#prosaic cinema

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Il Cinema di Pasolini (Appunti per un Critofilm) (1966) dir. Maurizio Ponzi

#Il Cinema di Pasolini (Appunti per un Critofilm)#Notes from a Critofilm#Pier Paolo Pasolini#Maurizio Ponzi#John Ford#Jean Luc Godard#1960s#shorts#ours#by michi#filmedit#lgbtedit#userlenie#userelissa#userpedro#userteri#userviet#userdeforest#prosaic cinema#poetic cinema

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Clairo’s Charm & panopticism

On her third studio album Charm, Clairo offers sensitive self reflection and soft-spoken lyrics over distorted synths and piano. On the lead single Sexy to Someone, she draws from wanting someone to admire her, for the sake of having something going for her. She manages to put into words what seems to be a universal feeling. By its lively production and prosaic lyrics, this song doesn’t take itself too seriously and paints a pretty picture out of the underlying meaning.

Clairo starts off poignantly, leaving no room for interpretation: “sexy to someone is all I really want”. She repeats and nuances this motif throughout the track, which lets us in on how the sentiment actually translates in her day-to-day life. Right after the first hyperbolic line, she cuts in with a more realistic take “sometimes sexy to someone is all I really want”. As she goes on, we understand that this longing sets the tone for everything she does, it underlies her every action and commands how she moves forward. Clairo showcases what it’s like to want to appeal to others for the satisfaction of knowing you are desirable, which immediately reminded me of panopticism and the male gaze.

In the 70s, French historian Michel Foucault leaned on the notion of ‘panopticism’ as a metaphor in his analysis and critique of “the modern disciplinary society”. The panopticon metaphor has long before him been applied onto diverse contexts, ranging from interpersonal relationships, citizen’s relation to power, social media and even the relationship with oneself. This metaphor that seems so far removed from reality actually draws from blueprints for prisons in the 18th century drawn by Jeremy Betham. The idea behind the architecture of panopticons was to create a space in which the prisoners felt constantly supervised to ensure they behaved as was expected. The ideal type of a panopticon is a circular building, plus a tower in the center. The guard occupies the tower and all of the prisoners’ cells are located across the arch. Only the cells are lit, and this ensures that the guard can see all the prisoners, but they cannot see him.Given that the prisoners have no guarantee or whether the guard is watching them or not, they perpetually feel monitored. This constrains them to behave properly, regardless of the actual presence of the guard.

Feminists of the second and third wave have applied the concept onto interpersonal relationships and identity. In this frame, panopticism translates to the influence of what many have nicknamed the “ever present watcher”: feeling like someone is looking into your home through the window, an open door, a keyhole… This presence would be the embodiment of the ‘male gaze’ that has permeated our lives and conditioned us to appeal to this ever present watcher. The leading idea of this theory is that this feeling of being watched fuels women and girls’ efforts to present and carry themselves in a way that caters to the ‘male gaze’. This term was coined by film theorist Anna Mulvey in the 70s in an attempt to synthesize motifs she had noticed across several movies at the time. In her essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, she defends that lead female characters were portrayed in an unmistakably suggestive light. Whether it be unnecessary nudity, revealing costumes, panning up and down their bodies etc. the list of techniques that aim to objectify actresses and legitimize their looks as being the most important thing they bring to the film is endless. The agenda of the male gaze is to put forward the feminine ideal and demand it of girls and women. Although the portrayals in movies seem extreme, Mulvey underlines the responsibility of the societal context that allows and encourages these tropes to be produced. From this point of view, we could argue that the male gaze in film is just an exaggeration of the lens women are subject to everyday.

The male gaze, as interpreted by Mulvey, exists beyond film: it’s in music videos, magazines, ads, what have you. Its ubiquity and quasi-monopoly of women’s image in media aren’t inconsequential either. You��ll rarely meet a girl who hasn’t at some point been partial to adopting these superficial stereotypes, even if her efforts were subconscious. Catering to these insatiable fantasies is a means to making yourself more comfortable in the context of most interactions being ridden by the male gaze. Having been made aware of these expectations, women have one of two choices: conform or defy. Conforming would entail bending towards beauty standards, whereas defying would mean presenting yourself the way that you ‘truly’ want, even if this happens to align with the feminine ideal. Margaret Atwood honed in on the subconscious aspect of catering to the male gaze, underlining that it leaves no room for anyone to exist outside of its spectrum: “Even pretending you aren't catering to male fantasies is a male fantasy: pretending you're unseen, pretending you have a life of your own, that you can wash your feet and comb your hair unconscious of the ever-present watcher peering through the keyhole, peering through the keyhole in your own head, if nowhere else”. Atwood defends that the internalizing of the male gaze has pushed girls to demand the feminine ideal of themselves and become their own guard in the panopticon: “You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur”.

Panopticism and the male gaze are intrinsically two sides of the same coin; they both subject people to constant voyeurism and thus conditions us to act a certain way. It goes without saying that the consequences of not abiding to the male gaze are obviously less severe than the punishment inflicted on out-of-line prisoners. However, being illegitimate by virtue of straying from the feminine ideal does cost women opportunities, with attractiveness influencing the way people are judged. In this sense, it becomes a part of our daily lives to dress well, to put on make-up, to invest time, money and energy into healthy diets and skincare in an attempt to live up to the feminine ideal we’re entertaining and reinforcing with our every action, even if we deem that we’re doing these things for our own enjoyment.

Coming back to Clairo, in Sexy to Someone she tells us that feeling sexy/valid would motivate her to complete simple tasks, which would feel incomplete if she wasn’t admired: “it's just a little thing I can't live without”. There’s a chance this doesn’t stem from a need for validation on the singer’s part, but just a wish to be seen. This idea is solidified in the chorus, where she explains this desire “it would help me out, Oh, I need a reason to get out of the house”. Her desperation also grows as the song continues; from the chorus on, “someone” is switched out for “somebody”. Considering that “somebody” is generally used to refer to people more specifically than “someone”, this indicates that she doesn’t really care who it is, as long as she gets the satisfaction she so wants. Clairo also thinks of finding something “sexy” as appreciating it: “Sexy is something I see in everything”. Even the smallest things, “Honey stickin' to your hands, sugar on the rim”, are worth being acknowledged and cherished. In this sense, what she dubs wanting to be sexy to someone can also just mean she wants to be acknowledged and romanticized, even for the most trivial things.

