#professor Pnin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

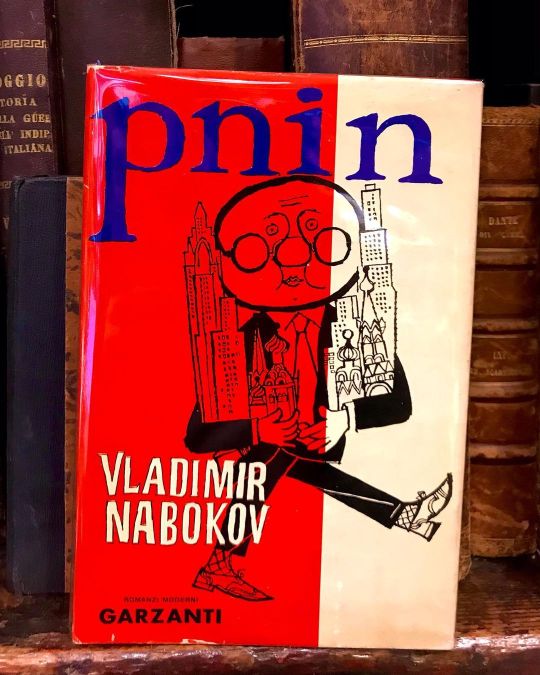

One of the best-loved of Nabokov’s novels, Pnin features his funniest and most heart-rending character. Professor Timofey Pnin is a haplessly disoriented Russian émigré precariously employed on an American college campus in the 1950s. Pnin struggles to maintain his dignity through a series of comic and sad misunderstandings, all the while falling victim both to subtle academic conspiracies and to the manipulations of a deliberately unreliable narrator.Initially an almost grotesquely comic figure, Pnin gradually grows in stature by contrast with those who laugh at him. Whether taking the wrong train to deliver a lecture in a language he has not mastered or throwing a faculty party during which he learns he is losing his job, the gently preposterous hero of this enchanting novel evokes the reader’s deepest protective instinct.Serialized in The New Yorker and published in book form in 1957, Pnin brought Nabokov both his first National Book Award nomination and hitherto unprecedented popularity.

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

one last piece of bookposting. when i got to the reference to professor pnin in pale fire i felt like "i understand why people like the mcu now"

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hier ist eine Liste der bekanntesten russischen Schriftsteller und ihrer Werke, die in deutscher Sprache erhältlich sind:

1. Leo Tolstoi (1828–1910)

📚 „Krieg und Frieden“ (Война и мир) – Eines der größten Werke der Weltliteratur, das die Napoleonischen Kriege und das Leben russischer Adliger im frühen 19. Jahrhundert beschreibt. Der Roman vereint Geschichte, Philosophie und Charakterstudien und zeichnet ein episches Bild des russischen Volkes und seiner Verhältnisse.

📚 „Anna Karenina“ (Анна Каренина) – Die Geschichte der tragischen Liebe zwischen Anna Karenina und Graf Wronski, die in den hohen gesellschaftlichen Kreisen Russlands spielt. Ein meisterhaftes Werk über Ehe, Treue und die Gesellschaft der damaligen Zeit.

2. Fjodor Dostojewski (1821–1881)

📚 „Die Brüder Karamasow“ (Братья Карамазовы) – Das philosophische Meisterwerk von Dostojewski, das sich mit Moral, Glaube, Existentialismus und der Suche nach dem Sinn des Lebens beschäftigt. Es gilt als eines der größten Werke der Weltliteratur.

📚 „Schuld und Sühne“ (Преступление и наказание) – Ein düsterer Roman über den jungen Studenten Raskolnikow, der von der Idee getrieben wird, ein „besserer Mensch“ zu werden, indem er ein Verbrechen begeht, nur um die psychologische und moralische Last zu tragen.

3. Anton Tschechow (1860–1904)

📚 „Onkel Wanja“ (Дядя Ваня) – Ein psychologisches Drama über die Frustrationen, die das Leben in einer ländlichen Umgebung und die Enttäuschung über unerfüllte Träume mit sich bringen.

📚 „Die Möwe“ (Чайка) – Ein Drama, das die Beziehung zwischen den Charakteren und ihren inneren Kämpfen aufzeigt. Es geht um die Liebes- und Karriereträume der Schauspielerin Nina und ihrer Zeitgenossen.

