#normany gif

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Anonymous asked: Big fan of your blog and so impressed with your posts on so many topics. My question is since you’re a Brit living and working in France how would you describe the way the French look at the D Day landings as opposed to the way Americans or you Brits do?

Thank you for your kind words and also your interesting question. It’s not an easy one to answer and I had to think hard about this because obviously I can’t speak in any definitive way but only through my experience of meeting the older generation French as well as military veterans, and just generally listening to those French friends around me, including my French partner and his family.

There is always a gap between how an historical event is actually experienced at the time and how it is then remembered through the passage of time. The feelings evoked from those experiences are more raw at the time and they undoubtedly gets changed the more we move away from that specific time and those who actually experienced it first hand die away. In that sense the French experience of looking at the D Day landings in June 1944 is no different. And when I say no different I mean controversial and disputed amongst themselves.

The first thing to ask who are we talking about?

If we’re talking about the French Resistance then it has to acknowledged that has always been a controversial subject even within France because, to paraphrase John F. Kennedy, ‘Victory has a thousand fathers but defeat is an orphan’. There has been a lot of ink spilled on the bitter rivalries and betrayals within the fragmented groups of opposite ideologies that together made up the resistance.

What gets lost I think is what ordinary people of France thought of the Allied invasion and how in particular the French people who were at the centre of the bitter fighting fared.

For people in the north of France, D-Day meant days, if not weeks, of bombardment prior to the landing. It meant close to 10 weeks of fighting in which their villages changed hands. The advancing Allies, because they had air superiority, were bombing from the sky. There were artillery bombardments as the Allies approach each town. Being liberated meant, for many people, being in the line of fire in very literal ways, and having to calculate if the Germans were driven out, were they going to come back?

There was uncertainty about what the Allies intended, because the French had not been part of the planning in any serious way, and at the very highest levels there was even discussion on the American side of installing an American government of occupation, similar to what they would end up doing in Germany. It didn’t come to much, and the American and Allied troops didn’t actually see themselves as an occupying army, but many of the French saw them as a potentially occupying force. And so there was a lot of uncertainty about what was going to happen.

One of the things that you read in the memoirs of the American and British soldiers who landed in Normandy is that, “The French weren’t as happy to see us as we would have thought. The French were sullen.”

Really, the French were hedging their bets. They had been under German occupation in the north of France since June of 1940, and they had very direct knowledge of the consequences of perceived resistance to German occupation. Openly celebrating, openly assisting the Allies, which many people did do, was a potentially costly act, if things had not gone well.

Once the Allied forces were in France, there was a debate about liberating Paris or bypassing it. Eisenhower eventually let de Gaulle take a division of French forces to liberate the capital, but the French in some ways felt they had traded one occupier for another.

There was a lot of fighting about prostitution, which became rampant, and the American army was unwilling or unable to manage soldiers at the same time the French economy had been devastated by occupation and mass export of resources to Germany.

For women especially, prostitution became one of the ways to survive. The equilibrium, however bad, that had been established during the war collapsed. There was a lot ground-level arguing about soldiers going off with women, in the alleys of northern cities and in people’s back gardens, and there was a lot of anxiety among French men about what that meant. Were the GIs, who were big and healthy and carrying cigarettes and chewing gum and chocolate, going to steal all the French women?

There was a lot of ground-level tension. Stars and Stripes (the U.S. military newspaper) covered the liberation of France with photos of American troops embracing and kissing French women, encouraging some of this tension.

Occasionally there was a photo of a GI giving candy to kids, but mostly coverage is about France as this land of romance and opportunity. There is evidence that some of the GIs took them at their word and after the liberation of Paris, they called Paris ��the Silver Foxhole’ because it was the glittering place full of entertainment, but also brothels, legal and illegal, and other opportunities to meet French women.

There was also an internal power struggle between the external forces of de Gaulle and the Free French and the internal resistance, which was dominated by the French Communist Party.

There was a struggle for power over who was going to control the post-war situation. So there was liberation from the Germans, but in the power vacuum, there was also quite a bit of violence and political tension.