As Clairo gets increasingly vague about who she seeks this admiration from, we’re led to believe she isn’t aiming to please to get something from someone, she just wants the satisfaction for the sake of it. Perhaps it’s a futile desire, but the fact that it resonated with so many listeners proves that this is a behaviour stemming from latent expectations placed upon us, and that we’re becoming both the guard and the prisoner in the panopticon.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

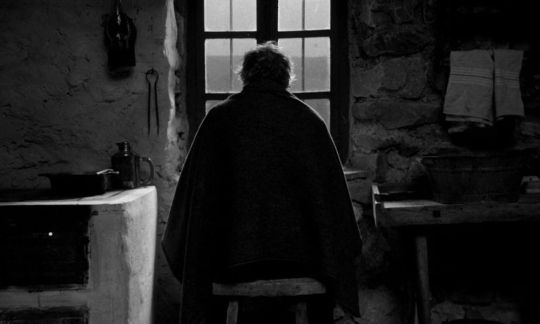

Kaos

I, 1984

Paolo Taviani, Vittorio Taviani

9/10

Realismo Mágico

Se em Padre Padrone os irmãos Taviani exploraram o canto do cisne do neo realismo italiano, naquilo a que chamei um hiper realismo, na perspectiva em que põe a nu o que de mais aviltante existe na prosaica realidade das comunidades isoladas da Itália insular, aqui o seu realismo adquire novas formas, que se aproximam do que ficou conhecido na literatura como realismo mágico e foi explorado, sobretudo na década seguinte, com enorme sucesso, no cinema italiano.

Nesse sentido este é um filme inovador, que antecipa sucessos como Cinema Paradiso ou Il Postino.

O olhar é manifestamente para um passado remoto, do virar do século XIX para o XX, e é conduzido pelo génio de Luigi Pirandelli, dramaturgo, poeta e romancista siciliano, nobelizado em 1934.

Não admira assim que este Kaos respire poesia, entre as agruras do quotidiano rural oitocentista. O sofrimento ganha aqui um sentido, o da sobrevivência e com isso, uma renovada dignidade.

Esta é uma visão positiva da dureza da vida rural siciliana, talvez decorrente da nostalgia de Pirandelli, que fica bem marcada no epílogo da obra.

Belíssimo filme.

Magical Realism

If in Padre Padrone the Taviani brothers explored the swan song of Italian neo realism, in what I called hyper realism, in the perspective that lays bare what is most demeaning in the prosaic reality of the isolated communities of island Italy, here their realism acquires new forms, which come close to what became known in literature as magical realism and was explored, mainly in the following decade, with enormous success, in Italian cinema.

In this sense, this is an innovative film, which anticipates successes such as Cinema Paradiso or Il Postino.

The look is clearly towards a remote past, from the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, and is guided by the genius of Luigi Pirandelli, Sicilian playwright, poet and novelist, awarded the Nobel Prize in 1934.

It is no wonder that this Kaos breathes poetry, amidst the hardships of nineteenth-century rural daily life. Suffering gains a meaning here, that of survival and with that, a renewed dignity.

This is a positive vision of the harshness of Sicilian rural life, perhaps resulting from Pirandelli's nostalgia, which is clearly highlighted in the work's epilogue.

Beautiful film.

1 note

·

View note

Text

There’s something about an anti-hero that appeals to us all. Why else would so many of our greatest stories revolve around a character whose behavior goes against everything we’ve been raised to believe is right?

Actually, that question probably answers itself. For many of us, the things we are raised to accept about life in the human world often feel less acceptable once we’ve gone through a few years of adult experience, which tends to put us at odds with the so-called “norms” of conformity. Naturally, this can be frustrating from time to time – and while that might not be enough to make us go “rogue” without regard law or ethics, it’s certainly sufficient to fuel our guilty fantasies.

That, along with the literary skills of Patricia Highsmith, the queer novelist who created him, is why the character of Tom Ripley has been engrossing us in various forms for nearly 75 years...Now, thanks to creator, writer, and director Steve Zaillian, Highsmith’s starry-eyed sociopath has returned in an eight-episode series – which pares the title down to the short-but-evocative “Ripley” – that debuts on Netflix April 4, and portrays his adventures with an eye toward honoring Highsmith’s intent while delivering the kind of up-front queerness that the author could never have dreamed of accomplishing in her heyday.

Not that this “Ripley” is exactly “out and proud,” though the actor who plays him – Andrew Scott (“All of Us Strangers”) – certainly is. The acclaimed Irish thespian brings his own queerness to the table in illuminating a character whose survival depends on never calling attention to himself – and though the series moves the action ahead a few years to1960, it’s still a world where any hint of “deviance” is likely to draw suspicion. That’s the last thing Tom Ripley needs; he’s a con artist, the mid-20th-century equivalent of modern-day “phishing” scammers, grifting gullible marks from his squalid, one-room New York City apartment. He’s good at what he does, an anonymous figure hiding in a sea of strangers – but when a wealthy shipping magnate tracks him down with a request for help and the offer of an all-expenses-paid excursion to Italy, he sees it as an opportunity to change his life for the better.

That opportunity, as it turns out, involves a barely remembered college acquaintance named Dickie (Johnny Flynn), whose post-graduation trip to Europe has become a years-long vacation on the Mediterranean coast from which his father – Ripley’s surprise benefactor – would like him to return. Sent on a mission to convince his old schoolmate to go home, he is instead spellbound by the idyllic seaside setting and opulent lifestyle that surrounds him – and also by Dickie himself. He ingratiates himself into the young man’s life, winning his sympathies despite some initial awkwardness. Not so easily persuaded is Dickie’s girlfriend, Marge (Dakota Fanning), whose lingering distrust must be overcome if Ripley is to enact his new master plan to claim Dickie’s life of expatriate luxury as his own.

Thanks to its source’s relative familiarity, “Ripley” makes no effort to hide the fact that its anti-hero is a shady guy; we see from the start that he’s a liar and an opportunist. What Zaillian manages to do, unlike others who have adapted the novel, is move past a clinical focus on Ripley’s psychology to give us a less prosaic – and therefore more complex – interpretation of the character. Much of this comes from a script that echoes Highsmith’s hard-boiled style by framing the story (and its protagonist) in a shadowy, amoral universe, enhanced by the stylish black-and-white treatment delivered by Robert Elswit’s cinematography, which leans into both the paradigm-challenging Euro “art cinema” from the period of its setting and the gritty chiaroscuro contrasts of film noir, setting up an instinctual understanding that this narrative, like its visuals, is composed entirely in shades of gray.

In the show’s engrossing first episode, this is a particularly effective hook, style coupling with context to underscore the bleakness of Ripley’s daily routine in New York, which is no less soul-crushing, perhaps, than the more lawful ones into which most of us are locked. Though we see that he’s a predator, it’s hard not to relate to his struggle, and by the time we get to the next chapter and meet Dickie and Marge, we’ve already entered a mindset in which easy ethical judgments become unconvincing and shallow. Our sympathies are effectively split; we’re either on nobody’s side or on everyone’s, and maybe it’s a little bit of both.

