#niggerati

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

"Those that don't got it, can't show it. Those that got it, can't hide it." - Zora Neale Hurston . . . Happy Birthday Maman #Zora. Eatonville's #HoodooWoman and self-proclaimed member of the #Niggerati. . . . 🎨 by @blkasfuk . . . #Hoodoo #Rootwork #Conjure #Ancestors #MamiWata#Mermaids #MamanDlo #Njuzu #WaterSpirits #Vodou#Voodoo #africanreligion #Blackwomen #blitches#blackwitches #blitchesofinstagram #AfricanSpirituality#Blackspirituality #Juju #WestAfrica #blackart #africanreligion https://www.instagram.com/p/B7B6wSknjSz/?igshid=yxcjvnb89ork

#zora#hoodoowoman#niggerati#hoodoo#rootwork#conjure#ancestors#mamiwata#mermaids#mamandlo#njuzu#waterspirits#vodou#voodoo#africanreligion#blackwomen#blitches#blackwitches#blitchesofinstagram#africanspirituality#blackspirituality#juju#westafrica#blackart

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lucifer (Salomé Series), 1930.

- Richard Bruce Nugent (1906-1987).

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

#BlackResistance

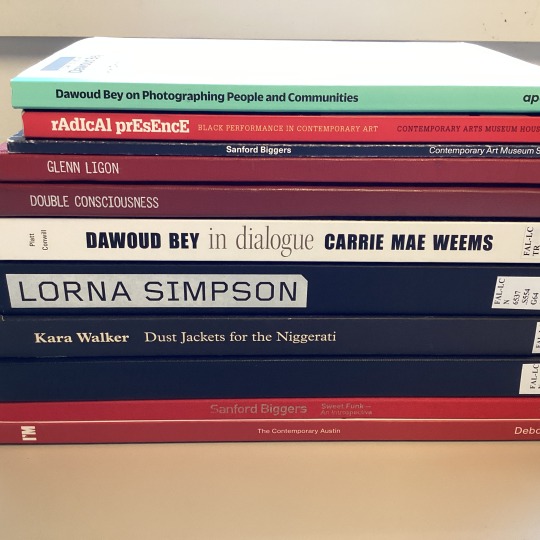

Some of the powerhouse contemporary artists’ books from the stacks!

Dawoud Bey on photographing people and communities / photographs and text by Dawoud Bey ; introduction by Brian Ulrich. 2019. HOLLIS number: 99153846094103941

Lorna Simpson / Thelma Golden, Kellie Jones, Chrissie Iles, Naomi Beckwith. 2022

HOLLIS number: 99156213824303941

Kara Walker : Dust jackets for the niggerati. 2013. HOLLIS number: 990138041340203941

I'm / Deborah Roberts. 2021. HOLLIS number: 99156414672603941

Glenn Ligon : unbecoming / Judith Tannenbaum ; with essays by Richard Meyer and Thelma Golden ; and an interview with Glenn Ligon by Byron Kim. c1997

HOLLIS number: 990076940110203941

Dawoud Bey & Carrie Mae Weems : in dialogue / Ron Platt and Kinshasha Holman Conwill. 2022. HOLLIS number: 99156378937603941

Double consciousness : Black conceptual art since 1970 : Terry Adkins, EdgarArceneaux, Sanford Biggers ... / essay by Valerie Cassel Oliver, Franklin Sirmans. 2005. HOLLIS number

990095704830203941

Radical presence : black performance in contemporary art / Valerie Cassel Oliver ; essays by Yona Backer, Naomi Beckwith, Valerie Cassel Oliver, Tavia Nyong'o, Clifford Owens, Franklin Sirmans. 2013. HOLLIS number: 990137858880203941

Sanford Biggers / organized for the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis by Lisa Melandri.

2019. HOLLIS number: 99153814871703941

Theaster Gates : black archive / Kunsthaus Bregenz ; Herausgeber, Thomas D. Trummer.

