#my transcription

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

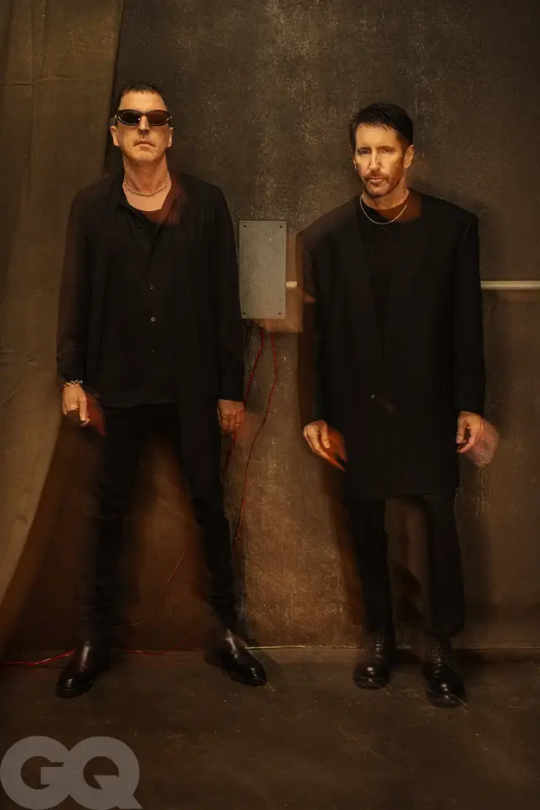

Photos by Danielle Levitt for GQ, in a now-deleted article.

GQ Article

Outfit details:

Photos 1, 6, 8, and 11: On Trent Reznor: Coat by Faqtpry. T-shirt by Calvin Klein. On Atticus Ross: Jacket by Faqtory. Photo 2: Cape by Dolce & Gabbana. Turtleneck by Ralph Lauren Purple Label. Ring (on left ring finger, throughout) his own. Ring (on left pinkie, throughout) by Møsaïs Paris from Voyager Archive.On Atticus Ross: Shirt by Willy Chavarria. Jeans by Ralph Lauren Purple Label. Boots by Christian Louboutin. Sunglasses by Gentle Monster. Necklace, bracelet, and ring (on right ring finger, throughout) by The Great Frog. Ring (on pinkie, throughout) by Parts of Four from Voyager Archive. Ring (on left ring finger, throughout) his own. On Trent Reznor: Jacket by Canali. Shirt by Rick Owens. Trousers by Ralph Lauren Purple Label. Boots by Balenciaga. Necklace from Voyager Archive. Ring (on right ring finger, throughout) by The Great Frog. Photo 3: Cape by Dolce & Gabbana. Turtleneck by Ralph Lauren Purple Label. Ring (on left ring finger, throughout) his own. Ring (on left pinkie, throughout) by Møsaïs Paris from Voyager Archive. Photo 4: On Trent Reznor: Coat and trousers by Willy Chavarria. Sweater by Diesel. Boots, his own. On Atticus Ross: Jacket by Versace. Tank top by Junya Watanabe Man. Trousers by Fear of God. Boots by Gianvito Rossi. Sunglasses by Gentle Monster. Watch by Hublot. Ring (on left hand), his own. Bracelet and ring (on right hand) by Eliburch Jewelry. Photo 5: Jacket by Bottega Veneta. Sweater by Zegna. Sunglasses by Barton Perreira. Wallet chain (worn at neck) by Martine Ali. Photo 7: On Atticus Ross: Coat by Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello. Scarf stylist’s own. Sunglasses by Ahlem. On Trent Reznor: Jacket by Dolce & Gabbana. Sweater by Ferragamo. Necklace by The Great Frog. Photo 9: Jacket by R13. Tank top by Givenchy. Trousers by Ralph Lauren Purple Label. Boots by Balenciaga. Photo 10: On Atticus Ross: Shirt by Willy Chavarria. Tank top by Junya Watanabe Man. Jeans by Ralph Lauren Purple Label. Boots by Christian Louboutin. Sunglasses by Gentle Monster. Necklace and bracelet by The Great Frog. On Trent Reznor: Jacket by Fear of God. Shirt by Rick Owens. Trousers by Ralph Lauren Purple Label. Boots by Balenciaga. Necklace from Voyager Archive.

483 notes

·

View notes

Text

A partial transcript of Greg and Alex being perfectly normal about each other:

We’re just more comfortable, I suppose, next to each other and in front of those people.

And we- and we know each other. We’ve holidayed, Brittany, and I think that- that changes everything.

Oh, and it was a big holiday.

When two men holiday- Mm. -that’s when, that’s when chemistry is formed.

So what’s the biggest thing either do you have learned about each other, then, through that process? Has there been anything that’s really surprised you?

I’ve learned that Greg operates horizontally for 23 hours of the day.

[wheezing laugh] That- that is true. I mean, it’s not relevant to the show.

Oh oh, to the show? No.

Not allowed to lie down on the show. I’ll tell you what I’ve learned about Alex, and I’ve mentioned it in a couple of interviews because I am intrigued by it, and it took me a few years to realise it. And it is that Alex is- will never say no if you challenge him to do something. And I don’t mean on camera, I mean, you know, at any event you can tell Alex to do something on a dare, and he’ll do it. And I find it endlessly endearing. And I think you know he comes across as an officious nerd, but- H-hello. -beneath that, he’s actually- he’s actually quite a lot of fun, Alex.

[honking laugh] yes. And I’ve learned that Greg is- will come with me on these escapades, and is also fun. But also, and this- he won’t necessarily like me saying this, but he is very funny uh, and, uh- [laugh] I will like you saying that. Well I think that Greg’s got like in the studio, you don’t really like it when people aren’t laughing and this is very useful quality as a comedy TV host.

I don’t- I don’t like it, and it’s a sort of sad cliche of comedians, really, we don’t- we can’t stand silence and a lack of merriment. And so I think the studio records of Taskmaster- I hope if you asked, most people who have been there in the audience would say that they get more than just the show, they get more than just what you- what you see, the edited final show. I think it’s genuinely quite chaotic and immersive in the studio. And I love that.

-

This interviewer takes a bit to warm up, but Greg and Alex are obviously both excellent at putting people at ease- Alex is always so endearingly earnest and I felt like Greg’s determination to make her laugh was palpable. They really both seem so kind and their chemistry was on point.

Also in the podcast: Greg claiming Alex’s currently barking dog doesn’t exist, them being very sweet and appreciative of their fans, Greg and Alex’s M-rated (for very different reasons) Taskmaster spinoff ideas, discussion of their #1 pick for contestant who has been rudely ignoring their calls, what the show has caused them to learn about themselves, and my favourite- Greg turning on his teacher voice at the interviewer at the end.

I am honestly considering putting “I’m not interested in logistics” and “Listen. Don’t make excuses, just deliver” in a button to press when my executive is not functioning. That feels like it would be quite motivating.

#taskmaster#alex horne#greg davies#taskhusbands#wholesome#interview#dynamic duos podcast#podcast#my transcription#my thoughts#ody does it

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ballister: "do you think he saw us?"

Nimona: *peers out the window*

the knights: *aims crossbows at her*

Nimona: *ducks back under*

Nimona: "yes."

