#qufu normal university

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

First Week in QuFu

Well if you like teaching in a sauna, September classrooms in QuFu are for you!

It is sweltering hot here. But despite that, the campus of QuFu Normal University is stunning. Imagine streets lined with weeping willows, sanding cobblestone paths through shaded areas with stone picnic tables, vines over murals of Confucian sayings, and giraffe statues. We even have a little mountain with a traditional style gazebo and gate, none of which I have pictures. I’ll do a better job taking campus pictures soon.

When I arrived at 9pm last Tuesday, it was too dark to really see anything of the city. I haven’t had much time to explore the actual city/town of QuFu yet, but I have explored in and around campus.

My apartment is in the NW quarter of campus. It has a kitchen, bathroom, office, living room, bedroom, and enclosed sunroom/balcony. It came equipped with a toaster oven and microwave, as well as all the furniture I would need. I have a pretty good set up and didn’t have to buy much to make the place habitable. All it needs now is personalization. I don’t have any pictures up or any art so it’s very plain... but I do have air conditioning in my bed room and in the office 👌

The foreign language building is on the exact opposite side of campus in the SE quarter. It is only about an 11 minute walk. The classrooms come with a projector and computer (no WiFi), and a black board that gets covered up by the projector... lol.. The students are super dedicated and hard working.

I’ve found one cat cafe, a cute coffee shop with Harry Potter books in Chinese, a “pizza” shop on campus, and a printing shop with a cat in it. I’ve also managed to use Chinese amazon (TaoBao) to deliver something to campus... it didn’t go where I wanted it to go... but it still made it to campus which counts for something! Also found a gym I can join if I get around to it.

Went briefly to Jining, the closest real city, to do medical checks. Still more paperwork required to get my work permit and residency permit. *sigh*

It’s been a pretty good week so far. The only downfall was a scheduling issue. I was scheduled to work more hours than my contract allows. But since the semester had already started (couldn’t change it before then because the scheduling lady was out of town), it caused a lot of drama to fix the situation. Another foreign teacher had to take on my extra classes. I only taught sophomores Monday this week because freshmen don’t start till the last week of September. But now with the schedule change, they dropped my sophomore classes. So now I’m back to not teaching until the 24th. I only work Tuesday-Thursday now, but teach the same lesson plan 6 times... I also have to get around to telling the sophomores that they won’t be my students anymore. :(

I know many people are wondering what I’ve been eating since I am known as a picky eater so enjoy:

#qufu#english language fellow#china#efl#esl#tefl#tesl#tesol#elprograms#曲阜#中国#山东#济宁#shandong#jining#apartment#food#chinese food#university#qufu normal university

1 note

·

View note

Link

youtube

Since she began posting rustic-chic videos of her life in rural Sichuan province in 2016, Li Ziqi, 29, has become one of China’s biggest social media stars. She has 22 million followers on the microblogging site Weibo, 34 million on Douyin (China’s version of TikTok) and another 8.3 million on YouTube (Li has been active on YouTube for the last two years, despite it being officially blocked in China).

Li’s videos – which she initially produced by herself and now makes with a small team – emphasize beautiful countryside and ancient tradition. In videos soundtracked by tranquil flute music, Li crafts her own furniture out of bamboo and dyes her clothing with fruit skins. If she wants soy sauce, she grows the soybeans themselves; a video about making an egg yolk dish starts with her hatching ducklings. The meals she creates are often elaborate demonstrations of how many delicious things can be done with a particular seasonal ingredient, like ginger or green plums.

There is even a Li Ziqi online shop, where fans can purchase versions of the steel “chopper” knife she uses to dice the vegetables she plucks from her plentiful garden, or replicas of the old-fashioned shirts she wears while foraging for wild mushrooms and magnolia blossoms in the misty mountainside.

youtube

While she occasionally reveals a behind-the-scenes peek at her process, Li – who did not respond to interview requests for this article – is very private. By all accounts, she struggled to find steady work in a city before returning to the countryside to care for her ailing grandmother (who appears in her videos).

Recently, Li has been thrust into a wider spotlight by the Chinese government, who seem to have realized her soft power potential. In 2018, the Communist party of China named her a “good young netizen” and role model for Chinese youth. In September 2019, the People’s Daily, a CPC mouthpiece, gave Li their “People’s Choice” award, while last month, state media praised Li for helping to promote traditional culture globally, and the Communist Youth League named her an ambassador of a program promoting the economic empowerment of rural youth.

Revealed: how TikTok censors videos that do not please Beijing Read more

As the government increasingly champions her, Chinese citizens have taken to Weibo to question whether Li’s polished, rather one-dimensional portrayal of farm work conveys anything truly meaningful about contemporary China – especially to her growing international audience on YouTube.

They have a point: Li’s videos reveal as much about the day-to-day labor of most Chinese farmers as the Martha Stewart Show does the American working class. As Li Bochun, director of Beijing-based Chinese Culture Rejuvenation Research Institute told the media last month: “The traditional lifestyle Li Ziqi presents in her videos is … not widely followed.”

In reality, many of China’s rural villages have shrunk or disappeared completely in past decades as the nation prioritized urbanization and workers migrated to cities, with research suggesting the country lost 245 rural villages a day from 2000 to 2010. The 40% of China’s population still living in rural areas encompass a huge diversity of experience, yet life can be difficult, with per-capita rural income declining sharply since 2014 and environmental pollution often as rife as in industrial centers. That’s not to say the beautiful forests and compelling traditions of Li’s videos are not genuine – like many social media creators, she simply focuses on the most charming elements of a bigger picture.

youtube

So what do Li’s videos reflect about modern China, if not average daily life in the countryside?

