#pilgrimage centre

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

youtube

KALA BHAIRAVA SHRINE DURBAR SQUARE KHATMANDU NEPAL

#youtube#Hindu Shrine#Hindu Temolw#Pilgrimage Centre#Kala Bhairav#Durbar Square#Hindu God#Fierce Manifestation Of Shiva#Khatmandu Nepal

0 notes

Text

I thought today - the TV show I'd really like to see is one about a medieval monastery.

You could have all kinds of characters: the pious guy who joined because he wanted to serve God, the son born out of wedlock sent there to cover up his parents' shame, the geek who wanted to study Latin but couldn't afford to go into university, the former knight sick of violence and afraid for his soul... Plus monasteries were centres of pilgrimage and places where criminals could take refuge, so we can have a lot of characters who crop up for a few episodes and leave.

Some plotlines I thought of:

Our relics aren't bringing in the pilgrims the way they used to - what do we do?

A women fleeing an abusive marriage has taken shelter in the monastery - how will the brothers respond to having a women in their midst?

One of the monks wants to leave - will the abbot accept or not?

A murderer has taken refuge in the abbey, and the abbot decides to try and save his soul - what will happen?

People are coming to the monastery for food during the famine, but the monastery is itself short of food - how will this be dealt with?

War has broken out between two local lords, and the monks attempt to broker a treaty - will it work?

I've already mentioned some reasons why I think this setting would lend itself to television, but I'd also love to make it for two other reasons:

Get people to understand how weird medieval religion could get, but also that, within its own frame of reference, it was a reasonable and consistent belief system.

Show people that the Middle Ages consisted of more than just muddy people stabbing each other and burning scientists at the stake.

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

“A Palestinian home in the Old City of Jerusalem decorated with Hajj painting - marks indicating Muslim inhabitants have made a pilgrimage. The house is painted with red and green 'spots' two of the colours of the Palestinian flag, the other colours being white and black. The drawing centre left are of the Kaaba (Cube) in Mecca and the Al Aqsa Mosque (Dome of the Rock) in Jerusalem and possibly the Ibrahimi Mosque in Hebron. Jerusalem, April 1982.”

Photographed by Homer Sykes.

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

one of my absolute favourite tiny details is cousland’s nan insisting the warden start the telling of a childhood story, and instead of, i don’t know, “once upon a time”, cousland’s cultural go-to is before our fathers’ fathers came down from the moutains. cousland has chantry tutors but at their nanny’s knee it was alamarri folk tales, not andraste and the wyvern. i think that’s so interesting and it’s one of the jumping-off points for my take that highever let andrastianism colour its culture and traditions more so than change them, in contrast to a centre of pilgrimage and of royalty like denerim, which is more closely interlinked with, and perceived by, andrastians outside ferelden’s borders. cousland to me is always saying some slightly off brand stuff they don’t realise is weird (read: heresy) while alistair and wynne raise eyebrows at each other

#cousland: let’s pay respects to the spirit inside connor before we try anything#alistair: the demon??#cousland: it’s still one of the maker’s first children isn’t it?#alistair: well i mean yes but—#cousland: you lay a space for the spirits on feast days you don’t ask what kind of spirit takes it#alistair: what are you TALKING about#warden cousland

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Interview: Medieval Christian Art in the Levant

Medievalists retain misconceptions and myths about Oriental Christians. Indeed, the fact that the Middle East is the birthplace of Christianity is an afterthought for many. During the Middle Ages, Christians from different creeds and confessions lived in present-day Lebanon, Syria, Israel, and Palestine. Here, they constructed churches, monasteries, nunneries, and seminaries, which retain timeless artistic treasures and cultural riches.

James Blake Wiener speaks to Dr Mat Immerzee to clarify and contextualize the artistic and cultural heritage of medieval Christians who resided in what is now the Levant.

Dr Immerzee is a retired Assistant Professor at Universiteit Leiden and Director of the Paul van Moorsel Centre for Christian Art and Culture in the Middle East at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Saint Bacchus Fresco

James Gordon (CC BY)

JBW: The largest Christian community in what is present-day Lebanon is that of the Maronite Christians – they trace their origins to the 4th-century Syrian hermit, St. Maron (d. 410). The Maronite Church is an Eastern Catholic Syriac Church, using the Antiochian Rite, which has been in communion with Rome since 1182. Nonetheless, Maronites have kept their own unique traditions and practices.

What do you think differentiates medieval Maronite art and architecture from other Christian sects in the Levant? Due to a large degree of contact with traders and crusaders from Western Europe, I would suspect that we see “Western” influence reflected in Maronite edifices, mosaics, frescoes, and so forth.

MI: Especially in the 13th century, the oriental Christian communities enjoyed an impressive cultural flourishing which came to expression in the embellishment of churches with wall paintings, icons, sculpture, and woodwork and the production of illustrated manuscripts, but what remains today differs from on one community or region to another. In Lebanon, several dozens of decorated Maronite and Greek Orthodox churches are encountered in mountain villages and small towns in the vicinity of Jbeil (Byblos), Tripoli, the Qadisha Valley, and by exception in Beirut, but only a few still preserve substantial parts of their medieval decoration programs. Most churches fell into decay after the Christian cultural downfall in the early 14th century when the pressure to convert became stronger. While many church buildings were left in the state they were, others were renovated in the Ottoman period or more recently.

Christian Pilgrimage in the Middle Ages, c. 1000

Simeon Netchev (CC BY-NC-ND)

Remarkably Oriental Christian art displays broad uniformity with some regional and denominational differences. Cut off from the East Roman (Byzantine) Empire after the Arab conquest, it also escaped from the Byzantine iconoclastic movement (726-843 CE), which allowed the Middle Eastern Christians to develop their artistic legacy in their own way. An appealing subject is the introduction of warrior saints on horseback such as George and Theodore from about the 8th century. The West and the Byzantine Empire had to wait until the Crusader era to pick up this oriental motif and make it a worldwide success. But the borrowing was mutual. Mounted saints painted in Maronite, Melkite (Greek Orthodox), and Syriac Orthodox churches would increasingly be equipped with a chain coat and rendered with their feet in a forward thrust position, a battle technique developed within Norman military circles. Moreover, the Syrian equestrian saints Sergius and Bacchus were rendered holding a crossed ‘crusader’ banner, an attribute usually associated with Saint George, as if they were Crusader knights. Apart from these examples, there is little evidence of Oriental susceptibility to typically Latin subjects. We find Saint Lawrence of Rome represented in the Greek Orthodox Monastery of Our Lady near Kaftun, but this is exceptional.

Normally, one cannot tell from wall paintings in Lebanon to which community the church in question belonged. They all represented the same subjects and saints whose names are written in Greek and/or Syriac and may have recruited painters from the same artistic circles. Regarding architecture, the last word has not been said on this matter, because the documentation of medieval Lebanese church architecture is still in progress. Nevertheless, the build of some churches undeniably displays Western architectural influences; for example, the Maronite Church of Saint Sabas in Eddé al-Batrun is even plainly Romanesque in style.

JBW: Following my last question, is it then correct to assume that the Crusader lands – Edessa, Antioch, Tripoli, and Jerusalem – were quite receptive to Eastern Christian styles?

MI: That is difficult to tell because there is next to nothing left in the former County of Edessa and the Principality of Antioch. We do have some decorated churches in the former Kingdom of Jerusalem (Abu Gosh, Bethlehem), and here we see a strong focus on Byzantine craftsmanship and Latin usage. Apart from the preserved church embellishment in the Lebanese mountains, there are some fascinating, stylistically and thematically comparable instances across the border with Syria.

Saint Peter in Sinai

Wikipedia (Public Domain)

Although situated within Muslim territory, the Qalamun District between Damascus and Homs stands out for its well-established Greek Orthodox and Syriac Orthodox populations; and from the 18th century onwards, also Greek Catholics and Syrian Catholics. Interestingly, stylistic characteristics confirm that indigenous Syrian painters were also involved in the decoration inside Crusader fortresses such as Crac des Chevaliers and Margat Castle in Syria. It was obviously easier to contract local manpower than to find specialists in Europe.

JBW: The Byzantine Empire exuded tremendous political, cultural, and religious sway across the Levant throughout the Middle Ages; a sizable chunk of the Christian population in both Syria and Lebanon still adheres to the rituals of the Greek Orthodox Church even today.

