#naval engagements of Guadalcanal

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

1943 04 07 Wildcat fury - David Gray

On April 7, 1943, a formation of Japanese fighters and dive-bombers was headed toward Tulagi Harbor. Scrambled from nearby Guadalcanal, USMC 1st Lt. James E. Swett of VMF-221 led his four F4F Wildcat division into the fray. Swett pursued and shot down three D3A2 Val enemy bombers before leveling out. Moments later, his Wildcat was hit by friendly fire. In spite of his damage, Swett dogged the fleeing Vals, scoring four more confirmed kills, and one probable, becoming an ace in his first combat mission. For this action, Lt. Swett was awarded the Medal of Honor.

"For extraordinary heroism and personal valor above and beyond the call of duty, as division leader of Marine Fighting Squadron 221 with Marine Aircraft Group 12, 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, in action against enemy Japanese aerial forces in the Solomons Islands area, 7 April 1943. In a daring flight to intercept a wave of 150 Japanese planes, 1st Lt. Swett unhesitatingly hurled his 4-plane division into action against a formation of 15 enemy bombers and personally exploded 3 hostile planes in midair with accurate and deadly fire during his dive. Although separated from his division while clearing the heavy concentration of antiaircraft fire, he boldly attacked 6 enemy bombers, engaged the first 4 in turn and, unaided, shot down all in flames. Exhausting his ammunition as he closed the fifth Japanese bomber, he relentlessly drove his attack against terrific opposition which partially disabled his engine, shattered the windscreen and slashed his face. In spite of this, he brought his battered plane down with skillful precision in the water off Tulagi without further injury. The superb airmanship and tenacious fighting spirit which enabled 1st Lt. Swett to destroy 7 enemy bombers in a single flight were in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service."

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

2nd September 1937. First flight of the Grumman XF4F fighter, which would become known as the Wildcat. Its performance was initially inferior to the rival Brewster Buffalo, and the aircraft required an extensive redesign before being put into production. Despite this unpromising beginning, the Wildcat would prove crucial in the early stages of the Pacific war. Though less manoeuvrable than the Japanese Zero, it was well armed, rugged and a capable adversary in the hands of a skilled pilot.

The Wildcat’s first combat sorties were actually flown by the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm. Named Martlet in British use until 1944, the type’s first victory was a Junkers 88 over Scapa Flow on Christmas Day 1940. Martlets went on to serve successfully on the first Royal Navy escort carrier, HMS Audacity, in 1941. They continued in this role until the end of the war, scoring their final victories in Fleet Air Arm service by shooting down four Bf 109s in March 1945.

Wildcats first flew in combat against the Japanese during the attempt to take Wake Island in early December 1941. Four Marine F4Fs mounted a heroic defence, breaking up several air attacks as well as sinking a destroyer and submarine with 100lb bombs before the island finally fell on 23rd December. Wildcats served in all the key early engagements of the Pacific war, including Coral Sea, Midway and the defence of Guadalcanal.

Wildcats quickly established a reputation for toughness, able to absorb far more punishment than their Japanese opponents, and had an impressive kill/loss ratio. Wildcats were credited with destroying over 1,000 Japanese aircraft for 178 aerial losses, 24 to anti-aircraft fire, and 49 to operational causes. One Navy and seven Marine Corps pilots would earn the Medal of Honor in Wildcats.

In early 1943, Wildcat production was taken over by General Motors under the designation FM-1 and later the improved FM-2. Though replaced by the more powerful Hellcat on American fleet carriers during that year, the Wildcat’s small size and light weight made it ideal for use on escort and light carriers. With the addition of folding wings, they were well suited to the limited hangar and deck space available.

As in Royal Naval service, they remained in use until the end of the war. For example, during the battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944, Wildcats mounted strafing runs against Japanese warships, helping to buy time for their parent escort carriers to escape.

Pictured:

1) First prototype Grumman XF4F-2 in flight. Note the cowling machine guns, forward radio antenna mast and telescopic gunsight, none of which featured on production models.

📷 thisdayinaviation.com

2) Grumman Martlet of 888 Squadron NAS warming up on board HMS Formidable prior to takeoff.

📷 IWM (A 11640)

3) Wrecked Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat fighters of Marine Fighting Squadron 211 (VMF-211), photographed by by the Wake airstrip sometime after the Japanese captured the island on 23rd December 1941. The plane in the foreground, 211-F-11, was flown by Captain Henry T. Elrod during the 11th December attacks that sank the Japanese destroyer Kisaragi. Damaged beyond repair at that time, 211-F-11 was subsequently used as a source of parts to keep other planes operational. Elrod received a posthumous Medal of Honor after leading a beach defence unit during the final Japanese assault.

📷 NHHC 80-G-179006

4) FM-2 Wildcat over the escort carrier USS Santee during the Leyte landings on 20th October. Santee would survive a kamikaze attack and a torpedo hit from a Japanese submarine 5 days later.

📷 NHHC 80-G-287594

@JamieMctrusty via X

#wildcat#martlet#grumman aviation#Goodyear aviation#navy#aircraft#fighter#aviation#us navy#carrier aviation#ww2

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

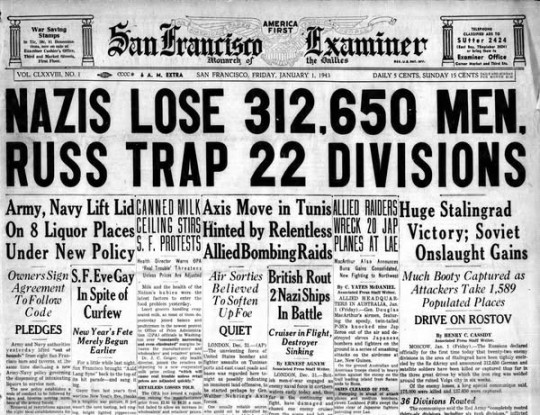

Turning the Tide of War

As New Year’s Day dawned on Mare Island in 1943, over 40,000 workers were dedicated to building and maintaining warships. Just over a year earlier, the nation had been shaken by the Japanese surprise attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, which marked the beginning of a devastating conflict that would claim the lives of more than 300 U.S. military personnel and civilians each day for the next four years.

Despite the ongoing tragedy of war, by January 1, 1943, the entire industrial, scientific, economic, and civic capacity of the nation was mobilized, and complacency was no longer an option. While the fight against the Axis Powers—Germany, Japan, and Italy, who had formed the "Berlin Pact"—was far from over, the tide was beginning to turn.

In the Pacific, a significant battle had just concluded with a defeat for the Japanese forces. In a remarkable decision made the day before, Emperor Hirohito authorized the withdrawal of Japanese troops from Guadalcanal, marking the beginning of the collapse of Japan's "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere," a term used to describe their imperial ambitions through military conquest.

In early 1942, Allied intelligence had discovered that the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) was constructing a large airfield on Guadalcanal, an island approximately 1,000 miles from Australia that few had ever heard of. If this airfield became operational, Japanese long-range bombers could threaten vital sea lanes between the United States, Australia, and New Zealand. In response, U.S. Admiral Ernest King, Commander in Chief of the United States Fleet, ordered the invasion of the island to prevent the Japanese from using the airstrip. This decision set the stage for a fierce battle on land, sea, and air.

The battle commenced on August 7, 1942, when Allied forces, primarily from the 1st Marine Division, landed on Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and the Florida Islands in the Solomon Islands, facing only light resistance initially. However, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters quickly responded by dispatching the 17th Army to retake Guadalcanal. The IJN also viewed Guadalcanal as an opportunity to engage in a decisive naval battle, which their doctrine emphasized as the best way to defeat the U.S. Navy. Orders were issued to converge on the island, and the Japanese General warned his troops that this would be a do-or-die battle that would determine the fate of the Japanese Empire. He was correct, and it would take six months and countless lives before the outcome of the Guadalcanal campaign was decided.

