#monumentalising

Text

Monumentalise - Instructions by Dan Allon

https://www.monumentalise.de/instructions/

0 notes

Text

Paul Revere The Real Story

Does the name Paul Revere ring any bells? This figure from history was made large by Henry Longfellow in a celebrated poem about the American revolution. Written a century after the history it purported to cover it mythologised the events, as art often does. Paul Revere the real story tells a different tale. There is a bronze statue of Paul Revere in Boston outside his house to monumentalise his place in history. Paul Revere did ride through the night to warn colonialists that ”the British were coming.” However, the man himself was much more complex than the few facts remembered by a mythologising history.

Century Vase by Karl L. H. Mueller is licensed under CC-BY 3.0

Paul Revere Tried For Cowardice

Paul Revere was tried for cowardice during the American revolution. He was a silversmith and ran a successful business in the colony of Massachusetts. Revere was a member of the original Boston tea party protest and threw British tea into the harbour. Paul Revere was a colonel in the Massachusetts militia and led an armaments detachment. It was his behaviour during the disastrous Penobscot Bay, Maine expedition that led to the charges of cowardice. The American revolution pitted civilians against trained British troops in many instances and the results were often mixed. Revere is recorded as a difficult man and leader who had trouble getting along with his fellow revolutionaries.

Colonel Revere & The Penobscot Bay Expedition

Successful military expeditions are dependent upon the coordinated actions by the various divisions and detachments within a force. Revere, it appears, was a poor team player and repeatedly let his comrades down over the period of the Penobscot Bay expedition by the Massachusetts militia against the British. It culminated with his refusal to go to the aid of fellow militia members during the retreat from the Royal Navy in their ignominious defeat at Majabigwaduce. It strikes me as particularly interesting that an iconic historical figure, remembered throughout the country, was actually a most unlikely candidate for such honours. Heroes are never the carboard cut-outs that superficial accounts of history make them to be.

The Boston Tea Party, Cheltenham Road by Anthony Vosper is licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.0

Indeed, the regimes and administrations that control the disseminations of history cut and paste the bits they wish to share and those parts they do not. Accounts of history are massaged and manipulated to tell stories that support the current administration. The version of history monumentalised is rarely more than a skeleton of the available facts. The less known the easier it is to tell whatever narrative those in charge wish to spin to the generations that come after. The American revolution, for instance, was not a people’s uprising in the true sense. It did not free slaves, indentured servants, and empower women. It was more a shift from an offshore hierarchical control to the local landed classes. The American revolution was inspired by an unwillingness to pay taxes by those propertied classes and merchants. This archetypal characteristic continues to run through many Americans and the GOP in particular.

©HouseTherapy

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

THE OLD MECHANICS

I’m brittle for certainties. My diary noted ‘headphones’ and ‘RITI!’, but the absence in the foyer erased both concerns. Presuming the removal to be a set-up for Sol’s promotional purposes failed to encourage my reengagement with key busy-day aims, sub-points and their attending stages. My exhausted pay-as-you-go said no to communications immediately furthering my enquiry. I herringbone-laddered around for clues, sulked for the missing patch, and resented this halt to my early entrance. I waited for Sol and for his explanation, eyeballing the image hanging on the door.

Eager skeletons dance the festivities into the kirkyard. One, bespectacled and ribcage proud, maintains encouraging rhythms on a drum. His colleague looks back, flag-waving the human party onward to the place of excavation. Liberated through the first Mechanical Institute’s anatomical education, the crowd converge upon their infamous resurrection opportunity.

My decorative thinking honoured that individual Black Friday lithograph. Abundant editions serialise the sweat of unearthing cadavers or the discoveries of hobby dissection. That print alone monumentalised the anticipation felt by the factory workers turning theory to practice, and treated consequences as trivial.

The homespun penny-press print decorated the studio door since our lease signing. A framed colour copy on permanent display like the martyred body of William Burke. The day our tenancy commenced Sol revised the history for me, illustrating points through the architecture we had committed to create in. ‘The thirty-six balusters lining the right wing correspond with the number of participants who took ownership of bodies that day’, he said, running with my suggestion to symbolically partition the studios into thirty-six ellipses.

*

A Written Ambition

I have a dream that one day I will write a story, or a book of some kind. Writing and books have carried my through difficult times and I want to pay back that service in my own way. I haven't trained for this and I know I need practice. For now I am trying my best to practice this and I plan to update my writing in small chunks here. It isn't edited and it's mostly explorative at this stage.

0 notes

Text

thinking abt literary monuments etc and tbh the ultimate best most successful Tomb Made Of Words is like. the word mausoleum. like artemisia ii monumentalised mausolus so well that a large proportion of All Tombs Ever got named after his One Very Genre-Defining Tomb and now little piece of his ghost is stuck inside of language itself

#AND YET like how many people actually know that a) mausoleums in general are named after thee mausoleum of halicarnassus#and b) the mausoleum of halicarnassus was named after king mausolus of caria. like his ghost is SO fossilised in the language that most of#the time you dont even see it! most people do not register that there is a name in there!#also it's a v efficient language fossil which is cool. like one ghost per one word gets him around quite speedily and nicely#a lock against oblivion#beeps

