#nakajima aviation

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Nakajima Ki84 Hayate

@ron_eisele via X

#ki 84 hayatae#nakajima aviation#fighter#imperial japanese army air service#ww2 history#ww2 aircraft#ww2#pacific theater#ww2 aviation#wwii aircraft#wwii planes

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

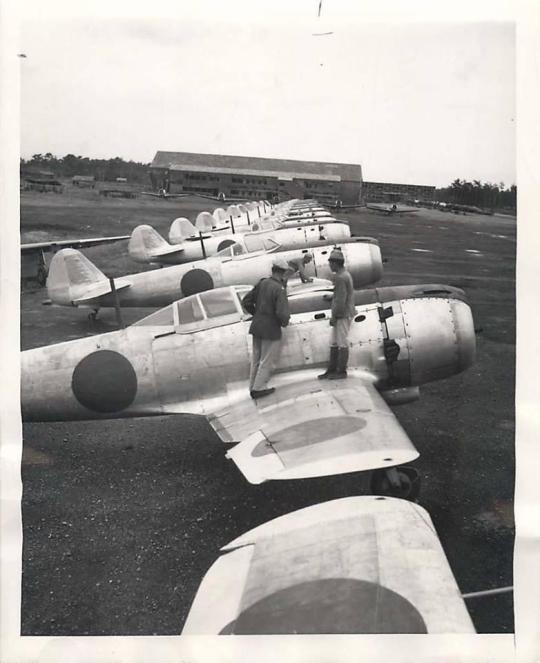

Chasseurs Nakajima Ki-84 Hayate démilitarisés et stockés après la capitulation du Japon – Base aérienne de Utsunomiya – Japon – 1945

#WWII#après-guerre#after war#capitulation du japon#surrender of japan#démilitarisation#demilitarization#armée de l'air impériale japonaise#imperial japanese army air service#ijaas#aviation militaire#military aviation#chasseur#avion de chasse#fighter#nakajima ki-84 hayate#ki-84 hayate#ki-84#utsunomiya#japon#japan#1945

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Nakajima B5N2 “Kate” (replica, obvs)

#photo of the day#photography#The Nakajima B5N2#Kate#Japanese torpedo-bomber#replica#aviation#airplanes#aircraft#Mid Atlantic Air Museum#World War II Weekend#nikon photography#nikon coolpix p1000#spring 2024

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

HIGH NOON OVER ALICANTE

High noon, 14 November 1944. Eleven P-38s of the 80th Fighter Squadron "Headhunters" weaved back and forth above two groups of B-24s droning north at 16,000 feet toward Japanese-held Alicante Airdrome, located on Negros Island in the Philippines.

#plane #art #military

Artist: Roy Grinnell

#P38Lightning #p38 #Zero #CombatAircraft #fighteraircraft #theaviationart #theaviationartofficial #Paintings #Artwork #Airplane #Planes #warbird #carrierplanes #militaryhistory #fighteraircraft #aviationpic #airforce #flight #plane

@TheAviationArt via X

That looks like a KI-84?

#p 38 lightning#lockheed aviation#usaaf#fighters#ki-84#nakajima aircraft#aviation#ww2#aircraft#ww2 aircraft#ww2 art#ww2 aviation#ww2history#wwii aircraft#wwii planes

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

1942 05 Burma Chennault's Flying Tigers - Robert Taylor

Strangled by the Japanese blockade of its sea ports, and with its supplies from Russia diverted to combat Hitler’s invasion in the South, China was left with but one lifeline for vital supplies from the outside world: A treacherous unpaved track hacked through mountain terrain linking the vital port of Rangoon with the city of Kunming, in South West China – it was the infamous Burma Road.With the Imperial Japanese air force hell-bent on destroying China’s last supply link, opposition had almost evaporated but for a tiny “air force” of American volunteers led by the indomitable figure of Claire Chennault.Formed in early 1941, many months before Pearl Harbor, a rag-tag bunch of 100 recruited flyers supported by 200 ground personnel, known officially as the American Volunteer Group came together to stand alone against the might of the Japanese air force in Indo-China. During their brief existence this remarkable group became one of the most successful and famous fighter units of all time. Blazing a trail in the skies over Burma and China they created a legend that will remain in the folklore of aviation history. They were Chennault’s FLYING TIGERS. With little official support from home and almost without replacement aircraft or spares, the P-40 Tomahawk pilots of the AVG became the scourge of the Japanese air force and the heroes of the Chinese people. In a six month period of combat, with no more than 50 or 60 serviceable aircraft at anyone time, and almost always heavily outnumbered in the air, they destroyed some 300 Japanese aircraft, while probably damaging or destroying another 300, and caused incalculable damage to Japanese ground resources. Their brief, glorious existence came to an end when, on July 4, 1942, the AVG was absorbed into the U. S. Army Air Corps and Chennault’s Flying Tigers passed into history.Moved by the exhilarating legend of the Flying Tigers, Robert Taylor has created one of his finest masterpieces. Capturing perfectly the spirit of the Flying Tigers “CHENNAULT’S FLYING TIGERS” portrays a scene typical of the distant war fought by this tiny band of warriors. Depicted in the foreground of Robert’s dramatic and spectacular combat scene are two P-40 Tomahawks of the 2nd pursuit squadron, the “Panda Bears,” as they pull out of their diving attack just above the tree-tops of the Burmese jungle. One bomber hits the water, as two more P-40s bear down on another Nakajima bomber. In the distance the air is busy with low-level combat.