MI: Leaving aside the cultural foundations laid before the Arab conquest, the contemporary Byzantine influences can hardly be overlooked. In the 12th and 13th centuries, itinerating Byzantine-trained painters worked on behalf of any well-paying client within Frankish and Muslim territory, from Cairo to Tabriz, irrespective of their denominational background. This partly explains the introduction of some ‘fashionable’ Byzantine subjects and the Byzantine brushwork of several mural paintings and icons. Made in the 1160s, the Byzantine-style mosaics in the Church of the Nativity at Bethlehem are believed to be the result of Latin-Byzantine cooperation at the highest levels; they exhale the propagandistic message of Christian unity. In 1204, however, the Crusaders would conquer Constantinople and substantial parts of the Byzantine Empire. The Venetians brought the bounty to Venice, and, surprisingly, also to Alexandria with the consent of the sultan in Cairo, intending to sell the objects in the Middle East. So much for Christian unity…

The Eastern Greek Orthodox Church has its roots in the Chalcedonian dispute about the human and divine nature of Christ in 451, which resulted in the dogmatic breakdown of the Byzantine Church into pro- and anti-Chalcedonian factions. Like the Maronites, the Melkites (‘royalists’) remained faithful to the former, official Byzantine standpoint, except for their oriental patriarchs in Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem were officially allowed autonomy without direct interference from Constantinople. On the other hand, the Syriac Orthodox became dogmatically affiliated with the identically ���Miaphysite’ Coptic, Ethiopian, and Armenian Churches. To complicate matters even more, part of the Greek Orthodox and Syriac Orthodox communities joined the Church of Rome in the 18th century. This resulted in the establishment of the Greek Catholic and Syriac Catholic Churches.

The Church of Nativity, Bethlehem

Konrad von Grünenberg (Public Domain)

JBW: Could you tell us a little bit more with regard to the Syriac Orthodox Church? If I’m not mistaken, there was a flourishing of the building of churches and monasteries by Syriac Orthodox communities once they fell under Muslim rule around 640.

MI: As a Miaphysite community, the Syriac Orthodox enjoyed the same protected status as other non-Muslim communities under Muslim rule. This allowed them to establish an independent Church hierarchy headed by their patriarch who nominally resided in Antioch, which covered large areas in Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Syria. Some of their oldest churches, with architectural sculpture and occasionally a mosaic, are situated in the Tur Abdin region in Southeast Turkey. Remarkably, around the year 800, a group of monks from the city of Takrit (present-day Tikrit in Iraq) migrated to Egypt to establish a Syriac ‘colony’ within the Coptic monastic community. Their ‘Monastery of the Syrians’ (Deir al-Surian) still exists and is one of Middle Eastern Christianity’s key monuments for its architecture, wall paintings, icons, wood- and plasterwork ranging in date from the 7th to the 13th centuries. The monastery also houses an extensive manuscript collection. Another decorated monastery is the Monastery of St Moses (Deir Mar Musa; presently Syriac Catholic) near Nebk to the north of Damascus, where paintings from the 11th and 13th-centuries can still be seen. The Monastery of St Behnam (Deir Mar Behnam; presently Syriac Catholic) near Mosul is reputed for its 13th-century architectural sculpture and unique stucco relief, but unfortunately, a lot has been destroyed by ISIS warriors.

The Syriac Orthodox presence in Lebanon remained limited to a church dedicated to Saint Behnam in Tripoli, and the temporary use of a Maronite church dedicated to St Theodore at the village of Bahdeidat by refugees from the East who were on the run from the Mongols during the 1250s. This church still displays its complete decoration program from this period. It is impossible to tell which community arranged the refurbishment, but the addition of a donor figure in Western dress testifies to support from a (probably) local Frankish lord. Finally, the Syriac Orthodox also excelled in manuscript illumination, examples of which can be found in Western collections and the patriarchal library near Damascus.

JBW: As the Lebanese and Syrian Greek Orthodox Churches had fewer dealings with Western Europeans than the Maronite Church, does medieval Christian Orthodox art in Lebanon and Syria reflect and maintain the designs and styles of medieval Byzantium? If so, in what ways, and where do we see deviation or innovation?

MI: As I said before, Byzantine-trained artists have been surprisingly active in the Frankish states and beyond, especially during the 13th century. I prefer to label them as “Byzantine-trained” instead of “Byzantine,” because it is not always clear where they came from. To mention an example, painters from Cyprus still worked in the Byzantine artistic tradition but no longer fell under the authority of the emperor after the Crusader conquest of the island in 1291. Culturally they were still fully Byzantine, but, speaking in modern terms, they would have had the Frankish-Cypriot nationality. The little we can say from the preserved paintings is that some Cypriot artists traveled to the Levant in the aftermath of the power change in search of new clientele. It is unknown if they stayed or returned after the accomplishment of their tasks, but around the mid-13th century we see the birth of a ‘Syrian-Cypriot’ style which combines Byzantine painting techniques with typically Syrian formal features and designs; for example, in the afore-mentioned Monastery at Kaftun in Lebanon. Typically, instances of this blended art are not only encountered in Lebanon and Syria but also in Cyprus.

The Virgin and Child Mosaic, Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia Research Team (CC BY-NC-SA)

Focusing on the shared elements in Oriental Christian and Byzantine art, the example of apse decorations illustrates the resemblances and often also subtle differences. From the Early Christian period, the common composition in the apse behind the altar consisted of the mystical appearance of Christ (Christ in Glory) between the Four Living Creatures in the conch and the Virgin between saints, such as the apostles and Church fathers, in the lower zone. However, an early variant encountered in Egypt renders the biblical Vision of Ezekiel: here, Christ in Glory is placed on the fiery chariot the prophet saw. Recent research has brought to light that this variant was also applied in Syriac Orthodox churches in Turkey and Iraq as late as the 13th century. Medieval oriental conch paintings often combine Christ in Glory with the Deesis, that is, the Virgin and St John the Baptist pleading in favour of mankind. Whereas the Byzantines kept these subjects separated, the ‘Deesis-Vision’ is encountered from Egypt to Armenia and Georgia in churches of all denominations

JBW: One cannot discuss medieval Christian art in the Near East without making some mention of Armenians and Georgians. The first recorded Armenian pilgrimage occurred in the early 4th century, and Armenian Cilicia (1080-1375) flourished at the time of the Crusades. During the reign of Queen Tamar (r. 1184-1213), Georgia assumed the traditional role of the Byzantine crown as a protector of the Christians of the Middle East. Armenians and Georgians intermarried not only with one another but also with Byzantines and Crusaders.

Where is the medieval Armenian and Georgian presence the strongest in the Levant? Is it discernible?

Tomb of Saint Hripsime in Armenia

James Blake Wiener (CC BY-NC-SA)

MI: Medieval Armenian and Georgian art can be found in their homelands, but there are also surviving works testifying to their presence in the Levant and Egypt. Starting with the Armenians, they have always lived in groups dispersed throughout the Middle East, whereas in Jerusalem they have their own quarter. A 13th-century wooden door with typically Armenian ornamentation and inscriptions in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem testify to the interest Armenians took in the Holy Land. Further to the south, a 12th-century mural painting with Armenian inscriptions in the White Monastery near Sohag reminds us of the strong Armenian presence in Egypt under Fatimid rule during the 11th to 12th centuries. They had arrived in the wake of the rise of power of the Muslim Armenian warlord and later Vizir Badr al-Jamali, who seized all power in the Fatimid realm during the 1070s. He not only brought his own army consisting of Christian and Muslim Armenians but also made Egypt a safe home for Armenians from more troubled areas.

The Christian Armenians had their own monastery and used a number of churches in Egypt. However, these were appropriated by the Copts at the downfall of Fatimid power and the subsequent expulsion of all Armenians during the 1160s. The Armenian catholicos or head of Egypt is known to have left for Jerusalem taking with him all the church treasures.

At the White Monastery, a mural was made by an artist named Theodore originating from a village in Southeastern Turkey on behalf of Armenian miners who were apparently allowed to use the monastery’s church. It is hard to believe that Theodore came all the way to accomplish just one task in this remote place. There can be no doubt that he decorated more Armenian churches during his stay in Egypt, but the Copts thoroughly wiped out all remaining traces of their previous owners.

