#metatheria

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Sulestes

Sulestes was a genus of deltatheroidean mammal from the Cretaceous Period. Its type species is S. karakshi. The known specimens were found in the Bissekty Formation, Kyzyl Kum desert, Uzbekistan. Sulestes was the first and currently only identified metatherian taxon from the Bissekty Formation.

Its autapomorphies include the first premolar's oblique orientation relative to the dentary, an asymmetrical third molar, the presence of a fourth non-vestigial molar, and a double-rooted first premolar.

Sulestes is known from its holotype, a left maxilla fragment, as well as referred specimens. These specimens were originally labelled under "Deltatherus" and "Marsasia" and consist of a right petrosal, right maxilla, two left maxilla fragments, left coronoid process, several right and left dentary fragments, and a few isolated teeth. Sulestes is recovered as the sister taxon to Deltatheroides and Deltatheridium within Deltatheroida.

Citations: The original description paper, Nessov 1983, is not available online. Nessov and Russell 1994 (description); Averianov, Archibald, and Ekdale 2010 (referred material).

Wikipedia article: here

#mammal#mammalia#paleoart#paleontology#artwork#original art#human artist#sulestes#deltatheroida#metatheria#theria#obscure fossil animals#obscure fossil mammals#obscure fossil tetrapods

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marsupials (overview)

Hello, desktop Tumblr it is time to talk about mammals again >:)

I can feel my roommate watching me over my shoulder...

also wow using grammerly on desktop is really annoying! but I can use titles???? woo!

I think I regret choosing desktop for this.... oh well! lets get into it

Ok so we left off talking about monotremes and I will have a post about their bones at some point I pinky swear I just need to figure out what I want to talk about. ok anyways today let's see what should we talk about hmm.... drumroll please.....

Metatheria!

So metatheria are the marsupials of the animal kingdom you've heard of a lot of them and I'm sure you know their calling card- pouches. but we are getting INTO it tonight guys heheheh

ok so some Latin facts- we know that protheria (monotremes) means 'first beast' but metatheria means "in-between beasts"

the first/oldest protheria we know about is the sinodelphys they are found mostly in Australia and South America due to a lack of placental mammals during the whole continental drift business.

ok so what makes a marsupial a marsupial? well let's get into a few relatively universal traits amongst them (remember folks nature doesn't read biology books so some of these are special or gone in certain groups)

so bones (BONES!!!!)

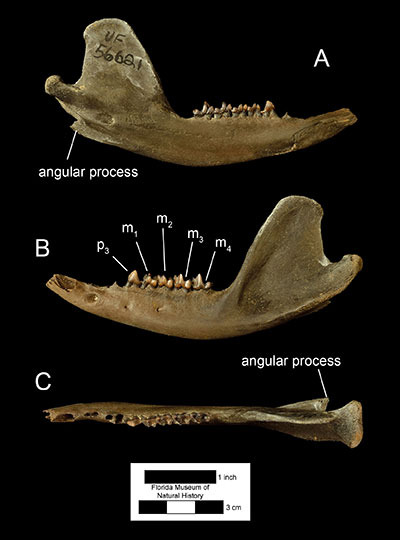

so the pelvic and jaw bones in a metathere are different than in eutheres (we will talk about them next teehee) they do not have a rounded angular process and it's instead spiky (here's a picture of a possum jaw for reference)

There are also extra openings in the back of the pallet and a smaller brain case their teeth are funky too! They have an extra set of incisors.

so I mentioned their funky pelvic bones but what I mean by that is their reproduction is wacko. so like monotremes they have a cloaca and not a vaginal and anal opening. this is why they're "in-between beasts" they have traits that are similar to both ends of the spectrum.

speaking of reproduction their cloaca is subdivided and they will hold eggs internally with a specialized membrane. this membrane surrounds the fetus more than an egg would with a floating placenta surrounding the fetus unlike in us this placenta isn't attached to a uterine horn. Their reproductive structure is also loopy... I'm not kidding look at this shit- this is a kangaroo reproductive structure

WEIRD! They have a pseudovaginal canal which is only there for birth and is part of the cloaca also keep an eye on that second uterus ill get into that more with kangaroos specifically

and it's only in females male reproductive structure is normal

their young are always born underdeveloped. they have an extended lactation period because of this with that special changing milk we mammals have that will deliver the perfect amount of nutrients needed.

so the babies are born super early but those ungrateful little turds have the immediate responsibility to get THEMSELVES into their mother's pouch. Mamma can't help you do everything little Joey.

