#oshi kuji

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#dr. stone#dcst#official media#official art#Cinderella inspired????!?!??#ishigami senku#asagiri gen#chrome#saionji ukyo#nanami ryusui#dr stone#ukyo as the evil stepsister or stepmother?!?!?#brilliant#10/10#no notes#anime#anime art#oshikuji#oshi kuji#dcst x oshikuji#dcst x oshi kuji

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gridman Universe - Oshi Kuji featuring goods with new illustrations from 20 December 2024 to 19 January 2025. Release: Late-March 2025

#gridman universe#ssss.gridman#ssss.dynazenon#rikka takarada#akane shinjou#yume minami#kuji#oshi kuji#official art#anime

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bandai previewed the Ichiban Kuji lottery at the opening day of the Tamagotchi 28th Birthday celebration at OSHI BASE Tokyu Plaza Harujuku, Japan.

#tamapalace#tamagotchi#tmgc#tamatag#virtualpet#bandai#ichibankuji#ichiban kuji#lottery#jp#japan#oshibase#oshi base#celebration#birthday#popup#pop-up#popupstore#pop-upstore#pop-up store

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

I saw Epinagi movie today and holy shiiiiit I've been struck once more by how many fucking LAYERS this relationship has it's not just Pathetic Prince x Reluctant Knight, in fact their relationship is also the complete OPPOSITE to that with Nagi taking the metaphorical prince role. I want to put them in my mouth

#anyway i've had super good oshi luck today got rabi canbadges and portraits for ensta#iharu nui for kai8 AND AND AND the a prize figure from ichiban kuji yesterday!!#and aizen from the bleach wafer i'm eating rn

0 notes

Text

An Introduction to Book 4 of the Nampō Roku: Shoin [書院], Part 2 -- Sōami’s O-kazari Ki [御飾記], and the O-kazari Sho [御飾書].

The O-kazari Ki [御飾記] of Sōami is known from two different versions. The illustrations that were included in Part 1 of this introduction were taken from a manuscript version of the text that was passed down in the Imai family. However, the version that was more widely influential -- it was published as a block-printed facsimile edition¹ -- was titled O-kazari Sho [御飾書]. It was this version that was used by the officials in charge of the arrangement of the Tokugawa Shōgunate’s shoin (and so also adopted for use by the daimyō households during the first century of the Edo period).

From the partial translation of the O-kazari Ki that follows, I have left out the descriptions of the rooms, since these mostly point to their locations within the shōgun’s mansion, as well as descriptions of various irrelevant utensils, since neither of these sets of information have any bearing on the contents of Book Four of the Nampō Roku. As for the O-kazari Sho, I have only attempted to relate its set of sketches to those of the O-kazari Ki, while keeping the text to a minimum.

——————————————–———-—————————————————

◎ O-kazari Ki [御飾記] was written by Sōami [相阿彌; 1472 ~ 1525] in 1523.

Sōami seems to have taken his inspiration from his grandfather’s work², though he has expanded the number of settings included (probably as the residence for the shōgun underwent changes). The twelve relevant sketches below are reproduced from a manuscript copy of this book (probably made by someone other than Sōami himself) that was preserved by the Imai family.

Many of these sketches are accompanied by comments that indicate where the particular oshi-ita or chigai-dana were located in Ashikaga Yoshimasa’s mansion (presumably the Muromachi-dono [室町殿], Muramachi palace -- popularly known as the Hana-no-gosho [花 之 御所], shown above). However, this information is not particularly helpful (with respect to interpreting the arrangements shown in the sketches), since the mansion, which was located northeast of the Kyōto Imperial Palace, was destroyed during the Ōnin wars (all that remains are several marker stones). The comments do suggest, however, that these arrangements were displayed regularly -- rather than being created for one specific occasion and then studiously never repeated again, as is the practice in modern day chanoyu.

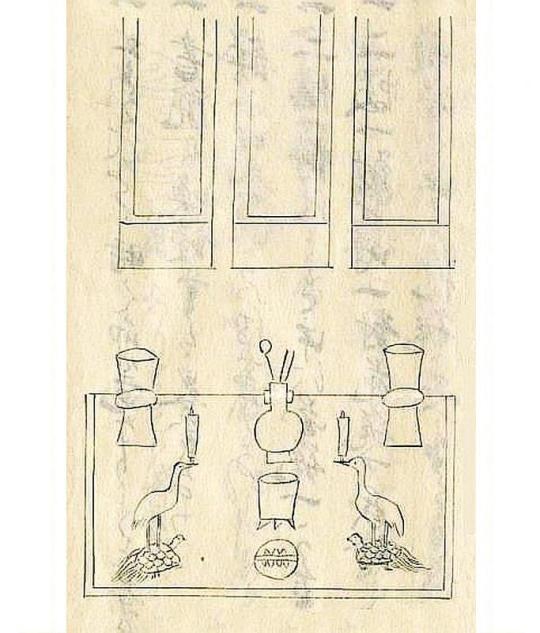

1) An arrangement for a (built-in³) oshi-ita [押板], with four pictorial scrolls and three flower vases. The text reads: naka ha sukoshi oki ni te shikarubeku, mata kōro wo mo okareruru [中ハ少シ大キニテ可然く、又香���ヲモヲカルヽ], which means “with respect to the central [vase], it is appropriate for it to be a little larger [than the other two]; or, on the other hand, a kōro [rather than a vase] may be placed [in the middle position].” It is also important to notice how the four scrolls are oriented.

In his commentary, Sōami expanded upon the ideas expressed above: “when four scrolls are displayed at the same time, it is inappropriate to place the mitsu-gusoku [三具足] (the three objects originally arranged on an altar: a flower vase, a candlestick, and, in the middle, an incense burner) in front. On both sides, a pair of ka-bin [花瓶] (flower-vases), as shown, while in the middle of these another, somewhat larger, ka-bin may be arranged thus. Otherwise, you should put a rather large incense burner [in the center, rather than a third ka-bin]. With four scrolls, this is the true arrangement.”

The scrolls should be hung up in order -- that is, the right-most scroll is hung first, then the second, the third, and finally the scroll on the left (which is where the artist’s signature and name-seals are found). This imitates the way that a horizontal picture scroll is opened up for viewing⁴.

2) An arrangement for the chigai-dana. The writing on the sketch reads: (above) kamo kōro ・ kodō⁵ [鴨香爐・コトウ] (a black-bronze incense burner in the shape of a duck), on a kanban [翰盤] (a low writing-table); ko-bon noseru⁶ katatsuki-tsubo⁷ [小盆載肩衝壺] (a katatsuki, placed on a small tray); dai ni suwaru ・ yu-teki [臺ニスハル・油滴] (sitting on a temmoku-dai, a yu-teki temmoku), bon noseru [盆載] (which has, in turn, been placed on a tray); (below) jikirō [食籠] (a lidded box for sweets or side-dishes).

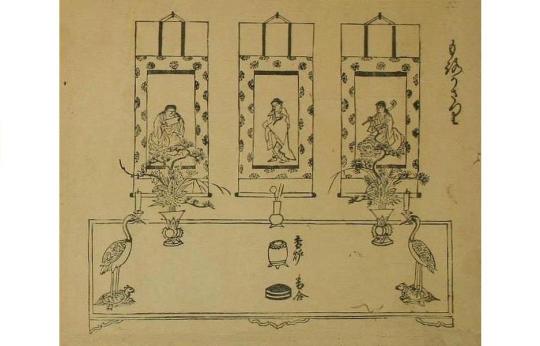

3) The ordinary way to arrange the oshi-ita when a triptych is hung.

The kaki-ire [書入] in the upper right corner of the sketch reads: oshi-ita to chigai-dana no sumi [押板とちかひたなの角], “the corner where the oshi-ita [adjoins] the chigai-dana.”

The scrolls are marked hidari [左] (“left” -- the image to the left of the principal), hon-zon [本尊] (the principal image), and migi [右] ( “right” -- the image to the right of the principal): the positions are determined (as on a Buddhist altar) from the perspective of the central image. (And when the scrolls are hung up, first the hon-zon is hung, then the scroll to its left, and then the one to its right. Note that right and left here should be reversed from our perspective.)

The words joku ni suwaru [卓ニスハル], which are repeated twice, mean “[these objects] should sit on stands [or tables].” In other words, both the pair of flower containers on the right and left, and the collection of objects in the middle⁸, should all be raised up on tables or stands of appropriate sizes.

And, finally, the word kōgō [香合] refers to the object in the front-center position on the middle joku.

About arrangements of this sort, Sōami wrote: “when three paintings are displayed at the same time, [the above sketch shows] the usual way it is done. The mitsu-gusoku [三具足] (a flower vase, a candlestick, and an incense burner) should sit on a table, and on the sides of this a pair of ka-bin, sitting on stands (should be set up); and above, a fūrin [風鈴] (wind-bell) should be suspended.”