4. Wladimir Nabokov (1899–1977)

📚 „Lolita“ – Nabokovs kontroversester Roman, der die Geschichte eines gequälten Mannes, der eine obsessive Liebe zu einem jungen Mädchen entwickelt, erzählt. Das Werk ist ein scharfes Studium über Verführung, Eifersucht und moralische Konflikte.

📚 „Pnin“ – Ein humorvolles, aber auch tragisches Werk über den russischen Emigranten Pnin, der in den USA als Professor lebt und sich mit der kulturellen Entwurzelung und den Missverständnissen des Lebens auseinandersetzt.

5. Alexander Puschkin (1799–1837)

📚 „Eugen Onegin“ (Евгений Онегин) – Ein episches Gedicht, das die tragische Liebesgeschichte zwischen Onegin und Tatjana erzählt, während es die russische Gesellschaft des 19. Jahrhunderts und ihre Konventionen kritisch reflektiert.

📚 „Pique Dame“ (Пиковая дама) – Eine Novelle über die Abgründe menschlicher Gier und das Streben nach Reichtum durch Überlistung.

6. Maxim Gorki (1868–1936)

📚 „Mutter“ (Мать) – Ein sozialistisches Werk, das die Erhebung der Arbeiterklasse und das Leben der Proletarier im Russland des 20. Jahrhunderts beschreibt. Es ist eine Geschichte über Menschlichkeit, Solidarität und den Kampf gegen Unterdrückung.

7. Iwan Turgenew (1818–1883)

📚 „Väter und Söhne“ (Отцы и дети) – Der Roman, der sich mit der Spannung zwischen den alten und neuen Generationen in der russischen Gesellschaft befasst. Es geht um den Konflikt zwischen den liberalen Idealen der älteren Generation und den radikalen Ideen der jüngeren.

📚 „Rudin“ (Рудин) – Ein Roman über den idealistischen und unsicheren Intellektuellen Dmitri Rudin, der nach Erfüllung sucht, aber nie in der Lage ist, seinen inneren Konflikt zu lösen.

8. Boris Pasternak (1890–1960)

📚 „Doktor Schiwago“ (Доктор Живаго) – Ein epischer Roman, der die russische Revolution und den Ersten Weltkrieg aus der Perspektive des Arztes und Dichters Juri Schiwago beschreibt. Es ist ein Werk über Liebe, Verlust, Aufopferung und das Überleben in schwierigen Zeiten. Pasternak wurde für dieses Werk mit dem Nobelpreis für Literatur ausgezeichnet.

Diese russischen Klassiker sind nicht nur literarische Meisterwerke, sondern bieten auch tiefe Einblicke in die russische Gesellschaft, Philosophie und Geschichte. Die Werke von Tolstoi, Dostojewski und anderen Autoren sind tiefgründige Studien über die Menschlichkeit und die psychologischen Abgründe, die uns alle betreffen.

📖 Entdecke die tiefen und spannungsgeladenen Welten der russischen Literatur!

©️®️CWG, 26.02.2025

#RussischeLiteratur #Weltliteratur #LesenIstLeben #Bücherliebe #Dostojewski #Tolstoi #Tschechow #Nabokov #Puschkin #Gorki #Bücherwelt #Literaturempfehlung #cwg64d #cwghighsensitive #oculiauris

0 notes

Text

Now a secret must be imparted: Professor Pnin was in the wrong train. "Pnin" by Vladimir Nabokov

0 notes

Text

Now a secret must be imparted: Professor Pnin was in the wrong train.

"Pnin" by Vladimir Nabokov

Read of Pnin by Vladimir Nabokov (1953) (191pgs)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I may only be on chapter 2 but Pnin is making me begin to understand what a blorbo is

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is a trope that I love to read in fiction and especially in fanfiction: characters living the life they were meant to live, becoming the person they were meant to be, reaching the “ending” they were meant to reach all along, but via a completely new (and often more circuitous) route. This can be something a character decides in retrospect, that actually, this was what I wanted all along and it just took this journey along the twisted path to get to this realization.

This happy realization is accompanied by a profound grief over the more direct path not taken, the ghost of paths that were closed to the character by their own decisions or by circumstances outside their control. They see the ghost of the easier, more straightforward journey not taken, and they cannot ever dwell too long on the enormity of the time they had lost, the life they were robbed of, lest they are crushed by the unbearable weight of their loss.

