#or the sibir khanates !!

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i hate writing for hetalia when i need to use other characters that either barely exist in canon or don't exist at all, so I have to make up names and personalities and looks and everything for them but also i don't want to get information wrong but also i don't wanna research for DAYS for this ONE scene and ahHHHHHHHHH

#like man i know nothing about Malta !!!#or the sibir khanates !!#but fuck i'd love to write about them !!#i need all the information in the world immediately right now#hetalia#but also history and life and language in general tbh#i wanna know it all

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

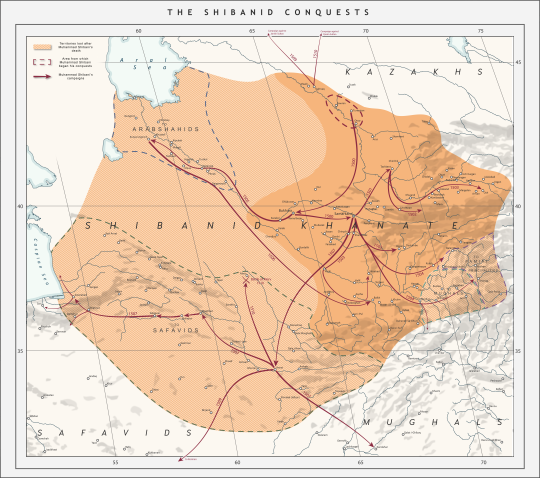

The Shibanid (Shaybanid) Conquests, 1500-1510.

by u/Swordrist

This is my attempt at covering an underapreciated area of history which gets next-to no coverage on the internet. Here's some historical context for those uneducated about the region's history:

Grandson of the former Uzbek Khan, Abulkhayr, Muhammad Shibani (or Shaybani) was a member of the clan labeled in modern historiography as the Abulkhayrids, who were one of the numerous tribes which were descended from Chingis Khan through Jochi's son, Shiban, hence the label 'Shibanid' which is used not only in relation to the Abulkhayrids who ruled over Bukhara but also for the Arabshahids, bitter rivals of the Abulkhayrids who would rule Khwaresm after Muhammad Shibani's death and for the ruling Shibanid dynasty of the Sibir Khanate.

After his grandfather's death in 1468, Shibani's father, Shah Budaq failed to maintain Abulkhayr's vast polity in the Dasht i-Qipchak, as the tribes elected instead the Arabshahid Yadigar Khan. Shah Budaq was killed by the Khan of Sibir and Shibani was forced to flee south to the Syr Darya region when the Kazakhs returned and proclaimed their leader, Janibek, Khan. Shibani became a mercenary, serving both the Timurid and their Moghul enemies in their wars over the eastern peripheries of Transoxiana. After the crushing defeat of the Timurid Sultan Ahmed Mirza, Shibani succeeded in attracting a significant following of Uzbeks which formed the powerbase from he launched his conquests.

Emerging from Sighnaq in 1499, Muhammad Shibani captured Bukhara and Samarkand in 1500. In the same year he defeated an attempt by Babur (founder of the Mughal Empire) to take Samarkand. Over the course of the next six years, Shibani and the Uzbek Sultans conquered Tashkent, Ferghana, Khwarezm and the mountainous Pamir and Badakhshan areas. In 1506, he crossed the Amu-Darya and captured Balkh. The Timurid Sultan of Herat, Husayn Bayqara moved against him however died en-route and his two squabbling sons were defeated and killed. The following year he crossed the Amu-Darya again, this time vanquishing the Timurids of Herat and Jam and subjugating the entirety of Khorasan east of Astarabad. In 1508, he raided as far south as Kerman and Kandahar, however he moved back North and launched two campaigns against the Kazakhs, but the third one launched in 1510 ended in his defeat and retreat to Samarkand at the hands of Qasim Sultan.

The Abulkhayrid conquests heralded a mass migration of over 300 000 Uzbeks to the settled regions of Central Asia from the Dasht i-Qipchak. They heralded the return of Chingissid political tradition and structures and the end of the Persianate Timurid polities which had dominated the region for the last century. It forever after changed the demographic of the region. His reign was also the last time Transoxiana was closely linked with Khorasan, as following the shiite Safavid conquests the divide between the two regions would grow into a permanent one.