I need to expand on this because it's fucking INSANE ok so like I said they are underdeveloped and I mean like VERY underdeveloped as in they do not have a full heart or brain yet!!!!! their lungs are just sacks and they don't have a jaw but they DO have a tongue and arms that they use to pull along their mother's hair to get to the milk. again- mama ain't helping you.

Ok i'm ending this here only because this is just general overview stuff and then I'm gonna get into specific species and families next staring with kangaroos :)

#Animal facts#zoology#animals#mammals#mammalogy#special interest#kangaroo#metatheria#college student#biology#animal reproduction#bones#bone facts#wooo lets hear it for animals raaaaah#marsupials#im dyslexic sorry for typos

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chunia

Chunia — примітивний ектоподонтид. Це була особлива група кайнозойських австралійських кускусових, які, можливо, були спеціалізованими насіннєїдами. Ектоподонтиди, яких спочатку вважали однопрохідними, мали коротку морду, великі, спрямовані вперед очі і найбільш незвичайні та складні зуби серед усіх сумчастих. Chunia, найпримітивніший з ектоподонтидів, мав корінні зуби, які були простішими, ніж у інших ектоподонтидів,…

Повний текст на сайті "Вимерлий світ":

https://extinctworld.in.ua/chunia/

#chunia#australia#marsupialia#oligocene#mammalia#metatheria#diprotodontia#paleoart#paleontology#prehistoric#art#illustration#ua#animals#digital art#animal art#science#daily#extinct#палеоарт#палеонтологія#fossils#article#ukraine#ukrainian#україна#мова#українська мова#арт#український tumblr

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

0 notes

Text

He's Australian; those are kangaroo teeth

two words: bunny teeth

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

I feel sorry for marsupials; the placental mammals like us get to be Eutheria (good beasts), while they’re apparently stuck being Metatheria (mid beasts).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Towards the end of the Cretaceous, about 69 million years ago, the most diverse and numerous mammals in the northern hemisphere were the metatherians, close relatives of modern marsupials.

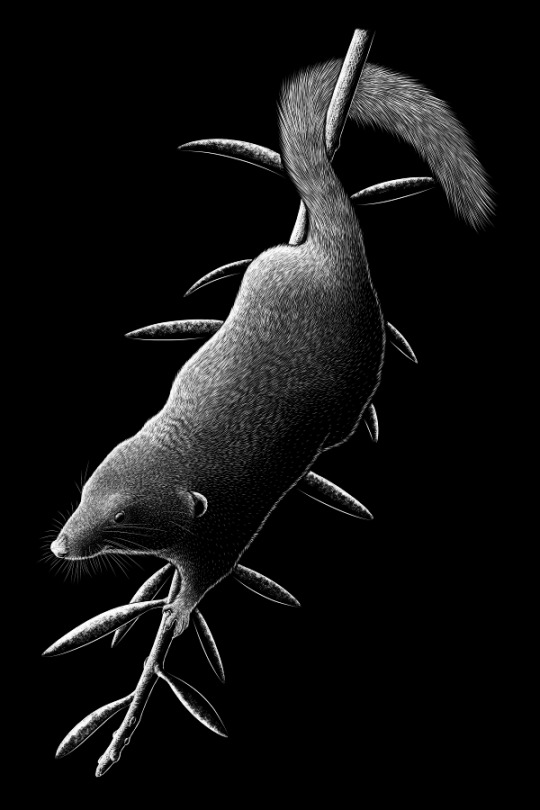

And Unnuakomys hutchisoni was the most northern-living of all these metatherians.

About the size of a modern mouse, around 10-15cm long (4-6"), and with teeth that suggest it was a shrew-like insectivore, this little metatherian lived in northern Alaska in what's known as the Paaŋaqtat Province – a region with a distinctive population of endemic polar animals. At the time this area was located at an even higher latitude than it is today, around 80-85ºN, but due to a greenhouse climate it was also warmer, with no permanent ice and the average temperatures staying above freezing.