For one, they say something about the mindset of her mainland audience – primarily urban millennials, for whom a traditional culture craze known as “fugu” or “hanfu” has been an aesthetic trend for a number of years.

“Fugu”, according to Yang Chunmei, professor of Chinese history and philosophy at Qufu Normal University, reflects the “romanticized, pastoral” desires of youth “disillusioned by today’s ever-changing, industrial, consumerist society.” In practice, it looks like young people integrating more traditional clothing into their daily looks, watching historical dramas and following rural lifestyle influencers like Li. (While Li is an extremely popular example of the trend, she’s not the only young farmer vlogging in China right now, and outdoor cooking videos of people making meals with wild ingredients and scant equipment are a genre of their own on Douyin.)

Among urban millennials in the west, giving up the nine-to-five grind and living humbly and closer to nature is a popular dream. In China, the contemporary experience of burnout is compounded by the intensity of “urban disease”, an umbrella term for the difficulties of living in megacities like Shanghai or Guangzhou, which can be used to refer to everything from traffic jams and poor air quality to employment and housing scarcity.

Also at play in Li’s popularity is the particular tenor of Chinese wistfulness. “It’s called xiangchou. Xiang means the countryside or rural life, and chou means to long for it, to miss it,” says Linda Qian, an Oxford University PhD candidate studying nostalgia’s role in the revitalization of China’s villages.

“It is quite prevalent for youth living the city life. They get really sick of [the city] so the countryside” – or a fantasy of it – “looks increasingly like the ideal image of what a good life should be.”

Qian also likens Li’s appeal to that of “Man vs Wild”-style entertainment in the west. “We’ve gotten to a certain point of materialism and consumption where there’s only so much you can buy, and we’re like, ‘What other experiences can I have?’” she says. “So we go back to what humans can do.”

Yet as her fame grows internationally, some have questioned, in comments, blogposts and Reddit threads, whether Li’s channel is communist propaganda.

In addition to providing China a form of international PR, Li embodies a kind of rural success the government hopes to generate more of through recent initiatives. With the aim of alleviating rural poverty, the Communist Youth League has embarked on an effort to send more than 10 million urban youth to “rural zones” by 2022, in order to “increase their skills, spread civilization, and promote science and technology”.

“We need young people to use science and technology to help the countryside innovate its traditional development models,” Zhang Linbin, deputy head of a township in central Hunan province, told the Global Times last April.

By using technology to create her own rural economic opportunities while simultaneously championing forms of traditional Chinese culture before a huge audience, Li may seem like a CPC dream come true.

youtube

According to Professor Ka-Ming Wu, a cultural anthropologist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong: “Li represents a new wave of Chinese soft power in that she’s so creative and aesthetically good, and knows how to appeal to a general audience whether they’re Chinese or not.” And yet, “I don’t think this is some kind of engineered effort by the Chinese state,” she says.

Li’s narrative hinges on her failure to thrive in the city; that failure is antithetical to China’s overarching narrative of progress and urban opportunity. Were she a manufactured agent of propaganda, Wu speculates, “[Her failure] is something the Chinese state would never even mention.

“And I think that’s what really fuels her popularity,” says Wu. “That despair of not being able to find oneself in the ‘Chinese dream’. I don’t think she’s propaganda because one of her major successes is that she’s making that failure highly aesthetic … However, the Chinese government is very smart to appropriate her work and say that she represents traditional culture and promote her.”

According to some Chinese media, Li’s content is better than propaganda – doing more to generate genuine domestic, and especially international, interest in rural Chinese traditions than any government initiative of the past decade. “Dozens of government departments with billions at their disposal spent 10 years on propaganda projects, but they have done a worse job than a little girl,” writes the South China Morning Post’s Chauncey Jung, summarizing a tweet from journalist Jasper Jia.

However you feel about Li as a cultural force, her ability to flourish despite a unique set of contradictory circumstances is impressive. Out of the past and present, failure and success, independence and authoritarianism, she’s spun a truly pleasant vision. If only life was really so simple.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Thinker" at Qufu Normal University, China. The original statue at the Musée Rodin is guarding the Gates of Hell 🔥😈🔥

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Chen Yuxi. Born in 1946, Shandong Licheng. Good at Chinese painting. When I was young, I loved painting and painted the disciples of Mr. Hei Bolong and Mr. Chen Weixin. In 1976, he taught at the Art Department of Qufu Normal University. In 1980, he was admitted to the Guangxi Academy of Fine Arts as a graduate student of the Lingnan School Master Huang Dufeng.

#Chen Yuxi#Chen Weixin#Chinese master#Asian brush painter#waterfall#mountains#scenary#Chinese sumi-e#sumi ink#Xuan paper#rice paper

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

New top story from Time: ‘We Want to Help the World Better Understand China.’ Meet Chen Xiaoqing, the Film Director Using Food to Make Friends

The humblest food becomes wondrously photogenic in the films of Chen Xiaoqing, creator of the hit Netflix series Flavorful Origins and its progenitor Once Upon a Bite. Dumplings are crafted on timber boards amid billows of flour. Steam shrouds mottled crabs, cooking with ginger and chili in in tall stacks of wicker baskets. Fishermen wade into crashing surf on wooden stilts to snare sardines with A-frame nets. There are aerial shots of emerald rice terraces, time-lapse sequences of drying bricks of tea, and mortar-eye views of pestle-pounded spices.

There’s not a fast-food restaurant or production line in sight in this romanticized glimpse of a homespun culinary culture sadly threatened by industrial kitchens, agribusiness and progress.

“Our food must be delicious, beautiful, with a legacy and connection to local culture and geography,” Chen tells TIME in his Beijing office. “For the people, they must really love the food, put in their labor and have a deep connection with it.”

