#philippe duc of chartres

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Some more @gonzague-if art this time of the 3 Philippes giving every bi and Pansexual person in the French court a collective heart attack. Just 3 BFFS out there charming, scheming, dancing, dueling, and occasionally making out with each other you know like besties do!

Also, a little doodle of the trio doing some dumbass shenanigans. Lbr as much as I picture my Prince Médée being the more serious one out of her friend group, she'll indulge Nevers and Chartres in their antics. Besides, this is not the first time she's found herself being carried by Nevers or riding Charters lap, but she's never done both at the same time. So it was a surprising and fun experience she'll remember fondly...at least until the inevitable heartbreaking betrayl.

#gonzague if#gonzague: médée#philippe de Nevers#philippe duc of chartres#prince Philipe gonzague#three Philippes#because every friend group needs a fun royal#a sweetheart himbo swordsman#and a mean Bisexual woman in menswear that'll kill ur enemies or help u hide the bodies

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Equestrian portrait of Louis Philippe Albert d'Orleans, Count of Paris (1834-1894) and Robert d'Orleans, Duke of Chartres (1840-1910). By Alfred de Dreux.

#alfred dedreux#alfred de dreux#pierre alfred dedreux#equestrian portrait#royaume de france#maison d'orléans#bourbon orleans#louis philippe albert d'orléans#comte de paris#robert d'orléans#duc de chartres#kingdom of france#house of bourbon#house of orleans

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philippe d'Orléans, Duc de Chartres

The Duc de Chartres is Gonzague’s other close friend, a royal connection the Prince made sure to acquire by any means possible. It turned out all it took was to be sufficiently entertaining to the King’s nephew. Chartres is an easy friend to have, very little seem to bother him.

A libertine, he likes to indulge with parties and numerous lovers, making him infamous in court. In reality, this outrageous reputation hides a bright mind and lofty ambitions.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

DROITS FONDAMENTAUX ET VERTUS AU COEUR DU POLITIQUE - AVEC BATHILDE D’ORLÉANS, « PREMIÈRE » DES LUMIÈRES

Princesse progressiste Louise-Marie-Thérèse-Bathilde d’Orléans, princesse de CONDÉ (1750-1822), est la sœur de Philippe-Égalité (ultime avatar du duc de Chartres, Grand Maître du Grand Orient) et l’épouse (1770) de son cousin Louis VI Henri de Bourbon-Condé (1756-1830), qui s’en sépara très vite. Elle est la mère du duc d’Enghien et la tante de Louis-Philippe. Adoptant les idéaux de la…

0 notes

Text

Marie Antoinette (2022)

What is it with Marie Antoinette and Duc de Chartres (alias Philippe Egalité), they supposed to hate each other????

This is crap.

Btw. Where is Artois???

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you think of Chartres in the drama Marie Antoinette?

So, I still haven't watched the show, so I want that on the record. My opinions are formed purely based off of what I'm hearing; if you ask me after I have the time to watch the whole thing, you might get a very different opinion out of me.

That being said. Well. The lovely thing about being a Philippe fan is that you get used to...everything. Like, I'm totally numb at this point. I read Innocent, there's nothing that can shock me as far as Philippe portrayals. It's physically impossible to shock me, I've seen it all. Every horrible thing you can imagine Philippe doing, I've seen him do on either page or screen, which is impressive when you consider that he doesn't get that many media portrayals.

(VERY long discussion incoming where I touch on rape and rape culture, underage sex, and sexual harassment. Fun times.)

But. Well. It's more of the same, isn't it? The Duc d'Inceléans is upset when the woman he is obsessed with rejects him, throws a tantrum, and joins the revolutionaries, going fully Frollo on her. I wish that people would stop resorting to cheap drama re: him and Antoinette -- their dynamic was so much more complex than just obsession and lust. It was the sort of relationship where...you desperately WISH that things could have been different between them, that they could have remained friends, or reconciled after their falling out, that she could have negotiated a truce between him and Louis before things got so ugly, but you also know that their natures just...they were both strikingly alike in the worst ways (and both of them would HATE that I'm saying this now.) When they were young, that similarity drew them to one another -- they were both young people who didn't really care for convention, with a taste for excitement and balls and parties.

But then they got older, they got more jaded, and that similarity came back to bite them hard in that neither one of them were of a particularly forgiving temperament. They were both loyal to the people who they were close to, even in defiance of any sense of propriety. If you were in their inner circle, you were *in*. But if you did something to ruin that trust, you wouldn't be forgiven. And, as they got older, and the Revolution ate away at them, that paranoia, it became much easier to commit an unforgiveable slight. (Would Orléans, at the beginning of the Revolution, have had an argument with Grace Dalrymple Elliot that left both of them distressed? Would he have tossed his wife out of Palais Royal with only the clothes on her back? Would Antoinette have had a falling out with the Comte d'Artois, her friend since her first days at court? Would she have been heard commenting on her frustration with the émigres? It isn't to say that either of them were even entirely WRONG, or that these things wouldn't have annoyed them...though Orléans snapped harder as time went on, see above re: his wife...rather that things that might have led to a minor tiff a few years back led to friendship destroying falling outs in 1792-1793.) There came a certain point, probably after Ouessant though definitely by 1787-1788, where they'd just hit a point of no return with one another. They'd circle around one another, toy with the idea of playing nice, but they just...couldn't. It wasn't in their natures, even if it was in their own best interests.