In 1510, Shibani faced his end when he moved to face Ismail Safavid, who was making moves on Khorasan. Lacking the support of the Abulkhayrid Sultans, who blamed him for their defeat against the Kazakhs earlier that year, he faced Ismail anyway, where he was defeated, killed and turned into a drinking cup.

Shibani's death caused a complete reversal of the Abulkhayrid fortunes. Khorasan and the rest of his empire fell under Safavid dominion. However in Khwaresm, Sultan Budaq's old rivals the Arabshahids expelled the qizilbash and founded their own Khanate, based first in Urgench and then Khiva. In Transoxiana, Babur lost the support of the populace when he announced his conversion to Shiism and his loyalty to Shah Ismail, which allowed the Abulkhayrids to rally behind Shibani's nephew, Ubaydullah Khan and expel the Qizilbash. Nonetheless, the Abulkhayrids would never again hold as much power as they briefly did when led by Muhammad Shibani Khan.

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yermak's Conquest of Siberia (1895), by Vasily Surikov.

#history#military history#art#colonialism#russia#khanate of sibir#siberia#vasily surikov#yermak timofeyevich

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Siberian History (Part 6): The Time of Troubles

By the late 1500s, Russia was one of the largest nations on earth. Its many principalities had been united by stealth & force under the reign of Moscow, and now that the Khanates of Kazan & Astrakhan on the Volga River had been subjugated, Russia was now a multinational state.

From Ivan the Terrible onwards, the tsar claimed to rule by “divine right”. This was already common in Europe, but the Russian tsar's power was autocratic and absolute. One contemporary wrote about Ivan, “like Nebuchadnezzar, he slew, had beaten, elevated, or humbled whomsoever he wished.”

The state bureaucracy was growing, and near the top was the Boyar Dumar, the royal council made up mostly of men of noble birth. There was also an inner cabinet of councillors, whom the tsar could consult. But it was said of Ivan that he often did so “in the manner of Xerxes, the Persian Emperor, who assembled the Asian princes not so much to secure their advice...as to personally declare his will.”

Russia had a population of about 13 million people, mostly impoverished peasants who worked on large estates, or worked their garden-like plots in tiny hamlets across the land.

The old aristocracy had been humbled somewhat, and the service gentry had arisen to take its place. The difference between the two was that the old aristocracy inherited their titles & land by inheritance, whereas the service gentry were awarded estates for service to the tsar. However, the service gentry would eventually acquire many of the prerogatives of the aristocracy, including titles and inheritable estates.

Russia had no true middle class, independent merchant guilds, or any mercantile economy of the sort that was beginning to grow in many European countries. The gosts (“great merchants”) were appointed by the Crown. All offices & positions were in the employ of the state, i.e. “state service”.

Travel within Russia was restricted, and travel abroad was almost unknown, “that Russians might not learn of the free institutions that exist in foreign lands.” Police surveillance was widespread, and people had the “duty to denounce” – no matter what rank or standing people had, they had to politically inform on each other, and report whatever they knew or heard about disloyal acts or thoughts.

Punishments were harsh, and torture was common. People could be torn to pieces with iron hooks, beheaded or impaled, branded with red-hot irons, have their limbs cut off, or beaten with the knout. The “knout” was a short whip with a tapered end, and attacked to this tapered end were three tongs of hard tanned elk hide, which cut like knives.

The roads were poor, and there were no inns between towns for travellers. Alcoholism was a major problem throughout the nation. There was little intellectual curiosity – even a simple knowledge of astronomy, such as the ability to predict eclipses, could lead to a charge of witchcraft.

One foreign diplomat said that the habit of oppression had “set a print into the very mindes of the people. For as themselves are verie hardlie and cruellie dealte withall by their chiefe magistrates and other superiours, so are they as cruell one against an other, specially over their inferiours and such as are under them. So that the basest and wretchedest [peasant] that stoupeth and croucheth like a dog to the gentleman, and licketh up the dust that lieth at his feete, is an intollerable tyrant where he hath the advantage.”

Foreigners saw the Russians as a semi-barbaric, insular people and state, arrogantly self-assured as the true bearer of Christianity, but rife with ignorance, supersitition and immorality. One visitor to Muscovy made up a rhyme about it:

Churches, ikons, crosses, bells, / Painted whores and garlic smells, / Vice and vodka everyplace – / This is Moscow's daily face.

