#pasolini planned a new film which was never made

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

PORCILE - (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1969)

I (re)watched yesterday this harsh, uncomfortable, apparently cryptic semi-unknown, if great, philosophic movie and, after the end, I confirmed and heightened the judgment I stated many years ago: "Porcile" is the most sincere (and consequently: the most outrageous) among all the movies (better: artworks) of the great Italian literate and filmmaker."Porcile" is a poor film: it was shot in a month with a ridiculous budget and has been considered by decades a Pasolini's minor movie despite, at a closer look, it appears as one of his richest to the extent that it is capable to dissect at its limits the apparent contradiction of a modern thought (his) that, indeed, cannot actually exist without continuously confronting with an "archaic heritage" that saves that sense of "sacred" (the infinite, the entirety, the inner human nature) that is crucial and essential to the soul of a poet/phylosophe.One initial stone inscription makes clear the theme: "After well questioned our conscience, we have stated to devour you because of your disobedience». that is: we (the public opinion); you( Pasolini himself).The movie is made of two separate (but intersected) narrations; the first story, set in France in the XVIII century, tells of a young man (Jean-Pierre Léaud) who, neglecting the love offering of his promised wife (Anne Wiazemsky), refuses any social behavior and has shameful sexual intercourses with pigs... ; the second story takes place in the Middle Age in a wild, desolate, vulcanic land (actually the Mount Etna) and tells of the chief of a bunch of murderous outlaws (Pierre Clémenti) who kills his father and eats his flesh. Both these transgressive "counter-heroes" will end their life eaten by animals....The meaning of "Porcile" all relies in trasnsgression; it is committed to demonstrate the statement that "the saints, like the different, anticonformist and disobedient people, don't make the history but suffer it" (PPP), they act by and for themselves and, by their diversity, they are doomed to die as victims of their anti-conformism, of their never be lined up with the masses.Pasolini's merit stands in his will to share with his readers and his audience this suffered message, the only irrepressible way that could allow him to bear the weight of the many crusades brought against him without retreating on the easy aristocratic position of "artist disengaged from the world" (and this is a reason for which we should never cease to be grateful to him).Pasolini says; "... the film bears also a political meaning; its esplicit object is Germany (its historical situation) but the target is the ambiguous relation between the new and the old capitalism; Germany has only been chosen as it represents a borderline case. The implicit poliitical content of the movie is a desperate distrust in all historical societies, consequently the genre of it (if there is one) is: apocalyptic anarchy. Being "the sense" of my movie so atrocious and terrible I only could treat it: a) by a quasi-contemplative detachment; b) with humor».The meaning is clear: after the horrors of the recent history (Hitler's Germany) we have the social desolations of the new capitalism. Julian's starvation (Léaud) is the result of this dramatic passage and his sad end (to be eaten by the pigs) blatantly tells of the impossibility of adapting to a reality in which "everything" becomes conformism (to be a revolutionary included, how the last sequence demonstrates).Similarly touching is the end of the "cannibal" Clémenti who, weaponed by his "apocalyptic anarchy" (and the resulting general contestation on an esistential plan), kicks, bites, beats whoever would submit him to a power that unavoidably would subjugate him. He enacts a man (or an idea), that is without pity just like those who would reduce him to a state of slavery (that he could never accept). His choice is so extreme that he prefers to move freely on the cold slopes of the Etna eating butterflies, snakes and human flesh, pushed from the instinctive pulse to live in contact with a sacred nature that has nothing of "moral".A unique movie, a deep reflection on the various ways to consider the human condition.

R.M.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ADVENT CALENDAR 2020✨FAVOURITE SCENES 8/24 Pasolini (2014): Epifanio & Ninetto meet P.S. Paolo police officers

“This is the most free city in the world. The city of lesbians and gays. And tonight is their big celebration. Do you want to come?”

#advent calendar 2020#favourite scenes#8/24#pasolini#ninetto & epifanio meet p.s. paolo police officers#abel ferrara#pier paolo pasolini#riccardo scamarcio#ninetto davoli#christian burruano#luka tartaglia#deep feelings#witty funny#queer cinema#lgbtq+#cinematography#pasolini planned a new film which was never made#epifanio#a story about 3 cities in one of which homosexual love is allowed#epifanio scenes are impressive in two ways#ferrara offers the first visual view of the story#the ways in which the citizens speak & behave challenge the modern viewer#it would be perfectly normal to ask such questions in public#own gif#own post

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Luca Guadagnino on Creating His HBO Series, Trump’s America, and Why He’s Remaking ‘Scarface’

by Brent Lang

Luca Guadagnino, the Oscar-nominated auteur behind “Call Me By Your Name,” is taking his swooning, lyrical style to the small-screen with “We Are Who We Are,” an immersive and deeply moving coming-of-age story.

The HBO-Sky series, which debuts this September, follow two teenagers, Fraser (Jack Dylan Grazer) and Caitlin (Jordan Kristine Seamón), who live on a military base in Italy. It explores their burgeoning friendship — Fraser is artistic, shy, and volatile, while Caitlin is more outgoing, but also dealing with her own nagging insecurities. The series, Guadagnino’s first for TV, also grapples with issues of sexuality and gender identity. He directed all eight episodes of “We Are Who We Are,” and says he purposely set the show in the midst of the 2016 U.S. presidential election as a way to comment on the political tumult unleashed by Donald Trump’s victory.

Guadagnino spoke to Variety shortly after the first trailer for “We Are Who We Are” was released.

How would you describe “We Are Who We Are”? Is it a TV series, a longer narrative feature, a miniseries?

I feel like on the one hand that this is a new film of mine. It feels like a movie to me, but I enjoyed the episodic-ness of the story. This is a series and it depends on how it clicks with an audience if we will see these people again. I have sort of a penchant for bringing back to life characters that I love. I truly love all the characters in this show. The greatness of doing TV is that if there’s a good outcome, this can come back, which would be beautiful to me.

What inspired the project?

Lorenzo Mieli [ed. note: who produced the show for The Apartment along with Mario Gianani for Wildside, both Fremantle companies] and Paolo Giordano and Francesca Manieri had developed a concept about the life of teenagers today vis-à-vis gender fluidity in American suburbia. When they talked to me about it, the first thing I said was I’m less interested in the topic as a sort of starting point. I’m more interested in the behavior of these people. I think in order not to be generic why don’t we set this in a micro-America, a place that can work as the part for the whole. I proposed the military world. I had a very wonderful conversation once many, many years ago with Amy Adams — you get to have these meetings with these great actors as one of the privileges of this work — and she told me that she spent part of her upbringing in Vicenza, in a military base in Italy. From synapses connecting to each other, I had this image in my mind.

Because this is a series, I said to Lorenzo, “If this goes well, next time they can move to another base. They can be in Japan or Africa or anywhere.”

In the show, the characters refer to the military base as ‘America’ despite the fact that it is in the middle of Italy. That geographic dichotomy seems to mirror the way that many of the characters feel a kind of emotional displacement or discomfort. Did you view the setting as a larger metaphor?

I always feel displaced. I never feel in the right place as a person. I do believe that despite every action we can take to claim the nature of our identity, eventually the human condition is that we are always trying to reclaim an emotional state of belonging. This show is about the kids not knowing who they are, not knowing what they are, and feeling displaced. Of course, there’s a transitional element of being a teenager that is specific to that age. It’s said that when you’re grown up, you know more about yourself, but truthfully all of these characters feel lost.

Fraser and Caitlin are both 14. That strikes me as an interesting age, because you’re definitely developing a stronger sense of identity, and yet you’re still wholly dependent on your parents. Why did you want to focus on characters at that particular age?

If I remember when I was 14, I was deeply, deeply unsatisfied by my incapacity to understand how to put in action the big plan I had for myself in my mind. I knew what I wanted, but I didn’t know how to get it. Eventually I even realized that I didn’t completely know what I wanted. I love this age, because you have grand ambitions and at the same time you have no means to fulfill those ambitions. You have only curiosity, only craving, only the capacity for experimentation. Every day seems to be a fight between life and death. That’s something beautiful about that age.

