#notro

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Pololo beetle on Chilean firebush flowers.

#nature#biology#plants#flowers#notro#astylus#bug#bugblr#beetle#pollinators#wildflowers#nectar#chile#insecto#insects

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Corazón rojo y cachañitas 🦜 La ventaja de tener OCs es que prefiero experimentar con estilos nuevos en ellos en lugar de arruinar un fanart de alguna franquicia o etc 🥲👍 Sigo dibujando árboles como a los cinco años 🤣

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notro

1 note

·

View note

Text

[PT: Bachneisgender

Bachthrósgender /end PT]

🍂 Bachneisgender 🍂

(From the Greek word “μπαχαρικό / bacharikó” meaning spice and the Latin word “brunneis” meaning brown)

A gender tied to Brown/Tan spices such as Cumin, Nutmeg, Carom, Cinnamon, and others. The user may feel their gender connects to the aroma, aesthetic, or taste of brown/tan spices. This gender can also feel warm and cozy.

Some suggested pronouns:

•Cinna / Cinn / Cinnas / Cinnaself (or cinnamonself)

•Nut / Meg / Nutmegs / Nutmegself

•Car / Om / Caroms / Caromself

•🍂 / 🍂 / 🍂’s / 🍂self

🌹Bachthrósgender🌹

(From the Greek words “μπαχαρικό / bacharikó” meaning spice and “ερυθρός / erythrós” meaning red)

A gender tied to red spices such as Sumac, Paprica, Ceyanne, Saffron, and others. The user may feel their gender connects to the aroma, aesthetic, or taste of red spices. This gender can also feel hot and and homey.

Some suggested pronouns:

•Re / Red / Reds / Redself

•Su / Mac / Sumacs / Sumacself

•Pap / Rika / Papricas / Paprikaself

•Cey / Anne / Ceyannes / Ceyanneself

•Saff / Ron / Saffrons / Saffronself

•🍁 / 🍁 / 🍁’s / 🍁self

(Coined by me)

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

WOOOOOO

Credit : notro

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

We don’t want autonomy

Daniel and Miriam live in the community Juan Lincopan, at Ranquilhue, with their three daughters. The community consists of about 300 families living on 400 hectares, and is trying to retake another 1000 hectares. They live amongst gentle, rolling hills, partially forested, above the northwest part of the Lleu Lleu. Alongside their house, which they’ve just finished building themselves, Daniel and Miriam have a large garden, and higher up on the hill a field for potato and barley. Someone in the community owns a tractor he rents out for plowing, otherwise they would plow with oxen. In their garden they practice organic agriculture, though they haven’t yet begun to implement this practice in the fields.

They have chickens and a steady supply of eggs, dogs that live in the space under the house and warn of anyone approaching, they make their own bread and cook and heat the house with a wood stove. The house has a water connection but no sewage; all the graywater drains into the garden, and at the edge of the yard is an outhouse.

Proudly, Miriam shows me a line of trees they have planted near their house, all native species like the notro, haulli, arayan, and hazelnut. “We found the seedlings up in the mountains and brought them down here,” she explains. The top of the hill is still covered in exotic eucalyptus trees, which drain the water table, but they’re harvesting the eucalyptus for firewood and slowly replacing them with native species.

They want their daughters to go to school at least until they learn how to read, but there doesn’t seem to be any great pressure to attend. During the days that we stay with them, one daughter seems to be playing hooky permanently. Miriam says she likes to bring her daughters along on land recovery actions so they can get a sense of the struggle, and an understanding that all this is their territory.

In the past, most young Mapuche went to the cities but now an increasing number are staying in the country. What they really need now is an independent school in their community, that will not train Chilean citizens but will be based in the Mapuche worldview.

Both Daniel and Miriam used to belong to the C.A.M. but they have since left it. “The C.A.M. came from the outside and did their work very well, but after the actions they’d leave, and who would receive the consequences? The community. We don’t think that’s a good strategy. We work inside the community to make the struggle from the inside. Even if it takes 15, 20 years.”

C.A.M., though it was the most radical Mapuche organization until recently, proposes autonomy instead of independence, meaning that the Mapuche would receive cultural and political rights, and perhaps their own regional government, within the Chilean state. Some of their lands would be returned to them, though ownership would still be formulated according to the existing capitalist laws. An increasing number of Mapuche are beginning to think that the time has come to openly propose independence, restoring the pre-1880 borders, as guaranteed by multiple treaties with the Spanish crown and the Chilean state, and restoring a sovereign Wallmapu, self-organized according to its own cultural traditions, circular, ecocentric, decentralized, and nonhierarchical.