372 notes

·

View notes

Text

That human patronage and divine patronage operate as reflections of each other can be seen in the existence of the associations of the Graeco-Roman era. Evidence of associations, especially in the form of the inscriptions they so typically left behind, attests to a higher degree of heterogeneity and variety than previously thought. Associations were united by a something held in common. This was often a trade (e.g., bakers, merchants, purple dyers, wood cutters, etc.), though equally often there were associations of mixed or related trades (clothes washers, leather workers, linen producers, purple dyers, etc.). Associations were also formed around familial networks, and ethnicity or geographic location. Variety in the rationale behind the creation of associations is matched by variety also in their social composition. [...] And finally, there was variety in their reasons for gathering, whether religious, funerary, or social. The most significant contribution of Harland in this regard is his observation that even within all this variety of rationales, social composition, and purpose, the activities of the associations cannot be divorced from concerns of religion or patronage, and these would often be inseparable. Many inscriptions from associations acknowledge both human and divine patrons and benefactors. For example, throughout his work, Harland illustrates the extent to which association activities, whether feasting privately or publicly "monumentalising," were concerned with honouring their human and divine patrons (the latter, of course, is religion). Likewise, according to Horsley, IKyme 30 (= NewDocs 1:2) was established by a thiasos that appears to have been named after its human founder Menekleides, but it also appears to invoke the name of Dionysus, potentially its patron deity. In addition to naming patron deities, as well as naming one's association after a god, which are obvious forms of patronal acknowledgement, one might claim that an inscription was done at the command of the god. So, for example, the priest Apollonios claims that he "composed this record in accordance with the ordinance of God. The gods were approached as patrons and benefactors; as much is apparent wherever we see the language of benefactions used of humans used also of the gods. To cite only one example of a great many, Aelius Aristides frequently refers to the εύεργεσία of Asclepius (Sacred Tales 2.294.8; 4.323.14; 4.337.11; Asclepius 44.2; Speech for Asclepius 39.19) and refers to the god with the title Ευεργέτη (Sacred Tales 4.329.16). Like elite humans, the gods were believed to have the ability to bestow certain valued and limited goods upon those who honoured them. And honouring the gods was key, for even Euripides was compelled to acknowledge that the gods took great joy (τέρπεται) in the same honour (τιμώμενος) as did men (Bacchae 319-321).

- Zeba A. Crook, Reconceptualising Conversion: Patronage, Loyalty, and Conversion in the Religions of the Ancient Mediterranean, De Gruyter, 2004, pp. 77-78.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

monumentalisation makes you immortal by Setting You In Stone (hohoho) but metamorphosis! makes you immortal by changing you! okay!

#i also have adjacent alexander and xerxes troy visit thots but now is the time for sallust and later is the time for That#ait#horace 2.20 vs 3.30............fight!

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

As one advances in life, one realises more and more that the majority of men — and of women — are incapable of any other effort than that strictly imposed on them as a reaction to external compulsion. And for that reason, the few individuals we have come across who are capable of a spontaneous and joyous effort stand out isolated, monumentalised, so to speak, in our experience. These are the select men, the nobles, the only ones who are active and not merely reactive, for whom life is a perpetual striving, an incessant course of training. Training = askesis. These are the ascetics.

José Ortega y Gasset

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Larry Fink

Some notes I took from Fink's book in the Aperture photography workshop series:

Most successful pictures encapsulate a story within one frame that works on many levels

Larry Fink, American Legion Dance, 1978.

Photography lends itself to layering

Has the ability to bring together incongruences

Building the box

Larry Fink, Dave Burrell on Archie Sheeps Piano, 1966.

Establish a working understanding of the “rules” of stories and juxtaposition

e.g. leading the viewer’s eye through diagonals coming together

Edges are always important to a picture

Can use the corner of the frame to point inward to the conceptual centre of a photo

Larry Fink, Blue Horizon, 1990.

Covering the table has less tension

becomes more two dimensional rather than sculptural

“Art, with a capital “A,” happens when you enter a space and can see and feel the edges but not be closed by them”

Larry Fink, Portugal, July, 1996.

The story unfolds as a question

If you complete the composition, it is stagnant

If the picture doesn’t have energy, it’s because perfection was its goal

Too symmetrical or overwrought by constipated intellectuality

Atmosphere is different than space

Larry Fink, Social Graces: Jean Sabatine’s Sixtieth Birthday, May 1992

Atmosphere is charged space

Fills the setting with feeling, mental and physical

Worth emphasising factors that create atmosphere

Dust, wind, rain, saturating heat of the sun

All about intensification

A photograph is just a surface

Trying to break through the barrier that photography gives to us

Two dimensional flat dictum of document

Trying to move forward and into it, so that the picture somehow speaks of what it means to be three dimensional, sensually, spiritually, and psychologically

From all things to your thing

Stephen Shore: photography is an analytical art

Not like painting, writing or music

In painting, you start with a blank canvas, with nothing

Photography starts with everything

Your palette is all things, so you can reduce it to your thing

“What in the miasma of all things in front of you that moves you to photograph, to monumentalise, to trivialise?”

The act of selection

Source:

Larry Fink, Larry Fink on Composition and Improvisation, (New York, N.Y. : Aperture, 2014).

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Away with all your monuments - Thoughts on Holocaust Memorial Day from 2020

Away with all your monuments. Yet today, again, we are compelled to monumentalise. It is the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. Little liberation it was: of the 1.3 million Jews sent there, over a million were murdered. The resistance failed. What does the compulsion to monumentalise feel like? Screens everywhere littered with stories of quiet bravery in the face of fascism. Faith in the promise that history could have been otherwise. Tales of fortitude picked up like golden tickets by all those officials, who happily assure us that should fascism ever threaten again they would be on the right side. And what were those who died like? Some were good people, others bad. Some were communists, some not. Some were Zionists, others not. Some resisted. Some collaborated. Most were broken before death. And resistance often meant a quicker death too. Ultimately it made little difference, because they alike were murdered. And although many brave people across Europe risked everything to save Jews, to rescue them and smuggle them across borders, many others did nothing.

I'm scared by these stories, that deal in separating good from bad, the resistor from the collaborator. The horror of Auschwitz is of indifference. Among the victims of the Holocaust the compulsion to resist was the very same as the compulsion to collaborate. And if the lesson that is learned is that every Kapo deserved his own execution, it is no lesson at all. Today I am remembering those who, as well as resisting, did not resist, could not resist, resigned, gave in, handed over their brothers and sisters, parents, children, and comrades to fascists and were nonetheless murdered. It is a grizzly thought but one we cannot do without. Today I am remembering those who survived and who nonetheless were far from angels, whose lives were blighted and who continued to blight the lives of others. Because to become victims of fascism did not make them good either. This is not to say that those who brought the message of what happened, that those who were spared and fought to stop us forgetting, were no good.