Chen, 55, originally from China’s eastern Anhui province, has charged himself with keeping many of his homeland’s food traditions alive. Over the past three decades, the world’s most populous nation has become the world’s number two economy and home to the planet’s largest middle class. In the rush to sate 1.4 billion bellies, corners were cut and standards plummeted, leading to a slew of food safety scandals. Today, though, the impetus has shifted from quantity toward quality natural produce. “People are leaning towards healthier options, not just vegetables, but wanting to know their food is processed with care,” says Shanghai-based food blogger Rachel Gouk.

It’s a trend epitomized by the critically acclaimed Flavorful Origins, a series of short films and the first original Chinese documentary to be bought by Netflix. Chefs chosen for inclusion in Chen’s work can see demand for signature dishes soar hundred-fold overnight. The first series spotlighted the coastal cuisine of Guangdong’s Chaoshan region, with the second focusing on the fresh, fragrant spices of southwestern Yunnan province, which draws much influence from neighboring Laos and Myanmar.

The third season, set in China’s central Gansu province, debuts on Netflix next month. Gansu is a thin strip of territory stretching more than a thousand kilometers from dunes in the north to lush mountains in the south. It also boasts a significant Muslim minority. “So they have really different types of food that reflect the local terrain and [cultures],” says the filmmaker.

Chen has given himself an additional brief at a time of historic tensions between the U.S. and China. The superpowers may be embroiled in a trade war, accusations of spying and IP theft, the sanctioning of officials over the detention of one million Uighur Muslims in China’s far west, and the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic—but Chen hopes that food can help soften his country’s image. “Through beautiful food we want to help the world better understand China and the Chinese people,” he says.

DOClabs Beijing In this still taken from Season 2 of the series Once Upon a Bite, which debuted on Apr. 26, 2020, a dish known as multiple-layer oil cake is seen on a table in Yangzhou, China.

Chinese food in the U.S.

The U.S. love affair with Chinese cuisine is long and complex. In fact, one of the most American staples, ketchup, is actually Chinese in origin. The name ketchup derives from the Hokkien Chinese kê-tsiap, referring to a fermented fish-based sauce that became popular with colonial Britons as far back as the 18th century.

When the first Chinese immigrants arrived in American in the mid-19th century, xenophobic ditties made reference to their unfamiliar eating habits. But in New York City, Chinatown flanked the Jewish Lower East Side, and the Jewish community became early adopters of the new cuisine. By 1899, the enduring tradition of Jews eating in Chinese restaurants at Christmas had already been documented. In the early 20th century, the Boston Globe was telling readers to consider Chinese themes for their wedding banquets, while the Chicago Tribune declared Chinese restaurants the perfect place to woo a girl on a first date.

“Chinatowns, which had been framed as dens of iniquity, became the first counterculture cool among the American cognoscenti, and then became mainstream,” says John Pomfret, a former Beijing bureau chief for the Washington Post and author of The Beautiful Country and the Middle Kingdom: America and China, 1776 to the Present.

When a devastating earthquake flattened San Francisco in 1906, that city’s Chinatown was prioritized for reconstruction because of the tourist dollars it brought in. By 1919, the American Chemical Society was advising that Chinese food was good for health. A decade later, nearly a third of American counties had at least one Chinese resident, many of whom opened restaurants. “The Chinese became the most dispersed ethnic group in the country,” says Pomfret. Today, there are more Chinese restaurants in the U.S. than McDonalds and KFC outlets combined.

Read more: The Untold Story of the World’s First Michelin Three-Star Chinese Restaurant

The question is whether food can still build bridges today. A Pew Research Center survey published in July found 73% of American adults had a negative view of China, the highest since the question was first asked 15 years ago. Verbal attacks and assaults on Asian Americans have soared since the coronavirus took hold. At the recent presidential debate, Donald Trump again sought to assign blame for the pandemic, saying “It’s China’s fault.”

For Chen, however, there are more commonalities than differences. He points out that around 10,000 years ago people across the world began cultivating wheat. In the West, they used it to bake bread; in the East, they steamed buns. “People may focus on the difference between East and West as being like fire or water,” says Chen. “But in terms of food—bread or buns—it’s not that drastic.”

Not all of China’s culinary culture meets with acceptance. The consumption of rare, wild species for their purported health benefits has long been of concern. The 2002 to 2003 SARS pandemic was eventually traced to civet cats sold for consumption at a market in China’s southern Guangdong province, and a leading—though unproven—hypothesis is that there is a similar provenance for coronavirus, which first came to light in a market in the central city of Wuhan.

Chen says he is “very concerned” about the protection of wildlife, never features endangered creatures in his programs and even puts health disclaimers on scenes that feature raw shellfish.

“In truth, most Chinese people eat a limited selection of food,” he says. “They don’t even eat steak rare because they think it’s unhygienic. They have to cook everything. The sample of the coronavirus found in the market has nothing to do with food; it has to do with the modernization of the entire country. If we can ventilate and make our markets more sanitary, such problems can be solved.”

DOClabs Beijing In this still taken from Season 2 of the series Once Upon a Bite, which debuted on Apr. 26, 2020, dishes of braised pork rice from Sichuan, China are being steamed.

Chinese cuisine and national identity

In some ways, Chen is riding a wave of national interest in a sentimentalized past—a craze known as fugu. Increasingly, Chinese millennials are donning hanfu robes that date from the Tang Dynasty, playing bamboo flutes and quaffing Osmanthus wine in order to reconnect with their cultural heritage. One father in Sichuan province recently dispensed with the family car and decided to take his son to kindergarten on a bull. He said that while using this archaic form of transport, he would “explain ancient poems and traditional culture” to the youngster. For a rapidly urbanizing society, increasingly disillusioned by a hyper-commercialized race to riches, such affectations prove alluring.

