#megaconus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Megaconus

Megaconus — вимерлий рід алотерієвих ссавців з середньоюрської формації Тяоцзишань у Внутрішній Монголії, Китай. Типовий і єдиний вид, Megaconus mammaliaformis, був вперше описаний в журналі Nature в 2013 році. Вважається, що Megaconus був наземною травоїдною твариною. Ймовірно він мав поставу, схожу на сучасних броненосців і гірських даманів (Procavia capensis).

Повний текст на сайті "Вимерлий світ":

https://extinctworld.in.ua/megaconus/

#megaconus#jurassic#inner mongolia#china#jurassic period#mammal#mongolia#herbivores#nature#paleontology#paleoart#prehistoric#animals#illustration#animal art#extinct#digital art#article#image#sciart#ua#палеоарт#палеонтологія#ukraine#ukrainian#україна#мова#українська мова#art#українцівтамблері

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

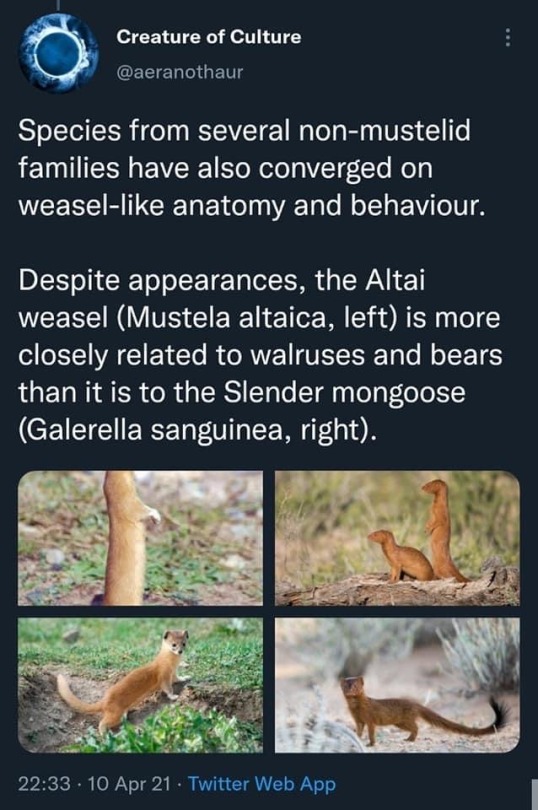

Check out this guy Megaconus mammaliaformis.

He was doin’ the rat/weasel-shaped generalist thing 165 million years ago. Mammals have been weaseling it up since they were running around the feet of dinosaurs.

68K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Month of Mesozoic Mammals #16: So Many Gliders Maiopatagium

The haramiyidan featured yesterday was a ground-dwelling animal, but most others in the group were actually highly adapted for tree-climbing. They were very squirrel-like in appearance, with grasping hands and feet and tails that may have been prehensile -- and some took this lifestyle even further, becoming specialized gliders.

Living during the Late Jurassic of China (157-163 mya), Maiopatagium is one of at least four known gliding haramiyidans. It was about 25cm long (10″), around half of which was its long tail, and had a gliding membrane extending between its wrists and ankles. The proportions of its hands and feet were very similar to modern colugos and the feet of bats, which has been interpreted as evidence of the same sort of upside-down roosting behavior.

Its close relative Vilevolodon had rodent-like teeth highly adapted for crushing and grinding, suggesting these haramiyidans were herbivores feeding mainly on seeds and soft plant matter.

And these gliding haramiyidans also contribute to the confusing classification of haramiyidans -- because although Megaconus’ anatomy suggested they might be mammaliaformes, studies of another glider, Arboroharamiya, give a very different result. Its ear bones and jaw show the characteristics of true members of Mammalia, supporting the hypothesis that haramiyidans were actually close relatives (or ancestral to) the multituberculates.

#science illustration#month of mesozoic mammals 2018#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#maiopatagium#vilevolodon#arboroharamiya#haramiyida#mammal#incertae sedis#mammaliaformes#allotheria#maybe#art#glider

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Are Humans Hairless Compared To Other Mammals?

Why Are Humans Hairless Compared To Other Mammals?

Human hairlessness is an evolutionary mystery. There are many theories out there, but two important ones are the savanna hypothesis and the ectoparasite hypothesis.