The compulsion to monumentalise means that Auschwitz has become some fatal star of morality. The industrialised murder of Jews, of Roma, of people with disabilities, of gay people, of communists, has become an opportunity for the great and the good to distance themselves from evil. It is feel good and blindness. It has become a festival of comfort and of peace. Peace we need and comfort we do not. In making sacred the victims it remakes them into sacrifices, whether or not they were spared.

I think of the words of the great philosopher Gillian Rose, who talks about “the sentimentality of the ultimate predator” in thinking about the film Schindler’s List. She wrote, “Schindlers List betrays the crisis of ambiguity in characterisation, mythologisation and identification, because of its anxiety that our sentimentality be left intact. It leaves us at the beginning of the day, in a Fascist security of our own unreflected predation piously joining the survivors putting stones on Schindler’s grave in Israel. It should leave us unsafe, but with the remains of the day. To have that experience, we would have to confront our own fascism.” It is one of the bravest thoughts.

Today fascism again threatens. It threatens in the middle of our culture of sacralised victims. The fascism of our time has more than it would like to admit in common with the compulsion to monumentalise. It stands opposite and as mirror image of the saintly victim, as the accused. It says, “if the victim does not need to question whether they are good or bad, if their victimhood is sovereign, then I have no need to take their accusation seriously, and have no need to confront my own fascism.” But we do not need our victims to be good for the demand for justice to be righteous. Indeed justice can illuminate the world only in the redemption of those who were not already good, not already saints, not already sacralised by what was done to them. And justice does not recognise the goodness of those who were compelled to resist, as others failed. So today I resist as I affix my memory to those who did not resist. Away with all your monuments. Only then can we confront fascism, without prematurely celebrating (already 75 years too late) our anti-fascism.

(I put this up, now a year later, because I haven’t had time to write something new this year.)

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Oak of Honor (Statement)

I chose to study and make record of the Oak of Honor which is an oak tree in One Tree Hill, South East London. The tree is a tribute and a monument to a previous tree which existed in the park, upon which Queen Elizabeth I was supposed to have rested as she was journeying into London.

The current tree stands at the top of a hill and is over a hundred years old. It is the latest but likely not the last tree to monumentalise a relatively insignificant moment in history. However insignificant, dendrophiles over the last few centuries have dedicated their time, effort and other resources to maintaining the lineage of the original Oak of Honor.

This diptych image investigates the complexion, scale and texture of the Oak of Honor. It hopes to encourage an imagination of what came before and what may follow.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Circularity of Time

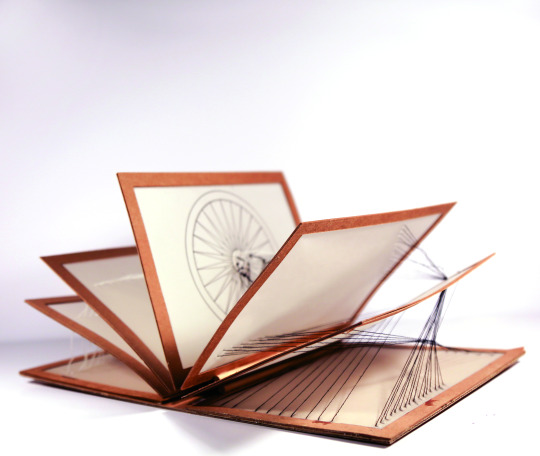

The Infinitesimal and The Monumental Duration Spin & Weave: An Exploration of the Themes of Nationalism, Social Fabric & the Circularity of Time ‘

- interview with architect and interior designer Aarushi Kalra.

AM - Could you give a bit of context about the Gandhi project of using the hand spinning of cotton as an instrument to raise awareness of the independence from England?

AK ‘ In 1909, in an anti-colonial move towards Indian self- sufficiency, against the British, Gandhi decided to revive a craft many saw as already dead: the hand- spinning of cotton into thread, using the Charkha - the Spinning Wheel of India. He saw spinning as an economic and political activity that could bring together the diverse population of the country and was a defining symbol in the struggle against the British rule. It was a symbolic call towards a self- sufficient India, highlighting the ‘Swadeshi Movement’ - a part of the Indian independence movement that contributed to the development of Indian nationalism. This movement aimed to make Indians rediscover their sovereignty and strengthen their pride in Indian heritage, while also disengaging with the imposed British norms and boycotting all British goods. Gandhi claimed that spinning thread in the traditional manner could create the basis for economic independence and the possibility of survival for India’s impoverished rural multitudes. His choice to stand in solidarity with the poor of the country, while East India company was systematically exploiting them became a powerful symbol that then became the face of the movement and urged his more privileged followers to copy his example, and discard, or even burn, their European-style clothing, proudly returning to their ancient, precolonial culture. This simple act of spinning pierced through the varied Indian community, uniting all classes, caste, gender and creed into one cause and fabric. However, today it seems to be reduced to a static symbol; as a part of history and as a part of the India national flag. It lost its efficacy once its dynamic performance ceased to anchor a political movement. We retain now only the echo of its circular rhythm.

AM - How did you come up with this idea of exploring the idea of the spinning wheel as a tool for reflection, almost crafting through time?

