#pilleth

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Owain Glyndwr and the Battle of Bryn Glas (1402): Welsh independence seems a reality...

For a country of small size and population like Wales, its people will punch above their proverbial weight in terms of national pride. Theirs is an ancient history rife with colorful characters and stories. To those unfamiliar with Wales and the Welsh people, it is not uncommon to know it is part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, or part of “England” in common parlance. Beyond that, Wales is often the unrecognized part of Britain, relatively unknown to England and Scotland and perhaps even Northern Ireland largely due to the politics there. Yet, while Wales is for statistical and some legal purposes conjoined with England, it would be wrong to assume they are or have always been one and the same.

The vast majority of Wales’s population speak English as their first and only language but in fact Wales and the Welsh people have a unique and separate people and history from England: ethnically, linguistically and culturally and this was true throughout the ages and to more varied degrees true to the present day.

Wales is the peninsula in western Great Britain that juts out from England and towards Ireland and the Irish Sea. The Welsh people are like their Irish and Scots cousins, a Celtic people (a related cultural and ethnolinguistic group) that settled the British Isles during the so called British Iron Age in the centuries prior to the Roman exploration and conquest of Britain. Celts may have not been the first people in Britain and Ireland but they became the predominant ones, intermixing and assimilating those who came before. They had a set of interrelated cultural traits, religion and languages, they would diversify over time due to geography and local circumstances. The widely recognized Celtic languages that survive today are in fact: Welsh, Irish (Gaelic), Scots-Gaelic, Cornish, Breton and Manx.

Those who became the Welsh prior to Roman conquest inhabited all of modern England, Wales and the most southern reaches of Scotland. They were a collection of tribes in various parts of the land that collectively spoke a Celtic language known as Common Brittonic and the people were collectively known to foreigners as Britons or the British, hence the modern name. Following the Roman invasions under Julius Caesar in 1st century BC and the later conquest in 1st century AD which involved a mix of alternating wars or peaceful vassalage depending on the British tribe, the Britons became more or less assimilated to the Roman way of life. Roman colonists and troops came to garrison the province of Roman Britain or Britannia, but by and large the citizenry remained ethnic Celts. These Celts carried on their own traditions but also took on Roman ones and vice versa both cultures influenced one another and forged a new group called Romano-Britons. The Romans built cities such as London in addition to roads and other infrastructure and spread their influence as far north and west as the modern Welsh peninsula and Anglo-Scottish border where famously Hadrian’s Wall was built to keep out the related but distinct Celts and precursors to the Scots known as the Picts who culture and more isolated geography in the Scottish Highlands prevented Roman conquest and assimilation. The same was true of Ireland, the Romans were aware of it and made limited commercial contact with it but did not settle it or attempt to colonize it for any lasting period of time between the 1st and 5th centuries AD. Due to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the Romans withdrew from Britain altogether in effect granting a de-facto independence.

From this the Romano-Britons split from each other and formed various petty kingdoms, a political system that was to have major implications in the coming centuries. Romano-Britons had largely converted to Christianity by the time of the Roman withdrawal. However, the Romano-Britons now had to fend for themselves from raiders from Ireland and Scotland as well as infighting amongst themselves in their various kingdoms. Though there are chronicles that suggest a high king of the Britons that unified rule, the evidence is conflicted. What is known is that in the 5th century AD, during the so called Dark Ages of Europe, the very start of the Middle Ages, groups of Germanic warriors various modern Denmark, Germany and the Low Countries arrived on British shores. Their numbers and exact reasons for being there aren’t known and are controversial in modern debate. However, the Germans are traditionally told to have been invited by a British king who sought Germanic mercenaries as troops to fend off Pictish and Gaelic raiders and suppress other rivals in Britain. The story goes that the Germans did just that in exchange for land but gradually overstayed their welcome and gradually more numbers arrived or arose through intermarriage between the Germans and Romano-British giving rise to a community that increasingly was at odds with their Celtic Briton hosts. Collectively these Germans became known as the Anglo-Saxons and began speaking a Western Germanic language that developed into Old English. They had their own pagan mythology at odds with the Celtic Christianity they encountered but in time through war and cultural assimilation, they adopted Christianity as well. While some Romano-Britons and Anglo-Saxons intermarried and became the foundations to the English people and eventual Kingdom of England.

