#or a sorta lower digestive tract

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

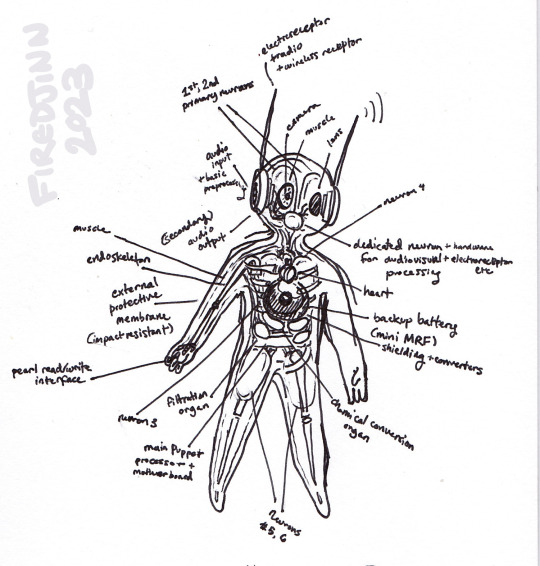

a puppet can be a creature too i think

(previously...)

#rain world#rainworld#iterators#headcanons#yeah these guys have a headcanon doc too lol#the process of making them is So Fucked Up#there's more in here that i couldnt fit but there should be some long term data storage parts as well. also some puppet models have “lungs”#or a sorta lower digestive tract#experimental designs!#the wiring in these things must be a nightmare...#ALSO: the muscle + camera eye thing is shamelessly yoinked from @spotsupstuff's headcanons because i really liked it lol#awful squishy meat machines my beloved...

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on http://fitnessandhealthpros.com/fitness/how-to-exercise-with-an-autoimmune-condition/

How to Exercise with An Autoimmune Condition

Autoimmune diseases really throw the body for a loop. You’re attacking your own tissues. Your inflammation is sky high. What’s usually good for you—like boosting the immune system—can make it worse. You’ll often restrict eating certain foods that, on paper, appear healthy and nutrient-dense. You take nothing for granted, measure and consider everything before eating or doing it. Sometimes it feels like almost everything has the potential to be a trigger.

Is it true for exercise, too? Must people with autoimmune diseases also change how they train?

First things first, exercise can help. You just have to do it right, or risk incurring the negative effects.

Don’t overtrain. Most autoimmune diseases are characterized by chronic inflammation. Anything that increases that inflammatory load, like too much exercise, will contribute. Overtraining—stressful exercise that you fail to recover from before exercising again—will increase your stress load and increase autoimmune symptoms.

Avoid exercise-induced leaky gut. Intense, protracted exercise—think 30-minute high-intensity metabolic workouts, long runs at race pace, 400 meter high intensity intervals—increases intestinal permeability. Elevated intestinal permeability has been linked to rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, and researchers think it may play a causative role in other autoimmune diseases too.

Yet not exercising might be even worse because exercise increases endorphins. Most think of endorphins purely as “feel-good” chemicals. They’re what the body pumps out to deal with pain, as a response to exercise, and it’s through the endorphin receptor system that exogenous opiates work. Endorphins also play an important role in immune function. Rather than “boost” or “diminish” it, endorphins regulate immunity. They keep it running smoothly. Without endorphins, the immune system begins misbehaving. Sound familiar?

Low-dose naltrexone is a promising therapy for multiple sclerosis and other autoimmune diseases. It works by increasing endorphin secretion, which in turn helps regulate the immune system’s misbehavior. I won’t posit that exercise is just as effective as LDN, but it’s certainly a piece of the puzzle.

This is the same relationship everyone has with exercise. Too much is bad, too little is bad, recovery is required, and intensity must be balanced with volume. The margin of error is just smaller when you have an autoimmune disease.

How should you exercise, then?

It depends on what type of autoimmune condition you have. Let’s explore some of the more common ones.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis hurts. It makes exercise a daunting prospect, which is why so many people with RA choose to stay inactive. Yet exercise consistently helps.

Exercise may improve sleep, reduce depression, and improve functionality in RA patients. Animal models of RA suggest that acute exercise inhibits the destruction of and even thickens cartilage.

What works:

Yoga works. A survey of RA patients found that many benefit from regular yoga practice. Another study found that it reduced pain, improved function, and increased general well-being in RA patients.

Light and very light intensity works. One study found that around 5 hours of “light and very light” intensity activity each day were often more effective at improving cardiovascular health in RA patients than 35 minutes of moderate intensity training each day. This isn’t necessarily unique to RA, as I think everyone’s better off walking and moving for 5 hours versus jogging for 30.

Working the afflicted joints works. For RA patients with hand and finger joint pain, a high-intensity exercise program centered on the hands improved functionality more than a low-intensity one.

High intensity works. 4 4-minute-long high intensity intervals on the bike at 85-95% of max HR increased muscle mass and cardio fitness while beginning to reduce inflammatory markers in women with RA. Notably, neither pain nor disease severity increased. In another study, RA patients were able to perform high-intensity resistance and aerobic training without issue.

Multiple Sclerosis

As with RA, people with multiple sclerosis really seem to benefit from exercise. They sleep better. If you start early, it may reduce the risk of developing MS. Exercise even drives brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is reduced in MS.

What works:

Tai chi works. Though the sample size was small, tai chi improved functional outcomes in patients with MS.

Both strength and endurance training work better than either alone. A 24-week lifting and endurance program has been used to increase BDNF in MS patients. A 12-week lifting and high-intensity interval program improved glucose tolerance in MS patients.

Lifting in the morning works. A recent study found that MS patients had more muscle fatigue and less muscle strength in the afternoon compared to the morning. Muscle oxidative capacity—the ability to burn fat during low level activity—did not differ between times.

Intense exercise works: The greater the intensity, the more BDNF you produce. That’s a general rule for everyone, and it’s no different for MS.

Crohn’s Disease

In Crohn’s, the body attacks the GI tract. It’s a bad one. Because Crohn’s can involve crippling GI pain, impaired digestion, fatigue, joint pain, and emergency diarrhea, patients often avoid exercise. They shouldn’t. If you can get past the mental roadblocks Crohn’s erects, exercise can really help.

What works:

Sprints and medium intensity both work, but sprints are less inflammatory. Both all-out cycling sprints (6 bouts of 4×15 second cycle sprints at 100% peak power output) and moderate cycling (30 minutes at 50% peak power) were well-tolerated by children with Crohn’s, but certain inflammatory markers were higher in the moderate group. Another inflammatory marker also stayed elevated for longer in the moderate group.

Resistance training and aerobic activity both work. Either alone or both in concert improve Crohn’s symptoms by modulating immune function.

Walking works. A low intensity walking program (just 3 times a week) improved quality of life in Crohn’s patients.

Type 1 Diabetes

People often forget about type 1 diabetes, but it’s an established autoimmune disease where the immune system attacks the pancreas and reduces or abolishes its ability to produce insulin. For type 1 diabetics who wish to reduce the amount of insulin they inject, exercise is essential.