Of all the political groups in France who could really claim to have fought fascism from day one, the only group that could do that unambiguously were the Communists, going back to the 1930s.

Through the war the Communists were the largest and the most effective resistance force, particularly in the unoccupied zone. Part of that is that they were used to being organised in cells and operating clandestinely. Organisationally, they were in a good place to flip very quickly into resistance activity.

So it’s no wonder when the war was over the Communists had plenty of credit in the bank to draw from in seizing power and shaping France. One way they did it was to play up their resistance credentials (and putting under the rug any unsavoury parts). There was a short period of time at the end of the war and shortly afterward when people, especially in Central Europe, thought that communism was a viable alternative to the fascism under which they had been living with the Nazis and to the unstable governments that failed to stop the Nazis from rising to power. The French political Left benefited hugely from that in the post-war years.

For other nationalists and other conservative French people the legacy of German occupation of France and its liberation was decidedly mixed because they themselves were divided in how they responded to the German occupation.

For a conservative patriot and nationalist like Charles de Gaulle, who more than the Communists embodied French resistance, he found the memory of D-Day so painful that he refused to participate in commemorations of the Normandy invasion during his eleven years as president of France. He did not invite heads of government to mark either the 20th anniversary in 1964 or the 25th in 1969. Old French and Allied soldiers saluted; ambassadors laid wreaths but President de Gaulle stayed away.

President Dwight Eisenhower had tried to salve the French hurt in the statement he released for the 10th anniversary in 1954. The statement did not mention the United States or its armed forces. It praised by name three British commanders, three French, one Soviet - no Americans. It credited the victory to “the joint labours of cooperating nations,” and said “it depended for its success upon the skill, determination and self-sacrifice of men from several lands.” You might want to read it as a prophylactic antidote to the boast and bombast likely to fill the air today.

The experience of liberation was a complex thing for almost every country that experienced it from 1943 to 1945, but perhaps nowhere more so than in France. In the American and British imagination of 1944, France exists as a throng of cheering, welcoming faces, as women kissing Tommies and GIs, as a landscape through which Allied tanks and trucks roar on their way to Germany.

Depending on our mood, we romanticise the Resistance or excoriate collaborators - seldom caring to remember how ambiguously collaboration and resistance often blended together, or how often collaborators and resisters were the same people at different phases of the war or even different times of the same day.

To be liberated, first you must be defeated.

Everything about these D-Day anniversaries did remind the French of that humiliating sequence. When de Gaulle landed in Normandy for a one-day visit on 14 June 1944, he traveled back-and-forth across the English Channel in a British warship. De Gaulle’s ability to establish a provisional government depended on the permission of U.S. and British authorities - and so, ultimately, would the even more fraught question whether France would be accepted again as a major ally.

And then there were the other set of nationalists and conservative patriots who ultimately damned themselves: the Vichy regime of Marshal Pétain.

For four years, Vichy France had supplied and aided Germany. Vichy planes had bombed Gibraltar in 1940; Vichy tax collectors had extracted resources to pay the German occupiers. When Italy changed sides in 1943, it was treated as a liberated nation—but it was not accepted as a co-belligerent. France’s post-D-Day status utterly depended on British and American goodwill. For a man like de Gaulle, that dependency rankled.

De Gaulle’s famous speech of 25 August 1944, after the liberation of Paris, starkly reveals the fictions that would restore French pride.

“Paris! Paris outraged! Paris broken! Paris martyred! But Paris liberated! Liberated by itself, liberated by its people with the help of the French armies, with the support and the help of all France, of the France that fights, of the only France, of the real France, of the eternal France! … It will not even be enough that we have, with the help of our dear and admirable Allies, chased him from our home for us to consider ourselves satisfied after what has happened. We want to enter his territory as is fitting, as victors.”

France did enter Germany as a victor. French armies, supplied by the United States, subordinate to U.S. command, were stood up in 1944–45. France was allotted an occupation zone in Germany and awarded a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. (Italy was not even invited to join the United Nations until 1955.) Allied officialdom agreed to believe de Gaulle’s story that the France that fought Nazi Germany was the only ‘real France’.

