#one google search in curiosity led me down quite a rabbit hole

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

On today's "I am SO not normal about Dead Friend Forever": Discussing Catholicism and Colonization in this gay Thai slasher series

Some background on me: I am from a Latine Catholic family. Raised as a non-practicing Catholic (we didn't go to church or pray). Then my parents enrolled me in a Catholic school that I attended from 5th grade to the end of 7th grade. Today, I am not Catholic and have never really considered myself as such.

Ok, so in the flashback episodes of DFF, I have been noticing a lot of things. My findings under the cut.

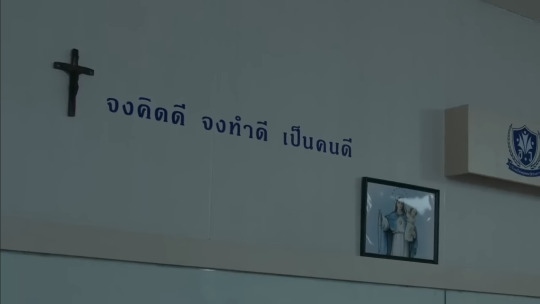

Let's start with this crucifix and photo of the Virgin Mary and a baby Jesus.

Screenshot from ep. 5.

The camera lingers here a bit so we're obviously meant to pay attention to the phrase. I put the screenshot through Google translate's image translator and the translation it gave me was, "Think good, do good, be a good person." I didn't think much of it when I first watched the episode other than it was supposed to establish that the boys attend a Christian or Catholic school.

But then there was this image posted on Be On Cloud's Instagram (also from ep. 5): X

Zooming in, we can see there's another picture of Mary in the background. Watching the classroom scenes, it's easy to miss because the series itself is more washed out than the official photos posted. But this emphasis on Mary led me to believe the school is a Catholic one. So out of curiosity, I looked up the schools the writers and directors attended because I felt I was onto something here. And boy, was I!

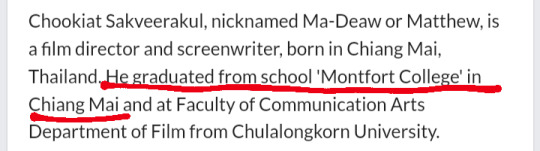

Source: MDL

Ma-Deaw, if you didn't know, is one of the directors of Dead Friend Forever (he also directed Manner of Death and Inhuman Kiss , and lots of other things).

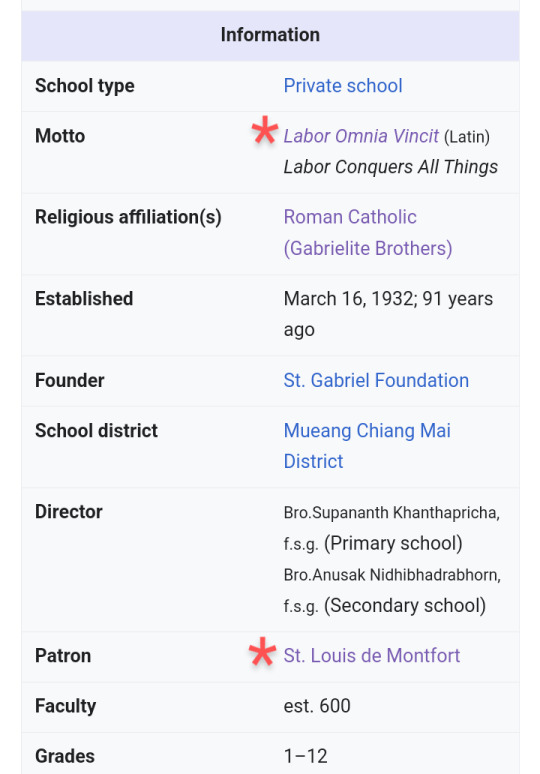

One Google search later (X) and I learned "Montfort College" is a Catholic school. It started out as a primary school that later added a secondary school as well.

Now let's take a closer look at some of the details of this school:

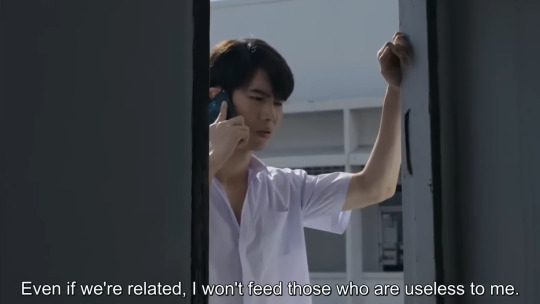

First, the school's motto "Labor Conquers All Things". This reminded me of the phone conversation Tee had with his uncle:

On my first watch, this sounded familiar to me but I couldn't really place why. It wasn't until I saw this other Tumblr post (X) that pointed out it's similar to a bible quote from the New Testament. The quote varies a bit depending on which version of the bible you're using but it's along the lines of, "He who does not work, neither shall he eat".

This is meant to discourage "laziness". Nevermind the fact that people deserve to eat simply because we get hungry and need food to survive. The idea that we only "deserve" things based on productivity is an extremely colonial one. — Reminder also that Tee is being forced into this "work" in the first place. He's just a high school kid. I don't need to like his character to understand how fucked up his situation is.

Then there's the patron of the school. St. Louis de Montfort was a French Catholic priest most known for his study in Mariology. What is Mariology (X)? The study of Mary, the mother of Jesus. I didn't know that was a thing but it's unsurprising considering how prominent images of Mary were in my own religious upbringing. And she's what started me down this rabbit hole in the first place. Mary is a big deal to the Catholics. I'm going to be paying even more attention now if more Mary imagery pops up.

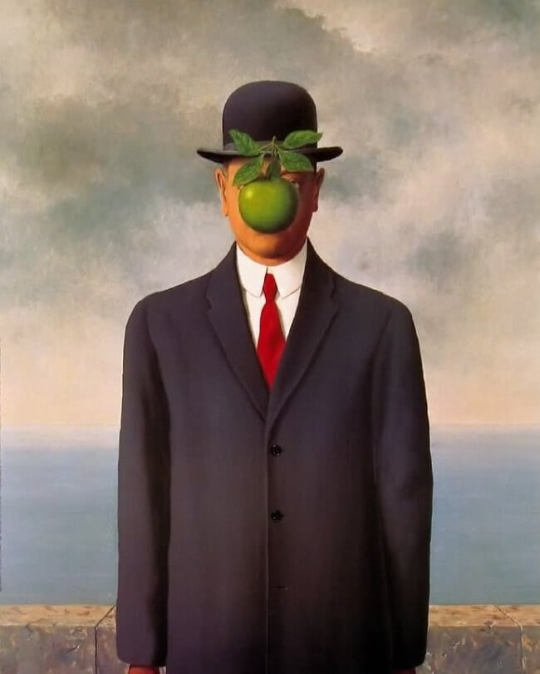

The Garden of Eden and Original Sin

Now I want to draw attention to these images:

Screenshots from ep. 7

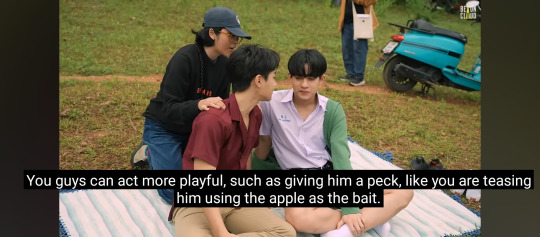

Here we have Non and Phee biting into an apple as they leisure around this lush green field. We know they've visited this location more than once because they're wearing different outfits in the screenshots. And I think it's important to note that it's Phee holding the apple and offering it to Non.

The use of the word "bait" in the bts of ep. 7 is quite interesting too. (X)

The Garden of Eden was the paradise in which Adam and Eve resided. In this garden, there were many trees to eat from. The one tree Adam and Eve were forbidden by God to eat from was the Tree of Knowledge. A serpent (Satan), first tempted Eve into taking from the tree to eat it's fruit. And then Eve gave the fruit to Adam. That is Original Sin. And because Adam and Eve ate from the Tree of Knowledge, all humans thereafter are born sinful and bad, and can only find salvation through God.

Of course in the scene between Phee and Non, the sin the apple represents is being gay. And it's after this, and after the bracelet scene, that Non becomes involved with Por's film and his tragedy begins.

Zoomed in screenshot from ep. 5

And I wonder if the bracelet scene is the last time Phee and Non visit this forest location. It would parallel how Adam and Eve were cast out of the Garden of Eden once they sinned.

Final Thoughts

You give me a story that criticizes Western religion and how it's used as a tool for oppression and colonization, and I'm gonna eat that shit up. I am gonna eat it up. Every. Single. Time.

I really wasn't expecting anything like this from Dead Friend Forever. This level in attention to detail is unmatched. I don't think I've watched a more well planned out show. And no matter where DFF goes from here, these seven episodes will always hold a special place in my heart. 💗

#dead friend forever#dff the series#pheenon#barcode tinnasit#ta nannakun#dff meta#dff spoilers#tabarcode#dff*#*#i just love it here#this is my comfort show idc

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

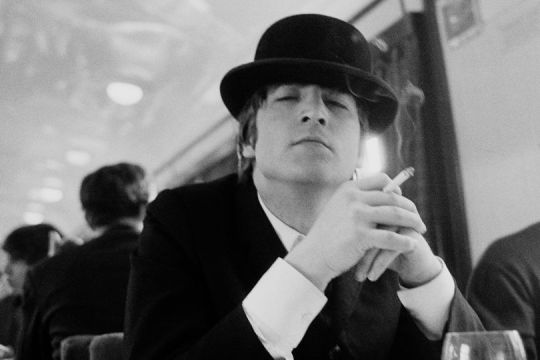

The Saga of the Bowler Hat: In Four Acts

Sep 30-Oct 15, 1961: Paris trip

We planned to hitchhike to Spain. I had done a spot of hitchhiking with George and we knew you had to have a gimmick; we had been turned down so often and we’d seen that guys that had a gimmick (like a Union Jack round them) had always got the lifts. So I said to John, ‘Let’s get a couple of bowler hats.’ It was showbiz creeping in.

