#or if someone else wants to please be my guest since my executive dysfunction is so bad

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

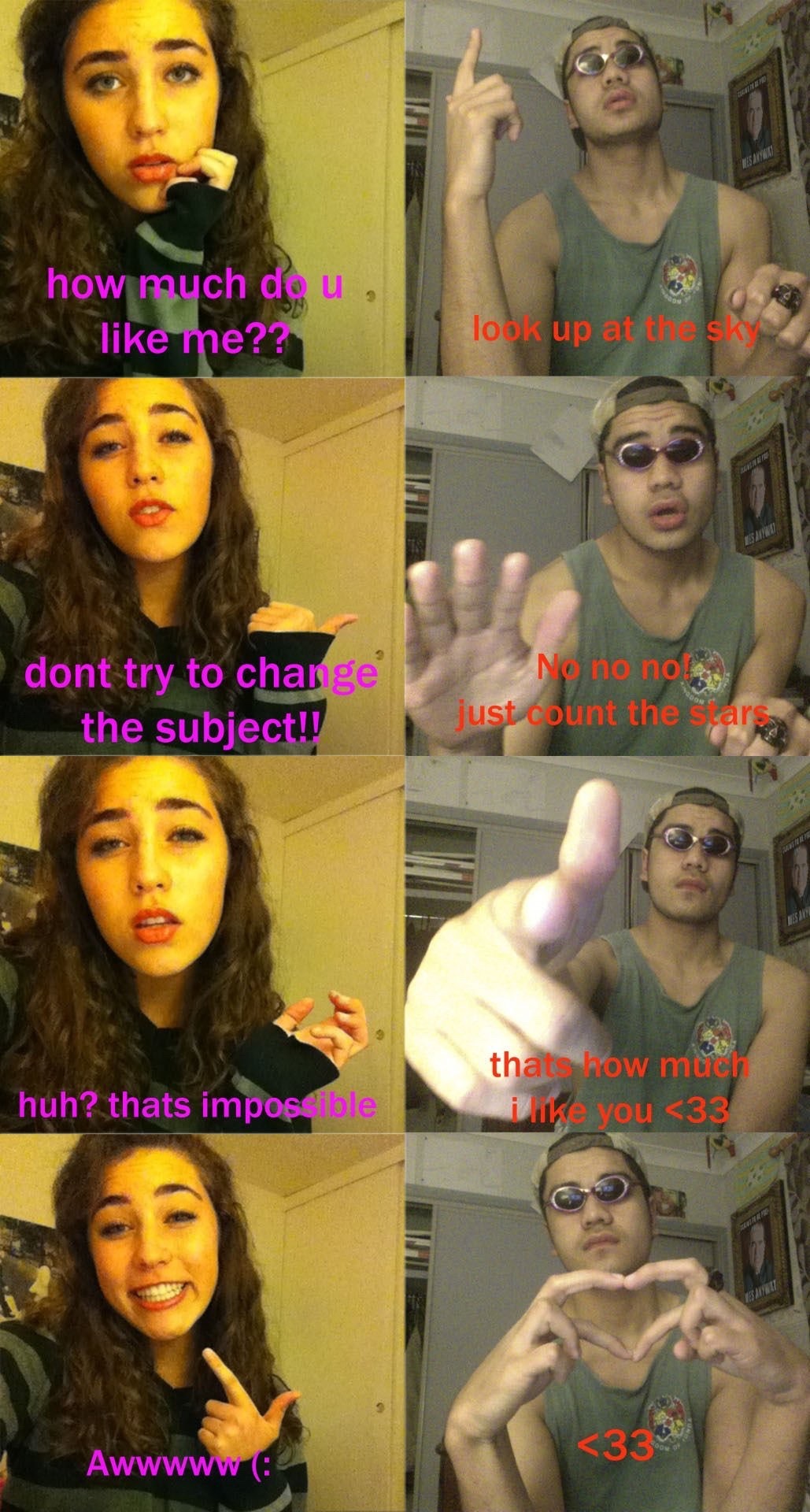

whenever my drawing skills return from war i NEED to make this with jade and dave

#or if someone else wants to please be my guest since my executive dysfunction is so bad#hs#davejade

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Masterpost: On calling characters autistic

Part 1: Whether you should explicitly call your character autistic, and how you should go about it

So, you have created an autistic character. You love them, you know their likes and dislikes and you are determined that this is going to be a positive and realistic portrayal of autism. There's one problem though - how do you let your readers know that the character has ASD?

