#my uncle sent me a book that came out in paperback a few months ago

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

does anyone else get disproportionately stressed out by being given a book they already own. it's like... objectively not a big deal! i can give it away! but also somebody thought of me, and spent money on me, and i cannot benefit from the thing they have given me (even though they objectively got something right because it interests me enough to have bought it already) so i feel both ungrateful and also a little sad that i do not get a new book (and then feel guilty for being sad because i was not, like, entitled to a new book) and oh no those are bad emotions and a gift should be good emotions, help

#my uncle sent me a book that came out in paperback a few months ago#but it's so much my thing that i already bought it in a-format early last year when it came out#and i do not really need two copies#but it's fairly niche so tricky to pass on#in the card he sent he was literally like 'if you've already read this then pass it on to someone'#so there is no reason to feel guilty! and yet! he paid money for a book for me and i already have it!#personal

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

A LIFE WITHOUT STAN LEE? -- Part One

This is the first month of my life without Stan Lee alive in it.

I think it’s appropriate to post this essay today, on Stan Lee’s birthday, the first one without him actually here to celebrate it. I couldn’t bring myself to write about Stan the day he died, just shy of 96 years old, and the week and month that followed were no better. Today I can put down some thoughts.

I am a child of Stan Lee. His work with Jack Kirby and John Romita appeared in the first comic book I remember reading – the Marvel-produced America’s Best TV Comics, a 25-cent comicbook that promoted the ABC Saturday morning cartoons. It's one of the first powerful memories of childhood that have stayed with me for all this time.

Across my formative years, Stan Lee's words encouraged me to learn, to read more of everything -- not just comics. I spent much of my early years in the library and ordering Scholastic books every month through school. I read everything -- fiction, biographies, histories, science books.

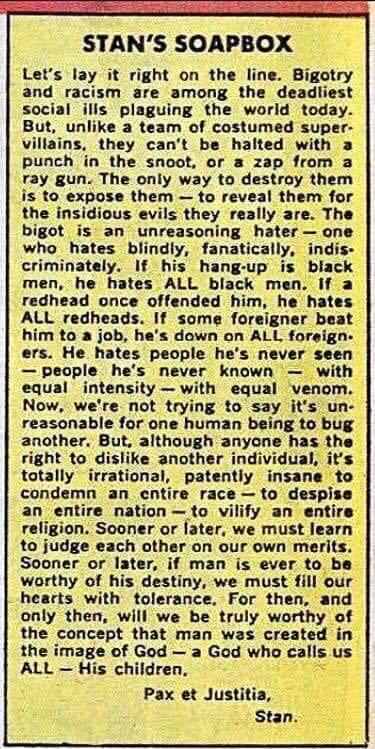

Yet I grew up loving the comics that blazed brightly with his public persona and, while my parents toiled at just earning a living and staying alive, I learned much from "The Man." Stan taught me a lot about being a decent human being. It wasn't all, "With great power there must also come...great responsibility," though that was there, as well.

In recent years we corresponded a bit about the morals and messages of his words in his scripts, his Stan's Soapbox, and his many lectures and interviews. I told him we should assemble a book, Everything I Know, I learned From Stan Lee.

He wrote back -- "The paperback you suggested, 'Everything I Know I Learned from Stan Lee,' sounds like it could be funny. Especially if it consists of only one page with only one thing learned -- how to spell 'Excelsior!' Keep the faith, David. You're one of the good guys! Excelsior! Stan"

We discussed it a bit more but, soon after, Stan's eyesight worsened and he stopped answering his own mail; whoever took over had no idea what we'd been talking about. I let the idea drop.

Back when I was 12, I decided my career goal was to work with Stan Lee. Eventually, I achieved that goal but not by submitting stories in my teens and 20s but much later in my life, as an agent and book author. By the time I was 14, he'd gone from editor-in-chief to Publisher -- which meant he'd need more writers, right?