Gustafson happened to bump into them the day they left, Saturday September 30. “They both had bowler hats on, with the usual leather jackets and jeans. They said they were off to Paris, so I walked down to Lime Street station with them and watched them go. They were an incredible pair: always great fun, irreverent, and so close.” [x]

We still had our leather jackets and drainpipes – we were too proud of them not to wear them, in case we met a girl; and if we did meet a girl, off would come the bowlers. But for lifts we would put the bowlers on. Two guys in bowler hats – a lorry would stop! Sense of Humour. This, and the train, is how we got to Paris. [x]

March 2-4, 1964: Filming A Hard Day’s Night train scene

The specially-hired train was destined for Minehead and back, where for the next three days scenes were filmed in the suitably cramped setting. There was a dining car for The Beatles to eat in...[their] dialogue was recorded using microphones hidden inside their shirts, but numerous retakes were required due to sound problems.

The first we did was the train, which we were all dead nervous in. Practically the whole of the train bit we were going to pieces.

I’m sure it’s less noticeable to people watching in the cinema, but we know that we’re dead conscious in every move we make, we watch each other. Paul’s embarrassed when I’m watching him speak and he knows I am. [x]

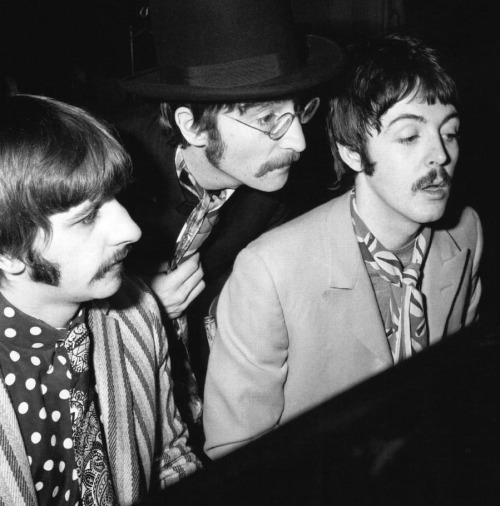

March 29, 1967: With A Little Help From My Friends day

At two o’clock in the afternoon John arrived at Paul’s house in St. John’s Wood. They both went up to Paul’s workroom at the top of the house...John started playing his guitar and Paul started banging on his piano. For a couple of hours they both banged away. Each seemed to be in a trance until the other came up with something good, then he would pluck it out of a mass of noises and try it himself. They’d already established the tune the previous afternoon. Now they were trying to polish up the melody and think of some words to go with it.

“Are you afraid when you turn out the light,” sang John. Paul sang it after him and nodded that it was good. John said they could use that idea for all the verses, if they could think of some more questions on those lines.

“Do you believe in love at first sight,” sang John. “No,” he said, stopping singing. “It hasn’t got the right number of syllables. What do you think? Can we split it up and have a pause to give it an extra syllable?”

John then sang the line, breaking it in the middle: “Do you believe—ugh—in love at first sight.”

“How about,” said Paul, “Do you believe in a love at first sight.”

John sang it over and accepted it. In singing it, he added the next line, “Yes, I’m certain it happens all the time.”

They both then sang the two lines to themselves, la-la-ing all the other lines. Apart from this, all they had was the chorus: “I’ll get by with a little help from my friends.” John found himself singing “Would you believe,” which he thought was better.

Then they changed the order, singing the two lines “Would you believe in a love at first sight/Yes I’m certain it happens all the time” before going on to “Are you afraid when you turn out the light,” but they still had to la-la the fourth line, which they couldn’t think of.

It was now about five o’clock. [x]

The Beatles began by recording the rhythm track in 10 takes, the last of which was the best. It had Paul McCartney on piano on track one, George Harrison’s rhythm guitar on two, Starr’s drums and cowbell played by John Lennon on three, and George Martin playing organ on track four.

A reduction mix, numbered take 11, made free some space on the tape for further overdubs. Starr then added his lead vocals to tracks three and four, with backing vocals by Lennon, McCartney and Harrison. This session ended at 5.45am, and recording for the song was completed on the following day. [x]

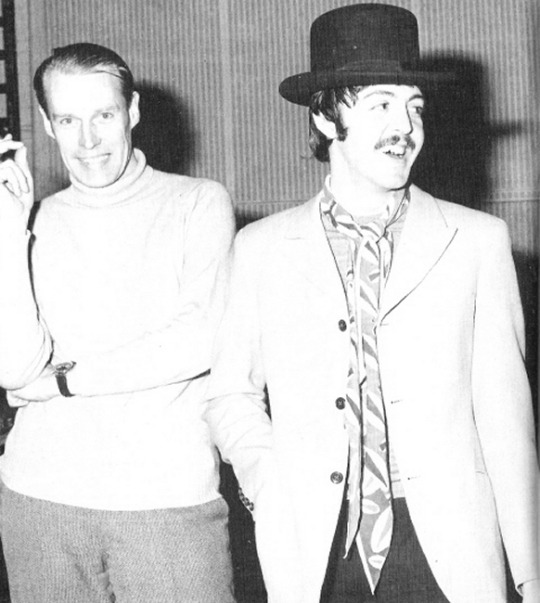

1967-1968: Paul’s favorite artist inspires Apple Corp name and logo

We were discovering Magritte in the sixties, just through magazines and things. And we just loved his sense of humour. And when we heard that he was a very ordinary bloke who used to paint from nine to one o'clock, and with his bowler hat, it became even more intriguing.

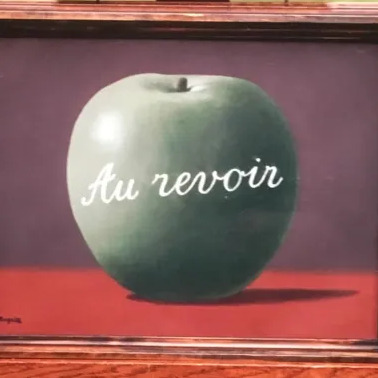

René Magritte, The Son of Man (1964)

One day [Robert Fraser] brought this painting to my house. We were out in the garden, it was a summer's day. And he didn't want to disturb us, I think we were filming or something. So he left this picture of Magritte. It was an apple - and he just left it on the dining room table and he went. It just had written across it "Au revoir", on this beautiful green apple...So it was like wow! What a great conceptual thing to do, you know. And this big green apple, which I still have now, became the inspiration for the logo. And then we decided to cut it in half for the B-side!

René Magritte, Le Jeu de Mourre [The Game of Mora] (1966)

The title was found by Magritte's friend, the Belgian poet Louis Scutenaire, and is probably a play of words on Les Jeunes Amours [Young Love] (1963), the title of a work by Magritte showing three apples. The game of mora is "a game in which one of the players rapidly displays a hand with some fingers raised, the others folded inwards, while his opponent calls out a number, which, for him to win, has to correspond to the total of the raised fingers.” [x]

Epilogue

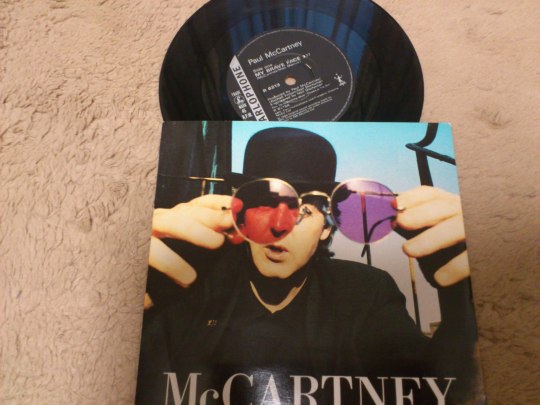

Paul McCartney’s 1989 My Brave Face single cover

My Brave Face lyrics, written early 1988 with Elvis Costello

January 1988: The Beatles are inducted in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

#bowler hat#john and paul#mclennon#blaming friendodorothys tags for this#one google search in curiosity led me down quite a rabbit hole#i had no idea how deep the bowler hat thing went#but MLH did as shown in his j&p fanfic#theres two bowler hats in paris but fairly sure both AHDN and mar 67 are pure hat stealing#fashion accessory stealing is paul's equivalent of a hair twirl#also that game of mora thing is nuts do click the links#im now convinced that apple painting is cursed#violating my 1980s dont exist here rule :(#only because i realized the glasses are a dead match for johns 67 ones#and i couldnt stop thinking about it#then i realized the writing of it links with paul missing the induction ceremony and i was a goner#the labyrinths#fic bunny#for whoever wants it#1961 paris trip#a hard day’s night filming#march 1967#rene magritte#the dangers of iconography#cursed apple painting#my brave face#paris#paul wearing johns things#mine

99 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wood Island – The Military Testing Site I Found on Google Earth

Google Earth and Wikipedia are my absolute favorite digital spaces. It has to do with how they act as platforms for crowd sourced projects, how personal they feel when you’re using them, and how their only mission is providing information to the public. There’s something impersonal about being one of the million people reading an article because it’s in the top news stories of some digital magazine. And it’s stressful to have to filter through the bullshit when listening to or reading a story from a for-profit news source. Especially today, when the news and social media algorithms have an incentive to weave together information into stories which incite negative emotions and bolster specific political ideologies. When I feel like I’m trapped in a tornado of lies, misdirection, and misinformation, I find it grounding to dive into a wholesome Wikipedia rabbit hole or exploring some distant land through the eyes of Google Earth. It’s inevitable, whenever I do this, that I will find some interesting gem of a fact that brings me some personal awe and satisfaction.

