#marsilio ficino health

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

@centaurianthropology

Making this a reblog reply due to length.

So this is a most kind offer! Though, I'm not sure we'll get anywhere with the scarcity of what is provided. Everything we have on his health is obnoxiously vague. I can't tell if there's an ongoing thing or if he was just prone to illness. He mentions being bed ridden at different times in various letters across the entirety of his life, so it wasn't an uncommon occurrence.

The mention of chronic stomach issues comes from Corsi's 16th century biography of Ficino wherein he writes:

His bodily constitution contained excessive blood which was mixed with a thin subtle red bile. His health was not at all settled, for he suffered very much from a weakness of the stomach, and although he was always cheerful and festive in company, yet it was thought that he sat long in solitude and became as if numb with melancholy. [...] Though he was often sick, and gravely so, and there were fears for his life, his health was restored through prayers of many friends on his behalf and he reached his sixty-sixth year. [...] Throughout his life he was content with simple clothes and possessions. He was neat rather than elegant and was strongly adverse to all extravagance. He obtained the necessities of life readily enough; otherwise he was sparing in food, but he did select the most excellent wines. For he was rather disposed towards wine, yet he never went away from parties drunk or fuddled, though often more cheerful. [...] Whether death came to Marsilio from old age or, as some maintain, from his stomach ailment, I have not been able to discover.

Given the humour theory and the role wine plays in that, it is not surprising he viewed good wine as important to maintaining his health. If his humours ran sanguine/wet and hot, then dry red wine would be seen as a balancing effect.

But what is meant by stomach troubles is left unstated. In one of his letters in 1474 Marsilio mentions fever and inconstancy, which could have been his stomach ailment? Also could have been unrelated or a compounded issue:

I have not yet finished my book On the Christian Religion, Francesco, because during August, while I was still correcting it, I caught a fever a diarrhoea. [...] Listen to what has happened to me during this illness. There were times when I became so weak, Marescalchi, that I almost despaired of recovery. I then turned over in my mind those great works I have often read during the last thirty years, to see if anything occurred to me that could ease a sick heart. Except for the Platonic authors, the writings of men did not help at all, but the works of Christ brought much more comfort than the words of philosophers. What is more, I offered prayers to the divine Mary and begged for some sign of recovery. I felt some relief immediately, and in dreams received a clear indication of recovery. [...] A few days later, with a similar prayer, I was free from the heat of my urine. [...]

The heat from the urine I assume could be anything from dehydration (especially if he was feverish and had diarrhoea) to UTI to something else entirely.

The vague references are all the same and this undated letter to Giovanni (written pre-March 20, 1478 as Marsilio's father is alive) captures the broad sentiment:

The care of my own sick body and that of my father is one burden for me. Your absence is another. Both must be borne with equanimity, lest they become burdensome through impatience. But if you have any humanity, do not add to my double burden yet a third, too great a burden if you do not return my books. [...]

(Marsilio, spending his life asking for people to return his books to him.)

In October 1468 we know he fell ill for a few weeks as he writes to Giovani: "[...] In the evening I became sick and am not yet recovered." But no greater details are provided.

The 1474 illness, which is mentioned above, was so bad that he couldn't write for a time. As he notes to Lorenzo de' Medici in a letter:

As soon as my hand could lift a pen, I considered it wrong to write to anyone else before writing to my sole patron. [...]

In a reply to this letter, Lorenzo says:

I am very glad indeed that your former health has been restored. I should be even more glad if, through attending to your letter, I could recover my former health of mind. [...] Once more I rejoice both for your sake and mine that immortal God has restored you to us safe and sound. I have recieved as much of a reminder as you by this danger to your life. [...] I mean thus to profit more from both you and time; from time because it has no tomorrow, from you because you are a man for whom no moment is free from the dread of death. Farewell and take care of your health.

Tendency towards exaggeration aside, I do think whatever happened in 1474 was quite serious and seemed to have lasted for at least two to three months. Though Lorenzo's "you are a man for whom no moment is free from the dread of death" I read as an allusion to ongoing/long term illness of some form. Momento mori, of course, but if that were the case he'd have included himself.

Two years later, 1476, he writes to Giovanni:

Because I am now forced to spend long periods in bed, I have been considering a remedy against the tedium of continuing confinement. The first, indeed the only one who could relieve the tedium threatening me, came to mind; my Cavalcanti, my especial doctor. And so welcome again, my health giver, expeller of my evils, preserver of my goods. [...]

In 1480 Marsilio writes to Bernardo Bembo:

After a long stay in the country, I was compelled at last by important business to return to the fever-ridden city. Here, on the 1st of July, cruel Mars hurled twin flames upon me, bringing me suddenly to the point of death. [...] Since I knew, however, that the frail state of my body could not bear two fevers, especially in July, nor the necessary help of the doctors, "I lifted up mine eyes unto the hills, from whnce cometh my help. My help cometh even from the Lord, who hath made heaven and earth." On the instant, contrary to all physical explanation, through the flow of divine mercy, a breath from heaven blew into me and straightway extinguished both flames even as they grew. [...]

The footnotes to this letter speculate that he might have been suffering from malaria "in which, on every third day, two crises occur." Not sure if that is the case, but that's what is noted.

-----

I'm not sure if you're able to make anything out of any of that? It's frustrating and I wish to go back in time and ask Marsilio to detail to me every symptom he ever had, I'm fairly certain he would do so gleefully.

oh! oh! Marsilio gets to complain of his health! Marsilio has a new audience for medical talk! Marsilio is in heaven. Marsilio is in heaven for a thousand years.

What I want to know is what Marsilio suffered from in terms of his chronic illness. It was potential stomach related - but also maybe something more? It's always so vaguely discussed and I want to know more~~~

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Orphic Hymn to Jupiter: Empower Your Jovial Prayers & Magic

Jupiter, known in traditional astrology as the Greater Benefic, would be an excellent place for many people to start building relationships with planetary spirits or beginning a devotional practice. The Renaissance magician-physician Marsilio Ficino advised as a general rule for people “to increase the influence of the Sun, of Jupiter, or of Venus.” Invocations, prayers, and offerings to a planetary spirit can help you attune to and come into rhythm with that planet. There are many ways to pray to or invoke a planetary spirit, including simply speaking from the heart, but a natural place to start is one of the most common and accessible prayers to Jupiter: The Orphic Hymn to Jupiter.

