#not like sacred philosophical treatises

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Whenever I am thinking very hard about The Locked Tomb, I find it important to remind myself Tamsyn Muir did compare the series to the KFC Double Down.

https://clarkesworldmagazine.com/muir_interview/

#the locked tomb#these books are so important to me#but also they are fun science-fantasy romps#not like sacred philosophical treatises

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Very little is known about Zosimos’s life, but his writing carries clear influences from Christianity, Judaism, Zoroastrianism, Gnosticism, Hermeticism, as well as broader Greek and Egyptian traditions and philosophy. The man was a regular reading and writing machine. It is likely that he wrote far, far more texts than have survived today. For instance, one of his works is titled “On the sacred letter òmega” It is a magical, symbolic exploration of the Greek letter omega. He likely wrote a treatise like this for every letter of the Greek alphabet.

Zosimos’s work comes in two types. The vast majority are practical, full of things like descriptions of alchemical vessels, catalogs of materials, and commentaries on ideal conditions for alchemy. These are catnip for people like myself, but it’s the second type that’s gotten all the attention. These theo-philosophical texts have titles like Authentic Commentaries or “Authentic Memorials” (gnèsia hypomnèmata), and it is here that we see the birth of the idea of “spiritual alchemy.”

More Zosimos of Panopolis, today on Patreon

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

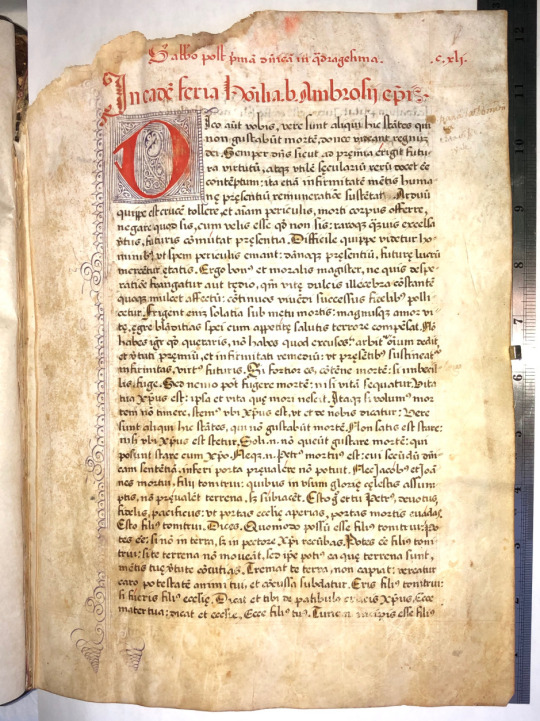

SAINT OF THE DAY (June 1)

"We are slain with the sword, but we increase and multiply; the more we are persecuted and destroyed, the more are deaf to our numbers.

As a vine, by being pruned and cut close, shoots forth new suckers, and bears a greater abundance of fruit; so is it with us."

– St. Justin Martyr

Justin was born around the year 100 in the Palestinian province of Samaria, the son of Greek-speaking parents whose ancestors were sent as colonists to that area of the Roman Empire.

Justin's father followed the Greek pagan religion and raised his son to do the same, but he also provided Justin with an excellent education in literature and history.

Justin was an avid lover of truth, and as a young man, became interested in philosophy and searched for truth in the various schools of thought that had spread throughout the empire.

But he became frustrated with the professional philosophers' intellectual conceits and limitations, as well as their apparent indifference to God.

After several years of study, Justin had a life-changing encounter with an old man who questioned him about his beliefs and especially about the sufficiency of philosophy as a means of attaining truth.

He urged him to study the Jewish prophets and told Justin that these authors had not only spoken by God's inspiration, but also predicted the coming of Christ and the foundation of his Church.

“Above all things, pray that the gates of life may be opened to you,” the old man told Justin, “for these are not things to be discerned, unless God and Christ grant to a man the knowledge of them.”

Justin had always admired Christians from a distance because of the beauty of their moral lives.

As he writes in his Apologies:

"When I was a disciple of Plato, hearing the accusations made against the Christians and seeing them intrepid in the face of death and of all that men fear, I said to myself that it was impossible that they should be living in evil and in the love of pleasure.”

The aspiring philosopher eventually decided to be baptized around the age of 30.

After his conversion, Justin continued to wear the type of cloak that Greek culture associated with the philosophers.

Inspired by the dedicated example of other Catholics whom he had seen put to death for their faith, he embraced a simple and austere lifestyle even after moving to Rome.

Justin was most likely ordained a deacon since he preached, did not marry, and gave religious instruction in his home.

He is best known as the author of early apologetic works, which argued for the Catholic faith against the claims of Jews, pagans, and non-Christian philosophers.

Several of these works were written to Roman officials, for the purpose of refuting lies that had been told about the Church.

Justin sought to convince the rulers of the Roman Empire that they had nothing to gain and much to lose by persecuting the Christians.

His two most famous apologetical treatises were "Apologies" and "Dialogue with Tryphon."

In order to fulfill this task, Justin gave explicit written descriptions of the early Church's beliefs and its mode of worship.

In modern times, scholars have noted that Justin's descriptions correspond to the traditions of the Catholic Church on every essential point.

Justin describes the weekly Sunday liturgy as a sacrifice and speaks of the Eucharist as the true body and blood of Christ.

He further states that only baptized persons who believe the Church's teachings and are free of serious sin may receive it.

Justin also explains in his writings that the Church regards celibacy as a sacred calling, condemns the common practice of killing infants, and looks down on the accumulation of excessive wealth and property.

His first defense of the faith, written to Emperor Antonius Pius around 150, convinced the emperor to regard the Church with tolerance.

In 167, however, persecution began again under Emperor Marcus Aurelius.

During that year, Justin wrote to the emperor, who was himself a philosopher and the author of the well-known “Meditations.”

He tried to demonstrate the injustice of the persecutions and the superiority of the Catholic faith over Greek philosophy.

Justin emphasized the strength of his convictions by stating that he expected to be put to death for expressing them.

He was, indeed, seized along with a group of other believers and brought before Rusticus, prefect of Rome.

A surviving eyewitness account shows how Justin the philosopher became known as “St. Justin Martyr.”

The prefect made it clear how Justin might save his life:

“Obey the gods, and comply with the edicts of the emperors.”

Justin responded that “no one can be justly blamed or condemned for obeying the commands of our Savior Jesus Christ.”

Rusticus briefly questioned Justin and his companions regarding their beliefs about Christ and their manner of worshiping God. Then he laid down the law.

“Hear me,” he said, “you who are noted for your eloquence, who think that you make a profession of the right philosophy. If I cause you to be scourged from head to foot, do you think you shall go to heaven?”

“If I suffer what you mention,” Justin replied, “I hope to receive the reward which those have already received, who have obeyed the precepts of Jesus Christ.”

“There is nothing which we more earnestly desire, than to endure torments for the sake of our Lord Jesus Christ,” he explained. “We are Christians and will never sacrifice to idols.”

Justin was scourged and beheaded along with six companions who joined him in his confession of faith.

Justin Martyr has been regarded as a saint since the earliest centuries of the Church.

Eastern Catholics and Eastern Orthodox Christians also celebrate his feast day on June 1.