The Georgian presence was limited to Jerusalem, where they owned the Monastery of the Holy Cross until it was taken over by the Greek Orthodox in the 17th century. In the monastery’s church, a series of 14th-century paintings with Georgian inscriptions are a reminder of this period. In addition, an icon representing St George and scenes of his life painted during the early 13th century, and kept in the Monastery of Saint Catherine in the Sinai, was a gift from a Georgian monk, who is himself depicted prostrating at the saint’s feet.

St. Catherine's Monastery, Sinai

Marc!D (CC BY-NC-ND)

JBW: Because we touched upon the incorporation of outside artistic influences coming from Western Europe and Byzantium to the Levant, I wondered if you might offer a final comment or two on those architectural or artistic influences coming from the Arab World or even the wider Islamic world.

To what extent did Levantine Christians – who often lived near their Muslim neighbors – adopt or assimilate Islamic styles of art and architecture?

MI: The earliest examples of Islamic art from the Umayyad era display strong influences of Late Antiquity, which in turn had also been the source of inspiration to early Christian art. Over the course of time, these artistic relatives would gradually grow apart to meet again on specific occasions. The earliest example of Islamic-inspired Christian art is the purely ornamental stucco reliefs in the Monastery of the Syrians in Egypt. Constructed during the early 10th century by the Abbot Moses of Nisibis. Its plastered altar room exudes the same atmosphere as houses in the 9th-century Abbasid capital of Samarra and the similarly decorated Mosque of Ibn Tulun (an Abbasid prince who came to Egypt as its governor) in Cairo.

The Mosque of Ibn Tulun, Cairo Egypt

Berthold Werner (CC BY)

The decoration of Fatimid-era sanctuary screens in Coptic churches and woodwork from Egyptian Islamic, Jewish, and secular contexts are fully interchangeable; likewise, 13th-century architectural sculpture, manuscript illustrations, and metalwork from the Mosul area display the same shared stylistic and iconographic artistic language. Broadly speaking, we are obviously dealing with craftsmen working on behalf of different parties at the local level regardless of their religious backgrounds. Occasionally, one comes across ‘Islamic’ ornaments in wall paintings, but the overall impression is that Christian painting was subject to blatant conservatism when compared to more fashionable, ‘neutral’ items of interior decoration. The only Arabic inscriptions found in mural paintings concern texts commemorating building or refurbishment activities, or graffiti left by visitors. There obviously was a difference in status between the vernacular spoken language and the Church’s Greek and Syriac.

JBW: Dr. Mat Immerzeel, thanks so much for your time and consideration.

MI: You are welcome; it is my pleasure to contribute to your magazine.

Mat Immerzeel has been active in the Middle East since 1989, first in Egypt, then in Syria and Lebanon, and recently in Cyprus. His main field of study is the material culture of Oriental Christian communities from the 3rd century to the present. In particular, he studies wall paintings, icons, stone and plaster sculpture, woodwork, and manuscript illustrations. He has participated in research projects focusing on the formation of religious communal identity, the training of local collection curators, and restoration and documentation campaigns. He is the Director of the Paul van Moorsel Centre for Christian Art and Culture in the Middle East and editor-in-chief of the journal Eastern Christian Art (ECA) published by Peeters Publishers in Leuven, the Netherlands.

Continue reading...

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

The feast of Santa Lucia, in Italy, is a journey through popular traditions, from Sicily to Calabria

Santa Lucia (Saint Lucy) is celebrated in Italy on 13 December.

Santa Lucia was, according to the hagiographies which are our only sources, a young girl from Syracuse in Sicily. Born in 283, she died during the persecutions of the Christians under Emperor Diocletian in 304, on December 13th.

The Life of Saint Lucy

As a young woman Lucy was promised in marriage to a pagan. Christians, like Lucy, were at this time still very much a minority in Syracuse.

However, on a pilgrimage to visit the tomb of St Agatha, Lucy had a vision of the saint which was to change the direction of her life. Agatha spoke to Lucy telling her she would cure her mother’s illness (internal bleeding), which she did. After this experience Lucy knew she must dedicate her life to Christ. She made a vow to remain a virgin to better serve her purpose.

On her return to Syracuse, Lucy told her mother of her decision to dedicate her life to Christ, as well as to give all her worldly possessions to the needy. Her mother was at first, (perhaps naturally) sceptical. But eventually it seems she was won over by Lucy’s faith and determination. Over the following years Lucy’s fame in dedicating her life to the poor spread throughout Syracuse and further afield. The young man who wished to marry her, seeing Lucy give all her money and possessions to the poor, and having been refused, decided to denounce her to the town prefect as a Christian. For some time the Roman Empire had felt threatened by this growing Christian “cult” and wanted a display of Rome’s continuing might and power. Lucy was a well-known figure in the community. If she could be forced to renounce her faith other Catholics might follow her. This was the thinking of those who brought her to trial.

So, Lucy was brought to court, where she was accused of being dissolute and possibly of unsound mind too (this was still largely a pagan society where a person’s wealth and possessions were how they gained status in life). It was to be a public trial, so that the humiliation of Lucy could discredit her religion and serve as a warning to other Christians.

At one point the judge Paschasius mocked Lucy for her virginity and said that she would be taken to a brothel, and here she would “lose her chastity” and then “the Holy Ghost shall depart from thee”. Lucy replied that her strength in God meant that 10,000 men would not be able to move her. When the judge put Lucy’s boast to the test this was found to be true – the men could not move her. The judge subsequently ordered for Lucy to be burned and a great fire was built. Lucy again stayed calm and asked for protection from the Lord, calling herself “a temple of God”. The fire was lit, but the flames did not touch her. Lucy told that crowd that persecution of Christians would not last much longer. Hearing her speak so eloquently the prefect was at his wit’s end and called out for anyone that could kill Lucy. Finally someone (probably a soldier) drew a sword and cut Lucy’s throat, which finally killed her.

Her first resting place was in the catacombs under Syracuse which now bears her name. This became the initial centre of her cult, which quickly flourished.

Patron of light and eye sight

Absent in the early narratives and traditions, at least until the fifteenth century, is the story of Lucia tortured by eye-gouging. According to later accounts, before she died, she foretold the punishment of Paschasius and the speedy end of the persecution, adding that Diocletian would reign no more and Maximian would meet his end. This so angered Paschasius that he ordered the guards to remove her eyes. Another version has Lucy taking her own eyes out in order to discourage a persistent suitor who admired them. When her body was prepared for burial in the family mausoleum it was discovered that her eyes had been miraculously restored. This is one of the reasons that Lucy is the patron saint of those with eye illnesses.

The idea probably came from her name Lucy, which derives from lux which is the Latin for light.

She became the patron saint of light and of eye sight. In artistic representations her attributes are two eyes on a plate in her hand.

Her feast day is the day of her martyrdom, December 13th, which in the Julian calendar is the winter solstice, and hence the shortest day of the year. It is therefore a celebration of the return of light.

The procession and rites in honour of Santa Lucia in Sicily and Calabria

Santa Lucia was born in Syracuse, a city in Sicily where the veneration of the martyr and patron saint is at the centre of fervent popular devotion. The celebrations reach their peak on 13 December, the date of her martyrdom, which occurred in 304 A.D. following Diocletian's Christian persecutions.

On this day, a solemn procession accompanies the Statue and Relics of the Saint from the Cathedral to the Church of Lucia al Sepolcro (Lucia at the Sepulchre), a route that is completed in reverse on 20 December. The Statue is a precious silver Simulacrum, dating back to 1599: the Saint wears a palm and a lily, symbol of purity, on her left hand, on her chest the reliquary with the Relics, on her throat a gem-studded dagger and in her right hand a plate with eyes.

The Statue is carried on people's shoulders along the streets of the historic centre, ancient Ortigia, and many devotees walk barefoot, amid flowers and burning candles.

December 13th marks a particularly heartfelt moment in Calabria, where devotion to the "Saint of Light" is intertwined with centuries-old traditions that combine Christian faith, folklore and ancient rites.

In Lamezia Terme (Calabria), the church of Santa Lucia stands in the upper and old part of Nicastro and for this reason the entire neighborhood takes the name of the saint.

