#pawns can capture on the a file from the h file

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Attention math and chess nerds: i have discovered a chess variant called cylinder chess! As the name implies, its chess but the board is a cylinder - the a file and the h file are next to each other. There is an website called cylinderchess.com if you want to mess around with it!

#chess#math#topology#cool chess#someone check it out!#its like normal chess#but its on a cylinder#this means the queen can deliver double checks by herself#the piece values are gonna have to be reevaluated#every diagonal is a long diag for bishops#queens can double check#rooks are connected even with a piece “inbetween” them#pawns can capture on the a file from the h file#knights are.... mostly the same

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

actually no i WILL elaborate re: #and the punchline is: salem’s playing the dragon variation (here)

ok. so. rwby’s chess motif is chiefly there to foreshadow and then articulate the paradigm shift that occurs between salem and cinder in V8; insofar as any other characters are involved in the chess symbolism it is largely in service of clarifying what’s being said about those two. but first we have to talk about

✨chess theory✨

for context. some basics. briefly.

if you’re not a Chess Person you probably have at least a vague idea of what the pieces are, how they move, and their relative value. but that’s as good a place as any to start, so:

a chessboard has numbered ranks (rows) 1-8 and lettered files (columns) a-h. you can notate a specific square this way: a1 is the dark square in the bottom left corner of the board. white’s pieces start on 1, black’s on 8. the queens start on the d file, the kings on e. pieces that start on a,b,c are called the queen’s or the queenside and likewise pieces that start on f,g,h are the king’s or kingside.

from the edge of the board in, the pieces go on in this order: rook -> knight -> bishop. then the eight pawns start in ranks 2 and 7.

pawns (P) can move 1 square forward and capture pieces that are 1 square diagonally in front of them (so a pawn on the light square e4 can move to the dark square e5 if it’s empty, or capture a piece occupying the light squares d5 or f5). from their starting position only they are allowed to advance 2 squares if both are empty. they also have a special and highly situational pawn capture (en passant) that Isn’t Important but i have to mention it because it’s really fucking funny to catch the unwary with. look it up. they cannot move backwards, but if a pawn travels all the way across the board to reach the 8th/1st rank they can be promoted to a piece of the player’s choosing (knight, bishop, rook, or queen)—usually queen but there are certain circumstances where a knight is preferable.

rooks (R) move in straight lines vertically or horizontally across any number of unoccupied squares. if they land on an occupied square the piece is captured. rooks also have a special move they can perform with the king if 1. neither the rook nor king have moved yet, 2. the king is not in check, 3. the king would not move through or into check, and 4. every square between the rook and the knight is empty. this move is called castling and it moves the king two squares in the direction of the rook whilst jumping the rook over the king into the light square adjacent to the king’s new position. so if white castles kingside, the king moves e1 to g1 and the rook moves h1 to f1; if white castles queenside the king moves to c1 and the rook moves a1 to d1.

knights (N) move in an L shape (1 square either horizontally or vertically, then 2 squares at a right angle to the first direction, or 2 then 1), jumping over any pieces in between. if they land on an occupied square the piece is captured; pieces they jump over are not captured.

bishops (B) move in straight lines diagonally across any number of unoccupied squares, capturing a piece if they land on it. both players have a dark square and a light square bishop; bishops can never move onto squares of a different color from their starting square.

queens (Q) can move and capture like a rook or a bishop; so, in a straight line horizontally, vertically, or diagonally across any number of unoccupied squares.

kings (K) can move 1 square in any direction (outside of castling). if an adjacent square is occupied they can capture the piece. the king has the unique restriction that it cannot move into a square where it would be under attack, so if there is a white rook on b3 and the black king is on c2, b2 and c3 are not legal moves.

a piece is attacked when it occupies a square that could be taken by an opposite-color piece; if the king is attacked it is in check and the player must use their turn to get the king out of check (by moving the king, blocking the path of attack with a different piece, or capturing the attacking piece). the goal of chess is to checkmate the opponent by forcing the king into an inescapable check; you do not win chess by capturing the king, you win by trapping the king in a position in which your opponent has no legal moves.

(if the king is not in check but one player has no legal moves, the game is a stalemate and ends in a draw.)

so it’s not about overpowering the enemy… :)

anyway. chess pieces are conventionally given relative valuations (standard is P=1, N=3, B=3, R=5, Q=9) for the purpose of having a loose rule-of-thumb to quickly assess positions during a game. but—and this is the important part—piece valuations are only rough approximations of the actual strength any given piece might have on the board, because how strong or weak a piece might be is contingent on a lot of things. the queen isn’t always the strongest piece on the board; pawns are extremely important in the opening and can be really strong in the endgame. etc

so! chess strategy and tactics! basic ideas:

space—that’s how much of the board you control—is very important. space can be evaluated by counting up how many squares a player currently occupies or has attacked (including empty squares that an opposing piece cannot safely move into because they are in an attack line) on the opposing side of the board.

control of the center—d4,e4,d5,e5, the four squares in the center of the board—is achieved by developing pieces to attack those squares. controlling the center is the goal of the opening because the player with the strongest control over those four squares has the advantage in

initiative, which belongs to whichever player is able to attack in a way that their opponent has no choice but to respond, like putting a king in check or otherwise forcing the opponent to defend rather than develop their own position.

placing one piece on a square from which it can attack a square currently occupied by a friendly piece defends the friendly piece; if the opponent captures a defended piece and the defender captures the captor that’s called an exchange. a piece in a defensive position to more than one other piece, or a piece under more than one attack, is overworked and therefore weak.

the strongest piece on the board at any given time is a piece that: 1. can attack through the center, 2. is defended, 3. is not overworked, 4. is not closed in by friendly pieces, and 5. is able to capture, put the opponent king in check, or defend another piece doing those things.

ok! this:

is the setup for an opening called the sicilian defense, dragon variation. black has just moved the kingside knight’s pawn to g6 and will on the next turn move the kingside bishop to g7, then castle kingside. this is notoriously one of if not the sharpest openings—a risky, aggressive, highly tactical play. if you open with the dragon your intention is to spend the rest of the game attacking and counterattacking; ideally you keep the bishop on g7 and knight on f6 until you can capture with the knight and reveal the bishop’s attack up the long diagonal. in this game the fianchettoed bishop on g7 is THE strongest and most strategically and tactically important piece on the black side, to the point that every major line for white to counter the dragon aims to weaken the bishop.

ok done talking chess theory now

back to rwby:

in the essentials, the chess symbolism is constructed around the metaphorical game between salem (playing black) and ozma (playing white); the white king is the relics and the black king is remnant freed from the brothers, basically. and the black queen—

—isn’t cinder.

the black queen is a virus written by arthur watts which cinder deploys in tandem with the grimm and the white fang to shatter beacon’s defenses and keep ozpin’s guardians pinned down while she captures the fall maiden and then takes down ozpin.

and that’s the dragon. conceptually. cinder is the bishop fianchettoed on g7 biding her time until the black queen, knights, and pawns launch the attack on white’s queenside defenses and open the long diagonal for her to go in for the kill.

the same setup happens at haven except that this time cinder’s chief opponent is raven, who can see what cinder is doing and counters by baiting her into a more vulnerable position with a decoy and then whacking her.

and then it happens again in atlas, twice, first when cinder plants the black queen in ironwood’s office to force the winter maiden into the open and second when she remembers how this play actually works and gets watts and neo to tear open the line for her before she forces checkmate.

ironwood is the white queen, and he believes salem is the black queen—hence them being positioned as such in the V8 opener. he sees the black queen as salem’s calling card; ruby connects it to cinder. but the black queen is watts—his virus, his icon—and salem identifies herself in both 3.12 and 8.1 as the one playing black; beacon was the first move and it’s her game to win. cinder “holds the key to [salem’s] victory” and cinder is “more valuable to [salem] than a pawn,” so much so that salem values her more highly than the notionally higher-value queen.

because salem plays the sicilian defense, dragon variation. and. well,

…cinder’s the dragon.

