#notgreenlandic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Linguistic Excursions (5): Cornish / Kernowek

So after my four previous Celtic excursions it’s fitting that I turn south to visit the final Celtic tongue of the British Isles, Cornish.

Like Manx, Cornish is a revived language, but with a rather longer time between the passing of the last native speaker and the revival – more like 200 years rather than 20-30. So one of the complications this has brought is that there has been less agreement on the exact type of Cornish that should be revived, e.g. Middle Cornish, Tudor Cornish or Late Cornish, and of course there are no recordings available to confirm exactly how Cornish is spoken.

Cornish also did not have a fixed orthography during its last few hundred years, so Cornish revivalists have at times been at loggerheads in terms of the form of writing that should be used to write it (see for example, Kernewek Kemmyn - Cornish for the Twenty First Century (1997) by Paul Dunbar and Ken George, which is essentially a 160 page rant - in the form of a dialogue between the two authors – analysing the criticisms of their orthography by another Cornish scholar, Dr Nicholas Williams, rather than (as I hoped) an introductory grammar of the Cornish language). Fortunately, since then, the disparate groups have come together to cooperate and create a new Standard Written Form of Cornish, which strikes a balance between traditionalists and modernisers, and which also permits alternative forms to be used according to the writer’s style.

Like with Manx, there’s been some attempt to push the revival at the nursery/primary end, as this video suggests, but sadly I couldn’t easily find out what the current status of the early education programme is in Cornwall.

Today’s first text comes from Skeul an Tavas (The ladder of the language), an introductory Cornish language coursebook. The version I have uses the ‘traditional graphs’; another edition is available that uses the more modern ‘main form’ graphs.

Cornish is a Brythonic (or Brittonic) language, and is very close to Welsh, so where possible I’ve shown the Welsh equivalents in the vocabulary, out of comparative linguistic interest.

Text 1

Yma Peder hag y whor, Morwena, ow mos dhe’n lyverva. I a garsa cavos nebes lyvrow tochya an balyow coth y’ga ranndir. Peder ha Morwena a gar whithra an jynnjiow.

“Kemmer with!”

“Yma’n lyvrow na ow codha, Peder”.

Wella a wra aga hachya. Yn y dhorn yma dew lyver da.

“Gwra mires, Morwena, Tas-gwynn a garsa an lyver ma.“

Y whrons i mos tre gans an dhew lyver.

Vocabulary

yma – is . Cf. Welsh (W) mae

ha, hag – and. W. a, ac

y2 – his. Causes the second (soft) mutation to applicable consonants. W. ei

whor (f) sister. NB wh- does not mutate. W. chwaer

ow4 in this case, a verbal noun particle. W. yn, Ir/Sc G ag. Causes fourth (hard) mutation to applicable consonants. Cornish has no fewer than four mutations (!), listed as the 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th state mutations in Cornish text books. Compare this with one mutation in modern Scots Gaelic (lenition), two in Irish and Manx (lenition and eclipsis/nasal mutation), three in Welsh (lenition/soft, aspirate and nasal) and Breton (lenition, aspirate and hard); Breton and Welsh both also have a “mixed” mutation but unlike Cornish it doesn’t create a new scheme of mutated consonants that don’t appear elsewhere. The Cornish mutations are as follows:

- the 2nd state mutation is a soft mutation, like the Welsh soft mutation, causing (p>b, b>v, m>v, t>d, d>dh, ch>j, c/k>g, g>w or Ø)

- the 3rd state mutation is an aspirate mutation, like Welsh aspirate mutation, causing (p>f, t>th, c/k>h, qw>wh)

- the 4th state mutation is a ‘hard’ mutation, creating unvoiced sounds, causing (b>p, d>t, g>c/k/q)

- the 5th state mutation is a mix of the aspirate and hard mutations, causing (b>f/v, m>f/v, d>t, g>wh).

Letters not mentioned in the above lists are not mutated.

mos to go

dhe to. W. i, Cf. Irish (Ir) do, Scots Gaelic (ScG) do/dhan

’n, an the. W. y, yr. Ir/ScG an. Note that as in W. the same form of the article is used for singular and plural definite forms, whereas in Ir/ScG an is singular only.

lyverva library. W. llyfrgell, but cf. W. ending -fa ‘place of’ as in swyddfa office.

i they

a garsa would like. From cara to like. i a garsa they would like. Cornish is structurally a VSO language like the other Celtic languages, but it also has a number of “impersonal” verb forms where the subject/pronoun comes before an uninflected (for person/number) form of the verb, separated by verbal particle a2, which causes the 2nd mutation. So the meaning is something like “[it is] them who would like”. In doing so it gives the impression of an SVO word order, possibly something that might have been influenced by the surrounding English language as Cornish declined?

cavos to get, find

nebes (a) few (takes plural form)

lyver (m) book, plural lyvrow

tochya to touch. Here meaning “concerning”

bal (m) mine. pl. balyow. Not sure if cognate with W. pwll pit?

coth old. Does not seem to be cognate with W. hen, Ir sean, ScG seann, but rather Breton (Br.) kozh

y(n) in. W, Ir i

’ga3, aga3their. Probably not cognate with W. eu their but note the similarity with Ir acu, ScG aca at them, often used in possessive constructions, but not used directly as a possessive pronoun as in Cornish.

ranndir (m) area, district. W rhandir

whithra to search, investigate. Similar to W. chwilio

jynnjy engine house. Presumably from Eng. loanword jynn engine + chi house. Plural jynnjiow

kemmer take (imperative form of kemeres take). W. cymryd, cymer-

gwith care. Here with second mutation as with. As in Welsh, the soft mutation used for the direct object of a verb appearing after the explicit or implied subject. Cf perhaps W. gwyliad(wriaeth) caution

na that. Appears after the noun hence an lyvrow na those books. ‘This’ is ma, used in the same way.

codha to fall. Note that the 4th state mutation after ow4 does not change initial c-

Wella boy’s name

a wra does. This is the impersonal (3rd person singular) form of gul do, which is gwra reduced to wra after the soft mutation caused by a2, as above. Cf. W. gwneud. In this case it is used as an dummy auxiliary verb - much as English do has a dummy auxiliary function as in “do you like that?”.