Some academics frame this cultural revival in terms of a restored national pride. It could be seen as “embarrassing that Chinese people attend social functions or major international occasions dressed in suits, ties, and leather shoes, which not only fail to represent their homeland, but also imitate the garb worn by the erstwhile outsiders who once brought China to its knees,” writes Yang Chunmei, a professor of Chinese history and philosophy at Qufu Normal University.

China’s strongman president, Xi Jinping, has certainly made many calls for the preservation of Chinese tradition while decrying the influence of “Western values”—even if much that tradition is awkwardly rooted in Imperial feudalism and at clear odds with the Marxist doctrine that the Chinese Communist Party is committed to upholding.

Read more: A Very Brief History of Chinese Food in America

In this context, Chen’s work coalesces national identity at home even as it seeks to break down barriers abroad. He has set his eyes beyond China, citing Lebanon as his dream destination (“It’s got European influence, Arab influence, that’s very interesting”). He became enamored with the Middle East while filming in Jerusalem.

“We saw that Jews, Arabs, Christians have different religions and cultures,” Chen says, “but they all appreciate the same food.”

Given the intolerance that roils the Middle East, it’s a bit of a stretch to posit some sort of regional amity based on a shared love of olives and flatbread, but Chen is undeterred.

“There are constantly quarrels and tensions, not only between China and America, but between all different cultures,” he says. “The best way to solve them is communication—and people always talk over food.”

—Video by Zhang Chi/Beijing

via https://cutslicedanddiced.wordpress.com/2018/01/24/how-to-prevent-food-from-going-to-waste

0 notes

Text

You Thought Your School’s Cheerleaders Were Good? Wait Until You See These

Back in high school, cheerleaders were known as the cool girls.

But if you’ve ever watched any of the “Bring It On” movies, you know that cheerleading is a lot more competitive than simply waving pom-poms around and cheering on the football players. Tasked with upping the morale and motivating both the team and the crowd, cheerleading is just as much a rigorous sport as any other. And while most cheer squads incorporate an impressive array of gymnastics moves, one university decided to have its students recreate a classic video game.

More than 355 students participated in the opening ceremony of the Qufu Normal University’s sports day held recently in eastern China. Paying homage to the game of Tetris, groups of cheerleaders and students can be see recreating the classic game on the field by becoming life-sized Tetris tiles.

This intense routine took more than two months to perfect and was inspired by the Tetris theme song.

(via Daily Mail)

I can only imagine the crowd’s reaction as they got to witness this! Share this epic routine with others who will want to relive their youth.

More From this publisher : HERE

=> *********************************************** See Full Article Here: You Thought Your School’s Cheerleaders Were Good? Wait Until You See These ************************************ =>

You Thought Your School’s Cheerleaders Were Good? Wait Until You See These was originally posted by 15 VA Sports News

0 notes

Text

You Thought Your School's Cheerleaders Were Good? Wait Until You See These

New Post has been published on https://kidsviral.info/you-thought-your-schools-cheerleaders-were-good-wait-until-you-see-these/

You Thought Your School's Cheerleaders Were Good? Wait Until You See These

Back in high school, cheerleaders were known as the cool girls.

But if you’ve ever watched any of the “Bring It On” movies, you know that cheerleading is a lot more competitive than simply waving pom-poms around and cheering on the football players. Tasked with upping the morale and motivating both the team and the crowd, cheerleading is just as much a rigorous sport as any other. And while most cheer squads incorporate an impressive array of gymnastics moves, one university decided to have its students recreate a classic video game.

More than 355 students participated in the opening ceremony of the Qufu Normal University’s sports day held recently in eastern China. Paying homage to the game of Tetris, groups of cheerleaders and students can be see recreating the classic game on the field by becoming life-sized Tetris tiles.

This intense routine took more than two months to perfect and was inspired by the Tetris theme song.

(via Daily Mail)

I can only imagine the crowd’s reaction as they got to witness this! Share this epic routine with others who will want to relive their youth.

Read more: http://www.viralnova.com/tetris-cheerleaders/

0 notes

Photo

@justinbieber #justinbieberimagines #justinbieberbeliebersforever #justinbieber#justin#Bieber #bizzle #beliebers#beliebersforever #bieberfever#lovejustinbieber#WhatDoYouMean#justinbieberbeliebersforever #WhatDoYouMean#love#beliebersjustin #beliebershelpbeliebers #bieberisback #purpose #purposetour #purposetourmerch #china🇨🇳 #friends (在 Qufu Normal University)

#friends#bieberisback#purpose#purposetourmerch#justinbieberbeliebersforever#purposetour#lovejustinbieber#bieber#justin#beliebers#bieberfever#justinbieberimagines#beliebersforever#love#bizzle#beliebersjustin#beliebershelpbeliebers#whatdoyoumean#china🇨🇳#justinbieber

0 notes

Link

Until 1530, sculptural images of Confucius and varying numbers of disciples and later followers received semiannual sacrifices in state-supported temples all over China. The icons' visual features were greatly influenced by the posthumous titles and ranks that emperors conferred on Confucius and his followers, the same as for deities in the Daoist and Buddhist pantheons. This convergence led to visual conflation and aroused objections from Neo-Confucian ritualists, culminating in the ritual reform of 1530, which replaced images with inscribed tablets and Confucius s kingly title with the designation Ultimate Sage and First Teacher. However, the ban on icons did not apply to the primordial temple of Confucius in Qufu, Shandong. Post-1530 gazetteers publicized the distinction by reproducing a line drawing of this temples sculptural icon, and persistent replications of this image helped to popularize his cult. The same period saw a proliferation of non-godlike representations of Confucius, including his portrayal as a teacher, whose iconographic origins can be traced to a painted portrait handed down through generations of his descendants. In recent years, variations of this teacher image have become the basis for new sculptural representations, first in Taiwan, then in Hong Kong and the Chinese diaspora, and finally on the mainland. Now installed at sites around the world, statues of Confucius have become a contested symbol of Chinese civilization.

