#most cultures - but specifically Western Europe - had an oral tradition

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

As we’ve moved father into the post-modern era (about 1970 onwards), which is defined by the increased social emphasis on individualism, communal storytelling has become something… shunned. Past methods of communal storytelling (theatre, music, folktales) have been increasingly privatized since 1970. Because of this, we’ve seen the emergence of fanfiction (specifically slash fiction started by Star Trek fans in the 1970s) and TTRPGs (specifically Dungeons and Dragons and Pathfinder in the late 20th Century), which are both ostracized by the mainstream culture, but are also the only two sources of communal storytelling in the 21st century. TTRPGs are finding more footing in mainstream culture, but because they’ve found footing are becoming increasingly commodified. In this essay, I

#I’d be interested in studying how communal storytelling has changed over the past hundred years.#a cultural history of communal storytelling#in the pre modern era (pretty much all of time up to the Industrial Revolution [1780]) all storytelling was communal#most cultures - but specifically Western Europe - had an oral tradition#religion and mythology were the basis of society#storytelling was engrained into the culture#then in the modern era (Industrial Revolution until the 1970s) communal storytelling is still prevelant but it’s become organized#going to the theatre was a Big Thing#same with going to the cinema once film was invented#music was performed in front of large audiences#as the oral tradition gives way to a literary one fewer people are able to Become Storytellers#but they’re also able to share their work with more people#then you get to the post modern era and that all goes away#theatre and concerts are a privilege that few can afford#music and movies are easily available via streaming but that makes them individual experiences#books are prominent and oral storytelling is nearly nonexistent#even audio books are an individual thing#but then comes fanfiction and TTRPGs#which are underground and often scorned by the mainstream to an excessive degree#which is just#fascinating#wit rambles

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The migration of folktales, fables, myths, and The Doors of Midnight. I've talked about his following piece of work before - Panchatantra

Pronounced (cuz romanizing Sanskrit adds weird ass fake A's to things) Panch (or pah-nch, meaning FIVE) Tantr (thun-trr) Treatises.

It is a collection of folk tales (and I talked about this in my true origin of "fairy tales" and even what inspired the Grimm Brothers thread) fables, particularly focusing on talking animal fables from India. The written text is about 200 BCE (before common era) but the stories themselves are agreed upon by folklorists and experts to be far older given Sanskrit's long oral traditional history and the fact India has a history of oral performers by caste passing down these tales these tales are as old as we can possibly imagine. It is arguably one of, if not the most, translated piece of work out of India, with copies of it having reached Europe by the 11th century CE - yes, that old. Old enough to influence many European stories - particularly folk/fairy tales, and we'll get into that, because believe it or not, some famous fabulist writers even credited the collection of tales/author as their direct inspiration. Wild, right?

Continuing.

Panchatantra has been translated in nearly every major language with nearly 200 versions in 50 languages over the world. Before even the 1600s it had been translated into: Czech, Old Slavonic, Spanish, Italian, German, English, Greek, Latin, and more.

The earliest known translation was 550 CE into Middle Persian (and we'll get into why this is important in Tales of Tremaine as it's a commentary/meta referential and analysis, and love letter about migration of stories as well as storytelling) -- by the 12th century it was really spreading through Europe based off the Hebrew translation by Rabbi Joel, which then went on to be translated in German by Anton von Pforr in 1480 -- nearly 40 years before the 1812 publication of The Grimm brothers tales. Yep.

Now, to 1001 Nights - a collection of tales compiled by Alf Laylah wa-Laylah, which yes, includes stories from India that were translated as discussed above, and Syria and other parts of the Middle East as well obviously.

Panchatantra has been influential in both 1001 Nights as well in Sinbad. The particular inspirations were the usage of frame narrative, first recorded in India, and also the inclusion of specific styles of talking animal fables within the collection, and most specifically the motif of the wise young woman who delays and finally removes an impending danger by telling stories - if you've read The Doors of Midnight, you'll get now where I'm going with this.

Since the series is a mix of many things, including addressing/commentary on fantasy/myth-storytelling tropes, motifs, themes, history, origins, replying/referencing them in meta ways, as well as a discussion about western fantasy novels because there's a history in/with them also using tropes for exoticization and kind of fetishy exoticization at times without nodding to, offering, showcasing a lens to/of the cultures those techniques, stories, tropes come from, I wanted ot be able to talk about that in the context of the work (which does happen), critique, reference all of it. Book two is no different.

In where if you've read it, you'll see a genderbent take on the particular motif above, and if you're only understanding of stories is 1001 Nights, you might get it confused for ONLY referencing one story. Not true. While there are many overt and subtle references to that because this is a love letter and commentary on the migration of stories (which that is literally mentioned in the story itself), so it tries to include and nod to all the wonderful stories from all the cultures I can include along the Golden Road in this world.

The take in here not only references both Indian and Middle Eastern culture, but also dismantles and in fact comments on a toxic trope that has had previous positive iterations as well - namely: meeting the goddess/the temptress (two pieces of storytelling that often get lumped into one of a dude character bumps into smoking hot goddess who can't resist him, they boink (A LOT a lot a lot) he leaves or threatens to and she's upset, boink continues, then he gets a gift from her. This goes backs to the oldest epics, it's not western or even fairytale original, but it did become UBER popular in the west. Young bardic boy meets fae, they boink a lot. He leaves. Usually tragedy, not always. The end. Some magical gifts.

But the idea behind the trope was never supposed to be this reductionist. It was supposed to (go back to this word I've used about) evoke SENSE OF WONDER. Meeting a powerful character in possession of knowledge (see power), and magic (also power but sense of wonder), and to learn from her, gain some wisdom for your own betterment and evolving into a better kind of hero, and then use your gifts she gives you to that end. See, Frodo meeting Galadriel, no hanky panky, much wisdom, both were offered different temptations (not of the body) and in the end helpful gifts for the quest. :)

So, if you like or want to learn more about comparative mythology, storytelling, seeing the origins of such and dismantling your ideas of: structures, plot, tropes, motifs, beats, so on - check out The First Binding and The Doors of Midnight (recently released by @torbooks and @gollancz (US/UK).

Anyways yeah.

Back to more about this. I've shared before the assertions of Max Muller and others on the influence that 30-50 percent of western fairy tales/ballads/nursery rhymes owe their origins/inspiration to Indian tales -- but Jean de La Fontaine, a french fabulist and poet - one of the most read poet of that time, directly credits Indian stories and the Indian sage Pilpay for his source of inspiration in his works --

"This is a second book of fables that I present to the public... I have to acknowledge that the greatest part is inspired from Pilpay, an Indian Sage" - Jean de La Fontaine.

He's also not the only post medieval era author to specifically credit Indian stories and the sage Pilpay and others who contributed to the many other epics, collection of tales, individual tales, and more.

Now, IMPORTANT NOTE - inspiration here does not mean a direct 1-1.

Yes, many are complete rewrites, translations which is obvy a translations, and others are using the motif and overall theme but converted to and through their cultural lens and time of place. That's how storytelling traveleled, evolved, and become coopted, adopted, and accessible to local masses in w.e. country/empire.

And that's obviously a massive theme in my work but using a central heroic figure or villainous to be a focal point for that to see how that happens around one figure as it's an easier way to do that in fiction rather than a freak ton of povs which would make it harder for readers to continue to track and grok all those changes within the frame narrative aspect.

#folk tales#folklore#storytelling#fairy tales#mythology#The Doors of Midnight#Panchatantra#Grimm Brothers#talking animal fables#1001 Nights#Alf Laylah wa-Laylah#Middle East#Syria#SENSE OF WONDER#fables#Frodo#Lord of the Rings#LotR#Jean de La Fontaine#medieval era#inspiration#translations#inspired by#writing thread#i should be writing#writers on tumblr#myths and legends#writers and writing#fantasy books#creative writing

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

I went down a rabbit hole on penis subincision, which lead to an edu article on sexual behavior in indigenous Hawaiian populations. (By Milton Diamond if you feel an urge to google). The article talked about how it was normal and even encouraged in a lot of these cultures for young people to engage in homosexual acts for the purpose exploring each other and simply having fun. This, in turn, reminded me of an assertion that Mark Thompson made in his book, Gay Spirit: Myth and Meaning...

