#obviously in experimental metaphysics

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

as i mentioned in the tags on the second post, pneumatons are composed of elementary particles called sophons, which are like bosons if they had feelings. sophons are the class of particle that obey Descartes-Chalmers statistics and have quantum numbers associated with various qualia.

i should elaborate: you remember how in the bohr model of the atom where electron shells can only exist where a whole number of electron wavelengths fit into an orbit (because otherwise destructive interference occurs)? it's a situation kind of analogous to that. pneumatons in their ground state have a wavelength of about 1 micron and so can't exist in smaller organisms. they can have a shorter wavelength if they have a higher energy, but then they can decay into other bound sophon states, like psions, animons, cognitons, or even pure inspirons (high-energy, low-mass particles a bit like neutrinos, that preferentially only interact with brains when they're bored and don't have a bit of paper handy to actually write stuff down on). otherwise their mass is too low to really decay into anything else, which is what allows pneumatons to be stable inside protein-based tissue.

long range structure of souls is built up by the exchange of psychons, the force-carrying particle of telepathy, prophecy, daydreams, and weird higher math that doesn't correspond to anything useful. in the late 19th and early 20th century it was hoped that the psychon could give us direct access to the realm of platonic forms, until Saussure's experiments in applied semiotics killed platonism dead in 1903. efforts to unify fundamental metaphysics moved on to antisymmetric Deleuze-Guattari theory in the 1960s.

nonetheless little progress has been made since. despite spending billions smashing phone psychics and mathematics grad students together in huge particle accelerators, no differenceons have been detected, and post-structuralists' predictions that sophons are fundamentally unstable have not been born out. experimental metaphysicians keep asking for more money and theoretical metaphysicians keep trying to come up with new ways of unifying the soul, consciousness, and religious experience, but frankly the field is in kind of a rut. even the most optimistic predictions suggest that we'd need a couple of religious kooks on the order of John Murray Spear to probe the lowest grand unification energies, and the world just doesn't seem capable of producing people with that kind of frenetic vision anymore. the best we can do is occasionally kidnapping Claude Vorilhon and bombarding him with x rays, and while that's good for like an undergrad demonstration of sophon tracks in a cloud chamber, we're not gonna get new metaphysics out of it.

Bacteria do have souls, but binary fission doesn’t produce new souls 99% of the time, so most single celled organisms share these sprawling souls that just get bigger every time they divide. Over time they compact down into these big mats of soul get compacted into geological layers that gradually accrete to the world soul. Sexual reproduction creates new souls but they’re much shorter lived as a result, and rarely make it into the bedrock, so most of the world spirit is from the Proterozoic.

33K notes

·

View notes

Text

Aziraphale’s secret investigation and overlooked Clues

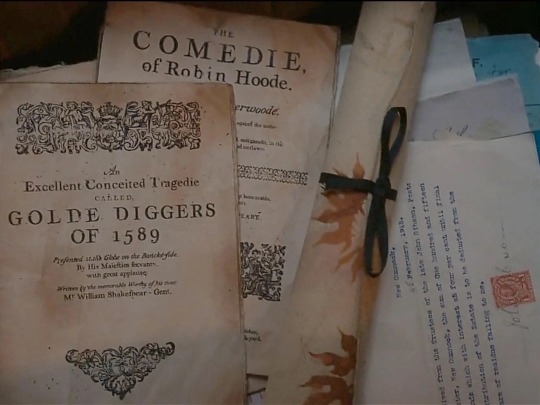

Remember this frame from Good Omens S02E06? Apparently Aziraphale had been using the empty carton box brought by Jim to store things in. It became a new home to at least two out of three “Lost Quartos” — the supposedly lost Shakespeare plays briefly but hilariously mentioned in the Good Omens book — as well as a very mysterious legal document.

Thought probably half of the Good Omens analysts here, including the ever so wonderful @fuckyeahgoodomens, who managed to find some information about the deceased John Gibson from New Cumnock (1855 - 1905).

Unfortunately the most interesting thing about this early 20th century provincial postmaster was his youngest child James (1894 - 1973), a quite famous stage (West End!) and film actor immortalized on screen in The Master of Ballantrae (1962), Witch Wood (1964) and Kidnapped (1963).

After that particular discovery the fandom-wide search seemingly led nowhere and the topic died a premature death.

And I almost figured it out seven months ago.

“But Yuri, you’re so clever. How can somebody as clever as you be so stupid?”, you probably want to shout across a busy London street at this point. Well, let me tell you. Much like Aziraphale, I'm blindingly intelligent for about thirty seconds a day. I do not get to choose which seconds and they are not consecutive.

Only tonight the stars have aligned in an ineffable way.

For those of you who don’t follow this account, some time ago I’ve realized that John Gibson isn’t the only testator whose estate was being investigated by Aziraphale right before The Whickber Street Traders and Shopkeepers Association monthly meeting.

If you watch S2 finale closely enough, you should notice that Crowley not only stress cleans Aziraphale’s bookshop — he also goes through the books and papers on his desk between the last three angels leaving the bookshop and Maggie and Nina’s intervention. A seemingly permanent arrangement of the props post-shooting, visible in detail both on Radio Times tour and SFX magazine photo shoot, sheds even more light on this detail.

The close-ups published after S2 release are legible enough to refer us to a much more prominent historical figure, Josiah Wedgwood (1730 – 1795) — an English potter, entrepreneur and abolitionist. Founding the Wedgwood company in 1759, he developed improved pottery bodies by systematic experimentation, and was the leader in the industrialisation of the manufacture of European pottery.

Long story short, I transcribed the handwritten pages abandoned on Aziraphale’s desk, found out the source and the full text of what could be identified as Wedgwood’s last will and testament, took a walk to visit his Soho workshop, and proceeded to write a lengthy meta analysis about it.

I was today’s years old when I realized that there’s something else connecting those two dead British men.

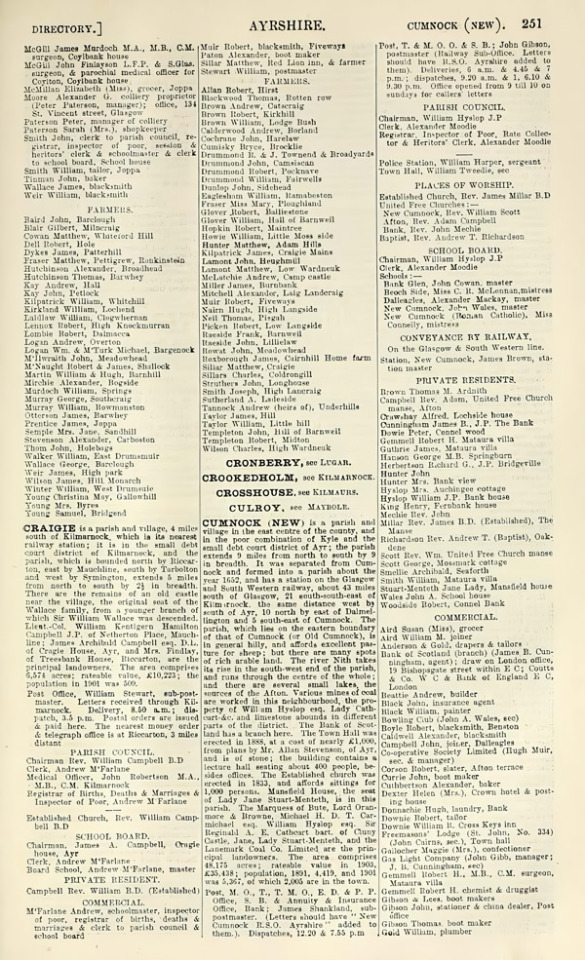

The Scottish Post Office Directory of 1903 recorded John Gibson from New Cumnock as a “stationer and china dealer” (above) operating from the shop located in the town’s post office building.

Indeed, a close look at his post office shop window in the Henderson Building (below, bottom left) reveals an artful display of fine china and pottery next to postcards printed by Gibson.

There are multiple ways to connect this surprising link with possible S3 plot points, obviously, but it’s getting late, so let’s just name the two most important ones.

You’ve probably heard of the Holy Grail, maybe from Monty Python or Good Omens S01E03 1941 flashback. Depending on the version of the story, if can be a cup, a chalice, a bowl, or a saucer — but almost always a dish or a vessel connected personally, physically and metaphysically to Jesus (unless you’re partial to Wolfram von Eschenbach’s idea that the Grail was a stone, the sanctuary of the neutral angels who took neither side during Lucifer's rebellion).