But everyone understood the story was not true. The French military defeat in 1940 had torn apart social wounds dating back decades and longer.

Conservative and Catholic France reinterpreted the battles of 1940 as a debacle only of the liberal and secular France that had held the upper hand since the founding of the Third Republic in 1871 and especially since the Dreyfus affair that began in 1894. When the reactionary French writer Charles Maurras was sentenced to life imprisonment for collaboration, he supposedly replied, “It’s the revenge of Dreyfus.”

Most French business leaders and civil servants collaborated out of opportunism or necessity. The Germans held hundreds of thousands of captured French soldiers as hostages for years after 1940. But more than a few leading French people, including many right wing intellectuals and reactionary churchmen, collaborated out of a species of conviction.

The loss of the war against Germany enabled such people to launch a much more congenial culture war at home, to purge France of “liberty, equality, and fraternity,” the slogan of 1789, and establish in its place “work, family, fatherland,” the slogan of Vichy. Since 1905, France had been defined as a secular state.

Vichy put an end to all that. The defeat of France by Germany was ideologically reinterpreted as a victory of “deep France” over a shallow liberal metropolitan veneer. Subjugation was reinterpreted by Vichy ideologues as redemption. Enmity was shifted from the occupying Germans to the liberal commercial “Anglo-Saxons.” Vichy propagandists produced cartoons in which Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, and Popeye were depicted dropping bombs on France at the behest of Jewish masters.

Anti-Allied enmity was not difficult to stoke: Allied bombing before 1944 and Allied land forces after 1944 did more damage to French cities than the Germans had in the few weeks of combat in 1940. The port of Le Havre was bombed 132 times from 1940 to 1944. The final raids in September reduced the city centre to rubble, killing 5,000, maiming and rendering homeless tens of thousands more. The modernist cityscape that replaced the former 18th and 19th-century core remains an enduring monument to the price paid by the French people for their liberation.

Vichyite enthusiasm for anti-liberalism opened a strange fluidity in French politics during and after the war. The future leader of French socialism, François Mitterrand, began his political career on the far right of French politics and worked until 1943 as a civil servant in the Vichy government. But as a socialist president after 1981, Mitterrand would raise minimum wages, cut the workweek to 39 hours, nationalise some financial institutions, and end the death penalty. He would even do what de Gaulle could never stomach: celebrate the D-Day anniversary. It was Mitterrand who decided to invite Ronald Reagan to Normandy in 1984.

The legacy of Vichy remains a sore wound and no one really wants to touch it too much. Within families, unless they have a history of someone who was in the resistance, no one really talks about the war. Time has emotionally detached the French somewhat from past painful memories of occupation and what went on under occupation. I personally believe we in Britain - who milk the fact that we stood alone…and only because we had a stretch of water and the might of the German war machine - and those in the US - who were oceans apart - shouldn’t judge the French as we were never under occupation.

Being under occupation brings out the worst in people as much as it brings out the best in terms of heroic defiance and resistance. But also for many it just brings resigned acceptance of how things are and everyone just put their head down to just survive.

Having lived through the tremendous instability of the interwar period and having lived through the First World War, which was living memory to many adults in Europe, the calculus looks really, really different than it did from the United States.

In having the privilege to have met American veterans of the Second World War, I think it would be fair to say that D-Day is very much a major touchstone for the American identity. A non-professional army of factory workers and schoolteachers got into uniform, they went to a place they didn’t know about and they fought the ‘bad guys’, and, using their skills and their talents and their cleverness, they overcame a much more powerful, ‘demonic’ enemy with insolent bravura and sheer guts.

When Americans choose to remember this heroic history, they do so from the privilege of an easier geography. As time has separated Americans from the Second World War - for the French and even the British - there is a feeling that American memories have become more triumphalist and self-aggrandising the further we move away from the Greatest Generation (who were heroic, stoic, uncomplaining, and just sought to get on with their lives once they got back home).