#cinder ''anthropomorphic personification of a fianchetto'' fall.#cinder ''chess but in an ‘i will fucking immolate you’ way'' fall.

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Basics of the Chessboard and Pieces:

The chessboard and its pieces is the first step in your journey to mastering the game.

The Chessboard:

The chessboard is a square grid composed of 64 smaller squares, arranged in an 8x8 pattern. These squares alternate between two colours, typically black and white, creating a chequered pattern. The rows are called ranks, numbered 1 to 8, while the columns are called files, labelled a to h.

When setting up the board, make sure a white square is in the bottom-right corner of the board from each player's perspective. The pieces are then arranged in a specific order:

The Pieces:

Each player begins with 16 pieces: 8 pawns, 2 knights, 2 bishops, 2 rooks, 1 queen, and 1 king. Here’s a brief overview of each piece and how it moves:

Pawns:

Pawns move forward one square but capture diagonally. On their first move, they can advance two squares. Pawns are the only pieces that capture differently from how they move.

Knights:

Knights move in an L-shape: two squares in one direction and then one square perpendicular. They are the only pieces that can jump over other pieces.

Bishops:

Bishops move diagonally any number of squares. Each player has one bishop on a light square and one on a dark square, and they remain on squares of their colour throughout the game.

Rooks:

Rooks move horizontally or vertically any number of squares. They are powerful pieces when they control open lines.

Queens:

The queen is the most powerful piece, able to move any number of squares vertically, horizontally, or diagonally.

Kings:

The king moves one square in any direction. The primary goal in chess is to checkmate your opponent's king, putting it under attack in such a way that it cannot escape.

Setting Up the Board:

Pawns:

Place all pawns on the second rank for White and the seventh rank for Black.

Rooks:

Position the rooks on the corners of the board (a1 and h1 for White, a8 and h8 for Black).

Knights:

Place the knights next to the rooks (b1 and g1 for White, b8 and g8 for Black).

Bishops:

Position the bishops next to the knights (c1 and f1 for White, c8 and f8 for Black).

Queens:

Place the queens on their colour (d1 for the White queen, d8 for the Black queen).

Kings:

Place the kings on the remaining squares (e1 for White, e8 for Black).

Goal of the Game:

The objective of chess is to checkmate your opponent's king. This means putting the king in a position where it is under attack and cannot escape. Understanding the basics of the chessboard and pieces is essential for developing strategies to achieve this goal.

0 notes

Text

@tzdkh gets a drabble

there’s a slight tint of yellow to the sky as the sun begins to pull itself up along the horizon, just begging to reach up against the edges of the mountains that surrounded this quaint montanan town. dean can understand why deacon remains here. there may be no room for growth, there may be that feeling of laziness that hung in the air like a blanket of low hanging clouds that refused to budge, but dean found himself embracing that particular attitude the more he lingered in the area. people were content here, happy with their life and how they lived.

how long had it been since dean had felt that way ?

with his breath getting heavier with each mile he pushed, the hunter kept his gaze towards the morning light. a thought crossed his mind. what would happen if he just remained on this path ? allowed his feet to stray from the pavement he was running on and took off over that distantly glowing line. no more aimlessly heading where his life decided to take him, instead taking control of the direction he wished to choose ? such an idea was almost terrifying with the unknowns it contained, but even with all those variables there’d be one constant. a direction, a goal. a pathway for the hunter to finally forge as his own.

slowing down as the yellow and white lines began to stray to the left, dean took the chance to catch his breath as he stared at the edges of the valley this county resided in. shoes toed the line of pavement and dirt while dean’s sweat slicked chest rose and fell with every gulp of air. how difficult would the journey be ? what trails would the winchester have to face for just the smallest feeling of control for once in the convulsed mess of a life he had.

he waited as the beginnings of light began to make themselves noticeable above the ridges of the mountains, dean having to shield his eyes as it became more difficult for him to watch the sunrise. eyes blinked as he tried to get rid of the flare of brightness from his sight, turning to see just how far he had gone on this particular journey. a small glint captured dean’s attention, traveling along the same road dean had just jogged. with his gaze turned away from the east, he watched the approaching glimmer that was clearly some kind of vehicle. it wasn’t clear who was following dean’s path until the car began to slow, windows rolled down to reveal a familiar face.

“ here to throw me in the back or do i get to ride upfront this time ? ” dean says, finding time to speak between his heavy breaths. the hand he had used to shield his eyes from the sun wipes away the sweat collecting on his brow as dean steps away from the curve in the road, feet returning to fully place themselves on the weathered asphalt.

there’s a smile on deacon’s face as they hear dean’s words, soft and forgiving. dean can’t help but to mimic the gesture. he promises that he was on his best behavior unless the notion of handcuffs is involved.

dean stares at the lines on deacon’s face while sitting beside him, remembering how their weathered skin felt against his fingertips. the touch had been soft despite the intensity of the thoughts bouncing around in that brain of his. time had passed without the trading of words, eyes wandering across each other’s faces as they watched the minute expressions that betrayed their thoughts. they spoke wordlessly in tandem —- to what lengths would i go for this man ? just what am i doing here ? does he know that i would die for him ?

as dean watches the deputy drive, he knows that the direction he chose doesn’t lay in the wilderness and mountains of hope county. there was no need to become a trailblazer, racing towards the unobtainable finish line he had longed for earlier this morning. there was already a path for dean to follow. while it may not be paved or be direct, it was laid out in-front of the hunter; just like the lines of deacon’s face dean had traced earlier, all roads he now travels end at the same destination.

a decision had been made, even if dean struggled to realize it. no longer was he letting the wind take him wherever it wished. the anemoi may wish to have their way with whisking the hunter away without any clear purpose, the moirai may try their best to dictate the winchester’s purpose without care, but dean had finally taken the matter of his life into his own hands for once. he had taken control finally, only realizing it in the exchange of silence.

he had already reached the horizon line —- now he just required the assiduity to remain.

there was a laugh from mary may as the body spun with a drunken flourish, only for another to safely catch them from falling over while the two continued to dance. their joy was refreshing, having seen this particular bar just a few weeks before wrought with tension. the air had been heavy, bearing down on people’s shoulders as they hunched over their drinks, unsure of what was to come in the following days. not even all the liquor provided by the spread eagle was able to wash away all the stress the people had carried. they had been a grim sight in what used to be refuge for those beaten and lost, but not even fall’s end’s popular watering hole was safe from the threat of the project.

and they were right to harbor that feeling of fear. it hadn’t even been a week when the project had decided to move against the town. the bar had received a few new scars during its occupation, like many of the residents, but time had helped heal those wounds.

fingers rapped against the counter in tempo to the music, an attempt to play the drums along with bob burns. dean knew he was probably butchering the part, but spirits where high and he had just enough drink to not worry about what others thought. eyes continued to watched the couple dance as the song began to end and they took a clumsy bow at the sound hands clapping. he quickly finished his drink, only a few drops left, before looking disappointedly at the empty glass. however help was on its way, as he found the gaze of the blonde behind the counter.