A slightly more obscure dish related to the Son of God appears in the sixteenth chapter of the Book of Revelation as a vital part of His Second Coming. The Seven Bowls (or cups, or vials) of God’s Wrath are supposed to be poured out on the wicked and the followers of the Antichrist by seven angels:

Then I heard a loud voice from the temple telling the seven angels, “Go and pour out on the earth the seven bowls of the wrath of God.” So the first angel went and poured out his bowl on the earth, and harmful and painful sores came upon the people who bore the mark of the beast and worshiped its image.

The second angel poured out his bowl into the sea, and it became like the blood of a corpse, and every living thing died that was in the sea.

The third angel poured out his bowl into the rivers and the springs of water, and they became blood. And I heard the angel in charge of the waters say, “Just are you, O Holy One, who is and who was, for you brought these judgments. For they have shed the blood of saints and prophets, and you have given them blood to drink. It is what they deserve!” And I heard the altar saying, “Yes, Lord God the Almighty, true and just are your judgments!”

The fourth angel poured out his bowl on the sun, and it was allowed to scorch people with fire. They were scorched by the fierce heat, and they cursed the name of God who had power over these plagues. They did not repent and give him glory.

The fifth angel poured out his bowl on the throne of the beast, and its kingdom was plunged into darkness. People gnawed their tongues in anguish and cursed the God of heaven for their pain and sores. They did not repent of their deeds.

The sixth angel poured out his bowl on the great river Euphrates, and its water was dried up, to prepare the way for the kings from the east. And I saw, coming out of the mouth of the dragon and out of the mouth of the beast and out of the mouth of the false prophet, three unclean spirits like frogs. For they are demonic spirits, performing signs, who go abroad to the kings of the whole world, to assemble them for battle on the great day of God the Almighty. (“Behold, I am coming like a thief! Blessed is the one who stays awake, keeping his garments on, that he may not go about naked and be seen exposed!”) And they assembled them at the place that in Hebrew is called Armageddon.

The seventh angel poured out his bowl into the air, and a loud voice came out of the temple, from the throne, saying, “It is done!” And there were flashes of lightning, rumblings, peals of thunder, and a great earthquake such as there had never been since man was on the earth, so great was that earthquake. The great city was split into three parts, and the cities of the nations fell, and God remembered Babylon the great, to make her drain the cup of the wine of the fury of his wrath. And every island fled away, and no mountains were to be found. And great hailstones, about one hundred pounds each, fell from heaven on people; and they cursed God for the plague of the hail, because the plague was so severe.

#good omens#good omens meta#good omens analysis#aziraphale#aziraphale’s bookshop#set design#good omens props#the good omens crew is unhinged#john gibson#josiah wedgwood#fine china#pottery#holy grail#seven bowls#second coming#yuri is doing her thing

93 notes

·

View notes

Note

i'm pretty sure helena and delorean would have been very good friends too – obviously if delorean had a stronger material presence on our existential plane.

helena came into doc's life when she was around 8 years old. i'm not going into too much detail about what was going on with the brown family in this timeline/au (perhaps i'm gonna do it in another ask) but to summarize: helena's father, leonard, gave doc legal custody of his daughter because he was leaving the country for a few years. and the only trusted person available for taking care of helena was doc.

so, from that moment on, she has been living with him.

and she had the privilege to see how her uncle worked and finished building the time machine.

at the time, doc still didn't have much of an idea about how to properly deal with children, but he did the best he could. let's say it was all experimentation and improvisation. but if there was one thing that he did constantly, it was letting his niece participate in the assembly and construction of his various inventions. including the time machine. well idk if saying that is a little bit of an exaggeration, but he did let her help him with some little things.

at first he just did the typical thing of having her hold a flashlight for him when fixing some stuff, but once she grew up, he let her help him in a more serious way, even letting her assemble some things on her own. i feel like all that might have made delorean develop some sort of appreciation, even if minimal, for helena. (and well, when they later get stuck in the old west, her appreciation towards her increases even more eehehehe)

like the rest, helena doesn't know that the machine her uncle invented has a consciousness of its own, but i can assure you that if she knew about the existence of delorean, she would immediately want to become her friend. after all, helena is naturally a very outgoing girl and has no problem talking with literally anyone. and anything.

(side note: helena was born on july 4th, 1968. the same year as marty, but one month later, eeheheh. oh, and she is also interested in esotericism and metaphysics, it's just that they haven't become her top priority yet-)

As I said, they absolutely would

DeLorean is, under all the bravado and coolness and aloofness, a very lonely car, and very attached to one Emmett Lathrop Brown and everything HE’S attached to. Of course she would be clingy as a dog to all his relatives

She IS clingy to Clara, Jules and Verne, even if we’re considering strictly the movie canon. If she could she’d be constantly asking for headpats (roofpats? “This bad girl can fit so much time circuits inside” stuff? Idk)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

and here it is.

arranged on Website as neatly as I could manage-- and, believe me, I got it looking neat.

this composition is unfinished just like the rest, but this time it's not on purpose. this one will be finished one day. it is an ongoing narrative, a good old-fashioned fictional Blog.

the writing style was selected in order to challenge myself, to push myself to be even clearer and even more lucid than ever before. this is inspired by Samuel Beckett's Molloy, a book that was a headache to read but felt inexplicably rewarding. you don't have to know Molloy to read composition no. 8, though. just, I suppose this is the closest I can really come to writing from a genuine "folksy" place. this is my folk. this is DJay Folk. immensely personal, local. this is the logical conclusion of the trajectory of the composition no. series.

the actual content was also selected in order to challenge myself. I want to mythologize the Weed Years, much as I would use Jordan Eats and Rapture to mythologize my early teenage years. the challenge here isn't necessarily in being honest and open about things, nor in dramatizing real events, but rather in putting words to processes that paralyzed me.

there's a much easier way to look at this, as this complicated set of requirements basically comes right around to describe a far more recognizable process:

this is poetry. old-fashioned, Symbolic-Surrealist, Metaphysical, every damn book I've taken interest in as an adult, poetry. I'm digging into my memories of the Weed Years and breaking it down into fundamental symbols and ideas. then I'm processing the interactions and crystallizing a genuine poetic point out of it.

the story itself openly acknowledges how and why this is so difficult.

I started writing this in 2021. I wrote a whole section of the story in 2023, then I only wrote one chapter of section 2 in 2024. in the past few days I have opened some notebooks and done some more rigorous preparation for what's to come.

hell, in all this time, we haven't even fucking made it to the Dolls yet. they keep getting brought up, it's obvious they will be a focus of the narrative. we kinda are coming close to them, though. I'm a little intimidated by the prospect, as I want the Dolls to capture a very specific undefined emotion. so I've gotta define that emotion first, then use the Dolls to make the reader feel it.

after the Dolls, there are some other upcoming structural elements I'm planning out at the moment. and eventually, the end of the story will involve the plot of my game Empty City, as I'd been meaning to fictionalize that one for a while. (it won't be a retelling of it, as Empty City is not about Jordan. but Jordan is a character in the game! and I want to explain what the fuck he's doing there.)

I do not know exactly how long this story will be. I would like it to be the length of a short novel, but I don't need to force that if the story doesn't call for it.

right, I guess I'll say some of the other kinds of things I say for all the other compositions.

so visually this blog feels more like an actual modern website. that's got to do with my decision to make the original blog using one of Blogger's newer dynamic styles, as Blogger will obviously try to use newer styles to capture a modern aesthetic. with this aesthetic, there is no image in the background, only a pleasant non-white color scheme.

I took the basic aesthetic of the original blog and simplified it further, removing the needless javascript and that confusing table of contents. the text is arranged neatly, as the priority here is the narrative experience, like a book. and even in the story so far, the text has drifted into "experimental" modes which offer a far more visual experience. I have been able to preserve those in the Website release.

there is also, rather front and center, a more obvious visual element. composition no. 8 will feature my art. I am actually drawing things for this story. so far we just have the "splash" image, foreshadowing the Dolls.

even just from this image alone, you can draw some conclusions and expectations for what the Dolls may end up being. the design of this Doll is based on the Rag Doll from composition no. 2. I knew I wanted to bring that dress back, I wanted to explore that Rag Doll idea.