2017. HOLLIS number: 990149445900203941

Sanford Biggers : sweet funk-- an introspective / Eugenie Tsai ; with an essay by Gregory Volk. 2011. HOLLIS number: 990133106710203941

#BlackHistoryMonth#BlackResistance#Blackartists#DawoundBey#CarrieMaeWeems#LornaSimpson#DeborahRoberts#SanfordBiggers#TheasterGates#KaraWalker#GlennLigon#HarvardFineArtsLibrary#Fineartslibrary#Harvard#HarvardLibrary#harvardfineartslibrary#fineartslibrary#harvard#harvard library#harvardfineartslib#harvardlibrary#Contemporaryartists#Contemporaryblackartists

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

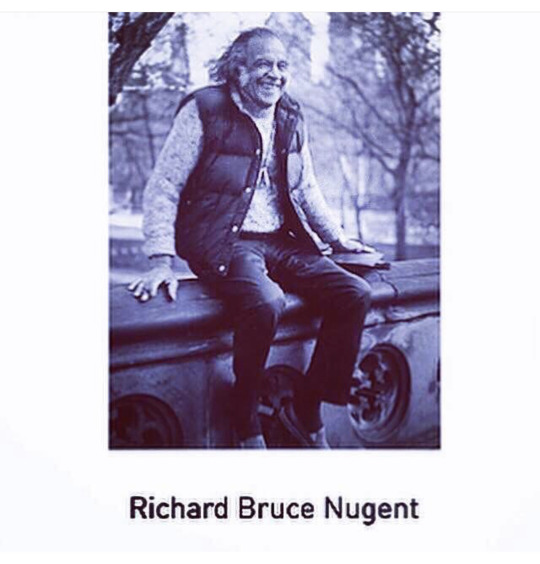

Day 19: Richard Bruce Nugent was a Harlem Renaissance Painter and Writer who gained notoriety in the Harlem Renaissance period (approx. 1918 - late 1930s), which coincided with the Jim Crow Era (approx. late 1880s. - early 1970s). Although there were many gay artists and writers at the time, he was one of the few who were relatively open about their sexuality. This was particularly brave considering black and LGBTQ people were regularly jailed, beaten, lynched, and/or murdered at the time. Nugent’s written and visual work depicted elegant images of interracial homoeroticism. As such, it was not well received by some of his closeted contemporaries. Fellow gay writer and philosopher, Alain Locke spoke out against Nugent’s works specifically saying that it radically promoted the effeminacy and decadence of the homosexual lifestyle.

However poet, Langston Hughes and other gay Harlem Renaissance contributors celebrated Nugent. They met at speak easies like Niggerati Manor where they socialized freely hidden away from the damning and often dangerous grip of Jim Crow. These moments of unguarded intimacy inspired one of Nugent’s most notable written works titled, “Smoke, Lillies, & Jade,” for The Fire!!! Press and has the distinction of being the first published work written from a black homosexual point of view.

Gay codes were one way Nugent was able to use homoerotic themes and motifs in his work. LGBTQ people adopted gay codes as a second language and a necessity essential to their survival at the time. They were used in much the same ways that Negro Spirituals, Call & Response, quilt patterns were used by slaves in Antebellum. Both slaves and LGBTQ people needed a way to communicate effectively with each other without being jailed, beaten, or killed by their oppressors. Nugent was very prolific at this and thanks to him we have a rich source of LGBTQ historical information on what life was like for black homosexuals during Jim Crow and the Harlem Renaissance.

#BlackHistoryRebootPRIDEEdition

#LGBTQPride

#LGBTQHistoryMaters

#BlackQueerIcons

#BlackHistoryMatters

#IntersectionalityMatters

1 note

·

View note

Text

Where Is The Niggerati?

Dreams of black writers

black, queer like me

conversations never grow tired

a unified future we all see.

No more microaggressions

or awkward, harrowing looks

or acts of repression

or reminders of what they took.

Beautiful black faces

inhabiting all my favorite places

no more speaking in code

switching for whites is only for the old.

Our time is coming to the tide

all of our trials taken in stride

for now we become wise

consistently exposing the oppressor’s lies.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Niggerati

And on the first day,

The creator took his pen and began to write the anthology of our existence.

Ours ,the first people

The ones in his image

A creator who created multiple copies of himself,

We just happened to be black skinned

And later that black skin is labeled negro

As Spanish as it is

And white as our oppressors are

We took the title.

The Illuminati is a group of individuals who collectively have the power to conquer and control anonymously.

Nigger was the title that was given in a form of hateful speech.

Give black people time and an idea and we can flip and create anything like our father intended.

We are the creatives that move in silence

Placing our wants on the collective creative society. We are the standard

We just happen to be black.

0 notes

Text

Richard Bruce Nugent

Richard Bruce Nugent (July 2, 1906 – May 27, 1987), aka Richard Bruce and Bruce Nugent, was a writer and painter in the Harlem Renaissance. One of many gay artists of the Harlem Renaissance, he was one of few who was out publicly. Recognized initially for the few short stories and paintings that were published, Nugent had a long productive career bringing to light the creative process of gay and black culture.