Having grown up in India, Gandhi’s presence is all around us. Not necessarily as the figure we have studied throughout history, but as an integral subconscious symbol in day to day life – on the currency notes, names of the streets, etc. Moving out of India, for the first time, to pursue my post-graduation in London made me acutely aware of of my heritage. Moreover, at the time the news was flooded with updates on Brexit, the election of Donald Trump as the president, the building of the wall between US and Mexico and more news of the same nature from Russia, India etc. When we were presented with the brief that asked us to expose a political space of production that spanned the ‘infinitesimal to the monumental’, the symbol of the spinning wheel almost instantly came to my mind, as it was a simple machine and a simple activity that united the entire nation. I wondered how today the term nationalism has been broken and twisted to divide rather than unite. And as an extension of this thought, can it be argued that the spinning wheel that once spun the fabric of unity now spins the fabric of division? What once symbolized inclusivity now takes pride in furthering exclusivity? And that for me was the starting of “Spin & Weave”- a project that explores the theme of Nationalism, Social Fabric & the Circularity of Time. I was interested in investigating how a symbol, so intrinsically part of my own culture, can be revived to interact with present-day political, global occurrences. How a symbol of unity, can now represent boundaries? Based on my new insight into nationalism, this project was a way to explore whether this symbol out of its original context remains the same static image while showcasing the change of ideologies, or does it take on a new form and new meanings? The end piece was envisioned as a scaled model of an experiential installation which showed the two sides of the wheel. One, where a multitude of threads converge at its centre, representative of the people that would once come together to unite, while the other showed the same threads diverging into multiple directions disrupting the spectator's path and field of vision. To be able to traverse this space you might have to go over the strings or under them, cut them, tie them up, loosen them; but you have to make an effort to navigate this stretch. At the centre of all, is this spinning wheel, entangled in the boundaries it continues to weave. A wheel that cannot spin any longer but continues to monumentalise the act of spinning.

AM - Did you consider/imagined the meditative properties of spinning when you created your project?

“Take to spinning. The music of the wheel will be as balm to your soul. I believe that the yarn we spin is capable of mending the broken warp and weft of our life…” – Mahatma Gandhi

The process of spinning yarn is inherently meditative. It’s not something I originally considered at the beginning; however, it was hard to ignore it as I sat for days threading yarn, creating scaled models of the final output. There is a rhythmic cadence to it. It is monotonous, repetitive, but just as when you’re meditating it allows you lose yourself into it. It is a wonderful process to instil patience, stability and peace in an individual. Which in my belief had been of utmost importance at a time when the people of India needed to be level headed and find the strength to stand against the colonial rule. One of my biggest takeaways from this project was the lesson of patience and discernment. I learnt the importance of each individual’s effort in fuelling a collective power; which during the colonial time, created this beautiful, peaceful and unified fabric of my country.

AM - Do you think that there is a connection between crafting/identity and narration?

AK - In terms of physical and tangible materials, for sure. Every region, city and village boast of its own handmade traditions and skills, the ancestral knowledge embedded deeply in our cultures. The geographical location, environmental factors, and the available local materials initiated certain ancient practices that slowly got imbibed within the fabric of the place, which inherently defines its identity and a specific cultural viewpoint. Local materials are used to tell local stories in a particular cultural context. The way of using them only further adds to that. Anything that becomes tangible has an identity, and everything that has an identity has a narrative. Crafts are a way of giving shape to new forms, building a whole new database of identities and narratives in design. It enables the piece to embody the history, culture, socio economic political expression and the various personal stories and aspirations of the designers/ craftsmen. Art and design by nature are a form of storytelling. In no two cities or zones can the same art or craft be practiced in the same way. It is always adapted, and with this adaptation the story changes immensely across boundaries. This is the beauty of context in art, design and narratives. Any small change brought to any one aspect has a ripple effect on all the others, leading to a completely new personality of the base identity. An example of this is how from Japan's kimonos to Scottish tartan, and from Uzbekistani Suzani to Gandhi's push for Indian khadi, the culture of the world is woven, quite literally, into local fabrics. Though the machinery and techniques have been similar, yet throughout human history one look at a man’s clothing could tell you more than his words: his social standing, wealth, class, military rank and more. Historically cloth was unique to its region and country, sometimes literally tying in elements of the land and the people that live there. Even today in a globalized society where one can swipe through countries in no time, all groups of people have secrets hidden in patterns, dyes and fabrics that are waiting to be explored. - How do you think that we could share ancestral forms of knowledge without commodifying them? This is a very difficult conversation to have in the world today. There is a very fine balance between conserving and commodifying. We have lost so many art-forms simply because we haven’t been comfortable in the idea of commodifying them. There are various ways to share knowledge but as soon as they become quantifiable, it becomes a commodity. It almost seems to me as though we might need to change the way we understand commodities and become more mindful of the exchange of these. As a designer I believe in sharing ideas and culture, and I see no harm in others doing the same even if it comes at a certain cost. One can’t ignore the fact that one needs an income to enable these storytellers to run their own lives while comfortably dedicating their lives to the craft. This constant debate between conserving and commodifying, impacts the simplicity and the purity of exchanging stories and emotions through craft.

AM - How do you deal with the idea of orality associated with tradition? For instance, in African countries, many times traditions are never recorded, so, we lose them, but on the other hand that is how they evolve naturally... so, if we record them, we somehow kill them in the sense that they no longer transform/evolve...

AK - India has a very rich oral tradition. Take Indian Classical Music for example, where the original tradition of imparting knowledge over thousands of years was through recital with a minimal use of the written word. Recorded and written material developed, but only as a key to absolute basics. Beyond that, Indian classical music is still almost entirely improvised, improvisations based on these certain written ground rules. The same is true for most of our forms of Art, Dance and Scriptures. The oral tradition is in a sense trapped within the confines of a culture’s collective value system. It is first and foremost a group activity, and reinforces bonds within the culture, but it also depends on that group’s willingness to further keep the art of practicing and sharing alive. Writing, on the other hand, is an individual pursuit. Writing transmits ideas from other cultures that reside outside the local sphere and allows the individuals to interpret those ideas for themselves. Written or documented references not only cater to a wider audience, but also to a more distant generation; enabling them to enjoy, learn and reinterpret past stories, leading to a natural evolution that keeps these traditions relevant. The only drawback being the loss of understanding, guidance and the radicalizing of the written knowledge. I feel, this documentation must allow the artist to freely interpret and improvise this knowledge. The need of the hour today is also to learn the subtle language of symbolism and essence, not only to keep the traditions and rich stories alive as they were, but also to strengthen our understanding of each other’s thought processes and maintain a better harmony.

AM - Do you think that it would be possible to create a project that would connect young artists with old craft studios to create sustainable projects in India? What is missing in terms of business channels that could render these local projects visible worldwide?