Humans are unique in many ways. We have the powerful tool of language, we have consciousness, and we have opposable thumbs. We conquered fire, water, air and even space. No other animal, not even the dinosaurs with their gargantuan size and sharp teeth could achieve this. However, we are probably the most different from other animals, especially mammals, in terms of our hair, or lack of it, to be more precise. Why aren’t we furry like our closest living relatives—the bonobos, chimps, and gorillas?

These bonobos can’t figure out why humans don’t have as much hair as them. (Image Credit: Flickr) Charles Darwin would answer this question with sexual selection. In 1871, in his book “The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex”, Darwin proposed the concept of sexual selection as “the advantage which certain individuals have over others of the same sex and species, solely in respect of reproduction”. This means that the purpose of certain characteristics is largely for flirtation. These characteristics help an animal secure a mate over other competing individuals. The Darwinian Homo sapiens lost their hair because males found less hairy females sexier. He reasoned that over generations of males picking less hairy mates, the overall population, of both males and females, became less hairy due to genetic mixing. This sounds like a logical argument when you have only half the facts. Darwin, the father of evolution, came up with the best explanation he could with the information on hand (and Victorian Era biases). Hair, hair everywhere To understand the flaw in Darwin’s argument, let’s look at what evolutionary biology has unearthed today about hair. Hair is a protein filament that grows from the dermis layer of your skin. Almost every mammal around us has a thick coating of hair or fur. Except for a handful of creatures, like the hairless mole rat (which only looks cute in Kim Possible, but is quite alarming in reality) and aquatic mammals like whales and dolphins, most mammals have hair. Land mammals evolved this hair because it gave them an edge on land. Fur is a great insulator against heat. The hair traps pockets of hair between them, keeping the heat in when it’s cold outside. Piloerection, also known as getting goosebumps, is a thermoregulatory mechanism of increasing these air pockets. The arrector pili muscles cause the hair to stand up, thus forming air pockets. The fur also protects the skin from the harmful UV rays of the sun. Hair is an extended sensory tool. Something brushing up against hair moves the hair follicles, which send signals to the brain to pay attention. This helps when pesky parasites like bedbugs or mosquitoes are lurking around trying to suck your blood.

An artist’s recreation of what the ancient Castorocauda probably looked like (Photo Credit : Nobu Tamura/Wikimedia Commons) Even with all of this that we understand, figuring out why, how and when animals upgraded to hair is difficult. Evidence often comes from fossils, which aren’t great at recording soft tissue impressions. The first undisputed evidence of hair comes from the fossilized hair impressions of Castorocauda, a semi-aquatic mammal that lived in the middle to late Jurassic Period (Callovian age). This puts the appearance of hair at least 164 million years ago (mya). Another fossil found in Mongolia appeared to show fur on a mammal, and the researchers named this specimen Megaconus. All this evidence leads back to a common ancestor of mammals, the reptile-mammal—synapsids. Hair, Hair Nowhere: Darwin’s explanation works perfectly fine in the modern world (more or less). Some males do find females with less hair more attractive, but some others might not. Another group might not care. In all this, culture dictates attractiveness. This is where Darwin’s argument breaks down. Our hairlessness is not the only component for mate selection, as it is in male birds with vibrant plumage or odd dance rituals linked to mating. Darwin’s sexual selection hypothesis fails to specify what caused the hair loss in the first place. While Darwin didn’t solve the mystery, he did open the floor for later evolutionary biologists to present their own theories. These figures didn’t disappoint. The Savanna Hypothesis The ‘Savanna hypothesis’ is the current favorite. Whenever research published supports or denies this theory, the science communication space scrambles to cover the shift. Proposed by Raymond Dart in 1925 after discovering the first Australopithecus skeleton in Africa, the hypothesis fits our visions of pre-man the best. The hypothesis suggests that hominids lost their hair because having it became inconvenient. Out in the open (or closed?) savannas of Africa, with the sun beating down on them, cooling off would be a problem. Remember, body hair serves as an insulator. Keeping unnecessary insulation means the body must expend more energy to thermoregulate.