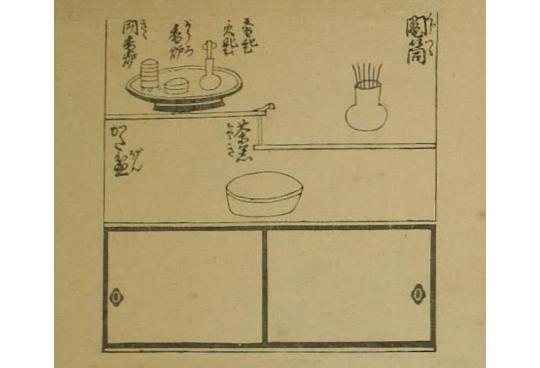

4) The arrangement of the o-chanoyu-dana [御茶湯棚]. The writing reads (above, right to left) ukai-chawan [ウカイ茶ハン] (chawan for passing around -- used when sharing a single bowl of usucha)⁹, dai-shō futatsu [大小二ツ] (large and small -- two sizes of ukai-chawan), dai ni suwaru [臺ニスハル] (the ukai-chawan are sitting on dai); jikirō [食籠] (stacked set of boxes for sweets and side-dishes), hō-bon ni nose [方盆ニ載] (resting on a square tray)¹⁰; (immediately below the shelf, right to left) kenzan mutsu kaku-dai ni suwaru [建山六ツ各臺ニスハル]¹¹ (six Kenzan[-temmoku], each sitting on a dai); naka ko-taikai, mae ni chasen [中小大海 前ニ茶セン] (in the middle is a small-sized taikai, in front of which is the chasen [in a kae-chawan, together with the chakin, and possibly the chashaku]); and below (referring to the kaigu) juro-no-habōki [ジユロノ羽ホウキ] (a type of habōki made with hemp-palm fiber)¹², hi-kaki [火カキ = 火掻き] (a took for raking the fire)¹³.

The phrase chashaku ari [茶杓有], above the shaku-tate, actually refers to the hishaku (which is standing in the shaku-tate together with the hibashi).

The object in front of the shaku-tate seems to have been misdrawn¹⁴. It should be a futaoki -- specifically a kakure-ka [隠れ家] (what is now known as a go-toku [五德] -- that is, a ring with three supporting legs). The mizu-koboshi is shown in the compartment located below the jikirō.

In the compartment below the jikirō (which, in Nōami’s version of this sketch, is fitted with doors -- to hide this unclean object from sight until it was needed), is the mizu-koboshi [水下] -- which Sōami explains should be something like a (probably large) sometsuke-chawan (sometsuke-chawan no te [染付茶ハンノテ]).

Below the sketch are the sumi-tori [炭斗], and what (though unlabeled) seems to be the koboshi (probably to indicate where these things would be placed during the service of tea)¹⁵.

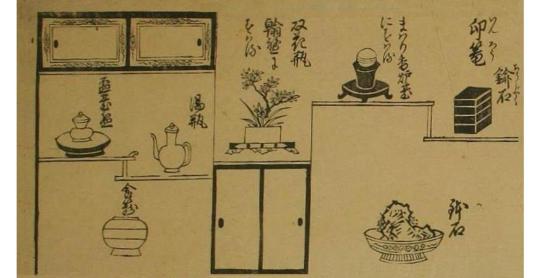

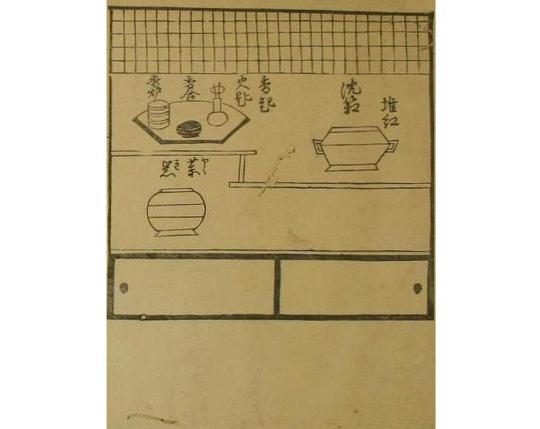

5) The arrangement of objects on the dashi-fuzukue (tsuke-shoin), and its associated chigai-dana¹⁶.

On the side of the sketch showing the chigai-dana, the writing on the sketch reads (from right to left): kuji-zutsu [鬮筒] (a vessel intended to hold the bamboo slips used for one system of Chinese divination¹⁷), below which is written kuji irete [クシ入], which means that “the kuji should be put into" the kuji-zutsu (when it is displayed on the chigai-dana -- the small lines extending upwards from the kuji-zutsu are supposed to represent the kuji); and on the tray, on the upper shelf of the chigai-dana, a kō-saji dai [香匙臺]¹⁸ (a small, vase-like stand in which the incense implements are stood), a kōgō [香合]; and a kiki-kōro [聞香爐] (a small censer that is held in the hand when sniffing incense); and below, a chaki [茶器] (the traditional Korean word for a chaire -- as cha-tsubo [茶壺] is the Chinese word).

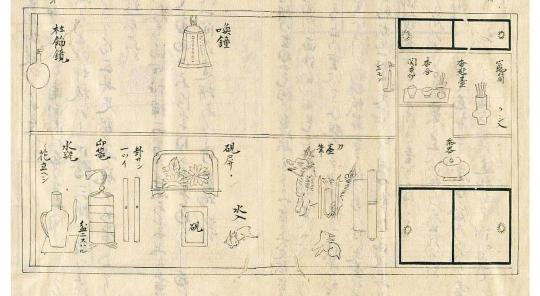

On the dashi-fuzukue (the tsuke-shoin, or built-in writing desk): (hanging on the right pillar) shumoku [シユモク = 撞木] (a wooden hammer-like striker with which the hanging kanshō is sounded); katana [刀], sumi [墨], fude [筆] (the three implements -- a paper-knife, an ink-stick, and a writing brush -- leaning against the hitsu-ga [筆駕], brush rest, which is shaped like a kirin [麒麟], a mythical beast resembling a cross between a deer and a giraffe); a mizu-ire [水入] (shaped like a rabbit); a kenbyō [硯屛] (a miniature standing screen, usually made of pottery, that keeps dust from blowing onto the suzuri -- inkstone); (above) kanshō [喚鐘] (a hanging bell); suzuri [硯] (inkstone); kesan [卦サン = 卦算] (metal paperweights), with the comment hitotsu i [一ツイ], “just one [will suffice];” an inrō [印籠] (a lacquered case for carved name seals and seal-ink); a sui-bin [水瓶]¹⁹, with the comments (on the right) bon ni suwaru [盆ニスハル花立ヘシ] (sitting on a tray), and (on the left) hana tatsu-beshi [花立ヘシ] (it is best if a flower is stood [in the sui-bin]²⁰); (and suspended from the pillar on the left) hashira kazari-kyō [柱飾鏡] (a decorative mirror²¹ displayed on the pillar).

Regarding the arrangement of the objects on the shoin, Sōami wrote: “with respect to the way to decorate the shoin, first the ken-byō [硯屛] (a small screen that protects the ink stone from dust), and second the suzuri [硯] (ink stone) should be placed out. Then, carefully considering the distance between them, the fude-kake [筆架] (brush rest) is placed, and next the mizu-ire [水入] (water dropper); next, the jiku-mono [軸物] (scroll); then the inrō [印籠] (box of name-seals and ink); next the kesan [卦算] (paperweights); next the sui-bin [水瓶] (a water bottle, here used as a flower vase): in every case, whether front to back or side to side, these things should be placed in the middle of the [space available on the] oshi-ita²²; only the suzuri is correctly placed in front of the ken-byō (that is, centered between the ken-byō and the front of the desk).”

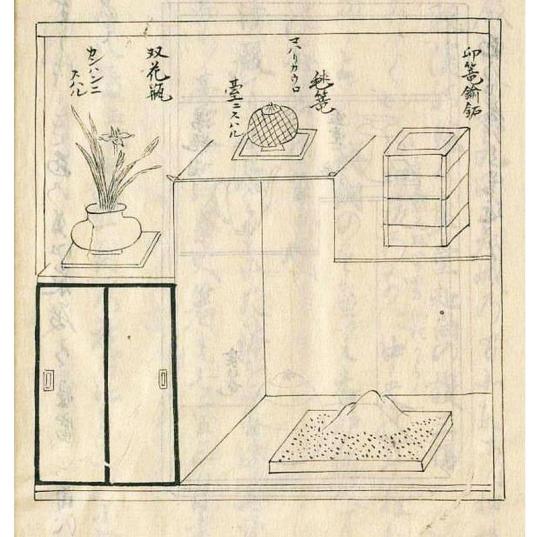

6) Another arrangement for the chigai-dana. From the right, the writing reads: inrō chūseki [印籠 鍮鉐] (an inrō [印籠] made of Mogul brass)²³; a kyūrō [毬籠] (a ball-like incense burner), beside which is written mawari-kōro [マハリカウロ] (a censer that perfumes the air in the room), and the comment dai ni suwaru [臺ニスハル] (sitting on a stand)²⁴; a sō-kabin [双花瓶] (a flower-vase for a more formal flower arrangement -- as opposed to a single flower), with the comment kanban ni suwaru [翰盤] (sitting on a kanban [カンハンニスワル], which is a sort of lap-table used for writing).

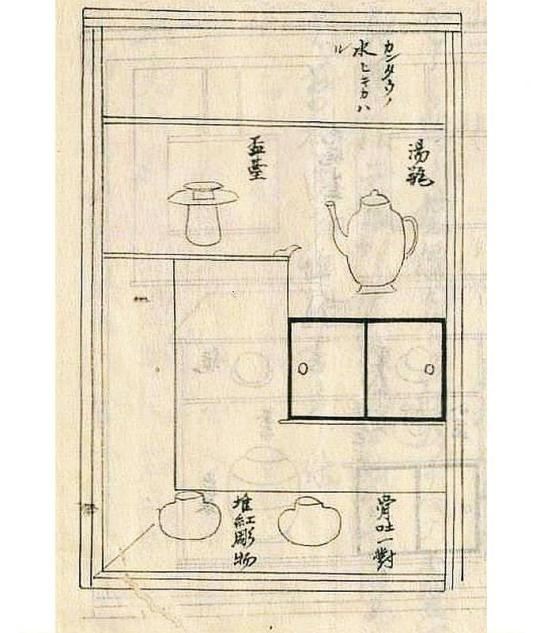

7) A fourth arrangement for the chigai-dana. The objects displayed are: (above, from right to left) a yu-bin [湯瓶] (a usually bronze handled pitcher for hot water -- this object was used when serving usucha in the Chinese manner²⁵); a sakazuki [盃]²⁶ resting on a dai [臺], which assembly was then displayed on a tray (bon [盆]).