The Orphic Hymn to Jupiter

The Orphic Hymns are a collection of Hellenistic religious poems that were involved in the practices of Orphism, a mystery religion centered around the mythical figure Orpheus. The infamous magician Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa wrote that “nothing is more effective in natural magic” than the hymns of Orpheus.

The Orphic Hymn to Jupiter exemplifies one approach to planetary prayer, which is to regale the spirit with praise, listing many noble qualities and superlatives associated with that spirit. The traditional Orphic Hymn to Jupiter (Jove) reads as follows:

O Jove much-honored, Jove supremely great, to thee our holy rites we consecrate, Our prayers and expiations, king divine, for all things round thy head exalted shine. The earth is thine, and mountains swelling high, the sea profound, and all within the sky. Saturnian king, descending from above, magnanimous, commanding, sceptered Jove; All-parent, principle and end of all, whose power almighty, shakes this earthly ball; Even Nature trembles at thy mighty nod, loud-sounding, armed with lightning, thundering God. Source of abundance, purifying king, O various-formed from whom all natures spring; Propitious hear my prayer, give blameless health, with peace divine, and necessary wealth.

Throne of Jupiter by Talon Abraxas

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

At the shrines of Apollo, a healing took place. In a state of trance it is said that the initiate heard the music of the spheres and was made whole. ‘It is hardly surprising’, says Ficino, ‘that both music and medicine are often practiced by the same men’, since they are united in the power of the one god. Ficino found his vocation as a healer confirmed in the words of Orpheus. ‘Orpheus, in his book of hymns’, he tells us, ‘asserts that Apollo, by his vital rays, bestows health and life on all and drives away disease. By the sounding strings, that is, by their vibrations and power, he regulates everything; by the lowest string, winter; by the highest string, summer; and by the middle strings, he brings in spring and autumn.’ Apollo’s lyre thus becomes a model for the harmony of the whole cosmos, uniting the physical order with the spiritual, the body with the soul. In revealing to the listener or player the harmonic proportions in his own soul, through number and pitch, the lyre is both a visual and audible image of a secret order to be found beyond the level of sense-perception, an articulation of the hidden relationships between different levels of reality.

-From “Orpheus Redivivus: The Musical Language of Marsilio Ficino,” by Angela Voss

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marsilio Ficono: 'intellectuals require a special regimen in order to maintain their health because they are often beset by an abundance of black bile and therefore given to melancholy'¹

Academia: giving students depression since the fifteenth century

¹ Marsilio Ficino, De triplici vita

0 notes

Note

2 and 13 for fic asks? 💙

^_^! Thank you for the asks, my dear friend! <3

2) Who is the easiest character for you to write?

Dev! xD Because he’s a blank slate and I can do what I want with him!

Just kidding!

Honestly, probably Baz (though I did have the most fun writing Penny!). I like that I get to use my flowery-way-of-writing when writing him.

Also, I have a lot of fun writing Baz, hes a fun character to write for!

I think if Simon was the book-smart type-of-person, I could probably nail writing in his POV, because I really connect with him (especially with the trauma-related mental health)

I kinda want to write more Penny-POV and Agatha POV, I wanna try stretching my writing skills by writing different characters

13) How do you come up with titles?

Most of the time, it’s song lyrics.

Good God, I just checked my fic list, and out of 20 fics I’ve written, 13 are song-lyrics!

Ok, let me look at the ones that aren’t song fics.

For the Bat-Baz fics, I wanted to put in clever sayings that were Bat-related like “blind as a bat”. For the second Bat-Baz fic, I just went all out ridiculous and threw in the Bazaloo as a nod to Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo.

For “Hush Love”, I took a quote directly from the fic itself. It’s the mantra that Simon and Baz say to each to bring them back from the night terrors they both have. It’s both tender, and grounding, because it’s something they both came up with to let the othe know that they’re safe and that they’ll be ok.

For “Keep Calm and Save a Unicorn” - I wanted to be clever and use the Keep On and Carry on slogan that everyone was using at one point. I added the Unicorn, because Agatha takes care of magical creatures in that fic and Unicorns are cool! (fun fact, I wrote that fic for @fight-surrender , who works with animals AND her AO3 icon is from The Last Unicorn... so that was cool to!)

For “Everything’s Better with a Little Bit of HOLO!” I just paraphrased a quote from SimplyNailogical, because the fic is about Simon being obsessed with holographic (HOLO) nail polish, when he uses her nail polish brand.

“Love is a Dream of Beauty” is a quote from a famous Renaissance philosopher, Marsilio Ficino. This fic is a set up to a Renaissance fic, I’ve been working on. I wanted to use a quote from a famous person of the time.

I don’t know where I came up with the title for my Baz Headconon list. I was REALLY sleep deprived and starting a new mental health plan thing, so my brain was foggy around that time. I think I was making a joke?

Merci!!

From THIS Ask Meme!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

corpse medicines -- medical cannibalism and vampirism (x)

blood, in varying forms

While epileptics of ancient Rome drank the blood of slain gladiators, the beverage found particular favor as a health tonic during the Renaissance. The blood was typically harvested from the freshly dead, but could also be taken from the living. Such medicinal vampirism had no shortage of adherents: Marsilio Ficino, a highly respected fifteenth-century Italian scholar and priest, said that elderly people hoping to regain the spring in their step should “suck the blood of an adolescent” who was “clean, happy, temperate, and whose blood is excellent but perhaps a little excessive.” Another popular remedy, sometimes attributed to Saint Albertus Magnus, involved distilling the blood of a healthy man as if it were rose water; the result was said to cure “any disease of the body,” and “a small quantity…restoreth them that have lost all their strength,” according to one 1559 text. By the 1650s there was a general belief that drinking fresh, hot blood from the recently deceased would cure epilepsy, as well as help with consumption. Meanwhile, dried and powdered blood was recommended for nosebleeds or sprinkled on wounds to stop bleeding.