The ultimate dilemma for any paleontologist The Ectoparasite Hypothesis At some point during any school year, a lice outbreak is bound to happen. Children come back itching and scratching at their scalp. I’m sure there is a certain mother out there that has thought about shaving off all their child’s hair just to avoid dealing with that potential risk. Mark Pagel and Walter Bodmer must have thought so too, as their hypothesis suggests that our ancestors lost all their body hair to avoid lice infestations. Hair is a great place for lice and other ectoparasites to hang out. They not only suck on their host’s blood, but also carry diseases. Having less hair makes one an unsuitable habitation for such creepy crawlies. Pagal and Bodmer suggest in their original paper that the trait started out being naturally selected for, as individuals with greater lice infestations might have died through disease, and the trait eventually got reinforced through sexual selection (Great! Darwin might not be wrong after all). The Naked Love Hypothesis Proposed by James Giles, this hypothesis suggests that human hairlessness increased a mother’s love for her child. Humans walking on our own two feet was a big moment in our evolution, but walking on two feet meant giving up those nifty prehensile feet that chimps and other great apes have. Young hominids wouldn’t have been able to cling to their mother’s fur without them, forcing the mothers to carry them. The more motivated and loving a mother was towards her child, the more likely she would have been to carry her child. A lack of hair, which increases the pleasure of skin-to-skin contact, might make the mother love her child more, and therefore make her more motivated to carry it, thus giving it a better chance of survival. The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis At some point around 6 to 8 mya, hominids had an aquatic phase. Fur made swimming difficult and the hair no longer served as a great insulator. Thus, evolution decided to get rid of it. Although paleontologists have found remains of hominids near water bodies, there is no evidence that they ever had a completely submerged existence. Of all the theories presented in this article, this one holds the least sway in the scientific community at large.

Where’s the evidence? None of these have provided a convincing answer, as there isn’t enough evidence to furnish that answer. Paleontologists don’t know what the hominid environment looked like at every step of evolution, nor how much of it looked like open grasslands (which every natural history documentary shows) versus thick tree cover. The indirect means we use, such as carbon dating, fossils and skeletal records, don’t give us the entire picture. In fact, different pieces of the same puzzle can contradict research done in the past. Today, hair is closely linked with our identity. The hairstyles we maintain and the decision to keep body hair or not is heavily influenced by culture. Humans now have fire, clothes, air conditioning, and pest control, allowing us to control our environment to a large degree. While we don’t know exactly how it came to be on our bodies in the way it is, hair has now become a cultural tool for self-expression!

https://ift.tt/32dAL1o . Foreign Articles November 03, 2019 at 09:56PM

0 notes

Photo

New mammal fossils reveal our hairy roots.

We usually associate mammals with the era since the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous, when they spread into the vacant ecological niches left behind by the demise of the dinosaurs. Truth is, they appeared a long time before they conquered the world, as far back as the late Triassic 212 million years ago when our distant ancestors the Mammaliaforms walked the world. They co-existed with the dinosaurs throughout most of their reign, the first saurians being about 30 million years older. Two new Jurassic fossils from China have sparked a debate on what makes a true mammal, and one had the oldest fossilised fur. They were published in this week's Nature. Both fossils are the most complete examples found of an order called Haramiyidae, until now only known from their teeth. It always seems like serendipity when two examples of something long sought after appear at the same time from different localities. Finding their exact location on the tree of life is proving problematic, and a debate has started on exactly how close to true mammals they are.

The first, illustrated in the picture, was squirrel sized, and had fur and a keratinous spur on his hind leg. The latter is remarkably similar to that of the male duck billed platypus, an egg laying primitive mammal found in Australia. The platypus's spur is poisonous, and the fossil example may well have been similar. It was found in a 165 million year old layer of volcanic ash that settled in a freshwater lake in Inner Mongolia.

Megaconus mammaliaformis's skeleton shows both reptilian and mammalian features, that lie on the hazy borderline between proto and true mammals, but proves that fur was already in existence back in the mid Jurassic. Its teeth reveal an omnivorous diet, showing it already had the mammalian opportunistic trait of trying to squeeze a living out of everything that can be nibbled. It lived by the lake shore and probably foraged at night, since he shared his habitat with Pterosaurs.

The second find, named Arboroharamiya, comes from northeastern China, and died about 160 million years ago. It had long digits, and possibly a prehensile tail, suggesting that it lived in trees. Its jaw consists of one bone, which is a mammalian trait, as reptiles have three further jaw bones that metamorphosed into our ear bones. The team controversially claim that it is a true mammal, and suggest that they were in existence as long ago as 200 million years.

