#paris 1829

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

(limited to Europe because there are limited slots per poll)

*The Long 19th century is the period between the French Revolution and the The First World War.

The French Revolution: The original, the classic. It's got Robespierre and Marat and a Guillotine.

The Serbian Revolution: Resisting Ottoman Rule? Forming a new state? Creating a Constitution? Serbia kicked it off in the Balkans nevermind that it took three tries and three decades.

The Greek Revolution: Have you become hopelessly invested in the idea of Greece as the cradle of civilization? Do you want to die fighting for it in a way that is tragic and romantic? Then you might be Lord Byron.

The Carbonari Uprisings: Secret societies are more your speed? Here is one in Italy doing their best to try to make liberal reform happen.

The Decembrist Revolt: So, a bunch of officers came back from Napoleonic Europe wanting to see constitutional change and possibly the abolition of serfdom. Sounds reasonable, right? Right??

The July Revolution: Can you hear the people sing? You know the one, barricades and the most iconic painting in French history. Louis Philippe ends up on the throne and he is....sexy to someone.

The November Uprising: Congress Poland decides that they are sick of the tsar. Poland undertakes a tragically doomed struggle against Russia.

The Belgian Revolution: The Belgians decide to file for divorce from The United Netherlands. Leopold of Saxe-Coburg ends up on the throne and he's sexy.

The 1848 Revolutions: The Springtime of the People! Revolutions everywhere: France, Hungary, Poland, Austria, The Italian and German States.

The January Uprising: The third time is the charm on kicking out the tsar and making a Polish state, right?

The Paris Commune: Napoleon III abdicates and leaves after being thumped by the Prussians. For two months, a communist people's regime rules Paris.

The Russian Revolution of 1905: This is not the one with Lenin yet! This is the one that forces Nicky to create a Duma. Some consider it the dress rehearsal for what would come next.

#napoleonic sexyman tournament#we need a new tag for extra polls#this is why people like the 19th century by the way#look at all those revolutions

257 notes

·

View notes

Photo

👩🌾 Revue horticole. Paris: Librairie agricole de la maison rustique, 1829-1974.

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frev friendships — Robespierre and Éléonore Duplay

Please present the testimonies of my tender friendship to Madame Duplay, to your young ladies, and to my little friend. Also, please do not forget to remind me of La Coste and Couthon. Robespierre in a letter to Maurice Duplay, October 16 1791

Present the testimonies of my tender and unalterable attachment to your ladies, whom I very much desire to embrace, as well as our little patriot. Robespierre to Maurice Duplay, November 17 1791. These letters are the only pieces conserved in which Robespierre mentions Éléonore.

[Robespierre’s] host's daughter passed for his wife and exercised a sort of empire over him. Causes secrètes de la révolution du 9 au 10 thermidor (1794) by Joachim Vilate, page 16.

When the constituent assembly was transferred to Paris after the October days, Robespierre came to stay in the house of Duplay, located on rue Saint-Honoré, opposite the convent of Assomption, and wasted no time in becoming a zealous devotee. The father, the mother, the sons, the daughters, the cousins, etc, swore only by Robespierre, who deigned to raise the eldest of the two [sic] daughters to the honors of his bed, without however marrying her other than with the left hand. At the time of the organization of the revolutionary tribunal, Robespierre had father Duplay appointed as juror; the two sons had a distinguished rank among Maximilien I’s bodyguards, whose leader was Brigadier General Boulanger. Mother Duplay became superior of the devotees of Robespierre; and her daughters, as well as her nieces and several of her neighbors, obtained high ranks in this respectable body. Souvenirs thermidoriens (1844) by Georges Duval, volume 1, page 247.

It has been rumored that [Éléonore] had been Robespierre's mistress. I think I can affirm she was his wife; according to the testimony of one of my colleagues, Saint-Just had been informed of this secret marriage, which he had attended. Mémoires d’un prêtre regicide (1829) by Simon-Edme Monnel, page 337-338.

Madame Lebreton, a sweet and sensitive young woman, said, blushing: “Everyone assures that Eugénie [sic] Duplay was Robespierre’s mistress.” “Ah! My God! Is it possible that that good and generous creature should have so degraded herself?” I was aghast. “Listen,” cried Henriette, “don’t judge on appearances. The unhappy Eugénie was not the mistress, but the wife of the monster, whom her pure soul decorated with every virtue; they were united by a secret marriage of which Saint-Just was the witness.” Souvernirs de 1793 et 1794 par madame Clément, Née Hémery (1832) by Albertine Clément-Hémery.

[Robespierre’s] relationship with Éléonore, the carpenter's eldest daughter, had a less protective and more tender character than with her other sisters. One day, Maximilien, in the presence of his hosts, took Éléonore's hand in his: it was, in accordance with the customs of his province, a sign of engagement. From that moment on he was seen more than ever as a member of the family. Une Maison de la Rue Saint-Honoré by Alphonse Ésquiros, published in Revue de Paris, number 9 (May 1 1844). At the end of this article, Esquiros claimed to have obtained the information contained in it from Éléonore’s sister Élisabeth. Shortly thereafter, said Élisabeth did however write a letter to the paper in order to ”protest loudly against the use that, without consulting me, you have made of my name, and to declare that this article, on many points in contradiction with my recollections, also contains a large number of inaccuracies.” She does unfortunately not indicate exactly which parts of the article are inaccurate and which ones are not, and certain details contained in it match up too well with what Élisabeth writes in her (by then not yet published) memoirs for me not to believe Esquiros hadn’t actually interviewed her prior to writing the article. In spite of her complaint, all the information in article was republished, almost entirely word for word, in volume 2 of Ésquiros’ Histoire des Montagnards (1847).

My eldest sister had been promised to Robespierre. Note written by Élisabeth Duplay, cited on page 150 of Le conventionnel Le Bas : d'après des documents inédits et les mémoires de sa veuve (1901) by Stéfane-Pol.

Duplay's eldest daughter, Éléonore, shared her father's patriotic sentiments. She was one of those serious and just minds, one of those firm and upright characters, one of those generous and devoted hearts, the model of which must be sought in the good times of the ancient republics. Maximilien could not fail to pay homage to such virtues; a mutual esteem brought their two hearts together; they loved each other without ever having said so to each other, there is no doubt that if he had succeeded in bringing order and calm to the State, and if his existence had ceased to be so agitated, he would have become his friend's son-in-law. The slander, which spared none of those loved by the victim of the Thermidorians, did not fail to attack the woman he wanted to make his wife, and one was not afraid to write that a guilty bond united them. We, who knew Éléonore Duplay for nearly fifty years, we who know to what extent she carried the feeling of duty, to what extent she rose above the weaknesses and fragility of her sex, we strongly protest against such an odious imputation. Our testimony deserves all confidence. France: Dictionnaire Encyclopédique (1840-1845) by Éléonore’s nephew Philippe Lebas jr, volume 6, page 821.

A virile soul, said Robespierre of his friend [Éléonore], she would know how to die as she knows how to love... The destitution of his fortune and the uncertainty of the next day prevented him from uniting with her before the destiny of France was clarified; but he only aspired, he said, to the moment when, the Revolution finished and strengthened, he could withdraw from the fray, marry the one he loved and go live in Artois, on one of the farms that he kept from his family's property, to there confuse his obscure well-being in common happiness. (Extract from a part of l’Histoire des Girondins looked over by Philippe Le Bas). Le conventionnel Le Bas: d'après des documents inédits et les mémoires de sa veuve (1901) by Stéfane-Pol, page 78.

