#mormaer of Moray

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

On August 15th 1057 Scottish monarch, MacBeth, was killed at Lumphanan.

The saying, You live by the sword, you die by the sword, is certainly true in the case of MacBeth, as I told you yesterday he seized the crown at Pitgaveny some 17 years before, MacBeth must surely have been a true Warrior King.

Considered to be one of the last Gaelic kings, Macbeth was a king of the Scots whose rule was marked by efficient government and the promotion of Christianity, but who is best known as the murderer and usurper in William Shakespeare’s tragedy.

Shakespeare’s Macbeth bears little resemblance to the real 11th century Scottish king.

Mac Bethad mac Findláich, known in English as Macbeth, was born in around 1005. His father was Finlay, Mormaer of Moray, and his mother may have been Donada, second daughter of Malcolm II. A ‘mormaer’ was literally a high steward of one of the ancient Celtic provinces of Scotland, but in Latin documents the word is usually translated as 'comes’, which means earl.

His marriage to Kenneth III’s granddaughter Gruoch strengthened his claim to the throne. In 1045, Macbeth defeated and killed Duncan I’s father Crinan at Dunkeld.

For 14 years, Macbeth seems to have ruled equably, imposing law and order and encouraging Christianity. In 1050, he is known to have travelled to Rome for a papal jubilee. He was also a brave leader and made successful forays over the border into Northumbria, England.

In 1054, Macbeth was challenged by Siward, Earl of Northumbria, who was attempting to return Duncan’s son Malcolm Canmore, who was his nephew, to the throne. In August 1057, Macbeth was killed at the Battle OTD by Malcolm Canmore who later became Malcolm III, Macbeth's Stone, a large boulder at the site, is said to mark the spot where Macbeth was mortally wounded. as seen in the pic.

You can find a full biography on this relatively overlooked King here

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Macbeth: The Scottish King Behind the Myth

Early Life and Ancestry: Roots in the North Macbeth was born around 1005, a son of Findláech of Moray, a powerful Mormaer (regional ruler) in northern Scotland. The Mormaer of Moray held significant power and autonomy in the region, which was often at odds with the central authority of the Scottish kings based in the south. Moray, along with other regions like Ross and Galloway, was…

1 note

·

View note

Text

1130 AD: Slaughter at Stracathro

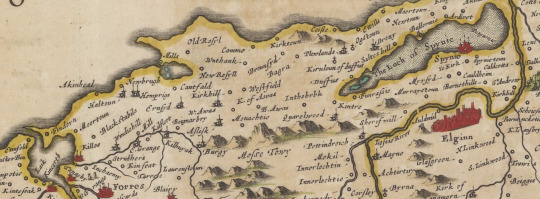

(Detail of Angus from Robert Edward’s map of 1678- Stracathro can be seen north of Brechin on the banks of the Esk. Clicking on the image should make it larger. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland)

In the year 1130, an army led by Angus, ruler of Moray, was defeated by forces loyal to David I, King of Scots, at the Battle of Stracathro. Although this engagement was recorded by a wide variety of medieval chroniclers and historians, few provide any details about the course of the battle or its background. Even the exact date is unclear. Nonetheless, Stracathro is often seen as a pivotal moment in the relationship between the powerful lords of Moray and the developing kingdom of Scotland, and an important flashpoint in the domestic politics of David I’s reign.

To make sense of the various surviving accounts of this battle, it is necessary to give some background information on Angus of Moray’s status. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, ‘Moray’ covered a much larger area than it does now. A territory which stretched from the north-east to Ross, its rulers often found themselves in competition with the neighbouring jarls of Orkney and the kings of Alba, the latter of whom were then expanding their territory to include Strathclyde and Lothian south of the Forth, forging what we would now recognise as the kingdom of Scotland. However it is unclear whether Moray’s lords were independent rulers or regional lieutenants of the kings of Alba. The current academic consensus seems to be in favour of the latter, with some historians calling the rulers of Moray ‘mormaers’ (literally ‘great steward’ but often seen as equivalent to ‘earl’). Nevertheless Moray’s medieval inhabitants may well have seen things differently. At any rate, the rulers of Moray were clearly powerful figures in the north, with a close (if often fraught) relationship with the rulers of what we now call Scotland.

This closeness increased in 1040 when Moray’s ruler, Mac Bethad Mac Findlaích (Shakespeare’s ‘Macbeth’) seized the throne of Alba. Mac Bethad had claimed Moray after his cousin Gillecomgain burned to death in 1032. He had also swiftly married Gillecomgain’s widow Gruoch* who was a granddaughter of Kenneth III, king of Alba. Some years later, Mac Bethad defeated the then king of Alba, Duncan I, in battle near Elgin, and claimed the throne of Alba. He ruled for seventeen years before his own death at Lumphanan in 1057, following his defeat by forces loyal to Duncan’s son Malcolm III. Mac Bethad was briefly succeeded by his stepson Lulach ‘fatuus’ (‘the simple’), son of Gillecomgain and Gruoch, before Lulach too was killed in 1058 and Malcolm III succeeded in wresting control of Scotland...

(The Laich of Moray in the Blaeu Atlas of 1654. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland)

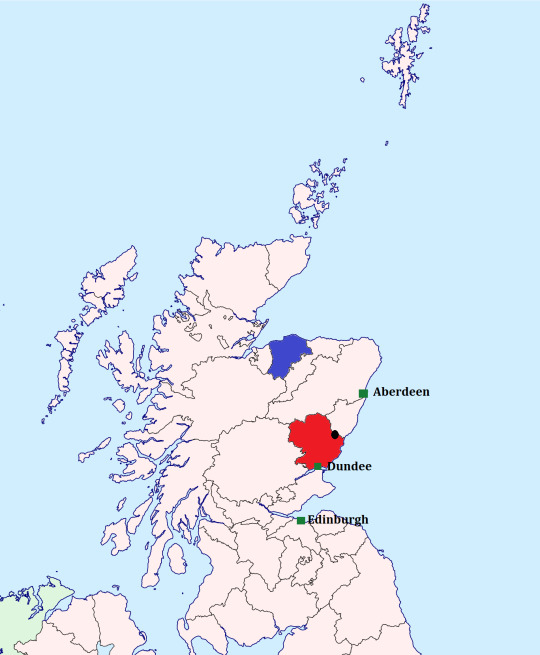

(The shire of Moray is highlighted in blue and Angus (Forfarshire) in red. The old county system was only beginning to emerge in David I’s reign, and Moray in particular referred to a much larger province than shown here. The black spot shows the general location of Stracathro- I am no cartographer however, so this is only a rough guide. Template Source).

No more kings of Alba would be drawn from the house of Moray after Lulach’s death. A short conflict between Malcolm III and Lulach’s son Máel Snechta did break out in 1078: Máel Snechta got the worst of it but may have reached an agreement with Malcolm, since his kinsmen continued to rule in Moray for some decades. After this no serious challenges came from Moray for over fifty years until 1130, when another descendant of Lulach- his daughter’s son Angus- was ruler of the province.