It up-regulates insulin independent glucose uptake by the muscles. That removes the pancreas from the equation altogether, and it reduces the amount of exogenous insulin needed to process glucose.

It’s also safe, as long as you have your insulin therapy under control.

However, as high-intensity exercise tends to increase blood glucose and easy aerobic exercise decreases it in type 1 diabetics, you really need to have your ducks in a row. The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology journal recently published their consensus guidelines for safe exercise with type 1 diabetes, with the main takeaway being that diabetics should monitor their glucose levels before, during, and after training to ensure the numbers don’t get away from them. One study found that quickly giving a dose of insulin following high-intensity training counteracted the rise in blood glucose.

What works:

Combining resistance training with aerobic training works. The combination lowered insulin requirements and improved basically every marker of fitness, along with general well-being.

Resistance training works. In one study, resistance training seemed to lower blood glucose regardless of intensity. However, in one I mentioned above, subjects needed a dose of insulin following high-intensity resistance training to keep glucose under control. “Lift, but watch your glucose” appears to be the safe path forward.

Those are four of the most common and well-studied autoimmune diseases. Others may not have the same rich body of literature, but exercise probably helps there, too.

In Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients with normal thyroid hormone levels, for example, 6 months of aerobic training improved endothelial function.

Be careful with Graves disease, though.

Graves is an autoimmune hyperthyroid condition. Instead of underactive thyroids, Graves patients have overactive thyroids. There aren’t many trials on exercise in Graves patients, but there are some case studies that suggest some dangers.

In 2012, a Graves patient ended up with rhabdomyolysis (a terrible condition where you break down and pee out muscle tissue) after a non-strenuous exercise session.

Again in 2012, another patient with Graves got rhabdomyolysis after a session.

Euthyroid Graves patients—people with normal thyroid levels—can exercise safely, however. It improves functional capacity and delays relapse.

Again, be careful with Graves.

Because they’re so trepidatious about it and inactivity numbers are higher than the general population, most autoimmune disease patients would be better served with more exercise, not less. Autoimmune disease patients who loyally read MDA and other ancestral health blogs, however, might be the type to engage in CrossFit WODs and train really hard and rather excessively. If so, you might need less exercise, not more.

As I read the literature, autoimmune disease patients should be exercising in accordance with Primal Blueprint Fitness, albeit even more strictly:

Lift heavy and go intense, but keep it really brief. Low-volume, high-intensity. Short sprints, 3-5 rep sets, that sorta thing. Intensity is relative, so don’t think you have to squat your own bodyweight right away.

Spend most of your training currency on long, slow movements. Hikes, walks, gardening, gentle movement routines are your best friends. Basically anyone with an autoimmune disease can do these activities, and they always help.

Mobility training is required, especially in autoimmune diseases that affect the joints and connective tissues. If your joints are compromised, your other tissues have to be that much more limber, loose, and mobile. Try for something like VitaMoves or MobilityWOD.

Having an autoimmune disease doesn’t make you fragile. You can still train, and evidence shows that you can probably go harder than you think—provided you allow for ample recovery and keep a lid on how much training volume you accumulate.

Anyway, that’s my take on all this. I don’t have an autoimmune disease, though, so I’m only going on what the literature says. I’d love to hear from people who deal with autoimmune disease on a personal level. How do you exercise? What works? What doesn’t? What have you learned along the way?

Thanks for reading, everyone. Take care!

Post navigation

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Related Posts

If you’d like to add an avatar to all of your comments click here!

Originally at :Mark's Daily Apple Written By : Mark Sisson

1 note

·

View note

Link

A Secret Weapon For How to lose belly fat only can be seen on this website Any fast Net lookup will generate plenty of statements of ways to remove the undesirable Extra fat from close to your mid-segment. From about-hyped food plan tablets promising to reduce amounts of cortisol targeting your stomach Excess fat, to leading edge exercise routines. Avoid around stuffing yourself at foods; try to eat modest foods each day. Chewing gum and consuming by using a straw can cause excessive air to gather inside the digestive tract. Carbonated beverages, spicy foods, massive servings of beans or cruciferous vegetables, dried fruits and fruit juice generally induce gas and bloating. Use per week to introduce steps to help you lose belly fat as time passes and reduce bloating. You could possibly feel a little lighter just after 7 times, but a real loss of Unwanted fat will get several months or months. Should you suspect you will have snooze apnea or another slumber condition, talk to a physician and get addressed. The only way to lose Body fat from a stubborn space is always to lose pounds generally speaking. To do that, you need to be constantly consuming in calorie deficit eventually. (far more on this within the 5-Move Prepare section) If you make irrational or drastic modifications to your diet and training in hopes for a quick-fix, you've got by now missing. Probiotics are bacteria found in some foods and health supplements. They have quite a few wellbeing Gains, such as enhanced gut overall health and enhanced immune operate (sixty-eight). If you are not Lively now, it's a smart idea to Verify with all your overall health care supplier before starting a brand new Exercise method. As an alternative, Here is A fast bullet-point go to these guys define of what you have to know about burning fat, and why some Fats is more durable to lose than Some others: We have now taken an outing to the investigation on the most effective workouts to reduce lower belly Body fat. These physical exercises are basic to execute and will help you burn belly Body fat. Now have interaction your abs and bring your legs as much as a sorta 90-degree angle. Make sure your knees are touching and also more info here your toes also pointed. The data as for how the program operates might be received in the several resources check out here which might be presented in This system. It basically demands a handful of foods, which contain spices look what I found and herbs For the wellness's sake, you would like to check this source your midsection sizing for being less than 35 inches for anyone who is a woman and lower than forty inches for anyone who is a man. The difficulty arises whenever we keep on to take more of People calories much more than we, in fact, give them out. The effect could be the Fats stored in the program might be expanding.

#how to reduce belly fat#how to get rid of stubborn belly fat#how to reduce belly fat quickly#how do i get rid of belly fat#how to target belly fat#fastest way to get rid of belly fat#how to lose lower stomach fat#how to burn lower belly fat#lose lower belly fat#how to lose belly fat only#ways to lose belly fat#tips to reduce belly fat#how to lose abdominal fat#how to eliminate belly fat