--

....I’m not sure if you’ve read Thompson’s work but you posted passages from his book a while back. He compares the rejection a fixed gender identity and the phenomenon of "changing" to the archetypal definition of being a shaman, which is kind of fine. But then he goes on to claim that Diné (Navajo) people had a cross-dressing shamanic priesthood of gay people (the nadle) until white colonialism destroyed the tradition. Which, frankly, was a claim that I initially dismissed as...

…a gay white dude making things up until this whole subincision thing made me go look into it more closely. There are in fact many detailed articles on this. (They’re called Nádleehi, not nadle in these papers). So what I want to ask is if anyone knows exactly how common it was for LGBT+ to be accepted in non-colonial populations. Because I was under the impression that the consistent natural reaction to queerness in almost every human culture is to eradicate it.

Nonnie... WHUT?

YES, oh my god, a ton of cultures were okay with some form of something we would today see as queer.

YES, colonialism routinely wiped this out or at least tried to, and many of the places doing the colonizing also stamped out their own ancient traditions.

I don't recall that particular book or quoting it, but I post a lot.

It's not as clear-cut as total acceptance or acceptance of all forms of queerness. A common format is some kind of third gender role for nonconforming or trans or intersex people, often a combination of what we'd see today in the West as femme gay men and heterosexual trans women. Sometimes, this third gender had a specific social role, like shaman or entertainer. The modern split between gender identity and sexual orientation is not really how people saw it in a lot of past cultures (or, hell, in plenty of modern ones outside of the mainstream Western world).

When I was 14, I was fucking obsessed with this academic book of compiled journal articles called Third Sex, Third Gender: Beyond Sexual Dimorphism in Culture and History.

In terms of binary m/m interactions... uh... Ancient Greece is right there. Did you... miss that?

Historically, Japan was all about it being manly to fuck dudes because they didn't have girl cooties until the Meiji Restoration. Similarly to Ancient Greece, it was unmanly to take it up the ass as a grown man, but that's different from m/m sex in general being a problem. As with many societies outside of the mainstream West post... like... mid 19thC, m/m sex was seen as something you did, not something you were.

Medieval Europe would have kicked your ass for "sodomy", including oral with your spouse, which also falls under that term in that period, but they still wouldn't have thought a man was "gay" for fucking men. They'd have thought he was falling prey to a common sin that any man could potentially be tempted into. Sexual orientation is pretty much not a thing until after we get psychology as a science.

China got more homophobic over the dynasties. There was a time that the emperor's boyfriends were in the fucking history books along with his baby mamas. That's where we get the term "cut sleeve" from.

We don't tend to know what f/f stuff was going on in most times and places because most of the written record is men writing about their dicks.

Modern Thailand has all kinds of interesting things going on, and that whole region of SE Asia has had at points, though the more colonialism, the more local shit got suppressed. I can't speak to the total accuracy, but here's a wikipedia article on gender identities in Thailand.

Tibetan monasteries had abbots openly promoting their boyfriends. As long as you were doing it between the thighs and not touching icky girls, it was fine.

American Indian cultures are well known to have had fucktons of priesthoods/shamans of that type. It wasn't every group. Some were more prone to punishing gender nonconformity. AFAIK, a specific variant role for AMABs is more common than just letting people do whatever. In some, you could become a shaman, but they also tended to scapegoat the shamans in times of crisis. I'm no expert. I'd look up what modern two-spirit people have to say about their cultural traditions along with journal articles. The historical record is fragmentary and full of missionaries' unhelpful opinions.

Humans do often punish difference, but tons of cultures didn't see m/m sex or some specific form of third gender as anomalous. A ton probably didn't care about f/f sex, though it's harder to tell.

Gender conformity is often enforced... but why on earth would you assume most cultures only have 2 and that they map exactly onto our modern ideas of gender?

Seriously, nonnie, where have you been?

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

“An examination of the economic abilities associated with women in the German, Lowland, and Italian regions of medieval Western Europe reveal that women had the capacity to obtain sizable amounts of land through marriage customs and inheritance laws, and could partake in the public economic realm through the production of textiles and the selling of goods. A medieval women’s influence extends even beyond the realm of economic power, however. A study of the politics of these three regions during the Middle Ages demonstrates that the political position of women was often influential.

The same German society that allowed women to partake in textile production and to acquire wealth and property through inheritance laws also recognized women as citizens. Citizenship in such cities as Lille, Bruges, Frankfurt, and Leiden during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries involved a process of registration; according to the records of Bruges, Leiden, and Frankfurt specifically, independent women were often registered “because in these cities citizenship was easily acquired and was obligatory for almost all workers.”

As “co-managers and co-owners of the household and its property...[women] were inevitably full members of citizenries with households as their constituent units.” German urban women, through their citizenship, fulfilled the “the objective qualifications for governmental positions,” although paradoxically, they were still barred from obtaining such positions by the male-dominated politics of most cities.

The German poem of Ruodlieb again provides an important insight into the actual traditions that governed a woman’s place of power in noble family life. During one of its episodes, Ruodlieb is hosting a banquet at his home, and his mother is in attendance. Ruodlieb “commanded one higher chair to be placed for his mother, so that she in this way she could be seen to be mistress.”

The poem goes on to mention that “by giving honor to his mother in this way, and holding her as his liege-lady, he earned praise not only from the people, but from the almighty a crown and everlasting life in heaven.”Ruodlieb, a noble, allowed his mother to occupy a position of power at the table, and further, such an allowance endeared Ruodlieb not only to his subjects, but also to the higher power.

In the Low Countries, women were afforded a political role as participants in public political acts. Ellen E. Kittell, in her extensive article “Women, Audience, and Public Acts in Medieval Flanders,” describes the integral roles that women employed regarding the link between public performances and law-making in fourteenth century Flemish society. Flanders was unique in that it was little affected by Roman law and rather maintained “a fundamentally Germanic system of law and custom that was based more on public negotiation among groups than on the arbitrary decisions of constituted authorities.”

As Flanders’ thriving commercial and industrial economy grew around the eleventh century, Flemish communes began to utilize citizen participation by allowing a broad cross-section of their population, a cross-section that included the women of the city, to participate in political affairs. Women thus had “routine appearances in public as chief and effective agents in the variety of oral-aural transactions...were countesses and castellans... [and part of] the legal and commercial lives of most cities”.

These public audience law systems in turn allowed women to gain influential positions of power, such as Countess Jeanne in 1206 and Countess Margaret in 1280 acquiring the role of ruling over a county. Even single women were systematically afforded similar rights to perform actions in these public hearings as their married counterparts; their independent status did not disenfranchise them from participating in the existing public political arena.

As in the German and Lowland regions, the political climate of Italy during the Middle Ages provided women with definite political abilities that would not be mirrored in the centuries to come. Although the political systems of Italy differed from those of the northern European civilization, as did their economic policies, the prevalence of powerful Italian queens during the early to mid-Middle Ages demonstrates the type of political power that Italian women could indeed wield.

Joan Kelley discusses in her article the two queens Giovanna I of Naples ruling in 1343 and Giovanna II of Naples ruling in 1414. Giovanna I of Naples was designated as heir to rule over the significant kingdom of Naples, Provence, and Sicily, and Giovanna II was similarly afforded this leadership position through the death of her brother.

Besides the powerful queen figure, other feminine rulers also prevailed in medieval Italian political culture. Matilda of Tuscany, who ruled during the eleventh century, reigned as a powerful countess in this region of Italy. She played an essential role in the conflict between Pope Gregory and Emperor Henry IV. Upon being excommunicated from the church due to his defiance to the Pope, Henry IV attacked Rome and drove Gregory into exile.

It was Matilda’s armies that defended the Pope’s church both during the Pope’s lifetime and after his death. Further, Matilda persistently excluded her husband from handling her property and allowed it to remain solely under her control. As with the other women Italian rulers mentioned above, Matilda maintained a definite sense of autonomy, and had been granted a political leadership position.

There, indeed, was a place in the economic and political sectors of society in the German, Lowland, and Italian regions of medieval Europe for the female population. The feudal and family-oriented government structure allowed for women to acquire political power, and the important economic roles that women played in society further influenced their significant status in the cultures of these regions---as David Herlihy states, “women in the early Middle Ages...played a major role in the display of kin connections; they were also stations in the flow of wealth down the generations; they were supervisors, managers, producers.”