cachya to catch. From English, presumably. Here in the aspirate 3rd state after aga3 their giving aga hachya ‘their catching’. Similar to Welsh, the possessive pronoun is used with the verbal noun to indicate a direct object, i.e. ‘catching them’. So the phrase Wella a wra aga hachya means lit. ‘[It is] Wella who does their catching’ or more naturally ‘Wella catches them’

dorn (m) fist. From which yn y dhorn in his fist

da good. Same as W. da

gwra do! (imperative form of gul). As above, acts as auxiliary verb for following action verb.

mires to look. Hence gwra mires look!

tas-gwynn (m) grandfather. Lit. “white (gwynn) father (tas)“. Grandmother is similarly dama-wynn “white lady”.

y whrons i they do. y5introduces the statement form of the verb (cf. Welsh fe, mi) and takes the 5th state mutation (softening and devoicing g-), which in this case converts gwrons to whrons. As above the verb is acting as an auxiliary to mos go.

tre (f) town, farm (seen in the names of a number of Cornish villages), but here as an adverb meaning home(wards)

gans with

dew (m) two. Here with soft mutation after an, and note the use of the singular noun after the number. The cardinal numbers in Cornish (which are very similar to Welsh) from 1-10 are:

1 onen/unn

2 dew/diw

3 tri/teyr

4 peswar/peder

5 pymp

6 whegh

7 seyth

8 eth

9 naw

10 deg

Translation

Yma Peder hag y whor, Morwena, ow mos dhe’n lyverva.

Peter and his sister Morwena are going to the library.

I a garsa cavos nebes lyvrow tochya an balyow coth y’ga ranndir.

They would like to find a few books about the old mines in their area.

Peder ha Morwena a gar whithra an jynnjiow.

Peter and Morwena like investigating the engine houses.

“Kemmer with!”

“Take care!”

“Yma’n lyvrow na ow codha, Peder”.

“Those books are falling, Peter.”

Wella a wra aga hachya. Yn y dhorn yma dew lyver da.

Wella catches them. In his hand are two good books.

“Gwra mires, Morwena, Tas-gwynn a garsa an lyver ma.“

“Look, Morwena, Grandad would like this book.”

Y whrons i mos tre gans an dhew lyver.

They go home with the two books.

Text 2

The second text is the Cornish version of a well-known song, and a different orthography has been used, reflecting a Late Cornish approach. See if you can work out the song before you read the translation.

Spladn che steran vian spladn,

War an moar ha'n doar en dadn.

Dres an clowdes, otta che,

Carra jowal 'terlentry.

Spladn che steran vian spladn,

War an moar ha'n doar en dadn.

Vocabulary

spladn bright. Note alternative spelling splann, which can be pronounced /nn/ or /dn/. Further alternative spellings shown in brackets below. Not sure what this may be cognate to, but same word is used in Breton: splann

che (also jy) you. W. ti

steran (also steren) (f) star. Cf. Welsh seren

bian (also byhan/byghan) little, here lenited after feminine noun as vian. W. bach, bychan

war on. W ar

moar (also mor) (m) sea. W. môr

doar (also dor) (m) earth, soil. W daear

en dadn (also yn dann) under. W. tan

dres above, across. W ar draws

clowd, clowdes (also clowdys) cloud(s). From English.

otta behold, here is.

carra (also cara) like. W. caru. The odd thing here is that carra/cara means to like, be fond of, rather than English like=as, which would be avel. I wonder if this is a translation issue on the part of whoever translated the song into Cornish.

jowal jewel. From English

’terlentry.to twinkle. I think the apostrophe here might represent a missing verbal particle ow, described in Text 1 above. Not sure what this word might be cognate to, but note Breton terenn ray of light

Translation

Spladn che steran vian spladn,

Bright, (are) you, little star, bright.

War an moar ha'n doar en dadn.

Upon the sea and the earth below.

Dres an clowdes, otta che,

Above the clouds, there you are!

Carra jowal 'terlentry.

Like a twinkling jewel

Spladn che steran vian spladn,

Bright, (are) you, little star, bright

War an moar ha'n doar en dadn.

Upon the sea and the earth below.

As ever, I hope people found this latest ‘excursion’ interesting. Do let me know if so.

Not sure if there are any Cornish learners on tumblr? If so - corrections or comments welcome!

So where next? I’m basically working my way through my bookshelf and I suppose will work my way round the globe little by little...

#cornish#cornish language#kernowek#cornwall#celtic languages#brittonic languages#revived languages#langblr#endangered languages#welsh#irish#scots gaelic#manx#notgreenlandic

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

Linguistic excursions (1): Scots Gaelic / Gàidhlig

A non-Greenlandic post today, just for a change (maybe to be repeated, maybe not?). A mere 1100 mile hop across the Atlantic to Scotland.

Here’s a short text in Scots Gaelic which is the introduction to the first chapter of Cò rinn e? by Dòmhnall Iain MacIomhair, which is a very accessible short detective novel set on a fictional Scottish island. Appropriately, an English translation of the title would be Whodunnit?

Dhùisg Baile Thorcaill madainn Dihaoine mar a b’ àbhaist. Bha mu fhichead taigh sa’ bhaile, ’s bha muinntir a’ bhaile air fad eòlach air a chèile. Baile beag fearainn air a thogail faisg air a’ chladach, coltach ri iomadh baile eile san eilean.