If fresh or powdered blood proved somehow inconvenient, one could also follow the recipe for blood jam given by a Franciscan apothecary in 1679.

mumia, or, mummy--a “pitch-like substance, produced in Egyptian corpses by the arts of mummification”

In the late sixteenth century, surgeon Ambroise Paré claimed it was “the very first and last medicine of almost all our practitioners” against bruising. Mummy was a significant commodity by the eighteenth century, taken in tinctures for bleeding or used in plasters against venomous bites or joint pain—so significant, in fact, that there was also a thriving trade in fraudulent mummy made from the poor, criminals, or animals.

fat

It was rubbed on the skin to ease the pains of gout and taken internally (in powdered form) to help with bleeding or bruising. It could also be used in the form of plasters. Sir Theodore Turquet de Mayerne—physician to several English and French kings as well as to Oliver Cromwell—recommended a pain-killing plaster made of hemlock, opium, and human fat.

the skull

The seventeenth-century English physician John French offered at least two recipes for distilling skulls into spirits, one of which he said not only “helps the falling sickness, gout, dropsy” and stomach troubles but also was “a kind of panacea.” (The other recipe was better for “epilepsy, convulsions, all fevers putrid or pestilential, passions of the heart.”) [...] The remedy was popular for a variety of complaints and seems to have often been mixed into wine or chocolate. [...] Moss that had grown on skulls, known as usnea, was thought to be especially powerful; it was pushed up the nose to stop nosebleeds.

#what is up my dudes it is 2:08am and I am reading. some. Shite#if anyone wants the recipe for blood jam hmu it's education time#medical#my upload

317 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good health, honored guest! Good health to any of you who come to our doorstep hungry for health! I beg you, the guest who is hungry, to see how hospitable I am. For no sooner had you entered than I asked about your health. Anticipating your health, I bid you good health as soon as I saw you. When you entered here, unknown to me, I received you with great pleasure. If you follow my customs, I will give you the health promised (if God allows it).

You have happened upon a host who is friendly to everyone, and full of love toward you. If you bring a similar love, and if you have put aside all your hate, what vital medicines will you find here! For it was love and the pleasure of your parents that gave you life. Hatred and sorrow, on the other hand, destroy life. Any of you who is suffering from the sorrow of hate, then, there is no place here for you, no vital medicine left that will ever help you. Therefore, I am speaking to you not so much as a host, but as a friend.

The laboratory of your Marsilio is somewhat larger than just the space you see bounded here. For not only is it enclosed in the following book, but in the two preceding books, too. All of it is offered as a kind of medicine for the powers of life, so that your life will be healthy and long. It is based here and there on the work of doctors who are helpful on planetary matters. Our laboratory here, our antidotes, drugs, poultices, ointments and remedies, offer different things to different types of people. If you do not like some of these things, just put them aside, lest you reject the rest because of a few.

Marsilio Ficino, Libri de Vita

1 note

·

View note

Text

On Depression

I put this on Facebook yesterday out of the sense that, on balance, ‘Mental Health Awareness’ is a good thing. I now put it here, lightly edited, out of a sense that awareness should be, at least in some way, public-facing. It is unusually personal, and although I don’t like the insipid personalisation of, well, everything, I thought it forgivable in this instance. == It is Mental Health Awareness week. These festivals of mass disclosure are usually a turn-off for me – I don’t think disclosure is an intrinsic good, and the drive for constant public confession of one’s every constant fluctuation can itself be pathological. (I wonder who determines these weeks, whether they’re aware of the paltriness or absurdity of it placed against the immensity of the problem.) Doubtless some of that is an aversion on my part to not appearing in control, to appearing excessive or self-involved, to hatred of pity or condescension – but I’m also convinced, despite the piety of the sentiment, that talking about these things is a prerequisite for them changing.

So: I have a depressive disorder. That phrasing tends to hide a lot of things under a couple of words, so here’s some specificity: what this means in practice these days is that a couple of times a year, for a week or two, I am gripped by the most painful and destructive forms of abjection, hopelessness and worthlessness. These episodes are no longer as destructive as they used to be – I know how to deal with them better – and if you were to see me in the middle of one, you might notice (if you were sharp) that I hadn’t shaved as frequently as I might, or I’m wearing the same jumper twice, or my concentration seems slightly off, but not much more than that. What is happening internally is quite different, and quite wretched. Yet these episodes pass – always, eventually, though each time I never quite believe they will. The rest of the time, I live with the kind of psyche predisposed to those episodes, with those predispositions more or less dominant.

Sometimes, people argue that mental illness should be no more invested with significance than a broken leg or a flapping atrial valve, subject to the same kinds of treatment and recovery. I think treatment is good, but also crude, that our understanding of the psyche is still primitive. Without severing physical and mental conditions (the two exist for many people in a kind of circuit), the internal geography of depression - at least - is bewildering, shifting, corrosive, and at the same time without the novelty any of those things suggest. It is terrifying but also boring. It transforms one’s successes into failures, or achievements in charlatanism. One is convinced of one’s own talentlessness, loathsomeness, unworthiness. Kindness is undeserved, or marred by suspicion, at the same time a merciless and ridiculous lability obtains. Description could multiply endlessly: its states of non-action, bound in secret knots with excess, overwork, intensity. Its cynicism. Its insomniac wakefulness. You will note I use the neutral third person – just to talk about the state has a kind of miasma, it requires careful handling.

This is on my mind because I have recently come out of just such an episode.

I struggled for a long time against making ‘depression’ any part of my self-conception, still less my ‘identity’. It is so debilitating and so humiliating that the thought of being defined by it in any way appalls me. I’ve made more peace with it than I once thought I might – in part because I understand just how deep a part of me it is – but my hostility remains. I think the internet is bad for this stuff, both in the rewards it gives to maladaptive coping strategies, and its barrage of images and outrages, tempests and diverting mini-catharses.

‘Mental health is political’. Like most righteous clichés, it is both true and vacuous. It is political insofar as it is in substantial part an effect of our social structure and collective choices; it is political insofar as its treatment, reception and ‘mentionability’ are matters of contestation; assertion of its political nature matters insofar as it denaturalises and socialises what can too often be made a matter of personal culpability. The question is where one goes next: like most of these political clichés, it is both a challenge to the definition of the political (‘it’s bigger than you think’), and the protasis for a syllogism ending ‘that’s why we need socialism’. True, as far as it goes, but insufficient.