“ where’s your deputy ? ” the question was asked with a knowing smile on her face, even as dean’s eyebrows rose. his deputy ? he hadn’t been aware others had been talking like that. mary may seemed almost amused at his expression, filling his glass back to full with dean’s drink of choice. he voiced the question he asked in his head —- it still lingered there, rattling around as he still couldn’t quite process those words. his deputy. the only answer he receives is a pointed look to his head, her own brow raising in a way that told him she was questioning just how smart the hunter was. a hand reaches up to touch the brim of the hat he wore, allowing it to bring a smile to his face. the memory of how he had first liberated this hat played through his head. that day was the same day dean first set his sights on deacon saint. a too good deputy just trying his best during difficult times, who had his hands full the instant they tried to hold onto to dean winchester.

he presses a finger to his lips, playing coy about how he once more seemed to have come into possession of deacon’s hat. it was apparently no secret that the two of them were having their own kind of dance, a regular game of cops and robbers. there’s a roll of eyes in response, but her own smile doesn’t drop. “ you’re a troublemaker, but i’ll keep filling that glass of yours as long as you keep outta fights today. ”

dean rises to the bait as she begins to step away, turning to her other patrons that needed their own refills. “ just today ? think you can pencil me in tomorrow ? hey, wait ! how about thursday ? ” he calls out, only to receive two fingers pointer at her eyes before having them turned his way. a laugh escapes dean’s lips, picking up his refilled glass to take a sip. his deputy, dean muses to himself, feeling the burn of whiskey lingering in the back of his throat.

dean stays true to his word and is back in the following days. however there’s a distinct lack of applause and grins thanks to the news coming from the whitetail mountains. the militia was barely holding out, with every step forwards, the project forcing them another two back. while dean attempted to maintain a neutral position in the conflict —- he’s had enough of doomsday prophecies and people thinking they could use him to win wars ; if angels and demons could try and fail in their attempts to make the winchester their pawn, dean would rather die before some jumped up humans on hallucinogenic drugs toyed with his fate —- he knows deacon is doing his best in helping the citizens of hope county. dean will help the innocent, prevent those who want no part of this war from getting involved, but his loyalty lies with a single person.

both factions would be razed to the ground if anything happened to his deputy, no matter if that wasn’t what deacon would have wanted. dean could handle disappointment, he was used to being on the receiving end of that particular emotion, and he would sacrifice everything that made him happy to make sure nobody would even think about laying a hand on deacon saint.

even if that meant losing him.

the conversation is soft, making dean strain his ears to hear what’s being said. he doesn’t bother to look at them, the neon bar signs providing little light and with night already fallen, the dimness hardly allows for too many details to be seen. so dean focuses on how his fingers grasp the glass in hand and listens. there’s not much that dean doesn’t already know, having poked around the files the police force has.

there are flaws in their movements that are easily seen by the trained eye. growing up as a hunter, with his dad’s background in the marines, tactics come second nature for dean. he’s used to working in groups, moving people around that best suits their talents. while many in this county have some sort of military background, they’ve never had to deal with opponents that were consistently stronger and more prepared than they were. dean didn’t have much room to judge, but in most of their cases, they never really had the intelligence to be placed in a leadership position as well. they were sloppy, overestimating their own abilities while not giving the project the respect they deserved. another issue, dean had learned, was that they relied too heavily on the select few who did have talent while not providing the support they deserved —- and when things went wrong . . . well, the blame was easily thrown around.

“ maybe he’s just making things worse. ”

a simple comment, one that didn’t really hold any heat, but still introduced as a possibility.

the hunter’s eyes drift away from his drink and towards the group of men talking among themselves. mary may moves closer to dean, as if sensing the anger rising within him. he’s unsure what her goal is, but he dismisses the presence easily. listening a bit more intensely, there’s a few murmurs of assent, unsure if they agree with what’s being said, but allowing their idea to gain traction in their closed circuit of thoughts. if any of the other patrons heard what was being said, nobody speaks out and that only makes the matter worse.

“ what, you think your bitch ass could do any better ? didn’t know having a fuckin’ beer gut made you threatening. ”

words flow easily out of dean’s mouth, as glasses are cleared from the bar in preparation. the winchester name may not hold much sway as a hunter in this particular community, but those who frequent the spread eagle know dean and stay clear of him for different reasons. the trio that dean turned his attention to clearly hadn’t gotten the memo of why most people give dean a healthy radius. they rise to the bait with the idea they outnumber the blond. dean knows exactly what they’re thinking : he’s too pretty to be a threat, lacking muscle definition and weight —- an easy target to let some of their frustrations out on. the stooges don’t notice the glances they receive are of worry, that people are slowly dissipating around them, not willing to get caught in the cross fire. they don’t hear the phone call from behind the bar asking for an ambulance for three.

what they do hear is the call for them to take their spat outside, dean agreeing as he continues to trade barbs, riling the group up more. He takes notice of their gait, watching how they move with a slight stagger —- one in particular had a shuffle to their step, giving away an old wound that never healed correctly ( dean files that away, knowing that limo was only going to be worse after this particular scuffle ) .

the night air is refreshing after being in a stuffy bar. dean takes his coat off along with the deputy’s hat, partially because he didn’t want to get them damaged, but also using it as a guise to remover the gun he keeps resting against the small of his back. there’s tension in the cool mountain air as the others wait for the hunter to square up. they laugh at his posture, refusing to raise his fists just yet and read it as a sign of weakness. dean knows the rattle against the window are those who placed bets, peaking between the blinds to see just who was going to win. he’s unsure who makes the last remark, but it’s the final straw. the slur they used against him is easily brushed off, but the fact they also choose to drag deacon into the insult ? dean may not fight for himself much, but he’d never allow others to think they could get away with believing that of his deputy.

muscle memory takes over for most of the fight, dean lost in a haze of anger as he barely registers fists connecting to jaws, elbows coming down on arms just to hear the bone shatter against the hunter’s weight. a boot comes down against the leg he had spotted from earlier, hearing a cry of pain. he doesn’t come out completely unscathed, a given considering the odds. bruises were gonna appear along his torso where ribs were cracked, skin split along his cheekbone after a knee finds its home there. his mouth is filled with blood, knuckles raw from every hit landed. but one by one the three stooges fall, sirens wailing in the distance.

red lights flash against the side of the bar and dean knows everything was drawing to an end. the anger hadn’t subsided yet, even as blood drips down against his eye from a cut on his brow, that thick bitter liquid sliding into his mouth from where his lip had split open. if anything, the fact that the paramedics were here makes him even angrier. news of this fight was going to get around town, not to mention it’d be documented by the meager police force that tried to maintain a sense of normalcy ; and if they filed a report, that meant it was going to fall into a particular deputy’s hands. and that ? made dean burn with a self-flagellating rage. already the soft sigh of defeat could be heard, that weary look that rested heavily on the deputy’s face was playing through dean’s mind. he couldn’t help the display of emotion as hunter yelled into the night, frustrated at the turn of events. one of the bodies on the floor before dean twitched in fear, gaining dean’s focus. fingers grasp their oily hair as dean throws all his irritation into one last movement. there’s a resounding crack as the man’s face hits the side of the bar, nose breaking against the impact as the noise drowns out dean’s heavy breathing. teeth clench as dean wishes he gave the other’s more of a chance to get a few more hits in. the pain would have been welcomed compared to the crushing dismay that began to settle along his shoulders. dean falls to the ground, the concrete jarring his backside as dean looses the strength to continue standing under this new weight. was deacon one of those who had shown up ? was he able to see the destruction that dean was responsible for ? was he watching still, or had he finally decided to walk away ?

did it even matter at this point ?

he can hear mary may in the background, but doesn’t look up from the hands holding up his face. it’s not until he feels her hand on his shoulder that he pays attention. “ got your hat kid. c’mon, i got a room in the bar for ya. ”

the effort is appreciated, but there’s still the feeling of being lost. displaced. dean had been so sure about what he had, but one slip of someone’s tongue had that certainty falling through his grasp. accepting the help to stand up, he moves along back towards the bar.

“ wasn’t pretty, but we all had your back. they deserved everything you gave them for talking shit like that. ”

dean stayed silent for the most part. mary may’s approval was nice, but it wasn’t what he was looking for. before he passes out in the bed being loaned out to him, he waits until he hears her leave, closing the door and walking back down to the main floor of the bar.

“ guess i’ll be getting what i deserve too. ”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another weekly chess puzzles! The first one was this:

[Image description: A chess board. It has 8 white pawns on a2, b2, d2, d4, e3, f6, g5 and h6. Five black Pawns on a4, a7, e5, f2 and h5. Two white knights on g4 and g7. One black Knight on b7. The white Bishop pair on b4 and h7. The black Bishop pair on b6 and c6. Two white rooks on d6 and h4. A black rook on a8. A White Queen on b3. A black queen on e7. The white King on a1. The black king on f8. End description]

Note: This position is completely impossible to get in a normal game (!!!), Since white has all of their pieces, yet black has two pawns on the a-file. One of the a pawns had to get there by being on the b file and capturing one of White's pieces that's on the a file. Yet white has all the pieces meaning none of them got captured.