(Below) a jikirō [食籠] (a lidded box for sweets or side-dishes -- this one may consist of several layers that stack one on top of the other).

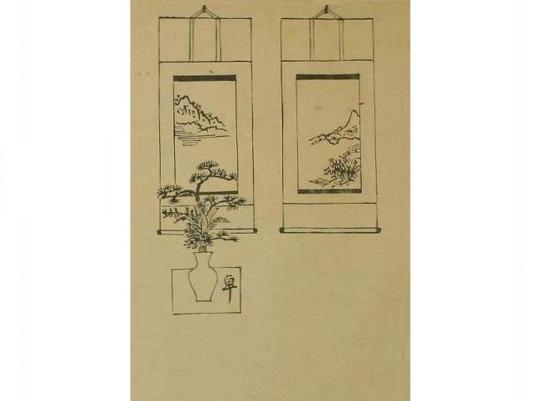

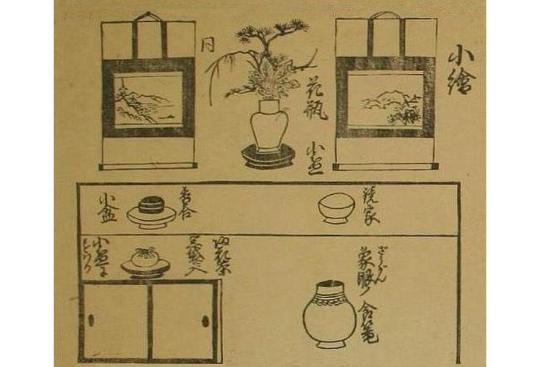

8) Here a portable chigai-dana (which the commentary states was made of shi-dan [紫檀], red sandalwood) has been placed on the oshi-ita, located in the north-west corner of the room, and on the wall above it a pair of small scrolls have been hung.

The shōji [障子]²⁷ featured a painting of autumnal flowers.

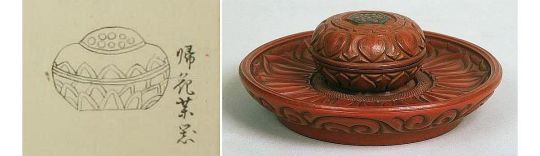

The objects displayed on the tana are: (above) a kabin [花瓶] (flower vase) on a small tray²⁸; (in the middle compartment, from right to left) a kagami [鏡] (bronze mirror), and a kōgō [香合] on a small tray; (and below) a cha-ki [茶器] (tea container)²⁹ [decorated with] zōgan [象眼] (mother-of-pearl and ivory inlay), and (on the shelf) the “Kaeri-bana” chaki [歸花茶器]³⁰, in its fukuro, and [resting] on a small tray.

9) Another arrangement for the chigai-dana. A Kantō-mizuhiki [カンタウノ水ヒキカヽル] (an embroidered valance from China)³¹ is hung (across the top of the opening).

The objects displayed on the chigai-dana are (from the right) a yu-bin [湯瓶] (a bronze pitcher for hot water), and a sakazuki [盃] (saucer for drinking sake) on a dai [臺]; and (below) a pair of hone-haki [骨吐]³², tsui-kō horimono [堆紅彫物] (of carved tsui-kō lacquer).

Sōami also notes that the shōji (the sliding doors of the cupboard beneath the lower shelf of the chigai-dana) bore a painting of the scenery to the southeast of Kyōto (“from Ishiyama [石山] to Seta [勢田], and onward to Ōtsu [大津]” at the southern end of Lake Biwa)

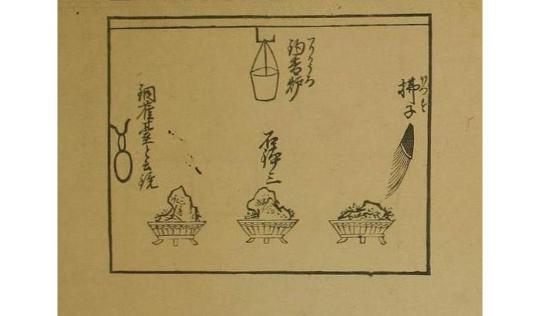

10) This is an arrangement of objects on the dashi-fuzukue (tsuke-shoin). From right to left, a hossu [拂子] (a sort of horse-hair whisk with which monks -- usually of high status, since these tended to be expensive objects -- brushed away insects rather than killing them; and which became a sort of status symbol among the members of the monastic communities) is hung on the right-hand pillar; above is a tsuri-kōro [釣香爐] (a hanging censer)³³, while below on the writing desk are three ishi-bachi [石鉢] (“viewing stones” -- natural stones whose shape suggests scenes from nature -- arranged in basins of granite sand); and, suspended from the left pillar, a Dōjaku-dai to-iu kagami [銅雀臺ト云鏡] (a bronze mirror that is said to have a scene of the “Dōjaku-dai” -- “the Bronze Sparrow Terrace” -- on the back side)³⁴.

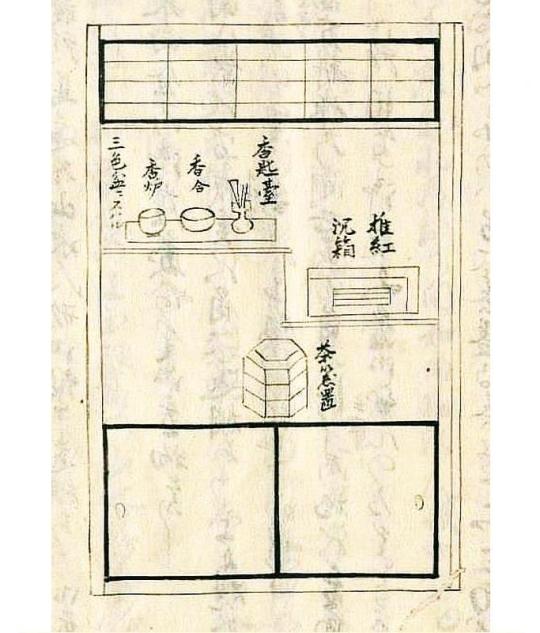

11) This chigai-dana featured a pair of small shōji in the upper wall (for ventilation).

The objects on the shelves are, from right to left, a tsui-kō jin-bako [堆紅沈箱] (a carved lacquer box in which a selection of pieces of wood incense were kept)³⁵; and a kōsaji-dai [香匙臺] (a small, vase-like container in which an incense-spoon and a pair of ebony incense chopsticks were stood), kōgō [香合] (in this case, the kōgō probably contained only the gin-yō [銀葉] -- mica squares on which the pieces of incense wood were burned), and kōro [香爐] were arranged, with the accompanying note san-shoku bon ni suwaru [三色盆ニスハル] (which means “the three objects all are sitting on the tray [together]”)³⁶; and below is placed a cha-ki [茶器]³⁷.

The painting on the shōji featured a scene of a summer landscape, according to Sōami’s notes³⁸.

12) An arrangement for the table placed on the oshi-ita in front of a triptych. This arrangement of the full set of objects is referred to as moro-kazari [もろかざり = 諸飾]³⁹.

The following kaki-ire [書入] was appended to the sketch (perhaps by the original author, Sōami): yo no tsune no kyaku kuru nado ni ha kazarazu; o-nari ha mochiron nari; ika ni mo shōgan⁴⁰ no koto nari; kono soto ni ittsui hana waki ni aru-beshi [よの常の客来るなどにはかさらす。御成は勿論なり。いかにもしやうくわんの事なり。此外に一對花わきにあるへし]: in the case of the more ordinary guests and the like, [the oshi-ita] should not be decorated in this way⁴¹. But when one receives a visit from ones lord, naturally [this arrangement should be employed]. Indeed, the purpose [of this arrangement] it to show [ones] appreciation [for the lord's visit]. A pair of flower [arrangements] should be placed outside [of this table]⁴².

__________________________

¹The date of publication of the block-printed facsimile edition, while clearly of early Edo period vintage, is unknown. The copy is preserved in the Waseda University collection, along with a second manuscript version of the text (which is dated 1762). This subsequent document is titled Higashiyama-dono O-kazari Sho [東山殿御飾書], with the authorship ascribed to Sōami. While generally similar to the block-printed version, the modifications (especially the kaki-ire [書入] additions to the original text) seen in this second edition reflect Edo period preferences and practices. The block-printed edition will be discussed below.

The material included in Book Four of the Nampō Roku shows a closer connection with the O-kazari Ki / O-kazari Sho than to Nōami’s treatise.

²A convincing case could be made for the argument that Sōami's purpose was simply to produce an edited (and updated) version of the Kun-dai Kan Sa-u Chō Ki.

³In other words, this is a permanent oshi-ita, the immediate precursor to the tokonoma (which combined the functions of the oshi-ita with that of the nobleman's mi-chōdai [御帳臺]). An “old style” oshi-ita (made from a Korean table with the legs folded into the box-like top) is considered in the last illustration.

⁴These four scrolls were either originally a single large painting that was cut into parts (to make conservation easier and safer), or a set that was always intended to be hung together (whether by the artist who created the works, or by the dōbō [同朋] who collected them together in Japan). In any case, they are hung up as if they were a single work, starting with the scroll on the side where the painting begins, and ending with the painting (which includes the principal colophon, and the artist's signature and name seals).