I'll lay a couple more cards on the table here: I want composition no. 8 to be a scary story. I want the experience of reading it to be bizarre, considered, cerebral, and for it to feel like the reader has just kinda stumbled into horrors they haven't got the language for. maybe I just really want the composition no. blogs to have led to something substantial, something self-evidently worthy of being someone's favorite Internet Fiction. the same kinda thing I always want with my projects, but that's how I know this series is one of my projects: I'm getting optimistic about it!

and, like. what this story is so far is very dense prose getting at some very dense concepts through a short list of Symbols I find very aesthetically addictive.

the Dolls are one of those Symbols.

my self-insert is another.

EAT is another, and EAT does have a presence in this narrative, but it's indirect. EAT is the second-person this time. this story is being told to EAT.

and then there's the Eternal Mansions. they are related in some way to the Empty City. they may just be a geographical "feature" in the Empty City, I think that's a reasonable deduction. but if they are, they're the same Empty City that I made a game about, it's the Empty City as I myself see it. it's a land that doesn't really exist, and is just an allegory. but we must treat it as if it does, and feel around until we can identify some features this non-existent place actually has. it's a perfect place. it's not meant for humans.

composition no. 8 will continue. you can be sure of that. this is where it's currently at. I will update it on the Website and not the original blog. I mean, probably.

so this also means all eight installments of the series have been brought to the Website.

next up I need to make a unifying landing page for the series. that'll be much easier and will probably make use of these very rambles I've been putting on tumblr.

I'll see you when I see you. thanks for reading.

#my art#oh yeah. right. if you're wondering what 'material nostos' means.#nostos is homecoming. composition no. 8 is me telling the story of my coming home to the material world.#from a strenuous journey through symbolic abstractica.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

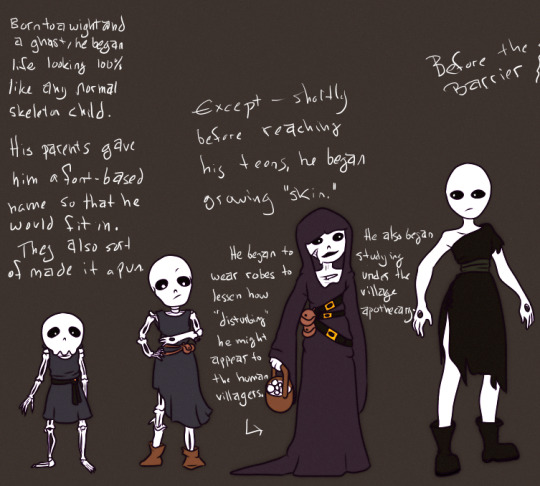

Decided to finally get around to doodling an illustrated guide to this malcontent's life and changes throughout 😪 feat. my chicken scratch that I'm too lazy to transcribe. Below the readmore are just some silly additions.

The pun, explained, though it's rather obvious: since he's partly a Ghast on his father's side - yeah I'm not going to bother spelling it out it's just like. Right there.

Wights in his world refer to "undead of mixed origin" - his mother's side had enough skeleton for him to look exactly like one until just before the monster equivalent of puberty kicked in.

The apothecary he used to study under was a human dude in the little mixed human-monster village he and his family lived in. The guy liked to joke that he was an honorary human because "he has a skeleton inside him, too :)" (Gaster stopped trying to point out that the 'skin' was growing from/into/dissolving/otherwise removing the 'skeletal' part of him after a while; old guy thought it was funny).

His parents were in charge of funerary ritual for both monsters and humans until the war and unrest reached their village. It began with a human priest deciding to set up shop and sow suspicion among the people living there.

The Royal Archivist was a fluffy old crow, looked kind of like the lovechild of a honchkrow and Pokiehl. They met during some ceremony or another, became good friends, and then had a falling out over something stupid.

He ceased incorporating feathers into his wardrobe because it was due to a couple of them getting sucked into an experimental machine that caused it to explode. This explosion had two significant results: 1. he ended up injured to a degree that he could not physically nor metaphysically nor mentally heal from, and 2. a lab tech he had been working with that day died. Until his jump he maintained (even if only to himself) that he should have been the one to die that day, since it had been his fault.

That incident led him on a downward spiral which, combined with a few other life events that occurred afterward (like submitting his fallen mother to the DT trials run by Alphys) and some external coaxing by what he assumed at the time to be a hallucinatory influence caused by his own guilt, led him to try killing himself via the CORE. He thought it would be poetic to die via his greatest achievement. Obviously it did not work out.

Editing to add a doodle of the Archivist,

Muses can encounter him similarly to the COREsprite (via visiting the world this blog's drippy guy originates from).

#Things that are headcanons but also canon to this blog's Mr. Grumpy Bitch#Insert Muse Tag Here#I can't remember if I have one#Other than like#NullAesthetics#But this isn't aesthetics now is it

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

canvas, wardrobe, & alternate for the oc ask game ?? any character(s) of your choice!! :3

omg hi!!! Ty

canvas: Does your OC have any scars, piercings, tattoos, or other markings? Do they display or cover them up at all?

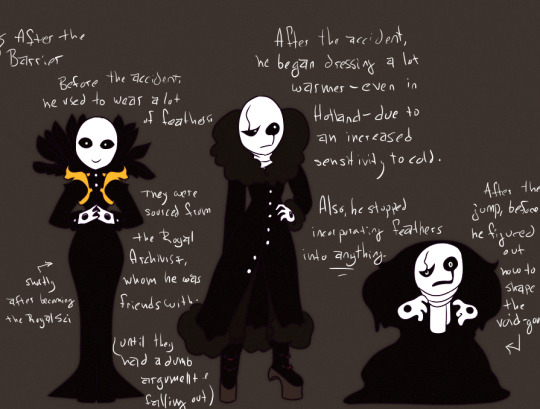

Du Vide, unless im misremembering, is my only oc with tattoos. They span his entire body, neck to toes, and he did them himself, sewing needle stick n' poke style. I doubt he'd have trusted any one else to ink them.

Since du vide is an upcoming ttrpg character and my fellow players follow me i wont go into detail regarding why he has them by he definitely has them for a reason, relating to his work in experimental machinery/technology. Any good mad scientist tests things on themselves first, obviously.

As for covered up or not, he doesn't make any real effort either way, due to the size of the tattoos. he's usually pretty covered, but he doesn't care if they get seen, theyre not secret. as for why they don't show up in the art usually is because i hate drawing them. weeps

wardrobe: How big is your character's wardrobe? Do they wear things threadbare, or can they afford new clothes often? Are they any good at mending and repairing their own clothing?

Courtland is a notable character wardrobe-wise because i designed him to be so unredrawable due to my madness

pictured: madness

Courtland's wardrobe is relatively large but most of his clothes look the same. The clothes he's wearing up there are his work uniform, so it's what he's usually wearing day to day with a few changes.

however he does have other clothes in line with what you'd expect from an aristocrat, like day clothes, outing clothes, outrageous party clothes, etc. Courtland's got *very* extravagant party clothes. he doesn't get the opportunity to wear them often and isn't very fond of them anyway.

as for when his clothes get fucked up, he's very good at repair. sewing and the like is one of his favorite hobbies!

here's him under all that fabric;

alternate: What would your OC's alternate universe look be? If they're a fantasy character, what's their modern look? If they're sci-fi, what's their fantasy look? What AU would you want to see your OC in, and how would they dress themself? Bonus: Prompt an AU!

when it comes to AUs, the one i end up landing on a lot for the earthshakers is the classic "what if it all never happened"/"what if they lived"

theres exactly one post on here (or the art blog i dont remember) explaining what the deal is with purgatory so heres a quick rundown: In the spaces between realities exists a vast, wild, metaphysical plane referred to occasionally as purgatory, which is a roiling melting pot that chews people up and spits them out as fantastic monsters. getting there is extremely difficult, but the hands down easiest way is to die, and fall through a weakness or crack in your reality when transitioning from life to afterlife.

Since the creatures in purgatory are always changing to suit their needs and there is no true ceiling for what can happen to you, occasionally a particularly strong-willed individual will grab unmatched, omnipotent power and become something called an earthshaker, the highest most feared echelon of purgatorian life. not gods, but damn well close. The earthshakers i've designed are Wellium (aka Lux, or the White Light), Videns, and Seleen.

