#no one who denies their white and Western privilege or their settler privilege is anti Zionist

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Aryan supremacy was imported to the South Asian subcontinent by the British and it's now exactly as bad here as white supremacy is in the West. Buddhism and Hinduism were birthed in the Indus Valley civilization; therefore Buddhists and North Indian Hindus consider ourselves culturally Aryan.

My Buddhist girls school was established by a German woman in 1893 who was a Theosophist (one of the Orientalist schools of esotericism that invented race theories and Aryan supremacist ideology) and my school tie has a swastika on it. We didn't connect it with Nazi imagery because we don't have Jews in Sri Lanka (yes, we really don't) and it was very difficult for us to even understand what antisemitism was, because we didn't understand why white Europeans would go after other white Europeans. (This is a fair assumption because those six million counted were Europeans, and Israel actively erased the Holocaust victims in the MENA just like the Soviets erased Holocaust victims in the USSR. I didn't even realize Black and brown Jews existed until I got home internet access in the mid-2000s). However, the British did impose the same antisemitic tropes in Europe onto the Muslim Moors. Like, that's how I finally wrapped my head around antisemitism, because I looked through all the conspiracy theories and was like, "wait...this is exactly what they say about Muslims here...wtf".

And that's how it works here— Aryan supremacy is responsible for the genocide of Tamils and persecution of Muslims in Sri Lanka, the ethnic cleansing of Muslims and discrimination and disenfranchisement Dravidians by the Hindutvas in India's BJP government, the genocide of Rohingyas in Myanmar etc. So while the swastika itself doesn't necessarily invoke Aryan supremacy in South Asia, you also can't divorce the swastika from the Aryan supremacy that's tearing South Asia apart right now. Particularly considering that Aryan supremacy gained vogue among people in the British colonies during WW2 because as far as we were concerned, Japan and Germany were fighting the people colonizing, starving and genociding us. Atrocities that the West used its role in the Holocaust to suppress and whitewash.

Despite the fact that we South Asians don't have any systemic power over Jewish people in the West, we also wouldn't use swastikas in places where we interacted with them. It's just human decency to acknowledge when symbols important to you have been corrupted and created lasting trauma along ethnic lines. I know that the Buddhist flag is a trauma trigger for Sri Lankan Tamils and Muslims; Buddhist values would have us prioritize validating and healing that more than advocating for the right of Buddhists to use the flag (not that SinBuds are known for doing that— another example of the difference between religious doctrine and its adherents). I hope the Jewish community will be able to do extend that understanding and sympathy to Palestinians who have been traumatized under the Star of David for 75 years, as well as for the Muslims who now will not be able to see it without remembering Gaza. Healing requires validation of hurt and the willingness to prioritise the well-being of victims over one's own rights.

israel will do gruesome shit like this all the time while liberals will disqualify the entire palestine movement as antisemitic and not worth supporting bc they saw one video of a palestinian call the people bombing and invading them jews instead of zionists

#basically don't be like Sinhalese Buddhist turds whose idea of leftism#is arguing with Tamils and Muslims#how Buddhist and Sinhalese imagery shouldn't invoke 75 years of war crimes and ethnic cleansing#my hatred for flags stems from the fact that I can't see either one without remembering the Tamils burned alive under them#a lot of my anger at 'anti Zionist' white Jews right now is the fact that a lot of them are acting like 'antiracist' SinBuds do#if you want to distance yourself from the people who committed crimes in your name#you need first of all own that they WERE committed in your name#as well as the intersection between religious zealotry and the race privilege that allowed it to be weaponized#also reminder that Black and brown Jews were the secondary victims of Israel#their Arab histories and backgrounds were erased by Israel#and they were expelled from their countries BECAUSE of Israel#no one who denies their white and Western privilege or their settler privilege is anti Zionist#they simply don't like having to see the human cost of their ideology#free palestine#knee of huss

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Non-paywall version here

Peace in the israel-palestine conflict had already been difficult to achieve before Hamas’s barbarous October 7 attack and Israel’s military response. Now it seems almost impossible, but its essence is clearer than ever: Ultimately, a negotiation to establish a safe Israel beside a safe Palestinian state. Whatever the enormous complexities and challenges of bringing about this future, one truth should be obvious among decent people: killing 1,400 people and kidnapping more than 200, including scores of civilians, was deeply wrong. The Hamas attack resembled a medieval Mongol raid for slaughter and human trophies—except it was recorded in real time and published to social media. Yet since October 7, Western academics, students, artists, and activists have denied, excused, or even celebrated the murders by a terrorist sect that proclaims an anti-Jewish genocidal program. Some of this is happening out in the open, some behind the masks of humanitarianism and justice, and some in code, most famously “from the river to the sea,” a chilling phrase that implicitly endorses the killing or deportation of the 9 million Israelis. It seems odd that one has to say: Killing civilians, old people, even babies, is always wrong. But today say it one must. How can educated people justify such callousness and embrace such inhumanity? All sorts of things are at play here, but much of the justification for killing civilians is based on a fashionable ideology, “decolonization,” which, taken at face value, rules out the negotiation of two states—the only real solution to this century of conflict—and is as dangerous as it is false.

I always wondered about the leftist intellectuals who supported Stalin, and those aristocratic sympathizers and peace activists who excused Hitler. Today’s Hamas apologists and atrocity-deniers, with their robotic denunciations of “settler-colonialism,” belong to the same tradition but worse: They have abundant evidence of the slaughter of old people, teenagers, and children, but unlike those fools of the 1930s, who slowly came around to the truth, they have not changed their views an iota. The lack of decency and respect for human life is astonishing: Almost instantly after the Hamas attack, a legion of people emerged who downplayed the slaughter, or denied actual atrocities had even happened, as if Hamas had just carried out a traditional military operation against soldiers. October 7 deniers, like Holocaust deniers, exist in an especially dark place.

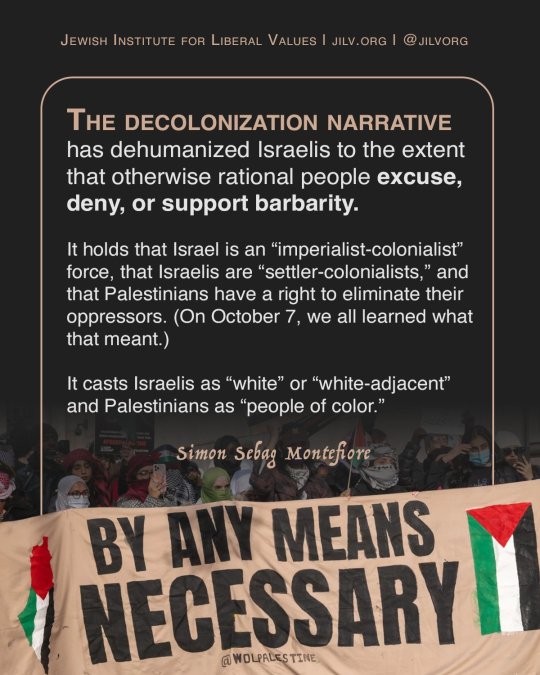

The decolonization narrative has dehumanized Israelis to the extent that otherwise rational people excuse, deny, or support barbarity. It holds that Israel is an “imperialist-colonialist” force, that Israelis are “settler-colonialists,” and that Palestinians have a right to eliminate their oppressors. (On October 7, we all learned what that meant.) It casts Israelis as “white” or “white-adjacent” and Palestinians as “people of color.”

This ideology, powerful in the academy but long overdue for serious challenge, is a toxic, historically nonsensical mix of Marxist theory, Soviet propaganda, and traditional anti-Semitism from the Middle Ages and the 19th century. But its current engine is the new identity analysis, which sees history through a concept of race that derives from the American experience. The argument is that it is almost impossible for the “oppressed” to be themselves racist, just as it is impossible for an “oppressor” to be the subject of racism. Jews therefore cannot suffer racism, because they are regarded as “white” and “privileged”; although they cannot be victims, they can and do exploit other, less privileged people, in the West through the sins of “exploitative capitalism” and in the Middle East through “colonialism.”

This leftist analysis, with its hierarchy of oppressed identities—and intimidating jargon, a clue to its lack of factual rigor—has in many parts of the academy and media replaced traditional universalist leftist values, including internationalist standards of decency and respect for human life and the safety of innocent civilians. When this clumsy analysis collides with the realities of the Middle East, it loses all touch with historical facts.