Many Celtic speaking Britons preferred their own culture and independence and gradually were pushed back by war or other factors to the far western reaches of Great Britain. Here in isolation they developed into four related but eventually distinct dialects and cultures. Those Britons in the southwest of England in modern Cornwall, were cut off from other Britons and became the Cornish people with its own isolated dialect and later language developed from Common Brittonic. Other Britons fled to Western France and formed the Breton people on westernmost peninsula, Brittany. In the northwest of England and lowlands of Scotland a third group of Britons became known as the Cumbrians and spoke the now extinct Cumbric language The fourth and most well known of these groups moved into the western peninsula that became Wales and became known as the Welsh people, speaking the dialect of Brittonic that became known as Welsh. The word Wales or Welsh is in fact an English or Germanic designation for the Britons which meant foreigner or stranger, a bit ironic coming from a non-native people. The Welsh and indeed the Britons together referred to themselves and their land as Cymru, which means “common people” or “related people” of the British lands.

From here on out, relations between what became the Kingdom of England and Wales to the west were interrelated for better or worse. Over the centuries both Wales and England remained divided, it wasn’t until the later Viking invasions which affected the Anglo-Saxons and Welsh that a more unified polity came out of them. Firstly, the Kingdom of England unified in the wake of Anglo-Saxon resistance to the new wave of Germanic invaders called Vikings. Though there was always opposition to and from the Welsh towards the English during this time too, the Vikings were often seen as the greater threat. Following the Norman Invasion of 1066, by French descendants of Vikings from Normandy France, the Anglo-Saxon rule of England was overthrown but the Normans likewise found opposition from the Welsh. It was through the Norman presence in Wales that England tightened its grip to its Celtic neighbor to the west.

Wales for its part was never unified as one kingdom but instead remained a series of petty kingdoms or principalities most notably Powys, Gwent, Dyfed and Gwynedd. These kingdoms warred with each other and the English and this disunity allowed for the English to continue their gradual influence over them, being played off of each other as political rivals who sought total power over the whole of Wales. There was a title of King of the Britons or Prince of Wales, known in Welsh as “Tywysog Cymru” served as a sort of overlord similar to the High King of Ireland which was likewise divided between various petty kingdoms. The Prince of Wales was variously a ceremonial or nominal role or de-facto ruler of parts of most of Wales at different times, depending on the title holder, typically the King of Gwynedd, the most powerful Welsh kingdom, located in northwestern Wales. Gwyneed and Powys (eastern and mid-Wales) were the two most powerful Welsh factions and their rivalry often shaped Welsh politics as a whole. The Prince of Wales and the subordinate kings were to swear fealty to English king even if fealty to the Prince of Wales was relative.

The last native Welshman to hold the title Prince of Wales was Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, from the royal house of Gwynedd. Llywelyn was killed in battle in 1282 during the English conquest by Edward I, King of England. Upon his completed conquest the title was given to his son and heir, the future Edward II. This tradition of naming the English and later British sovereign’s eldest son and heir continues to the modern day as a result. This tradition went unchallenged throughout history except for a 15 year period at the start of the 15th century when a Welsh aristocrat in what started as a land dispute with his English neighbor would turn into a Welsh rebellion and one last attempt at a native run united Welsh nation, free and independent of England.