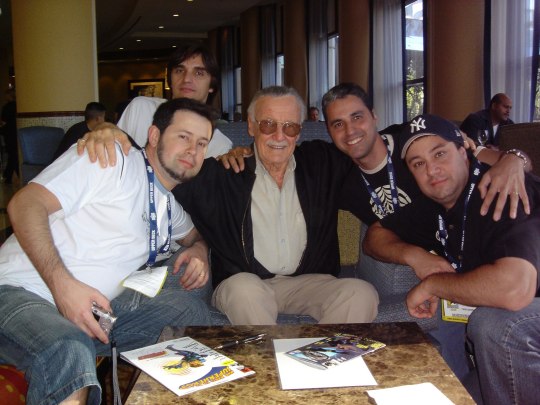

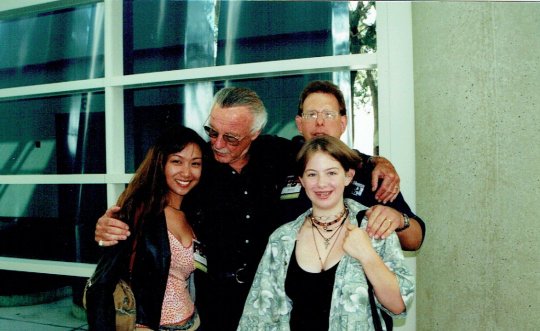

The first time I met Stan Lee and got to take a photo with him, I looked up at him and said, “Smile, and look as much like my Uncle as you can.” He laughed and gave my artist friend Scott Rockwell and me a good half-hour of his time, looking at art and answering questions. That was in 1978 – fully 40 years ago – and I remember it all as if it were yesterday. Stan was a memorable guy who could make you feel like the most important person in the room. I only wish I still had that photo; maybe Scott has it buried somewhere.

Four years later, I sold my first professional comics scripts to Pacific Comics and two years after that was writing a Superman assignment for DC with Kevin Juaire. Instead of ending up at Marvel as I’d hoped – which would’ve required moving to New York and being involved in daily office politics – I became a comics packager, then a publisher, then an agent. That’s how Stan knew me professionally, as a writer and an artist’s agent.

In early 1989, at a Capital City Distribution trade show, my Innovation Publishing was set up promoting the books we would be releasing into comics shops in a few weeks. Stan was walking by, and I suggested to my assistant Paul Curtis that we should invite Stan to dinner. He ran over, asked, and Stan said yes! He not only brought along Carol Kalish and regaled us with two hours of stories about life at Marvel, Stan insisted that Marvel pay for the meal! Nobody thought to bring a camera, but the memories stayed with us. As I recall, Steve Sullivan, Paul Curtis and his girlfriend Amy, and I were the happy Innovation team at that dinner. Kevin VanHook came on the trip but was elsewhere at that time. He made up for it later at a party by chatting on a couch with Stan and later dancing with Carol.

In the '90s, Stan and I would chat at every opportunity at conventions.

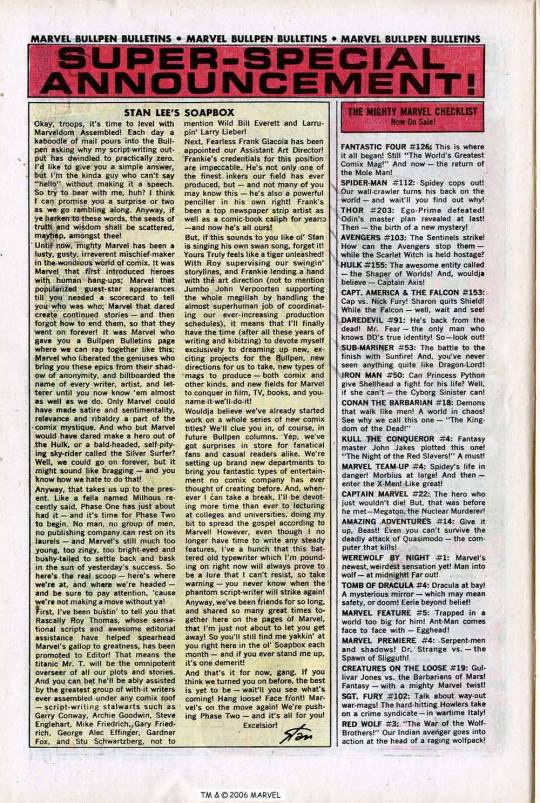

When Marvel released a limited edition hardcover reprint of his 1947 book Secrets of the Comics, I decided to give in to my fannish impulses and use its endpapers as my autograph book.

Stan, of course, was the first to sign it in 1996, and a batch of Silver Age stalwarts followed.

By then we made it a point to get photos together every year across two decades. It was a clear timeline of the both of us getting older.

As the internet blossomed, I helped Stan a little when he first joined AOL. He asked me how AOL Instant Messenger worked, how to turn it on when he wanted to communicate and off when he didn’t want to be bombarded with Messages, and so on. Another time, an article he wanted to read was behind a login/password, and he asked me help get him through that. It tickled me to help Stan “The Man” with such basic web-things.