So, as I mentioned in a previous post, the family went down to Emerald Isle for a week back in July. Shortly afterward we came back, I checked out the area using Google Earth and found one of these hidden gemlike factoids. Emerald Isle is the town located on the Bogue Banks Island. Bogue Banks is a barrier island that is about three to four blocks wide and runs parallel to the coast of NC. Our house was on the South facing, ocean / beach front side of the island. Google Earth revealed that the North side of the island faced into the Bogue Sound and was lined with private boat docks. The Bogue Sound had quite a few small islands scattered within it. I noticed that the closest of the Bogue Sound islands, Wood Island, is only about 400 yards for our former location. Little islands have always been an interest of mine so I zoomed in. (I took a screenshot of Wood Island and have it pictured above) Getting a closer look revealed a curiosity.

It doesn’t take a trained eye to notice that Wood Island is covered with some strange circular marks. At first, I wondered if these were sinkholes and caves formed by limestone erosion, but I decided to google search it to make sure and I found that those marks have an even cooler explanation that odd erosion. Multiple articles popped up stating that Wood Island (and in fact most of Emerald Isle) was a bomb target practicing spot from 1943 to 1955. Apparently, the island is off limits due to there still being the very real presence of live munitions scattered across it!

Here’s some clips I copied from an article I’ll link below:

According to a report provided to the town, in spring 2009 the military prepared a digital geophysical map, using a commercial helicopter flying over the part of Bogue Sound that surrounds the island.

“The purpose was to detect and accurately map metallic items (referred to as magnetic anomalies). In addition, samples of soil, surface water, and sediment were collected and analyzed for munitions-related chemicals, such as metals and explosives residues,” the report states.

The Navy and Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point conducted the potential impact study of the past training operations as part of a nationwide evaluation of historic military training sites. The Naval Facilities Engineering Command led the investigation, in partnership with MCAS Cherry Point and the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and other federal and state agencies provided technical support. According to the report, a site inspection of Wood Island found remnants of old munitions and fragments on the surface, along the shoreline and partly buried on the island.

In the aerial DGM survey of Bogue Sound, magnetometers were mounted on booms attached to the helicopter. Magnetometers measure the strength or direction of the earth’s magnetic field. A mass of metal creates a detectable disturbance in the magnetic field. The helicopter flew back-and-forth passes at four to five feet above the water to locate and create the digital map of magnetic anomalies, essentially metallic objects. These anomalies could be munitions submerged under water or buried under the surface of the ground, or they could be unrelated metallic objects related to recreational or commercial use of Bogue Sound, such as crab pots or anchors or tools.

According to the report, the survey identified approximately 10,400 magnetic anomalies.

“There are several clusters of concentrated anomalies near Wood Island,” the report states. “The rest are irregularly distributed throughout the 10-square-mile investigation area. The highest concentration of metallic objects is clustered within approximately 650 feet of Wood Island. Three much smaller clusters of metallic objects were found in the investigation area, further away from Wood Island in Bogue Sound.

“One cluster is located approximately 2,500 feet southwest of Wood Island. The second cluster is located about 2.5 miles east (of the range), directly off the northern shoreline between 1st and 2nd streets in Emerald Isle, near some docks and piers that extend into Bogue Sound. The third cluster is located near Dog Island, about 3,000 feet north of the shoreline near the Emerald Isle/ Indian Beach town boundary.

“Except for these small clusters, the density of metallic objects decreases as you move from Wood Island toward Emerald Isle,” the report continues. “Many munitions remnants and fragments were observed on the surface of the island during site visits.”

The report says that the site inspection also considered potential environmental risks, but “little or no risk was identified. For a health risk to occur, people or wildlife have to be exposed to chemicals. This is called a complete exposure pathway. A human health risk screening, considering the sampling data and potential exposure pathways, did not identify unacceptable short-term or long-term human health risks from exposure to surface soil, sediment, or surface water …

“Similarly,” the report continues, “an ecological risk screening found that no significant risks are expected for wildlife … exposed to surface soil, sediment, or surface water… Based on the results of the preliminary human health and ecological risk screening, no further evaluation of chemicals in the surface soil, surface water, and sediment is recommended …

“Unexploded ordnance, however, is a potential risk to human safety. The old munitions visible on the surface of Wood Island and the high concentration of magnetic anomalies in the waters around the island show that further munitions investigation is needed.

“After a site inspection, the next phase in a munitions investigation is to determine the nature (types and physical condition) and extent (affected areas, including depths) of the magnetic anomalies that are likely to be munitions and explosives of concern.

“The Navy will evaluate alternative methods that would allow such an investigation to be safely carried out. The suspected munitions are mainly underwater or underground and are expected to be in poor condition, weathered or corroded, like the munitions observed on the surface. Those factors make this identification process complicated, as well as potentially dangerous for the investigation team. Because of this, considerable time will be required to plan and carry out the investigation.

“Meanwhile, MCAS Cherry Point and the Navy are considering how best to protect the public. Protective measures could include removing potentially hazardous munitions and fragments from the surface of Wood Island … installing additional warning signs or restricting bottom-disturbing activities in the waters adjacent to the island…

SO FREAKING COOL! Now I have a burning desire to explore the island, or at the very least use it as a setting for a horror story.

https://www.carolinacoastonline.com/tideland_news/news/article_f6ed079f-4713-5956-b831-862308e820e4.html

#military#military testing#bogue island#emerald isle#beach#google earth#wikipedia#open source#bomb#lost bomb#science#geography#history#horizon

1 note

·

View note

Text

Rabbit Hole #1:

I started thinking of how certain words just become a part of your lexicon from childhood and you have no idea how it happened. When did I first encounter this word? We often don't ask ourselves this, but I did last month after watching season 5 of Doctor Who. In it, the 11th doctor shouts "Geronimo!" for the first time and even sends it as a message to River Song and Amy Pond in their race against time to restore the fabric of time as the TARDIS continues to explode, causing gaps in history and memory (not getting into this now though).

Anyway, the point is, some words just stick with you throughout childhood due to their frequent use in cartoons, books and other children's entertainment. Geronimo is one of them for me.

It is defined as a way to express excitement or happiness, usually when doing something adventurous, eg. what a sky diver would yell before jumping out of a plane. In fact, it was a battle cry used by paratroopers, especially during World War II, on jumping from a plane.

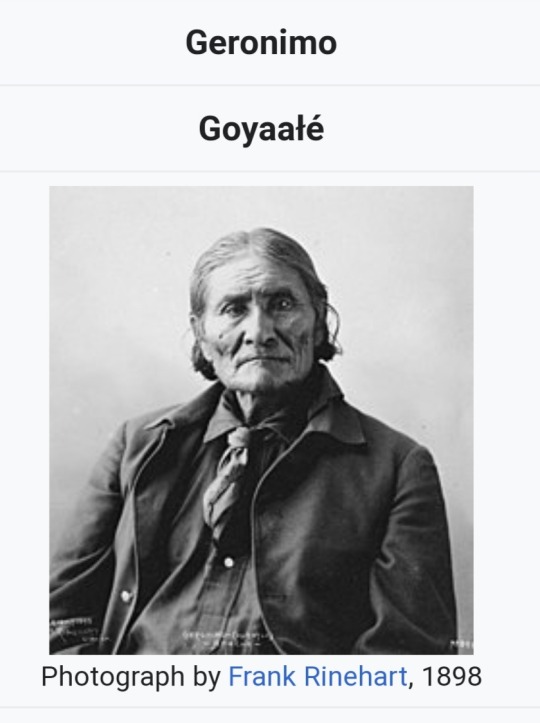

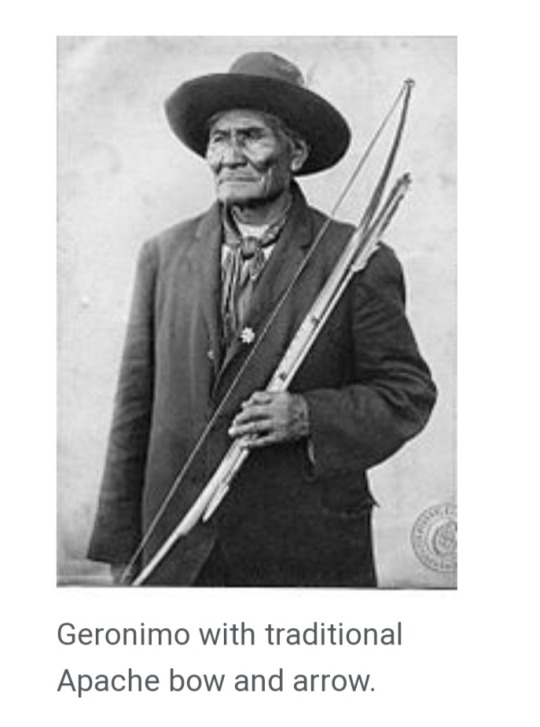

I also found out (did not know this until I googled the definition) that Geronimo, or Goyaale, was a man! A prominent leader and medicine man born June 16, 1829 and died February 17, 1909 from the Bedonkohe band of the Ndendahe Apache people. He led numerous raids and related combat actions during the period of the Apache - United States conflict, which started with the American invasion of Apache lands following the end of the war with Mexico in 1848.