All the historians assert that [Robespierre] carried out an intrigue with the daughter of Duplay, but as the family physician and constant guest of that house I am in a position to deny this on oath. They were devoted to each other, and their marriage was arranged; but nothing of the kind alleged ever sullied their love. Testimony from Robespierre’s doctor Joseph Souberbielle, cited in Recollections of a Parisian (docteur Poumiès de La Siboutie) under six sovereigns, two revolutions, and a republic (1789-1863) (1911) page 26.

[Robespierre] rarely went out in the evening. Two or three times a year he took Madame Duplay and her daughters to the theater. It was always to the Théâtre-Français and to classical performances. He only liked tragic declamations which reminded him of the tribune, of tyranny, of the people, of great crimes, of great virtues; theatrical even in his dreams and in his relaxations. Histoire des Girondins (1847) by Alphonse de Lamartine, volume 4, page 132. Lamartine claimed to have interviewed Élisabeth Le Bas Duplay and it therefore seems likely for this detail to come from her.

The eldest of the Duplay daughters, who Robespierre wanted to marry, was called Éléonore. Robespierre allowed himself to be cared for, but he was not in love. […] The Duplay family formed a kind of cult around Robespierre. It was claimed that this new Jupiter did not need to take the metamorphoses of the god of Olympus to become human with the eldest daughter of his host, called Éléonore. This is completely false. Like her entire family, this young girl was a fanatic of the god Robespierre, she was even more exalted because of her age. But Robespierre did not like women, he was absorbed in his political enlightenment; his abstract dreams, his metaphysical discourses, his guards, his personal security, all things incompatible with love, gave him no hold on this passion. He loved neither women nor money and cared no more about his private interests than if all the merchants had been free, obligatory suppliers to him, and the inn houses paid in advance for his use. And that’s what he acted like with his hosts. Notes historiques sur la Convention nationale, le Directoire, l’Empire et l’exil des votants (1895) by Marc Antoine Baudot, page 41 and 242.

Madame Duplay had three [sic] daughters: one married the conventionnel Le Bas; another married, I believe, an ex-constituent; the third, Éléonore, who preferred to be called Cornélie, and who was the eldest, was, according to what people pleased themselves to say, on the point of marrying my brother Maximilien when 9 Thermidor came. There are in regard to Éléonore Duplay two opinions: one, that that she was the mistress of Robespierre the elder; the other that she was his fiancée. I believe that these opinions are equally false; but what is certain is that Madame Duplay would have strongly desired to have my brother Maximilien for a son-in-law, and that she forget neither caresses nor seductions to make him marry her daughter. Éléonore too was very ambitious to call herself the Citizeness Robespierre, and she put into effect all that could touch Maximilien’s heart. But, overwhelmed with work and affairs as he was, entirely absorbed by his functions as a member of the Committee of Public Safety, could my older brother occupy himself with love and marriage? Was there a place in his heart for such futilities, when his heart was entirely filled with love for the patrie, when all his sentiments, all his thoughts were concentrated in a sole sentiment, in a sole thought, the happiness of the people; when, without cease fighting against the revolution’s enemies, without cease assailed by his personal enemies, his life was a perpetual combat? No, my older brother should not have, could not have amused himself to be a Celadon with Éléonore Duplay, and, I should add, such a role would not enter into his character. Besides, I can attest it, he told me twenty times that he felt nothing for Éléonore; her family’s obsessions, their importunities were more suited to make feel disgust for her than to make him love her. The Duplays could say what they wanted, but there is the exact truth. One can judge if he was disposed to unite himself to Madame Duplay’s eldest daughter by something I heard him say to Augustin: “You should marry Éléonore.” “My faith, no,” replied my younger brother. Mémoires de Charlotte Robespierre sur ses deux frères (1834) page 90-91.

A little wooden staircase led to [Robespierre’s] room on the first floor. Prior to ascending it we (Fréron and Barras) perceived in the yard the daughter of the carpenter Duplay, the owner of the house. This girl allowed no one to take her place in ministering to Robespierre's needs. As women of this class in those days freely espoused the political ideas then prevalent, and as in her case they were of a most pronounced nature, Danton had surnamed Cornelie Copeau "the Cornelia who is not the mother of the Gracchi." Cornelie seemed to be finishing spreading linen to dry in the yard; in her hand were a pair of striped cotton stockings, in fashion at the time, and which were certainly similar to those we daily saw encasing the legs of Robespierre on his visits to the Convention. […] Fréron and I told Cornelie Copeau that we had called to see Robespierre. She began by informing us that he was not in the house, then asked whether he was expecting our visit. Fréron, who was familiar with the premises, advanced towards the staircase, while Mother Duplay shook her head in a negative fashion at her daughter. Both generals, smilingly enjoying what was passing through the two women's minds, told us plainly by their looks that he was at home, and to the women that he was not. Cornelie Copeau, on seeing that Fréron, persisting in his purpose, had his foot on the third step, placed herself in front of him, exclaiming: ”Well, then, I will apprise him of your presence," and, tripping upstairs, she again called out, "It’s Fréron and his friend, whose name I do not know." Fréron thereupon said, "It’s Barras and Freron," as if announcing himself, entering the while Robespierre's room, the door of which had been opened by Cornelie Copeau, we following her closely. Memoirs of Barras: member of the Directorate (1899) page 167-169, regarding a meeting he and Fréron tried to have with Robespierre following their return from Marseilles in March 1794.

In the morning, the daughters of the carpenter with whom Robespierre lived dressed in white and gathered flowers in their hands to attend the feast [of the Supreme Being]. Éléonore herself composed the bouquet for the president of the Convention. Histoire des Montagnards (1847) by Alphonse Esquiros, volume 2, page 447-449. In a footnote inserted on page 28 of Thermidor, d’après les sources originalets er les documents authentiques (1891), Ernest Hamel writes that Esquiros obtained this description from Élisabeth herself.

…Éléonore, Victoire, Sophie, Élisabeth, raised in the peaceful interior of the home, in the oasis of the family, sincerely imagined that the same happiness extended to the whole city; they blessed in their hearts the God of the revolution who had given such rest to the French nation. Only one circumstance worried them, it was that for some time the porte-cochère of the house had been strictly closed night and day on orders from the carpenter. Éléonore timidly asked Maximilien the reason for it in front of her other sisters. He blushed. “Your father is right,” he said; ”Everyday right now something passes along this street that you must not see.” In fact, around two o'clock in the afternoon, a tumbril was rolling heavily on the pavement of Rue Saint-Honoré; the sound of horses and the cries of people could be heard even in the courtyard. It was the thing that passed by. Une Maison de la Rue Saint-Honoré by Alphonse Ésquiros, published in Revue de Paris, number 9 (May 1 1844). The incident is portayed as taking place during the time of the ”great terror” of June-July 1794. When republishing the anecdote in his Histoire des Montagnards (1847), Esquiros instead has Robespierre say this to Éléonore on January 21 1793, the day of the king’s execution.