In the corresponding plate in the O-kazari Sho [御飾書], the four thumbnail sketches are replaced with the numbers “一 二 三 四” (1, 2, 3, 4), to indicate the order in which the scrolls should be hung.

⁵Kodō [コトウ] means kodō [胡銅], a form of bronze that turns nearly black with age. It is found among both Chinese and old Korean pieces.

⁶Ko-bon nose [小盆載]. The verb noseru [載せる] means to place on (something).

The question here, however, is concerned with the small tray. Jōō is said to have created the small tray for the chaire (according to Rikyū's account, by “dividing the naga-bon in half”); but, since Sōami wrote the O-kazari Ki in 1523 (when Jōō was only 21 years old, and had not really commenced with his study of chanoyu yet), this idea of arranging a chaire on a small tray (when displayed as a decorative object in the shoin) clearly predates Jōō's usage.

What Jōō actually did was: fix the size of the small tray as a function of the size of the chaire that would be placed on it; and, use the small tray as the base for the chaire (and chashaku) during the service of tea. In Sōami's day (and, of course, before), while the chaire was sometimes displayed on a small tray on the chigai-dana, as here*, during the temae it was placed on a naga-bon. In chanoyu very few things are ever truly original: most things are variations of things that were done before, modified toward new ends. __________ *The display of the temmoku and the chaire on the chigai-dana is similar to arranging these things side by side on the naga-bon, but with an important difference: here the chaire is clearly shown to be inferior to the dai-temmoku (in which tea will be served to the shōkyaku) by displaying it on a lower level.

In the gokushin-temae, too, this difference is underscored. The temae begins with the host concentrating his attention on the temmoku-chawan, and it is while the bowl is being warmed (with the chasen resting in it) that the host removes the shifuku from the chaire, cleans the naga-bon and then it, and places it on the naga-bon; after which the chashaku is also cleaned and rested on the tray. This is followed by the chasen-tōshi. While this procedure can be understood as a way to protect the tea as long as possible (the tension is not released from the lid of the chaire until much later in the temae than we would find usual), the fact is that the chaire was always considered inferior to the chawan until the advent of wabi-no-chanoyu, and its focus on showing respect to the utensils.

In the early days, a chawan was used only until it began to be stained by the tea. Once stains became apparent (such as by darkening the crackles in the glaze), the bowl was discarded and replaced by a new one. The chaire, on the other hand -- like the cha-tsubo -- became “better” the longer it was used, since the volatile components of the tea infiltrated into the clay, meaning that, over time, the jar had less and less of a negative impact on the taste and aroma of the tea that it contained (this, however, is why the rule was that the host should always use the same blend of tea -- since shifting blends would result in cross-contamination of the new tea with elements from the old that volatilized from the inside of the jar: in the early days, both the cha-tsubo, and the chaire, were not glazed on the inside).

This idea of “better,” however, while understood in the early days, did not figure into the aesthetic assessment of the chaire: when viewed as art-objects, the classical chaire were simply not in the same class as the yō-hen [窯變] and yu-teki [油滴] bowls selected for use as chawan (which, in addition to their inherent aesthetic appeal, usually sported a fukurin [覆輪] of gold around the rim of the bowl).

⁷Katatsuki-tsubo [肩衝壺]. The word “chaire” [茶入] was used primarily by the machi-shū practitioners of wabi-chanoyu (probably so as to avoid confusion between the small tea container and the large storage jars for leaf tea).

Sōami follows the continental practice of referring to the tea container as a “cha-tsubo” [茶壺]. This is the term used in the Hyakujō Shin-gi [百丈清規] (the first Chinese treatise that mentions the drinking of matcha, and which some scholars claim -- apparently ignorant of the actual contents of this book -- is the origin of chanoyu): this work sets out the set of monastery regulations (including those related to the drinking of tea by the monks on special occasions, such as the Emperor's birthday*) said to have been proposed by the great Chán master Baizhang Huaihai [百丈懐海; 720 ~ 814] (his name is pronounced Hyakujō Ekai in Japanese). __________ *Tea apparently was given to the monks as a sort of treat -- though it was prepared for them by the kitchen staff who set up a table behind the altar in the Buddha Hall of the temple, bringing a pitcher of hot water from the kitchen for this purpose. The book details how the monks rise from their seats and proceed to enter the space behind the altar from one side, where they drink their tea perfunctorily, and then return to their seats by emerging from the other side. There are no rules about how the tea is made -- though apparently this was done assembly-line style, in the same way that food was given to them in the dining hall -- nor is anything said about how it is to be drunk.

Drinking matcha does not mean -- and must not be equated with -- chanoyu, except for those people who wish to predate the appearance of chanoyu in Japan to some point before 1403 (which is when the practice was introduced to the court of the shōgun by the nobles escaping from the collapsing Koryeo dynasty).

⁸These things are (in back, from right to left) a candlestick, a kyōji-tate [香筋建] (a vase-like container for the implements used when placing incense into the censer), and a flower vase; and (in front) a kōgō [香合] (incense container).

⁹See footnote 8 in the part of the previous post dedicated to the Kun-dai Kan Sa-u Chō Ki [君臺觀左右帳記] for a discussion of the ukai-chawan [迂回茶碗].

¹⁰Hō-bon ni nose [方盆ニ載]. This sentence seems to have been miscopied here. The pair of ukai-chawan are placed on a square (or rectangular) tray, not the jikirō. This sketch reproduces one found in the Kun-dai Kan Sa-u Chō Ki.

¹¹Kenzan mutsu kaku-dai ni suwaru [建山六ツ各臺ニスハル]. The first word in this phrase is Kenzan [建盞], which means sakazuki [盞] (conical cups for drinking heated “rice-wine”) from Fujian (abbreviated Ken [建]). The kanji san [山] should be understood as a hentai-gana (for the sound san/zan).

¹²Juro-no-habōki [ジユロノ羽ホウキ]. Juro [棕櫚] is the hemp-palm, and in the modern tea world, one version of the broom used to sweep the roji is made from several dried palm fronds tied to a handle of green bamboo (this kind of broom is called a juro-bōki [棕櫚箒]).

Juro-no-habōki could either mean that the habōki is made from a dried palm frond that has been trimmed and combed into fibers (possibly the kanji ha [羽] was added by mistake when the sketch was copied); or, possibility this means a habōki made not from one or three feathers, like nowadays, but from the entire wing of a small bird. Today this kind of habōki (which is usually made from the wing of a swan or crane) is usually known as a haki-komi [掃込]: this kind of feather-duster resembles a broom made from a dried palm frond. In Furuta Sōshitsu’s writings, however, it seems that a smaller version was still being used as a temae-habōki in his day.

In Nōami's sketch, the “juro-no-habōki” looks like a small haki-komi (though whether it was actually made from a hemp-palm frond, or from the wing of a bird, is not specified -- and the kaki-ire stating the name is missing).

¹³Hi-kaki [火カキ = 火掻き] is a sort of spoon-shaped fire-iron used to rake the ashes in the furo. Once again, since the kama on the o-chanoyu-dana was kept boiling all day, as the charcoal burned down the ashes would have to be raked flat so that fresh fuel could be added, and this is the implement that was used.

The hi-kaki seems to have been a combination of a hai-saji [灰匙] and a soko-tori [底取] (while modern furo-yō soko-tori [風爐用底取] is shaped like a shallow soup ladle, Rikyū's soko-tori was shaped like a large hai-saji). In Nōami's sketch, the hi-kaki resembles a large hai-saji.

¹⁴The source of the sketches is a manuscript that was passed down in the Imai family, and probably hand-copied by a member of that house. (Sōami's original is not known to exist.) Since the Imai family was prominent among the teamen of the sixteenth century, it seems likely that, when confronted by sketches of things that did not really make sense, they were interpreted through the eyes of a machi-shū chajin. This could also account for the similarity of the juno-no-habōki with an ordinary temae-habōki.

¹⁵The placement of the sumi-tori on the right, and the koboshi on the left may be an anachronistic emendation. Neither of these things are shown in Nōami's sketch.

¹⁶Note that the original sketch extends across two pages in the Imai manuscript (which was copied into a notebook), with a break in the middle. I have digitally removed the space that separated the two halves of the sketch from each other so that the sketch now resembles the presumed original (which was most likely written on a horizontal roll of paper).

¹⁷The modern equivalent, called mikuji [御籤, or 神鬮], are small strips of paper bought at Shintō shrines, with a fortune written on them. They are usually sold from a vending machine.

In the Chinese practice, however, the tube containing the bamboo strips (which are known as qiān [籤]*) was held almost horizontally by the querent and shaken until one slip falls out, thereby revealing the answer to the user's question. __________ *While it seems that in ancient times a brief augury was written on each bamboo slip, more recently each of the slips is numbered, the number pointing to a specific text recorded in a book of prognostications (the statements are usually ambiguous -- often in verse -- and generally require the help of an expert to relate the meaning to the specific question that was asked).

This form of divination is known as Qiú-qiān [求籤] in Chinese. The qiān-tong [簽筒] (the tube out of which the bamboo slip is shaken) is equivalent to what Sōami calls the kuji-zutsu [鬮筒] here.

¹⁸This vessel is called a kyōji-tate [香筋建] today.

A kō-saji [香匙] is a long-handled spoon used to pick up pieces of incense wood, when moving them from the cutting block to the kō-zutsumi [香包み] (a small cloth envelope lined with gilt paper), which is, in turn, put inside the kōgō. The kyōji [香筋, or 香箸] (ebony chopsticks) are used when transferring the incense wood from the kō-zutsumi into the kōro.

The idea is that the incense wood should never be touched with the fingers -- since the skin oils could effect the smell of the incense.

In the sketch, the kō-saji and kyōji are shown standing in the kō-saji dai (kyōji-tate).

