#of course it’s the nyc herald newspaper

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Night Owl News | Alan Wake 2

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today we venerate Benjamin Rucker aka Black Herman on his 134th birthday 🎉

Heralded as the greatest magician in U.S. history, Black Herman was brilliant for his fusion of performance magic with occultism & superstition, and his strong Separatist & militant Pan-Afrikan ideologies (Marcus Garvey x Booker T. Washington). He proclaimed that it was his mission to promote Black Power.

Born in Amherst, VA, as a teen, Black Herman learned the art of illusions from his mentor, Prince Herman. They ran a medicine show, performing magic tricks to attract curious passersby to their "Secret African Remedy". When Prince Herman, 17yr old Rucker was determined to carry on the show; this time using only magic. He then took on the name of, "Black Herman"; in honor of Prince Herman & as an homage to Alonzo Moore, the famous Black American magician who was known as the "Black Herrmann".

In Harlem, Rucker established himself as a pillar of the community. He was often seen in Garvey’s massive Harlem parades & is believed to have offered Garvey spiritual counsel. He befriended preachers, intellectuals and politicians, many of whom met at his home for a weekly study group. He was an Elk, a Freemason, and a Knight of Pythias. He used his success to make loans to local Black businessmen/organisations, established scholarship funds, & performed for free to help churches pay their bills. He expanded his wealth by purchasing a printing plan to establish a monthly magazine, "Black Herman’s Mail Order Course of Graduated Lessons in the Art of Magic". He acquired real estate, bought shares in two cotton plantations, gave personal consultations, & started herb/root gardens in a dozen cities.

Black Herman famously claimed that he was immortal & directly descended from Moses of the Bible. He asserted that our people could elude Klansmen & their descendants by escaping the limitations of mortality & simply outliving them. He'd also sell protective talismans to combat racism. He inserted his Afrikan heritage into his performances. One of his specialties included the “Asrah levitation.” He'd produce rabbits & doubled the amount of cornmeal in a bowl. Many of his tricks were "secrets taught by Zulu witch doctors". Some of his tricks were parallel to miracles from the Christian bible. He'd cast out demons from his assistant or brother hidden amongst the audience, then offer a special tonic for sale & offer a psychic reading address their “problems”.

Yet none compared to his most famous act of all, "Buried Alive". He would be interred in an outdoor area called "Black Herman's Private Graveyard", in full view of his audience. He'd slow his pulse by applying pressure under his arm, & pronounced "dead" on the spot by a local "doctor". As the coffin was lowered into the ground, Herman would slip out unnoticed. For days, people would pay to look at the grave, buidling the suspense over the fate of Black Herman. When the time was up, the coffin was exhumed with great drama and fanfare, and out walked Herman to lead his audience into the nearest theater, where he performed the rest of his show.

Eerily enough, his must famous act foreshadowed his own death in 1934 in which he collapsed on stage due to a massive heart attack that many audience members took to be part of his act. After the crowd refused to believe that the show was indeed over, Black Herman's assistant had his body moved to a funeral home. The crowds followed. Finally, his assistant decided to charge admission as one final farewell & homage to Black Herman's legacy. People came and went by the thousands; some even brought pins to stick into his corpse as proof of his death. His burial made front page news in Black newspapers across the country. Today, Black Herman rests in the Woodlawn Cemetery in NYC.

In 1925, he published a book, ghostwritten by a man named Young entitled, "Secrets of Magic, Mystery, and Legerdemain"; a semi-fictionalized autobiography that offers directions for simple illusions, advice on astrology & lucky numbers, & bits of Hoodoo customs and practices.

"If the slave traders tried to take any of my people captive, we would release ourselves using our secret knowledge." - Black Herman during his rope escape routine.

We pour libations & give him💐 today as we celebrate him for his love & service to our community/people & for his legacied contributions to Hoodoo Culture & History.

Offering suggestions : read his literary works, libations of whiskey/rum, Pan African flag, coins & paper money

‼️Note: offering suggestions are just that & strictly for veneration purposes only. Never attempt to conjure up any spirit or entity without proper divination/Mediumship counsel.‼️

#hoodoo#hoodoos#atrs#atr#the hoodoo calendar#rootwork#conjure#juju#hudu#black herman#Benjamin Rucker#black magicians

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Long, Sad Death of the NYC Newsstand

Up until 2003, New York’s newsstands—those charmingly ramshackle wood-and-aluminum sidewalk constructs where scurrying commuters could grab a morning paper, a pack of smokes and the new issue of Leg Show on their way to the train—were all privately owned and operated by the scruffy characters who inhabited them. All a would-be news dealer had to do was fill out some forms, give the city a check for $1000, and in return they’d receive a two-year license. The license gave them rights to a location, but the costs of building the stand and operating the business was the responsibility of the new owner. That said, within zoning regulations, they could do what they wanted with their stand: paint it whatever garish color they liked, design it after the Taj Mahal, sell Ju-Ju powders along with The Irish Times and racing forms, and keep all the profits at the end of the day. They even, under certain circumstances, maintained the right to sell the newsstand and the license if they so chose. All that changed in 2003, but I’ll get back to that. It was hardly the beginning or the end of the city’s war on newsstands, a war which began soon after newsstands became such an iconic part of New York’s sidewalk landscape.

If we can accept Hollywood films as providing an accurate historical record, ad-hoc open-fronted newsstands had been a familiar and welcome part of daily life in New York since at least the first half of the nineteenth century. Most, again if we accept the Hollywood myth, were owned and operated by gruff but lovable cigar-chomping midgets or preternaturally wise blindos, colorful outsiders who inevitably knew far more about what was going on than what was reported in any of the periodicals they sold. Newsstand operators were the eyes and ears of the community, knew everyone, and acted as invaluable sources for cops and reporters in search of tips. Especially the blind ones.

We may have no choice but to accept the mainstream studio version, as historians seem flummoxed when it comes to pinpointing exactly when or where the first of New York’s newsstands appeared. All they can say for certain is that the hundreds of newsstands that dotted street corners and subway stations across the five boroughs were modeled in function if not form after similar news outlets which had been commonplace in England, France and Italy since the late eighteenth century. But there is at least a small kernel of truth to the mainstream studio version, if you’ll allow me an aside.

For over half a century, thanks to a program spearheaded by the NY State Commission for the Blind, a handful of the city’s newsstands—in City Hall, the King’s County Courthouse, and a select few subway stations—were designated to be run by blind operators exclusively. It seemed a more humane alternative to forcing the blind to sell pencils out of a tin cup. Whether or not these blind news vendors acted as infallible informants for newspapermen and the cops is unknown, but the program was an extremely popular and desirable one within the blind community, allowing those lucky enough to take over a newsstand to earn a living wage. Unfortunately the program was so popular that in the early ’90s I was told the waiting list was so long it would likely be twenty years or more before I was set up in my own operation. Now I have to imagine the wait is even longer, but more about that later, too.

By the late nineteenth century New York’s stand alone sidewalk newsstands had evolved into their iconic form: a shack, usually painted green, constructed of wood and metal, with a low shelf along the front to hold bundles of newspapers, another shelf above that to hold candy and other snacks, and open window through which the proprietor conducted business, with cigarettes and magazines displayed on the wall behind him.

As beloved and essential as the newsstands became among New Yorkers, they’d always had a rough go of it. During the newspaper wars of the 1880s and ’90s, when competing papers quite literally battled each other in pursuit of higher circulation numbers, it was often the newsstand operators who caught the brunt of the violence. If, thanks to personal political leanings or, more often, a little monthly handout, a news vendor opted to carry The World, say, and not The Herald-Tribune, he might find himself beaten bloody by Herald-Tribune deliverymen, his newsstand torched or bombed. A similar fate often also awaited those vendors who, out of respect for the First Amendment or a sense of egalitarianism, refused to play favorites by foolishly carrying all the city dailies.

Not long after the Newspaper Wars were resolved, the city took up the fight to make your average news vendor’s life miserable. In 1911, the city prepared legislation to get rid of newsstands altogether by revoking the owners’ licenses, arguing the stands blocked foot traffic. Newsstand operators banded together against the threat. In a public hearing, the Newsdealers Association President William Merican told members of city council, “Why, there are some men who cannot eat their breakfast without a newspaper. Think of the women in the crush of the subway and elevated. They are exposed to every kind of indignity and hardship. They buy newspapers to make them forget their misery. If the public cannot get their newspapers on the street, they will find the inconvenience intolerable.”