When the trailer for “We Are Who We Are” dropped, there were a lot of comparisons online to “Call Me By Your Name.” Both works are set in Italy and involve younger men. Do you see a commonality?

I will never complain about people’s laziness, but that sounds very lazy. “Call Me By Your Name” is about the past seen through the prism of a cinematic narrative and this is about the here and now. This is about the bodies and souls of now. I think they are so different.

Why did you decide to set the show during the 2016 presidential election?

The effects of the 2016 election are still being felt right here, right now. The seismic shift throughout America and the world of what it meant that Obama’s presidency was followed by Trump’s presidency and how people did not see it coming, are still being grappled with. It has to be said, that just as [Silvio] Berlusconi was the autobiography of Italy, Trump can also be seen as a sad chapter in the autobiography of the United States.

We are dealing with a kind of populism that springs from the plutocrats. It is shaping the world while at the same time a phalanx of youth is shaking the world as well and not taking that bitter medicine.

“We Are Who We Are” has a fair amount of full-frontal male nudity. That’s rare in American films and television shows. Why do you think that’s the case?

I always felt embarrassed when I saw in films the camera strategically not showing something. I also think that to show nudity — male, female — if it’s in the context of something that makes sense, is a way to liberate the eye. HBO has been wonderful in endorsing my choices. They could have felt provocative or radical, but I saw them as organic. By the way, there is nudity in general in my movies. That’s part of living. We are naked part of the day and part of the day we are dressed up. I always think I should pay respect to that condition of being human. Sometimes we’re naked, so why not?

You have about a half-dozen projects listed as in development on your IMDB. What’s behind that?

I am a relentless workaholic. I’m someone who has never tried any drugs, because I’m too scared for my own health. But I feel like when I was born, I fell on a “Scarface” mountain of cocaine, because I work 13 hours a day.

Are you working on a sequel to “Call Me By Your Name”?

I call it a second chapter, a new chapter, a part two or something like that. I love those characters. I love those actors. The legacy of the movie and its reception made me feel I should continue walking the path with everybody. I’ve come up with a story and hopefully we will be able to put it on the page soon.

You’re also attached to a remake of “Scarface.” What attracted you to that project?

People claim that I do only remakes [ed. note: Guadagnino previously remade “Suspiria” and his film “A Bigger Splash” was inspired by “La Piscine”] , but the truth of the matter is cinema has been remaking itself throughout its existence. It’s not because it’s a lazy way of not being able to find original stories. It’s alway about looking at what certain stories say about our times. The first “Scarface” from Howard Hawks was all about the prohibition era. Fifty years later, Oliver Stone and Brian De Palma make their version, which is so different from the Hawks film. Both can stand on the shelf as two wonderful pieces of sculpture. Hopefully ours, forty-plus years later, will be another worthy reflection on a character who is a paradigm for our own compulsions for excess and ambition. I think my version will be very timely.

What have you been watching during lockdown?

I watched again “Comizi d’amore” (Love Meetings) by Pasolini. I saw a great movie called “The Vast of Night,” and I watched for the second or third time “Doctor Sleep,” which is a movie I admire greatly.

#jack dylan grazer#fraser wilson#we are who we are#wawwa#luca guadagnino#chloe sevigny#alice braga#jordan kristine seamon#spence moore ii#kid cudi#faith alabi#francesca scorsese#ben taylor#corey knight#tom mercier#sebastiano pigazzi

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

David Furlong: "Now I have projects, not dreams"

Founder of the Exchange company, David Furlong is also an actor, director and translator. Many talents that have allowed him to find a place in the world of English theatre. (Alexis Gourret, 06.Jul.2021)

The theatre community is the one most affected by the pandemic. All companies have been forced to stop performing for a while and then adapt in order to survive. Exchange Theatre troupe is no exception. David Furlong, the creator of the company gave us an interview to review his career.

David Furlong is from Mauritius. Being from a former English colony, he spoke English as well as French all his life. A faculty that will become its greatest strength in the future. But before that, it was through France that he came to acting and studying theatre. “When I was 19, I played all year in a municipal classical company. But it wasn't very artistically interesting, not very deep and researched what I was doing. So I tried the auditions of national theatre schools in France. I had the one from Chaillot in Paris. But at that time I was very classic in my approach, a lot of Molière and Racine ". An approach that will evolve as he learns. “I was discovering a culture that is more global than French, more contemporary, more radical. Suddenly it was more art. " Despite a recognized training in the industry, David struggles to find work. “I realized that it will be more complicated for me because I am Mauritian. I realize that, at the time, it was more difficult for a man of color, even a pale one, to be an actor in France ". So in 2003 he decided to go to London, more open at the time to diversity, to move there in 2005. He landed his first work in a play by Rabindranath Tagore, an Indian symbolist, “it made a bit of noise. But that's also when we say to ourselves with Fanny Dulin, the co-founder of Exchange, "we can do it too".

Exchange, from English to French

They start from a very simple observation, in England, non-European texts are hardly known. “They don't know Pasolini here. They are unfamiliar with classics like Molière, whom they confuse with Italian comedy. When in fact, one is inspired by the other. England has a very strong culture. They have Shakespeare who is one of the greatest. So when you have such an author, why look elsewhere. I understand the bias that can create. And then England is an island, there they just voted on Brexit, there are things that are not totally surprising in this cultural identity that is a little withdrawn in itself." But it was precisely by taking advantage of this empty space that the Exchange was created, with the aim of translating French plays little known across the Channel and playing them. The first play translated and edited was Paul Claudel’s Exchange. This gave the company its name. “What is interesting about my career and the work of Exchange theatre is that we find ourselves gradually producing, then retouching a translation then doing one, then working on one with actors in a room, in short, we gradually added strings to our bow ”.

After their 4th show, Exchange was invited by the French Institute of the United Kingdom to work in residence for young bilingual children. “So we started to create shows for young audiences and we did 12 over 2 years. We wrote and produced all the time. It was a very, very good time. And at that time we also understood new things about bilingualism and working bilingually ”. So it was naturally at the end of these two years that they decided to create a show performed in both languages. “In 2013 we had all the original English audience, but we still have all this French-speaking following. So we decided we're going to do our next show in both languages. One play, two distributions, one in French and one in English and we alternated the evenings ”. A process which worked well, but which did not entirely satisfy David. The two shows were not the same since the French and English actors were different. A problem that the creator of Exchange will quickly solve.

The Covid hits hard

“In 2016 we made a Doctor in spite of himself on commission from the French high school (Lycée Francais). A single cast of completely bilingual people and we put on the same show one evening in English and the next day in French. It worked very well, but on top of that it brought us a lot of recognition, including a nomination for best staging at the Off West End awards. But in 2016, it is also the year of the Brexit vote and so at the same time we have the impression that the English were saying to us "welcome, do your job ”and at the same time the vote told us“ in fact we don't want you ”. Despite everything, the play is a hit and in large part thanks to the actors, who, being perfectly bilingual, can play with words and their modulation in one language and the other. "What's great is that when you want to put a more Latin intention in the French way, we can apply it, we bilingual actors, to English. And in the other direction too: if we want to put nuanced phrasing, the lightness of the English language in French, to better convey an intention, we can do that too. I don't have a preference between playing in French and in English, which is great is to nurture each other ".

In 2019-2020, the company and more particularly David Furlong, began to make a name for itself, a real place in the community, he worked at the Young Vic Theatre, various contracts were going to be signed, but unfortunately the covid arrived. “When everything stopped in March of last year, it was quite violent because we were on an upward slope in the company, we were more and more co-producer with other companies on bigger and bigger ones. shows. So these interruptions have been brutal, even in our personal careers. When it all stops it hurts". Past the frustration, the team had to find a way to continue to exist. And it was their decisions in the past that helped them survive. “Since 2007 we have opened theater classes for adults to support creation and also to create a community of theater enthusiasts. With the covid we continued our lessons on Zoom and our students followed us. We also started to broadcast some previous co-productions on the web. So our 2020 season has kind of taken place." The state also allowed them to survive. "We had an Arts Council grant in June 2020, Emergency funding, which allowed us to continue paying the rent for our rehearsal space. It saved us, because if we had lost this place, we wouldn't be talking to each other there, it would all be over."

