#raskolnikov is the only human obviously

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

once again thinking about my (thus far unproduced) magnum opus: a crime and punishment muppet movie

#raskolnikov is the only human obviously#it's a perfect visual metaphor for his alienation from society and is also funny as fuck#in an ideal world he would be played by Cillian Murphy but I think at this point the man may be too old#so I'd have to find someone else with the graceful and devastating features of a cemetery angel....sigh....#because unfortunately raskolnikov is beautiful and that's why everyone tolerates his deranged behavior#razumikhin is rowlf the dog#Sonya is camilla the chicken#dunya is miss piggy#svidrigailov is either uncle deadly or kermit playing against his usual type which would be very interesting#and porfiry is gonzo#ok that's enough I could talk about this for hours

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

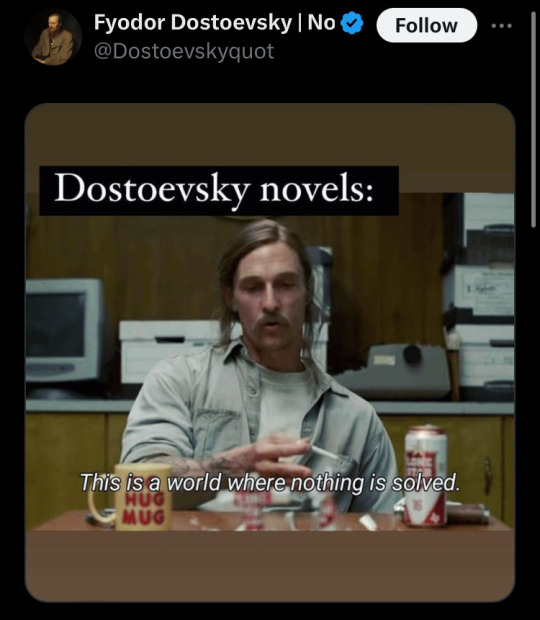

So funny when people pretend Dostoevsky is like that when his novels are full of hope. Obviously he portrays the depths of human despair and our flaws very well but that’s the only way to also show hope!! like raskolnikov not just at the end of crime and punishment but throughout the book…And the entirety of the brothers Karamazov ? And prince myshkin’s entire character ? Fake Fyodor lovers I spotted you !!!!!!

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey first just wanna say it’s cuz of you that I caught an intrigue for Russian literature, and have decided to read most of dostoevskys bibliography, and I just finished crime and punishment. Obviously I’m absolutely floored by the entire thing but someone that stood out to me was svirdgailov. Those last couple scenes of him were absolutely amazing and had me reeling, I wanted to know your opinion on him

Hello! And ahhh I'm so happy to hear that!!

Svidrigailov is indeed a very interesting character. He's an antagonist, but the vast majority of his crimes are in the past. Yet they're significant: he rapes an underage girl and she commits suicide. He murders his wife. He propositions Dunya and then corners her. But he also then does some charitable things like actually providing for Sonya's stepsiblings after Katarina dies, and giving Sonya enough money to leave her profession and move to Siberia with Raskolnikov.

So, he's done the worst deeds imaginable in the story--worse than Raskolnikov. And rather than face guilt, he kills himself. Yet, he also is the one who provides for others for absolutely no benefit to himself.

You'll often find Sonya and Svidrigailov compared as foils who represent two alternate paths for Raskolnikov: life or death, suffering or escape.

Rask is obviously another foil. Raskolnikov's name means "schism." and that's because he's both extremely generous and extremely cruel--kinda like Svid. He also donates all his money to Marmeladov's family before he even knows them, when it benefits him not at all. Yet he murders Alyona to benefit humanity... and Lizaveta to protect himself.

The guilt over his crimes haunts him and forces him to face suffering via turning himself in and serving his sentence. But he's in part only able to do this (and eventually to truly repent) because of love. His family and Sonya love him. Svidrigailov wants Dunya to be his Sonya; however, there are some key differences. Raskolnikov empathizes with Sonya, but Svidrigailov doesn't empathize with Dunya very much.

I'd say he desperately wants to use Dunya to feel better about himself. And he wants her to love him, because he's incredibly lonely and lost. When she finally convinces him that she never, ever will, he then donates all his money to Sonya (whom he sees as Raksolnikov's Dunya, and Dostoyevsky makes this especially clear when Svidrigailov literally eavesdrops on Sonya and Raskolnikov's conversations) and commits suicide.

Yet the problem is that Svidrigailov doesn't see Dunya in the same human sense that Raskolnikov sees Sonya--he sees her as a Good Girl who can save him from himself, but doesn't actually try to explore what makes her "good," or what she wants out of life. Even his chasing Dunya down comes after he betrayed her by propositioning her while he was her married employer, then allowed her to be badmouthed and fired which could have destroyed her entire life, and then he made amends... yet murdered his wife to chase after Dunya. That would be like Raskolnikov murdering Katarina Ivanovna and Sonya's siblings to chase after her. It kinda provokes a different response.

Svidrigailov wants to be saved from himself. But the way to save himself is to look at himself at his core, to kiss the earth and confess, as Sonya tells Raskolnikov to do. Raskolnikov's motives are also very interior, and they have always been so--he wanted to prove himself an ubermensch of sorts, but failed. Svidrigailov's seem to be more about avoiding himself, yet still, as with Raskolnikov, the truth of who they are still seeps out despite attempts to avoid it.

You can only run so far from yourself.

Svidrigailov is a tragic character, and if you were drawn to him, he's also a prototype for other characters in Dostoyevsky's works: Rogozhin from The Idiot, and most obviously, Stavrogin from Demons--in which essentially the entire book revolves around the enigma that is Stavrogin.

#ask hamliet#crime and punishment#svidrigailov#rodion romanovich raskolnikov#sonya marmeladova#dunya raskolnikova#fyodor dostoevsky

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ivan infodump

OK SO i posted my little guy Ivan (big deer guy) and as i mentioned in his post, hes a mix of different characters i've like found interesting and that had interesting concepts that i wanted to explore in a character so yeah I decided to make ivan!

Ivan's like part of this universe im a part of w some buddies and he's like a werecreature (i cant rlly go super in depth w the lore here because i dont rlly know it that well LHDFCBDVLKHB) he was turned into one like after some stuff happened in his life that left him broke so he needed money to like get back on his feet and doing that (essentially making himself a test subject for this thing some scientists were doing) was the only way he could. Heres where the first theme i wanted to explore comes in, Guilt and Debt.

If anyone's read crime and punishment, the main character Raskolnikov essentially k1lls his crusty musty landlady so he doesnt have to owe her his rent anymore which imo, slay, but at the same time he is riddled with this immense guilt and like questioning himself as to wether or not committing a crime and a deadly sin (because hes also catholic so another LAYER of guilt added)

Raskolikov gets sent to prision to like seve his sentence but most of the book is like him debating with himself wether or not what he did was right, because he mrd3red someone that was a pest both to him and everyone else who owed rent to her, and she was a busive and mean so like thats someon no one would miss because she was bad so he's good for killing her, it was for the greater good, but at the same time in the eyes of the law Raskolnikov is a criminal, as well as in the eyes of religion because he murdered someone and thats an unforgivable act and hes supposed to go to hell for that.

In Ivan's case, his guilt lies in the fact that he was essentially the reason him a nd his family's business went into banktrupcy, if he was never born he woudln't have caused much trouble to his parents. He's the son of a violin maker, meaning business is not as big as theyd wish it to be especially as violins are expensive as shit because theyre handmade works of art that only few know the trade of making them and stuff. Ivan obviously inherited the knowledge from his father, helped him in the shop and helped to provide for his own family even as a child, but he still carries that guilt of being the reason niether one of his parents could fulfill any of the desires they had due to him being just "a burden" in his tiny little head.

In the debt aspect, he is quite literally indebted, left with the previous unpaid bills and unfinished projects his father left after he passed, and left with a bunch of customersn his father still owed things to like money, instruments and materials. To Ivan, thats the way he's repaying the hardships he made his parents go through. the family burdens are passed down generation by generation as well, because many of most of the monetary debts came from people of the past that made those bad desicions and left their descendants to deal with them. Ivan is determined to fulfill these depts, at all costs, and eventually that costs him his humanity.