It was the first days of Thermidor: Maximilien continued his evening walks at the Champ-Élysées with his adoptive family. The sun, at the end of the sky, buried its globe behind the clumps of trees, or swam softly here and there in a dark gold fluid. The sounds of the city died away in the agitated branches; everything was rest, silence and meditation: no more tribunes, no more people; nothing but the peaceful and solemn teaching of nature. Maximilien walked with the carpenter's eldest daughter at his arm: Brount followed them. What were they saying to each other? Only the breeze heard and forgot everything. Éléonore had a melancholy brow and downcast eyes: her hand carelessly stroked the head of Brount who seemed very proud of such beautiful caresses; Maximilien showed his fiancée how red the sunset was. Here ends the story of intimate life; here Mme L(ebas) movedly wiped her eyes. This walk was the last. The next day, Maximilien disappeared in a storm. Une Maison de la Rue Saint-Honoré by Alphonse Ésquiros, published in Revue de Paris, number 9 (May 1 1844). When republishing the anecdote in Histoire des Montagnards (1847), volume 2, page 460, Esquiros adds the following part right after reprinting the anecdote word by word: “It will be good weather tomorrow,” said [Éléonore]. Maximilien lowered his head as if struck by an image and a terrible presentiment.

Legendre: At the time of 9 Thermidor, I was secretary as well as Dumont: I said to him: “There’s going to be some noise. Do you see in this rostrum the whole Duplay family? Do you see Gerard? Do you see Dechamps?” At the same moment Saint-Just began his speech; Tallien interrupted him and tore the veil. Louis Legendre at the Convention March 26 1795

One of those who had witnessed the outcome of this catastrophe (the execution on 10 thermidor) told me that he recognized in the crowd Duplay's eldest daughter, who had wanted to see for one last time the man whom her whole family had looked upon as a god. Mémoires d’un prêtre regicide (1829) by Simon-Edme Monnel, page 337.

The widow of the deputy Le Bas, who gave birth to the man who was to be my teacher, was one of the daughters of the carpenter Duplay. This Duplay family had become Robespierre’s family. He lived with them, and when he died, he was engaged to Mademoiselle Éléonore, the sister of Madame Le Bas. The fiancée mourned Robespierre up until her death. This whole family was closely united, and the memory of the deceased contributed not a little to this union. Premières années, (1901) by Jules Simon, p. 181-187.

#robespierre#éléonore duplay#frev#frev friendships#poor éléonore#she can choose between getting depicted as either#a - a blind fanatic#b - a clueless little girl#c - an ambitious seducer#d - someone who was above ”the weaknesses and fragility of her sex”#I guess the last one is the least bad but still more or less akin to saying ”you’re pretty smart for being a girl”#your aunt did not go to prison for almost a whole year for this philippe!#éléonore possibly being present for the session of 9 thermidor and the execution on 10 thermidor though…💀

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

@biodiversitypix.bsky.social

Revue horticole. Paris: Librairie agricole de la maison rustique, 1829-1974.

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Journal des Dames et des Modes, Costumes Parisiens, 10 mai 1829, (2693): Chapeau de paille de riz du magasin de Mme La Rochelle, Rue de Richelieu, No. 93. Robe de gros de Indes garnie d'un volant à tête découpée. Poignets de mousseline plissés et brodés. Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Netherlands

Hat in 'paille de riz', from the La Rochelle shop. Dress of 'gros de Indes', decorated with a wrinkled strip of fabric, which is serrated at the top. Pleated muslin cuffs with embroidery. Further accessories: necklace with key pendant, gloves, flat shoes with crossed straps and square toes. The print is part of the fashion magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, published by Pierre de la Mésangère, Paris, 1797-1839.

#Journal des Dames et des Modes#19th century#1820s#1829#on this day#May 10#periodical#fashion#fashion plate#color#description#rijksmuseum#dress#collar#gigot#hat

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Wednesday January 28th 1829 William Burke, of "Burke and Hare" fame was executed.

First and foremost, Burke and Hare were not bodysnatchers, graverobbers or "Resurrection men" as is often banded around. They may gotten the idea of selling bodies from the men who carried out such crimes, but they were too lazy to go around digging up cadavers, they instead decided to bump off people themselves, the sell them to the eminent Dr Knox lecturer on anatomy at the University Edinburgh.

The method became known as "Burking" after the subject of this post. There is an 19th century verse that sums them up.....

Up the close and doon the stair,

But and ben' wi' Burke and Hare.

Burke's the butcher, Hare's the thief,

Knox the boy that buys the beef.

The demand for dead bodies in Edinburgh was created by a new way of teaching anatomy, called the Paris Method, which demanded that every student be given a corpse of his own to dissect, rather than simply watching a single lecturer do it at the front of the room. This meant a great many more cadavers were needed, but the only legal source of them was bodies from the gallows. Even with a high amount of executions that supply could never hope to keep pace with the new demand, and many anatomists resorted to buying bodies from grave-robbers instead.

The first body they sold was that of an old pensioner who died of natural causes while owing rent at the Tanner’s Close boarding house Hare ran with his wife Mary. Hare recruited Burke – another tenant there – to help him recoup his losses for the rent by selling the old man’s body to Knox. That was in December 1827.

Realising they were on to a good thing, Burke & Hare then turned to murder. They would choose a vulnerable figure from the streets of Edinburgh – almost always a woman - invite her back to Tanner’s Close and then feed her whisky till she passed out. As soon as their victim was asleep, one or other of the men would block her nose and mouth to prevent her breathing while the other lay across her body to keep her still.

This is Burke’s own description of the process:

“When we kept the mouth and nose shut a very few minutes, they could make no resistance, but would convulse and make a rumbling noise in their belly for some time. After they had ceased crying and making resistance, we left them to die.”

They killed 15 people in this way and sold all the bodies to Knox, who turned a blind eye to the cadavers’ origins in order to safeguard his supply.

Burke & Hare were finally caught in November 1828, by which time they had become careless enough to let one of their victim’s bodies be discovered. Fearing they would not get a conviction otherwise, the authorities persuaded Hare to turn King’s evidence in return for immunity. This ensured that Burke alone hanged for their crimes. Many people in Edinburgh thought that Hare - and Knox - should have died beside him and riots occurred afterwards, one outside the home of Knox.

This sensational story made headlines throughout the world, making Burke & Hare two of the most famous killers this country has even seen. Some of us in Edinburgh know the spate of crimes as The West Port Murders, Tanners Close in the shadow of Edinburgh Castle to the west is long gone but the area of The West Port, meaning Westgate, still bares witness to the enterprising duo, a "strip bar" in what is nicknamed "The Pubic Triangle" is called The Burke and Hare, I think they might have approved!

Finally, the literature of the West Port murders inspired that grisliest of Robert Louis Stevenson's tales, The Body Snatcher.

The pic comes from a broadsheet, the newspaper of the day, if you have the time and stamina, here is full account of the trial......https://archive.org/.../burkehar.../burkehare00burk_djvu.txt

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Everett Millais (1829-1896) "Mercy: St Bartholomew’s Day, 1572" (1886) Oil on canvas Pre-Raphaelite Located in the Tate Gallery, London, England The painting portrays an imaginary incident at the time of the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre in Paris on 24 August 1572, when thousands of Protestants were slaughtered by Catholics. A Nun begs for '"Mercy"' on behalf of the hapless Protestants, but the man pulls her arm away and moves to follow the call to arms indicated by the Friar who beckons from the open doorway.