And I don't want to be a fatalist, but a part of me wonders if they weren't kind of destined to be at odds. Orléans was born into having an uneasy relationship with Antoinette's husband, who she did love. He'd have always been a revolutionary at heart -- Even had he been on good terms with her and Louis, something tells me he'd have always taken up with the Revolution, even though spite was absolutely a factor in his part there. The thing that you get the feeling of with Philippe is that...he had compassion. We have stories of him pulling his valet from the water when he nearly drowned, of going into mines to see the circumstances the miners were working in, of him, even as a child, giving money to veterans and the poor. And he wasn't a man to sit on the sidelines and stick to the proscribed ideas of aristocratic charity. If there's one word I associate with Philippe, it's *action*. Not political action, which he failed miserably in, as Mirabeau complained bitterly about when Philippe left for England and basically sabotaged his own chance for success, but physical action. The man HAD to be on the spot, he had to be doing something. It wasn't in his nature to lounge around. In some ways, he never gave up being the Duc d'Orléans, don't get me wrong on that -- he was a man who was very used to having certain privileges due to his station. But I also don't think that he would have sat by during the Revolution.

And what I'm getting at here is that the show doesn't get into any of that. Instead, we get an attempted sexual assault. Because Antoinette hasn't had enough of that in this show. I've noticed that people often want Antoinette to have endured more trauma than she actually did historically -- it's bizarrely common to have her be sexually assaulted and...look. The woman was already under enormous pressure to have sex at 14-15 years old, in a foreign country, without her family around her. She was subjected to public mockery, constantly surrounded by people scheming against her and who were willing to find fault with her for the slightest breach of etiquette. She lost two children, had a miscarriage, watched her remaining children being taken away, and that's before you get into her actual imprisonment. It isn't to say she's a martyr, it isn't to say she's a saint, but it is to say that her life doesn't need more trauma. Why do we keep insisting that we need to see her be raped, harassed, or assaulted on camera in order to get that Her Life Occasionally Sucked? It's cheap, it's voyeuristic, and it does her and Philippe both a disservice.

Would Philippe have gone for Antoinette? I don't know. There was about a seven year or so age gap between them. When Antoinette came to Versailles, he'd have been about 21-22 to her 14. During their falling out over Ouessant, she was 23, he was 30. Agnes du Buffon became Philippe's mistress when she was 26; de Genlis about 27; Elliott about 30. The man seemed to prefer, at least for steady mistresses as opposed to brief flings, intelligent, well-read women who were at least in their mid-twenties. He didn't like young girls. Not to say he couldn't surprise me; I try to always work with him with the understanding that he lived two hundred fifty years ago -- He's not my friend, I don't know him. But from the pattern...I'd say no.

Madame Campan had this to say about their dynamic:

[transcript: "The Duc d'Orléans, then Duc de Chartres, was among those who accompanied the young Queen in her nocturnal ramble: he appeared very attentive to her at this epoch; but it was the only moment of his life in which there was any advance towards intimacy between the Queen and himself. The King disliked the character of the Duc de Chartres, and the Queen always excluded him from her private society. It is therefore without the slightest foundation that some writers have attributed to feelings of jealousy or wounded self-love the hatred which he displayed towards the Queen during the latter years of their existence.]

She had no reason to lie and every reason to make Philippe as horrible as could be (and didn't hold off on ripping, for example, Lauzon.) Why hold back? If Philippe had ever behaved improperly, why not write it down?

One time where do see him in a case where a woman turned him down was with Moll Benwell, where we see:

[Transcript: The Duc de Chartres has made himself extremely ridiculous on her account, following her to all public places; to the contempt with which she treats him and his promises (which that nobleman is but too apt to make) she may attribute his constant attendance on her] (From: An Infamous Mistress: The Life, Loves and Family of the Celebrated Grace Dalrymple Elliott)

He followed her around pathetically, which would have to have been annoying. I wish we knew more of her perspective on this sort of thing. But this is...relatively par for the expected course of behavior. See also: the romantic treatment of Artois' stalking of Louise de Polastron, which appears to have been an innovation of her cousin's reminisces because according to Artois' own correspondence, she was his mistress by 1789. This was an expected part of courtship in the 18th century, there was an idea of how far you could and couldn't go, and Philippe seems to have stuck to that. (The entire thing reminds me of Baby It's Cold Outside Discourse, where someone once said something like "in a society where you can't say openly say yes, you also can't say no.") The memoirs of Leonard, ostensibly by Marie Antoinette's hairdresser, show him having a thing for Rose Bertin and being aggressive towards her -- that book was published eighteen years after Leonard's death and its authenticity has been widely called into question. Am I saying it's impossible? Absolutely not. Philippe was a powerful man. It'd be very easy to develop a sense of entitlement. If any solid evidence comes up, I won't defend him. What I AM saying is that there is no evidence of it when both sides of the Revolution, at varying times, wanted every ounce of dirt they could get on him. (Unlike with Danton, where Elisabeth de Bas admitted that he had preyed on her.)

It's just...it's cheap. People want Philippe to be a Villain™ but they don't want to put the effort in to explain how he becomes one or how his villainy functions, so they just make him a misogynistic incel and call it a day.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le Parc Monceau

Ce poumon vert du VIIIème arrondissement, bordé par le très chic boulevard de Courcelles formant frontière avec le XVIIème, est entouré de riches hôtels particuliers du XIXème et de luxueux immeubles haussmanniens. Surplombant un centre de formation de la RATP (au sein de l'ancien terminus en boucle de la ligne 3), il offre aux joggers une autre boucle d'un kilomètre tout pile (en évitant l'aire de jeux de son coin nord-ouest), il propose aux enfants bourgeois du quartier un carrousel, des balançoires (chantées par Yves Duteil) et des balades à poney, tout en affichant aux promeneurs un dépaysement certain, de par ses nombreux aménagements et fabriques de jardins héritées de son original passé.