The name of that Welsh aristocrat and landholder was Owain Glyndwr (1359-1415?). Glyndwr had royal ancestry being descended from the royal families of the former Welsh kingdoms of Powys and Deheubarth and was a member of the Anglo-Welsh landed gentry which lived on the Welsh Marches, the borderlands between England and Wales. This class was descended from Welsh royalty and easily adapted to English rule in time, maintaining land in Wales and able to be at court in London. Glyndwr studied law in London, served in King Richard II’s army in Scotland and elsewhere and married the daughter of a fellow Anglo-Welsh aristocrat, his wife’s name was Margaret Hanmer. By most accounts Glyndwr was a loyal subject and not poised for rebellion from the start. Things changed in the 1390′s when his neighbor the 3rd Baron Grey de Ruthyn annexed land which Owain stated was rightfully of his estate. Owain petitioned the English Parliament to address the matter, this plea was ignored. Furthermore, Ruthyn intentionally withheld a royal levy to appear to military service on the Scottish border, by the time Glyndwr found out it was too late and Ruthyn who despised Glyndwr for his claims to the land was able to demonstrate to the king that Glyndwr was AWOL during military service and therefore a traitor to the crown. Meanwhile, Richard II was deposed and Henry IV was placed on the English throne instead, Ruthyn was a personal friend of the new king and placed in his ear evidence “incriminating” Glyndwr not only for his absentee status but of supposed threats to Baron’s life and alleged support for Richard II, of which there was a strong base of support in Wales.

The aforementioned events convinced the king of Glyndwr’s supposed treachery and in turn convinced Glyndwr that in order to get what he saw as rightfully his, matters would have to be taken into his own hands and that justice for a Welshman could only be found in Welsh courts under Welsh law and not under English law. In late 1400, he assumed one of his ancestral royal titles and declared himself Prince of Powys, the ancient Welsh kingdom on the Anglo-Welsh border. Glyndwr and a small band of followers launched an attack on Ruthyn’s lands and did damage to them. Word of Glyndwr’s uprising quickly spread and went quickly from a man aggrieved of his land and honor to more broadly national cause for independence. The Welsh method of fighting was in line with the traditional Celtic method of hit and run tactics and the geography of Wales played a big role in this guerilla style of warfare. The later romanticism of Glyndwr as a nationalist figure was in fact linked with his use of Wales’ topography and weather and the romantic reverence the Welsh held for the very soil on which they lived. The country was a series of mountain ranges, forested valleys and rolling hills and with the infamously rainy weather, it was difficult for the heavily armored columns of English troops to navigate, whereas the more lightly armored Welsh were more mobile and familiar with the territory able to disappear into the valleys and mountaintops with less baggage and greater speed.

Glyndwr’s first months involved hit and run tactics against English manors in the countryside, burning and looting them for supplies and with each victory more Welsh joined in the cause and later taking castles from English garrisons. Henry IV appointed his field commander in Wales, Henry Percy known as Hotspur. Percy granted an amnesty to all rebels with the exception of Glyndwr and his cousins the Tudurs (ancestors to the Tudor dynasty) in a ploy to give up Glyndwr, it failed and so the English pressed on with trying to defeat rebels in pitched battle. June 1401 saw the first major pitched battle, the Battle of Mynydd Hyddgen. Little is known of the course of the battle other than the Welsh were outnumbered by the English and their Flemish mercenaries from Flanders (modern day Belgium). The English force was defeated with heavy casualties and inspired Glyndwr’s popularity even more. Welshmen left studies at Oxford University or from military service in Scotland or France and joined the now nationalist uprising. Welsh people regardless of socio-economic status or region for the first time since 1282 were uniting under the banner of Glyndwr. Henry IV himself executed Welsh gentry suspected of aiding or supporting the uprising and them marched an army into Wales to suppress it himself. Other than burning the Strata Florida Abbey this campaign accomplished nothing, Henry IV was forced to turn back due to incessant rain and making roads and and mountain trails impassable. Some more mystically inclined English and Welsh started to question whether or not Glyndwr controlled the weather, since it seemed to be an element on his side, drawing out the rebellion.

1402 saw the passing of the Penal Laws Against Wales in Parliament. These laws forbade Welsh people from obtaining public office, denied the right to bear arms, forbade Welsh the right to own property in English towns (including English settler towns in Wales), forbade Welshmen from marrying Englishwomen and restricted the education Welsh children could receive. Englishmen who married Welshwomen were also subject to said laws. All these did was further anger the Welsh. Finally, that same year Baron Grey de Ruthyn was captured and held hostage by Glyndwr and would remain his hostage until Henry IV could pay for his ransom. Furthermore, the Welsh were crossing the border and burning English market towns in retaliation. All of these events lead Henry IV to appoint a new field commander to bring about defeat to the rebels. Henry IV and the royal treasury were continually short on funds due to ongoing larger warfare against France in the Hundred Years War. Henry’s new commander was Sir Edmund Mortimer, a nobleman with a greater claim to the throne than Henry IV, a descendant of English and Welsh nobility himself. Nevertheless, Mortimer did not press for the throne and was by all appearances loyal. He had an interest in ending the rebellion which affected his business interests in the Welsh Marches.

