings from happening in the first place.)

In February, Mayer and his colleagues circulated an eight-point document titled “A Call for Action to Prevent Gun Violence in the United States of America,” which summarized these and other key actions needed to reduce the risk of school shootings. So far, 4,400 educators and public-health experts have signed it. But political will is still missing. “We keep revisiting the same conversations every five or six years without learning or changing much of anything,” Mayer says. “Armed guards and metal detectors make it look like you’re doing something. You get far fewer points for talking about school climate and mental health.”

The Marshall County school district banned book bags, installed metal detectors at the high school and hired four additional resource officers (armed deputy sheriffs). But Superintendent Lovett agrees that much more is needed. “We’ve made ourselves a fairly hard target,” he says. “But truthfully, can I sit here and guarantee you that it’s never going to happen again? No, I can’t.”

As summer waned and the new academic year approached, some Marshall teachers were feeling torn. Mathis found that while she was not afraid to return to work herself, she dreaded sending her own children, ages 6 and 10, back to their school. She knew that it was safe, and that they would be just fine. “I know nothing is going to happen there,” she told her colleagues. But she could not stop the next thought from coming: I thought nothing would happen here.

Before the shooting, Westerfield always said he would quit or retire early if something like this happened. “I’m not dying on the job,” he would quip. But returning felt like a sacred duty. How could any teacher who might replace him possibly understand what his students had been through? For that matter, how would any other school district understand what he had been through? At the same time, though, he was weary with grief. “There’s this thing inside each of us now,” he said. “We’ve lost something that we can never get back.”

For Superintendent Lovett, who graduated from Marshall some 35 years ago, it came down to the simple fact that times had changed. Back then, as many kids as not had hunting rifles in their trucks, and no one ever brought a gun into the building. But, he thought, it was the lot of educators to serve as a constant, for both their students and the wider community. In four short years, every kid who survived the shooting would be gone from the school. For the most part, faculty and staff members would remain. They helped their students through the shooting and its excruciating aftermath. And they would be there this fall to see them through the year that followed. “Students eventually move on,” he said. “Educators really don’t.”

Read More | https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/09/05/magazine/school-shootings-teachers-support-armed.html | Jeneen Interlandi

Nature Teaching in the Age of School Shootings, in 2018-09-09 22:43:27

0 notes

Text

Nature Teaching in the Age of School Shootings

Nature Teaching in the Age of School Shootings Nature Teaching in the Age of School Shootings https://ift.tt/2QiSLmk

Nature

On Jan. 23, three weeks into the spring semester, a 15-year-old sophomore named Gabe Parker brought his stepfather’s 9-millimeter Ruger handgun to Marshall County High School in Western Kentucky, opened fire on the more than 600 students who were milling about the main common area waiting for the morning bell to ring, then dropped his weapon near the auditorium and disappeared into the chaos he had created.

Teachers were the first responders. Before police officers and medics arrived, they gathered sobbing, vomiting, bleeding kids into the safest rooms they could find, then locked the doors and kept vigil with them through the stunned and terrified wait. They shepherded the injured to hospitals in their own cars. And they knelt on the ground with the ones who were too wounded to move, stanching blood flow with their own hands and providing whatever comfort and assurance they could muster.

For the history teacher Erin Mathis, those few minutes passed like hours. She was not in the commons during the shooting, but when the health teacher screamed that students had been shot, she and a few others found themselves running toward where the sound of bullets had been heard. Mathis, whose only medical experience consisted of candy-striping as a preteen, prayed as she ran. God, you are going to have to do this. Because I cannot.

Superintendent Trent Lovett was just walking into his office, a short distance from the high school, when Principal Patricia Greer called to tell him that at least one student was down. He jumped back in his truck and raced up the access road that connected the two buildings, calling his own freshman daughter along the way to make sure she was safe. When he arrived, he saw that several students had been shot and that each of them was being attended to by at least one faculty or staff member. They had no clue where the shooter was, or if he was coming back, Lovett thought. And they didn’t know if there were other shooters — or bombs or other weapons — in the offing. Hadn’t some mass shooters rigged their targets in advance with explosives? Police and ambulance were on their way, his own daughter was safe and the students who weren’t wounded had either fled or were hiding with other educators. So Lovett did the next thing he could think to do: He grabbed an aluminum bat from an abandoned bag of sports equipment and went looking for the teenage boy with the gun.