From the mid-'90s through the early 2000s, Stan would call the Glass House offices about once a month to ask for my perspective on what was going on in the comics biz, since we dealt not only with all the Marvel editors but everyone else as well. Real conversations, not the "'Nuff said, Pilgrim!" stuff. He'd graciously take an extra few minutes to chat with my assistant Graeme, who loved talking to his childhood icon.

Around 1997, Marvel's savvy publisher asked Glass House to create two dozen project proposals for a line of second-tier titles that my company would package. We ended up over-achieving and submitted 28 of them -- one of them for the first-tier Fantastic Four that I understood we had little chance of getting, but I had to try. The art was Joe Bennett's doing a Kirbyesque style.

Stan was kind enough to read over my FF proposal/outline and fine-tune my dialogue for the pages, before I submitted.

Likely worried about how an outside packager controlling so many titles would affect his own position, the editor-in-chief buried all 28 projects until, two years later, he assigned an editor to reject every proposal outright; that editor told me my FF dialogue didn't capture the essence of the characters -- not realizing the words were Stan's.

(Sidebar: It was so ridiculous, that editor even rejected a proposal that another Marvel editor already saw, bought, and published!)

When Meryl and I got married in 2001, Stan sent us a gift -- a lemon cake and a note saying he wished he could've made it to the wedding. We still have the note; we ate the cake.

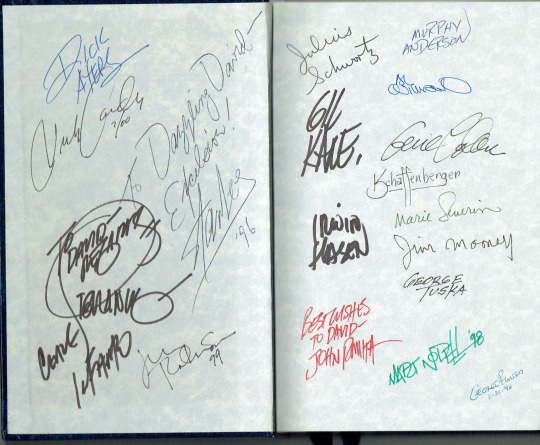

In 2006, Stan's POW! Entertainment launched Who Wants to be a Super-Hero? on The Sci-Fi Channel, and my Glass House Graphics contributed all the cover artwork for both seasons of the TV show. We even drew the comicbooks that starred both winners -- Matthew Atherton and Jarrett Crippen, both of whom became our friends.

When my friend, then-GHG artist Will Conrad, worked with him on the Dark Horse Feedback comic book, Stan took the time personally to choose Will out of our roster of artists, and to phone him in Brazil for a long talk before sending him the plot. (And yes, it was a full page-by-page plot.) They spoke several times during Will's month working on the book, each time helpful and upbeat.

The second book, with The Defuser, was more problematic. The network and producers weren't honoring their commitments to the winner, so I reached out to Stan who said, "I don't see any compelling reason to bother doing it, since we weren't renewed for a third season." I replied, "Because you said you would? Because you have the power to do it, and with great power there must also come great responsibility?" He made it happen, and Glass House Graphics's Kajo Baldissimo did the art.

We also drew the box art and insert comic books for multiple DVD animation projects that POW! released, with art by GHG's fabulous Fabio Laguna.

Stan always made time to meet privately with my artists, and my family, for which I was always grateful.

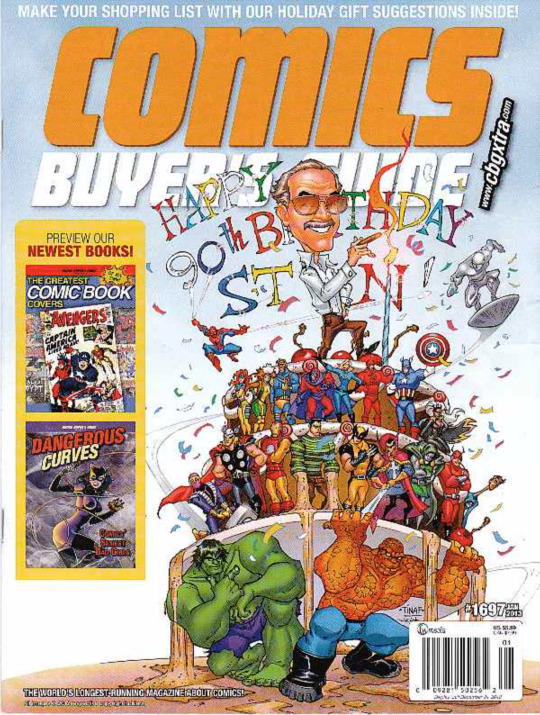

Of course when Comics Buyer’s Guide published a big feature issue for Stan’s 75th Birthday, I contributed an essay and hired the great Marie Severin to do a caricature cover for it and sent Stan a giant print of the art.