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nakajima Ki-84 Hayate fighter aircraft

First flown February 1943 , the Ki-84 was operated by the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service in the last two years of World War II. The Allied reporting name was "Frank"; the Japanese Army designation was Army Type 4 Fighter. It had a top speed of over 400 mph, it was the fastest fighter of it’s type used by the Japanese.

105 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Slip transport of Nakajima A6M2-N from 934 kokutai at Halong air base, Ambon island, Dutch East Indies, 1 March 1944

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

I occasionally dabble in aviation art for books, magazines and model kits. These are (top to bottom) a Nakajima Ki-44, a Mitsubishi F1-M2 and an Aviatik (Berg) D.I

More of my avation art here.

#aviation#aviation art#aircraft#airplanes#aeroplanes#history#WWII#WWi#illustration#digital art#my artwork

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

• Oscar F. Perdomo (USAAF U.S Ace)

Oscar Francis Perdomo was a Hispanic United States Air Force officer and fighter pilot who was the last "ace in a day" for the United States in World War II.

Perdomo was born June 14th, 1919 in El Paso, Texas, one of five siblings born to Mexican immigrants to the United States. His father served in the Mexican Revolution under the command of Francisco "Pancho" Villa before emigrating to the United States. After completing school Perdomo enlisted in the army reserves in 1942. In February 1943, Perdomo entered an Army Air Forces (AAF) Pilot School in Chandler, Arizona. The AAF schools were civilian flying schools, under government contract, which provided a considerable part of the flying training effort undertaken during World War II by the Army Air Forces. Perdomo received his "wings" on January 7th, 1944. He was then sent to the Army Air Forces Basic Flight School at Chico, California, where he underwent further training as a Republic P-47 Thunderbolt pilot.

Upon the completion of his training he was assigned to the 464th Fighter Squadron which was part of the 507th Fighter Group that was sent overseas to the Pacific theater to the Island of Ie Shima off the west coast of Okinawa. The primary mission of the 507th was to provide fighter cover to 8th Air Force Boeing B-29's which were to be stationed on Okinawa. The 507th began operations on July 1st, 1945. Perdomo was assigned P-47N-2-RE number 146 aircraft. maintained by crew chief S/Sgt. F. W. Pozieky. Perdomo nicknamed his airplane Lil Meaties Meat Chopper with the nose art depicting a diapered baby chomping a cigar in his mouth and derby hat on his head, clutching a rifle. The name referred to his first son, Kenneth, then a year and a half old. Perdomo flew his first combat mission on July 2nd, while escorting a B-29 to Kyushu.

A "flying ace" or fighter ace is a military aviator credited with shooting down five or more enemy aircraft during aerial combat. The term "ace in a day" is used to designate a fighter pilot who has shot down five or more airplanes in a single day. The last "Ace in a Day" for the United States in World War II was 1st Lt. Oscar Francis Perdomo. Perdomo was a first lieutenant and a veteran of ten combat missions when on August 9th, 1945 the United States dropped the world's second atomic bomb on Nagasaki, Japan. The allies were still awaiting Japan's response to the demand to surrender and the war continued, when on August 13th, 1945 1st Lt. Perdomo, shot down four Nakajima "Oscar" fighters and one Yokosuka "Willow" Type 93 biplane trainer. While the 507th Fighter Group mission reports confirm his kills as "Oscars", they were actually Ki-84 "Franks" from the 22nd and 85th Hiko-Sentais. The combat took place near Keijo / Seoul, Korea when 38 Thunderbolts of the 507th Fighter Wing, USAAF, encountered approximately 50 enemy aircraft. It was Perdomo's last combat mission, and the five confirmed victories made him an "Ace in a Day" and thus the distinction of being the last "Ace" of the United States in World War II. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and the Air Medal with one leaf cluster.

After the war, Perdomo continued to serve in the Army Air Forces. In 1947, he was reassigned to the newly formed United States Air Force and served until January 1950. When Perdomo returned to civilian life, he joined the Air Force Reserve. On June 30th, 1950, Perdomo was recalled to active duty upon the outbreak of the Korean War at the rank of captain. He continued to serve in the Air Force until January 30th, 1958 when he left the military at the rank of major. Perdomo was emotionally affected when his son, SPC4 Kris Mitchell Perdomo, was one of 3 men killed on May 5th, 1970, aboard a U.S. Army helicopter UH-1 Iroquois which crashed and exploded about 5 miles southwest of the city of Phy Vinh in Vĩnh Bình Province, South Vietnam. He had trouble coping with the situation and developed an addiction to alcohol, which took Major Oscar F. Perdomo's life on March 2nd, 1976. He was proclaimed dead upon his arrival at USC Medical Center, Los Angeles. His name is inscribed in the United States Air Force Memorial.

#second world war#world war 2#world war ii#wwii#military history#history#biography#us army air force#us history#airforce history#unsung hero#u.s aces#hispanic representation#hispanic history#hispanic heritage month

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

More masterful aviation art by Ian Kennedy. 'Fighting Floatplanes' from Warlord No. 76, 1976 featuring:

Arado Ar196;

Nakajima A6M2-N (based on the Mitsubishi A6M Zero);

Vought OS2U Kingfisher;

CANT Z.506N.

DC Thomson.