Another note: White pawns are going up the board, black pawns are going down the board.

It's a mate in three for white. I stumbled into a completely by accident. I'll put the solution under a read more.

The answer is fxe7+ Kxe7 Qxf+ Kxf7 Rf6#

So the the first thing I noticed is: if the black queen on e7 wasn't there, than Rd8 double check will be checkmate. The king will be under a double attack by the rook and the dark squared Bishop. There's no way to stop both of the checks so the king must move. The king can't escape the rook check, it's pawn on e7 and our pawn on e6 prevent it from escaping. So it's mate.

So I wanted that Queen gone. So as my first move I played fxe7+. Kxe7 is forced, our knight blocks e8, our h pawn blocks g7, black's pawn blocks f7, and the light squared Bishop blocks g8.

The next part of my plan was to somehow force it back to f8. My first idea was to move the g7 knight to f5. It will give a check, but the king will be able to go to e8, and we need two moves for checkmate. I searched for a way to immediately mate it on e8, but there was no use.

So I looked for a different check that will take away the e8 square. The idea of Qe6 flashed in my mind for a split second before I immediately rejected it. White will be able to take our Queen with its f7 pawn. We won't find a mate in one from there.

Inspired by this idea I considered Qxf7+. It's a forcing check, forcing the king to f7. I thought I really didn't want it there. But I was on the lichess board editor, so I gave it a try.

So I did Qxf7+ forcing Kxf7. And now I wanted to give a check so I moved the Rook to f6 with Rxf8#. and I didn't remotely see it was mate. But apparently it's mate. No piece can take the Rook but the king, so the King must move.

Our g5 pawn takes f6. Our h7 pawn takes g7. Our g7 knight takes e6 and e8. Our light squared Bishop takes away g6 and g8. Our dark squared Bishop takes e7 and f8. And our rook delivers the check.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Reiner and Bertolt as Chess Players

I originally joked that there were very important spoilers here, but the reality is not really xD. Under the cut because it does discuss the most recent episode and it’s long.

Bertolt pondering his next move in episode 26.

I was watching a cool gif of Reiner and Bert playing chess in the opening episode of season two, when I realized two things. First, that Bertolt appears to give up his rook and then pushes a pawn to attack Reiner’s bishop (which is defended and worth less than a rook) like it’s an “aha!” move, and secondly that they’re playing with the board backwards (the square furthest to the player’s right is supposed to be white: the queen always goes on her own color and the white bishop is always on the right side). But the board being backwards gave me an idea: what if--like the sun rising in the west and the map looking like our own world turned upside down--chess in Attack on Titan is played with a black square furthest to the player’s right??

(I’ll give you a minute to finish laughing at me because I know this is a tiny and weird detail to think about xD Ok . . . minute up!)

My careful research has revealed that no, chess is not played backwards in the Walled World. It’s just wrong in this scene-- and this mistake is very common in “movie chess”! In all other scenes involving chess where the squares on the board are clearly visible, the board is set up correctly by our world’s standards.

Eren and Reiner playing chess in a promotional picture. The quality is a little low for me to tell exactly what is happening, but the board is correct.

Chapter 34. The furthest square to Bert’s left is black, so the board is correct in this version of the scene.

Chapter 35. It’s right in this panel too.

So it’s just an animation glitch, alas lol.

But then all this research got me thinking again: what kind of chess players are Bert and Reiner, really? Since Isayama actually gave us a viable position to look at, we can potentially analyze the strength and strategies of both teens as chess players. The anime’s position is a little wonky because of the backwards board, but I tried to recreate it as best I could, so I could compare the manga and the anime’s presentations of these two chess aficionados going at it.

I am only a mediocre chess player myself, but I did risk my pride to run my analysis of these positions by a person in my life who is a FIDE chess master. I will cop to thinking that both Reiner and Bert were a bit amateurish when I looked over these positions by myself, but my resident expert says that--in the manga at least--both of them are actually pretty good. They come off a bit more amateurish in the anime, but most of that, according to my expert, is because the board is set up incorrectly. Here’s a breakdown.

The Manga Game:

So, it was a little difficult for me to make out exactly what was happening on Bert’s side, but I’m pretty sure this is the position. A few things are immediately obvious: Reiner (white) has control of the center while Bert (black) has taken a more defensive approach. Who is winning depends entirely on who’s turn it is. If it is Reiner’s turn he can move his white bishop (the bishop who is on the white square) to check the king on the H-file (the one furthest to the left). I think the king’s only option then will be to move one square to the left, and then Reiner can move his queen to the open G-file and check the king again. Bert can block the check with his right-hand knight, but it’ll wreak havoc with his position, he’ll lose whatever piece he blocks the check with, and he’ll be even more on the defensive.

If it is Bertolt’s move, he can take either Reiner’s knight (which is positioned a little unhelpfully on the rightmost file) or his white bishop without repercussion. Doing so would widen the piece-gap between the two of them (Bertolt is currently up a bishop, meaning he has taken one of Reiner’s bishops without losing a bishop or knight of his own) and give him a foothold in the center.

My chess master consultant says that he thinks it’s probably white’s move and that white will win, while I was inclined to read it as black’s move, meaning that Reiner had hung pieces. According to my consultant, the fact that white has aggressively taken up so much of the center and that a several pieces have already been exchanged implies not only that it is white’s move, but that neither player is particularly amateurish. While black appears to be a bit more defensive, he had to do something to pop out and take one of white’s bishops. They’ve also opened up files and created room to maneuver. To quote my chess consultant, “This looks like a real position.”

So, based on this one game, Bertolt and Reiner are both pretty good and have opposing techniques (or at least have taken opposite approaches to this particular game): Bertolt is playing defensively and occasionally popping out to strike while Reiner is aggressively overtaking the center. One of them is about to gain a serious advantage depending on who is going next: this suggests to me that they are taking each other seriously and both playing to win. Possibly their unique tactics indicate that Reiner is a more outgoing and aggressive person than the introverted Bertolt.

The Anime Game:

So, I tired to mimic the incorrect board in the anime while drafting this position. Everything is flipped from what you see in the screenshot above to preserve this mistake. Hopefully I’ve gotten everything right! It was occasionally difficult to tell which pieces were which, but I think I’ve got it. Bert is white and Reiner is black in this version of their game.

In this game they’re both kind of in the center. Nothing is hanging. They’ve apparently swapped a few pieces: white is up a knight. The only move we see in the show is the one where Bertolt loses a rook:

Thanks to Fudayk for this gif!

The way Bertolt moves quickly makes it seem like he’s been planning this move for a while; what he appears to be doing (if you look at the diagram above) is putting extra pressure on Reiner’s bishop. Presumably he took Reiner’s rook before Reiner took his (since Reiner is also missing a rook), so they traded those pieces (which is contrary to my initial reading of the situation, before looking at their full position--I thought Bert had hung his rook and then randomly pushed a pawn xD oh me of little faith).

It’s a little harder to tell who’s winning here, even though we know it’s Reiner’s move. Reiner has more pawns, but is down a knight. Bertolt has pulled out a lot of pieces, as has Reiner, and they’re both competing for the center. Although he is down an important piece, Reiner’s queen has access to an open file and he could try to crack open the center with some of his pawns. Nobody’s planning anything as fancy as Reiner apparently is in the manga’s version of their game and the wall of pawns strikes me as a little weird, but my chess consultant friend says this could be a real position . . . if the board wasn’t backwards! xD

From a meta perspective, they both seem to be playing similarly: vying for the center, trading lots of pieces. Bert has a slight advantage, but neither of them appear to be playing terribly . . . besides the fact that their board is backwards.

So, I’m not sure this is the meta anyone asked for or even that anyone needed, but I got curious enough to spend the morning blowing up screen captures of this game so I could enter it into a diagram and I felt compelled to be so thorough as to take it to a chess master so . . . here you go lol!

#snk#snk meta#snk analysis#snk anime#season 2#snk anime spoilers#manga spoilers#reiner braun#bertolt hoover#chess#the things I will think about instead of properly working on my studies#oh well it's spring break lol

120 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland is a weird and wonderful story, full of odd surreal encounters and wacky nonsense. Despite it's strangeness though, I promise that drugs were not involved in it's production.