Although we know something of his maternal ancestry (his father is a complete mystery), Angus of Moray is still a rather obscure figure. Late mediaeval Irish annals call him ‘rí’ or ‘king’ of Moray. Conversely, contemporary Anglo-Norman sources, as well as the Chronicles of Melrose and Holyrood, and late mediaeval Scottish historians like John of Fordun, all use the Latin word ‘comes’, which implies that they saw Angus’ position as roughly equivalent to that of a count or earl. Some bias is to be expected from Anglo-Norman sources since they usually favoured the descendants of Malcolm III and St Margaret over other branches of the royal house. Nonetheless we lack convincing evidence that the early twelfth century rulers of Moray controlled an independent kingdom, though they might perhaps have been ‘subkings’. We do know that Angus had a reasonably good claim to rule over both Moray and Alba, and the men of Moray were clearly willing to support him in this. And yet there had been no recorded conflict for over fifty years, so why did Angus choose to make his move in 1130?

Perhaps the answer can be found in the internal politics of the Scottish royal house. By 1130, David I, the youngest son of Malcolm III by his second wife Margaret of Wessex, had worn the title ‘King of Scots’ for six years. Although history remembers David as an impressive and innovative monarch- one of those kings who ‘made’ Scotland- in the early years of his reign his power seems to have been centred on the southern provinces of Lothian and Strathclyde. His control of ‘Scotia’ or Alba- the traditional heartland of the kingdom north of the River Forth- was less certain, and he must have seemed a very distant figure in a place like Moray. He also had to contend with rivals for the throne, like Malcolm, the son of David’s older brother and predecessor Alexander I. Described by the contemporary Anglo-Norman chronicler Orderic Vitalis as illegitimate, in an age when this did not yet disqualify a man from kingship, Ailred of Rievaulx later called Malcolm, ‘the heir of his father’s hatred and persecution’.* He may have opposed his uncle David at the outset of the reign, though if so he was plainly unsuccessful. This was not to be the last of Malcom’s intrigues however, since he pops up again a few years later in the company of Angus of Moray, taking part in the invasion of Alba in 1130. Perhaps then Malcolm’s appearance in Moray meant that he was able to convince Angus to support his claim and that this provided the impetus for the invasion. However it must be said that, in general, Angus is presented as the real leader of the campaign. Most sources do not even seem to think Malcolm’s presence at Stracathro worth mentioning, while Orderic Vitalis wrote that Angus ‘entered Scotland with the intention of reducing the whole kingdom to subjection’, and merely notes that Malcolm accompanied the army.

(David I and his grandson Malcolm IV, in a twelfth century charter belonging to Kelso Abbey. Source- Wikimedia commons)

(The round tower at Brechin, a few miles south of Stracathro, was likely constructed in the twelfth century, if not earlier. It is one of only two such round towers in Scotland)

It is also worth bearing in mind that, at the time of the invasion of Alba, David I was probably hundreds of miles away in the south of England, attending the court of his brother-in-law King Henry I. Although David’s relationship with the English king had proven useful on many occasions, this time it might have provided Angus and his allies with the perfect opportunity to revolt. Perhaps his absence also provided motive: later twelfth century kings of Scots would occasionally face armed opposition to their prolonged absences from the realm, and it is possible that Angus sought to capitalise on any discontent. Whatever the ultimate cause of their revolt, the year 1130 saw Angus and Malcolm march south with an invasion force which is said to have been 5,000 strong.

Contemporary sources do not tell us much about the course of the campaign. Only the late fourteenth century historian John of Fordun, who hailed from the Mearns himself and probably drew on earlier sources, gives a location for the sole recorded battle- Stracathro, near Brechin in Angus. This suggests that Angus of Moray’s army either headed south by one of the tracks over the Grampian mountains or, perhaps more likely, travelled east in the direction of Aberdeen and from there made its way down the low-lying strip of land between the Mounth and the coast. This last route would have covered roughly similar terrain to the modern A90 road and, although the landscape of long rolling fields sloping away towards the blue foothills of the Mounth in the west may have looked very different in the twelfth century, its strategic value for a mediaeval army on the move is readily apparent. The Romans had already marched across this ground a thousand years earlier, leaving the remains of a camp at Stracathro, and the conquering forces of Edward I of England would later follow a similar route north in 1296. It is also clear that, despite the sparse details given in contemporary sources, and despite David I’s posthumous legacy as a strong monarch, the 1130 invasion represented a serious crisis. In the absence of any recorded opposition, Angus and his supporters had been able to overrun the fertile east coast of ‘Scotia’, not far from the Tayside heartlands of the kingdom, and only forty miles or so from the traditional coronation site at Scone.

The men of Moray were only brought to a halt when King David’s constable Edward, son of Siward, hastily assembled an army and cut Angus’ force off a few miles north of Brechin. Orderic Vitalis, the contemporary writer who describes the battle in the greatest detail, tells us little about Edward other than that he was ‘a cousin of King David’ and the son of Siward who, according to various translations, was an ‘earl’ or ‘tribune’ of Mercia. Since his name and paternity indicate that he was of English stock, it is possible that Edward was one of the king’s maternal cousins, but theories abound as to his exact identity. Previously, several historians accepted the theory that he was the son of Siward Beorn (the earl of Northumbria who fought against Macbeth) and thus an uncle of David I’s queen Matilda. However this does not really tally with the few details Orderic provides, and any son of Siward Beorn would likely have been in his seventies in 1130. More recent writers, including David I’s most recent academic biographer, favour Ann Williams’ identification of Edward as a son of Siward, son of Aethelgar, a Shropshire thegn and therefore both of Mercian descent and, like David, a great-great grandson of Aethelred the Unready.

(View of Stracathro and the surrounding country in James Dorret’s map of 1750. I have coloured the kirk of Stracathro in red so it can be spotted more easily; again clicking on the image should expand it. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland)

The royal army clashed with Angus and his men at Stracathro. No source gives a blow-by-blow account of the battle but the result was clear. In a rout which the Irish Annals of Innisfallen described as the ‘Slaughter of the men of Moray in Scotland’**, Angus and most of his force were killed. We should be wary of mediaeval chroniclers’ tendency to play fast and loose with numbers, but the language which all sources use about the engagement indicates that the death toll was high, with the late mediaeval Annals of Ulster even claiming that as many as 4,000 of the men of Moray were killed- 80% of the force which Orderic Vitalis claimed Angus was able to put into the field. The Annals of Ulster also claimed that a thousand of the men of Scotland (or ‘alban’) died, but this number was later corrected to one hundred. Leaving the chroniclers’ suspiciously exact death tolls aside, it is clear that the battle of Stracathro was a catastrophe for the Moravians, and a blood-bath from which Angus’ co-commander Malcolm, the son of Alexander, was very lucky to escape. Fleeing soldiers from Angus’ shattered army were then chased back to Moray by the triumphant Edward and the Scots, who promptly established control over the province.