¹⁹Sui-bin [水瓶]. This kanji compound can also be pronounced mizu-kame.

²⁰Hana tatsu-beshi [花立ヘシ]: a flower should be stood [in the sui-bin] -- perhaps so that the guests do not mistakenly suppose the water is a refreshment, and drink it.

²¹These were imported bronze pieces, usually from China, and probably antiques. Though they could be used for looking at oneself, the primary purpose here is decorative. This is what the kaki-ire implies.

²²Perhaps a miscopying. The objects are to be centered, front to back and side to side, on the surface of the writing desk.

²³Inrō chūseki [印籠 鍮鉐] means an inrō (a set of boxes in which carved name-seals and seal-ink were kept), made from chūseki [鍮鉐], which seems to be the kind of brass produced in Mogul India. Thus, a set of stacking brass boxes imported from India (probably via China or Southeast Asia), that were used as an inrō in Japan.

Chūseki is usually known as ōdō [黄銅] today, and the classical term has been lost from the East Asian languages.

²⁴Kyūrō ・ mawari-kōro ・ dai ni suwaru [毬籠 ・ マハリカウロ ・ 臺ニスハル].

A kyūrō [毬籠] would be a kind of hanging incense burner, made of openwork metal, usually made with a series of concentric brackets inside, attached to each other at 90°, and with a cup in the middle. The brackets allow the cup to remain upright even when the kyūrō is shaken by the breeze. A pinch of crushed incense wood was placed in the cup, and set to smoldering with a taper. This kind of censer was used to perfume the often fetid inner-city air blowing into the upper story windows from the street. Both Chinese and Mogul examples exist.

The word kyūrō, as it is written here, could also mean a basket in which a gauze bag of dry aromatics was kept, for the purpose of perfuming the air in the room. In either case, when not suspended from the ceiling, this kind of kōro could be provided with a base (as shown above*), allowing it to be placed on a shelf (as in sketch 6).

Mawari-kōro [マハリカウロ = 周り香爐] seems to mean a censer that is intended to perfume the air in the room (mawari [周り] means “in the vicinity”).

In addition to the more elaborate system explained above, which was intended to facilitate the burning of crushed incense wood, some commentators state that a cloth bag, in which a blend of aromatic herbs and fragrant wood chips were tied, was placed inside the censer, to perfume the air of the room passively (in other words, without the incense being burned), and over a long period of time†. The point here was to perfume the air of the room without the source of the fragrance being obvious.

Dai ni suwaru [臺ニスハル = 臺に座る] means that the kyūrō is sitting on a specially made stand (rather than being suspended from the ceiling, which was the other way such censers were displayed). In the sketch, the dai is not obvious: the word dai does not refer to the tray on which the kōro (resting on the dai) is displayed. ___________ *Though this dai was not always as elaborate as the one shown. Some resemble a downward-facing bottle-cap -- a metal ring that flares outward slightly at the bottom.

†While the use of such sachets (called kariroku [訶梨勒], an Edo period drawing of a rather modest example of which is shown below) had been known since the Heian period -- kariroku were often hung up to perfume the interior of the nobleman’s mi-chōdai [御帳臺] (an elevated platform usually covered with two tatami mats, with a cloth canopy above and curtains or reed blinds suspended around the four sides: it functioned as the nobleman’s seat of estate during the daytime, and as his bed at night) -- the sachets themselves were usually made of beautiful cloth, and adorned with exquisitely tied knots, and so were decorative objects in their own right.

In fact, have never seen any classical reference that mentions secreting these sachets inside of censors of the type that are under consideration here.

²⁵The original Chinese way of serving tea was for a scoop of matcha to be placed in the temmoku (resting on a dai). This was then held out while the servant poured in some hot water and whisked the usucha with a chasen.

This is the method of service that is mentioned (albeit briefly) in the Bǎizhàng Qīng-guī [百丈清規] (Hyakujō Shin-gi, in Japanese -- which is also mentioned in footnote 7, above), and employed in the Kennin-ji yotsu-gashira-shiki sarei [建仁寺 四頭式茶礼] (which is performed at the Kennin-ji in Kyōto every year on April 20th, the memorial day of Myō-an Eisai Zenji [明菴榮西禪師; 1141 ~ 1215]).

²⁶The kanji is hai [盃] (this kanji can also be pronounced sakazuki), which means a shallow, saucer-like vessel, usually made of lacquered wood, from which heated sake was drunk. This is a different word from san [盞] (which can also be read sakazuki), which means a conical ceramic cup (or “bowl”), also originally made for drinking hot sake. Sake, usually flavored with medicinal herbs, was a popular drink in both China and Korea in ancient times. Distilled spirits, of the sort we usually associate with those cultures today, did not appear until much later.

The hai, resting on a dai, must not be conflated with a temmoku resting on a dai (which some scholars apparently have done, on account of the yu-bin being displayed on the lower shelf). In general, the intention behind these arrangements seems to be to avoid anything that would resemble a smörgåsbord: the bronze pitcher used (in China) to serve tea is displayed together with a shallow saucer used to drink sake.

²⁷In this case, the word shōji [障子] refers to the sliding doors on the tana.

²⁸Because the bottom of classical bronze pieces had to be added after the piece was cast (they were cast as cylinders, with both ends open), the weld was not always completely watertight* (though pieces that leaked badly rarely made it to market). As a result, flower containers were placed on small trays, to prevent any leakage from damaging the shelf†. __________ *While considered great treasures in Japan, where the technology of bronze making was as yet unknown, it seems that most of these pieces were rather commonplace in their countries of origin (in both China and Korea, people of all classes worshiped their ancestors at least on certain occasions during the year, and, as this required a special set of implements, including flower vases and candlesticks, the range in prices was staggering -- and it was naturally items at the lower end of the spectrum that speculators bought for export to Japan, since the rarity of bronze of any sort in Japan meant that such things would yield the greatest profits). As a result, minor leaks would have been found from time to time -- and apparently often enough that taking the precaution of displaying the vase on a tray was deemed prudent.

†Many of the pieces employed as mizusashi in Japan were made as containers for the alcoholic beverages that were used for libations during ancestor-worship ceremonies, and these vessels were usually lined with lead during the production process (molten lead was poured into the finished vessel, and, after rotating the piece so as to coat all sides, the excess lead was poured out), to render them completely watertight.

It seems that a similar degree of care was not deemed necessary with respect to flower vases.

²⁹Probably a copying error.

In the O-kazari Sho [御飾書], this object is labeled as a jikirō [食籠], a lidded container for sweets and side-dishes that were served to accompany tea or sake.

It is unlikely that more than one chaki [茶器] would be displayed at the same time, and the famous Kaeri-bana [歸花] tea container is displayed on the shelf to the left.

³⁰In the Kun-dai Kan Sa-u Chō Ki this piece is referred to as the Kaeri-bana yakki [歸花藥器]*, and the sketch of this object (which was used as a tea container) is shown below. It seems to have been made of carved lacquer, and, while this point is not discussed in any of the classical writings, cinnabar lacquer (tsui-shu [堆朱]) seems more likely than black. Below the sketch from the O-kazari Ki is shown beside the kind of container that was described in that work (while this container and the tray on which it rests is referred to as a bon-kōgō today, this naturally does not preclude the likelihood of its having had a very different function in antiquity).

The word kaeri-bana (whether written “歸花,” or “反花”) means a flower that blooms out of season -- especially spring flowers (such as the cherry) that bloom in the late autumn or early winter, before the arrival of the intensely cold weather†. The reason why this container (which is a stylized lotus blossom, with the carpellary receptacle at the top, and several rows of petals below) was given this name is not explained in any of the classical sources. __________ *The name was also written Kaeri-bana yakki [反花藥器]; and sometimes the phonetic rendering sori-bana [ソリハナ] is found (in place of kaeri-bana) in the old writings.

†Flowers that bloom later the same year, after the season is past (especially, cherry-blossoms blooming in early summer), are usually referred to as yoka [餘花 -- usually written 余花 today].

³¹Kantō-mizuhiki kakaru [カンタウノ水ヒキカヽル]* is a miscopying for Kantan-mizuhiki kakaru [カンタンノ水ヒキカヽル], which means "a mizu-hiki (a Chinese-style valance made of heavily embroidered cloth that kept rain water from blowing in through the transom windows) from Hándān [邯鄲] (pronounced Kantan in Japanese)† is hung up."

Today the word mizuhiki [水引] refers to the red-and-white‡ (or black-and-white**) paper cords tied around gifts and gift-envelopes; and, less commonly, to Persicaria filiformis, a wildflower with long racemes of tiny red or white flowers (that poetically resemble dew-drops scattered along the stem). These usages have no connection with the present entry -- though they appear to have confused a number of scholars. __________ *Kantō [カンタウ] has been interpreted by certain scholars to be kantō [漢渡], “crossing over from China” (though the more natural interpretation, kantō [韓渡], meaning “crossing over from Korea,” is patently ignored), in the same way that the generic name for stripped cloth is generally understood to imply a Chinese origin for these textiles. In fact, there is no historical evidence for such usage prior to the sixteenth century (where a Korean origin seems to have been understood) or later (when the implied source was supposed to be China).

†Hándān [邯鄲] remains a major city in Héběi [河北] province, and was the capital of the State of Zhào [趙] during the Warring States period (c 475 BC ~ c 249 BC) of Chinese history.

In Japanese, kantan [邯鄲] is also the name of the tree cricket (Oecanthus longicauda), but this meaning is irrelevant here.

‡Used on felicitous occasions -- New Years, O-bon, birthdays, weddings, and so forth..