The mayor was swayed by the argument, and the proposed legislation was shelved, at least for a little while.

A decade later in the early Twenties the NY Times took up the fight to do something about what the city’s wealthy and powerful considered an eyesore. Citing the Municipal Art Society’s plans to design polished modernist newsstands that would blend organically with their surroundings, the Times wrote “Why should the sidewalk news stand remain in the architectural class of the squatter’s shanty and the chicken coop? Why shouldn’t it be beautiful or at least not offensive to the eye?”

What the Times clearly didn’t realize was that by then, and over the decades to come, news vendors were not only designing and decorating their stands to reflect the personalities of the owner and the community, but selling things catering specifically to the neighborhood. You can’t get more organic than that. A Financial District newsstand served a different clientele and purpose than one in the East Village, and one in Park Slope served a different clientele and purpose than one in Flushing. (Well, at least that was the case in the twentieth century, even if it isn’t anymore.)

A number of newsstands, especially in the outer boroughs, evolved into mini community centers, with folks from the neighborhood hanging out with the owner to catch up with the news and each other. Some vendors gave their stands unique paint jobs (in some instances adorning the sides with murals), others hung Chinese lanterns or installed awnings, while still others abandoned the standard shack format altogether for more architecturally interesting designs. Despite the general perception, virtually no two stands were identical.

Ignoring (or more likely unaware of) this, the city pushed ahead with their efforts to beautify the stands,. In the ’50s and ’60s the city began once again drafting plans and sponsoring contests with an eye toward replacing the glorified chicken coops with sleek and uniform metal and glass designs, but none of their efforts went anywhere. Beyond that, there were the seemingly bi-annual efforts mounted by city council and various morality watchdog groups to ban the sale of porn. Every time the city pushed on this issue, the newsstand operators once again pushed back, arguing that porn sales represented a huge percentage of their annual profits, and by taking that away, the city would be putting them out of business.

In 1987, Hudson News was founded. Hudson News was an international chain operation, essentially the Taco Bell of storefront newsstands, whose slick and jazzy neon logo quickly became a familiar sight in airports and train stations across the country. It seems Hudson News represented exactly what New York officials had been looking for since the turn of the century. After grabbing spots in Penn Station, Grand Central, JFK and LaGuardia in the early ’90s, Hudson News and the city both took aim at the newsstands in the subway. Suddenly it was argued that the newsstands which had been there forever were not only obstructions to commuter movement, but blocked police sight lines on the platforms as well, preventing them from stopping crime. It was an insane argument no one had brought up before, but it worked. Before long, a number of the old subway newsstands were replaced with stand-alone Hudson News kiosks. The ironic thing of course, is that the Hudson News stands were much bigger and brighter, presenting even more of an obstacle to commuters and cops alike. But they were much nicer looking and covered with neon piping, so that was okay.

For the moment anyway, the sidewalk newsstands were safe.

Then along came Rudy Giuliani, The new Law and Order mayor who made his own bid to get rid of New York’s newsstands. Along with his efforts to scrub the city clean of porn, Giuliani argued the newspapers sold at these stands sometimes blew away, adding to New York’s litter problem. The only solution, as part of his Quality of Life campaign, was to get rid of the newsstands altogether. Once again the vendors and their customers alike pushed back.

Although Giuiliani was able to clean up Times Square and Coney Island, by the time he left office those sloppy newsstands remained steadfast, and New Yorkers were still wandering knee-deep in scattered fluttering pages of The Financial Times and The Guardian.

It took his successor, Michael Bloomberg, to do what Giuliani couldn’t. Always with a mind toward the tidy and seemly and sterile, Bloomberg had long found the city’s newsstands an eyesore. In 2003 he signed what was called The Street Furniture Bill. As he put it, the aim of the bill was “to rationalize the streets of the city, where right now it's a hodgepodge of unattractive things.” The quote says a lot about Bloomberg, how he perceived New York, as well as how and why NYC turned into Des Moines.

With an eye toward faceless uniformity, the city cut a deal with the Spanish company Cemusa to design not only clean and pleasant newsstands, but matching public toilets and other bits of street furniture as well. Soon, it seemed, Bloomberg would have his dream, and wherever you went in New York, it would look just like every other part of New York.

Four years later, the city began seizing those ugly hodge-podge newsstands away from their longtime independent owners, people who had in some cases owned and operated their own newsstands for forty years or more, replacing them with identical steel and glass boxes decorated with enormous digital ads. In a blink, those faces you saw behind the newsstand windows were now mere employees, and all profits from those digital ads went straight to the Cemusa company.

By 2009, over 200 old newsstands had been removed, replaced by 300 sleek and shiny boxes with those goddamn digital ads all over them. But by then it was a moot point. With the internet killing off newspapers and magazines, and with everyone staring dead-eyed into phones instead of picking up a copy of the Daily News on the fly, newsstands themselves became all but irrelevant. As quickly as those slick and flashy boxes appeared, they began to vanish. Nowadays you’d be hard pressed to find a sidewalk newsstand anywhere in New York, though there are still a few in the subways and train stations, where Hudson News is still king.

In a final and ironic insult, in 2013, long after most of New York’s newsstands were nothing but a grubby and fading memory, every last one of them operated by Angelo Rossitto in a newsboys cap, the city spent an estimated $90,000 on a new newsstand design to replace the one which had been in the lobby of the Brooklyn criminal courts building for over forty years. As that had always been one of the stands set aside for blind operators, the primary goal of the new design was that it be blind accessible.

Once completed, it was discovered this fancy new newsstand, which had been designed with absolutely no input from a single blindo, let alone the one who would be working there, was not in the least accessible, and so had to be scrapped. The city then dumped even more money into yet another design, but by then it was too late. No matter how popular and valuable that State Commission for the Blind program was, the New York newsstand had gone the way of the dodo, making the hubbub over the blind-friendly design for the Brooklyn courthouse irrelevant.

I can’t help but suspect the city’s alleged good-hearted move to do something decent for the disabled community (one member of it, anyway) in fact cloaked a deeply cynical effort to deal out one last fatal blow in the century-old effort to do away with newsstands altogether, making the city that much less interesting.

Well, they got what they wanted, though aesthetics aside, the more conspiratorial sections of my brain still wonders what was really behind the push.

.by Jim Knipfel

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artist Research...

(1) Boogie-Street & Documentary Photography...

Boogie will blow your mind.

The native of Belgrade, Serbia got his start began documenting rebellion and unrest during the civil war that ravaged his country in the 1990s, and the experience seemed to have a profound effect not only on him, but on his work as well. Though Boogie now resides in New York – he arrived in 1998 – all of his work still carries the urgency and thought-provoking depth of a war-torn country.

Perhaps it’s because Boogie’s latest photographs focus on lives torn apart – from the runaway smoking crack in a drug den that used to be a hospital to the gang member caught in a moment of tenderness while cuddling his newborn child. Boogie appears to have shot everything, everywhere. Beggars on the streets of Caracas, Skinheads in Serbia, birds caged by power lines in Tokyo – the world looks more moody, evocative and meaningful through Boogie’s lens. Every detail takes on a life of its own.

Unsurprisingly, the photography world has taken notice – Boogie has published five monographs and exhibited around the world. He shoots for high end clients, renowned publications and countless awe-struck eyes worldwide.

Daniel: Tell us about yourself, where did the name Boogie get picked up and what’s the story behind it?

Boogie: I’m 40 years old, born and raised in Belgrade, Serbia, moved to NYC in 1998 after winning a green card lottery; I’ve shot a lot, published 5 monographs so far, had some interesting solo exhibitions. My nickname was given to me by my friends some 20 or so years ago after a character from some scary movie.

Daniel: You do a lot of “candid” or better yet documentary photography. Are you always geared with a camera where ever you go?

Boogie: Of course, I’m a photographer, that’s what I do

Daniel: Lots of Gangs, Drugs, Skinhead photography. That screams trouble, are you not afraid meeting with these people, taking their photographs? Have you ever encountered trouble? – How do you approach these people at first?