The land and naval battles of Guadalcanal became some of the bloodiest of the war and remain legendary in U.S. naval and Marine Corps history. The campaign concluded with a U.S. victory, despite initial feelings of abandonment among the Marines when the Navy left them without support after the landing. The naval battles were particularly brutal, with two heavy cruisers built at Mare Island—the USS Chicago (CA-29) and the USS San Francisco (CA-38)—playing crucial roles in the ongoing struggle. After initially leaving the Marines to fend for themselves, the Navy decided to send available assets on what amounted to a suicide mission, pitting five U.S. cruisers and eight destroyers against a superior Japanese task force led by battleships.

On the night of November 13, 1942, the San Francisco engaged the vastly superior Japanese fleet off Guadalcanal in one of the most intense close-quarters naval battles of World War II. The San Francisco endured 45 direct hits and sustained severe damage while sinking one Japanese ship and inflicting significant damage on two others, including a battleship. With half of her crew either killed or wounded, the remaining sailors displayed remarkable courage as they tended to the injured and executed damage control. Thanks to their efforts, the severely damaged San Francisco was able to return to Mare Island Naval Shipyard for repairs, narrowly escaping further disaster. As she limped away from Guadalcanal, two torpedoes were launched from a Japanese submarine, both of which missed their target. However, one struck the cruiser USS Juneau (CL-52), resulting in a catastrophic explosion that split the ship in two within seconds. Fearing further attacks and mistakenly believing there were no survivors, the remaining fleet departed, leaving over 100 men struggling in the water. Days later, only 18 of those men would be found alive, having succumbed to their injuries, shark attacks, and exposure.

When the San Francisco finally returned to Mare Island for repairs, the battle for Guadalcanal had concluded, and combined with the Battle of Midway, the war in the Pacific had reached a pivotal turning point. Although two and a half years of Bloody fighting lay ahead, the tide had indeed begun to turn.

Dennis Kelly

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#vallejo#world war 2#world war ii#world war two#california#Guadalcanal#Marines#Juneau#Sharks

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

World War II, an epochal conflagration that transpired from 1939 to 1945, epitomizes one of the most cataclysmic and transformative periods in modern history. This global conflict, characterized by its unprecedented scale and the mobilization of vast military resources, engendered profound geopolitical ramifications and irrevocably altered the trajectory of international relations. The genesis of this multifaceted war can be traced to the interwar period, wherein the Treaty of Versailles imposed onerous reparations and territorial concessions upon the Weimar Republic, engendering a milieu of economic despondency and political instability. The ascendance of totalitarian regimes, notably Adolf Hitler's National Socialist German Workers' Party, catalyzed aggressive expansionist policies that culminated in the invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. This incursion prompted the Allied powers, primarily the United Kingdom and France, to declare war on Germany, thereby igniting a conflagration that would engulf the globe. The conflict was characterized by a series of pivotal military engagements, including the Battle of Britain, the Operation Barbarossa, and the cataclysmic confrontations on the Eastern Front. The latter, marked by the brutal Siege of Stalingrad, epitomized the ferocity of the conflict and the staggering human cost, with millions of combatants and civilians perishing in the maelstrom of warfare. The utilization of mechanized warfare and aerial bombardment revolutionized military strategy, while the advent of total war necessitated the mobilization of entire societies for the war effort. Simultaneously, the Pacific Theater witnessed a protracted struggle between the United States and the Empire of Japan, precipitated by Japan's imperial ambitions and the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The ensuing battles, including the pivotal engagements at Midway and Guadalcanal, underscored the strategic significance of naval power and air superiority in modern warfare. The Holocaust, an abhorrent manifestation of genocidal ideology, represents one of the most egregious atrocities of the war. The systematic extermination of six million Jews, alongside millions of other marginalized groups, underscores the moral depravity that can arise from unchecked totalitarianism and xenophobia. This dark chapter in human history necessitates a profound reckoning with the ethical implications of state-sponsored violence and the imperative of safeguarding human rights. The culmination of World War II was marked by the unconditional surrender of the Axis powers in 1945, following the cataclysmic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The deployment of atomic weaponry not only precipitated Japan's capitulation but also heralded the dawn of the nuclear age, engendering a new paradigm of international relations predicated on the doctrine of mutually assured destruction. In the aftermath of the war, the establishment of the United Nations sought to foster international cooperation and prevent the recurrence of such a devastating conflict. The geopolitical landscape was irrevocably altered, with the emergence of the United States and the Soviet Union as superpowers, setting the stage for the ensuing Cold War.

0 notes

Text

Events 11.13 (before 1970)

1002 – English king Æthelred II orders the killing of all Danes in England, known today as the St. Brice's Day massacre. 1093 – Battle of Alnwick: in an English victory over the Scots, Malcolm III of Scotland, and his son Edward, are killed. 1160 – Louis VII of France marries Adela of Champagne. 1642 – First English Civil War: Battle of Turnham Green: The Royalist forces withdraw in the face of the Parliamentarian army and fail to take London. 1715 – Jacobite rising in Scotland: Battle of Sheriffmuir: The forces of the Kingdom of Great Britain halt the Jacobite advance, although the action is inconclusive. 1775 – American Revolutionary War: Patriot revolutionary forces under Gen. Richard Montgomery occupy Montreal. 1833 – Great Meteor Storm of 1833. 1841 – James Braid first sees a demonstration of animal magnetism by Charles Lafontaine, which leads to his study of the subject he eventually calls hypnotism. 1851 – The Denny Party lands at Alki Point, before moving to the other side of Elliott Bay to what would become Seattle. 1864 – American Civil War: The three-day Battle of Bull's Gap ends in a Union rout as Confederates under Major General John C. Breckinridge pursue them to Strawberry Plains, Tennessee. 1887 – Bloody Sunday clashes in central London. 1901 – The 1901 Caister lifeboat disaster. 1914 – Zaian War: Berber tribesmen inflict the heaviest defeat of French forces in Morocco at the Battle of El Herri. 1916 – World War I: Prime Minister of Australia Billy Hughes is expelled from the Labor Party over his support for conscription. 1917 – World War I: beginning of the First Battle of Monte Grappa (in Italy known as the "First Battle of the Piave"). The Austro-Hungarian Armed Forces, despite help from the German Alpenkorps and numerical superiority, will fail their offensive against the Italian Army now led by its new chief of staff Armando Diaz. 1918 – World War I: Allied troops occupy Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire. 1922 – The United States Supreme Court upholds mandatory vaccinations for public school students in Zucht v. King. 1927 – The Holland Tunnel opens to traffic as the first Hudson River vehicle tunnel linking New Jersey to New York City. 1940 – Walt Disney's animated musical film Fantasia is first released at New York's Broadway Theatre, on the first night of a roadshow. 1941 – World War II: The aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal is torpedoed by U-81, sinking the following day. 1942 – World War II: Naval Battle of Guadalcanal: U.S. and Japanese ships engage in an intense, close-quarters surface naval engagement during the Guadalcanal Campaign. 1947 – The Soviet Union completes development of the AK-47, one of the first proper assault rifles. 1950 – General Carlos Delgado Chalbaud, President of Venezuela, is assassinated in Caracas. 1954 – Great Britain defeats France to capture the first ever Rugby League World Cup in Paris in front of around 30,000 spectators. 1956 – The Supreme Court of the United States declares Alabama laws requiring segregated buses illegal, thus ending the Montgomery bus boycott. 1965 – Fire and sinking of SS Yarmouth Castle, 87 dead. 1966 – In response to Fatah raids against Israelis near the West Bank border, Israel launches an attack on the village of As-Samu. 1966 – All Nippon Airways Flight 533 crashes into the Seto Inland Sea near Matsuyama Airport in Japan, killing 50 people. 1969 – Vietnam War: Anti-war protesters in Washington, D.C. stage a symbolic March Against Death.