(There is a real scission between the serious left-wing work done on mental health, psychiatry and the connections between politics and the psyche and some of what passes for a ‘politics of mental health’ on the internet, especially where the latter is a cobbled-together synthesis of ‘self-care’ – a term now so far wrenched from its roots – with freedom from criticism, praise of cruelty and brutality and the practice thereof, a politics of credulous validation – none of which gets at the difficulty of it, the danger of it, the terrible fact that we so rarely know what the right thing is or what’s good for us… But that’s a digression.)

However social its roots or common its injuries, depression builds its alphabet out of our personal wounds; its canon is unique. I can’t give the kind of tips you might put on an inspirational Instagram account, or the nostrums you might get in an NHS So You Have Depression pamphlet. If I tell you some poetry, walking, nature, eating well helps sometimes, well, it’s true, even if it feels sometimes like tapdancing over the abyss. (And it’s only when talking about reading materials for depressives we use the absurd criterion ‘helpful’, as if our critical measure of what literature can do to us should be in tones of therapeutic beige.) I hate the literature of the self, for the most part – even that Kay Redfield Jamison stuff, once trendy, doesn’t sit well with me – but the way Freud and Klein think about the question (i.e. the big question – why does something that should seek pleasure seem to seek out pain?) useful, even if their conclusions are less so. Otherwise, the explorations I like are what you might expect: the wound of Philoctetes; Job, Ecclesiastes, Jonah; the agonised saints; Burton’s Anatomy, and much of the literature of the great period of melancholy in English, surrounded by political upheaval, intellectual and spiritual catastrophe. Especially this latter is marked by a sense that the soul and the mind have depths and capacities which can be truly monstrous, or which might overcome the narrow brightness of conscious reason. Recently I have been reading Marsilio Ficino, the great Florentine Platonist, classicist, homosexual and melancholic. He casts things in astrological terms – his alphabet – and talks about Saturn and the contemplative, the great and dangerous malefic. What is so sweet about him is that he warns of the dangers of melancholy from the inside – fully Saturnine – commends the wearing of bright colours, music, Sunny and Jupiterian things, while also knowing how deeply (and perhaps permanently) the mark of Saturn sits with him. It is something from another age, and yet not so much, not at all.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beating Insomnia

Distract yourself with meaningless mental lists. I fly a lot, so I imagine I have my own private jet and how would I arrange the furniture on it. If you're someone who likes going to music festivals, what would your lineup be? -- Neil Stanley, sleep expert

Thinking about sleep and wishing for it to happen is a recipe for staying awake. This is where paradoxical thinking comes in. If you give yourself the paradoxical instruction to stay awake instead, you'll be more likely to fall asleep. -- Colin Espie, professor of sleep medicine at the University of Oxford

"If 20 minutes has gone by as the mind races and is unable to relax back to sleep, it's best to get out of bed. Without looking at your phone or any other screen devices, go to another dimly lit room where you keep a notebook. Write down the thoughts that are keeping you awake. Finish with the words, 'It can wait until tomorrow.' Then, go back to bed, focus on the breath, and mindfully relax into those words, giving yourself permission to yield to sleep." -- Jenni June, sleep consultant

Write down whatever's freaking you out. You can then see which worries are hypothetical (i.e., what if I make a mistake at work and lose my job) or 'real' worries (e.g., I made a mistake and have lost my job). For the real worries you can then make an action plan/problem-solve and for the hypothetical ones, learn to let them go. -- Kathryn Pinkham, National Health Services insomnia specialist

"Deep breathing ... acts as a powerful distraction technique, particularly if paired with counting. You want to aim to breathe out for longer than you breathe in, and pause after breathing in and out; so you might choose to count for three when you breathe in, then pause and count to five when you breathe out, then pause. -- Christabel Majendie, sleep therapist

After the evening meal, eat lettuce, drink wine, and rub an ointment made of the oil of violets or camphor on the temples. Dissolve a mixture of poppy seeds, lettuce seeds, balsam, saffron, and sugar and cook it in poppy juice. Then listen to pleasant music and lie down on a bed covered with the leaves of fresh, cool plants. -- Marsilio Ficino, 15th-century philosopher (x)

Put some blood-sucking leeches behind your ears. When they bore holes in the skin, pull them out and place a grain of opium in each hole. -- André du Laurens, 16th-century French physician

Kill a sheep, and then press its steaming lungs on either side of the head. Keep the lungs in place as long as they remain warm. -- Ambroise Paré, 16th-century French surgeon

1 note

·

View note

Text

I was thinking this! it definitely aligns with Ficino's broad views that there is natural alignment between spiritual and practical practices.

Ficino included what we would call "mental health" under the auspices of medical care that priests and doctors should cover. Half his medical writing in De Vita is about creating a healthy routine for yourself. So, make sure you get enough sleep, take walks every day, only work for two hours at a time then take a break for a bit before returning, attend to your appearance/daily ablutions etc.

His advice was all stuff he did himself, and I suspect his rather rigorous personal schedule was born from a need to keep some semblance of control in his life since his mental health was, famously, absolute dog-shit.

In his account of the exorcism he refers to the demon as being Saturnine in its qualities, hence why he applied Jovial things to cast it away since Jupiter is in opposition to Saturn. And while I don't doubt that was he true interpretation of the event, I do like how neat a parallel it is to his own mental health and views on how to address those challenges.

A sort of subconscious understanding that possession is as much a symptom of a bad home (however that might look in each situation) than anything entirely preternatural.

Ok, so I tracked down the exorcism story - and based on my very (very) rough translation basically what happened is that in Florence in October 1493, "in an ancient and dilapidated house of a Galilean family," it was discovered that for the previous two months a demon had "infested" the domestics.

Our main man Ficino is called in to deal with the problem. He talks to the servants, putting arguments to them (basically, he questions them to try and figure out who is possessing them). Through this, he determines that the spirit who had possessed them, and the house more broadly, was one that thrived in dark, unclean spaces. So the run-down qualities of the house they were in was feeding the energy of the demon. There's some mention that there may have been telekinetic abilities as shears/knives are noted have been moved on their own.

Ficino tells the family that aside from the usual rites of exorcism and prayers, the "whole house should be cleansed of dirt" and filled with selected, holy scents (particularly those associated with the planet Jupiter and the sun), given a fresh paint job and "illuminated and decorated so that" it would no longer be amenable to this demon that preferred darkness and "filth."