One specimen is not enough to make such a definite statement, and the search is on for further finds to help us draw the line between 'proto' and 'true' mammals. More fossils are needed from this distant era before further clarity can be attained.

Loz Image credit: University of Chicago, Nature. http://www.theguardian.com/science/2013/aug/07/jurassic-squirrel-mammals-evolution-earth http://www.sciencerecorder.com/news/discovery-of-165-million-year-old-fossil-sheds-light-on-evolution-of-earliest-mammals/ http://www.nature.com/news/fossils-throw-mammalian-family-tree-into-disarray-1.13522 http://dinosaurs.about.com/od/otherprehistoriclife/a/earlymammals.htm Pay wall access, original paper: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v500/n7461/full/nature12429.html

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Analysis of Possible Synapsid (but non-mammalian) Pokemon

There are a number of pokemon that do not have a clear real life basis, but a suprising number line up atleast partially with long extinct Therapsids, especially Dicynodonts.

The Pokemon being discussed: Venusaur, Avalugg, Volcanion, Nidoqueen/Nidoking, Exploud, Rhyperior, Hydreigon, Haxorus, and Kommo-o.

Let’s start with a look at a dicynodont, specifically dicynodon.

Feature I’ve immediately taken note of: Single pair of long teeth that emerge from the mouth, 5 toes on front a back, and a short tail.

Feature 1: Teeth

Distinct canines are visible in all stages of Venusaur, and in all stages of Haxorus, they seem to have become some crazy display or fighting structure.

Nidorino and Nidorina stage of Nidoking/Nidoking clearly exhibit these canines, as do Rhyhorn and Rhydon, while Rhyperior gains a full set of teeth on the top, making canines unclear.

In both Exploud and Hydreigon, early stages do not exhibit distinct canines, but when the canines do show up on the later stages, they are accompanied by equally distinct teeth in the bottom jaw.

Kommo-o exhibits what could possibly be large canines, but they are not very clear.

Avalugg has teeny tiny little canines, which aren’t visible most of the time.

Distinct canines are not visible at all in any stage of Aggron, or the single stage of Volcanion.

Feature 2: Toes

Not even one has 5 toes on each foot and “hand”/front foot, except possibly Avalugg (which is why it isn’t mentioned below). Understandable, because it feels like more toes = less cartoony. The number that most species lean towards is actually 3 toes on each limb.

Pokemon with 3 toes/fingers front and back: Bulbasaur, Ivysaur, Venusaur, Volcanion, Nidorina, Nidorino, Fraxure, Haxorus, Lairon, Aggron, Exploud, and Jangmo-o

Pokemon with more than 3 fingers/toes in front, but 3 in back: Hakamo-o and Kommo-o

Pokemon with 3 fingers/toes in front, but less than 3 in back: Nidoking, Nidoqueen, Loudred, Rhydon, Rhyperior and Axew

Pokemon with less than 3 in front and back, but still clear toes: Nidoran (Both sexes) and Rhyhorn.

Pokemon without distinct toes: Bergmite, Aron, Whismur, Deino, and Hydreigon

Feature 3: Short Tail

Present in final evolution: Venusaur, Bergmite, Volcanion,

Not present in final evolution (too long)*: Kommo-o, Haxorus, Nidoking/Nidoqueen, Aggron, Loudred, Hydreigon, Rhyperior

*Note- Most of the Pokemon with long tails begin earlier stages with shorter tails.

Other features stand out on the Pokemon

First off- ears? As far as I know, thrapsids are not generally believed to have pinnae. This clearly clashes with many of the Pokemon previously listed. Perhaps the “ears” are made of bone such as in Estemnosuchus, or perhaps they are convergent with mammalian ears.

Second- fur. Very clearly visible in Hydreigon, possibly present around neck of Axew, and whiskers could be present in other species, but not actually shown b/c of the cartoony style of Pokemon. So is fur realistic to Therapsids?

Quoting wikipedia, “Recent studies on Permian coprolites showcase that hair was present in at least some therapsids.[6] Hair is by any means present in the docodont Castorocauda and haramiyidan Megaconus, and whiskers are inferred from therocephalians and cynodonts.”

So yes, fur is possible, and it’s possible it could develop fully in this imaginary sister group to mammals.