Biography

Richard Bruce Nugent was born in Washington, DC on July 2, 1906 to Richard H. Nugent, Jr., and his wife Pauline Minerva Bruce. After attending Dunbar High School, he moved to New York after his father's death in 1920. The majority of his life and career took place in Harlem in New York City, and he died on May 27, 1987 in Hoboken, New Jersey.

During his career in Harlem, Nugent lived with writer Wallace Thurman from 1926 – 1928 which led to the publishing of “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade” in Thurman's publication “Fire!!!”. The short story was written in a modernist stream-of-consciousness style, its subject matter was bisexuality and more specifically interracial male desire.

Many of his illustrations were featured in publications, such as “Fire!!!” along with his short story. Four of his paintings were included in the Harmon Foundation's exhibition of Negro artists, which was one of the few venues available for black artists in 1931. His only stand-alone publication, “Beyond Where the Stars Stood Still," was issued in a limited edition by Warren Marr II in 1945. He later married Marr's sister, Grace on December 5, 1952.

His marriage to Grace Marr lasted from 1952 until her suicide in 1969. Nugent's intentions with the marriage were unclear as they were not romantic due to his clearly stated interest in other men. Thomas Wirth, contemporary and personal friend of Richard Nugent claimed that Grace loved Richard and was determined to change his sexuality in “Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance: Selections from the Work of Richard Bruce Nugent” 2002

He attended the Community Planning Conference at Columbia University in 1964 as an invited speaker. The conference was held under the auspices of the Borough President of Manhattan/Community Planning Board 10 and Columbia University. The idea of forming an organization to promote the arts in Harlem emerged from the conference’s Cultural Planning workshop and led to the formation of the Harlem Cultural Council. Nugent took an active role in this effort and attended numerous subsequent meetings. Nugent was elected co-chair (a position equivalent to vice president) of this council. He also served as chair of the Program Committee until March 1967.

Legacy

Nugent's aggressive and honest approach to homoerotic and interracial desire was not necessarily in the favor of his more discreet homosexual contemporaries. Alain Locke chastised the publication “Fire!!!” for its radicalism and specifically Nugent's “Smoke Lilies, and Jade” for promoting the effeminacy and decadence associated with homosexual writers.

Nugent's group of friends, made up of Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Aaron Douglas, Gwendolyn Bennett, and John P. Davis, all frequented "Niggerati Manor," which was where they socialized with each other as well as where the origination of "Fire!!!" was based. As well as his friends, Nugent was also influenced by the likes of Aaron Douglas and Georgia Douglas Johnson. These people's aesthetics were seen in his work. They also helped get his work into various magazines for exposure.

Nugent's work resurfaced in anthologies such as Michael J. Smith's “Black Men/White Men: A Gay Anthology" (1983), and Joseph Beam's interview with Nugent in “In The Life: A Black Gay Anthology” (1986). His work after its resurfacing brought to light the lifestyle of black gay artists during the Harlem Renaissance. His use of codes made much of his work pass unseen by straight contemporaries under the disguise of biblical imagery for example. Nugent bridged the gap between the Harlem Renaissance and the black gay movement of the 1980s and was a great inspiration to many of his contemporaries.

Bibliography

Shadow

My Love

Narcissus

Incest

Who Asks This Thing?

Bastard Song

Sahdji

Smoke, Lilies and Jade

The Now Discordant Song of Bells

Slender Length of Beauty

Tunic with a Thousand Pleats

Pope Pius the Only

On Harlem

On Georgette Harvey

On Gloria Swanson

Lunatique

Pattern for Future Dirges

Popular Culture

Film

As one of the last survivors of the Harlem Renaissance, Nugent was a sought-after interview subject in his old age, consulted by numerous biographers and writers on both black and gay history. He was interviewed in the 1984 gay documentary, “Before Stonewall,” and his work was featured in Isaac Julien’s 1989 film, Looking for Langston.

Brother to Brother is a film written and directed by Rodney Evans and released in 2004. The film debuted at the 2004 Sundance Film Festival before playing the gay and lesbian film festival circuit, with a limited theatrical release in late 2004.The film is concerns an art student named Perry (Anthony Mackie) who befriends an elderly homeless man named Bruce Nugent (Roger Robinson), who turns out to have been an important figure in the Harlem Renaissance. Through recalling his friendships with other important Harlem Renaissance figures such as Langston Hughes, Aaron Douglas, Wallace Thurman and Zora Neale Hurston, Bruce chronicles some of the challenges he faced as a young, black, gay writer in the 1920s. Perry discovers that the challenges of homophobia and racism he faces in the early 21st century closely parallel Bruce's.