We talk with Daniel and Miriam about all the similarities between the struggles in Wallmapu and in Euskal Herria, the Basque country. The Basques have won an autonomous government within the Spanish state, and some cultural rights for the preservation of their language, coupled with an even stronger repression that applies the antiterrorist law, torture, and long prison sentences against anyone who fights by any means for the full independence of the Basque people. If that’s autonomy, “then we won’t fight for autonomy,” laughs Miriam.

As the Mapuche struggle strengthens, the repression also becomes more effective. In the past, the police would come into Mapuche communities and get lost, but now they know where everything is. Now there are also police experts who know Mapudungun, the language, and there are more infiltrators, like one university student from Concepcion whose testimony led to several arrests, and who is currently working in Mexico, they say. “Bachelet,” the Socialist president who preceded Piñera, “had two faces. She showed a nice face, and then sent in the repression. There was more repression with her than there is now.”

In fact, a number of young Mapuche were killed by police during the previous government. Three cases are best known, and their names grace the walls of many towns and cities around the Mapuche territories. Alex Lemun, shot in the head near Angol. Matias Cachileo, shot in the back in January 2008 on the estate of a big landlord, his body fell into a canal and had to be fished out. Mendoza Colliu, shot in the back in August 2009. “All of them were shot from behind, none in the front,” Daniel explains gravely. “They were all running!” Miriam adds, and they start to laugh.

They talk about how the struggle is growing beyond the exhausting cycle of action, arrest, and support, and how they need to develop a legal aid organization, as a shield, to function alongside the more militant parts of the struggle.

The Mapuche are by no means victims. These confrontations have taken place during a forceful struggle for the recovery of their lands. At Ranquilhue, there used to be some trailers where timber employees lived, watching over the usurped lands. Around the 2004, the houses were set on fire, and the workers and their families were burned out. Then the state set up a makeshift command center where a number of police lived, to guard the timber plantation. Chile’s strategy of control is highly legalistic, so instead of hiring mercenaries or paramilitaries as they might in other countries, the timber corporations rely directly on police protection.

Around 2006, it was time for the police to go. This time, the community members didn’t come in the night, but in the daytime, in their hundreds, and forced out the police. Since then, that particular pine plantation has been unprotected, and the community has begun clearing it so they can plant fields. Up until then, the forestry company wanted to rent out land right on the banks of the lake, the Lleu Lleu, to build a tourist hotel. The local Mapuche would receive employment, Daniel relates with disgust, working at the hotel for the tourists, selling them vegetables, cleaning their toilets. After the police were forced out, the hotel project was put on hold. Some tourist cabins owned by outsiders were also torched around this time. Around Ranquilhue there are a few vacation cabins owned by Mapuche and rented out in the summers to generate some income, but they are low key and exist on the terms of the community members themselves.

There is, however, a problem with indigenous capitalism. Daniel and Miriam relate one story of a community member who used his lands for small-scale agribusiness, and others who kicked out the logging companies only to continue to harvest and sell exotic trees on that land. But the only companies able to buy the lumber were the very same logging companies, so in the end they didn’t care who controlled or managed the land as long as it continued producing under a capitalist logic. Recreating capitalism within their struggle is a recognized danger.

And then there are Mapuche politicians. There are those who work with the government, and those who try to form political parties to co-opt the struggle, “but there is no Mapuche political party, it doesn’t exist, because we closed the door and they’re left on the outside.”

“The Mapuche can have their independence, but if they lack the spiritual side of things it’s nothing. A Mapuche without newen is not Mapuche.” Newen, they explain, means strength, but it is also the strength of nature, or the energy one receives from the natural world. “The time when the sky goes from dark to light is when you receive all your strength.” Accordingly, there is a specific Mapuche ritual that one undertakes in times of difficulty, getting up before dawn to ask for strength and draw on the power of the world.

#wallmapu#deep ecology#anarchism#revolution#climate crisis#ecology#climate change#resistance#community building#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