In June 1402 Mortimer planned to march his force into mid-Wales, force Glyndwr into a pitched battle which surely the English with heavier armor and weapons and greater numbers were certain to win. His column consisted of mostly English troops and in fact some Welsh contingents that were apparently not supportive of Glyndwr. They marched slowly and Glyndwr marched out to meet this force. On paper, Henry IV & Mortimer should have been right with 2,000 well armed troops, including Welsh archers Glyndwr was likely beaten before the battle had begun. They two armies would meet on June 22nd, 1402 at a hill called Bryn Glas near the town of Pilleth, just inside Wales near the English border. Despite the English confidence they were in fact underestimating their foe. Glyndwr, was an experienced soldier and this battle more than any other was to prove his tactical prowess. He had a smaller force made up of the famous Welsh longbowmen, archery being the specialty of the Welsh. In a culture that hunted and trained to fight in the hills and mountains of Wales, archery leant itself well to hit and run tactics in an era where gunpowder was limited and the norm was still Medieval style melees of heavily armed soldiers as was the English tradition. The Welsh longbow was large, sturdy and carried great range and the Welsh were perhaps the most accurate archers in Europe. To maximize their effect, Glyndwr placed his archers at the top of Bryn Glas hill, holding the high ground was textbook advantage in warfare. Furthermore, Glyndwr used deception to aid in his plan, he split his force, making it appear to only consist of archers atop the hill whom he commanded. This would entice the English into thinking a quick charge up the hill and melee would defeat the lightly armed archers or force them to scatter and demoralize their efforts. What the English didn’t realize was the Welsh actually hid a force of more heavily armed men-at-arms/melee infantry armed with swords, spears and other clubbing weapons to the left of the Welsh battle line, hidden in a valley on the hillside, covered by thick forest.

The battle began with the English spotting the smaller Welsh force atop the hill, the base of the hill had a small church and holy pilgrimage site fed by a spring said to have healing properties. As expected the English marched up the hill slowly but steadily with their own Welsh archers providing cover support, Glyndwr’s archers did tremendous damage though with them safely out of range from the Welsh archers supporting the English. At some point in the march up the hill, the Welsh archers in Mortimer’s army turned on the English and joined Glyndwr’s men, shooting down the English who stood by their side or in the back, whether this was predetermined at Glyndwr’s behest or done in a patriotic spur of the moment is unknown. The shocked English panicked after being hit by archers from the front, within their own ranks and from the rear, this was followed by the hidden Welsh melee force emerging from the forest to the hit the English in the side and rear, surrounded on three sides, the English scurried down the hill, Glyndwr’s men from the hill top then charged down and joined in the fray, hacking the English to death. Achieving total surprise through ambush, the English force was defeated and decimated, out of 2,000 men roughly 600 were killed, many were taken prisoner including Mortimer and the lucky few fled back to England with their lives. Local Welshwomen were described by English sources as visiting the battlefield mutilating the dead English as payback for English campaigns and atrocities in years past. The Welsh left the English bodies unburied and to rot in the sun for months, leaving a stench of death permeating the air over a widespread area for months afterward, an added insult to the English invader.