Rectangular in shape, the church is modest in size with a very simple facade. The interior has a single nave and inside there are: a wooden statue of Saint Lucia, perhaps from 1700, which surmounts the marble high altar, the work of the sculptor Pergola (1970); a conciliar altar with bas-reliefs on wood and a sculpted ambo (1980), and in two special niches the statues of the Madonna and the Redeemer.

On the night of December 13th, Calabria comes alive with spectacular bonfires, a symbol of light and purification, which illuminate the squares and alleys of numerous towns.

The "Fireworks of Saint Lucia", in Crotone, are one of the most fascinating and evocative traditions of this day. Their origin dates back to ancient times, when they were lit to chase away the darkness of winter, recalling at the same time the image of the Saint and the solstitial rites.

Follow us on Instagram, @calabria_mediterranea

#santa lucia#saint lucy#sicily#calabria#south italy#southern italy#italy#italia#traditions#religion#catholic#catholicism#syracuse#december 13#martyr#martyrdom#light#eye sight#siracusa#eyes#blind#blindness#lamezia#lamezia terme#mediterranean

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Every living being is an engine geared to the wheel-work of the universe.” — Nikola Tesla

Rota Fortunae The Wheel The primordial power of the universe moves in circles. A vast wheel describes the wholeness of Life from its motionless center to its whirling rim. This creative power is in the center and radiates outwards like the rays of the sun. The wheel is Life, it is Law, it is Time. It is the foundation of all worlds and the eternal expression of compassion. Wheels revolve within wheels, time within time and worlds within worlds. Every molecule in the universe is a wheel of life involved in larger cycles of change. The motion of a patient Hindu peasant walking upon a water wheel involves every level of rotary force. The wheel which moves the water from one channel to another is but the most obvious form of this force. The physical energy of his body is sustained by cyclic motion at every level, while the water disturbed by the action of the wheel moves in circular waves. The whole life of this man is a wheel marking the stages between birth and death; his daily thoughts may rest upon the motionless source of all life even while his feet tirelessly turn the water wheel.

If man has come to focus upon the physical rather than the symbolical and philosophical wheel, this indicates the degree to which consciousness has descended into matter. We have moved progressively along the broad sweep of the rim of consciousness in this great cycle of evolution. We have lost the wisdom of the Cheyenne Medicine Man who spoke of men as 'Living Medicine Wheels.'

The wheel symbolizes the interconnected concepts of manifestation, duration and change as well as the dynamic equilibrium of the contrary forces of contraction and expansion. The Secret Doctrine tells us that "wheels are the centres of force around which primordial cosmic matter expands, and passing through all the six stages of consolidation, becomes spheroidal and ends by being transformed into globes or spheres." The zodiac symbolizes the process whereby fecundated primordial energy passes from potential into active energy and then returns to its source. The involution and evolution of life takes place in a great wheel. The apparent orbit of the sun through the twelve divisions of the zodiac corresponds to twelve degrees or stages in the action of the active principle upon the passive. A similar dynamic process is symbolized by the wheel of Tao where the yang and the yin, the positive and negative patterns, appear to be moving into one another, while in fact at any moment in time each occupies half of the sphere in a process of dynamic balance.

Perhaps the most profound conception of the wheel focuses upon the still center or hub, without which there would be no dynamic process, no apparent motion, no manifest balance in nature and in man. The hub of the wheel is still while all revolves around it and radiates from it. The Buddhist Wheel of Life is depicted with detailed forms along its spokes and rim, whereas the hub is undecorated and represents the formless center of life. Ancient scriptures speak of the Great Wheel which is parentless {Anupadaka) and without form, from which emanates the New Wheel for the pilgrimage of Life. The Secret Doctrine intimates how Fohat forms the germs of lesser wheels which extend in six directions from the one central wheel in which the Lipika reside, while the Sons of Light stand at each angle. This is the First Divine World, a great wheel made up of seven wheels. Then Fohat, as primordial Light in circular motion, forms a winged wheel at the four corners of the Second Divine World. Upon the Seven Laya Centers which are the imperishable foundations of the universe, Fohat builds seven wheels in the likeness of older wheels. In this manner the solar wheels evolve, each planet a lesser wheel within the larger whole.

The imagery of an old hymn describes the wheels seen by Ezekiel in the fiery whirlwind – "The Big Wheel run by power and the Little Wheel run by the grace of God . . ." From the awakening of Kosmos, primordial matter tends inevitably toward circular movement, "Deity becomes a Whirlwind." The Great Wheels are Maha Kalpas. The revolutions of our chain of seven planets are Rounds. Atoms filling space continuously vibrate with that motion which keeps the wheels of life perpetually turning. The inner synthesizing principle correlates all forces. At the center stands the Silent Deity, the conscious guiding noumenon. In the language of the Bhagavad Gita, "Ishwara resides in every mortal being and puts in motion, by its supernatural power, all things which mount on the wheel of time."

The voice in the fiery whirlwind and Ezekiel's wheels are the manifested foundations of Law. The fiery wheel revolves while the pramantha or spoke takes fire by friction, conducting it to the rim. This was implicit in the myth of Prometheus. This is also the basis for the idea of grace or compassion expressed by the spokes of Being radiating from the hub of the wheel. If Compassion is the Law of Laws, then its structure delineates the wheels upon which Karma is enacted. The wheel is Law, but it does not roll in any linear sense. It turns upon the ocean of chaos, transforming it and compelling a new succession of forms.

It is said that Buddha gave a turn to the Wheel of The Law by bringing the Light of Illumination from the Still Flame at the center of the wheel into his earthly, temporal vestures. He conducted the fire out onto the rim of the wheel and increased the rotary movement of terrestrial life. The Law quickens by the presence of such a One. Karma is stirred and mankind feels the heat of the Central Flame. So it was that Krishna appeared at the beginning of Kali Yuga, heralding an age of increasingly rapid change, giving a crucial turn to the wheel.

Chinese tradition divides the wheel, recognizing eight basic dynamic movements in the cosmos, interrelated by two principles. The Cosmic transformations are reflected in the world by combinations based upon these patterns, each relating to the fundamental duality of the yin and the yang, the interplay between the pairs of opposites. The spokes of the wheel emphasize divisions of a whole wherein duality balances.

In Hinduism, the spokes of the wheel come alive, becoming transmitters of Light, witnesses of the Eternal Center and compassionate supporters of the rim. Siva stands in the center of the universe, surrounded by fire. Poised and motionless, he yet engages in the eternal dance of motion. Siva, the Initiator of all Initiates, destroys the dying forms clutching at the rim of life. The divine process of progressive enlightenment discussed in Hindu metaphysics follows a spiralling motion, just as a point moving toward the center of a rotating wheel describes a spiralling path. The spoked wheel provides the channels whereby the periphery can come to know the source of the whole. The structure of the Law enables the centrifugal and centripetal forces to interbalance ceaselessly, whirling around a fixed point of Truth and Balance. Again, in the zodiac, the cardinal points initiate, while the fixed points contain and sustain, but the mutable points are fluidic and enable constant reassertion of a new dynamic balance.

The Cheyenne Elders taught that the universe is a great Medicine Wheel. It is the "mirror of the People and each person is a mirror to every other person." The Medicine Wheel is the Living Flame of the Lodges and all things are contained within it. Every person is a Living Medicine Wheel and was originally a Power existing somewhere in time and space but having no form. Each Power possessed boundless energy and beauty. These Living Wheels needed only the understanding of limitation, the experience of substance, the learning of the heart to become whole. Heamavihio, The Breath of Wisdom, and Miaheyyun, Total Understanding, are but two of the words in the Cheyenne language which express this wholeness. For man to become whole, he must learn the Whole Wheel.

By understanding the Whole, one becomes the Whole and transcends it, for the true center of the wheel is a metaphysical point which is not on the wheel itself. The ideal is set forth by Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita, where he says: "I established this whole Universe with a single portion of myself, and yet remain separate." The disciple moves along wheels within wheels, striving to approach the position of the sage "who has attained the central point of the wheel and remains bound to the 'unvarying mean' in indissoluble union with the Origin, partaking of its immutability and imitating its non-acting activity."