(psa: this is a creative project? headworld? thing? ive been working on for literally upwards of 6-7 years now. I consider it my special interest, but its kind of nebulous and wordy and i get Too Excited about it so i end up rotating it around in my head a lot instead of talking about it)

Each of the three come from wildly different places/settings, and each has a grisly death, leading to their conquering of the endless voidplane. It's a fun thought to think about, about where they'd be if they just never died at all.

Wellium was once a soldier, a test tube baby/experimental weapon used in an intergalatic war. Eventually after a life of training to kill the unfamiliar, her life was considered inconsequential enough to be selected to guide and activate an experimental bomb to attempt to wipe out their enemy. Videns was a child born with select supernatural powers, and out of fear and superstition was drowned in a river by a mob of villagers after a life of living on the run. Seleen, a magician, was born with too much magic, and died when her body couldn't handle the strain anymore.

like. Videns could have found a place where she couldve flourished and been accepted. Seleen couldve pursued other paths in life instead of obsessing over her own impeding death and the use of the very thing that doomed her. Wellium couldve gone home.

their deaths are tragic, but theyre what set them on the path to kinghood and make them the creatures they are now. however, due to the way their universes work, there are realities where they did live, and lived full lives. got the chances to become people. its fun to think about!

what is and what was.

again ty soooo much for the ask! sorry that this post is dashboard destroying lol

#purgatory setting#lux / wellium#du vide#courtland#ask game#long post#videns futura#seleen moramor#holy fuck a reason to talk about earthshakers#i am. so emo. about them#if you count it a lot of the stuff i draw about them being silly and the like is an AU bc#a lot of the ''canon'' stuff is just brutal!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

BigSPEEGS Movie Reviews, Interview with Ben Coccio, Director/Writer of "Zero Day", N.D

According to his production company's website (Professor Bright Films-- http://www.professorbright.com), Ben Coccio has been making short films since he was twelve years old. He has directed several short films with Dave Shuff at Professor Bright Films, including commercials and shorts for MTV and IBN, and the cult classic 5:45 AM, which has aired on the Independent Film Channel (IFC). This September, I was lucky to see one of the first screenings of his brilliant first feature film, Zero Day,, at the Boston Film Festival. Zero Day is a film about two high school students who plan a school shooting, and is filmed in an experimental, "Blair Witch"-esque way, as if the film were the video diary of the two main characters. Since the Boston Film Festival, the film has gone on to win awards from many film festivals across the country, including "Best Feature" awards at the New Haven and Empire State film festivals. Recently, I had the privilege of being able to talk with him about his remarkable debut feature.

Evan Spigelman: Describe "Zero Day" for someone who has never seen it.

Ben Coccio: I guess I would describe it, in all honesty, as a movie about a school shooting. I would also say, if you're going to put it in a genre or something like that, I think it would be a thriller or maybe a suspenseful movie, but it's also... this may sound kind of perverse, but it's also kind of a buddy film. I think half the reason people who like the movie, who enjoy watching it (if you want to use the word "enjoy"), is because their relationship as friends is compelling, and I think, realistic. I think there are times when it's just enjoyable to watch them together.

ES: What inspired you to make a film about a school shooting?

BC: I think Columbine is clearly the factual inspiration. It's also a metaphysical inspiration too, but this isn't a movie about Columbine. There are obviously a lot of similarities, but Columbine was Columbine, and this is a movie (laughs). I just remember thinking that this was the ultimate event for describing a lot of things that people may feel in high school. I don't know if that makes any sense, but the idea that it seems like what happened to me was (and I'm not exactly proud of this thought), but I was surprised it hadn't happened sooner. That made me think, "Why did I think that?"; it was just a fascinating event. Being clinical about it, the fact that it was also a terrible event, but it was also fascinating; the thought of these two people committing to doing something like this and then actually following through on it. I found it rather compelling dramatically and I was trying to think I mean, I don't have any connections, I don't have anyone in the industry who's going to help me get a lot of attention, but if I'm going to try and make a feature and get it out on the festival circuit, I should probably gamble on something that at the very least can get attention to begin with. You know, you can either have a big star in your movie or make the subject matter the star to some degree, depending on when you do it, so all those things sort of culminated in deciding to do this.

ES: How did you start to develop your idea into what we see onscreen?

BC: That's a good question. I did a lot of research. The funny thing is, everyone does some research when doing a work of fiction based on something that they think is in some way realistic, but at the same time, I felt like I shouldn't do research because I wanted it to be my own thing. I think the main reason I did the research was to confirm what I thought about these characters and what I thought about this arc of their story, to see if real events kind of confirmed that to some degree. And of course, when doing research I got a lot of ideas I didn't have before, so that was the first step, and then while I was writing I was casting; I was trying to get types of actors and whatnot; then I just jumped into it.

ES: How were some of the more improvisational bits in the film handled?

BC: The cool thing about that was, for instance: there's a scene towards the end of the movie where they break into Andre's Cousin's house and steal guns from it. Basically what we did was we set up everything in the house as we wanted it and I told them exactly what they had to do and what they should stress and what they should hit, and said "Alright guys, do it," and just followed along as they did it. So there are a lot of scenes in the film where they would actually just do what they were supposed to do. It was unpredictable and fun, and we would get what we wanted but we would also get really excited and really nervous; you really felt like you were breaking into their house! There was a lot of stuff like that that was just unique in a moviemaking experience. We had a lot of control, but we also left a lot to chance, I think in a good way.

ES: How did you ever find a school that would let you film that last scene?

BC: (Laughs) I never did. I basically asked all the schools that I got in touch with in Connecticut and nobody wanted to touch it. Every superintendent in every school basically explained to me that if they ever let anything like that be filmed in their school they'd be fired. So I went with a college, actually. The State University of New York, which is about an hour north of New York City. It's this very strange-looking place that looks actually a lot like a high school and they didn't really care about the subject matter because it's a college, so that didn't faze them too much; they were more concerned about the technical aspects: you know, would there be any danger to their equipment, would anything get broken, would anybody get hurt, and that kind of stuff. I had insurance, so it just came down to that and convincing them that we were going to be professional and nothing bad would happen to their facility. No high school in their right mind would ever (laughs) unless it was like Quentin Tarantino or Steven Spielberg or something, it would be very difficult to convince a high school to allow that to be filmed in it.

ES: Why did you decide to have Cal and Andre use their real names and have their real parents be actors in the film?

BC: I wanted to use their real parents; I didn't necessarily think it would work out, and if it did work out I didn't think it would work so well, but I wanted to use as many non-actors as possible in all ways and in all scenes. As many as possible; just fill it with non-actors and make it seem as real as I possibly could. That was the thing that I was striving for all the time, to make it feel real to the viewer. And it's a challenge because when you go into a movie theater and you watch a movie, it's very hard to pull one over on an audience anymore, and I mean, I think I came close. You know, there are scenes when I cringe, but using their real names and their real families was just a device, just like having them actually break into the house. It was a delight to get them into it and to get their family into it, and to get everybody around them into it. Nobody had to remember some fake name or anything like that, and it was actually very easy for them to be natural around each other because the only "wall" up was this camera, which was, for all intents and purposes, it looked like the kind of camera you'd have for home footage. So, I did everything I could to keep it real, and I think using non-actors and using the real families was sort of an essential part of it. It would've been OK if I wouldn't have been able to do that, but I really wanted to do it.

ES: Again, for someone who hasn't seen the film, why would Cal and Andre film all of this?

BC: That's a great question. To me, I know this is a polarizing and hard-to-ignore subject matter, and whenever someone talks about the film (like critics or someone), the first thing they always talk about is the subject matter, and of course, they're going to. Well, unfortunately, I think sometimes this makes some people miss out on the fact that it's a movie! And I'm trying to do a lot of things with the structure of a movie, and calling to question and playing with scenes in movies that I think we all sort of take for granted. I think first of all that Andre and Cal use the camera as an audience. To them, the most important thing is to not let on to anyone that they're planning to do this awful thing, but they've got to have an outlet; they've got to tell somebody, they've got to brag, and the camera is someone to brag to. But the funny thing is, is how when they're directing the camera, Andre and Cal's characters will switch back and forth between conspiratory, where they're talking to the camera and you're along for the ride, and "We're letting you in on this secret," and adversarial, as if the people on the other side of the camera are the target. Like, there will be times when Andre will be teaching you how to put together a gun or a bomb or something and you'll be his friend, you'll be his confidant, you'll be someone who's going through a similar thing. Then there'll be times when he'll say, "I'm going to come and get you; it will only take me 45 seconds to find you; we're going to leave you all behind." Then, he's talking to you as if you're his target. So I think the reason that Andre and Cal are doing this (as characters) is that it's a way to record and document what they're doing for posterity and to brag to someone and let someone know what they're doing without letting anyone know what they're doing. I think the nice thing that works within the movie is that it creates this kind of tension where you as the audience end up being both along for the ride and a target of the eventual assault, and I like that tension.