To read all of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass as a PDF: http://www.gasl.org/refbib/Carroll__Alice_1st.pdf

Full text version of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/11/11-h/11-h.htm

Full text version of Through the Looking Glass: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/12/12-h/12-h.htm

Closed Captioning coming soon

Transcript below

Alice in Wonderland isn’t about drugs.

Now, I know that may come as a surprise to some people. It’s pretty standard internet fair to point at Alice, with all the trippy visuals and the mushrooms and the Hookah caterpillar, and declare that it was REALLY all about drugs this whole time, oh ho ho, and Disney made a movie about it!

But it’s not. It’s not about drugs.

I want to talk about Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass a little bit today, what they are really about, where this idea of them being about drugs came from, and why I find it to kind of be bullshit.

So, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is an 1865 novel written by English novelist Charles Lutwidge Dodgson under the pseudonym Lewis Carrol. The sequel, Through the Looking Glass, was published in 1871. I’m going to focus mainly on these two original books, and not the dozens and dozens and dozens of adaptations and remakes that exist. For the record, both books are in the public domain, so it's very easy to find pdf copies of them on the internet.

Almost every movie version of Alice, including the Disney one, splices together elements and plot points from both of the books, rather than simply adapting one story or the other. It’s not particularly important to know which characters and events happen in each, since they are very often published as a pair anyway. But we’re going to have a quick overview.

-

In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Alice is a young girl who is in the garden of her home playing with her cat Dinah when she sees a white rabbit in a waistcoat run past, apparently late to an appointment. She follows the rabbit down the rabbit hole and thus into wonderland. What follows is a quintessential example of literary nonsense, filled with word play, puns, and absurdity as Alice works her way through Wonderland.

She eats an odd bite of cake and drinks a potion which change her size. She cries so hard she creates a sea. She recites some poetry she had to memorize for school buts gets it all wrong. She meets a mouse that won’t answer her call in English, so she tries talking to it in French. She wonders if this assumed French mouse came over with William the Conqueror, because Alice doesn’t know much about when things in history happened. They reach the shore where other animals are. The mouse then gives a lecture on william the conqueror and the animals agree to a Caucus race to dry off (Because Alice doesn’t know what a caucus actually is.)

Alice meets the Caterpillar, who seems to speak in riddles, correcting her grammar and not making sense. She meets the Duchess, who yells a lot and seems to ignore her baby. She meets the Cheshire Cat, who again, doesn’t make a lot of sense, and then the Mad Hatter and March Hare. More and more riddles. She plays a VERY silly game of croquet with the Queen of Hearts where the rules don’t make sense and the Queen cheats a lot. She meets a Mock Turtle (a pun on Mock Turtle soup, apparently Alice thought Mock Turtles were an animal). Then the world’s silliest court scene, where everything is unfair and doesn’t make sense, and then Alice goes back home, waking up as if from a dream.

Set presumably about half a year later, in Through the Looking Glass, Alice is playing inside the house with two cats, Dinah’s kittens, when she contemplates the mirror in the room. She finds that she is able to walk through the mirror and back into Wonderland. She discovers a mostly nonsense poem, Jabberwocky, which can only be read if you hold it up to a mirror. She also finds that the chess pieces in the room have come to life. What follows is another adventure in mostly absurdity, though if you know how, you can actually use Looking Glass as a step by step guide for a real chess game. Alice plays the part of one of the white pawns.

She wanders through the garden of living flowers, meets Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum, talks to Humpty Dumpty, and eventually makes all the way across the “board” and becomes a queen herself. The Red and White queens throw her a party, and then confuse her with riddles and wordplay. This actually results in Alice physically confronting the Red Queen and “Capturing her”, putting the Red King into “Checkmate” unintentionally, and thus, she wakes up in her arm chair back home having won the game.

Quick recommendation, if you want to get all of the little wordplay and puns and references in Alice and Looking Glass, I recommend the Annotated Alice by Martin Gardner. It’s awesome.

- These books are pretty strange. So, if not a psychedelic reflection about a weird acid trip, or whatever, what’s up with these books? Why are they so weird?

Well, Carrol said he wrote the book after he and a friend spent a day on a river trip with the 3 young daughters of Henry Liddell in 1862. During their journey, Carrol entertained the girls with a made up nonsense story about a girl named Alice. Alice Liddell was so entranced that she told Carrol he should publish it. And so he did. He spent a few years refining the story before it was finally published, and the real Alice got her copy.

So on the surface, it’s just that- a silly story meant to amuse children, a celebration of imagination and childhood silliness.

But there are some underlying themes in these books. The encounters Alice has have a sort of pattern to them- Adults in the books, whether they are the Queen of Hearts or the White Queen, the Duchess or the Hatter, often speak in riddles. They make up rules that don’t make sense and refuse to explain them. The white rabbit is obsessed with never being late, and much of the word play or silliness comes from Alice not understanding adult or unfamiliar concepts (like the Mock Turtle or a Caucus race.)

And so the books become a very silly exploration of how a child, viewing the adult world, might feel confused and lost. Wonderland is Adulthood cloaked in familiar childhood clothes. Nursery Rhymes and game board pieces doing a fumbling pantomime of adulthood, discussing mathematical concepts and latin grammar, through the eyes of a child who doesn’t understand it.

There are many things that can be pulled from Alice- ideas of innocence, of escapism, of identity and sense of self, of intentionally bucking order in favor of disorder. But none of those things are drugs.

(Sidenote: There is a whole other issue about Carrol’s….relationship with the Liddell daughters, and his...fondness for young girls in general. This is a whole separate debate, and it gets kinda messy with contemporary views of childhood and adulthood and whether there was anything...untoward about his fondness for them. But that’s really not what we’re talking about today. )

- So, why do people think this is a story about drugs? Carrol wasn’t known for opium use, or even heavy drinking. He had no exposure to psychedelics (magic mushrooms wouldn't be discovered by Europeans until 1955) So why?

I think the easiest answer is that people want stories to make sense. I want stories to make sense. I spent a lot of money going to college to get a degree in “Making stories make sense.” We want there to be a reason that things happen in stories, and so when a story feels as random and silly and surreal as Alice, we want to figure out what it’s REALLY about.

This is kind of the underlying idea behind surrealism in general- creating art and meaning out of the absurd and random images of dreams and unreality. [Side note, there is an edition of Alice with illustrations by Salvador Dali, which is...amazing.]

And thanks to the culture of the 1960s and 1970s, there is a heavy association between reality-bending images and drug use, especially hallucinogens. And depending on which adaptation you are looking at, some movies really play up this trippy psychedelic aesthetic for Alice.

But I think there’s another level to this one, and one that I find much more grating. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is a story for children, especially for girls. And there is a certain segment of the population, especially among young adults on the internet, who really seem to enjoy taking things aimed at children and declaring NO, this thing isn’t for kids, it’s actually FOR ME, and slapping an edgy dark interpretation on top of it, however sloppily.

Fan theories like...Ash is in a coma all along, or all the Rugrats are dead and Angelica is just imagining them, and...yeah, a huge slice of the Brony fandom declaring that adult men are the real audience, they aim at appropriating and co-opting child media for adult consumption

And there’s something about that which leaves a sour taste in my mouth over all. - I don’t think there’s anything inherently bad about reimagining child stories in more adult ways. But I do think it somewhat misses the point when people begin to insist that these mature reimaginings are the CORRECT or more valid interpretation, especially if they lead to the exclusion of children from that media space.

With Alice in particular, I think the story gives adult readers a chance to empathize with children, not as dolls or objects of cuteness, but as people interacting with a confusing and strange world as they grow up. It is an opportunity to revisit childhood, with all it’s familiar characters and uncertainty and wonder, and rather than corrupt that story, I think it should be embraced.