0 notes

Text

A small town in Augusta GA

It was already hot as balls in Augusta, and everything where I was at was far and spread out. When I did arrive into a town (I never got the name) it was very poor and broken. A total of one convenient store and a small seafood restaurant. I was now broke again, starting to regret leaving Brunswick. I had a job there anyway so it was something, but I’m sick. I’ve had a very nice runny yellowish shit for days, and everyday it’s getting more and more colorful. As of right now I’m pure yellow, a sign of gallbladder problem or the digestive tract working to fast, or even worse, an infection. I would’ve been fired soon anyway. I recall what I assume is my kidneys, lower back left and right side, hurting if I hold my urge to urinate for longer than ten minutes, and even urinated all over myself at one point back at the Salvation Army. Yes embarrassing, disgusting, but alarming all the same. I’m genuinely worried. This town was worse than Brunswick as far as crime. I was told that when night shines one will sleep, and was told by an older black lady to watch my back. White boys are targets. I made my approach to a local convenience store, to use the bathroom and grab a Powerade. I was very dirty, but managed to scrub much of the dirt off my face with a sink. The lady at that store bought a drink and chips and spoke with me about God. Very well mannered and sweet woman. My karma from my past deeds continued to pay off, and the habit of thanking God after a blessing such as that one in prayer was becoming quite the habit. I know He doesn’t approve of everything I do. I know the bad things I’ve done will bite me later and is usually the result of events forcing me to move on. Things I won’t say here, not until I’m stable, however I am still mostly in His favor, and I accept that this is a trail I from Him that I practically asked for. When I left the shop a man who worked in the store gave me the rest of his friend’s smokes, he said they’ve been laying there in his car for a century. Then he told me he was just like me, except he finally saved to get a ride, and was trying to save to get settled. Cool. Can’t wait to reach that phase. I stopped by a small seafood restaurant along the way, to sit and charge my phone and consult reddit. One of the men who worked at this place asked me where were I was from. He was a person who worked for this place for eighteen years, with a golden grill on his teeth. I told him that I started in Brunswick and ended up here and that’s all that mattered. He said something to me that nearly triggered another round of unending paranoia. “Bruh if I was you I would move way up north. Not everybody is yo friend man, God does everything for a reason.” Why would he say that? Is there something behind the scenes that I didn’t see? Was the entire hood in the world trying to off me? What’s going on? Those are the thoughts of my mind every time something like that happens and it wasn’t the first time I’ve heard, “God does everything for a reason.” A while back, when I had a home a man needed a way home with his old man, and asked me to drive the old man’s car because the old guy was too drunk to drive and the young thug didn’t have a license. Of course I said hell yeah, he’s got his pops with him… and I’d miss driving, and good karma. That’s just me man, the type of person who only needs to hear ‘Adventure’ to motivate him to grab his balls and say fuck it. When I was driving he said to me,” Hey bro God does everything for a reason.” “....” “ Did you hear what I said? I’m serious lil bro, think about it real long and hard as to why God motivated you to do this, it might’ve just saved your life.” Questions man. So. Many. Questions. I left to the resturant to investigate the trains with the help of Maps. Aparently I was too close to the yard, one of the train operators threw a gatorade at me and yelled over the engine, “Hey man! You better get out of here! They just called the police on you man! Go get out of here!” I walked fast off the property, and hid into a nearby wooded area. After an hour I returned to the restaurant to charge my phone, and an old woman there insisted to buy me food, but I couldn’t accept… however a drink would be nice. She seemed aggravated by the fact I wouldn’t eat, but too much help in a small town like that and someone might think I’m playing people. Another man gave me seven dollars, I swear I didn’t ask. I did accept that though, cash is cash I’d be crazy to say no. Might even give people the idea that I’m racist. Definitely don’t need that. Back to the train yard I hid in between the trains to avoid being seen. None of the trains that arrived ever went north for some reason, but I had a strong feeling that at nightfall something would head north. I left again to get another water. I was sweating something awful, and I had to stay hydrated. An interesting fact I once heard was that some people die out in the desert with water still in the bottle. These people would try and conserve their water supply but would end up dehydrating themselves in the process, laughable over a few shots of whiskey but an important note at that. I drink nearly all I have and only saving a little to keep the mouth moist after a smoke and I find that by doing so I stay hydrated, never feeling like crap because the water hadn’t finished absorbing into my system. Remember that folks. When I finished watching the trains I found a place with a plug and wifi to jam out to music. I don’t know why I stopped listening to music like Bon Jovi, versus the same Trap music I had been listening to. Classic rock was the real me, not that stuff. Listening to it for hour rewired my brain into making myself remember what was good about me before I wrapped my head around nothing but stress, with a shot of confidence to boost my day. On the way to pick up a drink a woman and I crossed paths. Pretty attractive young woman who I never would’ve guessed was a hooker. “You got a smoke man?” “Yeah sure…” “You looking for a girl?” Instantly my mouth answered without using my brain. The thought of having a lady around for awhile would definitely make me happy. It had been a dry season for almost a year now. All of those articles about Hobos riding around with their lady filled my head with too much romanticism. “Hell yeah I’m looking for a baby…” “You ain’t got a cob do you?” (Misheard) “I ain’t got no mushroom baby I got something that’ll…” “Haha no no baby you ain’t a cop are you?” The wheels in my head began to turn. She's a sex worker. “Wha... don’t even insult me like that haha” At this point I knew getting some fruit wasn’t happening. “You got cash?” I knew I sound dumb just saying no, so I played dumb. “Oh wait, you is a… oh oh ugh… shit sorry I didn’t know. You don’t look the type you’re too beautiful.” Persuasion attempt failed :( “Aw oh my God thank you! Well thanks anyway honey you got another smoke?” It was the least I could do. At any rate I felt sorta proud to myself for holding a fluid conversation with a pretty lady like her for longer than ten seconds. Turns out, Bon Jovi cures depression. I made way to the store, it was full of like the whole fucking town. Turns out it was like this nearly every night, feeling good I decided to make conversation with the guy at the register. I was curious as to what happened to that other convenience store. Considering there was only two in the whole area, both in good spots, you wouldn’t think it would just go out of business. Nah something was off. When I asked he just said, “Stay away from there tonight one goes everyday.” Whoa. Anyway, to sum up yes I did eventually hop that train. Damn it got freezing. All that wind.I fell asleep and woke up to what I thought was a golden opportunity, a train station for people to actually ride. Mind you, before I tell you this, I had just woke up and that physics and pain part of my brain wasn’t turned on yet. The train was going about fifteen miles per hour, I figured you know… that I could just jump off into the gravel with grass right next to it, because you know I’ve done crazy shit before… I was totally complacent. And quoting an old coworker who ironically said, “In the marines they had signs in Iraq that said ‘Complacency kills’” and betting that I’d get shocked when I worked for a lighting company before anyone else. Well guess what? Next day this condescending mother fucker gets shocked a day and thrown off his ladder. Yeah he was okay, so I can say in good conscience KARMA BITCH! Anyway yeah it hurt when I landed. As soon as I hit the hit ground I fucked up my pinkie and hurt my knees. I got lucky. After about twenty seconds I got up and limped while laughing at myself out loud. I was just relieved that it was the only thing I did to myself. I limped around to see about getting myself onto a train to who the fuck cares where. I came across three white possibly english teenagers who were up to no good. They were vandalizing something they had paint, and wore all black. I talked to them for a minute to find out about the train station. Bad news. It wasn’t a train station but another yard. Fuuuuck. I felt so dumb. I checked my phone to see where I was at… the heart of Atlanta.