Through changes in the political, social, and economic systems of each region, women gradually began to lose much of the economic and political powers that they previously enjoyed, however. In order to demonstrate the extent to which women suffered a loss in status and influential visibility as the Middle Ages approached the opening of the Renaissance, it is prudent to again analyze the German, Lowland, and Italian regions specifically and the changes that occurred in these areas over time. By comparing the society of the later Middle Ages and early modern period to that of the earlier medieval times, the disparities that existed for women are made remarkably evident.

Women in medieval German economic culture, as mentioned above, were active in the textile industries and allowed financial power through inheritance and marriage customs. An examination of the economic actions in later German society reveals a very different feminine condition, however. One of the first aspects of women’s economic involvement that was affected was their role in the textile industry. There was a general increase in both the guild and governmental regulations imposed on women workers.

Research performed by Merry Weisner cited in Judith Brown’s article states the consolidation of guilds in sixteenth and seventeenth century Nuremburg resulted in “regulations excluding women from traditional occupations and relegated them to the margins of the world of work.” In 1421 a major conflict emerged in Cologne concerning religious female weavers and local linen weavers, resulting in a restriction of the number of looms the women could operate.

In the town of Strasbourg, the later Middle Ages saw reductions in the roles of women in the woolen industry; “women at Strasbourg as indeed in many towns were reduced to helpers and auxiliaries.” And women in sixteenth century Nurnberg “successfully protested an ordinance of 1530 [that] deprived them of the right to employ maids in their workshops...their victory was only temporary,” demonstrating the losses in female influence occurring in the later years of the Middle Ages.

Other economic changes ensued regarding a women’s place in society as well. The bridegifts and morning gifts that allowed women to procure economic power through the acquirement of property underwent a series of reductions as the Middle Ages progressed. The earlier gifts often included deeds for property, while over the course of the tenth and eleventh centuries, “fewer deeds gave the wife outright ownership, and even the usufruct was generally restricted to the use of the husband and wife jointly, not to the wife exclusively.” Eventually “daughters claim on the inheritance gradually gave way to the dowry provided by her family,” and the morning gift and bridgegift customs were changed entirely.

Also, a weakening of the feudal system in Germany also accelerated the reduction of a woman’s economic role in society, for the extensive “powers exercised by women were...largely derived from the rather irregular powers held by the great families of the age.” As the Constitutio de feudis of 1037 was passed by Konrad II, women were thereby excluded from the inheritance of fiefs, a measure which over time greatly affected their ability to obtain property and in turn an economic status in society.

To better demonstrate the assertion that women indeed did lose economic clout in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, it is useful to examine the laws of German communities during this time. Such regulations are available for the German town of Madgeburg for the year of 1261. One law providing information about the measures that are taken after the death of a husband states that a widow “shall have no share in his property except what he has given her in court, or has appointed for her dower...if the man has no provisions for her, her children must support her as long as she does not remarry.”

Unlike the customs described in such studies as that conducted by John Freed concerning the Archdiocese of Salzburg, married German women in later medieval society had a very tenuous grasp on property. The economic power that women could accrue through land inheritance prior the later Middle Ages is not at all mirrored in the inheritance laws described for this specific thirteenth century German town

Other evidence exists that demonstrates the economic losses women incurred during the later Middle Ages as well. The Ladies Tournament, a German tale of courtly behavior composed by an anonymous author during the thirteenth century, discusses the proprieties and traditions associated with noble marriage and family life. Although the general pretense of the story is of a community of men and a community of women conversing over matters of courtly rules rather than being an epic tale, its purpose is similar to Ruodlieb’s in that it provides insight into the traditions governing marriage in German society during that time.

In Sarah Westphal-Wihl’s analysis of the story, a marriage is described, as it is in the story of Ruodlieb; however, rather than an exchange of dowries, “the only marital assignment mentioned in the text is the dowry...there is no hint of a contribution from the groom’s side, or of any informal exchange of gifts.”

According to Westphal, the dowry emerged as a custom in Germany by 1200, and although the earlier customs of morning gifts and other gifts on the part of the husband still existed, they are not mentioned in the text of The Tournament of Ladies. This telling omission highlights a growing emphasis on the dowry of a woman, and the concurrent diminishment of a man’s gift to his bride. From the time of Ruodlieb during the eleventh century to that of the Tournament, women’s ability to acquire property and through marriage customs had been altered greatly.

The women of Germany were losing economic influence as the Middle Ages progressed, and comparable losses affected women in the Low Countries as well. Simon’s work reveals that while some “women may have occupied prominent positions in trade and in a few crafts during the thirteenth, fourteenth, and early fifteenth centuries...their numbers declined in the next decades.”

Also, like in the German regions of Europe, restrictions were increasingly placed on female industrial workers; in both Ghent and Flanders “in 1374 the wives of fullers or women of any sort were forbidden to wash any types of clothes.”

Further restrictions were also delineated concerning the economic tasks undertaken by women in beguinages: “because the beguines were able to produce goods cheaply, they found themselves drawn into disputes with the guilds and corporations who considered the beguine activities to be unfair competition.”The earlier urban culture that allowed for a high degree of female participation was doubtlessly being challenged.”

- Susan Papino, Shifting Experiences: The Changing Roles of Women in the Italian, Lowland, and German Regions of Western Europe from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern Period

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

DOMINANT THEMES AND STYLES LITERATURE

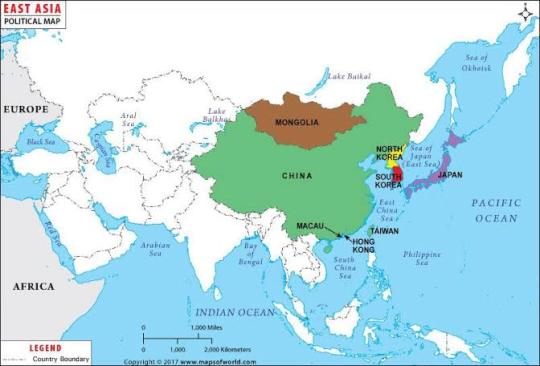

SOUTH EAST ASIA

This area, which embraces the region south of China and east of India, includes the modern nations of Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, The Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia. The earliest historical influence came from India around the beginnings of the Christian era. At a later period, Buddhism reached mainland Southeast Asia. Its influence was a major source of traditional literature in the Buddhist countries of Southeast Asia. Vietnam, under Chinese rule, was influenced by Chinese and Indian literature. Indonesia and Malaysia were influenced by Islam and its literature. All of the countries, except for Thailand, underwent a colonial experience and each of the countries reflects in its literature and in other aspects of its culture the influence of the colonizing power, including the language of that power. Education in the foreign language was to bring with it an introduction to a foreign literature and this, in turn, was to have considerable impact upon their modern forms of literary expression. One finds, then, all the well-known literary genres of Western literature, the novel, the short story, the play, and the essay. Poetry had been the most popular form of the traditional literature over the centuries but was rigid in form. However, through increased acquaintance with Western poetry, the poets of Southeast Asia broke the bonds of tradition and began to imitate various poetic types. A reading list of books is included.

EAST ASIA

Thinkers of the East is a collection of anecdotes and ‘parables in action’ illustrating the eminently practical and lucid approach of Eastern Dervish teachers.

Distilled from the teachings of more than one hundred sages in three continents, this material stresses the experimental rather than the theoretical – and it is that characteristic of Sufi study which provides its impact and vitality.

The emphasis of Thinkers of the East contrasts sharply with the Western concept of the East as a place of theory without practice, or thought without action. The book’s author, Idries Shah, says ‘Without direct experience of such teaching, or at least a direct recording of it, I cannot see how Eastern thought can ever be understood’.

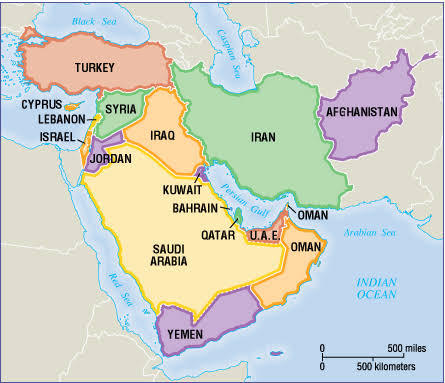

SOUTH AND WEST ASIA

Chicana/o literature is justly acclaimed for the ways it voices opposition to the dominant Anglo culture, speaking for communities ignored by mainstream American media. Yet the world depicted in these texts is not solely inhabited by Anglos and Chicanos; as this groundbreaking new book shows, Asian characters are cast in peripheral but nonetheless pivotal roles.