He orchestrated breakouts on reservations, which were confining to the free-moving Apache people, in attempts to return his people to their previous nomadic lifestyle. It would be like if the Freeman population in Dune were put in reservations. Urgh. Anyway, he sounds like a cool dude, although some view home more as a crazed murderer of Mexicans and Americans alike. White settlers referred to him as "the worst Indian who ever lived". Hey, history is complicated.

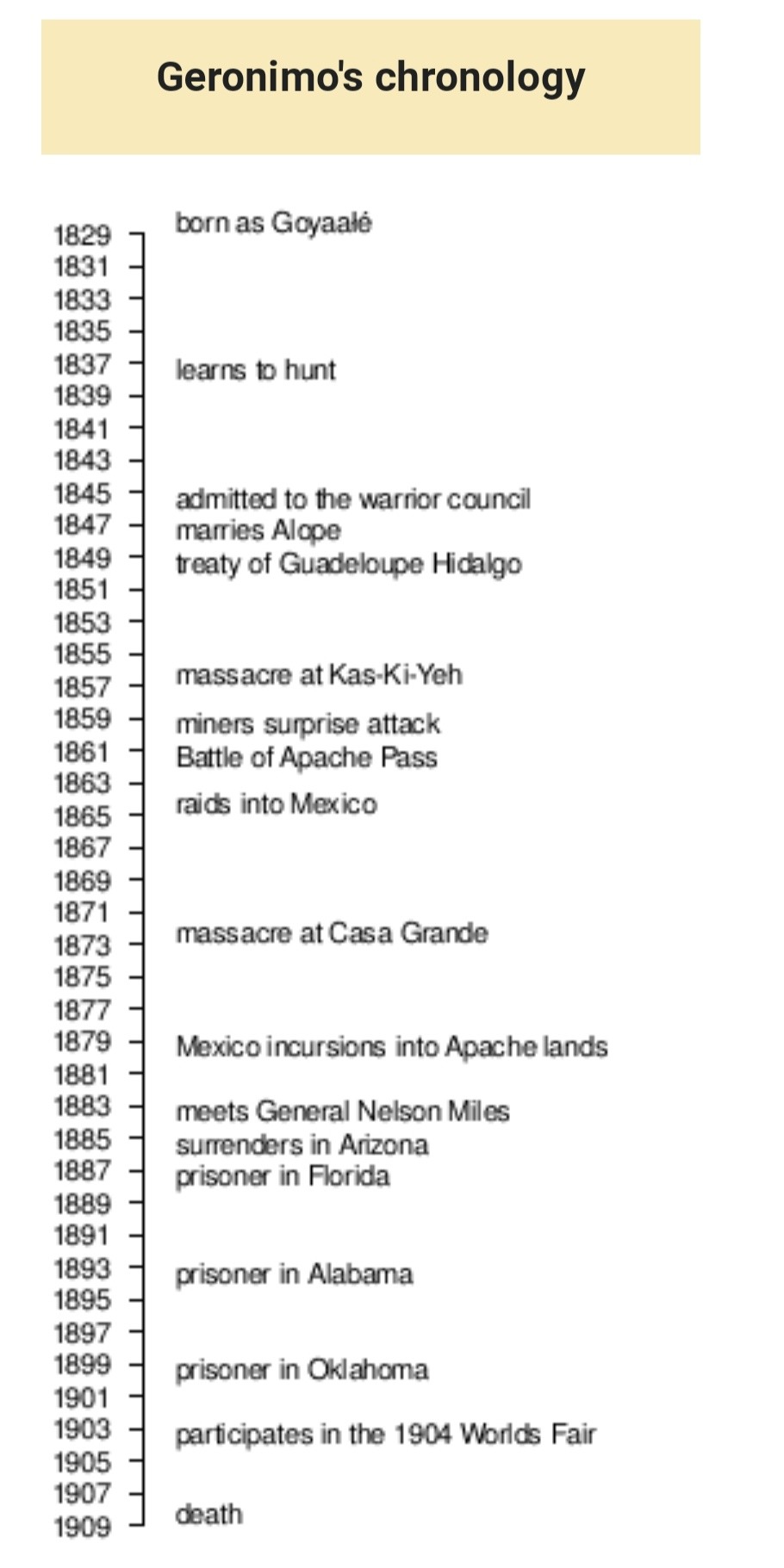

It's amazing that there's this chronology on Wikipedia that so easily condenses his life. If we had people tasked with chronicalling our lives in a book like they did on Game of Thrones, I wonder if that would change or influence how we lived our lives? In a way, social media is a self-curated version of a chronicle of our lives.

Geronimo later became a celebrity of legendary status, even taking part in the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904. He dressed in traditional clothing, posed for photographs and sold crafts, including buttons from his shirts and hats. Visitors came to see how the "savage" had been "tamed". Oof! But I guess if your culture is to be turned into a side-show, at least make some money out of it.

Although I can't remember where I first heard someone shout "Geronimo!", I am quite certain it was in a cartoon. Imdb has a list of the most popular movies and TV shows to have a character shout "Geronimo!", with number 1 being Toy Story 2. The Doctor Who episode where the 11th doctor (played by Matt Smith) says it, titled "The Lodger", is also listed.

Tracing the source of the name "Geronimo" has been quite the unexpected journey (take that Bilbo Baggins!). But then again, that's the point of this Tumblr page, that a simple thought, idea or Google search can send you down a rabbit hole of knowledge and curiosity that you didn't know was possible. Typing "the first use of geronimo" into the search bar took me first to pre-civil war America to meet a man who earned the nickname while leading Apache raids. Some historians believe that Geronimo was called this because the term has its origins in the cries of frightened Mexican soldiers calling out the name of the Catholic St. Jerome when they faced Geronimo in battle.

Then it took me to the United States during World War II, where "Geronimo" was used as a United States Army airborne exclamation occasionally used by jumping paratroopers (or anyone about to jump from a great height) as a general exclamation of exhilation. While the origins of it being used in this manner is traced to Fort Benning, Georgia, where some of the first of the US Army's parachute jumps occurred in the 1940's, it is disputed how this happened.

One theory comes from paratrooper Gerard Devlin, who dates the exclamation to be from August 1940 and attributes it to Private Aubrey Eberhardt, a member of the parachute test platoon at Fort Benning. On the eve of the platoon's first jump, they decided to calm their nerves by spending the day watching a film at the Main Post Theatre and a night at the local beer garden. The film they saw was a Western featuring our guy Geronimo. While the title is uncertain, it is believed to probably be the 1939 film Geronimo with Andy Devine and Chief Thundercloud (cool name!). On the way to the barracks, Eberhardt's comrades taunted him saying that he would be too scared to even remember his name tomorrow when they perform their first jump. Eberhardt retorted, "All right, dammit! I tell you jokers what I'm gonna do! To prove to you that I'm not scared out of my wits when I jump, I'm gonna yell 'Geronimo!' loud as hell when I go out that door tomorrow!" Eberhardt kept his promise and the cry was gradually adopted by the other members of his platoon.

The second theory comes from Major Richard Winters, who in his book "Beyond Band of Brothers: The War Memoirs of Major Richard Winters", explains that at the time when the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment at Fort Benning was due to jump, there was a popular song called "Geronimo" on the radio which quickly became a favourite amongst the troops.

The third theory comes to us from the Medicine Bluffs at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where Geronimo was jailed as a prisoner of war and his grave is located today. The Medicine Bluffs are steep cliffs that have come to be known as Geronimo's Bluff. Tall tales were told about Geronimo while at Fort Sill, including the now famous legend of Geronimo leaping on horseback down an almost vertical cliff with the Army in hot pursuit. It is said that in the midst of this jump to freedom, he cried out "Geronimo-o-o!".

Although we are not sure which story is the correct one (the first one is my favourite, while I think it is fair to say that the third one is most likely fiction), the cry grew in popularity amongst the Army's paratrooper regiment, despite worries from those in charge that the cry lacks discipline. Excitedly, the Army's 501st and 509st Parachute Infantry Regiments incorporated the name "Geronimo" into its insignias in the early 1940's, with permission from Geronimo's descendants. By then, the coverage of the paratroopers' exploits during World War II had made the cry "Geronimo" known to the wider public and its use spread outside the military and the US Army.

So as I take a leap into writing and consequently sharing my thoughts online, I shout "Geronimo!" in fear, but mostly excitement.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Creative Inquiry - Curiosity and Creativity

Door Activity

I decided to choose the more “Fantasy” inspired door which led me to Maria Popova’s blog “brainpickings” (Popova, 2006) which I read her latest post about Willard Gibbs. To start off during this experience I was a little confused; that was more so led from being dropped into an article without much context. The title was somewhat abstract so I could grip onto some ideas but I wasn’t sure if they necessarily matched the context of what I was about to read. I’ve never been a faster learner and because of that I’ve developed the capacity to quickly make connections with previous understandings I have to compensate. That did mean that the first paragraph for the most part went over my head and was a warm up and I had to read again after getting some ways through the article to actually understand the points they were making.

