#of course quantum physics doesn't actually describe all the observables

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

You ever think about the fact that our best model of the universe at a micro scale, quantum electrodynamics, tells us really nothing about the nature of the universe at that scale? It is, after all, just a model.

Or is it? If quantum electrodynamics is a vector space that covers at least the minimal representation of all observable distinguishing information in a system, is that the same thing as the system itself? No, it's merely isomorphic to the system. But what does "is" mean if not isomorphic to all observable distinguishing outputs?

At the smallest scale, the thing itself is just the information. It is in the interactions between information that the universe arises.

Unless that's not true. Because after all, isomorphism is itself a concept constrained by the conceptual framework in which it exists. Though on the other hand, that framework is powerful enough to describe the ideas of observation and distinction. Though I guess we're maybe relying on the axiom of choice here; if observation and distinction are neither countable nor chooseable it breaks down. But that they are countable is the fundamental assumption of quantum physics. That's the quantum in question.

#physics#philosophy#intoxicated ramblings#i don't know if a thing is more than all the information in the thing#i know that's all a thing is for the purpose of doing science#and for the purpose of observing it#but maybe there's a greater is-ness to things than what can be observed?#though that sounds suspiciously like soul talk#but there is an observable pattern which emerges from the interactions themselves#is that pattern not a thing in its own right?#the pattern is another view on the same information#a different function in the family of solutions#of course quantum physics doesn't actually describe all the observables#it misses gravity#and if gravity were not quantized (or were quantized but in a way that exhibited certain different properties) we can break countability

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy?

And How Does It Work?

(for primarily @phantasyhalation though everyone else who gets subjected to this post can enjoy it as well)

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is an analytical method mostly used by chemists to observe the environments that the nuclei of atoms observe.

It is performed by using extremely powerful superconducting magnets and radio waves.

The magnets look something like this:

(Thanks, University of Minnesota)

The large black object in the center is a very tight coil of wire that superconducts at low temperatures. Superconduction is conduction of electricity with very little to no resistance; this requires a lot less power to run the instrument. The coil of wire acts as a solenoid, creating a STRONG (5+ Teslas; the most common magnetic field used is 9.4 teslas) linear magnetic field pointing upwards through the center of the instrument; it creates a magnetic field pointing downwards around the outside of the instrument (which is very strong if the instrument is not heavily shielded, and still noticeable if the instrument is.) The coil of wire is kept at low temperatures by a chamber outside it containing liquid helium; this liquid helium chamber in turn is cooled by a liquid nitrogen chamber.

Why do we want the magnetic field? Well, all nuclei have an inherent property called "spin." Spin is a property described by angular momentum, which will be important in a moment, but for now, think of the earth spinning on its axis; if the earth was a perfect sphere, you wouldn't be able to see it. A lot of nuclei have a net spin of zero, but they still have spin; in the same way that you can say you are "moving at 0 miles per hour" when you are standing still. (Relative to your frame of reference, of course; we'll be using frames of reference again in the future, so take note.)

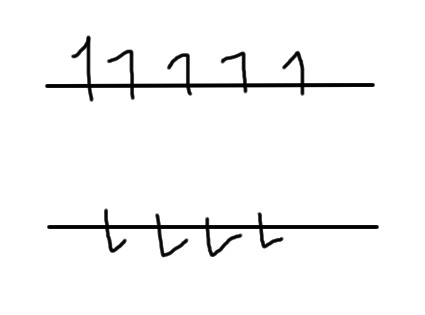

Quantum physics dictates that normally there are 2 spins a nucleus can take: one positive, or "up", and one negative, or "down." Normally, there's a 50/50 chance that a nucleus has spin up or spin down; when a nucleus is near another nucleus that has the opposite spin, it's happy, and won't want to be affected by outside forces like light much.

The above picture shows half and half spin up and spin down nuclei in an abstract representation. (The ones on the top level are pointing up, the ones on the bottom level are pointing down.)

However, placing nuclei in a magnetic field that points up will cause them to be slightly more likely to point up than down, like this:

We call spins that are under the influence of a magnetic field and doing this "polarized". Now, remember what I said earlier about nuclei that are near other nuclei of the opposite spin being happy and unlikely to be affected by outside influences? We now have some nuclei (pointing upwards) that are unpaired, and can be affected by outside forces.

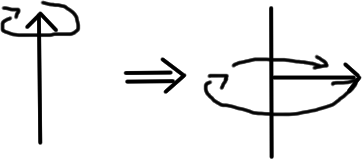

Now, we talked about the earth spinning on its axis earlier. But let's say I tilted the earth over on its side. It would still just rotate on its axis, right? This is NOT the case for nuclei. Nuclei will still try to spin around their original axis- while in actuality they're "pointing" away from it!

(Like this:)

To be clear, what is "pointing" away from the original axis is another property of the nucleus: its magnetic moment. Basically, every nucleus with a nonzero spin creates a tiny little magnetic field; the way that that magnetic field points is called the nuclear magnetic moment.