Julia K. Murray, "Idols" in the Temple: Icons and the Cult of Confucius, The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 68, No. 2 (May, 2009), pp. 371-411.

Various efforts in recent centuries to foreground the moral dimension of Confucius’s legacy have obscured practices and beliefs involving icons, along with other religious aspects of Confucianism. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Jesuit missionaries tried to convince papal authorities in Rome that Confucianism was an ethical philosophy (Jensen 1997, 63-70, 129), so that efforts to spread Christianity in China would not be stymied by requiring converts to give up rituals for worshiping Confucius Similarly, in the nineteenth century, the Protestant missionary-translator James Legge argued that the ancient Confucian classics merely needed to be supplemented with Christianity, just as the Bibles Old Testament was completed by the New Testament (Mungello 2003, 590). Moreover, from the sixteenth century onward, Confucian temples were austere buildings where inscribed tablets were displayed, unlike Buddhist temples and popular-cult shrines with sculptural icons in sensuous pro fusion.2 Although Kang Youwei (1858-1927) sought to establish Confucianism as Chinas official religion (zongjiao) at the end of the nineteenth century, on the model of Christianity in Western nations, he made little headway before falling from power in the coup that reversed his 1898 reforms (Chen 1999; Goossaert 2005, 2006). Because regular worship of Confucius was on the official Register of Sacrifices (Sidian), and thus was closely identified with the imperial system, the collapse of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) undercut subsequent efforts to create a religion based on Confucianism. In the early decades of the twentieth century, some nationalist modernizers wanted to discard Confucius altogether, while others found it expedient to present him as Chinas counterpart to the Wests great rational philosophers. Suppressing what they considered to be idolatry and superstition, they emphasized a Confucius who did not concern himself with "ghosts and spirits." And in recent years, global advocates of "New Confucianism" have focused on his ideas about self-cultivation and morality.3 To some, Confucian concepts of reciprocal responsibility in a hierarchical society suggest an Asian alternative to Western-style democracy. These different efforts have created a widespread conception of Confucianism that is defined by a set of ancient texts, the civil service examination system based on their mastery, and the promotion of social virtues such as benevolence (ren), filial piety (xiao), propriety (li), and righteousness (yi).

[...]

Other conceptions of Confucius emphasized his roles as a teacher and as an expert on ancient ritual, instead of as a preternaturally insightful and prescient leader who communed with heaven. In some parts of the Analects (Lun yu), Confucius is portrayed as a human being who endured much travail and disappointment, especially while traveling the ancient states in search of a ruler who would take his advice (Csikszentmihalyi 2002).7 By the late Eastern Han period, this more mundane Confucius had largely overshadowed the superhuman figure. Nonetheless, the messianic sage was featured in the so-called apocryphal texts (weishu It H) of the late Han and post-Han periods (e.g., Wang Jia 1966,3:4?5). In addition, the "modern text" traditions retained their vitality in South China well into the Period of Disunion (Wilson 1995, 32). Furthermore, the Kong lineage perpetuated and embellished the legends in oral traditions and written genealogies, even down to the present day.8 Claiming descent from Confucius, lineage members had a vital interest in preserving a heroic conception of their ancestor and in maintaining their own cohesion (Wilson 1996). Emperors from the Han through the Qing dynasties awarded noble titles, tax exemptions, official positions, and lands to the descendants who maintained sacrifices to Confucius in Qufu.

Although the earliest forms of veneration and sacrifice to Confucius occurred in funerary and memorial contexts, the observances themselves increasingly displayed the features of a deity cult. Confucius continued to receive sacrifices at his grave long past the normal period for commemorative worship (Jensen 2002, 180-86; Sima 1982, 47:1945). Moreover, persons with no blood relation to him made these offerings, contrary to the customs of familial worship, which prescribed that a son should lead funerary rites?but Confucius s son had predeceased him. After Confucius died in 479 BCE, his disciples carried out the rites of mourning, and the especially devoted Zi Gong M kept a six-year vigil in a hut beside the burial mound (Sima 1982, 47:1945). Local authorities maintained offerings at this site for generations afterward. The place where Confucius had gathered with his disciples became a memorial hall, and his personal effects were displayed there. The Grand Historian Sima Qian (145-86 BCE) reported seeing the masters clothes, cap, zither (qin), books, sacrificial vessels, and carriage in the memorial hall when he visited Qufu. In 195 BCE, the Han founding emperor Gaozu (r. 206-195 BCE) performed a grand sacrifice (tailao X ?) to Confucius in Qufu, offering an ox, sheep, and pig, along with wine and other foodstuffs (Sima 1982, 47:1945-46). In 136 BCE, Han Wudi (r. 141-87 BCE) canonized the textual tradition of Confucius and his followers by abolishing the posts of Erudite (boshi) held by court scholars who were experts in texts belonging to other traditions (Wilson 1995, 29). Other Han emperors awarded posthumous titles of nobility to Confucius and gave material support to his descendants and cult, providing for semiannual sacrifices in Qufu after 169 CE (Wilson 2002c, 261).