Theater

Smoke Lilies & Jade is a Bildungsroman (coming-of-age) play by writer Carl Hancock Rux. Loosely based on Nugent's 1926 short story, "Smoke, Lilies and Jade" (as well as elements of Richard Bruce Nugent's own life) the play concerns the psychological and moral growth of its protagonist Alex as he reflects on his love for a man named "Beauty" and a woman named "Melva", as well as the relationships, injustices and tragedies that eventually befell him and many of the Jazz Age's African American artists and intellectuals. The play was initially commissioned by The Joseph Papp Public Theater and later produced by the CalArts Center for New Performance.

Wikipedia

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Niggerati hands on my shoulder beyond the dirt.

I wonder if Wallace Thurman would of liked Frank. I feel like Dean Blunt would be more up his alley.

0 notes

Photo

Now on http://fabulizemag.com/2018/01/when-zora-neale-hurston-died-alice-walker-bought-her-a-headstone/

When Zora Neale Hurston Died, Alice Walker Bought Her A Headstone

US writer Alice Walker pauses during an interview with the Associated Press in Gaza City, Tuesday, March 10, 2009. Pulitzer Prize-winning U.S. author Alice Walker said a catastrophe has befallen Gaza and that she hopes she and others can help President Barack Obama “see what we see.” Walker, 65, and members of the U.S. anti-war group “Code Pink” toured Gaza this week, including an area destroyed in Israel’s recent war on the territory’s Islamic militant Hamas rulers. (AP Photo/Tara Todras-Whitehill)

Black sisterhood is a remarkable bond that has helped drive our communities for centuries. There is nothing better than sisters looking out for each other. Personally, part of my growing and evolving into a better black woman was to embrace other black women. I am grateful that I grew out of the not wanting to befriend women stage and I recognize my life has become so much better with the number of black women I surround myself with. I am grateful for every black woman/femme/non-gender conforming person that has embraced me, both good and bad to help me unpack my problematic ways and to shine like the star I am meant to be. I read this story about Alice Walker buying Zora’s headstone and the gesture is nothing but love. I hope you enjoy it too.

From the Paris Review:

“Zora!” Alice Walker howled in the cemetery. “I hope you don’t think I’m going to stand out here all day, with these snakes watching me and these ants having a field day.” It was August 1973. Zora Neale Hurston, who was then thirteen years dead, was a mudslinging protofeminist novelist-folklorist-playwright-ethnographer, not to be crossed, and she had climbed to minor literary stardom in the thirties with her accounts of the Southern African American experience, specifically black Southern womanhood. She was, in the words of her friend Langston Hughes, “the most amusing” among New York’s “Niggerati.” She hailed herself as their queen. But Hurston was complicated. “Someone is always at my elbow reminding me that I am the granddaughter of slaves,” she once wrote. “It fails to register depression with me. Slavery is sixty years in the past. The operation was successful and the patient is doing well, thank you.” She declined to recall a single memory of racial prejudice in her autobiography. Her sycophantic attitude toward her white patrons, Red-baiting, and eventual criticism of Brown v. Board of Education had rotted her name. “She was quite capable of saying, writing, or doing things different from what one might have wished,” Walker admitted. But she forgave Hurston. As Hurston herself declared, “How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company?”

And so: nearly a decade before Walker published The Color Purple, a sister masterpiece to Their Eyes Were Watching God, the contributing editor at Ms. magazine stood in weeds up to her waist in Florida while sand and bugs poured into her shoes, looking for Hurston. Walker had flown from Jackson, Mississippi, to Orlando and driven to nearby Eatonville, the prideful all-black town where Hurston was raised, but not, as Walker learned from an octogenarian former classmate—Mathilda Moseley, teller of “woman-is-smarter-than-man” tales in Hurston’s Mules and Men—where she was put under.

Walker’s quest took her to Fort Pierce, on the Atlantic Coast, to the dead end of Seventeenth Street, to the Garden of Heavenly Rest.

“In fact, I’m going to call you just one or two more times,” Walker swore. Hurston was somewhere in the crummy segregated burial ground; trouble was, her grave was unmarked. “Zo-ra!” Walker roared. And, as if Hurston had shoved her, Walker stumbled into a sunken rectangle in the heart of the yard: presumably Zora.