This trope is best illustrated by this passage from Pnin by Vladimir Nabokov:

And the tiny house was so spacious! With grateful surprise, Pin thought that had there been no Russian Revolution, no exodus, no expatriation in France, no naturalization in America, everything - at the best, at the best, Timofey! - would have been much the same: a professorship in Kharkov or Kazan, a suburban house such as this, old books within, late blooms without. It was - to be more precise - a two-storey house of cherry-red brick, with white shutters and a shingle roof.

This is one of the happiest and saddest passages in the entire novel, in my opinion. Pnin has long last found a home of his own. And realizes this is exactly the home he could have had all along, if only the iron dice of history had rolled another way.

Pnin is a middle-aged professor of Russian Language at a college in upstate New York. It took him three decades of wandering and exile to achieve this life: a professorship at a university and a little suburban house near the campus. And now, after struggling for most of the novel to find a house of his own, he can finally put down roots. And in this moment of fulfillment, he imagines, briefly, how this journey could have been a straight line, a well trodden path from his upper middle class background in St. Petersburg , his bourgeois education, to a professorship and house in Kazan. But the impersonal hand of history shoved him onto a dark unknown road, fleeing persecution and war, from Russia to Turkey to Czechia to Germany to France and finally, ending up with that professorship and suburban house, but in upstate New York instead of Kazan.

This trope also makes an appearance in The Charioteer. It took seven years of exile, confused experimentations, failed relationships with other people, a world war, permanent injuries, and a series of coincidences and misunderstandings for Ralph and Laurie to end back right where it all began —in Ralph’s room, by the fireplace, the papers burning, the final moment before Ralph’s departure —so that Laurie could finally do what he should have done, what he had always meant to do: make Ralph stay. The platonic romance they should have had was stolen from them by persecution and bad luck, but they got their romance in the end, not through the well trodden path of The Phaedrus, but through the uncharted lonely road, making their own maps along the way.

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Who's afraid of the campus novel?

Ever since Vladimir Nabokov published his lovely, sad, ruthless and very funny novel Pnin, the beginning of term has been a staple scene in the campus novel. "The 1954 Fall term had begun... Again in the margins of library books earnest freshmen inscribed such helpful glosses as 'Description of nature', or 'Irony'; and in a pretty edition of Mallarmé's poems an especially able scholiast had already underlined in violet ink the difficult word oiseaux and scrawled above it 'birds'."

The details of the scene change; the first paragraph of Don DeLillo's White Noise , for instance, is saturated with late 20th-century excess: "The station wagons arrived at noon, a long shining line that coursed through the West campus... students sprang out and raced to the rear doors to begin removing the objects inside..." Or, as Malcolm Bradbury put it in the first line of The History Man: "Now it is autumn again; the people are all coming back."

This academic year begins with Tom Wolfe's latest attempt to characterise an age. And despite those who believe that, while university life will continue, the novel of academia has had its day, Wolfe has chosen a campus novel - I am Charlotte Simmons, 600 pages set at a moneyed college on the eastern seaboard - with which to do it.

From a practical point of view, of course, the attractions of the campus haven't changed much: it is a finite, enclosed space, like a boarding school, or like Agatha Christie's country-houses (the campus murder mystery being its own respectable sub-genre); academic terms, usefully, begin and end; there are clear power relationships (teacher/student; tenured professor/scrabbling lecturer) - and thus lots of scope for illicit affairs; circumscription forces a greater intensity - revolutions have been known to begin on campuses, though that doesn't seem to have happened for a while. And it's all set against the life of the mind.

"The high ideals of the university as an institution - the pursuit of knowledge and truth," says David Lodge, author of some of the more popular campus novels of the last century, "are set against the actual behaviour and motivations of the people who work in them, who are only human and subject to the same ignoble desires and selfish ambitions as anybody else. The contrast is perhaps more ironic, more marked, than it would be in any other professional milieu."

The campus novel began in America, with Mary McCarthy's The Groves of Academe (1952), Randall Jarrell's reply to it, Pictures From an Institution (1954), and Pnin (1955). (Nabokov's Pale Fire is, inter alia, a campus novel, and a murder-mystery.) "Campus" is, of course, an American word, and Lodge makes the distinction between the campus novel and the varsity novel - the latter being set at Oxbridge, and usually among students, rather than teachers, thus disallowing the joys of Zuleika Dobson, or Jill, or Brideshead Revisited; he claims Kingsley Amis's Lucky Jim (1954) as the first British campus novel, and a template.