To loiter in the market air, / To bathe in common, bodies bare, / To sleep by day and gorge by night, / To belch and fart is their delight.

Thieving, murdering, fornication / Are so common in this nation, / No one thinks a brow to raise – / Such are Moscow's sordid days.

But it was not as bad as foreigners claimed. The common people were genuinely religious, and a renaissance was taking place – through trade and other contracts, Western cultural influences were beginning to have an effect. These influences, combined with Russia's rich Byzantine heritage, might have brought about a true renaissance, but these currents would be overwhelmed by the bloody legacies of the immediate past.

Ivan the Terrible's tyrrany had divided the nation in two; and the social enmities he had created would outlive him. In 1581, he killed his eldest son, Tsarevich Ivan Ivanovich, during an argument. When he died himself in 1584, his son Fyodor succeeded him.

Fyodor I was absent-minded and reluctant to be monarch, and he relied heavily on the boyars appointed to be his guardians. Plots sprung up, a power struggle ensued, and Boris Godunov became the dominant figure behind the throne. Boris was a noble of Tatar origin, and his sister was married to Fyodor. Soon, he was recognized as Lord Protector (as the English called him), and the de facto head of state.

Under Godunov's reign, trade prospered, revenue increased, taxes decreased, and peace returned. Fugitive peasants returned to their homesteads, more arable land was cultivated, grain prices fell, and granaries recorded large surpluses. Construction increased, with stone walls around Moscow and Smolensk; many new churches, expanded port facilities at Arkhangel, and the completion of the Ivan the Great Belltower in the Kremlin, reaching upwards in three tapering octagonal tiers.

There was military progress as well. Godunov made headway against the nomadic peoples in the southern steppes (between Russia and the Crimea), established a series of important fortified towns, recoered territory lost to Sweden during the Livonian War, and pushed Siberian conquest eastwards from the Ob River.

When Fyodor died in 1598 without an heir, Godunov was offered the crown. He denied it three times, to demonstrate the inevitability of his succession, and looked to the masses for his support. At his coronation (in the Dormition Cathedral on September 1st, 1598) , he declared: “As God is my witness, there will not be a poor man in my stardom!” and tore the jewelled collar froms his gown. Jealous nobles called him Rabotsar, which means “the Tsar of slaves”.

There are no known contemporary portraits of Godunov, but this is what he probably looked like.

After Godunov's coronation, favours were announced, army & administration officials received a substantial salary increase, merchants were granted tax breaks, and the natives of Western Siberia were exempted from taxes for a year. Godunov said: “We take a moderate tribute, as much as each can pay...And from the poor people, who cannot pay the tribute, no tribute is to be taken, so that none of the Siberian people should be in need.”

But this could not solve all the problems. The biggest problem was the competition among landed proprietors for peasants to work their estates. The more prosperous of them tempted peasants away from their smaller holdings. Many of these small holdings were held on military tenure, so their decline affected the security of the nation.

The government tried to solve this problem by binding the peasants to the soil. Peasants' freedom of movement had already been severely curtailed over the years, but now new decrees pushed them towards serfdom.

The service gentry squeezed everything they could from their peasants, who were already near breaking point because of state taxation. As a consequence, violence spread. In Russia's heartland, bands of highwaymen (who were once peasants) ransacked monasteries & manorial estates. Along the southern frontier, legions of the disaffected accumulated. Things were moving towards rebellion.

From 1601 – 03, protracted crops failures led to famine and mass starvation. Godunov distributed money and grain from the public treasury to those who were destitute, but widespread hoarding & profiteering by landlords & merchants (including the Stroganov family) not only negated his actions but made it worse.

Whole villages were wiped out. People ate cats, dogs and rats, as well as bark and straw. Human flesh was sold in public markets. An eyewitness wrote that every day in Moscow, “people perished in their thousands like flies on winter days. Men carted the dead away and dumped them into ditches, as was done with mud and refuse, but in the morning, “bodies half devoured, and other things so horrible that the hair stood up on end” could be seen. A court apothecary rescued a little girl from starvation, and entrusted her to a peasant family; he later learned that they had eaten her.

Thousands of unemployed labourers, and peasants abandoned to their fate by uncaring masters, scavenged throughout the countryside, or fled into the wilderness. This was the Time of Troubles, which lasted from 1598 to 1613.