Boogie: While I was photographing gangsters, skinheads, junkies, it never crossed my mind to be afraid. Otherwise I wouldn’t have been able to get those photos. People can sense fear easily – plus, I don’t think any photo is worth risking your life for. I encountered some minor problems, but nothing serious, after all I’m still here. I always listened to my instincts, they kept me safe.

There is no recipe for approaching people. You either have it in you or you don’t. Usually if you treat people with respect they’ll be OK with you.

Daniel: You’ve recently signed a deal with HBO’s new show “How To Make It In America” what were your feelings when you first heard HBO was interested in featuring your photography, and what do you think about the show?

Boogie: It was a great gig, I met some very interesting people and got to know how the movie industry works. I haven’t seen the show, just the pilot, which I liked.

Daniel: Here’s a funny question wrapped around the HBO show – so When did you know you finally made it, as a photographer in America

Boogie: ‘Making it’ is very relative. I made it as a human being cause I have a great family and get to do what I love.

Daniel: Have you ever thought of shooting film?

Boogie: You mean moving picture? If so, while working on this HBO show, I realized that being a director of photography is an amazing job. Maybe the only job in the world I would trade for mine.

Daniel: What is your connection with photography, your personal life, and your photographs of poverty?

Boogie: Maybe the way I grew up led me to see things the way I do? I guess so, everything you go through in life has a purpose and influences what you become in the end.

Daniel: Tell us about the shoot in Brazil Sao Paolo, how was it?

Boogie: It wasn’t ‘a shoot’, I just packed my bags and went there for a week. very intense, I shot in some scary neighborhoods, I published a book after, all good.

Daniel: What was Mexico like, where did you visit?

Boogie: I was in Mexico City with a friend of mine Adrian Wilson … it’s an amazing city, great energy, great people. Al these horror stories they tell you before you go there are bullshit. Although I’ve been in some neighborhoods where I was afraid to shoot even from the car. But you have areas like that wherever you go.

Daniel: I know you’ve visited Cuba, Istanbul, Tokyo in addition, what is it that you learn from these trips?

Boogie: Travels are always great experiences, seeing how other people, other cultures live is priceless. It humbles you in a way, makes you appreciate what you have more.

Daniel: Lots of black and white, lots of flying birds. What is it that you like the most about Black & White?

Boogie: No idea, lately I also shoot a lot of color.

Daniel: Which gallery is your personal favorite?

Boogie: You mean on my website? everything there needs an update …

Ref: bloginity.com

Robert Frank

Influential photographer and filmmaker Robert Frank has died at the age of 94. He died of natural causes on Monday night in Nova Scotia, Canada. His death was confirmed by his longtime friend and gallerist Peter MacGill.

He was best known for his 1959 book The Americans, a collection of black-and-white photographs he took while road-tripping across the country starting in 1955. Frank's images were dark, grainy and free from nostalgia; they showed a country at odds with the optimistic views of prosperity that characterized so much American photography at the time.

His Leica camera captured gay men in New York, factory workers in Detroit and a segregated trolley in New Orleans — sour and defiant white faces in front and the anguished face of a black man in back.

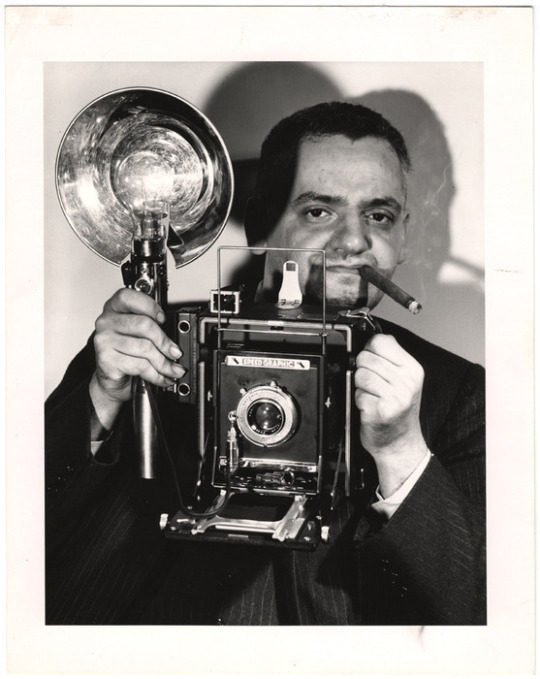

Photographer Robert Frank holds a camera in 1954. His photo book, The Americans, changed the way people saw photography and the way they saw the U.S. Frank died on Monday at the age of 94.

Fred Stein Archive/Getty Images

Influential photographer and filmmaker Robert Frank has died at the age of 94. He died of natural causes on Monday night in Nova Scotia, Canada. His death was confirmed by his longtime friend and gallerist Peter MacGill.

He was best known for his 1959 book The Americans, a collection of black-and-white photographs he took while road-tripping across the country starting in 1955. Frank's images were dark, grainy and free from nostalgia; they showed a country at odds with the optimistic views of prosperity that characterized so much American photography at the time.

His Leica camera captured gay men in New York, factory workers in Detroit and a segregated trolley in New Orleans — sour and defiant white faces in front and the anguished face of a black man in back.

Trolley – New Orleans, 1955.

Robert Frank/National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Maria and Lee Friedlander

The book was savaged — mainstream critics called Frank sloppy and joyless. And Frank remembered the slights.

"The Museum of Modern Art wouldn't even sell the book," he told NPR for a story in 1994. "I mean, certain things, one doesn't forget so easy. But the younger people caught on."

Eventually, the photographs in The Americans became canon, inspiring legions. Photographer Joel Meyerowitz remembered watching Frank at work early on.

"And it was such an unbelievable and powerful experience watching him twisting, turning, bobbing, weaving," Meyerowitz said in 1994. "And every time I heard his Leica go 'click,' I would see the moment freeze in front of Robert."

Restaurant – U.S. 1 leaving Columbia, South Carolina, 1955.

Robert Frank/National Gallery of Art, Washington, Robert Frank Collection, The Robert and Anne Bass Fund

Ginsburg was a friend and photography student of Frank. He also starred in Frank's first film, 1959's Pull My Daisy. It was based on part of an unproduced play by Jack Kerouac and featured the author as narrator.

Pull My Daisy, and the other experimental, autobiographical films Robert Frank made, were his reaction to a restlessness he felt around still photography.

"In still photography, you have to come up with one good picture, maybe two or three," he told NPR in 1988. "But that's only three frames. There's no rhythm. Still photography isn't music. Film is really, in a way, based on a rhythm, like music."

Yet Frank's films shared a lot with his photographs. They were personal; they evoked emotions as much as they told stories. They're like home movies, and he made more than 20 of them before returning to photography. By then, he was a legend, acknowledged as an inspiration by such noted artists as Ed Ruscha, Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand.

What comes through in all of Frank's work is his ability to catch a moment. And that came from truly looking.

"Like a boxer trains for a fight, a photographer, by walking the streets, and watching, and taking pictures, and coming home, and going out the next day — same thing again, taking pictures," Frank said in 2009. "It doesn't matter how many he takes, or if he takes any at all. It gets you prepared to know what you should take pictures of.

_______________________________________________________________________

(2) Weegee (1899 - 1968)

Biography

Weegee, born Usher Fellig on June 12, 1899 in the town of Lemburg (now in Ukraine), first worked as a photographer at age fourteen, three years after his family immigrated to the United States, where his first name was changed to the more American-sounding Arthur. Self-taught, he held many other photography-related jobs before gaining regular employment at a photography studio in lower Manhattan in 1918. This job led him to others at a variety of newspapers until, in 1935, he became a freelance news photographer. He centered his practice around police headquarters and in 1938 obtained permission to install a police radio in his car. This allowed him to take the first and most sensational photographs of news events and offer them for sale to publications such as the Herald-Tribune, Daily News, Post, the Sun, and PM Weekly, among others. During the 1940s, Weegee's photographs appeared outside the mainstream press and met success there as well. New York's Photo League held an exhibition of his work in 1941, and the Museum of Modern Art began collecting his work and exhibited it in 1943. Weegee published his photographs in several books, including Naked City (1945), Weegee's People (1946), and Naked Hollywood (1953). After moving to Hollywood in 1947, he devoted most of his energy to making 16-millimeter films and photographs for his "Distortions" series, a project that resulted in experimental portraits of celebrities and political figures. He returned to New York in 1952 and lectured and wrote about photography until his death on December 26, 1968.