To all the standard elements, Lodge explains, Amis added "the English comic novel tradition, which goes back through Evelyn Waugh and Dickens to Fielding"; i.e., an element of robust farce later elaborated by Tom Sharpe in Porterhouse Blue, for example, or by Howard Jacobson.

"I don't see why the campus novel has to consist of farce," says AS Byatt, who dislikes Lucky Jim, seeing it as both sexist and thoroughly anti-intellectual. "I find it baffling." She has much more time for what she calls true comedy, in Terry Pratchett's Unseen University, or in Lodge's Nice Work (1988), which she feels have more respect for a profession based on serious thought.

This is an older tradition, again. "I compare it to pastoral," says Lodge. "If you think of a comedy such as As You Like It, you get all these eccentric characters, all in one pastoral place, interacting in ways they wouldn't be able to do if they were part of a larger, more complex social scene. There's often an element of entertaining artifice, of escape from the everyday world, in the campus novel. Quite interesting issues are discussed, but not in a way which is terribly solemn or portentous."

The other, probably inevitable, addition was class. Much of the tension in Lucky Jim is between Jim Dixon and his socially superior boss; apart from the fact that she's simply prettier, the thing that binds Jim to his eventual girlfriend, Christine, is their mutual recognition of a kind of aggressive gaucheness, assumed to be more authentic than the baying, madrigal-singing Welches. But it's a fruitful collision nonetheless.

"If you're interested in the phenomenon of meritocracy, which transformed English society in the postwar period, then the university is - or was - a good place to observe it," says Lodge, who like many of his colleagues in the 60s and 70s was a first-generation university graduate. "The Kirks are, indeed, new people," wrote Bradbury in The History Man, which was published in the same year, 1975, as Lodge's Changing Places. "But where some people are born new people... the Kirks arrived at that condition the harder way, by effort, mobility and harsh experience."

These two seminal English campus novels are set in and immediately after "the heroic period of student politics", to quote Lodge's Nice Work, when new universities seemed to be appearing all over the country, change seemed possible, social mobility achievable, and promiscuity mandatory - the necessary mixing and mating of comedy, or farce, meshing nicely with the burgeoning sexual revolution and women's lib. And even though Bradbury's novel especially has a great sense of darkness, pointing, among other things, to the inequalities of unfettered sexuality at that point in time, both now read as historical novels, imbued with a quixotic hope.

But in English higher education everything is set, even in celebration, against Oxbridge, says Ian Carter, author of Ancient Cultures of Conceit: British University Fiction in the Post War Years (1990), and a professor at the University of Auckland, citing those who made the conscious choice to go to Sussex, for example, instead. The American campus novel was, he feels, better able to avoid the trap of class, "perhaps because American universities are so highly differentiated, so recognisably placeable; novels could take on a larger variety of themes without automatically having to deal with class."

Though the oil crisis of 1973 was the beginning of the end of the boom in new universities, Thatcher prompted the next great satirical subject: Lodge cites Andrew Davies's A Very Peculiar Practice, and his own Nice Work transfers the contrapuntal, mutually illuminating UK university versus US university structure of Changing Places to UK university versus UK capitalist industry.

A concurrent subject was the rise of literary theory, gently skewered in Robyn Penrose, standing for the university side of Nice Work (she is a devotee of "semiotic materialism" who believes there is no such thing as the "self", though "in practice this doesn't seem to affect her very noticeably [so] I shall therefore take the liberty of treating her as a character"). John Mullan, lecturer in English at University College London, who has written, in these pages, that the English campus novel is a fossil form, says "nobody notices, but AS Byatt's Possession [1990] is an extremely acid attack on feminist literary criticism."

So, as the university changed, British campus novels were changing in tone - angry, coruscating, debunking, or, in the case of Michael Frayn's haunting The Trick of It (1989), melancholy; and the younger generation of novelists - Martin Amis, Julian Barnes, Ian McEwan - weren't writing them. "It might be that the clutch of books that appeared in the 70s and 80s were to do with the fact that we were about to see a world vanish, maybe they were all elegies to an idea of the campus," says Howard Jacobson. "My novel [Coming From Behind, a "rotten poly" satire published in 1983] came towards the end of it - and was in a way a parody of what was already a parody, since my campus wasn't even a campus."