---

my music juices are drained already and ive only transcribed the first three barsssss arghhhhh

although i only choose to do "last stop" purely for how iconic the first bit is XD

#my transcription#music#nimona#nimona soundtrack#i fcking love bal in that scene#HE'S SO GOOFY I LOVE HIM <3#and ambrosius only recognising its not ballister only cause of “he hates freestyle jazz” like pleaseeeeeee lmao#darcy daydreams

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Closed Captions for Quackity's June 19 QSMP stream / Subtítulos cerrados para el directo de Quackity del 19 de junio

English closed captions here

Subtítulos cerrados en español aquí

Untranslated closed captions here/ Subtítulos cerrados sin traducción aquí

Portugese transcription and translation by the wonderful @al-pomegranate-seeds English and Spanish: meeeee :3 with help from @greenscreen-dress

other streams i have captioned can be found in my pinned!

(please consider reblogging, i spent a lot of time on this and i want people to see it)

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

"We call it “Radical Right”; and, of course, that term is just how we are understood in the mainstream. But really, what we should be calling it is the Deep Center. Kind of the opposite. It’s because we are the historical default. We are the null hypothesis against which liberalism needs to justify itself. Because liberalism going all the way back to Classical Liberalism — which it’s my belief that it has only just now worked its way to its true, what it actually entails — this ideology is the most extreme ideology in the history of the world, and for it to call itself “the center” is absolutely absurd. What we call our liberal “tradition” is just as revolutionary as Bolshevik communism, and more. It contains communism, and it contains worlds inside of itself that have only now just kind of come to fruition. So, we are the real center, and liberalism essentially needs to justify what it wants to do against us."

—Mike Maxwell

#quote#youtube#see link for context#my transcription#some 'um's 'er's and other verbal filler omitted

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Closed Captions for "Quackity Loses His Memory on the QSMP" / Subtítulos descriptivos para "Quackity pierde la memoria en el QSMP"

English closed captions here Subtítulos descriptivos en español aquí Untranslated captions here / Subtítulos descriptivos sin traducción aquí

You can find all the streams I've captioned in my pinned / Se encuentran todos los subtítulos que he creado en mi publicación fijada

Portuguese transcription and translation by @al-pomegranate-seeds French transcription and translation by @greenscreen-dress

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do not write fanfiction. One second you're normal and the next you're downloading a calendar from 2004 and tearing your hair out over what specific date every event in your fic happens

#yes this is my current literati fic#gilmore girls#literati#writing#I now know way too many specific dates of things that happened in season 4 & 5#all industriously puzzled out via transcripts and wikis and my own sleuthing skills#what an excellent use of my time i agree

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross have a plan to soundtrack everything

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross – best friends and Nine Inch Nails bandmates – found unlikely creative fulfilment (and a couple of Oscars) by reassessing what they had to offer as musicians. Now they’re thinking even bigger, and imagining an artistic empire of their own making

By Zach Baron

Photography by Danielle Levitt

Every weekday, Trent Reznor makes his way from his house, a cottagey sprawl behind a white wall in a canyon on Los Angeles’s Westside, to a studio he’s built in his backyard. There he meets his best friend, bandmate, and business partner, Atticus Ross, and they get to work. Reznor and Ross observe the same hours, Monday to Friday, 11am to 7pm. “We show up,” Reznor told me. “We’re not late. We’re not coming in to start to fuck around.” It’s a methodical, orderly existence that Reznor could not have foreseen in the ’90s, when he was fronting Nine Inch Nails and struggling with a drug-and-alcohol problem that was his answer to success. “I would do anything to avoid writing a song,” Reznor said. “I’d rewire the studio 50 times.”

Now Reznor has a wife, Mariqueen Maandig, five children, and multiple jobs. He is sober. Since 2010, when the director David Fincher asked Reznor and Ross to score The Social Network, for which Reznor and Ross won an Oscar, the two men have had steady employment composing for film. This year, Reznor and Ross are also starting a yet-to-be-named company, built around storytelling in multiple disciplines: film production, fashion, a music festival, and a venture with Epic Games.

And then, of course, there is the oldest and perhaps still the most complicated of Reznor’s jobs: being the frontman of Nine Inch Nails. In 1988 Reznor formed what was then a one-man band; the first two full-length records Nine Inch Nails released, Pretty Hate Machine(1989) and The Downward Spiral (1994), have sold more than eight million copies. (Over subsequent years and subsequent albums, the band has since crossed the 20 million mark in sales.) In the ’90s, for a time, Nine Inch Nails were ubiquitous: a phenomenon on the level of Nirvana or Dr Dre. During that decade, the success of the band nearly killed Reznor. “I didn’t feel prepared to process how disorientating that was,” he said. “How much it can distort your personality.”

These days, Nine Inch Nails, which Ross joined as a full-time member in 2016, present a different problem – how do you make something old, something so already well-defined, new again? There are years when Reznor feels like he has the answers and years when he’s less certain. He has put the band on hiatus more than once; after the last Nine Inch Nails tour, in 2022, Reznor deliberately took a break from playing shows as well. “For the first time in a long time I wasn’t sure: what’s the tour going to say?” Reznor told me. “What do I have to say right now? We can still play those songs real good. Maybe we can come up with a new production. But it wasn’t screaming at me: this is what to do right now.”

But he and Ross still come to work, daily, in search of transcendence. “We sit in here every day,” Reznor said. “And a portion of the time organically becomes us just figuring out who we are as people and processing life and a kind of therapy session. And in those endless hours it’s come up: why do we want to do this? And the reason is because we both feel the most in touch with God and fulfilled.”

It is easy to make things when you are a teenager growing up in rural Pennsylvania, near the Ohio border, as Reznor was, and you have nothing to lose and everything to gain; it is considerably harder, once you’ve got older, and found a way to make things that people like, to keep going. It’s an old story: the act of creation can lift you up, but those sharp gifts can also destroy you, and if you make it past that, the sheer blissful regularity of life with money and a family can even you out so thoroughly that there is no friction left to work with. You look inside the cupboard and the cupboard is bare, or it’s a mansion and living inside of it is a person you’re bored of, and so you stop looking. But Reznor and Ross have never stopped looking, and the search for that magical feeling of finding something – that feeling of, in Reznor’s words, “I don’t know where it came from. I don’t know how I just did what I did, but I’ve channelled it into something that worked” – is still the thing that organises their days and their moods.

We were talking in their studio, which was low-lit and cold and full of synthesizers’ blinking lights. Reznor was on a sofa and Ross sat in a chair nearby. The two men first met in the ’90s, when Reznor signed Ross’s band, 12 Rounds, to Reznor’s Nothing Records. Soon after, they became friends, and then musical collaborators. “I was just getting sober,” Reznor said, “and I was in a pretty fragile transitional phase. And I just hit it off with Atticus right off the bat. And part of it was, he was someone who was on much firmer ground, in a mentor-y kind of way, than I was.”

Ross is two years younger than Reznor, but when they met, he’d already been through certain things Reznor was just getting around to. “I got clean when I was very young,” Ross told me. “So I had a bit more experience than him. Put it like this: I knew you could have fun without being high.”

Their friendship has been a constant in both their lives since. “I don’t know if parts of us are broken and we don’t feel good enough,” Reznor said, staring at the ceiling of the studio, “but we know if we work as hard as we can and do the best work we can, it fixes something. At the core of it, that’s what unites us creatively. On top of that, I think his take on the world and role in life helps me understand my place and not feel as detached in some ways.”