Bryn Glas clearly demonstrated Glyndwr’s tactical prowess and was probably jis finest battle from a tactical sense, it wasn’t his last by any means. Indeed, in the aftermath support for the Welsh rebellion furthered and the ranks of his army grew. He now sought to take English castles, no easy task given a lack of proper siege equipment and artillery. Furthermore, Henry IV was in no hurry to ransom out of fear that Mortimer with a greater claim to the throne might usurp him. Indeed Mortimer was married to Glyndwr’s daughter Catrin and would betray the English crown by joining the Welsh rebels and fighting for their cause. In the coming years, the rebellion grew to the point where England lost basic control of the whole of Wales, save for certain garrisoned castles and towns which were now the focus of Welsh sieges. In this air of de-facto independence, Glyndwr would in 1403-1404 capture Harlech Castle on the Welsh coast and in the town of Machhynlleth be crowned Prince of Wales, being truly the last native Welshmen to have the title declared by the Welsh nobility. He attempted to run a government though the war was still ongoing. He declared the restoration of traditional pre-English Welsh law, establishment of two national universities, a separate Welsh Church and Parliament. He also established foreign relations with the Irish, Scots and the French, hoping to get military aid from all and present a united Celtic front against England with French aid. Furthermore, he conspired with Mortimer and his other former rival Hotspur Percy and his father, also Henry Percy to divide England and Wales between them. Southern England would go to Mortimer, the North to the Percys and a greatly enlarged and independent Wales would go to Glyndwr.

Here Glyndwr was at his zenith, unrecognized as a ruler by the English but in defiance he bested them in battle time and again and ambitiously was ruling his ancestral land in his name and even getting foreign recognition. He had given hope to his people, Would it last? Time would have to tell. The figure of Glyndwr however endures, modern Welsh nationalism was born with him and he appealed to his people’s romantic and even mystical traditions of a singular Welsh figure, like King Arthur of legend who would drive the English from Britain and restore Welsh and indeed Celtic British independence...

#wales#welsh independence#welsh nationalism#15th century#owain glyndwr#welsh triads#arthur#military history#bryn glas#pilleth

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

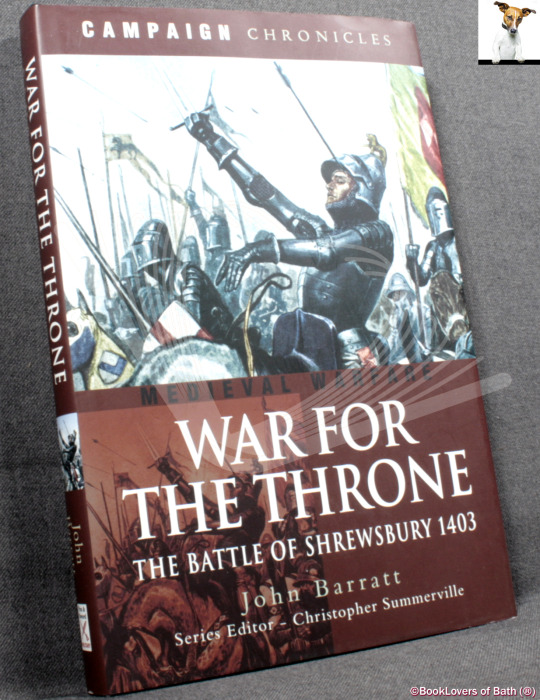

War for the Throne: The Battle of Shrewsbury 1403 -::- John Barratt

War for the Throne: The Battle of Shrewsbury 1403 -::- John Barratt

War for the Throne: The Battle of Shrewsbury 1403 -::- John Barratt lands on the shelves of my shop.

Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2010, (First Edition) Hardback in dust wrapper.

Contains: Black & white photographs; Chronological tables [1]; Glossary;

From the cover: The opening years of the fifteenth century saw one of the most bitterly contested political and military struggles in the history…

View On WordPress

#978-1-848-84028-7#alnwick castle#battle of shrewsbury#books in the campaign chronicles series#books written by john barratt#britain history#cover art by jon wilkinson#england kings#first edition books#henry iv#homildon hill#owain glyn dwr#pilleth#warkworth castle

0 notes

Photo

Post Office Life Insurance Reviews in Pilleth #Post #Office #Life #Cover #Review #Pilleth https://t.co/nptHxlnFdr

Post Office Life Insurance Reviews in Pilleth #Post #Office #Life #Cover #Review #Pilleth https://t.co/nptHxlnFdr

— Best Life Insurance (@ukbestinsurance) January 23, 2020

1 note

·

View note

Text

New photos featuring #medieval churches of #Powys, #Wales plus my thoughts on the cottage and its bats!