IN Exchange was born

But to resist the ruthless theatre environment, you have to be visible and for that, Exchange has also found the solution. “A documentary team followed us on a creation two years ago. This documentary had never been released, He was there and ready, but we didn't know what to do with it, but all the same we said to ourselves that this might be an opportunity to show our work since can't exist on a set, at least people can find out on screen and say to themselves “that's great, it has to come back”. So it's called IN Exchange with all the symbolism that this title brings. It came out on June 15 and is a very beautiful document on the collective experience, on our vision of theater. Available on our site ”.

Besides this documentary another project is underway to continue to live as a company. “We have a show called Noor that already has commitment promises for the year 2021-22. We are thinking about our next creation and the Exchange also means that the collaborations with other companies and that will be really beneficial. We have a network of people who may be in the same difficulties as us, but if we do things together we will get there ”.

The Covid plus Brexit has taken its toll, but David Furlong refuses to give up and dream of coins. "You don't have to say it's a dream anymore if you're in it. Now I have plans, no more dreams ". A sort of mantra passed on to him by Jean Reno when they met while filming. So if you want to support his projects, don't hesitate to go take a look at his site and watch the documentary on the creation of the misanthrope "it's another dream / project that I realized.", Affirms David Furlong, actor, translator and director.

0 notes

Text

5 Up-And-Coming Photographers at Arles Festival

This article is published in collaboration with Kickstarter. Kickstarter helps artists, musicians, filmmakers, designers, and other creators find the resources and support they need to make their ideas a reality.

Chloé Wasp, Yucatán, 2019. © Chloé Wasp. Courtesy of the artist.

Les Rencontres d’Arles has attracted some of the world’s most esteemed and pioneering photographers over its 50-year history. And thanks to its longstanding relationship with the École Nationale Supérieure de la Photographie (ENSP)—France’s sole national art school dedicated exclusively to photography—Les Rencontres continues to incorporate fresh perspectives from young image-makers. This year’s festival opened this week, and will run through September 22nd.

“Since the beginning of the festival, the idea of education, especially through masterclasses, was very important,” said the festival’s director, Sam Stourdzé. Photographer Lucien Clergue, writer Michel Tournier, and historian Jean-Maurice Rouquette hosted the first Les Rencontres d’Arles in 1970. Just over a decade later, Clergue and then–Les Rencontres president Maryse Cordesse were granted a large house in Arles, which they transformed into a school with the first director, Alain Desvergnes.

Since then, the ENSP has shaped the work of photographers like Olivier Metzger, Mathieu Pernot, and Valérie Jouve, and the festival has grown into a three-month extravaganza that has exhibited works by masters like Ansel Adams and Agnès Varda, while also tackling topics like dark tourism and racism in contemporary American culture.

The storied festival has made room for artists in all stages of their careers, and ENSP students in particular have had great access through annual collaborations. This year, student Adrien Vargoz is curating a show that places student work alongside that of Nan Goldin and Massimo Vitali; Nina Medioni is setting up a portrait studio for teens; and Prune Phi is amplifying pieces she showed last summer at the festival with her own guerilla postcard stand. Here, we highlight these artists and more in our roundup of five photographers to watch from this year’s Les Rencontres d’Arles.

Adrien Vargoz

Adrien Vargoz, Untitled from “Chasing the Sun,” 2017–ongoing. Courtesy of the artist.

Adrien Vargoz, Untitled from “Chasing the Sun,” 2017–ongoing. Courtesy of the artist.

At “WIP (Work in Progress),” an annual Arles exhibition mounted by the ENSP student association, Adrien Vargoz is exhibiting “Chasing the Sun” (2017–present)—a series about artist Martin Andersen’s initiative to build a heliostat mirror that reflects rays into his sun-starved town square in Rjukan, Norway. The work isn’t yet finished, which makes it a good fit for the show, and Vargoz ran a Kickstarter campaign to fund a return trip to continue documenting the community.

Adrien Vargoz, La Vallée, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Adrien Vargoz, Untitled, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Adrien Vargoz, Untitled from “Chasing the Sun,” 2017–ongoing. Courtesy of the artist.

“I want to continue in the same vein while incorporating movement in my photography,” Vargoz said. “The mirrors move slowly, following the course of the sun. I would like to make the connection with this elasticity of landscape, whether mechanical or organic.” He wants to test out a more participatory approach to documenting the newly sunlit space, so he sent 30 disposable cameras to locals.

Vargoz is also one of six student photographers curating a Les Rencontres exhibition in ENSP’s newest building. The show, called “Modernity of Passions,” juxtaposes student work alongside images by Nan Goldin, Ryan McGinley, Malick Sidibé, and Massimo Vitali, among other artists from the agnès b. collection.

Chloé Wasp

Chloé Wasp, Eduardo, Macario Gomez, 2019. © Chloé Wasp. Courtesy of the artist.

Chloé Wasp is one of the up-and-coming photographers included in “Modernity of Passions.” Her work is deeply inspired by music and poetry, and she cites 20th-century French dramatist Antonin Artaud as having a profound influence on her work.

Chloé Wasp, Yucatán , 2019. © Chloé Wasp. Courtesy of the artist.

Chloé Wasp, Victoria, Yucatán , 2017. © Chloé Wasp. Courtesy of the artist.

Supernatural and subtly spiritual elements are at play in Wasp’s photography, too. Her most recent work, JAGUARES (2017–present), constructs an experimental documentary about the predominance of jaguar imagery—from pre-Hispanic art to modern billboards—in southeastern Mexico, and the actual animal’s conspicuous absence from its traditional habitats as development and climate change drive endangerment. Her pieces investigate the tension between the simultaneous presence and absence of these “ghosts.”

Aude Carleton

Aude Carleton, Au Nord, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Aude Carleton, Le grand large, 2019 Courtesy of the artist.

Aude Carleton is participating in “Modernity of Passions”with Au Nord (2018), a photo that won a LensCulture Portrait Award for its depiction of a teenage girl wrestling with heartache. Carleton will present it with a song called Nature Boy, a poetic meditation on a footballer’s slow death on the field, set to music by Oscar Emch.

Aude Carleton, Le Soleil, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

Aude Carleton, Le bain d’or, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

Aude Carleton, Soleil de minuit, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

Aude Carleton, Flowers Flames, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

Aude Carleton, Incendie, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

Imaginative world-making runs through Carleton’s work. Inspired by the cinematic style of film directors like Bruno Dumont and Pier Paolo Pasolini, she said that “taking pictures is like acting; it’s like staging reality.”

She’s currently developing a series called “Soleil Torride” (2019–present), which explores her roots in the West Indies. She said it stages “meeting a father [she] never knew, living under the path of another sun.”

Nina Medioni

Nina Medioni, Tsipora, from “Le Voile,” 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

Nina Medioni’s work centers around youth culture, and puts conversations before photographs. “I do photography because I love to meet people,” she said. “I spend a lot of time getting to know people before I ever take a picture.”

Nina Medioni, La Fenêtre, from “Le Voile,” 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

Nina Medioni, Lea, from “Le Voile,” 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

That’s how she started her years-in-the-making series “Le Voile (The Veil)” (2015–present). Visiting relatives in Bnei Brak—a very conservative community near Tel Aviv—Medioni got to know her cousin’s 11 children, and decided she wanted to create a portrait of their atypical experience of adolescence, with no phones or internet and limited access to books or images. “They have this ability to be very focused on someone, very curious about someone,” she said. “They’re very independent. And I want to show the choices they have to make so early—at 17, you have to decide if you’ll go into the army, and how religious you’ll be.”