Vocabulary

cò – who rinn – did (irregular form of root dèan do) e – it dhùisg – awoke. Note that the verb appears first in a standard sentence in Scots Gaelic (VSO order). Past tense form of root form dùisg wake, awaken. In Scots Gaelic the root form (dictionary form) of verbs is the second person imperative. For regular verbs, the past tense form is formed by lenition of the root where possible, which means changing the initial consonant to its “aspirated” equivalent (adding h) where possible (b, c, d, f, g, m, p, s + vowel, sn, sp, sr, t), and where the verb begins with a vowel (or the silent fh + vowel), an epenthetic dh’ is added. Lenition is not possible with l, n, r, sg, sm, sp, st (at least in writing, there may be a change in pronunciation for past tense l, n, r). baile (m) – town, village Thorcaill – of Torquil. Base form is Torcaill, but here with lenition showing the genitive case, possessed by baile. So Baile Thorcaill - Torquilstown madainn – morning Dihaoine – Friday. madainn Dihaoine on Friday morning. mar a b’ àbhaist – as usual (past tense form). Literally “as it was custom”, from mar like + a that (relative pronoun) + bu was + àbhaist custom. In the present tense this would be mar as àbhaist but since the main sentence is in the past tense, the past tense of copula is (being part of as = a + is) is replaced by a bu, with shortening to b’ bha – was (irregular past tense form of root bi be) mu – about. fichead (m) – twenty, a score, here lenited after preposition mu taigh (m) – house. Fichead takes the nominative singular form, so fichead taigh – twenty houses. sa’ – short form of anns a’ in the. The basic (nominative) form of the definite article for masculine nouns is an (am before b, f, m, p) but after a preposition like anns the dative case applies, which means (in the case of a masculine noun like baile) lenition to bhaile and reduction of the article to a’. ’s – and, short form of agus. Another shortened version is is. muinntir (f) – people. In this case paired with baile in genitive form, which like the dative requires lenition for the noun and reduction of the article to a’. Muinntir a’ bhaile – (the) people of the village. Note that where a first noun governs a second noun, the first noun cannot take the definite article, but a definite meaning may still apply, as it does here. air fad – altogether, completely eòlach (air) – acquainted (with) cèile (m/f) – another, fellow, spouse. A chèile – each other (literally: “his other” with a (+lenition) his) beag – little fearann – land, country, here in genitive form fearainn of the country. The genitive form of nouns and adjectives often takes a “narrowed” final vowel form, where a “broad” vowel (a, o, u) is narrowed by adding (or being replaced with) -i-, which also causes palatalisation of connecting consonants. air a thogail (which had been) built. Literally “on its building”. Scots Gaelic creates a perfective form by using a combination of air (on) with the possessive form (a + lenition: its) of the verbal noun, here being togail from root form tog build. faisg (air) – close to cladach (m) – shore, here in the dative case following preposition air, as with baile earlier. coltach – like, which appears with preposition ri to iomadh – many, an adjective that appears before the noun. Normally adjectives lenite the following noun but iomadh is an exception. iomadh baile many villages eile – other san – in the, short form of anns an in the , but here probably best translated as on the eilean (m) – island

Translation

Dhùisg Baile Thorcaill madainn Dihaoine mar a b’ àbhaist.

The village of Torquilstown awoke one Friday morning as usual.

Bha mu fhichead taigh sa’ bhaile, ’s bha muinntir a’ bhaile air fad eòlach air a chèile.

There were about twenty houses in the village, and the village people knew each other intimately.

Baile beag fearainn air a thogail faisg air a’ chladach, coltach ri iomadh baile eile san eilean.

A little country town, built close to the shore, just like many other villages on the island.

---

Hope you liked this little piece. Very happy to take questions and - I’m quite sure there may be some - corrections. All welcome.

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

Linguistic excursions (3): Manx / Y Ghaelg

After my recent 'excursions’ to Scotland and Wales, I'm doubling back and heading north to the Isle of Man to have a brief look at Manx.

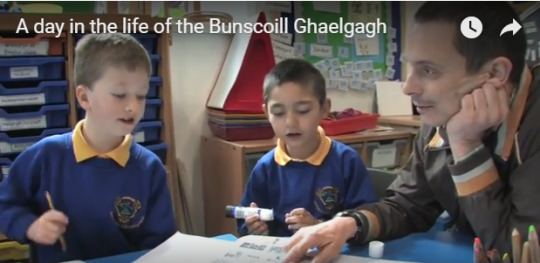

A curious little language, once extinct and now in the process of being revived. I was a bit sceptical about reports showing about 1000 or so speakers (presumably using a broad interpretation of what it means to be a speaker) but if, like me, you are happy to be convinced otherwise, you have to watch this beautiful 10 minute video about the children and staff at the Bunscoill Ghaelgagh.

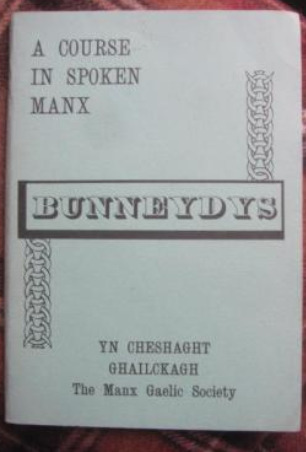

Anyway, the exercise below is taken from Bunneydys - a course in spoken Manx, published by Yn Cheshaght Ghailckagh (the Manx Gaelic Society).

It's a pretty slim tome, with basic conversations and vocabulary set out over 60 lessons. There is no grammar explanation or verb tables, etc. There is a very brief guide to spelling and pronunciation at the front, which is not as illuminating as one might prefer. (For example, for the pronunciation of 'gh', it makes a comparison with Scottish 'loch', but also says "if you can, get a Manx speaker to demonstrate this sound." Ironically this edition of the book was published in the auspicious year of 1974, so I guess it was still possible up to 24 December.... The wikipedia page also has a good guide to the oddities of Manx pronunciation as well as a certain amount of grammar information.

Anyway, a transcript of lesson 58 is set out below. One of the main points of interest for me is how similar Manx is to Irish and Scots Gaelic, while at the same time this similarity is hidden by its rather strange orthography, and so I’ve set out in the vocabulary list below the text all of the cognate forms as I see them. In many places, each of the languages are still cognate, but in some cases Manx is closer to Scots Gaelic, and in others closer to Irish, and in some cases Manx has diverged from both of them. In a couple of cases I’ve not been able to establish a cognate form in Irish and Scots Gaelic, so it’s either been lost from both of them or come from a different source, which is quite possible.

Manx has been separated from Irish/Scots Gaelic since about the 5th century (Russell (1995)), and appears to have been a spoken language only. At any rate, there does not appear to be any evidence of it ever having had a 'Celtic' script like Irish or Scots Gaelic. At some point around the 16th century, a script was devised which was based on the English of that time, based on the use of 'gh' for guttural /χ/, but clearly with some influence from Welsh, in the use of 'y' for /ə/ and possibly other languages having an influence as well.