#1976#dc thomson#warlord#fighting floatplanes#arado#arado ar196#nakajima a6m2-n#mitsubishi a6m#vought kingfisher#cant z506n

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

@Sylvia70485099🇫🇷🇺🇦via X

#ki 43 haybusa#nakajima aviation#fighter#imperial japanese army air service#ww2 history#ww2 aircraft#ww2#pacific theater#ww2 aviation#wwii aircraft#wwii planes

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bombardier-torpilleur Nakajima B5N1 d'une unité d'entraînement de la marine impériale japonaise – 1930's - 1940's

#WWII#marine impériale japonaise#imperial japanese navy#ijn#aviation militaire#military aircraft#bombardier-torpilleur#torpedo bomber#bombardier-torpilleur embarqué#carrier-based torpedo bomber#nakajima b5n#b5n#1930's#1940's

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

While 1941 was a dark year for the Allies especially in the Pacific, the exploits of the Flying Tigers against a numerically superior Japanese force boosted American morale early in the war. The leader of the Flying Tigers, General Claire Chennault, rigorously trained his men to capitalize on the strengths of the P-40 Warhawk against the more maneuverable Japanese fighters. They avoided a turning fight and used the Warhawk’s speed and sturdiness in slashing attacks at high speed. Contrary to popular belief, the Flying Tigers never battled against the legendary Mitsubishi A6M Zero- it was likely a case of mistaken identity as the Zero was a naval fighter and the Imperial Japanese Navy had withdrawn its Zero units from China before the Flying Tigers went into action. Their main opposition would have been the Nakajima Ki-43 Oscar and the elderly Ki-27 Kate fighters of the Imperial Japanese Army. In those days, just about any Japanese fighter was referred to as a "Zero". Though not as a capable as the Zero, the Oscar was a more nimble and maneuverable fighter than the P-40 Warhawk. Flown in the right way, the Warhawk could effectively battle the Japanese. The Flying Tigers astutely realized the P-40 had a climb and speed advantage and used their P-40s in slashing attacks, avoiding the turning fight with the more nimble Japanese fighters. The bigger ailerons of the Oscar that gave it outstanding roll maneuverability were also a liability as Warhawk pilots would keep their speed up during dogfights- the higher speeds put higher dynamic loads on the Oscar’s ailerons, making the aircraft sluggish and less maneuverable. #avgeek #aviation #aircraft #planeporn #KRBD #RBD #Dallas #airport #texas #igtexas #WingsOverDallas2021 #CommemorativeAirForce #Curtiss #P40 #Warhawk #FlyingTigers #USAAF #WW2 #mil_aviation_originals #instaaviation #aviationlovers #aviationphotography #flight #AvGeekNation #AvgeekSchoolofKnowledge (at Dallas Executive Airport) https://www.instagram.com/p/CVwSKSSslnc/?utm_medium=tumblr

#avgeek#aviation#aircraft#planeporn#krbd#rbd#dallas#airport#texas#igtexas#wingsoverdallas2021#commemorativeairforce#curtiss#p40#warhawk#flyingtigers#usaaf#ww2#mil_aviation_originals#instaaviation#aviationlovers#aviationphotography#flight#avgeeknation#avgeekschoolofknowledge

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marine Air’s Dark Day at Midway

Marine Aircraft Group 22’s experience at the Battle of Midway serves as a hard lesson in trying to do too much with too little.

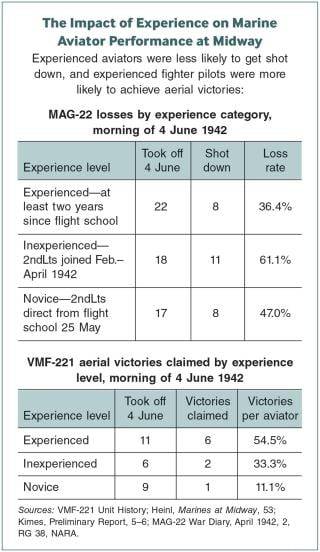

The 4th of June 1942 was a very bad day for Marine Corps aviation. At the Battle of Midway, Marine Aircraft Group (MAG) 22 suffered terrible losses and contributed little to the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s spectacular victory that day. The group’s fighting squadron, VMF-221, lost far more aircraft than its pilots shot down. Its dive-bomber squadron, VMSB-241, suffered staggering losses without hitting a single Japanese ship.

Midway historians have thoroughly chronicled the actions of these two squadrons and touched on some reasons for their performance. The most cited causes are the obsolescence of Marine aircraft and the inexperience of Marine aviators.1 A closer examination of archival material reveals additional factors that impaired the group’s performance at Midway and new insights into why MAG-22 sent such green pilots into battle.

The heart of MAG-22’s troubles lay in its two competing missions: While forward deployed to defend an advanced base, the group also served as a de facto training command for new aviators. This alone would have undermined its combat readiness. But additional factors worked against MAG-22. In the weeks before the battle, the flight hours the group devoted to training were limited by its responsibilities to defend Midway Atoll and by logistical shortfalls. During the battle, Naval Air Station Midway and MAG-22 were unable to coordinate aircraft from three services based at the atoll. Finally, imprecise direction from Pacific Fleet commander Admiral Chester W. Nimitz led to misunderstandings of how MAG-22 would employ its fighting squadron.

Present-day naval commanders are acutely familiar with the challenge of balancing combat readiness and forward presence. As naval leaders look for ways to maintain Navy and Marine Corps forces in the western Pacific and prepare for possible conflict there, the experience of MAG-22 at Midway provides a sobering reminder of the risks of attempting to do too much with too little.

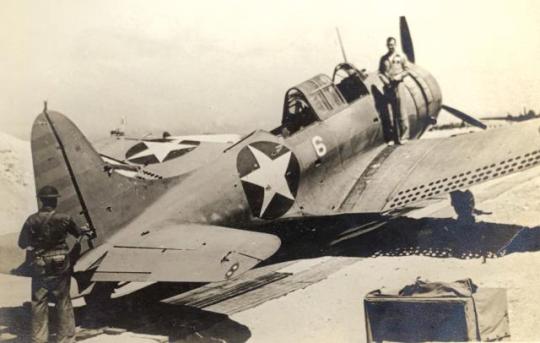

At Midway, First Lieutenant Daniel Iverson stands on a wing of his shot-up SBD-2 Dauntless, one of MAG-22’s 46 aircraft losses in the Battle of Midway. Later repaired in the United States, the restored SBD is now an exhibit at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida.