**Used on sad occasions, such as funerals.

³²Hone-haki ittsui [骨吐一對] literally means “a pair of [containers for] spitting-out bones” (or, perhaps, “a pair of spittoons”), and such receptacles were probably used for such a purpose on the continent. In Japan, however, they were used as decorative pieces (the pair in question were made of tsui-kō [堆紅]*).

Smaller (and simpler) versions were used as mizu-koboshi (Rikyū's mon-sasu koboshi [モンサスコホシ] was a low-fired pottery version of this kind of container). __________ *These hone-haki are described as tsui-kō horimono [堆紅彫物], carved objects of tsui-kō.

Tsui-kō [堆紅] is one of several Chinese varieties of carved lacquer. In this case, thick layers of black and cinnabar lacquer are applied alternately, with the final layer being cinnabar. The carving is done through the layers, and while this presents a striped effect when viewed close up, from a distance it darkens the carving dramatically (without making the decoration appear to be a solid black, and so look painted-on).

³³This basket-like hanging incense burner is recorded to have been made of silver. While it is possible that crushed incense wood was burned in a cup in this type of censer as well, this one more likely contained a kariroku [訶梨勒], a blend of dried aromatic plants tied in a gauze bag, intended to perfume the air in the manner known as sora-daki [空薫] -- “without revealing the source of the fragrance.”

As mentioned above, the idea of burning incense in the window well came from the continent (this usage was known from both India and China), where opening the windows on the upper stories in the densely populated urban areas would let in fetid air, which the incense was intended to mask (while still letting in the cooling breezes).

³⁴This mirror featured a bas relief of what was said to be the Dōjaku-dai [銅雀臺] (“Bronze Sparrow Terrace”), the legendary mansion of the great Chinese military strategist Cao Cao [曹操; c 155 ~ 220] of the Three Kingdoms Period (Sānguó Shídài [三國時代], c 220 ~ 280 AD).

The type of mirror in question is shown on the right, while the scene was probably similar to the painting (of the same Tóng què tái [銅雀臺]) on the left.

³⁵A jin-bako [沈箱] is a box in which a selection of pieces of incense wood was kept: rectangular boxes, such as the one shown in this sketch, are said to have had six small compartments inside, while round boxes typically had seven (arranged like six petals around the center). The incense, previously cut into pieces of a size suitable for burning in a kiki-kōro [聞き香爐] (a hand-held censer used for sniffing incense), would have been kept in small kō-zutsumi [香包み] (envelopes made of donsu cloth backed by gilded paper -- the gilding helping to keep the volatile components inside the envelope, so that the different varieties of incense would not contaminate each other).

The present box was made of tsui-kō [堆紅], a variety of carved lacquer where the piece was coated with alternating layers of cinnabar and black lacquer, with the final coat being red*. Carving through the lacquer revealed a striped pattern. __________ *When the final coat was black, the lacquer is referred to as tsui-u [堆烏]. Both types were popular during the Ming period.

³⁶San-shoku bon ni suwaru [三色盆ニスハル]. Shoku [色] -- which literally means “color” -- was used as a counting word, in the classical period, to subdivide collections of similar things into groups. Here, all three objects are utensils that are used when appreciating incense: that is their common identity.

In Book One of the Nampō Roku, the expression is used to differentiate flowers into their two logical groups -- herbaceous flowers (which bloom near the ground), and the flowers of trees (which bloom above eye-level).

I am mentioning this once again here because it seems many Japanese scholars take the word shoku literally, and try to make it mean “colors.”

In the present instance this would clearly be nonsensical; but in the example in Book One, doing so leads to the enunciation of a false teaching -- that only one or two colors of flowers are permitted in the tearoom at the same time (what Rikyū was actually saying there is that, in the small room, only one type of flower -- herbaceous flowers*, or flowers cut from trees† -- should be used; but when the room is increased to 4.5 mats, then both herbaceous and the flowers from trees may be used together in the same arrangement, as they always are in the formal rikka [立華] arrangements, which he was using as his precedent). __________ *Herbaceous flowers, which naturally bloom near to the ground, should (according to him) be arranged in a vase standing on the floor of the tokonoma.

†Because the flowers of trees are encountered above eye-level in nature, the look most natural when arranged in a vase hung on the hook nailed into the back wall of the toko. Indeed, according to the poem written by Jōō (and later modified by Rikyū) the height of this hook is decided upon relative to the height of the guests' eyes when they are seated appropriately in front of the tokonoma -- so that the flowers arranged in the hanging vase will be slightly above their eye level. In this way they will look natural, since they will be seen in exactly the same way that one would encounter them in nature.

³⁷Chaki oite [茶器置]. This is another instance of miscopying. The word given as chaki [茶器] should be yakki [藥器], which, in this case, means a (decorative) medicine case.

The person who made this copy was clearly a chajin, and the result is that he saw references to tea and tea utensils even in places where they were not to intended.

³⁸O-shōji no e [御障子の繪]. Shōji here refers to the pair of sliding doors that enclose the ji-fukuro, below the chigai-dana.

According to one source, the last word is sumi-e [墨繪], meaning a painting in black ink only. It seems that many of these doors were covered with antique paintings from the shōgun's collection of imported works. Perhaps these were from scrolls that had been damaged, with the ruined parts cut away, and the remainder used for purposes such as this.

³⁹Moro-kazari [もろかさり = 諸飾り]. While the tea schools have modified the meaning of this expression to a certain extent, it originally signified the arrangement of the full set of implements* -- an incense burner, a pair of vases, and a pair of candlesticks -- on a table that was placed in front of the triptych.

This was done only for the most formal of receptions, however. On more ordinary occasions, the things displayed on the joku [卓] were reduced in number to what is referred to as the mitsu-gusoku [三具足] -- one flower vase, one candlestick, and the censer. ___________ *In addition to the things mentioned above, a kōsaji-dai [香匙臺] and a kōgō [香合] have been added to the standard set.

⁴⁰Shō-gwan [しやうくわん] is the actual sound that is rendered phonetically here. In the modern language, the sound has been contracted to shōgan [賞翫].

The word shōgan means appreciation, admiration, and enjoyment (in the sense of enjoying the honor of receiving a visit from ones lord).

⁴¹The objects on the table in front of the oshi-ita should be arranged as was shown in sketch 3, “the ordinary way to arrange the oshi-ita when a triptych is hung” -- which is a simplified version of the full arrangement shown in sketch 12. The fact that this sketch was included at the end of the manuscript, almost as an afterthought, suggests that the full arrangement was secret, and to be used only on the rarest of occasions.

It is worthy of note that this sketch was moved to the very front of the work when it was prepared for the officials in charge of the arrangement of the Tokugawa shōgun’s shoin. That version of Soami’s work is what has come to be known as the O-kazari Sho [御飾書] -- and its sketches will be considered (in reference to the O-kazari Ki) next.

⁴²Kono soto ni ittsui hana waki ni aru-beshi [此外に一對花わきにあるへし]. This refers to the pair of flower arrangements (the vases are seen in sketch 3) that are placed (on their own stands) on the right and left of the central table. The left and right arrangements were formal rikka [立華], while those on the central table were simpler (in keeping with the smaller size of their vases, and the confines of the table itself -- these smaller arrangements should not project beyond the edges of the table on which the vases stand).

==============================================

◎ O-kazari Sho [御飾書], while also ascribed to Sōami, seems to be an Edo period revision, intended to relate this material more specifically to the arrangement of the various shoin within the Tokugawa shōgun’s residence in Edo. As such, the order of the material has been changed, to a certain extent, while extraneous comments have also been interpolated from time to time¹.

1) The first sketch has been transposed from the end of the O-kazari Ki, to the beginning of the O-kazari Sho (indeed, it has been placed in the middle of the enumeration of the various utensils that were displayed in the shoin, being found between illustrations of the various hai-gata appropriate for the kōro, and an illustrated list of the different shapes of the classical chaire). The text of the kaki-ire that explains the use of this arrangement (see the commentary under sketch 12 in the O-kazari Ki) has been clarified, so as to avoid any confusion².

Notice, however, that the positions of the candlesticks and flower vases have been reversed from what was shown in the O-kazari Ki.

2) This plate corresponds to sketch 1 in the O-kazari Ki. The commentary repeats the material translated under that entry.

3) This plate is not found in either the O-kazari Ki, or the Kun-dai Kan Sa-u Chō Ki.

The kaki-ire appended to this sketch reads: joku no ma mo joku no ma mo yoku sun wo torite onaji hodo oku-beshi [卓の間も卓の間もよく寸をとりて同ほとに置くへし], which seems to mean “the space between the table (and the wall?), as well as between the table (and the other wall?), should be carefully noted, so that (the table) will be placed (in such a way) that these are approximately the same.” This would seem to mean that the space between the table and the wall at the rear of the oshi-ita (which is fixed, based on the depth of the oshi-ita, since the joku should be centered between the rear wall and the front edge of the alcove), and between the table and the side wall, should be essentially equal.

Though this is also the text found in the Higashiyama-dono O-kazari Sho [東山殿御飾書] (which manuscript is dated 1762, and appears to have been copied from the original document that was preserved in the shōgun's household), some scholars have suggested that the second phrase should be habikori no ma mo [衍の間も], which would then mean “the space between the table (and the wall)³, and the extent to which (the arrangement) spreads beyond (the table) should be taken note of, so that these are approximately the same.”