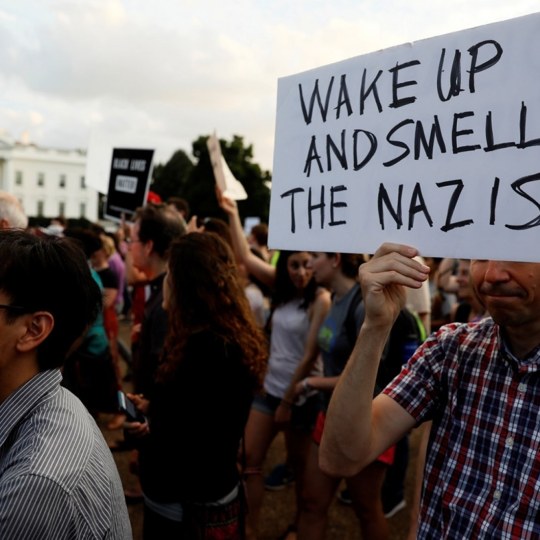

To many outside observers the heroics of those brave soldiers landing in Normandy on that fateful day has been held hostage to the vicissitudes of whatever ongoing culture war is taking place between Americans. Only Americans use the word ‘Nazi’ and throw it around at other people like it was confetti. Anyone and everyone can be accused of being a Nazi these days. So often is that word thrown around that it’s lost all meaning of its true import. The best way to end a heated argument is to accuse one’s opponent of being a Nazi.

History is always held hostage to the present. Take the Donald Trump. I don’t like him and on my blog I made plenty of posts disparaging him but I don’t think I ever painted him as a Nazi or a fascist (another over used and interchangeable word). Many of the left became hysterical at his election to the presidency. The rise of Donald Trump sparked many analogies to the politics of the 1930s which was always a historically illiterate analogy as well as a very dumb one.

Unlike Europe, contemporary American mentalities are not formed by vivid personal memories of the mass bloody slaughter of 1914-18. Current Americans have experienced nothing like the Great Depression or the civil unrest that piled bodies in the streets of interwar Berlin and Paris. Present day Americans are not haunted by the possibility that domestic communists might seize power and property in a revolutionary spasm. It’s never going to be 1933 again.

But what does remain from the past are the same human impulses for domination and control, the same way both fascists and communists thrived upon during a time of societal upheaval. Authoritarian impulses behind the curtailment of free speech, honest and critical discussions around gender ideology and indoctrination of school children, the illiberalism of many university campuses pushing diversity, inclusion, and equity indoctrination, all show they have been powerful forces for extremists to amplify in the unsettled present moment.

For the British, we tell ourselves a different story.

It is one of those intriguing coincidences of historical time that this week marked the anniversary of the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) from Dunkirk (June 4) and the anniversary of the D-Day landings (June 6).

Separated by four years and markedly different in terms of their ‘place’ in the Second World War – Dunkirk at the very ‘beginning’ and D-Day commencing the last act. But the two events have nonetheless become closely connected in our cultural memory – a connection that can be traced back to the war itself.

The evacuation of the British army from Dunkirk (and other French ports) in May-June 1940 was a military catastrophe of the highest order. This force had been despatched to France in the autumn as a demonstration of British support for their French ally, and for many of those in command it was seen as the successor to that valiant predecessor, the BEF of 1914.

Indeed, just like this predecessor, the army’s job was to support Belgian and French counterparts in the event of German attack, and many of its senior officers – all veterans of the First World War – likely anticipated a similarly lengthy residence across the channel. But it was not to be.

Aside from occasional moments of tactical success – notably the Battle of Arras – this 1940 ‘BEF’ eventually succumbed to the sheer speed of the German Blitzkrieg attack, which commenced in early May. Cut off in northern France and increasingly unable to affect the outcome of the Battle of France, a large-scale evacuation was commenced in late May. This evacuation - Operation Dynamo - would eventually return to Britain over 300,000 British, French, Belgian, Polish, and Czech troops.

For Winston Churchill, this was a “colossal military disaster” that he nonetheless quickly sought to convert into a “miracle of deliverance” demonstrative of British resilience and fortitude. The role of the now famous ‘little ships’ – the yachts, lifeboats, fishing trawlers and pleasure steamers – in bringing the troops back to Blighty received particular attention. Here was an example of ordinary Britons rallying to the cause while demonstrating their characteristic mastery of sail and sea. Meanwhile, Churchill readied the nation to “fight on the beaches” and to “never surrender”.