Monceau n'est point vallonné (comme sa toponymie pourrait nous le laisser croire) mais bien plat, la plaine de Monceau étant une altération du nom du précédent village de Mousseau. Le duc de Chartres, Louis-Philippe d'Orléans (futur Philippe-Egalité à la Révolution et père de Louis-Philippe, dernier roi des français sous la Monarchie de Juillet), acquiert en 1769 un vaste terrain sur cette plaine, alors située en dehors de Paris, afin d'y établir une "folie", selon la mode alors en vogue (cf. article sur l'Hôtel Salomon de Rothschild décrivant la "Folie Beaujon"). Il fait édifier par l'architecte Louis-Marie Colignon un large pavillon octogonal à deux étages, que l'on nommera par la suite la "Folie de Chartres", entourée d'un vaste jardin à la française. Le duc charge dans les années 1770 le paysagiste écossais Thomas Blaikie de transformer ses jardins dans le style anglo-chinois, et le peintre et décorateur Louis Carrogis de Carmontelle de l'agrémenter de nombreuses fabriques ornementales de styles divers et variés, alliant exotisme et romantisme. On y trouve alors une fermette suisse et un moulin hollandais, une pagode chinoise et de fausses ruines médiévales, un minaret orientalisant, des pastiches de vestiges de colonnes travestissant la Grèce antique, un temple en marbre blanc dédié à Mars (dieu romain de la guerre), transformé sous la Restauration monarchique en "Temple de l'Amour" et déplacé au bout de l'Ile de la Jatte à Neuilly-sur-Seine, où il se trouve toujours... Subsistent de nos jours au Parc Monceau un faux sarcophage, un obélisque et une pyramide inspirés de l'Egypte ancienne, symboles maçonniques s'ils en sont, le duc de Chartres étant franc-maçon et grand-maître d'une loge créée à son instigation, sa pyramide abritant alors une statue de la déesse Isis (représentation absolue du culte de la déesse), et son pavillon ayant servi -paraît-il- à de nombreuses initiations... La "naumachie", bassin dédié aux reproductions de batailles navales à échelle réduite sous l'Empire romain, a également été préservée. Entourée d'une colonnade semi-circulaire dotée de chapiteaux corinthiens érodés par le temps, avec entablement (visible ci-dessus), il s'agit de fait du seul "vestige" archéologique avéré, trouvant son origine dans l'architecture de la Rotonde des Valois, vaste chapelle circulaire latérale attenante à la Basilique de Saint-Denis, voulue par la reine Catherine de Médicis en 1559, afin d'accueillir le monument funéraire de son défunt royal époux Henri II, puis de toute la dynastie des Valois à sa suite... Projet qui n'aboutit finalement jamais, les Bourbons succédant aux Valois, la Rotonde fût délaissée, abandonnée, puis finalement détruite en 1719. Carmontelle récupéra alors ces éléments architecturaux la composant (grand bien lui fit!) Le duc, s'engouffrant par la suite dans les affres de la Révolution, changeant son patronyme en Philippe-Egalité, votant pour la mort de son cousin Louis XVI (!), ne put toutefois pas échapper à la guillotine, le décollant en novembre 1793. Ses jardins et sa folie deviennent alors propriété de la ville de Paris, nouveau lieu de fêtes publiques accueillant excès en tous genres et exploits sportifs, comme ce premier saut en parachute de l'histoire, exécuté en 1797 par l'aérostier André-Jacques garnerin, sautant de sa montgolfière à plus de 1000 mètres d'altitude et se posant en douceur au coeur du parc! Lequel parc est restitué en 1802 à la famille d'Orléans, qui fait démolir l'ancienne folie. Napoléon III (par le truchement de son sbire parisien le baron Haussmann) exproprie de nouveau les Orléans en 1860, réduisant le parc de 18 à 8,4 hectares, permettant le percement du boulevard Malesherbes et le lotissement du nouveau quartier de la plaine Monceau, accueillant par la suite la haute bourgeoisie d'affaires du Second Empire. De cette époque datent les luxueuses allées semi-privées bordées de somptueux hôtels particuliers, propriétés de grands noms de la finance et de l'industrie, tels que les frères Pereire, le chocolatier Menier, Cernuschi (article précédent), Camondo (article à venir)... Chacun ayant sa propre grille d'entrée privative menant au nouveau Parc Monceau. L'architecte Gabriel Davioud le ceinture de monumentales grilles en fer forgé, surmontées de candélabres, tandis que l'ingénieur Adolphe Alphand y crée une rivière artificielle enjambée par un pont devenu iconique, ainsi qu'un monticule surmonté d'une cascade, abritant une grotte arborant les premières stalactites en ciment artificiel. Le Parc Monceau devient donc un laboratoire de création préfigurant les aménagements paysagers parisiens à venir des parcs Montsouris et des Buttes-Chaumont, ainsi que ceux des Bois de Boulogne et de Vincennes.

La répression de l'insurrection de la Commune de Paris ayant déclenché l'incendie de nombreux monuments parisiens, dont son Hôtel de Ville, une arcade encadrant l'un de ses deux porches d'entrée, sauvée des flammes, trouva sous la IIIème République naissante son gîte final en surplomb d'une allée du Parc Monceau, apportant un deuxième vestige de la Renaissance française (l'ancien hôtel de ville de Paris, du ciseau de l'architecte italien Boccador, datait en effet du XVIème siècle). A la Belle Époque, plusieurs monuments statuaires furent érigés sporadiquement sur les pelouses du parc, glorification post-mortem des artistes résidents voisins, promeneurs célèbres de Monceau, de Chopin à Gounod, de Musset à Maupassant... Dernière adjonction monumentale en date, la lanterne japonaise 'toro', datant de 1786, don du Japon à la France en 1982, symbole d'un pacte d'amitié entre Tokyo et Paris, sous le mandat de son maire d'alors Jacques Chirac, fervent défenseur de la culture nippone, trouvant ainsi un écrin historiquement emprunt d'exotisme, qui plus est à deux pas du Musée Cernuschi, dévolu aux arts asiatiques. Mentionnons encore son patrimoine végétal, riche de nombreux arbustes et arbres remarquables, dont un splendide gingko biloba daté de 1879, ainsi qu’un exceptionnel platane d’orient, planté ici en 1814, atteignant aujourd’hui 31 mètres de hauteur pour un tronc d’une circonférence à sa base de près de 7m, ce qui fait de lui l’arbre le plus gros de Paris.