An obvious downside to the script is that it loses a lot of the more obvious connections between words as they go through their various Celtic mutations such as lenition, eclipsis/nasal mutation and palatalisation, although arguably this is also a feature of the Welsh script to some extent. The upside is that the pronunciation is (somewhat) more transparent - at least to native English speakers - and also to those lovely kids in the Bunscoill!

Conversation

Moirrey: Naik oo mee hene as Juan heose er yn villey 'sy gharey, vummig?

Ealish: Honnick mee shiu, dy-jarroo. Ta treisht aym nagh vaik jishag shiu!

Moirrey: Cre'n fa, vummig?

Ealish: Er y fa nagh mie lesh paitçhyn beggey y gholl seose er yn villey shen.

Moirrey: Cha nel mee smooinaghtyn dy naik eh shin, aghterbee.

Ealish: S'mie shen. Agh cha mie lhiam shiu y gholl seose er yn villey, edyr.

Moirrey: Ta jishag çheet nish. Nagh insh da.

Vocabulary

Moirrey - girl’s name, equivalent of Moira Ealish - mother’s name, equivalent of Eilis, Elizabeth naik oo - did you (sg) see? Irish (Ir) an fhaca, Scots Gaelic (ScG) am faca mee - I, me. The subject and object form of the pronoun is the same; the position determines the meaning. Here it is the object, following VSO verb order, as in the other Celtic languages. Ir mé, ScG mi hene - self. Ir féin, ScG fhèin /he:n/ as - and. Ir, ScG agus, is Juan - John. heose up (location), seose upwards (motion). Ir suas (both meanings) ScG shuas /huəs/ up, suas upwards er on (here perhaps to be translated as in). Ir ar, ScG air yn, y the. Ir an, ScG an, am, a' billey (f) tree. Here lenited as villey, as it is a feminine noun after the article, the same mutation as in Irish and Scots Gaelic. Note different forms for tree are Ir crann and ScG craobh, however Dwelly (1901-1911) lists one meaning of bile as 'cluster of trees' (alongside lip), so this may be an archaic cognate form. 'sy in the from ayns yn. Ir sa ScG 'sa', derived from anns an garey (f) garden, here lenited as gharey. Ir. gardín, garrai ScG gàradh honnick mee I saw. Ir chonaic mé. ScG chunnaic mi shiu you (pl). Ir, ScG sibh dy-jarroo indeed. Ir go dearfa, ScG gu dearbh. Note the regular sound change from ScG -bh /v/ to -u/-oo /u/ in Manx, but also note the Manx divergence from Ir/ScG g- to d- in the adverbial particle. ta is. Ir tá, ScG tha treisht hope. Ir dóchas, dúil ScG dòchas. I haven’t been able to find a cognate form for treisht. aym at me. Ir/ScG agam. Ta treisht aym lit “there is hope at me” = I have hope = I hope (that) nagh - (that) not. Relative negative conjunction. Ir nach, ScG nach nagh vaik - did not see. The v- in the Manx form perhaps reflects eclipsis like in Ir nach bhfaca ScG nach fhaca jishag - daddy. Note unrelated forms: Ir daidi ScG dadaidh. I haven’t been able to find a cognate form for jishag. cre'n fa - why. Ir cén fáth? (lit. “what-the reason”). Note different form in ScG carson (lit “what-for-cause”) mummig mummy. In its lenited form here vummig reflecting the vocative form, as in Irish/Scots Gaelic. Ir mamaí, a mhamaí, ScG mamaidh, a mhamaidh er y fa because, lit "for the reason [that]". Ir mar, óir, ScG o chionn ’s (lit. from the reason that), oir mie good. Ir maith, ScG math. lesh with him. nagh mie lesh (it is) not good with him = he does not like. Ir is maith leis, ScG is toigh/toil leis (lit. is pleasing with him) paitçhyn children, singular paitçhey. Ir leanbh, páiste. ScG leanabh, pàiste, but Ir/ScG plural usu. clann beg small here in plural form beggey. Ir, ScG beag, beaga goll, y gholl go(ing) (verbal noun). Ir dul, do/a dhul, ScG dol, a dhol. It is interesting to note that in Irish and Scots Gaelic, initial broad gh- and dh- share the /ɤ/ sound, and so perhaps the Manx infinitive to go gholl also shared this sound. Was the original verbal noun doll, but given the identity of the two sounds, did it then back-form goll? Just a thought. shen that. Ir / ScG sin cha nel mee I am not. Similar to ScG chan eil mi. Standard Ir has “lost” the cha, giving a different negative form níl mé smooinaghtyn think(ing) (verbal noun). Ir smaoineabh, ScG smaoineachadh dy naik eh that he saw. Ir go bhfaca e ScG gum faca e shin we. Ir, ScG sinn aghterbee anyway. Different forms seen in Ir ar aon chaoi and ScG co-dhiù. But Ir also uses the similar wording ar bith any in other “any” phrases such as duine ar bith anyone. Is Manx aght perhaps the same as Ir acht condition? s'mie shen that’s good, fine, literally 'is good that'. Ir ‘s maith sin ScG 's math sin. Has been said to be the source of colloquial British English, 'smashing!'. agh but. Ir / ScG ach cha mie lhiam I don't like ('not (is) good with me'). Ir ní maith liom ScG cha toigh leam edyr at all. Ir ar chor ar bith ScG idir. (NB Ir idir means ‘between’ and cognate with ScG eadar) çheet come/coming (verbal noun). Ir teacht ScG tighinn nish now. Ir anois, ScG a-nis insh tell (here in root form = 2s imperative). Ir inis ScG innis da to him. Ir dó, ScG da,dha

Translation

Moirrey: Naik oo mee hene as Juan heose er yn villey 'sy gharey, vummig?

Did you see me and John up in the tree in the garden, Mummy?

Ealish: Honnick mee shiu, dy-jarroo. Ta treisht aym nagh vaik jishag shiu!

I saw you, indeed. I hope that Daddy didn’t see you!

Moirrey: Cre'n fa, vummig?

Why, Mummy?

Ealish: Er y fa nagh mie lesh paitçhyn beggey y gholl seose er yn villey shen.

Because he doesn’t like little children going up into that tree.

Moirrey: Cha nel mee smooinaghtyn dy naik eh shin, aghterbee.