It was beyond Godunov's control, and his standing fell. He was a legitimate tsar, properly elected; but he couldn't claim any dynastic link with Russia's “sacred” past. People soon began to see him as a ruthless usurper who had taken the throne through violence, crime and deceit. Rumours spread that he'd murdered Tsarevich Dmitry Ivanovich (Ivan the Terrible's 9-year-old son by his seventh wife); that he'd poisoned his own sister; that he'd poisoned Fyodor I himself. Godunov's spy network uncovered many plots, but discontent was still growing stronger.

There was an uprising in 1603 by peasants, fugitive slaves and bandits, which the army put a stop to. The people began to long for the protection of a “born tsar”, romanticizing even the worst parts of their past.

Then a rumour sprang up that Tsarevich Dmitry had miraculously survived his assassination, and was about to retake the throne. The pretender (known later as False Dmitry I) was backed by the Poles, and in October 1604 he crossed into Muscovy, leading an army of mercenaries and volunteers. This False Dmitry was conventionally ugly, “a strange and ungainly figure with facial warts and arms of unequal length”. He was a charismatic leader, and many people joined his cause. His army was over 16,000 men by November. Godunov, feeling helpless, turned to sorcery & divination to try and alter his fate.

False Dmitry I.

Godunov died on April 13th, 1605, from poison or a stroke. His wife and son were murdered within the next few weeks, and the Kremlin was stormed. False Dmitry I ruled for nearly a year, from June 10th, 1605, to May 17th, 1606.

Then he was toppled by Vasily Shuisky, who became Tsar Vasily IV. Shuisky had the right pedigree, but not popular support.

New uprisings and foreign invasions followed this. In June 1607, False Dmitry II, again backed by the Poles, advanced on Moscow. This led to Vasily IV's deposition in July 1610, and the installation of a Polish tsar, Vladislav I (he would later become King of Poland, in 1632).

Vasily IV (17th-century painting).

It seemed as if Muscovy would be partitioned. Russian popular armies rose up in the north and east, and advanced with patriotic fervour. On October 25th, 1612, the Polish garrison in the Kremlin capitulated, and the foreigners were driven out.

On February 21st, 1613, a national assembly elected a new tsar. This was Mikhail Fyodorovich Romanov (Mikhail I), the grand-nephew of Anastasia Romanova, Ivan the Terrible's first wife. The Time of Troubles then came to an end.

#book: east of the sun#history#military history#economics#poverty#classism#time of troubles#russia#khanate of kazan#khanate of astrakhan#kazan of sibir#poland#siberia#moscow#ivan the terrible#tsarevich ivan ivanovich#fyodor i#boris godunov#tsarevich dmitry ivanovich#false dmitry i#vasily iv#mikhail i

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are plenty of larger regions named for what were once smaller regions; “Italy” once meant a region at the southwestern tip of the peninsula, “Russia” expanded as a geographical term as the empire marched east, “Yamato” originally applied to a small region around Nara before becoming a metonym for Japan as a whole, but I’m having trouble thinking of many regions or countries which are named after a single city or similarly small place that eventually expanded to encompass a broad area. There’s Mexico, of course; possibly Siberia, since IIRC the Sibir Khanate took its name from its capital (also called Qashliq). Romania and Rum are originally both named after Rome, of course (and get additional points for not containing the place they’re named for!).

#zimbabwe is a marginal case#since it is a conscious attempt at legitimacy through historical reference#not a gradual evolution of nomenclature

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is also where it's worth noting one nuance of the Eurocentric historic bias that prevails all too often:

There is one part of modern Europe that really can rely on a decolonization framework to explain its history and its cultural....issues. The Balkans, where the Osmanli Devleti's power over them was dismantled mostly by outside factors deciding to exploit the Russian provision in an 18th Century treaty that Ottoman Christians were useful pawns. They were conquered by the Ottoman Empire, which ruled them and exploited them as provinces, and did as much as it could to enforce Islamic and Turko-Islamic culture and to convert people who did not want to be converted any more than anyone conquered in any other holy war.

No other part can, though this is a framework that is rather interesting when applied to medieval and early modern Spain and Russia and showcasing how decolonization in one sense can and does lead right into new empires spawning out of the corpses of the older ones. Spain went straight from crushing the last trace of Al-Andalus to the conquest of the Americas, and the foundations of the first core of Latin America (insert obligatory reference to that map showing South America to Mexico scooped out and the wealth on Europe everywhere except Spain and Portugal and how much this shows ahistorical understandings of a significant portion of the Western hemisphere here).