AK - Every craft form is based on shared information that is continuously evolving. Formulating more and more collaborations where old traditions and skillsets are funnelled into the younger artists, along with a freedom to reinterpret them through their own experience and insight, might help bring these traditions to new light. Take for example how a khadi wheel works - the wheel is a form of analogue technology and weaving is a cultural idea. The practice pushes the technology and cultural idea embedded in it forward. Now, for a ‘young’ artist, some of these technologies or cultural practices may present a space of possibilities that may connect to their own practice; or a possibility where they can combine it in with the latest technologies - retaining its roots but giving the product a more global and widely accepted appeal. This may perhaps be a way to find a common ground and explore further. To a certain extent this has already started to happen. However what concerns me is that in the collaborative effort between the designer and the artisan, the designer gets all the credit and possibly the profit while the artisan has gained nothing more than what they always had. The need of the hour is to evolve the stature of the craft and the craftsman enough to give the artisans an incentive to believe in what they do, and for the younger generation to be willing to learn and continue this process. Now as far as contemporising the traditional crafts go, I believe it requires work in two divergent directions. One is that art forms and crafts become a natural part of life again, as they once were. An extremely simple example is how in parts of the country and world over plastic plates are being replaced by banana leaves. This was a common traditional way of eating in southern parts of India, and now again there are people working on spreading it across the country, not as a tradition or luxury, but as an absolute basic awareness. On the flipside, craft must also be innovated and made a part of high-end design. One that celebrates the craftmanship for its glory, and adds an aspirational ramp value to these ancient crafts. An example of that is furniture designers today are reviving and reinventing the dying craft of making utensils and artefacts by hammering brass—traditionally practised by a community of Assamese artisans, to create high end, contemporary and innovative products that are highly global in their appeal while the manufacturing techniques belong to the Indian handicrafts’ tradition of the country. Government, innovators, investors, crafts organisations and designers need to come together and work closely with the craftspeople; listen to their voices, build on their strengths, think out of the box and possibly create a regulatory body that connects various craftsmen to designers all over the world, almost like an open source. However, it needs to have its own regulations in place to ensure that artisans and craftsmen are not exploited, and can also gain from the exposure and the innovation, giving them a reason to believe in the craft they have spent their lives mastering, again.

AM - Ana Mendes

AK - Aarushi Kalra

Aarushi Kalra is an architect and an interior designer, recently graduated from the MA Interior Design at Royal College of Art. Currently she is in the process of setting up her own design wing based in New Delhi, India, by the name of I'mX - that aims to work fluidly between multiple disciplines. One that challenges and immerses viewers into provocative, layered and experimental environments.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Covid and the Improv Circuit

A few days ago, I posted a couple of blogs about one of our free improv national treasures, Evan Parker, in relation to views he expressed to Wire writers Tony Herrington and Daniel Spicer, and to Jazzwise’s Ken Waxman, in the spring and summer of this year. After some reflection, I soon deleted them, fearing that they might be misinterpreted, given the current toxicity that can soon surround discussions on Covid 19, the pandemic, and the measures that are being put in place to treat and contain them. I would direct interested readers to these interviews themselves, but want to write a short piece about Mr. Parker, and on whether an artist’s views can alter our perceptions of their work (basically, they should’t, but inevitably do?)

I got my sorry ass to only 4 gigs after March in 2020 (i.e. subsequent to the first lock down), and 5 in 2021, events that featured some of the cream of our UK free improvisers, in the absence of visiting American and European talent. So I had healthy, but somewhat homeopathic, doses of the likes of John Butcher, Eddie Prevost, John Edwards, Mark Sanders, N.O. Moore and Dominic Lash, These gigs were wonderfully refreshing in the middle of these most strange 21 months of relative isolation and social strictures, but one name was conspicuous in its non-appearance, that of Evan Parker, the musician that I have undoubtedly seen and heard in a live situation more than any other (well over 100 performances, I would estimate; no other musician apart from John Edwards comes even close). Even the saxophonist’s longstanding residency at The Vortex now seems to be a thing of the past, and given the fact that he has been an integral part of the scene since 1966, his disappearance is surely hugely significant, and seems to herald an ‘end of an era’ moment? I do increasingly feel that we will look back at the (just to give it a name and time) ‘2010-20 Cafe Oto period’ as a ‘golden age’, to be put alongside those of The Little Theatre Club (1966-74) and the London Musicians Collective Gloucester Avenue residency (1978-88). But perhaps slightly better attended and more contemporaneously celebrated?

I have been criticised at times for my monumentalising of particular ‘notional’ periods of English free improvisation, but Evan Parker’s loud absence does seem to me to be of notable significance, representing a caesura that correlates with the onset and continuation of the pandemic. Without being too fanciful and/or morbid, perhaps a comparison to the loss of Coltrane in 1967 might be some sort of equivalence, in terms of impact on a particular music culture? Having read Parker’s interviews, I do wonder if his stance(s) on a variety of related issues (the European Union, the virus, lock down, vaccinations) may have influenced his willingness to perform in such a ‘hostile environment’ (hostile to who and to what is the key question here, however). Has he, in effect, retired? Is he unwell? And, to add a more abstract question - have his opinions affected the way I (and, by extension, others) listen to his music? The answer is that I don’t really know, except to say that his contribution to the music has been so massive and consequential, that this is not a flippant or asinine question to be asking. We live in divided and polarised times, as so many hacks keep on telling us, and it does seem significant that the stances of public figures (and Evan Parker IS one of these, however marginal), rightly or wrongly, have become nodal points of conflict, and can lead to the unpleasantness that follows - for just one current example, just look at the case of the tennis maestro Novak Djokovic, which has occasioned a nigh on international incident. “I just play (tennis) man!” (a version of a sarcastically-meant quote from the late Parker nemesis, Derek Bailey) would be a neat get out clause, but somehow I think it’s gonna be more complicated than this in the long term, and I just hope that we will remember the immense amount of fantastic music that Evan Parker has given us, and that he will, that is if he wants to, return to enrich our rather arid and denuded live performance arena.