L'entrée principale du Parc Monceau (tout proche de la station de métro éponyme) consiste en deux grilles de part et d'autre d'une rotonde (dite "de Chartres", en mémoire de l'ancienne folie du duc de Chartres), surmontée d'un dôme, surmonté d'une girouette, surmonté d'un paratonnerre. Il s'agit d'un monument, datant également de 1786, ancien pavillon d'octroi d'une enceinte de Paris élevée à la fin du XVIIIème siècle, le Mur des Fermiers Généraux. Ponctué de soixante barrières, comme autant de portes d'entrées dans Paris, chacune était sous le patronage d'un pavillon abritant les bureaux des services chargés de collecter l'octroi, taxe sur les denrées entrant et sortant de la capitale, hautement impopulaire à l'époque (d'ailleurs l'une des causes d'agitations populaires ayant conduit à la Révolution). Elevés par l'architecte Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, dans un style néoclassique monumental contrastant avec la fonction première des bâtiments, il n'en reste plus que quatre aujourd'hui, dont celui-ci, ayant pour particularité de ne pas consister en une barrière à proprement parler, car aucune marchandise n'entrait ni ne sortait alors par la barrière de Chartres, emprise sur la folie du futur duc "Egalité", celui-ci ayant demandé à Ledoux une "galanterie" architecturale lui permettant l'accès à une plate-forme d'observation de ses jardins... Cette monumentale rotonde accueille aujourd'hui la loge des gardiens du Parc, ainsi que des commodités publiques... Ou comment les monuments se transforment au fil du temps...

#parc#Monceau#parc Monceau#monument#folie#duc de chartres#pavillon d'octroi#rotonde#colonnade#barrière#entrée#promenade#arbres#ruines#patrimoine#histoire#architecture#paysage#culture#vestiges#saut en parachute#Paris#8ème#chic#photography#photo#photooftheday#Second Empire#Revolution#Renaissance

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1817 Adèle Tornézy-Varillat - Ferdinand-Philippe Louis d'Orléans, Duc de Chartres

(Private collection via Sotheby’s)

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Louis-Philippe and His Sons, the Dukes of Chartres and of Némours, Baron François-Pascal-Simon Gérard, c. 1830–1832, Minneapolis Institute of Art: Paintings

Louis-Philippe, King of the French, Ferdinand Philippe Louis Charles Henri, Duc d'Orléans, and Louis Charles Philippe Raphaël d'Orléans, Duc de Némours. Louis-Philippe became King of France following the Revolution of 1830. He was dethroned during the international uprisings of 1848, which caused widespread social disruptions such as that recorded by Daumier in his bronze relief above. Size: 13 3/4 x 10 7/8 in. (34.93 x 27.62 cm) (canvas) 9 7/16 x 15 7/8 x 1 7/8 in. (23.97 x 40.32 x 4.76 cm) (outer frame) Medium: Oil on canvas

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/1531/

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philippe I, Duc d'Orléans (Philippe de France)

Philippe I, duc d'Orléans was born on September 21, 1640 in Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France. His parents were King Louis XIII [1601-1643] and Queen Anne of Austria [1601-1666]. He had one elder brother, King Louis XIV [1638-1715].

In 1661 he married Henrietta Anne of England [1644-1670]. Together they had four [4] children: Marie Louise d'Orléans [1662-1689], Philippe Charles d'Orléans, Duc de Valois [1664-1666], stillborn daughter [July 09, 1665], and Anne Marie d'Orléans [1669-1728]. After Henrietta's death, Philippe married Princess Elisabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate [1652-1722] in 1671. Together they had three [3] children: Alexandre Louis d'Orléans, Duc de Valois [1673-1676], Philippe II, Duc d'Orléans [1674-1723] and Élisabeth Charlotte d'Orléans [1676-1744].

Philippe was styled the Duke of Anjou from birth. He became the Duc d'Orléans in 1660 after the death of his Uncle Gaston. In 1661 he also received the dukedoms of Valois and Chartres, and the lordship of Montargis. Following his victory in battle in 1671, Louis XIV gave him the dukedom of Nemours, the marquisates of Coucy and Folembray, and the countships of Dourdan and Romorantin. Upon the death of Mademoiselle in 1693, Philippe acquired the dukedoms of Montpensier, Châtellerault, Saint-Fargeau and Beaupréau. He also became the prince of Joinville, Count of Mortain, Bar-sur-Seine, and Viscount of Auge and Domfront. Philippe was also given the nickname of "the grandfather of Europe."

He was a successful military commander during the War of Devolution in 1667. In 1676 and 1677 he took part in the sieges in Flanders, and was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant General. The most impressive victory won under Philippe's command took place on April 11, 1677: the Battle of Cassel against William III, Prince of Orange.

Philippe de France died on June 09, 1701 (aged 60) in Château de Saint-Cloud, France. The cause of death was from a fatal stroke. He was laid to rest on June 21, 1701 at the Basilica of Saint-Denis, France

#french history#history#royalty#personal life#philippe i duke of orléans#philippe of france#duc d'orléans#duke of orleans#philippe I#titles#military#world history

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Françoise-Marie de Bourbon, legitimated, known as Mlle de Blois in wedding dress. Daughter of Louis XIV and Mme de Montespan, she married Philippe d'Orléans, duc de Chartres and died in 1749.