Weegee's photographic oeuvre is unusual in that it was successful in the popular media and respected by the fine-art community during his lifetime. His photographs' ability to navigate between these two realms comes from the strong emotional connection forged between the viewer and the characters in his photographs, as well as from Weegee's skill at choosing the most telling and significant moments of the events he photographed. ICP's retrospective exhibition of his work in 1998 attested to Weegee's continued popularity; his work is frequently recollected or represented in contemporary television, film, and other forms of popular entertainment

0 notes

Text

BETWEEN THE BRIDGES

A few years ago I did a feature on Manhattan between the Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridges (I call it BEMBO), but as always, there’s more to see and there are details I missed. This time of year I also begin to scout areas that would make decent Forgotten NY tours in the spring and summer. BEMBO is a curious area, full of crannies and nooks of interest. Had I been writing Forgotten New York in the 1960s, there would have been a lot more to talk about, as maybe half of this neighborhood has been razed to build housing projects, schools, and the NYPD headquarters. I was able to show some of these lost streets in a FNY post in January 2019.

Getting off the F train at East Broadway at Canal (Straus Square) I meandered west. I discussed the Mesivtha Tiferes Jerusalem Yeshiva just the other day, so I won’t repeat myself here; it’s a handsome building in buff and brown brick, and has a venerable history.

East Broadway, looking west, looking toward the Manhattan Bridge overpass, and behind it, the Municipal Building and Woolworth Building, which from this vantage look like twin spires of the same building. In the left background is #4 World Trade Center and on the right, of course, is #1 World Trade Center. In the foreground left is the relatively new 109 East Broadway, the site of a devastating fire in 2010. The building exhibits the latest trend in residential architecture, featuring a boxy design with colored metal panels and flat windows. Why do so many new apartment buildings looks like this? They’re the cheapest to build.

In FNY’s Comments section, and remarks from friends on facebook, twitter and in person, many dismiss new architecture outright, saying nothing built today matches the past. I judge each building on its merits, and part of me is happy to live in a dynamic city that can accommodate new designs. I like a city that has both a Jenga tower and a St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

Until the beginning of the 20th Century, East Broadway was known as Chatham Street, for William Pitt, Earl of Chatham (1708-1778) who was the English Prime Minister during the time the colonies were agitating for independence, but before the Revolutionary War. He opposed the Stamp Act, but also opposed outright independence, but promoted compromise that ultimately proved untenable. Many USA locales are named for him including Pittsfield, MA and Pittsburgh, PA, as well as Chatham Square, East Broadway at the Bowery.

No good way to get a picture of the Knickerbocker Post Office, 128 East Broadway near Pitt Street because of … all the mail trucks parked in front of it.

Washington Irving (1783-1859), who met his namesake George Washington while a young boy, was popular both in the States and in Europe for his essays and fiction, and was the creator of Ichabod Crane, Rip van Winkle, and the tricornered Father Knickerbocker, NYC’s mascot. “Knickerbocker,” which is fun to say, refers to NYC’s early Dutch settlers and appears frequently in NYC lore, including its NBA basketball team.

The Sung Tak Buddhist Association at 13 Pike Street was once the Pike Street Synagogue, a Classic Revival building from 1903 that housed the Congregation Sons of Israel Kalwarie, Poland. Entertainer Eddie Cantor was bar mitzvahed here in 1905. The tripartite façade, which has an arched portico reached by twin lateral staircases, reflects Romanesque and classical features.

Looking north on Pike Street, which was named for explorer Zebulon Pike, soldier and explorer (1779-1813) of Pike’s Peak fame. Along with Allen Street, which begins a block north, the road was widened several decades ago and now sports a modern bicycle path. You can walk in a straight line all the way from here to the Harlem River, as Pike becomes Allen and Allen becomes 1st Avenue.

Turning left on Market Street, I encountered one of the oldest churches in Manhattan at Henry Street, the old Market Street Reformed Church, which was built in 1819. The windows are made up of multiple panels—35 over 35 over 35. This is now the First Chinese Presbyterian Church, which shared the building with the Sea and Land Church until 1972.

The brick and stone Georgian-Gothic church was constructed two centuries ago as the Market Street reformed Church on land owned by Henry Rutgers, and after changing congregations a few times over the years, it’s now the First Chinese Presbyterian Church. It’s in the top five oldest extant church buildings in New York City, the oldest being St. Paul’s Chapel on Broadway and Vesey St.

Every time I’m in the area, I check on Mechanics Alley, which runs on the west side of the Manhattan Bridge anchorage for 2 blocks between Madison and Henry Streets. Though it has obtained a more narrow sense, the word “mechanic” originally meant an artisan, builder or craftsman, not necessarily a machinist. No property fronts on the narrow lane, but trucks nonetheless employ it despite its narrowness to avoid heavier traffic on streets like Market.

I did a pretty comprehensive post on Mechanics Alley and its history a few years ago in FNY.

Market Street contains a number of historic and classic buildings along its short stretch between East Broadway and South Street. Here’s #40 market on the corner of Madison, which still has its original entrance woodwork as well as the street identification brownstone plaques. The Market Street side looks as if it has had some ad hoc repairs done sometime in the past.

375 Pearl Street, otherwise known as the Verizon Building, a.k.a. the Intergate Center, looms at the west end of Monroe Street. Many call it the ugliest building in Manhattan, though I’ve seen far worse. In 2016 it was renovated and received a new bank of windows.

This shabby brick building at 51 Market St. was constructed in 1824 by merchant William Clark. Its original elegant doorway, with Ionic columns, a fanlight and ornamentation, has survived nearly two centuries. A close look at the basement windows shows them to be surrounded with brownstone work with squiggly lines, known in the architecture world as “Gibbs surrounds.” A fourth floor, which studiously copied the original three, was added after the Civil War. The stoop and railings, however, are not original as they were replaced in 2010. The door is festooned with graffiti, and though the house has Landmark status, its condition appears deteriorated.

Amid the Chinese-language signs on Market and Madison, at the edge of Chinatown, is this neon sign for a long-gone liquor store.

At #47 Market Street is a venerable brick building that conveniently lists the date of construction, 1886, at the roofline.

Faces peer out from the front of this Madison Street apartment. Many of these buildings, and those on paralleling Monroe and Henry Streets, were built in the 1880s, when such embellishments were found on just about every building, commercial or residential.

The undulating exterior of #8 Spruce Street, officially New York By Gehry, named for architect Frank Gehry, is the architect’s signature NYC building. Like it or not, it’s instantly recognizable from all over lower Manhattan. After its completion in 2011, it was NYC’s tallest residential building for a couple of years, but has since been surpassed by buildings like 432 Park.

The Roman Catholic parish of St. Joseph (“San Giuseppe”) was established by the Missionaries of St. Charles, an order of priests and brothers founded by Blessed John Baptist Scalabrini in 1887 to serve the needs of Italian immigrants. The present church was designed by Matthew W. Del Gaudio and opened in 1924. Shortly after the founding of the parish, the Scalabrinians were joined by the Apostles of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, who helped open St. Joseph School in 1926.

Today, St. Joseph Church is a national parish designated as an Italian and Chinese parish. The parish continues the mission of the Church of St. Joachim, located at 26 Roosevelt Street until the 1960s, which was founded by the Missionaries of St. Charles who arrived in New York City in 1889. Immediately after, Mother Cabrini was welcomed by the same church as she arrived in the United States. American Guild of Organists, NYC Chapter

Speaking of the Scalabrinians, in January 2018 I visited their former bailiwick, St. Charles Seminary in Todt Hill, Staten Island, which had been the estate of architect Ernest Flagg.

Catherine Street classics, near Madison Street.

Madison and Oliver Streets. Al Smith (1873-1944), a four-time NYS governor and failed presidential candidate, was born on Oliver, a still-existing street between the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges, neither of which had opened when he was born. He was one of NYC’s most popular politicians in history.