Once I had a grip of the context of the article and what was being stated I did start to get quite invested in what was written. The two things that really stood out for me was Rukeyser’s passion for knowledge that maybe isn’t quite practical in the present but is still powerful and Williard Gibbs himself. It made me develop more of an appreciation for those who perform theoretical work as well as my own theoretical processes I perform in my head that may not lead anywhere but all the same make my thoughts more robust.

At the point of exploration I chose to look more into Williard Gibbs, I wanted to know what inspired Rukeyser so much and what was so special about him. It was somewhat interesting to find a man of a lot of humility, he did not seek fame but just the development and exploration of thought and then to leave it for others. After all these written celebrations of him it was quite interesting.

The task itself I did find a little frustrating, maybe it’s because going down the internet rabbit hole for things that make me curious is such a natural thing. Clicking through links in a wiki or just searching terms that make me curious. In this case it felt more artificial, my actions were defined by a structure and overall the process was somewhat forced. I think it’s also to do with my familiarity with academic tasks, I’m used to defined roles that I should stick to and being assigned a task that is so free I can feel lost and my actions in precise.

Cultivating Curiosity

My Curiosity mostly commonly seems to be driven by understanding, and not just understanding through fact but also how perspective drives understanding and expression of ideas. I’ve found the more ways that I understand a concept from a multitude of perspectives the more ways I’m capable of using that idea in things like storytelling and combining them to create something powerful. I do this a lot with the media I consume, specifically looking for negative and positive reviews from others; identifying patterns and uniqueness and what that says about the work as well as the reviewer themselves. I’ve started to try to apply this methodology to other aspects of my life since I’ve found it so useful but I have found you need to step back as much as you can from your own biases.

Leading from that reading through the “8 Habits of Curious People” (Vozza, 2015) I do find it interesting that number one is “They Listen Without Judgement”. As I said before my biases are definitely something I’m aware of and have tried to dull but I’ve never tried listening without those biases at all. Thinking back I do feel like I have stifled my own curiosity by not letting go and allowing myself to be consumed by someone else's perspective, then returning to my own perspective and biases and using that information.

I really like the quote used from Tania Luna that “We feel most comfortable when things are certain, but we feel most alive when they’re not.” (Luna, 2015) I really enjoy having some sort of process laid out for me when I am completing a defined task and that makes me feel comfortable, but when I’m still exploring how to complete a task I’m at unease and to some extent scared. There is always a fear that I will not find what I’m looking for, when I do find it there is excitement and relief for what comes next, but the whole process feels like there's a lot of undue anxiety related to it.

My process for dealing with this anxiety has always been to try and immediately find a “Worst case scenario option” (Vozza, 2015) so if I don’t find what I’m looking for I can fall back on that. Which I feel is a good safety net, but doesn’t eliminate that anxiety which takes up brain space I could use for my own curiosity related to information that I find. This leads into another point made in the article I need to strengthen which is being “Fully Present”. I commonly multi-task to lessen the strain I feel when I’m in this state of unease; but this may be part of the problem, I need to allow myself to be more present and process this anxiety to overcome it. Then by being fully present and overcoming this anxiety I can apply my focus and curiosity to the undefined task at hand, exploring without inhibition.

In Jane Santa Cruz’s article “Inquiring Minds: Curiosity as a Catalyst to Discovery” (Santa Cruz, 2020) similar to Chris Wire’s TEDx Talk (Wire, 2014) she talks about how a question with a defined answer quells curiosity as it provides a defined end point. The way they describe a question is that it sparks curiosity, almost like a call to adventure; the act of seeking out the answer is the adventure with the answer itself being the end of the story. Immediately acquiring the answer skips the adventure and the personal growth that comes with it and leads everyone to the same point.

For myself I’ve never really had a problem with having an immediate answer to a question through google, it’s never quelled my curiosity as they describe it. But when taking the curiosity profile it did remind me that I need to have an understanding of how something that works and that includes answers. So when I get an answer on google that isn’t the end of the adventure, it is an element of context but I want to know where the answer came from, how was it decided, are there any faults or biases within it? This is a good frame of thought to have, using google as a stepping stone to further understanding but I should give myself the opportunity to make my own conclusions before immediately searching for an informed response to my question.

My Curiosity Plan will focus on these three elements, the first being to step away from my own judgement and biases when I’m presented with information. Then returning to those judgement and biases once I’ve given myself a new perspective. The second to be more in the moment when in a space where I expect surprises and discovery to allow my own curiosity to better flow and to overcome the anxieties that restrict it. The third is to still use google, but not to have it be my immediate response to finding context on a question or topic.

References:

A Hemingway. [YouTube Channel] (2017, May 2nd). The History of Josiah Willard Gibbs. [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fms2JkmVBL0

Crowther, J, G. (2020). J. Willard Gibbs American scientist. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/J-Willard-Gibbs

Luna, T. (2015, April 7th). Surprise: Embrace the Unpredictable and Engineer the Unexpected. [Book].

Popova, M. (2006). Muriel Rukeyser on the Wellspring of Aliveness and the Shared Source of Our Confusion and Our Power in Times of Turmoil. Brainpickings. https://www.brainpickings.org/

Santa Cruz, J. (2020). Inquiring Minds: Curiosity as a Catalyst to Discovery. Right Question Institute. https://rightquestion.org/resources/inquiring-minds-curiosity-catalyst-discovery/

Vozza, S. (2015, May 21st). 8 Habits of Curious People. Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/3045148/8-habits-of-curious-people

Wire, C. (2014, February 14th). Curiosity fuel creativity: Chris Wire at TEDxDayton [Video]. TEDx Talks [YouTube Channel]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fw3aynVqWs4&feature=emb_title

0 notes

Text

Erwin Out

By Erwin J. Warkentin

By the time you read this, I will no longer be the Head of the Department of Sociology at Memorial University. In fact, more correctly, I was the Interim Head (2019-2021), if one can truly call someone “interim” who has led a department for 25 months.

Other than faculty, staff, and graduate students, many of you probably had little contact with me. This is not because I didn’t want to meet with you, but because of several external factors beyond our control. The most significant was the Covid-19 pandemic that found all of us locked down at one time or another. A second factor was that I was not a sociologist, criminologist, or involved in police studies in any way. You would not have found me teaching any of the courses offered by the department. I am a Germanist; that is, someone who studies all things German, whether it is language, literature, or culture.

However, one might make a tenuous connection between my personal academic interests and sociology without stretching the point to breaking. My interests in propaganda, political warfare, and censorship verge on sociology. I am the author of the books The History of U.S. Information Control in Post-war Germany: The Past Imperfect (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016) and Unpublishable Works: Wolfgang Borchert’s Literary Production in Nazi Germany (Columbia, SC: Camden House, 1997).

The only purpose you might have had in contacting me would have been decidedly bad. For example, you might have needed my signature on the bottom of a form to have an academic indiscretion go away. When you look upon the DR or DEX (drop without academic prejudice [exceptional circumstances]) on your transcript, I ask only that you remember me with kindness.

All of this is to say that I was an outsider. As such, I was in a unique position to observe things which might not have occurred to an insider, someone who had been properly christened into the world of the sociological endeavour, someone who knew how sociology was supposed to work.

You will note that I use the past tense in describing how I related to the Sociology Department at Memorial. The faculty and staff still reject my “outsider” status despite my protestations to the contrary to the bitter end. They did not permit me to claim that after more than two years of my headship I was still looking in from the outside. My stubborn penchant for offering only German courses in MUN’s Department of Modern Languages, Literatures, and Cultures and insisting on doing that in German undermines my credibility as an insider.

Be that as it may, I would still like to offer some observations on both the discipline and the department itself. I will argue that right now is an exciting and important time to be a sociologist at Memorial. I was also gobsmacked, if I may use that term, at the quantity and exceptional quality of the published and in-process research. It also revealed some of the embarrassing misconceptions that I had about my social scientist siblings in the faculty. They actually embody almost everything which I hold dear as a humanities scholar.

Well, there are many different aspects of sociology and its various subdisciplines that I could speak of. I’m afraid this would only serve to give each of those short shrifts and do them all a disservice. What I have decided to do is concentrate on one element of the sociological endeavour; however, it is the one that permeates everything else that they do. Without this one thing, not all of the others could function. Strangely, it is the one that I had not even considered as being part of good sociological scholarship because I had never really thought it was a necessary attribute. To my mind, it was reserved for the humanities. The emphasis on “science” in social science does not conjure up too much in the way of imagination. What I am referring to is the concept that C. Wright Mills coined as the “sociological imagination.” He went on to define, describe, and ultimately apply this in his 1959 book titled The Sociological Imagination.

I have chosen to highlight Mills’ work in order to better understand sociologists and their research for reasons that have nothing to do with most of the book’s contents. The fact that it contained this notion of the sociological imagination was a happy accident. It was not something that I was looking for or had hoped to find when I stumbled on it. Mills interested me for other reasons. It was actually the preface of another book that led me to this notion. This other book engaged me in a topic that I deal with on an almost everyday basis in my own professional life. The translators of Weber’s essays in their book From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, Hans Heinrich Gerth and C. Wright Mills, included a preface that briefly debated how the meaning of a text changes as one tries to reproduce it in another language. They, of course, focussed on bringing German to English, which immediately interested me so much that I decided to read whatever else they might have written or translated. It had not even occurred to me that these two were sociologists engaging me, a Germanist, in an engrossing debate in what is theoretically the purview of my discipline. From there, I followed Mills down his scholarly rabbit hole to The Sociological Imagination. Moreover, it convinced me of the overlap of all our academic disciplines no matter how disparate.