Needless to say, perhaps, this tricky transference would not be possible without the presence of a consummate actor in the title role, and Scott fits the bill beyond expectation. Though at first he reads as a bit old for the character, that notion quickly disperses – indeed, his weathered features bespeak the effects of a hard-knock life, the kind that makes a person willing to do anything to break free. More crucially, the unmistakable authenticity of his inner life is communicated with exquisite precision, engaging our empathy even as we recoil from the Machiavellian logic that guides him, and the clear conflict between his not-so-hidden feelings for Dickie and the agenda to which he has committed is made all the more stark by the ring of queer truth that underpins the performance. It’s a tour-de-force turn by an actor whose skills become more breathtaking with each subsequent role.

Fanning, whose equally adept performance provides a powerful counterpoint to Scott’s, is a strong contender for our sympathies, by virtue as much of the intelligence she brings as the peril into which it will eventually put her, and Flynn’s Dickie wears the weight and damage of his upper class status like a chain he can never quite break, making us dread the seemingly inevitable fate that awaits him even as we subliminally sign on to Ripley’s endgame with a sense of guilty (but unapologetic) satisfaction. Also notable is nonbinary actor Eliot Summers (child of former Police frontman Sting), who brings another level of queer identity into the narrative as another old acquaintance of Dickie’s that throws an unwelcome wrench into the works of Ripley’s plan.

Based on its first two episodes, “Ripley” certainly lives up to the anticipation that naturally awaits any adaptation of a high-profile story, and reasserts the queerness of an author who boldly pushed boundaries as far as censors of her time would allow. That’s more than enough to warrant staying with it until the end – and, if audience numbers warrant a renewal, through additional installments that might chronicle the less well-known escapades spun in Highsmith’s sequels. What cinches the deal, though, is the masterful performance that takes centerstage, which represents yet another escalation – and well-deserved triumph – in the rise of the talented Mr. Scott.'

#Andrew Scott#Patricia Highsmith#Ripley#Netflix#Johnny Flynn#Dakota Fanning#Marge Sherwood#Dickie Greenleaf#Steven Zaillian#Robert Elswit#All of Us Strangers#Eliot Sumner

0 notes

Text

Mia Farrow looks so intently at the screen, her eyes filled with a stern wonder. A conscious act subtly shifting the world into blackness whilst the silver screen bursts with a chromatic shiver. It is a suspension, which in the imagined focus of our protagonist the real becomes not simply the maladies of her violent husband and her deadend job but the very consumption of the fantastical as fantastical. A crossing between screen and life, which both dissipate into a tether, hooked between the exceptional desire and the prosaic. It is not death nor oblivion that’s craved but the encompassing fantasy totally consumed where thought and apparition of the moving image on the screen and the physical concreteness of sitting in that very cinema with it’s everyday familiarity are at that moment sealed together in their very now ness. Both reinforce each other and in the way the cinema becomes a cloister of secular consumption it’s religious evocations seep in the design and co-ordination of space. We could shift Mia Farrow to a church with the screen becomes the altar where the artful rendition of the testaments become that fantastical veil which our protagonist consumes. Even, The process of describing the event as consumption has biblical and far older evocations of sacrament. The illusory assurance of that which manifests in lucid reality is a deep profound connection to the thought of our very existence, the capability in consciousness to realise the shimmering edge of things coming into the world, is the possibility of true or false imaginings occurring simultaneously.

0 notes

Text

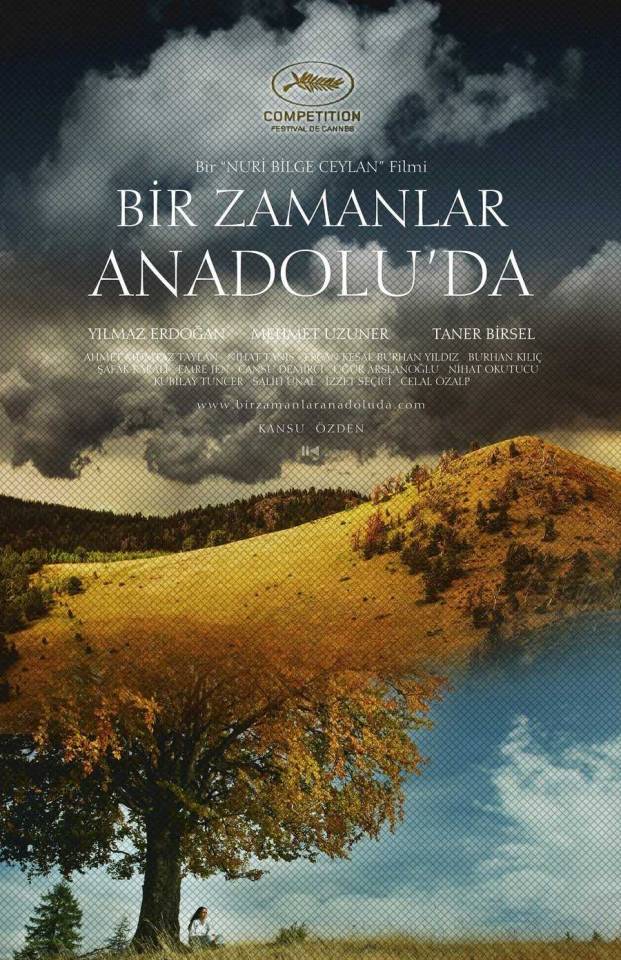

Bir Zamanlar Anadolu'da (Once Upon A Time In Anatolia) — Nuri Bilge Ceylan, 2011

Why in Anatolia?

The title does not merely reference Sergio Leone’s famous “Once Upon A Time…” trilogy but inverts it. The expansive region today that is called Anadolu by its inhabitants retains in the Turkish language the older, Hellenic toponym Ἀνατολή (Anatolḗ), which even in contemporary Greek still means “East” or “Orient” in an everyday sense. So the title is not just a fleeting reference to a well-worn literary trope, or an homage to Leone’s works or themes, but invites an interpretation of history looking, as it were, in the opposite direction entirely. This is, in fact, Once Upon a Time in the East.

This film contains a lot, and yet also a lot of nothing. In this way it conjures the real depths of our world. It dwells in the vast empty landscapes longer far longer than Leone does, but obvious fills them with none of the vibrant “newness” of the New World. Its main characters live and work in this emptiness, which is so large in comparison to them that whatever “happens” all seems slightly absurd. The film’s power lies in its movement between these vast, timeless spaces, and the small, claustrophobic present.

Here, the small spaces are police cars, containing the largely mundane existence of its reasonable, unremarkable middle-class characters, who comprise a detective unit. Immediately, this marks the fundamental difference between this film and Leone’s. While Leone’s films (and many like them) situate their subjectivity in the figures of outlaws and murderers, Ceylan’s film is grounded on the figures of law enforcement.