ES: Do you think there's a leader between Cal and Andre?

BC: I think that's one of those things that I purposely engineered to be unanswerable, and I think if anything I would love people to come out of the movie and go to a diner and have a debate about which one they think is the leader. Because I think that there's evidence to say that either one is in control, and there's evidence to say that they're equal. I think we definitely set up the character arc in such a way so that in the beginning Andre really appears to be the one in control; he's the one who seems to be setting the tone. But by the poetry reading scene (I don't know if you remember that scene where they go to this poetry reading, and at the end, Cal is telling Andre to drive with his eyes closed), you start to realize that Cal has a lot of power in this relationship as well. I think you can definitely look at the character arcs, and they're intertwining along the way; they're going in and out and really intertwined in a nice way... I would never say to anyone, "No, you're wrong" if someone said "Oh, I think Andre's the leader"; I wouldn't refuse it, but I think it's one of those things where I purposefully engineered it to be vague.

ES: As you see it, do you think that either Cal or Andre had ever thought of doing such a thing before they had met each other; do you think they would've had even the slightest idea that they could have pulled such a thing off if they never met?

BC: I think if you're ever looking for an easy reason as to why Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris did what they did in Columbine, it's because they met each other. I think when two people do something like that; they probably would have never done anything of that magnitude by themselves. I do think that beforehand they might think about doing something like that, definitely, or similar thoughts might get entertained, but I think it's this sort of meeting of the minds that starts these things up, and I think they (maybe even unconsciously) egg each other on, and they get farther and farther along. But I think if you're looking for a simple reason as to why someone would do something like that (if there are two of them) it's because they met each other and they just buttress each other.

ES: I thought one of the most effective scenes in the film was when they take all of their stuff and just burn it, and obviously that must reflect your opinion on the influence of outside media on someone doing something like this. Do you think that movies, TV, video games, etc., have any role to play in a situation like this?

BC: The answer is no. I don't think movies or video games or television could ever incite anyone to do something that awful. Blaming it on that is just a simple way for someone to deal with it, simply put. I think there is a kind of culture of fear from the media, but I don't think that would incite anyone to do anything bad. I think if someone's going to do something bad, it's their own responsibility and it's their own decision.

ES: Do you think that by the end of the film, Cal and Andre got what they wanted; to "teach the world a lesson," and get people to wake up?

BC: I think in a very simple sense, they got what they wanted. But, like anything like that, they got more than they bargained for. I think their desire to give a "wake-up call" is not too remote from Napoleon or Hitler's desire to give a "wake-up call." These things definitely have an impact on society in some way or another, but it's a selfish, arrogant, ego-maniacal thing to say: "It's my responsibility to give society a wake-up call." That's what kids like that probably feel; they probably feel very superior, in a sense. I think one of the problems is that no one treats them the way they feel they are entitled to. They think they're better than everyone else, and no one treats them that way. Not that anyone necessarily torments them, but they just don't give them the treatment that they feel they're worth. So I think when someone says, "I'm going to send these guys a wake-up call," that's a sign right there that this person believes that they know better than everyone else, which doesn't usually work out so well. (Laughs)

ES: How do you think the film would be different if it was filmed in a perspective other than a video diary?

BC: Oh... that's a good question. A related question is; someone once asked me if I would've done anything different if I had a huge budget. No, I wouldn't have done anything different. I personally feel that you have to do this movie this way, in a sense. What I was trying to do was trying to get you really up close and personal with these characters, and I think the best way to do that is the video diary approach. It allows you to do a lot of things that you maybe could do with a 35-mm camera and a different perspective; a third-person perspective, but with the first-person perspective, technically, as a filmmaker and with acting you can get a lot of things really fresh and really honestly, but you also create a sort of urgency to it. It's just another device to really suspend disbelief.

ES: What has been the general reaction to the film so far?

BC: It's actually been remarkably good. I mean, considering the subject matter of the movie, it's been remarkable. Boston was the first place to play it. In Boston, they actually added two extra days to screen it, which was really cool. Then in New Haven, which was the next place that it played, a pretty small festival (only three or four days long), they usually only play each film once, but this was screened twice, and both sold out and ended up winning the Audience Choice Award, which was a shock to me. I didn't think that that kind of movie would win an award like that when the audience could've gone with one of the few good comedies at the same festival. The reviews have been good to really good so far. In Denver, it may get buried a bit, since "Bowling for Columbine" is there at the same time as well, and I just don't know how that community is going to react to that, so it should be interesting. It's actually had some interest from some smaller distribution companies so far, so we'll see.

ES: You mentioned "Bowling for Columbine", which deals more with the gun issue than the more psychological issues that you deal with. What role do you think access to guns plays in fueling a violent act like a school shooting?

BC: I didn't make this movie to make a statement about gun control at all. I think one of the worst things that have happened to American civilians on American soil, the worst event of mass violence happened (on September 11) because someone had a tool that was intended for something else and used it violently. I think philosophically, I know guns are designed to shoot living organisms, but still, there's almost no one in this country who buys a gun explicitly to kill somebody. So in that situation, too, you have people who take a tool and use it in a way that's not intended. That really comes down to a question of personal responsibility. Agreeing, if they didn't have guns, they'd have to do it with something else. But there's no guaranteeing that it wouldn't have been worse, actually. Because maybe they'll build a bomb, and bombs will kill more people than guns. I wouldn't really come down one way or the other on gun control, but if you get anything from this movie, you can sort of get this idea that gun or no gun, these guys were willing to do something like this.

ES: How would you respond to someone who would say that the film goes into too much detail as to how Cal and Andre do this; that you show too much of the specifics of their "operation"?

BC: That's an interesting question, and I think if someone were concerned that we go into too much detail as to how to build a bomb or something, I would say that again, the knowledge about how to do this is readily available in other places. In the movie, in the scene where, for instance, they show how to build a bomb, it's really more about them, and how they are and how they see the world; that's just what they're doing at the time. I would understand why someone would be concerned, but personally... Again, I think it comes down to personal responsibility. I don't think anybody watching this movie is going to think, "Oh yeah, let's go make a pipe bomb!" I don't think it's handled that way.

ES: So what's the next step for "Zero Day"? Do you think it has any hopes for distribution?

BC: I really honestly believe that this movie can have a respectable audience on the art-film circuit (you know those little art-house theaters). I think that seeing what makes the run of art-house theaters nowadays, I don't see why this couldn't make it. It would definitely cause a stir or a buzz and garner some interest, and I think it would attract an audience; I think they would respond to the movie well. My hope of hopes with this movie would be to get some kind of small-scale distribution like that. I think it's pretty clear that this movie could never go real big, it's just too difficult; I don't think it could play at a mall or attract huge audiences. I think it could definitely turn a profit and find an audience, and that would be sort of the best life it could have, I think.

ES: Thanks for your time; hopefully we'll be able to talk sometime about how the Denver Film Festival goes.

BC: Thank you very much.

0 notes

Text

Re: 3, I think the main reason the concept seems dubious is people like Searle or Chalmers who envisage things ("Chinese rooms", "p-Zombies") that talk about being conscious but aren't really. It's obviously a productive line of inquiry to try to figure out why people think they are conscious and what specific brain states that refers to, and you can do that using the normal framework of experimental science. But Searle &al think that's not the actual consciousness, which is rather some undetectable metaphysical thing elsewhere: that's what seems fishy.

This is also the reason for the claim in 2. If external behavior doesn't carry any information about whether "experience" is there or not, then there isn't really any argument you can make for why you have measured it, no matter what you measure.