#Françoise-Marie de Bourbon#royaume de france#maison de bourbon#royal bastards#full length portrait#mademoiselle de blois#bourbon orleans#maison d'orléans#fils et filles de louis xiv#légitimée de france#légitimés et légitimées de france

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“No, I am not avoiding you, Philippe,” you replied slowly, bringing a hand up to massage your temple. “I simply want to change before I get sick.” Chartres watched you, his mischievous expression turning into a concerned frown. He took your other hand, brushing a soothing thumb over your knuckles. “Truth be told, you already do not look too well. It is not just the rain, is it?” You stared back at him. You had allowed him to grow far too close to you and now he could see more than you would like. You had to find something to keep him off track. You sighed purposedly. “Alright, I will admit, I have become ill during my stay in the Château de Caylus. I cannot say I recommend the Marquis’s hospitality.” You smiled wryly and Chartres grinned back. “Recovery has been a little difficult, that is all.” The Duc nodded, seemingly buying your lie. “Alright,” he concluded with a sigh. “Then please take your time to rest and come back to us in full health. I will let you go change.” He stood, opened the door, and started to exit the carriage, but as he was balancing himself on the foothold, he turned around, leaning in with a suggestive smirk. “… Unless you wish my help for the undressing part?”

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The only things I knew about Louis-Philippe were that he brought back Napoleon’s remains in 1840 and that he had a handsome son named Prince de Joinville. L-P fought in the Republican Army and served under MacDonald, Davout, Oudinot, Berthier, Mouton. He left France due to the danger of being a royal during the Revolution (his father was guillotined even though he was a Republican). He lived in exile for many years in different countries, including Norway, the USA, Cuba, Switzerland, and England. He sometimes worked as a schoolteacher. He returned to France at the Bourbon Restoration and became King after the abdication of Charles X (1830). After a long period of unpopularity he abdicated and fled France because there was another revolution (1848) and lived in England for the rest of his life. He was very handsome as a young lad!

Louis Philippe d'Orléans, duc de Chartres en 1792 by Leon Cogniet

Louis-Philippe, roi des Français by Franz Winterhalter

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gif Request Meme - A Musical of my Choice + a Villain: Artois and Orléans

↳ Requested by @fallenidol-453

Philippe Égalité: The only legitimate son of the Duc d’Orléans, a prince du sang from birth, Philippe was a very unlikely revolutionary. And yet Philippe showed a strong level of compassion for the lives of the lower class, going down a coal shaft to see the conditions faced by miners, pulling a groom of his from a river with his own hands, and providing shelter for the poor during the bitter winter of 1788-89.

He was noted for his extravagant lifestyle; a noted lover of racehorses, gambling, architecture, his various and assorted mistresses, and all things English. Despite being the richest man in France, with a truly astronomical income, he nonetheless found himself frequently in debt. That was the impetus for him to totally redesign the Palais Royal over the course of two and a half years, opening it up to shopkeepers and establishing it as a major area for counter revolutionary activity, with the police being banned from intervening. As such, an overwhelming feeling of liberty prevailed there, with people from all social classes gathering to observe the spectacles and walk along the gardens there.

There was a certain amount of hostility to be expected between the two branches of the Bourbon family, going as far back as the first Duc’s tempestuous relationship with his brother, Louis XIV. Still, the relationship between Louis XVI and Philippe gradually deteriorated over time, despite several attempts to patch things up. Orléans blamed Louis for the loss of his naval career, with the controversial Battle of Ushant in 1778 being a major breaking point in their relationship. In 1788, he spoke up at a “Royal Sitting” where Louis tried to press the Parliament into obeying his will, saying “Sire, this appears to be illegal.” Louis responded, “It is legal, because I wish it to be so.” Orléans spent the next five months in a comfortable exile at his estate, and he returned more popular than ever.

When the Estates General was called, Orléans sided with the Third Estate, taking his place with the other delegates rather than sitting with the Royal Family as his rank entitled him to. His name was consistently brought up alongside revolutionary activity, with his bust being paraded alongside Necker’s on July 12, 1789, when the rash charge of the Prince de Lambesc into the Tuilleries heightened the people’s fears over an armed crackdown of Paris. It would be in the Palais Royal where Camille Desmoulins would jump on a table and call the people to arms, and even though the exact impact of that statement’s been disputed, the fact that Palais Royal was a huge locus point for revolutionary activity never has been.

Among the royalists, it was popularly thought that Orléans was behind the entire Revolution, masterminding the Storming of the Bastille, the Women’s March to Versailles, a famine, and various and assorted other disturbances, in lieu of believing that the common people themselves were discontent. However, the sources nearest and dearest to Philippe suggest that he had no intention of seizing power, and Philippe’s own action of going and staying in England at Lafayette’s suggestion between October 1789 and July 1790, when he had a strong chance of fighting back against the charges and seizing power for himself by riding off the highest point of his popularity, strongly indicates that he had no intention of seizing the throne for himself. Overall, while he was a man of undeniable courage, the popular consensus is that he was, by nature, too passive to do it on his own, generally being very diffident to those near him such as his former mistress and longtime friend, Madame de Genlis, as well as her rival for his attention, Pierre Ambroise François Choderlos de Laclos, and generally disinterested in long-form plans, preferring to throw himself into whims. It is far more likely that, if a plan existed to make Philippe king, it came from one of those brains, as opposed to anything Philippe himself considered in any detail.

He did, however, become embittered over the increasingly chilly reception he received at Versailles, including one occasion where a courtier shouted “Do not let him touch the wine!” when he entered, with him then being spat on as he made his leave.

In the latter half of 1792, Philippe faced a bevy of problems, both personal and political, as his long-suffering wife had filed for a separation, his daughter was put on a list of émigrés and was forced to leave the country very shortly after arriving (after Madame de Genlis, who he had instructed to take her back before her name could be added, lingered for too long, causing a final breakdown in their long relationship), his popularity was rapidly fading, and he had been called, as a Deputy of the National Convention, to sit at the trial of his cousin. According to one anecdote, found in William Cooke Taylor’s Memoirs of the House of Orléans, it was in that particular maelstrom that he changed his name, as a last ditch effort to save his daughter and prove his loyalty to the Revolution, to Philippe Égalité. Many options were considered for him to not sit the trial, and there is no reason to believe, despite the long-lasting enmity that the two of them had, that Philippe, when he went to sleep the night before the trial of Louis began on December 26, that he had any idea that when it came time to give the verdict on January 14-15, he would vote “yea,” a decision that shocked the entire room, not the least Louis himself. Perhaps it was a last ditch effort to save himself, perhaps he felt pressured to do it by everyone else in the room, perhaps in that moment he truly believed that Louis’ actions merited the death penalty. It’s impossible to truly know, but in the end that one decision, more than anything else, has defined his legacy.