I’m going to leave you with the end of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Alice’s adult sister, having heard her story, lays back, and herself begins to dream, of Wonderland and of her sister Alice. And This is what it says, “Lastly, she pictured to herself how this same little sister of hers would, in the after-time, be herself a grown woman; and how she would keep, through all her riper years, the simple and loving heart of her childhood: and how she would gather about her other little children, and make their eyes bright and eager with many a strange tale, perhaps even with the dream of Wonderland of long ago: and how she would feel with all their simple sorrows, and find a pleasure in all their simple joys, remembering her own child-life, and the happy summer days.”

And that is what Wonderland is about.

Thanks for watching this video! I’ll see yall down in the comments, so if you have any questions, feedback, or suggestions, head on over. If you enjoyed listening to this queer millennial feminist with a BA in English ramble on for a while, feel free to subscribe.

431 notes

·

View notes

Text

Divorce Can Make Good People Bad

Why is it that people who seemed to be fairly rational before divorce turn into complete paranoid, hyper-defensive maniacs once the separation and divorce process begins? Couples who promised to do this divorce thing respectfully suddenly turn into ferocious warriors, letting their mean-and-petty streak show through, especially when they get into the pit with their attorney.

Sure, some people are just jerks, but what makes otherwise good people behave so poorly? It turns out this “crazy” behavior is fairly predictable and normal in such circumstances. That’s not an excuse for it, but when you better understand what’s pushing your buttons so badly, you can finally begin to make healthier choices and address the feelings of overwhelm that are triggering such unseemly (read: king of the jerks) behavior.

Here are the panic-button pushing reasons that divorce makes us act so out of character:

Disappointment Over Unmet Expectations

When you said “I do” you did so with expectations about what marriage is all about. But maybe you never fully shared those expectations with the person you actually said your vows to. Many times we don’t articulate our expectations specifically because we assume everyone just knows this is how marriage is supposed to be. But, “everyone” may only be your family and the way they did things, or your closest friends with whom you have discussed this over and over. It never included your now soon-to-be-ex-spouse who (don’t forget) came into marriage with some unspoken expectations of their own. When our deeply held expectations (like “marriage is forever, no matter what”) are unmet, we often feel betrayed, making it easy to feel indignant and cast our ex as the enemy. We believe they let us down. But, if we’re honest, were they ever fully on page with us to begin with?

The big challenge of marriage is putting both partner’s expectations on the table and then working together to create a mutually agreed upon vision for how your marriage will actually work.

youtube

Fear of Change

During periods of immense and drastic change (such as divorce), your mild-mannered brain goes into survival mode, ready at a moment’s notice to fight or retreat, thanks to that reptilian brain you inherited from your ancient ancestors.

Whether is it your fear of losing status (social, financial, etc.), a sense of uncertainty about the future, a worry that you don’t belong anymore in your social circle, or just a feeling like this whole situation is so unfair—the problem-solving part of your brain can’t do its job until your panicked reptilian brain calms down.

Uncertainty and fear about how things will turn out take a steep toll on you mentally and physically. Stress from staying in an “I’m in danger” primal mindset can short-circuit your patience, your willingness to listen, and your ability to communicate effectively. Your health is also likely to take a dive as well, making you prone to sleep deprivation and low stamina at a time when you are taking on mountains of critically important paperwork, decisions, and details as part of the divorce. So, even if you want to make good choices, the stress response of facing so much uncertainty and change at once is sure to cause you at least some temporary loss of rational thought and behavior.

youtube

Feeling Powerless and Out of Control

In normal life, you are used to being competent and in charge, but now you are thrust into the unfamiliar, unsure of how to get things done right in the divorce process (and in the new life waiting after it). You are being forced to make important decisions immediately. You have to hire a high-priced expert to navigate you through the legal aspects. And hiring a lawyer kicks off what could be seen by the other as an attack; you have drawn up sides and are now ready for war.

Communication is out the window when you feel powerless and unable to fully control things that profoundly affect your life. You have to trust your attorney (who was likely a complete stranger to you before this situation) to lead the charge and make decisions that will affect your future (and your childrens’ future) for years to come. It all costs a fortune. Is it any wonder each side feels like they are being screwed?

youtube

A Sense of Entitlement

Splitting apart all of the property (and associated memories) the two of you acquired through your sweat, equity, and hard-earned money can feel like a spiteful business transaction. Each of you has a sense of ownership and “it wouldn’t have happened without my efforts” point of view. Your decisions right now are dominated by your emotions, not your logical problem-solving self.

If you have kids, there is likely an overwhelming sense of guilt and worry that this divorce experience might be damaging them. They may even think it is their fault that mommy and daddy are splitting up. The kids end up as pawns in a fight over what you and your ex believe you each deserve or never deserved. Each of you are in it to “get yours” in the name of fairness. But the ego battle waging between you both in the pursuit of “emotional justice” ends up feeling more like scrambling down an endless tunnel with no cheese at the end.

So, what’s a stressed out person to do in order to keep divorce-induced jerky behavior in check?

Take back your dignity. Get in touch with who you are when you are at your best. Be clear about what is important to you and why, and how you want to remember yourself when this is over. Now, behave your way into that outcome.

Assemble a good team to support you in this transition from married to single. Identify where you need more information, different perspectives, and validation that will get you through this in a way that lifts you up (versus pulling you down). Pick people who can support you in being your best. Fight the urge to surround yourself with people who will urge you to seek revenge, act petty, or take your ex to the cleaners. When you look in the mirror, you want the best version of you reflecting back as you move into your new future.

Listen, listen, listen. Communicate, communicate, communicate—with your children, with your ex-spouse, and with the experts you are relying on to help you make the best decisions based on your needs, wants and values. Don’t be afraid to acknowledge your role in how things are going. If you misstep and act like a jerk for a moment, own it, and then apologize and move on.

Remember your past successes. Take care of what is important to you, ask for help, and remember the times when you successfully dealt with challenging times in the past. What allowed you to be resilient then? How can that help you here and now? You’ve been through hard times before—you can handle this.

Dealing with a difficult ex certainly doesn’t make the divorce process any easier. But neither does being a difficult ex. So keep yourself in check. By understanding some of the hot buttons that you both are pushing in each other, then maybe you can pause, take a breath, drop the jerk behavior and make better choices.

Free Consultation with Divorce Lawyer in Utah

If you have a question about divorce law or if you need to start or defend against a divorce case in Utah call Ascent Law at (801) 676-5506. We will fight for you.

Ascent Law LLC8833 S. Redwood Road, Suite CWest Jordan, Utah 84088 United StatesTelephone: (801) 676-5506

Ascent Law LLC

4.9 stars – based on 67 reviews

Recent Posts

Reasons Parents Lose Custody of Their Children

How to Pay off High Interest Credit Card Debt

Attestation Clause in a Will

Divorce vs. Legal Separation in Utah

Divorce Lawyer in Salt Lake City Utah

Michael R. Anderson, Utah Divorce Lawyer

Source: http://www.ascentlawfirm.com/divorce-can-make-good-people-bad/

0 notes

Text

Calculation: Part 2.5, Scattered Notes While at Work

So I’m at work right now, and there’s no one else here (since I’m usually the first in in the morning, and I have no student assistant today), so I think I’m going to take some time to really think about some thoughts I was having last night.

Interestingly enough, though many problems can be simplified - this just may be one where the complexity is preserved, despite the transformations I’m about to make...

I was doing some of the daily chess.com puzzles, trying to practice my calculating skill, and I think I’m getting better at it! The idea of analyzing all of the possible moves first, and then simply switching around the order, is very effective. I have noticed a few things however:

It is very important to calculate the squares for which pieces can move in subsequent turns. I know how a knight moves for the first two moves only, I’ll try to figure out 3 very soon. With bishops, queens, and rooks (long range pieces, as I will now call them), since each one can theoretically end up on any square within two moves (except for bishops, they can move to any square of their color after only two moves), it is more important to look at paths and open lines. Do not forget captures to end up at the arrival point!