I don’t think he saw us, anyway.

Ealish: S'mie shen. Agh cha mie lhiam shiu y gholl seose er yn villey, edyr.

Good. But I don’t like you going up in that tree, at all.

Moirrey: Ta jishag çheet nish. Nagh insh da.

Daddy’s coming now. Don’t tell him.

----

As ever, if I’ve made any mistakes, please let me know. Or otherwise if you’ve enjoyed it, also let me know!

Thinking about my next ‘excursion’ now! Happy to take any suggestions.

(Named) References

Russell (1995), An Introduction to the Celtic Languages)

Dwelly (1901-1911), Illustrated Gaelic-English Dictionary

#manx#manxlanguage#gaelg#isle of man#bunscoill#celtic languages#goidelic#irish language#gaeilge#scots gaelic#gaidhlig#linguistics#comparative linguistics#linguistic excursions#notgreenlandic

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Linguistic Excursions (4): Irish / An Ghaeilge

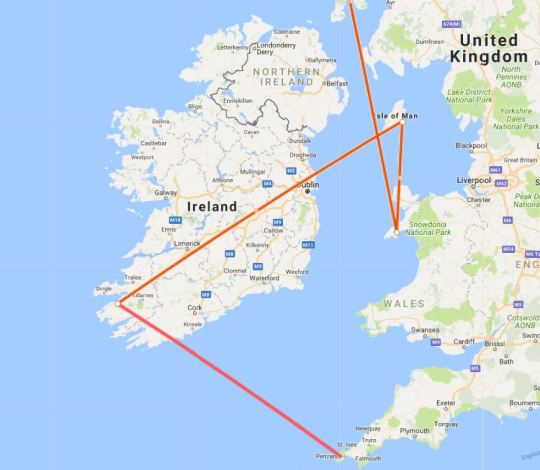

My next linguistic excursion takes us west to Ireland. Previous excursions took us from Greenland to Scotland, Wales and the Isle of Man. Something like this:

This post is an extract from the opening chapter of the novel Gafa (Hook), by Ré Ó Laighléis, an Oireachtas na Gaeilge* award-winning novel, which deals with a teenage boy’s addiction to heroin, covering both the impact on him and on his parents. An English version has been published under the title Hooked . As might be expected it's not a literal translation, and there a few divergences in the passage I’ve selected below, presumably with a view to finding a more natural turn of phrase in English.

*(Assembly of the Gaelic language – an annually held Irish-culture arts festival)

Text

Caibidil a hAon

Leathnaíonn súile Eithne i logaill a cinn nuair a fheiceann sí na giuirléidí atá istigh faoin leaba ag Eoin. Sean-stoca atá ann, a shíleann sí, nuair a tharraingíonn sí amach ar dtús é. Ní hé, go deimhin, go gcuirfeadh sin féin aon iontas uirthi, ná baol air. Tá a fhios ag Dia nach bhfuil insint ar an taithí atá aici ar stocaí bréana an mhic chéanna a aimsiú lá i ndiaidh lae, seachtain i ndiaidh seachtaine ar feadh na mblianta. Ach iontas na n-iontas – é seo. Nuair a osclaíonn sí an t-éadach, a cheapann sí ar dtús a bheith ina shean-stoca, ní thuigeann sí go baileach ceard tá ann dáiríre. Sean-tiúb ruibéir is cosúil, agus dath donn na meirge air – é scoilteach go maith nuair a dhéanann sí é a shíneadh. Tá cinnte uirthi aon chiall a bhaint as sin ar chor ar bith.

Vocabulary

caibidil (f) - chapter

a haon – one. aon is one but cardinal numbers by themselves have an introductory a (+ h- before vowels, i.e. aon and ocht)

leathnaíonn – broaden. Root form leathnaigh. Cf adjective leathan broad. In the present tense, verbs take an –(a)nn/-onn ending in the 2p and 3p singular and plural.

súile – eyes, singular súil (f)

Eithne – mother’s name, here in the (unmarked) genitive. súile Eithne Eithne’s eyes. In the English translation of this book, this name was changed to Sandra, for some reason.

logall (m) - socket (of eye). Plural logaill

ceann (m) – head, genitive form cinn

a – his, her. When meaning his, it lenites (aspirates) the following word. When meaning her, it does not. Hence i logaill a cinn in the sockets of her head. You get the sense here but clearly this doesn't translate literally as an expression.

nuair – when. Derived from uair hour, time

a - relative conjunction, that, which (+ lenition).

feiceann sí – she sees

na giuirléidí – the implements. Singular giuirléid (f)

atá - which is/are. Relative form of tá with fused a-

istigh – inside. Here the implication is perhaps of being pushed inside/tucked inside.

faoin – under the. Fused form of faoi under + article an.

leaba (f) - bed

ag – at. ag is used to mark possession in Irish, i.e. “to have”, as in Tá leabhar agam I have a book, but also as an alternative to the genitive as here: leaba ag Eoin – Eoin’s bed.

sean old. Note that the adjective sean usually precedes the noun it describes, as shown in sean-stoca old sock (and lenites the noun, where possible, but not in this case). Note plural stocaí socks

ann – in it. Tá ann can mean there is/are. But I think here the meaning of ann here is of 'occupation/description', see explanation below on ina.

síleann sí - she thinks, from root síl think, intend

tarraingíonn sí – she pulls, from root tarraing pull, draw

amach – out(wards)

ar dtús – at first, from tús beginning

é – it, in the object form here.

ní hé it is not . Negative form of the copula is é

go deimhin indeed, from deimhin certainty

go gcuirfeadh - that (it) would put, 3ps conditional form of cuir put. Note the eclipsis of the verb caused by the particle go that (conjunction).

sin that (demonstrative)

féin (one's) self. sin féin that (fact) itself

aon one, but here any

iontas (m) wonder, surprise

uirthi = ar + í on her

ná baol air. nor (any) danger of it. ná nor. baol (m) danger. air = ar + é on it.

tá a fhios ag Dia God knows. fios knowledge. Lit. Its knowledge is at God or God has its knowledge.

nach bhfuil that (subject) is not

insint - tell(ing) (of), verbal noun form of inis.