#paintings#art#artwork#history painting#french history#john everett millais#oil on canvas#pre raphaelite#pre raphaelism#tate gallery#museum#art gallery#english artist#british artist#catholocism#protestantism#violence#costume#costumes#history#1880s#late 1800s#late 19th century#a queue work of art

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS DAY IN GAY HISTORY

based on: The White Crane Institute's 'Gay Wisdom', Gay Birthdays, Gay For Today, Famous GLBT, glbt-Gay Encylopedia, Today in Gay History, Wikipedia, and more … January 7

Bayeux Tapestry - hawking

1130 – On this date the medieval poet Baldric Of Dol died (b.circa 1050). He was abbot of Bourgueil from 1079 to 1106, then bishop of Dol-en-Bretagne from 1107 until his death.

Balderic's poetic works were written almost entirely while abbot at Bourgueil. The 256 extant poems are found almost exclusively in a single contemporary manuscript which is most likely an authorized copy. They consist of a wide range of poetic forms ranging from epitaphs, riddles and epistolary poems to longer pieces such as an interpretative defense of Greek mythology. A praise poem for Adela of Normandy describes something very like the Bayeux Tapestry within its 1,368 lines. Two themes dominate his works: desire/friendship (amor)—including paedophiliac—and game/poetry (iocus).

In his collection My Dear Boy: Gay Love Letters through the Centuries, the scholar Rictor Norton publishes Baldric's many letters to male lovers.

1829 – William Maxwell is the last English sailor hanged for sodomy.

1899 – Francis Poulenc, French composer (d.1963); Poulenc was one of the first out Gay composers. His first serious relationship was with painter Richard Chanlaire to whom he dedicated his Concert champêtre: "You have changed my life, you are the sunshine of my thirty years, a reason for living and working." He also once said, "You know that I am as sincere in my faith, without any messianic screamings, as I am in my Parisian sexuality."

Poulenc also had a number of relationships with women. He fathered a daughter, Marie-Ange, although he never formally admitted that he was indeed her father. He was also a very close friend of the singer Pierre Bernac for whom he wrote many songs; some sources have hinted that this long friendship had sexual undertones; however, the now-published correspondence between the two men strongly suggests that this was not the case.

Poulenc's life was one of inner struggle. Having been born and raised a Roman Catholic, he struggled throughout his life between coming to terms with his "unorthodox" sexual "appetites" and maintaining his religious convictions.

Poulenc was profoundly affected by the death of friends. First came the death of the young woman he had hoped to marry, Raymonde Linossier. While Poulenc admitted to having no sexual interest in Linossier, they had been lifelong friends. Then, in 1923 he was "unable to do anything" for two days after the death from typhoid fever of his 20-year old friend, novelist Raymond Radiguet, Jean Cocteau's lover. However, two weeks later he had moved on, joking to Sergei Diaghilev at the rehearsals he was unable to leave, about helping a dancer "warm up."

In 1936, Poulenc was profoundly affected by the death of another composer, Pierre-Octave Ferroud, who was decapitated in an automobile accident in Hungary. This led him to his first visit to the shrine of the Black Virgin of Rocamadour. Here, before the statue of the Madonna with a young child on her lap, Poulenc experienced a life-changing transformation. Thereafter his work took on more religious themes, beginning with the Litanies à la vierge noire (1936). In 1949, Poulenc experienced the death of another friend, the artist Christian Bérard, for whom he composed his Stabat Mater (1950).

Poulenc died of heart failure in Paris on 30 January 1963 and is buried at the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

1917 – Alfred Freedman (d.2011), who was responsible for removing homosexuality from the list of mental illnesses, was born in Albany, New York. After earning his undergraduate degree at Cornell University in 1937, Freedman graduated from the University of Minnesota Medical School in 1941. He began an internship at Harlem Hospital but left before completion to enlist in the United States Army Air Corps. He left the service having attained the rank of Major.

After initially studying neuropsychology, Freedman trained in both general and child psychiatry, undertaking a residency at Bellevue Hospital. He became the chief of child psychiatry at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center, a post in which he served for five years, before becoming the first person to serve full-time as the department of psychiatry Chairman at New York Medical College, a post which he held for 30 years.

In 1972, Freedman was approached by the Committee of Concerned Psychiatrists, a group of young reform-minded doctors, who encouraged him to run for the presidency of the American Psychiatric Association. He won the election by 3 votes out of some 9,000 that were cast.

In his position as president, Freedman immediately supported a resolution offered by Robert L. Spitzer to delete homosexuality from the list of mental illness diagnoses. On December 15, 1973, the APA's board of trustees voted 13—0 in favor of the resolution, which stated that "by itself, homosexuality does not meet the criteria for being a psychiatric disorder" and that "We will no longer insist on a label of sickness for individuals who insist that they are well and demonstrate no generalized impairment in social effectiveness."

LGBT rights organizations have hailed this decision as one of the greatest advances for gay equality in the United States. Freedman himself believed that passing this resolution was the most important accomplishment of his one-year tenure as president. A second resolution called for an end to discrimination based on sexual orientation and the repeal of laws against consensual gay sex.

Alfred Freedman died in Manhattan on April 17, 2011, following complications after surgery to treat a hip fracture.

1919 – Robert Duncan, American poet, born (d.1988); An American poet and a student of H.D. (Hilda Doolittle), who spent most of his career in and around San Francisco. Though associated with any number of literary traditions and schools, Duncan is often identified with the New American Poetry and Black Mountain Poets.

Duncan's mature work emerged in the 1950s from of Beat culture and today he is also identified as a key figure in the San Francisco Renaissance. Duncan's name figures prominently in the history of pre-Stonewall Gay culture, particularly with the publication of his The Homosexual in Society.

Duncan had his first homosexual relationship with a male instructor he had met in Berkeley. In 1941 he was drafted and declared his homosexuality to get discharged. In 1943, he had his first heterosexual relationship. This ended in a short, disastrous marriage.

In 1944, he published The Homosexual in Society, an essay in which he compared the plight of homosexuals with that of African Americans and Jews. The immediate consequence of this brave essay was that John Crowe Ransom refused to publish a previously accepted poem of Duncan's in Kenyon Review, thus initiating Duncan's exclusion from the mainstream of American poetry.

Also in 1944, Duncan had a relationship with the abstract expressionist painter Robert De Niro, Sr., the father of famed actor Robert De Niro, Jr.

Duncan was the first poet to use the word "cocksucker" in print, and the first to strip to the buff during a reading. Nevertheless, he is in spirit, if not in fact, a modern romantic whose best work is instantly engaging by the standards of the purest lyrical traditions.

In 1951 Duncan met the artist Jess Collins and began a collaboration and partnership that lasted 37 years till Duncan's death in 1988.

1946 – Jann Wenner is the co-founder and publisher of the music and politics biweekly Rolling Stone, as well as the current owner of Men's Journal and Us Weekly magazines.

In 1967, Wenner and Ralph J. Gleason founded Rolling Stone in San Francisco. To get the magazine off the ground, Wenner borrowed $7,500 from family members and from the family of his soon-to-be wife, Jane Schindelheim. In the summer following the start of the magazine, Wenner and Schindelheim were married in a small Jewish ceremony.