Southwest Asia investigates why key Chicana/o writers, including Américo Paredes, Rolando Hinojosa, Oscar Acosta, Miguel Méndez, and Virginia Grise, from the 1950s to the present day, have persistently referenced Asian people and places in the course of articulating their political ideas. Jayson Gonzales Sae-Saue takes our conception of Chicana/o literature as a transnational movement in a new direction, showing that it is not only interested in North-South migrations within the Americas, but is also deeply engaged with East-West interactions across the Pacific. He also raises serious concerns about how these texts invariably marginalize their Asian characters, suggesting that darker legacies of imperialism and exclusion might lurk beneath their utopian visions of a Chicana/o nation.

Southwest Asia provides a fresh take on the Chicana/o literary canon, analyzing how these writers have depicted everything from interracial romances to the wars Americans fought in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. As it examines novels, plays, poems, and short stories, the book makes a compelling case that Chicana/o writers have long been at the forefront of theorizing U.S.–Asian relations.

ANGLO -AMERICA AND EUROPE

ANGLO - AMERICA

The Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections has considerable holdings in Anglo-American literature from the 17th century onward, with notable strengths in the 18th century, Romanticism, and the Victorian and modern periods. Among the seventeenth-century holdings is a complete set of the Shakespeare folios, and works by John Milton and his contemporaries. Eighteenth-century highlights include near comprehensive printed collections of Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope, and substantial holdings on John Dryden, Samuel Johnson, Joseph Addison, Sir Richard Steele, William Cowper, Fanny Burney, and others. Related materials include complete runs of periodicals, such as the Spectator and the Tatler.

EUROPE

The history of European literature and of each of its standard periods can be illuminated by comparative consideration of the different literary languages within Europe and of the relationship of European literature to world literature. The global history of literature from the ancient Near East to the present can be divided into five main, overlapping stages. European literature emerges from world literature before the birth of Europe—during antiquity, whose classical languages are the heirs to the complex heritage of the Old World. That legacy is later transmitted by Latin to the various vernaculars. The distinctiveness of this process lies in the gradual displacement of Latin by a system of intravernacular leadership dominated by the Romance languages. An additional unique feature is the global expansion of Western Europe’s languages and characteristic literary forms, especially the novel, beginning in the Renaissance.This expansion ultimately issues in the reintegration of European literature into world literature, in the creation of today’s global literary system. It is in these interrelated trajectories that the specificity of European literature is to be found. The ongoing relationship of European literature to other parts of the world emerges most clearly at the level not of theme or mimesis but of form. One conclusion is that literary history possesses a certain systematicity. Another is that language and literature are not only the products of major historical change but also its agents. Such claims, finally, depend on rejecting the opposition between the general and the specific, between synthetic and local knowledge.

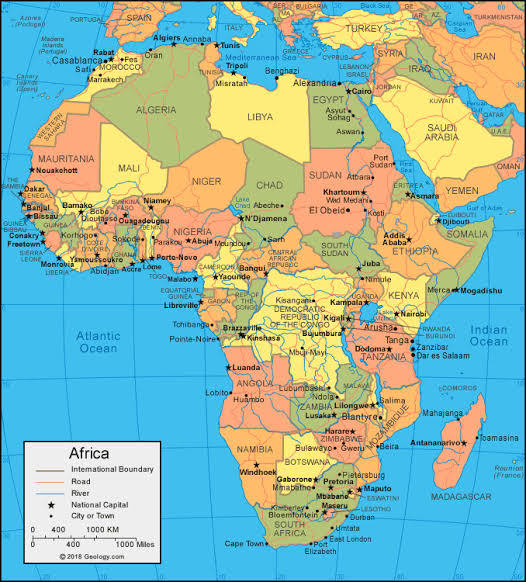

Africa

African literature has origins dating back thousands of years to Ancient Egypt and hieroglyphs, or writing which uses pictures to represent words. These Ancient Egyptian beginnings led to Arabic poetry, which spread during the Arab conquest of Egypt in the seventh century C.E. and through Western Africa in the ninth century C.E. These African and Arabic cultures continued to blend with the European culture and literature to form a unique literary form.

Africa experienced several hardships in its long history which left an impact on the themes of its literature. One hardship which led to many others is that of colonization. Colonization is when people leave their country and settle in another land, often one which is already inhabited. The problem with colonization is when the incoming people exploit the indigenous people and the resources of the inhabited land.

Colonization led to slavery. Millions of African people were enslaved and brought to Western countries around the world from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. This spreading of African people, largely against their will, is called the African Diaspora.

Sub-Saharan Africa developed a written literature during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This development came as a result of missionaries coming to the area. The missionaries came to Africa to build churches and language schools in order to translate religious texts. This led to Africans writing in both European and indigenous languages.

Though African literature's history is as long as it is rich, most of the popular works have come out since 1950, especially the noteworthy Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe. Looking beyond the most recent works is necessary to understand the complete development of this collection of literature

LATIN AMERICA

Latin American literature consists of the oral and written literature of Latin America in several languages, particularly in Spanish, Portuguese, and the indigenous language of America as well as literature of the United States written in the Spanish language. It rose to particular prominence globally during the second half of the 20th century, largely due to the international success of the style known as magical realism. As such, the region's literature is often associated solely with this style, with the 20th Century literary movement known as Latin American Boom, and with its most famous exponent, Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Latin American literature has a rich and complex tradition of literary production that dates back many centuries

Bocar, Mark Jason P.

Stem 11- St. Alypius

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝗔 𝗬𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝗶𝗻 𝗙𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗵, 𝗗𝗮𝘆 𝟰𝟵: 𝗘𝗹𝗳

Elves are a supernatural race of human-like creatures from Germanic mythology. They have become very popular in the modern era, even outside of Western cultures, as a staple figure of the “high fantasy” genre largely thanks to the influence of 𝘓𝘰𝘳𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘙𝘪𝘯𝘨𝘴 author J.R.R. Tolkien.

𝗣𝗿𝗲-𝗖𝗵𝗿𝗶𝘀𝘁𝗶𝗮𝗻

Though the Germanic speaking peoples of Central and Northern Europe had written language, they were never as prolific as the Greeks and Romans and preferred to pass on culture through an oral bardic tradition. By the time they did start writing their own histories, they were already Christian. This puts Elves in an interesting position: we know they were widely believed in and significant cultural features for centuries but their remains incredibly sparse attestation as to what those beliefs actually were. We know elves were popular and common across Germanic peoples for a variety of reasons, one of the easiest being their frequency as a part of names. The record of North, West, and even extinct East Germanic languages all contain many elf-names. The most common one in modern English is “Alfred” literally “Elf-council”. Aside from this, we can only infer. The word “Elf” comes from a Proto-Indo-European word for the color white. Likely this was a reference to a pale complexion. We do know that Elves were supposed to be beautiful, and fair skin is a very common standard for beauty in traditional Germanic cultures. Icelandic poetry tells of an autumn-time ritual called “Álfablót” i.e. “Elf sacrifice” which was celebrated privately. Elves are mentioned sparingly in both the Poetic Edda, a collection of more or less authentic Norse pagan poetry, and the Prose Edda, a 13th century tome written by the Christian Icelander Snorri Sturluson, which together serve as the primary sources of modern knowledge on Germanic mythology. Elves are said to live in Alfheim, which is a heavenly realm alongside Asgard, where most of the Norse gods live. They are particularly associated with the god Frey, a god of kingship, peace, and the harvest. In one poem dominion of Alfheim is given to Frey and his right-hand man, Skirnir, may have been an Elf though it is never explicitly stated. Its possible that Elves in general may have had a close relationship to the class of Norse gods called “Vanir”, of which Frey was one. Because of the sparse attestation of the term Vanir outside of the Eddas it is even possible that the Elves and Vanir are the same, though at this point we are thoroughly in the realm of conjecture. It is also possible that Elves were a generic term for smaller divinities, as later Germanic academics would use the word to translate the Western European “Nymph” a broad class of feminine nature spirits.