0 notes

Text

How to Exercise with An Autoimmune Condition

Autoimmune diseases really throw the body for a loop. You’re attacking your own tissues. Your inflammation is sky high. What’s usually good for you—like boosting the immune system—can make it worse. You’ll often restrict eating certain foods that, on paper, appear healthy and nutrient-dense. You take nothing for granted, measure and consider everything before eating or doing it. Sometimes it feels like almost everything has the potential to be a trigger.

Is it true for exercise, too? Must people with autoimmune diseases also change how they train?

First things first, exercise can help. You just have to do it right, or risk incurring the negative effects.

Don’t overtrain. Most autoimmune diseases are characterized by chronic inflammation. Anything that increases that inflammatory load, like too much exercise, will contribute. Overtraining—stressful exercise that you fail to recover from before exercising again—will increase your stress load and increase autoimmune symptoms.

Avoid exercise-induced leaky gut. Intense, protracted exercise—think 30-minute high-intensity metabolic workouts, long runs at race pace, 400 meter high intensity intervals—increases intestinal permeability. Elevated intestinal permeability has been linked to rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, and researchers think it may play a causative role in other autoimmune diseases too.

Yet not exercising might be even worse because exercise increases endorphins. Most think of endorphins purely as “feel-good” chemicals. They’re what the body pumps out to deal with pain, as a response to exercise, and it’s through the endorphin receptor system that exogenous opiates work. Endorphins also play an important role in immune function. Rather than “boost” or “diminish” it, endorphins regulate immunity. They keep it running smoothly. Without endorphins, the immune system begins misbehaving. Sound familiar?

Low-dose naltrexone is a promising therapy for multiple sclerosis and other autoimmune diseases. It works by increasing endorphin secretion, which in turn helps regulate the immune system’s misbehavior. I won’t posit that exercise is just as effective as LDN, but it’s certainly a piece of the puzzle.

This is the same relationship everyone has with exercise. Too much is bad, too little is bad, recovery is required, and intensity must be balanced with volume. The margin of error is just smaller when you have an autoimmune disease.

How should you exercise, then?

It depends on what type of autoimmune condition you have. Let’s explore some of the more common ones.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis hurts. It makes exercise a daunting prospect, which is why so many people with RA choose to stay inactive. Yet exercise consistently helps.

Exercise may improve sleep, reduce depression, and improve functionality in RA patients. Animal models of RA suggest that acute exercise inhibits the destruction of and even thickens cartilage.

What works:

Yoga works. A survey of RA patients found that many benefit from regular yoga practice. Another study found that it reduced pain, improved function, and increased general well-being in RA patients.

Light and very light intensity works. One study found that around 5 hours of “light and very light” intensity activity each day were often more effective at improving cardiovascular health in RA patients than 35 minutes of moderate intensity training each day. This isn’t necessarily unique to RA, as I think everyone’s better off walking and moving for 5 hours versus jogging for 30.

Working the afflicted joints works. For RA patients with hand and finger joint pain, a high-intensity exercise program centered on the hands improved functionality more than a low-intensity one.

High intensity works. 4 4-minute-long high intensity intervals on the bike at 85-95% of max HR increased muscle mass and cardio fitness while beginning to reduce inflammatory markers in women with RA. Notably, neither pain nor disease severity increased. In another study, RA patients were able to perform high-intensity resistance and aerobic training without issue.

Multiple Sclerosis

As with RA, people with multiple sclerosis really seem to benefit from exercise. They sleep better. If you start early, it may reduce the risk of developing MS. Exercise even drives brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is reduced in MS.

What works:

Tai chi works. Though the sample size was small, tai chi improved functional outcomes in patients with MS.

Both strength and endurance training work better than either alone. A 24-week lifting and endurance program has been used to increase BDNF in MS patients. A 12-week lifting and high-intensity interval program improved glucose tolerance in MS patients.

Lifting in the morning works. A recent study found that MS patients had more muscle fatigue and less muscle strength in the afternoon compared to the morning. Muscle oxidative capacity—the ability to burn fat during low level activity—did not differ between times.

Intense exercise works: The greater the intensity, the more BDNF you produce. That’s a general rule for everyone, and it’s no different for MS.

Crohn’s Disease

In Crohn’s, the body attacks the GI tract. It’s a bad one. Because Crohn’s can involve crippling GI pain, impaired digestion, fatigue, joint pain, and emergency diarrhea, patients often avoid exercise. They shouldn’t. If you can get past the mental roadblocks Crohn’s erects, exercise can really help.

What works:

Sprints and medium intensity both work, but sprints are less inflammatory. Both all-out cycling sprints (6 bouts of 4×15 second cycle sprints at 100% peak power output) and moderate cycling (30 minutes at 50% peak power) were well-tolerated by children with Crohn’s, but certain inflammatory markers were higher in the moderate group. Another inflammatory marker also stayed elevated for longer in the moderate group.

Resistance training and aerobic activity both work. Either alone or both in concert improve Crohn’s symptoms by modulating immune function.

Walking works. A low intensity walking program (just 3 times a week) improved quality of life in Crohn’s patients.

Type 1 Diabetes

People often forget about type 1 diabetes, but it’s an established autoimmune disease where the immune system attacks the pancreas and reduces or abolishes its ability to produce insulin. For type 1 diabetics who wish to reduce the amount of insulin they inject, exercise is essential.

It up-regulates insulin independent glucose uptake by the muscles. That removes the pancreas from the equation altogether, and it reduces the amount of exogenous insulin needed to process glucose.

It’s also safe, as long as you have your insulin therapy under control.

However, as high-intensity exercise tends to increase blood glucose and easy aerobic exercise decreases it in type 1 diabetics, you really need to have your ducks in a row. The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology journal recently published their consensus guidelines for safe exercise with type 1 diabetes, with the main takeaway being that diabetics should monitor their glucose levels before, during, and after training to ensure the numbers don’t get away from them. One study found that quickly giving a dose of insulin following high-intensity training counteracted the rise in blood glucose.

What works:

Combining resistance training with aerobic training works. The combination lowered insulin requirements and improved basically every marker of fitness, along with general well-being.

Resistance training works. In one study, resistance training seemed to lower blood glucose regardless of intensity. However, in one I mentioned above, subjects needed a dose of insulin following high-intensity resistance training to keep glucose under control. “Lift, but watch your glucose” appears to be the safe path forward.

Those are four of the most common and well-studied autoimmune diseases. Others may not have the same rich body of literature, but exercise probably helps there, too.

In Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients with normal thyroid hormone levels, for example, 6 months of aerobic training improved endothelial function.

Be careful with Graves disease, though.

Graves is an autoimmune hyperthyroid condition. Instead of underactive thyroids, Graves patients have overactive thyroids. There aren’t many trials on exercise in Graves patients, but there are some case studies that suggest some dangers.

In 2012, a Graves patient ended up with rhabdomyolysis (a terrible condition where you break down and pee out muscle tissue) after a non-strenuous exercise session.