Unnuakomys was by far the most common mammal species in the Paaŋaqtat Province, represented by numerous fossil teeth and a few jaw fragments, and it also seems to have been the only metatherian living in the whole region. This may just be a preservation bias in the fossil record, but it might also indicate that Unnuakomys was uniquely specialized to endure the several months of continuous darkness each winter in its polar woodland environment, while other North American metatherians were restricted to more southerly latitudes.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#unnuakomys#pediomyidae#marsupialiformes#metatheria#theria#mammal#art#paaŋaqtat province#(pronounced 'pah-ang-ak-tut')

251 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Spotted-tail quoll (Dasyurus maculatus)

Photo by Caleb McElrea

#spotted tail quoll#tiger quoll#quoll#dasyurus maculatus#dasyurus#dasyurini#dasyurinae#dasyuridae#dasyuromorphia#australidelphia#marsupialia#metatheria#mammalia#tetrapoda#vertebrata#chordata

859 notes

·

View notes

Photo

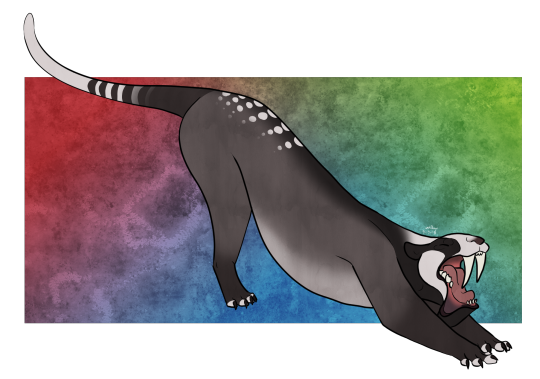

UK just went into a lockdown today, I have a lot of not very well defined thoughts about it, so naturally, I'm doing some Thylacosmilus studies. Here's the first one done. He's either just yawning, or maybe it's a threat display. Yes, his ears aren't flattened against his head, but I based this on thylacines, tasmanian devils, and american opossums who didn't/don't seem to be flattening their ears as a part of their threat displays either. At least that's what it looks like to me in pictures and videos. Of course, thylacines, devils, and opossums aren't related to Thylacosmilus, but since the jaws-agape-ears-not-folded threat display seems to be quite common among modern metatherians across different genera, I've decided to go with this, rather than ears-folded-lips-in-a-snarl placental thing. And yes, something bit his ear. I don't know what it was, but it doesn't seem to bother him much. I feel like I could have added more loose tissue around the lower jaw, since the lips would be so substantial, but I quite like how this turned out anyway. Also, I used yawning bloodhounds and basset hounds as reference for the lips situation, since they're very gifted in the jowls departament.

#palaeoblr#paleoart#palaeoart#sciart#synapsida#synapsids#pliocene#scientific illustration#extinct mammals#prehistoric animals#South America#sparassodonta#metatheria#saber tooth#Thylacosmilus atrox

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thylacosmilus

Scientific name: Thylacosmilus atrox Diet: Herbivorous mammals, with some supplemental fruit Projected natural lifespan: 20 years Length: 1.2 meters (4 feet) Weight: 80 kg (176 lbs) Locality: Northern Argentina; 9-3 Ma (Miocene-Pliocene) Exhibit: South America

About Thylacosmilus is one of the largest and last of the sparassodonts, a group of South American predators closely related to marsupials. It has two large saber-like teeth in the upper jaw - but unlike those of saber-toothed cats, they’re rooted far back in the skull. The lower jaw has a pair of flanges at the front that shield the saber teeth. Thylacosmilus has a relatively low bite force, instead using its powerful arms and neck to force prey into submission.

At Huxley Thylacosmilus can be found in the Cenozoic South America section. One of our younger Thylacosmilus is an ambassador animal - you can visit him at the Anning Paleontological Museum on weekends!

Notable Behavior We have three adult Thylacosmilus that we rotate through the exhibit areas. Although we gave them the opportunity to interact with each other, they did so rarely. A lot of times, when they see each other, they do what we think is a territorial display: they will open the jaws wide - up to almost 110 degrees! - and show off the saber teeth. They all use the same areas of their enclosures as a latrine, including where they mark territory.

Like the incisor teeth of rodents, the saber teeth of Thylacosmilus never stop growing through their life. In order to keep the teeth at a manageable size, we give them lots and lots of things to chew on, from durable rubber toys to rawhide and bones. They’re very good at destroying things.

Keeper Notes Have you ever been licked by a Thylacosmilus? They have huge tongues and they drool. A lot.