Now, I’m not going to go into a lengthy exposition of what Mills meant by his book’s content. There are people in the Department of Sociology, dare I say all of them, who are more qualified than I am to explain what Mills attempted. I simply want to use the notion of the existence of a “sociological” imagination as a jumping-off point for my observations of the world of sociology at Memorial. Mills’ idea was my own inspiration for how to best describe what the sociologists in the department are about and the curiosity they attempt to awaken in their students, even if the notion has lost some of its original meaning in my translation.

The sociological endeavour looks for connections between larger events. It also seeks the relay points between the individual and their private world and with the public sphere of these large events. This is the essence of Mills’ sociological imagination. Events may play themselves out on a grand scale but affect the individual on a very personal level and vice versa. Events that may shake the foundations of an entire society may emanate from an individual and the waves caused by their interaction with other isolated individuals.

At Memorial, the Sociology Department provides students with a place to discuss these sorts of issues. What I learned was that the faculty teaches a method of approaching and understanding how individuals and social forces interact to create the communities in which we live. More than that, how we can identify and correct our failings while strengthening

those things that we do well.

To teach the newest and most exciting aspects of sociology and criminology, one needs to conduct research into the “how’s and why’s” of society. What has impressed me most is not that the faculty excels at providing students with the right answer to their questions, I simply assumed that they could, but teaching students how to ask the right questions in the first place and then framing those questions in such a way that they can find the answer for themselves, even if it is not to be found in a book but rather in data that may not have been collected yet.

In the last 25 months, I have been asked what one might do with all the above. It was as if the students (or often their parents) had forgotten that they were not talking to a sociologist. I would humour them and produce the standard answers that one might find in a very unoriginal Google search. I would then enumerate the usual suspects, which I had quickly learned by rote:

Social researchers

Paralegals

Public policy researchers

Data analyst

Public relations specialists

Etc. ad nauseam

I even added that they might continue into law, social work, or, if they had nothing better to do, sociology as a professor at a college or university.

Usually, this satisfied people. They left with a smile, secure in the knowledge that they or their children would be able to put a roof over their heads and food on their table with a major in sociology or police studies/criminology. However, I ached to give them the answer that lay close to my heart. The one that I knew the faculty were actually conveying to our students. I really wanted to say: “You know. The people in the department, from Adler to van den Scott, really excel at creating an informed and educated citizenry vital to our society and our form of government. That means they are creating the future without anyone really knowing it.”

For one reason or another, they never received that answer from me. I’m not usually that shy. My impression of what we did for our students and our communities, province, and country may not have been as unassuming as getting them a job after graduation. Still, it is what I observed the department doing collectively, perhaps even quite unawares. They may have been trying to do it consciously on an individual basis and even thinking that they were failing at it, but as a collective, they are succeeding spectacularly.

I am so happy that I was permitted over the last 25 months to be this casual observer, allowing myself to be educated in what it means to be a sociologist.

What does this mean for the future?

I think the department will see some exciting changes. The first of these is the change of name of Police Studies to Criminology. This was approved by the University Senate in February 2021. This not only reflects what the situation is. It labels quite precisely what the department’s faculty are actually teaching, researching, and publishing. It also brings Memorial into line with what most other programs in North America do. This will be good for the department and its graduates.

This is only the end of the beginning. With new leadership in place, the Department of Sociology is set to grow stronger into the future.

0 notes

Link

“It is clear that the stake [the mountaineer] risks to lose is a great one with him: it is a matter of life and death…. To win the game he has first to reach the mountain’s summit – but, further, he has to descend in safety. The more difficult the way and the more numerous the dangers, the greater is his victory.”

- George Mallory, 1924

As though napping, the climber lies on his side under the protective shadow of an overhanging rock. He has pulled his red fleece up around his face, hiding it from view, and wrapped his arms firmly around his torso to ward off the biting wind and cold. His legs stretch into the path, forcing passers-by to gingerly step over his neon green climbing boots.

His name is Tsewang Paljor, but most who encounter him know him only as Green Boots. For nearly 20 years, his body, located not far from Mount Everest’s summit, has served as a grim trail marker for those seeking to conquer the world’s highest mountain from its north face. Many have lost their lives on Everest, and like Paljor, the vast majority of them remain on the mountain. But Paljor’s body, thanks to its prominence, came to be one of the most well-known.

About 80% of people take a rest at the shelter where Green Boots is, and it’s hard to miss the person lying there

“I would say that really everybody, especially those climbing on the north side, knows about Green Boots or has read about Green Boots or has heard somebody else talking about Green Boots,” says Noel Hanna, an adventurer who has summited Everest seven times. “About 80% of people also take a rest at the shelter where Green Boots is, and it’s hard to miss the person lying there.”

With Paljor’s death came a wave of controversy, including whether he and his two teammates died because other climbers, in their own lust to reach the peak, callously ignored their signs of distress. Scant information is available about the man behind the nickname, however. Type “Green Boots” into a Google search and you will learn that Paljor, along with climbing partners Tsewang Smanla and Dorje Morup, perished in the 1996 storm immortalised in Jon Krakauer’s best-selling book Into Thin Air and, more recently, the big-budget thriller Everest. Paljor, Wikipedia tells you, was a member of the Indo-Tibetan Border Police, and was just 28 years old when he lost his life.

Tsewang Paljor, in younger days. Photographs by Rachel Nuwer.

I admit to feeling a certain morbid curiosity at the thought of Paljor and all the other fallen climbers on the mountain, stranded far from loved ones and frozen in time, forever displaying the moment of their death. But more than a fixation on the macabre, I wished to know the story of the handsome young man in the green boots – especially the circumstances that could allow him to remain on the mountain for so many years.

I was also intrigued by what extreme altitude can do to the human body and mind, and the unexpected impact it can have on the decisions – and even ethics – of a person. But ultimately, I wanted answers to another, more pressing query; one that has been raised countless times but seems to evade explanation: why climb this mountain at all? Why gamble your life on its unforgiving slopes? According to the records of Alan Arnette, a mountaineer based in Colorado whose blog is a trusted source of Everest information, from 1924 to August 2015, 283 people have died on the mountain – 170 foreigners and 113 Nepalis – leading to an overall deaths-to-summit ratio of about 4%. How is it that so many people still see this endeavour as worthwhile?

My desire to answer these questions – in a two-part in-depth series for BBC Future – led me down a rabbit hole of psychology, ethics and climbing culture; to the doorsteps of mountaineering legends and broken-hearted parents alike; to sources spanning Fukuoka, California and Kathmandu. This is my attempt to make sense of what I found.

A cheerful place

As the plane lifts off and heads north from New Delhi, the city’s smog, congestion and sprawl quickly fade from view, replaced by brown, rural flatness that in turn morphs into green hills and terraced fields.

Ladakh, “owner of passes,” which lies in the shadow of the Great Himalayas

The landscape, however, has only begun to grow in scale and splendour. Hills climb to ever-greater heights, shaking themselves free of villages, fields and vegetation – and then, any remnants of life. Jagged, snow-kissed mountain peaks stretch ever higher, as though trying to pluck our tiny vessel from the sky. Here and there, a valley river punctuates the monochrome landscape with a ribbon of green, a lifeline in an otherwise impossibly inhospitable environment.

We’ve almost reached our destination. The plane begins its descent, and the captain’s voice crackles over the intercom: “I hope all of you have left all of your worries behind in Delhi, so you can have a great time in this cheerful place.”

We’re in the region of Ladakh, “owner of passes,” which lies in India’s far north, in the shadow of the Great Himalayas. It’s early September, when the days are bright and warm but nights are already creeping below 0C.

It was here, in this high altitude desert at 3,800m (12,500ft), that Tsewang Paljor was born on April 10, 1968. He grew up in Sakti – “the golden throne” – an idyllic valley village of whitewashed houses, barley fields and poplar trees.

Leh, Ladakh’s dusty capital

We set out for Sakti early on a Wednesday, following the course of the brilliant blue Indus River, passing breathtaking mountainside monasteries, dusty roadside diners and otherworldly plains of rock and barren earth. I travelled with Tsultim Dorjey, a sociologist and guide, who is serving as my local lifeline.

We had not contacted Paljor’s family ahead of time, believing our odds of convincing them to speak with us about such a sensitive subject would be greater if we described our mission in person. Now, I was plagued by doubt. Would they refuse to speak with us? Would they be offended? Would anyone even be home?

On the road to Sakti

We passed dusty, otherworldly plains on our journey

Passing remote villages on the way to Paljor's home

About an hour after leaving Leh, we were getting close. Tsultim jumped out of the car, approaching an old man fingering some Buddhist prayer beads on the side of the road. Asking the man where we could find the Fana farm – Paljor’s family surname – the man began gesturing emphatically down the road. In a place like Sakti, populated by just 300 or so households, everyone knows everyone else. “It’s not far now,” Tsultim reported, climbing back into the car.

Getting directions in Ladakh

Minutes later, we arrived at a brown gate, in front of an attractive two-storey home with large windows and fluttering Tibetan prayer flags adorning the roof. “This is it,” Tsultim said. “Fingers crossed.”

My stomach churned as we approached the front door, past a garden brimming with petunias, marigolds and daisies and a yellow dog, who gazed lazily at us from a sunny spot.