Again in 2012, another patient with Graves got rhabdomyolysis after a session.

Euthyroid Graves patients—people with normal thyroid levels—can exercise safely, however. It improves functional capacity and delays relapse.

Again, be careful with Graves.

Because they’re so trepidatious about it and inactivity numbers are higher than the general population, most autoimmune disease patients would be better served with more exercise, not less. Autoimmune disease patients who loyally read MDA and other ancestral health blogs, however, might be the type to engage in CrossFit WODs and train really hard and rather excessively. If so, you might need less exercise, not more.

As I read the literature, autoimmune disease patients should be exercising in accordance with Primal Blueprint Fitness, albeit even more strictly:

Lift heavy and go intense, but keep it really brief. Low-volume, high-intensity. Short sprints, 3-5 rep sets, that sorta thing. Intensity is relative, so don’t think you have to squat your own bodyweight right away.

Spend most of your training currency on long, slow movements. Hikes, walks, gardening, gentle movement routines are your best friends. Basically anyone with an autoimmune disease can do these activities, and they always help.

Mobility training is required, especially in autoimmune diseases that affect the joints and connective tissues. If your joints are compromised, your other tissues have to be that much more limber, loose, and mobile. Try for something like VitaMoves or MobilityWOD.

Having an autoimmune disease doesn’t make you fragile. You can still train, and evidence shows that you can probably go harder than you think—provided you allow for ample recovery and keep a lid on how much training volume you accumulate.

Anyway, that’s my take on all this. I don’t have an autoimmune disease, though, so I’m only going on what the literature says. I’d love to hear from people who deal with autoimmune disease on a personal level. How do you exercise? What works? What doesn’t? What have you learned along the way?

Thanks for reading, everyone. Take care!

0 notes

Text

How to Exercise with An Autoimmune Condition

Autoimmune diseases really throw the body for a loop. You’re attacking your own tissues. Your inflammation is sky high. What’s usually good for you—like boosting the immune system—can make it worse. You’ll often restrict eating certain foods that, on paper, appear healthy and nutrient-dense. You take nothing for granted, measure and consider everything before eating or doing it. Sometimes it feels like almost everything has the potential to be a trigger.

Is it true for exercise, too? Must people with autoimmune diseases also change how they train?

First things first, exercise can help. You just have to do it right, or risk incurring the negative effects.

Don’t overtrain. Most autoimmune diseases are characterized by chronic inflammation. Anything that increases that inflammatory load, like too much exercise, will contribute. Overtraining—stressful exercise that you fail to recover from before exercising again—will increase your stress load and increase autoimmune symptoms.

Avoid exercise-induced leaky gut. Intense, protracted exercise—think 30-minute high-intensity metabolic workouts, long runs at race pace, 400 meter high intensity intervals—increases intestinal permeability. Elevated intestinal permeability has been linked to rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, and researchers think it may play a causative role in other autoimmune diseases too.

Yet not exercising might be even worse because exercise increases endorphins. Most think of endorphins purely as “feel-good” chemicals. They’re what the body pumps out to deal with pain, as a response to exercise, and it’s through the endorphin receptor system that exogenous opiates work. Endorphins also play an important role in immune function. Rather than “boost” or “diminish” it, endorphins regulate immunity. They keep it running smoothly. Without endorphins, the immune system begins misbehaving. Sound familiar?

Low-dose naltrexone is a promising therapy for multiple sclerosis and other autoimmune diseases. It works by increasing endorphin secretion, which in turn helps regulate the immune system’s misbehavior. I won’t posit that exercise is just as effective as LDN, but it’s certainly a piece of the puzzle.

This is the same relationship everyone has with exercise. Too much is bad, too little is bad, recovery is required, and intensity must be balanced with volume. The margin of error is just smaller when you have an autoimmune disease.

How should you exercise, then?

It depends on what type of autoimmune condition you have. Let’s explore some of the more common ones.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis hurts. It makes exercise a daunting prospect, which is why so many people with RA choose to stay inactive. Yet exercise consistently helps.

Exercise may improve sleep, reduce depression, and improve functionality in RA patients. Animal models of RA suggest that acute exercise inhibits the destruction of and even thickens cartilage.

What works:

Yoga works. A survey of RA patients found that many benefit from regular yoga practice. Another study found that it reduced pain, improved function, and increased general well-being in RA patients.

Light and very light intensity works. One study found that around 5 hours of “light and very light” intensity activity each day were often more effective at improving cardiovascular health in RA patients than 35 minutes of moderate intensity training each day. This isn’t necessarily unique to RA, as I think everyone’s better off walking and moving for 5 hours versus jogging for 30.

Working the afflicted joints works. For RA patients with hand and finger joint pain, a high-intensity exercise program centered on the hands improved functionality more than a low-intensity one.

High intensity works. 4 4-minute-long high intensity intervals on the bike at 85-95% of max HR increased muscle mass and cardio fitness while beginning to reduce inflammatory markers in women with RA. Notably, neither pain nor disease severity increased. In another study, RA patients were able to perform high-intensity resistance and aerobic training without issue.

Multiple Sclerosis

As with RA, people with multiple sclerosis really seem to benefit from exercise. They sleep better. If you start early, it may reduce the risk of developing MS. Exercise even drives brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is reduced in MS.

What works:

Tai chi works. Though the sample size was small, tai chi improved functional outcomes in patients with MS.

Both strength and endurance training work better than either alone. A 24-week lifting and endurance program has been used to increase BDNF in MS patients. A 12-week lifting and high-intensity interval program improved glucose tolerance in MS patients.

Lifting in the morning works. A recent study found that MS patients had more muscle fatigue and less muscle strength in the afternoon compared to the morning. Muscle oxidative capacity—the ability to burn fat during low level activity—did not differ between times.

Intense exercise works: The greater the intensity, the more BDNF you produce. That’s a general rule for everyone, and it’s no different for MS.

Crohn’s Disease

In Crohn’s, the body attacks the GI tract. It’s a bad one. Because Crohn’s can involve crippling GI pain, impaired digestion, fatigue, joint pain, and emergency diarrhea, patients often avoid exercise. They shouldn’t. If you can get past the mental roadblocks Crohn’s erects, exercise can really help.

What works:

Sprints and medium intensity both work, but sprints are less inflammatory. Both all-out cycling sprints (6 bouts of 4×15 second cycle sprints at 100% peak power output) and moderate cycling (30 minutes at 50% peak power) were well-tolerated by children with Crohn’s, but certain inflammatory markers were higher in the moderate group. Another inflammatory marker also stayed elevated for longer in the moderate group.

Resistance training and aerobic activity both work. Either alone or both in concert improve Crohn’s symptoms by modulating immune function.

Walking works. A low intensity walking program (just 3 times a week) improved quality of life in Crohn’s patients.

Type 1 Diabetes

People often forget about type 1 diabetes, but it’s an established autoimmune disease where the immune system attacks the pancreas and reduces or abolishes its ability to produce insulin. For type 1 diabetics who wish to reduce the amount of insulin they inject, exercise is essential.