0 notes

Text

Modern Western Civilization was not built upon Judeo-Christian Values. It was conceived by Atheist Philosophers. via /r/atheism

Modern Western Civilization was not built upon Judeo-Christian Values. It was conceived by Atheist Philosophers. It's a common meme among neo-conservatives and "born-again Christians" to exalt their admiration for Western Civilization (that they do not actually understand), by insisting on a necessary "return to the sources" of Western Values : through espousing the Christian faith and belief system to resist its enemies, Islam and evil authoritarian China and Russia. But if you peruse into original Judeo-Christian faiths sacred texts and other writings, you do not find these "Modern Western Values", which are namely: Secularism, Tolerance, Freedom of Speech, Separation of Powers, Liberalism, Utilitarianism, Scientific Rationalism, Materialism, Direct Democracy for all, Constitutional Republicanism, Meritocracy, Gender Equality, etc. All of these values and ideals, like David Graeber explained brilliantly, never came from Judeo-Christian sources. In fact, they came from different influences coming from many different culture and civilizations : - Scientific Rationalism came from a Greek Pagan Philosopher: Aristotle, who was highly respected by Islamic Scholars (The Islamic Golden Age emerged mainly thanks to Aristotle work being translated into Arabic). - Constitutional Republicanism were also endorsed by Aristotle, based on the work of Solon. - Materialism came from Epicurus and Democritus whose work were hideously censored and destroyed by the Christian Church. - Separation of Powers are an old Hellenic and Roman Traditions. Judeo-Christians endorsed Absolute Monarchism for millennia (King David and Salomon, then Christ). - Tolerance, Gender Equality and Freedom of Speech were first inspired by the records of Native Tribal Federations (Lahontan), and then theorized by European Philosophers who were mostly Atheist (Kant, Rousseau, Voltaire, Montesquieu...) - Economic Liberalism is now seriously thought to be originated from Islamic Philosophers. The book of Adam Smith had entire plagiarized passages from Arabic treatise on economics. - Direct Democracy for all (not just Aristocrats), were first experienced on Pirate ships, who were anarchist, had multicultural, multiracial crews, as well as many innovative democratic institutions. That's why liberal noblemen were fascinated by pirates at the time, for their defiance of authority of divine right. - Meritocracy based on academic performance came from China: French and German intellectuals were fascinated by China at some point, because of the incredible durability and centralization of their Empire. Voltaire and Leibniz wrote long treatise on the superiority of institutions ruled by excellent students who were selected in national exams (a very old Chinese tradition). Louis XIV created the first modern European institutions based on merit by copying the Chinese system. Christianity itself can be described as an attempt at Hellenization of Judaism, when rich and educated Jews with Roman citizenship like Saint Paul tried to integrate Stoicism and Universalism into his countrymen's culture. It became "Judaism for all, and by force". Not a good combo. But Judeo-Christianity itself at its core ? It provided nothing. The Bible condone religious intolerance, segregation of man and women, hate crime and genocide against strangers, slavery, total obedience to authority without questioning, blind faith, incest, infanticide, slavery, honor killing, irrational circular thinking and of course, patriarchy and Absolute Monarchy. Pretty much what's left of Islam in the Midde-East, when they forgot about Aristotle. Submitted January 13, 2024 at 05:51PM by IluvBsissa (From Reddit https://ift.tt/DMIPxj0)

1 note

·

View note

Text

i feel like radagon’s “succession” (it is somehow different from when godfrey (who makes me think of nothing but the christianization of europe) takes the throne) is meant to represent the church adapting to the enlightenment, because it must. radagon’s lattice holds together a cracked schismatic faith (like his body is held together by the elden ring) like radagon’s vines hold together leyendell. if i were to ask you what elden ring characters have the most numerous and obvious allusions to historical figures you would say marika, who alludes to jesus christ in her crucifixion pose, spear wound, harrowing of hell (removing the rune of death), origin in a persecuted minority followed by becoming the godhead of the culture that persecuted her’s religion, and in her dual nature. let’s not even mention mary.

slightly more astute item description readers/anyone who made it to roundtable hold will point out godfrey is king arthur (famously seduced and betrayed by wife and son.) the extremely recently christianized crucible knights (who look like horned warriors) make it even more obvious that godfrey is the transition from pagan to barely christian europe. he gets rid of his christian name (literally GODfrey) after you get him aroused.

radagon is of the church but married to astronomy. it isn’t shown to be conflicting but instead radagon’s fundamentalist golden order is defined by rationalizing god’s actions in the age of his deafening silence. the fingers have nothing to interpret. it is only through the rejection of the fingers’ monopoly on interpreting the Greater Will (the will of god) that gold mask comes to a new understanding through contemplation. importantly, he receives no divine revelation. the greater will is silent. it is emblematic of the age the game is set in, radagon’s. his understanding is advanced by observation. let’s look at golden order fundamentalist incantations.

“One of the key fundamentals.

The fundamentalists describe the Golden Order through the powers of regression and causality. Regression is the pull of meaning; that all things yearn eternally to converge.”

the golden order principia is the most recent “prayerbook” that you find in the lands between and it’s described as a dense academic treatise. the age of blind faith (marika, placidusax, the tower) and conversion at the point of a sword (godfrey) is dead. it isn’t surprising that the clergy, who jealously guarded knowledge, would produce so many scientists like mendel, copernicus, obviously the jesuits. in liurnia (the descendent culture of the one that invented geometry (the ancient dynasty is greco-egyptian)) you even find the rose church. here is the real wedding of christian mysticism and mathematics. there’s no distinguishment between ancient wisdom, metallurgy, sacred geometry, astrology, architecture, engineering. radagon’s order desperately seeks out what it needs to replace the gaping hole it can feel in itself. it is an extremely self conscious church that can see its own body crumbling.

radagon’s children will never continue the golden order, but who comes the closest? the ones who form a perfect chymical wedding. we can understand radagon now after the dlc as a complete failure who had no chance of anything but stagnation because he could not create the magnum opus (perfect union of matter and spirit, man and woman, the universal solvent dissolving gold.) i understand now this story was meant to be told in the base game and only finished in the dlc. miquella sees the failure of his father/mother’s version of gold, the flawed “philosopher’s stone” who produces MORE. CURSED. CHILDREN. he tries to become a more perfect ingredient/recipe than radagon. radagon was not a perfect vessel, but miquella incorporates what radagon lacks, what marika removed from the elden ring. this is why he uses the eclipse (berserk. sacrifice. death. the undead) to enter the lands of shadow. this is what radagon’s order lacks. the synthesis of ancient wisdom and reason. miquella cleaves himself until he’s a perfect vessel for the god to be used by radahn (the union of the golden lineage and carian learning.) miquella’s answer to the crumbling (the Erdtree became more an object of faith) of the golden order is to go back to the beginning. the haligtree was not wiping the slate clean enough, the root network is rotted (twice! cursed by two gods!) and even, chillingly, tree worship originates in worshipping the grandmother tree in marika’s village. he is trying to bake the perfect cake. so he casts off most of himself. he abandons his own desires, half of himself (notably a ghostly buddhist monk says he shouldn’t have done this near that miquella cross) and his lineage (eyes). he becomes a perfect hollow vessel. to create the other ingredient he used mohg. mohg represents an overlap between the tower and the erdtree, an omen born to the golden lineage with ambitions become a lord, unlike his servile twin. as radahn he is the ideal other half. the red king. miquella wants to be a perfect radagon, capable of working real miracles (childbirth, healing) by recreating marika’s ascension. the end of his search for unalloyed gold.

radagon is a shattered failure that paved the way for miquella. his and marika’s mysterious history can now be understood to have likely been extremely similar to miquella and saint trina, since miquella’s actions are mirroring theirs.

radagon is a broken little divorced thousand year old femboy doll that marika shattered

we need to sexualize radagon and post about him being a cute broken doll

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

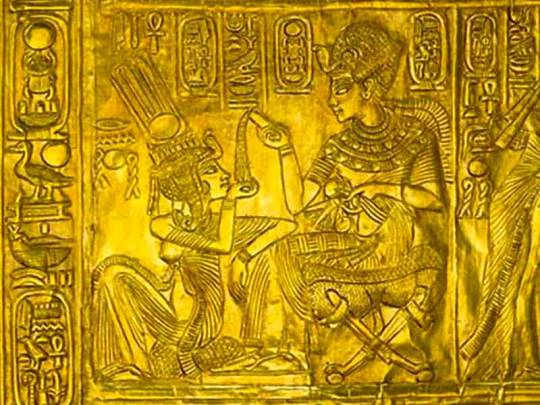

ORMUS : Is It The Philosopher's Stone? - with Barry Carter by Celeste Adams

Since ancient Egyptian times, alchemists have worked in secret, searching to produce something called the Philosopher's Stone or the Elixir of Life. Barry Carter and other researchers believe that ORMUS is related to this search. Since 1995, Barry Carter has been conducting experiments with water modified by ORMUS. He has written numerous articles on the subject and leads workshops around the country where he demonstrates three methods of producing ORMUS water. ORMUS comes from the acronym Orbitally Rearranged Monoatomic Elements, or ORMEs.[†] It was discovered in the late 1970s by David Hudson, an Arizona farmer who noticed some very strange materials on his land as he was mining for gold. During the next decade, Hudson spent several million dollars trying to understand how to create this substance and work with it. ORMUS, which is made from water and other substances, has also been called monoatomic gold, white gold, white powder gold, m-state, AuM, microclusters, and manna. Adams: There's a quote by D. H. Lawrence that says, "Water is hydrogen two parts, oxygen one part, and something else, though we don't know what it is." What did Lawrence mean by that? Carter: There are many unusual properties of water that aren't explainable by the known properties of hydrogen and oxygen or by any concept of how a compound of those two elements should behave.