Wales has always been a favourite place of mine to visit and this latest trip was to a little place called Whitton in Powys. Why there I hear you ask? Our weekend break this time was centered on an available cottage at short notice and at a good price. We found the most quirkiest little cottage we've stayed in yet. Once booked, we sought out what was of interest near by to visit. Scroll to the end of the post to read my thoughts about Riverbank Cottage and the bats.

St Mary's Church in Pilleth, Powys

117 St Mary's Church in Pilleth St Mary's Church in Pilleth is approximately a 10 minute drive from Riverbank Cottage. I've read here that it dates from the 14th century and lies close to the Battle of Pilleth. It's a beautiful medieval church that sits on the hillside overlooking the fields below and when me and Mark visited, Housemartins were nesting above the windows. Inside St Mary's Church, the bell tower was my favourite place and when I saw Mark's reflection appear in the framed picture on the wall, I couldn't resist taking the image below. If you like visiting medieval churches, St Mary's Church has to be on your list.

GP92 Bell Tower Ghost

St Andrews Church in Norton, Powys

Although not medieval, St Andrews Church in Norton, Powys has been rebuilt in the Victorian Gothic style and I adore Gothic architecture. I always find that it looks great against the sky and St Andrews Church on the day of our visit, didn't let me down. We met a lovely gentleman inside who told us about the work required to fix the plaster and how they are bringing the community into the church by opening the doors so that the church can be used like a village hall. The graveyard was beautiful with wildflowers gently swaying between the headstones and the sky was spectacular. The clock tower was calling me.

116 St Andrews in Norton

GP94 St Andrews Clock Tower

St Michaels Church in Cascob

St Michael's Church in Cascob is well worth seeking out for it's simple charm and beauty. To reach St Michael's Church, which is approximately 5 miles to the south-west of Knighton, you have to travel down a long quiet road that has the odd farm that can be spotted from the car. Once there, you will see the most amazing Yew Tree that is reportedly 2000 years old, but it's the beauty of this place and the solitude that I really noticed. When leaving and travelling back down the isolated road, I thought about who would have used the church centuries ago. Obviously it would have been farmers, but how many miles would they have traveled for and how?

118 St Michaels Church in Cascob

119 Cascob Yew Tree

Riverbank Cottage, Whitton

If you would like to follow in mine and Mark's footsteps and see these beautiful churches, I can recommend Riverbank Cottage to stay in due to it's quirkiness, which dates back to approximately 1850. The cottage has everything you need, but absolutely no mobile phone signal, which can be a blessing if you want a complete break from it all. The other great feature of this cottage was the proximity to Radnor Forest, right on the outskirt and the little balcony area overlooking the River Lugg. We took my Bat o Meter to listen to the local bats and we detected possibly three different species. It was great with them flying above our heads and we sat there for hours in the dead of night as there's no street lighting either. I might have to return for Halloween! Click to Post

#Cascob#Church#Churches#Medieval Church#Norton#Pilleth#Powys#St Andrews Church#St Marys Church#St Michaels Church#Wales

0 notes

Text

I've been to Pilleth (the Other Great Longbow Battle) and you can really see the layout of where each army was as you stand on the hill.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Promotional Video Production in Pilleth | Showreel # #Pilleth...

Promotional Video Production in Pilleth | Showreel # #Pilleth https://t.co/N2bDNjmsRp

Promotional Video Production in Pilleth | Showreel # #Pilleth https://t.co/N2bDNjmsRp

— Showreel (@showreeluk1) August 7, 2020

from Showreel https://ukshowreel.tumblr.com/post/625809727329304577 via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

Promotional Video Production in Pilleth | Showreel # #Pilleth https://t.co/N2bDNjmsRp

Promotional Video Production in Pilleth | Showreel # #Pilleth https://t.co/N2bDNjmsRp

— Showreel (@showreeluk1) August 7, 2020

0 notes

Photo

School Playground Games Markings in Pilleth #Play #Area #Markings #Pilleth https://t.co/asPVVpXGkQ