It up-regulates insulin independent glucose uptake by the muscles. That removes the pancreas from the equation altogether, and it reduces the amount of exogenous insulin needed to process glucose.

It’s also safe, as long as you have your insulin therapy under control.

However, as high-intensity exercise tends to increase blood glucose and easy aerobic exercise decreases it in type 1 diabetics, you really need to have your ducks in a row. The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology journal recently published their consensus guidelines for safe exercise with type 1 diabetes, with the main takeaway being that diabetics should monitor their glucose levels before, during, and after training to ensure the numbers don’t get away from them. One study found that quickly giving a dose of insulin following high-intensity training counteracted the rise in blood glucose.

What works:

Combining resistance training with aerobic training works. The combination lowered insulin requirements and improved basically every marker of fitness, along with general well-being.

Resistance training works. In one study, resistance training seemed to lower blood glucose regardless of intensity. However, in one I mentioned above, subjects needed a dose of insulin following high-intensity resistance training to keep glucose under control. “Lift, but watch your glucose” appears to be the safe path forward.

Those are four of the most common and well-studied autoimmune diseases. Others may not have the same rich body of literature, but exercise probably helps there, too.

In Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients with normal thyroid hormone levels, for example, 6 months of aerobic training improved endothelial function.

Be careful with Graves disease, though.

Graves is an autoimmune hyperthyroid condition. Instead of underactive thyroids, Graves patients have overactive thyroids. There aren’t many trials on exercise in Graves patients, but there are some case studies that suggest some dangers.

In 2012, a Graves patient ended up with rhabdomyolysis (a terrible condition where you break down and pee out muscle tissue) after a non-strenuous exercise session.

Again in 2012, another patient with Graves got rhabdomyolysis after a session.

Euthyroid Graves patients—people with normal thyroid levels—can exercise safely, however. It improves functional capacity and delays relapse.

Again, be careful with Graves.

Because they’re so trepidatious about it and inactivity numbers are higher than the general population, most autoimmune disease patients would be better served with more exercise, not less. Autoimmune disease patients who loyally read MDA and other ancestral health blogs, however, might be the type to engage in CrossFit WODs and train really hard and rather excessively. If so, you might need less exercise, not more.

As I read the literature, autoimmune disease patients should be exercising in accordance with Primal Blueprint Fitness, albeit even more strictly:

Lift heavy and go intense, but keep it really brief. Low-volume, high-intensity. Short sprints, 3-5 rep sets, that sorta thing. Intensity is relative, so don’t think you have to squat your own bodyweight right away.

Spend most of your training currency on long, slow movements. Hikes, walks, gardening, gentle movement routines are your best friends. Basically anyone with an autoimmune disease can do these activities, and they always help.

Mobility training is required, especially in autoimmune diseases that affect the joints and connective tissues. If your joints are compromised, your other tissues have to be that much more limber, loose, and mobile. Try for something like VitaMoves or MobilityWOD.

Having an autoimmune disease doesn’t make you fragile. You can still train, and evidence shows that you can probably go harder than you think—provided you allow for ample recovery and keep a lid on how much training volume you accumulate.

Anyway, that’s my take on all this. I don’t have an autoimmune disease, though, so I’m only going on what the literature says. I’d love to hear from people who deal with autoimmune disease on a personal level. How do you exercise? What works? What doesn’t? What have you learned along the way?

Thanks for reading, everyone. Take care!

0 notes

Text

How to Exercise with An Autoimmune Condition

Autoimmune diseases really throw the body for a loop. You’re attacking your own tissues. Your inflammation is sky high. What’s usually good for you—like boosting the immune system—can make it worse. You’ll often restrict eating certain foods that, on paper, appear healthy and nutrient-dense. You take nothing for granted, measure and consider everything before eating or doing it. Sometimes it feels like almost everything has the potential to be a trigger.

Is it true for exercise, too? Must people with autoimmune diseases also change how they train?

First things first, exercise can help. You just have to do it right, or risk incurring the negative effects.

Don’t overtrain. Most autoimmune diseases are characterized by chronic inflammation. Anything that increases that inflammatory load, like too much exercise, will contribute. Overtraining—stressful exercise that you fail to recover from before exercising again—will increase your stress load and increase autoimmune symptoms.

Avoid exercise-induced leaky gut. Intense, protracted exercise—think 30-minute high-intensity metabolic workouts, long runs at race pace, 400 meter high intensity intervals—increases intestinal permeability. Elevated intestinal permeability has been linked to rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, and researchers think it may play a causative role in other autoimmune diseases too.

Yet not exercising might be even worse because exercise increases endorphins. Most think of endorphins purely as “feel-good” chemicals. They’re what the body pumps out to deal with pain, as a response to exercise, and it’s through the endorphin receptor system that exogenous opiates work. Endorphins also play an important role in immune function. Rather than “boost” or “diminish” it, endorphins regulate immunity. They keep it running smoothly. Without endorphins, the immune system begins misbehaving. Sound familiar?

Low-dose naltrexone is a promising therapy for multiple sclerosis and other autoimmune diseases. It works by increasing endorphin secretion, which in turn helps regulate the immune system’s misbehavior. I won’t posit that exercise is just as effective as LDN, but it’s certainly a piece of the puzzle.

This is the same relationship everyone has with exercise. Too much is bad, too little is bad, recovery is required, and intensity must be balanced with volume. The margin of error is just smaller when you have an autoimmune disease.

How should you exercise, then?

It depends on what type of autoimmune condition you have. Let’s explore some of the more common ones.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis hurts. It makes exercise a daunting prospect, which is why so many people with RA choose to stay inactive. Yet exercise consistently helps.

Exercise may improve sleep, reduce depression, and improve functionality in RA patients. Animal models of RA suggest that acute exercise inhibits the destruction of and even thickens cartilage.

What works:

Yoga works. A survey of RA patients found that many benefit from regular yoga practice. Another study found that it reduced pain, improved function, and increased general well-being in RA patients.

Light and very light intensity works. One study found that around 5 hours of “light and very light” intensity activity each day were often more effective at improving cardiovascular health in RA patients than 35 minutes of moderate intensity training each day. This isn’t necessarily unique to RA, as I think everyone’s better off walking and moving for 5 hours versus jogging for 30.

Working the afflicted joints works. For RA patients with hand and finger joint pain, a high-intensity exercise program centered on the hands improved functionality more than a low-intensity one.

High intensity works. 4 4-minute-long high intensity intervals on the bike at 85-95% of max HR increased muscle mass and cardio fitness while beginning to reduce inflammatory markers in women with RA. Notably, neither pain nor disease severity increased. In another study, RA patients were able to perform high-intensity resistance and aerobic training without issue.

Multiple Sclerosis

As with RA, people with multiple sclerosis really seem to benefit from exercise. They sleep better. If you start early, it may reduce the risk of developing MS. Exercise even drives brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is reduced in MS.