At Midway, First Lieutenant Daniel Iverson stands on a wing of his shot-up SBD-2 Dauntless, one of MAG-22’s 46 aircraft losses in the Battle of Midway. Later repaired in the United States, the restored SBD is now an exhibit at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida. National Naval Aviation Museum

MAG-22’s Very Bad Day

At 0555 on 4 June 1942, Midway’s radar detected a large formation of aircraft 93 miles northwest of the atoll. MAG-22’s siren wailed. In accordance with orders issued the previous evening by Lieutenant Colonel Ira L. Kimes, the commander of MAG-22, VMF-221 launched its aircraft immediately. A detachment of six Navy TBF Avengers took off next, followed by four Army Air Forces B-26 Marauders armed with torpedoes. The TBFs and B-26s proceeded independently to attack the Japanese carriers. The 16 SBD-2 Dauntlesses and 12 SB2U-3 Vindicators of VMSB-241 took off last and rendezvoused about 20 miles east of Midway’s Eastern Island.2

VMF-221’s commanding officer, Major Floyd B. Parks, had organized his 21 F2A-3 Buffalos and seven F4F-3 Wildcats into four divisions of Buffalos and one of Wildcats. All but one F2A-3 and one F4F-3 were mission ready and got airborne, though the divisions became slightly disorganized during the hasty scramble. The Japanese strike consisted of 108 aircraft—36 Aichi D3A “Val” dive bombers, 36 Nakajima B5N2 “Kate” carrier attack aircraft, and 36 Mitsubishi A6M2 “Zeke,” or Zero, fighters. In accordance with Kimes’ plan, MAG-22’s fighter direction center funneled all five of VMF-221’s divisions to intercept the incoming strike. The Marines had the altitude advantage, and the separate divisions launched a series of overhead gunnery passes against the Japanese bomber formations. As the slower Marine aircraft recovered for additional passes, the nimbler Zeros overtook them and sent one after another tumbling downward.3

There is little doubt VMF-221 got the worst of the fight. The Japanese shot down 15 Marine fighters and severely damaged another nine, leaving just one F2A-3 and one F4F-3 ready to fly. Though Kimes afterward estimated Japanese losses at 43 aircraft, his surviving pilots definitively claimed just nine victories. Kimes’ estimate included “probable victories by missing fighter pilots” as well as claims by rear-seat gunners of VMSB-241.4 The actual total was far lower. VMF-221 probably shot down just three aircraft outright. Another 16 Japanese aircraft survived the raid but either ditched or were so irreparably damaged they could not fly again.5

A PBY Catalina flying boat had spotted the Japanese carriers, and MAG-22 passed their location to VMSB-241.6 Major Lofton R. Henderson, the squadron commander, led the SBDs. Major Benjamin W. Norris, the executive officer, led the SB2Us. While Henderson took his unit to 9,000 feet, Norris climbed to 13,000 feet.7 On paper, the SB2U-3s were nearly as fast as the SBD-2s, but the two flights proceeded independently.8

Because the Marine dive bombers were slower than the TBFs and B-26s, had taken off last, and had flown east before heading northwest, VMSB-241 did not attack until a half hour after the TBF and B-26 attacks had ended. The Japanese combat air patrol had shot down five of the six Avengers and two of the four Marauders; none had scored a hit. When Henderson and his SBDs spotted the carrier Hiryū at about 0755, the Japanese combat air patrol still had 13 fighters aloft.9

Henderson conducted a glide-bombing attack. A dive-bombing attack would have facilitated bombing accuracy and complicated fighter gunnery and antiaircraft solutions. But more than half of Henderson’s pilots were too inexperienced to attempt the technique, and the cloud cover would have made dive bombing particularly difficult.10

The combat air patrol’s Zeros attacked Henderson first. On their second pass, they sent him down in flames. The remaining SBDs continued the gliding attack. One by one, the Marines released their bombs—and missed. Some came petrifyingly close for the Hiryū’s crew, and many Marines mistakenly believed they had scored hits.11

Norris and his Vindicators arrived at about 0820, less than ten minutes after the surviving SBD-2s had departed and amid an attack by Army Air Forces B-17 Flying Fortresses. The combat air patrol had doubled to 26 fighters. Norris descended through the clouds toward the carrier Akagi. The Zeros could not find the dive bombers as long as they were in the safety of the cloud bank, but neither could the Marines see the ships below. When they emerged at 2,000 feet, they saw only the battleship Haruna. Norris also attempted a gliding attack. The Haruna maneuvered evasively, neatly avoiding every one of the Marines’ bombs. The SB2Us hugged the surface and flew back to Midway.12 Only 8 of VMSB-241’s 16 SBD-2s and 8 of its 12 SB2U-3s returned.13

VMSB-241 conducted two more strikes during the battle. That evening Norris led five SB2U-3s and six SBD-2s in a vain search for burning carriers. They found nothing, and Norris did not return, lost in the inky, moonless squalls. On 5 June, VMSB-241 attacked the cruisers Mogami and Mikuma. The squadron lost another Vindicator to antiaircraft fire and again scored no hits.14

What Was Done Well

MAG-22 did some things remarkably well in its first action. Due to superb intelligence and early warning, no airworthy planes were caught on the ground. The fighter direction center placed the fighters in an optimum intercept position. The dive bombers located the Japanese carriers. Most impressively, every fighter and dive-bomber pilot attacked without hesitation into the teeth of a formidable defense.