In 1995, Wenner found himself in the middle of a media storm when it was revealed that he was leaving his wife Jane after more than 25 years of marriage and had become involved in a relationship with Matt Nye, a former male model turned fashion designer. Wenner's outing, which may or may not have been at his own instigation, seems to have had little effect on his business empire, but it inspired a number of accusations regarding an alleged "Velvet Mafia" of powerful closeted gay men.

Although it had long been rumored that Wenner's marriage was an "open" one and gossip of his bisexuality was widespread and had been mentioned in gay magazines, in 1995 he was publicly outed—on the front page of the Wall Street Journal, no less—when the newspaper revealed that Wenner had left his wife of 28 years for Nye, a considerably younger man who was a former Calvin Klein underwear model.

Rumors of an alleged conspiracy to suppress the news began to circulate. Several journalists reported that the so-called "Velvet Mafia"—a coterie of powerful media, entertainment, and fashion executives who are reputedly gay—had threatened to pull advertising from any publication that wrote about the breakup.

1969 – Rex Lee is an American actor. He is best known for his role as Lloyd Lee in the HBO series Entourage and his role as Elliot Park in the television sitcom Young & Hungry.

Lee was born in Warren, Ohio. His parents emigrated from Korea to the United States. He grew up in the states of Massachusetts and California. He graduated from the Oberlin Conservatory of Music in 1990. Although Lee was studying to be a professional pianist, he decided he wanted to act after taking a theater class in college.

Prior to landing the role on Entourage, Lee had various jobs including performing in the children's theater company, Imagination Company, as well as working as a casting assistant. He was the casting director for the TV movie The Cure for a Diseased Life. Lee has also played roles on a variety of TV shows, including Twins, What About Brian and Maurice on two episodes of Zoey 101.

On Entourage, Lee played Lloyd Lee, the gay assistant to Ari Gold, the character played by Jeremy Piven — eventually becoming an agent and interim head of TMA's television department. Lee began his role in the first episode of the show's second season, "The Boys Are Back in Town", which introduced Lloyd as the replacement to Ari's previous assistant. Lee won the award for Outstanding Supporting Actor, Television at the AZN Asian Excellence Awards in 2007 and 2008.

Lee had a series regular role in the first two seasons of the ABC sitcom Suburgatory, playing Mr. Wolfe, a clueless high school guidance counselor. He appeared as one of the judges at Nationals in the Fox Television Comedy-Drama Glee in season 3. In 2014, he had a starring role in the ABC Family (later rebranded as Freeform) television sitcom Young & Hungry where he plays Elliot Park, the publicist and "right-hand man" to a young tech entrepreneur named Josh. Young & Hungry ran for five seasons, concluding in 2018.

Lee is gay; he came out to his parents when he was 22. In an interview from 2011, Lee said that he was single and looking for something permanent, but that it was difficult to find the right relationship.

1969 – David Yost is an American actor and producer known for his role of Billy Cranston on the television series Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, Mighty Morphin Power Rangers: The Movie and Power Rangers Zeo.

Yost was born in Council Bluffs, Iowa and moved around throughout the United States, winning many gymnastics competitions nationally, most notably the state championships Iowa and Montana. In 1991, graduated from Graceland University in Lamoni, Iowa with a B.A. in Communication and Dramatic Arts. He moved to California with hopes of becoming an actor and auditioned for a role in the Power Rangers series only three months after arriving. He won the part of Billy Cranston, the Blue Power Ranger.

Yost starred in more than two hundred episodes of the show's first four seasons. He was the only Ranger to appear in every single episode of the original series, Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, playing the part of Billy, the Blue Ranger. With powers and motifs based on creatures such as the Triceratops and Wolf, the Mighty Morphin Blue Ranger is still one of the most popular in the franchise thanks to Yost's commitment to the role; Billy never switched colors or passed on his power coins to successors like the rest of the original cast. Yost's most high-profile work was his appearance in Mighty Morphin Power Rangers: The Movie, which took in over thirty million dollars at the box office in 1995. The movie was in theaters between the second and third seasons of M.M.P.R. and served as a non-canonical alternate opening for the third season.

After Mighty Morphin Power Rangers ended and Power Rangers Zeo began in the fourth season, Yost stayed as Billy, but Billy's role within the show changed. Instead of his previous role as a Power Ranger, he became a technical advisor to the others. Yost eventually left the show toward the end of the Power Rangers Zeo season. His character's final episode, "Rangers of Two Worlds", employed footage from previous episodes as well as vocal work from a separate, uncredited actor, to conceal the fact that Yost was not present during the taping. A tribute to the Blue Ranger and Billy was seen in the closing credits of this last Billy episode.

While it was originally believed that he had left the series due to insufficient pay, Yost later revealed in his 2010 interview with No Pink Spandex that he left the series because he could no longer handle harassment by the production crew that targeted his sexual orientation. According to Yost, he was often called a "faggot", and the producers frequently questioned other cast members in private about Yost's sexuality. Yost left late in the fourth season after a week of contemplation instead of continuing work another six months into the second film. He claims that his co-workers involved with writing, filming and producing the show considered him "not worthy" to be where he was and that he "could not be a superhero" because of his homosexuality.

After Yost left Power Rangers, he tried to get rid of his homosexuality with conversion therapy for two years, but this failed. Eventually Yost had a nervous breakdown which resulted in his psychiatric hospitalization for five weeks. After Yost checked out, he moved to Mexico for a year and eventually accepted his sexuality.

In 2002, Yost performed in a play called Fallen Guardian Angels at "the complex" located in Los Angeles for A.P.L.A. (A.I.D.S. Project Los Angeles). The play was about six actors dealing with HIV in various situations. The proceeds went to benefit The Children's Hospitals AIDS Center. The entire production raised over $25,000 and Yost himself raised $5,000 for the hospital and received good reviews from LA Weekly Theatre.

1977 – John Gidding is a Turkish-American architect, television personality, and former fashion model.

Gidding was born in Istanbul, Turkey to an American father and a Turkish mother. He lived in Turkey until moving to the United States for college after attending Leysin American School in Leysin, Switzerland. He graduated from Yale University in 1999 with a BA in architecture, then the Harvard Graduate School of Design with a Master's in architecture.

At Yale he sang a cappella with The Society of Orpheus and Bacchus, and choral music with the Yale Glee Club, and at Harvard he sang with the Harvard-Radcliffe Collegium Musicum. He was voted one of "Yale's 50 Most Beautiful People" in 1999 by Rumpus Magazine, one of "Boston's 50 Most Eligible Bachelors" by The Improper Bostonian in 2002, one of "Atlanta's 50 Most Beautiful People" by Jezebel Magazine and as one of Atlanta Homes and Lifestyles's "Emerging Talent: Twenty Under 40" in 2008.

He is openly gay and, as of August 2013, married to dancer Damian Smith.

Gidding started modeling in 2000 as a graduate student, performing runway shows for Armani, Gucci, and Hugo Boss before being represented by Wilhelmina Models in New York City. He's also been on the covers of numerous romance novels.

Gidding moved to New York City where he started John Gidding Design, Inc. after working for two years as a landscape architect for Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates.