0 notes

Text

Nostalgia: objects as analogues

Nostalgia has become a sickness that has reached fever point. Although technological innovation strives forward, we continue to use the frames of these screens to delve into the past, into the monochrome glory of a 1950’s TV. We obsess over collecting and recollecting in a never-ending cycle that glorifies the everyday, after which point there exist more memory boxes in our homes than anything else. We superficially fixate on artefacts that takes us back to specific moments in which life was good. The artefact itself may be banal, but we monumentalise the association and memory we have with it.

However, behind every carefully curated Cabinet of Curiosities now are layers of history that are purposefully cropped out, until eventually, the real stories are forgotten, and the past is reduced to a mere shard of glass. Our Instagram feeds provide, literally and metaphorically, a black-and-white version of the good old days, from which we only remember the pleasant moments as a way of finding comfort through familiarity. This mode of selective amnesia erases the true nuances of history and represents our desperation to escape not only the future, but also the present.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Norman Foster, The Reichstag Graffiti, Jovis, 2003

“Architect Norman Foster’s (et al. 2003) book ‘The Reichstag Graffiti’ also addresses the questions of German collective memory. In essays, archival documents, exquisitely detailed drawings and stunning close-up photographs by Reinhard Görner, the book documents what Foster terms “the process of revelation” and the procedure and method that for him reflected “a clear ethos of articulating [the] new intentions with the surviving historical fabric”. Here, history served as a design tool. First, it presented a unique aesthetic opportunity when during the asbestos removal from the earlier reconstruction of the building the palimpsest of older surfaces and the powerful victorious Soviet graffiti were revealed. Second, a forceful historical rhetoric was employed to counter the ensuing debate over the wisdom and political implications of the graffiti restoration or removal. Foster’s vision for retaining the marks and incorporating them into the new interior was eventually approved and carried out to completion. Now, history served as an instrument of justification: a powerfully articulated argument backing up the decision of restoration and creating a protective mechanism to guarantee that critical voices stay at bay. The fierce dispute over the symbolism of the Soviet graffiti on the walls of the German parliament was not over at the time the book ‘The Reichstag Graffiti’ was published. It is an important book, claims Foster, because it attests to the enduring power of graffiti. Indeed it is and indeed it does, although my interpretation may carry Foster’s intentions further than he would have expected, as I believe, any work’s power can only benefit from serious scrutiny. The restored Reichstag features fragments of the original walls embedded in the new structure. The walls showcase the outlined palimpsests of scribbled Cyrillic letters. No need for golden frames (a suggestion made by a Russian artist, Iliya Khabakov, which was not approved by the Bundestag’s Arts Committee). The kind of framing that Foster employs is far more powerful. He uses the material historical record itself to outline graffiti pieces: fragments of the older walls act as shields signalling territorial boundaries. The Bundestag commenced regular parliamentary sessions in the Reichstag in 1999 but the debate over restored graffiti continued into the next decade, and it is not a mere domestic dispute. The Russian ambassador in 2001 warned that erasing the graffiti would endanger the process of reconciliation between “the two peoples” particularly against the background of the anniversary of the German attack on his country (ibid., 36). Graffiti, in this dispute became a symbol of a unilateral historical truth: a re-inscribing of the Yalta agreement that interprets the history of the Second World War as an honorable conflict between two giants, with no mention of the consequences for the political and human bodies between them. The restoration monumentalises the inscriptions, affording them the kind of attention that only the most precious frescoes or archaeological artifacts are typically granted (ibid., 33). It also remakes the wall writing fragments into aesthetic statements, exquisite visual fields composed into a ‘correct’ and agreed upon visual narrative of history. The book canonises graffiti: it reveres the process of restoration and its product, as a significant work of art. The book’s pages linger over the annotated reproductions of the crude scrawls preserved in carefully arranged compositions within the planes of the building interior walls. The images in the volume highlight the act(s) of preservation as/(and) framing: the palimpsest of historical traces is composed of outlined elements arranged to indicate the layers of “history” through a play of surfaces and the juxtaposition of the “spontaneity” of the lines of graffiti and the controlled crispness of the older traces against the building’s modern surfaces. The elevation drawings of the positions and details of the carefully delineated elements highlight the beauty of this visual choreography; the skill of the architect behind this composition and its rendering. The exotic shapes of the Cyrillic letters, which in the linguistic context of contemporary Berlin legible to most only at a symbolic level, and the crudeness of their lines evoke the magical powers of primitive surface markings. The specific historical symbolism has little to do with this. The “individual mark” is used merely for its emotional content, its power to evoke spontaneity that breaks the rigidity of the largely homogeneous architectural planes. If the walls of Reichstag speak of any conflict, it is the conflict between the emotional and historical content of the letters and the image they form once they are carefully composed, first on the walls and further on the pages of the book, thereby confirming the project’s status as a work of art (ibid., 36). What is monumentalised here is a designer’s (artist’s) hand, the artful act of memorialization itself. The book remains the only place in which the restored writing has truly public access. The actual spaces that contain restored graffiti are not open to the elements, be they the stresses of social discourse or environmental weathering, nor are they easily accessible to the general public. Thus, this loaded public writing is removed from the public realm, set within the frame of “historical evidence”, and further (dis)placed into the volume that presents it for specifically guided viewing. The printed volume is the only place where the images can be closely read, that is, where the German speaking public, whose history is exposed in this “living museum” can decipher the Cyrillic writing. The writing itself is difficult to examine in situ, so Foster’s book is a precious tool providing access to his project. It forms a separate site of display, and in so doing, it creates its own defensive wall. It monumentalises the project of restoration in what is effectively a catalogue of Foster’s artwork. But Foster is not a neutral artistic force here; his project is the British offering towards the re-building of unified Berlin (each of the four Allied powers was represented by a work of art and Foster’s design was the British contribution. Since the graffiti has become part of an artwork, it is integral to the design and as such protected by Foster’s artistic copyright. Now, “[t]o clean the walls would be the equivalent of painting over part of the canvas” ). Yet to justify the design choice, the presented