Indeed, it requires an astonishing leap of ahistorical delusion to disregard the record of anti-Jewish racism over the two millennia since the fall of the Judean Temple in 70 C.E. After all, the October 7 massacre ranks with the medieval mass killings of Jews in Christian and Islamic societies, the Khmelnytsky massacres of 1640s Ukraine, Russian pogroms from 1881 to 1920—and the Holocaust. Even the Holocaust is now sometimes misconstrued—as the actor Whoopi Goldberg notoriously did—as being “not about race,” an approach as ignorant as it is repulsive.

Contrary to the decolonizing narrative, Gaza is not technically occupied by Israel—not in the usual sense of soldiers on the ground. Israel evacuated the Strip in 2005, removing its settlements. In 2007, Hamas seized power, killing its Fatah rivals in a short civil war. Hamas set up a one-party state that crushes Palestinian opposition within its territory, bans same-sex relationships, represses women, and openly espouses the killing of all Jews.

Very strange company for leftists.

Of course, some protesters chanting “from the river to the sea” may have no idea what they’re calling for; they are ignorant and believe that they are simply endorsing “freedom.” Others deny that they are pro-Hamas, insisting that they are simply pro-Palestinian—but feel the need to cast Hamas’s massacre as an understandable response to Israeli-Jewish “colonial” oppression. Yet others are malign deniers who seek the death of Israeli civilians.

The toxicity of this ideology is now clear. Once-respectable intellectuals have shamelessly debated whether 40 babies were dismembered or some smaller number merely had their throats cut or were burned alive. Students now regularly tear down posters of children held as Hamas hostages. It is hard to understand such heartless inhumanity. Our definition of a hate crime is constantly expanding, but if this is not a hate crime, what is? What is happening in our societies? Something has gone wrong.

In a further racist twist, Jews are now accused of the very crimes they themselves have suffered. Hence the constant claim of a “genocide” when no genocide has taken place or been intended. Israel, with Egypt, has imposed a blockade on Gaza since Hamas took over, and has periodically bombarded the Strip in retaliation for regular rocket attacks. After more than 4,000 rockets were fired by Hamas and its allies into Israel, the 2014 Gaza War resulted in more than 2,000 Palestinian deaths. More than 7,000 Palestinians, including many children, have died so far in this war, according to Hamas. This is a tragedy—but this is not a genocide, a word that has now been so devalued by its metaphorical abuse that it has become meaningless.

I should also say that Israeli rule of the Occupied Territories of the West Bank is different and, to my mind, unacceptable, unsustainable, and unjust. The Palestinians in the West Bank have endured a harsh, unjust, and oppressive occupation since 1967. Settlers under the disgraceful Netanyahu government have harassed and persecuted Palestinians in the West Bank: 146 Palestinians in the West Bank and East Jerusalem were killed in 2022 and at least 153 in 2023 before the Hamas attack, and more than 90 since. Again: This is appalling and unacceptable, but not genocide.

Although there is a strong instinct to make this a Holocaust-mirroring “genocide,” it is not: The Palestinians suffer from many things, including military occupation; settler intimidation and violence; corrupt Palestinian political leadership; callous neglect by their brethren in more than 20 Arab states; the rejection by Yasser Arafat, the late Palestinian leader, of compromise plans that would have seen the creation of an independent Palestinian state; and so on. None of this constitutes genocide, or anything like genocide. The Israeli goal in Gaza—for practical reasons, among others—is to minimize the number of Palestinian civilians killed. Hamas and like-minded organizations have made it abundantly clear over the years that maximizing the number of Palestinian casualties is in their strategic interest. (Put aside all of this and consider: The world Jewish population is still smaller than it was in 1939, because of the damage done by the Nazis. The Palestinian population has grown, and continues to grow. Demographic shrinkage is one obvious marker of genocide. In total, roughly 120,000 Arabs and Jews have been killed in the conflict over Palestine and Israel since 1860. By contrast, at least 500,000 people, mainly civilians, have been killed in the Syrian civil war since it began in 2011.)

If the ideology of decolonization, taught in our universities as a theory of history and shouted in our streets as self-evidently righteous, badly misconstrues the present reality, does it reflect the history of Israel as it claims to do? It does not. Indeed, it does not accurately describe either the foundation of Israel or the tragedy of the Palestinians.

According to the decolonizers, Israel is and always has been an illegitimate freak-state because it was fostered by the British empire and because some of its founders were European-born Jews.

In this narrative, Israel is tainted by imperial Britain’s broken promise to deliver Arab independence, and its kept promise to support a “national home for the Jewish people,” in the language of the 1917 Balfour Declaration. But the supposed promise to Arabs was in fact an ambiguous 1915 agreement with Sharif Hussein of Mecca, who wanted his Hashemite family to rule the entire region. In part, he did not receive this new empire because his family had much less regional support than he claimed. Nonetheless, ultimately Britain delivered three kingdoms—Iraq, Jordan, and Hejaz—to the family.

The imperial powers—Britain and France—made all sorts of promises to different peoples, and then put their own interests first. Those promises to the Jews and the Arabs during World War I were typical. Afterward, similar promises were made to the Kurds, the Armenians, and others, none of which came to fruition. But the central narrative that Britain betrayed the Arab promise and backed the Jewish one is incomplete. In the 1930s, Britain turned against Zionism, and from 1937 to 1939 moved toward an Arab state with no Jewish one at all. It was an armed Jewish revolt, from 1945 to 1948 against imperial Britain, that delivered the state.

Israel exists thanks to this revolt, and to international law and cooperation, something leftists once believed in. The idea of a Jewish “homeland” was proposed in three declarations by Britain (signed by Balfour), France, and the United States, then promulgated in a July 1922 resolution by the League of Nations that created the British “mandates” over Palestine and Iraq that matched French “mandates” over Syria and Lebanon. In 1947, the United Nations devised the partition of the British mandate of Palestine into two states, Arab and Jewish.

The carving of such states out of these mandates was not exceptional, either. At the end of World War II, France granted independence to Syria and Lebanon, newly conceived nation-states. Britain created Iraq and Jordan in a similar way. Imperial powers designed most of the countries in the region, except Egypt.

Nor was the imperial promise of separate homelands for different ethnicities or sects unique. The French had promised independent states for the Druze, Alawites, Sunnis, and Maronites but in the end combined them into Syria and Lebanon. All of these states had been “vilayets” and “sanjaks” (provinces) of the Turkish Ottoman empire, ruled from Constantinople, from 1517 until 1918.

The concept of “partition” is, in the decolonization narrative, regarded as a wicked imperial trick. But it was entirely normal in the creation of 20th-century nation-states, which were typically fashioned out of fallen empires. And sadly, the creation of nation-states was frequently marked by population swaps, huge refugee migrations, ethnic violence, and full-scale wars. Think of the Greco-Turkish war of 1921–22 or the partition of India in 1947. In this sense, Israel-Palestine was typical.

At the heart of decolonization ideology is the categorization of all Israelis, historic and present, as “colonists.” This is simply wrong. Most Israelis are descended from people who migrated to the Holy Land from 1881 to 1949. They were not completely new to the region. The Jewish people ruled Judean kingdoms and prayed in the Jerusalem Temple for a thousand years, then were ever present there in smaller numbers for the next 2,000 years. In other words, Jews are indigenous in the Holy Land, and if one believes in the return of exiled people to their homeland, then the return of the Jews is exactly that. Even those who deny this history or regard it as irrelevant to modern times must acknowledge that Israel is now the home and only home of 9 million Israelis who have lived there for four, five, six generations.

Most migrants to, say, the United Kingdom or the United States are regarded as British or American within a lifetime. Politics in both countries is filled with prominent leaders—Suella Braverman and David Lammy, Kamala Harris and Nikki Haley—whose parents or grandparents migrated from India, West Africa, or South America. No one would describe them as “settlers.” Yet Israeli families resident in Israel for a century are designated as “settler-colonists” ripe for murder and mutilation. And contrary to Hamas apologists, the ethnicity of perpetrators or victims never justifies atrocities. They would be atrocious anywhere, committed by anyone with any history. It is dismaying that it is often self-declared “anti-racists” who are now advocating exactly this murder by ethnicity.