To continue these explorations of adolescence closer to home, Medioni is setting up a portrait studio at a public high school to photograph local teens every Sunday through the duration of Les Rencontres. It’s a mix of personal research and community education—“a place of encounter,” as she described it, “to see how they interact with the camera, take their portraits, show them how the camera works, and discuss with them what a portrait is and can be.” She’s also taken photos of teenagers in nearby Marseilles, and will share those in “Modernity of Passions.”

Prune Phi

Prune Phi, Untitled, from “Missed Call,” 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

Prune Phi, Untitled, from “Missed Call,” 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

In 2017, Prune Phi discovered that her French-Vietnamese grandfather also had family in California—which is home to the largest Vietnamese community outside of Vietnam—and Texas. Her contact with them evolved into an extended visit and a show called “Long Distance Call” (2017). Further research into the Vietnamese immigrant community at home in France produced her next series, “Missed Call” (2018).

Prune Phi, installation of itinerary postcards and self-edited fanzines. Courtesy of the artist.

Prune Phi, Untitled, from “Missed Call,” 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

“I noticed how similar most of the shared stories were,” Phi said of her subjects. “They all brought up how peculiar their families were about sharing recipes and religion, and how silent they remained on personal experiences and expressing their feelings.”

“Long Distance Call” was featured in Les Rencontres last year, in a show called “Une Attention Particulière.” Phi’s viewing of French-Palestinian photographer Taysir Batniji’s “Gaza to America, Home Away from Home” (2017) at the festival helped inspire her work.

Now, Phi is preparing to travel to Vietnam to continue her explorations in a series called “Hang Up” (2019–present)—but first, she’ll spend time taking in Les Rencontres. She doesn’t have a formal exhibition planned, but she will display and sell postcards of her work with her peers Tal Yaron, Quentin Fagart, and Maxime Muller on the sidewalk. “It’s inspiring and exciting to see the calm town of Arles becoming so animated every time the festival opens,” she said.

from Artsy News

0 notes

Text

my first month in Berlin was really fucking lonely and pathetic. I had surely by then been tending to a few friendship-seedlings, a few of which ended up as fully realized friendships that I still do not know how I managed to cultivate. these people I would hang out with periodically throughout my first weeks, but I’ve always been one of those people who can’t understand why anyone would want to hang out with me, so when people actually did want to hang out with me I was clunky and awkward and navigated meeting their friends and then their friends-of-friends as if a there’d been whole trading-card set of Berlin scenesters laid out in front of me and someone was just chucking cards at my forehead frisbee-style. most of them I missed, they bounced off my forehead and spun off into the abyss of some Neukölln bar or weird fetish club and I never spoke to them again. there was a lot of that, just these one-off conversations of intense interest followed by a mutual agreement of continued contact followed by nothing. then I’d see them again months later at some event that drew the whole scene, from the bullseye (see: Peaches) on outward to the fringes, the acknowledgment would be nonexistent and if it happened it was weird, the next thing I knew they were a suggested friend on Facebook with fourteen mutual friends. was there anyone who didn’t know everyone else already? did some of these people charge you fifteen Euro for revealing that they recognize you in public?

some of these people, I took entirely too long to realize, had never been interested in being my friend at all. I was apparently stupid enough to forget, or to never know in the first place, that some people only talked to you if they wanted to sleep with you or if they thought you might have connections they could take advantage of. I had nothing to offer in either department. I spent the latter half of my teenage years putting so much effort into being unattractive, never making eye contact, and deflecting That Kind Of Attention that I hadn’t even considered the possibility that no one would know or care about any of that in a new environment. when people watched or smiled at me, I glared. when people asked me questions about my clothes or hair or what I was doing in the city, I gave monosyllabic answers in a flat voice. when people moved close to me, I got up and walked away. when they touched me, I hit them or otherwise raised cain before disappearing. that’s always easy to do when you’re tiny and wear dark clothes. being pursued as an object of sexual interest was not something I planned for because I didn’t pursue other people as objects of sexual interest. I considered myself outside of the dating and sex game and for whatever reason assumed everyone could figure that out immediately.

but they couldn’t, and that produced some awkward-ass situations. via social media I met a filmmaker, American by way of Israel, who made a documentary on William S. Burroughs that I had probably illegally downloaded and watched at least five times. we talked about Burroughs briefly, but ultimately he did not seem interested in talking about Burroughs. see, I was interested in talking about Burroughs. I wanted to know what interviewing Iggy Pop was like. I wanted to know what it was like to talk with John Waters for more than thirty seconds at a book-signing. by chance, we met two days later at a Drag Race viewing party in a bar I never set foot in anymore for different reasons. we recognized each other and he seemed genuinely interested in meeting me – we shook hands, he was drunk, I was probably running off of fruit and quark and an U-Bahn platform vending-machine diet coke. my handshake probably felt like a wet towel and I apologized for that, made some self-deprecating comment about how creepy my hands probably were. within five seconds the conversation was over. the next time I saw him, he was surrounded by an entourage at another club with no shirt on, perfectly sober. by then I knew better than to say hello, but he saw me and said nothing (which I can’t be salty about because I did the exact same thing). it wasn’t until then that I mentioned the earlier encounter to a friend, who said quite simply that he probably was just looking for sex and had lost interest.

I had not thought of this, obviously. what gave him the impression that I was interested in sex to begin with? I wanted to talk Burroughs, and interviewing Patti Smith. I was expressly not interested in what it was like to meet Peter Weller because when Weller brought up Pier Paolo Pasolini in one of his interview segments I think my hairline receded a little bit. at any rate, I was baffled. then I got angry even though I knew that sex would not have been a thing that ever would have happened anyway. what was the problem with me? my giant head and stick body? did my face look more or less cadaverous than in pictures and was that a deal-breaker? was I short, bad-postured, sickly, monotone, behaving strangely, shy, and not an established cosmopolite and freelance artist raising the rents in Kreuzkölln? yes to all of the above. this was one of a few lessons I had on the value of both sexual capital and artistic clout in the Berlin scenester circle. who were you fucking and what kind of art were you making? well, I wasn’t fucking anybody and I wasn’t making any art. luckily I was to make friends who also weren’t fucking anybody and ended up making art with them. they’re the reason I still go back.

(as a side note, this past April I met John Waters again at a book-signing – I was somewhat far back in the line and Waters had been pounding some brown liquor to get him through the evening. much to my and my friends’ delight, this meant that by the time we got to the table he was so in the mood to chat that the event organizers had to move him along. I brought up this filmmaker and said that I had met him and found him shallow and that the new feature film he had made was distasteful in a number of ways. Waters barely remembered the guy, and when I tried to jog his memory by saying that he’d directed a Burroughs documentary that largely featured Waters’s commentary, Waters responded: ‘oh, god, which one? there’s, like, five of those.’)

I also did some bold shit during my first month in Berlin, before I had people to necessarily call friends and before I realized that many of the people I was corresponding with existed on a plane very different from mine. my usual routine was to wear the same outfit and sit in the corner of a bar drinking a club mate until somebody talked to me, inevitably making a really fatuous comparison to David Bowie or, like, Gary Numan. or Kraftwerk. I moved from bar to bar that way, inciting some interest in people and then eventually leaving the bar and leaving them with no contact information because I wanted to go to bed and my throat was sore from secondhand smoke. this isn’t to say that I didn’t also take interest in people I saw, because I certainly did, but I guess I was prepared to make no attempts at talking to them and had resigned myself to the idea that any friends I would make would come to me. I apparently would have rather existed in complete isolation and misery for seven months than start conversations with strangers.

but sometimes I didn’t just sit in the corners of establishments hoping for friendships to strike up. sometimes I went to the parts of bars and clubs where I had no business being, as a trans person, as a person who looked feminine, as a person existing outside of the sexual market. I would take my drink and plop myself down in the middle of a fuckdungeon or a darkroom and just watch people. I was simultaneously interested in what drove cis gay men to seek out anonymous sex and horrified at the way the floor squelched under my shoes. I lit cigarettes and just held them so I looked more like I had my own purpose there, thinking that somehow let everyone else know that I was exempt from participating in the generally-expected activity but nevertheless allowed to be there. in my head I called this “taking up space” and sometimes accomplished just that. sometimes I sat, I fake-smoked, I drank a coke, I watched a man get spit-roasted in the corner like someone watches Animal Planet. then I would get up and walk out. other times I sat, I fake-smoked, I drank a coke, a fifty-year-old man would walk up to me mouth-breathing and rubbing his junk and I would get up and haul ass out. other times a young man would approach me and say loudly in English that this was a space for gay men to have sex and that I should go back upstairs to the main dance floor and bar instead of staring at everyone and “ruining the vibe,” and I would loudly tell him he was ruining his own vibe by bothering me instead of servicing the glory hole, and I would get up and get brow-beaten out.