124 notes

·

View notes

Note

Unfortunately, as Anon 2 points out, it takes 8 weeks for a human fœtus to form, and the goat is only around until new year's assuming it is not set on fire first. Even if you have already infiltrated the goat, a fœtus is simply not achievable in this timeframe. May I suggest a Tammar Wallaby instead? Birth is at 26 days, by which time all organs and tissues have appeared though not matured (the definition of fœtus) and in fact organogenesis is complete before then, with at least one paper [3] using "fœtus" for day 20. This gives you until the 27th of December, leaving four whole days during which to obtain a wallaby.

"But Diplodocus," you might say, "Anon specified that they intend to create a fœtus inside the goat, which implies they are participating in the process by either sex / parthenogenesis (unworkable unless Anon is also a kangaroo), or artificial insemination /IVF (possible but complicated within the limiting confines of a 12.5m goat). Surely this cannot be done."

Aha! Let me introduce you to embryonic diapause, a remarkable feature whereby kangaroos and wallabies can, after fertilisation, hit pause and hold a viable embryo of 70-100 cells (blastocyst) in the uterus until the current joey exits the pouch, at which point development will resume. Manual removal of the pouch young (fœtus or joey) can therefore be said to create a fœtus, and so, Anon: all you need is a pregnant, carrying kangaroo, and perhaps a helmet.

Just in case.

References (all links are free-access excepting Google Books, where some pages are not available):

Dawson, T. J. (1995). Kangaroos : biology of the largest marsupials. Unsw Press.

Dawson, T. et al. (1989). 17. Morphology and Physiology of the Metatheria. In Fauna of Australia / 1B, Mammalia / vol. eds.: Dan W. Walton. Australian Government Publ. Service.

Drews, B. et al. (2013). Ultrasonography of wallaby prenatal development shows that the climb to the pouch begins in utero. Sci Rep., 3. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01458

Jirik, K. (n.d.). LibGuides: Red Kangaroo (Marcopus rufus) Fact Sheet: Reproduction & Development. San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Library

Kangaroo Development - Embryology. (2024). Unsw.edu.au.

Renfree, M. B., & Tyndale-Biscoe, C. H. (1973). Intrauterine development after diapause in the marsupial Macropus eugenii. Dev Biol., 32(1), 28–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/0012-1606(73)90217-0

Im going to create a fetus inside the giant wooden goat

by yourself????

#and if the jackdaws eat the goat the kangaroo will be fine#<-- sentence nobody has ever made before#hasgavlebockenburneddownyet#animals#marsupialia#kangaroos & wallabies#tumblr memes#images have alt text

234 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anachlysictis

Anachlysictis — рід вимерлих хижих ссавців з групи Sparassodonta, представник метатеріїв (група, що включає сумчастих та їхніх близьких родичів), котрі населяли Південну Америку протягом кайнозою. Типовий вид — Anachlysictis gracilis.

Повний текст на сайті "Вимерлий світ":

https://extinctworld.in.ua/anachlysictis/

#anachlysictis#mammal#predator#sparassodonta#metatheria#cenozoic#south america#paleoart#paleontology#prehistoric#палеоарт#палеонтологія#animals#animal art#illustration#extinct#ukraine#ukrainian#article#digital art#art#science#ua#fossils#українська мова#україна#мова#арт#тварини#daily

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kelenken guillermoi

By Scott Reid

Etymology: For Kélenken, the Bird of Prey Spirit of the Tehuelche Tribe

First Described By: Bertelli et al., 2007

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Cariamiformes, Phorusrhacoidea, Phorusrhacidae, Phorusrhacinae

Status: Extinct

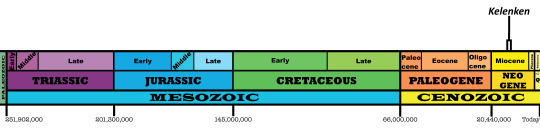

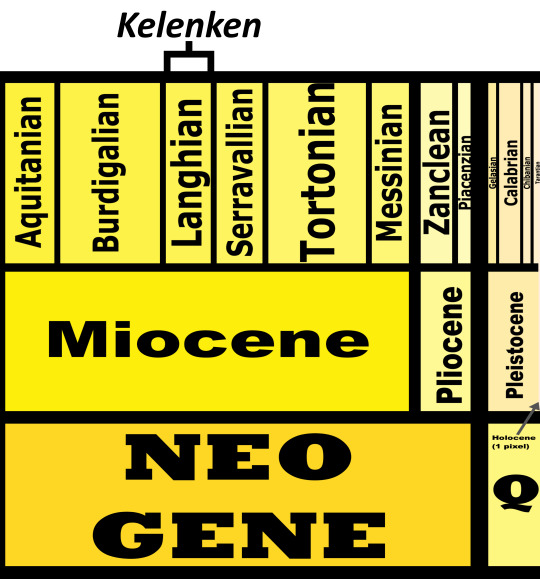

Time and Place: Between 15.5 and 13.8 million years ago, in the Langhian age of the Miocene of the Neogene