Both mediaeval chroniclers and more recent historians have traditionally made this annexation of Moray following the battle seem very easy. As Robert de Torigni neatly summed it up, ‘Angus, the earl of Moray, was killed; and David, the king of Scotland, held the earldom thenceforward’. Now the undisputed overlord of Moray, David I is then supposed to have set about a comprehensive programme of ‘feudalisation’, complete with reformed monastic orders, a reorganised diocesan system, royal burghs for controlling trade, and, of course, a new settler nobility. However, David’s most recent academic biographer, Richard Oram, has argued that this feudalisation of Moray may have been a slower process than is often implied, and that it took some time for David and his supporters to establish complete control over the old lordship. Indeed, although there was to be no more trouble from Moray until the reign of David’s grandson King William, the fact that rivals for the Scottish throne were still able to draw considerable support from the native nobility of the province in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries could indicate that the post-Stracathro reorganisation was not so complete as some writers have assumed.

Stracathro is now a quiet place. A century and a half after the battle the area witnessed another, less bloody, defeat when John Balliol and his council negotiated with the triumphant Edward I of England from the kirkyard of Stracathro in July 1296. But other than this Stracathro is probably best known for its community hospital and a Victorian walled garden. The Battle of Stracathro is not exactly the most famous event in the annals of Scottish history. In a county that is otherwise littered with carved stones which allegedly commemorate ancient battles, few traces of the twelfth-century skirmish remain. Two mounds near Ballownie farm used to be pointed out as the alleged burial site of the slain, and certain internet etymologies claim that the nearby place name ‘Auchenreoch’ can be interpreted as deriving from a term meaning ‘the field of great sorrow’***. But otherwise the battle of 1130 has not left much of a mark in the landscape. Modern perceptions of the battle are also influenced to a great extent by the accounts of Anglo-Norman chroniclers, who may well have downplayed the threat which Angus of Moray (and other twelfth century rivals for the throne) posed to the descendants of Malcolm III and St Margaret. Nonetheless the slaughter at Stracathro is worth commemorating: had the battle gone the other way, Scotland might have been a very different place today.

(Stracathro Mansion is not necessarily on the site of the battle, and the landscape has changed considerably in nine hundred years, even down to the way fields are ploughed. However this may at least give an idea of the surroundings of the north part of Angus, with the Mounth in the background. Reproduced under the Creative Commons License (source here) since I’m limited in the photos I can take personally right now for obvious reasons).

Notes:

* Everybody’s favourite ‘Lady Macbeth’

**Not to be confused with Malcolm MacHeth

*** The original Irish says ‘Albain’

**** Though it must be said, I have my doubts

Selected Bibliography:

“The Ecclesiastical History of England and Normandy”, by Orderic Vitalis, Vol. III, translated by Thomas Forester

“Early Sources of Scottish History”, ed. A.O. Anderson

“Rerum Hibernicarum Scriptores”, vol. 2, ed. Charles O’Conor

“Annala Uladh”, vol. II, edited and translated by B. Mac Carthy

“Chronicle of Melrose”, and the “Chronicle of Holyrood” trans. Rev. Joseph Stevenson in ‘The Church Historians of England’, vol. IV

“Scottish Annals From English Chroniclers”, ed. A.O. Anderson

“John of Fordun’s Chronicle of the Scottish Nation”, ed. W.F. Skene and trans. Felix Skene

“Kingship and Unity: Scotland 1000-1306″, G.W.S. Barrow

“The Kingship of the Scots”, A.A.M. Duncan

“Domination and Lordship: Scotland, 1070-1230″, Richard Oram

“David I”, Richard Oram

“’Soldiers Most Unfortunate’: Gaelic and Scoto-Norse Opponents of the Canmore Dynasty, c.1100-c.1230”, R. Andrew MacDonald

“Companions of the Atheling”, G.W.S. Barrow in ‘Anglo-Norman Studies 25: Proceedings of the Battle Conference 2002′

#Scottish history#Scotland#British history#battles#medieval history#twelfth century#historical events#1130s#David I#Angus of Moray#Mediaeval#Middle Ages#High Middle Ages#warfare#Malcolm son of Alexander I#Moray#mormaer of Moray#Macbeth#Lulach (d. 1058)#Mael Snechta of Moray#Malcolm III#Malcolm Canmore#House of Canmore#Angus#Stracathro#Battle of Stracathro#Forfarshire#north-east

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Malcolm is... back on his feet, I should speak to him about Lulach’s inheritance and titles. Some of them, anyway. I don’t want to create conflict over the throne.

But Lulach’s mormaership must be retained. He’s Gilcomgain’s son and would have been mormaer after his father, after all. And I hear that the men of Moray are getting restless. If Lulach is secure in his inheritance and on good terms with the crown, it might settle them.

...This is good stew.

#(bodhe’s trying to ensure lulach has some kind of future)#(a mormaer is kind of like an earl#(and the mormaer of Moray was practically a king)

1 note

·

View note

Text

People, Macbeth

Macbeth at the fort of Macduff. C. 1005 AD. He was born. 1031 AD. Cnut the Great came north to accept the submission of King Malcolm II, Macbeth too submitted to him. 1032 AD. He became Mormaer of Moray (a semi-autonomous lordship). 1040 AD. Macbeth’s troops killed Duncan I after he attacked Moray. Macbeth then succeeded him as King of Alba, apparently with little opposition. 1052 AD. He was…

View On WordPress

# Edward the Confessor# Godwin#Battle of Lumphanan#cnut the Great#Duncan I#Earl of Northumbria#Earl of Wessex#feudalism#Holinshed&039;s Chronicles#Iona#king#king of Alba#Kingdom of England #Macbeth#Malcolm III#Mormaer of Moray #Norman#People#Scotland#Scottish kings#Shakespeare#Siward

0 notes

Text

Sure, we all know Lady Macbeth:

"Look the innocent flower but be the serpent underneath it."

But don't imagine Gruoch, married for the first time sometime before turning 17 to a king, to a fully-grown man. Don't imagine Gruoch as a young maiden queen, don't imagine Gruoch as a pretty jewel owned by a careless Mormaer. Did she have sisters? Did she cry for her mother at night? Did she already mourn for her autonomy the way that she would only 8 years later? Don't imagine Gruoch with her infant son, Lulach, the only joy in her world. Did he know of his mother's grief? Or did she protect him from the world that wronged her?

Now don't imagine Gruoch, watching her husband burned to death in a hall with 50 of his men the year she turns 17. Was she relieved? Did she finally think she could be free? Or did some weak, womanly part of her love him? Love this man who made her the most powerful woman in Moray (now know as Scotland)? Don't imagine Gruoch losing her only brother the year after. Was he kind to her? Did she chase after him, the way that little sisters do to their older brother? Did he love her?