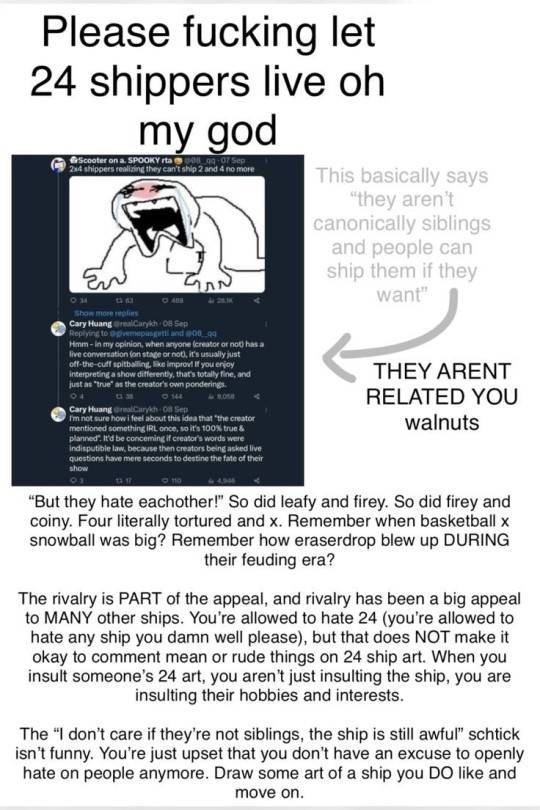

Sigh. As the 10 year long off and on special interest I should've known. (All credits to • Notro • on Pinterest!)

#bfb#bfdi#bfb fandom#bfdi fandom#long time bfdi fans wya#veteran#youtube#youtube series#youtube nostalgia#nostalgia#childhood#autistic#autism#oh boyo

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

D&Doodles: Notro, our party's barbarian

#digital art#artists on tumblr#digitalart#clip studio#digital artist#original character#dungeons and dragons#friends oc#doodle#rough sketch#quick sketch

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

english: the ugly ass hunchback of notro dame

german: The bell-ringer of notre dame :)

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

mi hermano tenia jurao q el antes de venir con notros solo aparecio en una gasolinera y el vivia y trabajaba ahi pero hubo un horrible accidente y nosotros lo encontramos, y me acuerdo q el nos explicaba eso y nosotros: 🧍♂️ok.

......OKAY??????

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cuando las clases proletarias del mundo se vean envueltas en una guerra imperialista, seremos dado por caza quienes no queremos guerras, quienes apoyamos al pueblo y quienes no tenemos sentimientos nacionalistas, esos somos notros, a quienes hemos sido difamados y repudiados, nosotros los Comunistas. Viva el Proletario!!

When the proletarian classes of the world are involved in an imperialist war, those of us who do not want wars, those of us who support the people and those of us who do not have nationalist feelings will be hunted, those are us, those who have been defamed and repudiated, we Communists. Long live the Proletarian!!

1 note

·

View note

Text

🥀📖 Algo inevitable te sigue...

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flor de notro

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guion Teatral

Acto 1:

Escena 1;

Narrador: De todos los lugares, creo que este esta perfecto, Centre D’Accueli, de verdad luce acogedor.

Después de entrar y ver varias habitaciones, escogió una, donde alado de su habitación, se encontraba un señor que parecía ser consumido por Bamako, el calor y los insoportables mosquitos.

Escena 2:

Narrador; ahora que lo pienso bien, aquí realmente no hay un animal mas peligroso que los mosquitos, están por todas partes, y no desaparecen.

Procede a entrar en la habitación.

Narrador: ¡Oh! ¡Pero que sorpresa, esta habitación si cuenta con mosquitera! Justo con lo que iba pensando, casi fui devorado por los mosquitos.

Escena 3:

Narrador; cuanto calor hace, iré a darme una ducha.

Al llegar a la ducha se encuentra a un noruego en la ducha, ya que esta era usada para las 10 personas del piso.

Noruego: ¿Te molesta volver en 20 minutos? Me mata el calor de este lugar.

Narrador: Estoy en las mismas, ¿Cuánto tiempo llevas aquí?

Noruego: Creo que llevo unas horas…

Narrador: Eso es demasiado tiempo, mira tus manos, están arrugadas como las pasas.

Noruego: Es que es el lugar mas frio y libre de calor de todo el lugar.

Narrador: No te Preocupes, volveré en 20 minutos. -Lo dice con mucho disgusto. - Pero cuando regrese, no quiero verte aquí.

Noruego: Trato.

Escena 4:

Al encontrarse aburrido, procede dar una vuelta por el lugar, hasta que ve la entrada de un ser destacable entre las varias personas que ingresaban, Jorge Esteban quien, tomo una de las habitaciones cercanas a él, y mientras se instalaba, escucha a Jorge Esteban hablar con una de las Monjas del lugar.

Jorge Esteban: Asi es, vengo desde Valencia.

Monja: Siempre he querido ir a ese tipo de cuidade’, se ven increíble’ en fotos, pero, pa’ notro’ eso es imposible.

Jorge Esteban: ¡Que va! Claro que usted puede.

Monja: ¿Por qué está usted aquí?

Jorge Esteban: Tengo la intención de realizar un proyecto humanitario y recorrer un poco África Occidental.

Monja: Le deseo buena suerte.

Jorge Esteban Procede a sacar sus artefactos de fotografía y los esparce en la cama.

Jorge Esteban: Le agradezco.

La monja junto a Jorge Esteban sale de la habitación.