NOW ONTO HANNIBAL!

I mostly wanted to do the c@nn1balsm as a metaphor for all consuming, obsessive love with Ivan , especially the love for his craft (because in the end he loves what he's doing, hes a passionate violin maker) but literally in the way that he loves as well. He isnt that bad looking, at least according to him (in my head his face claim is jacob elordi specifically in saltburn and like post euphoria and the kissing booth) but he does feel like he's hard to love because of all the guilt hes carrying for shit he didnt even do (like be incredibly indebted to the state). hes super inexperienced in love, has only had one long lasting relationship, and that relationship is one that consumed him so much that he couldnt see himself living apart from that person he loved after they broke up. Ivan has an anxious attachment style, always has and hes like a kitten with separation anxiety, he will wail and scream until he gets back to that person he feels safe with even if it means that he's actively pushing them away because of how clingy he is.

all that to say that he ate his ex boyfriend because if he couldnt be with ivan then no one could have him

So yeah that is like almost all of Ivan's story! i love him dearly and rlly want to expand more on him in the future!

#art#original character#oc#artist on tumblr#character#my characters#character concept#hannibal#crime and punishment#analysis#infodump#oc story#oc stuff#original characters

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Of Lice and Men: Raskolnikov’s Schism Between Humanity and the Extraordinary

“But why must they love me so much if I don’t deserve it? Oh, if only I’d been on my own and no one had loved me and I’d never loved anyone! None of this would have happened!”

posting this for the crime and punishment stans 😍😩 it was a close-reading assignment, where we took a passage and analyzed it in the broader context of the book. full essay under the cut!

Russian readers of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment will immediately note the heavy-handed symbolism in the main character’s name. Raskol (раскол), meaning “schism,” reflects the two sides of Raskolnikov: his intellectualizing alter-ego and his own heart. Directly tied to this inner schism is Raskolnikov’s ideology of the “extraordinary,” which drives his actions throughout the novel. While it is most obviously related to Raskolnikov’s murders and his debatable sense of guilt, the “extraordinary” argument also demonstrates to the reader the schism in Raskolnikov’s sense of self: his concept of what defines a ‘human being’ and whether or not he falls into that category. In fact, it is his staunch determination to become a human being that causes him to attempt to break all bonds and emotional attachments.

First, it is necessary to understand exactly what Raskolnikov’s “theory of the extraordinary” is. The initial instance where it comes up is during Raskolnikov and Porfiry’s intellectual battle of wits, wherein a horrified Razumikhin hears Raskolnikov explain that “people, by a law of nature, are divided in general into two categories: the lower one (the ordinary) … and actual people, i.e., those with the gift or the talent to utter … a new word” (242). This is the first time the reader sees that Raskolnikov distinguishes between “actual people” and the “lower,” the “ordinary.” Further, in his article “On Crime,” Raskolnikov “hints” (in his own words) that “an ‘extraordinary’ person has the right… not an official right, that is, but a personal one, to permit his conscience to step over… certain obstacles” (241). Raskolnikov gives the examples of Lycurgus, Solon, Muhammad, and Napoleon: all “criminals to a man” only for violating “the ancient law held sacred by society” (241). So in summary, an “extraordinary” is a person who is permitted to supersede their own conscience to affect some sort of greatness. Often, the extraordinary goes against societal values—the status quo—to do so.

Since Raskolnikov’s conception of an “actual” human is connected to his theory of the extraordinary, he enters a cycle of seeking and rejecting human contact throughout the book as he grapples with the realization that he himself is not an extraordinary. Early on, it is established that Raskolnikov unconsciously seeks out human connection: in Part II, after wandering around St. Petersburg in a fevered, delirious haze the day after the murders, Raskolnikov finds himself at Razumikhin’s apartment (104). After chiding himself for winding up there, Raskolnikov ends up following through (“What’s to stop me…?”) and goes to see his friend. However, after Razumikhin expresses concern at his sickly state, Raskolnikov instantly regrets the visit: “In a flash, he has seen for himself that the very last thing he felt like doing … was to come face to face with anyone at all in the whole world” (105). He even “all but choked with self-loathing the second he crossed Razumikhin’s threshold” (105), which implies that Raskolnikov viewed the act of seeking out a friend as a weakness. Before the reader even knows the extent to which Raskolnikov has intellectualized himself away from culpability, they see early on this schism between what his subconsciousness wants to do and what he tells himself he should be feeling.

Despite the fact that he hates himself for it, Raskolnikov ends up seeking human connection again very soon after this—but from strangers this time, so as to not have to confront the concern of a friend. He goes on a walk to Haymarket and starts conversation with two strangers he comes across, who look upon him and his sickly appearance with “wild astonishment” and disdain, respectfully (146). Following these failed attempts, Raskolnikov sees a throng of people across the street and has “a strange urge to talk to everyone he met” (146). His desperation for emotional connection is obvious here, but as it grows more intense throughout the novel, so do Raskolnikov’s attempts to suppress it—which is in tandem with his orbiting closer and closer to Sonya.

Even as he finds himself incapable of staying away from Sonya and incapable of holding himself back from confessing to her, due to his desire to be an independent entity unbothered by emotional attachment, Raskolnikov revolts against himself even in the last instant before his confession. After he tells Sonya that, despite his intentions to do the opposite, he ended up coming to her asking for forgiveness, he feels “a strange, unexpected sensation of almost caustic hatred” towards her. Surprised by this feeling, he lifts his gaze to Sonya, only to see that “there was love” in her expression. His hatred vanishes “like a phantom,” and he realizes that “he’d got it wrong; mistaken one feeling for another” (383). Echoing the scene in Razumikhin’s apartment, Raskolnikov, when confronted by the concern of the people who love him, labels this cornered, overwhelmed feeling as “hatred,” an emotion that pushes others away instead of inviting them closer. However, the astute self-awareness that he is cursed with overtakes his initial pushback.

Indeed, Raskolnikov’s awareness that he is not an extraordinary sets the framework for his own internal crisis, as he cannot himself satisfy the definition of a true human that he came up with. When he confesses to Sonya, he goes on about how he knew that he was not an extraordinary—“…that if I asked, ‘Is a human being a louse?’, then man was certainly no louse for me, only for someone to whom the question never occurs…” (393). Going into the murder having already realized this, he then tells her, “I just killed. I killed for myself, for myself alone” (393). Raskolnikov is desperately willing himself to be an independent force in the world, untethered by social law and rational thought. He “needed to find out … whether [he] was a louse, like everyone else, or a human being” (393). He once again confirms that it is the “extraordinaries” whom he considers to be truly human; “everyone else” is a louse and does not qualify. By this definition, in order to be a completely independent extraordinary, one must reject all human attachment—in fact, human attachment must never have been valued by them in the first place. Thus Raskolnikov’s frustration: “If only I’d been on my own and no one had loved me and I’d never loved anyone!” He wishes he could have been on his own, he wishes no one had loved him, and more than any of that, he wishes he had the ability to never have loved anyone, for this would have vaulted him to the level of extraordinary.

Such cognizance applies to Raskolnikov’s moral conscience, also, when he asks himself, “Why must they love me so much if I don’t deserve it?” He’s already admitted that an extraordinary would not have been concerned with whether they had the right to kill or not (393), so the same logic applies to the question of whether or not they would deserve love. For an extraordinary, the thought would never have even crossed their mind—they don’t need love. In fact, according to Raskolnikov’s understanding of an extraordinary, they must rebuff love from others in order to be a true human being. Raskolnikov, on the other hand, is tearing himself up about the fact that he does not deserve the love of his family and friends, thereby proving once more that he is not an extraordinary.