We call the attempt to spin around the original axis while tilted away from it "precession" rather than "spinning" because it doesn't describe nuclear spin.

But how is this useful to us? Well, I described the tiny little magnetic fields of the nuclei earlier, right? If they're all precessing in unison- or in resonance (moving at the same frequency and pointing in the same direction) their movement is enough to cause a tiny little change in voltage in wires that are nearby. We can measure that change in voltage and look at it; broadly speaking, every atom's nucleus precesses at a different frequency, dictated by the strength of the magnetic field the nucleus is in and the nuclear magnetic moment. This is known as the Larmor frequency.

Pretty useful, right? But how would we tilt the nuclei over? We just have them sitting in a strong magnetic field right now.

Well, our unpaired nuclear spins are back to help. If we hit them with a beam of radio waves at the exact right frequency, and at the exact right angle, for the exact right amount of time, we can knock our nuclei over and get them to start precessing. Normally, we knock them over to be exactly perpendicular to their original spin (90 degrees angled away) but we sometimes knock them over a different amount for various applications.

Now our nuclei are precessing, and creating a small voltage. Eventually, thanks to entropy, they'll get out of sync with each other and cancel the small voltage out (and eventually they'll become realigned with the magnetic field and start pointing upwards again), but this takes a very long time compared to the time it takes a nuclear magnetic moment to cycle once around its axis (on the order of thousands or tens of thousands of times as long). This means that we can look at the nucleus and find out what it is by seeing the frequency that it's precessing at- we take a Fourier transform (taking the change in voltage over time and changing it to the voltage intensity over frequency, so we see at which frequencies of precession the voltage is present at) and see the Larmor frequency; this lets us find out which nucleus we're looking at.

In practice, though, this voltage our nuclei are creating is really really small. So we want to make it bigger so our computer can look at it; we do this with a machine called a preamplifier, which is basically a radio or TV antenna; it's tuned to a range of frequencies, and increases the power of all voltage that it receives of frequencies within that range. In actuality, we know the Larmor frequencies of essentially all nuclei with nonzero spin, so we can simply set the preamplifier tuning around there.

Great! This tells us which nuclei we have. However, there's one small problem; the electronic environment a nucleus is in can alter its precession frequency very, very slightly. This change is measured in millionths of the original frequency- it's very small- but you'd think it would pose a problem for measurement, right?

Not quite. In fact, this is how we determine the structure of molecules. We measure a range of frequencies, not just one, remember? The electronic environment of nuclei is determined by the electrons that surround them; this changes based on where they are in a molecule. Therefore, we set a reference at the Larmor frequency, and see how far certain voltage spikes are from there; by comparing the distance of each peak from the reference frequency to a set of known environments that nuclei can be in as well as to how electron-dense/electron-poor areas within a molecule are, we can figure out molecular structures.

We can do a lot of other things, too (the speed at which our voltage disappears can be used for a lot of interesting things, for example!) but this is the basic way NMR is used by most people.

To finish up: here's the one-dimensional (measuring intensity of voltage over just the change in frequency) hydrogen NMR spectrum of menthol (thanks Wikipedia). Happy spinning!

52 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey frank, how does quantum physics work?

is there a way to simplify it?

I would say a "quantum physicist" (like me) doesn't actually understand quantum physics.

"Quantum mechanics" is the theoretical framework for describing tiny things (like electrons, hydrogen atoms, nuclei, etc.). It's usually presented as a model that can be used for performing calculations, not as an explanation of what we actually observe (as distinct from a proposed explanation that is testable by observation).

The key thing about quantum mechanics is that the underlying mechanics is classical, and yet the resulting model doesn't resemble what we'd call a "classical mechanics" at all.

E.g., in classical mechanics, we normally imagine that particles move along straight lines, like in this video of a drone.

But at the same time, we know from quantum mechanics that the world is made up of tiny little pieces, and that these pieces can behave in strange ways that seem contrary to our classical expectations. What is most strange is that if you can measure an electron's position to high precision, it cannot at the same time be measured accurately in its momentum.

E.g., the electron might move in a circle, like a tiny laser.

This means we can describe reality in the context of quantum mechanics by saying "if you measure the electron's position in a certain region, you'll get a probability distribution in the corresponding momentum region. (Or vice versa.)" We can do experiments in such a way that certain regions in the probability distribution will be made very large and certain regions will be made very small, and the probability distributions will obey a certain kind of set of rules, and this can be very useful in quantum mechanics. It is of course not any kind of classical mechanics, because we can never guarantee to find the electron in a particular place or at a particular speed.

You can never see a single electron. Theoretically, there is only one electron "there" or "not there," but the electron can be in many different places when "there," because we can never see it at a given place and it may move around while we're looking at it. (This is what the electron probability density function tells you.)