School Playground Games Markings in Pilleth #Play #Area #Markings #Pilleth https://t.co/asPVVpXGkQ

— Playground Games (@playgroundsgame) July 3, 2018

0 notes

Photo

The Satoshi Revolution – Chapter 3: Civil Liberties and Central Banks (Part 3)

Featured

The Satoshi Revolution: A Revolution of Rising Expectations. Section 1 : The Trusted Third Party Problem Chapter 3: Trying to Undo Satoshi by Wendy McElroy

Bad News: Civil Liberties and Central Banks (Chapter 3, Part 3)

If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained, you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle. — Sun Tzu, The Art of War

Governments are creating their own cryptocurrencies through the central banking system. Understanding the coming consequences to free-market cryptocurrency requires an understanding of the relationship between governments and central banks.

Background Context

A central bank is a clearing house for national currency; it is a middleman for a nation’s financial policies. It enjoys monopoly control over the production and distribution of a nation’s money and credit. Typically, it also sculpts monetary policy through mechanisms, such as setting interest rates, and it polices member banks.

Even when a central bank is nominally independent, as the U.S. Federal Reserve System is said to be, it is entirely dependent upon government for the legal privileges that empower and define it. Yet, people continue to insist the two institutions are independent. This confusion serves the purposes of government and banks at the expense of average people.

The Case Against the Fed is Murray Rothbard’s attack on the Federal Reserve. He explains that, even though “’independent of politics’ has a nice, neat ring to it,” there are two problems with the claim. First, it is a sleight-of-hand. Second, the much-vaunted autonomy of the Fed is actually a government-grant of immunity that does not preserve monetary integrity but threatens it.

To focus on the second point: The Fed operates with considerable independence. Autonomy is desirable, Rothbard observes, for “private, or market, activities [which] should be free of government control, and ‘independent of politics’ in that sense.” It is entirely different, however, to say that “government should be ‘independent of politics’.” The private sector is accountable to customers, competition, stockholders and other market forces. A government agency is generally responsible only to public opinion and to Congress. But an autonomous government agency loses all such accountability and operates as a rogue.

Rothbard continues:

[I]f government becomes “independent of politics” it can only mean that that sphere of government becomes an absolute self-perpetuating oligarchy, accountable to no one and never subject to the public’s ability to change its personnel or to “throw the rascals out.” If no person or group, whether stockholders or voters, can displace a ruling elite, then such an elite becomes more suitable for a dictatorship than for an allegedly democratic country. And yet it is curious how many self-proclaimed champions of “democracy,” whether domestic or global, rush to defend the alleged ideal of the total independence of the Federal Reserve.

Government protects the fiefdom in its midst because the Fed benefits the political structure on a bipartisan basis. The central banking system is a vehicle of monetary control and funding for anyone in power. Funding is especially important. According to an August 15, 2017 article in the Financial Times, “Leading central banks now own a fifth of their governments’ total debt.” The six key central banks “that have embarked on quantitative easing over the past decade — the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan and the Bank of England, along with the Swiss and Swedish central banks — now hold more than $15tn of assets according to analysis by the FT of IMF and central bank figures, more than four times the pre-crisis level.” That’s a staggering amount.

[Note: Quantitative easing occurs when a central bank purchases securities, usually government ones, in order to lower interest rates and increase the money supply. This artificially fuels the economy by driving down borrowing costs for households and businesses.]

The Lesson of History

Governments and central banks are not independent. Collusion between them is inherent and intimate, not accidental, as history reveals. The Swedish Riksbank is widely regarded as the first central bank. Opened in 1668, Riksbank was technically a private, joint-stock bank, but it functioned under strict royal authority; the king mandated the rules of operation and appointed the bank’s management. The entire purpose of the Riksbank was to lend funds to the government and to be a clearing house for commerce.

In 1694, the Governor and Company of the Bank of England was created by Royal Charter. It is the model upon which most modern central banks draw. The Bank of England emerged because King William III’s credit was drek. The joint-stock company provided a path for the king to rake in the public funds that allowed him to continue waging war. William III was at military odds with Ireland, Scotland and North America, who were in various stages of rebellion. More importantly, however, the Nine Years’ War (1688-1697) with France had devastated England’s navy. But no financial institution would risk the £1.2M required to reconstruct it.