At the local monument maker, Walker clocked a queenly headstone called Ebony Mist. It reminded her of Hurston when she was learning witchcraft at temples in Louisiana, and though Walker dearly wanted it, the issue of lucre obliged her to settle for a modest one—“pale and ordinary, not at all like Zora”—which she had cut with A GENIUS OF THE SOUTH.

I studied cultural anthropology at Orlando’s liberal-arts college, where Hurston was a bona fide heroine. She herself had done her anthropology studies at Columbia University, where she along with Ruth Benedict and Margaret Mead were protégées of Franz Boas, the giant who institutionalized the vital participant-observation method. Papa Boas sent Hurston to Harlem with phrenology calipers to measure the skulls of pedestrians and give lie to the notion of Negro inferiority. She never finished her Ph.D., and turned instead to literature. When she came back down to Florida to do fieldwork, she essentially went AWOL on Boas, though she still shipped him oranges.

One summer, in what was mainly a ruse to dwell with a boyfriend in his parents’ beach house, I fulfilled my chemistry requirement at the local community college. We drove by Hurston countless times—we stopped to coo over manatees in waters minutes from her resting place. But until I, too, tried to look her up in Eatonville, I’d had no clue Hurston was so close by.

When I visited last October, the cemetery’s grass was buzzed down, but the Garden of Heavenly Rest remained dumpy. I offered Hurston a pair of ripe grapefruits. People often leave her balls of citrus, which figured into her fiction. People often leave purple things, too, in recognition, I think, of the Walker connection. The plot was flush with cash, dominos, a rhinestone statement necklace, a pack of cigarettes, a bottle of sparkly red nail polish, and two bottles of Guinness.

Whether this corpse in this sandy earth belonged to Hurston is still uncertain. What’s more, the gravestone is wrong: it reads “1901–1960.” Zora had fibbed on her age and was born a full decade earlier, in 1891. She returned to Fort Pierce at the end of her life, in 1957. Her options had evaporated and she had scraped by, twice divorced, as a chambermaid, office clerk, substitute teacher, a journalist on a murder trial, and, if one of Walker’s sources had it right, a horoscope columnist. She was at work on an uncontracted biography of Herod the Great—a project fourteen years in the pipe—when she had a stroke and passed away in a county welfare home on January 28.

After my visit, I itched to read Hurston again. Her first published story was a ghost story, and when I spotted it collected among Restless Spirits: Ghost Stories by American Women, 1872–1926—branded “feminist, turn-of-the-century American supernatural literature”—#MeToo was stirring and the timing seemed right. But I accidentally shipped the book to my parents’ address in Florida, then had the parcel rerouted to New York City. Once I had it in hand, I put off cracking it open.

Earlier this month, I packed Restless Spirits when I left for Paris during the cyclone bomb. Lo: the plane flew without luggage; my bag did not surface for weeks. As a result, I began leafing the 1996 anthology of twenty-two ghost stories by Hurston, Kate Chopin, Hildegarde Hawthorne, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Edith Wharton, and others on the first anniversary of the Women’s March, which, in Paris, was pissed on by bitter weather and not well-advertised. Near the Eiffel Tower, a crowd of approximately a hundred people carried banners such as ENCORE FÉMINISTES and exhorted American expats to vote absentee in the midterms.

Reading this literature has been no comfort—your spine won’t shiver but your hands will wring. It ran in popular magazines such as Harper’s, Vogue, and The Atlantic over a fifty-year period during which, as the book’s editor remarks, the industrial revolution bent ideologies about the nature and role of being female to more brutal degrees. The short stories are organized into themes: matrimony, motherhood, sexuality, madness, widowhood, and spinsterhood. In them, fearful, enraged, desirous, pained, and restless American women have been made so by a culture we can still recognize today. The editor notes in her introduction that the supernatural was a safe way for the authors to confront their dissatisfaction via allegory. When they wrote about their world, she asks, is it any wonder that the ghosts they conjured, and those who saw, heard, and were able to listen to them were chiefly women?

In fact, “Spunk” (1925), Hurston’s Eatonville-set story about possession, supplies the anthology’s rare male ghost. In it, a gutless hubby manages to comes back to kill his wife Lena’s lover, who had killed him first. Only Lena survives the love triangle. It is pure woman-on-top Hurston, as she lived and breathed: the force who tripped Alice Walker in the cemetery when she dared to shout, “Are you out there?”