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

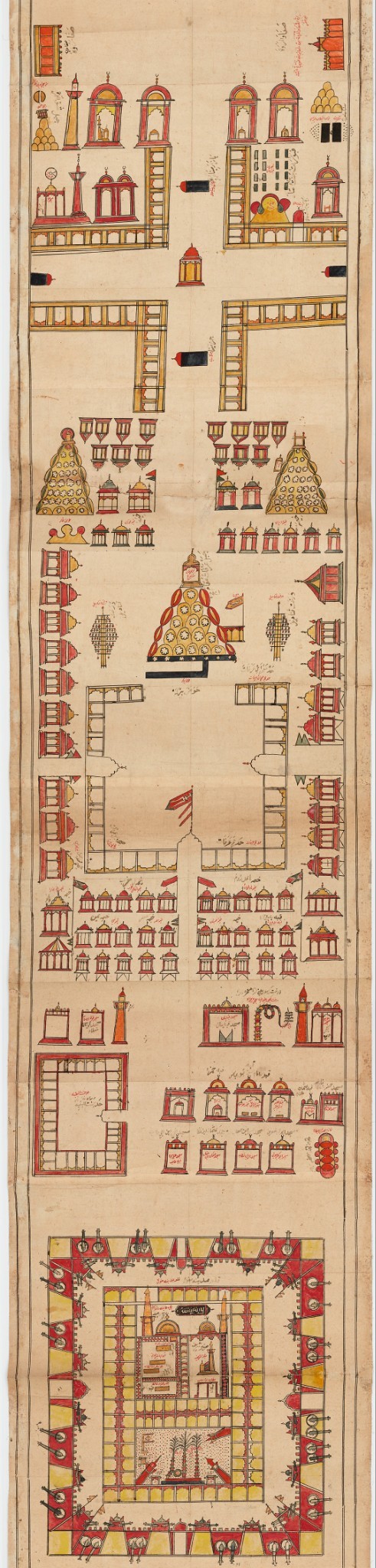

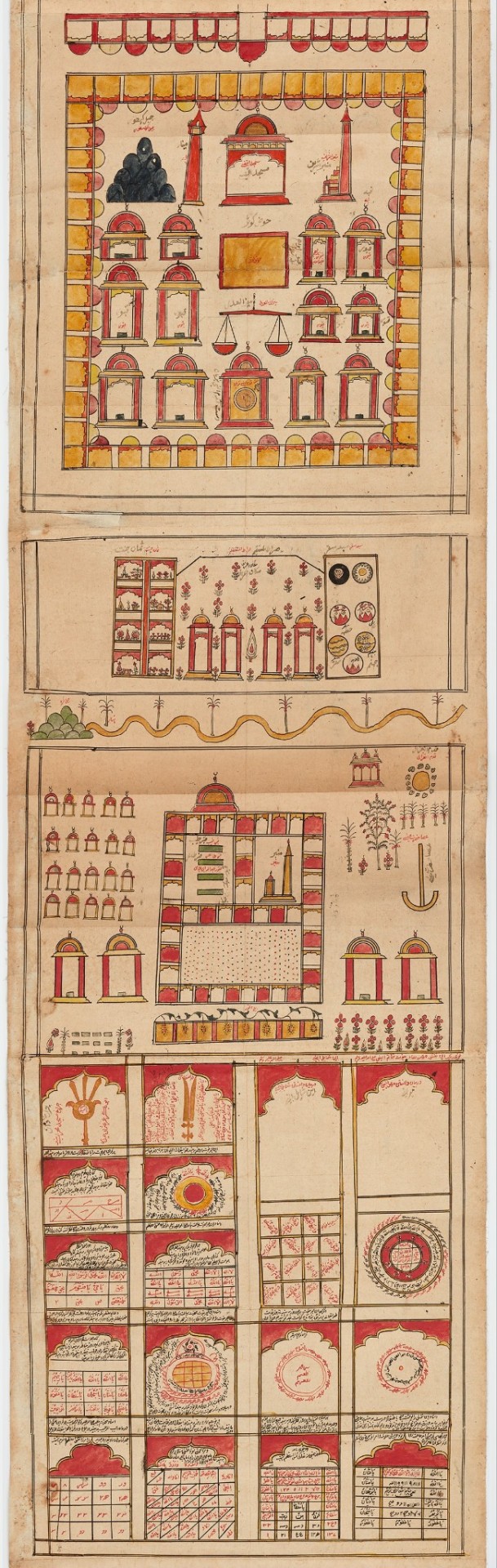

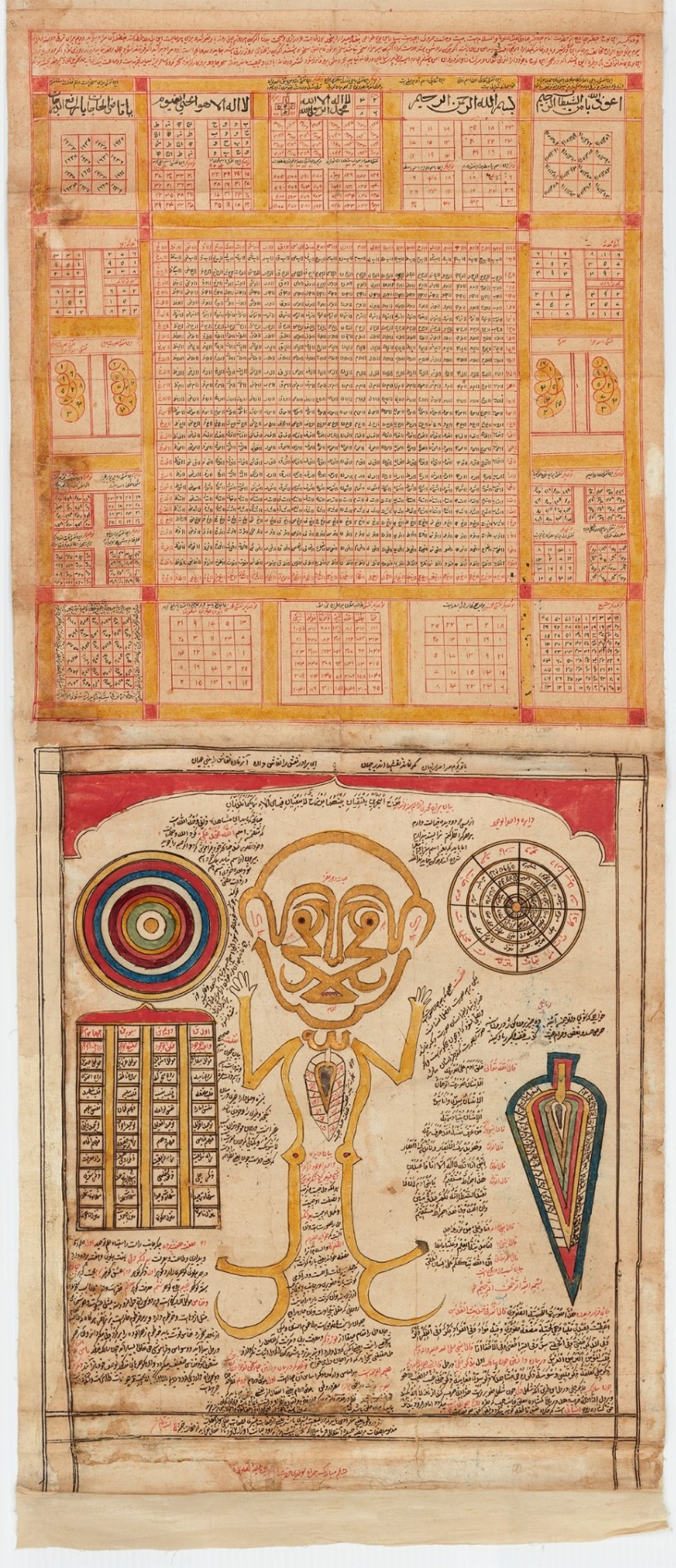

Shiite Talismanic Pilgrimage Scroll

India, probably Deccan, 1787–88

opaque watercolour, black and red ink, and gold on paper; mounted on cloth backing

This monumental scroll measuring more than 900 x 50 cm depicts several major Muslim holy sites, such as the sanctuary of the Ka‘ba and other pilgrimage stops of the Hajj in and around Mecca, as well as Medina, Jerusalem, Karbala, and Najaf. Arranged vertically, these buildings and sites are all oriented towards the Great Mosque in Mecca with the Ka‘ba at the centre; in this manner, the Ka‘ba functions like a magnetic pulse located in the first third of the scroll. Two visual sequences—one starting at the beginning of the scroll marked by a colophon cartouche, and the other at the end of the scroll marked by a calligram (here, a human figure made of calligraphy)—comprise its composition. This scroll has previously been thought to be a Hajj certificate, a document affirming that an identified individual or his/her representative has fulfilled the Hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca and surrounding sites. However, recent research confirms that a considerable portion of the visual repertoire and its inscriptions was composed to increase magic and talismanic functions of this scroll within a clear Shiite context.