The demon, of course, was not keen on the change of plans per his living arrangement and argued back. Ficino subjected it to prayers, of course, but also "jovial things" (i.e., music, scents, and items associated with Jupiter). Eventually the demon backed off and left the family and their servants alone.

So, Ficino is like "yes, we need the normal Church rites of exorcism, but also my astrological music and natural magic."

Savonarola: pretty sure that's Not approved by the Church.

Ficino: It works, though, so maybe don't worry about it?

I couldn't find (yet) an account of chucking the demon out of his shoemaker's house.

#I hesitate to refer to anything here as metaphor or symbolic because for Ficino and his contemporaries#possession was very literal and real#it's us all looking at it from a secular lens going: yeah the possession is untreated mental health issues or an abusive situation#or whatever else might be happening in that case.#also there were (and are) very strict guidelines to follow to determine if a possession is real or not and when Fic. refers to questioning#the servants - this is what he's on about. He is making sure they exhibit all the signs#so they can speak in tongues they know things they can't possibly ever know they exhibit displays of supernatural strength etc etc#I will say that I like that he was able to do exorcisms#not all priests are qualified#marsilio blogging#marsilio ficino

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

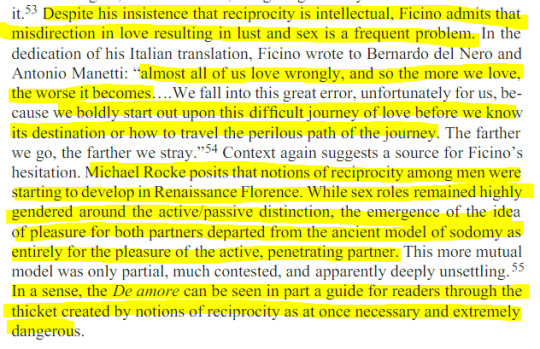

so much on Ficino & Plato & Sex

your daily Marsilio blogging continues, this time with the gentle reminder of the deep misogyny of most homoerotic anything in the medieval and early modern period (among other times as well).

At the same time, I appreciate Marsilio being like: Fuck this, we can do the Petrarchan model of Ideal Love too. Just watch me and Giovanni yearn for twenty years.

I do appreciate that in the whole of Ficino's writing he rarely, if ever, refers to sex between men as sinful. He uses terms of disgraceful, filthy, worthy of disgust, ugliness etc. but he uses those terms equally for heterosexual sex conducted for pleasure alone with no intention of making the babies. Corporality on the whole - in all its forms - is the problem. (And the contemporary medical hang-ups around the expulsion of semen aside.)

But it's still not sinful, it just makes it harder to climb the ladder of love to salvation. Some might think this a small thing (he still reads it as bad!) but there's a huge gulf of difference between a priest from 1478 saying X is disgraceful but never using the language of sin around it.

Granted, Ficino doesn't harp too much on sin in general. I would be very curious to go back in time, get him a little wine drunk, and ask him his actual, not-Church approved views.

Ficino loves trying to reconcile everything through Plato. Marsilio "What if We Applied Plato to This Situation??" Ficino.

The desire/beauty thing - you can just see his struggle in trying to make it all work and never quite succeeding. It's one of the many things he and Pico debated with great animation. Pico was anti-the physical desire part of Ficino's formula while Ficino believed salvation/finding Philosophic Truth (i.e., God) required it.

I do really love Ficino's broadly positive read on humanity. He always goes in with a: People Are Good approach to a situation.

I love this little caveats he gives in his writings. The bit: "Love, even when mixed with an inderior appetite [for sex], does not cease meanwhile to raise the soul as far as it is able."

Giovanni having a panic about the state of their souls as they lie about in the grass and Ficino thinking fast on how to assuage him. "Umm, look, this isn't ideal, and we really should try harder to resist. But ... uh... Love is Good. Right? Our Love is Good and holds no Evil, correct?'

Giovanni, 'Yes, that is correct.'

Ficino, 'Great, so because our Love is Good and our Souls naturally desire Truth and Love is always working to help raise our souls up to Truth - even when we uhhhhh slip up, shall we say--'

Giovanni, 'We purposefully went into a remote field to commit sodomy. This wasn't an accidental slip up, Marsilio. You even checked to make sure you had time enough after this to confess and seek absolution so you can say mass on Sunday.'

Ficino, 'Slipped up. Could have happened to anyone. Anyway, even when that happens Love is still raising our souls up as far as it is able. So what I'm saying is, don't worry about it.'

the knots this man will tie himself in to try and make it ok to accidentally, whoopsie daisy, sleep with men. That full quote from him on how homosexual consorting (sex, that is what he means quite literally) is part of spiritual procreation is really something else.

I also think the caveat he includes of "of course, naturally, when you're horny you should go to your wife to make sure you're doing sex Properly" is doing a lot of interesting work there.

"Giovanni and I loving each other is necessary for OUR PHYSICAL HEALTH OK??"

Technically, he's not wrong. In the sense that being able to openly and honestly love/be loved by who it is you desire - regardless their gender - is incredibly important to mental health which impacts physical health.

mess! mess! mess!

this is super interesting. That Ficino was attempting to figure out how to guide people through reciprocal love in a world where that wasn't normal to navigate.

All of Ficino's back and forth on sex, desire, beauty, love is just so telling of how much he wanted to resolve the issue and how knotted everything was for him (and he wasn't alone, obviously).

--

ok I'm done inundating everyone for now.

#marsilio ficino#marsilio blogging#neoplatonism#early modern history#15th century#giovanni cavalcanti#renaissance italy#renaissance florence#Marsilio sourcing

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is a phenomenal letter and I love it. Ficino writing to Giovanni the imagined reply Giovanni owes him?? You are messy, sir! So so messy!

It’s undated but I put it between 1476-78. Somewhere in there.

The above is obviously one of their joint letters. I would love to know their writing/editing process. Did Marsilio write first then Giovanni edit? Did they sit down and draft it out?

There’s something about the line “overwhelmed by bitterness long and real” that makes me think it’s a Giovanni Line. I don’t know why but there’s something in the cadence that feels off, compared to the rest of Marsilio’s usual writing. Could be a translation issue, of course, but idk. Just feels Cavalcantian rather than Ficinian.