However, the Royalists would soon be able to find some comfort, as, on the 4th of April 1793, his son, Louis-Philippe, Duc de Chartres, defected along with General Dumouriez, and Philippe’s enemies had the ammunition they needed.

On 7 April, 1793, he was arrested and sent to Fort Saint-Jean in Marseilles, along with two of his sons. Throughout his imprisonment, Philippe kept up an optimistic front, constantly reassuring his sons, the Duc de Montpensier and the Comte de Beaujolais, on the rare occasions he was allowed to speak to them after they were separated, that everything would turn out well, even expressing optimism about his trial in Paris. Whether this was real or simply an attempt at keeping up morale will never be known, but on November 2, 1793, he was sent back to Paris, to be imprisoned in the Conciergerie. He was tried on the 6th and, at his own request not to prolong things any longer than necessary, he was executed on that same day. By all accounts, he met his death courageously, his composure only threatening to break when the cart he was in stopped in front of the Palais Royal, so that he could very clearly see the sign on it that said it was now national property. His last words were to stop the assistants at the guillotine from taking off his boots, saying “You are losing time, you can take them off at a greater leisure when I am dead.”

Unlike his royal cousins, his body was never found, and to this day, he is generally considered as one of the great villains of the Revolution in media associated with it, though none of the serious charges against him (the October Days being prime) were ever proven.

Charles X- For most of his younger years, like his older cousin, Charles’ defining quality was his wild life, which was punctuated by multiple love affairs, copious gambling and alcohol, and even more copious debts, with his brother, Louis XVI, somewhat reluctantly paying the bills. He also had a close friendship with his brother’s wife, who he shared a love of high living with, the two of them often being seen together at the theatre and balls. This close friendship was much remarked upon, with Artois being a frequent subject of the pornographic pamphlets that circulated about the queen, along with Marie Antoinette’s favorite, Madame de Polignac. In the years preceding and following the Revolution, however, the two of them gradually cooled, with their later relationship being marked by political disagreements. Charles consistently pressured his brother into more conservative stances during the meeting of the Estates General, arguing against doubling the Third Estates’ representation and conspiring to get rid of Louis’ liberal finance minister, Jacques Necker. The dismissal of the Necker would end up being one of the leading causes for the Storming of the Bastille, with Charles’ temporary personal victory being quickly eclipsed by the blaze that the little spark of Revolution had turned into. In the days immediately following the Storming of the Bastille, Artois was ordered to emigrate by his brother, along with the rest of his family.

He wouldn’t see France again for decades, going from court to court in Europe asking for help and trailed by a small army of creditors (who would become some of his most frequent companions, the avid huntsman only being able to go out riding at his estate at Holyrood on Sundays, when his creditors would be unable to pursue him), but with very little materializing, even less of which was successful, with the Battle of Quiberon being particularly disastrous to any hope of a royalist win by military might. Instead, he set up his main residence in London, with his mistress, Louise de Polastron, sister-in-law of Madame de Polignac, upon whose death he swore a vow of celibacy, the former playboy becoming sober and religious in his later years. The family briefly returned to France in May 1814, with the exile of Napoleon to Elba, however his later escape and mustering of the troops led to them leaving the city in February 1815, only able to fully establish themselves back in the country shortly after Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo. Upon his brother, the Comte de Provence’s ascension to the throne as Louis XVIII (the space between XVI and XVIII being taken up by Charles’ young nephew, Louis-Charles, who died in prison and therefore never ruled), Charles became known as a leading member of the Ultra Royalist faction, who were, as the name suggests, “More Royalist than the king.” His brother dying without a male heir, Charles took the throne in 1824, though his highly conservative policies following his more tolerant brother’s reign made him highly unpopular with the public.

In 1830, he was forced to abdicate. His intent had been for the throne to go to his young grandson, however, it would go to Louis-Philippe, Duc d’Orléans, the son of Philippe Égalite (who would himself end up being deposed.) He spent the remainder of his life similarly to how he spent his exile, traveling from place to place, hounded by debtors.

Eventually, he would die in Austria, on 6 November 1836, 43 years to the day of his revolutionary cousin’s execution.

Sources:

The Chevalier de Saint-Georges: Virtuoso of the Sword and the Bow: Gabriel Banat

A French King at Holyrood: Alexander John Mackenzie Stuart

The Journalists and the July Revolution in France: The Role of the Political Press in the Overthrow of the Bourbon Restoration 1827–1830: Daniel Rader

Memoirs of the House of Orléans: William Cooke Taylor

The Perilous Crown: France Between Revolutions, 1814-1848: Munro Price

Prince of the blood : being an account of the illustrious birth, the strange life and the horrible death of Louis-Philippe Joseph, fifth duke of Orleans, better remembered as Philippe Egalite: Evart Seelye Scudder

Revolutions in the Western World 1775–1825: Jeremy Black, ed.

#perioddramaedit#asiantheatrenet#musicaltheatreedit#historyedit#1789 les amants de la bastille#marie antoinette das musical#keigo yoshino#mitsuo yoshihara#long post#ch: artois#Production: Toho#other musicals: MA#historical#on this day in history we mourn the death of two thots#one more than the other#(apologies if I smudged any facts given that it is rather late)

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

AN INCOMPLETE HISTORY OF MEDIEVAL ART LIX

Nôtre Dame de Paris

The fourth of five posts on the long, complex history of the Cathedral of Nôtre Dame.