Reznor often jokes, or simply explains, that he is a “quart low” on whatever it is that makes people happy. “I think we can both, on our own devices, run below zero as a baseline,” Reznor said. “I don’t mean manic depression, I just mean we don’t take compliments well. It’s like when we won the Oscar, it was the day after: ‘Let’s take today guilt-free, kind of say fuck yeah.’ And tomorrow we’ll have settled back down to a few feet below sea level.”

In their years of collaborating with each other, both men have found some mutual reassurance – a little lift. Reznor gestured at Ross.

“I remember something he said to me – I don’t know if you want me to say this or not – in one of our talks years ago: ‘Here’s what I want today.’”

“I see what’s coming,” Ross said, nervously.

“I just want to feel OK,” Reznor said, quoting his friend. “I want to feel like I’m OK.”

One day this winter, Reznor greeted me at the door of their studio – in the course of reporting this story, I never saw him anywhere else – wearing a black hoodie made by the synthesizer company Moog, black jeans, and black running shoes. At 58, Reznor still retains the angular intensity and jet-black hair of his youth, but time and fatherhood seem to have made him quicker to smile. He looks a little like a college professor now, or an unusually-well-cared-for software engineer. He led me back, past walls of unused gear and several black-clad mannequins, all of which startled me, to their primary workspace, where Ross – a tall west Londoner (he grew up in Ladbroke Grove) with a stern face and a pleasantly reedy voice – sat at a computer, also all in black. (Once, I asked the two men whether their upcoming clothing line would feature any colour. “No,” Reznor said, incredulously. “Of course not.”)

They were on deadline for two films at the moment, including Luca Guadagnino’s forthcoming Queer. “But we’re trying not to work,” Reznor said, drily. Leaned up against one wall was a photo of the two in tuxedos, accepting the Academy Award for best original score for their work on The Social Network. Reznor had contributed to soundtracks before, in the ’90s, but he’d never formally scored a film until The Social Network.

But Reznor and Ross quickly realised that the work, in some ways, wasn’t so different from songwriting. “What do we do when we write a song?” Reznor asked. “We’re trying to emotionally connect with somebody.” Take the Mark Zuckerberg character in The Social Network:“Here’s somebody who thinks this idea is so important that it’s worth kind of fucking your friends over for it. And then realising maybe it wasn’t worth it, or I didn’t realise how I’d feel if I got what I wanted at the price of this. I can relate to that in my own language. Suddenly there’s music.”

“I’m grateful not to be as angry and frustrated and desperate as I have felt in the past,” Reznor said. “I couldn’t have predicted that I would feel this level of fulfilment.”

And Reznor found that he enjoyed the exercise of solving someone else’s problems instead of his own. “There’s something about not being the boss and working again in service to something that I initially felt guilty for feeling kind of fulfilled by in a weird way.”

Reznor said that on another Fincher film, Mank, the director suggested: “What if it sounded like maybe inspired by Bernard Herrmann and as if it were recorded in 1935 and this film canister sat on the shelf for 60 years?” OK, interesting. (Ross and Reznor were nominated for that one too.)

On the first film the two men scored for Guadagnino, Bones and All, “we got a cut of that that was nearly four hours long with no music and we kind of thought, Oh, fuck,” Reznor said. “Four hours we sat without a pee break, transfixed. It didn’t need music. And when you watch that you approach it differently.” Then Guadagnino brought them Challengers, due for worldwide release in April. Reznor said, “He started us down a path, saying, ‘What if it was very loud techno music through the whole film?’” (This is exactly what it turned out to be.)

“I wish I had his notes,” Ross said of Guadagnino. “His notes were so fucking funny on what each piece was meant to do.”

“Oh, yeah,” Reznor said. “‘Unending homoerotic desire.’ It was all a variation on those three words.”

They liked the challenge of scoring, they found, and that feeling of not being in control. They also liked the way it made them crave being in control again: “It makes you more inspired to work on other stuff when we’re finished,” Reznor said. “Even if it’s just, Thank God it’s done now and we can appreciate the freedom we had before we gave it up.”

These days, Reznor and Ross also like having jobs that let them be at home, around their families. Both men had tumultuous or lonely lives when they were younger; both men have found that fatherhood soothes certain unresolved aspects of their pasts. Ross has three kids, and “probably the greatest reward is how balanced and happy they all are compared to – certainly my growing up was an unusual sort of scenario. It was a fairly chaotic youth.” Ross comes from a notable English family, but his immediate lineage was more unstable. “My dad had a club called Flipper’s Roller Boogie Palace in LA in the ’70s,” Ross told me. “He went bankrupt in England and had a judgment passed against him where he couldn’t talk to a bank manager for 15 years. So he moved here and opened this sort of Studio 54 on roller skates on La Cienega and Santa Monica.” Ross held up a coffee-table book full of photos of the club. “You don’t need to look at it, but it was just a mad life. So I grew up in some madness.”

It is particularly endearing to see Reznor, who at a distance was a fierce and terrifying figure in his 20s and 30s, find domestic bliss. I am old enough that my adolescence coincided neatly with the S&M-flavoured, I wanna fuck you like an animal era of Nine Inch Nails; when I was leaving Reznor’s house one day, I noted with some amusement the cheerful mundanity of a basketball hoop in the backyard. “I’m grateful not to be as angry and frustrated and desperate as I have felt in the past,” Reznor told me. “I couldn’t have predicted that there was a world where I would have a sizeable family with kids and feel the level of fulfilment and comfort and be able to live in that.”

Was that something you were consciously seeking before you found it?

“I think I had some abandonment issues from my parents splitting up, or feeling I never fit in, and I’d gotten accustomed to being on my own. And largely due to my own, I think, inability to really be intimate with people, or share or be open or know how to be a friend or a partner to somebody… Trying that out and doing it with pure and full immersion has led to an unexpectedly great outcome.”

-----------------------

The other film project Reznor and Ross were on deadline for was Scott Derrickson’s The Gorge, a science-fiction thriller starring Miles Teller and Anya Taylor-Joy. They were working on a lengthy, music-dependent scene that they’d already mostly scored. But, Ross said, “the director wants it to be a bit more, I can’t think of a better word than just a bit more scary and intense.” They weren’t sure what that directive meant, exactly, but they were content – they were happy – to try to figure it out: to enter the room once again, carrying nothing, and to try to leave it with something that didn’t exist before.

Ross called up the scene on a monitor at the centre of a long mixing board: Teller and Taylor-Joy in an evil-looking spiky forest. Reznor and Ross have somewhat fluid roles in their collaboration, but today the plan was for Reznor to improvise some music while Ross edited and manipulated it in real time. “Atticus’ superpower,” Reznor said, “is that I can come up with a melody and a chord change, and he can make that sit on the scene in a way that is meticulous, and mind-numbingly boring to watch him do.”

A studio assistant, also in all black, presented himself to help Reznor set up a microphone and a cello next to a keyboard that sat underneath another computer monitor. Ross hit play on the footage and what they’d already completed of the score, a kind of haunted, chanting murmur. “It’s basically atmosphere at the moment,” Ross said. Next to him was a synthesizer whose make and model he asked me not to print and which the two men use as a kind of sound ecosystem to feed stuff into.