If Raskolnikov had been an extraordinary, then “none of this would have happened”; were he completely able to separate himself as a step above everyone else, then he would not have to turn himself in. In the following paragraph, he goes on about how the experience of being incarcerated will do nothing to humble him (489), thereby proving that at this point, the reason he will go to the police bureau is not a desire to repent for the murders. He’s furious that his family and friends care so much about him that they urge him to turn himself in, he’s furious that he will lose them all if he doesn’t, and most of all, he’s furious that he won’t be able to take that: complete isolation from the people who love him. So, he is trapped—not only by Porfiry, but by his own humanness, which he has tried to bury for the entire novel. In submitting to his loved ones’ hope that he will repent and turning himself in, he will officially be—by his own definition—no longer human, only a louse. In the end, though, as Raskolnikov accepts that others care for him, and that he cares that they care, he actually confirms his humanity.

The reason for which Raskolnikov is drawn to Sonya exemplifies the root of his internal conflict: Sonya is the least extraordinary person in his life and therefore the most “louse”-like—or, the most human. Dunya articulates this in expressing relief that her brother “sought out a human being [in Sonya] when a human being was what he needed” (489). While Raskolnikov would consider Sonya “a louse,” the narrator calls her a “human being,” negating the ideology that Raskolnikov has attempted to adhere to throughout the novel. Therefore, Raskolnikov’s circling around Sonya to the end of the novel—even into the epilogue, where he spurns her in prison but then finds himself weeping at her feet (516)—is the epitome of his pattern of embracing and resisting human connection. Raskolnikov’s theory of the extraordinary, and his attempts to resist being a louse, are an overlooked link to the internal schism that compels all of his actions.

#crime and punishment#crime&punishment#dostoevsky#fyodor dostoevsky#dostoyevsky#classic lit#russian lit#dark academia#lol#if you think i'm projecting about sasuke uchiha in this a little bit it's because i am! <3#i speak

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crime and Punishment - Soukoku oneshot

Summary:

A demon once whispered to him of crime and punishment. He hadn’t paid it much mind – how trusted can a demon be?

His crime, among others, was betrayal.

The only aspect of the crime he left overlooked turned out to be the most crucial one – the punishment.

And the demon stays amused by the most pathetic Raskolnikov in existence – Dazai Osamu.

or

The author being an absolute nerd for Dostoyevsky and overanalyzing Soukoku’s relationship. Enjoy Dazai’s late-night thoughts!

TW: death, implied suicide

Author’s note:

I’m taking a break from my usual writing (which I’m super insecure about), so I’m writing this little fic because I hope you will be kind to me. Also, I just needed some comfort and BSD is my go-to place for that.

There’s a couple of references scattered across the fic: the obvious one about Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, as well as The Brother Karamazov and The House of the Dead. Yes, I’m aware I’m a huge nerd.

I actually got really carried away and I wrote 2 more chapters which I’ll post on AO3. Of course, this chapter will be up there too, I’ll put a link down below, so please give feedback. :D

AO3: https://archiveofourown.org/works/30342828

Enjoy!!

A demon once whispered to him of crime and punishment. He hadn’t paid it much mind – how trusted can a demon be?

Dazai Osamu’s crime, among others, was betrayal. He betrayed the miserable life he had led in Port Mafia, the life that had devastated him on the days he remembered he had heart under that cold, colorless ribcage of his. This life, if one may even call it that, deprived Dazai of a childhood, of innocence, of cleanliness: his hands stained crimson red and his thoughts painted pitch black. Would letting go wash away those dark colors, reveal the truth underneath, which was unknown to him? He did not know, but something had to change.

And so he escaped, with the night cradling him and the smoke of a burning car covering his treacherous silhouette. He had fled the winter of his life, days of bloodshed and sin out of sight and out of mind, looking forward to a promisingly bright spring. Betrayal is an ugly thing, but he had never cared much for looks.

The only aspect of his crime he left overlooked turned out to be the most crucial one – the punishment. Never had he dreamed he would feel guilty.

What am I really even guilty of? Wanting to see the light? Wanting to do good for once in this wretched life I lead? The days I spent swimming in the dark waters of despair deserved to see the end. Am I a monster for wanting happiness?

Hard as he tried to reason with his guilty consciousness, it never left him. It just kept gnawing at his thoughts, making him remember what, nay, whom he tried to forget.

The red-haired calamity.

The manipulator of gravity.

To Dazai, the giver of life.

Nakahara Chuuya.

At the time, Dazai could’ve never fathomed the concept of missing the redhead. Sure, Chuuya was important to him – as much as a person who knew everything about you could be. The two knew each other from the tip of the head to the end of the toes.

He could never not be important. Such noise is rarely ignored, Dazai mused jokingly.

Chuuya was what brought him life. The constant cheating, stealing and killing tramples the soul until you cannot make anything of what’s left. It’s what makes Dazai long for death – he’s seen the depths of this cursed city that squeezed his heart to the point he wanted to throw it away. However, Chuuya – just saying his name made Dazai feel warm – he saw it too. He felt it the same way Dazai did. He might act harsh with all his stomping, yelling, and destroying, but underneath all that is a gentle, nurturing nature that he hides. It’s a detriment in his line of work. Having someone understand meant a lot to Dazai. Maybe their partnership was even built on this silent understanding, among other things.

However, Chuuya was not nice. Don’t ever mistake Chuuya’s sensitivity with kindness. Sugar and spice was not to be in the same sentence as his name. He has always been… rough. Sometimes it served as a wake-up call to Dazai. It helped put things into perspective, but it also helped put things into bad perspective. Not a single morning did these two share without a fight – verbal or physical. Dazai didn’t mind it much at first. After all, teasing Chuuya did work like a drug for him. With time, however, the blade of their words never became dull. It only sharpened. Words like poison flung around the apartment, sentences like spider-webs sitting in hidden corners of the bedroom. Love – they never dared call it that, but, oh, what a burning love it was – love, the most sacred of all emotions, was a chore until it became a war. Eventually, Dazai couldn’t find his peace even in the arms of a lover.

So, his craftiness started turning wheels again and – he escaped. Not a word in the evening, not a trace in the morning, only confusion and hurt spelled over Chuuya’s heart.

Dazai knew it was cruel. He never felt right about it. He loved Chuuya, after all, so the best thing to do, he concluded, was to forget.

The demon laughs. Punishment has been passed.

Presently, Dazai Osamu spends his night awake, staring at the dirty ceiling of his room, as the most pitiful of the world’s Raskolnikovs.

Why can’t he seem to forget a man he once loved, a man he soon grew to hate, a man he betrayed in order to find happiness? What twisted force of nature is dragging his thoughts back to the time he was at his lowest? Why is it that now, when all hope of reunion between the lovers is lost, he finds himself longing for the infamous Port Mafia executive Nakahara Chuuya? Why did the ashes find their way back into a flame after he committed the worst of all sins – betrayal of trust and love?

The demon chuckles once again and in a sing-songy voice he says, I told you, Dazai-kun. To love thy neighbor is impossible. The man himself is the ugliest of all God’s creations – how could anyone love such a creature up close? Even the Father won’t cast a glance at him. It takes distance, Dazai-kun, and you’re not exempt from this rule of human nature.

It is irksome, yes, how right the demon seems to be. It is certainly irksome, Dazai feels, as the demon’s words carve into the left chamber of his stone cold heart. What even was it that made Dazai hate Chuuya? Hate Chuuya… it used to seem so impossible and yet, along with Odasaku’s death, it drove him to plan and execute a high-scale betrayal of the entire Port Mafia.

It would take years before Dazai could understand the intricacies of his past with Chuuya at Port Mafia. What mattered now – truly, the only real thing in this world – was the fact that he actually loved Nakahara Chuuya.

Oh. There. He thought of it. For some reason, he didn’t want to think of anything else but that. It wasn’t scary, as he thought it’d be, all those years ago. He finally broke the lock in his lungs and there it was: all that air he never let himself breathe. What was it about that mere word that made two Port Mafia executives shy around it, avoid it like the authorities, dance around it as if it was bonfire in the festival night? Why had they never let the simple four-letter word into their little sanctuary when it so obviously belonged with them? The fear he once felt seemed foolish to him now.

I guess we do learn as long as we live, he whispers in the dark room to no one in particular.

He felt a rush trying to sweep him up, make him stand. However, where would he go? To Chuuya? As if. He hurt Chuuya in unspeakable ways even during the time they spent together. He has no right to show up at his doorstep or in his life. Ever again.