MAG-22’s efforts indirectly contributed to the destruction of the Akagi and two other carriers, the Kaga and Sōryū, later that morning. As historians Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully demonstrated, the cumulative effect of the series of failed attacks by bombers from Midway and U.S. carriers created conditions that delayed Admiral Chūichi Nagumo’s counterattack and placed his carriers at greater vulnerability to the dive bombers from the USS Enterprise (CV-6) and Yorktown (CV-5). Dodging the attacks required the carriers to maneuver violently. Defending against them required the carriers to launch and recover fighters. Perhaps just as important, Nagumo faced a series of menacing dilemmas, complicating his decision-making. When the dive bombers from the Enterprise and Yorktown appeared overhead at 1020, Kates and Vals were still below on the hangar decks, where their fuel and ordnance amplified the destructive power of the American bombs.15

VMF-221 also helped reduce the strength of Nagumo’s counterpunch when it did come. The only carrier that survived the Enterprise and Yorktown dive-bomber attacks was the Hiryū. It was her air group that VMF-221 had attacked. Though the Marine fighters shot down just two Kates outright, another seven Kates were shot down by Marine antiaircraft guns, ditched, or were too damaged to participate in the strikes against the U.S. carriers.16 In other words, the Marines did not bring down many aircraft, but the ones they did bring down were the right ones—aircraft from the Hiryū’s air group.

Nonetheless, 4 June had been an awful day for MAG-22. It had lost many aircraft, shot down only a handful of the enemy, and hit no ships. Forty-two MAG-22 Marines had died; 36 pilots and gunners were missing; and six Marines had been killed in the bombing of Eastern Island.17

‘Not a Combat Airplane’

On 17 April, Major (soon to be Lieutenant Colonel) Ira L. Kimes (below) landed at Midway Atoll to replace Lieutenant Colonel William Wallace as MAG-22 commander. Accompanying Kimes were six second lieutenants, green aviators who replaced six captains, seasoned fliers, who left the atoll with Wallace three days later. Public Domain

Every surviving Marine fighter pilot from VMF-221 attested to the superiority of the Zero over the Marine fighters. Captain

The F2A-3 is not a combat airplane. It is inferior to the planes we were fighting in every respect.

It is my belief that any commander that orders pilots out for combat in a F2A-3 should consider the pilot as lost before leaving the ground.18

Kimes agreed. In his endorsement to his aviator’s statements, Kimes recommended that the fleet relegate the F2A-3 Buffalo, the F4F-3 Wildcat, and the SB2U-3 Vindicator to training commands.19

The Vindicator was indeed past its usefulness. However, there is evidence that neither fighter was to blame for VMF-221’s poor performance. With improved tactics, Marine and Navy pilots would achieve far better results with the F4F in the Solomons. Captain Marion Carl, the only Marine to shoot down a Zero over Midway, believed the F2A-3 was as maneuverable and fast as the F4F-3, and its only drawbacks were that it could not absorb punishment and was less stable as a gunnery platform than the Wildcat.20

Some British and Dutch Buffalo aces, whose squadrons suffered grievously against Imperial Japanese Navy Zeros, attributed their lopsided outcome to Japanese proficiency and numbers rather than the Buffalo’s inferiority. Finnish Buffalo pilots enjoyed great success flying the planes against the Soviets.21 The Buffalo’s mixed performance in other theaters suggests that other factors contributed to VMF-221’s poor performance.

‘Half-Baked Flyers’

When VMF-221 and VMSB-241 had landed on Eastern Island in December 1941, both squadrons were top heavy with experience. VMF-221’s most junior pilot had been flying for at least a year since flight school.22 But the 57 aviators who flew on 4 June included 35 second lieutenants, none of whom had been with their squadron more than four months, and 17 of whom had arrived on 27 May directly from flight school.23

SB2U-3 Vindicator dive bombers take off from Midway’s Eastern Island in early June, possibly to attack Japanese carriers the morning of 4 June. While inferior aircraft—including Vindicators—were factors in MAG-22’s poor performance at Midway, tactics and training played key roles.

SB2U-3 Vindicator dive bombers take off from Midway’s Eastern Island in early June, possibly to attack Japanese carriers the morning of 4 June. While inferior aircraft—including Vindicators—were factors in MAG-22’s poor performance at Midway, tactics and training played key roles. U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

In the first half of 1942, Marine aviation had two conflicting missions: defending the fleet’s advanced bases and training new aviators. Newly winged aviators reported to the fleet with just 200 hours of flight time, and none in the aircraft they would fly in combat.24 The new aviators needed operational training, but the aircraft they needed to train in were defending advanced bases in the Pacific.

On 8 January 1942, Brigadier General Ross E. Rowell, the commander of 2d Marine Air Wing, described the dilemma in a letter to Vice Admiral William F. Halsey Jr., the commander of Aircraft, Battle Force, Pacific Fleet: “I have now accumulated 35 second lieutenants in various stages of advanced training. . . . If ComAirBatFor approves and you want some half-baked flyers, send me a dispatch to that effect.” Halsey approved; he directed Rowell to order the green fliers to squadrons like VMF-221 and VMSB-241.25 This decision set in motion a sequence of personnel transfers that diluted the combat readiness of forward-deployed squadrons. As inexperienced aviators joined squadrons at advanced bases, experienced aviators left to form new squadrons in Hawaii and California.