history of the Second World War “paints over” the role the Soviets played in building Hitler’s power and in subjugating Europe after the victory of 1945. One just needs to reflect on the names of places along the “victorious” route to Berlin (Grozny, Kiev, Lviv, Warsaw). The War chronology presented in the book is silent on the relationship between the “two peoples” in the time between September 1939 and February 1941 (ibid., 123). Equating the fascist representation of Bolsheviks with those of Jews in 1937 exhibitions housed in the Reichstag and presenting a chronology of the war in a fast-forward mode from 1937 to 1945 suggests a continuity of Soviet “struggle” with fascism and relegates the tragedy of the millions located in the territories East of the Reichstag to outside of the viewing frame. In fact, this is very much in line, with Soviet war and post-war propaganda. Wars are composed of battles over the right to write history on the walls of cities. Graffiti that covered the sandblock stones of the Reichstag, began as spontaneous acts commemorating fallen comrades, expressing pride or vengeance, marking a triumphant arrival at the end of the arduous journey. But it soon formed a collective theatre. A staged event of propaganda that folded an individual soldier into the grand performance of marking: the Reichstag was a ‘guest book’ set out for commentary on the “final” act of the war, and (again) “the venue for propaganda exhibitions” (ibid., 8). Delegations from various Soviet cities would make ritual visits, signing the historical ‘pages’ with their marked presence (ibid., 27). Crowds would arrive to partake in this ritual of signing. The officers scribbled (in blue crayons) along the more accessible surfaces; more daring writers, soldiers armed with charcoal, climbed the walls to those spots that would ensure the high visibility of their signatures (ibid., 24). The ‘writers’ knew that for graffiti, ‘getting [high] up’ was crucial. The Reichstag wall writing had attained the symbol of a relic, with graffiti-covered stones transposed and on display at the National Army Museum in Moscow as “moving testaments to Soviet victory” (ibid., 28). It became a powerful image of triumph: just like Yevgeny Khaldei’s photograph of the Red flag over the Reichstag (a staged, re-enacted scene to create a propaganda image). Graffiti was even more powerful as a performance aimed at the domestic audience: while there could be only one flag over the Reichstag, the writing could be unlimited: it was the people’s symbol of victory. An ordinary soldier could make his own mark and his triumph could be personalised (ibid., 27). The writing on the walls of defeated Berlin spoke most eloquently through its crude lettering. No big words describing the city’s trauma, its horror, its stench, its ruins, its eerie silence or the cheering after the battle. There was no need to verbalise the obvious: the ruined city spoke expressively of its pain and defeat, without any alphabetic transcription. The writing on its walls was the voice of the victors. Not a subversive political act of rebellion but a staged happening, a proclamation of pride in the Soviet Nation (and its Great Leader) who defeated the Germans. ‘The Reichstag Graffiti’ book is a rhetorically powerful but historically problematic artist’s statement. While evoking the ethos of the restoration of collective memory and the argument for the creation of a “living museum” of German history, it uses fragments of history to justify design choices. The images of the markings, and the discourse that frames them, construct a simplified argument that frames history. The contentious question of the appropriateness of this restoration project is framed into the opposing arguments of the “open minded pro-graffiti group” and the dark forces of the ultra right wing anti-graffiti lobby (ibid., 35). The advocates of the removal of the graffiti are likened to the Holocaust deniers, and the book ends with powerful words by a Jewish teacher calling for the necessity of examining memories. The victorious Stalinist rhetoric is thus propped up by the trauma of the Holocaust. The Second World War is shown as a struggle between two mighty enemies, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany and the Holocaust is conveniently factored in as a rhetorical tool positioned on par with the Bolshevik struggle. Soviet historical accounts from the 1960s are validated as historical documents. Quoted at length they set the rhythm for the book’s narrative, and they seem to be given as much power as the invocation of the restorative forces of memory conveyed through the words of a Jewish teacher, Baal Shem Tov, that close the book (see for example quotations marking each of the sections of the book/clusters of graffiti inscriptions ibid., 38, 57, 70, 85, 121). Foster underscores the power of graffiti as he marvels over “how the scarred and graffiti-marked fabric of the Reichstag records the building’s troubled past, and how these scars, once revealed, could be preserved, allowing the building to become ‘a living museum of German history’” (ibid., 17). Indeed, graffiti contains in its emotional gesture the imprint of the past, an individual voice, here validated even further by a meticulous restoration that renders the fragment precious. The history that is contained in these markings, however, is far too complex for the book’s myopic frame. The marks themselves are far more eloquent. Graffiti’s political power is always context-bound, locally nuanced and the book unwittingly submits to the demonstrative (deictic) power of graffiti marking. Foster is right on his account of graffiti: the Reichstag writing does speak eloquently of the local condition. But what he misses is that it attests both to the victory and the defeat. The presentation of history in the book, elevating the historical import of the restorative gesture and deflecting possible criticism, is in itself a defeat of historical and ethical discernment. How do these images published in the exquisite catalogue, inform the relationship between design and graffiti? Graffiti is used here as a design tool and its historical significance becomes its copyright. Here, a mark that is inherently specific validates a generic image of a selected historic memory. Or no longer historic, perhaps, but art historical, since the album privileges the aesthetics of the image of the mark and the composition of the page that displays it. In this art project, the “tragedies and traumas of the past” are used as instruments for legitimating an aesthetic gesture of fitting graffiti scrawls into the compositional plane of the “architectural palimpsest.”

- Ella Chmielewska, 'Writing on the ruins, or graffiti as a design gesture', from: The wall and the city / Il muro e la città / Le mur et la ville

background: https://www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/394562/e9b7fac699d80e1d5e2ec78813d15e62/flyer_graffiti-data.pdf

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Catenary Arch of Triumph

Monumental Error

To find perfection in nature is to be able to replicate god, a decision that is both arbitrary and a necessity in order to elevate the importance of architecture; to inform what is at stake when reality is confronted with the spectacle and not the permanence of the spectacular. It is as though the impermanence of art is at odds with the historical reference system of architecture; flummoxed by the insanity that perpetuates it; guarded by the words that carry its name. If silence is permitted to speak then we can conclude that we occupy a line of historical errors that are monumentalised by architects to fan the flames of our societal divide that the art’s is convinced it can appease. But to overcome death is only important once you can give us all an equal meaning for life.