On a walk up the Lower East Side in January 2013, I encountered an anachronistic building that I either hadn’t seen or hadn’t noticed before, on Madison Street a few doors away from St. James Place. It’s a tiny two-story dormered building — however, it’s not too small that it doesn’t have two separate doors and two separate house numbers, 47 and 49. I’ve always been curious about anachronisms and survivors, being something of an anachronism myself, so I looked it up. Expecting a difficult or fruitless search, I found something by the historian David Freeland, who rote about it in 2009 in the now-defunct New York Press:

For years the house has been something of a mystery, but one glimpse into its colorful history is revealed through a small advertisement from the Spirit of the Times newspaper, as reprinted in the Boston Herald of March 2, 1853: “Rat Killing, and other sports, every Monday evening. A good supply of rats kept constantly on hand for gentlemen wishing to try their dogs, with the use of the pit gratis, at J. Marriott’s Sportsman’s Hall, 49 Madison Street.”

Rat baiting, setting rats against rats, or dogs against rats, was a popular betting sport in the 19th Century in the days before the ASPCA. The building where another former rat baiting establishment was run by Kit Burns, the Captain Joseph Rose House, still stands at 273 Water Street in the Seaport area.

Freeland goes on:

By the late 1850s, the house at 49 Madison Street had been taken over by English-born Harry Jennings, who ran it as a combination saloon and rat-fighting pit until his conviction on a robbery charge sent him to prison in Massachusetts. But later, after returning to New York, Jennings settled into a kind of respectability, winning fame as a dog trainer and, eventually, the city’s leading rat exterminator. By the time of his death, in 1891, Jennings’ clients included Delmonico’s Restaurant and such luxury hotels as Gilsey House and the original Plaza.

Apparently, there’s a comeback in everybody.

The dark shadows of January intrude on the intersection of James and Madison Streets, one of the few intersections in NYC where both street names make up a US President’s first and second name. I’m sure it wasn’t planned that way, though.

We can see St. James Church, the second oldest building associated with the Roman Catholic Church in NYC. (Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Mott and Prince Streets, built in 1810, precedes it.) The fieldstone, Doric-columned Greek Revival building was begun in 1835 and completed in 1837; and though it is thought to be a design of famed architect Minard Lefever, there is no evidence to support the claim. A domed cupola above the sanctuary was removed decades ago. This was the boyhood parish of Al Smith, and New Bowery, which connects Pearl Street and Chatham Square, was renamed for it in 1947.

The massive Chatham Green development, located along St. James Place between Madison Street and Chatham Square, opened in 1960, was one of the projects that eliminated much of the ancient street grid in lower Manhattan, as well as the last remnants of the Five Points slum. But on those streets were located dark, noisome and cold tenements, and Chatham Green was constructed by the City in an effort to make middle-income peoples’ lives better. As we know, that effort has had mixed results.

Chatham Green went condo several years ago, with hefty prices, somewhat belying its original purposes.

This triangular-shaped building comes to a point at St. James Place and Madison Street. As I have noted, St. lames Place, laid out in the mid-1850s, was originally called New Bowery, but the designation must have been fluid at one time, as the chiseled street sign on the building simply has “Bowery.”

One Police Plaza, along Madison Street and Park Row (both closed to regular traffic) opened in 1973, is the headquarters of the NY Police Department; it took over from the old domed HQ, now a condo conversion at Centre and Broome Streets. It was designed by Gruzen and Partners in a Brutalist style and sits near the assorted city and state court buildings at Foley Square.

The NYC Municipal Building was constructed in 1914 from plans by McKim, Mead & White; it now houses only a fraction of the city offices that oversee the functioning of the metropolis. Particularly attractive is the row of freestanding columns, the extensive sculpture work and the lofty colonnaded tower topped by Adolph Weinman’s 25-fot high gilt statue of Civic Fame.

I have happy memories of the building since on October 23, 2006 I spent a half hour with Brian Lehrer on WNYC-radio discussing Forgotten NY the Book, and temporarily, my Amazon sales jumped into the 500s (by contrast, 12 years later, I’m in the 300,000s usually).

The sculptures on the north arch include allegorical representations of Progress, Civic Duty, Guidance, Executive Power, Civic Pride and Prudence. Between the windows on the second floor are symbols of various city departments. Note the collection of plaques, among which is the “triple X” emblem of Amsterdam, Holland. Chambers Street once passed through the building and once went all the way to Chatham Square but the NYC Police Dept complex was built over its path in the 1960s. —Gerard Wolfe

The fortress-like, business-themed Murray Bergtraum High School was built at Madison Street and Robert F. Wagner Senior Place, adjacent to Brooklyn Bridge off-ramps, in 1976. It’s named for a former president of the NYC Board of Ed., between 1969 and 1971. Noted alumni include entertainers John Leguizamo and Damon Wayans.

Rose Street, once chockablock with tenements, is a curved street running under the Brooklyn Bridge connecting Gold and Madison Streets. It was named for late 18th-early 19th Century merchant and distiller Captain Joseph Rose, whose house still stands nearby on Water Street. I discussed Rose Street at length on this FNY page.

Though I continued into the Seaport area, it’s a busy weekend and I’ll wrap things up for now.

Please help contribute to a new Forgotten NY website

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

1/6/19

Source: http://forgotten-ny.com/2019/01/between-the-bridges/

0 notes

Text

What A Long Staid Trip It's Been...

Last week, following the revelation that I am riding a new road bike, I received a fresh wave of accusations that I had sold out, or "jumped the shark" (presumably from people still accessing the Internet via dial-up modem and AOL given the hoariness of the expression), or other hackneyed phrases denoting the forfeiture of integrity. While my addressing these comments may seem defensive, I can assure you that I delight in the irony. Granted, by some measures I live a sumptuous lifestyle: hot and cold running water, streaming television, and a wide variety of savory Trader Joe's snacks available to me at any given time. Nevertheless, most of us have a fairly specific image in our minds when we imagine what "selling out" looks like, and I'm fairly confident in assuring you that this ain't it. Of course, as I've mentioned before, people have accused me of selling out for nearly as long as I've been typing this blog. At this moment I don't have the time or the energy to find the first instance of it, but certainly when I announced my then-new Bicycling column in 2009 the pronouncements came fastly and furiously: Anonymous said... Did any of you podium twits read the column? He called you assholes and told you to suck his balls while he collect$ from glossy magazines. MARCH 19, 2009 AT 1:09 PM AshevilleMountainBikeRacing said... Jeez. You could have at least gone with a real bicycling magazine, instead of this "Bicycling" magazine which from my perspective has nothing to do with bicycling whatsoever. I'm going to the bathroom to vomit, now. MARCH 19, 2009 AT 1:12 PM carlos said... The shark has been jumped!!! MARCH 19, 2009 AT 1:12 PM Yes, the shark had been jumped, and the passive voice had been employed! It all seems so quaint now. By the way, looking back at that post, I particularly enjoyed this quote from the Bicycling press release: “After months of begging,’” says Mooney, “BikeSnobNYC finally agreed to bring his unparalleled wit and sense of style to the readers of Bicycling.”

That is so not how it happened at all. Anyway, I'm especially enjoying this latest round of derision since it gives me an excuse to explore my favorite subject, which is myself. More specifically, it raises what is for me a compelling question: while present-day me is certain he has not sold out, what would the idealistic long-time-ago me think? In other words, if 30 years ago I could see myself right now, would I pass muster in the eyes of a teenager who held anything mainstream in utter contempt? By way of illustration, here is 30-years-ago-me:

(Photo: Danny Weiss)

I'll allow there's a case to be made that I'd already sold out by wearing a Danzig shirt, and I'm pretty sure that's also a Swatch on my wrist, but I ask that I be judged in the context of the times. Obviously the simplest way of determining whether or not someone is a sellout is analyzing how they earn their livelihood, so in an act of unprecedented disclosure I'm going to go through my entire resume, starting with my very first paying job:

BSNYC/RTMS/Tan Tenovo Professional Resume and/or Curriculum Vitae

16 Years Old Or Thereabouts: Stockboy At a Neighborhood Drugstore

Proprietor let me go after a couple weeks. He claimed he needed someone with a drivers license to make deliveries, the real reason was probably that I was incompetent. Sellout Status? Not yet, because it was an independently-owned business and not like a CVS or something.