Many-particle quantum mechanics is like this too, but on a larger scale. Every single place in space can be filled up with many particles that are described by a density function of their own. When we try to calculate the probability that we'll find a given particle in a given region of space, we are only ever talking about the electron, or some other single particle. This is (as I said earlier) not the same as doing a classical calculation about a particle in a region, because it doesn't deal with a definite particle, but with the density of a collection of particles.

This is all the best I can do with an explanation at 2:20 AM.

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Question: are fictitious forces comparable to imaginary numbers? Is it that the concept of centrifugal force allows certain math problems to be solved, even though it doesn't actually exist, like the number i? or am I way off base? [signed: a confused bio major]

[Image description: a second tumblr ask from archaeopter-ace reading, “(though I definitely agree that the nuance of 'centrifugal force is a fictitous force' is absolutely lost in most physics classes, who are either 100% for or against its existence, and treating it like it's real means kids won't understand how force works properly. Force has to come from somewhere, it doesn't just spring forth from the ether because you need an opposing force to explain what you're seeing)”]

Okay, so bear in mind that I’m an upper division undergrad, and it’s entirely possible that I am missing some aspect that is taught in graduate level courses. Also, whenever I use the word “you” in here, I am using the general you.

So, first off, I’d like to clarify the reason why the imaginary number i* is used in many physics cases is the simple fact that it’s easier to take the integral/derivative of e^(iθt) than it is to take the integral or derivative of sin(θt) or cos(θt). However, no matter if you choose complex exponentials or regular trigonometry, you will get a real answer. This is used for things that are periodic and repeating. Examples of this being used are masses on springs and pendulums, circuitry, and likely many more cases because so many physical systems can be measured as simple harmonic motion.

* Not to be confused with the unit vector î. This is associated with the very real x-direction.

However, in quantum mechanics, the imaginary number i is used for multiple reasons. It’s sometimes used as an exponent of the natural number e in order to avoid using trigonometry for the wave, but it is also multiplied across the entire equation Ψ(t) so that the solution is a real number.

Treating the centrifugal force as a force never makes the math easier, in my experience. However, depending on the frame of reference (aka point of view) you choose, you may or may not need to treat the centrifugal force as a force in order to make the math work.

For example, have you ever been spinning around a mass on a string above your head and then suddenly you let go while still trying to maintain that rotating circle? The mass you’re spinning flies off in a straight line in the exact opposite direction. This is due to inertia (aka the thing that keeps objects in motion staying in that same motion and objects at rest staying at rest unless an outside force acts upon them), although some may call this the centrifugal force. As long as you are in an inertial frame of reference (aka you aren’t accelerating), then the centrifugal force is not a force, but rather the effects of inertia. Newton’s laws of motion work perfectly to describe the motion of you and the object. It is much easier to deal with an inertial frame of reference than a non-inertial one. However, there are situations where the observer is in a non-inertial frame of reference.

Have you ever been driving and you made a hard right turn, only to feel your body shift towards the left of the car? That is not something that Newton’s three laws of motion can explain, not from your accelerating non-inertial frame of reference. They can’t mathematically model how you’re moving... not unless you invent a force that is pulling you towards the left side of the car! In that case, the centrifugal force is something to be treated as very real, and is equal to the mass of the object (aka you) times the squared angular velocity times the distance from the axis of rotation. Of course, someone sitting on the sidewalk (and not accelerating with respect to the Earth) watching you can conclude that you’re experiencing the effects of inertia and that there is no centrifugal force acting upon you.

Now, technically, one can make the claim that gravity is just as real as fictitious forces found in non-inertial reference frames. After all, if you’re in a windowless room and you feel like you’re feeling gravity like you would on Earth, how can you be sure you’re actually on Earth and not just accelerating through deep space at 9.807 m/s²? Einstein made that exact claim and it’s now known as the equivalence principle. However, I would ignore this unless one has to deal with general relativity.

(Other case of a fictitious, non-centrifugal forces in cars include how when the driver suddenly slams the gas pedal, you feel yourself thrown back against the chair. From an inertial frame this is the back of the chair accelerating forward into you, but from your non-inertial frame of reference there seems to be a force shoving you backwards. Likewise, when the car suddenly stops (whether intentionally or unintentionally), you’re thrown forward. From an inertial frame of reference, this is your inertia causing you to move forward even as the car stops. From your non-inertial frame of reference, it seems that there’s a force throwing you forwards. This is why you need to wear a seat belt, because even if you don’t get in trouble with the law for not wearing one, the laws of physics will get you if you’re in a bad enough crash.)

TL;DR: Yes, the concept of centrifugal force allows certain math problems to be solved, even though it doesn't actually exist.

#physics#classical physics#centrifugal force#centripetal force#inertia#stem#science#if any of this doesn't make sense *please* tell me and i will try to better explain it#stemblr#physicsblr#answered ask#archaeopter ace

3 notes

·

View notes