Gidding's start in television was with the ABC Family TV show Knock First, where he and three other designers took turns making over teenagers' bedrooms. Designed to Sell (Giddings' previous show from 2006 to 2011) was canceled in early 2011 but still airs repeats on HGTV, and Knock First is still running in syndication internationally.

He is currently best known for being the architect-designer on Curb Appeal:The Block where his team spends $20,000 on improvements to the exterior landscaping of chosen homeowners. Less expensive touch-ups are done for 2 or 3 nearby neighbors' homes to improve overall neighborhood property values.

1989 – Stephen Wrabel, better known by his stage name Wrabel, is an American musician, singer and songwriter based in Los Angeles.

Wrabel attended high school at The Kinkaid School in Houston, Texas. After high school, he studied at the Berklee College of Music for a semester until he left Boston to move to LA and focus on songwriting. He got his first big break when he was signed to Pulse Recording as a songwriter.

In 2010, Wrabel recorded the theme song for the NBC game show Minute to Win It, "Get Up", produced by Eve Nelson.

Wrabel was signed to Island Def Jam in 2012.

In 2014, Dutch DJ Afrojack released a version of Wrabel's song "Ten Feet Tall", resulting in an international hit. The song premiered in the United States during Super Bowl XLVIII in a Bud Light commercial and was viewed by around 100 million viewers. Wrabel later released the original piano-based version of the song on May 19, 2014. BuzzFeed named the Afrojack version of "Ten Feet Tall" one of the "35 Best Pop Songs You May Have Missed This Summer".

Wrabel is gay. His song "11 Blocks" is autobiographical describing his feelings about his first love who had moved 11 blocks away from him in California. In his song "Bloodstain", directed by Isaac Rentz, the video displays suffering and heartache in a relationship, while the star Wrabel is fighting for his life.

1990 – Michael Sam is an American football defensive end. He attended the University of Missouri, where he played college football for the Missouri Tigers football team for four years. Recruited by a number of colleges, he accepted a scholarship with Missouri. He was a consensus All-American and the Southeastern Conference Defensive Player of the Year as a senior.

Sam is the seventh of eight children born to JoAnn and Michael Sam, Sr. His parents separated when he was young. As a child, Sam watched one of his older brothers die from a gunshot wound. Another older brother has been missing since 1998, and his other two brothers are both imprisoned. A sister who was born before him died in infancy. At one point in his childhood, Sam lived in his mother's car. He was once accidentally maced by police who were arresting one of his brothers.

Sam argued with his mother over playing football, as she did not agree with those pursuits. Sam often stayed with friends while in high school; the parents of a classmate gave him a bedroom in their house and had him complete household chores. Sam is the first member of his family to attend college.

After completing his college football career, Sam publicly came out as gay. If he were to be signed by a National Football League (NFL) team, which analysts think is likely, he would become the first active NFL player to have declared his homosexuality publicly.

In August 2013, Sam took the opportunity of a team introduce-yourself session to inform his Missouri teammates that he was gay, and found them supportive. He avoided talking to the media to avoid addressing rumors of his sexuality. He came out to his father a week before coming out publicly. The New York Times wrote that his father, a self-described "old-school ... man-and-a-woman type of guy", said "I don’t want my grandkids raised in that kind of environment." His father told the Galveston Daily News that he was "terribly misquoted", though The Times maintained that he was quoted "accurately and fairly."

On February 9, 2014, he announced that he was gay in an interview with Chris Connelly on ESPN's Outside the Lines, becoming one of the first publicly out college football players. If he is drafted in the 2014 NFL Draft or signed by an NFL team as an undrafted free agent, he could become the first active player who was publicly out in NFL history. Though he was projected as a third- or fourth-round pick in the NFL Draft, anonymous NFL executives told Sports Illustrated that they expect Sam to fall in the draft as a result of his announcement. Those statements caused National Football League Players Association executive director DeMaurice Smith to respond that any team official who anonymously downgrades Sam is "gutless". From jail, his brother Josh said "I'm proud of him for not becoming like me. I still love him, whatever his lifestyle is. He's still my brother and I love him."

On February 15, Sam returned to Missouri with the Tigers football team to accept the 2014 Cotton Bowl championship trophy at a ceremony held at the halftime of a Missouri Tigers basketball game at Mizzou Arena. It was the first visit to his alma mater since he came out as gay. Anti-gay activist Shirley Phelps-Roper and about 15 other members of the Westboro Baptist Church, an organization widely considered a hate group, protested his appearance. Students organized a counter-protest numbering in the hundreds if not thousands, assembling a "human wall" in front of the protesters.

In May, 2014, Sam was drafted by St Louis Rams. He celebrated with a kiss for his boyfriend Vito Cammisano at an NFL draft party. The kiss went viral.

youtube

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Education of Achilles by the Centaur Chiron

Artist: Jean-Baptiste Regnault (French, 1754–1829)

Date: 1782

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Collection: Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Description

The story depicted in this painting is a well known story from Greek mythology. One of the characters in this painting is Chiron who is noted as being a brave and noble centaur. He is also noted as being the teacher of many great Greek men who had been sent as children to be the students of the centaur Chiron. One of the people sent to train under him was the boy Achilles. Among others, Chiron taught Achilles how to wrestle, sword fight, and the painting above shows how to shoot a bow well.

#mythological art#centaur chiron#achilles#18th century painting#european#jean baptiste regnault#greek mythology#oil on canvas#louvre museum#france#lion#lyre#bow#landscape#french painter

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

what are your thoughts on tertius lydgate wrt marking shifts in discourses of medicine? his position in the novel fascinated me as someone who feels very strongly about the role of doctors in society, and I’m curious to hear your thoughts on the matter

YES lydgate rules so hard in my personal pantheon of doctor characters. sorry this has been in my inbox for a thousand years i had was rotating.

so first of all one of the things that makes 'middlemarch' interesting is that it's a historical novel. so, when george eliot creates a doctor character for the year 1829, writing from 40 or so years later, she's using him to comment on (her perception of) changes to medical science in britain over the course of several decades. so for instance, the fact that lydgate trained in edinburgh and paris tells us immediately that we're supposed to understand him not just as a member of a newly 'respectable' profession, but specifically as having a viewpoint that is informed by radical student politics (edinburgh) and conceptions of the doctor as a social reformer (paris) as well as the research traditions of raspail and bichat. indeed this is why lydgate's crusade in town includes his ideas about sanitation and public health; in contradistinction to the other physicians, he sees his medical and scientific authority as giving him the ability and responsibility to reform the town more broadly. like his parisian counterparts, lydgate clearly sees a link between, eg, cholera and more general social and political unrest. he fashions himself as someone who can doctor the social body as much as the individual patient; given his parisian training we can place him loosely in a social-hygienist context here.

lydgate is also a pretty early example in british literature of a doctor character who's presented as a) not a charlatan and b) heroic explicitly on the basis of his medical and scientific status. british medical practitioners were subject to a new licensure requirement in 1815 i believe (i'd have to double check this date i don't read as much in 19thc britain); 'middlemarch' was written around 1870 and set in 1829–32. so, for eliot, lydgate was genuinely part of a markedly new wave of physicians—men who were licensed (read: state-approved) and occupied a new social position. lydgate is also minor aristocracy, which is part of what makes it possible for him to scoff at the town's older physicians, but much of his social position in the town is accrued in conjunction with the newly and increasingly prestigious status of his profession. this is not really a character type that would have been plausible in a realist novel set in the same country a generation or two earlier.