Reznor began by pushing down on the piano’s keyboard, while with his other hand he manipulated the sound with a flat synthesizer on the desk in front of him. It began as a kind of mellow pan flute thing, and then, with a push of a few buttons, became more of a sad, Social Network-ish plonk. Ross stood up and started tapping the synthesizer to his left, and the sounds Reznor made began to loop and accumulate – little melodic figures that plunged in and out of feedback. Reznor moved from the piano to the microphone, where he sang a few soft passages in a baritone falsetto, more sad than spooky, and then to the cello, which he played slowly and choppily. Ross moved between the computer and the synthesizer, trying to harness it all as it built to a loud, echoing crescendo.

After about 20 minutes, Reznor sat back in his chair, and Ross soon followed suit. Everything got quiet again. “It’s going fishing,” Reznor said to me, shrugging. “Sometimes something happens.”

-----------------------

Or, sometimes, everything happens. One of the first things you see when you arrive at Reznor’s home studio are two original paintings by the Yorkshire artist Russell Mills – on the left, a razor against a rusty red background; on the right, a decaying yellow-and-black collage – that ultimately became the insert and the cover art for Nine Inch Nails’ The Downward Spiral. This is the record with “Hurt” and “Closer” on it. It’s an album Reznor nearly didn’t survive.

Why do I bring this up? Well. If I may, for a moment, sound like the ageing dude in a black T-shirt leaning against the back wall of a bar where you’re just trying to be young and free of recitations of what the year 1994 felt like, there was a different quality to the way things would happen in music. Bands would labour for years, unknown, and then just get struck by lightning, is the best way I can put it: one day, you’re just a guy, and then one radio station plays your song, and then every radio station plays your song, and everyone is listening to those radio stations, because there is nothing else to do, and then MTV loops your video, and everyone watches it because, again, there is nothing else to do, and all of a sudden you are known by millions of bored people in a way that doesn’t quite happen now. This is a gross oversimplification, of course, but here Reznor is, one of the very few people who have experienced the thing I’m describing. I thought: let’s just ask him what that was like.

Reznor said, OK, he could tell me exactly what it felt like. He gave me a single moment: Woodstock ’94, which Nine Inch Nails almost didn’t play – “it seemed like it was going to be gross, to be honest with you” – but ultimately did. “And when we got there, it was terrifying,” Reznor said. “It was way bigger than I pictured in my head and walking on stage. But this is the point of the story: I knew. You could feel like you were in the right place at the right time.”

In retrospect, how did you handle success?

“Had a drink. That’s what sent me down the path. I wasn’t the guy that, you know, at 12 years old cracked a beer. That wasn’t it at all. Just, I feel anxious around people. I’m not sure how to act, especially now that you’re someone that’s supposed to act a certain way. There’s a projection. It feels uncomfortable to walk down the street and people are looking at you because they recognise you. That’s weird. Suddenly everybody wants to be your friend and you’re the coolest. Everyone wants to date you and shit like that.” Reznor said he found it was “easier to have a beer before I go in that room, and then a couple of beers before I go in that room. And pretty soon over a period of time, wait a minute, things start to get out of control. And you know how the story goes.”

Here’s how the story went: Reznor began to wonder if Trent Reznor could ever live up to the Nine Inch Nails guy that people had in their heads. “The reason I was having to drink was to fix that problem, my own insecurity. But the net result is: I’m not really who I am because now I’ve got drugs or alcohol in my system and I’m not thinking as who I really am. And that comes into focus once one gets sober and has time to reflect and kind of think about what got you there and shit you did.”

Eventually, Reznor got sober, and built himself back up. Today he’s happy to talk about all of it, obviously, but he and Ross have done a lot together since – 10 albums’ worth of Nine Inch Nails (Ross was an official member of the band for five of them), among other things – and Reznor is, by nature, not one to dwell too much on the past of a band that he’s still very much trying to figure out. “We’re not fans of resting on our laurels. We’ve been afraid of thinking about nostalgia. That’s a whole other conversation, but the reality is we’re getting older and our fans are getting older and that’s a fact. And I think, say, during the pandemic, not that you asked this question, but as I’m sure everybody was, I was pretty genuinely freaked out and very clearly came into focus: I’ve got to protect my family.”

He was consumed by fear, by terror of what might happen, of what he might do about it. “I can’t even fit all my kids in a car,” Reznor said. “But in the midst of that anxiety, sitting alone in here, I found comfort in nostalgia. I found comfort looking back at things from my youth that I’ve been afraid to even allow myself to glimpse at because it meant artistic death. Because one has to look forward. One can’t be self-referential. I was so afraid growing up in a little shitty town. I could see people that thought the highlight of their life is junior in high school catching the football. You know what I mean? That’s it. That was the peak. I don’t want to fucking be that person. I could see my fate if I stayed in that town.”

In those moments sitting by yourself, what were you getting nostalgic for?

“I miss parts of living in Pennsylvania. I miss a simpler life that I grew up with. I really loved the first INXS album in 1983. I was a senior in high school, and when I listen to it now I could almost start crying because it fucking reminds me of driving in a shitty fucking car in the summer in Pennsylvania. You know what I mean? Man. I allowed myself to kind of immerse myself in who I was at that time, and what it felt like.”

Reznor had been trying to remake himself ever since he left where he grew up, and now here he is in Los Angeles, over 40 years later. “And I kind of went on a deep dive for a while and allowed myself to realise: I am who I am. And the things that made me weren’t the cool things. I’d always been ashamed of: I came from a shitty town; I didn’t have an exotic upbringing; shitty education, you know what I mean? That’s who I am. I’m not sure what the point of all that confession was.”

Well, except: “It plays into where I’m at now.”

-----------------------

The last time I saw Reznor and Ross, it was once again in their studio. They were sitting very still. Had they been working before I got there?

“We were for a little bit,” Ross said. “And then nervously thinking about you arriving.”

Really? It’s OK if that’s the truth.

“That’s the truth,” Reznor said. They’d just been in this room for the past weeks, months – years, really, he said. Head down. Working. He gestured at me. “It’s a different mindset.”

And “I was thinking about something you said the other day,” Reznor said. That was on a Friday. I’d asked a somewhat rude question about their soundtrack work, which was: why would Reznor or Ross work for anyone else when they didn’t have to?

Now it was Monday. “I thought about that over the weekend,” Reznor said. “It’s like, Why are we doing this? The idea comes from what we think is a good place of ‘Let’s break it up. Let’s get sent down the rabbit hole on certain things and feel like we’ve got tasks being assigned to us rather than us just blindly seeing what happens creatively.’ ”

But, he said, “I think coming out of a stretch of a number of films in a row, I want some time of seeing where the wind blows versus: there’s a looming date on a calendar coming up and we’d better get our shit together. And certainly in the last few weeks I’ve been itching to do what we often do, which is just come in and let’s start something that we’re not even sure what it’s for.”

Some of that energy, he and Ross said, would probably become the next Nine Inch Nails album. Doing soundtrack work, Reznor said, had “managed to make Nine Inch Nails feel way more exciting than it had been in the past few years. I’d kind of let it atrophy a bit in my mind for a variety of reasons.”

But now, “I do feel excited about starting on the next record,” Ross said. “I think we’re in a place now where we kind of have an idea.”