Escena 5:

Narrador: debería ir a mi habitación, creo que estorbo un poco estando en los pasillos rondando.

Regresa a su cuarto.

El se asoma en su ventana y ve como Jorge Esteban formaba un gran escándalo, todos de unían y formaban parte de la fiesta.

Acto 2:

Escena 1:

Al día siguiente, nuestro narrador decide ir a conocer un poco más del lugar.

Aquí el narrador conoce la vida de cada uno de los habitantes del área. Aquí es donde aprende un poco sobre las interacciones sociales, chistes y promesas, el habiente caluroso de la cuida, entre mas cosas de la sociedad.

Narrador: Mira, ¿Qué es esto? Parece ser una festividad, veamos.

Entra en la festividad.

Narrador; ¿Esos no eran los niños de la entrada? Se ven más alegres. Mira como transforman todo el ambiente, ahora todos bailan.

Al momento de volver, en el auto bus conoce a un señor, un comerciante de Mopti.

Comerciante: No eres de por aquí, ¿no?

Narrador: ¿No, usted?

Comerciante; No, tampoco, soy de Mopti.

Narrador; oh, que locura.

Comerciante: ¿A dónde va?

Narrador: Solo exploro un poco el lugar.

Comerciante: Si le interesa conocer culturas, la Tuareg es la mas pura, en todos los sentidos.

Narrador; ¿A qué se refiere?

Comerciante; Son un poco retraídos de la sociedad.

Narrador: ¿No los quieren?

Comerciante: No. No. El problema es que, ellos no están interesados en las figuras intelectuales occidentales y prefieren mantenerse alejados del mundo exterior.

Narrador: ¿Por qué?

Comerciante: Supongo que es para mantener su tribu, o tal vez se basa en su religión, la verdad que no tengo ninguna idea.

Narrador: Eso si que esta extraño.

Acto 3:

Escena 1:

El narrador decide ir a visitar estas tribus. Asi que conoce a Mohamed, un nativo que piensa darle un pequeño tour por Mopti.

Narrador: ha sido un viaje super fuerte hasta Mopti. Cuéntame cosas sobre tu vida en este lugar.

Mohamed: La vida es dura, aquí y en el desierto, pero no se iguala a nada. Los tuaregs somos nómadas, siempre nos movemos a través del Sahara.

Narrador: ¿Cómo logran adaptarse a condiciones tan extremas?

Mohamed: Es parte de nuestra tradición y herencia.

Narrador: ¿Cómo?

Mohamed: Desde que somos pequeños nos padres, abuelos, se encargan de enseñarnos que es vivir, como luchar y ser fuertes a cualquier condición que se nos presente.

*Narrador*: ¿Alguna vez te has preguntado si quisieras explorar más allá del desierto?

Mohamed: No, nunca. Para la comunidad, el desierto es lo único que necesitamos.

Narrador: ¿Por qué?

Mohamed: Siempre es por la cultura, no queremos perderla.

Narrador: Cuidan mucho su cultura y sus tradiciones, al parecer.

Mohamed: Es por que sentimos que nuestra cultura es nuestra identidad, y aun que varias personas se sientan cómodos mezclando, nosotros, sentimos que estos somos realmente nosotros, asi que por nada del mundo queremos perderla. En fin, ¿Te gusto la fiesta?

Narrador: Obviamente. Ver a los niños tan emocionados me hizo darme cuenta en cómo la cultura está pasando de generación en generación.

Mohamed: Ese es uno de los puntos por las que las hacemos. Las fiestas no son solo para pasar un buen momento y ya, son una forma de poder enseñar y recordar quiénes somos, fuimos y quienes queremos ser. Como viste, cada una de las danzas, cada una de las canciones, tiene un significado para nosotros.

Narrador: Con todos los cambios en el mundo, sobre las mezclas, sobre uniones de razas, ¿crees que su forma de vivir podrían mantenerla?

Mohamed: El mundo está teniendo cambios, y la mayoría de las cosas, dejaron de ser iguales a cómo eran las de antes. Pero, tengo fe de que alguien va querer seguir con esto.

Narrador: Y si alguien como yo, viniera y quisiera saber sobre ustedes, ¿que quisieras que aprendieran?

Mohamed: Que somos más que lo que aparentamos. Y mas que nada, que nos respeten.

Narrador: Me encanto poder compartir contigo. Creo que he aprendio cosas nuevas, no solo sobre ustedes, si no, para la vida.

Mohamed: Gracias.

Continuara…

0 notes

Text

#Talcahuano Recalentamiento ducto de chimenea, en Los Notros y Algarrobo. Bomberos en ruta. #ECHBiobio https://t.co/7miu6HJeXe

0 notes