When we meet the detectives, they are scouring the desolate countryside to locate the body of the deceased and then, to piece together what happened to him for the official police report. This detective story unfolds so slowly however, that it quickly falls into the background and becomes an auxiliary concern to what the film actually “investigates.” The juxtaposition of what is small & brief (a flimsy “murder” narrative that gradually reveals itself to be nothing much) with what is great & timeless (the narrative of Anatolia) creates the intensity and eeriness of the work.

The little mystery that winds through the narrative only reveals itself to a patient viewer reading on this level of implication. The solution of the mystery requires no less thoughtfulness. The pacing is glacial, and the What-Is-Going-On-Here barely stays aloft as it wanders. Still, it is masterful and comprehensive, if not ‘taut’ in the way more standardized commercial media is; it holds one’s attention just above the surface of the everyday world, and nudges it toward the hollowness it senses beneath everything.

The characters presented here are complex and intense, but hold most of this energy beneath a carefully composed surfaces. There is a great deal of drama and pathos in all of the (all male) principals, but it is entirely implied with body and facial language, or in oblique, digressive narratives which are continually interrupted by their procedural detective work. The spaces it represents on this level are uncompromising prosaic, and I would say, authentically boring. To be clear, the film is itself fascinating to anyone willing to invest their attention. But it is boring in the way that life is always generally boring, lived on the surface, serving as a place for carefully controlled chatter between persons who are usually of unequal status, intelligence, and emotional sensitivity.

For reasons to consider at length, the result is a film that seems to tremble above the abyss of time and history. Specifically, what I think must be called world history—the history of the ‘world’ perceived as such, and its world-ing at the hands of man.

II. What is Anatolia?—Deep Space

In “Cinema As Philosophical Experimentation” Alain Badiou tries to make an interesting correlation between the scope and depth of a film’s landscapes (the space it accords to representation of the land, the earth, the world) and the scope of depth of its characters (the space it accords to their ethical perspective, they way they respond to problems, the decisions they make etc):

There are basically two apparent possibilities in cinema for staging great ethical conflicts. On the one hand, there is what could be called the “wide horizon form,” in which the moral conflict is set in an adventure, in a sort of epic, the Western, the war movie, or a great story. In this case, the conflict is enlarged: the role played by the setting – nature, or space, as in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, which is a metaphysical Western – allows the values to be visible against the backdrop of the immensity of nature in exactly the same way as the heroes in Westerns stand out against the horizon. This cinematic possibility amplifies the conflict.

...

The other possibility, on the contrary, is the “confined setting,” the closed circle, the little group. In this microcosmic case, everyone stands for one value or position. Cinema can also work in a stifling space, and certain cinematic techniques make it possible to flatten space…in this respect as well, cinema is capable of synthesis: it can move from enlargement to confinement, from an infinite horizon to the flattening of a confined setting.

On the one hand, this isn’t a huge insight. From the beginning of cinema, filmmakers have experimented with contrasting visual languages of “confinement” and “wide horizon” in individual works. But Badiou is pointing to a discovery of space that occurred when technological developments eventually made shooting outside of the studio and soundstage practically feasible. And I also agree that the discovery he is pointing to was indeed first typified by the eerie vastness of Westerns under the auteurship of directors like Kubrick or Leone.

However, despite their invocation of wide horizon landscapes, few movies seem to work with potential ethical power that Badiou feels they have. Once Upon A Time In Anatolia made me think of his formulations however, because it seems to do precisely this, moving between landscapes at the very limit of a super wide-angle 35mm frame, and the stifling confines of the tiny cars, filled with police dullards, crawling through these vast spaces. The subjectivity of the film is the sensation of the movement between these spaces.

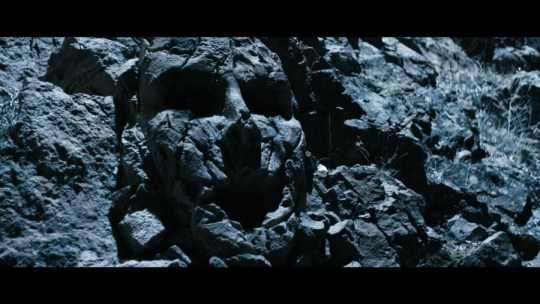

II. When is Anatolia?—Deep History

The real miracle of this film is the fourth dimension against which the film casts its figures: the ground of deep history. This is a ground of darkness and shadows. It is most directly evoked in a spooky scene where the physician character goes out into a field to relieve himself. A flash of heat lightning suddenly reveals the vast plain before us is filled with the massive stone faces of ancient, long-fallen statues, whose empty eye sockets stare back at the camera. There is no specific historical context elaborated in the narrative for these statues, but this startling moment drives home the enigmatic but deeply meaningful title of the film. Even its characters, who live in the small surrounding towns of the Kırıkkale Province, perhaps cannot quite escape the sense that they live in the middle of nowhere, and for want of a better term, nowhen.

The question raised is this: to what “time” or “place” can the phrase “Once Upon A Time In Anatolia” possibly refer to? A consideration of the absolutely unique historical identity of this place—which to be precise, is called Anadolu by its inhabitants today—proves that this question is measureless, and perhaps meaningless. This place was called Ἀνατολή by the Greek-speaking peoples who named it, who bestowed it with the literal meaning of “sunrise”, and the figurative meaning of “the East”. However, by the time this film came out in 2012, this originary “Eastern” land was revealed as the original point of conception for the entire range of what today identifies itself as “Western.”

From Anatolian soil, natural scientists from two different domains yielded a profound collective insight into “Western” culture’s understanding of “its” prehistory. These were 1) the discovery by archeologists of the world’s oldest-yet discovered architecture at the famous “temple site” of Göbekli Tepe, and 2) the cogent argument advanced by archeo-botanists, identifying the same Anatolian region as the cultivation and breeding site for the species of nutritious, readily-digestible Einkorn wheat that has constituted the backbone of Indo-European diet since, it would seem, about 10,000 B.C.E.

Collectively, this has provided some of the strongest support yet for the general theory that a movement from a hunter-gathering society to one centered on practical agriculture was what led to the formulation of proto-urban cultural centers. In addition to all of this, forensic and genetic evidence continues to accumulate suggesting that the “Ancient Greek” culture that eventually incepted the modern era originated at least in significant part from Anatolian farming societies.

The questions concerning proto-Indo European origins in the Anatolian interior ultimately leads to one central question, which seeks to identify the Urheimat or original scene of incubation for the so-called “Proto-Indo European” language. This was the language of the peoples who, from this long-lost homeland, eventually dispersed and disseminated their linguistic framework into countless thousands of derived languages and dialects, evolving collectively into the languages spoken by nearly half the world’s population today (by far, the greatest language family used today).