𝗟𝗶𝗴𝗵𝘁 𝗘𝗹𝘃𝗲𝘀, 𝗗𝗮𝗿𝗸 𝗘𝗹𝘃𝗲𝘀, 𝗖𝗵𝗿𝗶𝘀𝘁𝗺𝗮𝘀 𝗘𝗹𝘃𝗲𝘀

Belief in Elves changed under Christianization, but it did not die. Christianity is typically dualistic, portraying the earth as a spiritual battleground between good and evil. Germanic paganism lacked this division, and as such Elves did not fall neatly into Christian cosmology. Snorri Sturluson seems to have split the line of Elves into two groups for this purpose: Light Elves (“Ljósálfar”) and Dark/Black Elves (“Dökkálfar” and “Svartálfar”). Snorri’s Light Elves were in-line with what we know of Elves outside of the Prose Edda: Beautiful inhabitants of the heavens. By contrast the Dark Elves lived underground and have unpleasant dark complexions. Its worth noting that its unknown whether or not these Dark Elves were supposed to have dark skin, like humans of African descent, or if it was a more supernatural or corpse-like coloring: the color term most commonly used for African skin tones in the Viking Age was actually “blue”. Regardless, there is no evidence for this distinction amongst Elves outside of the Prose Edda, and it is also possible that Snorri was using “Dark Elf” as an alternate name for another Germanic supernatural race: Dwarves. If this was the case, it would give more credence to the idea of “Elf” as a generic term. In fact, if not the case in pagan times it certainly became the case later, as in the British Isles Germanic Elves and Celtic Aos Sí would syncretize into Fairies, a term that almost completely replaced the word “Elf” in English from Chaucer until Shakespeare. With this syncretism the perception of Elves also changed. While Snorri’s Elves were still human-sized and supernaturally beautiful, Medieval elves became diminutive and funny looking. Negative associations, primarily with mental illness, developed. The modern word for a nightmare in German is “Albtraum”, literally an “Elf-dream”, showing how Elves came to include the Germanic embodiment of sleep paralysis, the Mara (from which the English “nightmare” is derived). With the coming of the modern age, folk beliefs started to lose weight, and fear of Elves or Fairies was replaced with interest and delight. Thus, the arbitrary use of Elf instead of Fairy in notable Christmas poems (ex. 𝘛𝘸𝘢𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘕𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵 𝘉𝘦𝘧𝘰𝘳𝘦 𝘊𝘩𝘳𝘪𝘴𝘵𝘮𝘢𝘴) led to the codification of Santa’s helpers, and other similar crafty spirits, as Elves.

𝗠𝗼𝗱𝗲𝗿𝗻 𝗘𝗹𝘃𝗲𝘀

I have alluded to Tolkien several times in this post as the source of modern conceptions of Elves. It should be noted that he was not the first to re-introduce more “authentic” Elves of Germanic paganism to modern fantasy. 13 years prior to 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘏𝘰𝘣𝘣𝘪𝘵, Lord Dunsay’s 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘒𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘰𝘧 𝘌𝘭𝘧𝘭𝘢𝘯𝘥’𝘴 𝘋𝘢𝘶𝘨𝘩𝘵𝘦𝘳 featured human sized beautiful and magical Elves, even including the term “Elfland” as an equivalent to the Norse Alfheim. That said, it is definitely Tolkien’s works that directly inspired the subsequent resurgence in Elf popularity. Even the spelling of words like “Elvish” instead of “Elfish” are Tolkien constructions, a choice made to make the word seem more authentically Anglo-Saxon. Though there are some instances of Victorian depictions of Fairies/Elves with pointed ears it’s uncertain if this was why Tolkien described his Elves as having “leaf-shaped” ears. Regardless, this feature has easily become their most distinctive. Curiously, this is particularly pronounced in the art of modern Korea and Japan, where Elves are commonly drawn with ears that are pointed, much longer, and angled away from the head more than human ears. The star Elf of Tolkien’s 𝘓𝘰𝘳𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘙𝘪𝘯𝘨𝘴, Legolas, is specifically responsible for the association of Elves and archery and forestry, even though these features were specific to him as a woodland ranger, not to Tolkien Elves in general. The role-playing game 𝘋𝘶𝘯𝘨𝘦𝘰𝘯𝘴 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘋𝘳𝘢𝘨𝘰𝘯𝘴 further expanded Tolkien tropes, and borrowed Snorri’s Light Elves and Dark Elves to create subdivisions that mirrored distinctive fantasy tropes: Elves as near-divine magicians (High Elves), Elves as woodland Fairies (Wood Elves), Elves as tricksters and maladies (Dark Elves). Between Tolkien’s influence on fantasy novels and 𝘋𝘶𝘯𝘨𝘦𝘰𝘯𝘴 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘋𝘳𝘢𝘨𝘰𝘯𝘴 impact on games, both video and analog, the long lived and long eared Elf is now a staple of even non-Western fantasy and are increasingly viewed more distinctly from Fairies. Ironically, though much of modern Elf tropes are modern inventions, they have become much more similar to the pagan Elves of Central and Northern Europe than the Elves of the Medieval ages, successfully distilled from centuries of syncretism.

Image Credit: Art from 𝘔𝘢𝘨𝘪𝘤: 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘎𝘢𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘳𝘪𝘯𝘨 card 𝘞𝘰𝘰𝘥 𝘌𝘭𝘷𝘦𝘴, by Rebecca Guay, 1997

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gum Recession Grow Back

Despite the fact that dental care was certainly not a concentrated branch of Ayurveda, it is actually consisted of in its own Shalakya Tantra (body of surgical operation). Problems including impairments of the oral cavity, oral plaque buildups and diseases were actually taken care of in ancient India. Standard medicine may manage various contagious as well as chronic problems. For more about Grow Back Receding Gums

Research has presented that all sort of eating sticks illustrated in old Ayurveda content possess therapeutic as well as anti-cariogenic buildings. Its oil taking (Kaval, Gandush) practice is actually asserted to cure about 30 systemic ailments.

Gum Regrowth Treatment

Amla (Emblic myrobalan), is actually a basic rebuilder of oral health. Bilberry fruit (Vaccinium myrtillus) and hawthorn berry (Crateagus oxycanthus) support bovine collagen, reinforcing the gum tissue. Liquorice root (Glycyrrhiza glabral) markets anti-cavity action, minimizes cavity enducing plaque, and has an antibacterial impact. Use risk-free, quality items as well as techniques need to be actually made sure based upon readily available proof if standard medicine is to become acknowledged as part of main health care. Scientific verifications of the Ayurveda dental health strategies can justify their consolidation right into modern dental care. Promotion of these methods using ideal media would certainly benefit the basic populace by offering additional assurance in the old techniques, thus protecting against dental caries and also loss. Keyword phrases: Ayurveda, kaval, oral health, oil taking, traditional medication Go to: INTRO

Ayurveda is actually an all natural system of medication which grew in India some 3000-5000 years ago, a body of standard medicine belonging to the Indian subcontinent, now performed in various other component of the world as a form of corresponding medicine. [1] The earliest literary works on Indian medical technique appeared throughout the Vedic duration in India. The Susruta Samhita as well as the Charaka Samhita are its earliest authoritative messages. [2] Over the centuries, Ayurvedic practitioners built great deals of medical preparations and surgical procedures for the treatment of several health problems as well as diseases. [3] Although dentistry was actually not a specialized branch of Ayurveda, it was actually featured in its own device of surgery. In ancient India, concerns like impairments of the mouth, oral plaque buildups and also diseases might be handled and also also treated.

Gum Regrowth Treatment At Home

Conventional medication is actually the sum total of knowledge, capabilities and strategies based on the ideas, opinions as well as knowledge indigenous to various cultures that are actually used to preserve health, and also to prevent, identify, boost or deal with physical and mental illnesses. Standard medication that has been actually embraced by other populaces (outside its own indigenous culture) is commonly labelled complementary or even holistic medicine. Natural medicines consist of herbs, organic materials, plant based prep work, and finished herbal products which contain portion of plants or even various other plant products as energetic components.