4) Though dissociated from the picture of the dashi-fuzukue, this plate shows the arrangement of the chigai-dana found in sketch 5 of the O-kazari Ki. There, however, seem to be several anomalies here: the objects displayed on the tray (on the upper shelf of the chigai-dana) are labeled (from the right) kōsaji・hi-saji [香匙・火匙] (these are placed together in the vase-like holder, but it is not clear what a hi-saji might be -- the original showed a kōsaji [香匙] and a pair of kyōji [香筋], ebony chopsticks, in what Soami described as a kosaji-dai [香匙臺]), kōro [かうろ・香炉] (the name is written phonetically and then with kanji), and a kiku-kōro [きく・聞香炉] (the kana kiku are written as furigana; though this object is usually called a kiki-kōro [聞き香炉]). However, the biggest problem is with the utensil in the middle: in the original, this is a kōgō [香合], not a koro [香炉]. Below the upper shelf, the word bon・kata-bon [ぼん・かた盆] (with the kana bon [ぼん] as furigana showing the pronunciation of the kanji “盆”) is also confusing. A kata-bon [方盆] is a square (or possibly rectangular) tray; but the only tray shown inthe sketch (on the upper shelf) seems to be round.

5) Here is the o-chanoyu-dana, as in sketch 4 of the O-kazari Ki. However, in addition to the various things shown in the earlier work, a number of other objects have been added below the tana. From the right, these are: hai-tori [灰取] (perhaps a sort of haiki [灰器]?), o-tefuki [御手拭] (a towel rack), Nara kami [奈良紙] (Nara paper), sumi-tori [すみとり], hō-no-mono [はうの物] (unknown), mizu-koboshi [水こほし], hansō te-arai [はんさう手洗] (unknown).

In this sketch, the habōki is made from the wing of a bird.

6) This plate corresponds to sketches 6 and 7 in the O-kazari Ki.-- though in the O-kazari Ki (and those versions of the O-kazari Sho where they are separate⁴) there is nothing that indicates that the two chigai-dana were connected in the way shown here.

That aside, the notations all agree with what are found in the earlier source.

7) In the O-kazari Ki, this plate is included as sketch 8. The name of the object on the right side of the middle shelf is generally interpreted to be kagami-ya [鏡家], the meaning of which is unclear⁵. The other notations either conform with, or elaborate upon, what is believed to have been the contents of Sōami’s original (as mentioned previously, that document has been lost, and the oldest surviving manuscript copy contains a number of copying errors, one of which is present in that version of this illustration⁶).

8) This plate corresponds to sketch 9 in the O-kazari Ki. The details are all in agreement between these two sources (though in this sketch, the pair of hone-haki [骨吐] are not identified as being tsui-kō horimono [堆紅彫物] -- made of tsui-kō carved lacquer) .

9) This illustration agrees, in all of its particulars, with sketch 10 in the O-kazari Ki. It is a sketch of one arrangement for the tsuke-shoin.

10) This plate is almost identical with sketch 11 in the O-kazari Ki. The difference is that while the O-kazari Ki shows a rectangular jin-bako [沈���] (which had six compartments for different varieties of incense wood), the O-kazari Sho features a round jin-bako, which had compartments for seven varieties. Nevertheless, both are described as being made from tsui-kō [堆紅] (carved red and black lacquer).

_________________________

¹I will ignore all of this superfluous material, since it postdates the things covered in Book Four of the Nampō Roku by half a century and more.

²It appears that the officials who prepared the O-kazari Sho had access to Sōami’s original manuscript. Therefore they were able to correct many of the miscopyings that are found throughout the oldest surviving manuscript of the O-kazari Ki (which was not made by Sōami himself).

³Joku no ma mo [卓の間も] can also mean “within (the confines) of the table” -- in other words, the amount (or volume) of the table’s surface that is covered by the flower arrangement, or the mass of the arrangement above the table.

If this is what was intended, then the revised version joku no ma mo habikori no ma mo yoku sun wo torite onaji hodo oku-beshi [卓の間も衍の間も よく寸をとりて同ほとに置くへし] would translate “the space above the table that is covered (by the arrangement), and the extent to which the arrangement spreads beyond the table, should both be observed, and (the vase) should be placed (on the table) so that they are essentially the same."

⁴The two sketches are joined together in the Higashiyama-dono O-kazari Sho, suggesting that there was some basis for doing so (since the Higashiyama-dono O-kazari Sho seems to have been copied directly from the original manuscript that was preserved in the shōgun’s household).

⁵In the O-kazari Ki, this object is labeled kagami [鏡], which means a mirror.

In the Higashiyama-dono O-kazari Sho (the relevant sketch from which source is reproduced above), however, it appears to be labeled hikiya [挽家], which would mean the storage box for a chaire (made either of turned wood, or turned ivory, to match the shape of the chaire exactly on the inside). The problem is that hikiya seem to date from a later period than the material contained in these books.

⁶The object on the lower right side is erroneously labeled as a chaki [茶器] in the Imai copy of the O-kazari Ki; but is, in reality, a jikirō [食籠] (a box for the sweets or side-dishes traditionally served to accompany tea or sake).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some sort of Christmas Present thingy (I guess?)

If you’ve checked my blog these days then you might have seen my proposal. Since the Christmas spirit is slowly taking over me, I decided to take on one translation request, winner generated through random number generator. (It ended up more with tsukiuta than tsukipro, but please read the rules for tsukipro)

You can look up this list below read more, choose one item you want me to translate and send me that through ask. The limit date is 20th of December!

Before that, here are a few rules:

You can send only one ask (please don’t try to cheat using anon ask, I left that available for those who want to participate but don’t have tumblr accounts)

You can send the ask either directly or as anon (but respect rule 1 and send only one ask)

You can select one thing from the list or send me a title of your own if it’s not listed below and it’s not translated by someone else (I didn’t really add tsukipro CDs since I don’t really know which were translated, but I have a slightly idea)

I tried not to add things that were translated before, but if I did end up doing that please let me know and I’ll remove it from the list

For now I’m decided on only one winner, but if there are more than let’s say hmmm 35 requests? I’ll choose 3 winners

Feel free to ask me any questions about it

No, I won’t share the CDs or scans

Might add more rules as time passs?

Now here’s the list (sorry I gave up on naming them like halfway)

Tsukiuta 2nd season (duet CDs)

>Tsukiutaya shop smartphone case short story tokuten:

-Datte Mada Mada Avant-Title -Koi Wasuregusa -Inocencia -Hajimari no Haru -Rainy Day -Tsuki to, Hoshi to, Maboroshi to -Childish flower -Kimi ni Hana wo, Kimi ni Hoshi wo -DA KAI -Awai Hana -Sing Together Forever -Celestite

>Tsukiutaya shop bag short story tokuten:

-Datte Mada Mada Avant-Title -Koi Wasuregusa -Inocencia -Hajimari no Haru -Rainy Day -Tsuki to, Hoshi to, Maboroshi to -Childish flower -Kimi ni Hana wo, Kimi ni Hoshi wo -DA KAI -Awai Hana -Sing Together Forever -Celestite

>Tsukiutaya shop pouch short story tokuten: -Datte Mada Mada Avant-Title -Koi Wasuregusa -Inocencia -Hajimari no Haru -Rainy Day -Tsuki to, Hoshi to, Maboroshi to -Childish flower -Kimi ni Hana wo, Kimi ni Hoshi wo -DA KAI -Awai Hana -Sing Together Forever -Celestite

Tsukiuta 3rd Season:

- Kisaragi Koi [Radical Lovecal] Mini Drama (ft. Iku)

- Kannaduki Iku [Lost My God] Mini Drama (ft. Koi)

- Joint Live Intermission: Kakeru & Rui's MC corner

- Joint Live Intermission: Haru & Kai's MC corner

- Joint Live Intermission: Arata & You's MC corner

- Joint Live Intermission: Aoi & Yoru's MC corner

- Joint Live Intermission: Koi & Iku's MC corner

- Tokuten for buying all 12 volumes: Joint live's backstage entrance

Tsukiuta Female Solo 2nd Series:

- Momosaki Hina [Kono Koneko no Ko] Drama Part

- Terase Yuno [My Longing] Drama Part

- Motomiya Matsuri [Tawamure Hayashi ni Koikogare] Drama Part

- Asagiri Akane [Sepia] Drama Part

- Tokuten for buying all 12 volumes: Girls' live backstage ~Let's have lunch!~

Unit Singles:

- Six Gravity Unit Song [Gravity] Short Story paper

- Procellarum Unit Song [ONE CHANCE] Short Story paper

- Interlocked Purchase Short Story paper "After a certain live is over" (ft all 12)

Anikuji (CDs):

-Six Gravity Anikuji B-1 Award: Hajime & Haru

-Six Gravity Anikuji B-2 Award: Arata & Aoi

-Six Gravity Anikuji B-3 Award: Kakeru & Koi

-Six Gravity Anikuji B-4 Award: Hajime & Arata

-Six Gravity Anikuji B-5 Award: Aoi & Kakeru

-Six Gravity Anikuji B-6 Award: Haru & Koi

-Procellarum Anikuji B-1 Award: Shun & Kai

-Procellarum Anikuji B-2 Award: You & Yoru

-Procellarum Anikuji B-3 Award: Rui & Iku

-Procellarum Anikuji B-4 Award: Shun & You

-Procellarum Anikuji B-5 Award: Kai & Rui

-Procellarum Anikuji B-6 Award: Yoru & Iku

Other CDs:

- Tsukiuta Ikebukuro Tsukineko Monogatari

- Uduki Arata's Rabbit Fair: "Tsukiuta in Wonderland" Special Tokuten Drama CD

- Tsukiuta Koi & Arata's tokuten Tsukiraji Bussiness Trip Edition

- Tsukiuta Tsukipro Festa in Stuffing Oshi things (ive no idea how to word this lol)

- Tsukiutaya Shop antenashop kaiten kinen manezu eigyou tour ☆ tennai housou CD

- Tsukiuta nenmatsu jump kuji D-Award " AGF 2014 Tsukiutaya Naration CD"