16 Years Old, Through High School, and On And Off Through College When I Was Home For Vacations Or Whatever: Stockboy/Cashier/Schlepper/Delivery Boy/Taker Of Abuse At a Neighborhood Hardware Store

I hated every waking moment of this job but I learned a lot about life, people, and, for awhile anyway, hardware. (Though I've since expunged it all from my brain.)

Sellout Status? I suppose working at a job you hate is a kind of selling out, but I always knew I wouldn't be doing it forever, and also it was an independently-owned business. Plus, hardware is like totally blue collar, even if half the customers were buying Weber barbecue grills and filters for their expensive central air conditioning systems.

17-21 Years Old: SUNY Albany Art Gallery Assistant

My work-study job in college was helping out at the art gallery. Mostly this involved sitting at a desk doing nothing but occasionally I'd bring my hardware store skills to bear by painting a panel or hanging some art.

Sellout Status? Oh come on.

20-21 Or Thereabouts: Intern/Assistant At a Book Publishing House

Towards the end of college I got it into my head I wanted to work in book publishing, so I started interning at a pretentious small press (I realize that's redundant, all small presses are pretentious) in SoHo. The other interns were all Barnard students who had absolutely no interest in being there, which was great for me because it created the impression that I had a work ethic. I worked for free but eventually they started paying me and after I graduated they helped me get a real job.

Sellout Status? Scrappy SUNY student stealing low-paying job from apathetic Ivy Leaguers? That is a blow for the proletariat! (If by "proletariat" you mean suburban English majors.)

21 to 23 or 24 Or Thereabouts: Assistant At a Book Publishing House

This was my first "real" job, and it was at one of the big publishing houses. Once again, the fact that most of my work peers had come from fancy private schools and were fairly unmotivated created the illusion I was a highly driven go-getter. However, once it became clear I'd actually have to work hard in order to succeed, I left under the guise of "finding myself" or something.

Sellout Status? I mean sure, it was a big company, but it was a big company that publishes books, not a pharmaceutical company that gets people hooked on opioids.

24-Ish I Guess: Bike Messenger, then Assistant to Film Director

I'm lumping these together because I think the total time I spent at both jobs was only like a year, and in a way they were similar in that I mostly ran around bringing stuff to people who were indifferent to me.

Sellout Status? Being a bike messenger is being a bike messenger, and the film director was Michael Moore, so I don't think the kinds of people who accuse people of "selling out" would consider either to be selling out.

Mid-20s to Mid-30s: Incompetent Literary Agency Associate

After experiencing life as a film industry assistant, which mostly involves people with enormous egos ripping your guts out on a daily basis, I went running back to publishing like a toddler with a boo-boo and proceeded to hide from the world by working at a literary agency for the next 10 years.

Sellout Status? Sucking at your job just badly enough not to get fired isn't exactly commendable behavior, but I don't think it technically qualifies as "selling out." Plus, it was a small company that represents people who write books, not some evil corporation.

Mid-30s On: You're Looking At It

Writing about bikes.

Sellout Status? Please. I write about bikes. Sometimes I appear in a major publication and say stuff like drivers shouldn't be allowed kill people Let's get real.

So there you go, that's my resume, and I don't think the teenager who used to struggle emotionally when a band he liked signed to a major record label would be too offended by my career trajectory, downward as it may be. In fact, thanks to this slightly embarrassing newspaper clipping from like the Nassau Herald or something, I daresay I fulfilled my modest ambitions:

(I must have been home from college for the summer, working in the hardware store, and bored out of my fucking mind.)

As for what present-day me thinks upon looking back of it all, I'd certainly maintain that I haven't sold out, though I sure have squandered a shitload of incredible opportunities, which is easily about a thousand times worse.

And yes, I know what you're thinking: "You're not telling the whole story. What about household income? Your wife probably does something evil." Okay, you got me, she's an attorney who works for a fossil fuel industry lobbying group.

Just kidding!

Actually she publishes young adult literature, a vocation I'd argue positively oozes integrity.

But it's one thing do say you haven't sold out just because you don't have fuck-you money and a yacht called the "Just Kidding." It's another to say you haven't sold out because someone actually offered you fuck-you money and you refused to take it. I certainly can't claim to have done that. Oh, sure, I've turned down opportunities and told myself I did so because I had integrity, but in retrospect I probably did it because I was scared or lazy or both. (See: squandering opportunities.) Odds are if I hear the "beep-beep-beep" of the money truck backing down the street I'd run right downstairs and guide them safely to my front door.

Hey, I'm not mad at Henry Rollins for doing Infinity voiceovers or whatever he does. Meanwhile there are people who would probably burn all their Dischord records if they saw Ian MacKaye drinking a kombucha or something, so it's all relative.

I guess what I'm saying is fifteen hundred bucks buys this whole blog, cash and carry. Just drop me an email.

from Bike Snob NYC http://bit.ly/2DFk4mo

0 notes

Text

More newspapers are changing the way they cover crime. That’s a good thing.

Back in October, Cleveland.com instituted a new “right to be forgotten” policy for its crime coverage. The local news outlet announced it would begin reviewing individual requests to have names removed from old crime stories. The idea behind the change, the newsroom said, was “that people should not have to spend their lifetimes answering for mistakes they made or minor crimes they committed many years earlier.”

They also stopped publishing mugshots and, with some exceptions, names of people who committed misdemeanors or other low-level crimes.

These types of editorial choices are still rare, but several outlets across the country like the New Haven Independent have similar policies around mugshots and names of perpetrators.

Last week, the Mississippi Sun Herald became the latest newsroom to make such a change. The paper announced it would be removing its mugshot gallery and would think twice about reporting crime “clickbait” — stories about low-level thefts, drunk and disorderlies, and other types of crimes that are so easily sensationalized and so rarely in the public interest. “For years, we posted the pictures of people charged with felony crimes, and, again, it was a popular part of our website,” the Herald’s editor explained. “But the mugshot stayed a part of people’s lives forever, whether they were convicted or not.”

More media outlets should follow suit. So often, crime coverage is guilty of so many of the same issues inherent in the criminal justice system. Changing the way we report on crimes is one way to change the way we deal with crime as a whole.

Getting rid of mugshots, covering fewer low-level crimes, and removing people’s names from certain stories are all steps in the right direction. But there’s more I think news outlets can do to fundamentally change the way we write about crime. Here are a few:

1. Source outside of the criminal justice system. As others have noted, local crime reporting “skews heavily toward the narratives of police and prosecutors.” There’s a myth that law enforcement are a neutral party, but by relying on them, we are promoting a law enforcement narrative, a huge bias in and of itself. It also leaves out other important community voices, like faith leaders, academics, community residents, and of course victims.

2. Report solutions. Crime reporting, particularly reporting on group violence and other community conflicts, so often frames these types of crimes as unavoidable or motivated by individual bad actors. In fact, there are many ways we can build stronger, safer communities, such as through community-based violence intervention programs and increased social services. Imagine if every crime story included information about these types of “solutions” to community violence and educated people on how to build stronger, more resilient communities.

3. Report on everyday violence as a public health crisis. Group violence, domestic violence, and suicide are rarely covered, especially by mainstream media. As the New York Times’ Andrea Kannapell writes, “It was something about them being too common, too obvious, no deeper meaning.” Although more reputable papers are increasing coverage of these commonplace crimes (like this recent feature from The Washington Post), there’s still a collective deprioritization. In the case of domestic violence and suicide, there’s a sense that these are private matters, not public health crises. And our racial biases allow us to deprioritize group violence and other “urban” crimes, which kill so many black people every day. As German Lopez writes in Vox, “Americans more likely to perceive black people as less innocent and even as criminals, which may, in some people’s minds, make these victims more deserving of the gun violence in their communities.”

Reading the Criminal Justice Beat

BAIL REFORM: A 61-year-old grandmother died in jail. Thirty bucks could have freed her. Janice Dotson-Stephens died earlier this month in a Texas jail, where she has been held since July for a misdemeanor trespassing charge. She had been given a $500 bond from a judge, which means she could have been released for about $30. It was her first arrest.