Fighting on the beaches would remain a preoccupation of Churchill’s for the remainder of the war. Indeed, soon after the British army was brought home from the beaches of France, Churchill was already pondering ways for it to return, and by 1941 he had appointed Commodore Lord Louis Mountbatten – his Chief Advisor for Combined Operations (that is, for amphibious assaults, long a favoured interest of the prime minister). This was the origins of the organisation which in due course would develop into General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s ‘Overlord’ command – the organisation which planned and commanded the Allied Invasion of Normandy in June 1944. In this sense, the very idea of ‘D-Day’ might be said to have been born on the beaches of Dunkirk.

This connection between the 1940 evacuation and the 1944 invasion similarly shaped how the British media framed the D-Day assault. British Movietone News for instance reported the landings in Normandy as “the story of how four years after Dunkirk…Britain came back” whilst The Times declared that “four years ago…the tide of war had flooded from the east into the French channel ports”, but now “the tide has turned”.

Once the war was won, such a connection between the ‘retreat’ and the ‘return’ only consolidated itself further. Various post-war histories of D-Day often opened with a chapter on Dunkirk, whilst the first feature film to focus on the Allied landings (D-Day: Sixth of June, 1956) likewise organised its narrative around this dualism, connecting via certain characters the despair of Dunkirk with the triumph of Normandy.

Ever since, this has remained a powerful dynamic shaping British memory of the war, with D-Day frequently defined by press and politicians - especially in the 1950s and 1960s - as the redemption of Dunkirk. Put differently, in our popular memory, D-Day performs a vital function for it asserts that what happened at Dunkirk was not, ultimately, a ‘defeat’ but instead a setback on the road to victory.

Separated by four years, and profoundly different in how they were lived and experienced, the connection in time and also in our memory between Dunkirk and D-Day hints at a persistent binary in our relationship with those across the channel. Put another way, our history is marked by various ‘retreats’ from Europe only to be followed later by a ‘return’. For me at least, this is the meaning - and hope - I shall choose to see this week as I reflect upon the anniversaries of 1940 and of 1944.

There is nothing wrong in telling the story that way, but it compresses a lot of complexity. What I think is regrettable is that we miss the rest of the year. Because from June of 1944 to May of 1945 is a very long, hard year, and that is when most of the casualties in Europe will be lost.

Getting back to the French I would say that when the French step back and think about the bigger picture from the actual events on D day in June 1944, it becomes ambiguous very quickly, because their Allied British and American liberators also brought destruction but freedom brought conflict and reprisal amongst themselves. Everywhere there were difficult moral and political questions about collaboration and behaviour during the occupation that were brought to the surface once the Germans were gone. It is a much more complex kind of story.

But you find it is much more complex when you dig into the British and American side as well. The mythologies never capture actual things that well. We hold hostage the genuine herosim of those brave soldiers landing on the bloody beaches of Normandy and those courageous ordinary French people resisting the Germans to the present. That’s why there is one thing that every historian says (or should say) at least six times a day: “Well, it was more complicated than that.” That applies equally well here.

Thanks for your question.

#question#ask#D Day#Normany#second world war#france#french#charles de gaulle#britian#america#history#war#legacy#french resistance#past#present#past vs present#remembrance#society#culture

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello, Hotline 1:59. Yes, here to satisfy your deepest, darkest, wildest desires. No rules, no restrictions. Straight dopamine.