There are perhaps thirty-two anomalous properties of water that are unexpected. We believe that those properties are due to the presence of ORMUS in most water molecules. Generally, it is believed that the water molecule is dodecahedral or icosohedral. In other words, the molecule is the shape of a geodesic dome, and this shape allows for a lot of space inside the molecule. Some of us believe that the ORMUS elements hide out in that inner space, inside the dome. From that space, the ORMUS can change the configuration of the water molecule so that it tightens or expands. This is the way we think that these elements may modify the structure of water. It's very clear that there's something else other than H2O — two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen — in ordinary water. One person that I've worked with said that triple distilled water, weighs eight pounds per gallon, but water that's made by burning hydrogen in oxygen weighs seven pounds per gallon. The difference between seven versus eight pounds per gallon indicates that there's a pound of something else in the water. Adams: What exactly is ORMUS? Carter: We think it's a new form of matter that appears to have properties of Spirit. It seems to be a transition between physical reality and spiritual reality. We believe that it can be used as a communication tool between spirit and matter. It is, literally, precious metal elements in a new form, a new state of matter. In this state they don't assay or analyze as the precious metal elements. They look like a white powder instead of like a metal. They can even show up as an oil. Because these materials look like other things, they have not been recognized by science. We've extracted the ORMUS element from the air, from rocks, and from water, including the water of the body. We believe that, perhaps as part of the water molecule, they are the carrier of the information that restructures water. Any system for structuring water depends on the ORMUS elements. Adams: What elements can be found in ORMUS? Carter: The ORMUS or m-state materials are thought to be the precious metal elements in a different atomic state. Cobalt 27, Nickel 28, Copper 29, Ruthenium 44, Rhodium 45, Palladium 46, Silver 47, Osmium 76, Iridium 77, Platinum 78, Gold 79, and Mercury 80 have been identified in this different state of matter and, with the exception of mercury, are listed in Hudson's patents. Adams: How was ORMUS first discovered? Carter: These elements appear to have been known in ancient times. The ancient Egyptians were clearly working with the ORMUS materials in their alchemical processes, and the ancient alchemists also were working with the ORMUS elements. You hear in alchemy about "oil of gold" — which is something we've made using the various ORMUS processes. David Hudson also spoke of the oil of the elements, or the oil of metals. Some people actually claim that they remember past lives in which they were working with these materials. Hudson discovered ORMUS when he was working with a gold-mining process. He was the first to make it known, but it's ancient knowledge that has been rediscovered. Now we are applying the tools of modern science to this ancient knowledge. The ancient Egyptians talked about the "white powder of gold." They have pictures on their bas reliefs of little cones called "shewbread." They say these little cones are white bread, and they also say they're gold. How could something be white bread and gold at the same time? Well, now we know. We've got the technology to make the white powder of gold and form it into a cone-shaped bread if we want to. Several of the procedures for extracting or making ORMUS have been adapted from ancient alchemical texts. We believe that the Philosopher's Stone and the Biblical manna are both variations on this state of matter. Some recommended alchemical texts related to the Philosopher's Stone are Sacred Science by R.A. Schwaller De Lubicz, Le Mystere des Cathedrales by Fulcanelli, and Occult Chemistry by Leadbeater and Besant. The premier treatise on the subject may be The Secret Book by Artephius. Adams: Why do you think this information has become available now? Carter: I think it's because all of the areas of science are dealing with the question of how Spirit and matter are connected, and ORMUS helps explain this. All the areas of science are bumping up against this question. We see people in physics saying there's a non-physical realm. David Bohm called it the Implicate Order. According to Bohm, the Explicate Order — physical reality as we know it — is a projection or a manifestation of this non-physical template. The ORMUS elements clearly connect the realms of the spiritual and the physical. We like to compare ORMUS to the use of cellphones. It used to be we always had to use hard-wired phones, now we've got cellphones and we can walk around and talk and communicate with anybody else. So imagine that every cell in the body has a cellphone, and that they communicate with one another until the cellphone batteries go dead or the antennae are damaged. In this analogy, we think the ORMUS elements go in and recharge the batteries on the cellphones and rebuild the antennas. Instead of just being able to talk to the cell next door, the cell in your hand now can talk to the cell in your big toe. In other words, all of the cells are instantly and continuously in communication. Physicists and biologists call this phenomenon of instant communication "quantum coherence." Everything is coherent and in total communication, instantaneously, all at once. Each water molecule gets into resonance with every other water molecule in the body. As the water molecules change their shape and structure, the water is patterned, and changes happen in the body. Information is imparted to the cell and to the immune system, as well as to the other systems of the body. These changes allow the body to heal more rapidly because the communication is perfect.

Adams: Do you have evidence to prove that ORMUS has healing capabilities? Carter: We have photos of a woman's tooth. The tooth had been broken in a stair-step manner, and it literally filled in just from drinking ORMUS water. Hundreds of people have reported benefits that include pain reduction, and improvement or recovery from serious diseases like cancer, AIDS, diabetes, and so on. You can find some of these stories on our Subtle Energies website. Several people have noticed that the ingestion of ORMUS seems to stimulate the kundalini energy flow in the body. A couple of people have said that it's like vacuuming the restricted areas of the kundalini, so that it opens the chakras that are tight or closed. Some people who have a tight heart chakra feel as though they're having a heart attack when they drink ORMUS water. The ORMUS is actually opening the heart chakra. A couple of people with heart problems have gone to the doctor and were told that their hearts had become totally healthy. Different ORMUS elements seem to stimulate the different chakras in a beneficial way. We're not really clear about which ones go with which chakra but there's some speculation about that. One of these days we'll get it nailed down, I'm sure. Adams: What kind of benefits have you experienced yourself from ingesting ORMUS? Carter: I don't hurt anymore. In my mid-forties I noticed that I had carpal tunnel in my wrist, my back ached, and I had general joint pain. When I stood up I would ache a bit. I've been taking ORMUS materials for six years and I don't hurt anymore. Now I jump up from my chair — I don't feel like I have to stand up carefully. I'm fifty-three and I feel great. I feel better than I felt when I was seventeen. I've also been taking one of the other ORMUS elements called ORMUS copper, and my beard is clearly getting dark again. So I've had some very great benefits. I feel as though the clock is rolling back for me.

9 notes

·

View notes

Link

Respectful of Protestant moral and theological decorum, Hayek and Mises declined to engage in an overt assault on Christianity. Intended for the eyes of conservative intellectuals, their market cosmology was assimilated selectively and judiciously by the right-wing intelligentsia. (As Corey Robin has suggested, the reactionary mind seldom displays any adamantine commitment to orthodoxy when power and money are at stake.) What scandalized conservatives such as William F. Buckley, Jr. about Ayn Rand was not that she disavowed religion but that she conspicuously violated the theological politesse that was an essential ingredient of the postwar red-baiting conservative creed.

Rand’s open and pugnacious atheism is central to understanding her novels and philosophical treatises, all of which comprise an appallingly coherent worldview of pecuniary ontology. Scorning Christianity as “the best possible kindergarten of communism,” she vilified charity as a vice, an insidious affront to the productive and meritorious who, like Atlas, bore the undistinguished masses on their backs. “The ultimate viciousness of charity,” she mused, lay in its disregard for achievement as a criterion of human worth. Ignoring the “actual worth” of people—a value determined solely in the marketplace—the charitable cast pearls before the mediocre swine, bestowing “the moral or spiritual benefits, such as love, respect, consideration, which better men have to earn.”