VOTING RIGHTS: Voter restoration means next to nothing without voter education. When Floridians passed Amendment 4 this November, they restored the right to vote to 1.4 million formerly-incarcerated people. But without proactive steps from the state, that likely won’t translate into votes. In this op-ed from Alabama, where voting rights were restored in 2017, organizers warn that the state’s complete lack of voter education has left many newly-enfranchised people in the dark about their rights. Back in November, I wrote about the lack of voter education for justice-involved New Yorkers. Out of the tens of thousands of people granted voting pardons by Cuomo, only an estimated 1,000 had registered by early October. Advocates say small number points to “miseducation and misinformation” originating from the state itself.

JAIL EXPANSION: “We’ll fight again. This is our community.” A decade ago, community organizers in the Bronx successfully defeated a plan to build a new jail in Hunts Point. Many of them are bringing the same tactics to the #NoNewJails movement. But it seems the city has learned some lessons from its past defeats as well. Organizers say the city planning is much more sophisticated this time around and will likely be tougher to beat.

JAIL EXPANSION: The Lippman Commission weighs in. In its latest report, the commission pushing for the closure of Rikers Island recommends that the city reduce the capacity of the new jails from 6,040 beds to 5,500 and to build a fifth facility on Staten Island. The commission also calls on city officials to do a better job listening to community concerns. But it dismisses critiques that argue Rikers should be closed without jail expansion. “The City’s proposal for four borough facilities is a necessary step towards closing Rikers,” it reads.

ELSEWHERE: A “betterment program” in Florida prisons, brought to you by the Church of Scientology. Criminon, a new program being offered in at least one Florida correctional facility, relies on the teachings of Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard and is being bankrolled by the controversial church. A spokesperson for the Florida DOC says that “theories of mind control would not be approved” in a prison-based program.

Inspiration

The first nationwide eviction database. The nationwide eviction crisis is a sister to mass incarceration.“Many of our poor, young black men are being locked up, and many of our poor, black women are being locked out,” says sociologist Matthew Desmond, who contributed to the Eviction Lab, a new project from Princeton University. Researchers collected evictions data from 48 states and D.C. and published it on an interactive map, the first of its kind.

A survey of women in prison. In partnership with Chicago Books to Women in Prison, The Point magazine mailed short surveys to incarcerated women across the country. Their crowdsourced responses paint a picture of what life is like for women behind bars. This is the type of project I’d love to do locally, particularly exploring women’s pathways into the justice system.

What I’m Researching

Do you have experience or expertise that could help me answer these questions? Please reach out at beatrixlockwood [at] gmail.com.

Who is on these secretive Neighborhood Advisory Councils weighing in on the jail expansion plan?

What are the unique pathways that land women in jail?

What is the racial and gender breakdown of who pays bail in NYC?

0 notes

Text

Book Review: The Alienist by Caleb Carr

The Alienist (Dr. Laszlo Kreizler #1) by Caleb Carr

Genre: Adult Fiction (Historical Fiction/Mystery) Date Published: October 24, 2006 (first published December 15th 1994) Publisher: Random House

When The Alienist was first published in 1994, it was a major phenomenon, spending six months on the New York Times bestseller list, receiving critical acclaim, and selling millions of copies. This modern classic continues to be a touchstone of historical suspense fiction for readers everywhere.

The year is 1896. The city is New York. Newspaper reporter John Schuyler Moore is summoned by his friend Dr. Laszlo Kreizler—a psychologist, or “alienist”—to view the horribly mutilated body of an adolescent boy abandoned on the unfinished Williamsburg Bridge. From there the two embark on a revolutionary effort in criminology: creating a psychological profile of the perpetrator based on the details of his crimes. Their dangerous quest takes them into the tortured past and twisted mind of a murderer who will kill again before their hunt is over.

Fast-paced and riveting, infused with historical detail, The Alienist conjures up Gilded Age New York, with its tenements and mansions, corrupt cops and flamboyant gangsters, shining opera houses and seamy gin mills. It is an age in which questioning society’s belief that all killers are born, not made, could have unexpected and fatal consequences.

The Alienist is the first book in the Dr. Laszlo Kreizler series by Caleb Carr. I really wanted to read this book before the series started, but too many books, too little time. You now how it goes. Still, I've only seen the first episode, so it all worked out. The premise and the setting made the story very intriguing. Unfortunately, the rest fell pretty flat for me. I'd heard such good things, so I was disappointed when I didn't love it.

It was devoid of emotion... almost like a textbook at times, but with conversations. I would expect that lack of emotion if it had been told from the point of view of the killer, but it wasn't. When it came to the murders, the writing was descriptive and clinical rather than graphic, again, like a textbook. Which is okay. We don't need graphic. And I get it. The story was geared toward the intellect, but the state of the bodies, plus the victims being children, and death is never pretty to begin with. All those things bring out emotions regardless, so the lack of emotion within the story made it all feel very detached and unnatural.

I never felt like I got to know the characters either. I know the basics about them, but we never really get to know them. What I do know of them, wasn't always believable for their time period, and because of these things, I wasn't drawn in or invested in their story. Also, it was a bit predictable. I loved the setting though. It really felt like I'd imagine the late 1800's in New York City to feel like. Sometimes, it didn't feel too different than NYC today.

You may like it though. What do I know? Most who've read it, loved it. So, give the book a try. It was certainly interesting at times!