Actually explicitly calling your character “Autistic” can be awkward. Maybe it’s because you don’t want to interrupt the flow of the story, maybe it’s because you don’t want to risk backlash if people dislike your representation of autism. Maybe “autistic” isn’t a word that exists in the world or time period of your story. So, do you have to say it outright?

There isn't a moral imperative to call your character “autistic”. One of my favourite autistic characters is never called autistic in-universe. But our blog is about encouraging accurate representation of autistic characters, and if you don't actually call them autistic...is it actually representation?

Should I call my character autistic?

Autistic characters in media are very important for several reasons. The media we consume contributes to shaping us and our worldviews. If someone reads books and watch movies which contain complex, realistic autistic characters, they’re more likely to 1) be aware of what autism actually is, and 2) see autistic people as human beings, and treat them as such. These characters are also important to autistic people themselves: seeing characters like yourself portrayed in a positive light can boost your self esteem and help you feel less alone.

If you make a great autistic character and you don’t explicitly call them “autistic”, it’s not guaranteed that everyone will understand that they’re supposed to be autistic. Many people don’t have a very accurate working knowledge of autism, and they might not understand that a character is autistic if they don’t fit their narrow, stereotypical view of what an autistic person looks like. Thus the people that would benefit most from this representation might miss it completely.

Of course, the choice is yours, but we would strongly encourage you to explicitly call your character autistic so that you’re 100% sure your readers will pick up on it. Ideally, this would happen in the work itself, but at the very least we would encourage you to make it explicit when you, the writer, discuss the character (on social media, in interviews, in synopses of your work). Bare in mind that if you don’t say it explicitly within the work, you are very likely to end up with readers who deny that the character is autistic because they don’t behave in ways that match their perception of what autism is - they fall in love, they speak, they don’t behave in exactly the same way as their autistic nephew does. It is preferable for the reader to be able to identify the character as autistic without needing to pay attention to the author’s writing outside of the work itself.

When?

So, it’s decided! You are definitely going to tell the audience that the character is autistic. When is the best time to let them know? Telling the audience does not have to be the first thing you do when you introduce the character - it depends what you want to do with your story.

Here are a few general possibilities:

When the character is introduced - immediately telling the audience that the character is autistic means that the character’s autism will play a big part in the audience’s interpretation of the character. You might choose this option if you feel it is important for the audience to understand the character is autistic. If you are telling a story “about being autistic”, the fact that the character is autistic is very likely to be one that you will want to raise at the start, but even in a story that is not “about” being autistic, knowing your character’s neurotype from the outset can help the audience to interpret their behaviour.

After the character has been established - your character has already been established and you have demonstrated their autistic traits; calling your character autistic at this point is a way of confirming it and making it explicit for anyone who has not realised so far.

A “big” reveal - this isn’t something that I have seen used, but there is the option of “revealing” that your character is autistic later in the story. This could be used a way of subverting the expectations of readers who have stereotypical views of autism (and confirming other readers’ “headcanons”) for characters who have atypical traits. Otherwise, it could be presented as the solution to a “mystery” about the character.

It is brought up several times - you don’t have to only mention the character’s autism once! Their autism might be referred to multiple times during the story.

In the description/summary of your story - This a useful option if the story takes place in a point in history before the diagnosis of “autism” existed. It can also be used to clarify the terms you use for stories set in the future/different worlds. (The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time used this method, only calling the main character autistic on the cover - but you need to make sure that you actually do a decent job inside the book!)

How?

OK, time to actually decide how to tell your audience that the character is autistic. Luckily, there are lots of options!

We are going to list several strategies. There are lots of ways of fitting these into context: try relating what you say to an autistic trait which is affecting your character at that point in the story: are they struggling with executive dysfunction? having fun stimming? looking up information about their special interest?

Here are some ideas of topics related to autism that might provide you with the opportunity to casually drop in the term “autistic”: sensory overload, stimming, executive dysfunction, alexithymia, difficulties with social interactions, problems with communication, special interests, eye contact, meltdowns and shutdowns.

Here are some techniques for telling the audience that the character is autistic. Each suggestion is accompanied by at least one example to illustrate how it can be used:

The narration says “they’re autistic” - it can be slipped in as a sort of “aside” if that feels more natural in your story

“Karen swore loudly. The village church bells had been ringing for 45 minutes and her head felt like it was going to split in two. Of course being autistic didn’t help, but the main problem was the bloody eejit who decided it was a good idea to hold bell practice today of all days.”