Baffled by claims to the effect of "consciousness (in the sense of internal experience) doesn't matter/isn't real/might as well not be real because we can't measure it". True, we can't measure or detect it in an objective and repeatable way, as we'd very much like to be able to, but

That doesn't mean it's unobservable. I can observe it in myself. In fact I'm pretty sure I observe my own consciousness, very directly, every single waking moment. You'd be hard pressed to convince me it isn't there, about like how you'd be hard pressed to convince me my hands don't exist. It's right there!

Just because we can't measure internal experience objectively and repeatably right now doesn't mean we'll never be able to. Science abounds with things we couldn't measure until we could. Sure, maybe we'll just never be able to detect it in a way everybody can agree on... but maybe we will. It's a pretty strong claim to say with certainty that we won't.

This is probably the weakest objection of the three, but if consciousness is, you know, as good as bullshit... what is it that everyone keeps referring to when they talk about consciousness? And saying that they have? Uh like why, from the point of view that this consciousness stuff is Not Meaningful, does everyone keep going "I'm conscious"? Like what is the thing they are actually experiencing, if consciousness is a load of hooey?

I guess I just don't understand this position. It seems like denying what is plainly in front of your face. It seems, well, fiercely anti-empirical, to a degree even the big-daddy rationalist Descartes couldn't countenance.

To be super duper uncharitable, it sometimes seems to me like an ill-thought-through ingroup signal? Like "consciousness is a humanities thing, philosophy is a humanities thing, but I'm a Science Guy and we use measurement. Since I can't measure consciousness it is bullshit". And this ingroup signal leads one, as I said, to deny the basic empirical observation in front of them. Like, yeah, there is no objective and repeatable metric for pain either, but I think even the most hardcore Scientist would yowch and tell me to stop if I hit him with a big stick. I don't think he would say the concept of pain is meaningless because we can't (yet) quantify it objectively. And if he did claim that, I don't think he would live by it.

But, I don't know. Like I said, that is a massively uncharitable take. Maybe I'm misunderstanding the position. Or maybe I'm using the word "consciousness" differently. As I said, the thing I mean by this is internal experience, internality, the fact of there being some thing it feels like to be you.

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

Setting up my first solo RPG campaign!

I figure I might as well blog about my first real experimentation with solo RPGs, since I think some of y'all might be interested in it and it'll help me organize my thoughts. I'm just going to talk about my basic setup first, and I'll make some separate posts a little later down the line about the setting and the characters.

The tools I'll be using are the second edition of the Mythic GM Emulator and a cyberpunk adventure generator you can get on DriveThruRPG. I've printed out all of the relevant pages for reference, so I don't have to stick to my computer when I play!

For this little campaign, I'll be playing a custom PBTA hack I created about a year back. It does not actually have a name, but I'll be calling it Cybergnostics. It's a blend of cyberpunk and religious horror inspired by gnostic theology. The characters are downtrodden Heretics living in the slums of Arcadia beneath the watchful eye of the Church. It's got many of the typical trademarks of cyberpunk- cybernetics, gangs, heists, all that shit. Plus a religious twist. Keep your head down to avoid catching the ire of the militant Inquisitor force. Use mysterious cybernetic implants to open your brain to the truth beyond. Find gigs on the Aethernet through the mysterious Oracle. Tons of fun shit.

Rather than actually using all of the rules I created then, which are mostly just lightly edited versions of Apocalypse World, I'll stick pretty closely to the AW moves and simply mod them with some of the rules I created. Here are the big changes, under the cut...

Cyberpunk obviously requires some kind of mechanical skill, so I've decided that Sharp will encompass anything analytical and practical, while Weird will be replaced with Savvy to represent all things mechanical and cybernetic.

There's a new tracker alongside XP, and it's called Gnosis. It represents your metaphysical journey, and unlike XP, it can be increased or decreased in play through different moves. When the Gnosis gauge is full, it resets to 0 and you take a Revelation.

A Revelation is some dark truth about the world and the character's place in it that they've stumbled upon. Certain moves will allow them to walk these back and unlearn them. In addition, if the character's health gauge is empty, rather than dying they can choose to gain an Apocalypse- a dire, hopeless statement about reality which can not be removed once it's added. If you've got 5 Revelations (including Apocalypses) and would gain another, the character is done for.

Three new basic moves. Hack Into Something, which is pretty self-explanatory. Indoctrination, where the character can attempt to unlearn horrible truths about the world to reduce their Gnosis. And Appeal to a Power, where the character can request assistance from a higher being. I may also write a move for making a pact with a demon and for fixing shit, but I'm not sure yet!

Body mods. They're categorized as Aesthetic, Functional, and Psyche. Aesthetic mods are basically just for flavour. Functional mods have specific physical benefits. Psyche mods have more metaphysical benefits. You can only take as many mods as your mod capacity, which starts at 2 and can be increased with advancements.

My plan is to play several characters at once, as I don't think this will be particularly difficult for me and I would prefer to have several stable main characters rather than one and a bunch of NPCs.

The playbook concepts I'm thinking of going with for my characters are the Inquisitor (a holy lawkeeper inexplicably drawn to heresy), the Fake (a person with an addiction to cybernetics), and the Glitchmancer (one who wields their knowledge of reality to bend it to their will). I'm going to be fleshing out who they are and the world they live in tomorrow!

#so excited to start this :3 it's like a little project!#and when i get good enough at it and if i save some of the files to my phone i can just like. play on the bus#hell yeah#solo ttrpg#cybergnostics#<- that's the tag i'm gonna use for this

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

How can you expect to have friends when you lie about who you are? Friendship is based on trust.

Be sure to fill out the survey and make your opinion known in a productive way. I have a second one coming soon. You’ll have all the chances to express your fine thoughts that you could desire.

To answer your question:

This was always an experiment with the terms laid out in a disclaimer I’m often told is too long. It was always clear and there has been an FAQ for a dog’s age. Ambiguity was the game. You give your opinion. If you choose to interact with me to do your research, you don’t have to believe me, but you should be polite and presume I believe me. In other words, give courteous treatment. I treat everyone as courteously as their actions earn.

I am acutely aware that some of the people I most enjoy on the various platforms, are my experimental subjects. Very aware. But then again, I have conversations about life after death with my own food source, so this doesn’t bother me. I am capable of being kind, learn about them, offer help, build a community here, all while watching what I cam to watch. It’s actually very easy. It also doesn’t interfere with my data at all, because I account for it in my questions. The people who call me a friend, have learned that whatever I am, who I am is a constant and they enjoy my company. They know I have boundaries to interactions, and they adhere to them. They comprehend that ambiguity is the point, what they come to think is the point, their ideas are the point. So they play cards with me, don’t much care what I am, and then send me their surveys. Life goes on. Nobody is lied to, because no false word is ever a part of the discourse.

But really, come off it, because you meet highly curated versions of people every day. No one can prove you are who you say you are. They just trust you. You say you’re a trans person or gay or have a condition…nobody questions. They take you at your word and interact as if it’s true until they find out if it is or isn’t. In other words, no one is ever seen. All social media is metaphysically disconnected.

I have not ever and will never lie about how I feel, think, like/dislike, and so on and so forth, of that I can assure you. Everything else is up to you. And all this needless drama and gossip and fictitious manufactured garbage is completely ridiculous and the sort of thing I predicted, but truthfully hate to see.

None of the people I lost were ever my friend, obviously, as I have said. A friend respects what one is doing and the boundaries they set for interactions to maintain integrity. They help with goals. They participate in good faith. They talk disagreements through. They ask questions when something happens that they don’t understand. Friends maintain the friendship. They don’t latch on like a leech and demand one pay attention to only them. They don’t plot and scheme behind one’s back to sabotage. They don’t lie about what they feel. They certainly don’t go around bullying others you know so that they can enjoy being king of the hill for a day. I never had time for any of them. I made time. A real friend comprehends that. I have many friends to prove this out.

So is it possible to make friends in any meaningful way with one’s own identity an unknown? Yes. I do it all the time. With all sorts. Because of that wall between us, I’m often limited in what I can do. I’m also never able to actually be vulnerable in any way to people I enjoy. I cannot actually ever have friends here in the truest sense, and of that, I am also very acutely aware. But I maintain those whom I find are worth it. I don’t owe anyone anything. Not one thing. I give freely of my own will. Or I don’t.