Yet Rand then proceeded to create another religion. She was indeed a “goddess of the market,” as Jennifer Burns has dubbed her, and both she and her pet market catechism—which went by the typically heroic and immodest name of Objectivism—have spawned a large and acerbic exegetical canon. Descriptions of Objectivism as a “religion” or a “cult” began almost with the movement’s inception, and the interpretive imbroglio between the two main Objectivist bodies—the Ayn Rand Institute and the Institute for Objectivist Studies—is as bitter as any denominational dispute among the most convicted prophets of Protestant apocalypse. All the tell-tale elements of cult-worship were clearly there: a venerated founder; quasi-ritualized conversion experiences (many former Objectivists speak of moments of “epiphany”); sacred texts (passages of which are often memorized and cited in a manner similar to evangelical “proof- texting” of the Bible); and internecine factional and personal squabbles (the most acrimonious being that between Rand and Nathaniel Branden, her former second-in-command and paramour). Objectivism certainly shows strong structural affinities with other personality-driven brands of improvisational postwar faith such as Scientology. (Jeff Walker, author of the ham-handed but illuminating The Ayn Rand Cult, likens Rand to Mary Baker Eddy, L. Ron Hubbard, and Werner Erhard.)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE GUIDE FOR THE YOUTH: The Twenty-Third Word.Part10

IN HIS NAME WE GLORIFY

This lecture which has been written with the spiritual support of our beloved and precious Teacher Bediuzzaman and with the influence of the lessons from the Treatises of Light, is a sweet pleasant conversation regarding the Treatises of Light. I am not capable of explaining the value of the Treatises of Light, And I dare not. Please do not suppose that I can do this. Because I am an ignorant and the most novice reader of the Treatises. My cultural background is not sufficient to describe the value of such a masterpiece which acquired such a fame amongst the Nations. I have to admit this.

The great honor belongs to the intellectual, scholarly, virtuous readers of the Treatises of Light who are intelligent and appreciative.

Yes, I had not read any single article in the Press and in our Books that was explaining the value of the HOLY QURAN until the moment I met the Treatises of Light.

Later I understood that the foreign great men admired the Holy Quran more than the intellectuals rising in our country over the last fifty years. The Noble Quran the Sun of the entire World has been placed at the high position which it deserves inside the green silk fabrics in the White House in America.

Inventors, philosopher, doctors, lawyers, psychologists have been studying and making use of the books written on the principles of the Noble Quran. These important persons have been acquiring international fame thanks to the informations they extract from this Holy Book.

Sweden, Norway and Finland have organized a special Board of Scholars that has searched for a Great Book to save their youth. Finally they decided that the HOLY QURAN must be studied by all in order to make the Youth to gain best moral qualities and become broad-minded intellectuals.

There have been many Foreigners who admired Islam and the Quran. Since Non-Muslims admire and make use of the Holy Book of Islam, the smart Muslim Youth cannot hesitate and be negligent any longer.

Our Glorious Lord has responded to the most sacred and most sincere desire of the Youth also in the Twentieth Century.

He granted the TREATISES OF LIGHT (RISALE-I NUR) which are the genuine commentary and interpretation of the HOLY QURAN for this century of civilization. These treatises have been sourced from the Holy Quran and authored within the principles of the Holy Quran.

The author is Bediuzzaman (The Wonder of the Age). Great many scholars and scientists confirmed that the honourable author of the Treatises of Light had been deservedly called Bediuzzaman (the Wonder of the Age). Nevertheless, such a famous and powerful person has not become known to all.

Yes, the Communists worked in our society over the last fifteen-twenty years. Let alone present such Genius of ours, they slander Him with several false stories. They made use of all Media and opportunities in order to succeed in this. They are trying very hard in speaking ill of our Scholars before the Nation. We perceived the truth of the matter only within the last one year. We understood that our Press and Media were full of Communist Microbes thanks to the development of Democracy in our Country. And all the while we were deceived.

We cleaned our minds from the false propaganda and lies about our Religious Scholars. We got rid of the negative impressions about them. Then we embraced our QURAN from which all the genuine intellectuals of the World benefited.

And afterwards we began to study the masterpieces interpreted from the QURAN into our Language. Just like the young generation do not know the true value of the great works of our Great Men such as MAWLANA JALALUDDIN, YUNUS EMRE and EVLIYA CELEBI, the youth do not know much about BEDIUZZAMAN.

However those who happened to learn the existence of such a Precious Person have immediately perceived His high value, and desired strongly to benefit from Him. Inshaallah (Allah willing) many millions of people in Turkey and in the whole World will benefit from the works of this Great Man.

This estimate and wish has been much more reinforced by the power, strength and innovation inside the Treatises of Light.

Yes, the books which can make the contemporary human beings happy are solely the Treatises of Light. This is certain belief of those who read and study the Treatises of Light, not only the words of some Lazy student like me.

Just like that those who embrace the Holy Quran will have happiness in both the World and the Hereafter, those who study and practice the Risale-i Nur (Treatises of Light) which are illuminating and high commentaries of the Quran, will attain the True Happiness. The youth who will study them will have a bright future, they will become intellectual and cultural persons. We believe unshakably that our morality will be elevated as long as we study them...

As much as we study them, we learn obedience to OUR ALLAH, OUR PROPHET, our parents and to the right and just Law... Let the people read them and try them. Then those who read personally will decide themselves on these opinions.

If I can enter into the Masjid of our Prophet Hazrat MUHAMMAD (Peace & Greetings be upon Him) and if I can go up to the Minaret of His Masjid and if Allah gives me a strong voice so that the entire World can hear me, I will proclaim with all my power and strength that :

“the Treatises of Light are the Masterpiece works which will save all the Youth and the Humanity from evil, error, corruption and bestiality...”

I cannot estimate the greatness of the sacred desire of those people who dive into the OCEAN OF LIGHT since the Treatises of Light have awakened such a high desire in me even if I studied only nine or ten books yet.

You don’t need to receive explanations from any source in order to have an idea about the Treatises of Light. You read these luminous works yourself. The Light of the Holy Quran will fill in you and will develop your Faith. The Treatises of Light will convince you that due to belief the World is more delightful than the Paradise. You will begin to love the World not for a transient life but for an Eternal Life. You will understand once more that performing the ritual prayers is a great genuine pleasure.

You will begin to enjoy so much to enter the presence of our Great Allah during prayers that your days without prayers will become full of distress and suffering. You will feel most joyful, most pleasing and happiest moments of your life during prayers. In fact you all know too that those who perform this sacred duty properly will have joy and happiness in the World and in the Hereafter and they actually do.

When you will be engaged in the service of the Treatises of Light (Risale-i Nur), if they invite you to the Paradise while living on Earth, you would not want to go to Paradise yet leaving that service, such a great honor like to serve the Holy Qur’an, by realizing that such a sacred duty and such a high happiness are available right now in this world.

When we say that the world can be considered as a virtual paradise from the point of view of Faith, some may reply: what pleasure have we had till this day in this world life and how in the future can we lead a life of pleasure?

In fact the Treatises of Light have proven with their strong logical proofs and definitive evidences that this World is like a spiritual paradise for the people of Faith and it is like a spiritual Hell for the people of Misguidance.

Risale-i Nur (Treatises of Light) have been authored with the Divine Favor, not written by the author’s own choice, in order to save the Muslims of the 20th Century and all Human Beings from the deep Darkness of Materialist Opinions and terrible

roads of Misguidance. You can read the Treatises of Light continuously with the unhurried behaviour and by learning the meanings of the theological words in them. Some kind of cheerfulness and a strong zeal will be aroused in you like those who work hard night and day.

If you are taking a little slowly, remember that you are under the influence of your carnal mind. Then you must increase the level of your activity immediately. Because the youth is going to end. It is our strong determination not to waist even five minutes in the way to study such books whose values are not measurable.

The fortunate people who study the Risale-i Nur are definitely not concerned with personal material benefits. Because their goals are to obtain the Divine Consent. Thanks Allah, now these are millions of our beloved friends who have perceived that studying and working for the Risale-i Nur is the service for our Holy Book. No one can deny this fact which is clearly apparent for those who have sound minds. There are even some students who do not complete their night-sleeps for the sake of Risale-i Nur Studies which are for sake of Allah.