Gruoch marries Macbeth that year, the cousin of her first husband and the new king of Moray. He adopts her son as his heir. He makes her the Queen of Scotland. Did he complement her on her hair or tell her he likes the way she smiles? Did he hold her baby boy and call him 'son'? Did he let her become 'Lady Macbeth' or was she Gruoch to him?

Did she finally get the autonomy she craved? Was she a mad woman, a mad 25 year old witch who welcomed the dark to her heart and killed a king? Or was she eighteen and desperate to give, give, give (because that's the only thing she knows) to the only man who gave her respect? Or was she seventeen and riddled with grief but without the freedom to show it? Or was she a child, wronged and wronged and wronged again and fighting for her rights the only way she knew?

Sure we all pretend to know Lady Macbeth, but don't imagine Gruoch.

Look the innocent flower but be the serpent underneath it.

#lady macbeth#Lady Macbeth#macbeth#shakespeare#writing#musings#spilled ink#imagine#creative writing#literature#words#my writing#writblr#writers#dark academia#look the innocent flower#but be the serpent underneath it

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

some facts until i write out a proper history:

gruoch is married off at about 17 to the mormaer of moray, gille coemgáin.

he has designs on the the alban throne, and gruoch’s father, perhaps to capitalise on his own ambitions, ignores the blatant risk of the match.

gruoch’s family’s ambitions and that of her husband put a target on all of their backs, and malcolm ii sends macbethad to deal with the threat in moray.

realising the misstep, gille coemgáin tries to barter with macbeth, offering gruoch’s life and that of their unborn child in exchange for the sparing of his own.

exceedingly offended, gruoch stabs her husband herself.

macbeth was happy enough to kill gille coemgáin for his own reasons as well as malcolm’s, so burns his body with 50 of his men and calls that job done.

he is decidedly less enthusiastic to carry out malcolm’s orders in regards to gruoch and offers to marry her to give her his protection.

#[ please note this blog is entirely selfindulgent and not intended to be actual historial just fake historical really ]#𐩐 ᚌ 。 ch. thoughts ── ooc.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

King Malcolm IV was born April 23rd 1141.

This is another of those dates that can only be guessed at, a lot of sources merely say circa 1141 but we have to place him somewhere in our history to remember him by, some give his birth date as early as March, or as late as May, we have to place him somewhere so I’m going with the lowest end of the wiki entry of 23rd April 1141 – 24th May 1141.

The son of Henry of Scotland, Earl of Huntingdon and Ada de Warenne, daughter of William de Warenne, Earl of Surrey and Elizabeth de Vermandois. Henry died after a prolonged period in June 1152, but left three sons. As the eldest of these and the new heir to the Scottish throne, his grandfather sent Malcolm on a circuit of the kingdom, accompanied by Donnchad, Mormaer of Fife, who was styled rector, possibly an indication that he was to hold the regency for Malcolm on David's death. As it turned out, Donnchad did not long survive David, holding the regency for a year before his death in 1154.

Malcolm’s, ( Máel Coluim mac Eanric in Gaelic) Grandfather was King David I, and Malcolm succeeded him at the age of twelve he was crowned at Scone on May 27th 1153.

Malcolm inherited the Earldom of Northumbria, which his father and grandfather had gained during the wars during the time of what was known in England as The Anarchy when King Stephen and Empress Matilda had fought for the English crown. Malcolm granted Northumbria to his brother William, retaining Cumbria for himself. While Malcolm delayed doing homage to Henry II of England for his possessions in England, he finally did so in 1157 at Peveril Castle in Derbyshire and later at Chester. Here King Henry refused to allow Malcolm to keep Cumbria, or William to keep Northumbria but instead granted the Earldom of Huntingdon to Malcolm, for which Malcolm did homage. He later fought with the English King in France and was present at the siege of Toulouse.

At home Malcolm faced a rebellion lead by the pretender to the Scottish throne, Malcolm Mac Heth. Mac Heth was aided by Somerled, The uprising erupted in Moray and the town of Glasgow was sacked by Somerled. Somerled, fearing for his safety, attempted a pre-emptive strike at Renfrew with a large army he had gathered in Ireland but was betrayed and he and his son murdered. King Malcolm was reconciled with Máel Coluim Macbeth, who was appointed to the Mormaerdom of Ross, which had probably been held by his father Malcolm never married or had issue. Pious and frail, he is purported to have taken a vow of celibacy. He reigned for only twelve years and died of unknown causes at the age of twenty-four on 9th, December 1165 . He was buried at Jedburgh Abbey, which had been founded by his grandfather, David I and was succeeded by his wee brother William who got the nickname The Lion through his adoption of a red lion rampant as his standard.

The second pic is titled Treaty of Chester 1157 - Malcolm IV of Scotland submits to Henry II.(Plantagenet)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

2020

Happy New Year everyone! To celebrate the start of the 2020′s, I thought I’d take a look back through some eras of history my friends and I have been into over the years.

The year is 2020.

Somewhere, it is 1920.

The war in Europe has been over for 2 years and we are celebrating, living in excess, with no fear of the imminent stock market crash that will end this decade. In Russia, the revolution has succeeded, and the country is in the midst of civil war.

Still somewhere else, it is 1620.

James I of England has been ruling for seventeen years and will die within the next five. William Shakespeare has been dead for 4 years now. The Mayflower is sailing for the Americas. Meanwhile, witch hunts begin in Scotland.

Then, it is 1520.

Henry VIII reigns in England, married to his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. Martin Luther began the Protestant Reformation three years ago, which will set about religious turmoil in Europe for centuries to come.

Once again, it is 1020.

Mormaer of Moray, Finlay Mac Rory will be killed by his nephews Gillecomgan and Malcolm Mac Malbrid within the year. His son, the future King Macbeth I will be turning fifteen, while the future Lady Macbeth, Gruoch Ingen Bodhe, will be turning 5. England is ruled by Cnut the Great. His son, Harold Harefoot, will be turning 4, while Harthacnut will turn 2.

Further back, and it is 20 B.C.E.

A grandson will be born to Emperor Augustus Caesar. In the same year, Lucius Antonius, the grandson of the late Mark Antony, will be born. Augustus will live for 34 more years, while Antony’s body has been buried in a tomb that has never been found to this day.

At last, it is 1320 B.C.E.

Egypt’s 18th Dynasty is coming to a close. Pharaoh Ay, successor to the more famous Tutankhamun, rules for four years from 1323-1319 B.C.E. Tutankhamun, having no surviving children, had been succeeded by his Grand Vizier.

Still, life continues on. Happy 2020. Love y’all, keep being you.

-Hal

#shut up dangos#happy new year!#I am targeting specific people#you know who you are#I chose these events for a reason

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

To Malcolm, King of Scots:

You may have lately received word that I have claimed the mormaership of Moray. I will begin by saying this is the truth, and further explain my reasons.

Moray is a large region, and was for these past several months without a mormaer. Winter was coming on, and the people had no one to oversee preparations, no one to provide patrols to guard against raids or accidents, no one to provide judgment in personal disputes.