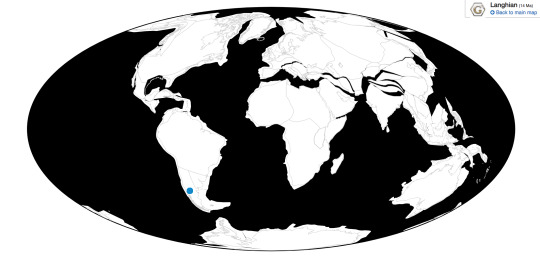

Kelenken is known from the Collón Curá Formation of Rio Negro Province, Argentina

Physical Description: Kelenken was a Terror Bird, a type of large flightless terrestrial dinosaur from the late Cenozoic era, mostly in South America though a few reached North America when the continents collided. These were some of the top predators of their environments, built for chasing down food over long distances and then using their monstrous beaks to tear into flesh. Kelenken was one of the biggest members of the group, about two meters tall, and it had one of the largest known skulls of any bird, with fused bones to give it significant strength in its head and strong bire force. Its limbs were very robust, probably allowing for powerful movements of the legs. It had very small wings, as other Terror Birds did, and as such they probably weren’t used very much (think of the arms of Carnotaurus but the bird version). It had a long, winding neck, and its head was mostly beak. The beak was hooked at one end. It had a short tail, though we don’t have any feather impressions to know if it had any sort of feather decoration at the end of it. It would have had a huge bite force, and it possibly was a faster runner than other Terror Birds.

Diet: Kelenken primarily fed on large animals, especially faster moving ones such as hoofed mammals

Behavior: Kelenken probably spent most of its time chasing down its prey, though it’s uncertain how. It’s possible that it would chase down prey, catch it, and shatter its bones with its beak by repeatedly pecking at it (if… pecking is an accurate word to use with such a huge beak doing the pecking). It’s also possible that it would chase down smaller prey, pick it up, and shake it vigorously to break the prey’s back. It also possibly scavenged off of prey. Honestly, it seems likely that Kelenken would utilize all these strategies, and those not even come up with, to get any prey it could in an opportunistic fashion.

By Michael B. H.

Kelenken was a fairly fast animal, and probably able to run for longer distances. As its environment was transitioning to an open grassland rather than a forest, this ability to run moreso than its earlier relatives was probably a direct adaptation for that open habitat. As such, Kelenken would have been extremely alert and on the lookout, both for food and for potential dangers, as it was tall enough to poke out above the grass and be visible to anything looking for it. Kelenken could fight with others of its species and against other animals both with its beak and with its feet, as it had very robust legs that would have been good for kicking, possibly very rapid and sharp kicks.

As only a few specimens of Kelenken are known, it’s difficult to determine its social behavior, especially since its closest living relatives are the Seriemas - a much smaller sort of dinosaur. Still, it’s possible to at least glean some behavioral patterns from seriemas. It’s possible that, like living seriemas, Kelenken only spent its time in pairs and small groups, which may have worked together cooperatively to take down larger mammalian sources of prey. It’s also possible that it may have been territorial over its nests, with breeding pairs avoiding other Kelenken and fighting with those they come across. This is all speculative, but would make sense given the environment and size of the animals. Kelenken, being a bird, almost decidedly took care of its young, though we cannot know if both parents took care of the young as in modern Seriemas, or if only one parent did the job at a time as in modern flightless birds. More fossils might be able to clear up this picture, though of course, it’s possible we’ll never know.

By Ripley Cook

Ecosystem: Kelenken lived in the part of the Miocene that was the hottest, called the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum. This was immediately followed by drastic cooling. Thus, Kelenken lived in a uniquely warm period of the time in which Terror Birds dwelled. The formation was surrounded by extensive rivers and lakes, as basins formed in South America due to tectonic plates separating. This environment was a growing grassland, with the pampa overtaking the old deciduous forest that had once been there.