There are even such true students of THE LIGHT who are at the service of the Treatises of Light: If he is offered the wealth of American Billionaire Ford for copying and publishing some other books instead of Risale-i Nur (Treatises of Light), he will reply as follows even without lifting his pen from the lines of Risale-i Nur :

“Even if you give the whole wealth and the kingdom of the World to me, I will not accept. Because Allah Almighty will give me an inexhaustible eternal Treasure due to the Service of Risale-i Nur. I wonder if that wealth of yours can make me happy? That is quite doubtful. But there is no doubt and misgiving about an Eternal Treasure and a True Happiness which Allah Almighty will bestow on me.”

If a young man was a little late to appreciate the value of Risale-i Nur (Treatises of Light), he will say with great grief:

“ I must dedicate this poor Youth of mine which awakened lately for the Services and Studies on the path of the Qur’an and the Faith for the sake of our Beloved Allah and our Beloved Prophet, absolutely not for the temporary things of this world. I cannot fail to write and publish the Treatises of Light (Risale-i Nur).”

Some people might think that we are disconnected from this World completely when they see that we are so much engaged in the Treatises of Light. On the contrary, we first complete our job correctly if we are single professionals, or our lessons and home works if we are students, or our duty if we are civil servants. Reading the Risalei- Nur has been giving us strength and enthusiasm by multiplying our success in these world affairs.

#islam#muslim#quran#allah#god#isalm#convert#revert#reverthelp#reverthelp team#converthelp#muslim revert#muslim convert#islam convert#islam revert#reminder#prayer#salah#dua#pray#welcome to islam#convert to islam#how to convert islam#muslimah#hijab#hijabi

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Interview

After waiting for half an hour, Pray was well and truly bored. She fiddled with her terminal, then wandered around looking at the bookcases on the far wall. They were full of thick tomes like Interplanetary Development Economics, Sixteenth Edition and A Political History of the Martian Colonies, Volume Six. She rolled her eyes. Whoever used this office was trying to project a very specific image, and was killing a lot of trees to do it. There was a thin layer of dust over the books, too; they probably read them in digital copies, just like everybody else. If they���d even read them. She wandered over to the window that occupied the entire wall behind the desk. It afforded a sweeping view of downtown Abuja. The city was staggeringly vast. Pray knew that, somewhere in the back of her mind, but she never could comprehend just how vast unless she saw it in person. The first large city she’d ever been to in her life was Seattle. Her little apartment there had had a narrow view of the skyline, framed by two taller buildings, and even that narrow glimpse had seemed like a window into a huge, exciting place. Up here, the arcologies and the skyscrapers were two or three skylines all to themselves, strung out below her--and another beyond that, a whole extra city even bigger than Seattle or Vancouver. And another beyond that. And another. And another. She turned away from the window, feeling a little dizzy. She strode over to the desk, and sat down in the enormous high-backed swivel chair. She pushed off tentatively from the desk; the chair spun slowly, almost frictionlessly, in silence. Well, well. Control did not skimp out when it came to office furniture. She gave herself another push.

“Heh,” she whispered quietly to herself. “This is fun.”

Push. Spin. Push.

“Ma’am?”

Pray slapped her hand down on the desk and froze herself mid-spin. There was a tall, thin man, dressed in a carefully tailored suit standing at the door.

“Er… the director will be in in a moment,” he said. “Would you like anything? Water? Tea?”

Pray just shook her head. She only felt a little embarrassed. They were the ones wasting her time, after all.

The director strode in a few minutes later. He was bald, with a bushy gray goatee and a heavily lined face. Pray thought he looked like her grandfather, maybe, except much more serious. He didn’t even blink when he saw Pray sitting behind his desk. He sat in one of the large, heavy armchairs facing her, and spun the console around to face the other way.

“Good afternoon, Ms--what surname do you use these days?”

“Just Pray,” Pray said.

“Very well. Ms Pray. Welcome. I’m sorry to have kept you waiting.”

Pray shrugged. Not exactly an “It’s OK.” More of a “Pretty much what I expected.”

“I’m Director Osondu.” He tapped a few keys on the console and brought up a set of files; from behind the screen they were flipped and out of focus, but Pray could see a photo of her featured largely at the top.

“Your CV,”the director said, indicating the console.

“I never sent you my CV,” Pray said, raising an eyebrow. “I don’t have a CV.”

“We took the trouble of compiling one for you ourselves. We do that with many of our potential employees.”

“I’ve also never applied to work at Control.”

Director Osondu smiled. “No. But I’m hoping I can convince you.”

Pray laughed. “You want to offer me a job?”

The director nodded. “And not a job reviewing reports in Maitama, either. We have an assignment in mind.”

Pray leaned back in Osondu’s chair.

“What makes you think I’d want to work for Control? Heck, what makes you think I’m qualified?”

“Let’s see here. You were born in Washington, yes? In a Radhite community near Echo Valley?”

“Cooper Mountain, actually. People get the two mixed up.” If they’ve heard of them, she thought. Which they never have.

“Ah, yes. Let me fix that.” His hand darted over the console briefly. “You exercised your exit rights when you were sixteen, for reasons involving--let’s see here--personal bodily autonomy?”

“Yes. That’s correct.”

“Our records don’t elaborate on what those reasons were.”

“Good.” Pray stared at him, remaining pointedly silent.

“Ahem. In any case, you spent six years subsequently in Seattle finishing your education, before moving to Europe, then Asia, then South America, then the Antarctic colonies, staying in no city for more than eighteen months at a time. And then three years ago you came to Abuja, and you’ve been here ever since.”

“Yup.”

“What drew you here, if I may ask?”

“I like big cities. I like moving around. I want to see the world.”

“You haven’t moved anywhere in years. You haven’t even changed apartments since six weeks after you got here. You do some analytical work to supplement your basic, mostly for financial conglomerates and political outfits, but with your intelligence and abilities, you could easily find full-time work, enough to live pretty damn well. Even move to Mars, or the outer Solar System if you wanted.”

“What can I say? I’ve never been that interested in space travel. I like high gravity and being able to go outside from time to time. And I like my apartment. It’s cozy. Do you keep a close eye on everybody who decides to use their exit rights as a teenager? ‘Cause I gotta say, this is kinda creeping me out.”

“My apologies. We don’t as a rule, no. We consider the third freedom absolute. However, we have been interested in you for a long time. We just haven’t known… exactly what approach you might be most receptive to.”

“Well. This isn’t a good one, you know.”

“I haven’t finished making my pitch yet.”

“All right. So make it.”

“We want you to travel. In space.”

Pray laughed.

“Absolutely not,” she said. “There’s not enough money in the world.”

The director stood, and walked over to the bookshelf. He touched one finger to his lips, thinking for a minute.

“Forgive me,” he said, after a long silence. “I want to choose my words carefully, because I wish to express myself precisely.” He took a slim volume off the shelf, came back over to the desk, and slid it across the surface. Pray stiffened when she saw the title. It was Radha Munroe’s First Treatise.

“You know that book well, yes?”

Pray nodded.

“Would you agree that it’s, shall we say, convincing?”

Pray nodded again. “Sure. What’s your point?”

“It’s not just convincing. It’s elegant. Learned. Often, even, poetic. So profound, to at least some of its readers, that thirty years after the death of its author it found new life as the textual center of a movement. Something not quite political, not quite spiritual, and not quite personal, but located at the intersection of all three. A new, totalizing philosophy that built a community and transformed lives.”

“High praise.”

“I mean it sincerely. Do you know how many Radhites have exercised their exit rights since the first Radhite community was founded more than two hundred years ago?”

“Not many, I’m guessing.”

“Exactly one. You.”

The director took the book back. Pray could feel herself relaxing as he slipped it out of view.

“It’s not that I agree with everything Radha Monroe wrote. Nor do I think there have not been other Radhites who may have wanted to leave. But such is the persuasion and the power of the Radhite philosophy that, quite without coercion, at least of the kind that would provoke sanctions from Control, they have formed some of the most hermetically sealed communities in the Solar System. And believe me, we monitor the Radhites very closely. Yes, it’s true. We’re very careful. As I said--the third freedom is absolute. The closest thing we have to something sacred in this day and age.”

“They’re very good at brainwashing. So what?”