This is the question whose speculative horizon charges my own work, which aspires to represent the original cultural syntax that dictated the terms of conquest & modernization since the PIE people and their horses first began to sweep the plains and steppes of Europe and the subcontinent, riding far and wide in every direction—but always ultimately tending to the West. If Anatolia is not the birthplace of this linguistic revolution, it was undeniably an essential cradle for the cultural feedback loops that eventually lead to the Sumerian, Hittite, Minoan, Mycenaean flourishings et al. First the first time ever, the historical consciousness of the civilized world is beginning to move with some confidence out of the mythological accounts of origin that until now have “held place” in the absence of material evidence. It is my own belief that the excavation of these oldest layers in the archive of organized society will ultimately create more questions than answers, despite the generosity with which historians proffer their interpretations. Even though the best attempts to understand this will invariably remain unverifiable, we now live at a time when some of the original coordinates of the anthropocene’s emergence have been mapped, and the broad curves of the Ur-revolution are starting to take on some clarity.

The film Once Upon A Time In Anatolia is not ahistorical. There is a single but highly significant reference to the European Union, which comes when one character reminds the other that their work as criminal investigators & law enforcers must be held to a higher standard if the country is to find its much desired EU admission. Whether or not one agrees with these sentiments or political aspiration, the remark sounds pitifully small overdubbed onto yet another long, still shot of a vast and empty landscape. And to a viewer watching this film from outside the poetic fold of its native language, not hearing the true depths but reading translations of the Turkish in subtitles, the strangeness of the sentiment is even greater. The characters cannot help but have ambiguous feelings with regards their current role as overseerers of the original Proto-Indo-European graveyard, while they carry on the complex narratives of their own lives in a non-Indo European language and culture. Like everything in this film, these contemporary notions of place and identity, and all the tenuous narratives of “the present day” fall into the abyss of time, while life remains unresolvable and painful.

Taking all this into consideration, Once Upon A Time In Anatolia a film that correctly implies a lot beneath the surface of the present, being situated on the deepest portion of the archive. But somehow the grim reality inhabited by its main characters casts things with a kind of timeless realism. The historical processes that have left the main characters stuck in a world of dull routine and constrained aspirations are only visible in the split second that the lightning flash illuminates the ancient statues. Faced with the abyss, the uneasy realization to make is that this darkness ultimately extends beyond the conjectures of scientists and humanists alike. The question of our origins is no more likely to be resolved than the question of our destiny; the deep, wild past of humanity is no more comprehensible than its frustrating, institutionalized present.

1 note

·

View note

Quote

To Ricardo Urgoiti Hollywood, 6 August 1946 Dear Ricardo, I am hugely amazed and, I have to confess, somewhat peeved to find you read reservations and reticence between the lines of my last letter. Either you have read it completely the wrong way or I must, unintentionally, have expressed myself badly. I haven’t got a copy of that letter, but I know myself and I know my feelings towards you are absolutely cordial, so I can guarantee that, whether written by me or imagined by you, I meant absolutely no offense in that ill-fated letter. If I quoted your phrase from a few years ago it was only because I found it so convincing at that time, and it seemed a really good way to justify your silence. The proof that I liked it is in the fact I remembered it. I’m going to say it again: I am amazed you read any reservations in my letter. I see you have set off down the artistic path. That you have started to paint is already a worrying symptom: musician, painter, film-maker… I’m not surprised, and I hope that you will continue, but professionally. No hobbies. You could easily trump the local film-makers in Spain and directing would allow you to live well and pursue your other activities. Your ‘atomic’ tendencies please me less. Everything about working in this lousy technological era makes me sick. If I make my own personal contribution to the ‘disposable sub-art form’ that is the cinema, it is really in spite of myself and because I’ve never found, nor do I know how to express myself better in an alternative more longstanding and durable medium. Nuclear fission doesn’t shock me any more than steam power for example, and humanity could have got by very well without both. I don’t mean I refuse to believe in, or that I am opposed – because that would be madness – to the terrible, prosaic, technological reality of our times: I just want to note that I have no admiration or affinity for it, and that it does not interest me. As far as I’m concerned, the atom has not revealed anything new, it has just confirmed the moral depravity of our age. As an example, and symptom of this, I choose a quote from Churchill (a character as vile as Hitler, but without the aura of paranoia): ‘Divine Providence has placed in our hands, in the hands of the Anglo-Saxon nations, this terrible, destructive force. What would our enemies have done had fate placed it in theirs?’ This is from a speech he gave the day after the criminal attack on Hiroshima. Such cruel and blasphemous cynicism contains the seeds of the entire ‘social’ atomic programme we’ve subsequently seen put in practice. And so on and so forth. I’ve no more to say on this topic. Men of good faith are working on it out there. But they are the rarely heard minority with negligible influence on the people who wield the guns and the money. I’d be very grateful if you have time, to hear a few objective and honest lines about what the ardent defenders of the so-called Caudillo are saying about me in Spain. This may be a childish and masochistic interest of mine, but it is genuine. Of course, I’m not going to insist, because I imagine you won’t have time to write now, and you might well not want to. You can satisfy my unhealthy curiosity another time. Wishing you a very good trip, my friend, and until as soon as possible, with my warmest regards, Luis PS All the projects I mentioned in another letter, in spite of having signed contracts and options, are still just projects. In the meantime, I’m almost completely broke. I couldn’t even afford a trip to New York to see you and sort out a few little things at the same time. I feel I’m incompatible with Hollywood. With Mexico even more so.

Jo Evans & Breixo Viejo, Luis Buñuel: A Life in Letters

0 notes

Photo

SUBLIME CINEMA #329 - THE THIN RED LINE

Terrence Malick crafts films that are anything but prosaic - they are living, breathing poetry which people seem to either revere or hate on in equal measure. What I can say is that I’m happy he’s on a run, after having taken on such a hiatus, the mystique around the director was approaching something Salinger-esque. So there’s something really disarming about what he’s been up to recently, like he’s putting it all on the line, and has thrown all the cages wide open, with no signs of stopping. The former MIT professor has been pumping out film after film for years now, but this mid-career war movie came as a surprise - his first in decades - and it remains one of his best. A meditation on war, peace, survival, camaraderie, violence and, of course, nature.

Crazy unexpected cast too.

#cinema#film#terrence malick#the thin red line#adrien brody#jim caviezel#george clooney#john cusack#woody harrelson#jared leto#tim blake nelson#nick nolte#sean penn#john c reilly#nick stahl#terry malick#war#war movie#great film#cinematography#film stills#90s movies#great movie#movie#movies#philosophy#entertainment#films#cinephile#cineaste

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Of particular relevance for my purposes, many gay fanzines provide strong evidence of the prevalence of an objectifying eroticism in gay readings of male cinematic figures. Some gay fanzines in fact concentrate on nothing but the eroticization of the male cinematic image. Movie Buff Checklist, for example, is a gay zine devoted solely to listing and evaluating those films from the silent era to the present that contain representations of male nudity. The founding editor, Marvin Jones, describes this publication as an ‘‘erotic guide for all those moviegoers who secretly looked at Johnny Weissmuller or Steve Reeves with more than just emulative admiration in their hearts.’’ In a similar vein, another gay fanzine titled rates a wide range of male stars in explicitly erotic terms Superstars with entries such as the following on the contemporary male film star Rob Lowe: ‘‘We swooned at the brief glimpse of him at 19 as he emerged from the shower in The Outsiders. And at age 22 in his jockstrap in Youngblood discreetly covering his bulge, then the lingering shot of his oh so very ripe ass as he walks away.’’ Although such examples are admittedly prosaic, they attest to a sustained eroticization in gay spectatorial readings of the male cinematic image. They also suggest that, by placing the male image in such a different interpretive context, these processes of gay objectification radically rupture the traditional phallic semiotics of male cinematic representation.