And then there was the company, which Reznor and Ross spent the last two years putting together, piece by piece, with the help of John Crawford, their longtime art director, and the producer Jonathan Pavesi. The idea was, what could they do that they hadn’t already done around storytelling? Some of that might take the form of examining Nine Inch Nails from yet another angle – “we’ve been working on homegrown IP around Nine Inch Nails, stories we could tell, and we’re working on developing those in a way that are not what you think they’d be.” (As in: not a biopic.) They also have a show in development with Christopher Storer, the creator of The Bear, they said, and a film with the veteran horror director Mike Flanagan.

Reznor put on a pair of black-rimmed glasses so that he could examine a piece of paper next to him. “We just wrote some notes because I knew I’d forget what the fuck I’m about to say.” There was a short film coming with the artist Susanne Deeken. There was a clothing venture, a T-shirt line made in collaboration with a notable designer whose name they’d like to keep secret for now, which will arrive this summer. There was a music festival that they were currently planning, “where we’re going to debut as performing as composers along with a roster of other interesting people,” and a record label, both scheduled to launch around the same time.

And for two years they’ve been working with Epic Games on something that is not exactly a video game, in the UEFN ecosystem Epic has built around Fortnite – “It’s what Zuckerberg was trying to bullshit us into calling the metaverse,” Reznor said. “You can’t say that word any more, but in terms of the tool kit, thinking about it through the lens of what could be possible for artists and experiences, we thought that would be an interesting way to tell a story through that.”

They were nervously contemplating the prospect of having day jobs again, of being responsible for more than just themselves. Early on, as they contemplated launching the company, they’d sat down with David Fincher to ask him about movie production: how does it work? “And he’s like, oh, you’re fucked,” Reznor said. “I can distil a two-hour conversation into that. Because, he said, ‘I know you guys, and no one’s going to care more than you do, and you will not be able to let it go.’”

Reznor has actually had this experience before, of being sucked into a project bigger than Nine Inch Nails and having it take over his entire life. Years ago he worked as an executive, first for Beats and then for Apple, building a streaming-music service.

“Trent was very clear when we started,” Ross said. “We cannot let this get into Apple terrain.”

Reznor laughed. “What I mean by that is – I will make this brief; I’m trying to think through what I’m about to talk shit on. Just to self-censor for a second.”

Reznor paused for a moment and then explained. For years, he said, he’d wondered: what would make a good streaming service? This was before the advent of Spotify in the US or Apple Music. Jimmy Iovine, Reznor’s old label boss – later, Iovine would also become Ross’s brother-in-law, after he married Ross’s sister, Liberty, in 2016 – was launching a music service at Beats, which was then acquired by Apple, and Iovine said to Reznor: come try to make this thing a reality. And Reznor surprised himself by saying yes.

“It was a unique opportunity to work at the biggest company in the world at a high level,” Reznor said. “And it was interesting, the scale of the people that you reach through those platforms, just the global amount of influence those platforms can have was exciting. The political situation I was dropped into was not as exciting.”

Reznor enjoyed working with Apple’s design team and its engineering team. “But it made me realise how much I want to be an artist first and foremost.” Reznor also became discouraged with the possibility of fixing the problem that he was trying to solve. “I think the terrible payout of streaming services has mortally wounded a whole tier of artists that make being an artist unsustainable. And it’s great if you’re Drake, and it’s not great if you’re Grizzly Bear. And the reality is: take a look around. We’ve had enough time for the whole ‘All the boats rise’ argument to see they don’t all rise. Those boats rise. These boats don’t. They can’t make money in any means. And I think that’s bad for art. And I thought maybe at Apple there could be influence to pay in a more fair or significant way, because a lot of these services are just a rounding error compared to what comes in elsewhere, unlike Spotify where their whole business is that. But that’s tied to a lot of other political things and label issues, and everyone’s trying to hold onto their little piece of the pie and it is what it is. I also realise, I think that people just want to turn the faucet on and have music come in. They’re not really concerned about all the romantic shit I thought mattered.”

Anyway, Reznor said, turning to Ross, “That was a long-winded way of saying, when we talked about this company, I just said, ‘Be aware of what success might look like because it will turn into something that eats up lots of cycles and time and attention and energy.’ ”

But, Ross said, taking on new responsibilities was, paradoxically, also a way to stay a little younger. “I know we’ve all been talking about being dads and being adults and all that,” Ross said, “and there is a part of me that thinks: it’s important to keep the kid alive.” Meaning the child inside yourself, rather than the one you’re responsible for.

He told a story about him and Reznor visiting the director David Lynch at his house to work with him on the 2017 revival of Twin Peaks. “And I don’t know how old he was at the time,” Ross said, “but he was older. But just walking in there, and he had the room set up and there’s a screen there, there’s some chairs here and there’s some musical instruments there and he’s smoking a cigarette. There’s nothing old about that dude. You know what I mean?”

Lynch showed them some Lynchian footage. It was incredible, even if they didn’t quite know what they were looking at. Lynch was probably 70 or 71 at the time. “But it’s that thing of it doesn’t matter how old he is,” Ross said. “He is alive. It’s that bit of it all that one doesn’t want to lose with age.”

The point was, Reznor said: “Let’s try some stuff. We’re bored. We are. You know what I mean? We’re grateful. We enjoy doing films. We can write a better Nine Inch Nails record, I think. We can put on a cooler tour. We are aimed to do that. But man, what if we try to do that?” Meaning, the company. “What if we could take what we’re good at, like we did with film? We identified something I think we’re good at and we figured out how to apply it to something else. What if we take that theory and try it on some other things? And that’s led us into: we’re not beaten down completely yet. And it feels exciting. That’s what matters to us right now.”

-----------------------

Styled by Mobolaji Dawodu Grooming by Johnny Stuntz using Dior Capture Totale Hyalushot SFX Makeup by Malina Stearns Grills by Alligator Jesus Tailoring by Yelena Travkina Set design by Lizzie Lang at 11th House Agency Produced by Emily O’Meara at JN Production

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our fates are sealed. But I think we have one move left.

We can try.

#the good place#tgp#tgpedit#thegoodplaceedit#nessa007#useraurore#sitcomedit#tvedit#*#myedit#the good place spoilers#I FINALLY FINISHED ITTTT#the gifs look so bad on my laptop idk why WAAAH I HOPE IT'S JUST MY LAPTOP AND NOT THE ACTUAL QUALITY.#bye i should've emphasized the ''try''/''trying'' parts in the quotes#OMG ANYAWY!!! I LOVE THIS SHOWWWW IT MEANS THE WORLD TO MEEEEEE AND THIS WHOLE#TRYING THING WAAAH#bye omg michael and eleanor are the only ones in this set. I WENT THROUGH THE TRANSCRIPTS FOR EACH EPISODE AND TYPED ''TRY'' AND THEYRE-#ALWAYS THE ONES WITH THESE QUOTES/MOMENTS T.T#A LITERAL DEMON AND A TRASH BAG FROM ARIZONA <3

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

et voila ! the full version of 'last stop' from nimona (aka the track that starts to play at "dyou think they saw us?" *dramatic pause* "yes".) full transcription, meaning it's as close to the original as i could make it

obvs not as well known as ballister's theme, but still. the piece is more of a psychological thriller than i realised so if you want to be scared, have a listen :D

(score at https://musescore.com/user/71371714/scores/12273496?share=copy_link :))

#nimona#nimona soundtrack#i literally only did this because i wanted that cool brass bit at the start before bal hides under the train window all silly <3#anyway#darcy daydreams#my transcription#music

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

English Closed Captions for Slimecicle Egg Adoption Day VOD

includes translations of spanish dialogue to the best of my ability. enjoy

(other vods i have captioned can be found in my pinned!)