Russia overthrew the Golden Horde and then went straight into the conquest of the Khanates of Astrakhan and Sibir, two of its successors, and from there went overnight from the fringe of northern Europe to the most triumphant example of the space filling empire. Decolonization from the imperialism of the Jochids did not make the Russians empathetic or any less imperialist under the Romanovs.

Given decolonization frameworks applied to the Republic of India annexing Goa, ruled by the Portuguese for around 500 years, long before the Raj, after they conquered it, it's hard to accept any framework that would extend it in some of the ways the Global South is right to insist it should and that the experiences of the Reconquista and the regathering of the Russias is really that different as historical patterns.

One can also argue at least in part that awareness of that vulnerability is why Spaniards and Russians were somewhat more efficiently murderously aggressive than other Europeans at the start and interested in being so.

Not that Al-Andalus and the Khanate of the Golden Horde show up much in Eurocentric takes of European history. It wouldn't do to note Europe's most brilliant civilization in the medieval era was the last redoubt of the Ummayyad Caliphate, nor that its largest medieval state was the Jochid Khanate in the Russian steppe.

1 note

·

View note

Text

@caesarsaladinn said:

it's also geographically contiguous, so unless you know your history, it's easy to think the whole landmass has just always been Russian

oh yeah that helps too. altho people know about genghis khan, they should really like. think about where that must have been. it helps that northeastern russia has basically just had like, hill people (i mean. not in the literal sense. its flat. but yknow. hill-type people) since forever, theres not a lot of like, Grand Old History to draw on there. just humans being humans. the khanate of sibir needs to work on its PR

@st-just said: you'd think Americans would understand this

i mean, even leftists often dont think of mainland US as being an empire, and a settler colony is a bit different from a classical empire. honestly our languge about empire/colonization/imperialism/etc fucking sucks, like, its so weird and ambiguous and bad. Ideology i guess

was thinking about "russia cant be imperialist" because like. the thing about russia is, unlike a lot of 19th century empires, it never like...fell apart. a sufficiently old empire just sort of. becomes a nation. thats what nations are. but that makes it much less noticeably an empire (or former empire. or whatever)

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Daily reminder that Russia didn't "colonize" her Asian parts. She just fought back against the Mongols, wreaking havoc (enslaving...) in Russia. They conquered the Khanate of Kazan in 1552, the Khanate of Astrakhan in 1556 & the Khanate of Sibir in 1582. To defend themselves.

Oh, and I can add: they didn't take that land from the Mongols. They took it back from them.... yes, Northern Asia (and Northern America) used to be EUROPEAN (by blood).

0 notes

Photo

Arrivals & Departures - 25 August 1530 Celebrate Ivan IV Vasilyevich [Ivan the Terrible] Day!

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (/ˈaɪvən/; Russian: Ива́н Васи́льевич, tr. Ivan Vasilyevich; 25 August 1530 – 28 March [O.S. 18 March] 1584), commonly known as Ivan the Terrible (Russian: Ива́н Гро́зный (help·info), Ivan Grozny; "Ivan the Formidable" or "Ivan the Fearsome"), was the Grand Prince of Moscow from 1533 to 1547 and the first Tsar of Russia from 1547 to 1584.

Ivan was the crown prince of Vasili III, the Rurikid ruler of the Grand Duchy of Moscow, and was appointed Grand Prince at three years-old after his father's death. Ivan was proclaimed Tsar (Emperor) of All Rus' in 1547 at the age of seventeen, establishing the Tsardom of Russia with Moscow as the predominant state. Ivan's reign was characterized by Russia's transformation from a medieval state into an empire under the Tsar, though at immense cost to its people and its broader, long-term economy. Ivan conquered the Khanates of Kazan, Astrakhan and Sibir, with Russia becoming a multiethnic and multicontinental state spanning approximately 4,050,000 km sq (1,560,000 sq mi), developing a bureaucracy to administer the new territories. Ivan triggered the Livonian War, which ravaged Russia and resulted in the loss of Livonia and Ingria, but allowed him to exercise greater autocratic control over Russia's nobility, whom he violently purged in the Oprichnina. Ivan was an able diplomat, a patron of arts and trade, and the founder of Russia's first publishing house, the Moscow Print Yard. Ivan was popular among Russia's commoners (see Ivan the Terrible in Russian folklore) except for the people of Novgorod and surrounding areas who were subject to the Massacre of Novgorod.