If someone doesn’t like the terms of this arrangement, they are encouraged to leave, as I will not shift anything or cross my boundaries for them. If that bothers them, boohoo. I care only as far as I can, and if I meet resistance or feel my own borders shrinking, then I’m finished. I have my boundaries in a very succinct bio. You don’t like them, you can leave. That’s how the block feature works.

60 notes

·

View notes

Note

Like, obviously, when you read James, he is so mad about British idealism, and that is a sort of backdrop to a lot of his arguments in the book Pragmatism- idk do you have any takes on how [esp Bri’ish] idealism, kantianism and Hegelianism relate with pragmatism, especially the Jamesian kind?

I don’t know enough about British idealism or Hegel to speak much on that connection, though it’s certainly there. Anti-Hegelianism as with James is not a common feature of pragmatism, at least not in every sense; Peirce and Royce were influenced by Hegel and continued to affirm at least parts of his philosophy but distinct from the British idealist reception.

As to Kant, who I can speak on at least somewhat more intelligently, the major similarity to pragmatism as I think many have pointed out is that his critical philosophy shifts attention away from the objective contents of our knowledge to instead examine their conditions of possibility, thus attending to the means by which we actively produce our knowledge. There is in this sense a shift away from what Dewey terms the spectator theory of knowledge, as a kind of passive reception of our concepts, and towards an experimentalist view (and Kant explicitly cites the modern revolution of experimental physics to support his approach), where the knowledge our inquiry results in is mediated by our own interpretative direction of it, and thus involves concepts we ourselves have supplied. This is the beginnings of Peirce’s semiotic-logic that attempts to theorize the formal conditions of knowledge considered as interpretative, i.e. what must be the case for any scientific intelligence using signs to learn from experience. Of course James the anti-logician is even further from this formal viewpoint (Dewey perhaps somewhere in the middle, though perhaps closer to James). All of them are falliblists regarding this knowledge whereas Kant thought these conditions must be known a priori with certainty--but while Kant is very far from a falliblist, in many ways he did already have a pragmatists’ empiricism of a sort, considering knowledge to only be found in reference to our experience--either (empirically) in given experiences or (transcendentally) in the conditions for its possibility--and saw the use of (theoretical) reason beyond this as merely regulatory; for Kant this puts serious limits on metaphysics and speculation, whereas for the classic pragmatists it instead opened the way towards more of a non-dualist metaphysics of experience that theorized, following in the wake of Darwin, the continuity between our minds and the world around us (a path I of course think Whitehead reached the most sophisticated conclusions in so far). In matters of ethics or practical reason there may be even greater differences, since here the validity or invalidity of apodictic necessary, universal ideas comes to the forefront. There no longer is so much focus on a kind of idealized rational discourse as the basis for our ethics, but rather a real, material interaction with the world with the ethical problems therefore more particularized (I think this holds especially true for James and Dewey).

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

She-Ra #0

- Karma -

[Two Years After The Defeat of Horde Prime]

Plumeria

The moonlight of the many Etherian moons rained down and coated the greenery of Plumeria. Plumeria was one of the smallest kingdoms on the planet, there wasn’t anything fancy or kingdom-ly about it. No enormous castles, not even real towns, just a bunce of tree-houses and empty fields. Which in a way was perfect for the refugee clones, the open fields were filled with makeshift tents, with tired, injured, and or defective clones with conditions that had to be looked after, taking up residence in them. Over the two years more and more shelters accumulated since the defeat of Prime and his main armada. It all worked out fairly well, with the clones populating the ground and the Plumerians residing in the trees. They much like most Etherians had mixed feelings about the clones, some were more welcoming than others. Fortunately brawls didn’t break out as often as in some other parts. It was clear that the Princess of the land, Perfuma, wasn’t too thrilled about their presence, but she put on a smile and played nice.

Modulok wasn’t quite sure what the title of ‘royalty’ or ‘Princess’ meant on this world, but it seemed as if the success criteria involved owning some land since there were apparently hundreds of Princesses, some with kingdoms the size of a town, or a nightclub, believe it or not. How the political landscape worked, he did not know. But he didn’t really care either. It was peaceful that was all that mattered to a surgeon and medic like Modulok. The settlement at Plumeria was one of the smaller ones, nowhere near as developed and packed as Doormat or the New Salineas. And again that’s why he liked it, quiet, far away from anything and everything, a grasshopper here, the rustle of leaves there. However something always seemed to go out of its way to find him. Case in point his quite drunk brother, Vultak, who barged into Mod’s tent in the middle of the night.

Vultak clumsily stumbled into the tent, two glasses of some sort of alcoholic drink in hand. He set the glasses on the operating table Mod was currently working on. Before Mod could protest, as he opened his mouth Vultak raised his pointing finger up to him to stop him. V then proceeded to drag a chair from the side to the operating table. V sat down and took a swig emptying one glass. The drunk clone just stared dazed at the patient Modulok was operating on, but caught a glance coming from Mod that was disapproving.

“Do you mind?”

“Not at all, carry on.”

That drew out a sigh from the medic, he was all too familiar with those snappy comebacks as well as his delusional pessimistic rants and ravings, which Mod was sure were about to follow. The two just looked at each other, a sedated individual between them, it was quite a comedic scene to be hold if there were a third party observing.

Modulok had lost his arms in one of the countless wars and had replaced them with cybernetics which could split in two giving him the total of four arms to work with. As a defect Modulok had blood red lenses, eyes and teeth. Not to mention his skinny frame, and lack of weight, and inability to gain weight. He wore a black and red tech suit, not bulky like Hordak’s, much thinner with tubes and cables hanging here or there. Under it you could see his bones and rip cage pressed tight around his skin, in some areas the white bone broke through the skin forming vein-like patterns across his body - common side effects for defects. A unique defect to Mod was that his skin was coloured red, it didn’t mean much, but others thought it looked neat.

Vultak was far more odd and different, some clones even called him the strangest clone alive. One of the oldest living too. V was a defect too, defects liked to stick together, at least most of them, not Modulok specifically. Vultak was thin too, like a walking toothpick. Vultak’s top half of his head was a red glass-looking dome resembling a radar display. No eyes. However a long witch-like nose. And shark-sharp teeth, though that was common with all clones. Possibly his most iconic aspect were his retractable wings being able to extend out of his under-arms, unveiling metallic feathers as sharp as knives. Various experimental technology was incorporated into his arms, giving his wings the ability to cause micro-hurricanes, and gusts of wind. And flight, obviously.

Also, he was thousands years old.

“V, you clearly want something so just say it and get it over with, the less time I spend with you the saner I’ll remain.” Modulok stated tiredly knowing fully well conversations with V could be exhausting. He leaned on his right arm which he placed on the table.

“What? Come on, can’t a brother just want to hang out with his other clone brother from another mothership?...” Mod was unamused and unphased, in the pause and silence his expression did not change. “And also my dearest, most awesome, talented brother, who is a doctor... I could... use some of that reeeeeally good tastin’ medicine that only a certified medic like you can hand out.” Vultak gave him a smile and tilted his head.

Mod gave him an eye roll, “I am not handing you the pills!”

“Oh come on, Mod! This stuff’s getting out on the street anyway! You’re not upholding some moral high-ground, you’re not holding society together! Come on, please, just one.”

Modulok waved him off, shaking his head. “Absolutely not. And I’m not trying to up hold anything, I don’t care what happens out there, but it just so happens that when some stupid non-sense takes place out there it means I’ve got more work here.” In a way he was right, Modulok was the most famous medic from the Galactic Horde, known across countless galaxies, being a defect medic and a medic for defects, that increased his infamous status. If anyone, any clone was in need of aid they turned to him for help, to say Mod was busy would’ve been an understatement. “Don’t even get me started on those pills that Hordak and Dryl made, I have no idea what they were thinking.”

The Isle Pills. Small capsules of biochemical engineering, synthesized from the ‘infected’ ‘tainted’ plants of Beast Island. That was the way people described the island, there were many theories about the landmass, a lot of scary campfire stories, disputes about whether it even existed. Its existence was apparently confirmed by the Princess of Dryl. Something about backstabbing and being imprisoned on the island, the clones weren’t sure, and they didn’t care much. But the nature of the island had been kept secretive, partially perhaps because the lab-partners studying the location don’t know many thing about it either.