The above is an excerpt from a fucking HELLISH chapter of De Amore simply because of the sheer anguish Ficino manages to convey. It’s just so. utterly. heartbreaking.

Ficino’s mental health crises comes out sometimes in De Amore and this is one of those times (plus repressed queerness &c.). Our tiny gay magician priest musician philosopher was not doing ok!!

#Marsilio Ficino#MY HEART#Giovanni Cavalcanti#sometimes I read parts of De Amore and think about Marsilio’s love for Cavalcanti and cry#history#15th century#early modern Florence#Renaissance Florence#Marsilio blogging#Marsilio sourcing

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok, ok, I would appreciate thoughts.

Most of this context setting stuff most will know, but I'm including it anyway. Question is down below, bolded:

So, The Magi is to take place in late 1478, I'm trying to determine what Ficino and Cavalcanti's relationship would have looked like at that time.

Ficino has been a priest for four years, now, as he is 44 in '78 and was ordained in '74 when he was 40 (an unusually late time in life to turn priest). Giovanni is 34. Ficino wrote in a letter kept in the front of the original manuscript of De Amore that he had lived 34 years without knowing true love until he met Giovanni, so he, at least, has been in love with the man for ten years at this point. They've known each other for longer, though.

(Corsi says they've known each other since Gio was 3, but that's apocryphal and rings hollow to me. It seems more likely they first met when Gio was 18/19/20-ish since Domenico Galletti, the man tutoring Gio, used to tutor Ficino and they had remained friends.)

The problem is that Giovanni is such a ghost.

In 1478 through 79 and even into 80, they were living off and on with each other, at least based on the larger than normal volume of joint letters sent from both of them. We also know Ficino wrote quite a bit of Platonic Theology, among a few other works, at Rignano at this time, which is where Cavalcanti's country home was located.

Then there are joint letters from both Celle and Careggi - so Giovanni was staying with Ficino at the house/smallhold that Cosimo gifted him in Careggi and also the family farm down in Celle.

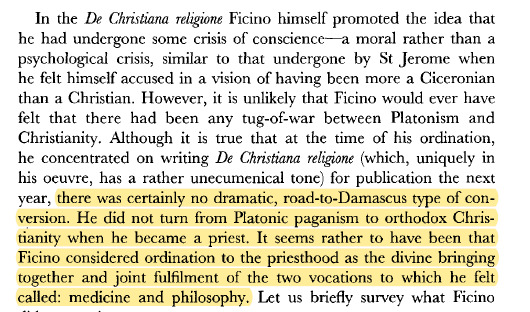

Ficino's calling to the priesthood was earnest and true, I believe. I also agree with Peter Serracino-Inglott in his essay "Ficino the Priest" where he argues that Ficino would have viewed priesthood as the natural culmination of his being both doctor and philosopher, as well as a means to try and understand himself/doctor heal thyself sort of thing (in terms of his mental health, at least).

From the essay:

And Ficino took his calling very seriously. He attended to the more clerical duties, the boring chore-like ones that most priests would pass off onto others. No, those Ficino would see to himself. It speaks to a quality of his person.

Now, Giovanni was a statesman and politician. Second son of four boys, he was born to an old, aristocratic family which had its own political ups and downs. They had been exiled due to their Anti-Medician sympathies, yet Cosimo was the one who refranchised them and welcomed them back into the Florentine political scene.

Giovanni doesn't really kick start his career until his 40s, not unusual in Florence at that time. Those in government felt men in their 20s and early 30s were all idiots and generally not to be trusted with more senior, serious positions in government (Medici exceptionalism aside). Those in government weren't, necessarily, wrong about men in their 20s and early 30s. Who isn't an idiot at 25?

So in 1478, at 34, Giovanni wasn't yet holding senior or strenuous offices in government and therefore had more free-time on his hands. He was clearly palling around with the Platonic-circle of the Florentine humanist scene since Landino and Poliziano both consider him to be a good friend and a clear, regular attendee to whatever soirees and Platonic parties/dinners that were being held. He doesn't seem to have been close to Luigi Pulci and his crew, since Marsilio complains to Giovanni about how much he hates Gigi and the progress of the Great War Over Lorenzo's Patronage.

Around this time as well, we know he had his third daughter (he had four in total, no sons). Unclear if there was a wife or if it was with a mistress. I suspect a wife, since he was keen for a son which implies the boy would have been a proper heir.

I do not get the sense that he was a particularly devoted or besotted father or husband/lover. Ficino mentions the third daughter's birth and is basically like "a) why didn't you tell me? and b) I know you wanted a son but rejoice regardless because children are good and daughters are gifts from god too" (yay 15th century misogyny)

We have letters from Ficino to friends who were clearly much more devoted fathers and husbands and he will make mention of his friend's children and such. He would reflect the level of care and love that person shows to their family back at them. This doesn't happen with Giovanni.

Granted, Ficino was clearly an over-thinker and probably prone to being nervous about whether or not Giovanni loved him. There's a sense of insecurity that comes through the letters.

The one letter from Gio to Ficino that Ficino printed is very even in tone, very calming. I think Giovanni was the grounded, earthy person to Ficino's madness.

We also know that Giovanni borrowed books regularly from Ficino and seemed infamous in not returning them in a reasonable time-frame. Ficino wrote his more dangerous political complaints to Giovanni about Lorenzo and literally no one else.

(I suspect he would verbally complain to Bernardo Bembo, but he didn't write to him on it.)

Ficino also wrote to Cavalcanti about his medical problems more than anyone else. I think the other person who gets the regular Marsilio Ficino Health Updates is Bernardo Bembo, who was one of his favourite correspondents/friends after Giovanni so that makes sense.

Giovanni knew Ficino well, was the one who seemed to be able to leverage Marsilio out of his deeper depressions. He also seemed perfectly comfortable pushing back on Ficino - something we see in the one letter from him that is printed and also something Ficino references in letters to Gio.

He was not a consistent correspondent. Was this just with Ficino or was it an across-the-board thing? Maybe he just wasn't a letter writer. If it's just Ficino was it because Ficino wrote 500 letters a minute to people or because there was a lack of warmth or, perhaps, too many feelings? (Thinking of Darcy here, if I felt less I would speak more.)

That said, he clearly expected regular correspondence from Ficino and would pester him when he didn't get his due.