#Islam#religion#India#deccan#18th century#1780s#watercolour#ink#gold#talisman#pilgrimage#artifacts#history

42 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

Les aspirations les plus absurdes et les plus téméraires ont parfois conduit à des succès extraordinaires.

- Vauvenargues

St. Moritz has been a famous health resort in Engadine since the 19th century. At first, it was only frequented by spa guests, before the village developed into a high alpine sports centre, and for a time it was a playground for the rich and famous. There’s still some of that element present but not as in its hey day of the 70s. For nine months of the year it’s just another picturesque village in the gorgeous Swiss Alps, with Lake St. Moritz lying at its heart.

Crucially it is quietly forgotten by the outside world. Residents can breathe and go about their daily chilled out lives. For those precious nine months it was great to hike and ski there as my boarding school wasn’t too far away from getting there. But the other four months of the year, the high season, it gets flood with skiers and altogether more showy crowd.

The frozen surface of the lake, which can only be described as a desert of snow, now serves as a symbol of the resort itself. From nine months of natural bliss to four months of chaos and madness. Every time the ice lends its surface to polo tournaments, horse races, and the wealthy and beautiful make the pilgrimage down the mountains from their grand hotels, St. Moritz seems to transform. St. Moritz’s newest ‘gimmick’ for the past three years or so has been to serve the International Concours of Elegance St. Moritz - or The ICE St. Moritz - as a kind of classic car museum with an adventurous character.

Since the first ever The ICE St. Moritz in 2019, historic rally cars have been exhibited to the sports car-crazy public on the opening day, before demonstrating their horsepower on the ice racetrack on the second day of the event. However, the fact that The ICE is taking place on Lake St. Moritz, of all places, is no coincidence. In 1985, a group of Scottish and British sportsmen drove their vintage Bentleys to St. Moritz to celebrate the centenary of the Cresta Run (an eccentric and high spirited toboggan amateur race). As part of the festivities, they drove their cars on the racecourse across the frozen Lake St. Moritz.

This year, however, the ICE St. Moritz evolved slightly differently. For the first time, the event was held on two days: Friday 24 and Saturday 25 February. On the first day, the lake was transformed into an open-air museum, where the jury evaluated the cars on display from an aesthetic perspective. Then, on the second day, the actual race took place, whereupon the jury evaluated the classic cars from a performance perspective.

This year there were five category winners. In the ‘Open Wheels’ category, the 1958 Maserati 420M/58 “Eldorado” held its own. Meanwhile, the ‘Barchettas on the Lake’ category crowned the Ferrari 500 Mondial Series II from 1955 as the winner. My personal favourite, the aforementioned Ferrari 250 Testarossa ‘Lucybelle’ emerged as the winner in the ‘Le Mans 100’ category. As expected, Lancia Strato’s HF Zero of 1970 came out on top in the ‘Concept Cars & One Offs’ category. Last but not least, judges crowned the 1958 Bentley S1 Continental Drophead Coupé as the winner of the ‘Queens on Wheels’ category.

The evening gala took place at Badrutts Palace, which towers over the city like a castle with its high stone walls. In the stimulating semi-darkness and under shimmering candlelight, riders, collectors, enthusiasts, the public and media from all over the world celebrated the conclusion of one of the most anticipated competitions in the Engadine. Overall it’s spectacular fun and contrary to what one might believe it really does draw the car enthusiast crowd rather than the snob mob. It’s a very chilled event and bags of fun.

#ICE st moritz#vauvenargues#quote#french#sportscar#racing#racers#driving#drivers#ice#st. moritz#snow#switzerland

306 notes

·

View notes

Text

On 10 February 1973, Princess Anne visited Asmara War Cemetery, Eritrea, during a two-week tour of what was then Ethiopia and The Sudan.

In 2004, Princess Anne visited Malta to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the island’s independence. During her trip, she visited the CWGC’s Malta Memorial, Floriana, where she laid a wreath and paid tribute to the nearly 2,300 airmen who lost their lives during the Second World War.

The Princess Royal was the guest of honour as they opened The CWGC Visitor Centre in France. The princess took a tour of their new site, seeing the hard work of their teams and meeting some of the key staff involved in bringing the visitors centre to life, in 2019.

Princess Anne visited Etaples Military Cemetery in celebration of the 100-year anniversary of King George V’s ‘King’s Pilgrimage’, in 2022.

Madra's War Cemetery, India, 1985.

Khartoum War Cemetery, Sudan, 1985.

Fajara War Cemetery, Gambia, 1990.

Sai Wan War Cemetery, 1997.

Port Moresby (Bomana) War Cemetery and Memorial, Papua New Guinea, 2005.

Kranji War Cemetery, Singapore, 2005.

Simon's town (Dido Valley) Cemetery, South Africa, 2012.

Jawatte Cemetery, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2024.

The Commission’s Headquarters, Berkshire, 2024.

Princess Anne, President of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission ✨

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

On 13th January 614, St Kentigern/Mungo died , and was buried at his church in Clas-gu which later become Glasgow.

Saint Kentigern has been venerated for many centuries as one of the apostles of Scotland and patron-saint of Glasgow. He is best known in Scotland as Mungo, which means "darling", or "beloved one". Unfortunately, very little genuine information on this 6th-century saint has survived. His later life was composed by a Cistercian monk, Jocelyn of Furness, late in the 12th century, but earlier traditions about the saint are more authentic.

The future saint was born in about 518 or 528 in Culross in Scotland. His mother was the holy princess Theneva, (Enoch) who is also venerated as patron-saint of Glasgow, who's father Loth, King of Gododdin (modern day East Lothian) - was thrown out for being pregnant with Mungo after an illicit encounter with her cousin, King Owain of North Rheged (now part of Galloway). Her furious father had her tied to a chariot and launched off Traprain Law.

Amazingly she and the unborn baby survived and her father, now believing she was a witch, set her adrift in a coracle without oars up the River Forth.

His early life was shaped by St Serf who ran a monastery at Culross and rescued his mother and cared for her and the young boy who he affectionately called Mungo, meaning 'dear'.

Aged 25 Mungo began his missionary work on the banks of the River Clyde and built his church close to where the Clyde and the Molendinar Burn merge - this later became Glasgow Cathedral.

He was exiled during AD565 when anti-Christian King Morken of Strathclyde drove him away - he travelled through Cumbria and settled for some time in Wales before completing a pilgrimage to Rome. By the 570s a new king, Rhydderch Hael of Strathclyde, overthrew King Morken and invited St Mungo back to become Archbishop of Strathclyde. His church on the Moledinar became the focus of a large community that became known as Clas-gu or 'family'.

He died on Sunday 13 January 614. He was buried close by his church, and today his tomb lies in the centre of the Lower Choir of Glasgow Cathedral.

In order to become a Saint, it was necessary to prove that the candidate had performed miracles during their life - St Mungo was supposed to have performed four immortalised in this poem:

Here is the bird that never flew

Here is the tree that never grew

Here is the bell that never rang

Here is the fish that never swam

Today the bird, the tree, the bell and the fish form the four elements of the crest of Glasgow City Council.

St Mungo continues to influence Glasgow life today such as the mural seen on High St Glasgow by Australian born artist, Smug, depicting a modern day St Mungo and referencing the story of The Bird That Never Flew near to St Mungo's final resting place at Glasgow Cathedral.

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

more rambles pls

After some deliberation I have decided that I will give you the full Laith’Zairel breakdown. It is a very interesting city and also the home of our boy Xaeren.

Ok then, let’s see…

This post has 3 parts.