In some Asian and African nations, 80% of the population depends upon typical medication for main medical. In a lot of established nations, 70% to 80% of the populace has actually made use of some type of substitute or corresponding medicine. Organic treatments are actually the most preferred form of standard medicine, and also are extremely beneficial in the global market place. Yearly incomes in Western Europe got to US$ 5 billion in 2003-2004. In China sales of items headed to US$ 14 billion in 2005. Organic medicine profits in Brazil was US$ 160 thousand in 2007. [4] Ayurveda and also oral health

In Ayurveda, dental health (danta swasthya in Sanskrit) is upheld be actually really individual, varying with each person's nature (prakriti), and also weather modifications resulting from sunlight, lunar and planetary effects (kala-parinama). The body system constitution is actually classified based upon the preponderance of several of the 3 doshas, vata, pitta as well as kapha. The domination dosha in both the personal and also attribute finds out medical in Ayurveda, featuring dental health.

Natural Gum Regrowth

[5] Most likely to: EATING STICKS

Ayurveda suggests chewing embed the morning along with after every meal to stop ailments. Ayurveda insists on making use of herbal combs, around 9 inches long as well as the density of one's little finger. These natural herb sticks ought to be either 'kashaya' (astringent), 'katu (acrid), or 'tikta' (harsh) in flavor. The approach of making use of is to crush one point, chew it, and consume it little by little. [6] Toothbrushing is actually a task executed with a 'tooth brush' which is an exclusive little brush designed for make use of on teeth. Nibbling a therapeutic stick equivalent advised by a Vaidya, or other typical practitioner, might validly be actually upheld be equivalent to the western-pioneered activity of 'brushing the teeth ', however it is actually not adequately similar to become given the exact same name, especially given that sticks that are munched are made use of totally in different ways coming from combs.

It is actually advised that chewing sticks be acquired from new controls of details plants. The neem (margosa or even the Azadiraxhta indica) is a famous organic chewing stick. The stems need to be actually well-balanced, soft, without leaves or knots and also drawn from a healthy tree. Nibbling on these stems is strongly believed to result in attrition and levelling of attacking areas, help with salivary secretion and, possibly, assistance in oral plaque buildup control, while some stems have an anti-bacterial action. With reference to the individual's constitution and also dominant dosha, it is actually specified that folks with the vata dosha dominance might establish atrophic and also receding gums, as well as are encouraged to utilize chewing stick to bitter-sweet or even astringent preferences, including liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) and black catechu or even the cutch plant (Acacia Catechu Linn.), specifically.

Natural Gum Regrowth Treatment

[7] Pitta dosha leading individuals are highly recommended to use chewing stick to an unsweetened flavor like the branches coming from the margosa plant (Azadirachta indica or even natures neem) as well as the arjuna plant (Terminalia arjuna). Those with the kapha dosha prevalent are probably to have light as well as hypertrophic gums and are actually asked to utilize chewing sticks with a poignant taste, presenting the fever nut (Caesalipinia bonduc) and the typical milkweed vegetation (Calotropis procera). Present-day research has actually revealed that all the chewing sticks defined in historical Ayurveda content (circa 200 BC) possess therapeutic and also anti-cariogenic properties. [8] Saimbi et al (1994) assessed the anti plaque effectiveness of Neem remove, Ayurvedic tooth grains and also commercial tooth pastes. Neem extract prevailed as well as commercial tooth pastes were actually the last. [9] In one more research study Venugopal et al (1998) assessed a total amount of 2000 children (1-14 year age group) in Mumbai for cavities incidence. Those children who were actually utilizing natures neem datun were located to be less impacted along with cavities. [10] In southern India, mango fallen leave is actually largely used for cleaning teeth. A clean mango leaf is actually washed and the midrib is cleared away. Fallen leave is actually then folded up lengthwise with shiny surfaces encountering each other. It is rolled into a round pack. One point of the pack is bitten off 2-3mm to develop a raw surface area which is rubbed on the teeth - pack is actually held in between the thumb as well as the forefinger. In the end, the midrib, which was first removed, is actually made use of as a tongue cleaner. Sumant et alia (1992) assessed the efficiency of mango fallen leave as an oral health help and also acquired interesting results. [11] Much higher soft down payment ratings were stated in team that made use of mango leaf. Cavities knowledge in this group utilizing mango leaf was similar to the group that utilized tooth comb. Mangiferin a substance found in mango leaves had considerable antibacterial property against particular strains of Pneumococci, Streptococci, Staphylococci, as well as Lactobacillus acidophilus.

Gum Regrowth At Home

The miswak (miswaak, siwak, sewak) is actually a teeth washing branch created from a branch of the Salvadora persica tree, additionally called the arak plant or even the peelu plant and also functions in Islamic health jurisprudence. The miswak is predominant in Muslim locations yet its make use of precedes the inception of Islam. Almas and also Atassi (2002) carried out research to analyze the effect of miswak and also tooth brush filaments end-surface structure on enamel. Twenty-one specimens were actually prepared; they were actually divided right into Aquafresh toothbrush team, Miswak group as well as command team. End results revealed that filaments end-surface texture play major duty in abrasive energetic activity as well as enamel tooth area loss. Miswak revealed smaller result on enamel as compared to Aquafresh toothbrush. [12] Almas and Zeid (2004) in a research to determine antimicrobial activity of miswak chewing embed vivo, particularly on streptococcus mutans and also lactobacilli confirmed that miswak had a prompt antimicrobial result reviewed to toothbrush. Streptococcus mutans were more at risk to miswak than lactobacilli. [Thirteen]

1 note

·

View note

Text

meta on media consumption as beholding, and the creation of the conservator role, based on conversations with @hdtvtits. content warning, as always, for addiction, compulsive / obsessive behavior, aggressive hoarding, and implied terminal illness, all of the eldritch variety. also allusions to real-life hollywood dramas, though nothing remotely specific is discussed in this post.

foreword: this is just the first part of a bunch of meta i’ll likely end up posting on why levi is what they are and why their beholding manifests the way it does, because like... for secrets and the underbelly of film production i have a lot to say but a lot to source as well. but there are a few things i want to address in this post, namely: what the eye feeds off of, whether or not levi is feeding the eye in their media consumption ( and how ), and how it ultimately serves the eye’s purposes to have this be levi’s method of feeding. this probably won’t even be my last post on the subject as i keep sort of logicking out the way that beholding works and how it can manifest. it’s important to me though that it exist and function outside of just what happens in the institute ( which is proven in the statements ), mostly because fear entities are global and primal and jonny said that the story really is britain-centric. now, media consumption isn’t particularly groundbreaking; it addresses a more american culture, but that’s still western-centric and sort of ‘typical’ of europe and america, though i will say that european filmmaking as an institution is... different. it has its own history and quirks. hollywood is its own beast. someday i’ll make a post on levi’s judaism and how that interacts with beholding and manifests as more than their aesthetic, because they haven’t even used their ayin hara on this blog yet though it’s a ( minor ) power they possess, but that deserves its own post. ANYWAYS. with that said.

what does the eye feed off of? the eye doesn’t just function based off a primal fear, it has a drive that it imbues its servants with: “it is the manifestation of the fear of being watched, exposed, followed, of having secrets known, but also the drive to know and understand, even if your discoveries might destroy you.” i think that most of the entities function in a similar way, with the things they inspire and feed off of on the one hand, and avatars with a desire to evoke that fear in the other; i.e., avatars create food to feed their entity, and if they don’t, the entity devours them instead. that’s pretty basic knowledge. ( i also have stuff to say about entities consuming themselves because every time claire says autocannibalism i go absolutely hog wild about it but that’s for another day. ) there are, then, multiple ways that an avatar can go about gathering fear for its entity, but what sets the eye apart from others, i believe, is that it doesn’t need to directly cause the fear it consumes -- though i think that it finds the fear of being watched more filling than just watching other people be afraid, it can still ‘survive’ off of that. this is where eye shit starts to get confusing and it’s why these posts are so longwinded and involve me talking myself in circles, because the eye both has a specific fear that it’s linked to and can devour other people’s experiences of fear that it did not cause, yes even before the apocalypse. that’s just how jon feeds for the majority of the series. for a good long while, he’s not going out and getting statements himself; and even when he does, he’s double dipping on both the fear they convey to him about their experiences ( knowledge gained ) and the fear that this man is pulling information out of them ( secrets exposed ).

but that’s jon and we’re not talking about jon, we’re talking about levi, and my ever-evolving thesis on voyeurism in / and media.

so what does an eye avatar need to do, exactly, to eat? it needs to accumulate knowledge, that’s the baseline that it can survive off of -- knowledge of the other entities is best, but i don’t know that it’s a requirement... and i don’t know if it’s not! i am going to make the call that eye avatars can survive off of just hoarding information because the eye isn’t super picky and wants to know everything anyways, but not feeding off of fear for a long time is going to leave the avatar really weak. and for an eye avatar to develop its powers and grow, it needs to take statements directly, or else give other people the distinct feeling of being observed against their will. the more people it feeds off of as a result of its own actions, the more powerful it becomes. that said, i don’t think this is common, which is why watchers ( heads of institutes ) have set up these systems where they’re generating food for themselves on two axes simultaneously: fear of people who give statements, and fear of people who have to work at their institutes ( either taking statements or working directly under the eye ). that just sort of accumulates power upwards within eye bureaucracies, though the archivists who take and sort the statements are also going to become remarkably powerful if they lean into their role.