my first month living in Berlin was, much like Isherwood’s descriptors of his early Berlin experiences – Bradshaw’s first Silvester celebration during which he walks in on Mr. Norris being flogged between two women while polishing one’s boots, or his brief glimpse of a shitfaced Baron von Pregnitz having a beer dumped down his throat while pinned on a couch by a “powerful youth in a boxer’s sweater” – the beginning of a series of dreamlike impressions that have been rewritten in my head numerous times. the places I frequent reorient themselves in my mind as soon as I leave Berlin again and I describe them slightly differently to people each time I retell a story. of course, there were times that were not necessarily dreamlike; buying rolls and water at an aldi is not that different in Berlin except that you really have to make sure the bottles are on their sides or they’ll topple over on the conveyor belt. in a way the aldi was a non-space all its own, though, as was the ausländerbehörde, the bürgeramt, the endless stretch of S-Bahn between Nikolassee and Grünewald that was so long and godforsaken that I was convinced all manner of time and molecular structure at its most fundamental had been suspended and no one was breathing. buying a Kinder bar for dinner from a spätkauf at 3AM alone at Görlitzer Bahnhof: did that actually happen? was I ever actually there?

1 note

·

View note

Photo

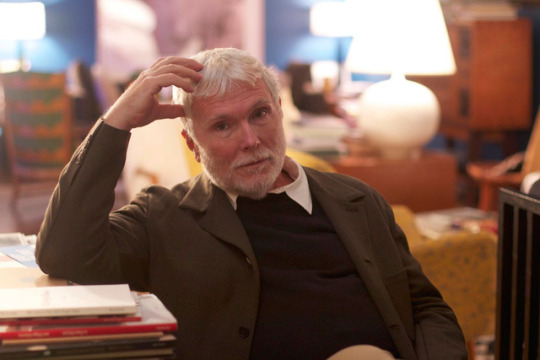

An Interview with Glenn O’Brien

Glenn O’Brien, the columnist, TV host and downtown social figure who originated “The Style Guy” in GQ, has passed away at 70. I interviewed O’Brien five years ago, when he released his book How To Be A Man. You can listen to our conversation here, or read it below. His irascible, relentlessly cool voice will be missed.

JESSE THORN: Tell me a little bit about why you wanted to write this book after you've been The Style Guy for ten or twelve years now.

GLENN O'BRIEN: I have a following, so I thought that I should do something that they would want. I didn't want to just answer questions, I thought this was a good excuse or cover for writing a book of essays. I'm now familiar with what men want to know because I get a set of questions every month. I just kind of took it from there.

JESSE THORN: I get these kinds of questions in my e-mail, too, from one of my other jobs as the writer of the blog Put This On. I find myself wondering whether we are living in an unusual time generationally, and I think you're just at the age to have had some perspective both on the huge generational shifts of the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s when you were a kid and the generational shifts in the post 90s era, as people ran out of things to be an alternative to. How do you see where these people stand that are writing to you?

GLENN O'BRIEN: I think a lot of people didn't have the complete parenting experience; I think my parents were not TV babies, I was from the first generation of TV babies, and we weren't just propped up in front of the tube, and it wasn't expected that that would raise us. I think that might have become the way kids are raised. There's less effort and less thoroughness in preparing boys to be men, and men to deal with the complexities of the world. I think people of my generation were given some sense of occasion, some sense of cultural diversity that I would say is endangered at this point.

JESSE THORN: You write a little bit in the book about the effect that your grandmother had on you gaining that sense of occasion.

GLENN O'BRIEN: She was a good coach. She laid down the rules as she understood them, which might not be the same rules that I observe, but I respect them and some of them I still follow.

JESSE THORN: What did you think of the rules when you were a teenager growing up in, if I'm not mistaken, Ohio?

GLENN O'BRIEN: I had mixed feelings on rules because I think I thought I was a rebel; I wanted to be a Beatnik. Certain roles I was fine with, like aesthetic rules, but social rules I felt like it was time for a change.

JESSE THORN: Did you grow up thinking of yourself as someone who was going to get out of Dodge as soon as he could?

GLENN O'BRIEN: Absolutely, I used to watch the What's My Line and I've Got A Secret that were these panel quiz shows, sort of like reality shows I guess. They would have interesting people on and their would be panels of these New York wits who hung out at El Morocco and the Stork Club and they would say very clever things, and I always thought that's what I want to do, I want to go to New York and be one of them.

JESSE THORN: I read somewhere, I can't remember where right now, but as a kid you actually got your parents to take you to the Stork Club and wait outside while you went in and socialized.

GLENN O'BRIEN: I realized I had very little chance if they tried to enter with me, so I said “Wait Here.” I went in and the Maitre d' was very charmed and he took me around to every table and introduced me, it was really great.

JESSE THORN: I like the idea that you thought you had a chance solo.

GLENN O'BRIEN: I was pretty cool; I was well dressed and I knew what was going on. I was a hipster, I knew who Walter Winchell was, so why not?

JESSE THORN: It's really wonderful. When did you first come to New York?

GLENN O'BRIEN: I think that happened when I was around 11. My stepfather was with the phone company and was always being transferred somewhere or other; luckily for me, we lived in New Jersey for two years, and that was a highlight because I was almost there. I got to go to Manhattan and see the jazz and go to art museums and see people that I never would have encountered in Ohio.

JESSE THORN: How do you think having a stepfather who was transferred around affected who you were as an adolescent?

GLENN O'BRIEN: I think anybody who's an army brat or corporate brat or whatever who moves around, you become more self reliant. You can't just hang with your posse for life, you've got to audition every time you make a move.

JESSE THORN: Tell me a little bit about the move that you made; when did you first come to the big city for keeps?

GLENN O'BRIEN: I knew that I wanted to end up in New York, but I wound up going to college in Washington, D.C. at Georgetown. I planned to move to New York as soon as I could, and so I wound up going to grad school at Columbia University School of the Arts in the film department. That was my first opportunity to be a New Yorker.

JESSE THORN: This was the 1970s if my math is right in my head.

GLENN O'BRIEN: I arrived in 1970. I immediately fell into this job working for Andy Warhol.

JESSE THORN: I want to talk about Warhol in a second, but first I want to ask you, where did you stand in relation to the counter culture as it was in the late 1960s as a guy who was as an 11 year old was able to converse with people about Walter Winchell?

GLENN O'BRIEN: I was up on my Beatnik literature and I was a jazz fan at a really early age; that was another adventure I had when I was little was I made my parents take me to - - they drove me to the Cleveland Jazz Festival. I was one of the few whites and probably the only one under 13 years old that was in attendance. I was into Cannonball Adderley and Jimmy Smith and all that stuff, so that kind of went in to the whole folky thing and Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones and all that. I was chomping at the bit of hipness.

JESSE THORN: Did you have a plan for yourself when you got to New York?

GLENN O'BRIEN: I wanted to make films. I was a huge fan of Godard and Melville and the French New Wave and Italian filmmakers like Fellini and Pasolini and also Andy Warhol. I wanted to make films and I got sidetracked.

JESSE THORN: When did you meet Andy Warhol and how did you meet him?

GLENN O'BRIEN: I was at Columbia with a classmate of mine from Georgetown named Bob Colacello who's become a well known writer since then; he's now a contributing editor at Vanity Fair. Bob and I were the stars of the criticism writing class at Columbia and our teacher, Andrew Sarris, was the main critic and film editor of The Village Voice. He would let his better students write for The Voice, as stringers. I wrote about things like El Topo and Pink Flamingos and Bob reviewed Andy Warhol's Flesh and gave it a glowing review and compared Andy to Michelangelo, and I guess Dallessandro to David or something like that.