Those on the left believe migrants who escape from persecution should be welcomed and allowed to build their lives elsewhere. Almost all of the ancestors of today’s Israelis escaped persecution.

If the “settler-colonist” narrative is not true, it is true that the conflict is the result of the brutal rivalry and battle for land between two ethnic groups, both with rightful claims to live there. As more Jews moved to the region, the Palestinian Arabs, who had lived there for centuries and were the clear majority, felt threatened by these immigrants. The Palestinian claim to the land is not in doubt, nor is the authenticity of their history, nor their legitimate claim to their own state. But initially the Jewish migrants did not aspire to a state, merely to live and farm in the vague “homeland.” In 1918, the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann met the Hashemite Prince Faisal Bin Hussein to discuss the Jews living under his rule as king of greater Syria. The conflict today was not inevitable. It became so as the communities refused to share and coexist, and then resorted to arms.

Even more preposterous than the “colonizer” label is the “whiteness” trope that is key to the decolonization ideology. Again: simply wrong. Israel has a large community of Ethiopian Jews, and about half of all Israelis—that is, about 5 million people—are Mizrahi, the descendants of Jews from Arab and Persian lands, people of the Middle East. They are neither “settlers” nor “colonialists” nor “white” Europeans at all but inhabitants of Baghdad and Cairo and Beirut for many centuries, even millennia, who were driven out after 1948.

A word about that year, 1948, the year of Israel’s War of Independence and the Palestinian Nakba (“Catastrophe”), which in decolonization discourse amounted to ethnic cleansing. There was indeed intense ethnic violence on both sides when Arab states invaded the territory and, together with Palestinian militias, tried to stop the creation of a Jewish state. They failed; what they ultimately stopped was the creation of a Palestinian state, as intended by the United Nations. The Arab side sought the killing or expulsion of the entire Jewish community—in precisely the murderous ways we saw on October 7. And in the areas the Arab side did capture, such as East Jerusalem, every Jew was expelled.

In this brutal war, Israelis did indeed drive some Palestinians from their homes; others fled the fighting; yet others stayed and are now Israeli Arabs who have the vote in the Israeli democracy. (Some 25 percent of today’s Israelis are Arabs and Druze.) About 700,000 Palestinians lost their homes. That is an enormous figure and a historic tragedy. Starting in 1948, some 900,000 Jews lost their homes in Islamic countries and most of them moved to Israel. These events are not directly comparable, and I don’t mean to propose a competition in tragedy or hierarchy of victimhood. But the past is a lot more complicated than the decolonizers would have you believe.

Out of this imbroglio, one state emerged, Israel, and one did not, Palestine. Its formation is long overdue.

It is bizarre that a small state in the Middle East attracts so much passionate attention in the West that students run through California schools shouting “Free Palestine.” But the Holy Land has an exceptional place in Western history. It is embedded in our cultural consciousness, thanks to the Hebrew and Christian Bibles, the story of Judaism, the foundation of Christianity, the Quran and the creation of Islam, and the Crusades that together have made Westerners feel involved in its destiny. The British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, the real architect of the Balfour Declaration, used to say that the names of places in Palestine “were more familiar to me than those on the Western Front.” This special affinity with the Holy Land initially worked in favor of the Jewish return, but lately it has worked against Israel. Westerners eager to expose the crimes of Euro-American imperialism but unable to offer a remedy have, often without real knowledge of the actual history, coalesced around Israel and Palestine as the world’s most vivid example of imperialist injustice.

The open world of liberal democracies—or the West, as it used to be called—is today polarized by paralyzed politics, petty but vicious cultural feuds about identity and gender, and guilt about historical successes and sins, a guilt that is bizarrely atoned for by showing sympathy for, even attraction to, enemies of our democratic values. In this scenario, Western democracies are always bad actors, hypocritical and neo-imperialist, while foreign autocracies or terror sects such as Hamas are enemies of imperialism and therefore sincere forces for good. In this topsy-turvy scenario, Israel is a living metaphor and penance for the sins of the West. The result is the intense scrutiny of Israel and the way it is judged, using standards rarely attained by any nation at war, including the United States.

But the decolonizing narrative is much worse than a study in double standards; it dehumanizes an entire nation and excuses, even celebrates, the murder of innocent civilians. As these past two weeks have shown, decolonization is now the authorized version of history in many of our schools and supposedly humanitarian institutions, and among artists and intellectuals. It is presented as history, but it is actually a caricature, zombie history with its arsenal of jargon—the sign of a coercive ideology, as Foucault argued—and its authoritarian narrative of villains and victims. And it only stands up in a landscape in which much of the real history is suppressed and in which all Western democracies are bad-faith actors. Although it lacks the sophistication of Marxist dialectic, its self-righteous moral certainty imposes a moral framework on a complex, intractable situation, which some may find consoling. Whenever you read a book or an article and it uses the phrase “settler-colonialist,” you are dealing with ideological polemic, not history.

Ultimately, this zombie narrative is a moral and political cul-de-sac that leads to slaughter and stalemate. That is no surprise, because it is based on sham history: “An invented past can never be used,” wrote James Baldwin. “It cracks and crumbles under the pressures of life like clay.”

Even when the word decolonization does not appear, this ideology is embedded in partisan media coverage of the conflict and suffuses recent condemnations of Israel. The student glee in response to the slaughter at Harvard, the University of Virginia, and other universities; the support for Hamas amongst artists and actors, along with the weaselly equivocations by leaders at some of America’s most famous research institutions, have displayed a shocking lack of morality, humanity, and basic decency.

One repellent example was an open letter signed by thousands of artists, including famous British actors such as Tilda Swinton and Steve Coogan. It warned against imminent Israel war crimes and totally ignored the casus belli: the slaughter of 1,400 people.

The journalist Deborah Ross wrote in a powerful Times of London article that she was “utterly, utterly floored” that the letter contained “no mention of Hamas” and no mention of the “kidnapping and murder of babies, children, grandparents, young people dancing peacefully at a peace festival. The lack of basic compassion and humanity, that’s what was so unbelievably flooring. Is it so difficult? To support and feel for Palestinian citizens … while also acknowledging the indisputable horror of the Hamas attacks?” Then she asked this thespian parade of moral nullities: “What does it solve, a letter like that? And why would anyone sign it?”

The Israel-Palestine conflict is desperately difficult to solve, and decolonization rhetoric makes even less likely the negotiated compromise that is the only way out.

Since its founding in 1987, Hamas has used the murder of civilians to spoil any chance of a two-state solution. In 1993, its suicide bombings of Israeli civilians were designed to destroy the two-state Olso Accords that recognized Israel and Palestine. This month, the Hamas terrorists unleashed their slaughter in part to undermine a peace with Saudi Arabia that would have improved Palestinian politics and standard of life, and reinvigorated Hamas’s sclerotic rival, the Palestinian Authority. In part, they served Iran to prevent the empowering of Saudi Arabia, and their atrocities were of course a spectacular trap to provoke Israeli overreaction. They are most probably getting their wish, but to do this they are cynically exploiting innocent Palestinian people as a sacrifice to political means, a second crime against civilians. In the same way, the decolonization ideology, with its denial of Israel’s right to exist and its people’s right to live safely, makes a Palestinian state less likely if not impossible.

The problem in our countries is easier to fix: Civic society and the shocked majority should now assert themselves. The radical follies of students should not alarm us overmuch; students are always thrilled by revolutionary extremes. But the indecent celebrations in London, Paris, and New York City, and the clear reluctance among leaders at major universities to condemn the killings, have exposed the cost of neglecting this issue and letting “decolonization” colonize our academy.

Parents and students can move to universities that are not led by equivocators and patrolled by deniers and ghouls; donors can withdraw their generosity en masse, and that is starting in the United States. Philanthropists can pull the funding of humanitarian foundations led by people who support war crimes against humanity (against victims selected by race). Audiences can easily decide not to watch films starring actors who ignore the killing of children; studios do not have to hire them. And in our academies, this poisonous ideology, followed by the malignant and foolish but also by the fashionable and well intentioned, has become a default position. It must forfeit its respectability, its lack of authenticity as history. Its moral nullity has been exposed for all to see.