Very important, also, to be able to move the location where capture happens. (For example, say a rook was aiming down the h-file at your king, then you play h6, and if a capture were to happen, then the g7 pawn can defend)

We need some sort of system where we can count threats and immediately be able to rule out certain moves

Whoever has the move is very important - hence moves that gain tempo should also have some factor in the calculation

Also another thing to consider is how the defense of each piece changes as the shape of the board changes. The threats may change based on how the pieces move, and our goal is to be able to predict these in advance without having to actually calculate

It is good to “see the shape of a piece,” (for lack of a better phrase), or to view each piece not only as itself, but all of its possible attacking squares, as well as future attacking squares. For example, when I look at a knight, I see the 8 squares that it can attack - but also, I try to see if my knight is in any one of the “forking positions” with another piece (2x4, 2 apart, 4 apart, 4x4, 3x5, etc), because this means I can capture in 2 moves. For bishops, I look at all of the squares of that color, and for rooks or something of the like, I look at the cross it’s on, but then at open paths that aren’t blocked (or where silly captures don’t happen)

Undefended pieces

Whether pieces can capture back or not

The entire idea with this approach is to try to plan out the next 6-7 moves until a decisive moment is reached, but not by trying move sequences. The idea is to immediately identify all of the possible moves, all of the future moves, and then string together a few in a sequence that makes a lot of sense.

Let us briefly make a list of factors that we should consider and add up, and then try to establish a very primitive model that we will develop into something more substantial later.

Threats that gain tempo (checks)

Threats in general (including ones that attack 2 or more pieces)

Value of the pieces being traded

The squares which the pieces are traded on

The blocking/opening of lines

Moves that add threats or remove threats (or both)

I will append to this list later as I see fit.

An interesting thought just occurred to me - what if, to save time, as the game goes on (even whilst my opponent is calculating), to think of all of the pieces that we can capture in the next move or two “Marvel vs Capcom style,” (same with our pieces). Say, for instance, we’re playing the London system, and we are preparing the e4 pawn advance, and we have a knight on d2, a bishop on d3, and a rook on e1. Then, as e3-e4, I can think of that pawn as a pawn-bishop-knight-rook. Because whatever he decides to capture e4 with, I can immediately turn that pawn into one of those pieces. Interestingly enough, we can think of empty squares as that too...perhaps this will be helpful in calculating. Say I have a pawn on e7, and a rook on e1 - then I can think of the pawn as a pawn-rook, where if the pawn is captured, it can become a rook, and perhaps hit the king on h7. Or if we have a pawn-rook-queen on e7, perhaps we can turn the pawn into a rook-queen and checkmate someone...?

Interestingly enough, continuing off of this idea, if we have multiple pieces attacking a square or one of their pieces, we could think of that square in terms of our own pieces on that square. Say they had a pawn on d6, and we had a queen, a rook, and a pawn all attacking d6, we could say that d6 has pawn/pawn-rook-queen. So we could create a pawn-rook-queen on d6 as the next move. (Naturally, we would start to observe what queens can do on d6).

Perhaps that idea will come in later.

A Very Primitive Model

It helps, when attempting to create something, or a method of any sort, to first see how we would deal with simple problems, before progressing on to more complex ones, and I shall attempt to do that here.

Let us begin with the simplest (and highly unrealistic) of all cases, which is two bishops (say the light squares) attacking each other, both pieces undefended. By starting with such a simple case, perhaps this will allow us to develop a system that lets us calculate more quickly.

The answer is obvious - whoever has the move ends up ahead.

This sheds light on another important factor - can the pieces capture back? Let us now take the exact same scenario, where the pieces cannot capture back. In this case, interestingly enough, one of two things will happen:

Both players capture

Both players evade capture

We quickly see that whether the second player can capture on the next turn is a very big deal, and also that whoever has the move is a very big deal. This is why checks are a big deal (and probably why they were invented in the first place) - the check provides us with an opportunity to “steal the move,” or “gain tempo,” as most chessplayers call it.

The next step is to add the defenders to the equation. Assuming both players have their bishops defended (say with rooks), then what will now happen is the “trade;” once player will capture the other player’s bishop, and the other player will capture back with the rook. Of course, the trade can be declined, as the first player can play a move that puts them out of the line of fire of the other bishop.

What’s interesting though, is that if the rooks will be attacking each other after recapturing. An easy scenario of this is to image white’s bishop on c3, white rook b3, black bishop f6, and black rook c6, with white to move. (Note: If we examine the bishops as “bishop rooks,” (to be elaborated upon later on), we quickly see that the trade is neutral for white if white is to move, but favors black). If white chooses to capture the bishop, then black will reply by recapturing. Awesome. Take the same scenario, however, and imagine it was black’s turn - black takes the bishop, but cannot recapture with the rook on c3 because of the c6 rook - he will lose a bishop and rook for just a bishop. Not worth at all. So white’s only move is to flee with the rook after the bishop falls.

In that scenario, however, black is attacking the bishop twice, so I suppose that wouldn’t matter. Is it theoretically impossible to have the defending pieces intersect if they are not already attacking the other piece? I will have to look into this. It seems like no, however...

Here’s an interesting scenario: Pawn-bishop vs pawn-rook. Say white’s pawn is on d4, with the rook on d3; say Black’s pawn is on e5, with the bishop on g7. Ahhhh, yes, the bishop indirectly attacks d4, so that would be a second order threat. So technically (as we will see later), black is attacking the pawn with a “pawn-bishop,” and white’s pawn is a “pawn-rook.” This significantly favors black, because if black has the move, he can potentially earn an extra piece if white is dumb enough to recapture with the rook. If it is white’s move, they trade.

A brief interlude to summarize what we have learned thus far:

For trades where the pieces are attacking each other, whoever has the move wins the trade if they are undefended

For trades where the pieces are attacking each other but the player who does not have the move has his attacked piece defended, then it will be even (assuming the pieces are of same value), neglecting the effects of the board after those moves

For trades where the pieces are not attacking each other (they are attacking other pieces on the board), it will come out even so long as the number of threats are the same.

If one has more indirect threats than the opponent, then they will win a piece.

The next step, naturally, is everyone having a bunch of undefended pieces all attacking each other, with none of the attacks overlapping. A very simple example would be two rooks attacking each other, and then the light square bishops and the dark square bishops attacking each other.

Both players have 3 threats, but all of those threats are returnable as well.

It is not too difficult to see that whoever has the move will come out on top, because since none of the moves overlap, assuming capture-capture-capture, the player with the move will have captured 2 pieces, whereas the other player would have had the opportunity to only capture one. Perhaps it might be useful to either split pieces attacking each other into a separate category, or not count them at all? We shall reserve judgment for now. In this case, it makes sense to capture the rook first, removing the most valuable piece from play. Then, it’s black’s decision to decide which bishop they want to keep, and they will capture with that bishop.

Interestingly enough, if both players have 4 threats in this situation (say the other two rooks were attacking each other, in an area that does not intersect with the other rooks or any of the bishops), then the player with the move has the advantage, namely because he can choose which bishop to keep.

We’ve now dealt with trades where all of the pieces can capture each other, and the conclusion is as follows:

If the number of trades is odd, the player with the move at the beginning of the trade wins

If the number of trades is even, then the player with the move will not be up a piece, but can choose which piece to keep

Let’s add un-connected defenders to all of the squares. That way, we don’t have to worry about anything else.

If there’s only one of each, either a trade occurs, or a trade doesn’t occur, and we have to consider whether the defending piece is under fire as well. If there are two of each, it doesn’t matter which piece is taken, but the second player will always capture the more valuable piece. The first player would do wise to capture the more valuable piece, unless there’s some sort of move available that could add or negate a threat.

So I suppose the defenders of the pieces is somewhat irrelevant if they are not connected.

We shall now discuss two final topics before wrapping up this discussion - when the values of the pieces are different, and when there are simultaneously pieces attacking each other, and attacks where that is not the case.

One thing is for sure though: unless you have a very good reason, never capture a defended piece of lesser value.

Anyway...let’s look at a really simple example when the value of the pieces are different. Of course, if there is no consequence, we want to capture the piece with the highest value first, whilst simultaneously avoiding our highest value pieces being taken.