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

from Picture-Play Magazine, October 1923

The Irrepressible One

Fans are always clamoring to see more of Mabel Normand, and in that they are quite like her many acquaintances.

By Norbert Lusk

Full Transcription Below

Photo caption: She is a little figure, all vivid expression, with enormous eyes and petulant, childlike mouth.

MISS NORMAND, one hand grasping a tube of tooth paste, the other holding with a bibliophile’s tenderness a volume of Ernest Dowson, romped into the room.

Tor two hours I had waited. My patience was that of a senescent courtier used to the etiquette of dying monarchies.

Not to interview her. Not as a stranger come to beg a photograph, or a year's tuition in a college of chiropractic, or even to beseech aid for a crippled kiddie’s operation.

These benefices would, my experience told me, have been all too easily won from Mabel. The prospect of such picayune gold digging would have found me not at all trepidant.

I had come on a far, far more delicate mission—one that held me rigidly apprehensive in the plush and prisms of the hotel drawing-room, though not too unstrung to inventory the jumble of Mabel’s belongings scattered, piled and flung here and there.

How like her they all were, I mused, but not too indulgently. Deciding, you understand, to be reserved and not let her know I'd paid attention to her gewgaws. They ranged from seven grotesque dolls, limply perched on mantel and chairs, to a capsized basket of faded flowers, and a leaning tower of cigarettes in boxes, with other oddments between.

For I was there as a once-devoted friend willing, but not too eager, to consummate a reconciliation, if I may use a toplofty phrase. and resolved to be dignified at all costs and not let old-time fondness be welded anew into fettered slavery.

It was to cancel an estrangement brought about by an unanswered letter, or, something equally heartbreaking that Mabel had done.

Frankly, I don't quite remember what it was, now, though before Miss Normand scampered down the hall my grievances were precisely defined, like the perforations on a music roll, and ready to be ground out, a complete opus, at concert pitch.

Mabel is like that—she makes her wounded victim forget his wrongs in a moment and buckle on the armor of a crusader to avenge her own. She is dreadfully devastating to dignity, to judicial balance, to one’s amour propre.

That neglected letter, or whatever it was, had made me sorry for myself and skeptical of the friendly vows of all queens of the screen. I had, indeed, renounced the false sisterhood and consigned them to celluloid. When, as recorded, Mabel bounced in.

Now for the Normand witchery, sorcery, or what not. If this story is to get anywhere at all, something that passes for explanation must be submitted. The hard part of it lies in translating it by means of the printed word, lacking, in turn, the wizardry, alchemy or what not of a Rossetti, a Thomas Hardy, or a James Joyce. Mabel is deserving, honestly, of an abler etcher than I.

“I love your coat—it looks like an Airedale!’ she cried outside, before I saw her, as a means of breaking the ice after three years.

“Ernest Dowson is my favorite poet. I love him. If he weren't dead I’d make him marry me.” Mabel whirled in delivering herself of this and introduced me to the bell boy, who stood behind her, laden with books.

“This is my darling old friend who knows all my faults but loves me just the same. He’s going to be Ritzy about this when you go, because he’s got himself up in soup and fish, trying to pass for an ambassador! But I don’t care, now that he’s forgiven me—do I, Bunker Bean?”

Whereupon she resorted to her own way of stifling a reply. It is the way of an impulsive, affectionate child and, I add, to give the world hope, is not reserved for me alone. One's resistance sags under these onslaughts and I couldn’t command myself to strike an attitude of chill dignity.

Picture, if you can, Mabel as she is off the screen and you'll not ask why. A little figure all vivid expression, quick movement and rapid speech. with enormous eyes and petulant, childlike mouth. She is wise as a serpent in the ways of the world, yet at times more naive than a fictional milkmaid. Beneath it all her manipulation of people is unfailing.

Clinging to the last vestige of self-assertiveness, I reminded her that I’d waited two hours.

“You would! So would the Rock of Gibraltar! That’s why you're wonderful. But I telephoned you twice from the bookshop. Don’t tell me that maid didn’t—I’m going to fire her!” she darted to the door, then wheeled and paused. “No; if you don't mind, I won’t. She’s a wonderful packer.” Mabel softly closed the door and lowered her voice as if in a den of thieves.

“I’m going abroad—no one must know but you. I've always told you my secrets, haven’t I? Sit here near me and I'll tell you some more. You're the only person in the world who can help me.” Followed chattering exposition other plans.

They included, so far as I could adduce, nothing sub rosa. She was going to London for Chistmas, would spend the holidays in Rome (I'd not be surprised if she collected a present from the Vatican Christmas tree, if there were one) and return in a few weeks. There were some trifles to be looked after in her absence.

It was happiness, as always, to undertake them. Mabel asks little and makes one feel a minister plenipotentiary in obtaining chewing gum for her.

Our rapprochement complete, she saw no reason for settling down to stilted conversation about the weather and topics of the day. Accordingly she ran in and out of the room, presumably to confer with those wonderful packers. or leaped to answer the telephone’s insistent jangle. It was always an invitation to join a party, and I caught names as celebrated as her own in these potential hosts. But Mabel refused all, declaring, in a torrent of endearments, that her physician had ordered quiet and rest.

“Isn't it outrageous?” she wailed, wide-eyed from her desk. “I have to autograph five hundred of these ‘Suzanna’ books before I can get away. It’s slavery; yet people think we don’t do anything more

Photo caption: She is wise as a serpent in the ways of the world, yet at times more naive than a fictional milkmaid

strenuous than change our shoe trees. I’ve got writer’s cramp, as it is, and housemaid’s knee too. Tell me what to write on the flyleaf for my French teacher. I've been studying three years and don’t know a thing, but he’s a darling old peach.”

She munched her pen. Already she was inked to the wrists. Needless to relate the ready star needed no prompting.

“Don't you dare like this book more than you do me!” she scribbled, “l’otre gamine terrible—Mabel.”

Gamine! That’s the word. Mabel herself described a phase of herself, her present phase.

Luxurious, lavish, independent of any individual's favor, she is a gamine de luxe—a sort of Kiki, minus Lenore Ulric, because, despite dissimilar circumstances, Mabel’s heart is that of the child-woman of André Picard’s play. Gaining her own ends by the sheer vigor of her attack, never accepting defeat. appraising people and situations to a nicety, and over all flooding an excess of capricious high spirits.

Mabel is inimitable, undeniable, irresistible. You may put this down, if you choose, as arrant bias on the part of her toiling historian. But confront him, if you can, with the person who has withstood Mabel. Vainly he has sought this Hippolytus among studio workers—people generally without illusion—and while there are feminine stars of the dramatic persuasion who wouldn't exactly expand while Mabel watched their emotional scenes in the making, it is because her sense of burlesque would conflict with their lack of it.