taithí (f) experience, custom, habit

atá aici that is at her, that she has

bréan foul, rancid. Plural form bréana

an mhic of the son. mac (m) son, genitive mic, masculine nouns being aspirated in genitive case after the article.

céanna the very, same. Here also aspirated, as required after genitive singular masculine noun.

aimsiú – aim, hit, hit upon, find. a aimsiú to hit upon

lá i ndiaidh lae day after day. lá (m) day, genitive lae. i ndiaidh after, lit. in the back(?) of, so this prepositional phrase takes the genitive.

seachtain (f) week, genitive seachtaine

feadh (m) extent, duration. From which ar feadh + genitive throughout

bliain (f) year. na mblianta of the years. Genitive plural marked by na + eclipsis.

ach but

iontas na n-iontas wonder of (the) wonders. In English this phrase has a positive connotation, but as the meaning here is clearly negative, I would perhaps translate with to [her] great surprise

é seo it [is] this [thing].

osclaíonn sí she opens

an t-éadach (m) the cloth. Note the epenthetic t- which is added to certain words beginning with vowels or s, which reflects a t which in an earlier form of the language existed within the article itself but which now only appears in these 'fossilised' situations, and is otherwise lost. The same process occurs in Scots Gaelic and (I believe) in Manx so it clearly predates the separation of these languages.

ceapann sí she thinks

a bheith to be

ina in his. In Irish a state of being or occupation is expressed by being 'in one's' state. tá sé ina mhuinteoir he is a teacher . Hence ina shean-stoca in this case.

ní not, negative particle in present tense main clause.

tuigeann sí she understands. From root tuig understand. Note the British Isles colloquial form 'twig' with similar meaning, which may be a loan, eg 'when did you twig that something was wrong?'

baileach exact. go baileach exactly

ceard what. In this case, ceard tá ann 'what it is'

dáiríre really

tiúb (f) tube

ruibéar (m?) rubber, ruibéir (gen) of rubber. This spelling wasn’t in my dictionary, which instead lists rubar (m) (gen. rubair)

is cosúil it appears (that) (lit. (it) is like…)

agus and

dath (m) colour

donn brown

meirg (f) rust, na meirge of the rust

air on it

scoilteach cracked

go maith well. Here perhaps a good amount, considerably

déanann sí she does

é a shíneadh to pull it. Note the word order “it-to-pull”

cinnte certain

ciall meaning. Here aon chiall [not] any meaning. A negative meaning is implied here.

baint verbal noun of bain extract, release. Bain as take from, get from, make of here in infinite form a bhaint as. From this ciall a bhaint as make sense of. With uirthi on her denoting (I think) that the lack of understanding here is affecting her.

ar chor ar bith at all

Translation

Caibidil a hAon – Chapter One

Leathnaíonn súile Eithne i logaill a cinn nuair a fheiceann sí na giuirléidí atá istigh faoin leaba ag Eoin.

Eithne’s eyes grew wide [lit. broadened in the sockets of her head] when she sees the implements tucked under Eoin’s bed.

Sean-stoca atá ann, a shíleann sí, nuair a tharraingíonn sí amach ar dtús é.

There’s an old sock, she thinks, when she pulls it out at first.

Ní hé, go deimhin, go gcuirfeadh sin féin aon iontas uirthi, ná baol air.

Not that that, indeed, would be a surprise to her, far from it.

Tá a fhios ag Dia nach bhfuil insint ar an taithí atá aici ar stocaí bréana an mhic chéanna a aimsiú lá i ndiaidh lae, seachtain i ndiaidh seachtaine ar feadh na mblianta.

God knows, she was well used to [lit. not to be speaking of her experience of] finding his [lit. the very same son’s] dirty socks day after day, week after week all through the years.

Ach iontas na n-iontas – é seo.

But to her great surprise [lit. wonder of the wonders] – it’s something else.

Nuair a osclaíonn sí an t-éadach, a cheapann sí ar dtús a bheith ina shean-stoca, ní thuigeann sí go baileach ceard tá ann dáiríre.

When she opens the cloth, which at first she thinks is an old sock, she doesn’t quite understand what is really there.

Sean-tiúb ruibéir is cosúil, agus dath donn na meirge air – é scoilteach go maith nuair a dhéanann sí é a shíneadh.

An old rubber tube, apparently, with a brown rusty colour – it is quite cracked when she stretches it.

Tá cinnte uirthi aon chiall a bhaint as sin ar chor ar bith.

She certainly can’t make any sense of this at all.

-----------

Now it’s inconceivable that I haven’t made any mistakes above… so comments very welcome, as ever! Hope you’re enjoying the trip so far!

#irish#gaeilge#gaelic#celtic languages#linguistics#translations#notgreenlandic#linguistic excursions

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Linguistic Excursions (6): German/Deutsch - “Ist diese Sprache schwierig?”

For my next Linguistic Excursion, I’m moving east to Germany. After having done the five Celtic languages of the British Isles, I did kind of want to do Breton as well, but it required a bit more study, so maybe I’ll come back to that later…

… but in the meantime I found this nice piece of German text, which is from Jan Henrik Holst’s Einführung in die eskimo-aleutischen Sprachen, which I mentioned in my previous post, but as you’ll see it relates to language learning in general and which I think explains a nice point about “language difficulty”.

I’ve not provided a literal translation (or a vocabulary) but rather followed a more natural turn of phrase where I thought appropriate. As ever, happy to answer questions or take corrections.

Text - Ist diese Sprache schwierig?

Laien stellen oft über eine Sprache, die sie nicht kennen, jemandem, der an ihr arbeitet, die Frage: “Ist diese Sprache schwierig?”. Besonders wenn die Sprache von einem “exotischen” Volk gesprochen wird (oder zumindest einem, dem unterstellt wird, “exotisch” zu sein), bekommt man diese Frage leicht zu hören.

Es ist natürlich eine etwas naive Frage. Zunächst einmal konstatieren wir im Vorübergehen, daß darin gewöhnlich nicht die Phonetik einer Sprache miteinbezogen ist; dabei kann diese durchaus dem Nicht-Muttersprachler viele Schwierigkeiten bereiten. Die Töne in ostasiatischen Sprachen, die Implosive in afrikanischen Sprachen oder Unterschiede in der Artikulationsstelle wie velar/uvular in vielen nordamerikanischen Sprachen, und so auch den eskimo-aleutischen, erfordern einige Übung und am besten eine kompetente Anleitung, vorzugsweise durch jemanden der die phonetischen Erscheinungen sowohl vorsprechen als auch erläutern kann. Den Fragenden sind aber normalerweise die möglichen phonetischen Hindernisse gar nicht im Sinn – sie denken an die Grammatik.