They were looking for somebody who could run this magazine that they'd had for nine months and it had a different editor for every issue, so they were looking for stable and young clean cut college kids, and we fit the bill, and we knew about movies and it was a movie magazine and so they made Bob an offer and Bob said Okay, but I'm going to need help, can I hire my friend Glenn? I went and met Andy and I guess I passed muster and there we were in business, making a magazine that we had to learn by doing.

JESSE THORN: I think it's really interesting, the idea of being the responsible party of an irresponsible venture, if that makes any sense? To be the clean cut college kids that are brought in to be the straight arrows that nonetheless get it.

GLENN O'BRIEN: I think at that point there was a lot more -- I know a lot of kids now who are in their late 20s or early 30s and they're still trying to figure out what they want to be when they grow up, but we were driven. I think we grew up watching The Little Rascals; like, let's put on a show. Let's build a theater. I think there was just a feeling that anything was doable if you applied yourself to it.

JESSE THORN: I wonder if you could compare yourself as a very young man, especially in terms of style and comportment and identity to where you are now.

GLENN O'BRIEN: I'm wearing the same kind of clothes that I liked then now, I think. Fashions come and go, but I was really a modernist, I think. When the hippies came in I had hair down past my shoulders and a beard like Jesus, and I was wearing a tweed Brooks Brothers jacket, because it just seemed like that was what you wore if you were a modernist. I didn't want to dress like a goth or an American Indian, I just would have felt ridiculous. I think that that's a good life choice, to find something you like and stick with it.

JESSE THORN: It seems like the symbolism of that mode of dress that came about in the 1950s and 60s on college campuses and was about a simple, comfortable version of traditional tailored clothing changed a lot between the time when you probably started wearing those clothes and, say, the 1980s when the preppy revival happened, and now, 25 years after that. Tell me a little bit about how your relationship to that aesthetic changed.

GLENN O'BRIEN: I think in my life there've been two periods of what I would call aberration in men's fashion. The first was the polyester era, which followed close on the hippy era. There's a great example of it in that movie with Johnny Depp and Pee-wee Herman -- I think it's Blow. These spectacularly bad taste leisure suits that actually look kind of good on those guys, but you were thinking, where is this coming from? It lasted for a very short period.

Then in the late 80s early 90s, we went Italian and the power suit came in, the Wall Street power suit, which had enormous shoulders and very blousy trousers with multiple pleats and -- I don't know, I think it was when guys were really trying to show off and starting to wear watches that cost $50,000 and drive cars that looked like electric razors and things like that. Thank God that's over.

JESSE THORN: Those suits are kind of an odd mix of that assertion of power that's implied in, or explicit, in the power suit, those huge shoulders. And then this expression of, I don't really care about anything, I'm so relaxed, with the really droopy lapels and huge balloony pants.

GLENN O'BRIEN: It's funny because it actually coincided with the period when a lot of people started working out, so the shoulders looked even more ridiculous because you had shoulders on top of shoulders. You would see athletes like Michael Jordan wearing a suit like this, and it made their head look like a tomato or something.

JESSE THORN: I want to ask you about how you've seen the identity of masculinity change in this 30 years or so that you've been either in the business or connected to the business; from the late 70s through today.

GLENN O'BRIEN: I think we've evolved culturally in a lot of ways that I might not have expected to happen in my lifetime. I think that, thankfully, men today aren't so hung up on their sexuality and trying to prove that they're red blooded woman chasers. I think personality and cultural identity aren't so hung up on that stuff. Today you really can't tell who's gay and who's straight, and I think that's a good thing.

JESSE THORN: I thought it was really interesting that your Style Guy column was, when it was originally conceived, was going to be called something like Ask Your Gay Friend until you were picked to write it and everyone was like, well, we can't say that, Glenn's straight.

GLENN O'BRIEN: That was quite a few years before Queer Eye for the Straight Guy came on. It was a stereotype I think; straight men are clueless about interior décor, clothes, cooking, etc., and so they have to learn all this stuff. Things like that are, I think, encouraged by shows like Sex and the City where there's always conflict between the men and the women and the gay guy is like the sidekick of the posse of chicks. It's all kind of silly. Thankfully, we're going back to a more renaissance idea of manhood, where we're not just specialists who work on our computers and build bridges and do manly things, we do all the things that are important in culture. I think we're getting back to being generalists again, and that's a great thing.

JESSE THORN: You have a really funny and charming and eloquent description of the fop, and I would say defense of the dandy, in your book. Tell me a little bit about what you like about dandys, and also why you chose the word dandy to describe the thing that you like and discarded a variety of other adjectives.

GLENN O'BRIEN: I think it had to do with really finding out where the dandy came from. I think if you say the word dandy people think of someone who sends too much time thinking about how they look and is very fussy and extravagant and maybe is the kind of person that you would crane your neck after, like, wow, did you see that? But in fact the original dandy movement was a movement away from frills and flourishes and gold trim and extravagant colors. Beau Brummel who was the first so-called dandy was the man who invented modern trousers and who basically wore gray and black or tan instead of bright blue covered with gold trim. It's really the opposite of what I think people think of it as.

It was really kind of a political movement where the middle class was coming in to its own and you didn't have to be a landed noble anymore to be somebody, you could just get by on the strength of your personality and your taste.

JESSE THORN: Beau Brummel was noted for his advocacy of what we would now think of as a modernist aesthetic; something that's simple and clean and clear and to some extent uniform, especially compared to the gold brocade short pants, or whatever people were wearing before. That idea of the uniform was really, really strong in men's style, especially in the United States, through the 1960s when I think the counter culture kind of exploded it. I wonder how you feel about the idea of men's dressing as being an expression of the uniform.

GLENN O'BRIEN: I think in the civilian uniform there's a lot of latitude; there's plenty of room for self expression. I think in the 60s we kind of went in costume because things were so screwed up, and revolution was in the air. Everybody was thinking we have to be tribal, or we have to be more like savages and shamans. So there's this kind of explosion of consciousness that was fueled by psychedelics and people just began to live out their fantasy. Look at the bands of the time and they're dressed like Davy Crockett and Danielle Boon or Paul Revere and the Raiders, there was a tremendous fantasy. But basically when you settle down you realize that we still have to work and we still have to make things happen and raise the family.

The men's suit is a great modernist ideal in the same way that the Bauhaus building was; it's efficient, but it's beautiful in its symmetry and it relates nicely to the body. Nobody has come up really with a better idea. Blue jeans are another great idea, and now, certainly in the creative world, that's what guys wear. They wear a sport coat and jeans, that's another modernist costume that works, and it says something about our culture at the moment.

JESSE THORN: It seems like people who came after that generation that exploded the uniform are now coming of, and in fact the generation fully after, the folks whose parents exploded the uniform; I'm one of them, my dad was a veteran who came back and went to work in the anti-war movement, so needless to say he was not wearing a lot of Brooks Brothers sports coats. Although John Kerry probably was at the time. The people who came up with those folks as their fathers are now looking out at a landscape where they realize they can wear just about anything, but they don't have the tools to address that panoply of choices effectively. How do you see things moving forward with these folks that feel a little bit lost?

GLENN O'BRIEN: You have to educate yourself on any subject; you're not born knowing about art, music, cooking, how to speak, how to write. Everything is a matter of educating yourself, and I think you just have to start with “What do I like?” I think a lot of people have trouble with even that, which is one of the most basic decisions that we make hundreds of times every day, What Do I Like? It's Socratic. Know thyself. Figure it out.

The uniform, I think, comes out of the whole corporate thing. A lot of it is about blend in, keep your head down, and maybe you won't get fired. But I think now we're at a time when people are starting to lose their trust that their corporation is going to take care of them into their dotage, and the union is going to look out for them. I think now everybody realizes is you kind of have to look out for number one, and so I think that's why we're seeing a blooming of more individuality in the way men look, and that's a good thing.