Parker had slipped into the weight room, where Rob McDonald, a gym teacher and baseball coach, was keeping watch over 75 or so other frantic students whom he had managed to shelter from the panic. Two of those students had been shot. Two others approached McDonald and, in a whisper, informed him that the shooter was among them. While his teacher’s aide went to call a school administrator, McDonald moved across the room as discreetly as possible, positioned himself right behind the boy in question and braced himself for trouble. If he moves, McDonald thought, I’ll floor him. Parker’s hands were tucked into his coat pockets. It was a winter coat, and McDonald could not tell if it contained a gun. He thought briefly about what he might do if he could reach his own gun, which was in the glove box of his car. But the truth was, he had no way of knowing if this was the right kid or not. It seemed incredible to him that a boy would shoot up the school and then hide with his own victims. He was still in doubt when police officers came to the weight room several minutes later and aimed their own weapons at the boy. Not until he heard those cops ask Parker where the gun was, and watched Parker answer calmly, without denying anything, did the truth finally sink in.

Lovett returned to the commons and took stock. The floor was slicked with blood and spilled beverages and littered with abandoned backpacks. Dozens of cellphones rang without pause. One staff member was tending to Preston Cope, a sophomore whose family Lovett knew well and who appeared to have been shot in the head. Cope’s phone was ringing, too, and for a split second Lovett considered ignoring it. The screen read “Dad,” and Lovett was not practiced in delivering such news. But he quickly thought better of that impulse, remembering how desperate he had been for information after one of his own children was in an ultimately fatal car accident. He answered the phone, told Cope’s father that his son was not O.K., then issued a quick string of instructions: Hurry. Be safe. Pray.

By then, medics were starting to arrive, and a tortured bureaucracy was being erected around the mayhem. Lovett and Greer set up a system to field incoming calls and deployed staff members to each hospital that was receiving injured students. In all, 16 students had been shot, two of whom would die: Preston Cope on the way to the hospital, and Bailey Holt right there in the commons. Holt’s parents were looking for her at the middle school, where students were being bused and where parents were being told to go. Lovett arranged for them to be taken to the meeting room in a nearby fire station and went with two officers to meet them there. They shouldn’t have to hear it in front of everyone, he thought. This time, though, he didn’t have to say a word. When the girl’s parents turned the corner and saw only Lovett waiting for them, they knew their daughter was dead.

For all the fear they inspire, school shootings of any kind are technically still quite rare. Less than 1 percent of all fatal shootings that involve children age 5 to 18 occur in school, and a significant majority of those do not involve indiscriminate rampages or mass casualties. It has been two decades since Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold ushered in the era of modern, high-profile, high-casualty shootings with their massacre at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colo. According to James Alan Fox, a criminologist at Northeastern University, just 10 of the nation’s 135,000 or so schools have experienced a similar calamity — a school shooting with four or more victims and at least two deaths — since then. But those 10 shootings have had an outsize effect on our collective psyche, and it’s not difficult to understand why: We are left with the specter of children being gunned down en masse, in their own schools. One such event would be enough to terrify and enrage us. This year, we had three.

Teachers are at the quiet center of this recurring national horror. They are victims and ad hoc emergency workers, often with close ties to both shooter and slain and with decades-long connections to the school itself. But they are also, almost by definition, anonymous public servants accustomed to placing their students’ needs above their own. And as a result, our picture of their suffering is incomplete.

[Watch educators as they tell us in their own words about what it’s like to to teach in an era of school shootings.]

We know that the trauma that teachers experience after a school shooting can be both severe and enduring. “Their PTSD can be as serious as what you see in soldiers,” says Robert Pynoos, co-director of the federally funded National Center for Child Traumatic Stress, which helps schools coordinate their responses to traumatic events. “But unlike soldiers, none of them signed up for this, and none of them have been trained to cope with it.” We know that teachers who were least able to protect their students in the moment tend to be especially traumatized. “For teachers, the duty to educate students is primary,” Pynoos says. “But the urge to protect those students is deeper than that. It’s primal.” And we know that their symptoms can include major sleep disturbance, hair-trigger startle responses and trouble regulating emotions.