Historic sources present disparate accounts of Ivan's complex personality: he was described as intelligent and devout, but also prone to paranoia, rages, and episodic outbreaks of mental instability that increased with age. Ivan is popularly believed to have killed his eldest son and heir Ivan Ivanovich and the latter's unborn son during his outbursts, which left the politically ineffectual Feodor Ivanovich to inherit the throne, a man whose rule directly led to the end of the Rurikid dynasty and the beginning of the Time of Troubles.

0 notes

Photo

Patrolling the mountainous regions of the Urals separating the historic Tsardom of Muscovy from the Sibir Khanate . . . . . . . . . . . #KobaTheDread #BlackRussianTerrier #HoundOfTheBolsheviks #ScourgeOfTheFascists #StalinsKillingMachine #PrideOfSiberia #SiberianBeast #FirstSovietArmouredDivision #SovietRedBannerNorthernFleet #InSovietUnionDogWalksYou #ToTheGulag #ReleaseTheKraken #140PoundsOfSocialistSavagery #DogsOfInstagram #defendingthemotherland #СлаваРодине! (at David Balfour Park)

#scourgeofthefascists#dogsofinstagram#siberianbeast#insovietuniondogwalksyou#славародине#defendingthemotherland#prideofsiberia#houndofthebolsheviks#sovietredbannernorthernfleet#blackrussianterrier#firstsovietarmoureddivision#tothegulag#140poundsofsocialistsavagery#stalinskillingmachine#kobathedread#releasethekraken

0 notes

Photo

Ishtar: He was the Grand Prince of Moscow from 1533 to 1547, then Tsar of All Rus' until his death in 1584. The last title was used by all his successors! During his reign, Russia conquered the Khanates of Kazan, Astrakhan and Sibir, becoming a multiethnic and multicontinental state spanning approximately 4,050,000 km2 (1,560,000 sq mi). He exercised autocratic control over Russia's hereditary nobility and developed a bureaucracy to administer the new territories. He transformed Russia from a medieval state into an empire, though at immense cost to its people, and its broader, long-term economy!!! He is a stronger Rider on fate/series!! He is Ivan The Terrible!! • #ivantheterrible #rider #fate #fateseries #fategrandorder #tzar #ivanivvasilyevich #political https://www.instagram.com/p/BofEPsgCHgW/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=fmgrlx0syy3r

0 notes

Photo

Ivan the Terrible (16.01.1547—18.03.1584)

For other uses, see Ivan the Terrible (disambiguation). Ivan IV Vasilyevich (Russian: Ива́н Васи́льевич, tr. Ivan Vasilyevich; 3 September [O.S. 25 August] 1530 – 28 March [O.S. 18 March] 1584), commonly known as Ivan the Terrible or Ivan the Fearsome (Russian: Ива́н Гро́зный (help·info), Ivan Grozny), was the Grand Prince of Moscow from 1533 to 1547 and 'Tsar of All the Russias' from 1547 until his death in 1584. His long reign saw the conquest of the Khanate of Kazan, Khanate of Astrakhan and Khanate of Sibir, transforming Russia into a multiethnic and multicontinental state spanning almost one billion acres, approximately 4,050,000 km2 (1,560,000 sq mi). Ivan managed countless changes in the progression from a medieval state to an empire and emerging regional power, and became the first ruler to be crowned as Tsar of All the Russias. Historic sources present disparate accounts of Ivan's complex personality: he was described as intelligent and devout, yet given to rages and prone to episodic outbreaks of mental instability, that increased with his age, affecting his reign. In one such outburst, he killed his groomed and chosen heir Ivan Ivanovich. This left the Tsardom to be passed to Ivan's younger son, the weak and intellectually disabled Feodor Ivanovich. Ivan's legacy is complex: he was an able diplomat, a patron of arts and trade, founder of the Moscow Print Yard, Russia's first publishing house, a leader highly popular among the common people (see Ivan the Terrible in Russian folklore) of Russia, but he is also remembered for his paranoia and arguably harsh treatment of the Russian nobility. The Massacre of Novgorod is regarded as one of the biggest demonstrations of his mental instability and brutality.[better source needed] More details Android, Windows

0 notes

Text

Siberian History (Part 7): Mangazeya

The Russian frontiersmen in Siberia still had to depend on Moscow for support (such as administrative & logistical support). During the Time of Troubles, the Siberian garrison was mostly left to themselves, which lead to disease, starvation and death.