Bei dieser Grammatik muß man nun als erstes bedenken, daß die Muttersprachler sie ja auch erworben haben. Es kann also die Grammatik keiner Sprache – auch die ausgestorbenen und die im Aussterben begriffenen machen da natürlich keine Ausnahme – derart schwierig sein, als daß es nicht möglich wäre, sie zu beherrschen. Die Muttersprachler hatten einerseits mehre Zeit zum Lernen zur Verfügung, bekamen andererseits aber auch keine explizite Erläuterungen. Es ist also im wörtlichen Sinne keine Grammatik etwas “Menschenunmögliches”.

Translation - Is this language difficult?

Lay people often ask people working on a language which is unfamiliar to them: “Is this language difficult?” Particularly when the language is spoken by an “exotic” people (or, at least, by a people which is presumed to be “exotic”), this question can come up a lot.

It is, of course, a rather naïve question. First of all, we should say in passing, that the question is not usually directed towards the pronunciation of a language, which can definitely cause a lot of difficulties for non-native speakers. The tones in East Asian languages, the implosives in African languages or differences in the place of articulation such as velar/uvular in many North American languages, as well as the Eskimo-Aleut languages, require some level of practice and ideally some competent instruction, preferably from someone who can both pronounce and explain the sounds which appear in the language. However for those raising the question above, these possible phonetic obstacles are not normally what was meant – they are thinking of the grammar.

One must first remember that native speakers have of course acquired this grammar. Therefore no language – and extinct and dying languages are no exceptions – can possess a grammar that is so difficult, that it is impossible to master it. On the one hand, native speakers have had more time to learn it, but on the other hand they have received no explicit explanations of the grammar. Therefore, in the literal sense, no grammar can be said to be “not humanly possible”.

#linguistic excursions#notgreenlandic#eskimo aleut#linguistics#grammar#phonology#african languages#american languages#asian languages#langblr#olcc

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Linguistic Excursions (2): Welsh /Cymraeg

After my 1100 mile hop from Greenland to the Gàidhealtachd for my last post, today we hop a further 350 miles south to Wales. Since we are still in Celtic territory, I’ll be making a few comparisons to Scots Gaelic as we go through.

This time we have an excerpt from Bedd y Dyn Gwyn by Bob Eynon (a bargain at £0.01!), which is a short adventure novel about a young explorer travelling to Nigeria in the 19th century to map the (presumably fictional) River Yorba.

Text

Pan glywodd e’r lleisiau aeth Cris Hopkins i fyny i ddec y llong. Roedd tyrfa yn sefyll yno yn barod. Roedden nhw’n syllu ar y tir gwyrdd yn y pellter.

Arhosodd Cris yno gyda nhw am funud neu ddau. Yna aeth i lawr i’w gaban ac agor ei ddyddiadur ar dudalen newydd: Dydd Mercher 23 Chwefror, 1895.

Cymerodd ben ac inc a dechreuodd ysgrifennu:

“Mae’r daith hir wedi dod i ben. Mae’r teithwyr i gyd yn edrych ar arfordir Affrica. Mae hi’n chwech o’r gloch yn yr hwyr ac mae’r tywydd yn braf. Fe fyddwn ni’n cyrraedd Lagos bore ‘fory.”

Audio

Also available in audio form!