An interesting thought just occurred to me - what if instead of keeping count of the amount of threats, we keep track of the amount of different types of threats there are as well? (And the amount that they have?) Perhaps that might help us clarify the position.

Maybe that would help us in the next discussion...

Let’s say we had two double trades (undefended), and then two non-attacking trades. Then, the player with the move has the slight advantage, as they can decide which piece to trade off. Interestingly enough, the player with the move can actually take one of the non-double trades, allowing the second player to choose which of the double trades he wants to commit to. If the second player decides to save a piece, the first player will be up a piece, after the second capture, player 2 can only hope to gain 1 capture. So a capture is essentially forced. If player 1 takes on the first move, player 2 is essentially forced into taking, unless he has a tempo gaining move. Since both players only have 3 threats each...

Tomorrow I will try to come up with a system that correctly encapsulates this idea.

0 notes

Text

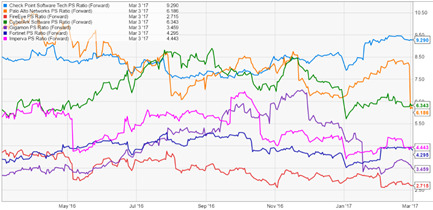

Recommendations to buy and sell Cyber Security Stocks

Summary:

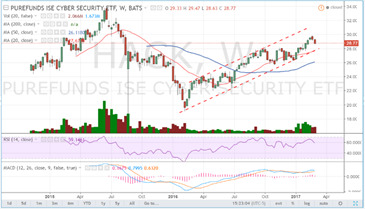

- Buy HACK ETF close to the support line of the uprising trend and have a tight stop loss. Don’t expect the gains to be as large as in 2016.

- I would wait for price consolidation in Fortinet (FTNT). So, I prefer to go long with a lower price or only in the breakout of the 37 level.

- I would day trade FireEye (FEYE) in the short side and Check Point Software (CHKP) in the long side. Too much risk to hold a position through the day.

- Gigamon Inc (GIMO): I would try a long swing position close to the 29-30 level with a very tight stop loss right below 28.

- Buying the dead cat bounce may be appealing, but at a lower price in Palo Alto Networks. Patience is needed.

- I might short Proofpoint (PFPT). I am waiting for the signal.

- Today: I opened a small short position in CYBR (trading the range, and probably make a follow up in my short after that) and I closed my short in FEYE (but I might day trade it again next days).

I want to focus my attention on one sector with one of the best stock performers (price) in 2016: Cyber security.

As heads up, I practice Fusion analysis (Fundamental and Technical) but my methodology usually starts with a top-down technical analysis view.

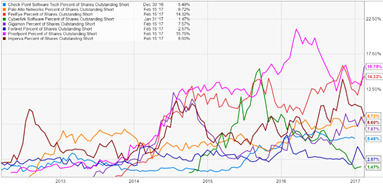

I think that cyber security is the next area in technology that needs real consolidation (industry and stock price). Meaning: more M&A activity and more price consolidation of many public stocks that have run nicely in 2016. Don’t get me wrong, I think this sector has a great future, but there might be a bumpy road ahead.

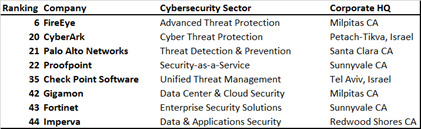

According Cybersecurity Ventures, worldwide spending on cybersecurity-related products and services is expected to top $1 trillion for the 2017 to 2021 time frame. Cybersecurity Ventures have also announced the Q1 2017 edition of the Cybersecurity 500, a global compilation of 500 leading companies who provide cybersecurity solutions and services. The next table shows only 8 of these companies -out of 500- and their ranking. These companies will be the focus of my analysis; the best part is that they are part of the top 44 of Cybersecurity Ventures’ ranking, have stock liquidity, a market cap over $1 billion, and interesting technical charts.

Source: http://cybersecurityventures.com/cybersecurity-500/

In regards to price consolidation, I follow the ISE Cyber Security Index which started at the 100 level in December 31 2010. As of February, 28 2017, its index total return has a price of 287.33, implying a CAGR of 18.67% (or annualized return). This is an index that provides a benchmark and is composed of companies that develop hardware and/or software that safeguard access to files, websites, and networks.

Source: https://www.ise.com/etf-ventures/index-data/ise-cyber-security-index-hxr/

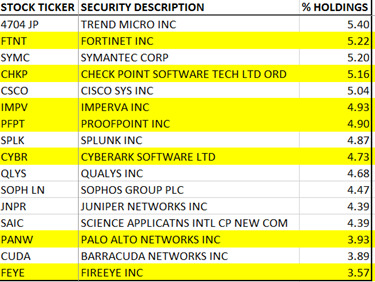

The ETF HACK has tracked this index since November 12, 2014 with an expense ratio of 0.75%, 34 holdings, a market cap of $7.4 billion and a quarterly re-balancing with “modified equal weight”. 7 out of the 34 holdings are the stocks that I am going to analyse. See the following chart with the highlighted stocks in yellow, with the exception of Gigamon, which is not included in the HACK ETF.

Source: http://www.purefunds.com/purefunds-etfs/hack/

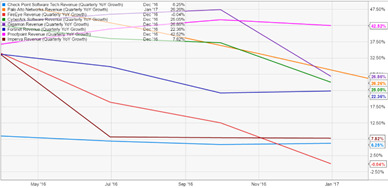

Since November 12, 2014, the return on the Index has been 8.28% annualized and the ETF HACK has been 7.14%. The difference of 1.14% can be attributed to both a 0.75% and a 0.39% of tracking difference. In the same period, if you had bought these stocks individually, instead of the ETF, you would have had the following annualized net returns (not including dividends): GIMO: +44%; PFPT: +28%; CYBR: +19%; PANW: +16%; FTNT: +15%; CHKP: +12%; IMPV: -4%; and, FEYE: -37%. As you can see, since the ETF was launched, this sector is still in consolidation and hasn’t gone above the last high that occurred in June 2015.

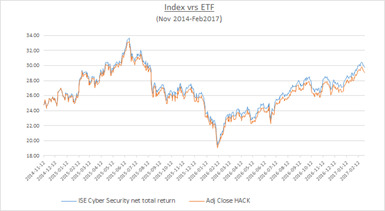

Created chart based on data from www.purefunds.com and Yahoo finance

The HACK ETF is still on an uptrend. You might want to consider going long once it goes to the support of the uptrend. For now, I have some long and short ideas for some of the stocks.

Let’s start the individual analysis in the same order as the last table (highlighted stocks in yellow), shall we?

1- Fortinet:

FTNT has a bullish structure trading above 20, 50, and 200 moving average (weekly chart). It jumped after reporting earnings in the beginning of February. Right now, it is trading close to the lower price after the gap which is dangerous for the bulls because MACD is giving a sell sign and RSI is showing weakness. Also, it is trading very close to a resistance level where it got rejected right after the gap up. However, it is difficult to call for a short in this bullish chart structure.

Depending on the markets in general and the ISE index, 36ish might be an area of consolidation (current price), but if the price continues lower, the mid 33s is a level to watch. However, if the price pushes higher next week to a price above 37 with high volume, the stock might reach close to 42. Earnings are going to be reported on April 25th.

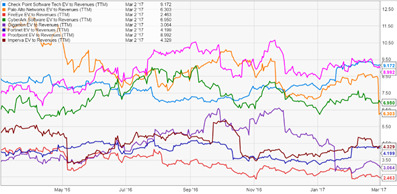

It is important to notice that the EV/revenues are at 4.2, above only Gigamon (3.06) and FireEye (2.46), and below the other 5, which make this a cheap stock. I would be a buyer in case of a breakout to the upside above 37 with a stop loss at 35.90 and a target of 42.

2- Check Point:

The fundamentals seem very good in CHKP, but technically speaking, it is trading in “profit taking” area if you were long. Congratulations! if you were long, but, this is not an area where I want to be buying. Please see the resistance in the monthly and weekly charts. In the daily chart, the MACD has given us a sell signal, but MACD in the monthly chart just gave us a buy signal. Let’s search for more evidence.