JESSE THORN: It's nice to hear you say that, because when you speak with men's style experts, they often have one of two things. They have either a very well defined classicism; if you have, for example Alan Flusser, who you cite in the book and who I've interviewed before and is a great guy and an incredibly knowledgeable guy. Alan Flusser's aesthetic is defined around a classicism that is built around 1939. If you go to J Press you're going to get a classicism that's built around 1962 or 1960.

On the other side of it, you have people advocating a total fashion free-for-all that's determined by runways that change every year because people need to put new product on shelves. How does a man balance between those two things?

GLENN O'BRIEN: There's a lot of choices out there, and you kind of have to find out what it is that you put on that empowers you? What makes you feel better than anything else? For some guys it's going to be the barbarian suit that looks like its from a costume epic, and for other people it's going to be the slim Tom Brown narrow lapels sort of post-Mad Men look. It's just finding out what works for you. For me, it's -- Andy said it, the best look is a good plain look. In a way I like that, because if you look closer you can see, well, that's an interesting tie, or I like your Playboy bunny cufflinks, but you're not going to notice me from across the street, and that's who I am.

JESSE THORN: Glenn, I sure appreciate you taking the time to be on The Sound of Young America.

GLENN O'BRIEN: It was great, thank you.

JESSE THORN: Glenn O'Brien is the author of How to be a Man, a guide to style and behavior for the modern gentleman.

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

NYFF 2018: La Flor

I stopped playing sports of any kind at about age eight. I had asthma, I hated running, I didn't like being in extreme heat or rain for a goal I didn't understand, and most of all, I hated competition. Film always made more sense to me. You only had to watch what you wanted and there were a million ways to view any given work. Right around the end of high school something funny happened. I started making a list of all the films I thought I should see, the ones regarded as classics, or that kept cropping up in the magazines and books I was reading. The one constant were the films of almost inconceivable length. “Shoah,” “Heimat,” “Sátántangó,” “Berlin Alexanderplatz,” “Empire,” “Out 1,” and more exceeded five hours of viewing. What could possibly happen in such a runtime? Were these films simply elaborate dares? It seemed to me like they were competing with each other, and by extension with the viewers foolhardy enough to watch. Suddenly I found the kind of competition I liked.

In college I first dipped my toes in the absurd challenge of watching the longest movies ever when I found myself between a Kentucky Derby party happening in the house in which I lived, no car to drive anywhere, and the director's cut of "1900." I opted for the movie, the way I always do. The film nearly defeated me as it refused to end well past the point of having anything new to say about fascism or the direction of Italy's intellectual radicals. Struck me that Pasolini, his teacher and friend, was dead and Bertolucci wanted us to know what Italy, and the world lost, every time someone like the great poet died. And maybe if the film never ended Bertolucci never had to return to a reality without him.

“La Luna,” his next film was two and a half hours and begins with the death of a father, which bore out my hypothesis. There was something about the length that felt like a plea. I watched the 13-hour “Berlin Alexanderplatz” a few weeks later, split over two days, and loved it. The length made sense. The novel Rainer Werner Fassbinder was adapting was baroque and intricate, and he had to convey with completeness the mindset of a German before Nazism crawled into his and every other German's consciousness. There was also that it was nearly the last thing the enigmatic wreck directed before his death in 1982.

I've since watched too many films to count with epic lengths, several of them by Lav Diaz, and it's rare that they earn their length. Diaz's work is about wearing you down because he has chosen to make movies about the perpetually worn down. He gets us, or tries to, to see life as a pregnant Filipino woman would, screaming for better fortune and empathy from a cruel and empty world. When the six-hour “A Century of Birthing” ended I don't know that I felt anything except the peculiar sensation that if I went outside I might find myself in the Philippines. A herculean duration is not to be abused, because at its best, a long movie, or even just a very long shot, can teach us to form a relationship with an image. Chantal Akerman's three-hour “Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles” teaches us to question the purpose of a camera, its placement in a room, its function as a capturing mechanism, and what it can teach us about ourselves. Jeanne Dielman, like nearly every Akerman film, tells an audience what the life of its female protagonist feels like. The monotony, the repetition, the silence, it's still unlike any film about domestic femininity and objectification ever made, and part of that is its fearless patience.

I don't usually have cause to sit and think about the relative productivity of runtime but for a fellow named Mariano Llinás. I haven't seen his breakthrough, "Extraordinary Stories," which runs a cool four hours, so had never thought about him or his work, until suddenly they were all I could think about. His new movie “La Flor” was playing New York Film Festival, and it was 14 hours long. Calum Marsh said it might be his new favorite film. I was intrigued. The competition returned. I had to sit through it all in one go, there was nothing else for it. But what kind of long movie was this to be? Llinás himself appears in the beginning to explain: six parts, four without endings, one without a beginning and one with everything. Each would star the actresses Elisa Carricajo, Valeria Correa, Pilar Gamboa and Laura Paredes, and each would be in a different genre. Alright, pal, game on.

The first part of six was no help in divining the film's purpose or meaning. It's a (perhaps purposely) shoddy b-movie, a story about a mummy's vengeful spirit possessing an archeologist after she steals the old fossil's eyes. The film is (perhaps purposely) a collection of hysterical actions, from the long and busy conversations caught in minutes-long steadicam shots, the frequently howled dialogue, the preponderance of murderous cats and the red glowing eyes of the mummy. I thought it wouldn't have been such a bad VOD horror movie if it'd cut about thirty minutes off the hour and forty minute runtime. It felt self-indulgent for such a (perhaps purposely) slight genre movie. Part 2 muddied things even further. A couple going through a terrible break-up have to reunite to write and record a new album. Their early recordings, when they were together, were massive hits, and now their songs are loaded with bitter, barbed portent. A mutual friend of theirs hears both sides of their story, but she's not without ulterior motives. She's in deep with a strange scorpion-worshipping cult with nefarious designs on the songwriting duo. Just what they plan is never divined because the film ends right when everyone's about to confront each other.

Part three is many hours itself and concerns rival spies and their shared mission to kidnap a rocket scientist. It's a parody of spy movies but finds time for grace in its empathetic look into each member of the team's outlook on life and the violence that brought them together. This film ending before it's reached its conclusion is less a problem as it's quite plainly just about the puppet strings pulled by fate and the little left to us to contemplate. The fourth part is perhaps the most successful, following the crew of the movie we're watching as they try to create the segment we're watching. It goes haywire as Llinás get obsessed by filming Trumpet Trees and then he and his crew are in some kind of accident that drives them all mad. A paranormal investigator is dispatched to deal with the aftermath of their calamity. The fifth part is a silent remake of Jean Renoir's "A Day In the Country." The sixth part is shot like a series of tintypes, a telling of the struggle of four indigenous women. Then there are 40 minutes of end credits over an upside shot of the crew cleaning up after the last shot.

There are long movies and there are long movies. Llinás it seems, is just as competitive as I am because there is, quite frankly, no reason this film had to be 808 minutes long. He did it because he could, because how many 13-and-a-half-hour movies are there in a calendar year? Very few, and this film reminds us, there's good reason. He shows up in the middle of the third episode to tell us there are three and a half hours left in the chapter. To put it bluntly, he's fucking with us. When it was revealed in hour ... ten? Maybe? that I would be watching a pointlessly silent remake of one of the most perfect films ever made, I almost threw my shoe at the television. Part of the problem is that Llinás, in his hubris, imagined that he could dictate how the film would be consumed. He put in a dozen intermissions and requested it be broken up at such and such a place. That's all well and good but when a movie is done it's out of your hands. It's not a symphony that has to be conducted at a certain speed, it's a movie that will some day wind up on streaming services, likely watched in half-hour chunks like it's "Fuller House." I watched it all in one day and this movie is not designed to be watched in one day. If anyone involved in programming or making it had done what I did they would never have made this film this long because it has no rhythmic coherence. And if a film cannot be watched whole it cannot be watched at all.