Around the time of Stan's 90th birthday celebration, I had Tina Francisco create a new birthday cover for Comics Buyer's Guide, and I penned a long article about him, too.

Of course, we sent to Stan a poster of the color art, and he sent back this card -- as always, written in his own handwriting.

TO BE CONTINUED -- IN PART TWO!

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

In the summer of 2013, my husband Josh and I flew to Uganda to adopt two small children, a brother and sister, ages 3 and 5. We spent 5 weeks learning, crying, laughing, and praying as we navigated the process of legally adopting and making these kids our own.

We sat in front of a judge, we waited for new passports, we took the kids to have medical examinations and TB tests and we amassed two massive folders of paperwork that basically said, “these two Mzungus (white people) can take these kids home with them.”

In the meantime, our two biological daughters, then 3 and 4, were back at home hanging with their grandparents and aunts and uncles, missing us, but generally enjoying life as they swam and played and were doted on.

Even now, as I look back on that month, my stomach twists as I remember just how incredibly terrified I was. In the lovely videos and pictures that people post, it always appears that adoptive mothers are confident, brave, strong, and loving. I was anxious, fearful, and desperate.

Why on earth did God call me, of all people, to this? And how, how, are these strangers to become my children? What are we DOING?

But of course, time moved us forward. We came home, and the process of bonding and adapting began. In truth, the transition was easier than I had anticipated. Within six months the language changed from Luganda to English. The kids were siblings. God created a new family, and we rejoiced.

Now, four and a half years later, we have a lot of great memories to look back on. We have four funny, crazy, precocious children. They laugh and play and fight with the best of them. Oh and now that the girls are getting older they feel. ALL THE TIME.

We get to see the wonder of children who accept adoption, and having siblings of another ethnicity, as the norm. And it’s beautiful. Like when our Charlotte was asked by a classmate how he was her brother. And she responded in confusion, “Uh…because he’s my BROTHER.”

Or when my brother and his wife, both white, had a baby and our Eva was genuinely surprised that the baby was white. Because in her mind, white parents can have black children and that’s that.

But all beauty and bonding and lovely stories aside, these years have been HARD. We’ve seen psychologists and battled severe educational delays. I’ve had anxiety attacks and discovered the anger issues I thought I had so tightly reined in resurfaced with a quickness.

Discipline has been a total crapshoot, like throwing spaghetti against the wall to see if it sticks. Will this work? How about this? Maybe this? All the parenting lessons we’d learned – out the window.

We experience the inevitable effects of abandonment, neglect, and the death of a parent. We must reassure again and again and again and again and again. We are in over our heads.

World Adoption Day and Orphan Care Sunday were both several weeks ago, with both striving to draw attention to the need for, and beauty of, adoption, fostering, and orphan care; I thought it an appropriate time to share a bit of our own story. But beyond that, I want to share a few of the lessons we’ve learned.

Recommended resource:

Sale

Adopted for Life: The Priority of Adoption for Christian Families and Churches (Updated and Expanded Edition)

Russell Moore - Publisher: Crossway - Edition no. 0 (10/31/2015) - Paperback: 256 pages

$17.99 - $4.10 $13.89

We’re only four years into this thing, so I’m sure these lessons will change or become obsolete as our experience grows and deepens. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t relevant today, and hopefully they’ll bring some encouragement to those who need it.

We Are Not Awesome

Something interesting happens when you decide to adopt. People think you’re amazing (not the people who really know you. They’re not fooled). But the typical bystander thinks you’re brave and selfless and spiritually deep. They think you have a superpower that they just don’t have. They say things like:

“You guys have such big hearts.”

“Those kids are so lucky to have you.”

“Wow, I don’t think I could ever do that.”

Because we are fallen creatures and pride is our natural fleshly bent, I can’t tell you how easy it is to begin to believe this. “Man, we ARE awesome. Look at this beautiful thing we did. Go us.”