Even if he did, how would that end? They squeezed each other’s hearts dry and called it love. Every day felt like torture, but they swore it was sweet. Why, why, why did they cause so much pain? Was it truly the only method to make them feel alive in the house of the dead? Did the right answer slip between their fingers at some point?

The question Dazai had been stuck on was, Is there any way he could forgive me? If, once in the future, I looked him in the eye and told him the truth – would there be salvation pouring from his lips? Or would he rightfully convict me for my crime?

Thus, Dazai fell into slumber, like every other evening for the past four years. The bed will never feel comfortable to him because it always seems to be missing something, but Dazai will keep denying it. His little room doesn’t even look like a home, but Dazai will tell you that he just can’t be bothered to unpack and decorate. His heart, cold like a Russian blizzard, has not known warmth in a while, but he will tell you it’s incapable to do so.

Those are the only three lies Dazai Osamu tells people and himself – until the night comes again and unlocks a little door in his brain.

#bungou stray dogs#soukoku#double black#twin dark#dazai#dazai osamu#bungou stray dogs dazai#dark era dazai#mafia dazai#nakahara#bsd chuuya#nakahara chuuya#bungou stray dogs chuuya#dazai x chuuya#port mafia#armed detective agency#anime#manga#bungou stray dogs beast#fyodor#fyodor dostoyevsky bsd#fyodor dostoyevsky#crime and punishment#dazai osamu x nakahara chuuya

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

10. Fyodor Dostoevsky. Crime and punishment

Hello guys!! I’m kiiiind of shaking in my chair right now. I’m beyond excited to sit down and write something in here. I got reaaally wound up in school work, and other things like that... You know, i won’t even try to excuse myself. I’m just hella lazy. But here I am, ready to write a dope review of a dope book, which my hands are just itching to rant about. I would also like to give a shout out to my dear friend, whose name i probably won’t say. She just randomly texted me to tell me how dope this blog is, and I got really inspired to keep it going, ya kno? So, here we go!!!! oh, and also, happy new year guys. I love you all to shreds!!

(warning - spoilers. obviously)

So, i really don’t want to start spilling my opinion all over the place right at the start, so I’ll try to contain myself. Oh boy, is this going to be hard. However things may be, I believe we should start with a bit of plot to get this whole thing going.

If you are not familiar with Eastern European history or culture, you might be surprised by the authors name. Let me start off by saying, that Fyodor Dostoevsky is Russian. He is one of the most famous (if not the most) authors in Russian history. He is also an incredible philosopher, which is clearly visible in the book we’re reviewing today, but we’ll get to that a bit later on. I think by now it should be pretty obvious, that the action in the book is based in Russia. Our main character, Rodion Raskolnikov, is a completely broke university drop out. He seems.. Fairly normal for the first ~100 pages of the book. Just a dude, living his reaally sad life (completed with dark and dull descriptions of the town he’s living in, Peterborough), contemplating everything that comes up in his mind. If i were asked, I’d say he might even be depressed. But yeah. As the books title suggests, there’s a crime. and, please, for the love of god, if you’re even the slightest bit interested in reading the book, do NOT spoil this for yourself, just go read the damned book. You have my word that you will not regret it.

For those who stayed - Raskolnikov kills and elderly lady, which is like the owner of the house he lives in. This was not such a surprise for me, because, at the very start of the book, our protagonist goes up to the woman’s flat to pay his rent, and his whole thought process is written down. The way he analyses everything in her home, how she has a small box of jewelry, which, he thinks, probably contains a fortune. So, like... You know. Crime? Old, rich lady? poor student? It was not that hard to add the three together. When he actually does it (which he does quite brutally. Rodion used a frickin’ axe, and he killed not only the old lady, but also another young woman which would have caught him), he doesn’t even steal that much. He instantly starts to panic, grabs a couple of things and runs the hell out of there. From this spot forward, our main character goes more and more nuts with every single page. He is constantly living in tremendous fear, soul-wrenching panic and all that good stuff. He doesn’t even use the things he stole from the apartment to save himself from poverty - Rodion buries everything under a rock. Yeah, you read that right. A rock. The criminal’s anxiety drives him so mad, he gets physically sick even. So the other 400 pages of the book are mainly about the thought process of a murderer. Oh, not to mention the incredible jaw-dropping plot twists and a very unusual and refreshing love story. I’m not even considering spoiling the ending, because, dude, no. I couldn’t forgive myself if i ever ruined it to someone, because i genuinely want you guys to have the same experience as I did. I believe that’s that for the plot, let’s move over to my opinion (that sounds so frickin’ narcissistic. I’m so sorry lmao).

I’d like to start off by saying that I haven’t had a favourite book in ages. But, guess what? Druuuumroooooll pleaaaaaaase: this one is!!!! It is so good it hurts. I want this book to turn into a human, and I want that human to be my overly - philosophical yet tremendously intelligent best friend. First of all, Dostoevsky’s writing style.... oh boy. I don’t know why, it clinged to me like I cling to my bed on Monday mornings. When he starts a new topic or anything of that sort, he writes about a completely unrelated topic, and then somehow manages to relate it to the current events in the book, which he needs to write about?? what even is this this sorcery. Like, for example, he would start writing about, lets say, shoes, and boom, somehow he’s jumped over to how all people are bad or some shit like that. And you don’t even feel the damned transition. It’s just so smooth and masterful. I’m convinced he does this in the majority of his books, because right now I’m reading “Idiot”, and it’s the exact same in there as well (tell me if any of u guys want a review of that!! I’d be glad to write about the book once I finish it).

You can really tell this guy is a philosopher. I’m not joking when i say this, but there were a couple of spots in the book, which i read about five times, because they blew my mind. Never ever has this happened to me before, where I’m reading something and I get shivers. Like, actual shivers. The monologues about human nature, and why the protagonist actually doesn’t blame himself for the crime, were eye-opening. So amazing.

Also, the plot twists??? They were mainly connected to other characters (which there were plenty of in the book, so beware of that), and yet so perfectly braided into the story, and when they hit you literally out of the blue, it’s just mind-boggling.

This book, to me, is like staring at the world though the eyes of a murderer. When he explains his reasoning for the crime, you even start to feel empathy for him, which just shows how there is never one side to a story. This book seriously taught me how there is never only white or black, there is also gray.

I believe many people are scared of the length. The version I read had ~550 pages, so it’s pretty much that, give or take a few pages. I was really intimidated by the length. I thought that this is one of the og classics, it will be tough, and maybe even boring, and the length really just escalates all those thoughts. I do have to say, the first ~100 pages were hard, man. You have to get used to Dostoevsky’s specific writing mannerisms, monologues that take up to 4 pages and the sometimes overwhelming amount of additional characters with really difficult names, if I do say so myself. BUT. It is so worth it once you push through. Really, take my word as is, I have read a lot of books. This one is definitely worth reading.

If I caught your attention even the slightest bit, please don’t hesitate. I can’t stress enough how amazing this literature masterpiece is.

10\10

I hope you enjoyed your stay in the introvert book club!

#books#Book Lover#book nerd#must read#literature#literature classic#classic#book club#introvert#introvert book club#reading#dostoevsky#crime#crime and punishment#book#book worm

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

This translation is very British, so I find myself translating the translation a lot, and find it a little difficult to see through the adaptation. The normal process of reading is often a series of failed conjurings. Because the tone is not always immediately clear. And it might not be the authors fault at all, there’s only so much we can be aware of or remember at any given time. Sometimes a writer needs to teach you how to see the scene.

Especially with Dostoyevsky, who is writing to you about real sensations, real states, the most exotic corners of the human experience, but likely one’s you’ve experienced, even if just in nightmares. So, being set so long ago, and so far away, I often wonder about all these little foreign objects Dostoyevsky might be referring to whose psychic charge might be lost on me. Or situations I may have experienced as a child, like waking up in the middle of the night in my dark room with only the light coming in through a cracked door, and the sound of The Eagles blasting on the stereo, the vague, ominous sounds of my drunk parents partying somewhere in the house. Or the time we were at my father’s friends’ house and they packed me and my brother and his friend’s girlfriends kids in the closet, and turned out all the lights because the police were passing by. These ominous memories. There’s really no translation in time to those circumstances to 19th century Russia, but the sensations, drunk ominous adults, like the ones in Raskolnikov’s lucid nightmare about the little horse (Raskolnikov’s Turin horse) must be similar in some ways.