The disorganizational impulses of queer objectifications of the cinematic male image are exemplified in a series of ‘‘film reviews’’ written by the late Boyd McDonald that originally appeared in North American gay fanzines in the eighties. These reviews proved to be so successful and generated such widespread interest that McDonald ‘‘graduated’’ to writing for more mainstream publications such as the gay magazine Christopher Street and the fashionably postmodern culture rag Art and Text. In many of his writings,McDonald engages in highly explicit erotic evaluations of the male image as it has been constructed in vintage and contemporary Hollywood films. He then uses these erotic ruminations to construct outrageously gay or otherwise aberrant readings of the various films under discussion. In a ‘‘review’’ of the 1936 film Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, for example, McDonald focuses almost solely on its male star, Gary Cooper, appraising his specular appeal with such references as, ‘‘He didn’t have a nice butt but didn’t need one, not with a face like that,’’ and engaging in highly erotic analyses of key scenes in the film, showing how, when read from a gay perspective, these scenes may be seen to ‘‘constitute a virtual comic sub-theme of cocksucking.’’ In a discussion of the Elvis Presley vehicle Love Me Tender (1956), McDonald constructs a perverse reading of the film that centers on a fantasized homosexual relationship between the Presley character and his on-screen brother played by Richard Egan, who, as McDonald sees it, ‘‘could not have remained insensitive to the beauty of Presley’s nose . . . of his full lips, of his mascara. . . and of his substantial and authoritative rear end’’.

McDonald is well aware of the transgressive dynamics of this brash style of queer erotic objectification, often playing on them to the point at which his writing assumes the status of an aggressive assault on the phallic male image."

Brett Farmer, Spectacular Passions: Cinema, Fantasy, Gay Male Spectatorships

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (Lumière, 1895)

In 1895, inspired by the current topic du jour; which was to further investigate the stroboscopic principles explored with the zoetrope, and other contemporaneous devices that exploited our human persistence of vision, Auguste and Louis Lumière, in a Promethean move, invented the cinematograph. One of the earliest, and perhaps most profound experiments helmed by Lumière was Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (Lumière, 1895), which can now be asynchronously viewed as a singular, predominantly uncorrupted cinematic representation of actuality; a documentary - the workers operate on the virtue of their own agency as they scurry to enjoy their short reprieve before the travails of the following working day - absent is the accosting, performative behaviour one may observe if it were filmed in the 21st century, as for all intents and purposes, the workers, to be prosaic, are not yet acquainted with the role of the cinema and how time, framing, and thus reality can be manipulated. Whilst in its infancy, it must be noted that photography, an antecedent of the cinema, did very much exist, so it would be dismissive to assume that the very concept of surveillance is absent from the workers comprehension - that being said, however, due to this particular document existing in such an embryonic stage of the very notion of optic surveillance, we are presented with what is a platonic ideal of actuality in flux. In spite of this, however, if we were to view these experiments as pure exemplar representations without perversion, it would only be of service to the vitiation of the autonomy of the filmmaker; Lumiere articulated his gaze by setting up the camera in a specific spatial geometry that would adhere to his idealistic vision of how reality should be represented - that is to say nothing of course of his command of when time itself should begin and end. Autonomy is granted to the workers, as they embody a mercurial urge to escape the factory, they do not, however, escape the documentary gaze -

“For the real does not wait, and notably not for the subject, since it waits on nothing from language. But it is there, identical with its existence, noise in which everything can be heard, and ready to burst over what the "reality principle" there constructs under the name of the external world.” (Lacan, 1976-77)

- subjects are freed from the bonds of time, but they are not liberated from eternity, instead, they are interned within the liminal confines of a bell jar; the subjects are rendered a mere Sisyphean gesture of recurring labour.

This proposition serves as the foundation for all forms of cinema; the idea that we are simply unable to capture what is real, and in lieu of this, we must embrace the cinema as an ekphrasis; to capture the spirit of actuality, and not its surface. This understanding of the cinema is perhaps why documentary aesthetics that blur the lines between fiction and reality (vérité) are so prevalent in popular narrative cinema; as documentary ultimately failed its inveterate conquest to be a pure representation, and leaned into the form’s more superfluous tendencies over the years. It would be unscholarly, however, to suggest this is documentary's congenital birthright to be pure; as all art is inherently a corrupted abstraction of phenomena due to the intrinsic human intervention involved in the very practice of the craft (in this case, filmmaking).

To define documentary one must simply look to define cinema itself, as both fiction and that what we conceive of non-fiction runs parallel, and thus intertwines just as our cultural understanding of perceived knowledge is similarly corrupted over time. As a prudent illustration of this fact, one can simply look to Frank Capra’s Why We Fight anti-war series (1942-1945), and his liberal re-appropriation of footage originally captured as pro-Nazi iconography from Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda film Triumph of the Will (1935). This remains testament to the fact that human history itself, by all accounts, is interwoven and unspooled with an inscrutable amalgam of fantasy and actuality, and thus it is obstinately mirrored in our cultural artefacts - they uncompromisingly articulate the ghosts of our lives, and so documentary must in term represent the spirit, and not the surface - for this is an inherently fruitless crusade.

#Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (Lumière#1895)#1895#louis lumiere#auguste lumiere#lumiere bros#lumiere brothers#define documentary#documentary#cinema#silent#film#movie

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

IN THE DRINK

by Réginald-Jérôme de Mans

My first legal drink was a vodka martini. Because I was naïve and impressionable, and those impressions were formed, of course, by James Bond - the most famous mixed drinker in the world, who made the vodka martini the most glamorous, if not the most famous, mixed drink: legendarily shaken, not stirred, with a twist. I had my first drinks prior to Bond’s heavily merchandised resurgence, so that he, his wardrobe, his drinks and their accoutrements were all at the time distinctly retro if not uncool. It was the age of Slacker. Rituals involving martini shakers seemed like unfamiliar anachronisms. In that way, perhaps they appealed the more for being so exotic.