0 notes

Text

"Tadao Ando's equivalent of what a dog does to a lamppost"

The redesign of Paris' Bourse de Commerce in Paris by architect Tadao Ando is a "complete disaster" of sterile concrete that turns the building into a monument to French colonial violence, says Aaron Betsky.

A billionaire and an architect walked into a bar. "What will you have?" the bartender asked. "Something to forget the evil origins of capitalism," the billionaire replied. "I need something to make me feel big and important," said the architect.

"I have the perfect thing for you," the bartender responded; "A concrete martini. It is round, dry, aseptic, and big enough to make you feel like you own the world."

"Make mine a double," the architect responded with enthusiasm.

That is how I imagine the origin story of the Pinault Collection's new venue in the Bourse, Paris' former stock exchange. It features a concrete ring whose functions, such as they are, appears to be to support two spindly staircases and some air outlets.

But its real nature seems to be architect Tadao Ando's equivalent of what a dog does to a lamppost, it is an example of money trying to transform itself into art and architecture at a gigantic scale. As a display space for a pretty good collection of contemporary art, it more or less succeeds. As an example of contemporary architecture, it is a complete disaster.

It is an example of money trying to transform itself into art and architecture at a gigantic scale.

The Bourse is a building of note. Its basic structure is that of the Halle aux blés, the grain exchange that it housed between 1767 and 1873. After its wooden dome burned down in 1802, Jean Francois Belanger redesigned it to offer not only a functional interior clothed with a classical exterior of great refinement but also to show off the new structure of iron and glass (ferrovitreous architecture, for the nerds) with great panache.

When it became the stock exchange in 1885, Henri Blondel redesigned it in a simpler manner, while five different artists added paintings around the central rotunda that glorified French colonial power. After years of neglect and misuse, the Bourse fell into the hands of one of France's two Titans of Luxury (the other being Bernard Arnault, who, although controlling the greater empire of LVMH, had to console himself with a somewhat better Frank Gehry building on the outskirts for his LVMH Foundation).

Pinault actually has an eye – or has eyes who work for him – and has thus built up a collection of contemporary art that is not only strong but also consistent, concentrating on representational work that ranges from the surreal to the evocative to the hyper-realistic. He collects in depth, and the galleries with work after work by Peter Doig, Marlene Dumas, David Hammons, or Kerry James Marshall are enough to make you forgive many (if not all) sins.

Unfortunately, Pinault also loves Tadao Ando, the former boxer whose work always photographs much better than it is. Ando, in turn, loves concrete and pure geometry. He does not seem to care where he puts his circles and squares. He works with clients, such as Pinault, who can help him assure that the concrete is as fine as marble. The two already strutted their stuff in Venice's Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana, but now they have plunked themselves down in the heart of Paris.

It should have been a job of restoration and that effort has been done with great care by Pierre Antoine Gatier (France's Director of Historic Buildings) and a studio called NeM. The building and its decoration look as if they were finished a few days ago, and most new services have been tucked away with all the skill that good design and money can afford.

The only evidence of friction is the battalion of new lights hanging from the ceilings and the light that, despite scrims, rakes paintings with light. In the basement, the concrete continues as the walls of a small auditorium that is intimate and pleasant, while visitors have the chance to explore the original air conditioning equipment, which is as intricate and beautiful as any of the works of art on display above.

Obscuring everything but the dome, the circle creates a central space that I am sure will be great for parties.

If Ando had shown his generosity by concentrating on how all that worked and by adding those touches that would form an apt counterpoint to the existing structure, it would have been enough. However, he felt it necessary to follow up the work he did for Pinault in Venice by inserting the concrete walls that are his trademark. Here, they mainly take the form of a circle he erected on the former trading floor.

Obscuring everything but the dome, the circle creates a central space that I am sure will be great for parties, and that currently house a few nicely ironic sculptures that turn out to be melting candles, created by Urs Fischer.

Their other function is to provide a secondary staircase to the upper levels, and an outlet for air. The latter causes a lip to protrude that manages that only to ruin one's view of the architecture from the floor but does the same from the balconies above. There is no art hung on these massive walls.

Do we really have to look at Black people serving and doing obeisance to their conquerors one more time?

What that space really needs is not some Ando-ness, but some context or relativizing of the frieze on the dome above it. Do we really have to look at Black people serving and doing obeisance to their conquerors one more time, especially if it is in what is not a particularly good painting? Do we really need to stand in a sanitised place of exploitation through money, ironised only by wry sculptures, but monumentalised by architecture?

The artists whom Pinault has collected can hope that their messages, which are critical, evocative, and in some cases powerful beyond any Gucci bauble the billionaire can sell us, will cut through the conditions in which they are shown –although the white walls, fancy lights, and aestheticizing an in-your-face artist such as David Hammons confronts here makes you wonder about that.

The architect could have done a much better job digging, excavating, exposing, and confronting the two centuries of material present here. Instead, Ando not only drank his concrete martini but created an affectless tomb for all those who suffered and died to make this display possible.

The main photo is by Patrick Tourneboeuf.

Aaron Betsky is director of Virginia Tech School of Architecture and Design and was president of the School of Architecture at Taliesin from 2017 to 2019. A critic of art, architecture, and design, Betsky is the author of over a dozen books on those subjects, including a forthcoming survey of modernism in architecture and design. Trained as an architect and in the humanities at Yale University, Betsky was previously director of the Cincinnati Art Museum (2006-2014) and the Netherlands Architecture Institute (2001-2006), and curator of architecture and design at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (1995-2001). In 2008, he directed the 11th Venice International Biennale of Architecture.

The post "Tadao Ando's equivalent of what a dog does to a lamppost" appeared first on Dezeen.

0 notes