So you might read a passage and not catch the magic the first time. Maybe it recurs to you thinking about it later, suddenly you realize the secret music you didn’t notice the first time.

Obviously I identify with our monologuist, Raskolnikov. He pursues a theory and then radically doubts himself, a true dialectician. I shall pursue the greatest good. Actually, fuck it. haha Dostoyevsky is very aware of this sense of just praying to be freed of this torment, these emotions and mental labyrinths we enslave ourselves to, and indulge and ruin ourselves and abuse other people with, and that moment of gentle spiritual emancipation, and the heartbreak of how stupidly fragile it is. NEVER DONE FUCKING UP t-shirt is on.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: Crime and Punishment, by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Crime and Punishment was published in 1866, and it is the second of five novels that Fyodor Dostoyevsky published after he returned from forced labor in Siberia, which are considered his most important works. The story follows Rodyon Raskolnikov, who is a university drop-out, and is struggling financially (all too relatable for so many young people these days!). Early on in the novel, he decides to murder a wealthy pawn broker—ostensibly to take her money—and the rest of the story follows the psychological effect of that crime on him and his attempts to avoid being found out by the police.

Like all of Dostoyevsky’s novels, this one is lengthy, with a large cast of characters, and a complicated plot. We meet Raskolnikov’s mother, Pulcheria, and his selfless sister, Dunya. We meet Pyotr Petrovich Luzhin, the wealthy man Dunya wants to marry, but whom Raskolnikov doesn’t want her to marry. We meet a man named Marmeladov, with whom Raskolnikov bonds briefly at the beginning of the novel, and his family: Katerina, his wife, and Sonya, his daughter. Finally, we meet Porfiry Petrovich, the police officer investigating the murder of the pawn broker, and Svidrigailov, a man for whom Dunya had previously worked, who comes seeking to get her to marry him.

The main moral dilemma that occupies Dostoyevsky here has to do with an idea that Raskolnikov writes about in an article he had published before the events of the novel. In it, he argued that there are two types of people. There are the simple, everyday people who must follow the law, and will probably not do anything remarkable with their lives and will be forgotten after they die. Then there are the “great men,” who are above the law and will change the world and better humanity, and should be allowed to do anything they can to further those goals—including killing innocents. The way he put it at one point that stuck with me is that, if there were a scientist who needed to kill several people in order to run some experiment the results of which would significantly improve the lives of other people, then that scientist, not only should be allowed to kill those people, but is morally obligated to kill those people.

Raskolnikov himself wants to believe that he can be ruthless in what he sees as a horrible act that will, in the end, improve society. He does everything he can to justify his crime, but even if intellectually he can convince himself that his crime was justified, he clearly can’t deal with it emotionally. Even if he doesn’t know it, we see the effects of his repressed remorse on his physical and mental health, and we hear from other characters that his character also changes. He becomes irritable and says uncharacteristically nasty things to people he cares about. In the end, he must figure out whether he will destroy himself to become one of these “great men” or accept his true nature.

Other characters show varying motivations for their morally dubious actions; some to support their family, others to get someone they’re lusting after, and still others for no discernable reason save to spite someone whom they dislike. We also see the different ways in which crime is punished. Some, in particular the wealthy characters, don’t face much of any consequences. Others face consequences for crimes they didn’t commit, as a man who is falsely accused of the murder of the pawn broker experiences. Yet others suffer for no fault of their own; some of them may have made mistakes or poor decisions in their lives, but are also subject to consequences beyond their control. The family of Marmeladov, in particular, show the tragedy that can befall many people as a result of both bad luck and their past decisions. It is notable that the Marmeladovs, a poor family, suffer the most out of the characters in this novel, which is contrasted with Pyotr Petrovich and Svidrigailov, who both do terrible things and face few consequences, thus providing not-so-subtle commentary on the privilege afforded those with money.

Another theme of this novel is the power of compassion. One minor character expounds an idea he has about compassion. This character claims that showing kindness to individual people is pointless, because it will not solve the root source of people’s ills—that is, the unfairness of society. He claims that one should do what one can to improve the justice of society so that everyone will be better off. If one does that, then they don’t have to worry about being kind to everyday people. Clearly, since Raskolnikov’s crime is done in the name of improving society in some way (he claims), this is meant to show the possible danger of this idea. We also see many instances of kindness throughout the novel where one person helps another unconditionally with no hope of return, and see the power that compassion can have in people’s lives. Even Raskolnikov, as he claims to be above compassion or pity, helps out the Marmeladov family at one point. That being said, Dostoyevsky draws our attention repeatedly to the squalor, poverty, and homelessness that were rampant in Russia at the time. So I certainly don’t think he was against social justice—far from it—I think he merely wanted us to think carefully about our methods for achieving it, and to keep our sense of compassion along the way.

Overall, what Dostoyevsky seems to be showing in this novel is that humanity needs some objective basis from which to judge what’s right and what’s wrong, because “everything is permitted” isn’t a sustainable worldview. It runs the risk of turning us all into self-interested monsters, a couple of whom we meet in this novel (ditto, the two wealthy men who are free of material consequences for their actions). If we have no higher values to answer to, then it becomes ever more likely that we’ll become materialistic and self-interested. Dostoyevsky’s response, both in his own life and in this novel, is to turn to religion, but I don’t think it has to be our answer, if we choose to be secular. Even Nietzsche, a hardcore atheist himself, believed that complete nihilism would lead to disaster for humanity. This novel, then, is interesting because it shows the negative effects of atrocities on both the victims and the perpetrators of those atrocities.

I will admit that I did find myself wondering part way through the novel why this moral issue was relevant to my life. Obviously, I’m never going to go out and murder a woman with an axe. But after thinking about it, I realized that most of the worst atrocities of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries were committed with some ostensible higher purpose in mind. Whether it’s the Holocaust, where the Nazis were creating a paradise for the German people at the expense of millions of lives; or communism, where people like Stalin were supposedly trying to bring about a proletarian utopia; or the religious extremists now who kill hundreds of people at a time in terrorist attacks for the sake of a divine mission, most dictators, terrorists, murderers, and criminals in modern times have found one way or another of justifying their actions. Thus, I definitely think this is a relevant issue for us to discuss nowadays.

Overall, I loved this novel. It was more gripping than The Brothers Karamazov—in fact, I’d go so far as to say that it’s a page-turner, which is rare for a classic, in my experience—and I loved its heavy themes. I was moved by the bitter-sweet ending, which I won’t forget anytime soon. I liked the translation I read, which was done by Richard Peaver and Larissa Volokhonsky for Vintage Classics. They made it sound a lot like an English language novel would’ve been written at the time, which might not be everyone’s favorite, but definitely made it sound authentic.

So I highly recommend this book. If anyone’s read it and has any thoughts, I’d love to hear!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Existential asks

Camus : Do you smoke a lot? nope

Sisyphus : Do you feel like what you are doing has a purpose? I would like it to have a meaningful purpose one day. I applied for this uni course so I could learn Biology but I don’t get to pick my major till the second semester. So yeah, at the moment it feels purposeless but I know that I’ll be doing what I want to do soon enough. I just really hope studying Biology is not like this first semester because all it’s done is made me sad and anxious and stressed and thats not me, thats never been me, I hate it.

the Stranger : Are you more of an objective or subjective person? I’m definitely more of a subjective person

Caligula : Is freedom your thing? It absolutely is. I’m constantly searching for freedom away from routine, I hate routine, I love doing my own thing and knowing I have time to do my own thing. Uni has somewhat taken that away from me but I’m still adapting.

Sartre : With whom would you like to spend your life with? Wizard Howl. I mean first of all how great would life be, like, have you seen the movie just uggh mesmerized and plus hes the man of my dreams: a mysterious wizard with gorgeous hair, a bad reputation but he secretly has a soft center AHHH

Nausea : Does life feel repetitive at times? I don’t mind repetitiveness so long as it’s of something I enjoy.