Marine aviation was still following its prewar training pipeline. Once students were designated naval aviators, they reported to squadrons in the Fleet Marine Force for about a year of operational flight training in combat aircraft.26

Not only did MAG-22 not have a year to train its new aviators, but the group’s commitment to the defense of Midway also required it to devote most of its operational flights to patrols and radar calibration vice gunnery and tactics. Less than 30 percent of VMF-221’s missions from December 1941 to May 1942 were dedicated to improving the lethality of its fighter pilots.27

Logistics shortfalls further impinged on the group’s training. A shortage of .50-caliber machine-gun ammunition often limited gunnery practice to dummy runs.28 In the final week before combat, PBY Catalinas and B-17 Flying Fortresses drew thirstily from Midway’s fuel stocks, which were already limited due to an incredible blunder. On 22 May, demolition charges placed at an underground fuel storage facility detonated when one of the defense battalion batteries fired its 11-inch guns. The station lost 375,000 gallons of precious aviation fuel and its pipeline to Eastern Island.29 The resulting shortage prevented the group from providing the 17 Marines fresh out of flight school with anything more than familiarization flights. VMSB-241 could not even check out its new pilots in their SBDs.30

Without question, MAG-22 fought the Battle of Midway with inferior aircraft and many “half-baked” pilots. Though the odds were stacked against the group’s aviators, command decisions may have stacked the odds higher than they needed to be.

‘No Organized Plan Whatsoever’

In a 1966 interview, MAG-22’s former executive officer stated there had been “no organized plan whatsoever” to coordinate Midway’s Army Air Forces, Navy, and Marine aircraft.31 Though not strictly true, his characterization betrays how Naval Air Station Midway and MAG-22 struggled to coordinate air operations.

In anticipation of the coming fight, Nimitz had abundantly reinforced Midway. In addition to MAG-22, Midway’s air force included 31 PBYs, 17 B-17s, the 4 B-26s, and the 6 TBFs. Nimitz assigned tactical control of all these to the naval air station commander, Navy Captain Cyril T. Simard, and sent an experienced aviator and a naval base air defense detachment to coordinate air operations.32

While the naval air station directed scouting operations superbly, integrating the bombers in a coordinated strike proved beyond its reach. Each aircraft type attacked without regard to the next, permitting the Japanese the opportunity to fend off each in turn. As Kimes observed in perfect hindsight, “It would have been better had they arrived simultaneously.”33

Coordination was exacerbated by the physical separation of the naval air station and MAG-22 command posts. Simard and his air operations officer were on Sand Island; Kimes and his command post were on Eastern Island. According to Kimes’ executive officer, the “Marines ran their own show” but did not command the other services’ bombers on Eastern Island, including the six Navy TBFs.34

Kimes’ air group struggled to coordinate its own aircraft. VMSB-241 does not seem to have attempted to integrate its SBD and SB2U attacks. Most puzzlingly, MAG-22 allocated no fighter protection to VMSB-241 for its strike against the Japanese carriers.

‘Go All Out for the Carriers’

Kimes employed his fighting squadron in what Marine Corps doctrine termed “general support.” As then–Major William J. Wallace lectured Marine officers at Quantico in 1941, general support was an offensive mission that allowed fighters the freedom to be “on the prowl.” In contrast, missions that tied fighters to protection missions, such as escorting bombers, were termed “special support.” As a fighter pilot, Wallace clearly favored the freedom to go find trouble and emphasized, “The rule, then, for the employment of fighter units should be-—general support wherever and whenever possible.”35

In January 1942, now–Lieutenant Colonel Wallace took command of Marine aviation on Midway, which he retained until relieved by Kimes in April. It was Wallace who had developed the fighter direction system MAG-22 employed for defense of the atoll. As Wallace’s views on fighter employment reflected Marine Corps doctrine, and Wallace commanded MAG-22 until two months before the battle, this bias likely influenced Kimes’ decision to place all of VMF-221 in general support on 4 June.

MAG-22’s fighter employment stands in stark contrast to how Japanese and U.S. carrier task forces operated on 4 June. Carriers were far more vulnerable to air attack than an island base. Nonetheless, every Japanese and American task force commander allocated fighter escorts to increase their bombers’ chances of getting through the enemy’s fighters.

Hitting the Japanese fleet was exactly what Nimitz had in mind when he reinforced Midway with so many aircraft. On 20 May, Nimitz provided the Chief of Naval Operations and Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Fleet, Admiral Ernest J. King, with some views on the role of land-based aircraft he had drawn from the recent Battle of the Coral Sea:

The shore commander should assign attack missions designed to render the greatest possible assistance to the Fleet Task Force when it is engaged and should particularly be ready to provide fighter protection when it is practicable.36

Nimitz incorporated these views in his planning guidance for Midway. In a 23 May memorandum to his chief of staff, Captain Milo F. Draemel, Nimitz explicitly directed that “Midway planes must thus make the CV’s [aircraft carriers] their objective, rather than attempting any local defense of the atoll.”37 In an undated memorandum likely written about the same time, Nimitz reiterated his intent to Captain Arthur C. Davis, his air officer:

Balsa’s [Midway’s] air force must be employed to inflict prompt and early damage to Jap carrier flight decks if recurring attacks are to be stopped. Our objectives will be first—their flight decks rather than attempting to fight off the initial attacks on Balsa. . . . If this is correct, Balsa air force . . . should go all out for the carriers . . . leaving to Balsa’s guns the first defense of the field.38

But in his operations order for Midway, Nimitz was less clear in the tasks he assigned to Simard at Midway:

(1) Hold MIDWAY.