Books:

>Super comic city 25 Charity Book: Kimi ni hana o ageyou (this on features tsukipro characters too)

> Tsukitomo Animate Set Booklet

> Monthly Tsukiuta 2014 Special Edition:

-One year anniversary roundtable discussion: Seniors ver

-One year anniversary roundtable discussion: Middle group ver

-One year anniversary roundtable discussion: Juniors ver

-Cast Interview: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12

- Goddesses talk

- Tsukiuta diagram 12-5 Men + Women

- Interview with Jiku-sensei

- January & February interview (about their songs): Men + Women

- Dorms plans ft March representants

- Tsukiuta diagram 1-12 Men

- More interviews with staff members

> [AGF 2014] Monthly Tsukiuta 2014 Special Edition:

-Two years anniversary roundtable discussion: Seniors ver -Two years anniversary roundtable discussion: Middle Group ver -Two years anniversary roundtable discussion: Juniors ver -Cast Interview (Men ver): 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12 -Cast Interview (Female ver): 1-12 - Christmas talk between the juniors - Christmas talk between Gravi, Procella and Fluna - Festival of seven herbs discussion ft Middle group -Adult day (?) discussion ft seniors - Tsukiuta Poll (men & women) // basically top lists for stuffs like "who do you want to have as you boyfriend/girlfriend etc - To you who meets us for the first time (convo ft juniors) - To you who meets us for the first time (convo ft middle group) - To you who meets us for the first time (convo ft seniors)

>Tsukiuta Summer Holiday (Diary with one entry for each day)

>Tsukipro Dark Stew short story booklet

>Tsukipro Dark Stew 2 short story booklet > [Focus] Solids Fanbook (for this prob interviews) > TSUKIPRO SHOP in HARAJUKU Item Line-up SEXY☆SENSE mini story paper > TSUKIPRO SHOP in HARAJUKU Item Line-up Tokyo Love Junky mini story paper

Solids:

>Character Songs:

- Vol.1 Animate ss paper ft shiki

-Vol.2 Animate ss paper ft Rikka

-Vol.4 Animate ss paper ft Dai

Growth:

>Kachoufuugetsu

- Tokuten for buying all 4 volumes (mini drama CD)

SOARA:

>Kachoufuugetsu

- Tokuten for buying all 4 volumes (mini drama CD)

Magazines:

MY☆STAR Vol.3 -Cross Talk (Gravi & Procella) -Question for leader (Hajime & Shun + Kai & Haru) -More questions (Junios/Middle Group) -SolidS interview -Growth interview -SOARA interview

MY☆STAR Vol.8 - Love song for you - Special Interview (Arata, Aoi, You, Yoru) - Let's Sing a love song!! SolidS side - Let's Sing a love song!! QUELL side - Let's Sing a love song!! SOARA side - Let's Sing a love song!! Growth side

Dengeki Girl's Style (October 2015 issue) - Tsukiuta 3rd Season Kisaragi Koi [Radical Lovecal] - Interview with Koi's voice actor, Masuda Toshiki - Tsukiuta 3rd Season Kannaduki Iku [Lost My God] - Interview with Iku's voice actor, Ono Kensho

Dengeki Girl's Style (November 2015 issue) - Tsukiuta 3rd Season Satsuki Aoi [Harukaze to Hibari] - Interview with Aoi's voice actor, KENN - Tsukiuta 3rd Season Nagatsuki Yoru [Yuuyake Days] - Interview with Yoru's voice actor, Kondo Takashi

Dengeki Girl's Style (December 2015 issue) - Tsukiuta 3rd Season Mutsuki Hajime [Aa. Kami wo Nadete, Hoho wo Nadete, Omae wo Aishite yaru] - Interview with Hajime's voice actor, Toriumi Kousuke - Tsukiuta 3rd Season Shimotsuki Shun [Monochrome Sky] - Interview with Shun's voice actor, Kimura Ryohei

#personal#signal boost#my translations#christmas thingy#i actually have more stuffs but these are the only ones that can be translated#like for example i have tsukiani booklets but i can't really translate those

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog Post Translation: December 6th, 2020: 705* A Blog Where I Talk All About the #AllSailorMoonBigPoll

Enjoy, and please don’t repost without credit!

Yaa This is Satoyoshi Utano

Thank you very much for the comments and likes yesterday as well! * I read all of them

Everyone! Did you watch "IPPON Grand Prix"?? <3

Ahh~ I was nervous!! Lolololol

But, it was super, super fun~!!! <3 :) <3

So!!

GTF Green Challenge Day Thank you very much for the two days!!!

Under the sun! It was a really comfortable way to particpiate in the event *****

This time, I sang "Boys Be Ambitious!" with Kiyono Momohime-chan and Hirai Miyo-chan <3 <3 <3

Isn't that a rare grouping? <3 :) <3

Sincing on a long was an experience I've never had before...... it was a fresh feeling

And! I participated in a talk show with Okamura Minami-chan *

I really learned a lot, and I thought that that's still a lot of things that I'd like to be able to do

Also, also!!

Miimi said to me that she wanted to do a picnic since it was an event on the lawn! And she brought me handmade sandwiches T_T T_T T_T T_T T_T T_T <3 <3 <3 <3 <3 <3 <3 <3 <3 <3 She was so cute I cried

And, it was really delicious...... <3 <3 <3 <3 <3 <3 <3 <3 <3 <3

Everyone was able to comfortably sit on seats and enjoy the rich in nature Shinjuku National Garden <3

Everyone, Things like warm share and cool choice, Please try to incorporate eco-friendly activities into your daily life, okay

So!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Are there people who saw the "All Sailor Moon Anime Big Vote"......? *****

Yesterday, I was watching the "IPPON Grand Prix" with my family so, I watched the recording......

I really, really felt once again that it's a great work It's a wonderful special and just the best, the best (my vocabulary)

In the character poll, Sailor Uranus is number one!!!!!! T_T T_T T_T T_T T_T <3

My oshi, Michiru-san is 8, And Sailor Neptune is 14!!! <3

(Before, in the Ichiban Kuji, I got the Michiru-san goods <3)

Like this, it'll become harder to get UraNep goods again...... They're wonderful so there's nothing I can do about it

I will eternally admire Michiru-san. I want to be a beautiful, strong, and loving person like Michiru-san!

Right, right I love the moment when the outer senshi apply lipstick in their transformation scene, because it's just so beautiful......!

For the villains, I like Mistress 9 Black Lady Fish Eye-chan (my taste is easy to understand)

Fish Eye-chan is 11!!!!

Black Lady was also in the top and Mistress 9 is 49!!

I thought that I'd like to see a villains only poll lolol *

You know, today, I've been listening to "Bishoujo Senshi Sailor Moon Best" on a loop forever for the whole day......

The song voting was also passionate...... ****

However, since this has already become long, I'm thinking that tomorrow I'll do a "music edition" but, Is that okay? Is it fine to talk about Sailor Moon on my blog for two days in a row?

Even though I said that, tomorrow, I'll send you the music eidition (?)

Anyway, today, I recommend "Rashiku Ishimashou"!!!!! I love that song too much

There's a subscription where you can listen to "Bishoujo Senshi Sailor Moon Best", so please definitely listen to it!!!!!!!!

It might be different if you come check out tomorrow's blog after listening to it......!!

So, What can I say after the live recording......

I'm glad I'm alive

Being able to listen to Mitsuishi Kotono-san's version of the recording of the final episode...... What world line is this......?

I was so moved T_T

After all, I love how the Sailor Senshi are strong and beautiful, and they survive in their own ways. It grabs me.

They're drawn as normal girls but, All of the girls who appear are special, cute and beautiful girls. (Not just limited to the Sailor Senshi!)

I also want to be beautiful, cute and strong!!!

Hello! Project, Sailor Moon and PreCure are the textbooks for my life <3 I'll do my best to be the best girl

Satoyoshi Utano's first photobook "Utano Biyori"

Goes on sale on January 2nd, 2021!!

A New Year's present from Uu to everyone~ <3 :) <3 :) <3 LOL

If you preroder it until December 9th, you could win a book signed out to you

Check it out

Sailor Moon is an anime that came out before I was born, So I feel like I still have studying to do...... People who love Sailor Moon, please definitely tell me your favourite scenes and songs!!

If you are using a subscription to listen to Sailor Moon songs for the first time, please tell me which ones you think are good~!! <3 <3

Well then! I'll do my best tomorrow, too! Okay! <3

See ya!

0 notes

Text

#dr. stone#dcst#official media#official art#oshi kuji#dcst x oshi kuji#ishigami senku#asagiri gen#nanami ryusui#shishio tsukasa#chrome#saionji ukyo#hyoga#akatauki hyoga#anime#anime art#dr stone

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oshi no Ko - Kuji Luck featuring goods with new illustrations. Release: March 2024

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oshi no Ko - Taito Kuji Actors x Job featuring goods with new illustrations from 19 July 2024.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oshi no Ko - Kujibikido Kira Kira Summer Kuji featuring goods with new illustrations from 30 May to 27 June 2023. Release: Late-August 2023.

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oshi no Ko - Kuji Luck featuring goods with new illustrations. Release: March 2024

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oshi no Ko - Taito Kuji Sweet Sailor Style featuring goods with new illustrations. Release: November 2023

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oshi no Ko x Sanrio Characters Online Kuji from Kujibikido featuring goods with new illustrations available from 19 October to 16 November 2023. Release: Late-March 2024

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oshi no Ko - DMM Kuji featuring goods with new illustrations (Mem-cho's Buzz Fashion Course) available from 20 January 2024.

27 notes

·

View notes