Again, scholars, teachers, and our civil society, and the institutions that fund and regulate universities and charities, need to challenge a toxic, inhumane ideology that has no basis in the real history or present of the Holy Land, and that justifies otherwise rational people to excuse the dismemberment of babies.

Israel has done many harsh and bad things. Netanyahu’s government, the worst ever in Israeli history, as inept as it is immoral, promotes a maximalist ultranationalism that is both unacceptable and unwise. Everyone has the right to protest against Israel’s policies and actions but not to promote terror sects, the killing of civilians, and the spreading of menacing anti-Semitism.

The Palestinians have legitimate grievances and have endured much brutal injustice. But both of their political entities are utterly flawed: the Palestinian Authority, which rules 40 percent of the West Bank, is moribund, corrupt, inept, and generally disdained—and its leaders have been just as abysmal as those of Israel.

Hamas is a diabolical killing sect that hides among civilians, whom it sacrifices on the altar of resistance—as moderate Arab voices have openly stated in recent days, and much more harshly than Hamas’s apologists in the West. “I categorically condemn Hamas’s targeting of civilians,” the Saudi veteran statesman Prince Turki bin Faisal movingly declared last week. “I also condemn Hamas for giving the higher moral ground to an Israeli government that is universally shunned even by half of the Israeli public … I condemn Hamas for sabotaging the attempt of Saudi Arabia to reach a peaceful resolution to the plight of the Palestinian people.” In an interview with Khaled Meshaal, a member of the Hamas politburo, the Arab journalist Rasha Nabil highlighted Hamas’s sacrifice of its own people for its political interests. Meshaal argued that this was just the cost of resistance: “Thirty million Russians died to defeat Germany,” he said.

Read: Understanding Hamas’s genocidal ideology

Nabil stands as an example to Western journalists who scarcely dare challenge Hamas and its massacres. Nothing is more patronizing and even Orientalist than the romanticization of Hamas’s butchers, whom many Arabs despise. The denial of their atrocities by so many in the West is an attempt to fashion acceptable heroes out of an organization that dismembers babies and defiles the bodies of murdered girls. This is an attempt to save Hamas from itself. Perhaps the West’s Hamas apologists should listen to moderate Arab voices instead of a fundamentalist terror sect.

Hamas’s atrocities place it, like the Islamic State and al-Qaeda, as an abomination beyond tolerance. Israel, like any state, has the right to defend itself, but it must do so with great care and minimal civilian loss, and it will be hard even with a full military incursion to destroy Hamas. Meanwhile, Israel must curb its injustices in the West Bank—or risk destroying itself— because ultimately it must negotiate with moderate Palestinians.

So the war unfolds tragically. As I write this, the pounding of Gaza is killing Palestinian children every day, and that is unbearable. As Israel still grieves its losses and buries its children, we deplore the killing of Israeli civilians just as we deplore the killing of Palestinian civilians. We reject Hamas, evil and unfit to govern, but we do not mistake Hamas for the Palestinian people, whose losses we mourn as we mourn the death of all innocents.

In the wider span of history, sometimes terrible events can shake fortified positions: Anwar Sadat and Menachem Begin made peace after the Yom Kippur War; Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat made peace after the Intifada. The diabolical crimes of October 7 will never be forgotten, but perhaps, in the years to come, after the scattering of Hamas, after Netanyahuism is just a catastrophic memory, Israelis and Palestinians will draw the borders of their states, tempered by 75 years of killing and stunned by one weekend’s Hamas butchery, into mutual recognition. There is no other way.

Simon Sebag Montefiore is the author of Jerusalem: The Biography and most recently The World: A Family History of Humanity.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Simon Sebag Montefiore

Published: Oct 27, 2023

Peace in the israel-palestine conflict had already been difficult to achieve before Hamas’s barbarous October 7 attack and Israel’s military response. Now it seems almost impossible, but its essence is clearer than ever: Ultimately, a negotiation to establish a safe Israel beside a safe Palestinian state.

Whatever the enormous complexities and challenges of bringing about this future, one truth should be obvious among decent people: killing 1,400 people and kidnapping more than 200, including scores of civilians, was deeply wrong. The Hamas attack resembled a medieval Mongol raid for slaughter and human trophies—except it was recorded in real time and published to social media. Yet since October 7, Western academics, students, artists, and activists have denied, excused, or even celebrated the murders by a terrorist sect that proclaims an anti-Jewish genocidal program. Some of this is happening out in the open, some behind the masks of humanitarianism and justice, and some in code, most famously “from the river to the sea,” a chilling phrase that implicitly endorses the killing or deportation of the 9 million Israelis. It seems odd that one has to say: Killing civilians, old people, even babies, is always wrong. But today say it one must.

How can educated people justify such callousness and embrace such inhumanity? All sorts of things are at play here, but much of the justification for killing civilians is based on a fashionable ideology, “decolonization,” which, taken at face value, rules out the negotiation of two states—the only real solution to this century of conflict—and is as dangerous as it is false.

I always wondered about the leftist intellectuals who supported Stalin, and those aristocratic sympathizers and peace activists who excused Hitler. Today’s Hamas apologists and atrocity-deniers, with their robotic denunciations of “settler-colonialism,” belong to the same tradition but worse: They have abundant evidence of the slaughter of old people, teenagers, and children, but unlike those fools of the 1930s, who slowly came around to the truth, they have not changed their views an iota. The lack of decency and respect for human life is astonishing: Almost instantly after the Hamas attack, a legion of people emerged who downplayed the slaughter, or denied actual atrocities had even happened, as if Hamas had just carried out a traditional military operation against soldiers. October 7 deniers, like Holocaust deniers, exist in an especially dark place.

The decolonization narrative has dehumanized Israelis to the extent that otherwise rational people excuse, deny, or support barbarity. It holds that Israel is an “imperialist-colonialist” force, that Israelis are “settler-colonialists,” and that Palestinians have a right to eliminate their oppressors. (On October 7, we all learned what that meant.) It casts Israelis as “white” or “white-adjacent” and Palestinians as “people of color.”

This ideology, powerful in the academy but long overdue for serious challenge, is a toxic, historically nonsensical mix of Marxist theory, Soviet propaganda, and traditional anti-Semitism from the Middle Ages and the 19th century. But its current engine is the new identity analysis, which sees history through a concept of race that derives from the American experience. The argument is that it is almost impossible for the “oppressed” to be themselves racist, just as it is impossible for an “oppressor” to be the subject of racism. Jews therefore cannot suffer racism, because they are regarded as “white” and “privileged”; although they cannot be victims, they can and do exploit other, less privileged people, in the West through the sins of “exploitative capitalism” and in the Middle East through “colonialism.”

This leftist analysis, with its hierarchy of oppressed identities—and intimidating jargon, a clue to its lack of factual rigor—has in many parts of the academy and media replaced traditional universalist leftist values, including internationalist standards of decency and respect for human life and the safety of innocent civilians. When this clumsy analysis collides with the realities of the Middle East, it loses all touch with historical facts.

Indeed, it requires an astonishing leap of ahistorical delusion to disregard the record of anti-Jewish racism over the two millennia since the fall of the Judean Temple in 70 C.E. After all, the October 7 massacre ranks with the medieval mass killings of Jews in Christian and Islamic societies, the Khmelnytsky massacres of 1640s Ukraine, Russian pogroms from 1881 to 1920—and the Holocaust. Even the Holocaust is now sometimes misconstrued—as the actor Whoopi Goldberg notoriously did—as being “not about race,” an approach as ignorant as it is repulsive.

Contrary to the decolonizing narrative, Gaza is not technically occupied by Israel—not in the usual sense of soldiers on the ground. Israel evacuated the Strip in 2005, removing its settlements. In 2007, Hamas seized power, killing its Fatah rivals in a short civil war. Hamas set up a one-party state that crushes Palestinian opposition within its territory, bans same-sex relationships, represses women, and openly espouses the killing of all Jews.

Very strange company for leftists.

Of course, some protesters chanting “from the river to the sea” may have no idea what they’re calling for; they are ignorant and believe that they are simply endorsing “freedom.” Others deny that they are pro-Hamas, insisting that they are simply pro-Palestinian—but feel the need to cast Hamas’s massacre as an understandable response to Israeli-Jewish “colonial” oppression. Yet others are malign deniers who seek the death of Israeli civilians.