The various extravagances of “La Flor” could be pardoned or loved in smaller doses, but recommending a day of one's life for an hour of reward seems like just as much a trolling as popping up to tell your audience how much longer they have before they then have five more hours left of a movie. Which is not to say I only enjoyed an hour of the movie, but I'd say in the context of each passage, there were sections that made each chapter worth watching (except perhaps in the unconscionably dull second part). "The Day In the Country" remake is basically numbing and pointless, especially since I'd been on a couch for an entire day before it began, except that near the end a section of audio from the original film appears on the soundtrack and Llinás starts filming single propeller planes in flight, dancing with each other in the sky like synchronized swimmers and I'm struck dumb. In that moment it's the most beautiful thing I've ever seen, I want to cry. Has the whole enterprise been worthwhile? A director with some idea of the shape of his opus would stop now but on we go to a superficially beautiful but deathly boring text-driven final act. Llinás does not know what he's done, does not know what the competitive cinephile will have done when he's heard there's a 14-hour movie calling to him from the annals of history ... or at the very least the wikipedia entry on the longest films ever made.

The thing that galls me still, weeks after I've seen it, when I've successfully reduced it in my memory to the best parts--the side-splitting Monty Python-esque digression about trees, the planes cutting across the grey sky--is that it's patently selfish to ask anybody to spend more than a day watching a movie. I was not transported, I was not let in on the secrets of its creator, I was not told about the mindset of the average anybody. I did learn a few important things: “La Flor,” I truly believe, cannot be called a film. It is six films and a middle finger of a credits sequence, stitched together like the "Bride of Re-Animator" for the purpose of making a raving fool out of me, the viewer who took his intentions at face value. Some of these movies are better than others, but none of them justifies the other, and no single element justified my spending 13 and a half hours watching this. I look back on those moments of transcendence, where Llinás gets out of his own way, stops taunting me, and lets the movie be a movie, and wonder if they'd have been as remarkable in a standalone 90-minute work.

I watched “La Flor” because “La Flor” dared me to watch it, and I have never shrunk from such a thing yet. This is what competition brings out in me and now I'm stuck with the secrets only a full day of movie can hold. A lifetime has passed since I scowled my way through soccer matches, praying to be taken off the field, and I haven't learned a thing. If nothing else, “La Flor” taught me that. A terrible price for a terrible truth, but the planes were lovely.

from All Content https://ift.tt/2Ab33yy

0 notes

Text

Nikos Deja Vu - Alexandros (Alekos) Panagoulis Documentary

Alexandros (Alekos) Panagoulis

Historical Documentary Greek Language

youtube

Alexandros Panagoulis (Greek: Αλέξανδρος Παναγούλης) (2 July 1939 – 1 May 1976) was a Greek politician and poet. He took an active role in the fight against the Regime of the Colonels (1967–1974) in Greece. He became famous for his attempt to assassinate dictator Georgios Papadopoulos on 13 August 1968, but also for the torture that he was subjected to during his detention. After the restoration of democracy he was elected to the Greek parliament as a member of the Center Union (E. K.). Alexandros Panagoulis was born in the Glyfada neighbourhood of Athens. He was the second son of Vassilios Panagoulis, an officer in the Greek Army, and his wife Athena, and the brother of Georgios Panagoulis, also a Greek Army officer and victim of the Colonels’ regime, and Efstathios, who became a politician. His father was from Divri (Lampeia) in Elis (Western Peloponnese) while his mother was from the Ionian island of Lefkada. Panagoulis spent part of his childhood during the Axis Occupation of Greece in the Second World War on this island. He studied at the National Technical University of Athens (Metsovion Polytechnic) in the Faculty of Electrical Engineering. From his teenage years, Alexandros Panagoulis was inspired by democratic values. He joined the youth organisation of the Center Union party (E.K.), known as O.N.E.K., under the leadership of Georgios Papandreou. The organisation later became known as Hellenic Democratic Youth (E.DI.N.). After the fall of the Colonels' regime and the restoration of parliamentary rule, Panagoulis became the Secretary-General of E.DI.N., on 3 September 1974. Alexandros Panagoulis participated actively in the fight against the Regime of the Colonels. He deserted from the Greek military because of his democratic convictions and founded the organization National Resistance. He went into self-exile in Cyprus in order to develop a plan of action. He returned to Greece where, with the help of his collaborators, he organized the 13 August 1968 assassination attempt against Papadopoulos, close to Varkiza. The attempt failed and Panagoulis was arrested. In an interview held after his liberation, Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci quoted Panagoulis as saying: I didn’t want to kill a man. I’m not capable of killing a man. I wanted to kill a tyrant. Panagoulis was put on trial by the Military Court on 3 November 1968, condemned to death with other members of National Resistance on 17 November 1968, and subsequently transported to the island of Aegina for the sentence to be carried out. As a result of political pressure from the international community, the junta refrained from executing him and instead incarcerated him at the Bogiati Military Prisons on 25 November 1968. Alexandros Panagoulis refused to cooperate with the junta, and was subjected to physical and psychological torture. He escaped from prison on 5 June 1969. He was soon re-arrested and sent temporarily to the camp of Goudi. He was eventually placed in solitary confinement at Bogiati, from which he unsuccessfully attempted to escape on several occasions. He reportedly refused amnesty offers from the junta. In August 1973, after four and a half years in jail, he benefited from a general amnesty that the military regime granted to all political prisoners during a failed attempt by Papadopoulos to liberalize his regime. Panagoulis went into self-exile in Florence, Italy, in order to continue the resistance. There he was hosted by Oriana Fallaci, his companion who was to become his biographer. After the restoration of democracy, Alexandros Panagoulis was elected as Member of Parliament for the Center Union - New Forces party in the November 1974 elections. He made a series of allegations against mainstream politicians who he said had openly or secretly collaborated with the junta. He eventually resigned from his party, after disputes with the leadership, but remained in the parliament as an independent deputy. He stood by his allegations, which he made openly against the then Minister of National Defence, Evangelos Averoff, and others. He reportedly received political pressure and threats against his life in order to persuade him to tone down his allegations. Panagoulis was killed on 1 May 1976 at the age of 36 in a car accident on Vouliagmenis Avenue in Athens. More precisely, a frantically speeding car with a Corinthian named Stefas behind the wheel diverted Panagoulis' car and forced it to crash. The crash killed Panagoulis almost instantaneously. This happened only two days before files of the junta's military police (the "E.A.T.-E.S.A. file") that he was in possession of were to be made public. The files, which never materialized, reportedly included evidence of his allegations of collaboration. There was much speculation in the Greek press that the car accident was staged to silence Panagoulis and to cover up the documents in question. Alexandros Panagoulis was brutally tortured during his incarceration by the junta. Many believe that he maintained his faculties thanks to his will, determination to defend his beliefs, as well as his keen sense of humour. While imprisoned at Bogiati, Panagoulis is said to have written his poetry on the walls of his cell or on small papers, often using his own blood as ink (as told in the poem 'The Paint'). Many of his poems have not survived. However, he managed to smuggle some to friends while in prison, or to recall and rewrite them later. While in prison his first collection in Italian titled Altri seguiranno: poesie e documenti dal carcere di Boyati (Others will Follow: Poetry and Documents of the Prison of Boyati) was published in Palermo in 1972 with an introduction of the Italian politician Ferruccio Parri and the Italian film director and intellectual Pier Paolo Pasolini. For this collection Panagoulis was awarded the Viareggio International Prize of Poetry (Premio Viareggio Internazionale) the following year. After his liberation he published his second collection in Milan under the title Vi scrivo da un carcere in Grecia (I write you from a prison in Greece) with an introduction by Pasolini. He had previously published several collections in Greek, including The Paint (Bogia).

Promise The teardrops which you will see flowing from our eyes you should never believe signs of despair. They are only promise promise for Fight. (Military Prisons of Bogiati, February 1972) (Vi scrivo da un carcere in Grecia, 1974) Nikos Deja Vu nikosdejavu.tumblr.com

0 notes