(2) Aircraft obtain and report early information of enemy advance by searches to maximum practicable radius from MIDWAY covering daily the greatest arc possible with the number of planes available between true bearings from MIDWAY clockwise two hundred degrees dash twenty degrees. Inflict maximum damage on enemy, particularly carriers, battleships, and transports.

(3) Take every precaution against being destroyed on the ground or water. Long range aircraft retire to OAHU when necessary to avoid such destruction. Patrol planes fuel from AVD [seaplane tender] at French Frigate Shoals if necessary.

(4) Patrol craft patrol approaches; exploit favorable opportunities to attack carriers, battleships, transports, and auxiliaries. Observe KURE and PEARL and HERMES REEF. Give prompt warning of approaching enemy forces.

(5) Keep Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet and Commander Hawaiian Sea Frontier fully informed of air searches and other air operations; also the weather encountered by search planes.39

The very explicit language Nimitz used in his planning guidance—that Midway’s aircraft “should go all out for the carriers”—is not reflected in his order. Absent such direction, Simard left it to Kimes to command the Marine squadrons as he saw fit. In accordance with Marine Corps doctrine, Kimes placed his fighting squadron in general support over Midway—and sent his dive bombers against the Japanese fleet without fighter escorts. Had he allocated one or two divisions from VMF-221 to escort VMSB-241, more Marine dive bombers may have survived to drop bombs on the Hiryū, and their accuracy may have improved had they attacked with less interference from the Japanese combat air patrol.

Trying to Do More with Less

MAG-22 had not gone all out for the carriers but had massed its fighters in defense of Midway. Naval Air Station Midway had struck the Japanese carriers with every bomber available but had been unable to coordinate their attacks to increase their chances for success and survival. Most tragically, many of the Marines lost in the battle were just not ready to fight the Imperial Japanese Navy, despite their willingness and eagerness to try.

MAG-22’s very bad day is a cautionary tale. Trying to do more with less—in MAG-22’s case, trying to defend Midway while training novice aviators—carries risks that may be hidden until they are exposed through combat. In his report of the battle, Kimes included a page and a half of candid comments and recommendations.40 After Midway, Marine aviators applied the lessons MAG-22 had learned at enormous cost and achieved spectacular results against the same foe in the Solomons, often under the leadership of aviators who had survived Midway.

Those same lessons are noteworthy today. Naval experts have cautioned the naval services against maintaining too much forward presence with too little fleet.41 An enduring lesson of MAG-22 may be that very bad days result from very bad choices, and that choosing to do more with less is often a very bad choice.

13 notes

·

View notes

Video

Replica Nakajima B5N Kate ‘AI-313’ (N3242G) by Alan Wilson Via Flickr: c/n 88-15757 Built as an AT-6D for the US Army with the serial 41-34527. Transferred to the US Navy as an SNJ-5 with the Bureau No 43766. Sold off to a private owner in 1963 and became N3242G. Sold to 20th Century Fox in 1968, she was heavily converted to represent a B5N Kate for the “Tora Tora Tora” movie. The conversion involved fitting the rear fuselage and tail from a Vultee BT-13 Valiant, among other changes. In 1971, after the filming, she was sold to Tallmantz Aviation in California and was operated by them until 1986 when she moved to a private owner in New Jersey. In 2000 she was shipped to Hawaii for the second time and took part in the filming of “Pearl Harbor”, a somewhat less accurate telling of the story she had first filmed thirty years earlier. She joined the Commemorative Air Force in 2010 and is now part of their Pearl Harbour re-enactment group. She is seen on the main flightline during the Commemorative Air Force’s ‘Wings Over Dallas’ WWII Airshow. Dallas Executive Airport, Redbird, Dallas, Texas. 27th October 2019

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

True Hope's Peak Academy: The Reconstruction

SPOILER WARNING FOR PRACTICALLY THE ENTIRETY OF DANGANRONPA!

Deraila looked in the mirror checking if they looked okay. They were nervous as today was a very important day. Her and and their long time friend Luna, were holding a press conference announcing that The Ultimates are alive and well. She didn’t wear any formal clothing as she didn’t have any on hand. All she had was her old Hope’s Peak Academy school uniform, her lab clothes and her casual clothes. She didn’t feel comfortable wearing her Hope’s Peak uniform as it gave her bad memories. Her casual clothes consisted of a dark green tank top, black jeans, green combat boots with black laces, fingerless gloves, and a black leather jacket with green buttons. Her lab clothes consisted some of the same clothes as her casual with the exception of having a stained green lab coat, black t-shirt, and and black vinyl gloves. The two things that she constantly wore with all their outfits was a pair of aviator glasses, a belt with pouches that held two separate packs of gum and a jar of candy, and a beanie.

They decided to go with the casual clothing as those were the ones that she was the most comfortable in and they didn’t know how long this conference was going to be. Luna came in wearing a black suit and tie. “You ready?”she asked. Deraila took a deep breath and nodded. “Ready.” Luna walked around and found Mukuro and Taka. “Mukuro. Taka. It’s almost time for the conference. Mukuro, ensure that your crew is ready to go in case of an attack or an incident happens. Taka, is your speech ready?” Mukuro nodded and went off to check on her crew as they were on security. Taka nodded in confirmation “Yes, my speech is ready. Let us hope we can reestablish our connections with the public and start our crusade to a better future.”

Deraila looked at a nearby clock. It was almost 1 PM which is when the conference was supposed to start. Deraila’s heart pounded through their chest as they walked to the entrance hall. She wondered how many questions would involve her past and the former remnants of despair. She got to the door to the outside. Luna and Taka followed not to far behind. The three of them looked at each other, nodded and opened the giant metal door to the outside. We could hear the loud chattering of world representatives and reporters from inside the building even with the loud whirring of the door opening.