The natives peoples of Siberia took the opportunity to make several attempts at an uprising. The most powerful was in 1608, when Princess Anna of Koda, a “Tartar Joan of Arc”, nearly succeeded in uniting the entire native population of Western Siberia to revolt.

In 1612, an attempt was made to re-establish the old Khanate of Sibir “as it had been in the time of Kuchum”. But it was betrayed at the last minute, and ten of its ringleaders were rounded up and hanged.

By now, the Russian occupation of the Ob-Irtysh Basin had increased the nation's size by a third. But in Moscow, Siberia still wasn't properly understood as a geographical entity, and so it was used as a political bargaining chip.

Boris Godunov, for example, tried get an influential boyar to support him against False Dmitry I, by promisng him “the Kingdoms of Kazan, Astrakhan, and all Siberia”. The False Dmitry II promised to reward his brother-in-law, a powerful Polish noble, with “the whole land of Siberia” for his help.

But the Ob-Irtysh Basin had scarcely been secured before the Russian advance into the next great river valley, the Yenisei, began.

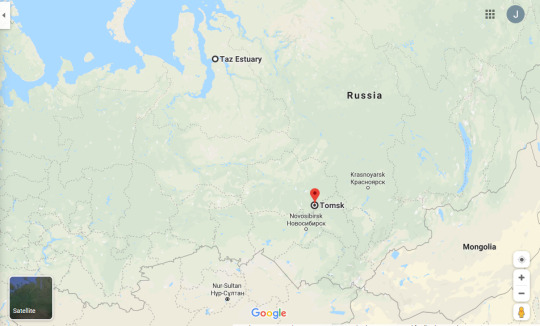

The Russians ascended the eastern tributaries of the Ob River, and crossed a low plateau to streams flowing into the Yenisei. By 1619, they had taken all the important river routes and portages that connected those two rivers. They organized expeditions from Mangazeya (in the north) and Tomsk & Ketsk (in the south), coming at the river valley from both directions.

The Taz Estuary marks the area where Mangazeya was located.

They met the Tungu people on the lower Yenisei, and the Buryats (whom they'd never heard of before) on the upper Yenisei. The Buryats lived in a region that was rich in furs, and they practised animal husbandry; they were rumoured to grow crops and have access to silver. This was guaranteed to interest Russia.

The Tungu people (east of the Yenisei) and the Buryats (around Lake Baikal) fought to prevent Russia from establishing bases in their territory, but failed. Yeniseysk was founded in 1619 (where the Angara and Yenisei Rivers meet); Krasnoyarsk was founded in 1627 (astride cliffs of red-coloured marl); and Bratsk was founded in 1631 (on the Angara River).

On the upper Yenisei River (the southern part of it), the Russians met the staunch resistance of the Kyrgyz people and the Kalmuks, both steppe nomads. Their homelands bordered Siberia to the south, and they were continually hostile. Eventually, a solidly-fortified line was established over the southern frontier, but this would take two centuries.

Meanwhile, Russian mariners had developed the sea route north of Russia from Arkhangel to Mangazeya (which was just a few miles above the Arctic Circle). At Mangazeya, they bartered goods with the local Khanty and Samoyedic peoples for furs. Mangazeya prospered and grew, attracting more and more traders, who were willing to navigate the treacherous waters of the Kara Sea.

One contemporary account says that: “Hundreds of thousands of sable, ermine, silver and blue fox skins, and countless tons of precious mammoth and walrus ivory” were shipped every year from Mangazeya and Europe. This was an illicit trade that had begun during the Time of Troubles, and the government couldn't manage to gain control of it.

Porcelain, silk, and other expensive fabrics were traded (through middlemen) from Central Asia & China to Mangazeya. The city was “a virtual Baghdad of Siberia, where big commercial deals were celebrated at fabulous feasts that lasted for days, and that featured the best European wines and local delicacies like sturgeon, caviar, mushrooms, berries, and venison and other game.”