0 notes

Text

Cassin Young (March 6, 1894 – November 13, 1942) was a captain in the United States Navy who received the Medal of Honor for his heroism during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Biography

Young was born in Washington, D.C., on March 6, 1894. At the age of two he moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where his father operated a drug store.[1] After graduation from the U.S. Naval Academy on June 3, 1916, he served on the battleship USS Connecticut (BB-18) into 1919. He attended submarine school in 1919 and then spent several years in subs. During that period, he served on the USS R-22 (SS-99) and USS R-3 (SS-80). In 1921, he and his family returned from Panama and he assisted in outfitting the USS S-51. In January 1922, he served in Naval Communications on the staff of Commander Submarine Divisions, Battle Fleet, and at the Naval Academy.

During 1931 to 1933, Lieutenant Commander Young served on the battleship USS New York (BB-34). He was subsequently awarded command of the destroyer USS Evans (DD-78) and was assigned to the Eleventh Naval District from 1935 to 1937. After promotion to the rank of Commander, he commanded Submarine Division Seven and was stationed at Naval Submarine Base New London, in Groton, Connecticut.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, he was commanding officer of the repair ship USS Vestal (AR-4), which was badly damaged by Japanese bombs and the explosion of the battleship USS Arizona (BB-39). Commander Young rapidly organized offensive action, personally taking charge of one of Vestal's anti-aircraft guns. When Arizona's forward magazine exploded, the blast blew Young overboard. Although stunned, he was determined to save his ship by getting her away from the blazing Arizona. Swimming through burning oil back to Vestal, which was already damaged and about to be further damaged, Young got her underway and beached her, thus ensuring her later salvage. His heroism was recognized with the Medal of Honor.

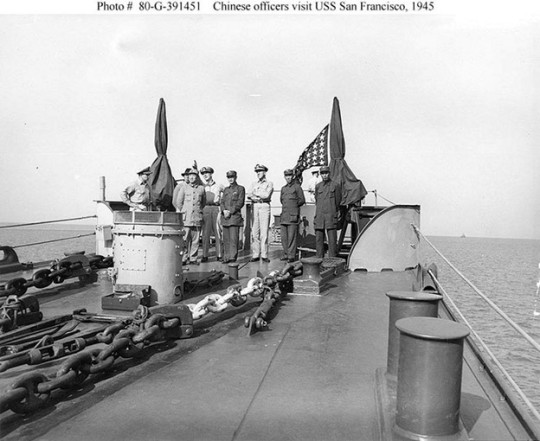

Promoted to Captain in February 1942, he took command of the heavy cruiser USS San Francisco (CA-38) on November 9, 1942.[2] On November 13, 1942, during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, he guided his ship in action with a superior Japanese force and was killed by enemy shells while closely engaging the battleship Hiei. Captain Young was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross for his actions during the campaign and San Francisco received the Presidential Unit Citation.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pacific War 18 - Bloody Nights of Guadalcanal

Indecisive clashes around Guadalcanal had grated on both sides. During November, both the Japanese and the Americans decided to mount a surprise attack with strong forces in an effort to reach decision. These forces were even put into motion at about the same time, on 11th November 1942., and included warships, transport ships, submarines and aircraft. Long columns of ships criss-crossed the open…

View On WordPress

#13th November 1942#1942#Friday the 13th#Guadalcanal#naval battles of Guadalcanal#naval engagements of Guadalcanal#November 1942

1 note

·

View note

Text

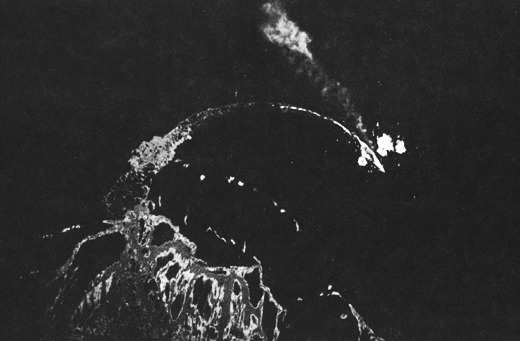

"Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses of the 11th Bombardment Group based at Espiritu Santo bomb the damaged Japanese Battleship Hiei (比叡, Mount Hiei) north of Savo Island on November 13, 1942. Hiei, which was damaged in the 1st engagement of the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal hours earlier, appears to be trailing fuel."

source

#Japanese Battleship Hiei#Hiei#Kongo Class#Japanese Battleship#dreadnought#battleship#warship#ship#boat#Battle of Guadalcanal#November#1942#World War II#World War 2#WWII#WW2#imperial japanese navy#IJN#my post#Kongō Class

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

If I'm looking for some past millitary campaigns to compare and contrast to what a near term great power conflict might look like in the Pacific do you have any recommendations? Do you think Douglas McArthur's campaign in the Pacific would be a useful analogy to try and project a trajectory if things heat up in the Pacific during the next few years?

If you're looking for near-peer naval engagement, you might want to try the early Pacific campaigns in the Second World War. The Allies could far outstrip Japan in production of both naval equipment and fuel, but with the early campaigns, Japan had lots of experience for their navy and their naval airforces. However, advances in submarine technology haven't quite seen them act outside of training and drills - most post-WW2 submarine conflicts have seen limited use and engagement. Given the increasing advantages of satellite reconnaissance and surface-to-ship/ship-to-ship missiles, submarines will have an incredibly powerful role in any naval conflict

Similarly, the long distances between resupply makes me think of the grinding campaigns of Guadalcanal. In the event of a large-scale war between the West and China in the Pacific, much of the war materiel from the EU or the USA would take a long time and potentially be vulnerable to convoy interdiction, with a vicious air war from staging areas on land and games of "hunt-the-carrier" further in the middle of the Pacific.

Thanks for the question, Luke.

SomethingLikeALawyer, Hand of the King

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

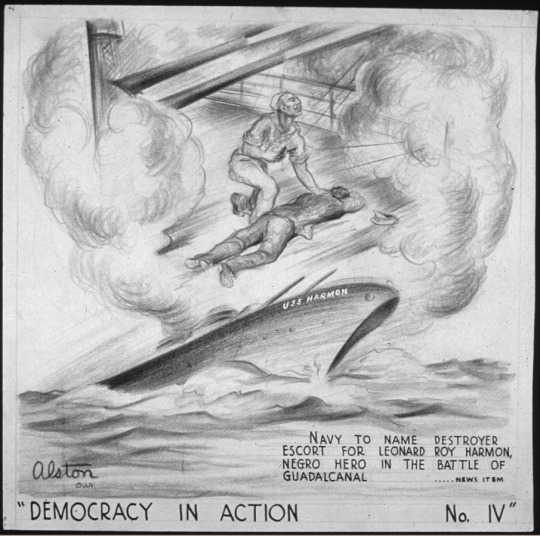

This Week in History: Leonard Roy Harmon, WWII hero

During this week in 1943, USS Harmon is commissioned. It was the first U.S. Navy warship to be named after a black American. The destroyer was named after Leonard Roy Harmon, a sailor who gave his life during World War II.

Harmon was a native Texan who enlisted with the United States Navy and served aboard USS San Francisco as a mess attendant. Yes, sadly, at that point in our history, he was limited in the roles that he could play aboard ship. Nevertheless, it seems that he worked hard and excelled. He was soon promoted to mess attendant first class.

Unfortunately, that would prove to be his final assignment—but it would NOT be his final mark upon the Navy. 😉

Harmon was with San Francisco in 1942 when that vessel became engaged in the critical Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. The Japanese were taking one last swipe at regaining an airfield that they’d lost in the Solomon Islands. Fortunately, Allied forces would manage to defeat the effort.