The toxicity of this ideology is now clear. Once-respectable intellectuals have shamelessly debated whether 40 babies were dismembered or some smaller number merely had their throats cut or were burned alive. Students now regularly tear down posters of children held as Hamas hostages. It is hard to understand such heartless inhumanity. Our definition of a hate crime is constantly expanding, but if this is not a hate crime, what is? What is happening in our societies? Something has gone wrong.

In a further racist twist, Jews are now accused of the very crimes they themselves have suffered. Hence the constant claim of a “genocide” when no genocide has taken place or been intended. Israel, with Egypt, has imposed a blockade on Gaza since Hamas took over, and has periodically bombarded the Strip in retaliation for regular rocket attacks. After more than 4,000 rockets were fired by Hamas and its allies into Israel, the 2014 Gaza War resulted in more than 2,000 Palestinian deaths. More than 7,000 Palestinians, including many children, have died so far in this war, according to Hamas. This is a tragedy—but this is not a genocide, a word that has now been so devalued by its metaphorical abuse that it has become meaningless.

I should also say that Israeli rule of the Occupied Territories of the West Bank is different and, to my mind, unacceptable, unsustainable, and unjust. The Palestinians in the West Bank have endured a harsh, unjust, and oppressive occupation since 1967. Settlers under the disgraceful Netanyahu government have harassed and persecuted Palestinians in the West Bank: 146 Palestinians in the West Bank and East Jerusalem were killed in 2022 and at least 153 in 2023 before the Hamas attack, and more than 90 since. Again: This is appalling and unacceptable, but not genocide.

Although there is a strong instinct to make this a Holocaust-mirroring “genocide,” it is not: The Palestinians suffer from many things, including military occupation; settler intimidation and violence; corrupt Palestinian political leadership; callous neglect by their brethren in more than 20 Arab states; the rejection by Yasser Arafat, the late Palestinian leader, of compromise plans that would have seen the creation of an independent Palestinian state; and so on. None of this constitutes genocide, or anything like genocide. The Israeli goal in Gaza—for practical reasons, among others—is to minimize the number of Palestinian civilians killed. Hamas and like-minded organizations have made it abundantly clear over the years that maximizing the number of Palestinian casualties is in their strategic interest. (Put aside all of this and consider: The world Jewish population is still smaller than it was in 1939, because of the damage done by the Nazis. The Palestinian population has grown, and continues to grow. Demographic shrinkage is one obvious marker of genocide. In total, roughly 120,000 Arabs and Jews have been killed in the conflict over Palestine and Israel since 1860. By contrast, at least 500,000 people, mainly civilians, have been killed in the Syrian civil war since it began in 2011.)

If the ideology of decolonization, taught in our universities as a theory of history and shouted in our streets as self-evidently righteous, badly misconstrues the present reality, does it reflect the history of Israel as it claims to do? It does not. Indeed, it does not accurately describe either the foundation of Israel or the tragedy of the Palestinians.

According to the decolonizers, Israel is and always has been an illegitimate freak-state because it was fostered by the British empire and because some of its founders were European-born Jews.

In this narrative, Israel is tainted by imperial Britain’s broken promise to deliver Arab independence, and its kept promise to support a “national home for the Jewish people,” in the language of the 1917 Balfour Declaration. But the supposed promise to Arabs was in fact an ambiguous 1915 agreement with Sharif Hussein of Mecca, who wanted his Hashemite family to rule the entire region. In part, he did not receive this new empire because his family had much less regional support than he claimed. Nonetheless, ultimately Britain delivered three kingdoms—Iraq, Jordan, and Hejaz—to the family.

The imperial powers—Britain and France—made all sorts of promises to different peoples, and then put their own interests first. Those promises to the Jews and the Arabs during World War I were typical. Afterward, similar promises were made to the Kurds, the Armenians, and others, none of which came to fruition. But the central narrative that Britain betrayed the Arab promise and backed the Jewish one is incomplete. In the 1930s, Britain turned against Zionism, and from 1937 to 1939 moved toward an Arab state with no Jewish one at all. It was an armed Jewish revolt, from 1945 to 1948 against imperial Britain, that delivered the state.

Israel exists thanks to this revolt, and to international law and cooperation, something leftists once believed in. The idea of a Jewish “homeland” was proposed in three declarations by Britain (signed by Balfour), France, and the United States, then promulgated in a July 1922 resolution by the League of Nations that created the British “mandates” over Palestine and Iraq that matched French “mandates” over Syria and Lebanon. In 1947, the United Nations devised the partition of the British mandate of Palestine into two states, Arab and Jewish.

The carving of such states out of these mandates was not exceptional, either. At the end of World War II, France granted independence to Syria and Lebanon, newly conceived nation-states. Britain created Iraq and Jordan in a similar way. Imperial powers designed most of the countries in the region, except Egypt.

Nor was the imperial promise of separate homelands for different ethnicities or sects unique. The French had promised independent states for the Druze, Alawites, Sunnis, and Maronites but in the end combined them into Syria and Lebanon. All of these states had been “vilayets” and “sanjaks” (provinces) of the Turkish Ottoman empire, ruled from Constantinople, from 1517 until 1918.

The concept of “partition” is, in the decolonization narrative, regarded as a wicked imperial trick. But it was entirely normal in the creation of 20th-century nation-states, which were typically fashioned out of fallen empires. And sadly, the creation of nation-states was frequently marked by population swaps, huge refugee migrations, ethnic violence, and full-scale wars. Think of the Greco-Turkish war of 1921–22 or the partition of India in 1947. In this sense, Israel-Palestine was typical.

At the heart of decolonization ideology is the categorization of all Israelis, historic and present, as “colonists.” This is simply wrong. Most Israelis are descended from people who migrated to the Holy Land from 1881 to 1949. They were not completely new to the region. The Jewish people ruled Judean kingdoms and prayed in the Jerusalem Temple for a thousand years, then were ever present there in smaller numbers for the next 2,000 years. In other words, Jews are indigenous in the Holy Land, and if one believes in the return of exiled people to their homeland, then the return of the Jews is exactly that. Even those who deny this history or regard it as irrelevant to modern times must acknowledge that Israel is now the home and only home of 9 million Israelis who have lived there for four, five, six generations.

Most migrants to, say, the United Kingdom or the United States are regarded as British or American within a lifetime. Politics in both countries is filled with prominent leaders—Suella Braverman and David Lammy, Kamala Harris and Nikki Haley—whose parents or grandparents migrated from India, West Africa, or South America. No one would describe them as “settlers.” Yet Israeli families resident in Israel for a century are designated as “settler-colonists” ripe for murder and mutilation. And contrary to Hamas apologists, the ethnicity of perpetrators or victims never justifies atrocities. They would be atrocious anywhere, committed by anyone with any history. It is dismaying that it is often self-declared “anti-racists” who are now advocating exactly this murder by ethnicity.

Those on the left believe migrants who escape from persecution should be welcomed and allowed to build their lives elsewhere. Almost all of the ancestors of today’s Israelis escaped persecution.

If the “settler-colonist” narrative is not true, it is true that the conflict is the result of the brutal rivalry and battle for land between two ethnic groups, both with rightful claims to live there. As more Jews moved to the region, the Palestinian Arabs, who had lived there for centuries and were the clear majority, felt threatened by these immigrants. The Palestinian claim to the land is not in doubt, nor is the authenticity of their history, nor their legitimate claim to their own state. But initially the Jewish migrants did not aspire to a state, merely to live and farm in the vague “homeland.” In 1918, the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann met the Hashemite Prince Faisal Bin Hussein to discuss the Jews living under his rule as king of greater Syria. The conflict today was not inevitable. It became so as the communities refused to share and coexist, and then resorted to arms.

Even more preposterous than the “colonizer” label is the “whiteness” trope that is key to the decolonization ideology. Again: simply wrong. Israel has a large community of Ethiopian Jews, and about half of all Israelis—that is, about 5 million people—are Mizrahi, the descendants of Jews from Arab and Persian lands, people of the Middle East. They are neither “settlers” nor “colonialists” nor “white” Europeans at all but inhabitants of Baghdad and Cairo and Beirut for many centuries, even millennia, who were driven out after 1948.