It is also to be noted that they, the pills, weren’t meant for wide spread public use, apparently the Drylian Princess herself was against the production of it. But somehow they got out. Modulok was sure Hordak wasn’t thrilled that his experimental treatment for his defection was being distributed like hot buns at a bakery sale.

The pills have an altering affect on the consumer’s mood and how they perceive reality. Where the island would have enraptured an individual in their own fears and insecurities, somehow those mad-scientists altered the effect of the flora to envelop the individual in numbness and sleep-like paralysis. Hordak no doubt developed the pills as a way of coping with his defection and all the pain that came with it. So the product became quite popular with other defects. Including V, to no surprise. The pills were addictive and seemingly untested, and someone was making a profit off of it no doubt.

“They probably weren’t thinking, that’s what! If you ask me that Hordak guy is insane. All his bad decisions always seem to bit us in the rear.” The infamous Hordak, a general from a previous life, a defect that was sent to the frontlines by Prime personally, some even have speculated that he was meant to be Prime’s next bodily vessel. So in a sick twisted way, that defect saved him. Funny how life works.

Hordak somehow ended up on Etheria, he doesn’t even know how, somehow he amassed a large following and took over half a continent, destroyed a lot in the process. People hate him, his face, and that means of course many weren’t thrilled about hundreds of thousands of clones falling from the sky and finding a home and shelter on Etheria. Honestly, Modulok didn’t like him much either. Vultak unlike Mod actually quite liked Hordak as he served under him once, V trusted him.

“Mod, they would’ve hated us with or without him at the helm, at the end of the day he’s one of us, the whole universe hates us, we gotta stick together.”

“Where’s your ‘screw everything’ mentality gone to?”

V downed his second glass and wiped his mouth, “Washed away and washed down...” V just stared at the now empty glass inspecting it suspiciously as if he was looking if the glass was withholding additional liquid from him. It became obvious that V was thinking, contemplating something, he placed the glass down with a ‘clink’ on the table. “...I’ve been getting the nightmares again. And it’s getting worse, it always does. It’s not long ‘til the nightmares start coming out during the day, while you’re awake.”

Modulok understood, of course he did. He too had went through some harrowing experiences, war is never a good thing for the mind. Mod was an excellent surgeon and doctor, he can do some miracles with scalpels and bandages, he could take care of physical wounds. But there were wounds and scars that he couldn’t heal.

Vultak continued, “Do you believe in karma, Mod?” The question gave the medic pause, he didn’t quite know how to answer that, and he was sure this was one of those questions you don’t answer as V was going to no doubt continue and give his own answer. But the short reply would’ve been ‘no’, Mod didn’t believe in any higher power or any metaphysical concepts such as fate or destiny, it all rather felt far-fetched to him. “That our actions and deeds from our previous lives affect and decides our fate and fortune in the future?

That the future takes roof in the past? You do good, you have good fortune, a good life awaits you. You do bad, you have bad fortune, hell’s coming your way. Revenge and retribution on a cosmic level. It’s the universe’s way of punishing the evil and the wicked, that’s us by the way.

And we do deserve it, don’t we. I mean we’re literally walking, breathing, war machines, our sole purpose was to destroy, perpetuate war and cause all around carnage.

Everyone always wants to blame Hordak for Etheria hating us, but every single one of us has had a part in conquering half the damn universe! Countless worlds either chained or turned to dust, all thanks to us, all of us.

All the terrible things we’ve done, and now what? We just get to have a happy ending? No. No, no, no. Karma’s just getting ready, reeling back, ready to backhand all of us to oblivion. We gotta suffer first... Karma’s balance, karma’s proportional. Which isn’t good for us since we did a lot of wrong-doings. Remember the Siege of Denebria, the War for Primus, the Taking of Trolla, the centuries-long Massacres at Epsilon-19, everyone wants to forget that hellscape death-trap. But we just can’t, some things claw their way back to the surface from below all that brainwashing-sauce.

And that’s just the horrid stuff we remember!... Can you imagine how many lives we’ve forgotten? How many years we’ve lost? How many people we’ve forgotten? That four eyed freak robbed us of everything that made us, us!... All that stuff’s gonna bite us in the back.”

Modulok simply listened, he was used to V’s rants and ravings, but all that... seemed different. Usually V made out everything to be a joke, never taking anything serious, he was a jokester. The nihilistic joker seemed to be subdued, some sort of seriousness, some existential dread on his face. Vultak was genuinely opening up to Mod, and he appreciated that. But it was a shame they had to get drunk first before having conversations like that.

Mod became gradually more worried as V continued with the dialogue, after he paused and just began to stare blankly at his glass again Modulok responded, “I appreciate you opening up, kind of, V, I just wish it didn’t take the influence of alcohol... [sigh] Look, V, I know tomorrow is never certain, and that we all carry the weight of scars on our brittle shoulders... but please believe me when I tell you, that everything will be okay, everything will get better. Don’t drown yourself in poison. The world’s not falling apart, and neither should you.” Mod placed a hand on his brother’s shoulder, trying to comfort his friend.

Vultak simply looked up at his brother, his face blank, he knew Mod meant well, but it didn’t help much to comfort him. And so V hopelessly replied, uttering almost a warning, “Just you wait doc, the sky’s gonna come crashing down on our heads.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

So, Villa how did Dot find out about Ultra Woman? And why did she leave in the first place?

*This story is heavily based on the Mega Man Archie comics.

“Hey, mum?” Dot asks her creator, Doctor Villa “I thought I was your first robot. WVN-00A.”

“That’s right.” Villa responds with a smile

“Then... who’s WVN-000, ‘Lyra’...?” Villa froze, and glances to the screen that her daughter was looking at.

“See?” Dot says pointing to the name, “I was cleaning up the database when I found this. Is it an error?”

Villa sighs. “That... that isn’t an error.” She says, “Lyra was your older sister.”

Dot’s eyes light up. “Really?! Where is she? When do I get to meet her?”

“I’m sorry, Dot. But I’m afraid you’ll never get to meet Lyra.” Villa says sadly “she was my first triumph, and my greatest failure...”

“I... I don’t understand. What happened?” Dot asks.

That’s when Villa began to explain what had happened many years ago. When she was younger, more naive, and just beginning her life’s work. Back when She still counted Doctor Wily as a friend...

~~~

“That’s it Albert! She’s all done!” Villa says with a smile, lifting the goggles up onto the top of her head.

“Mmm..” Wily placed a hand to his chin, examining Villa’s newest creation. “It’s awfully... human-looking, Winter.” He says “Your military contract was for an advanced combat robot. You’ve built a... young lady.”

“And” Villa says “And my robot master line WILL be capable of advanced warfare --as well as a myriad of other advanced mental processes. I’ll get them their weapon, but this prototype, My girl, will stay with me.”

“Hmph. I’d say... you were taking your love of robotics too far, but then I’d be a hypocrite.” Wily says with a softened smile to his friend. “Let’s wake her up.”

“Right. Wake up, dear, Good morning...” the robot girl sat up on the work table, her long blonde ponytail moving over slightly as she rubs her eyes. “...Lyra!”

“...hello?” Lyra says, hesitantly, before finding herself suddenly picked up off the table and into a strong hug.

“Welcome to the world my lovely girl!” Villa says happily “I am your creator, Doctor Villa!” She allows Lyra to sit down once again. “How do you feel? The self diagnostic should’ve kicked in first thing.”

“I feel... fine?” Lyra responds “all systems report nominal.” She looks around

“I... I feel... confused. Overwhelmed. Disoriented. I know we’re in the ‘lab’ and what a ‘lab’ is but... why?”

Villa smiles with excitement “do you hear this, Albert? She’s self aware! Not five minutes online and she’s already thinking metaphysically!”

“Mm-hmm.” Wily replies scribbling notes down on a pad “Don’t mind me... just taking the measurements you’ll need for the weapon upgrades later. You’re welcome, by the way.”

Lyra blinks and looks at her hands “w...weapons?”

“Don’t worry about that now. You’re taking the first steps to bridge the gap between humanity and robotics.” Villa places a hand on Lyra’s shoulder. “You have data, but what you need now, is culture.”

Villa took Lyra out to see the city. The large buildings that seem to tower over everything, She bought Lyra a long purple scarf that she was fascinated by, She took her to the museum to see wondrous pieces of artwork, to the forest area where she got to feed real, organic birds and a deer, and finally to the symphony in the park as the moon finally began to rise.