As the late King Macbeth’s cousin, I am aware of the Scottish laws of succession, which allow for cousins to succeed each other. The nearest heir apparent, Lulach mac Gilcomgain, has refused the position, and no other close kin to the previous mormaer was living. Therefore, it seemed only right that the mormaership fall to me. I have been riding through Moray recently, and seeing to the needs of my tenants and villeins. Their worries are fewer now that they have someone in authority to come to.

I am also aware that Moray is rich in trade goods, and the Ness offers a route for Norse boats to come trading from Orkney, thus enriching both regions.

I have nothing but concern and care for the people of Moray, and shall strive to guard the region well.

Respectfully,

Thorfin Sigurdsson

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't think I ever labored under the impression that Shakespeare's historical plays had him sacrifice potential drama for historical accuracy, but the only ways in which the Scottish play resembles history are this:

Macbeth (Mac Bethad mac Findlaích, or "Macbeth son of Findlay") was a King of Alba, he succeeded Duncan I, he was married to a woman named Gruoch, and Duncan's son Malcolm III ruled after Macbeth died

What actually happened:

Macbeth became Mormaer of Moray upon the death of his cousin Gilla Comgain (Gillie Coemgáin) in 1032;

Duncan I of Alba, who ascended to the throne in 1034, after some other military disasters marched on Moray in 1040, where Macbeth's soldiers killed him in battle (it's definitely possible that Macbeth killed him personally, since Macbeth was a lead-from-the-front sort);

Macbeth assumes the throne of Alba, apparently unopposed;

Macbeth rules for 17 years over a largely peaceful Kingdom of Alba and Mormaerdom of Moray, with the first major conflict being an invasion by English forces (bloody Englishmen, they just start invading as soon as you look away) in 1054;

A rebellion led by the future Malcolm III (Máel Coluim mac Donnchada, Malcolm son of Duncan) culminated in the Battle of Lumphanan in 1057, where Macbeth was beheaded after his forces were defeated; it's worth noting that Malcolm was backed by the same English Earl of Northumbria who'd tested Macbeth a few years earlier

Macbeth was succeeded by his stepson (and cousin) Lulach mac Gillie Coemgáin (Lulach, son of Gilla Comgain), who ruled less than a year (August 15th, 1057 to March 17th, 1058) before Malcolm III had him assassinated and usurped the throne that would have theoretically gone to Lulach's son Máel Snechtai, who ruled as Mormaer of Moray while he unsuccessfully prosecuted his claim to the throne of Alba

So, in reality, Malcolm III was the bad guy… sort of. See, Malcolm III earned the epithet Canmore, or ceann mòr, and he ruled Scotland for 35 years and proved to be an adept statesman; his descendants went on to found multiple royal houses of both Scotland and England, and so on. And Malcolm III died protecting Scottish interests from English incursion.

Do you ever just think about how Gargoyles’s version of Macbeth, who rode around on a hover scooter and shot lasers at people, was actually more historically accurate than the Shakespeare version?

Because I do. All the time.

521 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In 1020 when MacBeth was fifteen years old, MacBeth's father Findlay MacRuaridh, Mormaer of Moray, was killed by his brother's two sons, MacBeth's cousins. There appears to be only one theory about his murder which was the jealousy by the houses of Moray and Atholl, and that Findlay had allowed Moray to be too close and friendly with Atholl — which was Malcolm II's house. One of the murderous nephews was then elected Mormaer of Moray. He controlled Moray until he died when his murderous brother, Gillecomgain, was elected Mormaer of Moray in 1029. Gillecomgain had ambitions to become the High King. To strengthen his position he married Gruoch, grand-daughter of Kenneth III whom Malcolm II had killed in order to gain the High Kingship. She and her brother were Kenneth III's only surviving grandchildren, Malcolm II having killed all the others.

Malcolm II did not find this growing power of Gillecomgain to his liking. In 1032 men of Atholl, perhaps under direct orders of Malcolm II, surprised Gillecomgain Mormaer of Moray, and fifty of his men in his fortress burnt them to death. It seems probable that Gruoch and her son were also intended to be killed but they were absent at the time. The widow Gruoch's son to Gillecomgain, Lulach, was ultimately MacBeth's successor as High King. The struggle between Moray and Atholl was growing more acute. Malcolm II by this time was in his late seventies and the succession was a matter of concern. Malcolm II had nominated his eldest grandson Duncan, son of Crinan the Mormaer of Atholl, to be his successor. But that was subject to the approval of the electors when the time came. Duncan's most likely challengers at an election were likely to have been Gillecomgain, who had been murdered, and Gruoch's brother Malcolm MacBodhe, surviving grandson of Kenneth III. Malcolm II had arranged the murder of Malcolm MacBodhe in 1033. Following the death of Gillecomgain, the position of Mormaer of Moray fell vacant. MacBeth, then aged 23 years, was elected. There is no record of any dissent by any of the Moray clans which tends to confirm that MacBeth was not seen as being allied to the Atholl men or Malcolm II who were responsible for the death of Gillecomgain. Further, MacBeth now married his widow Gruoch and adopted her son Lulach, thereby giving them the protection of the House of Moray against the House of Atholl.”

Malcolm D. Broun, ‘MacBeth, King of Scots, 1040-1057,’ in Journal of the Sydney Society for Scottish History, Vol. 8 Nov 2000, p. 18.

this is actually a really good summary of this blog’s take on gruoch’s story...

0 notes

Text

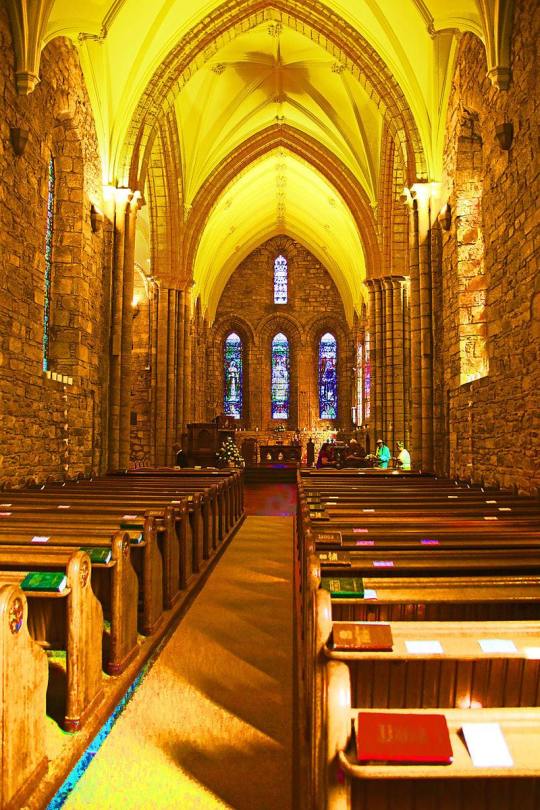

1st April 1245 saw the death in Scrabster Castle of Gilbert de Moravia Bishop of Caithness and the man who founded Dornoch Cathedral.