Arriving at the home of Paljor's mother, unsure what to expect

My fears were alleviated, however, the moment Tashi Angmo, Paljor’s mother, opened the door. At 73, her twinkling eyes and smiling face appeared a decade younger. Radiating grandmotherly warmth, she greeted us energetically – “Julay!” – and beckoned for us to come inside, not even asking who we were or why we were here.

We made our way into the sitting room, lined with couches, ornately carved tables and poster-size photos of her grandchildren. After fetching a pot of steaming tea and a plate of biscuits, she and Tsultim exchanged niceties for several minutes. I didn’t have to understand Ladakhi, however, to recognise the moment when Tsultim revealed the true purpose of our visit. Tashi Angmo’s face, until now all smiles, abruptly went slack, her numbed expression speaking of years of accumulated grief and loss. Yet when Tsultim asked if we could proceed with the interview, she said yes.

The house of Tsewang Paljor’s family

A quiet middle child with five siblings, Paljor was known in the village for his polite, compassionate manner. He had a big heart and natural kindness. Though good-looking, even as a teen Paljor never had a girlfriend – he was simply too shy. He once told his brother that he was more interested in dedicating his life to something bigger than himself than in getting married.

As the eldest son, Paljor no doubt felt pressured to provide for his family, which was struggling to make ends meet at their modest farm. So after completing 10th grade, he quit school and tried out for the Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP), whose sprawling campus was located in nearby Leh, Ladakh’s dusty capital. Formed in 1962 in response to increasing hostilities from China, the men who serve in that armed force specialise in high altitude landscapes – a necessity given that India’s border with its domineering neighbour stretches across the Himalayas. To Paljor and his family’s delight, he made the cut.

Tashi Angmo, with her son's possessions

Tashi Angmo was very supportive of his position at the ITBP, but he sensed that her support would only extend so far – certainly not to the top of the world’s highest mountain. So when he was selected to join an elite group of climbers who would undertake a risky but grandiose mission – to become the first Indians ever to summit Everest from its north side – he chose not to reveal his true destination to her. “He told a small lie, that he was going to climb a different mountain,” his mother says. “But he also told some friends what he was actually doing, and word got back to us.”

Although Paljor’s career already included many successful summits of other peaks, and Tashi Angmo’s shelves brimmed with his certificates and awards, Everest struck her as being an exceedingly dangerous place. She implored her son not to go, but he told her he had to. “He must have thought, if he climbs Everest, it will bring benefits for his family,” she says.

A certificate marking Paljor's ascent

But younger brother Thinley Namgyal was not worried. His brother was the strongest person he knew. “When he came home for holidays, we used to play around and kick his tummy, because it was like a rock,” he says. “I always thought of him as a kind of Superman.”

Thinley, who is a monk, met Paljor in Delhi days before he was due to leave; he gave his brother a blessing before telling him goodbye. “He’d just passed his health exam, and he was so excited to go to Tibet,” Thinley says. “He wasn’t nervous at all. He was really happy about all of this.”

Thinley was the last family member to see Paljor alive.

**

Paljor was young, strong and experienced, but Everest presents multitudes of ways to take the life of even the most well prepared climber – falls, avalanches, exposure and more. The body also baulks at the insults it endures on the mountain. Sudden death – from heart attacks, strokes, irregular heart beat, asthma or exacerbation of other pre-existing conditions – is not uncommon, and lack of oxygen can trigger acute pulmonary or cerebral edema: life-threatening conditions that occur when blood vessels begin leaking fluid into the lungs or brain.

Documentation for Paljor: resident of Sakti, climber, no children - from the files of Elizabeth Hawley

Not everyone on the mountain shares the same odds of dying under any given circumstance, however. In a retrospective study of 212 climbing deaths on Everest from 1921 to 2006, Paul Firth, an anesthesiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues found that most Sherpa deaths occur at lower altitudes, reflecting the unavoidable risk of traversing the Khumbu icefall – an unstable glacier field laden with house-sized ice blocks and gaping crevasses. Deaths at higher elevations, on the other hand, almost entirely belonged to paying clients and Western guides, and more than 50% of deaths above 8,000m (26,000ft) occurred after climbers had summited and were on their way back down. “I was surprised at how few Sherpas have died high up,” Firth says. “But the numbers are glaringly obvious.”

These findings likely reflect a multitude of factors, including Sherpas’ possible superior adaptations to hypoxic conditions, their greater experience on Everest and their lack of vulnerability to summit fever – an overwhelming desire to reach a mountain’s peak that causes climbers to disregard safety. “People make decisions based on success, not on survival,” says Ed Viesturs, the first American to have climbed all 14 of the world’s 8,000m peaks, and the fifth person to do so without supplemental oxygen.

A medal awarded after Paljor's death

When Mark Jenkins, a journalist, author and adventurer in Wyoming, was on Everest in 2012, five people died on a single day. Sherpas he interviewed told him that most of the fatalities belonged to clients who had refused to turn around. “Your Sherpa will tell you, ‘You’re too slow, you have to turn around or you’ll die,’” he says. “And some people don’t.”

“Mountains don’t kill people, people kill themselves,” he says.

(Read part two in this series, about the problem of Everest's 200+ bodies.)

Viesturs, who once ended a climb on Everest within 100m (300ft) of the summit because conditions did not look good, credits his survival to always listening to the mountain and knowing when to turn back. “My rule was that climbing had to be a round trip,” he says. But many of Everest’s victims, Firth contends, are likely people who don’t recognise early warning signs because they lack sufficient experience to know what’s normal, or else are experienced climbers whose judgment is muddled by the effects of altitude. By the time they realise they are in trouble, it’s too late.

Kathmandu, where many Everest journeys begin

Jenkins estimates that half the climbers on Everest today do not belong there. “Its not my opinion, it’s just a fact,” he says. “The highest some of them have ever been is up a skyscraper.”

“Without Sherpas, 98% of people who climb Everest couldn’t,” agrees Billi Bierling, a Kathmandu-based journalist, climber and personal assistant for Elizabeth Hawley, a former journalist, now 91, who has been chronicling Himalayan expeditions since the 1960s.

Files of expeditions, kept by Elizabeth Hawley

On Everest, things were proceeding without a hitch for Paljor and his comrades. The Indian expedition was well connected on the mountain, with a luxurious communal tent that all climbers, regardless of nationality, were welcome to visit.

Commandant Mohinder Singh, who led the team, told me about the expedition at his home outside of San Francisco, where he now manages an apartment complex: “We were the top class in the world.”

Mohinder Singh and his wife at their home outside of San Francisco

For his strength and enthusiasm, Singh selected Paljor to be part of the first summit attack team, along with climbing partners Tsewang Smanla and Dorje Morup, and deputy leader Harbhajan Singh. “Paljor wanted to do many things in his life,” says Singh, who believes the young man looked up to him as a sort of father figure.

He recalls Paljor as being very talkative, “like a child,” and that he loved to attempt difficult rock climbs. “He looked like a monkey when he climbed,” Singh says. He also remembers Paljor’s love of roast chicken; his tendency to sing in his free time; and that he was always volunteering to take on difficult jobs. “He was very helpful like that,” Singh says.

Almost immediately, the expedition was marred by 'mistake after mistake'

Singh was confident in Paljor, Morup and Smanla’s skills – they were all from Ladakh, and had all proven themselves in the field. However, almost immediately, the expedition was marred by “mistake after mistake,” in which the climbers “failed to follow clear instructions,” Singh later reported in his official account of the events.

The problems started on the morning of 10 May, when the team was delayed by strong wind and then overslept. They did not set out from Camp VI until 08:00, rather than 03:30 as planned. Given the extremely tardy start, they decided to move further up the mountain to fix ropes rather than attempt the summit, since doing so would guarantee descending through the Death Zone in the dark – the area above 8,000m where climbers often lose their lives.

Harbhajan Singh, deputy team leader, and the only survivor of the expedition

By 14:30, the team had made significant progress, but the wind had begun to pick up again. Singh had given the team strict orders to turn around at 14:30, or 15:00 at the latest. Harbhajan Singh, however, was lagging far behind the three Ladakhi men. When he signaled for them to stop and return to camp, they either did not see him or ignored him. Watching as they pushed on, the frostbitten Harbhajan Singh had no choice but to descend back to Camp VI without them.

Speaking about this moment 19 years later from his bright office in New Delhi, Harbhajan Singh, now an inspector general at the ITBP and recipient of the Padma Shri, India’s fourth-highest award, gets a distant look in his eyes.

“When we lost these three people, I was the fourth, I was with them,” he says, gazing beyond me. “I’m in front of you today, but if I would have tried, I would be gone. It’s only God’s gift that I am alive.”

Summit fever, he suspects, had overtaken his men.

Everest has killed nearly 300 people (Credit: Getty Images)

At last, at 15:00 that afternoon, an anxious Singh, awaiting news from Advanced Base Camp, heard his walkie-talkie sputter to life. It was Smanla.

“Sir, we are heading towards the summit,” Smanla announced.

Singh was taken aback. “Oh no! The weather is very deceptive, bad.”

Smanla was not to be dissuaded, however, and pointed out that the summit was less than an hour away and that all three men felt fit.

“Don’t be overconfident,” Singh insisted. “Listen to me. Please come down. The sun is going to set.”

Smanla shrugged off the warnings, and put Paljor on the phone. “Sir, please allow us to go up!” Paljor said, his voice brimming with pride. But just then, the radio cut off.

It wasn’t until 17:35 that Singh heard back from his men. A flood of relief and excitement washed over him as Smanla announced that he, Paljor and Morup were standing on the summit. Even as Singh stressed the importance of returning as soon as possible, he began looking forward to the triumphant message that he would send to New Delhi announcing his team’s victory.