#Alice Walker#black women#black writers#feminism#womanism#Zora Neale Hurston#Art#CULTURE#FEATURES#Read & Chill

0 notes

Photo

I’m having an “I’ve got better at home moment” with my multi signed copy of #karawalker dust jackets for niggerati #book (at Bedford–Stuyvesant, Brooklyn)

0 notes

Text

Elucid: Valley of Grace

When he was growing up, Chaz Hall’s parents dragged him to church every Sunday—back-to-back services in the morning, and a third after a brief reprieve at Old Country Buffet. At some point, he started skipping dinner, slinking to the back of the sanctuary, teaching himself how to operate the equipment at the mixing board. Soon he was recording himself, alone in a empty room.

Over the course of the aughts, Hall—aka Elucid—embedded himself in the labyrinthine world of underground rap in New York. His music can be difficult to find: much of it came out under short-lived or one-off artist names, as collaborations with producers, other rappers, or both. But in the past few years, Elucid’s name has come to the forefront, both as a solo artist and as one-half of the duo Armand Hammer, with his Backwoodz Studioz label mate, billy woods.

Elucid’s music can also be difficult, or at least seem unapproachable. It’s full of knotty, dense writing and supremely technical passages. Yet unlike plenty of underground rappers (and major-label artists, for that matter), he’s uniquely attuned to melody and song structure. Even when he breaks convention, his intent seems to be clear; his delivery is an intoxicating blend of the gruff and guttural and something more melodic. His LP from last year, Save Yourself, was a collage of heartbreak and ambition that takes dozens of listens to properly unpack; it grappled with love, gentrification, and the corrosive nature of religious institutions.

His latest work, a half-hour dispatch called Valley of Grace, has songs titled “self care is a revolutionary act” and “strength is admired humanity is denied.” Where Save Yourself was in certain ways inextricable from New York (Elucid has made camp in Brooklyn, Queens, and elsewhere over the last couple of decades), Valley of Grace was written and recorded in Johannesburg and Cape Town, and taps into something more ethereal. It’s thoughtful, considered, and among the most ambitious rap records to come out this year.

“Colonizers corpse,” for example, sounds straightforward and up-tempo, but is written in a way that throws Elucid into a series of scenes where the spiritual stakes keep increasing: at first, roadside vendors are running after escaped chickens with cleavers, later a “gunned-down” child’s soul runs with the same desperation. He ends the song with “Self-appointed poet laureate of the Niggerati/hard copy/I am not my body,” allowing those words to give way to forty seconds of ear-splitting distortion that open the next track before hopping back in: “Watching America burn from distant shores/I learned to walk hot coals before I left the East coast.”

Valley also features some of Elucid’s most adventurous production: see “talk disruptive for me,” which sounds like the climaxes of three different movies played on top of one another. “she’d rather be a cyborg than a goddess,” which accounts for fully one-third of the tape’s running time, flits back and forth between (and occasionally merges) cold, industrial textures with warmer tones, the latter coming via very lo-fi samples.

Along with frequent appraisals of America’s current state and deeply entrenched hypocrisy on race, the topic that Elucid returns to most is the state of his body. From the hot coals under his feet to the “clear and present danger” to his physical form (“no release”), Valley of Grace frequently feels, by its very existence, like an act of defiance. Perhaps he says it best himself: “I’m no prisoner/Your indifference and silence speaks volumes/I pray the wrath of my ancestors surrounds you.” With this record, Elucid has taken sharp, maximalist writing, music that’s very nearly avant-garde, and distilled each down to its core elements.

0 notes

Photo

#langston hughes#poetry#zora neale hurston#literati#niggerati#harlem#beyonce#nicki minaj#kim kardashian#kanye west#taylor swift#janet jackson#oscarssowhite#oscars#taraji p. henson#empire

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

CARTER Magazine FIRE!!! Issue

"Negro writers, just by being black, have been on the blacklist all our lives. Do you know that there are libraries in our country that will not stock a book by a Negro writer, not even as a gift? There are towns where Negro newspapers and magazines cannot be sold except surreptitiously. There are American magazines that have never published anything by Negroes. There are film studios that have never hired a Negro writer. Censorship for us begins at the color line."

Langston Hughes

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This is the "Niggerati Manor." Kind of a small building, but it housed the cultural and intellectual elite of the Harlem Renaissance. These were individuals who were black but weren't limited by their skin color during the time period like other black individuals.

4 notes

·

View notes