Gilbert de Moravia was the son of Muiredach, who in turn was son of Alexander de Moravia. The names suggest a noble family with roots in Moray, and it is thought that Gilbert was a cousin of William de Moravia, who became 1st Earl of Sutherland in 1230. Having chosen to pursue a career in the church, Gilbert spent a number of years serving as the archdeacon of the Bishopric of Moray. He was appointed to the position of Bishop of Caithness in 1222 by King Alexander II of Scotland.

As much as the Church had power back in the god fearing Medieval times the job of Bishop had it's risks. Gilbert's predecessor, Adam of Melrose, had been killed at his residence in Halkirk by farmers angry at a doubling in the episcopal tax levied on agricultural production, and Adam's predecessor had himself had his eyes and tongue removed by Harald Maddadsson, Earl of Orkney and Mormaer of Caithness, ironically for resisting increases of taxation on the peasantry.

Gilbert de Moravia owned estates in and around what is now Dornoch, and it was felt that it would be safer for him to move the seat of the diocese south. Gilbert therefore commissioned (and paid for) a Cathedral Church in Dornoch, as well as residences for ten canons. Gilbert himself was based at Skibo Castle, while spending some of his time in the more turbulent north at Scrabster Castle. His successors as bishop would establish a palace in Dornoch that has since evolved into Dornoch Castle.

Gilbert died at Scrabster Castle on 1st April 1245, and has since been said to have been "one of the noblest and wisest ecclesiastics the medieval church produced." He was buried at Dornoch, and his relics lay there until the wanton destruction during the Reformation.

Gilbert was the last pre-Reformation Scotsman to be canonised, and his achievement in erecting a building of the size and stature of Dornoch Cathedral in such a remote corner of the Scottish Highlands in the 13th century is truly remarkable.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well, Moray is a powerful enough region that their mormaer is sometimes called their king. Your mother was “small queen” of Moray before she was Queen of Scots. And Thorfin does have the right to claim the title. But I’m not entirely easy about this. Malcolm should have been told what’s going on before we were.

How about I write a letter, and read it back to you, and then you can sign it? And when you head back to Lochaber, I’ll make copies of the letters for you to give to Malcolm.

Lulach, a messenger is here with a letter for you- it’s from Jarl Thorfin of Orkney.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Setting the King on his Throne: Isabella of Fife, Countess of Buchan

It’s been a while and I hope everyone had a good new year! For my part, I’m kicking off the year with a rather well-known figure: Isabella of Fife, Countess of Buchan, one of the most famous women of the Wars of Independence (no mean feat- there are not enough famous ladies, but there are quite a lot who deserve to be). Aside from her actions in 1306 and subsequent imprisonment, Isabella is quite a shadowy figure, but she is a highly important one in Scottish history and definitely deserves a place on this blog. After all, if you can't find room in your day for a woman who defied her husband and the English king to crown Robert Bruce, I don't even know what you're following for.

It is unclear just when Isabella was born. There is even uncertainty over who her parents were- some sources say she was the sister of Duncan IV, Earl of Fife, others claim she was his aunt. That would mean she was either the daughter of Colban, Earl of Fife, and his wife the daughter of Alan Durward, or she was the daughter of Duncan III, Earl of Fife, and his wife Joanna de Clare, daughter of the Earl of Gloucester- the latter is generally thought more likely but it is an open debate. Perhaps we can vaguely put her birth date between 1265 and 1285, but given that both her (supposed) father and grandfather died young it is difficult to be sure. Earl Colban died in the early 1270s, while Duncan was murdered in 1289, leaving a similarly young son named Duncan as his heir. The younger Duncan would be considered a minor until after the end of the century- if Isabella was his sister, she cannot have been much older, though was certainly of age to be married before 1297. In the meantime, their uncle, known to us only as MacDuff (perhaps indicating that he was considered head of the kindred even if his nephew was earl) and apparently a brother of Earl Colban, caused some trouble over properties he believed had been left to him by his father.

In any case, Isabella was daughter to the Earl of Fife, who, although he was not always the most politically or territorially powerful of Scotland’s magnates, was generally regarded as symbolically ranking first among them. We can safely say that Isabella counted among her ancestors such notable figures as Llywellyn the Great, Prince of Wales, Alexander II of Scotland (and thus through him she was descended from personages such as David I and St Margaret), and Adeliza of Louvain second wife to Henry I of England, whilst if she was the daughter of Joanna de Clare, she could also count among her ancestors Isabella of Angouleme (through the Lusignans) and Strongbow. Although Fife is now a firmly Lowland county- or kingdom- in the thirteenth century it still retained much of its Gaelic character, even though English was probably the main language of its bustling east coast burghs. The mormaers- later earls- of Fife, members of the Clan MacDuff, had been the chief lords in the area since the tenth century. Over more recent centuries they had acquired the “right” to a special role at the coronation of the kings of Scots- that of placing the king on the stone of Scone, as other kings might be placed on a throne. With young Earl Duncan still in his minority, a knight named John of St John was nominated to fill this role at the coronation ceremony of John Balliol in 1292. Nonetheless, the symbolic role of the earls of Fife, and their status as heads of the political community, was still highly respected.

(Some key locations and regions for the life of Isabella of Fife. The dots aren’t quite in their exact positions, because I’m not great at geography, but it’s just meant to give an idea.)

As the daughter of the Earl of Fife, Isabella was expected to make a profitable marriage and she wed John Comyn, Earl of Buchan before 1297. The Comyn family, especially the Badenoch and Buchan lines, were the most powerful baronial family in Scotland during the late thirteenth century. This was especially true north of the Forth where their lands stretched from Buchan in the east to Lochaber in the west, though they also had sizeable holdings south of the Forth and in England. They had played a leading role in Scottish politics during the reigns of Alexander II and Alexander III, and continued to do so during the uncertainty following the latter’s death. Their importance only grew in 1292, when John Balliol ascended to the Scottish throne, a man whose sister was married to John Comyn of Badenoch, and was mother to John ‘the Red’ Comyn. This meant that Isabella’s husband was not only one of the most important magnates in the realm and one of King John’s main supporters, but was also cousin to the man who was next in line for the throne should the Balliol line fail.

All this rather long-winded scene-setting aside, as we all know, John Balliol did not have a great time as king. Eventually, with Edward I becoming increasingly overbearing, and the unfortunate King John increasingly browbeaten, a council of Scottish magnates, including the Comyns, removed the power from the King of Scots’ hands. Determined not to give in to the English king’s demands, which would have been seen as confirming Scotland’s subservient position, they continued to pursue an alliance with the French. This led to the Scottish Crown’s decision to physically support the French (and perhaps also preempt an English attack) by assembling the realm’s army, and this in turn resulted in a short war in which the Scots were quickly overcome at the Battle of Dunbar. King John fled into the north-east but was later forced to surrender and was publicly stripped of his crown, while the Comyns, like the rest of the Scottish nobility, were eventually received into the English king’s peace.