Celebrations immediately ensued, both at home and at camp. The men had just set a record for their country. Whether Paljor and his teammates actually summited, however, was later called into question. Krakauer and others suspect that the men unintentionally stopped 150m (500ft) short of the peak, believing – due to increasingly bad weather and the mental haze of high altitude – that they had reached the top. Despite the uncertainty, however, they are credited with the ascent, as the trophies Tashi Angmo later received on behalf of her dead son attest. As Singh says: “They made it, they accepted that they made it, and I confirmed it.”

In their quest to reach the top, many climbers get 'summit fever', disregarding risks (Credit: Rex)

Yet the jubilant feeling at camp was to be short-lived. Shortly after Smanla called, the weather, which had been steadily deteriorating, broke. The infamous 1996 blizzard had arrived, cloaking the mountain in a fury of snow and wind. Trying to keep his fears at bay, Singh told himself that the men would be fine, that they had dealt with worst weather in the past. If they hustled, they could even make it back to Camp VI by midnight. “However,” he later recalled, “this did not happen.”

Ethics at 8,000m

By 20:00 on the night of Smanla, Paljor and Morup’s ascent, Singh could no longer contain his worry. According to his official account, he decided to approach a Japanese commercial climbing team from Fukuoka for help. Two of the team’s climbers, Hiroshi Hanada and Eisuke Shigekawa, planned to leave for the summit that night.

Using a Sherpa who spoke some Japanese to help translate the conversation, Singh “impressed upon [the Japanese leader] the seriousness of the situation.” Singh reports that, in his presence, the Japanese leader radioed his team at Camp VI to explain the situation, and then told Singh that the Japanese climbers would do all they could to help the stranded Indians if they encountered them on their way to the summit. “The Sherpa [translator] ensured us on his behalf that the Japanese would treat this crisis as their own,” Singh writes.

By morning, the storm had died down and the Japanese were able to set out for the summit. At 09:00, the leader of their team informed Singh that his two climbers had encountered Morup, who was frostbitten and lying in the snow. They had helped him clip into the next fixed line, but then continued on their push to the summit. “We were dismayed,” Singh writes. “The black tea that the Japanese served us tasted black indeed.”

Two hours later, under a “clear and serene sky,” the two Japanese climbers and their three Sherpas passed Smanla and Paljor, but again did not stop or render any help. “Why did they not give even a drop of water to our dying men? What about mountaineering ethics?” Singh writes. “The Japanese had left us with little hope.”

Saving one life is more important than summiting Everest 100 times

The Japanese team, however, later contested this version of events. The “baseless accusations” made against them, they stressed, entirely hinged on flawed, one-sided information. Back in Japan, they held a press conference and issued an official report stating that Shigekawa and Hanada had never been informed that the Indian climbers were in any sort of trouble. While they did encounter several climbers on their way to the summit, Hanada said, “we did not see anybody who seemed to be in trouble or dying.”

The report they issued also emphasised that above 8,000m, “it is common sense” that every climber should be held accountable for their actions, “even on the brink of death.”

The climber’s code of ethics, issued by the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation, specifies “helping someone in trouble has absolute priority over reaching goals we set for ourselves in the mountain.” Most take this to heart. “Saving one life is more important than summiting Everest 100 times,” says Serap Jangbu Sherpa, the first person to climb all eight of Nepal’s 8,000m peaks, and the first to summit K2 twice in one year. “We can always go back and summit, but a lost life never comes back.”

Captain MS Kohli, at his hotel in New Delhi, the Legend Inn

“To say that everyone should look after himself, that no one should help another team is nonsense,” adds Captain MS Kohli, a mountaineer who in 1965 led India’s first successful expedition to summit Mount Everest. “That is absolutely against the spirit of mountaineering.”

After paying many thousands of dollars for safe passage to the summit, what should these climbers’ role be in a crisis?

That simple rule becomes more complicated, however, when commercial clients are involved. After paying many thousands of dollars for safe passage to the summit, it’s less clear what those climbers’ role is, should they encounter someone in need and likewise, it’s also unclear to what extent a guide can be depended on to save a client’s life at the possible cost of his own.

Add to that the fact that, above 8,000m, decision-making and critical thinking skills are severely impaired. “The nearest thing I can compare it to is like being quite seriously drunk, but not fun,” Firth says. As oxygen diminishes, plans and morals formulated at lower elevations often lose their clarity.

Equipment used by Captain MS Kohli on Everest ascents

“People are so fascinated by this when they’re sitting in their living room reading Outside magazine, but the dynamics of what it's like to be up there are really hard to comprehend from down here,” says mountaineer Gulnur Tumbat, an associate professor of marketing at San Francisco State University. Even if a climber wanted to help someone in need, she points out, he would likely be putting his own life on the line to do so. “Above 7,000 or 8,000m, there’s not much you can do,” she says. After experiencing the effects of high altitude herself, she was not surprised to find in her research that people at Everest tend to be individualistic. “There’s actually not that much camaraderie up high on the mountain,” she says. “I’m not saying it’s a bad thing or a good thing – it’s almost necessary to be that way, given the conditions.”

On Everest, people come to the conclusion that traditional rules don’t apply

It also doesn’t help that, for many people – no doubt Shigekawa and Hanada included – a trip to Everest is seen as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. The amount of time, money and energy invested in the mountain can encourage selfish and reckless decision-making. “There’s a mystique to Everest where people come to the conclusion that traditional rules don’t apply, whether that means how much risk they’re willing to take or what the value of reaching the top of the mountain is to them,” says Christopher Kayes, chair and professor of management at the George Washington University in Washington, D.C. “I think the closer you get to your goal, the more likely you are to come up with rationalisations for foregoing morals or values.”

In some cases, he continues, it might “literally mean throwing caution to the wind.” In others, it might mean leaving a fallen climber behind who is deemed beyond helping. (Bierling points out, however, that rescues happen every year – they just don’t make the news like the deaths do.)

Cloud of doubt

Neither Shigekawa nor Hanada responded to interview requests for this story, but Koji Yada, one of the two men’s climbing leaders, recalled the incident to me when I met him in Fukuoka. “As I understood the situation, the [Indian] climbers were wearing heavy equipment, so it was difficult to tell who they were,” he says, adding that he does not know whether Shigekawa or Hanada sensed that the unidentified climbers were in distress.

“I have no idea what I would do if I were in the same situation [as them], but I cannot help thinking that I could do nothing,” he says. “Someone might say that’s inhuman and selfish, but there’s nothing I can do.”

“Eight thousand metres and up is a totally different world,” he continues. “We often use the word self-responsibility to describe the situation there.”

What responsibility should climbers have for their fellow mountaineers? (Credit: Rex)

As with so much that happens on Everest, the events of that May day in 1996 are no doubt clouded by subjectivity, self-interest and the mind-clouding effects of high altitude, and we will likely never really know what transpired in the last hours of Paljor, Smanla and Morup’s lives.

When things do go awry, media frenzies ensue, and the typical reaction is to analyse what went wrong and then distill a handful of lessons learned. A few business schools even use the 1996 Everest disaster as a teaching tool. But some experts believe that there simply is no making sense of what transpires above 8,000m.

“It is difficult to know for sure what really happens during a climbing disaster among teams of ambitious people at 8,000m in howling winds and in a state of hypoxia, dehydration and exhaustion,” says Michael Elmes, a professor of organisational studies at Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts. “I don't think events like the 1996 disaster can be analysed or anticipated, and I’m doubtful that there are ways to prevent future disasters.”

**

Tashi Angmo has trouble recollecting the days following her son’s death. She does remember two men from the Indo-Tibetan Border Police coming to her door and asking if she was Paljor’s mother. They told her that there had been an accident on Everest, and that he was missing. The ITBP had deployed a battalion to search for him, they said, and had even sent a helicopter. But despite their efforts, he seemed to have vanished.

Looking back now, she wonders if the men were telling the truth. “Maybe they looked for him and maybe they didn't,” she says. “But if the right effort had been put in, I believe that he definitely could have been found and saved.”

Leh is home to a branch of the Indo-Tibetan Border Police, Paljor's former employer

After receiving the news, because there was no body, and because the officers told Tashi Angmo that her son was missing – not dead – she spent the next two days travelling to all the local monasteries, performing thimchol, an offering for wellbeing. “It would have been better if they had found the body,” she says. “I kept hoping he’d come back, because they never found the body.”

Eventually, though, her relatives insisted that she face reality. Paljor was not going to be rescued, and he would not be coming home. “‘Missing’ is a term the ITBP is using to relieve you,” they gently told her.

Leh from above

The family eventually held a funeral and also attended a ceremony put on by the ITBP in honour of the three Ladakhi men. “I was like a dead body,” says Tashi Angmo.

Her grieving process was further exacerbated by bitterness that soon developed toward the ITBP. Though officials promised the family that they would be well taken care of, they received an insurance sum of only $3,690, followed by pension payouts every other month of about $36.00 – an amount, Tashi Angmo says, that “won’t even last three days.”

“Shame on ITBP! They are not good!” she told me, weeping. “A child is priceless, money is nothing. But we are the affected family. I lost my child. They should honour their promises.”

Though Paljor died a hero, his family received pittance while his body would remain on the mountain, becoming a morbid fixture of the landscape. When Everest takes a life, it also keeps it. Eventually, he became Green Boots – a climber without a name that people would pass by every year en-route to their own personal glory.

0 notes