And Harmon was in the thick of it.

On November 13, 1942, San Francisco was under heavy attack. Harmon was sent above deck to help the pharmacist’s mates. Their task? Locate the wounded and help them to the lower decks. Historian James D. Hornfischer describes the scene that would have faced Harmon: “Ladders were blown away throughout the ship, hatches jammed, and the threat of shrapnel, fire, and flood all-encompassing. Moving up and down from below to the boat deck, and then carrying the wounded back to fantail, was exhausting . . . .”

The story continues at the link in the comments.

#tdih#otd#this day in history#history#history blog#world war ii#wwii#african american history#us navy#naval history#sharethehistory

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

• Chūichi Nagumo

Chūichi Nagumo born March 25th, 1887 in Yonezawa, Yamagata Japan. Was a Japanese admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) during World War II and onetime commander of the Kido Butai (the carrier battle group). He graduated from the 36th class of the IJN Academy in 1908, with a ranking of 8 out of a class of 191 cadets. As a midshipman, he served in the protected cruisers Soya and Niitaka and the armored cruiser Nisshin. In 1910 he received a promotion to ensign.

Nagumo graduated from the Naval War College, and was promoted to lieutenant commander in 1920. His specialty was torpedo and destroyer tactics. He became a commander in 1924. From 1925 to 1926, Nagumo accompanied a Japanese mission to study naval warfare strategy, tactics, and equipment in Europe and the United States. After serving in administrative positions from 1931 to 1933, he assumed command once again in 1933 to 1935. He was promoted to rear admiral on November 1st, 1935.

On April 10th, 1941, Nagumo was appointed commander-in-chief of the First Air Fleet, the IJN′s main carrier battle group, largely due to his seniority. Many contemporaries and historians have doubted his suitability for this command, given his lack of familiarity with naval aviation. By this time, he had visibly aged, physically and mentally. Physically, he suffered from arthritis, and mentally, he had become a cautious officer who carefully worked over the tactical plans of every operation he was involved in. Despite his limited experience, he was a strong advocate of combining sea and air power although he was opposed to Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto's plan to attack the United States Navy Naval Station Pearl Harbor. While commanding the First Air Fleet, Nagumo oversaw the attack on Pearl Harbor, but he was later criticized for his failure to launch a third attack, which might have destroyed the fuel oil storage and repair facilities.

He also fought well in the early 1942 campaigns, obtaining success as a fleet commander at the Bombing of Darwin and at the Indian Ocean raid on the British Eastern Fleet. The Battle of Midway, in June 1942, brought Nagumo's near-perfect record to an end. The First Air Fleet lost four carriers during the turning point of the Pacific War, and the massive losses of carrier aircraft maintenance personnel would prove detrimental to the performance of the IJN in later engagements. Afterwards, Nagumo was reassigned as commander-in-chief of the Third Fleet and commanded aircraft carriers in the Guadalcanal campaign, although there his actions were largely indecisive and drained much of Japan's maritime strength.

On November 11th, 1942, Nagumo was reassigned to Japan, where he was given command of the Sasebo Naval District. He transferred to the Kure Naval District in June 1943. From October 1943 to February 1944, Nagumo was again commander-in-chief of First Fleet, which was by that time largely involved in only training duties. As Japan's military situation deteriorated, Nagumo was deployed on March 4th, 1944 for the short-lived command of the Central Pacific Area Fleet in the Mariana Islands. The Battle of Saipan began on June 15th, 1944. During which on July 6th, Nagumo killed himself with a pistol to the temple rather than the traditional seppuku. His remains were recovered by the U.S. Marines in the cave where he spent his last days as the Japanese commander of Saipan.

Nagumo's grave is located at the Ōbai-in sub-temple of Engaku-ji in Kanagawa, next to the grave of his son, Susumu Nagumo, who was killed in battle aboard the destroyer Kishinami on December 2nd, 1944.

#military#history#world war ii#second world war#world war 2#wwii#japanese history#naval history#imperial japan#admirals#historical figures#biography

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Message in honor of the 74th anniversary of the beginning of the Battle of Iwo Jima and the ultimate and final sacrifice of Gunnery Sergeant John Basilone, USMC

Ladies and gentlemen, to all the people of the United States of America, to all our remaining living veterans of the Second World War of 1939-1945 and of all conflicts past and present and their families, to our veterans, active servicemen and women, reservists and families of the entire United States Armed Forces, and to all the uniformed military and civil security services of the Allied combatants of this conflict, to all the immediate families, relatives, children and grandchildren of the deceased veterans, fallen service personnel and wounded personnel of our military services and civil uniformed security and civil defense services, to all our workers, farmers and intellectuals, to our youth and personnel serving in youth uniformed and cadet organizations and all our athletes, coaches, judges, sports trainers and sports officials, and to all our sports fans, to all our workers of culture, music, traditional arts and the theatrical arts, radio, television, digital media and social media, cinema, heavy and light industry, agriculture, business, tourism and the press, and to all our people of the free world:

As the whole world remembers among others the formation of the modern Mexican Army in 1913, the Russian emancipation reforms of 1861, and the death on this day of the great father of Bulgarian Independence, Vasil Levski, in 1873, as well as the 1879 invention of the phonograph by Thomas Edison, the Enigma tornado outbreak of 1884, the commencement of the naval segment of the Dardanelles Campaign in 1915, the signing of the controversial Executive Order 9066 and the Bombing of Darwin, Australia, in 1942 the beginning of the Battle of Kasserine Pass in 1943 and on this day in 1985 the national premiere in the UK of the BBC’s premier primetime drama EastEnders, today, just as in past years, and in these changing times in our world of today, as one united people of the United States of America and of our free world, we mark on this very day the seventy fourth year anniversary of the beginning of the historic battle of Iwo Jima, which began on this day in 1945, and which would be one of the biggest battles ever to be fought by the United States Marine Corps in the Pacific Theater of Operations of the Second World War, and one of the greatest in its history of over 244 years.

The historic battle whose beginning we honor today is the day in which one of the greatest heroes of our Marine Corps was killed in action. As the waves of Marines of the 5th Marine Division landed in the sands of Iwo Jima 74 years ago by the thousands under the leadership of General Holland Smith, commander of the V Amphibious Corps, among those who perished on that day was the hero of the historic battle of Guadalcanal, who previously served in the Philippines as a soldier of the United States Army and the first Marine NCO recipient of the Medal of Honor, Gunnery Sergeant John Basilone, who was killed by a mortar shot in the vicinity of the Japanese airfield in the island in the presence of his fellow Marines while performing clearing operations to remove enemy presence in the airfield. His ultimate sacrifice made him posthumously the first ever Marine to earn both the Medal of Honor and the Navy Cross in history for his service and determination in fulfilling at the cost of his life the fundamental mission of the Corps in ensuring the defense of the fatherland and the free peoples of the world through amphibious land, air and sea conventional and unconventional operations. (His immortal sacrifices will always be remembered as being featured in the 2010 HBO miniseries The Pacific, being played by no less than Jon Seda, together with actors Ben Esler and Dwight Braswell in the roles of the two men who fought with him in Iwo, Chuck Tatum and Steve Evanson, all from the same battalion – the 1st Battalion, 27th Marine Regiment, which was deployed as part of the division in that island.)