But we don’t know much else. Researchers have calculated the rates of PTSD for a host of other traumatic experiences, estimating that it affects up to 20 percent of combat soldiers and 40 percent of rape survivors. But we have no analogous statistics for educators who survive school shootings, nor any sense of how such an experience — not to mention its hyperpoliticized, media-frenzied aftermath — might affect their ability to teach or their long-term career trajectories. “Those are important questions that really need further study,” Pynoos says.

In the meantime, teachers who survived shootings are doing what they can to fill in the blanks themselves. Paula Reed, an English teacher who once taught Dylan Klebold and who retired from Columbine this spring, says that she and her colleagues reach out to schools after every incident — “Columbine always calls,” she says — to offer support and answer whatever questions they can. The questions, she says, are always the same: How long until I feel better? Will I ever be able to teach again? When will I get my old self back? Reed tries to tell the teachers the things she wishes someone had told her, starting with the fact that it takes years — not weeks — to recover. “You’d be surprised how many people don’t get that,” she says. “Six weeks after Sandy Hook, some parents and spouses were already asking why the teachers weren’t better yet.”

For years, she and a few others had these conversations through an informal network. A shooting would make headlines, and they would contact the school directly, or teachers would come to them independently, seeking perspective and guidance. This year, Reed created a private Facebook page specifically for fellow educator-survivors. It has 62 members so far. “This was my last year teaching,” Reed says. “And it was, sadly, filled with school shootings.” Four weeks after the Marshall County shooting, a former student killed three educators and 14 students and wounded 17 others at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla. And three months after that, another school shooter, in Santa Fe, Tex., killed eight students and two teachers and injured 13 others.

In the aftermath of those events, politicians, policymakers, health officials and entrepreneurs have proffered a litany of solutions to what is now commonly thought of as the school-shooting problem. Among other things, schools have been advised to teach teachers to use tourniquets; ramp up active-shooter drills; get rid of active-shooter drills; ban backpacks; make backpacks bulletproof; teach teachers to teach compassion. Forget compassion, teach them to use guns. Forget compassion and guns and teach them how to identify budding psychopaths before they blossom into murderers. For the teachers themselves, each demand brings its own implicit expectations and its own fresh roster of uncertainties. Should they be prepared to take a bullet for their charges? To shoot one student for the sake of protecting others? Is it their job to prevent these things from happening in the first place?

Regular coursework was quasi-suspended after the Marshall County shooting, but the teachers still had lessons to impart. Jenny Darnall and Kelly Weaver, who taught English and history, respectively, wanted to make sure their students took stock of the kindness enveloping the school. Look at the banners and letters and cards pouring in from across the country, they told them. Look at the comfort quilts and comfort dogs and comfort food. See the fellowship in it. And remember: When the time comes, you will do the same for others.

Cory Westerfield, a teacher of algebra and German and the girls’ track coach, was adamant that his students not live in fear forever. When the starting pistol sent one of his star athletes into a panic, right as she was preparing to do the triple jump, he coaxed her onto the field, gently but firmly. “You’re going to walk down there really, really slowly,” he said, pointing to the other side of the field. “And then walk back really, really slowly.” Living in fear was not really living, he told her. It was just existing. And he wanted them to do more than just exist.

The teachers were harder on themselves, though. They, too, had meltdowns: in rushing crowds, at airports, when they were momentarily separated from their own children. They sometimes berated themselves for these reactions, aware that others around them had been through much worse. Westerfield thought of Mathis’s getting literal blood on her hands and felt ashamed of his own tears. Mathis thought of other teachers — who, after the E.M.T.s took the most severely injured away, followed the trails of blood to other students who needed help — and despaired that she had not gone with them. Kelly Weaver thought of her own children and how, at the end of the day, she could still go home and hug them.