Vocabulary

pan – when. Welsh is a Celtic language, like Scots Gaelic. Some scholars divide the Celtic languages into P-Celtic and Q-Celtic, reflecting the fact that in some of these languages an original velar /k/ or/kw/ sound become a labial /p/ (or voiced equivalent). So you see a lot of cognate pairs between (say) Welsh and Scots Gaelic with this alternation, e.g. mac son (Sc. Gaelic), mab (Welsh), or còig five (Sc. Gaelic), pump (Welsh). In this case pan is probably cognate with Sc. Gaelic cuin. glywodd – heard (3p sing), past tense of clywed hear. Root form is clyw- and takes a regular -odd to mark the 3ps preterite. The initial c- undergoes the soft mutation to g-, which is required by pan (when not acting as a question). Note also the VSO word order in Welsh, like Scots Gaelic, reflecting their common Celtic heritage. e – he y, yr, ‘r – the. y is used before consonants, and yr is used before vowels and h-; however after vowels, ’r is used, and this takes precedence. llais (m) – voice. Plural form lleisiau. There are lots of different ways of forming the plural in Welsh. aeth – went. Preterite form of mynd go, one of the four verbs with irregular endings in the different tenses (alongside dod come, gwneud do and cael get). i fyny – up i – to (+ soft mutation, as with most simple prepositions) dec (m?) – deck (loan word), here with soft mutation following i. llong (f) – boat. Here in the phrase dec y llong the deck of the boat. In Welsh the genitive is formed simply by placing the two nouns together. As in Scots Gaelic, the article can only be used on the second noun, and cannot be used on the first one, but the definite meaning can be implied. roedd – was (3p singular). tyrfa – crowd. Here meaning a crowd. As in Scots Gaelic, there is no indefinite article in Welsh. sefyll – stand. From which yn sefyll standing. As in Scots Gaelic, Welsh makes use of a verbal noun to express present tense ideas for all verbs (other than bod to be). The verbal noun is formed from the dictionary form and the particle yn (or ’n after vowels). yno - there yn barod – already. Another use of yn (but with soft mutation) is to form adverbs from adjectives, in this case from parod ready. roedden nhw – they were. roedden is the plural form of roedd above, but in Welsh the plural form is only used if nhw they is also used, otherwise the singular form is used. syllu – stare. yn syllu – staring ar – on. But the English translation of yn syllu ar would be staring at tir (m) – land gwyrdd – green (m). Welsh has a number of adjectives with distinct feminine forms, and this is one of them, with feminine form gwerdd yn – in. A third meaning for yn in the same sentence! Here it is functioning as a preposition. When not followed by the article it takes the rather odd nasal mutation, which is only used after yn in and to indicate “my” (sometimes with the word for my itself, fy or ’y). pellter (m) – distance aros - wait. Stem form arhos- from which arhosodd he waited gyda - with. From which gyda nhw with them. Also appears as ’da. am - for munud (m/f) - (a) minute, funud with soft mutation after the preposition neu - or dau (m) - two. Here with ddau with soft mutation after conjunction neu. Note feminine form dwy. yna – then, there. Here meaning then. i lawr - down. From llawr (m) floor, storey i’w - to his, to her, to their. This is a contraction of i + ei (to his, her) or i + eu (to their). caban (m?) – cabin. Here gaban with soft mutation after ’w [ei] his. Note that ei + aspirate mutation means her. Ei gaban his cabin; ei chaban her cabin. The aspirate mutation in only used in a few limited situations, i.e. after: a and (formally), â with, chwe six, ei her, gyda with, tri three (masculine form), tua towards. I understand that the aspirate mutation is not universally followed in colloquial speech in all these situations. ac, a – and. Ac is used before vowels and some other common words like forms of bod to be (e.g. mae) and before affirmative particles fe (see below) and mi. agor – open. Now here the meaning describes a second action that the protagonist took [he went … and opened], so why isn’t this agorodd to show the past tense? The answer is that where there is a sequence of verbs in a sentence and the first is conjugated to show person/tense, the following verbs don’t need to be conjugated and so are expressed with the verbal noun. dyddiadur (m) – diary, clearly related to dydd below. Here ddyddiadur with soft mutation required after ei his tudalen (m/f) – page. Here dudalen with soft mutation after preposition ar on, at. newydd – new. Note the adjective generally follows the noun, as is typical in VSO languages. dydd (m)- day Mercher – Mercury. dydd Mercher – Wednesday (compare French mercredi – which suggests a shared Roman heritage for this day of the week). With soft mutation to indicate a specific day ddydd Mercher on Wednesday. 23 - tri ar hugain, but here it is used as an abbreviation of the “the 23rd of”, and so is spoken y trydydd ar hugain o. Like Scots Gaelic – and Greenlandic! - Welsh uses a vigesimal counting system. So literally meaning “three on twenty”. In Scots Gaelic the same formulation is used – trì air fhichead. Chwefror – February. I assume, like dydd Mercher, this is an adaptation of Latin februārius (via some other language?), but I’m not sure how the initial consonant got from f- to chw- 1895 – un wyth naw pump. In Welsh, the years are expressed with mil (thousand) or un (one) and then followed by the remaining numbers in simple digits, rather than expressing hundreds and tens. cymryd take, stem cymer- giving cymerodd he took pen (m) - pen. Here ben with soft mutation as it occurs directly after the (express or implied) subject. Pen ysgrifennu can be used to distinguish this loanword from the other native meanings of pen (see below). inc (m?) - ink dechrau – start, with stem dechreu- giving dechreuodd he started ysgrifennu – write. Here in verbal noun form, meaning “to write” or “writing” mae - is taith (f) – journey. Here daith with soft mutation, which applies to feminine nouns after the article y. hir – long. Adjectives governing feminine nouns would also (usually) be given the soft mutation, but this mutation does not apply to the h- in hir. wedi – particle indicating completed action (perfective aspect), rather than ongoing action (usually marked by yn). E.g. dw i’n darllen y llyfr I’m reading the book; dw i wedi darllen y llyfr I have read the book. dod – come. wedi dod – (has) come pen (m) – head, top, end. Here with soft mutation after a preposition, as i ben to an end. teithwyr – travellers, passengers. Singular teithiwr (m) i gyd – all edrych – look at arfordir (m) - coast Affrica (f) – Africa. Note ff represents a [f] sound in Welsh, and f represents [v], hence the spelling of loanwords like this. hi – she. The feminine pronoun is also used for abstract concepts like time and weather, so here it would be translated as it. (yn) ychwech o’r gloch six o’clock. chwech – six; o - of, from; cloch (f) - bell. The yn /’n here is used to link mae with the description (six o’clock) in the same way that an adjective or noun would be linked with yn in a predicative sentence, e.g. mae hi’n oer it’s cold; mae hi’n beirianydd she is an engineer. This predicate use of yn requires the soft mutation. hwyr – late. But also in the phrase yn yr hwyr in the evening tywydd (m) - weather braf – fine, good. Note by way of exception this word is not (usually) subject to the soft mutation, despite this normally being required by the predicative yn here. fe – affirmative particle used to make a statement (not with present or imperfect form of bod be). Requires soft mutation. byddwn ni – we will. Here fyddwn with soft mutation after fe cyrraedd – arrive in, reach bore (m) - morning ‘fory, yfory – tomorrow Translation

Pan glywodd e’r lleisiau aeth Cris Hopkins i fyny i ddec y llong. Roedd tyrfa yn sefyll yno yn barod. Roedden nhw’n syllu ar y tir gwyrdd yn y pellter.

When he heard the voices, Cris Hopkins went up to the ship’s deck. A crowd was standing there already. They were staring at the green land in the distance.

Arhosodd Cris yno gyda nhw am funud neu ddau. Yna aeth i lawr i’w gaban ac agor ei ddyddiadur ar dudalen newydd: Dydd Mercher 23 Chwefror, 1895.

Cris waited there with them for a minute or two. Then he went down to his cabin and opened his diary at a new page: Wednesday, 23rd February, 1895.

Cymerodd ben ac inc a dechreuodd ysgrifennu:

He took a pen and ink and started to write:

“Mae’r daith hir wedi dod i ben. Mae’r teithwyr i gyd yn edrych ar arfordir Affrica. Mae hi’n chwech o’r gloch yn yr hwyr ac mae’r tywydd yn braf. Fe fyddwn ni’n cyrraedd Lagos bore ‘fory.”

“The long journey has come to an end. All the passengers are looking at the African coast. It’s six o’clock in the evening and it’s fine weather. We will be arriving in Lagos tomorrow morning.”

---

I hope you enjoyed this second leg of my linguistic excursion! Where shall I head next…?

Also, as ever, corrections very welcome from native speakers (or anyone).

30 notes

·

View notes