Gunny Basilone was one of the many Marines, Sailors and Coast Guardsmen who on this very day of the opening salvo of the battle for the liberation of Iwo Jima from the Japanese perished in these sandy beaches, whose sacrifice helped America and her allies open the doors for the liberation of the Japanese home islands from the menace of imperialism, militarism and totalitarian governance. The deaths of thousands of these American soldiers of our Armed Forces in the Pacific and China-Burma-India Theaters of Operations of the Second World War serve as a reminder of the importance of service in our armed forces for the fulfillment of its principal responsibilities to the nation and her people: the defense of our independence and territorial integrity, protection of national interests abroad and of global democracy and the sustainment of traditions and ideals of liberty fought by the first generations who waged the great Revolutionary War and other conflicts of the past. The heroic deaths of many of our men and women in the military in engagements at home and abroad in times of peace and war, together with the actions of assistance of our armed forces in response to natural and man-made disasters, thus, are proof of the strong bond of friendship of the armed forces of the Union not just with our people but with the peoples of the free nations of our world, especially our partners with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

As the great FADM Chester Nimitz had put it in his own words, “Uncommon valor was a common virtue” among the hundred thousand Marines of V Amphibious Corps who served there in this, one of the biggest combat operations that the United States Marine Corps undertook in the Second World War in the Pacific Theater of Operations and one of the biggest victories of the Allies in this part of the world. His words are forever recorded in the Arlington National Cemetery’s Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia, the very monument made on the basis of the historic photograph of the Iwo Jima flag raising that today, after 65 years since its historic inauguration, proudly stands over the Arlington fields and the graves of so many Marines over the centuries who even at the cost of their lives, served faithfully always to their country and people, and honoring the 244 years of long and faithful service of the United States Marine to the people and government of the United States of America and to all the millions of people of the free world. In these changing times, by recalling what has happened 74 years ago which began on this very day, we never forget to remember the heroic actions done during the days of the Iwo Jima Campaign and most especially the thousands who perished in this tiny island for the sake of the freedoms, dreams and aspirations not just of the people of the United States of America but also of all the people of the free world. Indeed, a huge price was paid by the blood shed by these Marines and Navy Corpsmen, together with their fellow soldiers, sailors, Coast Guardsmen and airmen, in the victory won in this battle and in countless others throughout this long war, together with fellow soldiers, sailors and airmen from fellow armed forces of the combatant Allied countries.

The deaths of not only Gunnery Sergeant John Basilone but of the thousands of soldiers, Marines, sailors, airmen and Coast Guardsmen in Iwo Jima and in all other battles of this war, including 3 of the 6 Marines of the division who raised the flag of our country in Mount Suribachi on February 23, 1945, and of the 12 Marines who were posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for their heroic courage and bravery at the cost of their lives in Iwo Jima, are a constant reminder to millions of Americans of the patriotic, democratic and internationalist duties of our hundreds of thousands of men and women who are serving today in our Armed Forces, the National Guard and our state defense forces and naval militias, and who continue the fighting traditions of our grandfathers and grandmothers who fought in every conflict since the beginning of our nation, as well as in deployments abroad. The bravery, courage, audacity and fighting determination of our men and women in military service have had shown the world that the United States and her people, together with her loyal allies overseas, are prepared always to respond to the cries of help and suffering of the millions suffering under totalitarian and evil governments in the world as well as to victims of natural and man-made calamities as well as of global terrorism. Thus, we, the brave people of our great country, will forever and always remember the memory of these the fallen men and women of our armed forces who have fallen in the line of duty at home and abroad forever carrying the responsibility of being the guardians and defenders of our independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity, as well as of international democracy against false and evil ideologies. Their sacrifice and hard work serve as an inspiration for our people to make their contributions to the life and wellbeing of our people, the sustainment of our culture and the arts, the progress of our economy and the consolidation of our sporting traditions. For as a superpower country, with strong armed forces and stronger strides in all sectors of society, these cannot be possible without the struggles and hard work done by all our people, including those in the armed services and our first responders in our local communities.

Ladies and gentlemen, people of the United States of America and the people of our free world:

Today, as we honor the 74th year anniversary of the historic beginning of the battle of Iwo Jima and the death of one of the greatest heroes of our United States Marine Corps, we remember the brave sacrifices of the thousands of soldiers, Marines, sailors, airmen and Coast Guardsmen of our Armed Forces who perished in the line of duty during the long battle for the liberation of Iwo Jima from the armed forces of the Empire of Japan, whose spirit of determination, courage, patriotism, bravery, audacity and friendship, with loyalty, obedience to the law and to authority and discipline in the midst of the field of battle, have paved the way for our victorious armed forces, together with those of our allies, to win the final victory over the Axis Powers in all theaters of the Second World War, including in the Pacific and East Asia. The heroic victory won in Iwo Jima as well as in other parts of the world during this turbulent time of our history is one worthy of being remembered by the generations of today and by the future generations, for it is important that we honor and commemorate the service of millions under the banner of our Armed Forces in the road towards the final victory over the Axis Powers, in order that we continue the heritage of defending our independence and liberty against all forms of domestic and international aggression.

As we think of the tens of reminding living veterans of the battle who live among us today, we once again make our commitment to ensure that for generation upon generation the sacrifices made by our armed forces in battles past and present for the defense of our nation and people and of our interest abroad as well as for the protection of our way of life and traditions will never be forgotten and sustained by the coming generations, who depend on the future generations of men and women who will be joining the ranks of our armed forces, who will continue the legendary traditions of the earlier generations of heroes – the struggle for the defense and protection of our country and people and for its continued existence as the beacon of hope and liberty in our world of today, especially of the men and women who today serve in the ranks of the United States Marine Corps.

In conclusion, as we remember the fallen of the great battle of Iwo Jima and forever remember the heroic campaign that opened the road to the victory in the Pacific, may we forever cherish the legacy they left behind to our nation and people, uphold their memory of service in the defense of our freedom and independence, and united under our great flag, march forward with our armed forces on the road on realizing our shared dreams of a better and brighter tomorrow for our generations to come!

ETERNAL GLORY TO THE MEMORY OF ONE OF THE GREAT HEROES OF THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS, THE GREAT HERO OF THE BATTLE OF GUADALCANAL, GUNNERY SERGEANT JOHN BASILONE!

ETERNAL GLORY AND MEMORY TO THE HEROES, MARTYRS AND VETERANS OF THE GREAT BATTLE OF IWO JIMA!

ETERNAL GLORY TO THE MEMORY OF ALL THE ALLIED HEROES AND FALLEN OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR IN THE PACIFIC THEATER OF OPERATIONS!

LONG LIVE THE 74TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BEGINNING OF THE HISTORIC BATTLE OF IWO JIMA!

LONG LIVE THE GLORIOUS, INVINCIBLE AND LEGENDARY UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS, ALWAYS FAITHFUL TILL THE END FOR THE PEOPLE AND THE ENTIRE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND OF THE FREE WORLD!

GLORY TO THE VICTORIOUS PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND HER UNIFORMED MILITARY AND CIVIL SERVICES!

AND FINALLY, GLORY TO THE ARMED FORCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, DEFENDERS OF OUR FREEDOM AND LIBERTY AND GUARANTEE OF A FUTURE WORTHY OF OUR GENERATIONS TO COME!

May our Almighty God bless our great country, the land of the free and the home of the brave, the first of the free republics of our modern world, our beloved, great and mighty United States of America! Semper Fidelis! Oorah!

2140h, February 19, 2019, the 243rd year of the United States of America, the 244th year of the United States Army, Navy and Marine Corps, the 125th of the International Olympic Committee, the 123rd of the Olympic Games, the 78th since the beginning of the Second World War in the Eastern Front and in the Pacific Theater, the 74th since the battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa and the victories in Europe and the Pacific and the 72nd of the United States Armed Forces

Semper Fortis John Emmanuel Ramos

Makati City, Philippines

Grandson of Philippine Navy veteran PO2 Paterno Cueno, PN (Ret.)

(Honor by Hans Zimmer) (Platoon Swims) (Rendering Honors)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

A P-38 Pilot Describes the Attack on Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto

P-38 pilot Roger Ames participated in the shooting down of Japan’s most important admiral.