By the time stability was restored in Moscow, reports of Siberia's vast wealth in furs had spread far and wide. This, of course, attracted the attention and greed of European powers who wanted new colonies. The Russian government worried that foreign agents might try to trade directly with the natives, or even attempt an armed invasion (through the Taz Estuary) to seize the whole of north-western Siberia.

Meanwhile, inland merchants working out of the Urals, Tyumen and Tobolsk were envious of Mangazeya, as it siphoned off commerce that would otherwise have come to them.

So in 1619, the Russian government closed the sea route to Mangazeya. They forbade even Russians to use it, in case foreigners found it out from them.�� Anyone who broke this law was to be “put to the hardest possible death, and all their homes and families destroyed branch and root”.

Navigational markings were torn up. Surveillance posts were established along the coast, to intercept and kill anyone who tried to get through. A coastal fort was built on the Yamal Peninsula, commanding the portage between the Ob Gulf and the Kara Sea. Maps were falsified to depict Novaya Zemlya as a peninsula, rather than an island. This would cause problems for later mariners who were using them as nautical guides.

Gradually, Mangazeya declined, and the rich merchants left. In 1643, its administrative apparatus was moved to Turukhansk – this city was founded at the mouth of the Turukhan River, a tributary of the Yenisei. For a while, it was known as “New Mangazeya”.

In 1678, Mangazeya was burned to the ground, without any official explanation. The local Samoyedic peoples called its ruins Tagarevyhard, which means “destroyed town”. The site wouldn't be rediscovered for almost three centuries.

Mangazeya, perhaps more than any other early settlement, was the proof of the enormous wealth that Siberia possessed. In 1632, a former military governor of the district strongly encouraged the tsar to press on from the Yenisei to conquer the Lena River Basin. His encouragement was inspired by the riches of Mangazeya.

#book: east of the sun#history#military history#colonialism#economics#trade#native siberians#tungu people#buryats#kyrgyz people#kalmuks#khanty people#russia#khanate of sibir#siberia#yeniseysk#krasnoyarsk#bratsk#mangazeya#turukhansk#boris godunov#false dmitry ii

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Messengers from Yermak at the red porch in front of Ivan the Terrible (1884), by Stanisław Jakub Rostworowski.

Cossacks under Yermak Timofeyevich conquered the Khanate of Sibir in the 1580s, marking the beginning of Russia's conquest of Siberia. This was an expedition organized by the Stroganovs, a powerful merchant family, who had originally been given permission by the tsar. However, the tsar eventually withdrew his permission, afraid that Russia didn't have enough manpower or resources to do the job. The Stroganovs ignored this.

In a letter from November 16th, 1582, the tsar reproved the Stroganovs for “disobedience amounting to treason”. Meanwhile, Yermak had sent Ivan Koltso, his second-in-command, back home to announce the expedition's success. The tsar planned to hang Koltso, but he prostrated himself before the tsar, proclaimed him lord of the khanate, and displayed his loot (five times the annual tribute the khanate used to pay) to the stunned court. Ivan immediately pardoned Koltso and Yermak, and promised reinforcements.

#history#military history#colonialism#art#russian conquest of siberia#russia#khanate of sibir#siberia#cossacks#yermak timofeyevich#ivan the terrible#ivan koltso#stanisław rostworowski

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portrait of Yermak Timofeyevich (17th century).

Alexei “Yermak” Timofeyevich (d. 1585) was a Cossack ataman, a third-generation bandit and the most notorious pirate on the Volga River at that time. Army patrols attempting to enforce the tsar's authority on the river forced many Cossacks to flee, and a group under Yermak ended up joining the frontier guard of the Stroganovs, a powerful merchant family.

In 1581, Yermak led the first expedition to Siberia, in which they conquered the capital of the Khanate of Sibir and forced the khan to flee. However, attrition and declining provisions forced an eventual retreat, and during a doomed river battle with the Tatars, Yermak attempted to escape by boat, but drowned due to the weight of his armour.

#history#military history#colonialism#art#conquest of siberia#russia#khanate of sibir#siberia#cossacks#yermak timofeyevich#kuchum

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A miniature from the Kungur Chronicle (late 16th century) showing the fall of Qashliq, capital of the Khanate of Sibir, to the Russians under Yermak.

#history#military history#art#colonialism#conquest of siberia#russia#khanate of sibir#siberia#qashliq#yermak timofeyevich#kungur chronicle#remezov chronicle

6 notes

·

View notes