( also side note: these systems work for the english, american, and chinese institutes, but there are ways for beholding avatars to thrive outside of them, and again someday i’m going to post about oral traditions and the ability to craft stories in different regions of beholding that feed the eye. but i need to do research first and we’re talking about levi! )

here’s the thing... levi is not an archivist. levi is not powerful. levi does not have a strong connection to beholding. they worship it, but fanaticism does not equal feeding, sadly, and the role they’ve been given is not one that pushes them to go and gather statements for themselves. they have taken read and statements at afi, because wyatt was raising them into an avatar, but, though conservators and archivists can overlap in the real world, they ( in my word of god for this blog’s canon and the monster i made up ) are two very different things under the eye. essentially, conservators serve archivists ( and watchers ) by witnessing, recording, and playing back statements that archivists can then maneuver through. the more experienced the conservator, the more they can shift the camera, allowing the archivist to comb through statements in detail and pull the knowledge that they want from them. remember that the beholding grants knowledge, not understanding, and while that may be fine for the eye, sometimes its ‘human’ servants need to put the pieces together in order to advance its plans.

the conservator is a relatively new position within beholding, because it does function like a film camera. i think that, in other times, places, and cultures, there were similar avatars who filled a similar role, but it wasn’t the same. the conservator really is a miskatonic / american experiment to help the institute delve into the information it already possessed. for one example of how conservators are useful, consider what happened with sasha: the archivist had his voice recordings of her, because it can’t effect magnetic tape, but jon the person still had her wiped completely from his memory. that wouldn’t happen to a conservator, because all of their memories are converted into (meta)physical tape stock. they are a lockbox that cannot be opened or altered unless you’re a more powerful beholding avatar. ( the limitation here is that they only have so much storage space, they will need to expunge some memories to store more; though those memories can be kept in physical containers, film stock obviously degrades and is a very unstable and extremely flammable medium; their body will also internally decompose to make room for more data and that is a painful process that eventually renders the conservator just a storage without any ability to function beyond sitting still and replaying witnessed / read events. )

we’ve established that levi feeds normally. they take statements, they are present in an archive, they’re hearing the scary stories. finally, finally on to why levi consumes media and how levi consumes media, because the one is intrinsically linked to the other. let me start by saying that just watching television or films does not a beholding avatar make. yes you are watching, but the distinction is in whether you are passively or actively viewing. and the power that is drawn from someone zoning out and being addicted to passively consuming media does not go to the eye. that is neither a fear of being observed ( for the one watching or for the actors / writers, because nobody is going to care about an audience that doesn’t form an opinion at all beyond basic emotional reactions; uncritical consumers are milk and honey to them ) nor a pursuit of knowledge ( passively accepting knowledge is, according to elias, far less effective in raising up eye avatars than letting them learn to ‘see’ on their own ). all that power goes to mx media ( @hdtvtits ) or, if you don’t like crossovers, Just Definitely Not the Eye. it’s when you start performing analysis that the eye takes interest -- which is why the eye continues to thrive in academia ( au where i write meta on just how bad that gets, historically, but again there are things we don’t get into until we research thoroughly ). the more you lose yourself in compiling information, to the exclusion of everything else, the more you appeal to beholding. and when you start unveiling secrets, which there are plenty of in film and film production, things kept private from the audience, ‘movie magic’, then feeding can begin.

this may come as a surprise, but levi does not have a response to whether or not they ‘like’ movies. if you ask them, ‘did you enjoy that movie?’ they will not say ‘yes’ or ‘no’, they will just start launching into ripping it apart. levi probably started out enjoying movies recreationally, but at some point, they became not just unwilling to but incapable of watching films without analyzing -- and what separates this from normal people who are conscientious and engaged viewers is that this is a mania that spans hours. their ‘digestion’ of a film is obsessive and has a physical component because it is eldritch in nature. i can’t stress enough that levi isn’t just a pretentious film buff who says ‘oh i can’t consume media for pleasure or uncritically’, though they may have been at some point in their college career! they have a physical and metaphysical makeup that drives them to frenzy over what they watch. the instant they finish a film, they’ll begin a rapid accumulation of knowledge of anything they can dig up: the who, what, when, where, why, how. if they do have an emotional response, it’s incredibly removed, and their way of processing it is to drill into how and why the film made them feel that way.

if they try to avoid this step in the process -- if they just watch a movie, turn it off, and attempt to go to bed -- they will start to weaken immediately. watching the movie isn’t enough for feeding. if it was, the eye wouldn’t take any interest at all. it’s the genuinely out-of-control driving impulse to keep researching and researching until there is nothing left about a piece of media that isn’t known, shredding through academic papers and script drafts and director’s notes and interviews and everything they can get their hands on, that stems from and feeds beholding. they do not settle for what is put on the screen. they will even cold call creators in a fit and try to get them to talk about the production ( which is, yes, invasive -- beholding is an eldritch entity, it is not healthy or good and does not inspire healthy or good habits! ).

they may not even be capable of enjoying a piece on its own merits; it’s all about the world it opens up to them, it’s about stuffing themselves with information until they can’t breathe and overstimulate and pass out. then recovery from that can take days as they process what they learned and sort it all out in their mind. they don’t really do much with this information; just knowing it is enough. if an archivist or watcher wants to take action about it, they can ask levi to spit it back up for them. but ultimately, despite the impact that this has on their health, this is still low-level feeding for a low-level avatar. unless it’s a truly gruesome movie or has an exceptionally shady production background, it’s not really the fear that the eye is looking for. levi is feeding one half of beholding, the half that wants them to consume knowledge and secrets. if levi didn’t take / read statements as well, or go out and witness live horrific events, they would probably starve -- their body would eat itself processing knowledge.

and i will talk about the component of parasocial relationships, anxiety that stems from being an actor / director / content creator in general and having your work and your image spiral out of control as it’s ripped apart and dissected by consumers, because that is beholding territory as well. it’s just not actually what levi does, but because it relates to the media-beholding relationship, i’ll have it on this blog.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Do Gums Grow Back?

Although dentistry was not a focused branch of Ayurveda, it is consisted of in its own Shalakya Tantra (device of surgical treatment). Concerns like impairments of the oral cavity, cavity enducing plaques and contaminations were handled in early India. Traditional medicine may treat numerous contagious as well as persistent problems. Read more about Will A Receding Gum Grow Back?

Research has presented that all kinds of eating sticks described in ancient Ayurveda content possess therapeutic as well as anti-cariogenic residential or commercial properties. Its oil pulling (Kaval, Gandush) practice is actually stated to cure about 30 systemic conditions. Amla (Emblic myrobalan), is an overall rebuilder of oral health. Bilberry fruit (Vaccinium myrtillus) and hawthorn berry (Crateagus oxycanthus) maintain bovine collagen, strengthening the gum cells. Liquorice origin (Glycyrrhiza glabral) promotes anti-cavity action, lowers oral plaque buildup, as well as has an antibacterial effect.

Can Your Gum Line Grow Back?