(John Balliol doing homage to Edward I of England)

It was not long before trouble broke out again in Scotland, when William Wallace and Andrew Moray rose up in 1297. The Earl of Buchan was technically supposed to be keeping the peace but, like many Scottish magnates, he seems to have cautiously remained on the fence. We have no indication of his wife Isabella’s opinion during this troubled period, except a grant that allowed her to take wood from near to her husband’s Leicestershire property, which indicates she was still in the king of England’s good books and living reasonably peacefully. Her possible mother, Joanna de Clare, was not so lucky during this troubled period, and in 1299 brought charges against a Scot named Herbert de Moreham for having ambushed, abducted, and imprisoned her upon her refusal to marry him, and then having robbed her of her possessions to the tune of two thousand pounds. Meanwhile, Isabella’s brother/nephew, Duncan, became a captive in England, though he nominally retained his title. Her kinsman MacDuff, was less easily cowed, taking part in Wallace’s rebellion and leading the men of Fife against the English, though this ended with his death at the Battle of Falkirk in 1298.

Though this long (but nonetheless very generalised) explanation of the events of the 1290s is somewhat necessary to understand the context of Isabella’s lifetime, it is to the year 1306 that we must look for her real activity. In this year, Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick, shocked the political community on both sides of the border when, in Greyfriars church in Dumfries, he stabbed John Comyn of Badenoch during what was supposed to be a peace conference. By primogeniture, and with the Balliols sidelined, Comyn had a better claim to the throne, so by murdering him Bruce had, quite ruthlessly, cleared a path to the kingship. But he had also enraged both Edward I of England and the entire Comyn family network (and their many allies) who, although hitherto as flexible with their patriotism and loyalty to the king of England as any other Scottish nobles, now found themselves firmly in the English camp as Bruce claimed the throne of Scotland. The Earl of Buchan, then in England, would have been furious at his cousin’s death, and whether Isabella of Fife was with her husband or not, she would have been well aware of the implications of Bruce’s bloody attack on her marital house, an act for which he was excommunicated.

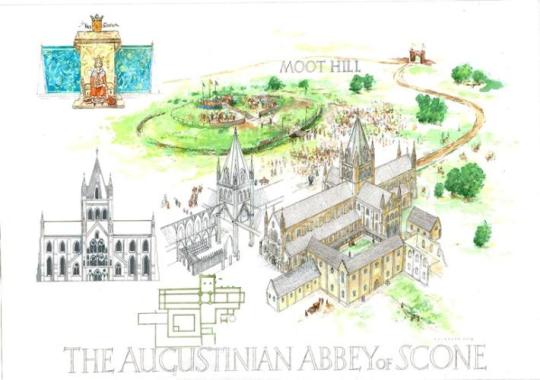

(An artist’s depiction of Scone Abbey in c.1371- not my picture, found here)

For some reason, though, Isabella seems to have viewed the situation very differently to her husband. The previous Earl Duncan of Fife may have been loosely associated with the Bruces in the past and this might have left a mark on Isabella’s allegiances. Or perhaps she viewed Bruce as a candidate who could genuinely lead the Scots to independence, regardless of his crimes. Perhaps she simply seized an opportunity to act politically in a time where women’s opportunities were limited, or felt it was her turn to look out for the interests of her birth family while the earl of Fife was in captivity and other male members of the kindred dead. Some English chroniclers even claim she harboured romantic feelings towards Bruce, and while of course this cannot ever be proved or disproved, it perhaps says more about mediaeval chroniclers’ inability to imagine a woman taking political action for any reasons other than lust. It is similarly difficult to tell if Isabella had had any contact with the Bruce faction before the murder of Comyn of Badenoch, or if it was a spur of the moment decision. Whatever the case, she seems to have had fast horses readied in advance and was merely waiting for the right moment to take action. Upon hearing of Bruce’s decision to crown himself at Scone, she promptly quit her husband’s house and rode there herself. Intending to take the place of the captive earl of Fife, she claimed the right to fulfil the ancient duty of her house by placing King Robert on his throne.

But by the time Isabella arrived at Scone Abbey, the traditional coronation spot of Scottish kings outside the city of Perth, a coronation had already taken place. On Lady Day (25th March), at a ceremony attended by several earls and the bishops of St Andrews and Glasgow, not to mention the abbot of Scone and many other nobles and clerics, Robert Bruce had been crowned in defiance of the king of England and not two months after having blasphemously murdered the rival claimant in a church. He was by no means secure on his claimed throne, but the coronation was still an impressive display of his political and ecclesiastical support. Nevertheless, the sight of the Countess of Buchan, who must have ridden a considerable way in a very short amount of time and defied her husband to boot, and the importance of tradition- or perhaps simply Isabella’s force of character- seems to have convinced the king and his counsellors to go through with a second coronation. On the 27th of March, Robert was once again proclaimed king of Scots, and satisfied tradition when Isabella of Fife placed him on the throne in the manner of her forefathers, though the stone of Scone and the earl of Fife both remained captive in England.

(The mausoleum on the Mote hill which now stands on top of where the kings of Scots were once crowned- the investiture of Scottish kings, rather like medieval weddings, probably took place outside the abbey on the Mote hill and not inside the church itself)

Unfortunately for Isabella, the start of the new king’s “reign” did not go quite so well as his coronation. An English army was raised not long after the news of John Comyn’s murder and Bruce’s coronation reached the ears of Edward I, and in June Robert’s army was defeated at the Battle of Methven, near Perth. Forced to flee to the Western Isles, Robert decided to send his female family members away to Kildrummy Castle in Aberdeenshire. This castle was at the centre of the earldom of Mar, and King Robert’s first wife had been the earl’s sister so it probably seemed like a strong place in which they would be protected. The queen, Elizabeth de Burgh, and Robert’s daughter from his first marriage Princess Marjorie, along with at least two of the king’s sisters, were sent north in the care of his brother Neil Bruce and John de Strathbogie, the earl of Atholl. The Countess of Buchan, now firmly an adherent of the Bruce cause, was also with them. However not long after they reached Kildrummy, they must have heard that an army under the command of Edward, Prince of Wales, was heading for the castle. Leaving Neil Bruce in charge of the garrison, Atholl conveyed the queen and her ladies further north still, possibly hoping to reach the safety of Orkney and then maybe Norway, where King Robert’s sister was the dowager queen. Kildrummy Castle, meanwhile, held out only a short while before the garrison were betrayed, and Neil Bruce and others were taken south to be hanged.