DOPAMINE - Normani June 14, 2024

#normani#normaniedit#userbbelcher#chewieblog#dailywomen#dailymusicians#userladiesblr#femaledaily#dailycelebs#useroptional#usersource#cinemapix#fyeah5h#femalestunning#*#a: dopamine#1k*

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

PERSONAL Khalid & Normani

#normani#normaniedit#dailywomen#chewieblog#userbbelcher#dailymusicians#dailymusicqueens#userpcultures#femalestunning#usermilla#tuserdee#tusercourtney#*mine#*gif

339 notes

·

View notes

Text

NORMANI Dopamine (First Dose)

#Normani#Normaniedit#Celebs#Celebsedit#Flawlessbeautyqueens#Breathtakingqueens#Daily-women#Glamoroussource#Wonderfulwomendaily#Femalestunning#Femaledaily#Femalesource#Thequeensofbeauty#Dailymusicians#Musicgifs#*gifs#*

742 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sweet just like candy

#dwomenedit#normani#normaniedit#celebedit#femaledaily#dailymusicians#dailymusicqueens#wonderfulwoc#dailywoc#ladiesblr#userbbelcher#rnbsource#by milla

710 notes

·

View notes

Text

NORMANI

DOPAMINE (First Dose)

841 notes

·

View notes

Text

NORMANI for ELLE

#normani#normaniedit#woc#wocedit#dailywoc#wonderfulwoc#userwocs#userfyp#userpcultures#pocedit#pocsource#pocpopculture#womenedit#femalegifsource#dailywomen#femaledaily#userladiesblr#userdre#breathtakingqueens#usersage#flawlesscelebs#usersource#useroptional#wifesource#usercroft#userbblecher#usersugar#usermandie#dailymusicians#dailymusicqueens

892 notes

·

View notes

Text

— Do I just talk too much?

#normani#normaniedit#celebedit#dailywomen#dailymusicians#dailymusicqueens#wonderfulwoc#dailywoc#ladiesblr#userbbelcher#userbru#femaledaily#rnbsource#mine#she looks so good omg

919 notes

·

View notes

Text

cнℓöε • ɴᴏʀᴍᴀɴɪ • 𝔸𝕪𝕣𝕒 𝕊𝕥𝕒𝕣𝕣

ᴷʰᵃˡᶦᵈ

#chlöe#chloe bailey#normani#ayra starr#khalid#cbaileyedit#normaniedit#ayrastarredit#khalidedit#2024#music video#mv#black musicians#my post#dailymusicians#dailymusicqueens#dailywomen#dailymusicsource#popularcultures#pocedit#pocpopculture#pocsource#femalegifsource#wocedit#wocdaily#wocsource#usermusic#usermusicdaily#userladiesblr#xosiren

280 notes

·

View notes

Text

(x)

#normani#normaniedit#celebedit#usermusic#userpcultures#femaledaily#dailywomen#blogmusicdaily#userladiesblr#dailymusicians#femalestunning#userbbelcher#photoshoot#*#2024#userlaro#user.tee#userjessica#janielook#userrin#userrobin#userhallie#tusermona#useralien#useralison

429 notes

·

View notes

Text

Normani for her debut album ‘DOPAMINE’

#mine#normani#normaniedit#normani kordei#popularcultures#blogmusicdaily#dailywoc#dailywomen#userwocs#rnbsource#wocdaily#femalestunning#femaledaily#glamoroussource#wonderfulwoc#dailymusicqueens#black women#pocsource#dopamine

981 notes

·

View notes

Text

Normani - Dopamine (First Dose)

#normani#normaniedit#dailywomen#flawlessbeautyqueens#dopamine#music video#tw flashing#tw graphic#my gifs#she is so amazing

436 notes

·

View notes

Text

Healthy Black Women Friendship.

The beauty… I love this duo.

🏷️ Normani x Ryan Destiny

#normani#ryan destiny#black women in luxury#classy black women#black women in femininity#feminine energy#goddess energy

789 notes

·

View notes

Text

♡ NORMANI harper's bazaar

#normani#normani gifs#normaniedit#dailywomen#femaledaily#femalestunning#flawlesscelebs#femalegifsource#wifesource#flawlessbeautyqueens#dailycelebs#dailypoc#dailywoc#pocedit#wocedit#popularcultures#userpcultures#fifthsource#usercherry#*

571 notes

·

View notes

Text

Smosh Fam at the Spotify Wrapped 2024 Party

#smosh#ian hecox#anthony padilla#angela giarratana#arasha lalani#tommy bowe#kiana parker#emily jacobson#bailey petracek#normani#ke$ha#spotify#spotify wrapped#smgifs

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

NORMANI

593 notes

·

View notes