Use of safe, top quality items as well as practices must be actually made certain based on available evidence if standard medication is actually to be acknowledged as aspect of main medical. Scientific verifications of the Ayurveda dental health practices can warrant their consolidation right into modern dental treatment. Publicity of these approaches using suitable media would certainly help the general populace by giving more self-confidence in the historical techniques, therefore protecting against dental caries as well as loss. Keywords: Ayurveda, kaval, oral health, oil taking, conventional medicine Go to: INTRODUCTION

Ayurveda is an all natural system of medication which grew in India some 3000-5000 years ago, a body of traditional medication native to the Indian subcontinent, right now performed in other parts of the globe as a kind of corresponding medication.

[1] The earliest literature on Indian medical technique appeared during the Vedic time period in India. The Susruta Samhita as well as the Charaka Samhita are its earliest authoritative messages. [2] Over the centuries, Ayurvedic practitioners developed large numbers of medicinal plannings as well as procedures for the treatment of numerous disorders and also ailments. [3] Although dental care was certainly not a specialized branch of Ayurveda, it was consisted of in its unit of surgical operation. In historical India, concerns including deformities of the oral cavity, cavity enducing plaques and diseases can be handled and also also healed.In another research of clients with hypertension, extreme gum disease was associated with damage left wing side of the heart.

How To Grow Back Receding Gums Naturally?

Typical medicine is the result of know-how, skill-sets as well as techniques based upon the theories, beliefs and expertises aboriginal to various cultures that are utilized to maintain health, and also to stop, identify, enhance or alleviate physical and also mental illnesses. Conventional medication that has actually been taken on through other populations (outside its own indigenous lifestyle) is actually frequently termed complementary or natural medicine. Organic medications feature cannabis, plant based materials, plant based preparations, as well as finished plant based products that contain parts of plants or even various other plant products as active elements.

In some Asian and African countries, 80% of the populace depends on typical medicine for primary healthcare. In many industrialized countries, 70% to 80% of the populace has actually utilized some kind of different or complementary medicine. Organic therapies are one of the most well-liked type of standard medication, as well as are extremely financially rewarding in the worldwide marketplace. Yearly profits in Western Europe connected with US$ 5 billion in 2003-2004. In China sales of items visited US$ 14 billion in 2005. Organic medication income in Brazil was actually US$ 160 thousand in 2007. [4] Ayurveda and oral health

In Ayurveda, dental health (danta swasthya in Sanskrit) is held to be incredibly self-loving, differing along with everyone's nature (prakriti), and weather modifications coming from solar energy, lunar as well as earthly impacts (kala-parinama).

Grow Back Receding Gums Naturally

The physical body constitution is categorized based upon the preponderance of one or more of the 3 doshas, vata, pitta as well as kapha. The prominence dosha in both the personal and nature identifies medical care in Ayurveda, consisting of dental health. [5] Go to: EATING STICKS

Ayurveda recommends eating embed the early morning in addition to after every meal to avoid diseases. Ayurveda insists on using natural brushes, about 9 ins long and also the thickness of one's little hands. These natural herb catches must be actually either 'kashaya' (astringent), 'katu (acrid), or 'tikta' (bitter) in taste. The technique of making use of is to crush one end, eat it, and eat it little by little. [6] Toothbrushing is actually a task accomplished along with a 'toothbrush' which is a special little comb made for use on teeth. Biting a therapeutic stick equivalent encouraged through a Vaidya, or even other typical specialist, might validly be actually held to be equivalent to the western-pioneered task of 'brushing the teeth ', yet it is certainly not adequately comparable to become provided the same name, exclusively given that sticks that are actually munched are actually made use of totally in a different way from brushes.

It is actually suggested that nibbling sticks be actually obtained coming from fresh contains of certain vegetations. The natures neem (margosa or the Azadiraxhta indica) is actually a popular herbal chewing stick. The contains must be healthy and balanced, soft, without fallen leaves or even knots as well as taken from a healthy and balanced plant. Eating on these arises is felt to trigger weakening and levelling of biting areas, assist in salivary tears as well as, possibly, support in oral plaque buildup command, while some stems possess an anti-bacterial activity.

Will Gums Grow Back?

Apropos of the person's constitution as well as dominant dosha, it is mentioned that people along with the vata dosha prominence might build atrophic and receding gums, and also are advised to use chewing sticks with bitter-sweet or even astringent preferences, such as liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) and black catechu or the cutch plant (Acacia Catechu Linn.), specifically. [7] Pitta dosha prevalent individuals are actually recommended to make use of chewing stick to an unsweetened taste like the branches coming from the margosa tree (Azadirachta indica or natures neem) and also the arjuna plant (Terminalia arjuna). Those with the kapha dosha prevalent are actually likely to possess light and also hypertrophic gums as well as are asked to utilize chewing stick to a pungent taste, presenting the high temperature nut (Caesalipinia bonduc) and also the usual milkweed plant (Calotropis procera). Modern investigation has revealed that all the chewing sticks described in ancient Ayurveda text messages (circa 200 BC) possess medical and also anti-cariogenic attributes. [8] Saimbi et alia (1994) checked the antiplaque efficiency of Neem extraction, Ayurvedic tooth powders as well as office tooth pastes. Natures neem extraction triumphed and also office tooth pastes were the final. [9] In yet another study Venugopal et alia (1998) studied a total of 2000 little ones (1-14 year generation) in Mumbai for decays occurrence. Those kids who were actually utilizing natures neem datun were found to be much less influenced along with cavities. [10] In southern India, mango leaf is actually largely made use of for cleansing teeth. A clean mango fallen leave is cleaned and the midrib is removed. Leaf is at that point folded lengthwise with glossy surface areas experiencing each other. It is actually rolled into a cylindrical pack. One end of this pack is actually bitten off 2-3mm to create a raw surface area which is wiped on the teeth - pack is held between the finger and also the index finger. By the end, the midrib, which was first cleared away, is actually utilized as a tongue cleaner. Sumant et alia (1992) examined the efficacy of mango leaf as an oral hygiene aid as well as gotten exciting searchings for.

How To Strengthen Gums Naturally?

[11] Greater smooth down payment scores were actually stated in team that used mango fallen leave. Cavities experience in this group using mango fallen leave was similar to the group that utilized tooth brush. Mangiferin a material current in mango leaves had considerable antibacterial characteristic versus certain strains of Pneumococci, Streptococci, Staphylococci, and also Lactobacillus acidophilus.

The miswak (miswaak, siwak, sewak) is actually a teeth cleansing twig created coming from a branch of the Salvadora persica tree, additionally called the arak tree or even the peelu plant and features in Islamic health law. The miswak is predominant in Muslim regions but its own use precedes the inception of Islam. Almas and also Atassi (2002) performed study to examine the effect of miswak as well as tooth comb filaments end-surface structure on enamel. Twenty-one samplings were readied; they were actually arranged right into Aquafresh toothbrush team, Miswak team and also control team. Outcomes revealed that filaments end-surface texture action primary role in rough active activity and polish tooth surface area loss. Miswak showed lesser impact on enamel as contrasted to Aquafresh toothbrush.

Do Receding Gums Grow Back?

[12] Almas and Zeid (2004) in a research to analyze antimicrobial activity of miswak eating stick in vivo, specifically on streptococcus mutans and lactobacilli confirmed that miswak possessed a prompt antimicrobial impact compared to toothbrush. Streptococcus mutans were even more susceptible to miswak than lactobacilli. [13]

1 note

·

View note

Text

Queer Positive Deities

Keep in mind that this is NOT a complete list of ALL pantheons and deities that are queer positive. This is a good majority, but by all means it is NOT all of them. Also not all photos would fit.

DISCLAIMER

This wiki will contain sexual terms and other mature items that each deity represented or did in their specific pantheon. If any of it bothers you, please exit the wiki and move on from it. Thank you.

Achilles (Greek)

The Greek hero Achilles was invulnerable excepting his famous weak heel, but a male shieldbearer broke through the warrior’s romantic defenses. While Homer never explicitly states a gay relationship between Achilles and sidekick Patroclus, many scholars read a romantic connection between the two, as only Patroclus ever drew out a compassionate side to the famously arrogant warrior. Patroclus’s death at the hands of Trojan Prince Hector sent Achilles into a rage in which he killed Hector and dragged his body around Troy. Other myths also disclose Achilles was struck by the beauty of Troilus, a Trojan prince.

Adonis/Tammuz (Phoenician/Greco-Roman/Mesopotamian)