eliot herself was married to a man of science and also kept abreast of medical and scientific ideas (for example, she was extremely interested in phrenology, an influence you can see throughout 'middlemarch'), and lydgate is very much a man of the times in this respect: he diagnoses george's scarlet fever in the early stage, for example, and refuses to dispense his own prescriptions or to take money from pharmacists. these, along with his emphasis on public health and sanitation measures, mark him as not just an idealist but someone whose medical practice was genuinely steeped in current principles of scientific and ethical reform. even his embrace of bichat's tissue theory, though presented somewhat vaguely, would have signalled to a reader familiar with recent anatomical theories that lydgate was not just a fashionable thinker (bichat died in about 1802, but his work came to popularity over the next 3-4 decades in england and france) but also a precise and naturalistic one, aligning himself with a research tradition that emphasised specific, local lesions as etiological agents (compare this to the brain-localisation ideas of the phrenologists).

ultimately, lydgate's tragedy is that his medical knowledge isn't matched by any social acuity, and his match with rosamond is dissatisfying for both of them. i don't read this as eliot condemning the aspirational early stages of lydgate's career; his mistakes are all made in the interpersonal arena, with both rosamond and the raffles affair. had he played these situations smarter, who knows what he may or may not have accomplished for the residents of middlemarch. instead, he ends the book as a successful but dissatisfied physician to the wealthy, in a position of financial security and medical specialisation but without the kind of moral or political status that he sought earlier in the book by presenting himself as both a social and medical reformer. eliot thus engages, i think, another new type of doctor character: lydgate at the end of the book still has no trace of the quackery or charlatanism that characterised many previous representations of doctors, but he's also been purged of the youthful idealism that pervaded the edinburgh and paris medical education he received. the social status he attains at the end of his life is based on his wealth and the general respectability of the medical profession; treating gout doesn't give him any higher prestige than that, and certainly not the kind of moral authority or fulfillment he wanted back in middlemarch.

so, and recognising that this sort of leaves aside a lot of the psychological nuance of the novel, lydgate's storyline gets at two of the major historical points eliot is interested in. first there's the changing status of british medicine and medical practitioners. lydgate begins the novel as the self-styled hero-reformer; experiences a social fall from grace that compounds with the resistance he already faces from the other town physicians for the threat he poses to their professional status; and ends as the consummate specialist, performing the same boring, lucrative work day in and day out for wealthy londoners (note also the use of gout here to indicate a high degree of moral lassitude and overconsumption among his patients, lol). secondly, and relatedly, there's a shift in class positions going on here. lydgate's initial position in middlemarch is as minor (not wealthy) nobility; by the end of the book he's in a newly high-status professional class, has gained more wealth (though ofc not enough for rosamond), and has been forced out of the countryside. this all tracks with both the expansion of cities generally in this period, and the strengthening of the middle class / petit bourgeois (consider the 1832 reform bill).

although eliot's own views about medicine were largely concordent with the kind of positivistic naturalism of her peers (see again her interest in phrenology), part of what she does with lydgate is, i think, intended as a warning: here's a confluence of forces that have turned an idealistic public health reformer into a dissatisfied man pursuing his personal material security at the direct expense of his philanthropic and altruistic aims. it's a success story for the medical profession in many ways (financially, reputationally) but also a tragedy in the eyes of anyone who believes that physicians ought to have more responsibility to their patients and their polities than their pocketbooks. we're meant to understand medicine as not just a personal curative, but potentially a socially enlightening force---but, only if its aspirations in this direction aren't hindered by the very forces turning it into a more respectable and lucrative career for the rising professional class.

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

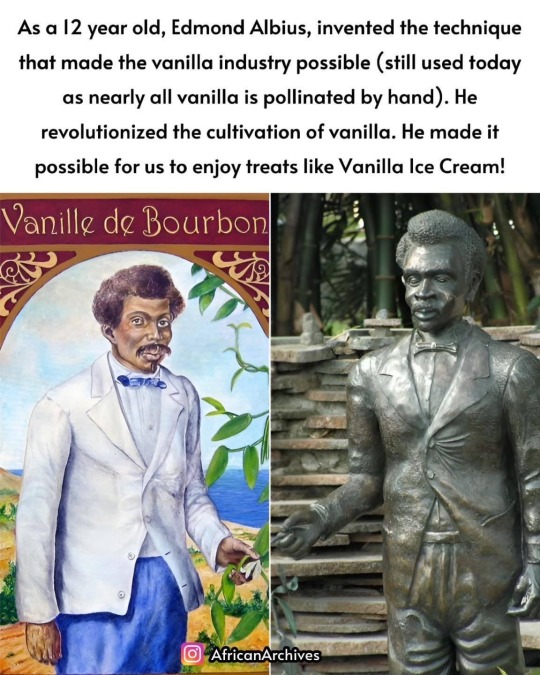

𝗘𝗗𝗠𝗢𝗡𝗗 𝗔𝗟𝗕𝗜𝗨𝗦 (1829-1880)

Edmond Albius was born a slave in 1829, in St. Suzanne, on the island Réunion. His mother died during childbirth, and he never knew his father. In his youth he was sent to work for Botanist Fereol Bellier-Beaumont.

The vanilla plant was flourishing in Mexico, and by the late 18th century, a few plants were sent to Paris, London, Europe and Asia, in hopes of producing the bean in other areas. Although the vine would grow and flower, it would not produce any beans. French colonists brought vanilla beans to Réunion around 1820.

Beaumont had been teaching young Edmond how to tend to the various plants on his estate. He taught him how to hand-pollinate a watermelon plant. Beaumont had previously planted vanilla beans, and had just one vine growing for over twenty years, but was also unable to produce any beans on the vine. Young Edmond began to study the plant and made a discovery. He carefully probed the plant and found the part of the flower that produced the pollen. Edmond then discovered the stigma, the part of the plant that needed to be dusted with the pollen to produce the bean. He used a blade of grass to separate the two flaps and properly fertilized the plant.

Shortly afterwards, while walking through the gardens, Beaumont noticed two packs of vanilla beans flourishing on the vine and was astonished when young Edmond told him that he was responsible for the pollination. Edmond was twelve years old at the time. Beaumont wrote to other plantation owners to tell them his slave Edmond had solved the vanilla bean pollination mystery. He then sent Edmond to other local plantations to teach other slaves how to fertilize the vanilla vine. Within the next twenty to thirty years, Réunion became the world’s largest producer of vanilla beans.

Edmond was rewarded with his freedom, and was given the last name Albius. Beaumont wrote to the governor, asking that Albius be given a cash stipend for his role in the discovery of the fertilization, but received no response. Albius moved to St. Denis and worked as a kitchen servant. He somehow got involved in a jewelry heist and was sentenced to ten years. Beaumont again wrote the governor on his behalf, and the sentence was commuted to five years, and Albius was subsequently released. A man named Jean Michel Claude Richard then set claim to have discovered the fertilization process before Albius. He claimed he visited the island in 1838, and taught a group of horticulturists the technique. Again, Beaumont stepped in and wrote to Réunion’s official historian declaring Albius as the true inventor, giving him all of the credit entirely. The letter survives as part of island history.