By the third century, sacrifices to Confucius were also being performed elsewhere, typically in academic settings. The first sacrifice documented outside Qufu took place in 241 CE at the imperial university (Biyong) in Luoyang, the capital of the kingdom of Wei (220-65), and several more were per formed there under the Western Jin dynasty (265-316) (Wilson 2002b, 74).9 During the centuries of disunion, various northern and southern regimes established state-sponsored temples in their capitals for conducting sacrifices to Confucius and his legacy.10 The Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) dynasties continued this practice in a reunified empire. The Tang founding emperor Gaozu (r. 618-26) established a temple at the National University (Guozi xue) in Chang'an (modern Xi'an, Shaanxi) and personally sacrificed there in 624 (Ouyang 1975, 1:9, 17). The Tang eastern capital at Luoyang also had an imperially sponsored temple. Initially, it was the Duke of Zhou JH the wise regent to the young heir of the Zhou dynasty founder, who was honored as First Sage (Xian sheng), and Confucius received sacrifice as Correlate (Fei) and First Teacher (Xian shi). In 628, a memorial submitted by Fang Xuanling (579-648) convinced the Tang emperor Taizong (r. 626-49) that sacrifices offered in a school should be directed to a teacher. Accordingly, Taizong ended sacrifices to the Duke of Zhou and designated Con fucius as First Sage, with the disciple Yan Hui II d? as Correlate and First Teacher (Ouyang 1975, 15:373, 375).11 Taizong extended the cult to lower levels of administration in 630 by requiring every prefectural and county school to build a temple to Confucius, thus creating a systematic network of state-sponsored temples (Ouyang 1975, 15:373). Located inside or adjacent to the government schools, these temples carried out regular sacrifices to Confucius twice a year, in spring and autumn.

Tang ritual codes ranked the sacrifice to Confucius as one of several mid-level rites (zhong), prescribing specific implements, offerings, music, and participants.12 The liturgy imitated that of another mid-level state cult, the worship of the Gods of Soils and Grains (Sheji), which had existed in classical antiquity and whose rituals were prescribed in the Record of Rites (Liji). Because the ceremony for sacrifice to Confucius had no fixed classical form of its own, it was susceptible to innovations, and procedural details often changed. Most significantly, portrait icons were introduced into the ceremony, probably inspired by the images of the Buddha and bodhisattvas in Buddhist temples. Starting in the Tang period, the Chan Buddhist practice of using portrait effigies in memorial rituals for deceased abbots and monks (Foulk and Sharf 1993-94) provided an additional model that encouraged the use of icons in Confucian temples.

0 notes

Text

Second Week in QuFu: Small Victories

Week 2

Since having my schedule rearranged, I have found myself with a lot of free time. I am having fun listening to the military training that all my freshmen students have to go through. It is also “fun” to walk around campus and have them get in trouble for staring at me when they’re supposed to be listening to their drill sergeant. (All freshmen in university go through mandatory military training lasting from 2 weeks to a month). My classes will start the last week of September.

(Good camouflage)

The English department finally met up with us to talk about expectations and regulations. Since I am teaching all 6 sections of Speaking and Listening 1 for freshmen, I basically get to do what I want. I have textbooks, and there is a loose “use 50% of the books” rule. After looking at those textbooks, I’ll most likely be using them as homework and for support material. This course will basically be a conversation class. The textbooks seem to cover things like making appointments, answering a phone, how to end a conversation, how to begin a conversations, and ordering food at restaurants, etc. This all seems like very low level stuff compared to what the sophomores were capable of doing during the single class meeting I had with them.

I’m hearing whispers of a school sponsored trip to the Confucius temple this month, so look forward to more on that soon. We (the other foreign teachers and I) have also finally gotten the ball rolling on Chinese classes to begin next week. We picked up our textbooks this week to give approval. My book is an HSK5 (proficiency exam) prep book. It basically contains like 8 practice exams. I’m interested to see how the tutor will spend “class” time to help me prep for it.

Since last week there have been quite a few exciting developments.

The foreign teachers all had a potluck. The new teachers (Kim and I) didn’t have much to contribute since we are still figuring out where to get ingredients and kitchen supplies. We did cut up a lot of fruit though. Sharlyn (another Fellow) made some bread, coleslaw, and some yummy veggie pasta. Karen, a short term visiting physics professor from Canada, brought some bread and baozi. Jordan, a French teacher (from France), brought some wine and an interesting perspective to our political talks about Trump, healthcare, and other things affecting Americans and Canadians. Mike (the host) had prepared another pasta dish, and some banana pudding. It was good to connect with the other foreign teachers on campus.

I met a senior physics student (who likes to point out how young I am). Since 1) I don’t teach seniors, 2) physics students don’t take English, and 3) she’s only 3 years younger than me, I felt safe agreeing to hang out with her. This hangout session comprised the first real test of my Chinese proficiency other than small talk or asking for service in stores in restaurants. She took me on a scooter ride around QuFu. Next to the Confucius temple is a shopping/eating district. Apparently, it is where all the young people go to hang out in town. We ordered some vegetarian (much to the regret of my new friend) noodles, some frozen fruit yogurt, and did some shopping. They (her friend showed up at this point) were very interested in how I would look in Chinese fashion. Unfortunately for me, this meant trying on a lot of clothes I knew wouldn’t fit simply because our bodies are shaped differently (particularly, Western shoulders will almost never comfortably fit into Chinese shirts even if your chest and rest of your torso manage to fit that size). Afterwards, we went to a street next to a shopping center I’ve visited before. This shopping center has a KFC and a Watsons (think Walgreens or CVS with no medication). The cool thing, though, was that this street, apparently, turns into a night market. I would have never guessed. They set up carnival games and have lots of street vendor foods. Afterwards, they drove us back to campus and we shared a meal in one of the school’s many cafeterias. This turned out to be very nice because I had been too overwhelmed to enter the flooded cafeterias on campus thus far. After eating dinner, they wanted to see my apartment. This might sound weird to some people, particularly those going “whoa don’t invite students to your apartment.” However, this curiosity is borne out of the fact that there is a huge difference in where the local staff and students are housed and where the foreign teachers and students are housed. I showed them my apartment to which they lamented that I live in a castle. I asked if they would let my friend (another foreign teacher on campus) see their dorm since she hasn’t any experience with Chinese college campuses. They agreed after warning me that it would be very messy. After collecting the other teacher, we went to see the student dorms.