What works:

Tai chi works. Though the sample size was small, tai chi improved functional outcomes in patients with MS.

Both strength and endurance training work better than either alone. A 24-week lifting and endurance program has been used to increase BDNF in MS patients. A 12-week lifting and high-intensity interval program improved glucose tolerance in MS patients.

Lifting in the morning works. A recent study found that MS patients had more muscle fatigue and less muscle strength in the afternoon compared to the morning. Muscle oxidative capacity—the ability to burn fat during low level activity—did not differ between times.

Intense exercise works: The greater the intensity, the more BDNF you produce. That’s a general rule for everyone, and it’s no different for MS.

Crohn’s Disease

In Crohn’s, the body attacks the GI tract. It’s a bad one. Because Crohn’s can involve crippling GI pain, impaired digestion, fatigue, joint pain, and emergency diarrhea, patients often avoid exercise. They shouldn’t. If you can get past the mental roadblocks Crohn’s erects, exercise can really help.

What works:

Sprints and medium intensity both work, but sprints are less inflammatory. Both all-out cycling sprints (6 bouts of 4×15 second cycle sprints at 100% peak power output) and moderate cycling (30 minutes at 50% peak power) were well-tolerated by children with Crohn’s, but certain inflammatory markers were higher in the moderate group. Another inflammatory marker also stayed elevated for longer in the moderate group.

Resistance training and aerobic activity both work. Either alone or both in concert improve Crohn’s symptoms by modulating immune function.

Walking works. A low intensity walking program (just 3 times a week) improved quality of life in Crohn’s patients.

Type 1 Diabetes

People often forget about type 1 diabetes, but it’s an established autoimmune disease where the immune system attacks the pancreas and reduces or abolishes its ability to produce insulin. For type 1 diabetics who wish to reduce the amount of insulin they inject, exercise is essential.

It up-regulates insulin independent glucose uptake by the muscles. That removes the pancreas from the equation altogether, and it reduces the amount of exogenous insulin needed to process glucose.

It’s also safe, as long as you have your insulin therapy under control.

However, as high-intensity exercise tends to increase blood glucose and easy aerobic exercise decreases it in type 1 diabetics, you really need to have your ducks in a row. The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology journal recently published their consensus guidelines for safe exercise with type 1 diabetes, with the main takeaway being that diabetics should monitor their glucose levels before, during, and after training to ensure the numbers don’t get away from them. One study found that quickly giving a dose of insulin following high-intensity training counteracted the rise in blood glucose.

What works:

Combining resistance training with aerobic training works. The combination lowered insulin requirements and improved basically every marker of fitness, along with general well-being.

Resistance training works. In one study, resistance training seemed to lower blood glucose regardless of intensity. However, in one I mentioned above, subjects needed a dose of insulin following high-intensity resistance training to keep glucose under control. “Lift, but watch your glucose” appears to be the safe path forward.

Those are four of the most common and well-studied autoimmune diseases. Others may not have the same rich body of literature, but exercise probably helps there, too.

In Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients with normal thyroid hormone levels, for example, 6 months of aerobic training improved endothelial function.

Be careful with Graves disease, though.

Graves is an autoimmune hyperthyroid condition. Instead of underactive thyroids, Graves patients have overactive thyroids. There aren’t many trials on exercise in Graves patients, but there are some case studies that suggest some dangers.

In 2012, a Graves patient ended up with rhabdomyolysis (a terrible condition where you break down and pee out muscle tissue) after a non-strenuous exercise session.

Again in 2012, another patient with Graves got rhabdomyolysis after a session.

Euthyroid Graves patients—people with normal thyroid levels—can exercise safely, however. It improves functional capacity and delays relapse.

Again, be careful with Graves.

Because they’re so trepidatious about it and inactivity numbers are higher than the general population, most autoimmune disease patients would be better served with more exercise, not less. Autoimmune disease patients who loyally read MDA and other ancestral health blogs, however, might be the type to engage in CrossFit WODs and train really hard and rather excessively. If so, you might need less exercise, not more.

As I read the literature, autoimmune disease patients should be exercising in accordance with Primal Blueprint Fitness, albeit even more strictly:

Lift heavy and go intense, but keep it really brief. Low-volume, high-intensity. Short sprints, 3-5 rep sets, that sorta thing. Intensity is relative, so don’t think you have to squat your own bodyweight right away.

Spend most of your training currency on long, slow movements. Hikes, walks, gardening, gentle movement routines are your best friends. Basically anyone with an autoimmune disease can do these activities, and they always help.

Mobility training is required, especially in autoimmune diseases that affect the joints and connective tissues. If your joints are compromised, your other tissues have to be that much more limber, loose, and mobile. Try for something like VitaMoves or MobilityWOD.

Having an autoimmune disease doesn’t make you fragile. You can still train, and evidence shows that you can probably go harder than you think—provided you allow for ample recovery and keep a lid on how much training volume you accumulate.

Anyway, that’s my take on all this. I don’t have an autoimmune disease, though, so I’m only going on what the literature says. I’d love to hear from people who deal with autoimmune disease on a personal level. How do you exercise? What works? What doesn’t? What have you learned along the way?

Thanks for reading, everyone. Take care!

0 notes

Text

How to Exercise with An Autoimmune Condition

Autoimmune diseases really throw the body for a loop. You’re attacking your own tissues. Your inflammation is sky high. What’s usually good for you—like boosting the immune system—can make it worse. You’ll often restrict eating certain foods that, on paper, appear healthy and nutrient-dense. You take nothing for granted, measure and consider everything before eating or doing it. Sometimes it feels like almost everything has the potential to be a trigger.

Is it true for exercise, too? Must people with autoimmune diseases also change how they train?

First things first, exercise can help. You just have to do it right, or risk incurring the negative effects.

Don’t overtrain. Most autoimmune diseases are characterized by chronic inflammation. Anything that increases that inflammatory load, like too much exercise, will contribute. Overtraining—stressful exercise that you fail to recover from before exercising again—will increase your stress load and increase autoimmune symptoms.

Avoid exercise-induced leaky gut. Intense, protracted exercise—think 30-minute high-intensity metabolic workouts, long runs at race pace, 400 meter high intensity intervals—increases intestinal permeability. Elevated intestinal permeability has been linked to rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, and researchers think it may play a causative role in other autoimmune diseases too.

Yet not exercising might be even worse because exercise increases endorphins. Most think of endorphins purely as “feel-good” chemicals. They’re what the body pumps out to deal with pain, as a response to exercise, and it’s through the endorphin receptor system that exogenous opiates work. Endorphins also play an important role in immune function. Rather than “boost” or “diminish” it, endorphins regulate immunity. They keep it running smoothly. Without endorphins, the immune system begins misbehaving. Sound familiar?

Low-dose naltrexone is a promising therapy for multiple sclerosis and other autoimmune diseases. It works by increasing endorphin secretion, which in turn helps regulate the immune system’s misbehavior. I won’t posit that exercise is just as effective as LDN, but it’s certainly a piece of the puzzle.