In conclusion:

Long canines are basal to the group, but many Pokemon have lost them. 5 toes front and back is the original trait but most Pokemon have ~3 on all legs. Avalugg still has the original amount, perhaps signifying that it split earlier from the group. Although short tails are ancestral, many species have regained longer tails. Many have ears, but they are not the same as mammalian ears, either bone display features, or possibly arrived convergently on the same design as mammals. Fur exists, but only a bit.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New proto-mammal fossil sheds light on evolution of earliest mammals

A newly discovered fossil reveals the evolutionary adaptations of a 165-million-year-old proto-mammal, providing evidence that traits such as hair and fur originated well before the rise of the first true mammals. The biological features of this ancient mammalian relative, named Megaconus mammaliaformis, are described by scientists from the University of Chicago in the Aug 8 issue of Nature....

Discovered in Inner Mongolia, China, Megaconus is one of the best-preserved fossils of the mammaliaform groups, which are long-extinct relatives to modern mammals. Dated to be around 165 million years old, Megaconus co-existed with feathered dinosaurs in the Jurassic era, nearly 100 million years before Tyrannosaurus rex roamed Earth.

Preserved in the fossil is a clear halo of guard hairs and underfur residue, making Megaconus only the second known pre-mammalian fossil with fur. It was found with sparse hairs around its abdomen, leading the team to hypothesize that it had a naked abdomen. On its heel, Megaconus possessed a long keratinous spur, which was possibly poisonous. Similar to spurs found on modern egg-laying mammals, such as male platypuses, the spur is evidence that this fossil was most likely a male member of its species....

A terrestrial animal about the size of a large ground squirrel, Megaconus was likely an omnivore, possessing clearly mammalian dental features and jaw hinge. Its molars had elaborate rows of cusps for chewing on plants, and some of its anterior teeth possessed large cusps that allowed it to eat insects and worms, perhaps even other small vertebrates. It had teeth with high crowns and fused roots similar to more modern, but unrelated, mammalian species such as rodents. Its high-crowned teeth also appeared to be slow growing like modern placental mammals. The skeleton of Megaconus, especially its hind-leg bones and finger claws, likely gave it a gait similar to modern armadillos, a previously unknown type of locomotion in mammaliaforms.

Luo and his team identified clearly non-mammalian characteristics as well. Its primitive middle ear, still attached to the jaw, was reptile-like. Its anklebones and vertebral column are also similar to the anatomy of previously known mammal-like reptiles. "We cannot say that Megaconus is our direct ancestor, but it certainly looks like a great-great-grand uncle 165 million years removed. These features are evidence of what our mammalian ancestor looked like during the Triassic-Jurassic transition," Luo said.

"Megaconus shows that many adaptations found in modern mammals were already tried by our distant, extinct relatives. In a sense, the three big branches of modern mammals are all accidental survivors among many other mammaliaform lineages that perished in extinction," Luo added.

The fossil, now in the collections in Paleontological Museum of Liaoning in China, was discovered and studied by an international team of paleontologists from Paleontological Museum of Liaoning, University of Bonn in Germany, and the University of Chicago.

#Megaconus mammaliaformis#Megaconus#Eleutherodontidae#Eleutherodontida#Haramiyida#Allotheria#Theriiformes#Mammalia#eleutherodontid#mammaliaform#Jurassic#fossil#extinct species#science

132 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In the Jurassic, squirrels* wielded venomous spurs.

________

*Not a true squirrel, but a squirrel-like mammal called Megaconus mammaliaformis from 160 million years ago in China.The poisonous spurs were on its hind legs. The fossil remains, just recently described, included impressions of its fur and folded skin.

Source: A Jurassic mammaliaform and the earliest mammalian evolutionary adaptations, Chang-Fu Zhou, Shaoyuan Wu, Thomas Martin, Zhe-Xi Luo. Nature.

Illustration by April M. Isch, University of Chicago

0 notes

Text

@thesumlax replied to your photo: Month of Mesozoic Mammals #16: So Many Gliders...

Has anybody ever checked if haramiyidans are even a natural group and not just some polyphyletic mess?

This paper found them to be potentially polyphyletic, with Megaconus placed in the mammaliaformes but other ‘haramiyidans’ grouped with the multituberculates as a new clade Euharamiyida.

It’s a huge taxonomic mess.

16 notes

·

View notes