A word about that year, 1948, the year of Israel’s War of Independence and the Palestinian Nakba (“Catastrophe”), which in decolonization discourse amounted to ethnic cleansing. There was indeed intense ethnic violence on both sides when Arab states invaded the territory and, together with Palestinian militias, tried to stop the creation of a Jewish state. They failed; what they ultimately stopped was the creation of a Palestinian state, as intended by the United Nations. The Arab side sought the killing or expulsion of the entire Jewish community—in precisely the murderous ways we saw on October 7. And in the areas the Arab side did capture, such as East Jerusalem, every Jew was expelled.

In this brutal war, Israelis did indeed drive some Palestinians from their homes; others fled the fighting; yet others stayed and are now Israeli Arabs who have the vote in the Israeli democracy. (Some 25 percent of today’s Israelis are Arabs and Druze.) About 700,000 Palestinians lost their homes. That is an enormous figure and a historic tragedy. Starting in 1948, some 900,000 Jews lost their homes in Islamic countries and most of them moved to Israel. These events are not directly comparable, and I don’t mean to propose a competition in tragedy or hierarchy of victimhood. But the past is a lot more complicated than the decolonizers would have you believe.

Out of this imbroglio, one state emerged, Israel, and one did not, Palestine. Its formation is long overdue.

It is bizarre that a small state in the Middle East attracts so much passionate attention in the West that students run through California schools shouting “Free Palestine.” But the Holy Land has an exceptional place in Western history. It is embedded in our cultural consciousness, thanks to the Hebrew and Christian Bibles, the story of Judaism, the foundation of Christianity, the Quran and the creation of Islam, and the Crusades that together have made Westerners feel involved in its destiny. The British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, the real architect of the Balfour Declaration, used to say that the names of places in Palestine “were more familiar to me than those on the Western Front.” This special affinity with the Holy Land initially worked in favor of the Jewish return, but lately it has worked against Israel. Westerners eager to expose the crimes of Euro-American imperialism but unable to offer a remedy have, often without real knowledge of the actual history, coalesced around Israel and Palestine as the world’s most vivid example of imperialist injustice.

The open world of liberal democracies—or the West, as it used to be called—is today polarized by paralyzed politics, petty but vicious cultural feuds about identity and gender, and guilt about historical successes and sins, a guilt that is bizarrely atoned for by showing sympathy for, even attraction to, enemies of our democratic values. In this scenario, Western democracies are always bad actors, hypocritical and neo-imperialist, while foreign autocracies or terror sects such as Hamas are enemies of imperialism and therefore sincere forces for good. In this topsy-turvy scenario, Israel is a living metaphor and penance for the sins of the West. The result is the intense scrutiny of Israel and the way it is judged, using standards rarely attained by any nation at war, including the United States.

But the decolonizing narrative is much worse than a study in double standards; it dehumanizes an entire nation and excuses, even celebrates, the murder of innocent civilians. As these past two weeks have shown, decolonization is now the authorized version of history in many of our schools and supposedly humanitarian institutions, and among artists and intellectuals. It is presented as history, but it is actually a caricature, zombie history with its arsenal of jargon—the sign of a coercive ideology, as Foucault argued—and its authoritarian narrative of villains and victims. And it only stands up in a landscape in which much of the real history is suppressed and in which all Western democracies are bad-faith actors. Although it lacks the sophistication of Marxist dialectic, its self-righteous moral certainty imposes a moral framework on a complex, intractable situation, which some may find consoling. Whenever you read a book or an article and it uses the phrase “settler-colonialist,” you are dealing with ideological polemic, not history.

Ultimately, this zombie narrative is a moral and political cul-de-sac that leads to slaughter and stalemate. That is no surprise, because it is based on sham history: “An invented past can never be used,” wrote James Baldwin. “It cracks and crumbles under the pressures of life like clay.”

Even when the word decolonization does not appear, this ideology is embedded in partisan media coverage of the conflict and suffuses recent condemnations of Israel. The student glee in response to the slaughter at Harvard, the University of Virginia, and other universities; the support for Hamas amongst artists and actors, along with the weaselly equivocations by leaders at some of America’s most famous research institutions, have displayed a shocking lack of morality, humanity, and basic decency.

One repellent example was an open letter signed by thousands of artists, including famous British actors such as Tilda Swinton and Steve Coogan. It warned against imminent Israeli war crimes and totally ignored the casus belli: the slaughter of 1,400 people.

The journalist Deborah Ross wrote in a powerful Times of London article that she was “utterly, utterly floored” that the letter contained “no mention of Hamas” and no mention of the “kidnapping and murder of babies, children, grandparents, young people dancing peacefully at a peace festival. The lack of basic compassion and humanity, that’s what was so unbelievably flooring. Is it so difficult? To support and feel for Palestinian citizens … while also acknowledging the indisputable horror of the Hamas attacks?” Then she asked this thespian parade of moral nullities: “What does it solve, a letter like that? And why would anyone sign it?”

The Israel-Palestine conflict is desperately difficult to solve, and decolonization rhetoric makes even less likely the negotiated compromise that is the only way out.

Since its founding in 1987, Hamas has used the murder of civilians to spoil any chance of a two-state solution. In 1993, its suicide bombings of Israeli civilians were designed to destroy the two-state Oslo Accords that recognized Israel and Palestine. This month, the Hamas terrorists unleashed their slaughter in part to undermine a peace with Saudi Arabia that would have improved Palestinian politics and standard of life, and reinvigorated Hamas’s sclerotic rival, the Palestinian Authority. In part, they served Iran to prevent the empowering of Saudi Arabia, and their atrocities were of course a spectacular trap to provoke Israeli overreaction. They are most probably getting their wish, but to do this they are cynically exploiting innocent Palestinian people as a sacrifice to political means, a second crime against civilians. In the same way, the decolonization ideology, with its denial of Israel’s right to exist and its people’s right to live safely, makes a Palestinian state less likely if not impossible.

The problem in our countries is easier to fix: Civic society and the shocked majority should now assert themselves. The radical follies of students should not alarm us overmuch; students are always thrilled by revolutionary extremes. But the indecent celebrations in London, Paris, and New York City, and the clear reluctance among leaders at major universities to condemn the killings, have exposed the cost of neglecting this issue and letting “decolonization” colonize our academy.

Parents and students can move to universities that are not led by equivocators and patrolled by deniers and ghouls; donors can withdraw their generosity en masse, and that is starting in the United States. Philanthropists can pull the funding of humanitarian foundations led by people who support war crimes against humanity (against victims selected by race). Audiences can easily decide not to watch films starring actors who ignore the killing of children; studios do not have to hire them. And in our academies, this poisonous ideology, followed by the malignant and foolish but also by the fashionable and well intentioned, has become a default position. It must forfeit its respectability, its lack of authenticity as history. Its moral nullity has been exposed for all to see.

Again, scholars, teachers, and our civil society, and the institutions that fund and regulate universities and charities, need to challenge a toxic, inhumane ideology that has no basis in the real history or present of the Holy Land, and that justifies otherwise rational people to excuse the dismemberment of babies.

Israel has done many harsh and bad things. Netanyahu’s government, the worst ever in Israeli history, as inept as it is immoral, promotes a maximalist ultranationalism that is both unacceptable and unwise. Everyone has the right to protest against Israel’s policies and actions but not to promote terror sects, the killing of civilians, and the spreading of menacing anti-Semitism.

The Palestinians have legitimate grievances and have endured much brutal injustice. But both of their political entities are utterly flawed: the Palestinian Authority, which rules 40 percent of the West Bank, is moribund, corrupt, inept, and generally disdained—and its leaders have been just as abysmal as those of Israel.

Hamas is a diabolical killing sect that hides among civilians, whom it sacrifices on the altar of resistance—as moderate Arab voices have openly stated in recent days, and much more harshly than Hamas’s apologists in the West. “I categorically condemn Hamas’s targeting of civilians,” the Saudi veteran statesman Prince Turki bin Faisal movingly declared last week. “I also condemn Hamas for giving the higher moral ground to an Israeli government that is universally shunned even by half of the Israeli public … I condemn Hamas for sabotaging the attempt of Saudi Arabia to reach a peaceful resolution to the plight of the Palestinian people.” In an interview with Khaled Meshaal, a member of the Hamas politburo, the Arab journalist Rasha Nabil highlighted Hamas’s sacrifice of its own people for its political interests. Meshaal argued that this was just the cost of resistance: “Thirty million Russians died to defeat Germany,” he said.