Jacobson argues that fear of elitism put paid to the campus novel. "Although half the country goes to campuses... everybody is embarrassed to talk about it. I think once democracy got going on the English novel, and we felt we didn't want to write anything that might upset anybody or make them feel out of it, that was the end of the campus novel. I miss it. And also, of course, campus novels were, by their very nature, funny, and funny is not in either. Campuses have become tragic places. Maybe that's all it is. They're pure wastelands, really."

"Universities are depressed," says Byatt. When institutions such as the University of East Anglia were built everything was "shiny, white and new," and because "in those days universities were intensely hopeful" you could afford farce, because "you had a solidity. Now they're terrified and cowering and underfinanced and overexamined and over-bureaucratised."

Not everyone shares this bleak view. Lodge, for one, published a new campus novel, Thinks... in 2001, and says "There's a tendency for people to sneer at the genre as if it's played out, while actually they take a good deal of interest in reading it. The fact is that universities change and societies change, and therefore there are always new fictional possibilities."

Laurie Taylor, who for 27 years has written a satirical column about universities for the Times Higher Education Supplement (and was rumoured to be the model for Howard Kirk in The History Man), concurs. This week he judged a competition for the THES that asked for the first chapter of a new campus novel. The entries were "full of campuses in which management experts and management gurus and development leaders, all speaking management jargon, are locked in a battle with the few people left who still believe that there's something more to universities than providing people with degrees that enable them to get jobs."

For this is the major battle still being fought, first joined under Thatcher, and continued under Blair: "the campus is now a site for a clash between two pretty fundamental values": the instrumental and the intrinsic, auditors versus intellectuals. Taylor cites a novel he recently reviewed, Academia Nuts, by Michael Wilding (2002), "which is very clever, in the grand tradition of Lucky Jim - but all about the impossibility of writing campus novels any more."

' "This", said Henry. "All this." There it was, their world lay all before them. The deserted common room. The chipped cups. The worn, unfigured carpet. "There's not an awful lot here," said Pawley. "I think you need more than the common room." "The university as such," said Henry. "You'd better hurry," said Pawley. "It's all being out-sourced. There's hardly anything left. The virtual university. No tenured staff. No gross moral turpitude." "I shall write about the university in decline," said Henry. "I think you might have left it too late," said Dr Bee.'

So "there are still plenty of laughs," says Taylor, "even though the laughter is now bitter instead of affectionate." But Academia Nuts is also Australian, and it is instructive to look away from England to see how the patient is really faring. Canada had Robertson Davies, now dead, and more recently Jeffrey Moore, who won the Commonwealth Best First Book award with a campus novel, Red-Rose Chain, in 2000; JM Coetzee's fierce, brilliant Disgrace (1999) is set in motion by the narrator's misdemeanors on a campus in Cape Town.

Europe never had very many, though All Souls, by Javier Marias, is "wonderful", says Byatt; in order to write a good campus novel you have to have been a university teacher, says Lodge, and in Europe that would be a betrayal of professional dignity. But in America the genre seems to have grown in stature, mutating into something important, and relevant. The increasing ubiquity of the university education is as true there as it is here (as David Mamet put it in Oleanna, "college education, since the war, has become so much a matter of course, and such a fashionable necessity... that we espouse it as a matter of right, and have ceased to ask 'What is it good for'?") and ensures a large audience less hamstrung than the British by class-consciousness.

The English department continues to provide great fodder (for Richard Russo, for example) but one of the more obvious trends has been the rise of novels satirising creative writing courses, such as Wonder Boys, by Michael Chabon. "It's like shooting fish in a barrel," laughs Francine Prose, whose National Book Award-nominated Blue Angel updates the Marlene Dietrich movie, placing it in a creative writing course in a tiny college in northern Vermont. "The minute they started allowing writers on campus they were in trouble"; of course they were going to start mocking the day job.

"Where is the novel we ought to have, about science departments?" wonders Byatt, who frankly wishes that English departments, wallowing in self-referentiality, could be discontinued; Lodge's Thinks... again of contrapuntal, bipartite structure, plays a novelist teaching a creative writing course off against a cognitive scientist; the usual farcical bed-hopping ensues, but it's a knowing nod to the genre in what is mainly a serious exploration of the nature of consciousness and the limits of AI.