When the door fully opened, their senses were bombarded. Crisp, fresh air went into their lungs, the bright sun nearly blinded them, and the sounds of the outside world rang in their ears. Right in front of the entrance was a large group of people and a podium with a microphone on it. The school grounds, with the help of Daisaku and Santa made the outside of the campus more bright and lively looking with all the flowers and trees that were planted.

Taka walked up to the podium, checked the mic and started to speak. “Hello everyone and thank you for coming to the press conference. My name is Kiyotaka Ishimaru and I would like formally welcome you to True Hope’s Peak Academy. Before I introduce our main speakers, I would like to tell you a few things. One, please be aware of the fact that is you cause any problems, we will have security remove you from the premise. Two, please refrain from taking any photos till the end of the conference. Three, please turn your phone off or on vibrate. Four, be prepared for the conference to move into the building as although we have good security, the protesters could pose a risk to your safety. And five, please hold all unnecessary comments to yourself. Now it would be my honor to introduce our main speakers, Luna Wayne and Deraila Septica. These two have keep the lives of the people in this school. They have helped us in hard times and when the future was bleak and grim and riddled with despair, they helped light the way to where we are now.” Deraila and Luna walked up to the podium. “Thank you Taka. My name is Luna Wayne and this is my partner Deraila Septica.” Deraila had her hand on her belt and was fiddling with a pen. “ To get started, let us tell you what we've been doing in hiding.” A large tv was rolled out and a powerpoint come up. “We have been in hiding for almost 10 years and for good reason. In those years we’ve developed our own society, helped others in need that don’t immediately attack us or those who are in dire need. What had started this happened 10 to 12 years ago on this day. Deraila is here to explained what happened.”

Deraila stepped up to the mic. “Thank you Luna. Before I start, I would like to apologize before hand for what I have done in the past and my actions. Awhile ago for those who don’t know, The Tragedy happened. The Hope’s Peak Student counsel had killed each other in a killing “game” after being shown images that were going to be used to blackmail them. Then one of the students, who I will not name for the sake of privacy, who was being experimented on was shown to the world and the accident was blamed on him. At the same time me and another student were being manipulated into creating the animation “Monokuma’s Gloomy Day” and what you all know as the Despair Disease. These were used to manipulate the reserve course students into attacking the main building. A few days later, the class of 77 had witnessed their class rep, die horribly and this made them spiral into a deep and horrible despair and they became what you will all know as the remnants of despair. From that point on havoc wrecked the world. Cities and even entire countries were wrecked with chaos. But the last glimmer of hope came in the form of the 78th class. These guys locked themselves in and were going to live their lives in Hope’s Peak in peace. At least thats what was suppose to happen. You see we had a traitor among us. This person was the exact same person who had planned the tragedy. While me and luna don’t exactly wish death upon a person, we hope that they are in a better mental state. We were put into a killing game just like the student council were. We were shown images of our loved ones in danger. This caused one of the students to try and lure and attack another. But fortunately we were able to stop them in time. It happened with other students as well but we were fortunate enough that with some help from who some of you will know as the ultimate clairvoyant, to stop these events from happening. We were able to get to the basement, after unlocking the floors. What we had found there was horrifying. We had found rooms designed to kill us. Each one was designed to bring us despair in our final moments. The ultimate clairvoyant upon entering these rooms had visions of what these rooms did and who they were meant for. A animator worked with him and they illustrated them to make these videos”

A video popped up on the screen. It showed the what was in the rooms and then showed a animation of who it was meant for getting horribly killed. The crowd gasped in horror as the video went on. When the video stopped the crowd was murmuring anxiously.

Deraila started to speak again “That was what would of happened if we had not stopped the killings from happening. After that we had started to make a plan to recover our loved ones who were being kept in a apartment building nearby. Mukuro Ikusaba, Mondo Oowada, Sakura Ogami and Luna all planed a mission to rescue these valuable people. When we finally rescued these people, some of them arrived with serious injuries. We treated them the best we could. The adults of the group became the council of our society in the beginning. We decided to rescue our fellow ultimates or anyone who had been under attack from what people had called ‘ultimate hunts’. These were conducted in case anyone was found or even seemed like they would have a ultimate talent. With the help of Mondo and Mukuro, they when on rescue missions across the country and even the world to rescue these people and to ensure that they got back safely. They built up their own teams, with two of them being the captives. Of course we couldn't do this with out sponsors. Luna and Togami had connections to many people and they helped us get to were we are know by helping us by giving supplies, giving us rides to the places that we need to get to and helping us build new parts of the school. Eventually we recovered the warriors of hope and the remnants of despair and helped return them to a some what normal state. At the time though, we still didn't have any recollection of what happened in years past. In order to do that, I had to make a modified version of the Despair disease strain, The remembrance disease. From that point on we recovered more ultimates and people who under attack by these ultimate hunts. Then fast forward to a week or two ago when we decided to reconnect full with the outside world. I’m going to hand it back over to Luna.”

Deraila walked back and grabbed a piece of gum out and chewed it anxiously as Luna took the podium again. “Thank you before we get to questions, i would like to thank our security lead by Mukuro Ikusaba and her right hand woman Kanon Nakajima, for keeping watch and ensure that we are safe Now any questions?”

(use the askbox to ask questions)

#Dangan Ronpa#danganronpa#danganronpa 2#danganronpa thh#thh#danganronpa goodbye despair#goodbye despair#danganronpa au#ultra despair girls#long post#dangan ronpa#udg#udh

4 notes

·

View notes