Nabil stands as an example to Western journalists who scarcely dare challenge Hamas and its massacres. Nothing is more patronizing and even Orientalist than the romanticization of Hamas’s butchers, whom many Arabs despise. The denial of their atrocities by so many in the West is an attempt to fashion acceptable heroes out of an organization that dismembers babies and defiles the bodies of murdered girls. This is an attempt to save Hamas from itself. Perhaps the West’s Hamas apologists should listen to moderate Arab voices instead of a fundamentalist terror sect.

Hamas’s atrocities place it, like the Islamic State and al-Qaeda, as an abomination beyond tolerance. Israel, like any state, has the right to defend itself, but it must do so with great care and minimal civilian loss, and it will be hard even with a full military incursion to destroy Hamas. Meanwhile, Israel must curb its injustices in the West Bank—or risk destroying itself—because ultimately it must negotiate with moderate Palestinians.

So the war unfolds tragically. As I write this, the pounding of Gaza is killing Palestinian children every day, and that is unbearable. As Israel still grieves its losses and buries its children, we deplore the killing of Israeli civilians just as we deplore the killing of Palestinian civilians. We reject Hamas, evil and unfit to govern, but we do not mistake Hamas for the Palestinian people, whose losses we mourn as we mourn the death of all innocents.

In the wider span of history, sometimes terrible events can shake fortified positions: Anwar Sadat and Menachem Begin made peace after the Yom Kippur War; Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat made peace after the Intifada. The diabolical crimes of October 7 will never be forgotten, but perhaps, in the years to come, after the scattering of Hamas, after Netanyahuism is just a catastrophic memory, Israelis and Palestinians will draw the borders of their states, tempered by 75 years of killing and stunned by one weekend’s Hamas butchery, into mutual recognition. There is no other way.

Simon Sebag Montefiore is the author of Jerusalem: The Biography and most recently The World: A Family History of Humanity.

==

Intersectionality and Postcolonial Theory have always been bogus and fraudulent, even just at the level of US society, where they were concocted by ignorant idiots and ideologues. The fact people are using them to interpret geopolitics - but not, for example, Syria or Nigeria - is idiotic and a failure of education. Or, more accurately, the capture and corruption of education, as this is not accidental.

#Simon Sebag Montefiore#decolonisation#decolonise palestine#decolonize#decolonization#decolonize palestine#jihad#genocide#gaza genocide#palestinian genocide#palestine#palestinians#israel#hamas#hamas terrorism#hamas terrorists#hamas supporters#pro hamas#pro palestine#pro palestine is pro hamas#antisemitism#religion is a mental illness

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Whatever the enormous complexities and challenges of bringing about this future, one truth should be obvious among decent people: killing 1,400 people and kidnapping more than 200, including scores of civilians, was deeply wrong. The Hamas attack resembled a medieval Mongol raid for slaughter and human trophies—except it was recorded in real time and published to social media. Yet since October 7, Western academics, students, artists, and activists have denied, excused, or even celebrated the murders by a terrorist sect that proclaims an anti-Jewish genocidal program. Some of this is happening out in the open, some behind the masks of humanitarianism and justice, and some in code, most famously “from the river to the sea,” a chilling phrase that implicitly endorses the killing or deportation of the 9 million Israelis. It seems odd that one has to say: Killing civilians, old people, even babies, is always wrong. But today say it one must.

How can educated people justify such callousness and embrace such inhumanity? All sorts of things are at play here, but much of the justification for killing civilians is based on a fashionable ideology, “decolonization,” which, taken at face value, rules out the negotiation of two states—the only real solution to this century of conflict—and is as dangerous as it is false.

I always wondered about the leftist intellectuals who supported Stalin, and those aristocratic sympathizers and peace activists who excused Hitler. Today’s Hamas apologists and atrocity-deniers, with their robotic denunciations of “settler-colonialism,” belong to the same tradition but worse: They have abundant evidence of the slaughter of old people, teenagers, and children, but unlike those fools of the 1930s, who slowly came around to the truth, they have not changed their views an iota. The lack of decency and respect for human life is astonishing: Almost instantly after the Hamas attack, a legion of people emerged who downplayed the slaughter, or denied actual atrocities had even happened, as if Hamas had just carried out a traditional military operation against soldiers. October 7 deniers, like Holocaust deniers, exist in an especially dark place.

The decolonization narrative has dehumanized Israelis to the extent that otherwise rational people excuse, deny, or support barbarity. It holds that Israel is an “imperialist-colonialist” force, that Israelis are “settler-colonialists,” and that Palestinians have a right to eliminate their oppressors. (On October 7, we all learned what that meant.) It casts Israelis as “white” or “white-adjacent” and Palestinians as “people of color.”

This ideology, powerful in the academy but long overdue for serious challenge, is a toxic, historically nonsensical mix of Marxist theory, Soviet propaganda, and traditional anti-Semitism from the Middle Ages and the 19th century. But its current engine is the new identity analysis, which sees history through a concept of race that derives from the American experience. The argument is that it is almost impossible for the “oppressed” to be themselves racist, just as it is impossible for an “oppressor” to be the subject of racism. Jews therefore cannot suffer racism, because they are regarded as “white” and “privileged”; although they cannot be victims, they can and do exploit other, less privileged people, in the West through the sins of “exploitative capitalism” and in the Middle East through “colonialism.”

This leftist analysis, with its hierarchy of oppressed identities—and intimidating jargon, a clue to its lack of factual rigor—has in many parts of the academy and media replaced traditional universalist leftist values, including internationalist standards of decency and respect for human life and the safety of innocent civilians. When this clumsy analysis collides with the realities of the Middle East, it loses all touch with historical facts.

Indeed, it requires an astonishing leap of ahistorical delusion to disregard the record of anti-Jewish racism over the two millennia since the fall of the Judean Temple in 70 C.E. After all, the October 7 massacre ranks with the medieval mass killings of Jews in Christian and Islamic societies, the Khmelnytsky massacres of 1640s Ukraine, Russian pogroms from 1881 to 1920—and the Holocaust. Even the Holocaust is now sometimes misconstrued—as the actor Whoopi Goldberg notoriously did—as being “not about race,” an approach as ignorant as it is repulsive.

Contrary to the decolonizing narrative, Gaza is not technically occupied by Israel—not in the usual sense of soldiers on the ground. Israel evacuated the Strip in 2005, removing its settlements. In 2007, Hamas seized power, killing its Fatah rivals in a short civil war. Hamas set up a one-party state that crushes Palestinian opposition within its territory, bans same-sex relationships, represses women, and openly espouses the killing of all Jews.

Very strange company for leftists.

(…)

The toxicity of this ideology is now clear. Once-respectable intellectuals have shamelessly debated whether 40 babies were dismembered or some smaller number merely had their throats cut or were burned alive. Students now regularly tear down posters of children held as Hamas hostages. It is hard to understand such heartless inhumanity. Our definition of a hate crime is constantly expanding, but if this is not a hate crime, what is? What is happening in our societies? Something has gone wrong.

In a further racist twist, Jews are now accused of the very crimes they themselves have suffered. Hence the constant claim of a “genocide” when no genocide has taken place or been intended. Israel, with Egypt, has imposed a blockade on Gaza since Hamas took over, and has periodically bombarded the Strip in retaliation for regular rocket attacks. After more than 4,000 rockets were fired by Hamas and its allies into Israel, the 2014 Gaza War resulted in more than 2,000 Palestinian deaths. More than 7,000 Palestinians, including many children, have died so far in this war, according to Hamas. This is a tragedy—but this is not a genocide, a word that has now been so devalued by its metaphorical abuse that it has become meaningless.