I didn’t take any pictures as it would have been rude. Just imagine a building from a post apocalyptic zombie movie. There are bars on all the windows (I assume to prevent suicides or accidents or both). The lights in the hallways don’t work. There aren’t showering facilities anywhere in the buildings and students resort to sponge bathing. All the doors look like prison doors, short, metal, and inset into thick walls. All the doors are locked with padlocks if no one is in the room, and left unlocked if a student is inside. Each roommate has a key for the padlock. When you open the door to the dorm, you will see a room smaller than most people’s bedrooms back home. On the left side of the room are bunkbeds to accommodate four students and the right wall is lined with desks. There is a small porch for them to hang laundry. There is barely any room to walk and definitely no semblance of personal space or privacy. In some dorms, there are 6 beds (four on the left wall, and two high rise beds on the right side that have the desks under them).

After showing us their dorm, they wanted to show us where the graduate students stay on campus. The difference is night and day. They have a completely newly renovated building. It has an elevator (my building doesn’t even have an elevator). Central heating and air-conditioning. Motion detecting recessed LED lighting in the hallways that turn on and off as you move down the hall. A fancy restaurant like cafeteria in the basement. Only three students to a room, each room containing their own shower and bathroom. Lockers are next to each of the beds for them to put their personal belongings in. They had an even better porch than my apartment, with laundry drying racks that elevate and lower from the ceiling.

Anyways, that ends the “hang out session”.

Monday the 10th was Teacher Appreciation Day. Sad for me since I no longer have students. But not really, since students still used WeChat to send me messages and found me to give me chocolate. One of my students interviewed me about my love life (I was under the impression it was only going to be sent to my students) and then published it on the school website for a “teacher highlight.” Now faculty and staff all know about my love life so that is fun! If not extremely awkward. But the page also included student comments about what they think of me as a teacher. Since I only had one class with them, a lot of the comments are that I smile a lot, I talk loud (#AmericanProblems), and that I’m pretty.

I also finally got paid my living stipend by my university. And since nothing is really available in stores around here (like measuring spoons and cheese and butter), I am happy to announce I have figured out how to have things like this delivered through the Chinese version of Amazon (TaoBao). I may or may not have also purchased a popcorn popper for the microwave (anyone who knows me won’t be surprised by this).

This week also included my first trip to the gym. The other foreign teacher and I joined the most “western” gym we could find. They send us the group class offerings in a weekly WeChat message. Not that that helps either of us since she can’t read Chinese, and I don’t know any workout language in Chinese. However, after doing some conversions from miles to kilometers and figuring out what speed I needed to be running at… I can now report it is extremely hard to run in polluted air. You really can’t breathe. The weight machines are also a trip, because the weights don’t list what weight they are, not in kilograms or lbs. I might take a silver sharpie and just write my best guesstimate. I maxed out one of the machines though, so I’m pretty sure they’re not calibrated the same way they are in the US. Watching the guys faces though when I put max weight on the leg machines was #priceless.

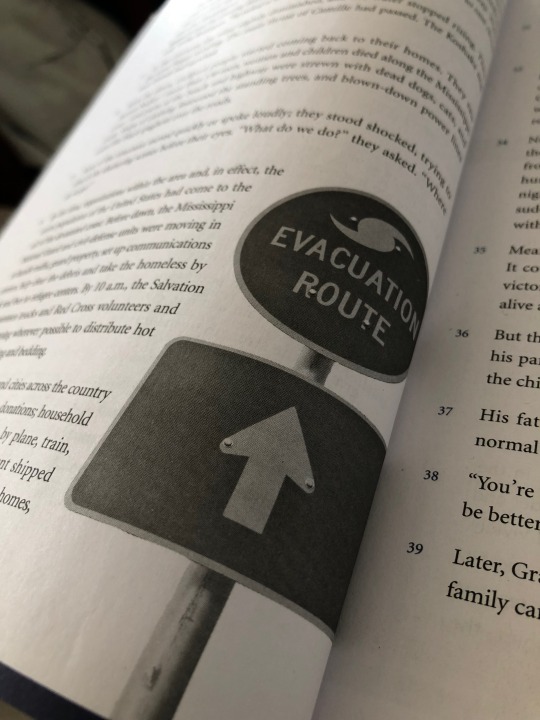

Yesterday, Tuesday the 11th, I observed a local teacher’s English class. It was a group of junior students doing intensive reading. Their text was about hurricanes and the destruction they cause in the US. So naturally, this North Carolinian had to keep her sh*t together and try not to let her anxiety about Hurricane Florence’s approach mess with the observation. The teacher called on me multiple times during class to explain things like the Salvation Army, portable classrooms, and if “returnees” meant the same thing as refugees in the text. The actual teaching of the class was not as bad as I thought it might be (based on what I hear about Chinese teaching pedagogy towards intensive reading word by word). The teacher still did 98% of the talking, but she focused on language choice (“what words show the power of the storm?”) and article structure (“why would the author choose to break up the narration with this paragraph here?”, “Why are so many of the sentences short and elliptical? What effect does this create?”). The major concerns for me were the lack of student interaction in English (when they did work together it was in Chinese) and the fact that all the students had a reference text which included the article written in Chinese with answers to all the questions and exercises. I talked to the teacher after class and she seemed really open to working together to come up with solutions for these problems which she agrees are problems. She also seemed open to the idea that part of my job and hopes for my role on campus is to hold workshops.