This, too, is a trend established in the US, by writers such as Jonathan Lethem, whose As She Climbed Across the Table is about a physicist who discovers a hole in the universe, and a sociologist who studies academic environments; or by Richard Powers, who in Galatea 2.2 has a cognitive neurologist train a neural net to pass a course on Great Books.

Francine Prose set out to write a novel of obsessive love and ambition, "and somehow the campus seemed the perfect way to talk about those things". This seems a general discovery: White Noise, 20 years old now, is, as well as a study of the threats, and the seductive promises of science, and a celebration of family, a sustained and darkly funny engagement with the idea of death; Donna Tartt's bestseller The Secret History (also a campus thriller) takes the influence tutors have over their nubile charges to violent extremes. Power is so clearly demarcated on campus, and, increasingly, so easy to lose.

The great novel about this - though it is great about nearly everything - is Philip Roth's The Human Stain. Coleman Silk, professor of classics, is also dean when he utters one inadvisable word, "spooks"; the tumbrils of politically correct outrage roll, and he loses his job. (One of the central ironies of the book is that he is African-American, passing as white.) In the controlled space of the campus he has been king, overhauling departments, sweeping them clean, but in a word he has been forced into exile.

Exile is, in the late 20th century, itself almost a fossilised concept: where, centuries ago, you might be forced to leave a village as punishment, how many communities now are close-knit enough to function in this way? The campus, especially highly differentiated, self-sufficient American campuses such as Coleman Silk's in sleepy New England, is our alternative; banishment is no less keenly felt. And it nearly drives Silk mad.

Political correctness never made much headway on British campuses, and in fact, says Alexander Star, who edited Lingua Franca, the magazine of American academia, until it folded three years ago, the worst has been over in the US for a while now. The animating anger of The Human Stain is, therefore, dated. But it doesn't matter. For in pc, and in literary theory, and on a modern campus, Roth found a way to address some of the big cultural questions of the later 20th century.

Silk's nemesis is a young French academic called Delphine, bright, ambitious, a mistress of theory. She is also far from home, and lonely, and increasingly "destabilised to the point of shame by the discrepancy between how she must deal with literature in order to succeed professionally and why she first came to literature": that instrumental v intrinsic argument rearing its head again.

The dichotomy, for Roth, is clear: ideology is the enemy of humanism, of the human; ideology is fascism, communism - is political correctness. And so, in America at least, the campus novel has become a way to measure the state of the nation. It has taken on the elements of classical tragedy, but it is still amusing, albeit often bleakly so. No wonder Tom Wolfe wants to join in the fun.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unposted 2020

Mushrooms. Also Super Mario.

I audited a class where we read Pnin by Nabokov, and the professor really sold him. Learning about Nabokov was such a joyful experience that I commemorated it with a dress of nature and magical creatures.

Worn 11/2/20.