Hurrying north, the fugitives stopped for shelter in the church of St Duthac at Tain. This small chapel overlooking the windy shores of the Dornoch Firth (the long estuary separating Ross from Sutherland) was a sacred place, holding the shrine of a popular local saint, and its sanctuary extended not just to the chapel but also the surrounding area. As they huddled in its walls, the party might have been forgiven for trusting to the safety of this holy spot and the name of St Duthac. Unfortunately, this trust was to prove horribly misplaced. Uilleam, the Earl of Ross and an adherent of the Balliols whose line Bruce had usurped, was not about to let such a valuable prize sit unmolested in his own territory. Breaking the sanctuary, he had Atholl and the ladies taken prisoner, and sent them south to England. Ross would later be received into King Robert’s peace, but was obliged to make an offering for Atholl’s soul at Tain which would have important implications for the town’s growth. In 1306, however, the captured women and earl faced harsh imprisonment and worse at the hands of an enraged Edward I.

(The ruined chapel where Isabella and many others were captured after the Earl of Ross broke sanctuary.)

(The links at Tain, Ross, looking towards Sutherland over the firth. For context purposes)

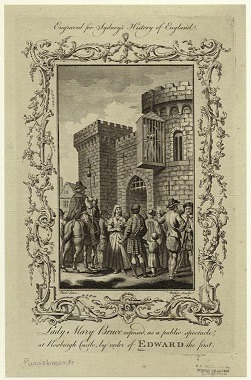

John, Earl of Atholl, like other male supporters of the Bruce claim, was to be executed by the humiliating method of hanging. Members of the English political community’s begged for mercy on his behalf, or at least for a more honourable death since Atholl was related to the English king, but Edward I’s reportedly refused, saying that his rank only meant that the earl would be hanged on a higher gallows. The queen, Elizabeth de Burgh, was the daughter of the Earl of Ulster, an important supporter of Edward, so was given a rather more lenient punishment in the form of house arrest, though she was still often short of funds and occasionally kept in filthy conditions. Christian Bruce, one of the two sisters of Robert I captured at Tain and the wife of Christopher Seton (hanged in August 1306), was likewise placed under house arrest in Sixhills nunnery in Lincolnshire. However her sister Mary Bruce, along with Isabella of Fife, faced a rather worse fate. The chronicle of Guisborough goes so far as to claim that Isabella’s husband the Earl of Buchan called for his wife’s execution, though ultimately this was not to occur. Instead Mary and Isabella were placed in “cages” in the castles of Roxburgh and Berwick respectively. The writer of ‘Flores Historiarum’ (this chronicle gives rather a colourful account of the Scottish situation so is perhaps taken with a pinch of salt) even places the following words in the mouth of Edward I, when deciding on Isabella’s punishment:

“Because she did not smite with the sword, she shall not perish by the sword. But because of the unlawful crowning which she made, let her be kept most fastly in an iron crown, made after the fashion of a little house, whereof let the breadth and length, the height and the depth, be finished in the space of eight feet; and let her be hung up for ever at Berwick under the open sky, that all they who pass may see her and know for what cause she is there.”

It’s a little bit unclear whether these cages were actually suspended outside the castles in full view of the public and open to the elements, as various chroniclers report, or if they were merely extreme security measures taken within the towers of the castles. The official instructions for the construction of Isabella’s cage included orders that the cage be constructed “in one of the turrets” of Berwick, and that she have “the convenience of a decent chamber” and be kept secure, but the imprisonment of the ladies at the Scottish castles Roxburgh and Berwick, rather than securely in England, must have had some symbolic purpose. In any case, conditions were harsh, and the women were not to be allowed to speak to anyone except their guards, and especially not other Scots. They were to remain in these cages for years. Fortunately for the young Marjorie Bruce, similar plans to imprison her in such a cage in the Tower of London were scrapped and she was put under house arrest in another Lincolnshire nunnery. Nevertheless, none of the women would see freedom for at least eight years, when most were released after the Battle of Bannockburn.

This freedom came too late for Isabella however. Living in a cage would have been a harsh life, and even harsher if the cage was actually suspended outdoors. Mary Bruce seems to have been removed from Roxburgh by 1311, being kept a prisoner in Newcastle until Bannockburn, (as Roxburgh was taken by the Scots in 1313, this move was probably due to strategy rather than mercy). Isabella was not similarly moved on that occasion and our last glimpse of her is in April of 1313, by which time the Scots had already made one attempt on the town of Berwick the previous year and had successfully captured Roxburgh and Edinburgh only a few weeks earlier. Then she was finally released from imprisonment at Berwick and placed under house arrest in the keeping of Henry de Beaumont and his wife Alice Comyn, her late husband’s niece and heiress to the earldom of Buchan. She does not appear in any prisoner exchanges post-Bannockburn however, and it is probable that she died not long afterwards (it has been theorised that the conditions of her imprisonment may have hastened her demise but this cannot be proven). In any case, she at least outlived her husband, the Earl of Buchan, who had died in 1308. There was no issue from their marriage and so the claim to the earldom passed to the earl’s nieces, one of whom was married to Henry de Beaumont (and, due to this, de Beaumont would cause quite a bit of trouble for the Bruces in later decades). Nonetheless, though we only have a small amount of information on her Isabella of Fife was clearly a woman with a backbone of steel, defiant and determined to make her mark, and well-deserves her place in the history books.

(A depiction of Mary Bruce in her cage at Roxburgh. Isabella would have been held similarly at Berwick, though I will not swear to the accuracy of these cages in the drawings)

References:

Calendar of Documents relating to Scotland preserved in the English archives

Acts of the Parliament of Scotland

Chronicle of Guisborough

Chronicle of Lanercost

Flores Historiarum

Scalachronica (by Sir Thomas Gray)

Chronica Gentis Scotorum (John of Fordun)

The Brus (John Barbour)

“Widows of War: Edward I and the Women of Scotland during the War of Independence”, by Cynthia J. Neville, in ‘Wife and Widow in Medieval England’, ed. Sue Sheridan Walker

Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland, by G.W.S. Barrow

The Comyns, Alan Young

The Women of the Wars of Independence in Literature and History, R.J. Goldstein

And others.

#isabella macduff#Scottish history#People#British history#women in history#Scotland#Anglo-Scottish Relations#warfare#Wars of Independence#Isabella of Fife Countess of Buchan#Buchan#Comyn family#Fife#Clan MacDuff#John Comyn Earl of Buchan#Robert the Bruce#Edward I#John de Strathbogie Earl of Atholl#Scone Abbey#stone of scone#women of independence#thirteenth century#fourteenth century#nobility#House of Bruce#John Balliol#Tain#Ross#Earl of Ross#William Earl of Ross

81 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sigurd el Poderoso.

Fue un gobernante vikingo, que invadió Escocia y obtuvo la victoria. Su enemigo, Máel Brigte (posiblemente Mormaer de Moray) fue decapitado. Y para poder presumir su triunfo, tuvo la “enorme idea” de amarrar la cabeza del difunto a su silla de montar y mientras cabalgaba, los dientes de la cabeza decapitada fueron raspando su pierna, esa herida se infectó y provocó su muerte en 892.

venganza desde el más allá

0 notes