Accordingly, English law established artificial incentives to loan money to the king. Those who did so became incorporated as joint owners of the Bank of England. Lenders gave the king cold cash in return for which they received exclusive access to the government’s finances. The bank also became the only limited-liability corporation allowed to issue banknotes, which it did, using government bonds as collateral. In other words, the Bank of England extended a loan to a recipient no one else would touch; it acquired bonds from the king; based on the bonds, the bank then issued money, which was lent out again. Without legal privilege, the central bank would not have attracted any investors or finance. With legal privilege, the £1.2M was raised in less than two weeks.

Government and central banks are two hands washing each other.

On Civil Liberties and Central Banks

Financial gain is not the only motive for herding people toward the trusted third parties of central banks. There is also a hunger for power. War is the ultimate flexing of power through which governments maintain, assert and expand themselves. War requires money – a lot of it. The question is how to get enough.

There is outright theft. The economy can be looted but that means looting individuals who tend to object. Sometimes, they object dramatically, as in 1215 with the Magna Carta. A contemporary commentator publicly warned the monarch King John, “With occasions of his wars he pilleth them [the people and nobles] with taxes and tallages unto the bare bones.” John was forced to sign the Magna Carta, presumably under threat of death. He pledged to cease pillaging the economy to pay for his wars.

When a government declares war it does so on at least three fronts: the opposing government, the people of the opposing nation, and the dissenters within its own territory. Some internal dissenters agitate on principle but their ranks are swelled by those who object to the taxes and the other civil liberty violations committed in the name of war. For government, the tricky question is how to extract as much money as possible without incurring a backlash. How to sidestep the tendency of people to assert their civil liberties and resist?

An underdiscussed aspect of central banks and currency manipulation is their impact on civil liberties. Direct taxes, confiscations, and regulations are visible. People understand a hand that reaches directly into their pockets or throws them in jail for refusing to pay the “war” portion of their taxes; they will disobey. By contrast, confusing monetary policies are invisible at a non-transparent bureaucracy level. People do not understand or immediately feel the impact of quantitative easing, for example. It does not prompt them take to the streets with picket signs. Instead, people go about their daily lives and simply assume the burden of an indirect tax they do not quite understand.

To restate the point through a parallel: inflation is a hidden tax that people tolerate even though they would rebel against a direct one; the inflation is comparatively unseen and not understood. Equally, people who would protest a pro-war tax tolerate central bank policies, without which the waging of war would be impossible. Those who are anti-war should call, first and foremost, for the dissolution of the Federal Reserve and all other central banks. But the role of central banks in financing war is unseen and, so, the government sidesteps the need to confront anti-war activists. People do not assert their civil rights because they do not know those rights are being violated. The role of central banks in social control remains unrecognized.

Conclusion

Average people cannot escape being victimized by the partnership of government and central banks. That is, they could not escape before the advent of Bitcoin. Unfortunately, government is now awake to the threat that cryptocurrency poses to its financial and social control. It is turning to the time-tested mechanism of monetary control: central banks. And central banks will be trying to do what has worked for centuries: monopolize the production and distribution of currency.

The process begins by a government issuing its own crypto through a central bank. It has begun.

[To be continued next week.]

Thanks to editor/novelist Peri Dwyer Worrell for proofreading assistance.

Reprints of this article should credit bitcoin.com and include a link back to the original links to all previous chapters

Wendy McElroy has agreed to ”live-publish” her new book The Satoshi Revolution exclusively with Bitcoin.com. Every Saturday you’ll find another installment in a series of posts planned to conclude after about 18 months. Altogether they’ll make up her new book ”The Satoshi Revolution”. Read it here first.

Article Source

The post The Satoshi Revolution – Chapter 3: Civil Liberties and Central Banks (Part 3) appeared first on Bitcoin E-Gold Rush.

0 notes

Link

via Twitter https://twitter.com/rubberplaybark

0 notes