Yet. while she indulges her gamine mood, there still are other moods. When finally she permitted the packing to be carried on without interference and had inscribed fly leaves galore, autographed pictures, written notes, despatched telegrams, denied herself to callers, plied me with food, “Suzanna” souvenirs and instructions—and had driven home her points with some comic imitations of people we all know—she talked uninterruptedly. Probably as a means of warding off fatigue.

“WHY is it, do you suppose, I’m not happy? People think I am. I babble because they expect just that. But. cross my heart and hope to die, I'm not Pollyanna by a long shot. There's something missing. Sometimes I think it’s because I know people too well—see through them too easily—and it makes me want to hide myself away from it all. You know I really love to be alone where I can think things over but—you answer the telephone, darling—say that Miss Normand has gone over to Staten Island to see her mother.” Fortunately this fib swept the current of Mabel’s introspection into happier channels—happier, without doubt, for her visitor, who had the sudden qualms of one who might be keeping Mabel from thinking things over.

“You remember I always used to be writing things in my book? If you promise not to make fun of me, or take down anything, I'll read to you. I’m really self conscious about my poems. I couldn’t bear to have people laugh at a comedienne’s attempt to be serious.”

And so, twisted into gnomelike angles, on the sofa, Mabel unlocked her book and read. She won’t mind mention of this because, in keeping my word not to quote. I have only recounted a fact which her fans should know.

Her verses are simple, unaffected, concrete. Each mirrors an impression. There are clear images, unclouded by wasted words, in them all. The sincerity of her intention disarms the critic (if I may masquerade as one so late in the story), and stirs and touches. Which is precisely what Mabel wished to do when she essayed her first author’s reading under a rose lampshade.

“Why in the world don’t you publish these? You’d have no trouble arranging it, and think what a surprise people would get.’

“Not for any money—at least not now. They’d only be bought out of curiosity and some one surely would laugh. I couldn’t bear to be laughed at in that way. When one understands life, or tries to, thoughts that touch very deeply should be kept mostly to one’s self... Oh, but I'd love to do an autobiography, and tell the truth, mind you, the whole truth! That's all that would excuse it.”

I predict that she will, some day, for unless all symtoms fail, what Mabel aches for is literary expression.

Certainly few busy people read more than she does or respond more readily when there is opportunity to discuss books. Of the fifty or so volumes awaiting the clutches of the packers, there was nothing obvious; no garishly jacketed best seller, but poetry, biography, criticism, history, all out of the ordinary.

In reading, however, as in her conduct. it would seem milady has her moods. She avowed affection for Ethel M. Dell—at least for one of her stories which Mabel expects to do in pictures—yet holds Leonard Merrick, economist of emotion and narration, in esteem.

“No, no; not that. Don't begin with ‘Conrad in Quest of His Youth’—that’s not a fair test of Merrick’s power,” she advised a caller who wished to become acquainted with the novelist. “Start with ‘The Man Who Understood Women.’ The rest will take care of themselves.”

She dispensed this counsel with a quiet zest that gave me a flash of the pedagogue, if you'll credit that. In line with this she assured me she was a born old maid, and expected to die one, because she spends much time happily cataloguing and rearranging her belongings. Servants notwithstanding, Mabel says she knows exactly where to find the black-lace stockings that have been mended once, and woe betide the slave that mixes her handkerchiefs.

How, I asked myself, did the inflexible Britons receive this quaint, unconventional ex-Biograph girl? She had returned, not long since, from her first invasion of London and was now to go again, without having revisited Los Angeles. There must have been few lorgnons raised by the duchesses for Mabel to cartwheel into the midst of their unwedded young sons once more. So I asked her.

“In England people do the loveliest things for you for the love of doing them. You know what I mean? They don’t calculate their kindness. It’s an instinct, not a gesture, and it’s gracefully casual. Gosh! I adore the English for their civilization, their traditions.”

This enthusiastic blanketing she followed with details spotlighting the hospitality of lords and ladies in country houses and at hunt breakfasts. Of solitary

---

THROUGH FRIENDLY EYES

Now and then interviewers and acquaintances of Mabel Normand have written their impressions of her—many of them vivid, some of them appealing, all of them interesting. Normand is one of those rare individuals who never fails to make a deep impression on the people she meets. It is only from a person who has known her well for a number of years, however, that you can get an adequate word picture of this unusual girl. Therefore, PICTURE-PLAY is proud to present this story by Norbert Lusk—first of all because he is a clever, facile writer—but particularly because he has long known and admired her.

---

walks over moors, gathering heather—and, with no less happiness, of a police inspector who had won her heart by escorting her through Limehouse.

“You knew dear George Loane Tucker, didn’t you? Well, Sir Hall Caine wrote me a darling note—no; sweet was the word for it (I mean quaint), telling me that Mr. Tucker, when he was alive, used to write him nice things about me and asking if he could come to see me. He came and turned out to be the gentlest, darlingest pet there ever was. We understood each other—zip! like that! and later I went to his house for tea.

“I liked Barrie too, Wasn't it a shame? I mean I was bathing when he called at the Ritz and kept him waiting too long” (oh, Mabel, how like you!) “for when I came out he had gone, leaving a funny little note. It said that he had fixed the fire in the grate and hoped it would warm me. Of course I tried to make up for this later. Shaw was awfully kind too—very quizzical and clever."

She had, however, no tale of him to equal the other conquests, which gave me an opening to ask if it were true she had broken an engagement to meet Princess Mary.

“Of course not! My friends ought to know me well enough to be sure I wouldn't do that. It was to have been at a charity bazaar or something. At the last moment the thing was called off. Some bigwig engineering it was sick. Then some one thought it would be funny to say Mabel Normand had been rude. That’s how things start. Just because I’m a little—well, you know, different—people believe anything weird about me.

“I wish to heaven some philanthropist would take the time to write about me as I am. Something quite simple, natural. Not making me out a highbrow, or a stately Vere de Vere, or as a girl with no taste at all. Just as I really am—just me. Then the public wouldn't swallow nonsense when it’s printed by those who don't care because they don't know any better. . . It must be great to be a wharf rat.”

Mabel next returned from Europe in high spirits on a slow steamer, under the impress that she had booked passage on an express.

Reporters, boarding the vessel at quarantine, still surrounded her at the pier because, I surmised, she was offering entertainment—or news.

Next morning’s papers rumored her supposed marriage to an anonymous Londoner. Mabel was in tearful indignation over this wrong and, as always, spurred her sympathizers to avenge the canard. But first I probed for clews.

“I never said a thing,” she averred. “A lady on the steamer was reading my palms, saw this diamond guard and kidded me about having married secretly. I kidded her back. Who wouldn't have? Then it spread. Things always spread. I'm going to take the veil.”

She was reminded of what she previously complained of in newspaper misrepresentation and advised that she should have flatly contradicted the sociable palmist.

“Oh, you want me to be dignified. Dignity my eye! I can’t be upstage and I can't be mean when people are nice. But I’ll never even be civil to a newspaper man again.”

On the morrow this sprightly queen of contradiction was hostess to a group of news gatherers, purposely to convince them of the error of their ways. How she did it you perhaps know by now. At any rate the next edition of their journals gave space to Mabel's denial.