He seemed to have had a bit of a temper and maybe a personality that bore grudges and grievances--maybe for himself, maybe just on behalf of others. Marsilio wrote him that big long letter on why Vengeance is Bad Giovanni, Tell Your Cousin to Calm Down.

That said, Ficino valued his opinion and when he wrote letters to people that might have been a bit savage he asked Giovanni to vet them and make sure he wasn't about to piss someone off too much. So Gio had political acuity and a sense of tact that Ficino might have been aware was not his strongest suit, personally. Giovanni also turned to him for advice, so it was a mutual thing of turning to each other when they know the other would have valuable insight.

Giovanni was a bit of a sportsman, it seems. Certainly jousted and did sword play. So he was classically trained as a landed gentleman in that regard alongside his stellar education.

He might have been poetic. We know he was a good public speaker, this is mentioned by people other than Ficino. He is just as well read as Ficino on all things Platonic and Greek and esoteric. Ficino references the conversations they have and the topics are all over the place. Unclear if he was musical or not. Ficino doesn't mention it, and so I suspect not. If Cavalcanti had played an instrument Ficino would be in seventh heaven about it.

-------

All of this leads me to: What was their relationship??

Was it physical or not? Was it returned in equal measure or not? Were they an old married couple or not? Did they go back/forth on these things?

I can see Ficino being very conflicted - not that their love was bad or anything (Ficino did not believe any love that was good in intent could ever be bad. He was "love is love" before that was a thing), but wanting that pure Platonic, non-physical love since he thought that was the ideal for all forms of love. Man to man, woman to woman, man to woman - the ideal love was non-physical.

At the same time, Ficino thought physical desire was helpful in understanding Beauty which would lead a man to Truth then to God. So he really was trying to reconcile these things and struggling. He wanted his love for Giovanni to meet his ideal and he kept having those annoying, distracting bodily desires!

But what were Giovanni's views on all of this? Did he align with Marsilio or did he have different thoughts? If he differed I doubt he would have hidden it - they seemed very comfortable disagreeing with one another. Though Marsilio seems the one more willing to capitulate on things. Did they argue about how they thought they should be performing their love? What shifted, if anything, after Marsilio was ordained? Did the uncertainty of the Pazzi Conspiracy and subsequent Pazzi wars bring them closer together? Put a strain on them? I need to know~~~~~~

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marsilio “we are all made of stardust ✨” Ficino over here. (The excerpt is discussing book three of De Vita)

I do appreciate that he was like “while I have managed to heal myself through prayer it doesn’t work on the Plague so skip that step. Go right to medical intervention.” Granted, he was very much about doing everything humanly possible to save someone. Definitely, emphatically not someone who thought you could cure illness through prayer alone (though he did utilize prayer, as was normal back then for doctors let alone priests) nor was he someone who thought the state of your soul impacted your health. He wasn’t a “you get ill because you’re a sinner and God is punishing you” sort of doctor or priest.

Marsilio: I GUESS I will deign to see what day is propitious for laying a foundation stone. I guess. If I must. /annoyed noises/

Spicy drama! The girls are fighting!

This is one of my favourite letters from Angelo. The ending is so sweet. Love Angelo bartering to get Marsilio to stay with him. “My wine is better! Come stay with meeeee”

Ok but Pico absolutely did not walk the walk of his talk until like the last year of his life and even then he and the ladies…

Love their arguments

Love Angelo dozing off in the middle of Ficino’s more complex philosophical lectures.

———

Alright done with random Marsilio excerpts for now!

#marsilio blogging#marsilio ficino#Angelo poliziano#pico della mirandola#giovanni pico della mirandola#history#15th century#Renaissance Florence#Renaissance Italy

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marsilio Ficino to Giovanni Cavalcanti, his unique friend/most perfect friend*: greetings

I cannot let your people return to you from the Fighini market without any of our produce, for I think it very wrong that, whilst bringing you other men’s goods, they do not return with your own. So they bear three of our letters: one amends what I dictated hastily to my boy when our brother came, the others are copies of what I wrote long ago to Antonio degli Agli and Piero del Nero. I did not have anything of today to present, so I have given what is external.

You are a simpleton, Corydon! You send tasteless little fruits to a most discriminating palate. But have confidence; Alexis should savour these things at least a little;**

[...]

*I have seen both terms used in translation of Ficino’s pet-term for Giovanni.

**Ficino is quoting from Virgil’s Eclogues (or, Bucolics) where the shepherd boy Corydon is in (unrequired) love with another shepherd boy Alexis, framing himself as Corydon and Giovanni as Alexis. Though that Corydon was a good musician and wins a singing competition in the story is a fun parallel to Marsilio, who was known to be a very good musician himself. Cosimo had Ficino sing to him on his death bed (and read aloud what he had translated of Plato).

Marsilio Ficino to Giovanni Cavalcanti, his unique friend/most perfect friend: greetings

Because I am now forced to spend long periods in bed, I have been considering a remedy against the tedium of a continuing confinement. The first, indeed the only one who could relieve the tedium threatening me, came to mind; my Cavalcanti, my especial doctor. And so welcome again, my health giver, expeller of my evils, preserver of my goods.

You, my Giovanni, assuredly make many other things clear to me every day, but primarily this, the saying of Aristotle: nothing is more full of grace in the human condition than the presence of a most excellent friend. I learnt from you the meanings and the truth of this saying long ago, and I learnt the underlying principle. Behold, he who bore be inwardly away from myself, formerly as much by my desire for him as recently through his physical absence, that same one, in return, through a certain mutual disposing of mind and through his mental presence, restores me to myself.

[...]

Therefore you will receive a letter, perhaps more of necessity than of choice, for, as I have said, it seems that I have been compelled to compose it for the sake of dispelling tedium. But, Oh! I have just transgressed, I do not know how, my Giovanni, but I have transgressed seriously against the divine spirit and authority of Plato. Listen to Plato on high, sharply rebuking me, as he thunders: O Marsilio! what free choice or what necessity do you observe in a lover? A lover’s letter is as much of choice as of necessity. No necessity is more freely chosen than a loving necessity; no free choice is more necessary than the free choice of love.

[...]

And the lover already experiences the full-grown flame before he perceives the ray and the radiating point. He needs must burn, if he burn by heavenly decree. He needs must burn, for in seeking relief he always feeds the flame with the very drink with which vainly he hopes to quench it.