This article appears in: Fall 2012

By Robert F. Dorr

When American air ace Major John Mitchell led 16 Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters on the longest combat mission yet flown (420 miles) on April 18, 1943, Mitchell’s target was Isoroku Yamamoto, the Japanese admiral considered the architect of the Pearl Harbor attack.

Mitchell’s P-38 pilots, using secrets from broken Japanese codes, were going after Yamamoto, the poker-playing, Harvard-educated naval genius of Japan’s war effort. Mitchell’s P-38s intercepted and shot down the Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bomber carrying Yamamoto. After the admiral’s death, Japan never again won a major battle in the Pacific War.

No band of brothers ever worked together better than the men who planned, supported, and flew the Yamamoto mission. Yet, after the war, veterans fell to bickering over which P-38 pilot actually pulled the trigger on Yamamoto.

There was one thing they never disagreed on. Like most young pilots of their era, they believed the P-38 Lightning was the greatest fighter of its time.

Roger J. Ames (1919-2000) flew the Yamamoto mission. This first-person account by Ames was recorded by the author in 1998 and appeared in his 2007 book, Air Combat: A History of Fighter Pilots; it has never before appeared in a magazine.

Intercepting a Crucial Japanese Radio Message

The downing of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto is arguably the most studied fighter engagement of the Pacific War. Yamamoto, 56, was commander in chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet and the architect of the Pearl Harbor attack. He called himself the sword of Japan’s Emperor Hirohito. He claimed he was going to ride down Pennsylvania Avenue on a white horse and dictate the surrender of the United States in the White House.

Yamamoto studied at Harvard (1919-1921), traveled around America, was twice naval attaché in Washington, D.C., and understood as much about the United States, including U.S. industrial power, as any Japanese leader. In April 1943, Yamamoto was trying to prevent the Allies from taking the offensive in the South Pacific and was visiting Japanese troops in the Bougainville area.

On the afternoon of April 17, 1943, Major John Mitchell, commander of the 339th Fighter Squadron, was ordered to report to our operations dugout at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. The 1st Marine Division had captured the nearly completed field the previous summer and named it for Major Lofton Henderson, the first Marine pilot killed in action in World War II when his squadron engaged the Japanese fleet that was attacking Midway.

Now Mitchell found himself surrounded by high-ranking officers. They told him the United States had broken the Japanese code and had intercepted a radio message advising Japanese units in the area that Yamamoto was going on an inspection trip of the Bougainville area.

The message gave Yamamoto’s exact itinerary and pointed out that the admiral was most punctual. They told Mitchell that Frank Knox, secretary of the Navy, had held a midnight meeting with President Franklin D. Roosevelt regarding the intercepted message. It was decided that we would try to get Yamamoto if we could. The report of the meeting was probably inaccurate because Roosevelt was on a rail trip away from Washington, but the plan to get Yamamoto unquestionably began at the top.

Eighteen P-38s Selected For the Mission

The Navy would never have admitted it, but the Army’s P-38 was the only fighter with the range to make the approximately 1,100-mile round trip. We were under the command of the Navy at Guadalcanal, so you can bet they’d have taken the job if they were able.

First Lieutenant Rex T. Barber, one of two Americans originally credited with shooting down Yamamoto. He later was given sole credit for the kill.

According to the intercepted message, Yamamoto and his senior officers were arriving at the tiny island of Ballale just off the coast of Bougainville at 9:45 the next morning. The message said that Yamamoto and his staff would be flying in Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bombers, escorted by six Zeros. The Yamamoto trip was to include a visit to Shortland Island and Bougainville.

Mitchell was to be mission commander of 18 P-38s that would intercept, attack, and destroy the bombers. That’s all the P-38s we had in commission.

The Plan of Attack

Led by Mitchell, we planned the flight in excruciating detail. Nothing was left to chance. Yamamoto was to be at the Ballale airstrip just off Bougainville at 9:45 the next morning and we planned to intercept him 10 minutes earlier about 30 miles out. To ensure complete surprise, we planned a low level, circuitous route staying below the horizon from the islands we had to bypass, because the Japanese had radar and coastwatchers just as we did.

We plotted the course and timed it so that the interception would take place upon the approach of the P-38s to the southwestern coast of Bougainville at the designated time of 9:35 am. Each minute detail was discussed, and nothing was taken for granted. Takeoff procedure, flight course and altitude, radio silence, when to drop belly tanks, the tremendous importance of precise timing and the position of the covering element: all were discussed and explained until Mitchell was sure that each of his pilots knew his part and the parts of the other pilots from takeoff to return.

Mitchell chose pilots from the 12th, 70th, and 339th Fighter Squadrons. These were the only P-38 squadrons on Guadalcanal. The only belly tanks we had on Guadalcanal were 165-gallon tanks, so we had to send to Port Moresby for a supply of the larger 310-gallon tanks. We put one tank of each size on each plane. This gave us enough fuel to fly to the target area, stay in the area where we expected the admiral for about 15 minutes, fight, and come home. The larger fuel tanks were flown in that night, and ground crews worked all night getting them installed along with a Navy compass in Mitchell’s plane.

Captain Tom Lanphier’s P-38 #122 Phoebe on Guadalcanal with the 339th Fighter Squadron. Lanphier was originally given credit for half a kill before investigations revealed that Barber was the sole marksman.

Four of our pilots were designated to act as the “killer section” with the remainder as their protection. Mitchell said that if he had known there were going to be two bombers in the flight he would have assigned more men to the killer section. The word for bomber and bombers is the same in Japanese. (Author’s note: Ames is incorrect on this point about the Japanese language).

Captain Thomas G. Lanphier, Jr., led the killer section. His wingman was 1st Lt. Rex T. Barber. 1st Lt. Besby F. “Frank” Holmes led the second element. His wingman was 1st Lt. Raymond K. Hine.

The cover section was led by Mitchell and included myself and 11 other pilots. Eight of the 16 pilots on the mission were from the 12th Fighter Squadron, which was my squadron.

Although 18 P-38s were scheduled to go on the mission, only 16 were able to participate because one plane blew a tire on the runway on takeoff and another’s belly tanks failed to feed properly.

“Bogeys! Eleven O’Clock, High!”

It was Palm Sunday, April 18, 1943. But since there were no religious holidays on Guadalcanal, we took off at 7:15 am, joined in formation, and left the island at 7:30 am, just two hours and five minutes before the planned interception. It was an uneventful flight but a hot one, at from 10 to 50 feet above the water all the way. Some of the pilots counted sharks. One counted pieces of driftwood. I don’t remember doing anything but sweating. Mitchell said he may have dozed off on a couple of occasions but received a light tap from “The Man Upstairs” to keep him awake.

Mitchell kept us on course flying the five legs by compass, time, and airspeed only. As we turned into the coast of Bougainville and started to gain altitude, after more than two hours of complete radio silence, 1st Lt. Douglas S. Canning––Old Eagle Eyes–– uttered a subdued “Bogeys! Eleven o’clock, high!” It was 9:35 am. The admiral was precisely on schedule, and so were we. It was almost as if the affair had been prearranged with the mutual consent of friend and foe. Two Betty bombers were at 4,000 feet with six Zeros at about 1,500 feet higher, above and just behind the bombers in a “V” formation of three planes on each side of the bombers.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto in dress whites, photographed on the morning he was killed, addresses a group of pilots at Rabaul, April 18, 1943. His death came as a tremendous blow to the Japanese.

We dropped our belly tanks. We put our throttles to the firewall and went for altitude. The killer section closed in for the attack while the cover section stationed themselves at about 18,000 feet to take care of the expected fighters from Kahili. As Mitchell said, “The night before we knew the Japanese had 75 Zeros on Bougainville and I wanted to be where the action was.

