#mental illness is not about being fucked up or subversive its about sickness and addiction and pain

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

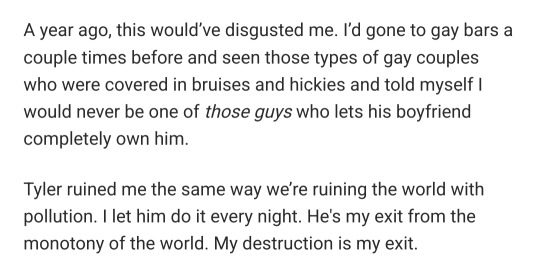

reading fight club psycho smut and this is killing me. he ruined me the same way we're ruining the world with pollution

#i am a slave to my baptism!!!#we are god's unwanted children!!#dean and cas' queerbait is actually kind of legit as masculinity in media#there's the obvious depravity sacreligion motif. yeah we've all seen it#but there's also the abandonment of the father figure that creates a toxic environment of male circle jerking validation#you kno what i find most compelling about fight club is self destruction as self-actualisation purely out of hurt and spite#being told ur the warm gooey centre of the world and not getting you need. the primary function in the nuclear household being that#everyone lets the man do whatever he wants does everything for him and in return he provides them with what only he can but you see#this masculinity in media aka im the problem its me media is about portraying this Hidden struggle of man but like#the solution is obvious and its this hubris of man to not take it because he believes he is destined for something greater thats the issue#i love the narrative as man as the main character i love it about women too i love when we look at the world so intensely through one view&#it being pretty fucked up because u kno in fight club there is still morality there are good intentions there is Beauty even if theres no#love.....#tyler durden as an analogy for self denial. another religious motif!!#i think you have to be truly philosophical to get meaningful fulfillment in life& media like fight club and taxi driver are inherently so!#joker is purely about mental illness which is why it sucks#mental illness is not about being fucked up or subversive its about sickness and addiction and pain#fucked up as a title of honour#there is something deeply empathetic and beautiful about the feeling of connecting with the injustice of the world that we need to do more#through engaging with fiction materials

0 notes

Text

THE THE LOGICAL CONCLUSION TO THE KITCHEN SINK DRAMA

With its frequent references to an underfunded NHS, grim bursts of hedonism and explosive misdirected rage, Nil By Mouth (Gary Oldman, 1997) is a masterclass in British realism which not only deserves, but requires a remaster in 2022 (and a wide release in every British cinema if I had my way). Inspired by Oldman’s youth in New Cross, the film focuses on a working class family terrorised by the alcoholic patriarch Ray (Ray Winstone) and held together by the stoic matriarch Janet (Oldman’s sister Laila Morse) whose factory job provides for basic necessities including her son Billy’s (Charlie Creed-Miles) heroin addiction. Ray is the husband and abuser in chief of Janet’s horrifically mistreated, despairingly strong, pregnant daughter Val, portrayed sublimely by a haunted Kathy Burke in one of the greatest British performances ever put to screen.

The film places viewers directly into the action, leaving the messy web of relationships to be discovered as we are drawn into the films extraordinarily detailed and dizzying world of depravity. Starting in a large and blue dimly lit social club, an aura of menace arises from the first shot. In a close up we first see Ray demanding the barman for a insane amount of booze as the camera, in close up shots, whips from detail to detail, capturing and mirroring the heady drunken night in full swing. Children and families are present as a comedian on stage spits the most misogynistic jokes imaginable, in a place you’d hope would be a refuge from the oppression its inhabitants suffer in the outside world. The camera, snapping between extreme close ups of punters’ faces, is eternally spinning and we follow Ray back to the table where Val and some friends are sat. He plonks some drinks, grunts vaguely at them and then walks off to join his bloke mates with the rest of the alcohol. Once there his sleazy friend and favourite enabler, Mark (Jamie Foreman) mirrors the discourse of the comic with a hedonistic tale of an orgy he once attended. The audience, not yet grasping the lengths of the two mens violence against women, is compelled to laugh at the absurd crassness of the tale.