Maps

Houses

History

Maps

These are a few sketches of Laith’Zairel in around 60 - 0 BD under the rule of the Edrelian empire. As you can see they liked their circles.

In Edrelian culture circles were seen as the ‘perfect shape’ so it symbolised beauty and status to have a city made of intersecting circles and towers.

Houses

Since Tollenic rule Zairel has been run by the houses.

They have served as merchants, feudal lords, advisors to the king of the day, multiple different councils, and in and out of a monarchy.

They gained and maintain power by controlling the routes of trade in and out of the city.

The major houses have risen and fallen through time but in the modern day the three main houses are Tai’Fell, Lysandri, and Hiresias.

House Tai’fell - The house of the king and the advisory council. They are in charge of lawmaking and enforcement. Tai’fell also controls large amounts of land around Zairel and the trade of most higher value goods. You can only become a member of house Tai’Fell by birth into a noble family of the house, by marriage, or by request of the king.

House Lysandri - Also known as the tliet magesterium or tliet mysteries. This house consists of mages and druids who are trained in magic undergo trials and education to become members of the house and gain it’s secrets. They gained their power through controlling the creation and trade of magic items in Zairel. Lysandri is one of the only mage groups that does not outlaw somni (non-arcane) magic but embraces it as just another source of power. They are run by the small council (group of 5 people who are all incredibly magically capable, voiced by Febras Ollati) The house honours lineage and magic bloodlines but also welcomes talented younger students from outside of the house

House Hiresias - The oldest of the major houses and the most underestimated. Xaeren is part of this house. Hiresias claims to earn their wealth through trade of many common goods and control of a great number of dockyards, and while this is true, they also control a much more valuable resource. It is also referred to as the Court of Whispers in reference to its control over city secrets and alleged association with the criminal underworld. They have also been known to act as a check and balance for the other major houses. It is run hypothetically by the proxy king Tirr hasken but he is actually commanded by ‘the hidden king’. The existence of the hidden king is a closely kept secret within the house and very few know of their existence. This makes the house incredibly hard to depose as they can quickly and effectively switch figureheads with little impact on organisation. Hiresias is not selective by birth but by skill and loyalty. New hidden kings are selected by the current hidden king and are trained by them. They also are taught by a variety of other people around the globe on a mandatory pilgrimage where they visit leaders and politicians to learn about the world in practice rather than just theoretical understanding.

History

Zairel was named after the Zairi people who lived there in ~2500 BD

These people were conquered by the Arinites in ~2150 BD then this culture evolved through multiple faction changes (Arin-Tollenics and Tollenics) Through these periods it is a popular trade city and a military center, the city was called Zahre while under Tollenic rule. Zahre controlled a city state and was a cultural centre in Tollens. (1400s - 1000s BD)

The Tollenics were breifly conquered by the Kore who later inhabit Korlan. (870 BD) They partially sacked Zahre and while most of the culture was preserved, it was in incredibly weak city struggling to rebuild itself.

In 815 BD Zahre is conquered by the Edrels who were beginning to control the southern coast. The city is renamed Zahrelat under Edrelian rule (lat meaning city) to show Edrelian control over the people. While a part of this empire the Edrelians respect Zahre culture and Zahrelat is a major trade post as the Edrels use a lot of sea travel for transport and war. It becomes the western capital of the expanding republic of Edrel and is once again flooded with multicultural travellers and treasure as it begins to regain some of its lost status.

In 500 BD mortal arcane magic begins to permeate the world and a faction within ‘Emerilai’, as it was known at the time, rebels and takes control of the republic beginning the Edrelian Empire. This faction was originally northern so common Emresian changes to add the city ‘lat’ as a prefix not a suffix. Emerilai become Laith’Emeris and Zahrelat become Laith’Zairel.

Under the new mage rule Zaireli culture truly evolves with the houses taking on more distinct roles and House Lysandri adopting magic as a way to move up the ranks into being a major house. Because of Lysandri’s early monopolisation of powerful magic, Laith’Zairel becomes less dependent on magic than other Laith’Edrels.

Over the years under Edrelian rule, Laith’Zairel reaches its first peak of power. They are the centre of trade for the most powerful Empires on the planet and essentially manage the resources for the entire western half of the empire.

While Emeris’s focus shifts to magical research, Zairel remains intensely practical with houses competing for trade routes and contracts. This means when the other mage cities start whispering about immortality magic, Laith’Zairel is largely unfazed and does not get involved.

In around 60BD Laith’Zairel starts to think of itself as a seperate people to the Edrelians having become such a world city. Their culture is such a mixing pot of prior Kaitere refugees or people from Illeran or of Tollenic or Kairel descent, that they don’t feel attached to the empire’s ideals anymore.

By 0 BD Laith’Zairel is already on the edge of declaring itself independent so when the Dissolution begins they just step back.

There is so much more about history, house wars, magestones in Zairel, The vying for power over magic post dissolution etc. but I can’t fit it in this post. The rest will be added as soon as I have time to type it up.

Tagging the tag list~

@thelovelymachinery, @an-indecisive-nerd, @the-letterbox-archives, @oliolioxenfreewrites, @winvyre

@happypup-kitcat24, @wyked-ao3, @leahnardo-da-veggie, @alnaperera, @dearunreliablenarrator

@rumeysawrites, @urnumber1star, @seastarblue, @thecomfywriter

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Photo: Statue of Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians, who passed away in 918. Her nephew Aethelstan, future king of all England, looks up at her.

"Aethelflaed was one of three daughters of Alfred the Great, and her name meant "noble beauty". She married Aethelraed of Mercia at some point during the 880s and while this union meant a strong alliance between Wessex and Mercia the pair embarked on a "Mercian revival" with the city of Worcester at its centre.

When Aethelraed died in 911 after years of ill-health Aethelflaed remained as Lady of Mercia and held this position until her death, making her the only female ruler of a kingdom during the entire Anglo-Saxon era. The only compromise she made was to agree to her brother Edward, now king of Wessex, taking some of Mercia's southern lands under his control.

Their father Alfred the Great had fortified dozens of Wessex towns as "burhs" and Edward continued this work, connecting his burhs with those in Mercia to represent a united front against viking incursions, and it wasn't long before this was put to the test.

A force of vikings, pushed out of Ireland, landed in the mouth of the Dee after unsuccessfully trying to take land in Wales, and asked Aethelflaed if they could settle for a time outside the old Roman walled town of Chester. Permission was granted but the Norsemen raided and robbed the area at will so Aethelflaed led a force to shut them down. She had Chester fortified and waited for the inevitable viking attack, it came and was repulsed, the Scandinavian chancers sent packing in complete disarray.

This same Norse army was brought to battle at Tettenhall near Wolverhampton where Aethelflaed's forces destroyed them. The writing was now on the wall - the vikings had to go. Together with Edward she raided deep into Danelaw territory on a mission to rescue the bones of St Oswald - who had been killed and ritually dismembered by the pagan king of Mercia Penda - from a church in Lincolnshire then brought the relics down to Gloucestershire where a new church was built to house them...more on that presently.

The burhs continued to be built, and the Dane strongholds fell as Aethelflaed campaigned hard against them. Her forces defeated three Norse armies before finally taking the city of Derby, then Leicester, before the Danes of York came to her to pledge their loyalty. The vikings in Anglia capitulated to Edward and so all of England south of Northumbria was now back under Anglo-Saxon rule.

Aethelflaed died at Tamworth in 918 and so will be forever associated with the town, but she was carried down to Gloucestershire to be buried in the church she had built for St Oswald. Unfortunately the monastery there fell into decline over the centuries, was dissolved in 1536, then almost completely destroyed during the English Civil War. Nobody knows where Aethelflaed's resting place is now, but the ruins of St Oswalds are as good a place as any as a pilgrimage destination for those wishing to follow in the footsteps of the Lady of Mercia." - Source: Hugh Williams via Medieval England on FB.

Photo: Statue of Aethelflaed and Aethelstan at Tamworth Castle, by EG Bramwell, unveiled in 1913.