Antoine Roquentin : How bored are you? Everything can get boring at times, but right now I’m watching The Shawshank Redemption

Being and Nothing : Are you a responsible person? I think I’m responsible

No Exit : Do you like other people? I like most people I just don’t like when they talk to me. But then there are really special people that talk to me and I’m like oh you’re cool.

Simone de Beauvoir : Do you feel like you’re leading a life according to your conscience? I study Biology soooo if that doesn’t say enough. Also I’m not one of those people who follow ridiculous social standards.

Ethics of Ambiguity : Can you be sure about your morals? I don’t think you can be sure about anyone’s morals, I mean, who’s to say their morals are better than someone elses. Who’s to say whats right or wrong.

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky : Ever had a near miss with something extremely dangerous? Yes, my parents were taking the asbestos off the back of the house and I went down to where they were working (they were wearing masks obviously).

Notes From the Underground : Do you sometimes fly into schadenfreude and back? Not since highschool

The Brothers Karamazov : Do you set your own rules? Not really I’m not that bold. If you can’t find fun within the rules then maybe you’re just not creative enough.

Crime and Punishment : Will you try to justify yourself, even if what you did was evil? I try to justify myself to myself not really to anyone else. I’ll lay awake in bed and recite explanations for myself.

Raskolnikov : Are you more of a law-abider or a vigilante? Law-abider

Martin Heidegger : How are you with technology? I’m actually not that bad.

Being and Time : Favorite pastime? My favourite pass time is probably doing nothing while drinking tea. I just really enjoy sitting in the sun for ages. I like doing really slow, quiet things like sketching and stitching and hanging out washing.

Søren Kierkegaard : Are you religious? No i’m not but I do appreciate religion.

Johannes de Silentio : How far would you go for a person you love? I honestly don’t know, I don’t even know what love is yet, I suppose I’ll know when I do

Friedrich Nietzsche : Do you stand out from the crowd? No siree

Thus Spoke Zarathustra : Do people listen to you? I try to sound interesting when I talk but maybe I’m only interesting to myself.

Human, All Too Human : Ever dissociate from your surroundings? I often dissociate from places I don’t particularly want to be but on the contrary

Schopenhauer as an Educator : Who was your fave teacher? My Biology teacher was by far my favourite because he was so admirable in the sense that he was like a shy quirky 7 year old boy in a mans body and that he was proud of the smallest things and was giddy about biology jokes and otters and pictures of babys, including his own.

Arthur Schopenhauer : Are you obsessed with aesthetics and beauty? I am, its very addictive. I’m currently in love with pale skin, rosey lips and cheeks and long lashes what a look and the FRECKLES oh boy I love it

The World as Will and Representation : How do you deal with your suffering? somewhere in the back of my mind, somewhere I can’t get to, truth is I don’t really deal with my suffering someone give me some pointers please

1 note

·

View note

Note

Sleepover Saturday💐: What do you think about Raskólnikov (crime and punishment) in the philosophical and ethical way.

My friend, I love you. I’m always itching to talk about Rodya since I love him to death. I actually wrote a full on essay about the guy for school last year, so hopefully I kinda know my stuff? The rest is under the cut so people can avoid spoilers.

First of all, there’s a logic to utilitarianism, one that I can’t deny. In the trolley problem, I’d kill one person to save multiple others with little hesitation. So I understand where Raskolnikov’s logic behind killing the pawnbroker comes from in that sense. Though I feel like utilitarianism involving death is more of something you use in urgency, like in the trolley problem when people are about to die. In his case, nobody was in imminent danger, so I can’t see it as justified really.

There’s also the fact that later he himself acknowledges that he may have committed the murder just to prove that he was “an extraordinary man” who could break the law with no consequence on his conscience. Perhaps he already had the idea in his subconscious to kill or just commit a crime, and those men in the bar who brought the pawnbroker up just kind of triggered it. Obviously, Raskolnikov has a strong conscience, so he needed some way to justify committing murder in the first place. Utilitarianism was used as a means to justify his actions, or it should have justified them in his mind. It wasn’t sufficient, especially since he also killed the pawnbroker’s sister, an innocent. I wonder if he would’ve reacted with less severity if he had only killed the pawnbroker.

I also really like talking about how Raskolnikov’s personality is schismatic. Raskol actually means schism in Russian, so it’s even implied by his name. There’s many instances where he is incredibly kind, generous, and loving. In just as many instances he’s cold, feels hatred for his loved ones, and cruel. What I took from this is that humans are like this, most likely to less of an extreme, but all capable of great acts of good and evil. We all have different sides to us.

I found that Rodya was incredibly human, I could relate to him a lot. He obviously wasn’t mentally healthy for most of the novel, he seemed to me to be going through a lot of manic and depressed episodes. I think what really may have made him stand out as someone who could be real was the way Dostoevsky described his behaviour and thoughts.

In terms of Rodya finding happiness in religion in the end of the novel, I’m not sure if I agree. He never actually opens the bible, though he may be on the right path. Some argue that Sonia herself is a metaphor for Christian purity (or something like that), so in loving her he finds God again. I’d rather not think of her as a metaphor, because she seems more human rather than the personification of an ideal, at least to me. I’m glad that he found happiness in her, it gave me hope that I would find happiness in love sometime too.

Dostoevsky reminds us at the end that Rodya would still face hardships. Though that’s just life, isn’t it? I suppose that’s what we all need, some type of happiness that can aid us when times get tough (and they will).

#i tried to make this shorter but there's probably a lot more i could say#hopefully this makes sense and im not an idiot#sleepover saturday#asks#leaunce

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Silent Tales of Yesterday: Prologue

- not the Beginning nor the End

I didn’t know what was there to come. I had no idea how life could be seen, or experienced so differently.

It had been only seven days since she passed out. My life was crumbling into pieces and I had no power to hold onto something. I spent that night at Larry’s, one of the old, cheap bars of my street. I got a few quick rounds on the bar stool and it was no difficult for Larry to realize that I had no intention of sharing a chatter. I was focused on my inner world and I needed silence. Every sip I took turned the volume down by one level. Eventually, everything around me was muted and I could only hear the chilling footsteps that was crawling onto my body. I took my beer with me and sat in front of a fireplace that hosted a tiny fire, which was trying to survive. I was mesmerized and hypnotized by the sparks of the dancing flame when I heard someone talking to me. It almost felt like his words were matching with the cracking voice the burnt wood were yelling out.

“You have an unusual way of dealing with your problems, young man. I’m sorry for your loss.”

I was very shocked at first, but I, obviously, was not in a mood for talking with a random guy that just stopped by. I didn’t even look at his face, all I could see was his reflection on the blazing fire that was just staring at me. I could only see wide lapels of his coat in the fire. I didn’t move an inch. For a few seconds I felt totally still and nonexistent, I was not feeling or thinking about anything.

“I came here to talk, but I see that you’re not ready. Not yet. We will meet again.”

Then, I sensed how his mysterious aura slided and shaded into the dark. I swiftly turned my head back and couldn’t see anyone near me. Everyone was drinking their asses off; Larry was serving the drinks. and Laura was flirting with random boys. It was all normal, it was all corrupted. Only then I remembered of the coldness on my skin and mind, and i realized the fire was too weak to warm me up.

The experience was different and strange, I never went to the Larry’s again. I didn’t have any friends there anyway. In fact, I didn’t have any friends at all, except my sister, Dega. I had trouble seeing the world as she did after she was gone. I couldn’t seize the day as she taught me. My natural benign face was slowly fading as I was seeing what was there; as I was seeing what the past and the future had planned for me.

One year later, I was in a different country, or a different city at least. It was the anniversary of Dega’s death, and I’ve been ready with my six-packs. Somehow, I was facing a fire again, this time it was trapped in a steel barrel on the street and this time, I had ignited it. The wood itself was stubborn and had no plans to surrender to my burning matches, I had to use some books I carried in my backpack. I carefully picked the pages to burn, especially the endings that I didn’t like or didn’t accept as endings.