Kelenken is the only dinosaur known from the formation, but there were many different types of mammals present. There were the heavy-bodied hoofed mammals Protypotherium, Epipatriarchus, and Interatherium; the smaller hoofed mammals Hegetotherium and Pachyrukhos; the weird fast hoofed mammal related to Macrauchenia, Theosodon; armadillo relatives such as Proeutataus, Paraeucinepeltus, Peltephilus, Prozaedyus, and Stenotatus; the anteater relative Neotamandua; the rodents Galileomys, Guiomys, Maruchito, Microcardiodon, Neosteiromys, Protacaremys, Acarechimys, Alloiomys, Megastus, Neoreomys, Prolagostomus, and Stichomys; the new-world monkey Proteropithecia; the sabre-toothed marsupial Patagosmilus; and the extinct shrew opossum relative Abderites. There were also reptiles such as boa relatives like Waincophis, lizards, and turtles like Chelonoidis. There was also the horned frog Wawelia.

Kelenken probably would have hunted a variety of these things, especially the hoofed mammals, though some would have been too big for it to eat. It definitely would have been in direct competition with Patagosmilus, which probably would have specialized on different prey than Kelenken.

Other: Kelenken is most closely related to phorusrhacids such as Phorusrhacos and Titanis, two of the other more famous genera in this group.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Abello, María Alejandra, and David Rubilar Rogers. 2012. Revisión del género Abderites Ameghino, 1887 (Marsupialia, Paucituberculata). Ameghiniana 49. 164–184. Accessed 2019-02-15.

Albino, A.M. 1996. Snakes from the Miocene of Patagonia (Argentina) Part I: The Booidea. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 199. 417–434. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Angolin, F. L., P. Chafrat. 2015. New fossil bird remains from the Chinchinales Formation (Early Miocene) of Northern Patagonia, Argentina. Annales de Paleontologie 101: 87 - 94.

Baez, A. M., S. Peri. 1990. Revision de Wawelia gerholdi, un anuro del Mioceno de Patagonia. Ameghiniana 27(3-4):379-386

Bertelli, S., L. M. Chiappe, C. Tambussi. 2007. A new phorusrhacid (Aves: Cariamae) from the middle Miocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27(2): 409 - 419.

Bondesio, P.; J. Rabassa; R. Pascual; M.G. Vucetich, and G.J. Scillato Yané. 1980. La formación Collón-Curá de Pilcaniyeú Viejo y sus alrededores (Río Negro, República Argentina) su antiguedad y las condiciones ambientales según su distribución su litogenesis y sus vertebrados. Actas del Segundo Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía y Primer Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología 3. 85–99.

De Broin, F., and M. De la Fuente. 1993. Les tortues fossiles d'Argentine: synthese (The fossil turtles of Argentina: synthesis). Annales de Paléontologie (Invertebrés-Vertebrés) 79. 169–232. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Forasiepi, A.M., and A.A. Carlini. 2010. A new thylacosmilid (Mammalia, Metatheria, Sparassodonta) from the Miocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Zootaxa 2552. 55–68. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Gonzaga, L. P., A. Bonan. 2017. Seriemas (Cariamidae). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

González Ruiz, Laureano Raúl; Flavio Góis; Martín Ricardo Ciancio, and Gustavo Juan Scillato Yané. 2013. Los Peltephilidae (Mammalia, Xenarthra) de la Formación Collón Curá (Colloncurense, Mioceno Medio), Argentina. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 16. 319–330. Accessed 2019-02-27.

González Ruiz, Laureano Raúl; Alfredo Eduardo Zurita; Gustavo Juan Scillato Yané; Martín Zamorano, and Marcelo Fabián Tejedor. 2011. Un nuevo Glyptodontidae (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Cingulata) del Mioceno de Patagonia (Argentina) y comentarios acerca de la sistemática de los gliptodontes "friasenses". Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas 28. 566–579. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Kay, R.F.; D. Johnson, and J. Meldrum. 1998. A new Pitheciin Primate from the Middle Miocene. American Journal of Primatology 45. 317–336. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Kramarz, Alejandro; Alberto Garrido; Analía Forasiepi; Mariano Bond, and Claudia Tambussi. 2005. Estratigrafia y vertebrados (Aves y Mammalia) de la Formación Cerro Bandera, Mioceno Temprano de la Provincia del Neuquén, Argentina. Revista Geológica de Chile 32. 273–291. Accessed 2017-10-20.