Chapter 1 CHAPTER 1 January 8th, 1919 Theodore is in the ground. The words as I write them make as little sense as did the sight of his coffin descending into a patch of sandy soil near Sagamore Hill, the place he loved more than any other on earth. As I stood there this afternoon, in the cold January wind that blew off Long Island Sound, I thought to myself: Of course it’s a joke. Of course he’ll burst the lid open, blind us all with that ridiculous grin and split our ears with a high-pitched bark of laughter. Then he’ll exclaim that there’s work to do—“action to get!”—and we’ll all be martialed to the task of protecting some obscure species of newt from the ravages of a predatory industrial giant bent on planting a fetid factory on the little amphipian’s breeding ground. I was not alone in such fantasies; everyone at the funeral expected something of the kind, it was plain on their faces. All reports indicate that most of the country and much of the world feel the same way. The notion of Theodore Roosevelt being gone is that—unacceptable. In truth, he’d been fading for longer than anyone wanted to admit, really since his son Quentin was killed in the last days of the Great Butchery. Cecil Spring-Rice once droned, in his best British blend of affection and needling, that Roosevelt was throughout his life “about six”; and Herm Hagedorn noted that after Quentin was shot out of the sky in the summer of 1918 “the boy in Theodore died.” I dined with Laszlo Kreizler at Delmonico’s tonight, and mentioned Hagedorn’s comment to him. For the remaining two courses of my meal I was treated to a long, typically passionate explanation of why Quentin’s death was more than simply heartbreaking for Theodore: he had felt profound guilt, too, guilt at having so instilled his philosophy of “the strenuous life” in all his children that they often placed themselves deliberately in harm’s way, knowing it would delight their beloved father. Grief was almost unbearable to Theodore, I’d always known that; whenever he had to come to grips with the death of someone close, it seemed he might not survive the struggle. But it wasn’t until tonight, while listening to Kreizler, that I understood the extent to which moral uncertainty was also intolerable to the twenty-sixth president, who sometimes seemed to think himself Justice personified. Kreizler . . . He didn’t want to attend the funeral, though Edith Roosevelt would have liked him to. She has always been truly partial to the man she calls “the enigma,” the brilliant doctor whose studies of the human mind have disturbed so many people so profoundly over the last forty years. Kreizler wrote Edith a note explaining that he did not much like the idea of a world without Theodore, and, being as he’s now sixty-four and has spent his life staring ugly realities full in the face, he thinks he’ll just indulge himself and ignore the fact of his friend’s passing. Edith told me today that reading Kreizler’s note moved her to tears, because she realized that Theodore’s boundless affection and enthusiasm—which revolted so many cynics and was, I’m obliged to say in the interests of journalistic integrity, sometimes difficult even for friends to tolerate—had been strong enough to touch a man whose remove from most of human society seemed to almost everyone else unbridgeable. Some of the boys from the Times wanted me to come to a memorial dinner tonight, but a quiet evening with Kreizler seemed much the more appropriate thing. It wasn’t out of nostalgia for any shared boyhood in New York that we raised our glasses, because Laszlo and Theodore didn’t actually meet until Harvard. No, Kreizler and I were fixing our hearts on the spring of 1896—nearly a quarter-century ago!—and on a series of events that still seems too bizarre to have occurred even in this city. By the end of our dessert and Madeira (and how poignant to have a memorial meal in Delmonico’s, good old Del’s, now on its way out like the rest of us, but in those days the bustling scene of some of our most important encounters), the two of us were laughing and shaking our heads, amazed to this day that we were able to get through the ordeal with our skins; and still saddened, as I could see in Kreizler’s face and feel in my own chest, by the thought of those who didn’t. There’s no simple way to describe it. I could say that in retrospect it seems that all three of our lives, and those of many others, led inevitably and fatefully to that one experience; but then I’d be broaching the subject of psychological determinism and questioning man’s free will—reopening, in other words, the philosophical conundrum that wove irrepressibly in and out of the nightmarish proceedings, like the only hummable tune in a difficult opera. Or I could say that, during the course of those months, Roosevelt, Kreizler, and I, assisted by some of the best people I’ve ever known, set out on the trail of a murderous monster and ended up coming face-to-face with a frightened child; but that would be deliberately vague, too full of the “ambiguity” that seems to fascinate current novelists and which has kept me, lately, out of the bookstores and in the picture houses. No, there’s only one way to do it, and that’s to tell the whole thing, going back to that first grisly night and that first butchered body; back even further, in fact, to our days with Professor James at Harvard. Yes, to dredge it all up and put it finally before the public—that’s the way. The public may not like it; in fact, it’s been concern about public reaction that’s forced us to keep our secret for so many years. Even the majority of Theodore’s obituaries made no reference to the event. In listing his achievements as president of the Board of Commissioners of New York City’s Police Department from 1895 to 1897, only the Herald—which goes virtually unread these days—tacked on uncomfortably, “and of course, the solution to the ghastly murders of 1896, which so appalled the city.” Yet Theodore never claimed credit for that solution. True, he had been open-minded enough, despite his own qualms, to put the investigation in the hands of a man who could solve the puzzle. But privately he always acknowledged that man to be Kreizler. He could scarcely have done so publicly. Theodore knew that the American people were not ready to believe him, or even to hear the details of the assertion. I wonder if they are now. Kreizler doubts it. I told him I intended to write the story, and he gave me one of his sardonic chuckles and said that it would only frighten and repel people, nothing more. The country, he declared tonight, really hasn’t changed much since 1896, for all the work of people like Theodore, and Jake Riis and Lincoln Steffens, and the many other men and women of their ilk. We’re all still running, according to Kreizler—in our private moments we Americans are running just as fast and fearfully as we were then, running away from the darkness we know to lie behind so many apparently tranquil household doors, away from the nightmares that continue to be injected into children’s skulls by people whom Nature tells them they should love and trust, running ever faster and in ever greater numbers toward those potions, powders, priests, and philosophies that promise to obliterate such fears and nightmares, and ask in return only slavish devotion. Can he truly be right . . . ? But I wax ambiguous. To the beginning, then! CHAPTER 2 An ungodly pummeling on the door of my grandmother’s house at 19 Washington Square North brought first the maid and then my grandmother herself to the doorways of their bedrooms at two o’clock on the morning of March 3, 1896. I lay in bed in that no-longer-drunk yet not-quite-sober state which is usually softened by sleep, knowing that whoever was at the door probably had business with me rather than my grandmother. I burrowed into my linen-cased pillows, hoping that he’d just give up and go away. “Mrs. Moore!” I heard the maid call. “It’s a fearful racket—shall I answer it, then?” “You shall not,” my grandmother replied, in her well-clipped, stern voice. “Wake my grandson, Harriet. Doubtless he’s forgotten a gambling debt!” I then heard footsteps heading toward my room and decided I’d better get ready. Since the demise of my engagement to Miss Julia Pratt of Washington some two years earlier, I’d been staying with my grandmother, and during that time the old girl had become steadily more skeptical about the ways in which I spent my off-hours. I had repeatedly explained that, as a police reporter for The New York Times, I was required to visit many of the city’s seamier districts and houses and consort with some less than savory characters; but she remembered my youth too well to accept that admittedly strained story. My homecoming deportment on the average evening generally reinforced her suspicion that it was state of mind, not professional obligation, that drew me to the dance halls and gaming tables of the Tenderloin every night; and I realized, having caught the gambling remark just made to Harriet, that it was now crucial to project the image of a sober man with serious concerns. I shot into a black Chinese robe, forced my short hair down on my head, and opened the door loftily just as Harriet reached it. “Ah, Harriet,” I said calmly, one hand inside the robe. “No need for alarm. I was just reviewing some notes for a story, and found I needed some materials from the office. Doubtless that’s the boy with them now.” “John!” my grandmother blared as Harriet nodded in confusion. “Is that you?” “No, Grandmother,” I said, trotting down the thick Persian carpet on the stairs. “It’s Dr. Holmes.” Dr. H. H. Holmes was an unspeakably sadistic murderer and confidence man who was at that moment waiting to be hanged in Philadelphia. The possibility that he might escape before his appointment with the executioner and then journey to New York to do my grandmother in was, for some inexplicable reason, her greatest nightmare. I arrived at the door of her room and gave her a kiss on the cheek, which she accepted without a smile, though it pleased her. “Don’t be insolent, John. It’s your least attractive quality. And don’t think your handsome charms will make me any less irritated.” The pounding on the door started again, followed by a boy’s voice calling my name. My grandmother’s frown deepened. “Who in blazes is that and what in blazes does he want?” “I believe it’s a boy from the office,” I said, maintaining the lie but myself perturbed about the identity of the young man who was taking the front door to such stern task. “The office?” my grandmother said, not believing a word of it. “All right, then, answer it.” I went quickly but cautiously to the bottom of the staircase, where I realized that in fact I knew the voice that was calling for me but couldn’t identify it precisely. Nor was I reassured by the fact that it was a young voice—some of the most vicious thieves and killers I’d encountered in the New York of 1896 were mere striplings. “Mr. Moore!” The young man pleaded again, adding a few healthy kicks to his knocks. “I must talk to Mr. John Schuyler Moore!” I stood on the black and white marble floor of the vestibule. “Who’s there?” I said, one hand on the lock of the door. “It’s me, sir! Stevie, sir!” I breathed a slight sigh of relief and unlocked the heavy wooden portal. Outside, standing in the dim light of an overhead gas lamp—the only one in the house that my grandmother had refused to have replaced with an electric bulb—was Stevie Taggert, “the Stevepipe,” as he was known. In his first eleven years Stevie had risen to become the bane of fifteen police precincts; but he’d then been reformed by, and was now a driver and general errand boy for, the eminent physician and alienist, my good friend Dr. Laszlo Kreizler. Stevie leaned against one of the white columns outside the door and tried to catch his breath—something had clearly terrified the lad. “Stevie!” I said, seeing that his long sheet of straight brown hair was matted with sweat. “What’s happened?” Looking beyond him I saw Kreizler’s small Canadian calash. The cover of the black carriage was folded down, and the rig was drawn by a matching gelding called Frederick. The animal was, like Stevie, bathed in sweat, which steamed in the early March air. “Is Dr. Kreizler with you?” “The doctor says you’re to come with me!” Stevie answered in a rush, his breath back. “Right away!” “But where? It’s two in the morning—” “Right away!” He was obviously in no condition to explain, so I told him to wait while I put on some clothes. As I did so, my grandmother shouted through my bedroom door that whatever “that peculiar Dr. Kreizler” and I were up to at two in the morning she was sure it was not respectable. Ignoring her as best I could, I got back outside, pulling my tweed coat close as I jumped into the carriage. I didn’t even have time to sit before Stevie lashed at Frederick with a long whip. Falling back into the dark maroon leather of the seat, I thought to upbraid the boy, but again the look of fear in his face struck me. I braced myself as the carriage careened at a somewhat alarming pace over the cobblestones of Washington Square. The shaking and jostling eased only marginally as we turned onto the long, wide slabs of Russ pavement on Broadway. We were heading downtown, downtown and east, into that quarter of Manhattan where Laszlo Kreizler plied his trade and where life became, the further one progressed into the area, ever cheaper and more sordid: the Lower East Side.

youtube