I thought, “Well, I’m going on up higher and we’re going to be up there and have a turkey shoot.’” We expected from 50 to 75 Zeros should be there to protect Yamamoto just as we had protected Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox when he came to visit a couple of weeks before. We’d had as many fighters in the air to protect Knox as we could get off the ground. I guess the Japanese had all their fighters lined up on the runway for inspection. Anyway, none of the Zeros came up to meet us. Our intercept force encountered only the Zeros that were escorting Yamamoto.

Lanphier and Barber: The First to Make Contact With the Enemy

Lanphier and Barber headed for the enemy. When they were about a mile in front and two miles to the right of the bombers, the Zeros spotted them. Lanphier and Barber headed down to intercept the Zeros. The Bettys nosed down in a diving turn to get away from the P-38s. Holmes, the leader of the second element, could not release his belly tanks so, in an effort to jar them loose, he turned off down the coast, kicking his plane around to knock the tanks loose. Ray Hine, his wingman, had no choice but to follow him to protect him. So Lanphier and Barber were the only two going after the Japs for the first few minutes.

Ground crewmen look over Lieutenant Robert Petit’s P-38, Miss Virginia, which Barber borrowed for the mission; he returned it to Henderson Field with over 100 bullet holes.

From this point onward, accounts of the fight get mixed up about who shot down whom. Briefly, here is probably what happened based on the accounts of all involved. I did not see what was happening 18,000 feet below me.

As Lanphier and Barber were intercepted by the Zeros, Lanphier turned head-on into them and shot down one Zero and scattered the others. This gave Barber the opportunity to go for the bombers. As Barber turned to get into position to attack the bombers, he lost sight of them under his wing, and when he straightened around he saw only one bomber, going hell bent for leather downhill toward the jungle treetops.

Barber went after the Betty and started firing over the fuselage at the right engine. And as he slid over to get directly behind the Betty, his fire passed through the bomber’s vertical fin and some pieces of the rudder separated from the plane. He continued firing and was probably no more than 100 feet behind the Betty when it suddenly snapped left and slowed down rapidly, and as Barber roared by he saw black smoke pouring from the right engine.

Shooting Down the Betty

Barber believed the Betty crashed into the jungle, although he did not see it crash. And then three Zeros got on his tail and were making firing passes at him as he headed toward the coast at treetop level taking violent evasive action. Luckily, two P-38s from Mitchell’s flight saw his difficulty and cleared the Zeros off his tail. Holmes said it was he and Hine that chased the Zeros off Barber’s tail. Barber said he then looked inland and to his rear and saw a large column of black smoke rising from the jungle, which he believed to be the Betty he’d shot.

As Barber headed toward the coast he saw Holmes and Hine over the water with a Betty bomber flying below them just offshore. He then saw Holmes and Hine shoot at the bomber with Holmes’ bullets hitting the water behind the Betty and then walking up and through the right engine of the Betty. Hines started to fire, but all of his rounds hit well ahead of the Betty. Then Holmes and Hine passed over the Betty and headed south.

Barber said that he then dropped in behind the Betty flying over the water and opened fire. As he flew over the bomber it exploded, and a large chunk of the plane hit his right wing, cutting out his turbo supercharger intercooler. Another large piece hit the underside of his gondola, making a very large dent in it.

Wreckage of Yamamoto’s “Betty” lies on the jungle floor on the island of Bougainville.

After this, he, Holmes, and Hine fired at more Zeros. Barber said that both he and Holmes shot down a Zero, but Hine was seen heading out to sea smoking from his right engine. As Barber headed home, he saw three oil slicks in the water and hoped that Hine was heading for Guadalcanal, but that was not the case.

Lanphier, having scattered the Zeros, found himself at about 6,000 feet. Looking down, he saw a Betty flying across the treetops, so he came down and began firing a long, steady burst across the bomber’s course of flight, from approximately right angles. In another account, Lanphier said he was clearing his guns. By both accounts, he said he felt he was too far away, yet, to his surprise, the bomber’s right engine and right wing began to burn and then the right wing came off and the Betty plunged into the jungle and exploded.

Return to Guadalcanal

Lanphier said that three Zeros came after him, and he called Mitchell to send someone down to help him. Then, hugging the earth and the treetops while the Zeros made passes at him, he unwittingly led them over a corner of the Japanese fighter strip at Kahili.

He then headed east and, with the Zeros on his tail, he got into a high-speed climb and lost them at 20,000 feet; he got home with only two bullet holes in his rudder. Contrast this to the 104 bullet holes in Barber’s plane, plus the knocked-out intercooler and the huge dent in his gondola.

Flying back to Guadalcanal, I heard Lanphier get on the radio and say, “That SOB won’t dictate peace terms in the White House.” This really upset me because we were to keep complete silence about the fact that we had gone after Yamamoto. The details of this mission were not to leave the island of Guadalcanal.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friday the 13th

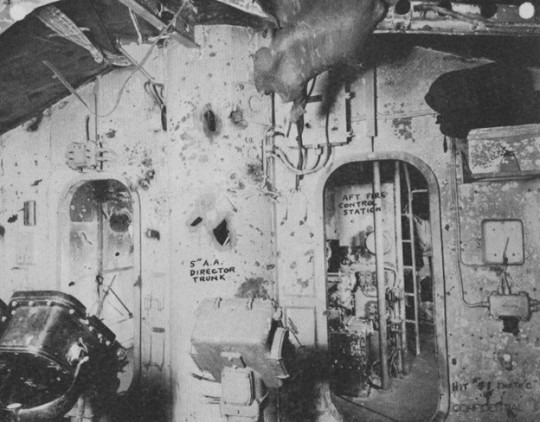

Head out to Lands’ End in San Francisco and you will encounter what appears to be an observation platform overlooking the mouth of the Golden Gate. It is a memorial built with the battle-scarred bridge wings removed from the Heavy Cruiser USS San Francisco (CA-38) following an epic night battle.

In early 1942 an Allied intelligence aircraft identified that the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) had begun constructing a large airfield on an island nobody had ever heard of. Should this airfield become operational, Japanese long-range bombers would threaten the critical sea lanes from the United States to Australia and New Zealand. U.S. Admiral Ernest King, Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, directed the invasion of Guadalcanal to deny the use of the airstrip by the Japanese. With that decision, the stage was set for a bloody battle on land sea and air. The battle began on 7 August 1942, when Allied (primarily U.S.) forces landed against light resistance on Guadalcanal, and the adjacent Tulagi, and Florida Islands in the Solomon Islands. Things rapidly escalated as the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters responded by assigning the Imperial Japanese Army's 17th Army, with the task of retaking Guadalcanal at all costs. In addition, consistent with IJN naval war plans the emerging Guadalcanal conflict was anticipated to provide the opportunity for a decisive naval engagement. Accordingly, orders were issued to converge on the island. The Japanese General admonished his troops that this was going to be the decisive battle between Japan and the United States. A battle that would determine the rise or fall of the Japanese empire. He was right, and it would take six-months and tens of thousands of lives before the Guadalcanal campaign was decided.

Guadalcanal’s land and naval battles became one of the bloodiest campaigns of the war and it remains legendary in US naval and Marine history. The campaign ended in a US victory and, even though the Marines originally felt deserted by the Navy, the battle at sea was actually bloodier than that on land. Two Mare Island built heavy cruisers the USS Chicago (CA-29) and the San Francisco figured prominently in the ongoing struggle. After the Navy first left the Marines ashore to fend for themselves, it was decided to send available assets on what amounted to a suicide mission pitting US cruisers against the overwhelming superiority of IJN Battleships. The San Francisco, source of those bridge wings on Lands’ End, played a significant role in that fight which would ultimately result in naval casualties that were three times higher than the losses of the Marines and Army combined. The sea battles mostly took place at night when the IJN would sail down the slot between Florida Island and Guadalcanal to attack US naval assets and bombard US land forces on Guadalcanal.