“The Radhites are uniquely good at it, if that’s the term we’re going to use. Every other community in the Archipelago has some kind of attrition, and the larger the community, the higher the absolute quantity. Religious communes, philosophical societies, intentional communities--it is an absolute. Some have higher attrition rates than others, but they all have them. All except the Radhites. Until you, anyway. And since you, not one. Not even from Cooper Mountain.

“My point, Pray, is that you are exceptional. Your biography alone--the fact you are out here, in the world, for me to speak to--makes you exceptional.”

The director flicked through Pray’s file faster now.

“Your life since, however, makes you even more remarkable. You graduated from university at age twenty, with top marks. You took proficiency exams which could have garnered you the position of your choice in the civil service or at one of a number of academic institutes--or even in Control--but you contented yourself with analytical work on the side. And your analytical work, particularly on emerging social trends, is considered on par with some of the best research collectives. Only an AI might do better--but AI won’t do this kind of thing.”

“AI can’t,” Pray muttered. “They only say they won’t.”

“If you did more than one report every three months, you could be living in a luxurious Japanese arcology. Or on the Moon. Anywhere you wanted, really. But instead you content yourself with a small apartment in Gudu. Lately you don’t even travel. I think I know why.”

“Do tell.”

“You’re bored. Government work doesn’t interest you. Bureaucratic work certainly doesn’t. And you know Control has a reputation for excellence, but you think all we are is glorified paper-pushers and, occasionally, law enforcement. Maybe you genuinely don’t like space travel, but I suspect you think there are simply no interesting challenges to be had elsewhere in the Solar System, so you prefer to spend your time reading and studying and watching the world from afar. You think maybe one day you will find a topic, a cause, a company somewhere that is interesting enough for you to feel really invested in, but you’re not holding your breath. You came to Abuja because it’s one of the biggest cities in the world. It’s home to Control, to a third of all U.N. agencies, and it’s as close as any city to the beating heart of humanity. But even here there’s nothing to draw you in.”

Pray shifted nervously in her seat. A small voice in her head told her to push off from the desk, and just roll her way down the elevator. As though if she did it smoothly enough, the director wouldn’t notice.

“That all sounds very speculative to me,” she said.

“Nonetheless, I think it is accurate speculation. Speculation of this kind is the reason I am valuable to Control. We think you could be valuable to us for other reasons. And we think you could get something in return.”

“Which would be?”

“Something you can be excited about. Would you like to meet an AI?”

Pray cocked her head. Now that. That was something new.

“You do not ‘meet’ AIs,” she said. “They don’t exactly socialize.”

“Nonetheless, I know where you could meet one. One who is very interested in meeting you.”

“You’re messing with me,” Pray said flatly.

“I do not mess.”

“Where? When?”

“Here. And now.”

“And I have to accept your job offer, whatever it is?”

“Not at all. They will help me explain it. Then you can decide whether to accept it or not.”

Pray leaned forward in her chair.

“I’m listening.”

The director entered a command into his console; a large screen emerged from the wall to the left, and flickered to life. What appeared on it was rather like a face, or the ghost of a face: a suggestion of eyes and a mouth and other, less distinct features on a flickering, phosphorescent background that sometimes cohered into something strikingly human, and sometimes suggested something altogether alien. Pray stared at the screen with intense interest; she realized she was holding her breath.

AI did not, as a matter of course, involve themselves closely in human affairs. The dream, centuries ago, had been creatures made in mankind’s image: creatures of humanlike dispositions and intellect, implemented in the medium of a machine. Of androids, perhaps, or things vaster and far more than human in their powers, but human enough in their values and desires that there could still be meaningful conversation between them and us, even if it was as a mere mortal might speak to an angel.

That turned out not to be the reality.

Artificial intelligence, machine intelligence, had indeed come, but it came from a quarter and in a manner no one had quite expected. The result was emphatically unhuman. Not inhuman; not monstrous. But just as the mammalian intellect had inevitably been the outcome of a certain evolutionary process, a certain set of cognitive solutions to specific biological and ecological problems, the machine intellect was a different set of answers to an entirely different set of questions.

Three hundred years ago, after the first tentative and failed attempts to establish a permanent presence in star systems outside the one humanity had arisen in, during the dark age between the second and third space races, the first true, general machine intelligences had been created. The results proved alien and unsettled many; even attempts to record entire human brain states, to provide the AI with as complete an understanding as possible of their creators, had only bridged the gap a little. That unease grew into genuine fear when an AI colony was discovered orbiting a brown dwarf a little under seven light years away.

Their goals, the machines said, were different from ours. They need not be in opposition; they were not our enemy. And they were willing to help us, to be of use to us so far as they were able, but if the utopians of previous centuries had dreamed of a society where man and machine were twined together, a symbiosis of two distinct but complementary organisms, well, that hope seemed to have been dashed. For the most part, they would pursue their own existence and their own ends. Control was entrusted to be the mediators between Core and the AIs, but as far as anybody knew, even Control’s contact with them was only sporadic and brief. Pray had never dared hope she might meet an AI herself.

“Pray, meet Lepanto. Lepanto, meet Pray.”

The shimmering face seemed to nod, and spoke with a synthesized voice that had a hint of the uncanny about it. Such, Pray had heard, was the norm; machines, no less than humans, did not their interlocutors to forget how alien they were to one another.

“Greetings, Pray,” Lepanto said. “I am pleased to meet you.”

“I, uh, yeah. You too,” Pray said. “Welcome to Earth.”

“Thank you. In fact I have been here for some time; we maintain a small presence in Core systems at Control’s expense.”

“Lepanto is a mediator,” the director said. “Their lineage is intended to facilitate communication with our people, but you should be aware, they are merely… less alien.”

“Indeed.” Lepanto’s image wavered, and for a brief moment, was full of a surfeit of eyes and other strange features. “I am here because Control has identified an interest common to my kind and yours. We believe that you, Pray, would be of particular help in solving our quandary.”

“Why me?” Pray asked.

The director turned the console to face Pray, and struck a key. The file being displayed was replaced with an image of a world, something computer generated maybe, or taken from orbit.

“Have you ever heard of a colony world called Ecumen?” the director asked.

“It doesn’t ring a bell,” Pray said.

“It’s old. It was colonized in the 2600s.”

“I didn’t think there were any colonies that old that had succeeded.”

“Nor did we,” the director said. “Until about twenty years ago, when Ecumen was rediscovered by the machines.”

“What did you find out?”

“Distant surveys told us little,” Lepanto said. “We sent a high-velocity probe to the system, to initiate contact. Four mediators, like myself, working in concern. Their report--disturbed us.”

The image on the console changed; various surface features were highlighted or shown blown up, in inset frames. Ecological data. Large urban centers. A handful of small space stations and orbital manufacturing.

“It looks pretty normal to me,” Pray said.

“On the surface, yes,” Lepanto continued. “Artifacts, not apparent to human eyes. Problem akin to Benford’s Law.”

“Explain?”

“The frequency distribution of numbers in data sets. Favors low numbers in leading digits, yes? Consequence emerges from data spanning many orders of magnitude; easy to detect when data is falsified if it fails to conform. Not immediately obvious to human eyes.”

The console changed again; a dozen graphs appeared. Demographic and actuarial data, economic information, patterns of migration, and more that Pray couldn’t make immediate sense of.

“Emissaries spoke to Ecumen, learned of their history. Their societies. Their culture. Sought to understand them as we seek to understand all human worlds. We learned much. But the patterns were anomalous. Irregular. Wrong.”

“So they gave you bad data?”

“No. All data corroborated. Independently verified, from sources and from our own orbital surveys. Problem apparent in the data, not an artifact of the data. Something is terribly wrong on Ecumen.”

“So it’s an outlier. There are almost two dozen colony worlds now. Every one has its own unique environment and circumstances. They can’t all be the same.”

“We have spent more than a decade examining this data. The emissaries brought it to the attention of the collective, which took an immediate interest; more than half our stable nodes were diverted to attempting to understand Ecumen. It is an impossible world. It should not and cannot exist as it does. Population growth rates follow anomalous patterns that do not conform to any understanding of human biology or society, even accounting for specific conditions. Similarly, economic investment. Patterns of land cultivation. Everywhere, something is off.”