This is the same relationship everyone has with exercise. Too much is bad, too little is bad, recovery is required, and intensity must be balanced with volume. The margin of error is just smaller when you have an autoimmune disease.

How should you exercise, then?

It depends on what type of autoimmune condition you have. Let’s explore some of the more common ones.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis hurts. It makes exercise a daunting prospect, which is why so many people with RA choose to stay inactive. Yet exercise consistently helps.

Exercise may improve sleep, reduce depression, and improve functionality in RA patients. Animal models of RA suggest that acute exercise inhibits the destruction of and even thickens cartilage.

What works:

Yoga works. A survey of RA patients found that many benefit from regular yoga practice. Another study found that it reduced pain, improved function, and increased general well-being in RA patients.

Light and very light intensity works. One study found that around 5 hours of “light and very light” intensity activity each day were often more effective at improving cardiovascular health in RA patients than 35 minutes of moderate intensity training each day. This isn’t necessarily unique to RA, as I think everyone’s better off walking and moving for 5 hours versus jogging for 30.

Working the afflicted joints works. For RA patients with hand and finger joint pain, a high-intensity exercise program centered on the hands improved functionality more than a low-intensity one.

High intensity works. 4 4-minute-long high intensity intervals on the bike at 85-95% of max HR increased muscle mass and cardio fitness while beginning to reduce inflammatory markers in women with RA. Notably, neither pain nor disease severity increased. In another study, RA patients were able to perform high-intensity resistance and aerobic training without issue.

Multiple Sclerosis

As with RA, people with multiple sclerosis really seem to benefit from exercise. They sleep better. If you start early, it may reduce the risk of developing MS. Exercise even drives brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is reduced in MS.

What works:

Tai chi works. Though the sample size was small, tai chi improved functional outcomes in patients with MS.

Both strength and endurance training work better than either alone. A 24-week lifting and endurance program has been used to increase BDNF in MS patients. A 12-week lifting and high-intensity interval program improved glucose tolerance in MS patients.

Lifting in the morning works. A recent study found that MS patients had more muscle fatigue and less muscle strength in the afternoon compared to the morning. Muscle oxidative capacity—the ability to burn fat during low level activity—did not differ between times.

Intense exercise works: The greater the intensity, the more BDNF you produce. That’s a general rule for everyone, and it’s no different for MS.

Crohn’s Disease

In Crohn’s, the body attacks the GI tract. It’s a bad one. Because Crohn’s can involve crippling GI pain, impaired digestion, fatigue, joint pain, and emergency diarrhea, patients often avoid exercise. They shouldn’t. If you can get past the mental roadblocks Crohn’s erects, exercise can really help.

What works:

Sprints and medium intensity both work, but sprints are less inflammatory. Both all-out cycling sprints (6 bouts of 4×15 second cycle sprints at 100% peak power output) and moderate cycling (30 minutes at 50% peak power) were well-tolerated by children with Crohn’s, but certain inflammatory markers were higher in the moderate group. Another inflammatory marker also stayed elevated for longer in the moderate group.

Resistance training and aerobic activity both work. Either alone or both in concert improve Crohn’s symptoms by modulating immune function.

Walking works. A low intensity walking program (just 3 times a week) improved quality of life in Crohn’s patients.

Type 1 Diabetes

People often forget about type 1 diabetes, but it’s an established autoimmune disease where the immune system attacks the pancreas and reduces or abolishes its ability to produce insulin. For type 1 diabetics who wish to reduce the amount of insulin they inject, exercise is essential.

It up-regulates insulin independent glucose uptake by the muscles. That removes the pancreas from the equation altogether, and it reduces the amount of exogenous insulin needed to process glucose.

It’s also safe, as long as you have your insulin therapy under control.

However, as high-intensity exercise tends to increase blood glucose and easy aerobic exercise decreases it in type 1 diabetics, you really need to have your ducks in a row. The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology journal recently published their consensus guidelines for safe exercise with type 1 diabetes, with the main takeaway being that diabetics should monitor their glucose levels before, during, and after training to ensure the numbers don’t get away from them. One study found that quickly giving a dose of insulin following high-intensity training counteracted the rise in blood glucose.

What works:

Combining resistance training with aerobic training works. The combination lowered insulin requirements and improved basically every marker of fitness, along with general well-being.

Resistance training works. In one study, resistance training seemed to lower blood glucose regardless of intensity. However, in one I mentioned above, subjects needed a dose of insulin following high-intensity resistance training to keep glucose under control. “Lift, but watch your glucose” appears to be the safe path forward.

Those are four of the most common and well-studied autoimmune diseases. Others may not have the same rich body of literature, but exercise probably helps there, too.

In Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients with normal thyroid hormone levels, for example, 6 months of aerobic training improved endothelial function.

Be careful with Graves disease, though.

Graves is an autoimmune hyperthyroid condition. Instead of underactive thyroids, Graves patients have overactive thyroids. There aren’t many trials on exercise in Graves patients, but there are some case studies that suggest some dangers.

In 2012, a Graves patient ended up with rhabdomyolysis (a terrible condition where you break down and pee out muscle tissue) after a non-strenuous exercise session.

Again in 2012, another patient with Graves got rhabdomyolysis after a session.

Euthyroid Graves patients—people with normal thyroid levels—can exercise safely, however. It improves functional capacity and delays relapse.

Again, be careful with Graves.

Because they’re so trepidatious about it and inactivity numbers are higher than the general population, most autoimmune disease patients would be better served with more exercise, not less. Autoimmune disease patients who loyally read MDA and other ancestral health blogs, however, might be the type to engage in CrossFit WODs and train really hard and rather excessively. If so, you might need less exercise, not more.

As I read the literature, autoimmune disease patients should be exercising in accordance with Primal Blueprint Fitness, albeit even more strictly:

Lift heavy and go intense, but keep it really brief. Low-volume, high-intensity. Short sprints, 3-5 rep sets, that sorta thing. Intensity is relative, so don’t think you have to squat your own bodyweight right away.

Spend most of your training currency on long, slow movements. Hikes, walks, gardening, gentle movement routines are your best friends. Basically anyone with an autoimmune disease can do these activities, and they always help.

Mobility training is required, especially in autoimmune diseases that affect the joints and connective tissues. If your joints are compromised, your other tissues have to be that much more limber, loose, and mobile. Try for something like VitaMoves or MobilityWOD.

Having an autoimmune disease doesn’t make you fragile. You can still train, and evidence shows that you can probably go harder than you think—provided you allow for ample recovery and keep a lid on how much training volume you accumulate.

Anyway, that’s my take on all this. I don’t have an autoimmune disease, though, so I’m only going on what the literature says. I’d love to hear from people who deal with autoimmune disease on a personal level. How do you exercise? What works? What doesn’t? What have you learned along the way?

Thanks for reading, everyone. Take care!

0 notes