“Ming looked down the guest list. Selvie was bringing Cheng Mae as her plus-one. Ming had only met her once: he knew that she was autistic, that she loved Criminal Minds, and that Selvie was trying to take the relationship to the next level, but none of this helped him with choosing what table to put the couple at. He called Helen in from the kitchen to ask what she thought.”

The autistic character says they’re autistic (in dialogue) - either explicitly telling another character, or mentioning in passing

“Sorry I went a bit weird yesterday - I’m autistic and crowds are really overwhelming for me. Can we try again next Saturday? You can come ’round to mine and I’ll cook a romantic dinner”

J: How did you choose your therapist? I’m trying to find one K: She specializes in working with autistic people. My dad helped me find her. J: Oh, is she expensive?

The autistic character says they're autistic (as the first-person point of view narrator) They might mention it as a personal aside, or they may refer to it repeatedly throughout the narrative.

“I hate the store. I have been to every aisle at least twice already, but either two items are in the same aisle but not written next to each other on the list, or I can’t see the item I’m looking for. I know I struggle with finding things directly in front of my face because I’m autistic—my brain just doesn’t process the images my eyes are passing over fast enough—but it’s so annoying. I just wanted to find the cereal my sister likes.”

Refer to (or flashback to) a time in the past when it came up For example, the character could refer to to being in special ed at school, their parents might talk about the character having atypical development (eg. not speaking until a later age than usual), they could refer to the mental health professional who first suggested that they seek out a diagnosis, the character might make a comment comparing something to one of the tests they did while being assessed for autism, there might be a flashback to ABA sessions.

“Hey, Cam, you know that you are allowed to say when you disagree with something, don’t you?” “Yes.” Cam hesitated. “Um... I mean, yes, in theory. But I was taught in social skills that I had to smile and nod when people speak. It’s hard.” “Of course, I forgot. It was more important for them to teach the autistic kid to be compliant than to teach you how to communicate your needs,” he scowled. “Sarcasm,” he added “Thanks. I realised, this time.”

Another character discloses that the character is autistic (note: this is something that is not necessarily an appropriate thing to do in real-life — please don’t go talking about other people’s diagnoses behind their backs unless you know EXPLICITLY that this is ok with them)

“What’s the deal with Zephyr? Is he always such an arse?” Caroline sighed, “listen, Katharina, Zephyr isn’t trying to be rude. He’s autistic, he can’t pick up on your hints that you want to change the subject. Just tell him—nicely—that you want to talk about something else”

Chantelle looked the teacher in the eye, her face resolute. “Please, Mr Clive, Aaron is autistic, and I need to know that the school understands that. Things have been difficult for all of us since the earthquake, but the changes have been really hard for him. We lost our house, we’ve moved to a new area. Can I work with someone from the school’s SEN department to plan his induction?”

Another character mentions it when talking to the autistic character

“You know, when I first heard you were autistic I was expecting something different” “Robyn, this is not the time,” Enri snapped, “let’s fix the ship first, please”

From: K.Litchen To: I.Khan Subject: Favor please! <3

Hey, Ibby, you can definitely say “no” if you want to, but is it ok if I give your email address to my sister? She just found out that my nephew might be autistic and I think it would help her to talk to an autistic adult bc she’s panicking right now. Also, you left your dictaphone at the office on Friday, I can drop it off tonite if you like?

Thanks!!! Kim xxx”

Say it in the blurb/synopsis of your book/comic/film/etc

“17th Century France: The Beast of Gévaudan has been terrorising the area for two years. After two twelve year olds are killed in his village, Pierre, an autistic baker, begins investigating the attacks. He uncovers secrets, lies, and the terrible truth behind La Bèstia — but who will listen to M. Fournier’s oddball son?”

Include information in the background of a panel/scene (for a comic/film) Examples:

A panel shows a letter that is relevant for plot reasons, but you can see part of another letter behind it that references autism

The character goes to visit their therapist and there are posters about autism on the walls

The character wears some sort of autistic pride t-shirt (example 1 and example 2)

This information could also be backed up by (or highlighted in) your dialogue. The prose-based equivalent to having information in the mise-en-scene would be using descriptions of the background.

That’s it for part one!

Next time on On calling characters autistic:

Part 2 - what if autistic isn’t a term that exists in my story? We discuss telling stories that are set in the past, the distant future, and on other worlds

Part 3 - hinting We discuss ways to strongly imply that your character is autistic (techniques that you will ideally combine with explicitly calling them autistic)

659 notes

·

View notes