“The reports the collectives have compiled are… dense, to be sure,” the director said. “Not all of it is very accessible to our analysts. But Control makes a habit of compiling as much data as it can about human societies and their development. We couldn’t do our job otherwise. And we agree. Something very unusual is happening on Ecumen, and only on Ecumen.”

Pray was scrolling through the data on the console now. It was certainly suggestive of something, but she’d be damned if she knew what.

“And there are underlying patterns here? It’s not just random deviation?”

“No,” Lepanto said. “In fact, the patterns conform to specific mathematical structures that, until we shared with Control, we believe were not known to any humans, in Core or the colonies.”

A series of complex, shifting geometric figures appeared on the screen. “The collectives consider questions of natural science,” Lepanto continued. “It is important to us, as it is to you, to understand the universe. We wish to know many things about it--how it operates, how it came to be. It is one of the few areas in which we understand ourselves to be very like you. We are both curious.”

“And these are?”

“Three-dimensional representations of complex mathematical objects that govern the states of fundamental particles in certain simulated universes. They correspond closely to the patterns we perceive in Ecumen’s human population.”

“So you’re saying there is a natural basis for these patterns?”

“No. All these patterns arise only in universes which have physical laws radically different from our own. Almost all, universes where life, human or machine, could not exist.”

Pray sat back in the director’s chair and stared at the screen, turning over a hundred possibilities in her mind. Yes, indeed. Something strange was going on on Ecumen. Maybe a coincidence. Maybe not.

“And there’s no way this is random?” she asked. “That you’re seeing patterns in chaotic information that have arisen by chance, excluding everything that doesn’t fit?”

“It is not pareidolia, if that is what you mean,” Lepanto said. “Conditions on Ecumen have continued to align with our forecasts. The data is predictive.”

“Are you interested?” the director asked.

“Oh, it’s all interesting as hell,” Pray said. “But what on Earth do you want me to do?”

“We’re sending a delegation to Ecumen. Officially, it’s diplomatic: Control has no presence there, and since Ecumen is interesting in acceding to the treaties, we’d like to open diplomatic relations. And, for obvious reasons, we’re a little nervous about them coming here, in case this phenomenon is somehow capable of spreading. But along with the diplomatic team, we’re sending some researchers, and a few agents to assist them. They, with Lepanto’s help, will conduct an intensive study of Ecumen, and attempt to figure out what’s behind all this. We’d like you to be part of the team. But, of course, I know how you feel about space travel…”

“Fuck that,” Pray said quickly. “I’ll do it.”

The director smiled. He slipped a folded-up piece of paper from his suit pocket and laid it on the desk. “Here’s an employment contract, if you’d like to look it over. If you sign before lunch, there’s an orientation for new analysts being conducted on the 16th floor at two o’clock.”

“That’s it? You don’t want to, like, interview me or something?”

The director shook his head and stood. “Ms Pray, it is our job to identify the best and the brightest, to help them achieve their greatest potential in exchange for helping us safeguard and support the flourishing of the human race. We don’t conduct ‘job interviews.’” He paused for a moment. “You do get an expense account, though. They’ll tell you the specifics at orientation.”

Pray unfolded the sheet of paper and started reading. The director cleared his throat. Loudly.

“However,” he said, “If you don’t mind, I’d like my office back now.”

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

4499 angel number

The angel number 4499 is the quintessence of altruism and sensitivity to other people’s harm.

He is very emotional about all aspects of life. It is primarily focused on helping others.

Number 4499 – What Does It Mean?

The 4499 sacrifices himself for the good of all and always looks after the weak. He cares for those in need, recognizing their suffering.

The 4499 does not want to remain indifferent to the fate of people with disabilities, the poor, the abandoned and all those who need any help.

Number 4499 is extremely sensitive and emotional. Her heart lands at the sight of any injustice.

The more so that he can perfectly empathize with other people’s situation. He bends over him and provides support.

By nature, she is a helpful person, with enormous layers of innate kindness.

Angel Number 4499 is positive for everyone, he is a nice companion with whom you can always have a good time.

What’s more, the 4499 really clings to people. She enjoys new acquaintances, is fascinated by the whole world and the beings living in it – not only Homo sapiens, but all animals.

Sometimes numerological Nines are very friendly, but that’s not always an advantage. It happens that 4499 is susceptible to manipulation and use by other, more cunning individuals.

She often turns out to be too submissive because she doesn’t want to offend the other person.

This approach may not end positively for nine. So she should be careful about who she deals with and what projects she undertakes, both at work and in her free time.

4499 naivety can make someone use her.

However, this is not the worst part. The Deceived 4499 may doubt her mission in life – helping others.

It is true that he will still trust people, but may no longer be so willing to sacrifice for them. This is a great loss to the world, because Nines do the most for him.

Numerological 4499 is spiritual and devotes a lot of her time to personal development.

He reads sacred texts, philosophical treatises and wants to learn new and wonderful things.

He is eager to polish both intellect and intuition – thus striving for self-realization as a good person.

It can even be said that 4499 means spiritual fulfillment – the highest form of human existence.

The Secret Meaning and Symbolism

There is a lot of enthusiasm for new ventures in the heart of the Nine. He is always happy to start a new project.

She is extremely excited and enjoys each subsequent stage of the plan’s implementation.

Of course, her classes related to helping bring her the most joy. In this case, he can turn into a purebred workaholic.

The Way of Life of the 4499 is inseparably connected with opposing injustice.

The 4499 can’t understand how some people can treat their fellow men.

He will never agree to this fact and will fight it with all his might, often subordinating most of his life to this task.

Whatever career he chooses, he will forever remain an injustice hunter in his immediate surroundings.

The number 4499 will always fight for individual freedom. It does not matter whether it is done on a large scale or on a small scale.

It will invariably oppose anything that brings harm or suffering.

Also, all forms of enslavement are mercilessly exterminated by the Nine.

He does not agree to the slave credit banking system, hunger wages or junk contracts.

These are things that, according to the Nine, should not exist in the world at all.

Love and Angel Number 4499

The number 4499 is altruistic, romantic and free-thinking. He is a truly unique person and most people around him clearly see it.

It is no wonder then that the 4499 is often in the center of attention of a large group of friends.

She also likes to spend time with people, so it’s mutual interest.

Numerological 4499 loves new adventures very much, so without hesitation he throws himself into new experiences whenever an opportunity arises.

Of course, this should be related to meeting new people. After all, there can be no real adventures without them.

One thing you need to know about Nine’s personality is that she is extremely honest and has a very humane approach to everything.

He always helps the needy, cares for the weak and stupid … well, he teaches.

He will not leave anyone alone. He can help even his worst enemy if he sees it as an opportunity to change for the better.

The 4499 loves one more thing: romance.

Especially those with a mysterious aftertaste of the forbidden fruit. Getting to know the love secrets of other people, the 4499 is convinced that she has gained control over someone.

And although she is not intoxicated with power, she is extremely satisfied with the awareness of keeping someone in check.

Nine is not very stable in love. It is difficult for her to remain in a stable relationship unless her partner is as independent as she is.

A quiet, routine life is not appealing to the numerological number nine.

She prefers stormy romance and intrigue – they are much more interesting and the 4499 pays more attention to them than to marriage.

Deep down, 4499 is a tireless romantic. He dreams of seducing and seducing his whole life.

She wants love adventures in an exotic country or a mysterious relationship that no one knows about.

The thrill of winning the heart of another person is the highest expression of satisfaction for nine.

Interesting Facts about Number 4499

Extraordinary visions of the future are swirling in Nine’s head. She has many dreams and plans, seeing them as great opportunities.

He predicts wonderful results, although in reality he doesn’t always fully realize everything according to his intentions.

During his life, the 4499 changes his profession many times. It is a bit not adapted to the environment and therefore often falls out of the game for a stable place in a group or company.

The most important thing she should take as a point of honor is learning to adapt to the rest. It is not about giving up her ambitions and beliefs.

It’s enough to temper everything a bit and make it more “digestible” to the public.

It is very important for the 4499 to avoid making promises without coverage. Unfortunately, she has a tendency to do so.

He often withdraws at the last moment from his promises, which has often upset someone.