Here’s the hard-learned truth, though. We are as sinful and as in need of the gospel as we ever were. We are sinners who adopted kids. That’s it. If our hearts are big, it’s because our God has enlarged them with his indwelling presence. Any good in us comes from Him.

Our kids aren’t “lucky.” They are sinners living in a fallen world, too. They, too, need the blessing of salvation even more than the blessing of food and shelter and love.

As far as whether or not anyone else can do this: who are we to say? It’s funny to watch people get so nervous when talking to us about adoption, as though we think everyone everywhere should do it. If anything, we are very familiar with what a life-altering, difficult decision it is.

I think that in order for the church to really embrace adoption and foster care, we must do away with this notion of “special” people being called into it. It’s become an easy thing to point to in order to avoid really praying about and considering it. It also sets adoptive parents on a pedestal, which they certainly don’t need.

Normal sinners adopt. God is the one who works the miracles that make it possible.

We Are Not Owed Anything

As a Christian, I believe that adoption is an earthly shadow of what our Heavenly Father did for us when He sent His son. The Bible says in multiple places that when we call on Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior, we become adopted children of God. We are co-heirs with Christ, born again into a new life.

I think we can all get our heads around that imagery when we see the adoptive parents drawing their new children into their arms, removing the label of orphan and giving new identities and new lives.

However, where I’ve really seen the gospel picture most clearly is in the worst moments. I’m ashamed to admit it, but deep down there was something in me that felt I was owed something. What I never say out loud, but feel deep down, is, “How could you doubt that I love you? Don’t you see all that I’ve done for you?”

Where is God’s love most clearly displayed? “God demonstrates His own love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us.” He saves the prodigals, the children who say again and again, “You don’t really love me. I don’t believe you.”

That’s adoption. Just like the Israelites in the wilderness looked back on Egypt with longing, so the orphan will doubt the parents’ goodness again and again. So we doubt God’s goodness again and again.

Recommended resource:

Sale

God's Very Good Idea: A True Story of God's Delightfully Different Family

Trillia Newbell - Publisher: The Good Book Company - Hardcover: 32 pages

$14.99 - $1.50 $13.49

If I respond as I ought, it’s because He supplied the ability to do so. If I doubt Him and refuse to obey, He welcomes my repentance and bestows mercy and grace once more.

This is what it is to adopt a child. Orphans are needy and desperate they will rely on your kindness and grace repeatedly. Don’t put a burden on them that your Father in heaven has lifted from your own shoulders.

This not only applies to our children, but to others as well. Too often I’ve read blog posts by adoptive parents that demand that other people “get it,” or tiptoe around their experiences. I find this to be fairly unhelpful. It’s a given that others will have questions, and sometimes express those questions in unintentionally awkward ways.

Be gracious, be kind, and remember how many stupid questions you’ve asked in your life. Little is accomplished by expecting one with no experience in orphan care to meet your standards.

There Is Only One Expert

Look, guys. You can read a million things about how to adopt well. There are huge books written on the subject. There are guidebooks and memoirs and stories and blog posts and articles. Some of it may be helpful. Some of it, not so much. In the end, here’s what I know. You are a unique parent to your unique children.

This is true for biological and adoptive parents, but I think is an especially important thing for parents of adopted children and special needs children to understand. The one who knows your child best is God. Then after that, you.

Learning this lesson doesn’t mean we haven’t sought professional help. In fact, we have. We’ve gotten so much from it. We’ve also learned that even with all of the research available, the experts don’t totally understand what childhood trauma does to development. But there is an all-knowing God who does understand everything that we don’t.

In our desperation to always know and control, we can forget that we must trust God and allow Him to speak and instruct. He does this through His church, His Word, and His Spirit. He also does it through the provision of experts and professionals, but those shouldn’t replace the three primary sources of His grace, but rather supplement them.

His Grace Is Sufficient

Perhaps this is the lesson of every parent, but I’ve found it to be particularly true as I’ve entered into brokenness and murky histories and baffling behavior. I am not enough for the task. No adoptive parents are. But the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ is.

Where I succeed, his gracious provision has made it possible. Where I’ve failed, He’s showing my need for it all over again. Most of the time I feel like a huge mess, navigating a hopeless parenting labyrinth. Thankfully, the end is clear and bright, and it’s not up to me to get myself there.

There are no guarantees of wonderful, well-turned out children, biological or adopted. But the grace of God to walk through whatever is coming is a sure and steady promise.

The post When Sinners Adopt It’s Beautiful…and Really Difficult appeared first on The Blazing Center.

0 notes