The fire was accompanying me while I was on my third can, suddenly it burst and made clouds of ashes above.

“Which pages those could be, you think?”

I had no hints of him in my blurred mind when he appeared, but the heat of his tune brought me back to that day at Larry’s. I was shocked and suddenly, almost violently turned my head back to him. He seemed like a normal man in late thirties or early forties with a different shaped coat this time. He had an old fashion style and his high eloquence was rather annoying. The light touched only a few times to his face and I could only see his right eye, shining like a child on a christmas day. I was still not so sure if that was him, but he made it very clear after seeing me.

“You definitely are one of a kind, Mr. Bone. I told you we would meet again, so, um, hello there.”

The way he moved while he was talking was fitting his age and the formal-old clothing he carried, but the last part added to the boy that’s unboxing some presents under a tree. He was both serious and childish at the same time, it got me confused for a minute or so, then I stood up against him.

“Who are you? How the hell you know my name or my residence?”

“Got any more questions coming? No? Alright, I will start with the boring ones. I know who you are, Mr. Bone, as I know about your parents, your sister, the girl you’ve been texting with or anyone. Really. Anyone. I know everyone.”

He, then took a few steps towards me and I unintentionally took a defending position. He didn’t care about my stance and got near the fire. The flames looked like they were celebrating his arrival, boosting up and getting out of the barrel. As he turned his face towards me to continue his speech, he revealed his face to the light. His left eye was blind or the guy had some white eye or something, while the right one was shining bright with red and yellow.

“Your residence? You call this a residence? HA!”

He cleared his throat and took a few steps away from the fire, and now I was sure the fire was reacting to his presence.

“Well, you’re an easy kid. I would say “I followed and gazed upon your soul using the Flames of Anguish” but, it would be a lie. No crazy superpowers. Not yet.”

As I was totally confused, he kept walking and talking with a higher volume.

“Ah, and I saved the most interesting one for the last. Who am I? Ha. Good one, kiddo… or perhaps it is the first thing to ask when encountering a stranger, but, I am no stranger since we are written together.”

“What?”

“I mean, I can, and could be anything, Mr. Bone. If you want, I could go with a first and second name that nobody would remember and I could take a surname, like, Raskolnikov. Well, no. Do not ask for that. This story isn’t that realistic, although it includes some existential issues, we’re not going that far. Hmm... I don’t like cockroaches, so no to Gregories. I could be Hamlet, even, but we would get bored, wouldn’t we? … How about I be Dr. Frankenstein and you, my monster? Well, that’s science and tragedy, I will pass on that. Oh! Big Brother and Winston? Nope. It doesn’t fit you well. Hey, some help would be nice. I could be someone from history or, even, a deity or mythology, but, you know, we’re in a book, so we better-”

“STOP! Cut the bullshit! Why the fuck you’re stalking me, why were you there that day and why did you appear again at her anniversary?!”

“Oh? Death is a human-construct just like the life itself. Belief, knowledge and the term consciousness are nothing but merely human-made resources or, even, primitive tools. We have experienced and will experience different layers of life and death, there is no beginning nor the end, it is rather a circular system that is working within eternity.”

“What?!”

“Well... What I’m saying is, I can bring your sister back. She’s not dead. I mean, she *is* dead, but, not like, dead-dead. You know.”

I felt like everything, the blinking fire, the air above and the earth below, all were making fun of me. I was so angry and somewhat upset at the same time, before I knew it, I punched the guy at once and he fell down. With sudden release of emotions, tears bursted out of my eyes and I was still lost on feelings.

“Great idea... “ he murmured and got up.

“We will be Holmes and Watson, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde… Batman and Robin!”

As I was heavily breathing and having a fight with my own self, he went on and on, talking about things like it was all normal.

“No, Mr. Bone! We will surpass all of them. This is our own story, written together. We will go and explore different worlds, different lives of all kind. We will solve struggles or cause them, we will be gifted with joy or be the gifters. We will live and we will experience our own tale! You can call me Rama or simply Yesterday! Pack yourself up as soon as possible Mr. Bone. stand with me and let us hold the pen of our destiny! The journey shall begin!”

0 notes

Text

Dreamy Guilty Feeling Now: A Curated Playlist

You can check out my previous playlist post, which consists of a mixed Summer grab bag of older hits (click here) and a guide to this online, handy tool (click here) for repeating songs.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GQZ70ttAsjM Young and Beautiful – Lana Del Rey

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8UVNT4wvIGY Somebody I Used To Know

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3AtDnEC4zak We Don’t Talk Anymore – Charlie Puth ft. Selena Gomez

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uK3MLlTL5Ko Rumour Has it – Adele (“obviously, I was pretty pissed off”)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SYM-RJwSGQ8 Habits – Tove Lo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=98WtmW-lfeE Katy Perry – Teenage Dream

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8v_4O44sfjM Jar of Hearts Christina Perry

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFkzRNyygfk Radiohead Creep

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lHje9w7Ev4U Hotel California – The Eagles

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VHoT4N43jK8 Alors On Dance – Stromae

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S_xH7noaqTA Formidable (ceci n’est pas une leçon) – Stromae

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CAMWdvo71ls Tous Les Memes – Stromae (he is one of my favourite artists, if only for THIS VIDEO ALONE, I love it, I do)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l482T0yNkeo Highway To Hell (Official Video) – AC/DC

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Ejga4kJUts Zombie – The Cranberries

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x9UfyF_nleI Stairway To Heaven (Live) – Led Zeppelin

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xwtdhWltSIg Losing My Religion – R.E.M.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RIZdjT1472Y Human – The Killers

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qok9Ialei4c Miss Atomic Bomb – The Killers (also just saying, the title is a well-crafted pun, or at least it can be read that way. I also ADORE this video, because it’s how I feel, deeply, about all my ex-boyfriends, who tend to think I’m insane (thanks, Taylor Swift, for that “Blank Space” idea) that’s all)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MuNTFGnVm4k Alone Together – Fall Out Boy

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TJqL-UHQuP8 Just One Yesterday – Fall Out Boy

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-V1p6EqAEKc Talking To The Moon – Bruno Mars

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W-w3WfgpcGg It Will Rain – Bruno Mars (the distortion of the start, the intro, reminds me of “Starboy” by The Weekend – in a good way, too, the dread, the powerful sense of dread and yes, that’s a Peep Show reference, all that jazz)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PVjiKRfKpPI Take Me to Church – Hozier

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XoQvbDROucQ Arsonist’s Lullaby – Hozier (darkly dreaming little me, but without the LITERAL VOICES in my head, I am not nor have I ever been schizophrenic, the way Raskolnikov from Dostoyevsky’s “Crime and Punishment” was totally)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nH7bjV0Q_44 Work Song – Hozier

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nlcIKh6sBtc Royals – Lorde

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bx1Bh8ZvH84 Wonderwall – Oasis

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cmpRLQZkTb8 Don’t Look Back In Anger – Oasis

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q7yCLn-O-Y0 Carry On – Fun

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-gkibxWr0DY Where Is My Mind – Pixies (life has made of me either a poet or a deep, sarcastic, and jaded psychopath)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hT_nvWreIhg Counting Stars

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HHP5MKgK0o8 Kill ‘Em With Kindness

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FM7MFYoylVs Something Just Like This

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Io0fBr1XBUA Don’t Let Me Down – The Chainsmokers ft. Daya

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NCtzkaL2t_Y Don’t Let Me Down – The Beatles (I prefer the latter “Don’t Let Me Down” here, but that’s just my own humble, if kind of verbose and hence pretentious, and occasionally erroneous though mostly right of course duh opinion. I love this music video, all the Beatles on the roof, all together, as a family, before their tragic artistic split catalysed by Yoko Ono, Lennon’s lover)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DVg2EJvvlF8 Imagine – John Lennon (listen. watch. learn. Please. Now)

0 notes

Text

Is it too late to save the world? Jonathan Franzen on one year of Trump’s America

As the ice shelves crumble and the Twitter president threatens to pull out of the Paris accord, Franzen reflects on the role of the writer in times of crisis

If an essay is something essayed – something hazarded , not definitive , not authoritative; something ventured on the basis of the author’s personal experience and subjectivity- we might seem to be living in an essayistic golden age. Which party you went to on Friday night, how you were treated by a flight attendant, what your take on the political outrage of the day is: the presumption of social media is that even the tiniest subjective micronarrative is worthy not only of private notation, as in a diary, but of sharing with other people. The US president now operates on this presumption. Traditionally hard news reporting, in places like the New York Times, has softened up to allow the I , with its voice and opinions and impressions, to take the front-page spotlight, and book reviewers feel less and less constrained to discuss books with any kind of objectivity. It didn’t use to matter if Raskolnikov and Lily Bart were likable, but the question of “likability,” with its implicit privileging of the reviewer’s personal impressions, is now a key element of critical decision. Literary fiction itself is appearing more and more like essay.