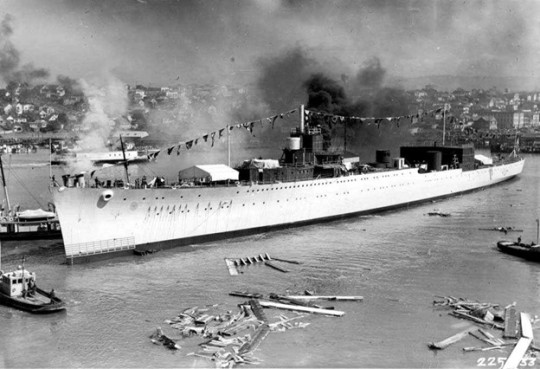

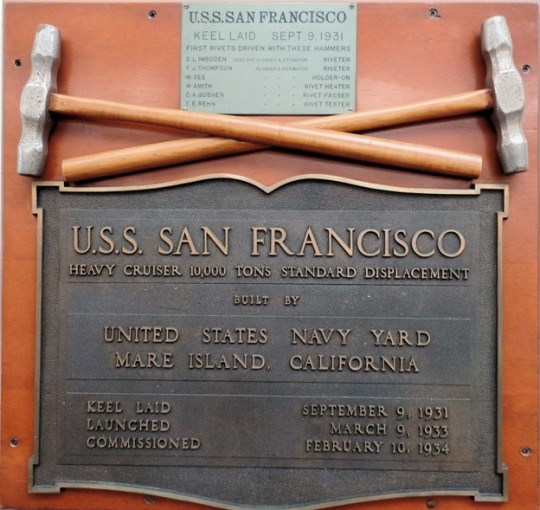

On March 9, 1933, San Francisco’s namesake, and the second heavy cruiser to be built at Mare Island Naval Shipyard, slid down the building ways. Champagne was not available due to the Prohibition, so she was christened with water from the famed Hetch-Hetchy water system. The christening fluid was even rarer than champagne at the time because after 19 years and many bond issues none of it had yet reached San Francisco (nor would any until another year and half had passed). Approximately 25,000 people gathered on both sides of the channel to see the launch during those early days of the Depression. Few could have envisioned that ten years later the heavily damaged cruiser would limp back to Mare Island for repairs following a night-time engagement in the campaign to capture Guadalcanal.

On the night of Friday, November 13, 1942, the San Francisco attacked a vastly superior Japanese force As part of Task Group 67.4 off the coast of Guadalcanal. It was the most brutal close-quarters naval engagement of World War II. The San Francisco took 45 direct hits and sustained heavy damage while sinking one Japanese ship and seriously damaging two others (including a battleship). With half her crew killed or wounded the remaining crew members performed valiantly as they tended to the casualties and performed damage control. Through their efforts the badly damaged San Francisco survived to fight another day. One hundred and six sailors, including Rear Admiral Daniel Callaghan, were killed and 131 more wounded in what Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King called "…the most furious sea battle fought in history." The battle of Friday the 13th was an American strategic victory despite the loss of two cruisers and four destroyers. On that night the valiant actions of those ships prevented the IJN from shelling the Cactus Air Force on Guadalcanal. The next morning that air force decimated the IJN troopships attempting to reinforce and resupply Japanese forces on Guadalcanal. It was the beginning of the end for Japanese efforts to win back Guadalcanal and the San Francisco was a key part of that victory.

The San Francisco was sent back to Mare Island for repairs. Arriving in her namesake city she and her crew were celebrated in week long festivities before returning to Mare Island for repair of her extensive battle damage. By the end of the seven naval battles in the Guadalcanal campaign over 5,000 Americans were killed at sea, and the battleground would be become so littered with sunken combatants that it became known as “Iron Bottom Sound.” To this day you can visit the memorial featuring the battle-scarred bridge wings of the San Francisco at Lands’ End in the city of San Francisco. When you do, reflect on those men who stood watch and died on that bridge knowing they were on a suicide mission during a furious night battle against vastly superior forces.

Dennis Kelly

#mare island#naval history#san francisco bay#us navy#vallejo#san francisco#world war 2#world war ii#world war two#california#Guadalcanal#Savo Island#IJN#Japan#Pacific#Night Battle#Sea Battle

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Light cruiser USS Boise (CL-47) returns to the Philadelphia Naval Yard to repair damage sustained in the Battle of Cape Esperance, November 1942. Minutes before midnight off Guadalcanal on October 11th, an American task force under Rear Admiral Norman Scott intercepted and engaged a Japanese cruiser force under the command of Rear Admiral Aritomo Gotō. Boise helped sink the heavy cruiser Furutaka and destroyer Fubuki, also assisting in battering Gotō's flagship Aoba. Less than 20 minutes after the battle had been joined, Boise was struck by eight 203mm shells from the cruiser Kinugasa. Boise's forward magazines were flooded and several of her guns were put out of action, forcing the cruiser to break formation and leave the battle. The damage proved not to be fatal, however, and she was able to return home for repairs under her own power.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 11.13 (before 1960)

1002 – English king Æthelred II orders the killing of all Danes in England, known today as the St. Brice's Day massacre. 1093 – Battle of Alnwick: in an English victory over the Scots, Malcolm III of Scotland, and his son Edward, are killed. 1160 – Louis VII of France marries Adela of Champagne. 1642 – First English Civil War: Battle of Turnham Green: The Royalist forces withdraw in the face of the Parliamentarian army and fail to take London. 1715 – Jacobite rising in Scotland: Battle of Sheriffmuir: The forces of the Kingdom of Great Britain halt the Jacobite advance, although the action is inconclusive. 1775 – American Revolutionary War: Patriot revolutionary forces under Gen. Richard Montgomery occupy Montreal. 1833 – Great Meteor Storm of 1833 1841 – James Braid first sees a demonstration of animal magnetism by Charles Lafontaine, which leads to his study of the subject he eventually calls hypnotism. 1851 – The Denny Party lands at Alki Point, before moving to the other side of Elliott Bay to what would become Seattle. 1864 – American Civil War: The three-day Battle of Bull's Gap ends in a Union rout as Confederates under Major General John C. Breckinridge pursue them to Strawberry Plains, Tennessee. 1887 – Bloody Sunday clashes in central London. 1901 – The 1901 Caister lifeboat disaster. 1914 – Zaian War: Berber tribesmen inflict the heaviest defeat of French forces in Morocco at the Battle of El Herri. 1916 – World War I: Prime Minister of Australia Billy Hughes is expelled from the Labor Party over his support for conscription. 1917 – World War I: beginning of the First Battle of Monte Grappa (in Italy known as the "First Battle of the Piave"). The Austro-Hungarian Armed Forces, despite help from the German Alpenkorps and numerical superiority, will fail their offensive against the Italian Army now led by its new chief of staff Armando Diaz. 1918 – World War I: Allied troops occupy Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire. 1922 – The United States Supreme Court upholds mandatory vaccinations for public school students in Zucht v. King. 1927 – The Holland Tunnel opens to traffic as the first Hudson River vehicle tunnel linking New Jersey to New York City. 1940 – Walt Disney's animated musical film Fantasia is first released at New York's Broadway Theatre, on the first night of a roadshow. 1941 – World War II: The aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal is torpedoed by U-81, sinking the following day. 1942 – World War II: Naval Battle of Guadalcanal: U.S. and Japanese ships engage in an intense, close-quarters surface naval engagement during the Guadalcanal Campaign. 1947 – The Soviet Union completes development of the AK-47, one of the first proper assault rifles. 1950 – General Carlos Delgado Chalbaud, President of Venezuela, is assassinated in Caracas. 1954 – Great Britain defeats France to capture the first ever Rugby League World Cup in Paris in front of around 30,000 spectators. 1956 – The Supreme Court of the United States declares Alabama laws requiring segregated buses illegal, thus ending the Montgomery bus boycott.

0 notes