(…)

Although there is a strong instinct to make this a Holocaust-mirroring “genocide,” it is not: The Palestinians suffer from many things, including military occupation; settler intimidation and violence; corrupt Palestinian political leadership; callous neglect by their brethren in more than 20 Arab states; the rejection by Yasser Arafat, the late Palestinian leader, of compromise plans that would have seen the creation of an independent Palestinian state; and so on. None of this constitutes genocide, or anything like genocide. The Israeli goal in Gaza—for practical reasons, among others—is to minimize the number of Palestinian civilians killed. Hamas and like-minded organizations have made it abundantly clear over the years that maximizing the number of Palestinian casualties is in their strategic interest. (Put aside all of this and consider: The world Jewish population is still smaller than it was in 1939, because of the damage done by the Nazis. The Palestinian population has grown, and continues to grow. Demographic shrinkage is one obvious marker of genocide. In total, roughly 120,000 Arabs and Jews have been killed in the conflict over Palestine and Israel since 1860. By contrast, at least 500,000 people, mainly civilians, have been killed in the Syrian civil war since it began in 2011.)

(…)

At the heart of decolonization ideology is the categorization of all Israelis, historic and present, as “colonists.” This is simply wrong. Most Israelis are descended from people who migrated to the Holy Land from 1881 to 1949. They were not completely new to the region. The Jewish people ruled Judean kingdoms and prayed in the Jerusalem Temple for a thousand years, then were ever present there in smaller numbers for the next 2,000 years. In other words, Jews are indigenous in the Holy Land, and if one believes in the return of exiled people to their homeland, then the return of the Jews is exactly that. Even those who deny this history or regard it as irrelevant to modern times must acknowledge that Israel is now the home and only home of 9 million Israelis who have lived there for four, five, six generations.

Most migrants to, say, the United Kingdom or the United States are regarded as British or American within a lifetime. Politics in both countries is filled with prominent leaders—Suella Braverman and David Lammy, Kamala Harris and Nikki Haley—whose parents or grandparents migrated from India, West Africa, or South America. No one would describe them as “settlers.” Yet Israeli families resident in Israel for a century are designated as “settler-colonists” ripe for murder and mutilation. And contrary to Hamas apologists, the ethnicity of perpetrators or victims never justifies atrocities. They would be atrocious anywhere, committed by anyone with any history. It is dismaying that it is often self-declared “anti-racists” who are now advocating exactly this murder by ethnicity.

Those on the left believe migrants who escape from persecution should be welcomed and allowed to build their lives elsewhere. Almost all of the ancestors of today’s Israelis escaped persecution.

(…)

Even more preposterous than the “colonizer” label is the “whiteness” trope that is key to the decolonization ideology. Again: simply wrong. Israel has a large community of Ethiopian Jews, and about half of all Israelis—that is, about 5 million people—are Mizrahi, the descendants of Jews from Arab and Persian lands, people of the Middle East. They are neither “settlers” nor “colonialists” nor “white” Europeans at all but inhabitants of Baghdad and Cairo and Beirut for many centuries, even millennia, who were driven out after 1948.

(…)

In this brutal war, Israelis did indeed drive some Palestinians from their homes; others fled the fighting; yet others stayed and are now Israeli Arabs who have the vote in the Israeli democracy. (Some 25 percent of today’s Israelis are Arabs and Druze.) About 700,000 Palestinians lost their homes. That is an enormous figure and a historic tragedy. Starting in 1948, some 900,000 Jews lost their homes in Islamic countries and most of them moved to Israel. These events are not directly comparable, and I don’t mean to propose a competition in tragedy or hierarchy of victimhood. But the past is a lot more complicated than the decolonizers would have you believe.

(…)

The open world of liberal democracies—or the West, as it used to be called—is today polarized by paralyzed politics, petty but vicious cultural feuds about identity and gender, and guilt about historical successes and sins, a guilt that is bizarrely atoned for by showing sympathy for, even attraction to, enemies of our democratic values. In this scenario, Western democracies are always bad actors, hypocritical and neo-imperialist, while foreign autocracies or terror sects such as Hamas are enemies of imperialism and therefore sincere forces for good. In this topsy-turvy scenario, Israel is a living metaphor and penance for the sins of the West. The result is the intense scrutiny of Israel and the way it is judged, using standards rarely attained by any nation at war, including the United States.

But the decolonizing narrative is much worse than a study in double standards; it dehumanizes an entire nation and excuses, even celebrates, the murder of innocent civilians. As these past two weeks have shown, decolonization is now the authorized version of history in many of our schools and supposedly humanitarian institutions, and among artists and intellectuals. It is presented as history, but it is actually a caricature, zombie history with its arsenal of jargon—the sign of a coercive ideology, as Foucault argued—and its authoritarian narrative of villains and victims. And it only stands up in a landscape in which much of the real history is suppressed and in which all Western democracies are bad-faith actors. Although it lacks the sophistication of Marxist dialectic, its self-righteous moral certainty imposes a moral framework on a complex, intractable situation, which some may find consoling. Whenever you read a book or an article and it uses the phrase “settler-colonialist,” you are dealing with ideological polemic, not history.

(…)

Even when the word decolonization does not appear, this ideology is embedded in partisan media coverage of the conflict and suffuses recent condemnations of Israel. The student glee in response to the slaughter at Harvard, the University of Virginia, and other universities; the support for Hamas amongst artists and actors, along with the weaselly equivocations by leaders at some of America’s most famous research institutions, have displayed a shocking lack of morality, humanity, and basic decency.

(…)

Since its founding in 1987, Hamas has used the murder of civilians to spoil any chance of a two-state solution. In 1993, its suicide bombings of Israeli civilians were designed to destroy the two-state Olso Accords that recognized Israel and Palestine. This month, the Hamas terrorists unleashed their slaughter in part to undermine a peace with Saudi Arabia that would have improved Palestinian politics and standard of life, and reinvigorated Hamas’s sclerotic rival, the Palestinian Authority. In part, they served Iran to prevent the empowering of Saudi Arabia, and their atrocities were of course a spectacular trap to provoke Israeli overreaction. They are most probably getting their wish, but to do this they are cynically exploiting innocent Palestinian people as a sacrifice to political means, a second crime against civilians. In the same way, the decolonization ideology, with its denial of Israel’s right to exist and its people’s right to live safely, makes a Palestinian state less likely if not impossible.

(…)

Again, scholars, teachers, and our civil society, and the institutions that fund and regulate universities and charities, need to challenge a toxic, inhumane ideology that has no basis in the real history or present of the Holy Land, and that justifies otherwise rational people to excuse the dismemberment of babies.

(…)

The Palestinians have legitimate grievances and have endured much brutal injustice. But both of their political entities are utterly flawed: the Palestinian Authority, which rules 40 percent of the West Bank, is moribund, corrupt, inept, and generally disdained—and its leaders have been just as abysmal as those of Israel.

Hamas is a diabolical killing sect that hides among civilians, whom it sacrifices on the altar of resistance—as moderate Arab voices have openly stated in recent days, and much more harshly than Hamas’s apologists in the West. “I categorically condemn Hamas’s targeting of civilians,” the Saudi veteran statesman Prince Turki bin Faisal movingly declared last week. “I also condemn Hamas for giving the higher moral ground to an Israeli government that is universally shunned even by half of the Israeli public … I condemn Hamas for sabotaging the attempt of Saudi Arabia to reach a peaceful resolution to the plight of the Palestinian people.” In an interview with Khaled Meshaal, a member of the Hamas politburo, the Arab journalist Rasha Nabil highlighted Hamas’s sacrifice of its own people for its political interests. Meshaal argued that this was just the cost of resistance: “Thirty million Russians died to defeat Germany,” he said.

Nabil stands as an example to Western journalists who scarcely dare challenge Hamas and its massacres. Nothing is more patronizing and even Orientalist than the romanticization of Hamas’s butchers, whom many Arabs despise. The denial of their atrocities by so many in the West is an attempt to fashion acceptable heroes out of an organization that dismembers babies and defiles the bodies of murdered girls. This is an attempt to save Hamas from itself. Perhaps the West’s Hamas apologists should listen to moderate Arab voices instead of a fundamentalist terror sect.

Hamas’s atrocities place it, like the Islamic State and al-Qaeda, as an abomination beyond tolerance. Israel, like any state, has the right to defend itself, but it must do so with great care and minimal civilian loss, and it will be hard even with a full military incursion to destroy Hamas. Meanwhile, Israel must curb its injustices in the West Bank—or risk destroying itself—because ultimately it must negotiate with moderate Palestinians.

(…)