All the teachers in my office (the linguistics office) are really open and friendly. I think the fact that I have relatively proficient Chinese abilities is helping me here. I hope to keep observing classes till my freshmen classes start so that I can keep building connections and relationships with the other teachers in my office and the literature and translation offices. That way, when it comes time for me to actually suggest things like workshops or MOOCs or other professional development opportunities, maybe some one will actually make time in their already overbooked schedules to hear what I and other teachers have to say.

That’s all for now!

(I know I promised to be better about pictures…. but next week really I promise… I really will be better. Below are some photos I took while on a walk out of the North gate of my campus.)

#qufu#china#shandong#qufu normal university#miismafia#uncgalumni#clsalumni#chinese#hsk#military training#exploring#travel#esl#efl#tesol#testl#expat#elfellow#elprograms#exchangeourworld#teacher

1 note

·

View note

Text

Welcome!

Hey y’all. It is that time again. I’m beginning another adventure soon!

I am going to be an English Language Fellow in at QuFu Normal University in QuFu, China! What does this mean? It means that starting in early August I will have orientation in DC, and then in late August I will leave for orientation in Beijing. I will then travel to the host university and begin teaching English at the university. In addition, I will do some teacher training workshops.

Per usual, I am in the midst of trying to figure out the visa process... this time for a work visa. This has been a rather complicated process due to the fact that before you can even apply to China for a work visa, you need to have certain documents notarized, authorized, authenticated, and legalized. Basically, it is a big waiting game right now with many roadblocks and frustration stations.

I am going to try and post regularly... but, as always I may get busy, or distracted, or maybe once I get to China the VPN doesn’t work as well as I need and I get frustrated and stop posting. Who knows?

As a reminder, all posts are my own and don’t reflect the US State Department, China, or the host institution’s opinions, thoughts, beliefs etc.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two Months into Teaching in China

Questions I still have:

What is the degree map for my students? What classes are they taking and when?

What are the course outcomes and curricular goals for my course? What are the students supposed to know at the end of this course?

What classes will they take next semester?

What, if any, exams do they need to be preparing for at the end of college?

Why aren’t there norming sessions for grading?

Why aren’t teachers that are teaching the same courses collaborating? Why isn’t there a database of resources and lesson plans from previous semesters?

What happens in staff meetings and is it something foreign teachers need to be aware of?

Why do I only see my students once a week?

Where do my students do their teaching practicums? What is expected of them?

By what criteria am I assigned the courses I am teaching?

Where is the English resource library?

How do I reserve a classroom to hold events?

Where do I put grades?

How can I encourage shy students to speak up in class?

Why do I have to explicitly tell students to buy a notebook for my class and take notes in it? Why isn’t that common sense here?

Why don’t the computers have upgraded software? Why do I have to keep using powerpoint 2003?

Why won’t the computers show PDFs?

Why do I feel like I am going to fall through the floor in the building I am in?

Why do I HAVE to stay in the computer labs.... why don’t I rebel and go to their classroom that has more space and flexibility?

Do all the local teachers hate me cause my teaching voice is so loud?

Why are there so many speech competitions?

How do I access the wifi in the office?

Why would you have a classroom that doesn’t have a whiteboard/blackboard?

Who wrote these textbooks and how do I complain more about how crappy they are while still being respectful?

Why is the lock on our office door so frustrating? Literally no one can get the door to open in under a minute.

Does anyone understand anything I’m saying ever?

When am I going to find time to make my midterm? What is it even going to be?

Do teachers get nervous when I ask to observe their classes?

Does anyone want to come observe my classes?

Where do I get business cards made?

#Qufu Normal University#Qufu#ELprograms#english language fellow#exchange our world#ELF#shandong#china#esl#tesl#tesol#tefl#efl#teaching abroad#expat#questions#teacher#teaching#teach#english#miismafia#uncg alumni#miis alumni#fulbright alumni#cls alumni

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

QuFu Week Four

(Photos 1-3) The opening ceremony last Friday was really cool. The QuFu and Rizhao campuses live streamed the ceremonies to each other, so the speakers and performances are alternating between campuses. There was a lot of reciting of Confucian Analects, some ancient poetry, the national anthem, the school song, and some sort of flag ceremony where all incoming students were passed under the school flag.

(Photos 4-8) We finally made our way to the Confucian Temple, Family Mansion, and Cemetery this week. Only about 2km away from campus, these historical landmarks are 2000 years old. Some sections had to be renovated after the Cultural Revolution due to the belief that Confucian ideals were anti-communist which led to the destruction and vandalizaition of many artifacts. Our tour guide told us that when he grew up he had never heard any of the Confucian sayings. The only idea he had about what Confucius might have said is if he was quoted by the government when they were criticizing him. Now, students from all over China come to pay homage to the “perfect sage”.

(Photos 9-10) This was my first week teaching! My freshmen students are super adorable. Unfortunately, our classes are held in computer labs that are left over from the time of Audiolingualism. I have no whiteboards or blackboards in the classrooms. Their computers are controlled by mine so they can see my screen, but I can’t have them do any research or exploration on their own. There is no internet in these classrooms. Fortunately, I’ve found ways to use the computers to my advantage despite the lack of writing space. I’ve also managed to get a portable whiteboard that I’ll start taking to classes with me.

#qufu#Qufu Normal University#shandong#china#elfellow#elprograms#fellow50#fellowfirsts#exchangeourworld#opening ceremony#confucius#temple#cemetery#first week of class#students#teaching#esl#efl#tesol#tesl#tefl#miis alumni#cls alumni#fulbright alumni#uncg alumni

0 notes