IV. The Nineteenth-Century Restoration

Sans doute, c’est encore aujourd’hui un majestueux et sublime édifice que l’église de Notre-Dame de Paris. Mais si belle qu’elle se soit conservée en vieillissant, il est difficile de ne pas soupirer, de ne pas s’indigner devant les dégradations, les mutilations sans nombre que simultanément le temps et les hommes ont fait subir au vénérable monument. Victor Hugo, Nôtre Dame de Paris, 1831.

Restaurer un édifice, ce n’est pas l’entretenir, le réparer ou le refaire, c’est le rétablir dans un état complet qui peut n’avoir jamais existé à un moment donné. Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

Victor Hugo’s novel, Nôtre Dame de Paris (1831) drew attention to the deplorable condition of the Gothic cathedral of Paris. The novel’s success was partvof a reawakening of interest in medieval art and history, which had long been denigrated and ignored. In 1841, recognizing the nationalistic value of a monument created in an indigenous French style, the July monarchy formed a committee to gather professional opinions concerning the 700 year-old edifices’s condition. Based on the committee’s findings, in 1844, King Louis-Philippe ordered a sweeping preservation program including the complete restoration of Nôtre Dame and the construction of a new sacristy.

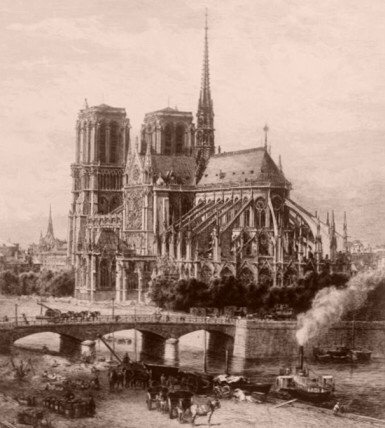

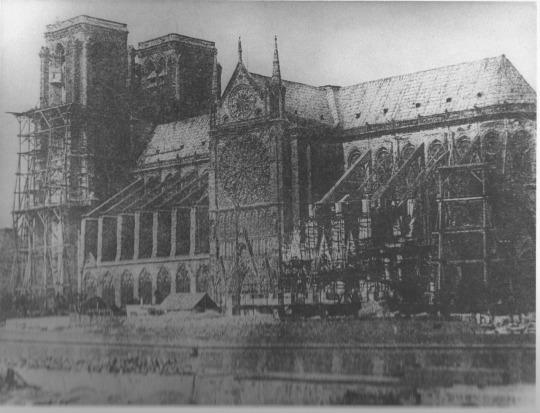

above: Nôtre Dame as construction site, c. 1850

The architects chosen to rebuild Nôtre Dame, Jean-Baptiste Lassus and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, had just completed the restoration of the Sainte Chappelle. Prior to that Viollet-le-Duc had also rebuilt the monastic church of Vézelay, which saved it from imminent collapse. Other than experience, there were few established protocols or resources to consult concerning the restoration of medieval buildings and the scope of the Nôtre Dame project was daunting: the mortar binding the ashlar masonry had eroded to the extent that pieces of stone fell to the ground on a daily basis. The stained glass of the clerestory had been replaced with 18th-century grisaille glass. After centuries of neglect, during the violent period of the Revolution, the cathedral had been deconsecrated and its sculpture defaced or crudely hacked off the building by the mobs. The crossing spire had been declared unstable and removed in the 1830s. The bishop’s palace was crumbling into the Seine.

above: The Ile-de-la-Cité c. 1830

In the Conseils pour la restauration en 1849, the co-authors Viollet-le-Duc and the Inspecteur Général des Monuments Historiques, Prosper Merimée, state that:

Les architectes attachés au service des édifices diocésains, et particulièrement des cathédrales, ne doivent jamais perdre de vue que le but de leurs efforts est la conservationde ces édifices.

In practice st Nôtre Dame, however, Viollet-le-Duc’s approach to historical monuments restoration was idealist and holistic. For him, the cathedral’s form existed independently of the materials that composed it at any given time; therefore the form, and not the materials, were the object of restoration. The medieval building fabric would be replicated, but the retention of original stone and glass was not essential. Gothic masonry could be recut or removed to implement a gothicizing solution that harmonized better with the totality of the building, or redesigned, if necessary, to assure structural and or aesthetic integrity. Where there was doubt about original appearances or configurations, other Gothic cathedrals would serve as models. The result would be half recreation of the historical cathedral of Paris, half catalogue of 19th-century conceptions of architectural and sculptural ideas current in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. A delapidated medieval building was transformed into a crisply pointed allegory of medieval architecture.

above: Viollet-le-Duc and Lassus, Nôtre Dame façade, 1847

When Viollet-le-Duc visited Pisa, he found the sight of the torre pendente to be “désagréable” and opined that it should be corrected. The imperative to “correct” irregularities and errors in the original construction is a defining component of his restoration practice at Nôtre Dame. He and Lassus went far beyond conserving the Gothic fabric and repairing damage and wear. Over the long course of its construction, multiple medieval revisions to the design had resulted in many irregularities and discontinuities, which posed no threat to structural integrity. For example, the chapels between the nave buttresses had been added at different times in the 13th and 14th centuries and differed in size and decoration. Together they formed a micro-history of the evolution of Gothic chapel design within the broader narrative of cathedral design.

Viollet-le-Duc demolished the back walls of all of chapels and rebuilt them to a uniform size to be flush with the buttresses and applied a generic decorative program across them all. This imposition of anachronistic notions of visual consistency deprived the building of massive amounts of 13th-century masonry and decorative carving and gratuitously obliterated a bit of architectural history. In the equally destructive “correction” of the perimeter wall of the ambulatory, a delicate business involving the shifting and rebuilding walls while they supported the vaults, excised still more medieval stone. As a result of these needless interventions, the lower level of the exterior masonry, which wraps around the entire building, is entirely 19th century work. This high-handed approach is an example of historical destruction, not preservation.