McDonald, H.G.; S.F. Vizcaíno, and M.S. Bargo. 2008. Skeletal anatomy and the fossil history of the Vermilingua, 64–78. S. F. Vizcaíno, W. J. Loughry (eds.), The Biology of the Xenarthra. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Náñez, Carolina, and Norberto Malumián. 2019. Foraminíferos miocenos en la cuenca Neuquina, Argentina: implicancias estratigráficas y paleoambientales. Andean Geology 46. 183–210. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Oriozabala, C.; J. Sterli, and L. González Ruiz. 2018. Morphology of the mid-sized tortoises (Testudines: Testudinidae) from the Middle Miocene of Northwestern Chubut. Ameghiniana 55. 30–54. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Pardiñas, U.F.J. 1991. Primer registro de primates y otros vertebrados para la Formacion Collón Curá (Mioceno medio) del Neuquén, Argentina (First record of primates and other vertebrates from the Collón Curá Formation (middle Miocene) of Neuquén, Argentina). Ameghiniana 28. 197–199. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Pearson, Paul N., and Martin R. Palmer. 2000. Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations over the past 60 million years. Nature 406. 695–699. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Pérez, M.E., and M.G. Vucetich. 2011. A new Extinct Genus of Cavioidea (Rodentia, Hystricognathi) from the Miocene of Patagonia (Argentina) and the Evolution of Cavoid Mandibular Morphology. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 18. 163–183. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Pérez, M.E.. 2010. A new rodent (Cavioidea, Hystricognathi) from the middle Miocene of Patagonia, mandibular homologies, and the origin of the crown group Cavioidea sensu stricto. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30. 1848–1859. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Rehr, D. 2007. Prehistoric Predators - Terror Bird. 5:40 - 11:40. National Geographic.

Silvestro, Daniele; Marcelo F. Tejedor; Martha L. Serrano Serrano; Oriane Loiseau; Victor Rossier; Jonathan Rolland; Alexander Zizka; Alexandre Antonelli, and Nicolas Salamin. 2017. Evolutionary history of New World monkeys revealed by molecular and fossil data. BioRxiv _. 1–32. Accessed 2017-09-24.

Tambussi, C. P. 2011. Palaeoenvironmental and faunal inferences based on the avian fossil record of Patagonia and Pampa: what works and what does not. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 103: 458 - 474.

Vera Nardoni, Bárbara; Marcelo Reguero, and Laureano González Ruiz. 2017. The Interatheriinae notoungulates from the middle Miocene Collón Curá Formation in Argentina. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 62. 845–863. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Vucetich, M.G., and A.G. Kramarz. 2003. New Miocene rodents from Patagonia (Argentina) and their bearing on the early radiation of the Octodontoids (Hystricognathi). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23. 435–444. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Vucetich, M.G.; M.M. Mazzoni, and U.F.J. Pardiñas. 1993. Los roedores de la Formación Collón Curá (Mioceno Medio), y la ignimbrita Pilcaniyeú, Cañadón del Tordillo, Neuquén. Ameghiniana 30. 361–381. Accessed 2019-02-27.

#kelenken#kelenken guillermoi#terror bird#bird#dinosaur#birds#dinosaurs#birblr#palaeoblr#neogene#south america#carnivore#terrestrial tuesday#australavian#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#factfile#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

312 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Photo by Rob McLean

#sourcing#numbat#myrmecobius fasciatus#myrmecobius#myrmecobiidae#dasyuromorphia#australidelphia#marsupialia#metatheria#mammalia#tetrapoda#vertebrata#chordata

858 notes

·

View notes

Note

Woah didn’t know dragonflies have been around that long!! Wasn’t there one that was like 3 feet long or something? The Metatheria, the Clade that marsupials descended from dates back to around the late Jurassic, so the lil possum’s grandpaw was running around with dinosaurs

Yup! The only real change in evolution for the dragonflies have been its size. They were around before mammals, I think. Or was it marsupials...? Idk, but they have been around for a LONG time.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry if this sounds dumb, but how exactly did the non extant groups of mammals (i.e. those outside of eutheria, metatheria, and monotremata) bring forth their offspring?

Outside of Holotheria, the answer would have probably been eggs. For pretty much the entire expanse between where monotremes branched off, marsupials, and eutherians, however, nobody really knows (although I’d presume it probably wasn’t extended pregnancies as in eutherians).

6 notes

·

View notes