8 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Not all dreams in Nabokov’s work operate purely as parody, of course. When it comes to ‘genuine,’ a-Freudian ones, these can be presented either as resolutely concrete – say, the dream at the end of chapter 4 in “Pnin” (1957), where Nabokov’s hapless émigré professor sees himself once again on a desolate beach somewhere in Russia with a long dead friend, fleeing the Bolsheviks – or they can appear as nonsensical, made up of seemingly random, inchoate detail, like Klara’s laconic dream in Nabokov’s first novel “Mary” (1926): ‘[S]he seemed to be sitting in a tramcar next to an old woman extraordinarily like her Lodz aunt, who was talking rapidly in German; then it gradually turned out that it was not her aunt at all but the cheerful marketwoman from whom Klara bought oranges on her way to work’ – or, more often, they can be a combination of both. Incidentally, in the 1970 foreword to “Mary,” Nabokov expressly warns Freudians away from Klara’s dream: ‘Although an ass might argue that “orange” is the oneiric anagram of organe, I would not advise members of the Viennese delegation to lose precious time analyzing Klara’s dream at the end of Chapter Four.’ Nabokov, one may surmise, would rather have the attentive reader simply recall the bag of oranges that Klara is inconspicuously holding as we glimpse her at the same chapter’s opening. Yet if we take such dreams as miniature models for Nabokov’s creative art, we see they would maintain a certain unstated syntax, a ‘dream logic’ (or as Nabokov elsewhere insists, a ‘nightmare’ logic), but nevertheless a logic that remains non-determinist, strictly unique to the subjects that dream it, while all the while preserving a certain mystery regarding the true nature of their organisation. Dreams are not where myth is encoded and expressed, but where the particular is preserved. That said though, in the case of “Mary,” Nabokov obliquely acknowledges how Freudian ‘word association’ or paronomasia might permit another, alien logic to creep in. If this semantic slippage is a local problem in Nabokov’s first novel, by “Bend Sinister” it has become endemic. In the foreword to the later work, Nabokov informs us that ‘Paronomasia is a kind of verbal plague, a contagious sickness in the world of words,’ and that this is especially so in Padukgrad, ‘where everybody is merely an anagram of everybody else.’ Both Paduk and Krug turn out to be inter-lingual anagrams of one another, a detail which might well reveal a higher pattern, but it may also hold out the possibility that Nabokov’s avatar of free consciousness is nothing more than the recto of its negation, the verso being not simply a totalitarianism of poshlost’, but the materiality of inscription as such, that abstract level of language that is necessarily ‘common to all men.’ The rub, so to speak, is this: what the regime that governs “Bend Sinister” would confront us with is not actually an absolute determinism of meaning, but the arbitrary play of the signifier, one that threatens the intelligibility of both creative writing and dream-work, and, for that matter, the integrity of the ‘aesthetic’ as a category and the very project of psychoanalysis as such, if that be the Delphic ‘know thyself.’

Michal Oklot & Matthew Walker, ‘Psychoanalysis,’ in Nabokov in Context (p. 215–6)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

8. Recent notes

Discussing postmodernist theory, art criticism, Italian films, Russian literature, and opera after class with a favorite professor.

Tales of decadent estate parties in Providence, of magnificent chandeliers and cocktails sourced from literature. (”There was plenty of Fitzgerald, of course, and oh — you’d quite like this, Nabokov’s Pnin!)

Evening drives through Hollywood and into downtown in the dark May rain, quiet music playing as we reminisce about the past. We switch languages back and forth and don’t think anything of it.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#finishedbooks Pnin by Vladimir Nabokov. Published a year earlier than Lolita, this was actual the novel that made Nabokov's name as a writer in the US. Sadly, I had never heard of it and for some reason thought I read all his novels, so was pleasantly surprised when i saw it at Barnes and Noble along with another title I will read soon. Pnin is a bit autobiographical about a recently immigrated Russian literature professor. And if you can follow, the narrative begins where it ends on a rather witty note concerning a lecture he was stressed about. The novel also if you follow the linear notes sets up my favorite Nabokov novel Pale Fire. Also, after reading some I found this novel was Nabokov's response to Cervantes harsh treatment of the character Don Quixote. Picked that novel up recently as well and looking forward to finally reading that...

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Pnin is Nabokov’s fourth book that he wrote in English and was published in 1957. The protagonist, Timofey Pnin, is a Russian-born assistant professor in his 50s living in the United States, whose character is believed to be based partially on the life of Nabokov's colleague Marc Szeftel as well as on Nabokov himself. Pnin teaches Russian at the fictional Waindell College. . Pnin was originally written as a series of sketches, and Nabokov originally began writing Chapter 2 in January 1954, around the same time Lolita was being finalized. Sections of Pnin were first published, in installments, in The New Yorker; to generate income while Nabokov was scouring the United States for a publisher willing to release Lolita. It was soon expanded and published in book form. . Ever since I read Lolita, I’ve always had a thing for Nabokov. Despite being a more classical writer, his work remains as intellectual and relevant today as it did back then. . . . #Pnin #Nabokov #Russian #russianliterature #vladimirnabokov #americanliterature #bookreview #booksbooksbooks #booksiread #literatur #modernclassic #everymanlibrary #bibliophile #bibliophiles #blogger #bookpeople #bookrecommendation #booksbooksbooks #bookworm #fiction #readersofinstagram #readeveryday #wordsmith (at Liverpool UK) https://www.instagram.com/p/CQUDwcWrnXH/?utm_medium=tumblr