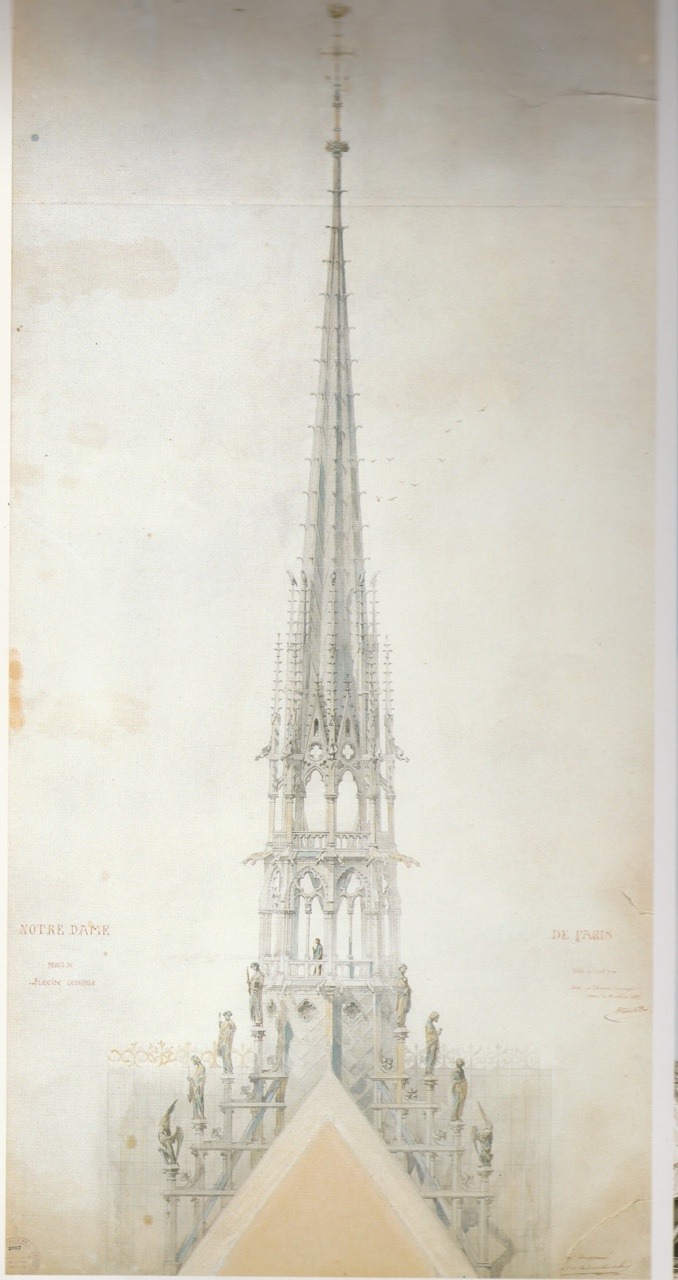

above: Viollet-le-Duc, design for Nôtre Dame flèche, c. 1855

Lassus and Viollet-le-Duc believed that the cathedral was incomprehensible without its sculpture and stained glass and insisted in their proposal that all of the stone sculpture be restored. As no reliable visual record of the sculptures existed, the team of 23 stone carvers were instructed to find and copy equivalents at Chartres, Reims, and Amiens. Based on different models, carved by numerous artists, at different times, the resulting “program” was unified by obliging the sculptors to work in a singie communal style. The sculptures of the façade formed a survey of Gothic cathedral sculpture that was then averaged and masked. The “restored” jamb figures did not replicate the originals nor did their style correspond to any historical medieval practice. The sculpture of the west portals are a misleading, medieval-flavored pastiche that blur rather than sharpen the view into French history supposedly provided by the cathedral.

When it showed signs of imminent collapse, the thirteenth-century spire had been removed in the 1830s. The plan submitted by the architects to the planning committee had included steeples, which had been planned in the Middle Ages but never built, but made no provision for restoring the spire. After the steeples were harshly criticized and dropped from the plan, the spire was added, relatively late in the project, to create a vertical accent. The absence of accurate, detailed images of the original did not stop Viollet-le-Duc from devising a convincing structure that represented a “typical” Gothic spire, but one that had no meaningful connection to the building. All the uninformed post-fire blather about the “iconic” spire completely misses this point.

The restoration of Nôtre Dame was completed in 1864, 20 years after it was launched. Lassus had died in 1857 and Viollet-le-Duc had become a celebrity, moving on to even larger projects like the restoration of the entire walled city of Carcassone. The cost of the cathedral restoration had been estimated at 2.6 million francs; in the end, it exceeded 10 million.

#historical preservation#restoration#viollet le duc#medieval architecture#gothic cathedral#nôtre dame#paris

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

One more light

by redangeleve

„Verzeiht die Störung, Chevalier“, sprudelte es aus dem Duc de Chartres heraus, ohne dass sich der junge Mann mit einer Begrüßung aufgehalten hätte. „Meine Mutter schickt mich. Ich soll Euch sagen, dass, wenn Ihr Vater noch einmal sehen wollt, Ihr Euch gleich auf den Weg machen müsst. Der Arzt sagt, dass er die Nacht wohl nicht überleben wird.“

Words: 2982, Chapters: 1/1, Language: Deutsch

Fandoms: Versailles (TV 2015)

Rating: Teen And Up Audiences

Warnings: Major Character Death

Categories: M/M

Characters: Chevalier de Lorraine (Versailles 2015), Philippe d'Orléans | Monsieur (Versailles 2015), Philippe II duc de Chartres

Relationships: Chevalier de Lorraine/Philippe d'Orléans | Monsieur (Versailles 2015)

from AO3 works tagged 'Versailles (TV 2015)' http://bit.ly/31jKnbt via IFTTT

2 notes

·

View notes