Over the years, my tastes have matured. I prefer gin, not vodka, in my martinis; I find Bond fun, not cool, and can laugh at myself in recognizing how he influenced so much of what many of us middle-class kids originally thought was sophisticated or elegant. I still think he was right about the twist, even if I’m more likely to make it out of a lime rather than a lemon peel. I like olives, but not in my drinks. And until recently, I kept shaking my martinis despite knowing that purists say it “bruises” the gin. That is, shaking a drink made with clear or translucent liquids can make it cloudy (and supposedly dilute it with ice fragments crushed during shaking).

It took the ineffable #menswear godhead @voxsartoria, my sartorial #schreibro, to help bring me around. As always, I also needed to get my hands on a sufficiently interesting tool to stop being one. I found it in the shape of a sterling silver-bamboo-handled cocktail spoon, a midcentury design by Van Day Truex for an American jeweler. My 1949 Esquire Handbook for Hosts reminds me to use it for drinks made entirely with spirits; those made with fruit juices, nonalcoholic mixers, or cloudy liquids can still be shaken (since the result would be opaque anyway). You’re supposed to use ice cubes in stirred drinks, crushed ice in shaken ones, but I tend to ignore that rule. And indeed, my stirred martinis do taste better – crisper and rather stronger, for better or worse, since less ice gets dissolved stirring instead of shaking. (Yes Isle, you have a standing invite. Ed. note - Invite accepted) I’ve read that stirred drinks are supposed to be colder than shaken ones, but surely that must depend on how long you stir before pouring.

The bamboo got me. I’m a sucker for those odd organic shapes like coral or bamboo, even when rendered in metal instead of the real whangee of John Steed’s umbrella. The piece was part of a broader collection. But today we’re a long way from midcentury, a long way from a world in which we could claim to have a lifestyle requiring, or affording, all the patterned utensils of a collection, from cocktail to demitasse. Instead, at best most of us can only hope to salvage what we need from history’s subduction. So many wonderful, glorious things eventually get pulled under never to reappear again. At least with this spoon, stirring seems less prosaic. And it’s long enough, if not to sup with the devil, then to drink with mine.

Between the shaker and the stirrer, and with a well-enough stocked bar, you can be prepared to mix just about any drink imaginable, as rattled off by Christopher Lee in one of cinema’s great moments, his musical number “Name Your Poison” in The Return of Captain Invincible. More often than not, mine is still the martini, here on a coaster with three-dimensional images based on Kota Ozawa’s LYAM 3D, an art installation with clips from Last Year at Marienbad. The spoon rests on bamboo hashioki finished with urushi lacquer. Deflating all pretension, however, the martini glass is an Iittala knockoff I got free with a bottle of vodka. We can’t escape ourselves, after all.

Quality content, like quality clothing, ages well. This article first appeared on the No Man blog in 2016.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The unbearable heaviness and meaninglessness of existence: Turin Horse(2011)

youtube

Although Turin Horse is Bela Tarr's ninth film, the director cites it as my last film. The reason for this is telling us as follows; movies are his means of self-expression. Tarr questions the thoughts formed in his mind by transferring them to the white screen and makes us question them as well. For him, with each movie, new questions arise. However, Tarr realized that he repeats himself and annoyed by that, he presented us the Turin Horse for the last time. He has his own cinematic language and this is what makes his movies special. For instance, Tarr is a director who likes to work with the same actors and crew members because as a director, his expectation is not that the actors play, but that he really lives it. If he senses that they are playing instead of living, he stops working with them. Furthermore, he avoids using the word reality and prefer “life” instead. Similarly in the Turin Horse, he actually offers us a pessimistic cinema feast with a lot of long shots that question this “life”.

In Turin Horse, we can see this frequently, both in terms of acting and the overall structure of the movie. The camera constantly follows the actors and goes inside with them instead of a cut. These long shots takes us away from the illusion of the cinema and allows us to fully enter the life we watch. For example, we see daily routines with very long shots throughout the film, and the long these routines are in real life, the longer the motion we see on the screen. Also, if the characters are indoors, the camera never shows them from outside because it provides the sense that we have become one of them and we are trapped there as well. In fact, when we look at the film in general, what we watch is the depressive life of a father and daughter in the countryside and the boring routines that this life brings. Is this just what he want to show us, if not, what are these sequences that we watch at length?

The world was created in 6 days, and in Turin Horse, Tarr basically presents us an anti-genesis of this creation. In these 6 days, we watch the basic elements of the world disappear one by one. In the beginning of the movie the voice over explains the back story that in Turin in 1899, the philosopher Nietzsche witnessed a horse being whipped, and subsequently retreated into silence and madness. What about the horse? In Turin Horse, the director tells us what happened to the horse from a different point of view, and this point of view is the family itself who experience the same things and dependent on each other. For instance, the place where the horse was trapped is both his cave and his tomb, while the stone house is both the cave and the tomb of the father and his daughter. Just like Plato's allegory of the cave, they cannot change and reach the reality as long as they are inside the cave. The reason why the father and his daughter watches outside through window like a television can be explained by this. The outside is an altered reality for them. Tarr characterizes not only living beings but also the world of objects, and tells them from a different perspective. For example, throughout the film, not only these two people and horse, but all objects are in an unknown wait and experiences the heaviness of existence. Many archetypes and metaphors are used in the film but what are their meanings and what are the things the director want to tell us with them?

In the movie, we are intensely confronted with the wind itself and its disturbing sound. In mythology and religions we see the wind as a metaphor of god. In the Turin Horse, the wind actually symbolizes the curse and it might be interpreted as curse of the god. Just like human beings, the wind dries up everywhere it goes. The gas lamp and the fire are another archetype that is increasingly died out in the movie. This symbolizes vitality, a hope for life, but we see this archetype used as life and death in the film. Running out of fire shows us that the characters are slowly on a journey towards death. It would not be wrong to say a well is the another archetype that used in the movie. As Carl Gustav Jung mentions in his book Four Archetypes, the well symbolizes a rebirth, a change. After the day gypsies come to the well, we see that the well is dry. This shows that change and rebirth will be impossible in the film. Another harbinger of this is actually dry tree(s). We see dry trees from the first scene of the movie to the end. While the tree archetype symbolizes vitality and efficiency, its dryness is a sign of death. For instace, the family, whose everything is exhausted, decides to leave and we see them on the hill where there is a dry tree at the point where the wind prevents them.

In addition to that, one day a stranger, whose drink called “palinka”, runs out, comes to the house. This is actually one of the most important scenes of the film because in the stranger's monologue, it officially refers to Nietzschen's thoughts that God is dead and how people consume everything, which is one of the main structure of the film. We also see the stranger taking his palinka and walking away, drinking his palinka in the same frame with this dry tree because palinka is another harbinger of death coming. The reason is this Hungarian drink is preferred during birth and death times, which are important days in that culture.