Some of the most influential fictions of recent years, by Rachel Cusk and Karl Ove Knausgaard, take the method of self-conscious first-person witnes to a new level. Their most extreme admirers will tell you that imagination and invention are outmoded contrivances; that to occupy the subjectivity of a character unlike the author is an act of appropriation, even colonialism; that the only authentic and politically defensible mode of narrative is autobiography.

Meanwhile the personal essay itself- the formal apparatus of honest self-examination and sustained engagement with notions, as developed by Montaigne and advanced by Emerson and Woolf and Baldwin- is in eclipse. Most large-circulation American magazines have all but ceased to publish pure essays. The kind persists mainly in smaller publications that collectively have fewer readers than Margaret Atwood has Twitter adherents. Should we be mourning the essay’s extinction? Or should we be celebrating its conquest of the larger culture?

A personal and subjective micronarrative: the few lessons I’ve learned about writing essays all came from my editor at the New Yorker, Henry Finder. I first went to Henry, in 1994, as a would-be journalist in pressing need of money. Largely through dumb luck, I made a publishable article about the US Postal Service, and then, through native incompetence, I wrote an unpublishable piece about the Sierra Club. This was the point at which Henry suggested that I might have some aptitude as an essayist. I heard him to be saying,” since you’re obviously a crap journalist”, and denied that I had any such aptitude. I’d been raised with a midwestern horror of yakking too much about myself, and I had an additional racism, derived from certain wrongheaded notions about novel-writing, against the stating of things that could more rewardingly be depicted . But I still needed money, so I maintain calling Henry for book-review assignments. On one of our calls, he asked me if I had any interest in the tobacco industry- the subject of a major new history by Richard Kluger. I rapidly said:” Cigarettes are the last thing in the world I want to think about .” To this, Henry even more quickly replied: “ Therefore you must be talking about them .”

This was my first lesson from Henry, and it remains the most important one. After smoking throughout my 20 s, I’d succeeded in ceasing for two years in my early 30 s. But when I was assigned the post-office piece, and became terrified of picking up the phone and introducing myself as a New Yorker journalist, I’d taken up the habit again. In the years since then, I’d managed to think of myself as a nonsmoker, or at the least as a person so securely resolved to quit again that I might as well already have been a nonsmoker, even as I continued to smoking. My state of mind was just a quantum wave function in which I could be totally a smoker but also totally not a smoker, so long as I never took measure of myself. And it was instantly clear to me that writing about cigarettes would force me to take my measure. “Thats what” essays do.

President-elect Donald Trump speaks at his election night rally in New York in November 2016. Photograph: Carlo Allegri/ Reuters

There was also the problem of my mother, whose parent had died of lung cancer, and who was militantly anti-tobacco. I’d concealed my habit from her for more than 15 years. One reason I needed to preserve my indeterminacy as a smoker/ nonsmoker was that I didn’t enjoy lying to her. As soon as I could succeed in discontinuing again, permanently, the wave function would collapse and I would be, one hundred per cent, the nonsmoker I’d always represented myself to be- but only if I didn’t first come out, in publish, as a smoker.

Henry had been a twentysomething wunderkind when Tina Brown hired him at the New Yorker. He had a distinctive tight-chested manner of speaking, a kind of hyper-articulate mumble, like prose acutely well edited but scarcely legible. I was awed by his intelligence and his erudition and had promptly come to live in dread of disillusioning him. Henry’s passionate emphasis in “ Therefore you must write about them”- he was the only speaker I knew who could get away with the stressed initial “ Therefore ” and the imperative “must”- allowed me to hope that I’d registered in his consciousness in some small way.

And so I went to work on the essay, every day combusting half a dozen low-tar cigarettes in front of a box fan in my living-room window, and handed in the only thing I ever wrote for Henry that didn’t need his editing. I don’t remember how my mother get her hands on the essay or how she conveyed to me her deep sense of betrayal, whether by letter or in telephone calls, but I do remember that she then didn’t communicate with me for six weeks- by a wide margin, the longest she ever ran silent on me. It was precisely as I’d dreaded. But when she got over it and began sending me letters again, I felt insured by her, insured for what I was, in a manner that is I’d never felt before. It wasn’t just that my “real” self had been concealed from her; it was as if there hadn’t really been a self to see.

Kierkegaard, in Either/ Or , builds fun of the” busy human” for whom busyness is a style of avoiding an honest self-reckoning. You might wake up in the night and realise that you’re lonely in your matrimony, or that you need to think about what your level of consumption is doing to the planet, but the next day you have a million little things to do, and the day after that you have another million things. As long as there’s no end of little things, you never have to stop and confront the bigger questions. Writing or reading an essay isn’t the only style to stop and ask yourself who you really are and what your life might mean, but it is one good way. And if you consider how laughably unbusy Kierkegaard’s Copenhagen was, compared with our own age, those subjective tweets and hasty blog posts don’t seem so essayistic. They seem more like a means of avoiding what a real essay might force on us. We spend our days reading, on screens, stuff we’d never bother reading in a printed book, and bitch about how busy we are.

I quit cigarettes for the second time in 1997. And then, in 2002, for the final time. And then, in 2003, for the last and final day- unless you count the smokeless nicotine that’s coursing through my bloodstream as I write this. Attempting to write an honest essay doesn’t alter the multiplicity of my egoes; I’m still simultaneously a reptile-brained addict, a worrier about my health, an eternal adolescent, a self-medicating depressive. What changes, if I take the time to stop and measure, is that my multi-selved identity acquires substance .

One of the mysteries of literature is that personal substance, as perceived by both the writer and the reader, is situated outside the body of either of them, on some kind of page. How can I feel realer to myself in a thing I’m writing than I do inside my body? How can I feel closer to another person when I’m reading her terms than I do when I’m sitting next to her? The answer, in part, is that both writing and reading demand full attentiveness. But it surely also has to do with the kind of ordering that is possible merely on the page.

Former FBI director James Comey testifying before the US Senate select committee on intelligence in October. Photograph: Saul Loeb/ AFP/ Getty Images

Here I might mention two other lessons I learned from Henry Finder. One was Every essay, even a think piece, tells a story . The other was There are two ways to organise material:” Like goes with like” and “This followed that.” These precepts may seem self-evident, but any grader of high-school or college essays can tell you that they aren’t. To me it was especially not evident that a believe piece should follow the rules of drama. And yet: doesn’t a good debate begin by positing some difficult problem? And doesn’t it then propose an escape from the problem through some bold proposition, and put in obstacles in the form of objections and counterarguments, and finally, through a series of reversals, take us to an unforeseen but fulfilling conclusion?

If you accept Henry’s premise that a successful prose piece consists of material arranged in the form of a story, and if you share my own conviction that our identities consist of the narratives we tell about ourselves, it stimulates sense that we should get a strong make of personal substance from the labour of writing and the pleasure of reading. When I’m alone in the woods or having dinner with a friend, I’m overwhelmed by the quantity of random sensory data coming at me. The act of writing subtracts almost everything, leaving merely the alphabet and punctuation marks, and progresses toward non-randomness. Sometimes, in ordering the elements of a familiar tale, you discover that it doesn’t mean what you thought it did. Sometimes, especially with an debate (” This follows from that “), a completely new narrative is called for. The discipline of fashioning a compelling tale can crystallise thoughts and feelings you merely dimly knew you had in you.