At some point after this introduction into their world, the family (Ray, Mark, Val and Billy) are sat in Ray and Val’s flat and Mark and Ray are entertaining Billy with stories of their youth, this time focused on extreme senseless violence. A murder commited by a clearly mentally ill former classmate is remarked upon by Ray asking rhetorically “Who the fuck gave him a gun?” leading us to question why instead of being helped, the classmate was given a tool for violence which, obviously, he used. When Val tries to enquire about the story, watching with hollow eyes from the kitchen as she makes the men tea, she is told to shut up, belittled and called a cunt (as of 2019, the movie contains the most uses of this word in any film). She can never become a part of their sick world even when she attempts to be complicit in it. Their conversation also swings to their incredibly excessive substance abuse, Mark and Ray’s potion of choice in their youth being prescription pills and booze – “blueys, reddies, greenies, uppers, downers” – a desperate attempt to self medicate with a subversion of the tools given to them by the NHS. Mark is also surprisingly candid, although dismissive, of his experience with depression, claiming the “happy” pills they gave him to treat his case made the user violent, “likely to murder your parents”, one of the many markers of distrust in the film in relation to a decaying social system and a demonstration of the neo-liberal American grip tightening on the throat of the NHS. Even if the pills don’t provoke such an extreme reaction they are entirely numbing, leaving sleazebag Mark unable to “fuck” to his absolute dismay. The soundtrack, written by Eric Clapton, aids in this air of faux Americana as his blues riffs spiral and repeat throughout the film, providing an engrossing trance-like state whilst also being reminiscent of the sparse arrangements of a Morricone backed Western. This talk of medical imagery, present in the title of the film itself, conjures the writing of Mark E Smith as part of The Fall, their ballad “Mr. Pharmacist” being a damning takedown of the hypocracy around legal drugs and their sedating, numbing effects on society. This distrust in the of the NHS under its state of managed decline also extends to the female characters in the film, the people most vulnerable and in need of refuge. Potentially the most shockingly violent and unflinching scene in any kitchen sink drama, which for the sake of it’s pure cinematic and social power and already available discussion I will not be exploring explicitly, occurs around the halfway point of the film. The scene afterwards masterfully dismantles the shock value of the violent episode, using the viscerality to its benefit, lingering on the emotional, micro-structural implications rather than upping the ante. A horrifically disfigured Val lies to Janet that she has been run over. It is evident Janet is not buying her story but in an act of conditioned British foolishness refuses to press further. When asked why she didn’t go to the hospital, Val responds “you know what hospital is like at night.”. One can only imagine the kinds of violence fuelled by social mismanagement and underfunding which could provoke such a hesitancy to seek help in the exact place one should find it.

Ray and Val are the two characters we see the most of, their respective actors delivering the richest performances. The character in the family we see the least of is their daughter. Raging desire to feel anything has left Ray with many children, a precise amount never given. Is her absence a sign of his lack of care? Most likely not, rather forcing audiences to identify with this tabula rasa of consciousness, who has only been privy to violence from her Father in her life. The harrowing radial point scene is ended by Ray saunters off the hellish, paranoia fuelled assault on his wife and in a wide shot constricted by a flight of stairs, sees his daughter at the top of them. Viewers have to speculate whether this pillar of innocence in the film was actually present during the beating and by extension, whether the point of spectatorship in the film is behind her eyes. This would certainly address the theme of cyclical abuse which Oldman is intent on exploring. When someone is exposed only to violence and witnesses only violence, they are likely to be violent. This much applies to Ray, who in a perverse therapeutic lapse in his utterly derranged macho demeanour, speaks to Mark of his Father putting down his beloved dog whilst on holiday with his Gran and being the same kind of violent drunk as himself. This childish scene of regression where he longs for the affectionate yet shallow displays of a Father, demonstrates the eternal scars that abuse leaves and the frigid and facistic men it can create. His cries are so childish and unlike the exterior we’ve witnessed that we realise this man, whilst being frank with Mark, is not deeply understanding the root of the psychic and politcal conditions that create such infernal scenes of poverty. Thus the cycle continues. This makes it easy to view the ending with its disturbing, reunion of the family due to Billy’s recent incarceration as unfathomably precarious. Everyone is smiling and in good spirits, but Billy is now in prison and being threatened to have his head cut off for snitching and siding with the powers that be. Val’s promise to have fun and be happy by leaving Ray and his patriarchal, objectifying acts of pathetic control is now in tatters. This can especially deject audiences when considering how full of joy she was in previous, brightly lit scenes without Ray anywhere near her. She is living her dream to not be “someone people feel sorry for”. Possibly to the detriment of the film, this is nearly all her character has been up until this point. The attention given to Billy and his heroin odyssey could be better spent on Val’s internal monologue. This includes a bizarre hand held long take where a fellow addict recites a scene from Apocalypse Now. This does not seem a politically relevant movie and more of a way for Oldman to insert Brechtian meta commentary and flex his directing chops, although I understand the commentary on dehumanisation and isolation. This makes the moments of lightness unbearably sad. Viewers that long to see her as a fleshed out character and identify with her will have this immediately snatched from them only a few scenes. And therefore, the final scene offers only the monochrome darkness of their flat, now mended by Ray after completely trashing it. Again, the only work Ray can put in is the literal physical reconstruction of his damage, rather than anything deeper.