This, then, is the Mabel Normand adjudged the leading feminine comedian of the films. These glimpses of her away from the studios, chosen because they are typical rather than exceptional, reflect. I hope, the vigor and verve and whimsicality of her acting. It is doubtful, however, if they give an idea of her professional authority. sagacity. When she is absorbed in work it is absorption indeed. Her long experience—her facile inventiveness — fundamental sense of the comic—are all whipped into dynamic activity when she attacks a picture. Should the result disappoint, Mabel’s reaction is that of utter heartbreak. But she rebounds. Like all urgent souls she never accepts defeat.

“She seems to be working out as one of those very human characters,” she wrote of ‘The Extra Girl.’ “You know what I mean—a girl one looks at and wants to know more about as she passes by, and leaves one with a little ache that one may know her better. She has given me tremendous ambition. If others have failed perhaps it was misjudgment of one kind or another in attempting them. But this picture has had the same effect as. the faith of those who really love me. And so, from the way things look, I think those who care for me will be rather proud of their—Mabel.”

#1920s#1923#mabel normand#picture play#film magazine#fan magazine#classic hollywood#old hollywood#classic movies#silent comedy#silent era#silent cinema#silent film#classic cinema#classic film#classic film stars#my transcription

1 note

·

View note

Text

Transcription:

[Tweet from Karen K. Ho, @/karenkho]: if you do not stretch, (back, legs, hips, feet) and you know what the Animaniacs are, you need to start doing it for at least 30 minutes daily or your body will suffer

[posted 4:24 PM 2023-06-19 78.3K views, 289 retweets, 33 quotes, 1681 likes, 66 bookmarks]

#CACKLING#also don't forget neck and shoulders!#I really need to get back into the habit of doing this#tumblr's aging userbase#transcribed#my transcription

96K notes

·

View notes

Text

Closed Captions for "Quackity vs. ElQuackity" / Subtítulos descriptivos para "Quackity vs. ElQuackity" / Legenda oculta para "Quackity vs. ElQuackity"

youtube

English closed captions here

Subtítulos descriptivos en español aquí

Legenda oculta em português aqui

you can find other streams I've captioned in my pinned!

portuguese translation by the amazing and talented @al-pomegranate-seeds

english and spanish by moi

#the book is at 13:36#and the confrontation is at 23:30#qsmp quackity#qsmp elquackity#qsmp#my translation#my transcription

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

#his ass just wants to be included#this image projected itself into my head when i read the transcript#tmagp#tmagp 31#tmagp spoilers#tmp podcast#tmp spoilers#the magnus protocol#tmagp season 2#alice dyer#gwendolyn bouchard#i can't believe freddie doesn't have a tag#oh well#i tried

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

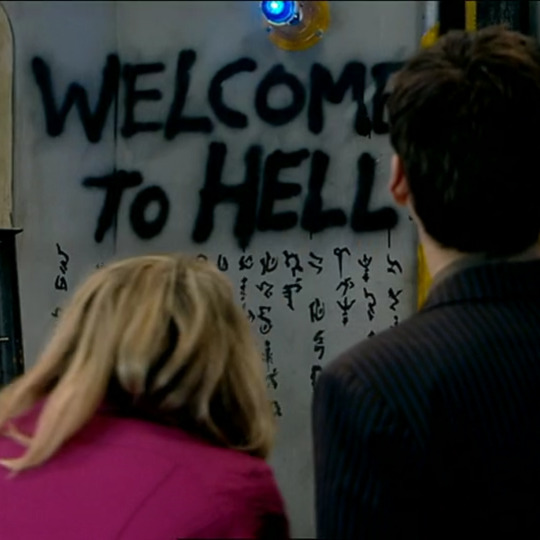

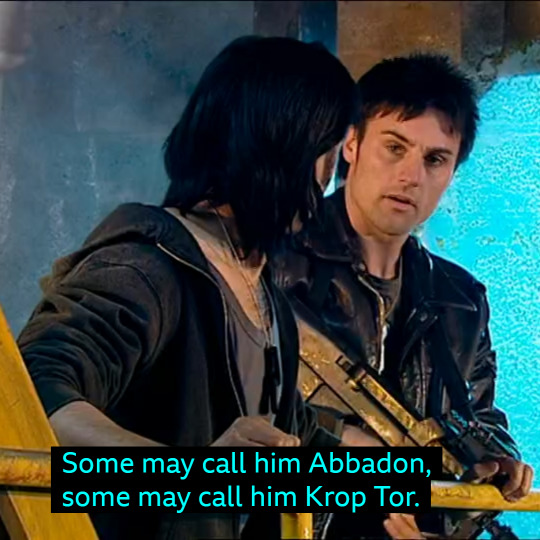

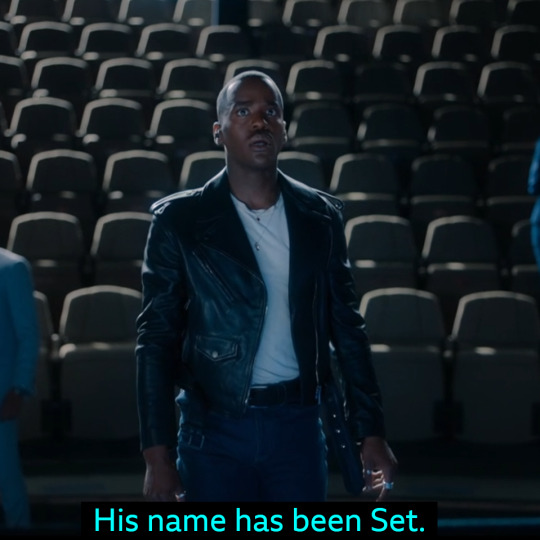

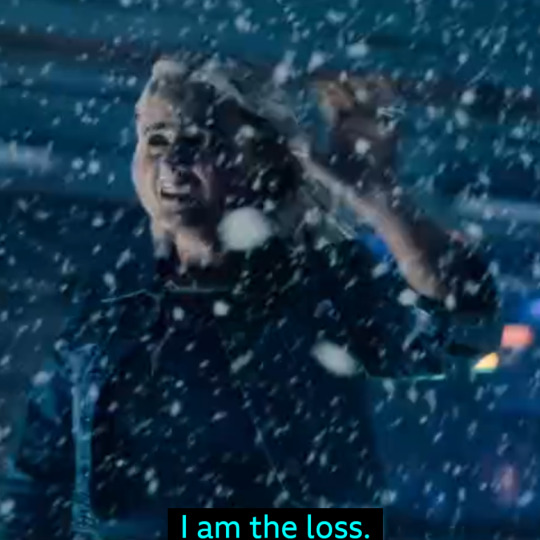

Doctor Who: The Impossible Planet & The Satan Pit / The Legend of Ruby Sunday

#doctor who#doctor who spoilers#the legend of ruby sunday#sutekh#the beast#the impossible planet#the satan pit#mine#dw#dwe15#dwmine#dws2#parallels#following on from my last post I suddenly realised a lot of things#there may be more but I was going off memory and transcripts rather than fully rewatching them#also I'm annoyed the text doesn't line up#the aspect ratio of 2006 dw is different to 2024 dw#so the 2024 ones are at the bottom of the image (under which is a black bar)#and the 2006 ones are partway up the image#anyway it might not be the same character (though what if it was?) but the execution is extremely similar either way#rewatching the cliffhanger of tip I realised just how similar the whole possessing people and making them chant 'I am the x' stuff was

4K notes

·

View notes