[...]

This is totally a very normal thing to write the man you love while sick in bed, Marsilio.

Marsilio Ficino to Giovanni Cavalcanti, his unique friend/most perfect friend: greetings

Yesterday at Novoli we celebrated the holy day of Saint Cristopher and Saint James. I said 'holy', Giovanni, and I would certainly have added 'feast', if you had been there. Without you nothing whatever is a feast for me. See how dear you are to your Marsilio, for whom, if one may say so, not even heavenly things have any value without you. This is just, for he who has joined Christopher and James in one holy festival, has likewise joined Marsilio and Giovanni in life. And the same spirit or a very similar one guides us both. God has ordained, I believe, that we should live on earth with a single will and similar way of life and in heaven under the same principle and in an equal degree of happiness.

Farewell, Achates of our voyage and our delight when we reach port.

these men are very straight.

Marsilio Ficino to Giovanni Cavalcanti, his unique friend/most perfect friend: greetings

The care of my own sick body and that of my father is one burden for me. Your absence is another. Both must be born with equanimity, lest they become more burdensome through impatience. But if you have any humanity, do not add to my double burden yet a third, too great a burden if you do not return my books. It is the loss of time that makes me ask for them so often. No loss is more serious than that. Alas that I ask so boldly for things I do not really want to receive; but for what I do want I dare not ask.

It is right that I should have the former, while at present it is necessary for me to be without the latter. It is prudent to do what is right and, as far as one can, to make what is necessary voluntary. The first is for you to do, and the second is for me to attempt.

Farewell, and while you are looking after other people’s affairs for their sake, take care of yourself for your own sake.

We don’t have a that for this letter, so we don’t know which books it is that Ficino sent him, but given this line: “Alas that I ask so boldly for things I do not really want to receive [his books]; but for what I do want I dare not ask [Giovanni himself]” I choose to believe he had sent along the latest version of his commentary on Plato’s Symposium (known at the time as his Book on Love), which he began at the behest of Giovanni who was trying to lever Marsilio out of a deep depressive episode by dangling Plato in front of him. (Dear readers, it worked. For a time, at least.)

Marsilio Ficino to Giovanni Cavalcanti, his unique friend/most perfect friend: greetings

The hand could not guide the pen were it not itself moved by the soul. Marsilio could not now write to his hero [Giovanni] were he not first so invited by his hero. But one thing that troubles me more than anything else is that you write to me because you promised; and that I attribute to a bargain, not to love.

I desire letters of love, not of barter; or are you really mine by contract just because I am yours? I wish you to be mine through love.

Marsilio being totally normal about Giovanni.

#marsilio blogging#marsilio ficino#Giovanni Cavalcanti#early modern italy#15th century#early modern history#early modern florence#obscure early modern Florence blogging

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

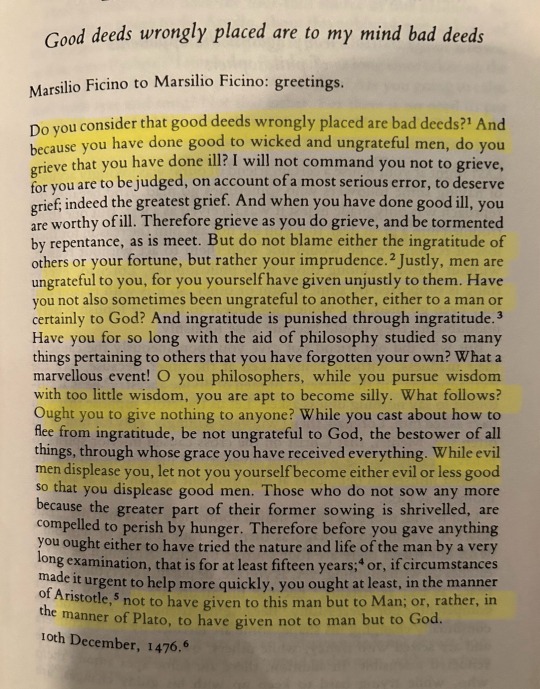

While I also have no idea what Marsilio is Renaissance vague-blogging about, one of the sentences here really hit me about him and about a lot of people who are really into academia or intellectual pursuits:

"Have you for so long with the aid of philosophy studied so many things pertaining to others that you have forgotten your own?"

It's simultaneously poignant and surprisingly difficult to parse. I immediately felt it as almost a slip into admitting that one of the things he (and many intellectually-focused folks) do is to study the abstract in order to distract themselves from inward reflection. But I don't think that's quite right. After all, this letter is all about inward reflection, and a lot of Ficino's philosophy springs straight from his internal dialogue with himself and with studying his own feelings about various topics. He's a weirdly intuitive, emotive intellectual.

But I also think he did try to abstract away from things about himself that made him uncomfortable. I'm sure he had many less than kind thoughts about others, but he was focused on kindness as a foundational philosophy, so he had to abstract away from the uglier parts of himself. And that's to say nothing of abstracting away from his mental health issues (only really engaging with them, so far as I can see, either because the depression was inescapable and he had to talk about it, or the more manic moods could be transported and interpreted as divine ecstasy), or from his more physical attractions (and possibly interactions) with Giovanni, which didn't square with his great love of Plato.

I just found that one line so interesting as it pertains to Ficino in particular, and would love to know what he meant by it, both directly and maybe on a more subconscious level too.

Marsilio writing letters to himself.

I’m not sure the context that this is situated in—maaaybe Pulci related? It’s the right year for the start of that grievance. But maybe it’s something else entirely. The footnotes weren’t helpful so alas, a little in the dark.

It could be Lorenzo related? We see a cooling in their relationship around this time and I know Marsilio felt a little betrayed/hurt that it took Lorenzo two or three years before he shut Pulci down in terms of the more flagrant public insults (always done in verse because this is the Renaissance baybeee). That said, who knows. Pure idle speculation on my side.

But that aside, it’s quite an interesting letter and gives some insight on how Marsilio certainly sought to conduct himself, even if he occasionally fell short of his own ideal and expectations.

#Marsilio Ficino#Neoplatonic gays#fascinating letter to himself#which is both enlightening#and still obscure#because he's both confronting himself#and not confronting himself at all it seems

13 notes

·

View notes