Albius returned to live close to Beaumont’s plantation and married. He died on August 9, 1880 at the age of 51 at a hospital in Sainte Suzanne. He never received any profits from his discovery. One hundred years after his death, the mayor of Réunion made amends by erecting a statue of Albius and naming a street and school after him.

#Edmond Albius#vanilla ice cream#vanilla#black history#black history month#vanilla beans#vanilla extract

83 notes

·

View notes

Photo

🌻 Revue horticole. Paris: Librairie agricole de la maison rustique, 1829-1974.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829-1881) Das Urteil des Paris, ca.1869-70 Hamburger Kunsthalle

#art#fine art#european art#classical art#europe#european#oil painting#europa#fine arts#mediterranean#Anselm Feuerbach#german art#german#germany#1800s#mythological art

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lady Reading the Letters of Heloise and Abelard

Artist: Bernard d’Agesci (French, 1756–1829)

Date: circa 1780

Medium: Oil on Canvas

Collection: Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States

Description

This painting depicts a young woman lost in reverie after reading the letters of the ill-fated medieval lovers Heloise and Abelard. The objects on the table beside her—a letter, a sheet of music, and a book of erotic poetry—hint at a life of leisure and a susceptibility to love. In this early picture, Auguste Bernard drew upon history paintings by Peter Paul Rubens and Charles Le Brun, as well as Parisian traditions of genre painting and portraiture pioneered by Jean-Baptiste Greuze. Bernard worked in Paris in the early 1780s and studied in Italy for several years. Upon his return to Paris, he found his career frustrated by the French Revolution and the emergent fashion for the more austere Neoclassical style.

#painting#oil on canvas#lady#letters#heloise and abelard#sheet of music#book#table#woman#costume#reverie#reading#bernard d'agesci#french painter#european art#18th century painting#necklace

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beaux-arts des modes, no. 6, novembre 1937 (New York, Paris, London, Milano, Wien, Bruxelles). Bibliothèque nationale de France

1829 Society robe in crêpe satin with separate boléro. Horizontally shirred front, boléro sleeves of ocelot.

#Beaux-arts des modes#20th century#1930s#1937#publication#fashion#fashion plate#color#description#dress#november color plates#devant et dos#bibliothèque nationale de france

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

For A Century Cincinnati’s Fashionistas Fawned Over A Shade Called ‘Invisible Green’

As the local haberdasheries and modistes swell with shoppers clamoring for appropriate gifts for their kith and kin, what colors do they promote? It seems a silly question these days when, as the old song once claimed, “anything goes,” and the entire spectrum is accessible for plundering in the name of habilimentation. Is there any color particularly fashionable this year?

More than a century ago, that was quite a pertinent inquiry. The wrong shade of your dress might ostracize you from society. Reading antique articles about bygone fashion trends is always entertaining, but there are occasions in which it appears that stylish Cincinnatians were engaged in sorcery. Were there premonitions of Harry Potter’s Invisibility Cloak? Here is the Cincinnati Enquirer from 3 February 1889:

“A pretty house dress is here shown. It is of invisible green soft wool goods with tracings of fawn color, and trimmed with bands of fawn and brighter green.”

And here the Cincinnati Gazette from 8 August 1877:

“The dry goods stores are announcing their last selling off arrangements to close the season, and in a little while fall fashions and dress goods will hold full sway. Respecting the coming season, we are told that the color for street wear will be sage green in its darkest shades, rechristened Marjolaine, or else a very dark, almost an invisible green.”

What in the world is invisible green? Was this something like the recent fad for camouflage patterns in sportswear? Were Cincinnatians attempting to glide down Fourth Street with no one catching a glimpse of them, perhaps skulking toward a discreet rendezvous?

As it turns out, “Invisible Green” as a fashionable color originated not among the ateliers of Paris, but in the gardens of Regency England. As a color, it has, perhaps, more to do with Jane Austen than with later couturières.

Invisible Green was a favorite color of Humphrey Repton, a legendary landscape designer during Jane Austen’s lifetime. Invisible Green was a very dark green oil paint compounded by mixing yellow ochre and black pigments with white lead. The resulting hue proved to be ideal for slathering on wooden and ironwork gates and rails in parks, pleasure grounds, and gardens to render them almost invisible at a distance because of the manner in which this particular hue approximated the natural color of vegetation.

T.H. Vanherman, the premier London “colourman” of his day, described Invisible Green in this manner in 1829:

“The Invisible Green is one of the most pleasant colours for fences, and all work connected with buildings, gardens, or pleasure grounds, as it displays a richness and solidity, and also harmonizes with every object, and is a back-ground and foil to the foliage of fields, trees, and plants, as also to flowers.”

Soon enough, Invisible Green was adopted by the fashionistas, and fabrics in that particular shade were being unloaded at the Cincinnati wharfs as early as 1838. The fashion pages of Cincinnati’s newspapers regularly announced Invisible Green as either the primary color or a trim color for men’s and women’s fashions for the next 60 years.

Yes, men were just as enamored with Invisible Green as were the womenfolk. Here is the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune [4 January 1890]:

“It is stated by fashion authorities that the fashionable color in men’s clothing for spring will be green, and already orders have been given by fashionable tailors for solid invisible green in diagonals and worsteds.”

And here is the Enquirer [21 April 1882], laying down the law on men’s vests for the spring season:

“Vests are all single-breasted, no-collar, closed high with seven or eight buttons, four patch pockets, short in the waist and cut straight across the front. There is no demand for collars on the vest, even dress suits being without them. The finish of the edge corresponds with the coat and the material with the trousers. Fancy vestings are gaining in popularity. Invisible greens, reds or blues form a background for dots, broken designs, checks and bars placed at right angles, touched up with streaks of color.”

Even transportation adopted Invisible Green. The Enquirer [5 May 1882] described the “finest drag in America,” a “drag” being a type of stagecoach pulled by four horses:

“The springs and axles are regular mail-coach make, and have been thoroughly tested and given the highest grading. The wheel hubs are furnished with dust excluders of the best pattern. The body of the drag stands so high that the front wheels can be turned right under it, so that it can be wheeled around in its own length. The seats and facings are of the finest invisible green French cloth.”

We forget, in these kaleidoscopic days of extreme coloration, that the 1800s were not a drab, monochromatic time. Our forebears reveled in color and eye-popping fashion. They were continually putting one another down for violating what we would consider arcane peccadillos in dress. Perhaps the worst insult a woman could land on a social rival was to observe that she was wearing last year’s color.

To read the old fashion pages is to find oneself immersed in a palette of almost psychedelic possibilities. We hear about cadet, mastic, ecru, canary, tobacco, seal, sea water, vine, fawn, wheat, pansy, dahlia, pearl, lilac, claret, gendarme, mulberry chartreuse, absinthe, capucine, nasturtium and moss. So, why not Invisible Green?

So common was this color that a Cincinnati journalist even adopted the pen name of “Invisible Green, Esq.” (More on that fellow at a later date.)

Eventually, after a century of not actually being invisible, the time-hallowed shade of Invisible Green fell out of fashion. The death knell sounded in the form of a joke. It was published in the Cincinnati Post [31 October 1904] and it went like this:

“Servant: The butcher won’t leave no more meat, sir, he says, until he sees the color of your money. “Mr. Hardup: Why – er – tell him it’s invisible green.”

8 notes

·

View notes