Moreover, we see the callous father’s right arm and right side of his face are damaged. It’s reason might be explained as the right side of the brain which relates to the emotions. All of these archetypes actually play a big role in the director's narration of extinction. At the end of the movie, everything in their hands is constantly exhausted and living with this exhaustion is a necessity for this family. The father tells the girl and the girl tells the horse that they must eat in order to live. Even though this is one of the most prosaic things, potato, we see them eat it fast because time and life pass by. However, parallel to the horse they are not eat when they feel the despair and death.

This is exactly what the director aims to question. Despite the heaviness of existence, its necessity imposes a great burden, and exhaustion will then be inevitable. Even though Bela Tarr farewell to the cinema with Turin Horse, his cinema will continue to exist in its purest form. Thanks him once more.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

tag nine people you would like to know more about!

nine is a bad number for me, like the standalone numerical unicode form provokes itchy discomfort and i can’t even type it right now. so i will just arbitrarily tag however many people i want

last song, actually want to keep the last song i listened to a secret because it’s associated with one of the best experiences of my life, guess i can say: in love with the seesawing of her vox during the chorus, triumph soaked in cat’s gait of portato that dissolves into those sweet musette accordion sweeps. the last song before that was eldorado by aquapolis, still obsessed with the marquee moon (magazine affiliated label, not the television album) flexis. howard riley trio and pumice’s i’ll take no chance near a volcano, too.

last movie, some reels from anne charlotte robertson’s five year diary. also a ping pong of youtube clips (our loving cup!) ranging between far from vietnam and the trailers for an erotic vampire in paris and franco’s vampyros lesbos, with my boyfriend.

currently watching, moomin (been thinking about “the imp” a lot lately, just inexplicably been jammed in my imaginarium? also opening sequence speed modulation brought on in gabaergically frazzled perceptual sludge, laffs that evade recollection), the wandering woodsman and dispatches from late 2000s emo kids. trawling the pennsound cinema archive and the arthur and corinne cantrill collection on vimeo. nelson sullivan and acid house illegal rave 1989 forever and always. everyday i can only hope to ever reach the platonic form of cool embodied by the girl in the pink shirt whose dance moves are perfectly beat matched with the quiens in “quien tu te crees”

currently reading, this is more representative of a broader recent time expanse rather than whatever’s literally implied via the phrase “right now,” but women and men, assorted new narrative writers, sachiko yoshihara, david keplinger, josephine jacobsen, dana ward (need to reach out to him via twitter or email, we had a brief exchange on the former earlier this year and i consider him to be a star friend. i want to share my chintzy theories about video game metaphysics, spyro the dragon, the cultural memorially starbursted visual haecceity of at rosedale united’s cover art, candy floss junglism, and pop philosophy with him!), shampoo magazine, MAPS bulletin issues from the nineties, junglist zines and newsletters, stream of consciousness posts from lainons, vendor reviews (another literary form fermenting in its potentiality threshold), there’s a bunch of small imageboards that have cropped up in the past year or two that i am trying to play catch up with, ralee is kind of cool. maybe i will start applied ballardianism (as i relate to simon sellars and how he’s spun his protagonist, want to dendritically carry on that trail of pulp in my own poem prosaic writing) or the white shroud one of these days.

currently craving nutrition, the incipience of horizonal freedom in being able to go anywhere or do anything, ashwagandha, the ability to graduate this spring semester (of course, that’s impossible) and sort out my financial situation, a new turntable, more vintage silk scarves. ruefully, the only things eaten today: leftover nutridetritus and spirulina tablets, wish there could be more besides half an avocado. i want to start working at the wendy’s where my niece and her ex are stationed, because even though they are both younger than me, i know they would make sure nobody picks on me (sorry if that makes me sound like a doormat?). in actuality, i wish i could work at the special collections center at my uni library again. honestly i am ebullient, a shooting star shaped anemone of aspiration, and with all the plastic cherry knots that tangle into my heart, i know that i can propel myself towards the productive whirlpool that saunters laffy taffyingly into that horizon.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Repost from @robsfootsteps • NUMERO FRANCE, July 2020. Driven by a constant requirement in the choice of directors with whom he collaborates, #RobertPattinson has chosen to be in the lineage of the great actors, those who, led by their passion for cinema, are capable, by the sheer force of their will to forge a great career. At 33 years old, the face of the new Dior Homme eau de toilette has surely not finished surprising us. Robert Pattinson hardly looks out the window. Not only because the outside world scares him but because in his eyes only his inner world matters. Usually he stays in his room, watches movies or TV series. He thus managed to see four seasons of #GameofThrones in seventy-two hours, a performance that amazes him. Otherwise he reads, Michel Houellebecq, as he usually explains when his interlocutor is French. Otherwise, prosaically, the actor refers to readings indicated by the directors under whose direction he works. Since 2013, the actor has been the face of L'Eau de Toilette Dior Homme, a role of muse that delights him, and looks, in his eyes, to the perfect counterpoint to his divisive career choices. “ I had a very long relationship with Dior, it's a great experience to shoot these commercials with them. I have always appreciated the contrast between making daring films and this work. Fashion is very different from cinema, and yet both pose an equally exciting challenge. ” More at the source: https://www.numero.com/fr/cinema/robert-pattinson-portrait-interview-dior-homme-twilight-the-lighthouse-cosmopolis-the-lost-city-of-z-david-cronenberg-good-time#_ . . #numérofrance #cinema #actor #filmmaker #cinephile #diorrob https://www.instagram.com/p/CC50AMQnVvh/?igshid=1jxyy71r787ib

18 notes

·

View notes

Link

In recent disease-free years, Japan has been the world’s third largest box office market, behind only North America and China. Japanese cinemas have successfully re-opened and theatrical analysis firm Gower Street has declared the market as only the second anywhere in the world to have essentially returned to normal, meaning that weekly revenues are driven by prosaic matters such as product and local holidays, rather than extraordinary ones such as seating capacity restrictions or public health orders that close cinemas.

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Our current state of existence can be generally defined as unengaged, disembodied, and abstracted: we are historical beings who predominantly live in societies driven by ever-increasing progress. But we yearn for community and engagement with the natural world—we still feel the need to live both prosaically and poetically. Our archaic ancestors lived in tune with the transformative and regenerative processes and rhythms of the cosmos of which, as corporeal beings, they knew they were an integral part. Through mythic stories, archetypal gestures, and ritual formations, they generated form and meaning out of the uncultivated regions of chaos, bringing order and enchantment to their daily lives. We no longer experience our existence as part of a cosmos, and although our daily lives might appear more "orderly," our world is in a state of chaos, threatened by cultural conflicts and ecological disasters. We live in a desacralized and disenchanted world; yet, as my discussion of Edgar Morin's writings highlights, the human imaginary is still a producer of fantasies, myths, and magic.

Gabrielle Murray, This Wounded Cinema, This Wounded Life

#gabrielle murray#this wounded cinema this wounded life: violence and utopia in the films of sam peckinpah#edgar morin

6 notes

·

View notes