This is a world where violence exists as a given. However, due to being a deeply personal piece of work, it doesn’t point fingers as explicitly at the causes of violence beyond the family. Yet this political imprecision is powerful because the viewer, through the grainy handheld camera, is a part of the family. We are forced to deal with the same reality that they deal with, including a structural inability to confront the governmental forces which have fostered such evil, without the physical means to create an environment of love. When seeing the world through the humanised and pharmaceutical-cloaked camera lens, viewers are left numb to the despicable suppression of the British working class, focusing on the misdirected cycle of rage and abuse that it leaves in its wake. The film ends with a dedication to Oldman’s father, his mother’s voice is dubbed in the scene where the family’s grandmother sings, his sister plays the matriarch holding the family together and his real Dad sat in the same armchair used in Ray’s flat. It is my opinion that we must congratulate Oldman for creating such a resonant piece which stands the test of time whilst being so deeply personal. The film is never dissatisfying in what it intends on achieving and the ambiguity of the ending is simply heart-shattering many years on.

MICHAEL PLASTIC

0 notes

Text

Girl Defined vs. Psychology

I’ve been meaning to do a response to what I personally consider to be Girl Defined’s worst blogs to date. I haven’t mentioned them before and I don’t think anyone else has either. While they’re deeply upsetting to digest, I don’t think they should go unnoticed.

The theme is mental health. Brace yourselves.

In Can the Bible Help with Depression, Eating Disorders, and Porn Addictions? Kristen makes a deceptive attempt to paint therapy as useless by giving fictional examples of young people who were not benefited by it. Their problem is that they “bought into the secular culture’s solutions for fixing our problems.” She thinks the constant state of struggling comes from ignoring the root issues (she's right so far, and that's literally what therapy is for), but what she means by that is that “root issues are almost always sin issues.” So in her examples Kristen says the one girl was depressed because she had an idol in her heart and the other had an ED due to a fear of man.

She then doubles down in a comment reply distinguishing that while “legitimate physical sickness” may require medical intervention, doctors are just guessing when they say mental illness is due to chemical imbalance.

While chemical imbalances are very real, this is a vast oversimplification of how psychologists and researchers explain mental disorders as a combination of biological, psychological, and environmental factors. (Too many specifically to list - basically every factor of your life story is relevant.) It's almost like people are extremely complex and because of their differences are susceptible to different vulnerabilities. But all this is boiled down to our failure to "call our sin, sin." Yeah, we’re all just happy blank slates, but some of us stubbornly choose to suffer. Fuck me with a spoon.

Someone in a semi-recent comment (not included in the archived version) says that this specific article literally caused her to attempt suicide. That’s exactly what these views lead to when followed to their conclusion. Your suffering must be because of something you're doing, but what if it isn’t? If Kristen and Bethany would consider that one simple question, they’d realize they're blaming people for their own illnesses, digging them a deep hole of shame, and barring them from real solutions for no fucking reason. There is no reason a Christian needs to believe toxic shit like this. Nothing in the Bible denies the possibility of mental afflictions being as real and as troubling as physical ones or that says there’s no value in the knowledge humans will uncover about ourselves.

Oh, and what do they suggest instead of "mainstream, secular therapy"? A biblical counselor, which anyone can be, and Kristen and Bethany are. So any random who knows how to look up Bible verses is to be trusted more than a professional who spent decades studying how to work with specific complex conditions. Wonderful.

The second blog at question is called Self-Esteem: Why Christian Girls Don't Need It. I’m sure you’re all smart enough to see the problem just from the title. They characterize low self-esteem as a teenage girl feeling self-conscious about her appearance, wanting a boyfriend, and wanting more likes on social media. I have avoidant personality disorder, which can be summarized as extremely low or absent self-esteem, so let me tell you what it means for me. I struggle to look people in the eye, find and keep a job, form relationships, and even have a basic sense of identity. What do they call this missing piece of my puzzle? “A myth.”

You absolute cunt rags. Self-esteem is not optional to life as a functional human. It doesn’t mean egoism or selfishness. It is the fundamental sense of stability and personhood from which you operate in all you do. Kristen and Bethany actually have very high self-esteem in order to be the faces of a very vocal public platform, which they then use to dismiss its importance to girls, many in vulnerable states of mind or stages in adolescence. But they promote self-respect through modesty and standing up for convictions. That takes self-esteem, babes.

What they're proposing here is full self-abnegation. Be so obsessed with serving God that your sense of self never even occurs to you. "Apart from Christ you don't have anything to be proud of... Christ is the only good in you." Yikes. Here's the deal. God can be the most important thing in your life and that is still a relational process. God does not eclipse you. You still exist as a self with your own distinct attributes, and you need the ability to trust your own interpretation and judgment and to operate from a place of confidence, no matter what your source is.

Ignorance on this subject is deeply offensive and unacceptable to me. It’s so unjust how they can propagate deeply subversive psychological damage while remaining blissfully confident they’re doing the right thing.

70 notes

·

View notes