#pnin#nabokov#russian#russianliterature#vladimirnabokov#americanliterature#bookreview#booksbooksbooks#booksiread#literatur#modernclassic#everymanlibrary#bibliophile#bibliophiles#blogger#bookpeople#bookrecommendation#bookworm#fiction#readersofinstagram#readeveryday#wordsmith

0 notes

Photo

...un grande personaggio che regala tenerezza, nostalgia e melanconia...Pnin è un piccolo capolavoro...Protagonista e' il professore universitario Pnin, nato in Russia, emigrato in Francia allo scoppio della rivoluzione e poi negli anni ’40 trasferito in America ad insegnare il russo. Un personaggio indimenticabile, un vero e proprio “uomo qualunque” è un omino dolce che desta ammirazione per la dignità e il candore...è un antieroe tenero che desta compassione per il suo essere in bilico tra il nostalgico ricordo dell’infanzia nella terra russa e la fiduciosa speranza nel futuro di integrazione in terra americana, rendendolo di fatto senza radici, un dolce e svagato vagabondo... E' raccontato con una tale magia e dolcezza che mi ha incantato dalla prima all'ultima pagina. Nabokov e' stato capace di tenermi attaccato al rigo, con la tensione dell'attesa degna di un noir in una scena chiave... #libridisecondamano #ravenna #booklovers ##instabook #igersravenna #instaravenna #ig_books #consiglidilettura #vladimirnabokov (presso Libreria Scattisparsi) https://www.instagram.com/p/CKdQ46fHlZo/?igshid=1c45k94c4azv1

#libridisecondamano#ravenna#booklovers#instabook#igersravenna#instaravenna#ig_books#consiglidilettura#vladimirnabokov

0 notes

Text

I think I just found some proof (weak proof, but proof) that Pale Fire takes place in the same universe as Lolita which means that Lolita also takes place in the same universe as Pnin since professor Pnin works at the same college Shade and Kinbote work at. Also, if I’m correct about the connection, Shade and H*mbert met.

#there are already well known obvious connections in the poem section of pale Fire#but there’s also one line in the poem that isn’t mentioned#that’s too vague to be definitive but also is highly suspicious

0 notes

Text

The Trolls of Academe

Kruse is only one combatant in a guerrilla force of #twitterstorians that also includes “public intellectuals” like Cambridge classicist Mary Beard, who sees online engagement as part of her job: “If you want the public to support your work, you have to tell them why they should.” Jodi Dean, a political theorist at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, finds this position “completely naive.” In Blog Theory: Feedback and Capture in the Circuit of Drives, Dean uses the term “communicative capitalism” to describe “that economic-ideological form wherein reflexivity captures creativity and resistance so as to enrich the few as it diverts and placates the many.” Communicative capitalism relies on the exploitation of communication, just as industrial capitalism depends on the exploitation of labor, by means of “intensive and extensive networks of enjoyment, production, and surveillance.” Because it is shareability, rather than use value or meaning, that determines the circulation of an utterance online, “social media is not a terrain for the verification of truth claims or anything like that. It’s for the circulation of outrage.”

While it is obvious that the characteristics of scholarship that set it apart from other forms of content creation—nuance, complexity, dissensus, scrupulousness—play poorly on social media, the internet has already transformed higher ed in ways that would make it unrecognizable to Nabokov’s Pnin, John Williams’s Stoner, or Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim. The twenty-first-century professor must be an adept emailer, like all white-collar workers, but also a user of learning management systems and a keen navigator of databases and library catalogs, which in more and more universities exist exclusively online. Though the initial zeitgeist of massive open online courses (MOOCs) has mostly passed, the internet has enabled CUNY geographer David Harvey’s open-access “Reading Capital” video lecture series to become the best way to learn Marx even as a growing cottage industry of academic grift cashes in on the precarity of students and the academic workforce alike: from term paper ghostwriters and unaccredited degree mills eagerly siphoning loan dollars to thirsty emails from Academia.edu notifying desperate job seekers that “Someone just searched for you on Google” (an identity that can only be revealed, presumably, by upgrading to a “Premium” account at $8.25/month), delivery fees from dossier services like Interfolio that can easily amount to hundreds of dollars in a single application season, and “live webinars” from “career advisers” like Karen “The Professor Is In” Kelsky, who cynically offer advice on how to succeed in an academic market that no longer subscribes to meritocracy, if it ever did.

0 notes