#Aethelflaed#Lady of the Mercians#Aethelstan#Aethelraed of Mercia#Medieval History#Alfred the Great#Wessex#Mercia#Northrumbria#England#Anglo-Saxon#Tamworth Castle#Statue#Medieval England#Hugh Williams

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

mountainworld In Hinduism, a ghee lamp (diya) and it's flame symbolizes purity, knowledge, and the spark of enlightenment. The warm light of a ghee flame is believed to attract a divine presence, bringing peace and calm. In this holiday season and the near dawn of a new year, amidst the hardship and chaos of our world, may you all find a bit of peace, calm, beauty, knowledge, and a light in the dark.

Happy Holidays and Happy New Year!

* This photo was taken when @samheughan and I visited the Bishwarup Mandir in the forest above Pashupatinath Temple in Kathmandu, Nepal, a truly peaceful and spiritual place.

_______________ 🗻🗻🗻🗻______________

Jake Norton’s photo, with a ghee diya lamp, in Bishwarup above might be the temple of Lord Vishnu** in the Pashupati area of Kathmandu in the Mrigasthali forest a tranquil site located in Kathmandu, Nepal, the forest is a a significant tourist attraction. The Mrigasthali forest is an enrichment place close to several religious sites. Allowing for a blend of nature and spirituality.

Mrigasthali offers a perfect escape from city life. The highlight of Mrigasthali is the panoramic view it offers of its surrounding landscape, including the majestic Himalayan foothills. Photographers and nature enthusiasts will find this location particularly rewarding, as the vista changes with the shifting light throughout the day. The area is less crowded allowing you a personal experience with the spirituality that permeates this part of Kathmandu than other tourist hotspots.

From the main entrance of the Pashupatinath Temple, head south towards the Bagmati River. You will see the riverbank on your left. Continue walking along the riverbank, enjoying the view of the sacred river. After about a 10-minute walk, you will arrive at the entrance to Mrigasthali, the path is straightforward.

This area is the junction of three ancient cities of Kathmandu, Bhaktapur and Patan where SH and JN stayed at Hotel Timila in Lalitpur, also known as Patan. Tribhuvan International Airport is located 1 km (0.6 mi) from Pashupatinath Temple and 6 km (3.7 mi) east of the city centre and the place to stay to organise your departure from Nepal🇳🇵

** Lord Vishnu In Hindu mythology, is said to have grabbed the horns of Shiva and shattered them into four pieces after Shiva refused to return home from the Mrigasthali forest. He is the second god in the Hindu triumvirate, along with Brahma and Shiva.

Pashupatinath temple is a sacred Hindu temple and a pilgrimage site in Nepal situated in the eastern Kathmandu valley on the banks of the sacred Bagmati River, approximately 5 km east of Kathmandu's main city. Lord Pashupatinath is the national deity of Nepal and is considered to be the guardian of Nepal (is a form of the Hindu deity Lord Shiva central figure in the religion)

The main temple an architectural masterpiece is built in the Nepalese pagoda style architecture. All the features of the pagoda style are found here, like cubic constructions and beautifully carved wooden rafters on which they rest (Tundal) often carved with deities and celestial beings. There are four main doors wrapped in silver sheets and the two-level roofs are made of copper with gold covering.

Lord Pashupatinath is the oldest temple in Kathmandu and has also been listed on a UNESCO World Heritage Sites list since 1979 was erected anew in the 15th century by King Kirat Yalambee, and stood strong with no damage against the great earthquake of 7.8 magnitudes on 25th April 2015.

Pashupatinath Temple and Bagmati River in Kathmandu, Nepal. 🛕 some visitors can view the main temple from the opposite side of the river, similar to Sam in the photo above.

Entry into Pashupatinath Temple itself is only allowed to Hindus. Entry into the inner courtyard is strictly monitored by the temple security, which is selective of who is allowed inside. The temple and its grounds are considered so sacred that only Hindus are allowed to enter. This includes Foreigners and non-Hindus who are asked to watch from the opposite side of the Bagmati River.

Sonia Gandhi, the Italian-born wife of former Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, was famously refused entry to Pashupatinath when she visited in the 1980s, so mere tourists shouldn’t expect the rules to bend for them.

Posted 26th December 2024

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ennin

Ennin (c. 793-864 CE, posthumous title: Jikaku Daishi) was a Japanese Buddhist monk of the Tendai sect who studied Buddhism at length in China and brought back knowledge of esoteric rituals, sutras, and relics. On his return, he published his celebrated diary Nitto Guho Junrei Gyoki and became the abbot of the important Enryakuji monastery on Mount Hiei near Kyoto and, thus, head of the Tendai sect.

Tendai Buddhism had been introduced to Japan by the monk Saicho, also known as Dengyo Daishi (767-822 CE). Based on the teachings of the Chinese Tiantai Sect, Saicho's simplified and inclusive version of Buddhism grew in popularity, and its headquarters, the Enryakuji complex on Mount Hiei outside the capital Heiankyo (Kyoto), became one of the most important in Japan as well as a celebrated seat of learning. Ennin became a disciple of Saicho from 808 CE when he began to study at the monastery, aged just 14.

Travels to China

Ennin was selected as part of a larger Japanese embassy led by the envoy to the Tang Court, one Fujiwara no Tsunetsugu, to visit China in 838 CE and study there. The main aim was for Ennin to study further the Tendai doctrine at the T'ien-t'ai shan. Ultimately, he would stay there for nine years, studying under various masters and learning in greater depths the tenets and rituals of Buddhism and especially the mysteries of Mikkyo, that is esoteric teachings known only to a very few initiated priests.

On arrival at Yang-chou and awaiting to be taken to T'ien-tai shan, the monk wasted no time and there and then found priests to teach him shitan, the Indic script used in esoteric texts. He also made his own copies of such texts and underwent an initiation with a priest called Ch'uan-yen. As it turned out Ennin did well, for by the time the Chinese authorities had organised his transport to his original destination he was informed there would be no time to do so if he were not to return to Japan as planned with the embassy. Ennin decided to stay and passed the winter at a monastery in Shantung run by Korean monks.

In the spring Ennin set off for Wutai, an important pilgrimage site and home to some more learned monks who could help satiate his thirst for Buddhist knowledge. Mount Wutai, where the bodhisattva Manjusri was thought to have appeared, was also a centre of esoteric cults. Over the next 50 days, Ennin acquired such techniques as rhythmically chanting the name of Amida Buddha and changing the intonation each repetition.

From 840 to 845 CE Ennin then studied at Ch'ang-an, learning more of Mikkyo, copying texts and mandalas, and being initiated by three different esoteric masters, going beyond the level that the recognised Japanese master and foremost expert Kukai had reached. In 845 CE Ennin, like many Chinese monks, suffered the persecution of anti-Buddhist emperor Wu-tsung, and he was compelled to return to Japan. This was easier said than done and it took two years, the death of Wu-tsung, and a general amnesty for him to finally find a ship that would make the voyage.

Continue reading...

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Chicago experiences in no particular order:

Had a deep-dish pizza

Saw ice on Lake Michigan

Listened to ice on Lake Michigan

Got snowed on

Met Eden @everymanpdf and had a lovely chat

Bought fancy tea while chatting with Eden

Had a gimlet that was a bit stronger than I usually make them and once I was back in the hotel room scrolling etc. noticed I was getting very giggly at things that were really just mildly amusing

Saw my friend my new best friend Sue the T-Rex

Saw my beautiful silver wife the Pioneer Zephyr again

Looked at the Bean

Made a pilgrimage to Wrigley Field

Bought a Cubs-branded cap and baseball because I'm a sucker

Threw a snowball at my dad

Rode the L

Rode the bus

Walked round in circles, in the snow, trying to find a bus stop

Saw Nighthawks again

Had an almost constant not-quite-nosebleed from the minute I got on the plane until the minute I landed back in the UK from all the dry air

Got fucked around by Icelandair at the last minute

Got rescued at the last minute by Air Canada

Got stuck in Toronto for 5+ hours

Admired Chicago cultural centre and puppets

Took full advantage of my 7-day travel pass and rode the L to go look at Union Station because I had an hour to kill

Was the bravestest boy in the world and flew back by myself

Didn't get jet-lagged either way

#great city marvellous city a proper city#we've been enjoying the fancy tea#that gimlet was either a double or just a much higher ratio of gin to lime (i usually make it 50:50- the terry lennox)#i'm obsessed w holding this baseball and tossing it about it feels so good in the hands#i forgot what a shit movie selection ba has when i was booking my return flight#pointless post

16 notes

·

View notes