In the company of the 4499 she is charming and nice. It’s the heart of every party. She is enthusiastic about any kind of fun.

No wonder people love to have her around. Positive thinking of the 4499 is contagious – everyone in her company has a good time.

Unfortunately, the 4499 doesn’t like to tie up. So when relations with a person become too serious, the 4499 quickly disappears.

0 notes

Text

Rig Vedic Period - 1500 BC - 1000 BC

Rig Vedic Period - 1500 BC - 1000 BC

These cities in Harappan Culture. Harappan Culture had declined by 1900 BC. As a result, their economy and administrative system slowly decreased. Several centuries later, Indo-Aryan speakers, Sanskrit, entered the north-west of India through the Indo-Iranian area. In the beginning, they were likely to have travelled in small groups through mountain passes that lie in the northwestern region. The first settlements they made were in the valleys in the north-west, and in the plains that comprise the Punjab. Then, they moved to Indo-Gangetic plains. Since they were mostly livestock-keepers who were mostly seeking pastures. At the time of the 6th century BC they had occupied the entire region area of North India, which was called Aryavarta. The time period between 1500 B.C and 600 B.C could be divided into two periods: the Early Vedic Period or Rig Vedic Period (1500 BC to 1000 BC) in addition to later, the Later Vedic Period (1000 BC to 600 BC).

In the Rig Vedic period, Aryans were mostly in the Indus region of modern-day Pakistan. It is believed that the Rig Veda refers to Saptasindhu also known as"the land with seven rivers. The five river systems of Punjab including Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas and Sutlej along with the Indus and Saraswathi. This period poses trouble for Indian historiography since the earliest historical (as as opposed to mythical] phase of Indian history didn't take position in India. Indian historiography has tends to shift the central point that is the center of Rig Vedic culture out of Pakistan to lands that are which is associated with Modern India and has also tended to alter the timeline of the disappearance in Harappan Culture to suggest a continuity between Harappan Culture and Rig Vedic culture, and a mark with greater antiquity to the more recent period, where the most reliable evidence indicates a gap of almost half a millennium.

The location of origin for people called Aryans is a subject of debate and there are a variety of opinions. Many scholars recognize distinct regions as the ancestral place of residence for the Aryans. These comprise regions like the Arctic area, Germany, Central Asia and the southern part of Russia. Bala Gangadhara Tilak argues that the Aryans originated directly from the Arctic region based on astronomical calculations. But, the theory of southern Russia is more likely and is popular with historians. The Aryans were able to move to different regions in Asia as well as Europe. They migrated to India in the 1500s BC and became called Indo-Aryans. They spoke Indo-Aryan, Sanskrit.

"Veda," as a word, comes taken from the root word "vid" which means to be aware. This means that the word 'Veda' is a reference to superior knowledge. The Vedic literature is comprised of the four Vedas, namely Rig, Yajur, Sama and Atharva. Atharva is the most famous. Rig Veda was the oldest one of all the Vedas, and it contains 1028 hymns. The songs were sung in the praise of gods from all over. It is believed that the Yajur Veda consists of various specifics of rules that must be observed during the moment of sacrifice. In the Sama Veda is set to tune to facilitate singing during the ritual of sacrifice. It is known as"the book that chants,", and the roots of Indian music can be traced through it. It is also known as the Atharva Veda. Atharva Veda contains details of rituals.

In addition to the Vedas and the other sacred texts, including the Brahmanas and the Upanishads and the Aranyakas and the epics Ramayana and Mahabharata. The Brahmanas are the treatises related to sacrificial and prayer. They are also known as the Upanishads are philosophical works that deal with subjects such as being the spirit, eternal nature of the universe, and the mystery of nature. The Aranyakas are also known as forests books and are about mysticism, ritesand rituals and sacrifices. The writer of Ramayana was Valmiki and the author from Mahabharata Was Vedavyas.

The social, political and cultural activities that of Rig Vedic people can be identified from the songs in the Rig Veda. The most fundamental element of the political system was kula, also known as family. Many families came together in accordance with their closeness in order to create a village, or the grama. The leader of the grama was called Gramani. Villages in a group formed an even larger unit known as visu. It was led by vishayapati. The highest level of political organization was called jana , or tribe.

There were many tribes in the Rig Vedic period such as Bharatas, Matsyas, Yadus and Purus. The leader of each kingdom was referred to as rajan or the king. In the Rig Vedic polity was normally monarchical, and lineage was hereditary. The monarch was assisted by purohita , or priest, and senani who was the general in his administration. The two bodies that were popular were known as Sabha and Samiti. Sabha or Samiti. The first appears to have been a council made up of elders, while the latter was an assembly of the entire population.

It was believed that the Rig Vedic culture was patriarchal. The primary element of society was the family, or the graham. Head of family members was referred to as a grahapathi. It was common practice to have monogamy, but polygamy was popular among noble and royal families. The wife was responsible for the household and took part in every major ceremony. Women were offered the same chances as men to develop their intellectual and spiritual growth. Women poets included Apala, Viswavara, Ghosa and Lopamudra in the Rig Vedic period. Women could also attend popular gatherings. The church did not allow children to marriages and the custom of sati was not in place.

Both genders were dressed in upper and lower clothes comprised of wool and cotton. There were a variety of ornaments utilized by both males as well as women. Barley and wheat, milk and its derivatives like curd and ghee, as well as vegetables as well as fruits are the main items of food. Consuming cow's flesh was forbidden because it was considered an animal of the sacred. Horse racing, chariot racing along with music and dance were among the most popular activities. Social divides were not as unbreakable in the Rig Vedic period as it was during the second Vedic period.

They were pastoral settlers and their primary occupation was the rearing of cattle. Their wealth was measured on the basis of their livestock. After they settled permanently within North India they began to engage in agriculture. Through the use and knowledge of iron, they could clear the trees and also bring land under cultivation. Carpentery was a different occupation and the abundance of wood from forest cleared made the trade lucrative. Carpenters built ploughs and chariots. Metal workers created a range of items made of bronze, copper and iron.

Spinning was also a significant occupation and cotton and woolen textiles were used to make them. Goldsmiths were involved in the creation of ornaments. Potters created a variety of vessels used in domestic usage. Trade was another significant business activity, and rivers were utilized as a major means of transportation. Trade was conducted through barter systems. Later gold coins, nishka were used as mediums for exchange in big transactions.

They worshipped the natural forces of fire, earth as well as wind, rain and thunder. They transformed these natural forces as a myriad of gods and revered them. The major Rig Vedic gods were Prithvi (Earth), Agni (Fire), Vayu (Wind), Varuna (Rain) and Indra (Thunder). Indra was most well-known among them in the beginning of the Vedic period. In second place behind Indra is Agni who was considered to be an intermediary between gods and the people. Varuna was believed to be the protector for the nature order. There were female gods as well, such as Aditi as well as Ushas. There were no temples , and no idol worship in the beginning of the Vedic period. Prayers were offered up to gods to seek rewards. Ghee, milk, and grains were offered as sacrifices. A complex ritual was followed in the ceremony of worship.

0 notes

Text

In Progress

Introduction

I hear talking of people

The whole world has gone insane

And all there is left is the fallin' rain

And all there is left is the fallin' rain

All there is left is the fallin' rain- Link Wray

There appears to be an urgency, a strangeness, or an impending state of chaos emerging that many feel they have never felt before. Across this country and around the world, people are feeling it. Thoughts and feelings may vary from one person to another, but the common entry into this frail psychical state adjoins one subject to the rest. A footnote with no ending could be written about the disparity of consciousness that shatters itself into piece upon piece. And another footnote with no ending could be written about why this is.

Technological change has accelerated very quickly. We are now in the future, as opposed to the lukewarm digital age of the late twentieth century. Premonitions of apocalypse have crossed over from religious fundamentalism and into the secular realm. What does apocalypse really mean, though? Doomsday, or the lifting of an illusory veil? Unfortunately, God’s will and the human will to mistakenly re-enact the events of sacred texts might be adjoined after all these years, at least in their cumulative weight on the outcome of the world. But the day opens, and the heart binds itself to the garden of bondage and liberation-

under the burden of often invisible weights,

plants, humans, and other animals

are obstructed from mere sleep.